Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most frequent cause of death

from gynecologic neoplasm in the Western World, mainly due to lack

of early detection and understanding of its etiology (1). Most ovarian malignancies have

epithelial origin and are often derived from ovarian surface

epithelial (OSE) cells (2). Thus,

understanding the molecular mechanisms that control OSE cell

proliferation and differentiation may lead to the design of novel

targeted therapies. Normal human OSE cells are capable of

steroidogenesis (3–5) and in epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC),

intratumoral steroid biosynthesis is closely linked with

carcinogenesis (2,5,6).

Several studies support a role for SF-1 as a

suppressor of ovarian cancer: i) ectopic expression of SF-1

inhibits rat ovarian epithelial cell proliferation, causing cell

cycle arrest and promoting apoptosis (7); ii) the tumor suppressor Rb1

synergizes with steroid receptor co-activator-2 (SRC-2) to enhance

the activity of SF-1 as well as nuclear receptors ERα and ERβ

(8); Rb1 may thus promote the

transcription of target genes linked to cell differentiation; iii)

SF-1 promotes differentiation of human and rat granulosa cells

associated with the developing oocytes (9).

It is well established that OSE cell proliferation

and ovarian steroidogenesis are closely linked (2,5,6).

Specifically, both cell culture and epidemiologic data support a

protective role for progesterone against ovarian cancer (10,11).

In addition to upregulating steroidogenic enzymes p450scc and

3β-HSD II, SF 1 stimulates expression of the human StAR gene

(12). The expression and

functional integrity of the StAR protein and enzymes p450scc and

3β-HSD II are particularly important for progesterone biosynthesis

(13).

We have previously shown that while human SF-1 and

StAR are expressed in normal OSE cells, ovarian cancer cell lines

SKOV-3, OVCar3 and BG1 do not show SF-1 or StAR expression

(14). We then utilized

immunohistochemistry to demonstrate that the vast majority of the

human ovarian tumor tissues examined do not express SF-1 protein

(unpublished data). In addition, real-time PCR studies on

epithelial ovarian cancers suggest that StAR mediated progesterone

biosynthesis may inhibit OSE tumor cell proliferation (15). Collectively these studies support

the hypothesis that loss of SF-1 protein may contribute to

carcinogenesis in ovarian epithelial cells, in part, through

decreased progesterone biosynthesis.

It is noteworthy that the human NR5A1 gene

has been mapped to chromosome 9 at position 9q33 (16), a region that shows genetic

alterations (LOH, microsatellite instability, and amplification) in

more than half of ovarian tumors (17). Particularly significant is the

observation that nearly all of the tumors that show genetic

alterations at 9q include the subchromosomal region 9q32–34,

suggesting that a candidate tumor suppressor gene may reside in

this region (17). The location of

human SF-1 in the region of 9q33 supports our hypothesis that SF-1

is a candidate tumor suppressor gene in the ovary and that

abolished or aberrant SF-1 expression in OSE cells may promote

tumor growth. We thus decided to examine the degree of LOH in

ovarian tumors, specifically at the NR5A1 locus and report LOH in

44% of the tumors.

Methylation controls the time and cell-type specific

NR5A1 gene expression in the endocrine system (18). Thus we examined the methylation

status of the NR5A1 gene promoter in ovarian tumors, and report

significantly higher prevalence of NR5A1 gene methylation in

ovarian tumors compared to normal (i.e. non-tumor) ovaries. These

data suggest that LOH and methylation may contribute to the loss of

SF-1 protein in ovarian tumors, which in turn may result in ovarian

carcinogenesis.

Materials and methods

Samples

Following approval of a research protocol by the

Institutional Review Board Committees of Tulane University and

Louisiana State University in New Orleans, 66 archival

formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks of ovarian

tissue were obtained from the Departments of Pathology at the

Tulane University Health Sciences Center and from the Interim LSU

Hospital. Sixteen samples were representative of normal ovaries

from women who had undergone gynecological surgeries for

non-ovarian related causes. The rest of the 50 samples consisted of

3 benign ovarian tumors, 7 tumors of low malignancy potential and

40 cases of ovarian carcinoma. Each case of ovarian tumor was

matched with corresponding benign tissue control. All FFPE tissue

blocks were sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for

histological assessment.

DNA extraction

FFPE tissue blocks

Tissue (1.5–2 mg) was excised from each normal and

tumor FFPE tissue block using a sterile scalpel and placed in an

autoclaved 1.5 ml centrifuge tube. Samples were deparafinized with

1 ml of xylene followed by vortexing at top speed for 2 min. The

tissue was then centrifuged at 10,000 x g for 3 min using

Microcentrifuge 16 from Beckman Coulter Inc. (Brea, CA, USA) and

the supernatant was pipetted out. To remove any residual xylene and

facilitate pelleting, 1 ml 100% ethanol was added to the tissue

sample, followed by spinning at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was

decanted and tissue pellets were allowed to air-dry at room

temperature. Subsequently, pellets were subjected to protease

digestion by 100 μl/ml proteinase K in Digestion Buffer [10

mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)]

at 52°C for 16 h. Following the digestion, DNA was isolated using

the Qiagen (Valencia, CA, USA) DNeasy for FFPE kit, following the

manufacturer’s recommended protocol.

Normal ovarian tissue samples

Ovarian surface epithelial cells from normal ovarian

FFPE tissue samples were dissected using the PALM® Robot

Microbeam laser microdissection system (PALM GmbH, Bernried,

Germany) at the Louisiana State University Morphology and Imaging

core facility. DNA was then extracted from the epithelial cells

using the proteinase K DNA extraction Solution and incubation at

65°C for 16 h, as suggested by the manufacturer

(Arcturus®, Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies

Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Genotyping

Both tumor and normal DNA samples were genotyped for

SNPs: rs2279605, rs10120967, rs7851737 using Applied Biosystems

TaqMan probes, with IQ power mix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) or

Amplitaq Gold, 25 mM MgCl2 and 10X PCR Gold buffer from

Applied Biosystems and dNTPs from VWR International (Radnor, PA,

USA). Applied Biosystems Taq Man probes are labeled with Fam and

Vic dyes. A total of 20 μl PCR reactions were set up in a

96-well plate which was covered with Microseal ‘B’ film from

Bio-Rad. Bio-Rad Thermal cycler IQ5 was used to run the real-time

PCR and Image Quant 5 software from Bio-Rad used for plate read

document and analysis of the real-time data post PCR. All

genotyping assays were done in triplicates and when the three

independent assays yielded ambiguous results, were repeated

again.

Digestion of genomic DNA for

methylation study

DNA (0.5 μg) from each sample (tumor and

normal from the same patient) was digested using 5 units of Afe1

enzyme (New England Bioscience, Ipswich, MA, USA) in a total

reaction volume of 50 μl. The digestion was performed in 1X

NEBuffer (New England Bioscience); 1X NE buffer contains: 20 mM

Tris-acetate, 50 mM potassium acetate, 10 mM magnesium acetate, 1

mM dithiothreitol (pH 7.9 at 25°C). The samples were incubated with

the enzyme for 1 h at 37°C to allow digestion of DNA, following

which Afe1 was inactivated by incubating the samples at 65°C for 20

min. Alternatively, digestion was performed overnight.

PCR amplification for methylation

study

All samples were simultaneously PCR-amplified for

the promoter region of the β-actin gene and NR5A1 gene in

200 μl tubes. For each 50 μl reaction, 2 μl of

DNA was used and reagent concentrations were optimized at: 5 mM for

MgCl2 from Applied Biosystems, 2 mM for each dNTP from

VWR; 5 mM for primers (β-actin, forward primer: 5′-TGC AAA GAA CAC

GGC TAA GTG TGC-3′, β-actin, reverse primer: 5′TCT AAG ACA GTG TTG

TGG GTG TAG GTs-3′, NR5A1 gene, forward primer: 5′-AAC ACC

AAC AAA GAA GGC GAG AGG-3′, NR5A1 gene, reverse primer:

5′-TCA CTT ACG AAG CGG AAG CAGC-3′) from IDT DNA (Coralville, IA,

USA) in 10X PCR buffer II [final concentration: 50 mM potassium

chloride and 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3 at room temperature) from

Applied Biosystems] along with 1.25 units AmpliTaq® DNA

polymerase per 50 μl of reaction. PCR amplification was

performed on a PTC-100™ programmable thermocycler from MJ Research

Inc. (Quebec, Canada) allowing initial denaturation at 95°C for 20

min followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 62°C for 1 min, 72°C

for 1 min and completing the terminal extension with 10 min at

72°C.

Gel electrophoresis

A total of 8 μl of PCR product was added to 2

μl of loading dye (2% xylene cyanol, 40% glycerol in DDi

H2O) from Boston Bioproducts (Ashland, MA, USA). For

sizing 1 kb plus DNA ladder (Invitrogen, Life Technologies

Corporation, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was loaded on a 2% agarose gel

containing 1X Tris-acetate-EDTA buffer (40 mM Tris acetate and 1 mM

EDTA) and 5 μg of ethidium bromide for staining. The gel was

run on a horizontal system for Gel electrophoresis from Bethesda

Research Laboratories Inc. (Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at 100 V for 60

min. Following the gel electrophoresis the amplified fragments were

visualized on Molecular Imager® Gel Doc™ using Image

Lab™ software from Bio-Rad.

Methylation analysis

Electrophoretic images were analyzed for relative

(NR5A1/β-actin) band intensity using Image Quant 5.1 software from

GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ, USA). Relative intensities were

categorized in quartiles as follows: −, 1st; + 2nd; ++ 3rd; +++ 4th

quartile. All experiments were done at least twice and the relative

intensities were averaged.

Clinical application

A retrospective chart review was performed gathering

clinical data on the patients for whom we had malignant ovarian

tissue. Characteristics examined were: age, race/ethnicity, date of

diagnosis, years survived since diagnosis, stage of ovarian cancer,

histologic grade, date of debulking surgery and treatment with

chemotherapy or radiation.

Statistics

For most statistical calculations, two-tailed

p-values were obtained using Fisher’s exact test. The log-rank test

was used for calculating p-values for potential differences in

survival.

Results

Samples

The clinical characteristics of the ovarian tumor

samples examined are shown on Table

I.

| Table I.Clinical characteristics of ovarian

tumors studied. |

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of ovarian

tumors studied.

| Age | Race | Date of Dx | Study no. | Years survived

since Dx | Stage | Histological

grade | Surgery | Chemo | Radiation |

|---|

| 53 | Black | 6/13/07 | T23 | Unknown | 3C | 3 | 6/13/07 | Yes | No |

| 62 | White | 6/19/07 | T24 | <1 year | 3C | 3 | 6/19/07 | No | No |

| 32 | White | 4/19/07 | T25 | <1 year | 4 | 3 | 8/23/07 | No | No |

| 54 | Black | 12/12/07 | T26 | Living | 0 | Borderline | 12/12/07 | No | No |

| 31 | White | 1/15/08 | T27 | Living | 0 | Borderline | 1/15/08 | No | No |

| 26 | Black | 2/18/08 | T28 | Living | 3B | 1 | 2/18/08 | No | No |

| 45 | Hispanic | 4/28/08 | T29 | Living | 0 | 2 | 4/29/08 | No | No |

| 64 | White | 5/8/08 | T30 | Living | 0 | Borderline | 5/18/08 | No | No |

| 60 | White | 8/13/08 | T31 | Living | 3C | 3 | 8/13/08 | Yes | No |

| 47 | Black | 10/8/08 | T32 | Living | 0 | Borderline | 10/8/08 | No | No |

| 55 | White | 10/9/08 | T33 | 1 year | 3C | 2 | 10/9/08 | No | No |

| 72 | Unknown | 10/27/08 | T34 | Living | 3C | 3 | 10/27/08 | Yes | No |

| 57 | White | 12/7/08 | T35 | <1 year | 3C | Borderline | 12/7/08 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 74 | Hispanic | 12/11/08 | T36 | Unknown | 3C | 3 | 12/11/08 | Yes | No |

| 50 | Black | 1/29/09 | T37 | <1 year | 4 | 2 | 1/29/09 | No | No |

| 49 | Black | 5/11/09 | T38 | Living | 0 | Borderline | 5/11/09 | No | No |

| 56 | Black | 9/28/09 | T39 | Living | 3A | 2 | 9/28/09 | Yes | Yes |

| 70 | Unknown | 10/1/09 | T40 | Living | 3C | 3 | 10/1/09 | Yes | No |

| 46 | Black | 3/2/07 | T21 | Unknown | 3C | 3 | 3/3/07 | Yes | No |

| 41 | Black | 6/12/07 | T22 | 1 year | 3C | 3 | 6/11/07 | Yes | No |

| 73 | White | 4/24/97 | T10 | 1 month | 3B | 3 | 11/24/97 | No | No |

| 41 | Black | 7/21/98 | T8 | 2 years | 4 | 3 | 7/21/98 | Yes | No |

| 69 | White | 4/5/99 | T13 | 6 years | 4 | 3 | 4/5/99 | Yes | No |

| 63 | Black | 3/5/00 | T9 | 2 years | 3C | 2 | 3/5/00 | Yes | No |

| 47 | White | 5/31/00 | T14 | Living | 3B | 3 | 5/31/00 | Yes | No |

| 26 | White | 5/21/99 | T15 | 3 years | 3C | 3 | 5/21/99 | Yes | Yes |

| 61 | Black | 3/5/02 | T49 | <1 year | 4B | 2 | 3/5/02 | Yes | No |

| 36 | White | 5/29/02 | T50 | Living | 0 | Borderline | 5/29/02 | No | No |

| 60 | White | 6/28/02 | T11 | Unknown | 3C | 2 | 6/28/02 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 83 | White | 8/9/02 | T51 | <1 year | 3C | 3 | 8/9/02 | No | Yes |

| 77 | Hispanic | 3/28/03 | T52 | <1 year | 4B | 3 | 6/13/03 | Yes | No |

| 67 | Black | 9/24/03 | T53 | 3 years | 3C | 3 | 9/26/03 | Yes | No |

| 43 | White | 6/18/01 | T54 | 2 years | NA | 3a colon

primary | 6/18/01 | Yes | No |

| 47 | White | 12/19/03 | T17 | Living | 3A | 3 | 12/19/03 | Yes | No |

| 68 | Black | 2/16/04 | T55 | <1 year | 4 | 3 | 2/16/04 | No | No |

| 75 | White | 6/20/03 | T1 | 2 years | 4 | 3 | 6/20/03 | Yes | No |

| 35 | Hispanic | 5/25/05 | T41 | <1 year | 3C | 2 | 5/25/05 | Yes | No |

| 76 | White | 7/20/06 | T42 | 2 years | 3C | 3 | 10/24/06 | Yes | No |

| 45 | White | 10/21/02 | T12 | 4 years | 2A | | 10/21/02 | No | No |

| 60 | NA | 2/10/02 | T4 | <1 year | 4 | 3 | 3/5/02 | Yes | No |

| 51 | White | 3/13/07 | T3 | Living | 3C | 3 | 3/13/07 | Yes | No |

| 70 | Indian | 3/16/07 | T2 | Unknown | 4 | 3 | 3/16/07 | Unknown | Unknown |

| 65 | White | 6/8/07 | T44 | <1 year | 4 | 3 | 6/12/07 | No | No |

| 68 | Black | 8/17/07 | T45 | Living | 4 | 3a

endometrial cancer | 8/17/07 | No | Yes |

| 64 | White | 6/23/08 | T56 | Living | 3C | 3 | 7/9/08 | Yes | No |

| 49 | White | 6/25/09 | T46 | Living | 2B | Unknown | 6/25/09 | No | No |

| 66 | Hispanic | 7/16/09 | T47 | Living | 3C | 3 | 7/16/09 | Yes | No |

| 51 | White | 8/8/09 | T48 | Living | 1A | 1 | 8/5/09 | No | No |

| 30 | White | 8/5/09 | T57 | Living | 1A | Borderline | 8/5/09 | No | No |

LOH at the NR5A1 locus in ovarian

tumors

In the current study, we considered two molecular

hypotheses of SF-1 protein loss in ovarian tumors: LOH and

increased methylation. To probe for the prevalence of LOH at the

NR5A1 locus, we genotyped matched ovarian tumor and normal

FFPE tissue DNA samples from the same ovarian cancer patient, for

three NR5A1 gene SNPs: rs2279605, rs10120967 and rs7851737.

SNPs were selected based on the following criteria: i) high

(>30%) frequency of heterozygosity in the racial/ethnic groups

present in our study population (based on available data at dbSNP:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/); ii)

availability of a preoptimized Taqman SNP Genotyping Assay for each

SNP. Genotyping was performed by Taqman SNP Genotyping Assays using

real-time PCR. Assays were performed in triplicates and repeated

again, if the genotyping results were ambiguous. All three

genotyped SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in normal samples

(data not shown).

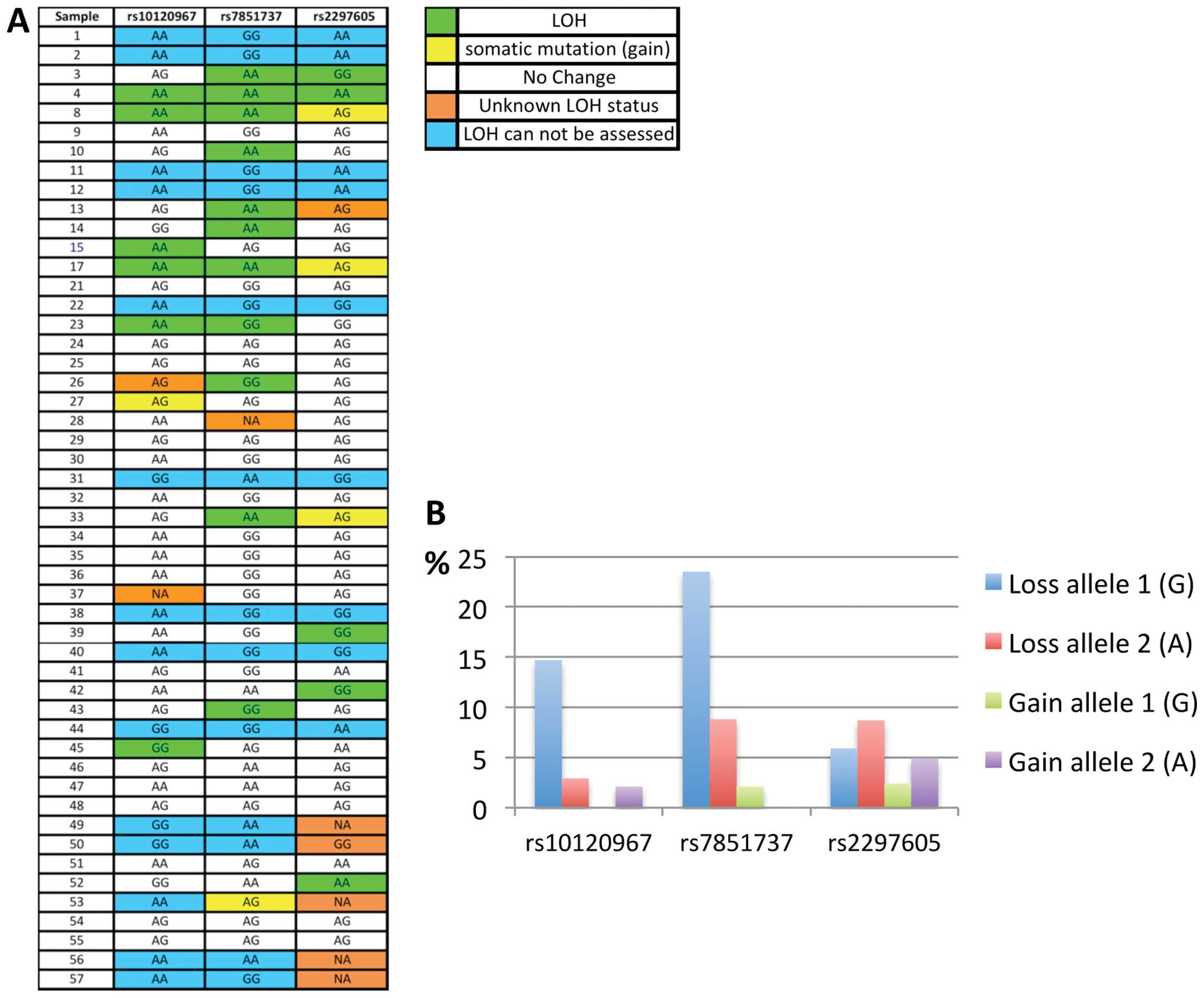

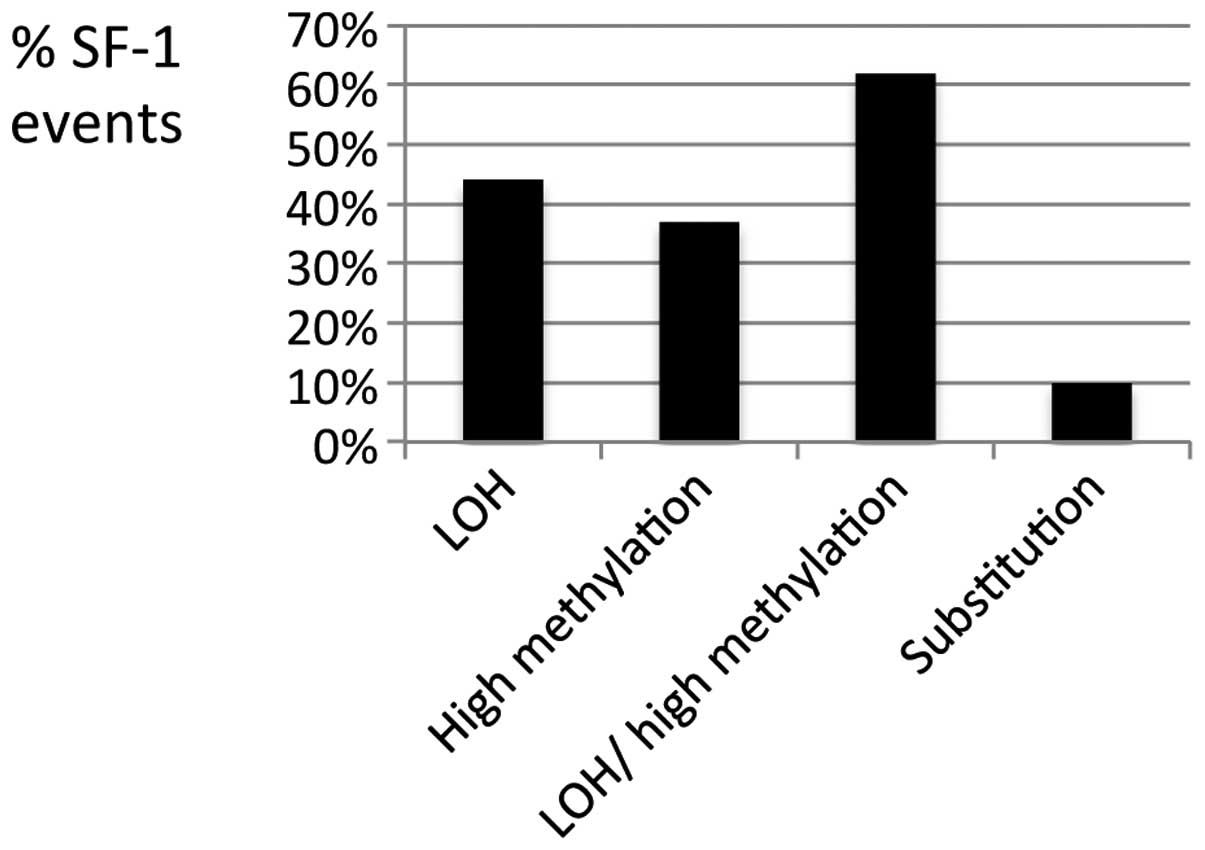

The genotyping results for the ovarian tumors and

the LOH data for each sample, are shown in Fig. 1A. These data show that out of the

36 ovarian tumor tissues that were heterozygous for at least one of

the three NR5A1 gene SNPs, 16 (44%) had LOH (Figs. 1A and 2). The majority of the ovarian tumors had

a single LOH event at the NR5A1 locus (out of maximum three

possible), but 5 tumors (14%) showed multiple LOH events (Fig. 1A). Also, each SNP showed LOH in

multiple tumors, with rs7851737 showing most losses (Fig. 1B). Thus, LOH occurs frequently at

the NR5A1 locus in ovarian tumors.

With regards to the type of observed loss, LOH

events at rs2297605 were equally distributed between the two

alleles, while the other two SNPs showed bias in the LOH events

towards one of the two alleles (Fig.

1B). The significance of this finding is unclear, since these

are non-coding SNPs. Interestingly, the genotyping results

(Fig. 1A) also uncovered somatic

mutations other than LOH in the tumors, manifested as allele gains;

base substitutions turning a homozygous genotype (normal DNA) into

a heterozygote genotype in the tumor, hence called ‘gain of

allele’; Fig. 1B. These somatic

NR5A1 substitutions were present in 10% of ovarian tumors

(Fig. 2). Thus the genotyping data

show frequent genetic (LOH/substitution) events at the NR5A1

locus in ovarian tumors.

Methylation of the NR5A1 gene in

ovarian tumors

A methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme (Afe1)

method (e.g. 19) was used to quantify site-specific methylation at

−30 bp (compared to translation start) of the NR5A1 gene

promoter in ovarian tumor tissue from patients with ovarian cancer

and in matched normal tissue from the same patients (when

available).

Afe1 cleaves genomic DNA at 5′-AGC/GCT-3′, but

cleavage is blocked by methylation (http://www.neb.com/nebecomm/products/productr0652.asp).

Since the Afe1 enzyme cleaves the un-methylated CpG’s, only

methylated CpG’s can be amplified and quantified following gel

electrophoresis. Complete DNA digestion was confirmed by prolonged

(overnight) Afe1 digestion, which yielded similar results (data not

shown). To control for differences in DNA level and/or quality

between tumor samples, we also amplified β-actin as an internal

control. The primers used for the β-actin gene were selected to

amplify a region that lacks an Afe1 cleavage site. Therefore,

β-actin is amplified regardless of methylation status, and relative

band intensity (NR5A1/β-actin) was used as a function of

NR5A1 gene methylation (see Materials and methods for

details). This analysis indicated that 36 out of 46 (78%) ovarian

tumors had appreciable NR5A1 methylation (2nd, 3rd and 4th

quartile of methylation levels), and 17/46 (37%) had high levels of

NR5A1 methylation (3rd and 4th quartile of methylation levels;

Table II). Thus the NR5A1

gene is methylated in most ovarian tumors. Furthermore, we detected

both a high level of NR5A1 gene methylation and LOH in 21%

of the ovarian tumors that we analyzed (Fig. 1 and Table II). The cumulative data also

demonstrate that 62% of the ovarian tumors have LOH, high level of

methylation, or both (Fig. 2) at

the NR5A1 locus.

| Table II.NR5A1 gene methylation in ovarian

tumors. |

Table II.

NR5A1 gene methylation in ovarian

tumors.

| Samples | Relative

intensity | Methylation

level |

|---|

| T1 | 0.24 | − |

| T2 | 0.81 | ++ |

| T3 | 1.14 | +++ |

| T4 | 0.78 | ++ |

| T8 | 0.35 | + |

| T9 | 0.72 | ++ |

| T10 | 0.02 | − |

| T11 | 0.34 | + |

| T12 | 0.40 | + |

| T13 | 0.77 | ++ |

| T14 | 0.48 | + |

| T15 | 0.54 | + |

| T17 | 0.40 | + |

| T21 | 0.45 | + |

| T22 | 0.62 | ++ |

| T23 | 0.58 | ++ |

| T24 | 0.56 | + |

| T25 | 0.68 | ++ |

| T26 | 0.37 | + |

| T27 | 0.87 | +++ |

| T28 | 0.55 | + |

| T29 | 0.78 | ++ |

| T30 | 0.83 | ++ |

| T31 | 0.58 | ++ |

| T32 | 0.09 | − |

| T33 | 0.57 | + |

| T34 | 0.32 | + |

| T35 | 0.17 | − |

| T36 | 0.53 | + |

| T37 | 0.43 | + |

| T38 | 0.54 | + |

| T39 | 0.57 | ++ |

| T40 | 0.42 | + |

| T41 | NA | NA |

| T42 | 0.75 | ++ |

| T43 | NA | NA |

| T44 | 0.14 | − |

| T45 | 0.00 | − |

| T46 | 1.14 | +++ |

| T47 | NA | NA |

| T48 | NA | NA |

| T49 | 0.10 | − |

| T50 | 0.11 | − |

| T51 | 0.79 | ++ |

| T52 | 0.53 | + |

| T53 | 1.07 | +++ |

| T54 | 0.00 | − |

| T55 | 0.00 | − |

| T56 | 0.54 | + |

| T57 | 0.30 | + |

As indicated by Table

I, most ovarian tumors are diagnosed at an advanced stage,

reducing the ability to obtain normal ovarian tissue from most

patients. In the absence of an adequate number of matched normal

ovaries available for study, 16 non-tumor ovaries were analyzed

(from unrelated individuals) to evaluate the relative methylation

of the promoter region of the NR5A1 gene in normal ovarian

tissue, with the same methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme

method used above. Since human ovarian tumors have epithelial

origin (2,20), we obtained OSE cells from these

ovarian tissues (by laser-capture microdissection) and analyzed

them following DNA extraction. β-actin was again amplified from

each sample as an internal control. These data show that only one

out of the 11 (9%) normal ovaries that were successfully evaluated

(i.e. that had β-actin amplification) showed appreciable

NR5A1 methylation (Table

III). This difference between the prevalence of NR5A1

methylation in tumor versus normal ovaries is statistically

significant (p<0.0001). Thus, ovarian tumor tissues display

significantly more frequent NR5A1 gene methylation than

normal ovarian epithelial tissues.

| Table III.NR5A1 gene methylation in normal

ovaries. |

Table III.

NR5A1 gene methylation in normal

ovaries.

| Samples | Relative

intensity | Methylation

level |

|---|

| N41 | 0 | − |

| N61 | 1.5 | +++ |

| N44 | 0.1 | − |

| N34 | NA | NA |

| N45 | 0.16 | − |

| N60 | 0 | − |

| N42 | 0 | − |

| N59 | 0 | − |

| N52 | 0 | − |

| N29 | NA | NA |

| N51 | 0 | − |

| N38 | 0 | − |

| N54 | NA | NA |

| N53 | 0.21 | − |

| N57 | NA | NA |

| N27 | NA | NA |

Clinical correlation

Retrospective analysis of the clinical data suggest

that presenting stage and histologic grade of ovarian tumors are

not significantly affected by the presence of somatic NR5A1

gene alterations (Table I and data

not shown). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were similar

for both ovarian tumors with and without NR5A1 gene

alteration (LOH/methylation; data not shown). Likewise, the

presence of NR5A1 gene alteration did not correlate with

race/ethnicity or treatment, such as radiation and chemotherapy

(Table I and data not shown).

Discussion

A common feature of many tumor suppressor genes is

their inactivation in cancer tissue through LOH and other somatic

mutations. In ovarian tumors, LOH and somatic mutations have been

documented for tumor suppressors such as TP53, BRCA1,

BRCA2 and PTEN(21).

The data presented herein support such a role for human SF-1, and

may provide a molecular mechanism to partially explain the loss of

SF-1 protein reported in both ovarian tumors and ovarian cancer

cell lines. Specifically, the data demonstrate that most ovarian

tumors contain genetic and/or epigenetic alterations at the

NR5A1 locus, significantly more frequently compared to

normal ovaries. These somatic alterations include LOH, base

substitution, and methylation of the NR5A1 gene promoter.

The absence of correlation between the presence of somatic

NR5A1 gene alteration and disease treatment

(radiation/chemotherapy) suggests that these somatic events are not

the result of cancer treatment. These data suggest the need for

scanning the NR5A1 gene for somatic mutations in larger

datasets, with diverse racial/ethnic groups, and perhaps in other

types of tumor tissues controlled by SF-1.

Given the prevalence of somatic events at the

NR5A1 locus, we attempted to examine the contribution of

these molecular events on clinical endpoints, such as disease

progression and survival. Interestingly, genetic and epigenetic

NR5A1 alterations do not correlate with markers of tumor

progression (grade/stage) or survival. This finding suggests that

somatic NR5A1 alterations may be early events in ovarian

carcinogenesis. Analysis of the early stage/grade tumors in our

dataset suggests a similar prevalence of somatic NR5A1

alterations in advanced and non-advanced tumors (data not shown).

However, this interpretation is tempered by the existence of low

numbers of non-advanced tumors in our dataset (Table I). Examination of larger numbers of

non-advanced and/or benign tumors for somatic NR5A1

alterations, may help confirming this concept.

The finding of somatic NR5A1 gene mutations

(gain of allele substitutions) in 10% of the ovarian tumors

(Fig. 2) is striking, given the

fact that we interrogated only three base pairs of the NR5A1

gene in these assays (the three SNP positions). This fact together

with the finding of LOH at this locus in 44% of the ovarian tumors

(Fig. 2), strongly suggest a high

somatic mutation frequency of the NR5A1 gene in ovarian

cancer. Thus, the NR5A1 gene should be screened for somatic

mutations by a more comprehensive method (such as sequencing) in

both advanced and benign ovarian tumors, especially tumors that

show LOH. This analysis should include the NR5A1 gene

promoter, since SF-1 protein expression is lost in both human

ovarian tumors and tumor cell lines. Identification of a somatic

mutation and/or methylation together with LOH in the same tumor,

may explain the loss of SF-1 protein reported in ovarian tumor

tissue. To that effect, the detection of both a high level of

NR5A1 gene methylation and LOH in 21% of the ovarian tumors

that we analyzed (Fig. 1 and

Table II), may partially explain

this loss.

LOH can be caused by two different mechanisms in

tumor cells: i) deletion (loss of allele/gene) or ii) base

substitution (which includes gene conversion). Although 14% of the

tumors had multiple LOH events (Fig.

1) suggesting a deletion at the NR5A1 locus, the

majority of LOH events involved only one (out of three possible)

SNPs at the NR5A1 locus (Fig.

1), suggesting no extensive NR5A1 deletion, at least

around the three interrogated SNPs. However, even a microdeletion

involving only the genomic area around a single NR5A1 SNP

can affect SF-1 protein expression. Also, gene conversion involves

recombination (22), which may

cause deletions, rearrangements and other functionally important

(for SF-1 expression) genetic events upstream or downstream from

the interrogated SNPs (undetected by our assay). Furthermore, both

molecular heterogeneity within the same tumor and contamination

with normal cells can result in underestimation of the extent of

LOH, or confinement of the observed LOH in a smaller genetic

region. In addition, the high somatic mutation frequency observed

at the NR5A1 locus may have functional effects. Therefore,

the frequently observed genetic (LOH/substitution) events at the

NR5A1 locus may significantly contribute to the reported

loss of SF-1 protein in ovarian tumor tissue.

A limitation of the methylation-sensitive

restriction enzyme method utilized here is that the use of PCR,

which exponentially amplifies the target DNA, makes the method less

quantitative. For this reason, we included β-actin as an internal

control, and also focused our methylation analysis on quartiles of

methylation rather than absolute levels. The significant difference

observed in the frequency of appreciable methylation (2nd quartile

or higher) between tumor and normal ovarian tissue (Tables II and III) suggests that NR5A1

methylation is much more prevalent in tumors. The exact degree of

methylation, and the subsequent reduction of SF-1 protein, is hard

to estimate from these data. However, the fact that the 37% of the

ovarian tumors that show high methylation (++ or higher methylation

level; Fig. 2) display >57% of

the band intensity of β-actin (Table

II), suggests that a significant proportion of the NR5A1 gene

is methylated in these ovarian tumors in vivo. Thus methylation may

be a major molecular mechanism leading to the reported loss of SF-1

protein in ovarian tumors.

Interestingly, hypomethylation and subsequent

transcriptional activation of SF-1 has been reported in

endometriosis, an estrogen dependent disease (23). In contrast, hypermethylation

leading to silencing of gene expression has been reported in

ovarian tumors for multiple key tumor suppressor genes including

BRCA1, BRCA2, WT1, APC, CDKN2A

and MLH1(24,25).

In conclusion, we report frequent somatic

alterations of the NR5A1 locus in ovarian tumors, including LOH,

base substitution, and methylation of the NR5A1 gene promoter.

These molecular abnormalities may partially explain the loss of

SF-1 protein, and contribute to the model of SF-1 as an ovarian

tumor suppressor. The existence of both genetic and epigenetic

NR5A1 gene abnormalities in ovarian tumors further suggest that

SF-1 is a common and important target in ovarian

carcinogenesis.

Abbreviations:

|

SF-1

|

steroidogenic factor-1

|

|

StAR

|

steroidogenic acute regulatory

protein

|

|

OSE

|

ovarian surface epithelial

|

|

ERα

|

estrogen receptor α

|

|

ERβ

|

estrogen receptor β

|

|

EOC

|

epithelial ovarian cancer

|

|

Rb1

|

retinoblastoma 1

|

|

SNP

|

single nucleotide polymorphism

|

Acknowledgements

NMM is supported by grants

P20GM103518, from the National Institutes of Health and PC094628,

from the Department of Defense.

References

|

1.

|

Ozols RF: Treatment goals in ovarian

cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 15(Suppl 1): 3–11. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Leung PC and Choi JH: Endocrine signaling

in ovarian surface epithelium and cancer. Hum Reprod Update.

13:143–162. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3.

|

Rae MT, Niven D, Ross A, Forster T, Lathe

R, Critchley HOD, Ghazal P and Hillier SG: Steroid signalling in

human ovarian surface epithelial cells: the response to

interleukin-1alpha determined by microarray analysis. J Endocrinol.

183:19–28. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Papacleovoulou G, Hogg K, Fegan KS,

Critchley HO, Hillier SG and Mason JI: Regulation of

3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 and type 2 gene

expression and function in the human ovarian surface epithelium by

cytokines. Mol Hum Reprod. 15:379–392. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Ivarsson K, Sundfeldt K, Brannstrom M and

Janson PO: Production of steroids by human ovarian surface

epithelial cells in culture: possible role of progesterone as

growth inhibitor. Gynecol Oncol. 82:116–121. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Okamura H, Katabuchi H and Ohba T: What we

have learned from isolated cells from human ovary? Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 202:37–45. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7.

|

Nash DM, Hess SA, White BA and Peluso JJ:

Steroidogenic factor-1 regulates the rate of proliferation of

normal and neoplastic rat ovarian surface epithelial cells in

vitro. Endocrinology. 139:4663–4671. 1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Batsche E, Desroches J, Bilodeau S,

Gauthier Y and Drouin J: Rb enhances p160/SRC coactivator-dependent

activity of nuclear receptors and hormone responsiveness. J Biol

Chem. 280:19746–19756. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Tran PV, Akana SF, Malkovska I, Dallman

MF, Parada LF and Ingraham HA: Diminished hypothalamic bdnf

expression and impaired VMH function are associated with reduced

SF-1 gene dosage. J Comp Neurol. 498:637–648. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Syed V, Ulinski G, Mok SC, Yiu GK and Ho

SM: Expression of gonadotropin receptor and growth responses to key

reproductive hormones in normal and malignant human ovarian surface

epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 61:6768–6776. 2001.

|

|

11.

|

Hinkula M, Pukkala E, Kyyrönen P and

Kauppila A: Incidence of ovarian cancer of grand multiparous women

- A population-based study in Finland. Gynecol Oncol. 103:207–211.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Sugawara T, Kiriakidou M, McAllister JM,

Holt JA, Arakane F and Strauss JF III: Regulation of expression of

the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) gene: a central

role for steroidogenic factor 1. Steroids. 62:5–9. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13.

|

Fujieda K, Tajima T, Nakae J, Sageshima S,

Tachibana K, Suwa S, Sugawara T and Strauss JF III: Spontaneous

puberty in 46,XX subjects with congenital lipoid adrenal

hyperplasia. Ovarian steroidogenesis is spared to some extent

despite inactivating mutations in the steroidogenic acute

regulatory protein (StAR) gene. J Clin Invest. 99:1265–1271. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14.

|

Ramayya MS, Sheng M, Moroz K, Hill SM and

Rowan BG: Human steroidogenic factor-1 (hSF-1) regulates

progesterone biosynthesis and growth of ovarian surface epithelial

cancer cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 119:14–25. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15.

|

Abd-Elaziz M, Moriya T, Akahira J, Suzuki

T and Sasano H: StAR and progesterone producing enzymes

(3beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and cholesterol side-chain

cleavage cytochromes P450) in human epithelial ovarian carcinoma:

immunohistochemical and real-time PCR studies. Cancer Sci.

96:232–239. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16.

|

Taketo M, Parker KL, Howard TA, Tsukiyama

T, Wong M, Niwa O, Morton CC, Miron PM and Seldin MF: Homologs of

Drosophila Fushi-Tarazu factor 1 map to mouse chromosome 2

and human chromosome 9q33. Genomics. 25:565–567. 1995.

|

|

17.

|

Schultz DC, Vanderveer L, Buetow KH,

Boente MP, Ozols RF, Hamilton TC and Godwin AK: Characterization of

chromo-some 9 in human ovarian neoplasia identifies frequent

genetic imbalance on 9q and rare alterations involving 9p,

including CDKN2. Cancer Res. 55:2150–2157. 1995.

|

|

18.

|

Hoivik EA, Aumo L, Aesoy R, Lillefosse H,

Lewis AE, Perrett RM, Stallings NR, Hanley NA and Bakke M:

Deoxyribonucleic acid methylation controls cell type-specific

expression of steroidogenic factor 1. Endocrinology. 149:5599–5609.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Nakamura J, Kitajima Y, Kai K, Hashiguchi

K, Hiraki M, Noshiro H and Miyazaki K: Expression of hypoxic marker

CA IX is regulated by site-specific DNA methylation and is

associated with the histology of gastric cancer. Am J Pathol.

178:515–524. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20.

|

Seidman JD, Russell P and Kurman RJ:

Surface epithelial tumors of the ovary. Blausten’s pathology of the

female genital tract. Kurman RJ: 5th ed. Springer; New York: pp.

791–904. 2002

|

|

21.

|

Despierre E, Lambrechts D, Neven P, Amant

F, Lambrechts S and Vergote I: The molecular genetic basis of

ovarian cancer and its roadmap towards a better treatment. Gynecol

Oncol. 117:358–365. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22.

|

Chen JM, Cooper DN, Chuzhanova N, Férec C

and Patrinos GP: Gene conversion: mechanisms, evolution and human

disease. Nat Rev Genet. 8:762–775. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23.

|

Xue Q, Lin Z, Yin P, Milad MP, Cheng YH,

Confino E, Reierstad S and Bulun SE: Transcriptional activation of

steroidogenic factor-1 by hypomethylation of the 5′ CpG island in

endometriosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 92:3261–3267.

2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24.

|

Balch C, Fang F, Matei DE, Huang TH and

Nephew KP: Minireview: epigenetic changes in ovarian cancer.

Endocrinology. 150:4003–4011. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25.

|

Barton CA, Hacker NF, Clark SJ and O’Brien

PM: DNA methylation changes in ovarian cancer: implications for

early diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Gynecol Oncol.

109:129–139. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|