Introduction

Appendages of the fetus, included the amnion, are

normally discarded after delivery as medical waste. A large

quantity of human amniotic epithelial and mesenchymal stem cells

can be obtained non-invasively from the amniotic membrane, which

represents an advantageous source of cells for cell therapy

(1).

In vivo studies have previously reported the

therapeutic potential of stem cells using various animal models

including hindlimb ischemia (2,3),

wound healing (4,5) and myocardial infarction (6,7).

However, in many cases, the frequency of stem cell engraftment and

the number of newly generated adult cells, either by

transdifferentiation or cell fusion, appear to be too low to

explain the significant improvement described (8,9).

Meanwhile, tissue concentrations of proteins, including vascular

endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor

(bFGF) are increased in the injured areas treated with stem cells

(10). There is a growing body of

evidence supporting the hypothesis that paracrine mechanisms

mediated by factors released by pluripotent stem cells play an

essential role in the reparative process (11,12). This paracrine effect renders these

cells an attractive therapeutic source for regenerative

medicine.

Stem cells may be beneficial in various

cell-therapeutic approaches where they function by promoting the

survival of endothelial cells (13,14), the stabilization of pre-existing

vessels (15), and the

revascularization of ischemic tissues (2,3).

Given that the natural response to tissue repair is such a complex

process, many growth factors may be involved. Thus, a great deal of

interest has arisen in angiogenetic factors found in stem cells,

such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), epidermal growth factor

(EGF), heparin binding EGF like growth factor (HB-EGF) and insulin

growth factor-1 (IGF-1), and the paracrine effects which are

significantly related to the angiogenesis of endothelial cells

(3,16–18).

The aim of the present study was: i) to isolate and

characterize cells from human amnions; ii) to investigate the

biological potential and behavior of these cells in regards to the

function of endothelial cells in vivo and in vitro;

and iii) to examine the variations in the expression profile of

growth factors in different human amnion-derived cell types.

Materials and methods

Ethics

The amnion samples discarded after Caesarean

sections were collected from the Department of Obstetrics and

Gynecology, The First at Hospital of China Medical University

(Shenyang, China). This study was approved by the Ethics Committee

of the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University.

Written informed consent was obtained from all of the patients

prior to their participation. C57BL/6J mice were obtained from the

Experimental Animal Centre of China Medical University. All

experiments and animal care were approved by the Ethics Committee

of the First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University.

Cells and cell culture

Human aorta endothelial cells

(hAoECs)

hAoECs were purchased from ScienCell (Carlsbad, CA,

USA) and cells at passage 4–6 were used for in vitro

experiments. The cells were cultured in Endothelial Basal Media-2

(EBM-2) with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and Endothelial Cell

Growth Supplement (ECGS) (EGM-2; ScienCell).

Human amniotic epithelial cells

(hAECs)

Primary cell culture was performed as described

previously (5). Briefly, amnions

were manually separated and washed with phosphate-buffered saline

(PBS) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin.

Amnions were then incubated with 0.25% trypsin solution for 30 min.

This process was repeated three times. Supernatants were collected

and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 rpm to obtain a cell pellet.

Those cells were plated on a culture flask (designated as hAEC P0)

in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; HyClone, Logan, UT,

USA), and 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin. In this study,

hAECs at passage 2–3 were used.

Human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells

(hAMSCs)

The amnion tissue was cut into small pieces, and

then incubated with 1 mg/ml collagenase IV (Sigma-Aldrich, St.

Louis, MO, USA) and 0.1 mg/ml DNase (Takara Bio, Inc., Shiga,

Japan) at 37°C for 20 min. FBS was then added to stop digestion,

and supernatants were filtered through a cell strainer (200

μm) and centrifuged for 5 min at 1,000 rpm. Cells were

plated on a culture flask (designated as hAMSC P0) in DMEM

containing 10% FBS (both from HyClone), 10 mmol/ml FGF-2

(PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ, USA), and 100 U/ml penicillin and

streptomycin. The culture medium was changed 48 h later. In this

study, hAMSCs at passages 3–6 were used for the functional

experiment.

The differentiation capacity of

amniotic cells

hAECs (passages 2) and hAMSCs (passage 3) were

tested for their ability to differentiate into osteocytes,

chondrocytes and adipocytes.

To induce differentiation into osteocytes, the cells

were cultured in osteocyte differentiation medium: 1 μM

dexamethasone, 50 μg/ml L-ascorbate, and 10 mM

β-glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM supplemented with 10%

FBS. After 14 days of differentiation, the cells were fixed and

stained with Alizarin Red S (Cyagen, Guangzhou, China).

To induce differentiation into adipocytes, the cells

were cultured with adipocyte differentiation medium: 0.5 mM

3-isobutyl-1-methyl xanthine, 1 μM dexamethasone, 200

μM indomethacin, and 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich)

in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. After 14 days of

differentiation, the cells were stained with Oil Red O

(Cyagen).

To induce differentiation into chondrocytes, the

cells were cultured with chondrocyte differentiation medium: 0.1

μM dexamethasone, 50 μg/ml L-ascorbate, 100

μg/ml sodium pyruvate (Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 ng/ml

transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (PeproTech) in DMEM

supplemented with 10% FBS. After 14 days of differentiation, the

cells were stained with Alcian blue (Cyagen).

Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence

of cells

Flow cytometry and immunofluorescence were used to

identify the characteristics of the cells and detect stem

cell-related cell surface markers. For flow cytometry, the cells

(106 cells/100 μl) were collected and incubated

with monoclonal phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated antibodies for CD29

(cat. no. 303003), CD31 (cat. no. 303105), CD34 (cat. no. 343505),

CD44 (cat. no. 338807), CD45 (cat. no. 368509), CD49d (cat. no.

304303), CD73 (cat. no. 344003), CD90 (cat. no. 32810), CD105 (cat.

no. 323205), HLA-DR (cat. no. 307605), SSEA-4 (cat. no. 330405),

SOX-2 (cat. no. 656103) and OCT-4 (cat. no. 653703) (BioLegend, San

Diego, CA, USA) for 30 min on ice. Appropriate isotype-matched

antibodies were used as negative controls (BD Biosciences, San

Jose, CA, USA). Data from 10,000 viable cells were acquired. List

mode files were analyzed by FCS Express software (BD Biosciences).

For immunofluorescence, cells growing on the glass slide were

stained with anti-cytokeratin 19 (cat. no. ab52625, 1:200; Abcam,

Cambridge, MA, USA) and secondary antibody (cat. no. A-11034,

1:200; Alexa 488, donkey anti-rabbit; Life Technologies, Carlsbad,

CA, USA). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (Beyotime, Shanghai,

China). Cells on the glass slide were photographed using an

inverted fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen,

Germany).

Preparation of conditioned medium

To generate conditioned medium (CdM), hAoECs, hAMSCs

and hAECs were cultured with EGM-2. After the cells had reached

~50–60% confluence (~4×105 cells in 25 cm2

flask), cultures were gently rinsed three times with PBS and the

medium was replaced with EGM-2 or EBM-2. After 48 h, the CdM

(EGM-2) obtained from each plate was then collected, pooled for

each cell type, centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 5 min, filtered (0.2

μm) to remove cellular debris, stored at −80°C and

supernatants were used as CdM-hAoEC, CdM-hAEC and CdM-hAMSC for

cell assays. Positive control, non-conditioned medium (non-CdM) was

generated in the same way as above, except that no cells were

cultured in the plates. Batches of 2X concentrated CdM (EBM-2) were

also prepared for the in vivo Matrigel plug assay. In this

way, a final concentration of 1X CM after 1:1 dilution in Matrigel

was obtained.

Cell viability assays

For the growth curves of hAECs and hAMSCs, cells

(5×103/well) were plated in 96-well plates with EGM-2.

Cells were cultured for 7 days, and cell proliferation was measured

using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) every

day according to the manufacturer's protocol. For determining the

effect of CdM on endothelial cell viability, hAoECs were cultured

in EGM-2 without FBS for 24 h to arrest mitosis. Then, hAoECs

(2×104/well) were plated in 96-well plates, the medium

was replaced with CdM-hAoEC (control), CdM-hAEC, CdM-hAMSC and

EGM-2 (positive control). Cells were cultured for 24 h, after which

hAoEC proliferation was measured using the CCK-8 (Dojindo). In

brief, cells were incubated with CCK-8 for 1.5 h at 37°C. The

staining intensity in the medium was measured by determining the

absorbance at 450 nm.

Cell cycle analysis

The effect of CdM on cell cycle distribution was

determined by flow cytometry. Briefly, hAoECs were treated with

different CdM for 24 h. Cells were suspended, washed with PBS,

centrifuged, and fixed in 70% ethanol at −20°C overnight. Cells

were then resuspended in 500 μl of dyeing buffer containing

10 μl RNase A and 25 μl PI (Beyotime). Cells were

incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. A total of

1×104 cells were subjected to cell cycle analysis using

a flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Scratch wound closure assay

hAoECs (500,000 cells/insert) were plated in 6-well

plates, and at 80–90% confluence, at 12 h after plating, a scratch

of ~0.5 mm was created using a sterile pipette tip. Each well was

washed twice with PBS and then the cell culture medium was either

replaced with CdM-hAoEC (control), CdM-hAEC, CdM-hAMSC or EGM-2

(positive control). Cell migration into the scratch was

photographed at 0, 6 and 24 h using an inverted microscope

(Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Results were analyzed with Image-Pro Plus

software 6.0 (IPP; Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA).

The results are presented as the percentage of wound healing, which

was calculated as follows: [Wound area (initial) − Wound area

(final)]/Wound area (initial) × 100% (5).

Transwell migration assay

Cell migration assays were performed using inserts

with 8-μm pore-sized membranes in a 24-well plate (Corning

Costar, Lowell, MA, USA). CdM-hAoEC (control), CdM-hAEC, CdM-hAMSC

and EGM-2 (positive control) were placed in the bottom chamber.

hAoECs were resuspended in serum-free EGM-2, transferred onto the

filter of the insert (50,000 cells/insert) and incubated at 37°C in

5% CO2 for 6 or 24 h. Non-migratory cells were removed

from the upper side of the filter. Migratory cells at the bottom

side of the filter were fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA), stained

with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and photographed. Cells were

counted from eight randomly selected regions/well.

Matrigel tube formation assay

To evaluate the tube formation potential, hAoECs

were seeded with each CdM derived from different cells, at a

concentration of 2.5×104 cells/well in growth

factor-reduced basement membrane matrix gel (Matrigel; BD

Biosciences)-coated 96-well plates. After 6, 24 and 48 h of

incubation, representative fields were photographed using inverted

microscopy (Olympus), and branching points from each sample were

examined with Image-Pro Plus software 6.0.

Matrigel plug assays

The CdM (EBM-2) was mixed with 250 μl of

liquid Matrigel-reduced growth factor (BD Matrigel 356230) at a

ratio of 1:1 at 4°C. Mice (8-weeks old) received a total of 500

μl of this mixture subcutaneously in the dorsal region,

generating Matrigel plugs when warmed to body temperature. Plugs

were recovered 1 week later.

qPCR assay for growth factor and

cytokine detection

Total RNA was extracted, using TRIzol reagent

(Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), from hAECs and hAMSCs cultured

with EGM-2 complete medium. RNA concentration was determined by

NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). cDNA

was synthesized using PrimeScript™ RT reagent (Takara Bio, Inc.).

Reactions were performed using the SYBR PrimeScript RT-PCR kit

(Takara Bio, Inc.) with an ABI 7500 Sequence Detection system

(Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). As an internal control,

the β-actin level was quantified in parallel with the target genes.

Normalization and fold-changes were calculated using the ΔΔCq

method. The primers used for real-time PCR are the following:

5′-CTGTCTAATGCCCTGGAGCC/ACGCGAGTCTGTGTTTTTGC-3′ for VEGFA;

5′-TCAGCCAGCAGATGGGAATG/TCAGGGCTGTATGG GCAAAG-3′ for EGF;

5′-GGCTGTACTGCAAAAACGGG/TAGCTTGATGTGAGGGTCGC-3′ for bFGF;

5′-CAATGCCTCTGGTTCCCCTT/TGTTCCCTTGTAGCTGCGTC-3′ for HGF;

5′-AGTTCTCTCGGCACTGGTGA/TAGCAGCTG GTCCGTGGATA-3′ for HB-EGF;

5′-ATCAGCAGTCTTCCAACCCA/GAGATGCGAGGAGGACATGG-3′ for IGF-1;

5′-AGGATTCCTATGTGGGCGAC/ATAGCACAGCCTGGATAGCAA-3′ for β-actin.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

(ELISA) detection of angiogenetic growth factors

Conditioned medium from hAoECs, hAECs and hAMSCs

were collected after 48 h incubation. The concentration of

cytokines in the different CdM was measured using sandwich ELISA

kits (VEGFA, EGF, bFGF, HGF, HB-EGF and IGF-1; R&D Systems,

Minneapolis, MN, USA). After media were collection, the cells were

counted. ELISA values were corrected for total cell numbers.

Positive control-conditioned medium was also assayed.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed 3 times on amniotic

cells and with CdM from 3 different donors. The data are shown as

the means ± SDs. Comparisons between groups were analyzed using

t-test. Comparisons of parameters for more than three groups were

made by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the

Bonferroni test. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS

17.0 computer software. P-values <0.05 were considered to

indicate statistically significant differences.

Results

Characterization of hAECs and hAMSCs

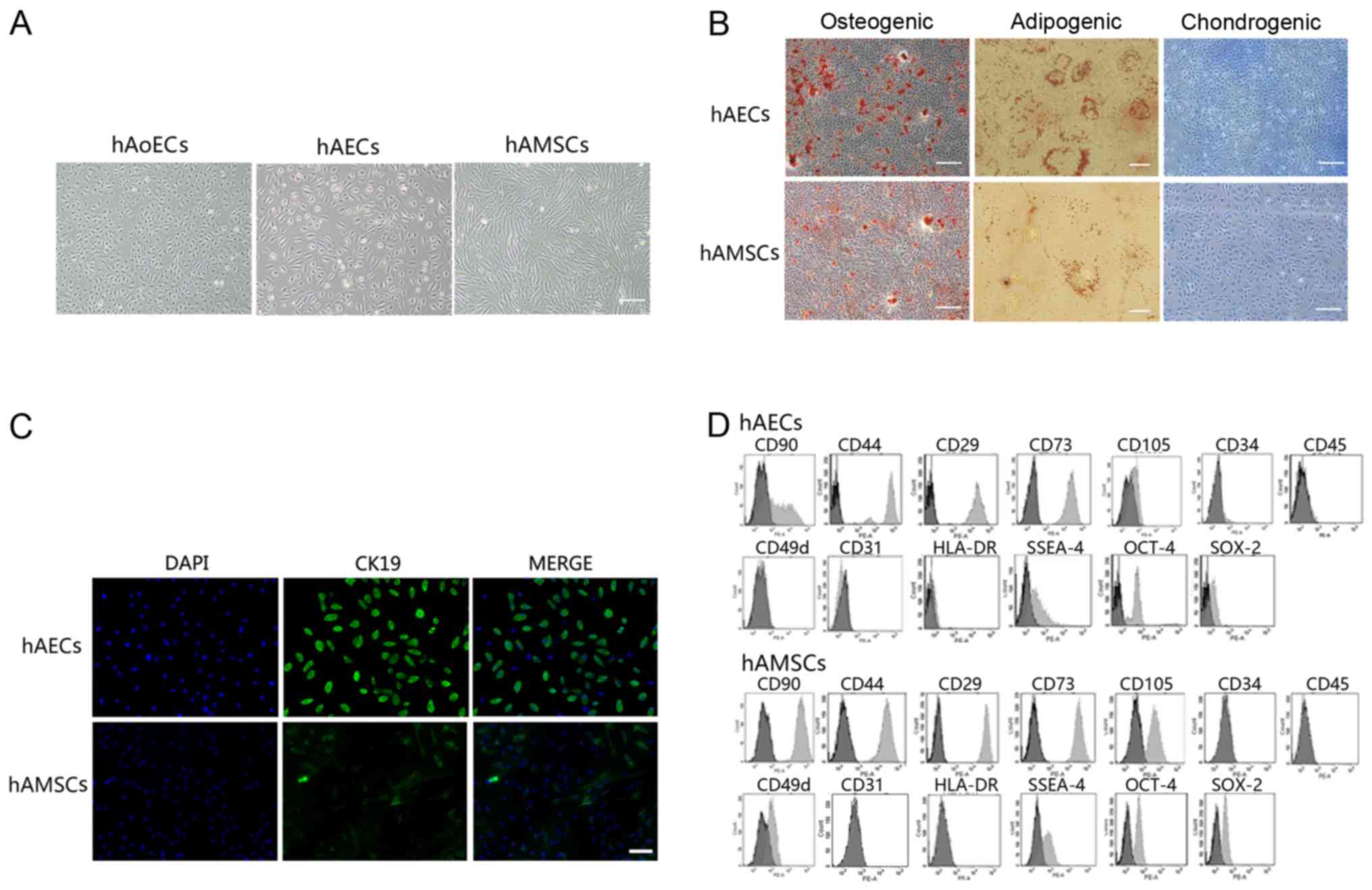

hAECs exhibited a cobblestone-like morphology,

similar to hAoECs. Cultured hAMSCs showed a spindle fibroblast-like

morphology (Fig. 1A). Flow

cytometry and immunofluorescence revealed the expression of surface

markers. hAECs were positive for CK19, CD29, CD44, CD73, CD90 and

CD105, but were negative for CD31, CD34, CD45 and CD49d. hAMSCs

were positive for CD29, CD44, CD49d, CD73, CD90 and CD105, but were

negative for CK19, CD31, CD34 and CD45 (Fig. 1C and D). In addition, amniotic

cells were all negative for HLA-DR, indicating that these cells

possess low immunogenicity. To confirm the stem cell

characteristics of hAECs and hAMSCs, we performed FACS analysis

using embryonic stem and germ cell markers. Amniotic cells were all

found to express SSEA-4, SOX2 and OCT-4 (Fig. 1D). These results are consistent

with previously reported data (1,19,20). In addition, hAECs and hAMSCs could

differentiate into osteocytes, adipocytes and chondrocytes, as

demonstrated by positive Alizarin Red, Oil Red O and Alcian blue

staining, respectively (Fig. 1B),

which indicated that cultured amniotic cells possess stem cell

characteristics.

Culture medium from hAMSCs enhances

proliferation ability

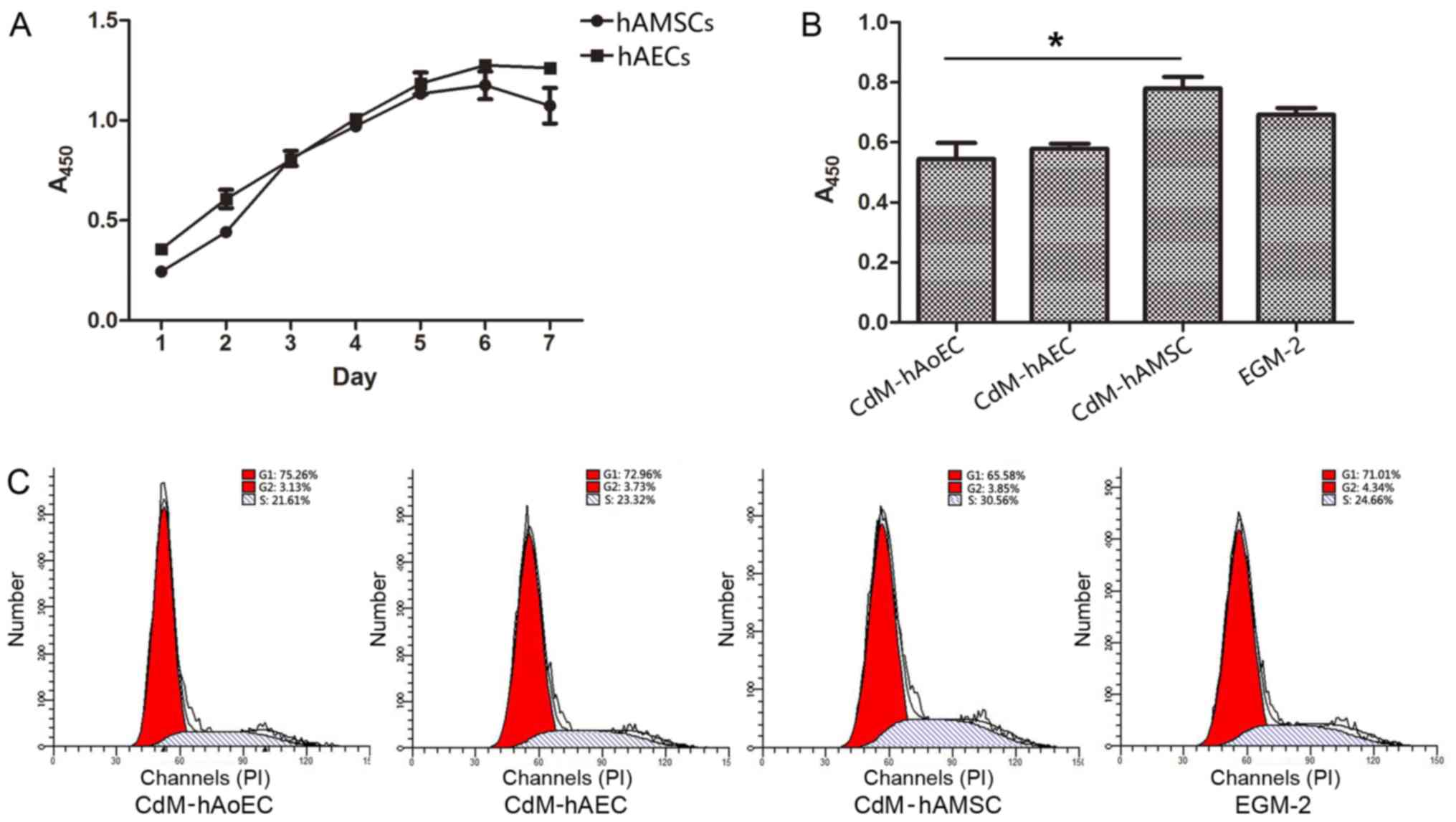

We tested the growth kinetics of hAECs and hAMSCs.

Our data showed that when cultured with EGM-2, cells obtained from

the same amnion had a similar proliferation ability/day (Fig. 2A). Since the proliferation of

hAoECs is an important aspect of angiogenesis, we compared the

proliferation ability of hAoECs when stimulated with different

CdMs. The CCK-8 assay revealed that hAoECs cultured in CdM-hAMSC

showed enhanced proliferation compared with the other CdMs, even

the positive control EGM-2. However, there was no significant

difference in hAoEC proliferation between CdM-hAEC and CdM-hAoEC

(Fig. 2B). In order to further

confirm the effect of CdM on the proliferation ability of hAoECs,

we examined the effect of CdM on cell cycle distribution using flow

cytometry. Compared to the basal level (21.61±1.54%), hAoECs

treated with CdM-hAMSC led to a marked increase in the number of

cells in the S phase (30.56±1.91%) (Fig. 2C). There was no statistical

difference, however, when hAoECs were treated with CdM-hAEC or

CdM-hAoEC.

Culture medium from hAECs enhances

migration ability

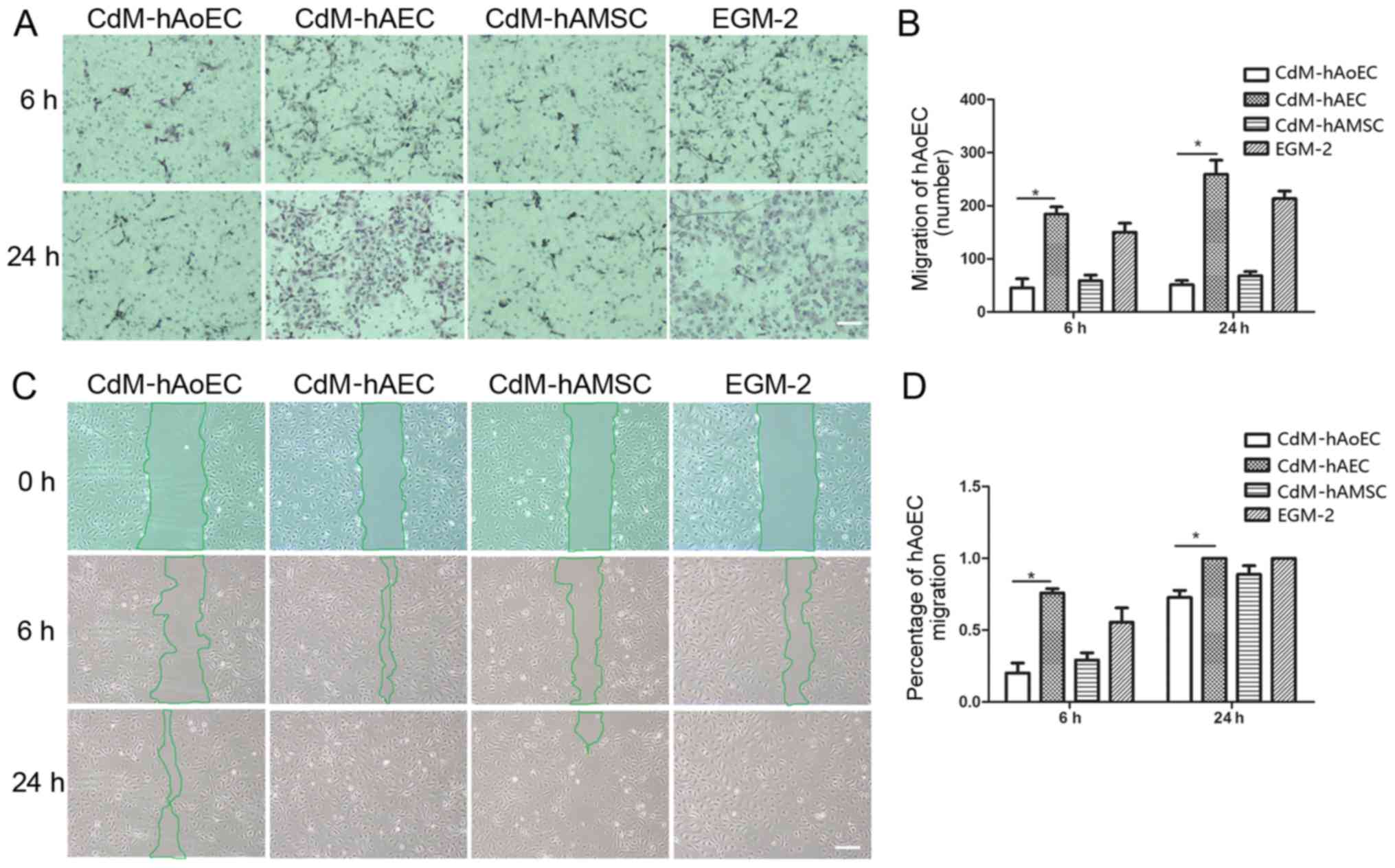

In order to examine whether CdMs exhibited

biological effects relevant to hAoEC migration, we compared the

effects of the different CdMs on migration by means of scratch and

Transwell assays. The images showed that hAoEC migration into the

scratch wound area was accelerated when cultured with CdM-hAEC

(75.86±3.06% CdM-hAEC vs. 29.16±5.12% CdM-hAMSC; P<0.05,

20.11±7.04% CdM-hAoEC; n=3/group) (Fig. 3C). In Transwell cell migration

assays, our results revealed that CdM-hAEC significantly increased

the rate of hAoEC migration compared with CdM-hAMSC and CdM-hAoEC

(184.01±33.66 CdM-hAEC vs. 58.82±23.99 CdM-hAMSC; P<0.05,

45.20±30.04 CdM-hAoEC; n=3/group) (Fig. 3A).

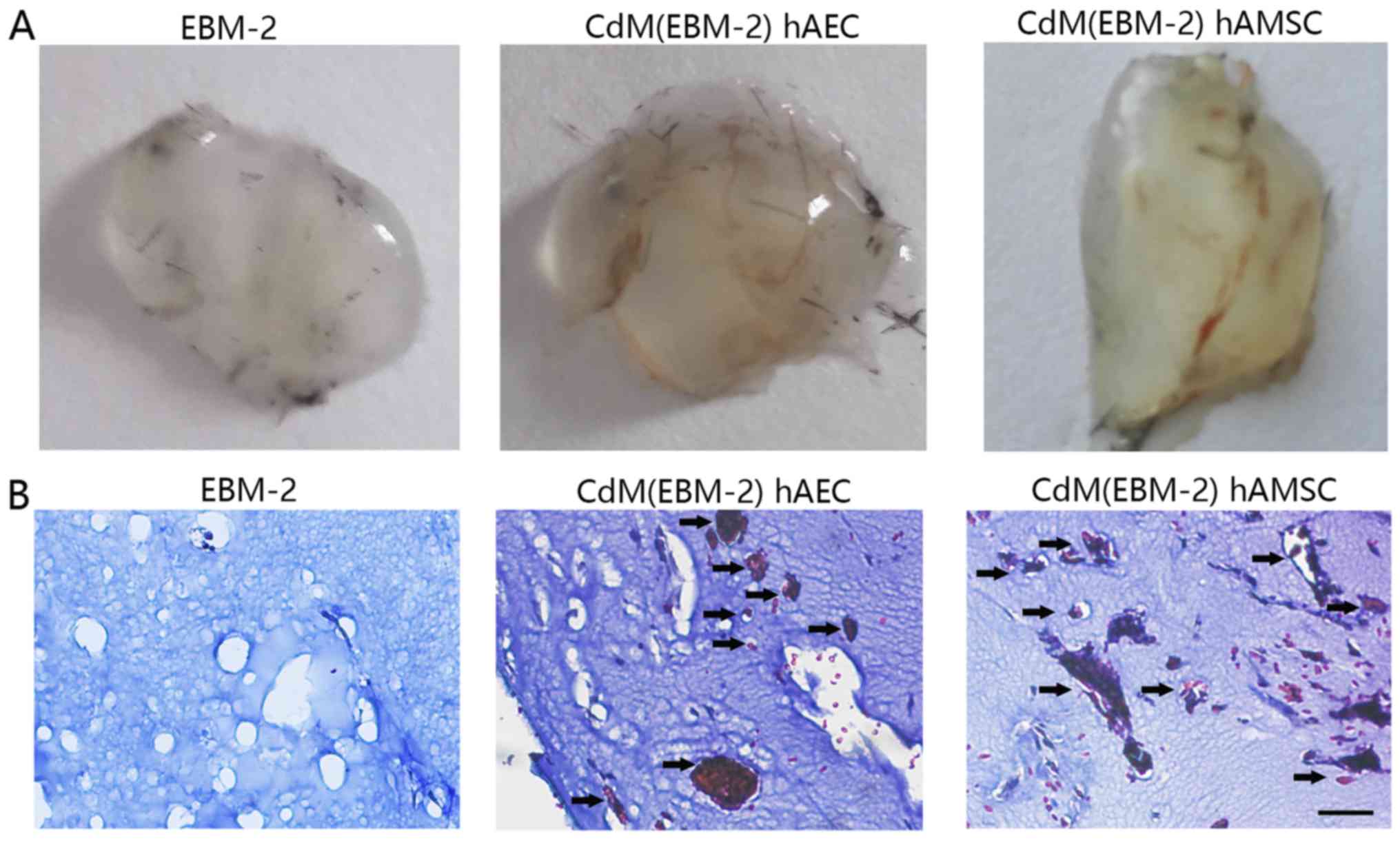

Angiogenesis assay: network

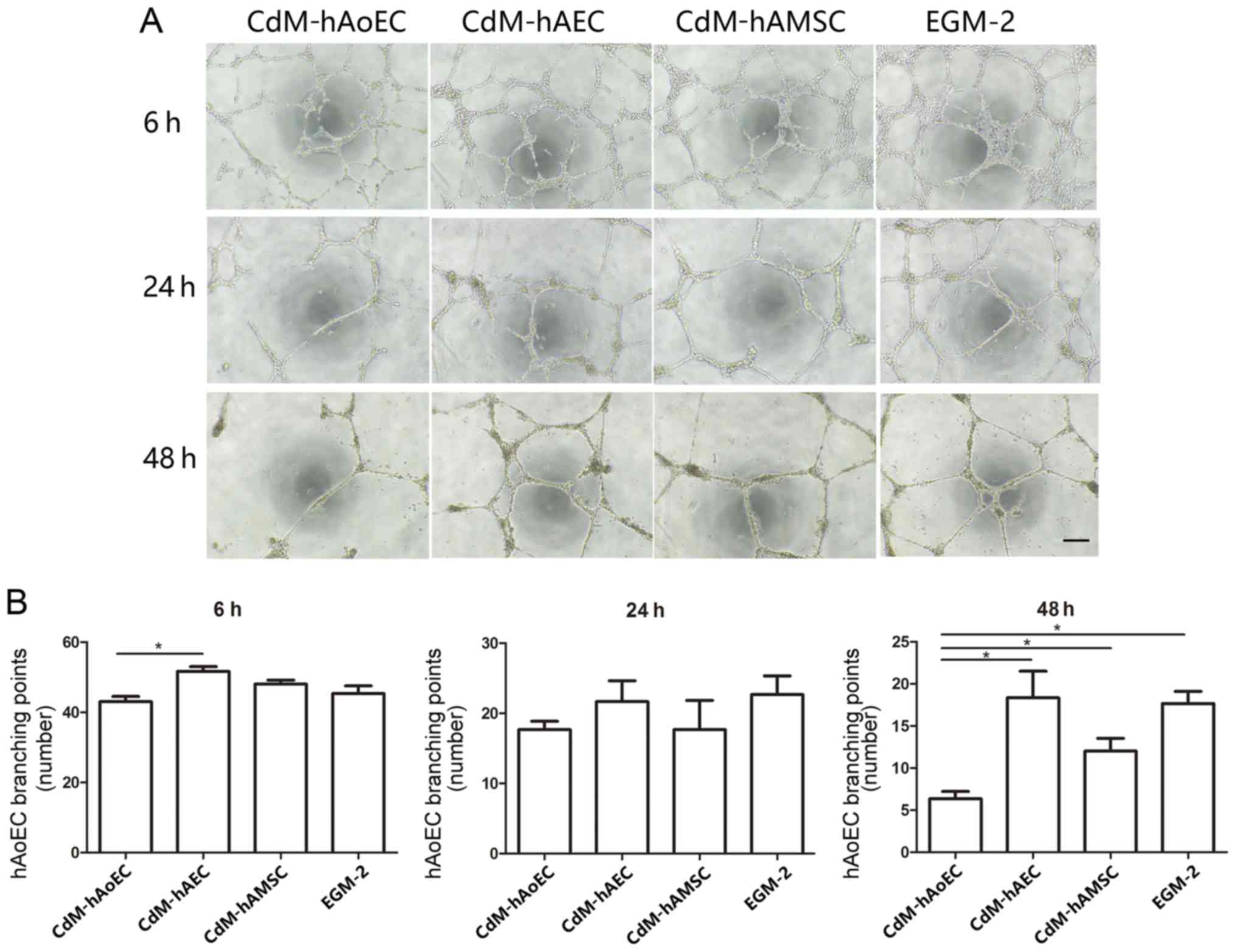

formation

The Matrigel assay is a commonly used method to

evaluate network formation by endothelial cells and was applied to

investigate whether induced CdM were also involved in forming

networks. After 6 h, the addition of CdM-hAEC to hAoECs supported

the formation of network-like structures in the Matrigel assay, to

a greater extent than CdM-hAoEC. After 24 h, the addition of

CdM-hAEC to hAoECs still supported the formation of network-like

structures, but this was not statistically significant. While

networks formed by endothelial cells in CdM-hAoEC had disintegrated

after 48 h, networks formed by hAoECs cultured with CdM-hAEC and

CdM-hAMSC were still stable (Fig.

4). To examine the angiogenic potential of CdM in vivo,

we used the murine Matrigel plug assay. At 1 week after

implantation, the Matrigel plug containing CdM-hAEC and CdM-hAMSC

formed a blood vessel network connected with the host vasculature.

These vessels contained blood. while there was no blood vessel in

the negative group (Fig. 5).

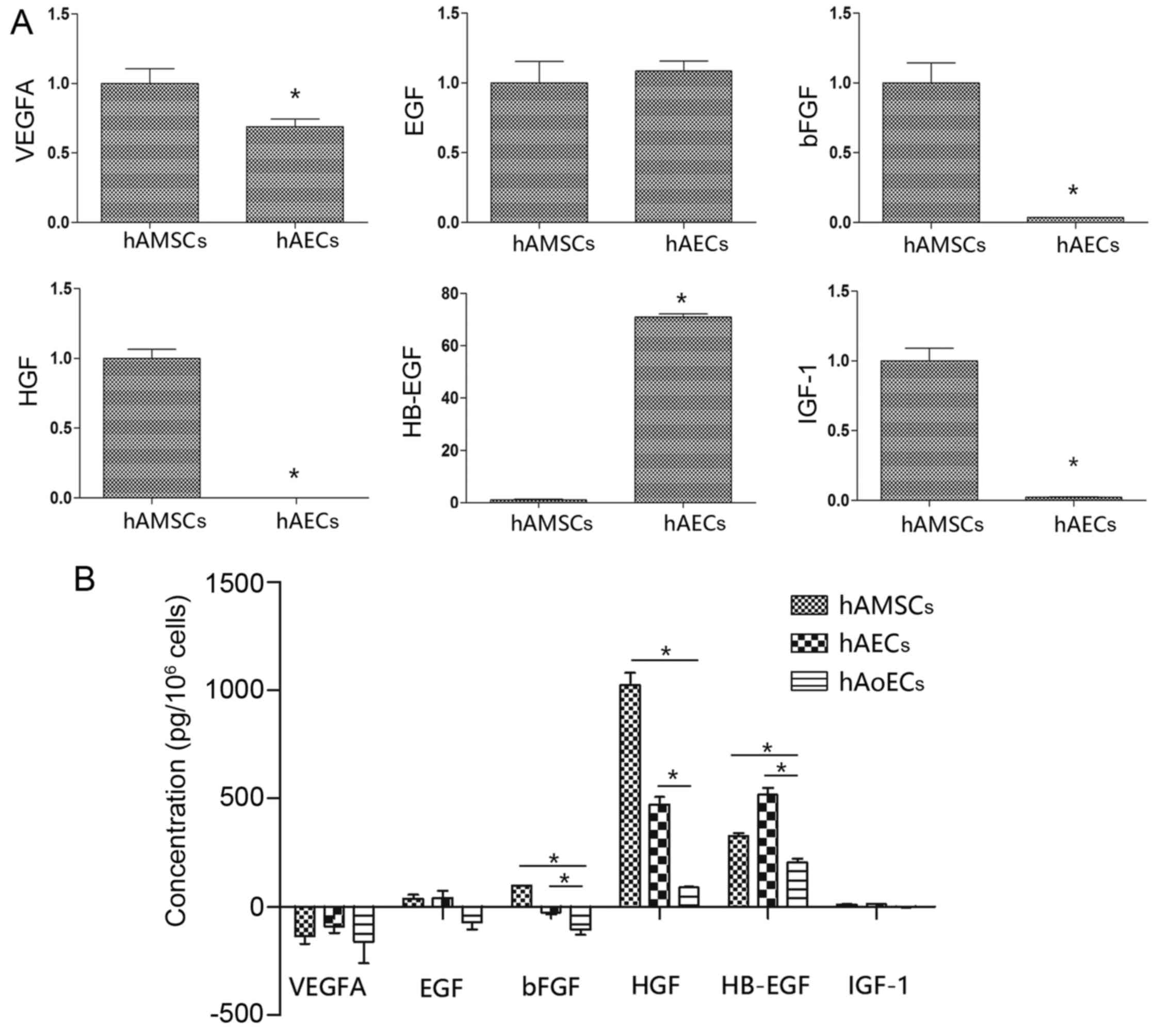

Expression of angiogenesis-specific mRNAs

in hAMSCs and hAECs

We used qRT-PCR to investigate the

angiogenic-related mRNA expression in the hAMSCs and hAECs. hAECs

showed significantly higher expression of the angiogenic gene

HB-EGF, which was 71-fold higher than the expression in the hAMSCs.

Notably, hAMSCs had a higher expression of bFGF, HGF and IGF-1

compared to these levels in the hAECs (>30-fold higher). In

addition, EGF and VEGFA, angiogenic factors that are pivotal in

neovascularization, were expressed to a similar extent in the hAECs

and hAMSCs (Fig. 6A).

Expression of angiogenic proteins in

CdMs

Collected CdMs were analyzed for the presence of

angiogenic proteins using an ELISA kit (Fig. 6B). The EGM-2 value was taken as a

background level. Compared with CdM collected from hAoECs (HB-EGF,

205.2±25.3 pg/106 cells; EGF, −72.9±43.26

pg/106 cells; bFGF, −106.4±33.3 pg/106 cells;

HGF, 89.9±2.8 pg/106 cells), amniotic cells secreted

higher levels of angiogenic factors. In line with the different

mRNA expression levels, compared with CdM-hAMSC (HB-EGF, 326.8±25.4

pg/106 cells; bFGF, 97.0±2.8 pg/106 cells;

HGF, 1024.5±98.3 pg/106 cells), CdM-hAEC had a higher

level of the proangiogenic factor HB-EGF (518.0±53.5

pg/106 cells), and lower levels of bFGF (−30.0±14.4

pg/106 cells) and HGF (472.1±49.8 pg/106

cells). There was no difference between hAECs and hAMSCs in regards

to VEGFA expression (−135.1±61 and −91.1±51.9 pg/106

cells, respectively) or EGF expression (38.3±29.7 and 41.5±57.9

pg/106 cells, respectively). Notably, although there was

an obvious difference in IGF-1 mRNA levels, there was no difference

in IGF-1 protein levels (10.5±3.8 and 12.8±2.1 pg/106

cells).

Discussion

Many studies have previously demonstrated the

therapeutic potential of stem cells using animal models including

wound healing (4,5), limb ischemia (2,3),

and myocardial infarction (6,7).

The proliferation, migration and angiogenic properties of

endothelial cells are important in the revascularization of

ischemic tissue and the reperfusion of myocardial infarction. While

recent studies have revealed the angiogenic properties of human

amniotic membrane and mesenchymal stem cells (16,21), information concerning hAECs is

rare, and comparative studies of the biological effects between

hAECs and hAMSCs are lacking. Therefore, in the present study, we

reported that amniotic cells possess high biological potential for

endothelial cells and we compared the differences in the cellular

function and biological properties between these cells. The main

findings of this study were: i) hAECs and hAMSCs display similar

growth kinetics, and express stem cell markers; ii) CdM-hAEC

significantly promoted endothelial cell migration, CdM-hAMSC

promoted endothelial cell proliferation, and they both promoted the

stabilization of angiogenesis; iii) there was high expression of

HB-EGF in hAECs; and iv) high expression of bFGF and HGF in hAMSCs.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare the beneficial

effects of hAECs and hAMSCs on endothelial cell function.

We are convinced that human amniotic cells are an

attractive source for cell therapy because they are free from

ethical concern, a large number of cells can be obtained, and they

display low immunogenicity, consistent with a previous study

(22). We can also obtain a large

number of cells from a small piece of amniotic membrane, thus

ensuring that there are abundant cells available for future

clinical therapy. hAECs and hAMSCs displayed similar growth

kinetics when cultured with EGM-2; and when we collected CdMs, the

number of hAECs and hAMSCs were found to be similar, thus making

the comparison of growth factors in CdMs more reasonable. After

xenogeneic transplantation into neonatal swine and rats, hAMSCs

engraft without immunosuppression (23–25). In accordance with these studies,

amniotic cells were negative for HLA-DR, which indicated that they

have low immunogenicity, which can be taken as an advantage for

in vivo therapy. OCT-3/4, SOX-2 and SSEA-4 are pluripotent

markers that are commonly expressed by stem cells (26). Consistent with previous studies

(19,26), hAMSCs and hAECs also

differentiated toward mesodermal lineages (osteogenic,

chondrogenic, and adipogenic), and expressed stem cell markers,

SSEA-4, SOX-2 and OCT-4, which indicates they have a high ability

of pluripotency and self-renewal.

In vivo studies demonstrated that there were

few differentiated cells being tested and the tissue concentrations

of growth factors were significantly increased in injured areas

treated with stem cells in transplanted models (10,27). We believe that the ability of

amniotic cells to stimulate regenerative effects is mainly induced

via paracrine routes. Furthermore, this theory is confirmed by

several studies, which showed that conditioned medium from MSCs

promoted the recovery of myocardial infarction (6,7,12).

Therefore, we collected CdM from amniotic cells, and tested the

biological effect of migration, proliferation and angiogenesis on

hAoECs. The collection time of 48 h was chosen based on the

literature (15). As an in

vitro assay of cell migration, we performed scratch and

Transwell experiments. CdM-hAEC markedly affected hAoEC migration

compared with CdM-hAMSC and CdM-hAoEC. These results are consistent

with in vivo research showing that hAECs promote

epithelialization and wound healing (4). CdM-hAMSC had a positive effect on

hAoECs, as shown by enhanced viability and proliferation ability in

the cell cycle distribution assay. CdMs from hAECs and hAMSCs

stabilized blood vessel network formation in vitro and

stimulated blood vessel formation in vivo. These results are

consistent with research showing that MSCs from bone marrow promote

angiogenesis and support blood vessel formation (3).

It has been shown that stem cells secrete a broad

variety of cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors, which may

potentially be involved in regenerative medicine (3,6,28).

The molecular processes leading to angiogenesis involve mediators

such as EGF, HB-EGF, VEGF, bFGF, HGF, IGF-1 and others, which lead

to cell migration, proliferation, vessel formation and maturation

(3,16–18,29–32). The present study demonstrates that

numerous arteriogenic cytokines are released by MSCs (11). This study demonstrated that hAECs

highly express HB-EGF; HAMSCs secreted significantly larger amounts

of HGF and bFGF, and gene results were confirmed using ELISA

assays. The difference in expression of IGF-1 mRNA was not

immediately obvious when tested by ELISA assay, perhaps due to

epigenetic regulation. We assume that these differences in the

cytokine expression profile could reflect the angiogenic and

cytoprotective properties of amniotic cells, as we observed

differences in their effects on hAoECs in our conditioned-medium

analysis.

In the present study, considering that amniotic

cells play a role in the microenvironment of endothelial cells, and

that EGM-2 functions in a similar manner, we chose EGM-2 for

conditioned medium collection to coordinate culture medium between

different cells. Cytokines not only have individual effects, but

one cytokine may potentiate (or inhibit) the effect of another,

i.e. having a synergistic or antagonistic relationship (33). Determining the nature and

mechanism(s) of the paracrine soluble molecules involved in

CdM-mediated angiogenesis stabilization is obviously a challenge

for all researchers in the field.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated the

differential effects of amniotic cells on the function of hAoECs,

via paracrine angiogenetic-related growth factors. Therefore, both

cell types may provide a convenient source for clinical

therapy.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the grants from the

National Basic Research Program of China (grant no. 2012CB518103),

the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no.

81450017), the Science and Technology Department of Liaoning

Province (grant no. 2013020200-206), the Science and Technology

Department of Liaoning Province (grant no. 2014305012), the Science

and Technology Bureau of Shenyang City (grant nos. F15-157-1-00),

the Science and Technology Planning Project of Shenyang (grant no.

F14-201-4-00).

References

|

1

|

Ilancheran S, Michalska A, Peh G, Wallace

EM, Pera M and Manuelpillai U: Stem cells derived from human fetal

membranes display multilineage differentiation potential. Biol

Reprod. 77:577–588. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kim SW, Zhang HZ, Kim CE, An HS, Kim JM

and Kim MH: Amniotic mesenchymal stem cells have robust angiogenic

properties and are effective in treating hindlimb ischaemia.

Cardiovasc Res. 93:525–534. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Lee CW,

Barr S, Fuchs S and Epstein SE: Marrow-derived stromal cells

express genes encoding a broad spectrum of arteriogenic cytokines

and promote in vitro and in vivo arteriogenesis through paracrine

mechanisms. Circ Res. 94:678–685. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Yoshida Y, Tanaka S, Umemori H, Minowa O,

Usui M, Ikematsu N, Hosoda E, Imamura T, Kuno J, Yamashita T, et

al: Negative regulation of BMP/Smad signaling by Tob in

osteoblasts. Cell. 103:1085–1097. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Liu X, Wang Z, Wang R, Zhao F, Shi P,

Jiang Y and Pang X: Direct comparison of the potency of human

mesenchymal stem cells derived from amnion tissue, bone marrow and

adipose tissue at inducing dermal fibroblast responses to cutaneous

wounds. Int J Mol Med. 31:407–415. 2013.

|

|

6

|

Fidelis-de-Oliveira P, Werneck-de-Castro

JPS, Pinho-Ribeiro V, Shalom BC, Nascimento-Silva JH, Costa e Souza

RH, Cruz IS, Rangel RR, Goldenberg RC and Campos-de-Carvalho AC:

Soluble factors from multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells have

antinecrotic effect on cardiomyocytes in vitro and improve cardiac

function in infarcted rat hearts. Cell Transplant. 21:1011–1021.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Timmers L, Lim SK, Hoefer IE, Arslan F,

Lai RC, van Oorschot AA, Goumans MJ, Strijder C, Sze SK, Choo A, et

al: Human mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improves cardiac

function following myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res (Amst).

6:206–214. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Balsam LB, Wagers AJ, Christensen JL,

Kofidis T, Weissman IL and Robbins RC: Haematopoietic stem cells

adopt mature haematopoietic fates in ischaemic myocardium. Nature.

428:668–673. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nygren JM, Jovinge S, Breitbach M, Säwén

P, Röll W, Hescheler J, Taneera J, Fleischmann BK and Jacobsen SE:

Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic cells generate cardiomyocytes at

a low frequency through cell fusion, but not transdifferentiation.

Nat Med. 10:494–501. 2004. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Shou M,

Lee CW, Barr S, Fuchs S and Epstein SE: Local delivery of

marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through

paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 109:1543–1549. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Konala VBR, Mamidi MK, Bhonde R, Das AK,

Pochampally R and Pal R: The current landscape of the mesenchymal

stromal cell secretome: A new paradigm for cell-free regeneration.

Cytotherapy. 18:13–24. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

12

|

Yamaguchi S, Shibata R, Yamamoto N,

Nishikawa M, Hibi H, Tanigawa T, Ueda M, Murohara T and Yamamoto A:

Dental pulp-derived stem cell conditioned medium reduces cardiac

injury following ischemia-reperfusion. Sci Rep. 5:162952015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

König J, Huppertz B, Desoye G, Parolini O,

Fröhlich JD, Weiss G, Dohr G, Sedlmayr P and Lang I: Amnion-derived

mesenchymal stromal cells show angiogenic properties but resist

differentiation into mature endothelial cells. Stem Cells Dev.

21:1309–1320. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sha X, Liu Z, Song L, Wang Z and Liang X:

Human amniotic epithelial cell niche enhances the functional

properties of human corneal endothelial cells via inhibiting P53

-survivin-mitochondria axis. Exp Eye Res. 116:36–46. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

König J, Weiss G, Rossi D, Wankhammer K,

Reinisch A, Kinzer M, Huppertz B, Pfeiffer D, Parolini O and Lang

I: Placental mesenchymal stromal cells derived from blood vessels

or avascular tissues: What is the better choice to support

endothelial cell function? Stem Cells Dev. 24:115–131. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

16

|

Yamahara K, Harada K, Ohshima M, Ishikane

S, Ohnishi S, Tsuda H, Otani K, Taguchi A, Soma T, Ogawa H, et al:

Comparison of angiogenic, cytoprotective, and immunosuppressive

properties of human amnion- and chorion-derived mesenchymal stem

cells. PLoS One. 9:e883192014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Yotsumoto F, Tokunaga E, Oki E, Maehara Y,

Yamada H, Nakajima K, Nam SO, Miyata K, Koyanagi M, Doi K, et al:

Molecular hierarchy of heparin-binding EGF-like growth

factor-regulated angiogenesis in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol

Cancer Res. 11:506–517. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kim SW, Zhang HZ, Guo L, Kim JM and Kim

MH: Amniotic mesenchymal stem cells enhance wound healing in

diabetic NOD/SCID mice through high angiogenic and engraftment

capabilities. PLoS One. 7:e411052012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Miki T, Lehmann T, Cai H, Stolz DB and

Strom SC: Stem cell characteristics of amniotic epithelial cells.

Stem Cells. 23:1549–1559. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Parolini O, Alviano F, Bagnara GP, Bilic

G, Bühring HJ, Evangelista M, Hennerbichler S, Liu B, Magatti M,

Mao N, et al: Concise review: Isolation and characterization of

cells from human term placenta: Outcome of the first international

Workshop on Placenta Derived Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 26:300–311.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Grzywocz Z, Pius-Sadowska E, Klos P,

Gryzik M, Wasilewska D, Aleksandrowicz B, Dworczynska M, Sabalinska

S, Hoser G, Machalinski B, et al: Growth factors and their

receptors derived from human amniotic cells in vitro. Folia

Histochem Cytobiol. 52:163–170. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Alviano F, Fossati V, Marchionni C,

Arpinati M, Bonsi L, Franchina M, Lanzoni G, Cantoni S, Cavallini

C, Bianchi F, et al: Term Amniotic membrane is a high throughput

source for multipotent Mesenchymal Stem Cells with the ability to

differentiate into endothelial cells in vitro. BMC Dev Biol.

7:112007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Manochantr S, U-pratya Y, Kheolamai P,

Rojphisan S, Chayosumrit M, Tantrawatpan C, Supokawej A and

Issaragrisil S: Immunosuppressive properties of mesenchymal stromal

cells derived from amnion, placenta, Wharton's jelly and umbilical

cord. Intern Med J. 43:430–439. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Magatti M, De Munari S, Vertua E, Gibelli

L, Wengler GS and Parolini O: Human amnion mesenchyme harbors cells

with allogeneic T-cell suppression and stimulation capabilities.

Stem Cells. 26:182–192. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Magatti M, De Munari S, Vertua E, Nassauto

C, Albertini A, Wengler GS and Parolini O: Amniotic mesenchymal

tissue cells inhibit dendritic cell differentiation of peripheral

blood and amnion resident monocytes. Cell Transplant. 18:899–914.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Fatimah SS, Tan GC, Chua K, Fariha MMN,

Tan AE and Hayati AR: Stemness and angiogenic gene expression

changes of serial-passage human amnion mesenchymal cells. Microvasc

Res. 86:21–29. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Gnecchi M, He H, Liang OD, Melo LG,

Morello F, Mu H, Noiseux N, Zhang L, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, et al:

Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart

by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 11:367–368. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Caplan AI and Dennis JE: Mesenchymal stem

cells as trophic mediators. J Cell Biochem. 98:1076–1084. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Yamakawa H, Muraoka N, Miyamoto K,

Sadahiro T, Isomi M, Haginiwa S, Kojima H, Umei T, Akiyama M,

Kuishi Y, et al: Fibroblast growth factors and vascular endothelial

growth factor promote cardiac reprogramming under defined

conditions. Stem Cell Reports. 5:1128–1142. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Chen QH, Liu AR, Qiu HB and Yang Y:

Interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial cells

restores endothelial permeability via paracrine hepatocyte growth

factor in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 6:442015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS,

Brem H and Tomic-Canic M: Growth factors and cytokines in wound

healing. Wound Repair Regen. 16:585–601. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chen L, Tredget EE, Wu PY and Wu Y:

Paracrine factors of mesenchymal stem cells recruit macrophages and

endothelial lineage cells and enhance wound healing. PLoS One.

3:e18862008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Yang Y, Chen QH, Liu AR, Xu XP, Han JB and

Qiu HB: Synergism of MSC-secreted HGF and VEGF in stabilising

endothelial barrier function upon lipopolysaccharide stimulation

via the Rac1 pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 6:2502015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|