Introduction

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), caused by median nerve

(MN) compression at the wrist, is the most prevalent type of

entrapment neuropathy of the wrist (1). The median nerve distribution is

affected by symptoms, such as pain, tingling and numbness, and the

global incidence of this condition has been reported to range from

0.24 to 0.4% (1,2).

A clinical evaluation and nerve conduction studies

(NCS) are the two requirements for reaching a diagnosis;

nevertheless, NCS tests are not only uncomfortable, but are also

time-consuming and prone to producing misleading results (3,4). The

measurement of the MN cross-sectional area (CSA) at the flexor

retinaculum using ultrasound (US) is a promising alternative that

does not involve any invasive procedures. This method enables the

direct measurement of the MN CSA (5). In comparison to electrodiagnostic

examinations, it is more convenient, less costly and provides

morphological data (6). However,

the connection between CSA-D and NCS latencies is not yet fully

understood, despite the fact that it has the potential to be

significant.

The present study thus aimed to determine the

correlation between the MN CSA at the distal wrist (CSA-D) with the

severity of CTS, as graded by NCS.

Patients and methods

Study design and setting

The present prospective, cross-sectional study was

carried out at the Al-Imamen Al-Kadhmin Medical Teaching Hospital

(a primary teaching hospital affiliated with the College of

Medicine, Al-Nahrain University) in Baghdad, Iraq during the months

of September, 2023 and July, 2024. The study cohort comprised 60

female patients. The sample comprised only females as the

prevalence of CTS is markedly higher in females than males. There

were no male patients during patient recruitment period. Patients

were presenting with clinical signs and symptoms suggestive of CTS,

as assessed by an orthopedic surgeon. Clinical indicators of CTS

included tingling and/or numbness, nocturnal symptoms mostly in MN

distribution and positive results on a clinical examination (Phalen

test or compression test).

Ethical considerations

Research approval was obtained from the

institutional Review Board of Al-Khadimain Teaching Hospital

(Reference no. 5563 on April 24, 2023). Following the explanation

of the objectives of the study, each participant completed a

consent form before the commencement of data collection.

Participants were informed of their unconditional right to withdraw

at any time, and the confidentiality of all collected data was

strictly maintained.

Patient population and data

collection

Direct interviews were used to obtain patient

demographics [age and body mass index (BMI)]. The inclusion

criteria were the following: The presence of typical CTS symptoms,

such as numbness, tingling, burning, or pain in the median nerve

distribution (thumb, index, middle fingers); a duration of symptoms

persisting for a minimum period (e.g., ≥3 months); and clinical

signs, i.e., positive provocative tests, such as Phalen s test

or Tinel s sign, as assessed by an orthopedic surgeon.

The exclusion criteria were the following: Patients

were excluded if they had a history of concomitant illnesses, such

as cervical radiculopathy, prior ipsilateral CTS surgery,

rheumatoid arthritis, thyroid disease, pregnancy, brachial

plexopathy, wrist fractures and polyneuropathy.

NCS and severity grading

An electrophysiologist blinded to the findings of

the clinical and US investigations conducted NCS, which consisted

of five different motor and sensory nerve measurements. Compound

muscle action potentials (CMAPs) and distal motor latencies (DMLs)

were recorded for this investigation, and motor latencies were

measured over 5-6 cm segments over the MN.

Measurements of sensory nerve action potentials

(SNAPs) and distal sensory latencies were made in addition to

sensory latencies recorded over 12-13 cm segments of the MN. NCS

results were deemed normal when the following criteria were met: MN

motor latency <4.0 msec, CMAP amplitude >10 mV, MN sensory

latency <3.5 msec, and SNAP amplitude >6 µV. The thresholds

were obtained from previous studies on CTS, as well as guidelines

from clinical neurology (7-11).

The inability to satisfy any of these requirements was the defining

characteristic of a positive electrodiagnostic test result for

CTS.

Electrophysiological severity

grading

The severity of CTS was classified as mild, moderate

or severe based on the findings of NCS, in accordance with the

electrodiagnostic guidelines that have been developed (12): i) Mild CTS: Prolonged median

sensory latency (>3.5 msec) with normal median motor distal

latency (≤4.0 msec); ii) moderate CTS: Prolonged median sensory

latency and prolonged median motor distal latency (>4.0 msec)

with a preserved CMAP amplitude; iii) severe CTS: Prolonged median

motor and sensory latencies with either a low CMAP amplitude

(<4.5 mV) and/or electrophysiological evidence of axonal loss.

In the present study, it was confirmed that all 65 wrists (as in 5

patients, both wrists were affected) were classified using these

specific, quantitative metrics.

Ultrasonographic examination

A radiologist, blinded to the results of the

electrodiagnostic testing, conducted the ultrasonography of the

median nerve. The carpal tunnel entrance at the pisiform bone was

utilized to measure the CSA of the MN. A 4-12 MHz linear array

transducer (US machine: Affiniti 30 Ultrasound system; Philips

Medical System) was employed for the ultrasonography, positioned

vertical to the forearm.

On the examination table, the patients lay on their

backs, elbows bent at 90˚, and forearms widely splayed. An ellipse

function was employed by the US machine to determine the CSA. The

hyperechoic epineurium interior area can be determined using this

function, which forms an ellipse around the target region (13).

Assessment of measurement

reliability

An intra-observer variability assessment was carried

out to guarantee the accuracy and reproducibility of the

ultrasonographic measurements. Following 1 week, 15 patients

(representing 25% of the total sample) were re-measured for CSA-D

by the same radiologist who had been blinded to the

electrodiagnostic results.

Reproducibility was high, with an intra-class

correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.94 (95% CI, 0.87-0.98) for

intra-observer reliability. To reduce the possibility of operator

error, the NCS relied on a single, highly trained

electrophysiologist to conduct each test according to a

predetermined procedure. In conformity with the standards set forth

by the American Association of Neuromuscular &

Electrodiagnostic Medicine (AANEM), all subjects had identical

equipment settings and electrode placements (12).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were executed using SPSS

software (version 25.0). Continuous data that were not normally

distributed data were analyzed using the Kruskal Wallis test

followed by Dunn s multiple comparisons test. The

discriminative ability of the MN CSA in distinguishing between

mild, moderate and CTS was assessed using receiver operating

characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Pearson s correlation

analysis was used to examine potential correlations between MN CSA

and other variables. A P-value <0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Results

Demographic and clinical

characteristics of the patients

The study population had a mean age of 49.7±11.34

years. The cohort, comprising exclusively female participants, had

a mean BMI of 28.58±3.1 kg/m2, categorizing the majority

of the patients as overweight or obese. In total, 58.46% of the

patients had an involvement of the right wrist (Table I).

| Table IDemographic characteristics of the

patients with carpal tunnel syndrome in the present study

(n=60). |

Table I

Demographic characteristics of the

patients with carpal tunnel syndrome in the present study

(n=60).

| Variables | Value |

|---|

| Age, years | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 49.7±11.34 |

|

Range | 25-68 |

| Height, cm | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 165.5±9.4 |

|

Range | 150-179 |

| Weight, kg | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 75.18±9.0 |

|

Range | 67-102 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | |

|

Mean ±

SD | 28.58±3.1 |

|

Range | 23.2-35.0 |

| Patients (n=60) | Unilateral CTS:

55 |

| | Bilateral CTS: 5 |

| Wrists (n=65) | Right: 38

(58.46%) |

| | Left: 27

(41.54%) |

Electrophysiological parameters and

ultrasonography

The mean DML and CMAP of the affected MN were

5.43±2.08 msec and 5.81±1.89 msec, respectively. Abnormalities in

conduction velocities and sensory latencies were prevalent, with a

mean motor conduction velocity of 53.0±6.42 m/sec, mean sensory

latency of 4.56±2.57 msec, and mean sensory conduction velocity of

30.98±23.91 m/sec. The ultrasonography findings revealed that the

mean CSA of the affected MN at its distal segment was 17.9±4.1

mm2 (Table II).

| Table IIElectrophysiological parameters and

sonography (60 wrists). |

Table II

Electrophysiological parameters and

sonography (60 wrists).

| Variables | Mean ± SD | Range |

|---|

| MN distal motor

latency, msec | 5.43±2.08 | 2.8-11.2 |

| MN compound muscle

action potential (msec) | 5.81±1.89 | 1.9-9.7 |

| MN motor conduction

velocity, msec | 53.0±6.42 | 35.5-68.8 |

| MN sensory latency

msec | 4.56±2.57 | 2.5-11 |

| MN sensory action

potentials amplitude, µv | 30.98±23.91 | 3.5-98.4 |

| MN sensory

conduction velocity, msec | 31.66±10.77 | 10.8-48.0 |

| MN cross sectional

area, mm2 | 17.9±4.1 | 10.0-31.0 |

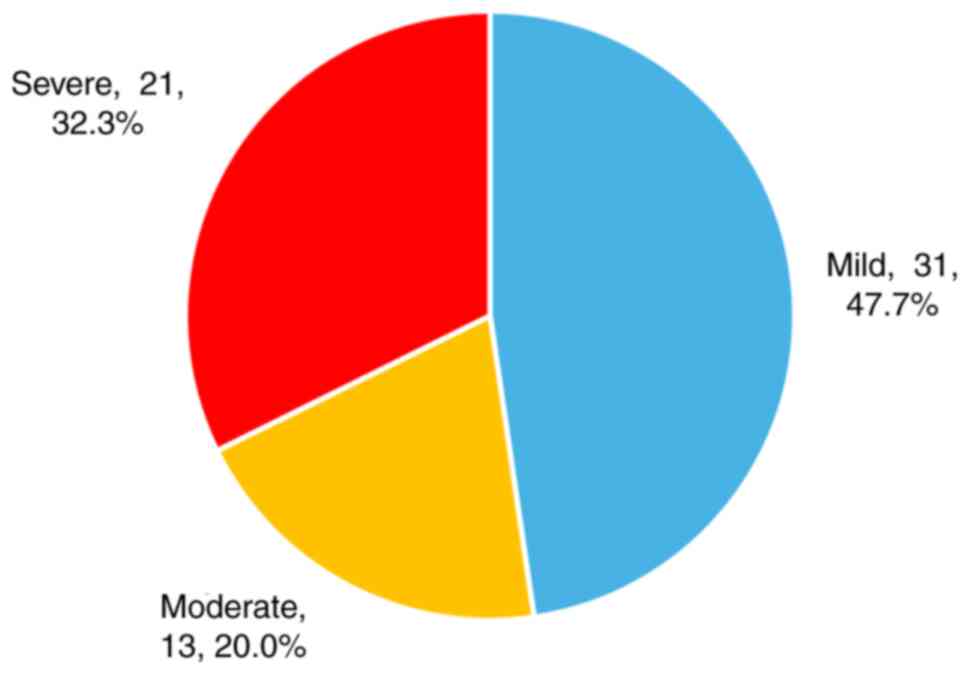

Distribution of disease severity

Based on the American criteria for CTS

classification (14), of the 65

affected wrists, 31 (47.69%) were categorized as having mild

disease, 13 (20%) as moderate disease, and 21 (32.3%) as severe

disease (Fig. 1).

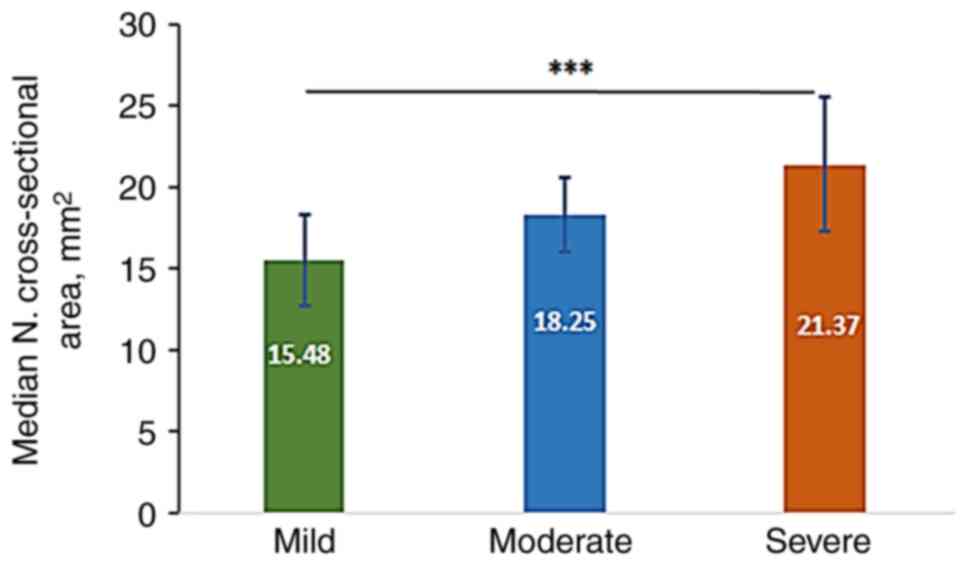

Association between median nerve CSA-D

and disease severity

The mean CSA-D in mild, moderate and severe cases

was 15.48±2.82, 18.25±2.62 and 21.37±4.14 mm2,

respectively, with highly significant differences observed between

mild and severe categories, as analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis

test followed by Dunn s test for multiple comparisons

(Fig. 2).

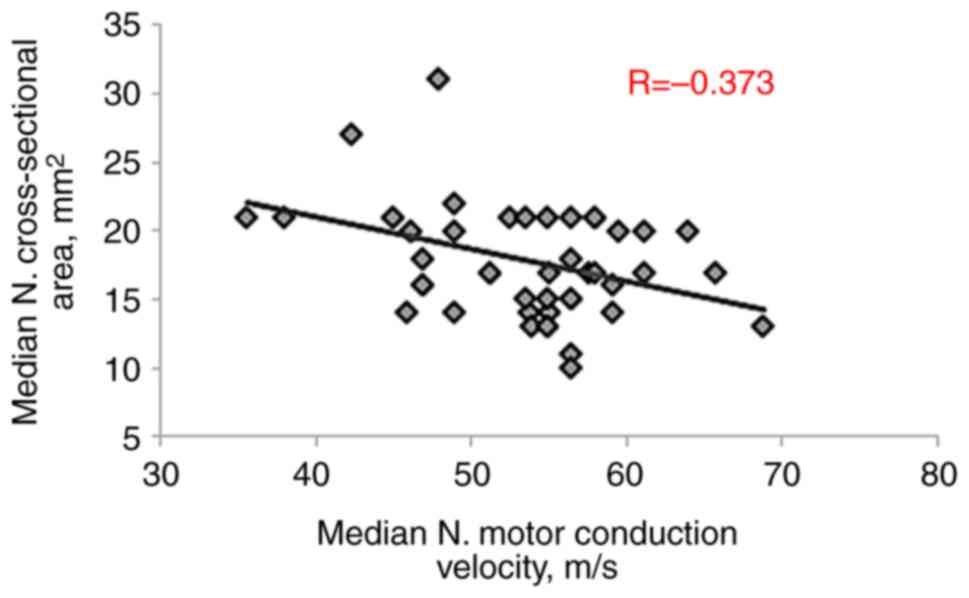

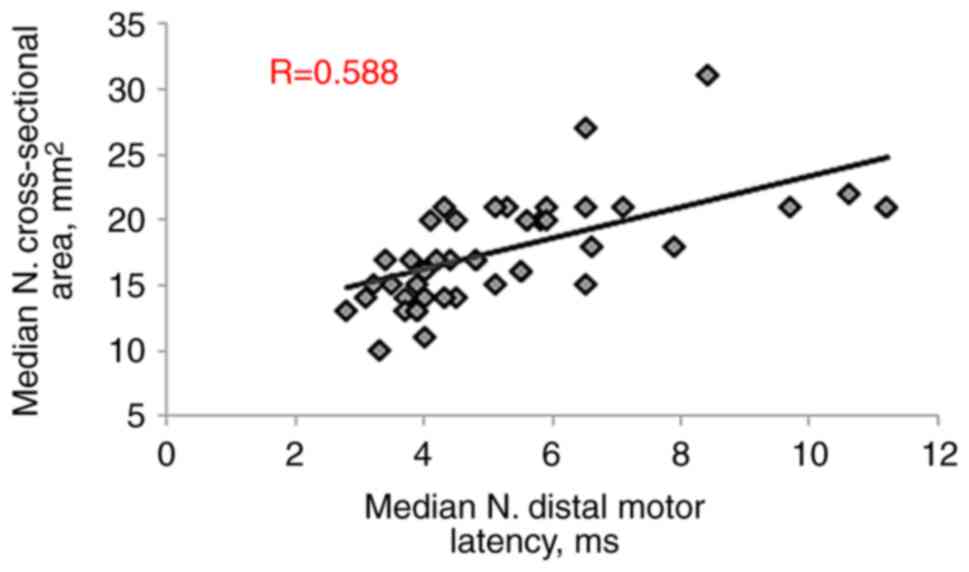

Correlation of CSA-D with

electrophysiological parameters

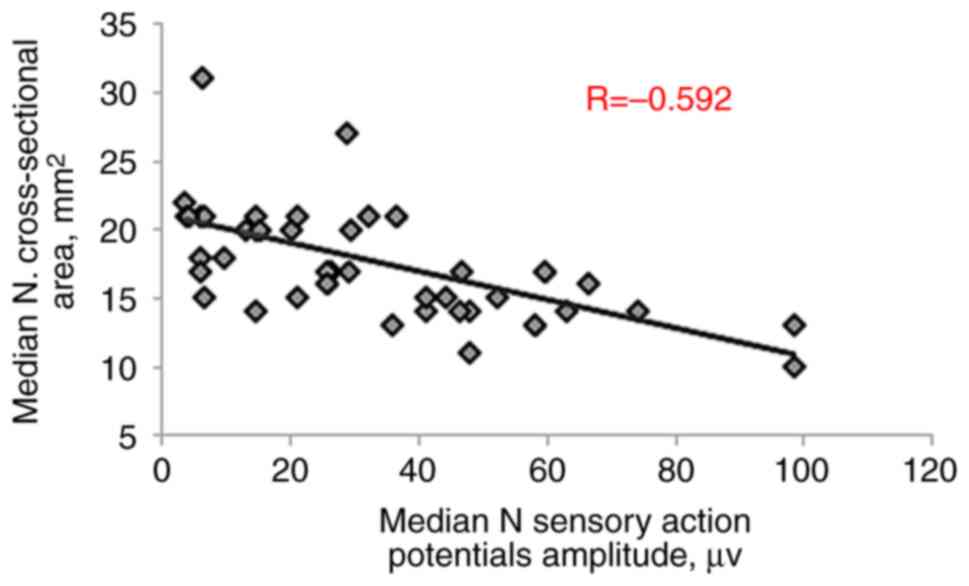

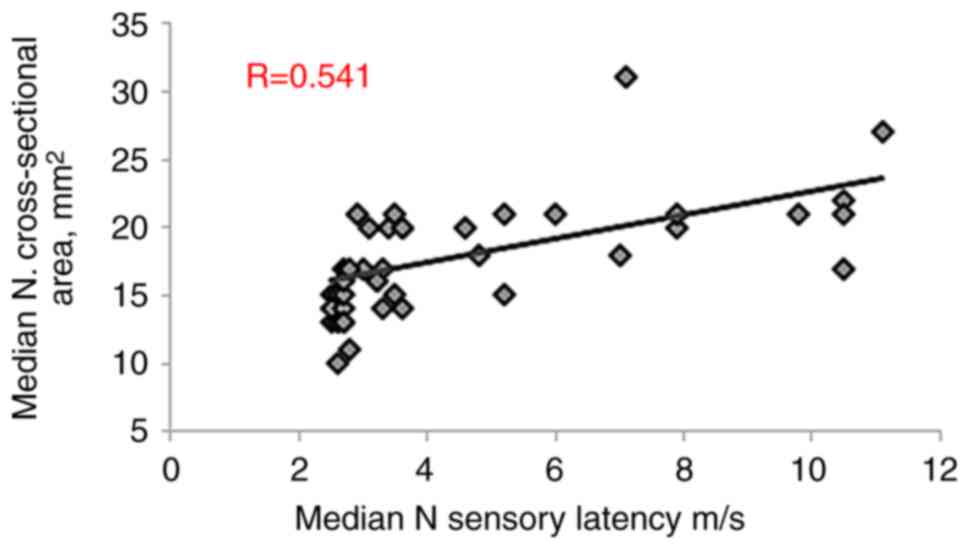

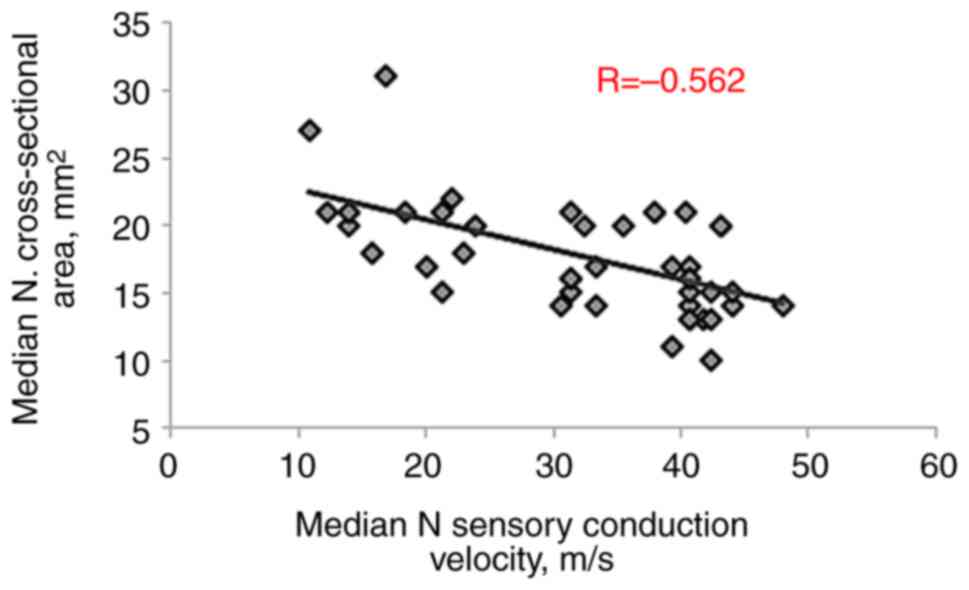

Pearson s correlation analysis was performed to

examine the correlation between the CSA-D and other parameters in

patients with CTS. The CSA-D exhibited a significant positive

correlation with both MN distal motor latency (R=0.588, P<0.001)

and MN sensory latency (R=0.541, P<0.001). Conversely,

significant negative correlations were observed with MN motor

conduction velocity (R=-0.373, P=0.003), sensory action potential

amplitude (R=-0.592, P<0.001) and sensory conduction velocity

(R=-0.562, P<0.001), as presented in Table III and Fig. 3, Fig.

4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6 and Fig. 7.

| Table IIIPearson s correlation between MN

cross sectional area at distal wrist with other parameters in

patients with carpal tunnel syndrome. |

Table III

Pearson s correlation between MN

cross sectional area at distal wrist with other parameters in

patients with carpal tunnel syndrome.

| Variables | Coefficient | P-value |

|---|

| MN. distal motor

latency, msec | 0.588 | <0.001 |

| MN compound muscle

action potential (msec) | -0.215 | 0.098 |

| MN. motor

conduction velocity, msec | -0.373 | 0.003 |

| MN sensory action

potentials amplitude, µv | -0.592 | <0.001 |

| MN sensory latency

msec | 0.541 | <0.001 |

| MN sensory

conduction velocity, msec | -0.562 | <0.001 |

| Age, years | 0.112 | 0.396 |

| Height, cm | 0.091 | 0.489 |

| Weight, kg | 0.099 | 0.453 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2 | 0.178 | 0.175 |

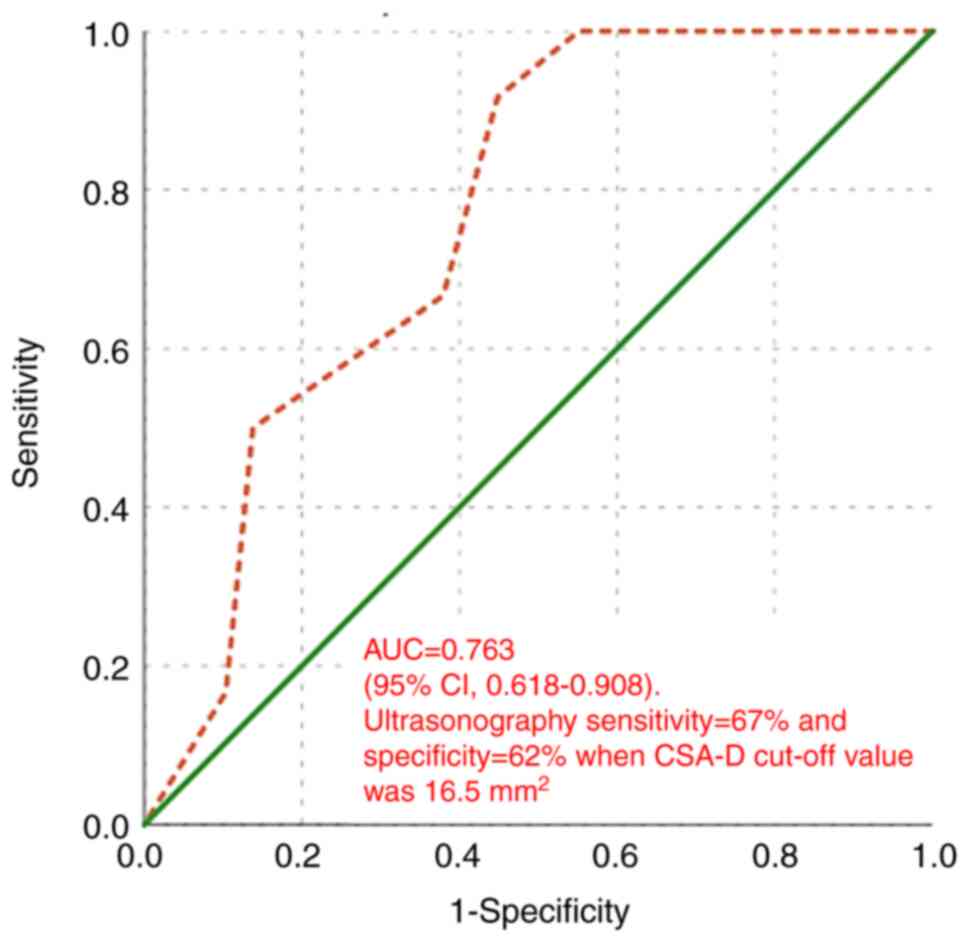

Diagnostic performance of

ultrasonography

The diagnostic accuracy of MN CSA-D measured by US

in detecting and differentiating CTS was assessed using the ROC

curve. When comparing mild and moderate CTS, the area under the

curve (AUC) was 0.763 (95% CI, 0.618-0.908; P=0.009). As shown in

Fig. 8, ultrasonography exhibited

a sensitivity of 67% and a specificity of 62% when the cut-off

value of CSA-D was 16.5 mm2.

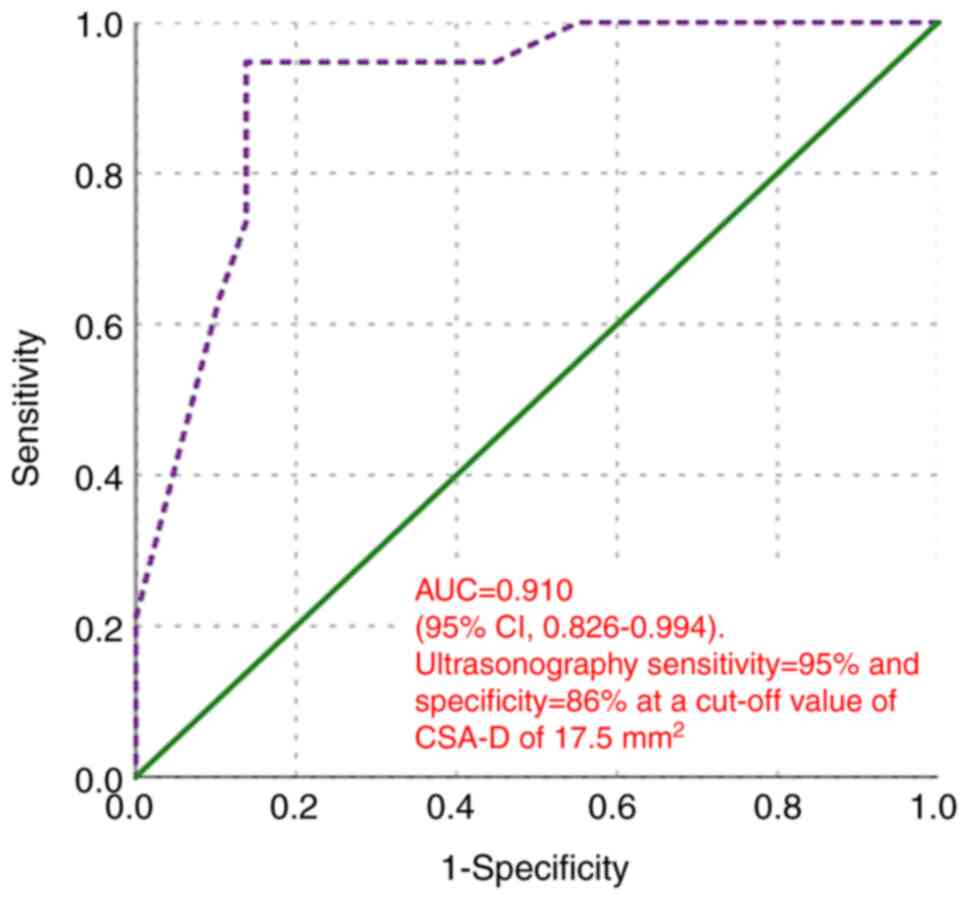

In distinguishing between mild and severe CTS, the

AUC was 0.910 (95% CI, 0.826-0.994; P<0.001). At a cut-off value

of CSA-D of 17.5 mm2, ultrasonography exhibited a

sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 86% (Fig. 9).

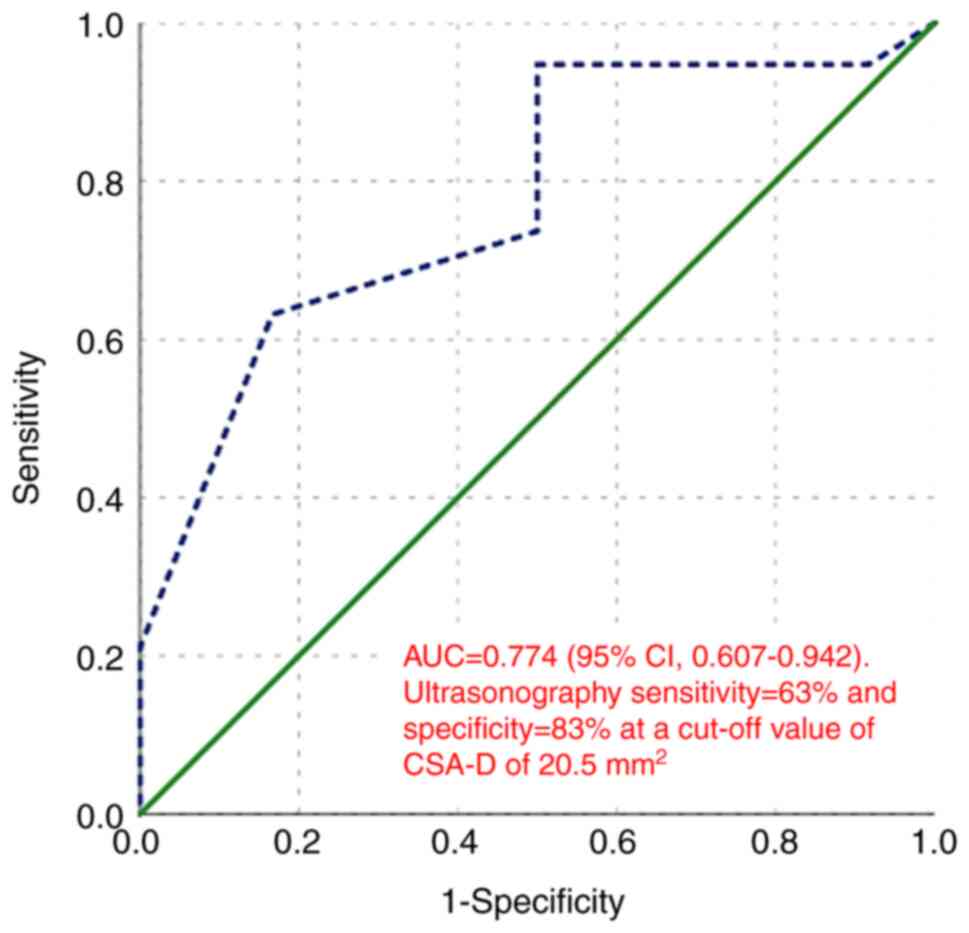

For distinguishing between moderate and severe CTS,

the AUC was 0.774 (95% CI, 0.607-0.942, P=0.011). At a cut-off

value of CSA-D of 20.5 mm2, ultrasonography demonstrated

a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of 83% (Fig. 10).

Discussion

A positive electrodiagnostic test is primarily used

to corroborate the diagnosis of CTS, which is often based on

characteristic clinical signs and symptoms (15). According to recent research, MN

sonography can detect CTS with sensitivity that is comparable to

that of the gold-standard electrophysiological testing (16,17).

The present study identified a positive correlation

between the CSA-D of MN and both MN distal motor latency and

sensory latency. Conversely, the CSA-D demonstrated a significant

negative correlation with MN motor conduction velocity, sensory

action potential amplitude, and sensory conduction velocity. These

results validate the utility of US in diagnosing CTS and align with

findings from other studies (18-21).

Reported cut-off values for the CSA of the MN at the

pisiform bone using US vary widely, ranging from 9 to 14

mm2 (16,22,23)

which affect the sensitivity and specificity of this parameter for

diagnosing CTS. In the present study, the CSA cut-off value was

17.5 mm2. The cutoff value of 17.5 mm2 for

distinguishing mild from severe CTS use in the present study is

higher than the range of 9-14 mm2 frequently reported in

other populations (24-26).

This disparity does not necessarily constitute a contradiction;

rather, it draws attention to significant elements that have an

impact on sonographic findings and the therapeutic application of

these measurements. It is possible that this disparity is due to a

variety of factors, such as: i) The characteristics of the

population: The population in the present study comprised solely of

Iraqi females who had a BMI that was defined as overweight, namely

28.58±3.1 kg/m2. It is a well-established fact that

demographic parameters, such as sex, race and body habitus have an

effect on the size of the nerves. Studies have demonstrated that a

higher BMI is associated with a larger median nerve CSA. This could

potentially result in an upward shift of the ideal diagnostic

cutoff in communities that have a higher prevalence of obesity in

comparison to general populations in which lower cut-off values

were established (27,28). ii) Measurement methodology: While

the present study adhered to standard techniques, subtle

differences in measurement protocols, such as the precise level of

the pisiform bone, the use of the ellipse tracing function vs.

manual trace and the pressure applied with the transducer can

systematically influence the absolute CSA values obtained. The

consistent application of the method used herein ensures internal

validity; however, cross-study comparisons must account for these

potential technical variations (29).

In the present study, US had a sensitivity of 95%

and a specificity of 86%, suggesting that US is most effective in

distinguishing mild from severe CTS. For differentiating mild from

moderate CTS, the sensitivity and specificity at a cut-off value of

16.5 mm2 were 67 and 62%, respectively. In the same

manner, a cut-off value of 20.5 mm2 for moderate to

severe CTS yielded a sensitivity of 63% and a specificity of

83%.

Probably distinct aspects of the process of the

condition are being investigated by ultrasonography and nerve

conduction investigations individually. US is used to examine the

structural reaction of the nerve to external compression, whereas

nerve conduction investigations are used to evaluate the functional

capacity of the nerve to convey information. Rather than being

considered contradictory with one another, these diagnostic tools

ought to be regarded as complementary.

It is possible that the distinct pathological

processes that are present at different phases of the disease are

responsible for the greater efficacy of ultrasonography in

separating mild from severe cases of CTS. On the other hand, the

effectiveness of US in discriminating between mild and moderate

cases is restricted.

The major pathophysiology of CTS is typically

localized demyelination, which is caused by compression and

ischemia in the early (mild) phases of the condition. Despite the

fact that this functional deficit manifests electrophysiologically

as longer sensory and motor latencies, it is possible that it did

not cause a significant and long-lasting structural expansion of

the nerve (9).

There is a possibility that the nerve will exhibit

transitory swelling that is influenced by the symptoms; however,

the average CSA-D in the group with mild CTS in the present study

was only slightly higher than the typical upper limits, which range

from 9-14 mm2. This results in a threshold that is less

sensitive and specific in terms of differentiating between mild and

moderate instances, as the CSA differences between the two types of

cases become less distinct. By contrast, prolonged compression

induces increasingly severe structural alterations as the severity

of CTS increases, including the persistent endoneurial edema, the

disturbance of the blood-nerve barrier, fibrosis, and ultimately,

axonal degeneration (30).

The fact that in the present study, the group with

severe CTS had a significantly higher mean CSA-D (21.37

mm2) provides evidence that the accumulated structural

damage induces nerve swelling that is both chronic and

considerable. Ultrasonography is a powerful instrument that can

differentiate between moderate and severe manifestations of disease

due to the exceptional clarity it possesses.

US is sensitive to the significant nerve damage that

is associated with advanced illness, as evidenced by the fact that

it is able to differentiate between moderate and severe cases of

CTS. It is possible that functional electrophysiological changes,

which NCS is able to detect, may occur prior to lasting

morphological alterations. This is suggested by the observation

that US is not very effective at identifying the early phases of

the condition.

The fact that NCS exposes structural compromise,

while US indicates functional integrity adds validity to the

hypothesis that functional integrity and structural compromise are

two different sorts of information that they provide. As a result

of this, combining the two methods may possibly provide a more

realistic portrayal of the severity of the condition.

The results of the present study demonstrate a

robust correlation between MN CSA and electrophysiologically

assessed disease severity. Nevertheless, additional studies are

required to investigate the impact of sonographic parameters on

patient-reported clinical outcomes. For the purpose of clinical

decision-making, it is essential to use a validated instrument such

as the Boston Carpal Tunnel Questionnaire (BCTQ) (31) to determine whether nerve

enlargement, as shown through ultrasonography, correlates with the

severity of symptoms and functional impairment.

The authors acknowledge that the study population

may not fully represent the complexity of all patients presenting

with CTS-like symptoms in general practice due to the exclusion of

patients with comorbidities, such thyroid disease, polyneuropathy

and cervical radiculopathy. The primary objective of these criteria

was to isolate the association between the morphology of the MN and

its electrical activity in cases of CTS, excluding other disorders

that may mimic or exacerbate CTS symptoms. Cervical radiculopathy

may present with overlapping sensory symptoms (32), whereas polyneuropathy may cause

aberrant nerve conduction tests and widespread nerve enlargement

(33).

The present study had certain limitations which

should be mentioned. First, the sample size was relatively small.

Further multicenter studies with larger cohorts are thus warranted

to validate the proposed cut-off values and improve the

generalizability of the findings. Second, the present study

employed a cross sectional design by selectively enlisting patients

with a clinical suspicion of CTS. This may render the test to

appear more precise than it actually is due to a high pre-test

probability, a phenomenon known as spectrum bias. Third, the

present study only demonstrated a link between the MN sonography

tests and the electrodiagnostic examination. The present study does

not indicate whether NCS or ultrasonography appropriately captures

the clinical manifestations of CTS. Finally, the present study did

not incorporate a correlation with standardized clinical symptom

scores, such as the BCTQ. Therefore, while CSA may be related to

electrophysiological severity, its direct association with the

subjective experiences of patients, such as pain, numbness and

functional limitations remains a key area for future

investigations.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that

CSA-D and NCS are positively correlated, and the CSA-D is more

sensitive in differentiating between mild and severe CTS, than

between mild and moderate CTS. As regards the evaluation of

structural and functional integrity, US and NCS provide

complimentary information. When used in conjunction, they provide a

more comprehensive evaluation of the nerve, which may be useful in

clinical therapy and in the stratification of prognostic factors.

Future research is required to focus on correlating these objective

measures with clinical symptom scores in order to fully integrate

ultrasonography into patient-centered care pathways.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

JMK was involved in the conception and design of the

study, in the literature search, in clinical analyses, in data

analysis and in statistical analysis, as well as in manuscript

preparation and in the reviewing of the manuscript. AMJAM was

involved in the conception and design of the study and in data

analysis, as well as in manuscript preparation and in the reviewing

of the manuscript. IAM and AKA were involved in the conception and

design of the study, manuscript preparation and in the reviewing of

the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript. All authors confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Research approval was obtained from the

institutional Review Board of Al-Khadimain Teaching Hospital

(Reference no. 5563 on April 24, 2023). A written informed consent

to participate in the study as specified in the Declaration of

Helsinki was obtained from each patient.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ghasemi M, Masoumi S, Ansari B,

Fereidan-Esfahani M and Mousavi SM: Determination of cut-off point

of cross-sectional area of median nerve at the wrist for diagnosing

carpal tunnel syndrome. Iran J Neurol. 16:164–167. 2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ibrahim I, Khan WS, Goddard N and Smitham

P: Carpal tunnel syndrome: A review of the recent literature. Open

Orthop J. 6:69–75. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Park JS, Won HC, Oh JY, Kim DH, Hwang SC

and Yoo JI: Value of cross-sectional area of median nerve by MRI in

carpal tunnel syndrome. Asian J Surg. 43:654–659. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Fowler JR, Munsch M, Tosti R, Hagberg WC

and Imbriglia JE: Comparison of ultrasound and electrodiagnostic

testing for diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome: Study using a

validated clinical tool as the reference standard. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 96(e148)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Al-Hashel JY, Rashad HM, Nouh MR, Amro HA,

Khuraibet AJ, Shamov T, Tzvetanov P and Rousseff RT: Sonography in

carpal tunnel syndrome with normal nerve conduction studies. Muscle

Nerve. 51:592–597. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Suk JI, Walker FO and Cartwright MS:

Ultrasonography of peripheral nerves. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep.

13(328)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Nkrumah G, Blackburn AR, Goitz RJ and

Fowler JR: Ultrasonography findings in severe carpal tunnel

syndrome. Hand (NY). 15:64–68. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chen X, Cao J, Lao J, Liu A and Rui J:

Evaluation of electrophysiological examinations for the diagnosis

of carpal tunnel syndrome. J Orthop Surg Res.

20(680)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Werner RA and Andary M: Carpal tunnel

syndrome: Pathophysiology and clinical neurophysiology. Clin

Neurophysiol. 113:1373–1381. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Joshi A, Patel K, Mohamed A, Oak S, Zhang

MH, Hsiung H, Zhang A and Patel UK: Carpal tunnel syndrome:

Pathophysiology and comprehensive guidelines for clinical

evaluation and treatment. Cureus. 14(e27053)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Pelosi L, Arányi Z, Beekman R, Bland J,

Coraci D, Hobson-Webb LD, Padua L, Podnar S, Simon N, van Alfen N,

et al: Expert consensus on the combined investigation of carpal

tunnel syndrome with electrodiagnostic tests and neuromuscular

ultrasound. Clin Neurophysiol. 135:107–116. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zivkovic S, Gruener G, Arnold M, Winter C,

Nuckols T and Narayanaswami P: the Quality Improvement Committee of

the American Association of Neuromuscular & Electrodiagnostic

Medicine. Quality measures in electrodiagnosis: Carpal tunnel

syndrome-An AANEM quality measure set. Muscle Nerve. 61:460–465.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Kanagasabai K: Ultrasound of median nerve

in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome-correlation with

electrophysiological studies. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 32:16–29.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

AAOS. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome: Clinical

Practice Guideline on Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, 2024. Available from:

https://www.aaos.org/quality/quality-programs/upper-extremity-programs/carpal-tunnel-syndrome/.

|

|

15

|

Vo NQ, Nguyen THD, Nguyen DD, Le TB, Le

NTN and Nguyen TT: The value of sonographic quantitative parameters

in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome in the Vietnamese

population. J Int Med Res. 49(3000605211064408)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Billakota S and Hobson-Webb LD: Standard

median nerve ultrasound in carpal tunnel syndrome: A retrospective

review of 1,021 cases. Clin Neurophysiol Pract. 2:188–191.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

El-Najjar AR, Abu-Elsoaud AM, Sabbah DA

and Zeid AF: Emerging role of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of

carpal tunnel syndrome: Relation to risk factors, clinical and

electrodiagnostic severity. Egypt Rheumatol. 43:341–345. 2021.

|

|

18

|

Baiee RH, Al-Mukhtar NJ, Al-Rubiae SJ,

Hammoodi ZH and Abass FN: Neurophysiological findings in patients

with carpal tunnel syndrome by nerve conduction study in comparing

with ultrasound study. J Nat Sci Res. 5:111–128. 2015.

|

|

19

|

Mohamed RE, Amin MA, Aboelsafa AA and

Elsayed SE: Contribution of power Doppler and gray-scale ultrasound

of the median nerve in evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome. Egypt

J Radiol Nucl Med. 45:191–201. 2014.

|

|

20

|

Elnady B, Rageh EM, Ekhouly T, Fathy SM,

Alshaar M, Fouda ES, Attar M, Abdelaal AM, El Tantawi A, Algethami

MM and Bong D: Diagnostic potential of ultrasound in carpal tunnel

syndrome with different etiologies: Correlation of sonographic

median nerve measures with electrodiagnostic severity. BMC

Musculoskelet Disord. 20(634)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chan KY, George J, Goh KJ and Ahmad TS:

Ultrasonography in the evaluation of carpal tunnel syndrome:

Diagnostic criteria and comparison with nerve conduction studies.

Neurol Asia. 16:57–64. 2011.

|

|

22

|

Ng AWH, Griffith JF, Lee RKL, Tse WL, Wong

CWY and Ho PC: Ultrasound carpal tunnel syndrome: Additional

criteria for diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 73:214.e11–214.e18.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Gelfman R, Melton Iii LJ III, Yawn BP,

Wollan PC, Amadio PC and Stevens JC: Long-term trends in carpal

tunnel syndrome. Neurology. 72:33–41. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Duncan I, Sullivan P and Lomas F:

Sonography in the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. AJR Am J

Roentgenol. 173:681–684. 1999.

|

|

25

|

Cartwright MS, Hobson-Webb LD, Boon AJ,

Alter KE, Hunt CH, Flores VH, Werner RA, Shook SJ, Thomas TD,

Primack SJ, et al: Evidence-based guideline: Neuromuscular

ultrasound for the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Muscle

Nerve. 46:287–293. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wong SM, Griffith JF, Hui ACF, Lo SK, Fu M

and Wong KS: Carpal tunnel syndrome: Diagnostic usefulness of

sonography. Radiology. 232:93–99. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Klauser AS, Faschingbauer R, Bauer T, Wick

MC, Gabl M, Arora R, Cotton A, Martinoli C and Jaschke WR:

Entrapment neuropathies II: carpal tunnel syndrome. Semin

Musculoskelet Radiol. 14:487–500. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Won SJ, Kim BJ, Park KS, Yoon JS and Choi

H: Reference values for nerve ultrasonography in the upper

extremity. Muscle Nerve. 47:864–871. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Seok JI: A beginner s guide to

peripheral nerve ultrasound. Ann Clin Neurophysiol. 24:46–52.

2022.

|

|

30

|

Aboonq MS: Pathophysiology of carpal

tunnel syndrome. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 20:4–9. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Levine DW, Simmons BP, Koris MJ, Daltroy

LH, Hohl GG, Fossel AH and Katz JN: A self-administered

questionnaire for the assessment of severity of symptoms and

functional status in carpal tunnel syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am.

75:1585–1592. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kaddoori HG: Electrophysiological study in

patients with cervical radiculopathy. Iraqi J Med Sci: Jun 6, 2024

(Epub ahead of print).

|

|

33

|

Nasr-Eldin YK, Cartwright MS, Hamed A, Ali

LH and Abdel-Nasser AM: Neuromuscular ultrasound in

polyneuropathies. J Ultrasound Med. 43:1181–1198. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|