1. Introduction

Light amplification by stimulated emission of

radiation (termed laser), introduced in the 1960s by Maiman has

been a breakthrough in the field of dentistry (1). Lasers can broadly be classified, on

the type of tissue adaptability into hard-tissue lasers, such as

neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG), Er:YAG and

carbon-dioxide, and soft-tissue lasers, such as diode lasers

(2). While hard-tissue lasers are

more versatile as regards their application, they are more costly

and run a risk of causing thermal injury to the pulp (3).

The diode laser, running on the principle of a

semi-conductor is compact, affordable and versatile in its

application for soft tissue procedures and biostimulation. Its

application has been tried and tested over a number of years in the

field of dentistry and more specifically, in periodontology

(3). It has multiple settings for

various wavelength applications. Lower wavelengths (630-810 nm) are

appropriate for use in techniques, such as antibacterial

photodynamic therapy, while higher wavelengths (940-980 nm) are

used for bacterial decontamination, soft tissue curettage in

periodontal pockets and photobiomodulation (PBM) therapy.

2. Mechanisms of action of lasers

Lasers produce a single, coherent and monochromatic

light through stimulated emission in a medium excited by an

external energy source. Mirrors reflect and amplify photons, with a

partially reflecting mirror, at an angle, narrowing the light to a

focused beam prepared to emerge (4).

The wavelength is primarily determined by the

composition of its active medium, namely gas, crystal or a solid

semiconductor. Out of the four possible interactions which can

occur, that include reflection, transmission, scattering and

absorption, the latter is the most ideal for its application

(5). Once absorbed, the

temperature rises, producing photochemical effects. Protein

denaturation occurs at temperatures ranging from 60 to 100˚C.

Beyond this range, water ablation or vaporization occurs. In the

event that the temperature exceeds 200˚C, all water content is lost

and dehydration results in burning (Fig. 1).

Diode lasers

Diode lasers are packed into a conveniently sized

and portable device, allowing for an easier application across

different procedures in the field of dentistry. A diode laser is

primarily a solid semiconductor comprised of aluminium, gallium,

arsenide and indium. This is used to convert the input electrical

energy to produce light of varying wavelengths. These are further

readily absorbed by chromophores, such as melanin and hemoglobin

present in the soft tissue, allowing for ideal application. The use

of diode lasers in hard tissue, however, is not practically

applicable, as they exhibit poor absorption by hydroxyapatite,

predominantly observed in enamel. The flexible fiber optic fiber

aids in delivering treatment rays to the desired area (6). The treatment plan determines the use

of either continuous or pulsed modes and that of contact and

non-contact applications.

Over the years, ample research has been performed to

further investigate diode lasers, and various advantages have been

suggested. Compared to more conventional techniques, such as the

use of scalpels, diode lasers provide higher precision, a more

bloodless field, and thus, improved visualization, and the

placement of suture is obsolete. Diode lasers also provide an

excellent post-operative recovery period with minimal bleeding,

swelling and pain (7).

However, the use of diode lasers is not without

disadvantages. The equipment is costly, and is thus not accessible

to all dental clinics. Their use is also associated a risk of

morbidities, such as damage to the eye in the case that appropriate

protection is not used; thus, specialized training is required for

the use of diode lasers (8).

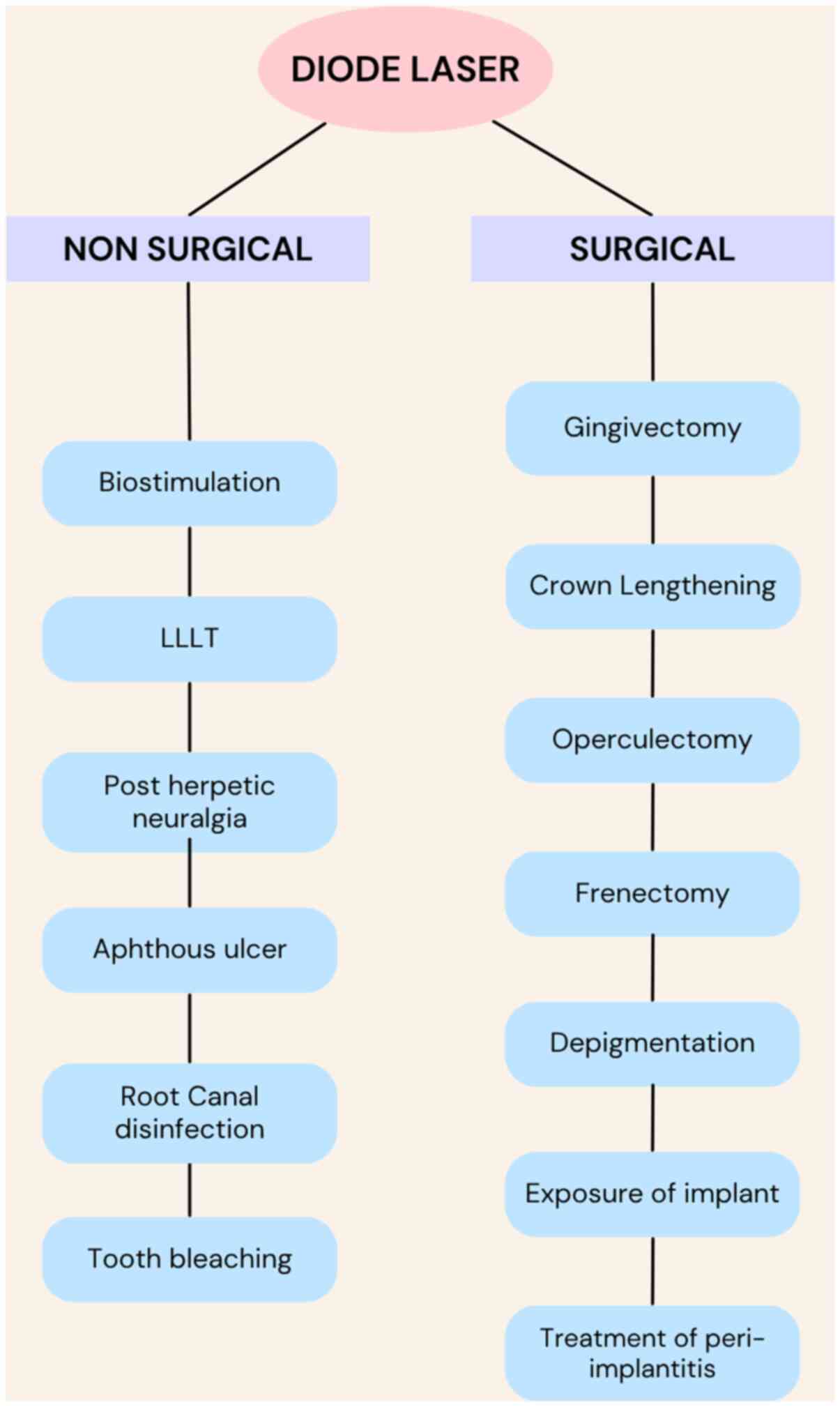

Below, the use of diode lasers in dentistry is discussed.

Crown lengthening

Diode lasers can be applied to various procedures,

such as in case of inadequate crown length prior to crown

placement, for the restoration of subgingival caries or fracture

exposure and for the correction of gummy smile (9). However due to a lack of hard-tissue

applications, it cannot only be used in cases where there is a wide

band of keratinized tissue and optimal space between the alveolar

crest and cementoenamel junction. The use of diode lasers is

proposed to be a more safe and effective alternative to the

traditional scalpel, as these lasers minimize bleeding and improve

post-operative pain according, to the visual analogue score

(10).

Gingival depigmentation

In the case of severely pigmented gingiva, a

surgical periodontal procedure may be used to reduce or remove the

zones of hyperpigmentation with the aid of a scalpel, high-speed

handpiece, cryosurgery or electrosurgery (11). Diode lasers have been proven to be

a single-step alternative. They eliminate the need for a

periodontal dressing, as their use is associated with a more rapid

healing process, with reduced pain and discomfort (12). A higher esthetic appearance is

expected when using the diode laser for gingival depigmentation

compared to the CO2 laser. The application of the diode

laser at pulsed mode may be recommended for gingival

depigmentation, as its use is associated with improved esthetic

outcomes and requires a smaller amount of time to achieve results

(13). The increasing esthetic

demands of individuals require the removal of hyperpigmented

gingival areas to create a confident and appealing smile, which can

be easily attained using a laser. As regards clinical significance,

the use of a laser is an effective tool which requires a smaller

amount of time to obtain results. The use of lasers is also

associated with lower levels of pain and discomfort, as well as a

more rapid healing process, and delayed repigmentation compared

with the use of scalpels or electrosurgery for gingival

depigmentation (14).

Exposure of unerupted and partially

erupted teeth

Lasers are also used for soft tissue removal over

unexposed or partially erupted teeth, for the placement of

orthodontic brackets or the removal of an operculum. They have an

added advantage over surgery in sealing small blood vessels and

lymphatic vessels. There is also minimal tissue shrinkage in laser

procedures, and thus, less scarring. The need for suturing is also

eliminated in the majority of cases, as healing occurs by secondary

intention (15).

Removal of tissue overgrowth

Fibrous hyperplasia is often observed due to

chronically ill-fitting dentures. To resume the use of dentures,

overgrowth removal is necessary (16). Diode lasers exhibit positive

results along with suitable homeostasis and less post-operative

pain. They can also be utilized to obtain biopsy specimens

(17).

Frenectomies

A high labial frenum can cause severe discomfort and

pain, in which case its removal may be indicated (18). For a relatively painless, bloodless

procedure with reduced post-surgical complications, diode lasers

can be used. The use of diode lasers is also particularly useful in

ankyloglossia. In these cases, a thick band of frenal attachment is

observed from the floor of the mouth until the tip of the tongue.

The excision of this band of tissue is essential for free tongue

movement (19).

Implant dentistry

Implant dentistry has been revolutionized over the

past few years. It has been striving to replace more redundant

techniques (20). In such a field,

diode lasers have been proven to be an immense success. They are

particularly useful in the second-stage of implant surgeries, as

they provide an efficient, safe, bloodless and painless procedure

(21). Diode lasers have also been

proven to be useful for the removal of peri-implant soft tissue and

the decontamination of failing implants. Various studies have been

conducted in this field of study that prove that diode

laser-assisted implant exposure eliminates the need for local

anesthesia (22).

However, the duration of surgery, healing time,

post-operative pain and overall success of the implant exhibit

similar results to those of scalpel surgery. Following treatment

for peri-implantitis with lasers, there is also a lack of

re-osseointegration observed with the use of lasers. There is also

a concern raised regarding the overheating of the implant surface,

followed by melting which can be a crucial drawback (23).

Wound healing

Biostimulation is another term for low-level laser

therapy (LLLT). Research indicates that a small amount of laser

energy (2 J/cm2) encourages the growth of fibroblasts,

whereas larger doses (16 J/cm2) inhibit their

proliferation (24). The rise in

fibroblast growth and movement leads to greater strength in healed

wounds. Research indicates that within the initial 72 h following

radiation exposure, biostimulation through LLLT leads to the

increased proliferation and maturation of human osteoblast-like

cells. In fact, a synergistic effect of laser use in combination

with ozonized substances has been demonstrated (25).

Photoactivated disinfection (PAD)

Low-level laser energy from a diode lasers functions

as a photo-activator of oxygen releasing dyes, such as Methylene

blue. This has been shown to cause membrane and DNA damage to

microorganisms when activated (26).

As stated in the literature, PAD has been found to

be particularly effective in killing bacteria, including

sub-gingival plaque in deep periodontal pockets, which are

generally known to be resistant to anti-microbial agents. It has

also been demonstrated to kill Gram-positive bacteria (including

methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus), Gram-negative

bacteria, fungi and viruses. It is also now being used in the

disinfection of peri-mucositis and peri-implantitis (26).

Post-herpetic neuralgia and aphthous

ulcers

Post-herpetic neuralgia is a chronic painful

condition that occurs as a complication of herpes zoster virus

(27). It is generally observed

due to the reactivation of a varicella zoster virus found dormant

in a nerve cell near the spinal cord. This virus is commonly known

to cause chickenpox. Upon reactivation, it manifests as a painful

rash along the specific dermatome innervated by the spinal nerve

(27).

The condition is commonly known to be painful along

with hyperesthesia or even allodynia. LLLT has been demonstrated to

reduce this pain and enhance the healing process in these

conditions. In particular, in the case of recurrent herpes simplex

labialis lesions, photostimulation during the prodomal stage has

been shown to arrest the acceleration and progression of the

healing process and to reduce recurrence (28).

Root canal disinfection

Traditionally, root canal preparation is performed

with mechanical instrumentation using files and irrigants. In

vitro studies (29-31)

have suggested the use of laser irradiation following this to

increase the disinfection of deep radicular dentin. It has also

been associated with effective sealing of dentinal tubules,

eliminating Escherichia coli and Enterococcus

faecalis. This has also been suggested to increase the efficacy

of endodontic treatments (29-31).

Removal of periodontal pocket

lining

In the case of a periodontal pocket, scaling and

root planing are the primary steps for treatment. This helps remove

the inflamed gingival tissue and infected material present in the

pocket. Following this, the optical fiber of a diode laser can be

introduced into the pocket in ascending and descending movements,

while maintaining it parallel to the main access of the tooth root

(32). It is rotated around the

perimeter of each involved tooth. This helps to remove the pocket

lining, leading to a reduction of the periodontal pocket (33).

In their study, Assaf et al (34) used a diode laser in conjunction

with ultrasonic scaling for the treatment of gingivitis. The

results of their study revealed a significantly lower incidence of

bacteremia in the group treated with diode and ultrasonic therapy

(36%) compared with the group treated only with ultrasonic therapy

(68%) (34). In addition, it has

been suggested that in order to prevent bacteremia, particularly in

immuno-compromised patients, diode lasers should be used. For

example, Kamma et al (35)

confirmed that the total bacterial load in pockets was reduced

without the use of any systemic antibiotic therapy.

Tooth whitening

Laser lights enhance the efficacy of hydrogen

peroxide in the bleaching agent to a greater extent than

light-emitting-diodes (LEDs) (36). Teeth bleached with LEDs exhibit a

significant decrease in color intensity and appear gray, while

those treated with laser exhibit improved color intensity and less

grayness (37). Furthermore,

increased brightness and decreased sensitivity can be attained

using lasers to activate hydrogen peroxide (38).

3. Laser-assisted pediatric dentistry

Lasers have emerged as a valuable tool in pediatric

dentistry due to their minimally invasive nature, reduced need for

anesthesia and improved patient comfort. Diode lasers are commonly

used for soft tissue procedures, such as frenectomy, pulpotomy and

gingivoplasty. In children, lasers provide advantages, such as

reduced bleeding, a more rapid healing process and lower anxiety

levels compared to conventional techniques. Moreover, their

bactericidal properties enhance infection control in procedures

involving the pulp or soft tissues. However, careful parameter

selection is essential to avoid thermal damage, particularly in

immature or developing tissues (39).

PBM and anesthesia

PBM has gained increasing attention due to its

efficacy in pain reduction in various fields of dentistry. However,

available studies on the effects of PBM on injection pain in

children are minimal. A previous study examined the efficacy of PBM

with three different application parameters (doses) and topical

anesthesia in reducing injection pain and compared these results

with the placebo PBM and topical anesthesia in children during

supraperiosteal anesthesia administration; however, no differences

were found between the groups (P=0.109 and P=0.317). In addition,

in that study, the injection pain in children did not differ

compared to the placebo and PBM applied at a power of 0.3 W for 20,

30 and 40 sec (40).

4. Laser-tissue interactions and related

complications

Laser-tissue interactions in periodontal therapy are

governed by factors, such as wavelength, power density, pulse

duration and tissue characteristics. While lasers provide numerous

advantages, including precise cutting, hemostasis and minimal

postoperative discomfort, overexposure to laser energy can lead to

significant soft tissue complications. Excessive thermal energy can

cause coagulative necrosis, carbonization, or deep tissue burns,

leading to delayed wound healing and scarring. Moreover, prolonged

or improperly focused exposure can result in destruction of

adjacent healthy tissue, compromising the structural and functional

integrity of the periodontium. Overheating may also impair

microcirculation and fibroblast viability, essential for optimal

regeneration. In some cases, laser-induced edema, pain, or

ulceration has been reported due to excessive tissue ablation or

inadequate cooling. Therefore, strict adherence to recommended

laser parameters and technique is critical to avoid iatrogenic

injury and ensure therapeutic efficacy (41).

5. Advances in diode lasers

A dual-wavelength diode laser in dentistry has been

introduced that combines two distinct wavelengths, typically 450

and 808 nm, in order to provide a versatile approach to soft-tissue

procedures. This approach has certain advantages compared to

single-wavelength lasers, as it utilizes the unique properties of

each wavelength to achieve optimal coagulation, ablation and

healing (42).

A flexible optical fiber, typically in the form of a

handpiece, transmits the laser beams to the target area. The laser

can be used in both continuous and pulsed modes (pulse duration

ranging from 0.1 msec to infinity, with programmable frequencies up

to 10,000-20,000 Hz). The laser beam is delivered through optical

fibers with diameters ranging from 200 to 600 µm. The clinical

approach and treatment methods determine the selection between

continuous and pulsed modes, contact or non-contact tissue

application, and the specific type of tip recommended by the

manufacturer. A number of diode lasers allow for the adjustment of

parameters, such as power and frequency to minimize tissue damage

and enhance precision. The use of dual-wavelength lasers for

surgical purposes can lead to improved hemostatic cutting. In the

majority of cases, healing occurs by secondary intention with

minimal scar formation, eliminating the need for sutures.

Additionally, there is a significant reduction in post-operative

pain and inflammation, attributed to cellular biomodulation

resulting from residual energy transmission to the tissues during

the cutting action. By using both wavelengths, dual-wavelength

lasers can achieve a balance between coagulation and ablation,

potentially minimizing collateral damage and promoting more rapid

healing (42).

6. Conclusion and future perspectives

Diode laser technology and its various applications

in dentistry date back to several decades; however, it has been in

the past 10 years that diode lasers have gained a greater

prominence owing to the immense technical development achieved and

the materialization of affordable equipment for the dentist. All

these advancements have allowed for the current use of lasers in

numerous procedures to improve the performance of conventional

therapies; however, this is not sufficient. The use of different

diode laser therapies should be consolidated with further research.

In recent years, progress has been made in this regard, as it has

gained increasing prominence as an adjuvant therapy; however,

although there are several notable in vitro and clinical

studies available on the use of lasers (as aforementioned), further

research is warranted to address laser therapy from a different

perspective (43).

There is a possibility to match laser technology

with other recently introduced technology, such as smartphone

applications and artificial intelligence. It is desirable that

future studies evaluate long-term results to confirm the

effectiveness and use of diode lasers. Furthermore, studies

involving larger samples are warranted. The importance of lasers

should be explained by dental practitioners to make patients aware

of their existence and benefits. The ethical and legal implications

of the use of lasers should also be carefully considered. It would

also of interest to combine lasers with recently introduced

artificial intelligence software, which is an interesting and

current research topic (44,45).

In conclusion, the utilization of diode lasers in

oral soft tissue surgery is due to their simple application,

improved coagulation, elimination of suturing, reduced swelling and

pain, and their ability to address physiological gingival

pigmentation for aesthetic purposes. Diode lasers are a preferred

option for their swift action, enhanced de-epithelialization, lack

of bleeding and superior healing. Over the past 40 years, diode

lasers have been increasingly utilized in various dental

procedures, such as biostimulation for wounds, activating teeth

whitening gel, photodynamic disinfection and enhancing root canal

disinfection. Due to its affordable price and convenient size, this

optical scalpel is becoming increasingly popular among dentists in

dental clinics and hospitals.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

All authors (DK, DGK, SS and AS) contributed to the

conception and design of the study. DK, SS and AS were involved in

manuscript preparation, and the collection and analysis of data

from the literature. DK wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript. Data

authenticity is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Gross AJ and Hermann TR: History of

lasers. World J Urol. 25:217–220. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Center D: Application of laser in

dentistry: A brief review. J Adv Med Dental Sci Res. 9:2321–9599.

2021.

|

|

3

|

Luke AM, Mathew S, Altawash MM and Madan

BM: Lasers: A review with their applications in oral medicine. J

Lasers Med Sci. 10:324–329. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Maheshwari S, Jaan A, Vyaasini CS, Yousuf

A, Arora G and Chowdhury C: Laser and its implications in

dentistry: A review article. Curr Med Res Opin. 3:579–588.

2020.

|

|

5

|

Goldman L, Goldman B and Van-Lieu N:

Current laser dentistry. Lasers Surg Med. 6:559–562.

1987.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Aoki A, Mizutani K, Takasaki AA, Sasaki

KM, Nagai S, Schwarz F, Yoshida I, Eguro T, Zeredo JL and Izumi Y:

Current status of clinical laser applications in periodontal

therapy. Gen Dent. 56:674–687. 2008.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Carroll L and Humphreys TR: Laser-tissue

interactions. Clin Dermatol. 24:2–7. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Desiate A, Cantore S, Tullo D, Profeta G,

Grassi FR and Ballini A: 980 nm diode lasers in oral and facial

practice: Current state of the science and art. Int J Med Sci.

6:358–364. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Camargo PM, Melnick PR and Camargo LM:

Clinical crown lengthening in esthetic zone. J Calif Dent Assoc.

35:487–98. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Farista S, Kalakonda B, Koppolu P, Baroudi

K, Elkhatat EN and Dhaifullah E: Comparing laser and scalpel for

soft tissue crown lengthening: A clinical study. Glob J Health Sci.

8(55795)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kumar R, Jain G, Dhodapkar SV, Kumathalli

KI and Jaiswal G: The comparative evaluation of patient's

satisfaction and comfort level by diode laser and scalpel in the

management of mucogingival anomalies. J Clin Diagn Res. 9:56–58.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Roshn T and Nandakumar K: Anterior

esthetic gingival depigmentation and crown lengthening: Report of a

casese. J Contemp Dent Pract. 6:139–147. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Moeintaghavi A, Ahrari F, Fallahrastegar A

and Salehnia A: Comparison of the effectiveness of CO2 and diode

lasers for gingival melanin depigmentation: A randomized clinical

trial. J Lasers Med Sci. 13(e8)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Jagannathan R, Rajendran S, Balaji TM,

Varadarajan S and Sridhar LP: Comparative evaluation of gingival

depigmentation by scalpel, electrosurgery, and laser: A 14 months'

Follow-up study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 21:1159–1164.

2020.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sarver DM and Yanosky M: Principles of

cosmetic dentistry in orthodontics: Part 2. Soft tissue laser

technology and cosmetic gingival contouring. Am J Orthod

Dentofacial Orthop. 127:85–90. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chawla K, Lamba AK, Faraz F, Tandon S and

Ahad A: Diode laser for excisional biopsy of peripheral ossifying

fibroma. Dent Res J. 11:525–530. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

D'Arcangelo C, Di Nardo Di Maio F,

Prosperi GD, Conte E, Baldi M and Caputi S: A preliminary study of

healing of diode laser versus scalpel incisions in rat oral tissue:

A comparison of clinical, histological, and immunohistochemical

results. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod.

103:764–773. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Yadav RK, Verma UP, Sajjanhar I and Tiwari

R: Frenectomy with conventional scalpel and Nd: YAG laser

technique: A comparative evaluation. J Indian Soc Periodontol.

23:48–52. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Kalakonda B, Farista S, Koppolu P, Baroudi

K, Uppada U and Mishra A: Evaluation of patient perceptions after

vestibuloplasty procedure: A comparison of diode laser and scalpel

techniques. J Clin Diagn Res. 10:96–100. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yeh S, Jain K and Andreana S: Using a

diode laser to uncover dental implants in secondstage surgery. Gen

Dent. 53:414–417. 2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

El-Kholey KE: Efficacy and safety of a

diode laser in secondstage implant surgery: A comparative study.

Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 43:633–638. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gianfranco S, Francesco SE and Paul RJ:

Erbium and diode lasers for operculisation in the second phase of

implant surgery: A case series. Timisoara Med J. 60:117–123.

2010.

|

|

23

|

Grzech-Lesniak K: Making use of lasers in

periodontal treatment: A new gold standard? Photomed Laser Surg.

35:513–514. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

O'Neill JF, Hope CK and Wilson M: Oral

bacteria in Multi-species biofilms can be killed by red light in

the presence of toluidine blue. Lasers Surg Med. 31:86–90.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Scribante A, Gallo S, Pascadopoli M, Soleo

R, Di Fonso F, Politi L, Venugopal A, Marya A and Butera A:

Management of periodontal disease with adjunctive therapy with

ozone and photobiomodulation (PBM): A randomized clinical trial.

Photonics. 9(138)2022.

|

|

26

|

Husejnagic S, Lettner S, Laky M,

Georgopoulos A, Moritz A and Rausch-Fan X: Photoactivated

disinfection in periodontal treatment: A randomized controlled

clinical Split-mouth trial. J Periodontol. 90:1260–1269.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

To DS, Martins MA, Bussadori SK, Fernandes

KP, Tanji EY, Mesquita-Ferrari RA and Martins MD: Clinical

evaluation of low level laser treatment for recurring aphthous

stomatitis. Phtomed Laser Surg. 28 (Suppl 2):S85–S88.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bladowski M, Konarska-Choroszucha H and

Choroszucha T: Comparison of treatment results of recurrent

aphthous stomatitis (RAS) with low-and high-power laser irradiation

vs. pharmaceutical method. J Oral Laser Applic. 4:191–209.

2004.

|

|

29

|

de Souza EB, Cai S, Simionato MR and

Lage-Marques JL: High-power diode laser in the disinfection in

depth of the root canal dentin. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral

Radiol Endod. 106:e68–e72. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Theodoro LH, Haypek P, Bachmann L, Garcia

VG, Sampaio JEC, Zezell DM and Eduardo Cde P: Effect of ER: YAG and

diode laser irradiation on the root surface: Morphological and

thermal analysis. J Periodontol. 74:838–843. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Menezes M, Prado M, Gomes B, Gusman H and

Simão R: Effect of phootodynamic therapy and non-thermal plasma on

root canal filling: Analysis of adhesion and sealer penetration. J

App Orl Sci. 25:396–403. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Caccianiga G, Rey G, Baldoni M, Caccianiga

P, Baldoni A and Ceraulo S: Periodontal decontamination induced by

light and not by heat: Comparison between oxygen high level laser

therapy (OHLLT) and LANAP. App Sci. 11(4629)2021.

|

|

33

|

Jha A, Gupta V and Adinarayan R: LANAP,

periodontics and beyond: A review. J Lasers Med Sci. 9:76–81.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Assaf M, Yilmaz S, Kuru B, Ipci SD, Noyun

U and Kadir T: Effect of the diode laser on bacteremia associated

with dental ultrasonic scaling: A clinical and microbiological

study. Photomed Laser Surg. 25:50–56. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kamma JJ, Vasdekis VG and Romanos GE: The

effect of diode laser (980 nm) treatment on aggressive

periodontitis: Evaluation of microbial and clinical parameters.

Photomed Laser Surg. 27:11–9. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Dostalova T, Jelinkova H, Housova D, Sulc

J, Nemec M, Miyagi M, Junior AB and Zanin F: Diode laser-activated

bleaching. Brazi DentJ. 15 (Suppl 1):SI3–S18. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wetter NU, Walverde D, Kato IT and Eduardo

Cde P: Bleaching efficacy of whitening agents activated by xenon

lamp and 960-nm diode radiation. Photomed Laser Surg. 22:489–493.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Vildósola P, Bottner J, Avalos F, Godoy I,

Martín J and Fernández E: Teeth bleaching with low concentrations

of hydrogen peroxide (6%) and catalyzed by LED blue (450±10 nm) and

laser infrared (808±10 nm) light for in-office treatment:

Randomized clinical trial 1-yearfollow-up. J Esthet Restor Dent.

29:339–345. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Nazemisalman B, Farsadeghi M and

Sokhansanj M: Types of lasers and their applications in pediatric

dentistry. J Lasers Med Sci. 6:96–101. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Elbay M, Elbay ÜŞ, Kaya E and Kalkan ÖP:

Effects of photobiomodulation with different application parameters

on injection pain in children: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin

Pediatr Dent. 47:54–62. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Ansari MA, Erfanzadeh M and Mohajerani E:

Mechanisms of Laser-tissue interaction: II. tissue thermal

properties. J Lasers Med Sci. 4:99–106. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Pergolini D, Del Vecchio A, Mohsen M,

Cerullo V, Angileri C, Troiani E, Visca P, Antoniani B, Romeo U and

Palaia G: Histological evaluation of oral soft tissue biopsy by

Dual-wavelength diode laser: An ex vivo study. Dent J (Basel).

13(265)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Krishnan PA and Sukumaran A: Lasers and

their applications in the dental practice. Int J Dentistry Oral

Sci. 7:936–943. 2020.

|

|

44

|

Pascadopoli M, Zampetti P, Nardi MG,

Pellegrini M and Scribante A: Smartphone applications in dentistry:

A scoping review. Dent J (Basel). 11(243)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Wang C, Yang J, Liu H, Yu P, Jiang X and

Liu R: Co-Mask R-CNN: Collaborative Learning-based method for tooth

instance segmentation. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 48:161–172.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|