Introduction

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth or fifth most common

cause of cancer-related death in most western industrialized

countries. The disease has a poor prognosis with a 5-year survival

rate of <5%. In unresectable cases, chemo- or radiotherapy is

used for palliation of symptoms and improvement of survival

(1,2). Gemcitabine is currently the standard

systemic treatment for unresectable and advanced pancreatic cancer,

which can extend patient survival by 5–6 months (3). To date, a more satisfactory outcome

has not been reported when gemcitabine is used in combination with

other cytotoxic drugs (3–5).

The molecular basis for the resistance of pancreatic

cancers to chemotherapy is not fully understood. It appears to

result from various mechanisms that can each influence tumor

resistance to gemcitabine. One form of drug resistance, termed

multidrug resistance (MDR), is linked to the expression of proteins

that act as drug efflux pumps. MDR is characterized by the

development of broad cross-resistance to functionally and

structurally unrelated drugs. This enhanced efflux of drugs is

mediated by a super family of membrane glycoproteins, the

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters. The ABCB superfamily

includes a 170-kDa transporter protein (ABCB1), also termed

P-glycoprotein (P-gp). P-gp is comprised of the protein product of

the human MDR1 gene in complex with the multidrug

resistance-associated protein (MRP) (6). The expression of P-gp correlates with

both the decreased accumulation of drugs, and the degree of

chemoresistance in many different human cancer cells (7–9).

Generally, 40–50% of patient tumors exhibit overexpression of P-gp

(10). Although gemcitabine is a

substrate for the ATP-dependent efflux pump (11), it is predominantly transported into

the cell via facilitated diffusion mediated by the equilibrative

nucleoside transporter (ENT), and sodium-dependent transporters

(concentrative nucleoside transporter, CNT) (12,13).

Pancreatic tumor cells can express high levels of ENT1, whereas

members of the CNT family are present at only negligible levels

(14).

Emerging evidence suggests that cancer stem cells

(CSCs), a small subset of undifferentiated cells found within

tumors, play a key role in tumorigenicity and malignancy (15). SP cells represent a small

subpopulation of tumor cells that have properties associated with

CSC in that they can rapidly efflux lipophilic fluorescent dyes

producing a characteristic profile in fluorescence-activated flow

cytometric analysis (16). SP

cells are generally defined by their ability to efflux the

fluorescent DNA binding dye Hoechst 33342 (H33342) and the

differential emission spectra of this dye when it binds chromatin

(16). The pumps responsible for

dye efflux are attributed to the ABC superfamily transporters,

including the MDR1/P-glycoprotein, ABCG2, MRP1 and ABCA2 (17–20).

These pumps also transport chemotoxic drugs out of the cell,

including vinblastine, doxorubicin, daunorubicin and paclitaxel

(21). SP cells exhibit increased

chemoresistance following in vitro exposure to gemcitabine

(22,23). The FACS-based assay used to detect

the presence of side populations is also currently under evaluation

as a general method to identify and isolate CSCs subpopulations

within tumor samples.

Verapamil is a calcium channel blocker that is

utilized clinically to treat cardiac arrhythmias (24). It is also a first generation

inhibitor of P-gp (25). When

combined with chemotherapeutic agents, verapamil can help to

promote intra-cellular drug accumulation (26). This has been demonstrated in

non-small cell lung cancer, colorectal carcinoma, leukemia, and

neuroblastoma cell lines (27–30).

Based on this ability of verapamil to inhibit P-gp transport

activity, it can also be used as an ‘SP’ blocker in the Hoechst

33342 assay as it will substantially reduce SP cells as visualized

by flow cytometry analysis. Based on these observations, we

hypothesized that verapamil treatment may directly exert anti-SP

effects and therefore enhanced gemcitabine sensitivity in

pancreatic cancer.

In this study, the biological characteristics of

CSCs in pancreatic cancer SP cells including their self-renewal

ability, resistance to gemcitabine, and general tumorigenicity were

investigated in the context of verapamil treatment.

Materials and methods

Human pancreatic cancer cells and culture

conditions

Human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell lines L3.6pl

(31) and AsPC-1 (American Tissue

Culture Collection) were maintained in Dulbecco's minimal essential

medium (D-MEM; Invitrogen GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany), supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (Biochrom AG, Berlin, Germany), 2% MEM

vitamin mixture (PAN Biotech GmbH, Aidenbach, Germany), 2% MEM NEAA

(PAN Biotech GmbH), 1% penicillin streptomycin (PAN Biotech GmbH,

Aidenbach, Germany) and 2% glutamax (Invitrogen GmbH). Cells were

incubated in a humidified incubator (37°C, 5% CO2),

grown in cell culture flasks, and passaged on reaching 70–80%

confluence.

A gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cell line,

termed L3.6plGres, was developed from the parental

L3.6pl cell line by gradually increasing the concentration of

gemcitabine (Gemzar; Lilly Deutschland GmbH, Giessen, Germany) in

the cultured cells. Gemcitabine was first added at a concentration

of 0.5 ng/ml (based on the IC50 value of L3.6pl). When

the cells reached exponential growth, they were subcultured for two

additional passages with 0.5 ng/ml gemcitabine or until the cells

grew stably. The concentration of gemcitabine was then increased to

100 ng/ml and the cells were passaged until a stable

gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cell line

(L3.6plGres) was established.

Isolation of SP- and non-SP-cell

fractions from L3.6plGres and AsPC-1 cell lines

SP- and non-SP-cell fractions were identified and

isolated using a modified protocol described by Goodell et

al (16). Briefly,

1×106/ml cells were re-suspended in D-MEM containing 2%

fetal bovine serum and labeled with H33342 (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH,

Steinheim, Germany) at a concentration of 2.5 μg/ml for 60 min in

37°C water bath, either alone or with 225 μM verapamil

hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH). After 60 min the cells were

centrifuged (300 g, 4°C) for 5 min, and then resuspended in

ice-cold PBS containing 2% fetal bovine serum. The cells were

passed through a 40-μm mesh filter and maintained at 4°C in the

dark until flow cytometry analysis or sorting. Cells were

counter-stained with 10 μg/ml propidium iodide to label dead cells,

and the entire preparation was then analyzed using a BD-LSRII flow

cytometer (BD Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and FlowJo software

(Treestar Inc., Ashland, OR, USA), or sorted using a MoFlo cell

sorter with the Summit 4.3 software (Beckmann Coulter GmbH,

Krefeld, Germany). Hoechst dye was excited at 355 nm (32), and fluorescence was measured at two

wavelengths using a 450/50-nm (blue) band-pass filter and a

670/30-nm (33) long-pass edge

filter. Following isolation the SP and non-SP cell fractions were

used for in vitro and in vivo assays.

Cell viability and proliferation

assay

Trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) staining was used to

test for cell viability. The dye stains dead cells, and livings are

distinguished by their ability to exclude the dye performing phase

contrast microscopy. Cell viability was calculated using the

following formula: Cell viability = unstained cells/unstained +

trypan blue stained cells × 100%. Cell proliferation was measured

using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto,

Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In this assay

5,000–8,000 cells/well were plated in a 96-well plate and grown

overnight, and then treated for 24 h with gemcitabine or verapamil.

Cell proliferation was then determined using a VersaMax tunable

microplate reader and Softmaxpro 5.2 software for data analysis

(Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

Apoptosis assay

Cell apoptosis was analyzed using an Annexin V-FITC

assay (Miltenyi Biotec GmbH, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) according

to the manufacturer's instructions. After determination of cell

numbers, 1×106 cells were washed with binding buffer and

centrifuged. The cell pellet was resuspended in binding buffer, and

10 μl of Annexin V-FITC per 106 cells was added, mixed,

and the preparation was incubated for 15 min in the dark at room

temperature. The cells were then washed, and the cell pellet

resuspended in binding buffer. The PI solution was added

immediately prior to analysis using a BD-LSRII flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences, Heidelberg, Germany) and FlowJo software version 7.6

(Treestar Inc.). Experiments were repeated at least three

times.

Colony formation assay

To determine the ability of cells to form colonies,

500 cells in 2 ml of D-MEM medium were seeded into each well of a

6-well plate. The medium was changed two times per week and the

assay was stopped when colonies were clearly visible without using

a microscope (i.e., each single colony comprised approximately ≥50

cells). The resulting colonies were stained with 0.1% crystal

violet and counted.

Flow cytometry analysis

For this staining procedure, the cells were

incubated in the dark and on ice. Firstly they were blocked with

PBS containing 0.5% albumin bovine (BSA) and 0.02% NaN3

with FCR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec) for 15 min. Cells were

then stained with the P-glycoprotein mouse mAb primary antibody

(clone C219, Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) for 45 min on ice.

Afterwards they were incubated with the fluorescence-conjugated

secondary antibody, goat anti-mouse IgG FITC (Abcam, Cambridge, UK)

for 45 min. FITC isotype mouse immunoglobulins were used as

negative controls. FITC was excited using a 488-nm laser and

detected by a 530/30 band-pass filters. Dead cells were excluded by

gating on forward and side scatter and eliminating PI-positive

population cells. All the data were analyzed using FlowJo software

version 7.6 (Treestar Inc.).

Western blot assay

The proteins ENT1 and P-gp were assayed by

immunoblotting. Cells were resuspended in ice-cold RIPA buffer

supplemented with a cocktail of protease/phosphatase inhibitors

(Roche, Mannheim, Germany). Cells were further incubated on ice for

10 min and centrifuged at 14,000 g at 4°C for 10 min. After

determination of the protein concentration using the BCA protein

assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), an equal

amount of protein was run on polyacrylamide gels and transferred

semidry to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham,

Braunschweig, Germany). The corresponding primary antibody was

incubated at 4°C overnight. After blocking for 2 h, the secondary

antibody was added and incubated for 2 h at room temperature,

following by washing. An enhanced chemiluminescense

system(Amersham) was used for detection. Afterwards the membranes

were reused for β-actin staining (Sigma-Aldrich GmbH) to ensure

equal protein levels. The polyclonal goat anti-mouse/rabbit

immunoglobulin HRP (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) was used according to

the manufacturer's instructions. For detection of the ENT1 protein,

the anti-ENT1 antibody (Abcam) was used at 1:500 in 5% BSA-TBST

buffer. For P-gp protein detection, the monoclonal mouse C219

antibody (Calbiochem) was used at 1:100 dilutions in 7.5% skim

dried milk-PBST buffer. This antibody recognizes the two P-gp

isoforms (34).

Orthotopic pancreatic cancer mouse

model

Approval by the animal rights commission of the

state of Bavaria, Germany was obtained for all animal experiments.

Male athymic Balb/c nu/nu mice were purchased from Charles River,

Inc. (Sulzfeld, Germany). Mice aged 6–8 weeks with an average

weight of 20 g were maintained under a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and

were used for the orthotopic pancreatic cancer mouse model. They

were anesthetized using ketamine [100 mg/kg body weight (BW),

xylazine (5 mg/kg BW] and atropine. The operation was carried out

in a sterile manner. A 1-cm left abdominal flank incision was made,

the spleen was exteriorized and 1×105 isolated SP- and

non-SP L3.6plGres cells were injected into the

subcapsular region of the pancreas. Before injection, cell

viability was assessed by trypan blue staining and only cell

preparations that showed ≥95% viability were used for injection.

Mice were divided into an SP control group, non-SP control group

and different drug treatment SP-groups. Four weeks after orthotopic

implantation, therapy was initiated. One treatment group obtained

daily (every workday) intraperitoneal injection of low

concentration of verapamil (200 μM, 0.5 mg/Kg BW), the second

treatment group received a higher concentration of verapamil (10

mM, 25 mg/Kg BW). Nine weeks after the injection of tumor cells,

all the mice were sacrificed and examined for orthotopic tumor

growth and development of metastases. The pancreatic tumors as well

as other organs were isolated, weighed, and then used for H&E

and immunohistochemical staining.

Immunohistochemistry

Formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissues

were serially sectioned at 3 μm and allowed to dry overnight.

Sections were deparaffinized in xylene followed by a graded series

of ethanol (100, 95 and 80%) and rehydrated in phosphate-buffered

solution, pH 7.5. Paraffin-embedded tissues were used for the

Ki67 proliferation index assay, microvascular density

analysis, and the TUNEL assay. TUNEL assay was carried out using an

in situ cell death detection kit, Fluorescein (Roche

Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), according to the

manufacturer's instructions. The antibodies used for

paraffin-embedded tissues were monoclonal rabbit anti-Ki67

antibody (ab 16667, Abcam) and polyclonal rabbit anti-CD31 (ab

28364, Abcam). The primary antibodies were diluted in PBS

containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA). The sample slides were

treated for 20 min with blocking solution (8% goat serum or rabbit

serum in PBS with 3% BSA) before the primary antibody was applied.

Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation with 3% hydrogen

peroxide (H2O2). Endogenous avidin and biotin

were blocked using the Avidin/Biotin Blocking kit (Vector,

USA).

Overnight incubation with the primary antibodies was

followed by incubation with the respective biotinylated secondary

antibodies (goat anti-rabbit, BA-1000, Vector), followed by the ABC

reagent for signal amplification (Vectastain ABC-Peroxidase kits,

PK-4000, Vector). Between the incubation steps, the slides were

washed in TBS. 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Dako, USA) was used to

develop the color. Slides were counter-stained with hematoxylin,

mounted in Kaisers Glycerinegelatine (Merck, Germany), and

covered.

For quantification of the staining intensity, each

index (Ki67, microvascular density CD31, and TUNEL) was

evaluated in a blinded manner. Slides were observed under a

high/low magnification scope (×200/×100), each one was evaluated

within 3 fields, and the data were analyzed as mean positive signal

(Ki67-positive cells, amount of microvessels, cells with

strong FITC-fluorescence) of 3 fields.

Statistical analysis

Statistical evaluation was performed using the

paired Student's t-test or ANOVA test (Microcal Origin) with

p<0.05 considered to be statistically significant [p<0.05

(&); p<0.01 (#) p<0.001

(*); p<0.0001 (**)]. GraphPad

Prism® 5.0 or Microsoft excel 2010 software were used to

generate graphs and tables.

Results

Side population cells are enriched in

L3.6plGres cells and show higher colony formation

The human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line L3.6pl

was continuously cultured with gemcitabine, starting at 0.5 ng/ml,

which was then gradually increased to 100 ng/ml over multiple cell

passages to eventually develop a gemcitabine-resistant version of

the cell line (L3.6plGres). The 24 h IC50

increased from 6.1±0.9 ng/ml in the parental L3.6pl cells, to

498.8±3.2 ng/ml in the L3.6plGres cells (L3.6pl vs.

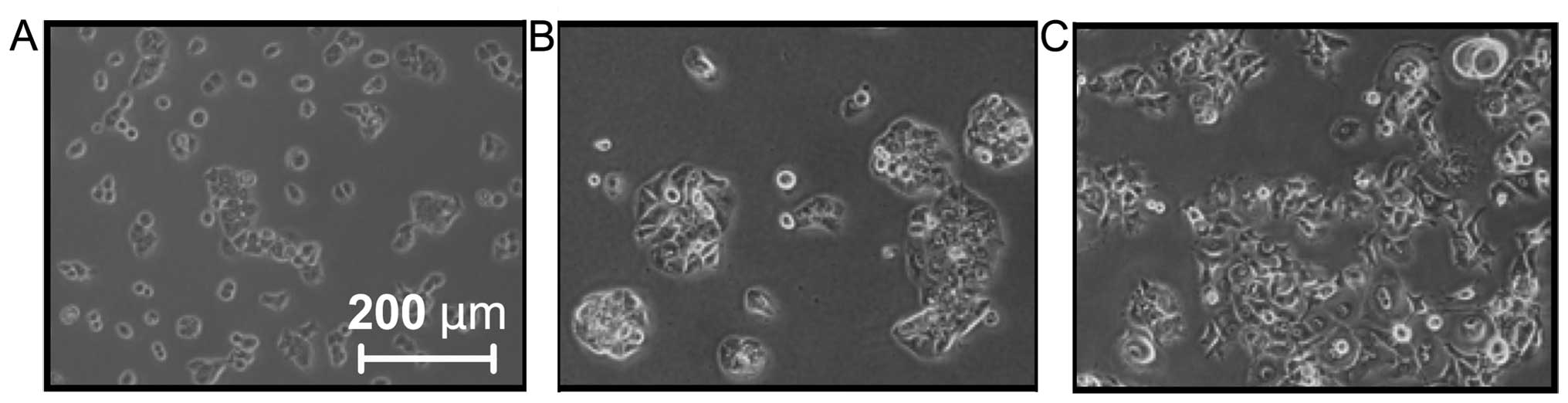

L3.6plGres p<1E−9). The general morphology

of L3.6plGres cells was also changed with gemcitabine

resistance into large fibroblastoid-like tumor cells (Fig. 1), while the parental L3.6pl cell

line maintained its original round shape. By contrast, the AsPC-1

line, which was largely resistant to gemcitabine and presented with

a spindle-like shape, did not show a change in morphology under

gemcitabine selection (data not shown).

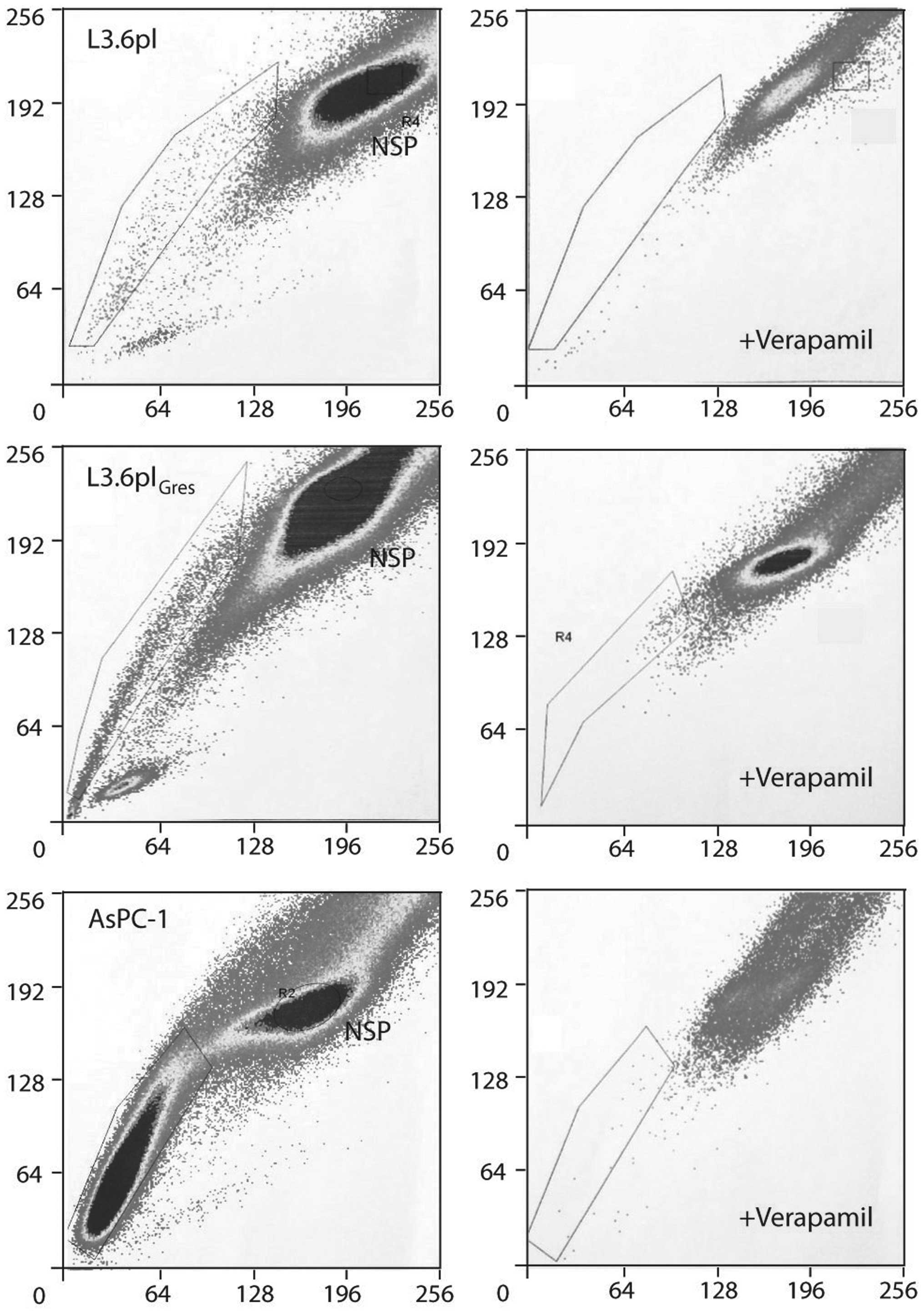

The L3.6pl and AsPC-1 cell lines were assayed for

the presence of SP-cells. Verapamil hydrochloride, which blocks

transporters of the ABC family and abrogates the ability of cells

to efflux the dye, served as an SP cell control in the H33342 assay

(SP cells will disappear or decrease in the presence of ABCG2

inhibitors owing to inhibition of Hoechst efflux from the cells).

Both cell lines were found to contain a distinct proportion of SP

cells. The percentage of SP cells increased from 0.9±0.22% in

L3.6pl, to 5.38±0.99% in the L3.6plGres cells in

response to continuous gemcitabine treatment. This proportion of SP

cells could be diminished by treatment with verapamil

hydrochloride. In the AsPC-1 cell line, 21.35±3.48% SP cells were

identified, which was found to diminish to 3.56±0.87% in response

to verapamil blockade (p<5E−10) (Fig. 2).

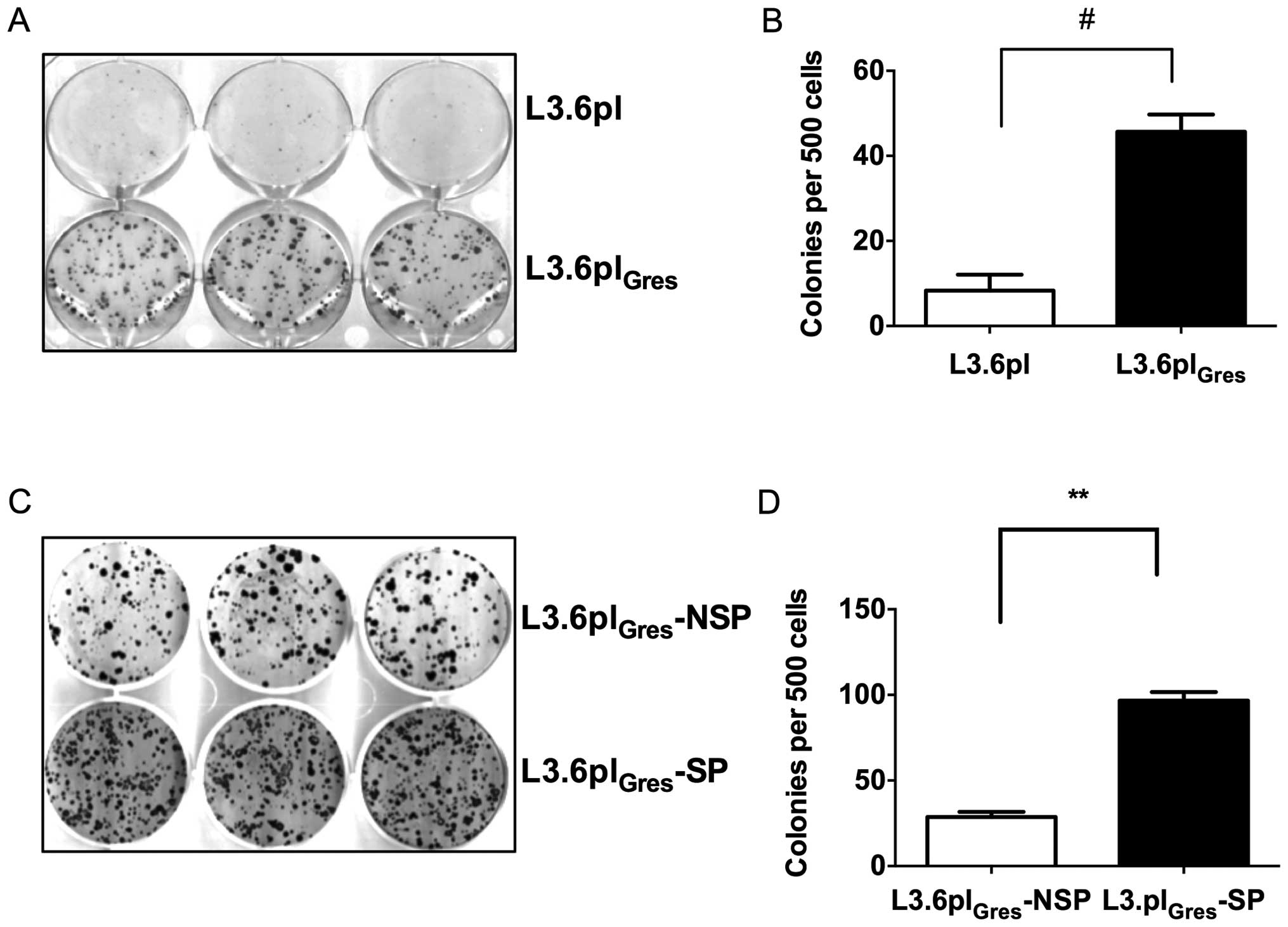

We then compared the colony formation ability of

L3.6plGres, L3.6pl, as well as L3.6plGres-SP

and NSP cells. The assay showed that L3.6plGres cells

and L3.6plGres-SP cells have significantly higher colony

formation ability, and thus enhanced CSC-like characteristics when

compared to the L3.6pl or L3.6plGres-NSP cells (Fig. 3).

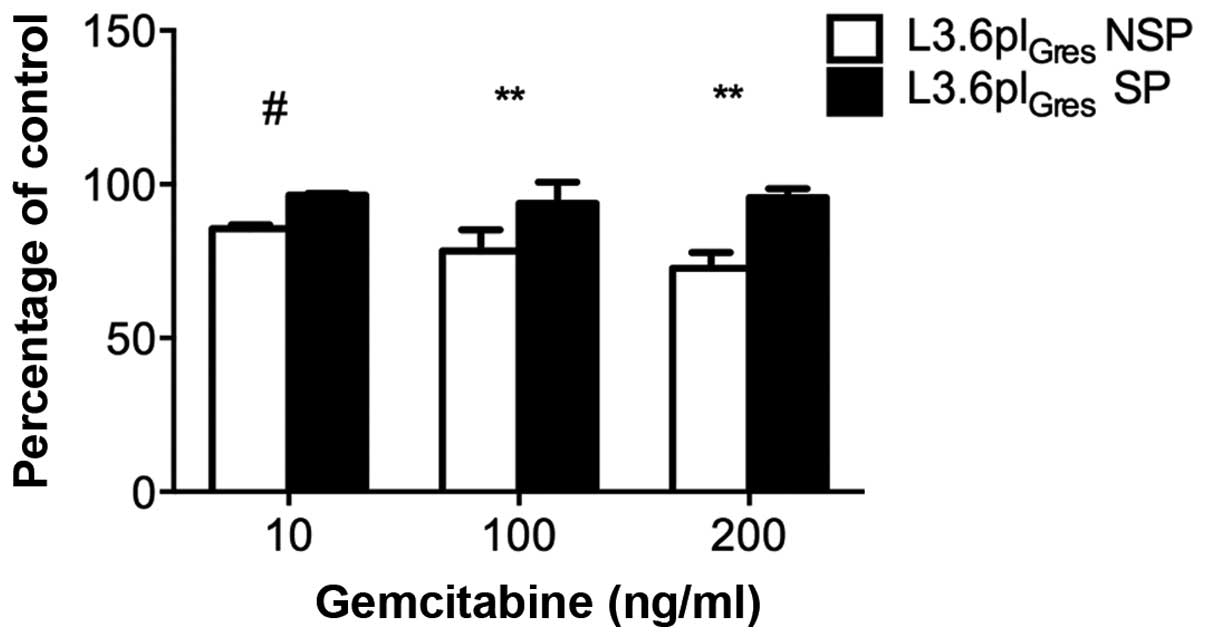

The gemcitabine resistance of L3.6plGres

cells was further validated by cell viability assays. The results

show that L3.6plGres-SP cells have enhanced resistance

to gemcitabine relative to respective NSP cells (Fig. 4).

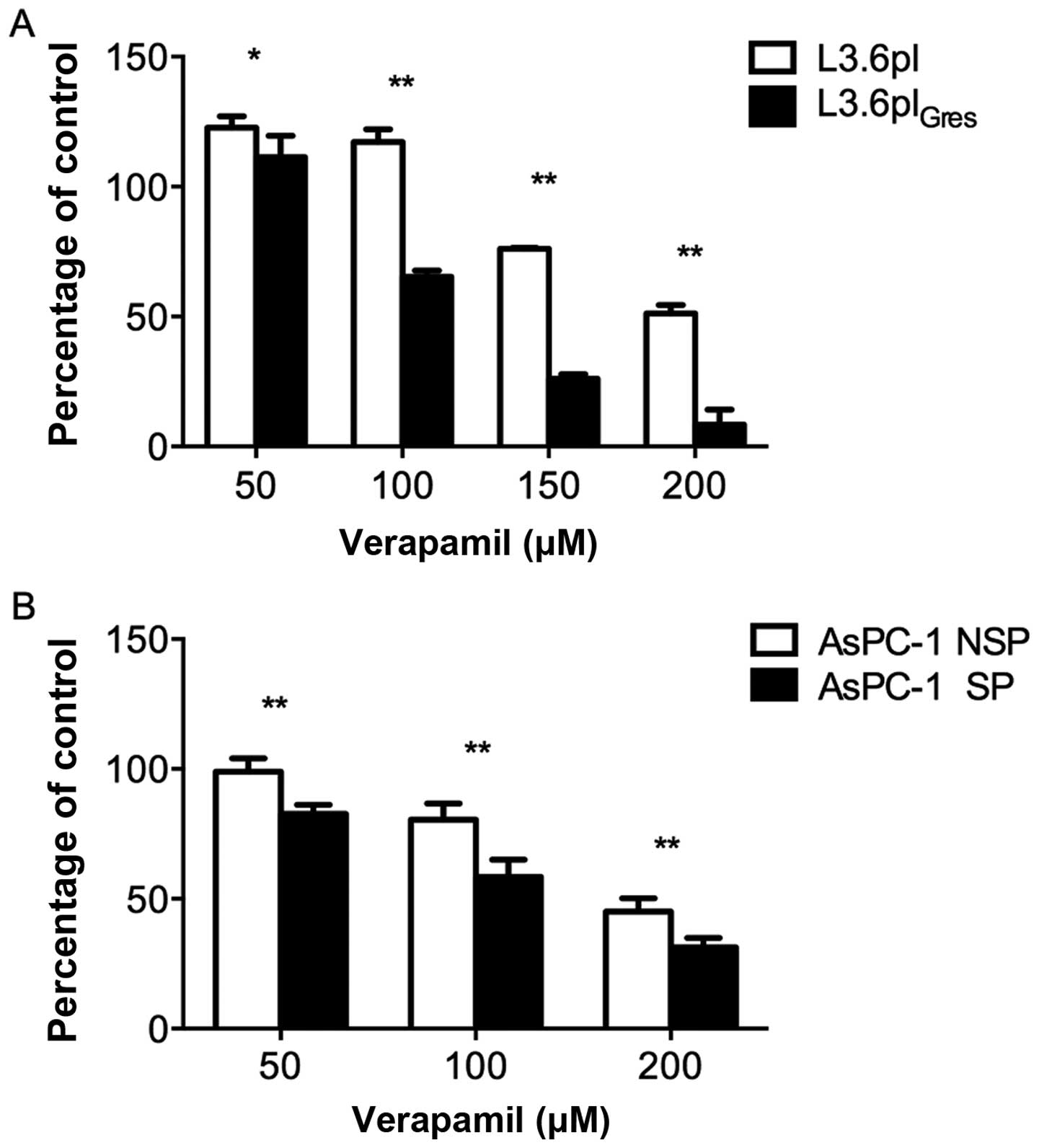

Verapamil can effectively inhibit

L3.6plGres and AsPC-1 SP cell proliferation

Since the percentage of SP cells in the parental

L3.6pl cell line was relatively low, it was difficult to harvest

sufficient cell numbers by FACS sorting for cell proliferation

assays. Therefore, the proliferation capacity of the

L3.6plGres cell line (enriched SP cells) was compared to

control L3.6pl cells. In parallel, the SP and Non-SP cells from the

AsPC-1 cell line were directly compared.

To investigate whether verapamil alone is effective

against SP cells, we analyzed its effect on L3.6pl- and

L3.6plGres-, AsPC-1-SP and -NSP cell proliferation. All

of the cell lines tested showed a concentration-dependent reduction

in cell proliferation. In response to 50, 100, 150 and 200 μM of

verapamil, the L3.6plGres- and AsPC-1-SP cells were more

sensitive to verapamil effects than L3.6pl- and AsPC-1-NSP cells

(Fig. 5).

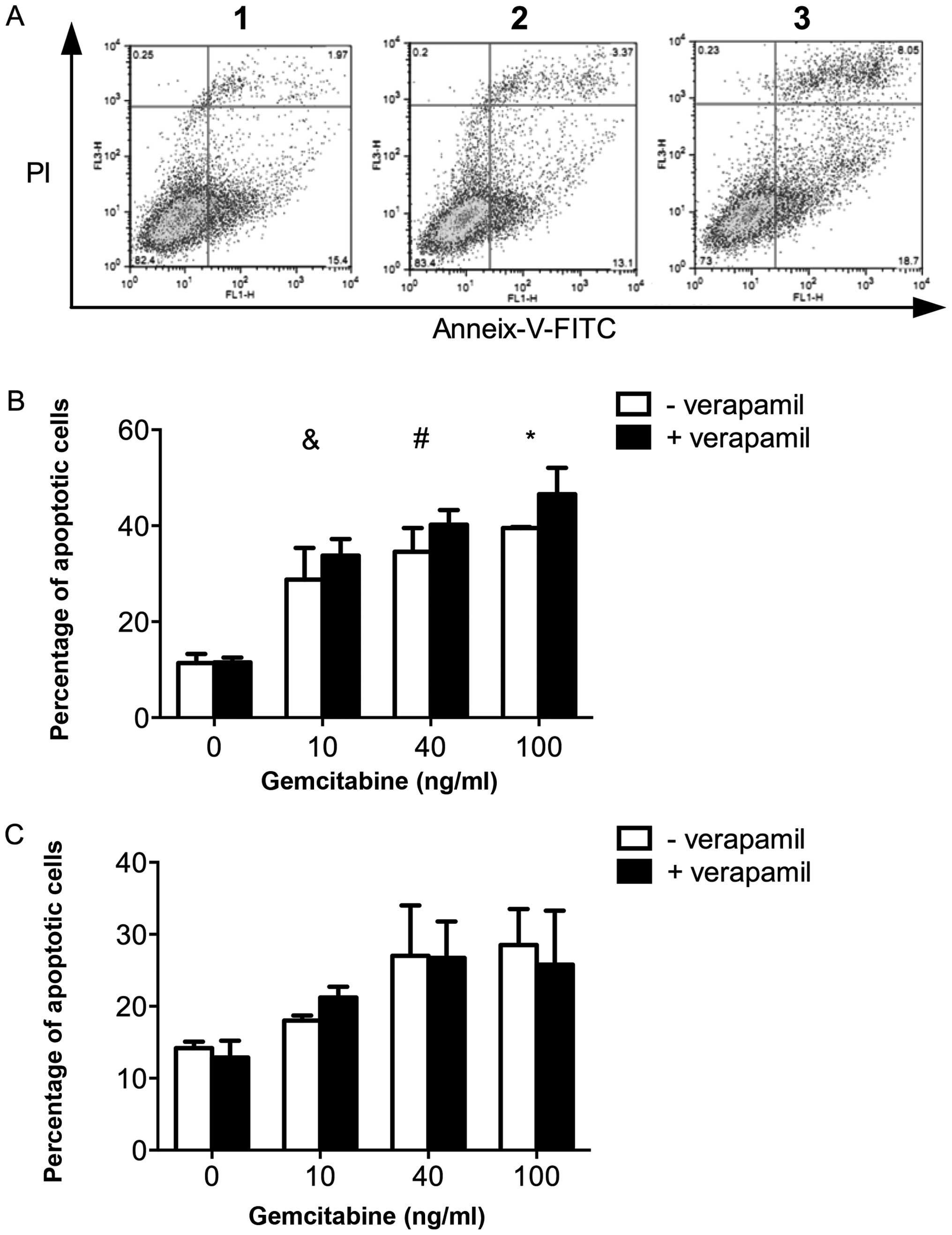

Pro-apoptotic effect of verapamil in

combination with gemcitabine in L3.6pl and L3.6plGres

cells

The potential additive effect of verapamil in

combination with gemcitabine was then investigated.

L3.6plGres-SP cells were treated separately with

verapamil (50 μM), gemcitabine (10 ng/ml), and in combination.

Using FACS analysis, the level of apoptotic cells after combined

treatment (at 24 h) was found to increase relative to treatment

with verapamil or gemcitabine alone (Fig. 6A). In dose response experiments,

the apoptosis of L3.6pl and L3.6plGres cells in response

to increasing concentrations of gemcitabine was determined, while

maintaining the concentration of verapamil at 50 μM. A

dose-dependent increase in apoptosis was observed in L3.6pl cells,

but not in the L3.6plGres cells (Fig. 6B and C).

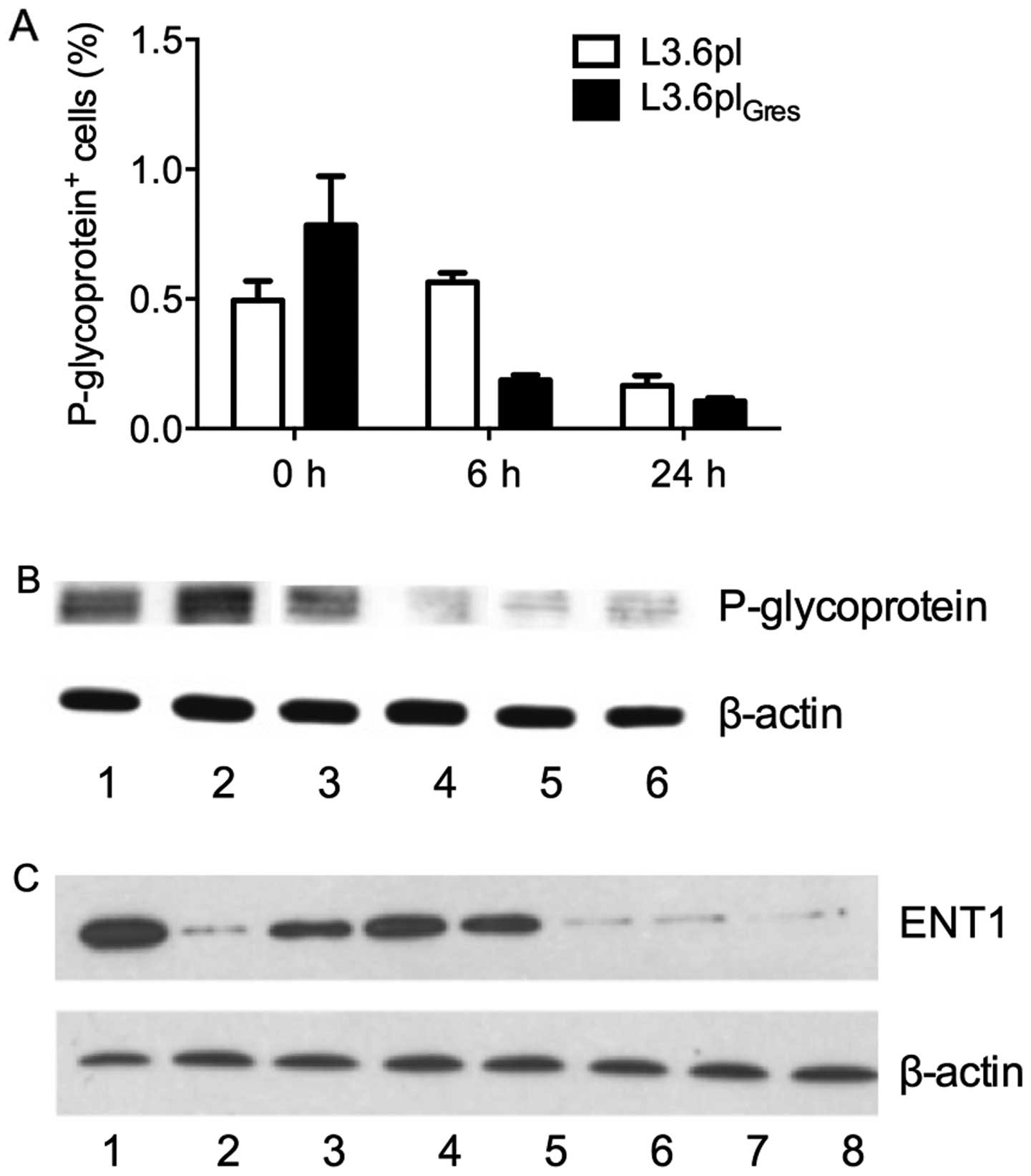

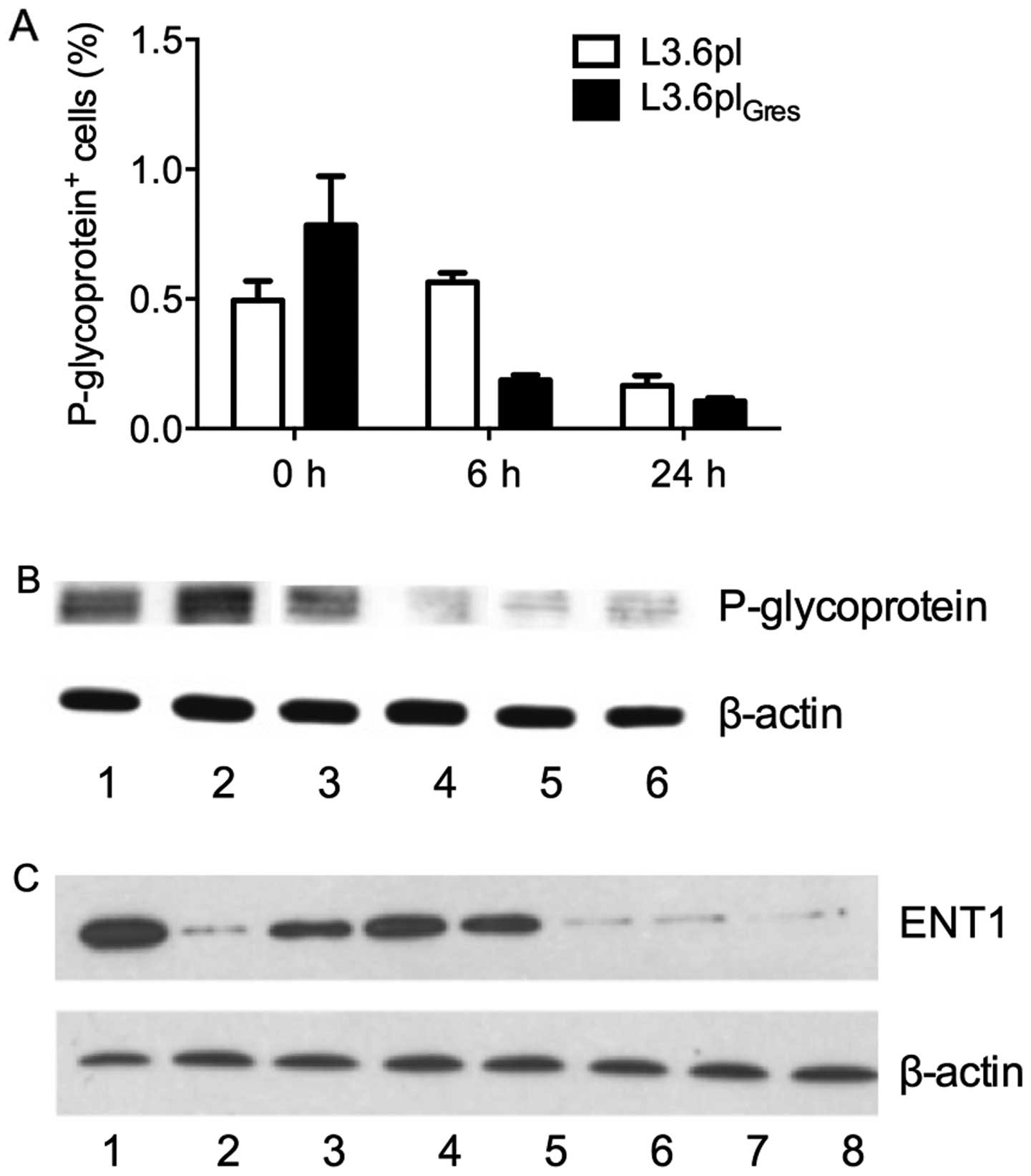

The expression level of drug transporter

proteins in L3.6pl and L3.6plGres

The expression of the drug transporter proteins P-gp

and ENT1 were then analyzed by western blotting. The results

revealed that the expression of P-gp was increased in

L3.6plGres cells as compared to L3.6pl cells, while

expression of ENT1 in L3.6plGres cells was found to be

substantially lower than in L3.6pl cells. The expression of P-gp in

both cell lines was found to decrease after 24-hour treatment with

verapamil (50 μM), and in particular, showed a marked reduction in

the L3.6plGres cells. The expression of ENT1 remained

unchanged after verapamil treatment (Fig. 7).

| Figure 7Expression of drug transporter

proteins in L3.6pl and L3.6plGres. (A) After treatment

of L3.6pl and L3.6plGres cells with verapamil (50 μM)

for 0, 6 and 24 h, all cells were analyzed by FACS. The proportion

of P-glycoprotein positive cells decreased after treatment in both

cell lines, however, significantly more in L3.6plGres

(p<0.01). (B) The protein lysates from: 1, L3.6pl; 2,

L3.6plGres; 3, L3.6pl treated with verapamil (50 μM) for

6 h; 4, L3.6pl treated with verapamil (50 μM) for 24 h; 5,

L3.6plGres treated with verapamil (50 μM) for 6 h; 6,

L3.6plGres treated with verapamil (50 μM) for 24 h. The

expression of P-glycoprotein was significantly higher in

L3.6plGres, than L3.6pl cells. Under treatment of

verapamil for 24 h, the expression level of P-glycoprotein

decreased in both cell lines, and showed a marked reduction in the

L3.6plGres cells. (C) The expression level of ENT1

before/after verapamil treatment in L3.6pl and

L3.6plGres cells. The protein lysates from: 1, L3.6pl;

2, L3.6plGres; 3, L3.6pl treated with verapamil (50 μM)

for 24 h; 4, L3.6pl treated with verapamil (100 μM) for 24 h; 5,

L3.6pl treated with verapamil (200 μM) for 24 h; 6,

L3.6plGres treated with verapamil (50 μM) for 24 h; 7,

L3.6plGres treated with verapamil (100 μM) for 24 h; 8,

L3.6plGres treated with verapamil (200 μM) for 24 h. The

results indicate that the expression of ENT1 was lower in

L3.6plGres cells than in L3.6pl cells, and were

unchanged under different concentrations (50, 100 and 200 μM) of

verapamil. |

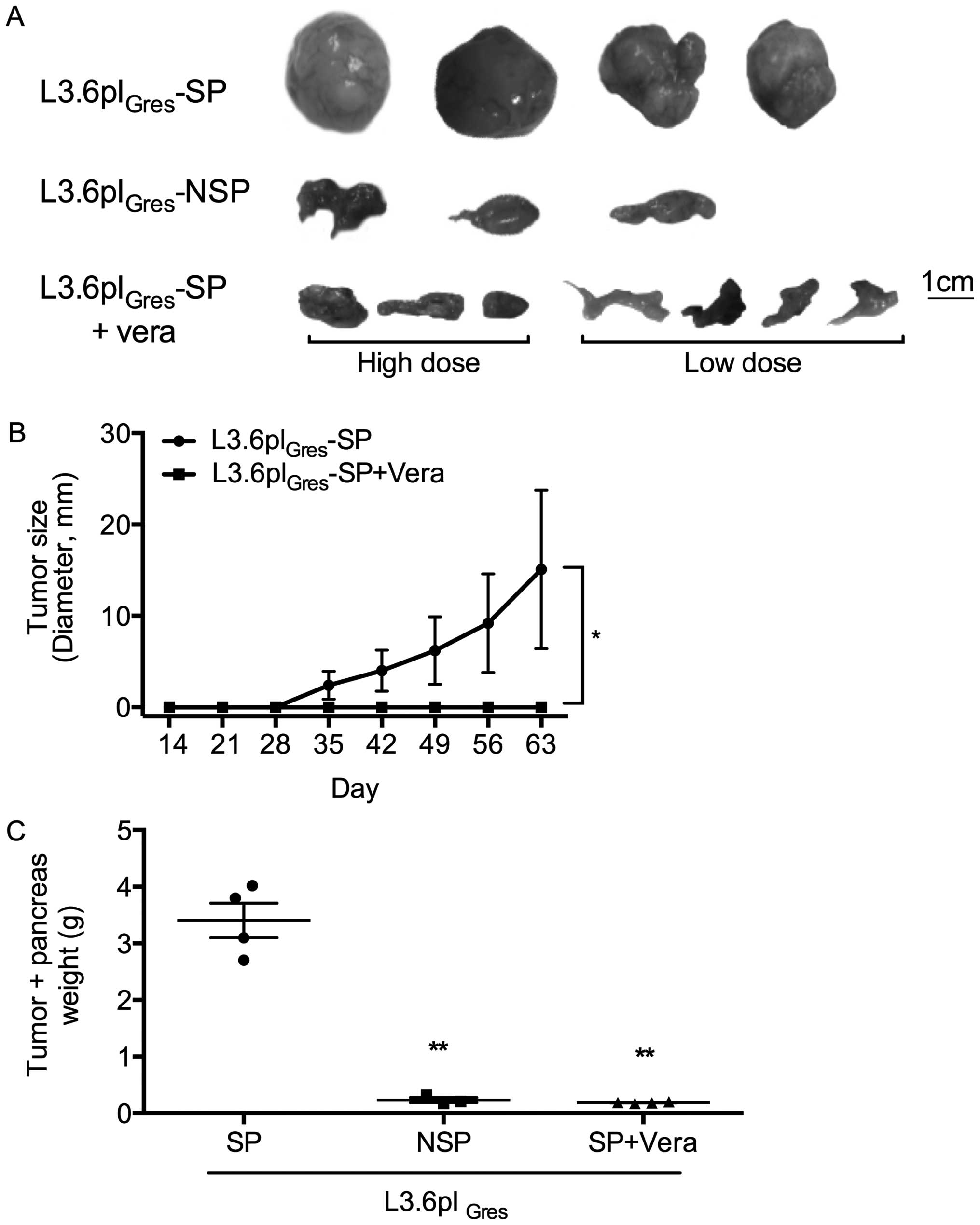

Verapamil can effectively inhibit

L3.6plGres -SP tumor growth in vivo

L3.6plGres-SP and NSP cells were injected

into the pancreas of athymic Balb/c nu/nu mice. The following

experimental groups were compared: group 1, L3.6plGres

-SP control group (5 mice); group 2, L3.6plGres-NSP cell

control group (3 mice); group 3, L3.6plGres-SP treatment

group with high concentration of verapamil (25 mg/kg BW, 10 mM, 3

mice); and group 4, L3.6plGres-SP treatment group with

low concentration of verapamil (0.5 mg/kg BW, 200 μM, 4 mice). In

all groups, verapamil treatment was initiated four weeks after

orthotopic tumor cell injection. Nine weeks later all the mice were

sacrificed. Tumors and other organs were then harvested for

analysis.

Macroscopically, the L3.6plGres-SP tumors

showed a more aggressive phenotype compared to the

L3.6plGres-NSP tumors. Verapamil treatment (low/high

concentrations) substantially inhibited tumor growth and metastasis

of the L3.6plGres-SP cells (Fig. 8). No changes in body weight, or

general behavior were observed in the verapamil treatment groups

(groups 3 and 4).

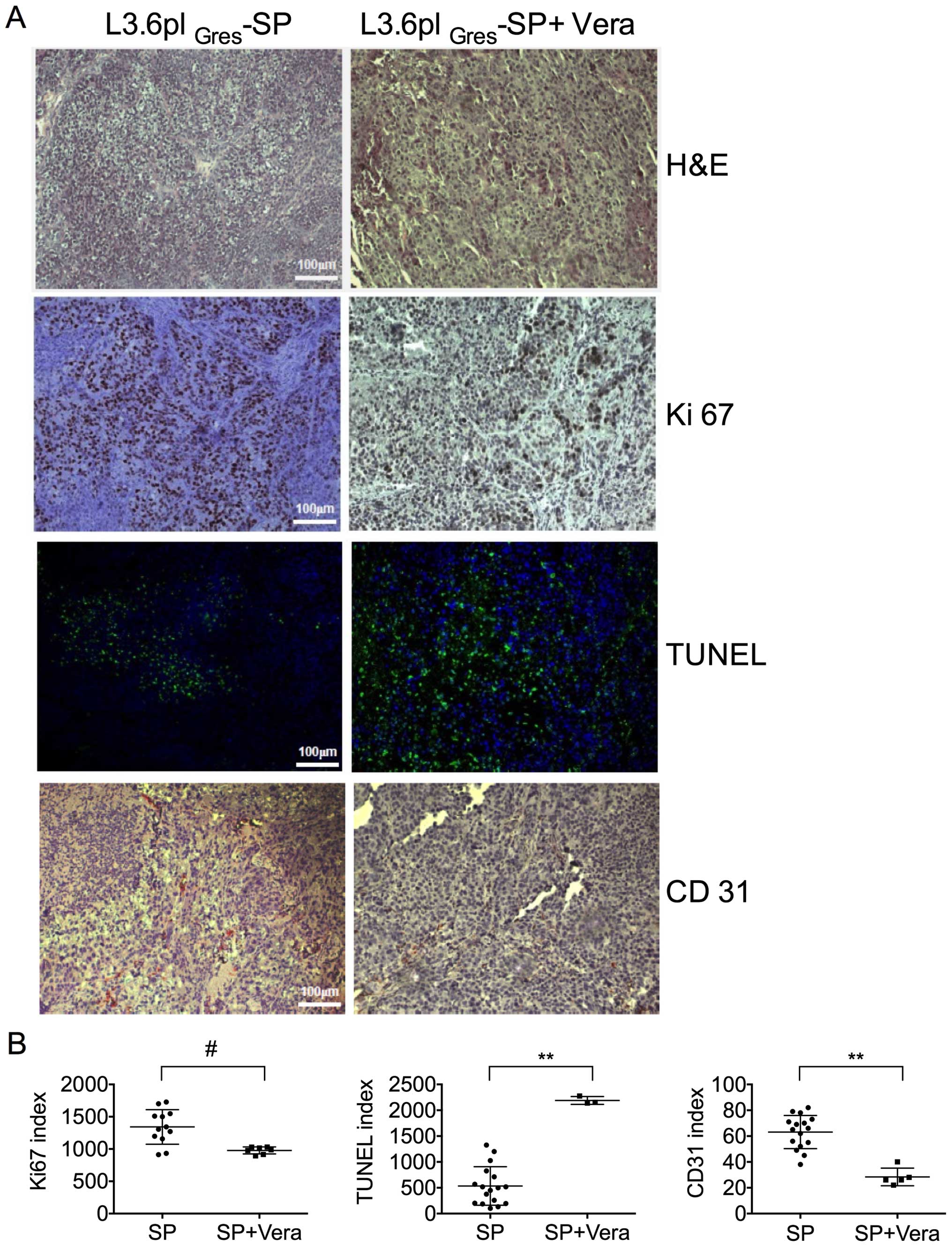

Immunohistochemical staining was used to establish a

proliferation index, microvascular density, and apoptosis level in

the experimental pancreatic tumors derived from the

L3.6plGres-SP control and verapamil treatment groups

(Fig. 9). The median percentage of

Ki67+ cells within the tumors of the verapamil

treatment group differed slightly from that seen in the

L3.6plGres-SP group. The apoptotic signal was increased

in the verapamil treatment group as compared to the

L3.6plGres-SP control group. The microvascular density

measured by CD31 staining revealed significantly reduced

angiogenesis in tumors following verapamil treatment, as compared

to the L3.6plGres-SP tumors in the control group.

H&E staining showed large, pleomorphic cells with

hyperchromatic nuclei in the L3.6plGres-SP control

group.

Discussion

The general concept of cancer stem cells (CSCs) is a

topic of increasing clinical interest. CSCs are proposed to show

stem-like self-renewal and tumor initiation characteristics that

are thought to help foster tumor recurrence and resistance to

chemotherapy. CSCs can be enriched by several methods including by

growth in serum-free defined media to induce sphere formation. They

can also be directly isolated based on their expression of specific

surface marker combinations, i.e.,

CD44+/CD24−/lin- for human breast cancers

(35),

EpCAMhigh/CD44+/CD166+ for

colorectal cancer (36),

CD34+/CD38− for acute myeloid leukemia

(37), and

Stro1+/CD105+/CD44+, a surface

marker for bone sarcoma (38). CSC

subpopulations can also be isolated by FACS sorting of side

population (SP) cells based on their ability to efflux fluorescent

dyes or chemotherapy reagents (39). SP cells have been widely linked to

CSCs in various tumors and cancer cell lines, e.g., acute myeloid

leukemia (40), neuroblastoma

(19), melanoma (41), ovarian cancer (42), glioma cell lines (43), various human gastrointestinal

cancer cell lines (44), and

pancreatic cancer cell lines, including; MIAPaCa2, PANC-1, Capan-2,

KP-1 NL and SW1990 (23,45–47).

In this study, we isolated and characterized SP

cells from a highly metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma cell line

L3.6pl, a chemotherapy-resistant variant of this line

L3.6plGres, and from the AsPC-1 human pancreatic cell

line (Fig. 2).

The SP-enriched L3.6plGres cells, which

were shown in a previous study to have significantly increased

ABCG2+, and CD24+ cells, showed higher colony

formation ability in vitro than did the parental L3.6pl

cells. L3.6plGres-SP cells also showed increased colony

formation ability relative to L3.6plGres-NSP cells

(Fig. 3) and exhibited increased

gemcitabine chemotherapy resistance relative to the

L3.6plGres-NSP cells suggesting enhanced stem cell-like

properties (Fig. 4). SP and non-SP

of AsPC-1 did not work as a good model for stem cell like SP study

by our previous data (data not shown). SP proportion is highly

abound in AsPC-1 and did not show statistic significance in

tumorigenicity in vivo. Therefore, in this study, we focused

on SP cells from L3.6pl and its corresponding resistant

variant.

These observations were then validated in

vivo. Following orthotopic implantation, significantly larger

primary pancreatic tumors, and a higher incidence of liver

metastases, were found in the L3.6plGres-SP cells, as

compared to L3.6plGres-NSP cells, supporting the

hypothesis that they show enhanced stem cell-like characteristics

(Fig. 9).

Morphologic changes were associated with the

establishment of gemcitabine-resistant L3.6pl cells. A

fibroblastoid phenotype with loss of polarity, increased

intercellular separation and pseudopodia was detected in the

L3.6plGres cells (Fig.

1). This observation is consistent with the phenomenon of

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Molecular and

phenotypic associations have been previously linked to the

establishment of chemoresistance including the acquisition of an

EMT-like cancer cell phenotype (48). SP cells have been previously

associated with chemotherapy resistance and enhanced EMT (49,50).

Goodell et al (16) have shown that the molecular pumps

responsible for H33342 efflux (used to differentiate SP from NSP

cells) are generally members of the ABC superfamily including

MDR1/P-gp, ABCG2, and MRP (7–9,51).

Verapamil, the first generation P-gp inhibitor, has been reported

to block dye efflux activity and potentially reverse the drug

resistance caused by expression of P-gp (26). We show that verapamil effectively

reduces Hoechst 33342 staining of FACS-associated SP cells in

L3.6pl, L3.6plGres, and AsPC-1 cell lines (Fig. 2). Verapamil appears to target

important characteristics associated with CRC/SP cells and may

therefore show therapeutic efficacy for treating pancreatic cancer

stem cells. We found that verapamil could also directly inhibit

cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner in vitro, and

was able to inhibit SP cells more efficiently than NSP cells in

both pancreatic cell lines tested (L3.6plGres and

AsPC-1) (Fig. 5). Verapamil was

further found to effectively prevent L3.6plGres-SP tumor

growth in orthotopic in vivo tumor models (Fig. 8 and Table I). For a potential side effect, we

checked the mice by bodyweight regular detection and animal

behaviour, and speculated that no serious side effects existed. It

is a limitation in this study that we did not have more biochemical

parameters for a better evaluation of side effect.

| Table IThe incidence of primary pancreatic

tumors as well as metastatic spread in L3.6plGres-SP,

L3.6plGres-NSP and the therapy groups is

indicated.a |

Table I

The incidence of primary pancreatic

tumors as well as metastatic spread in L3.6plGres-SP,

L3.6plGres-NSP and the therapy groups is

indicated.a

| |

L3.6plGres |

|---|

| |

|

|---|

| | | SP + verapamil |

|---|

| | |

|

|---|

| Group | SP | NSP | Low dose | High dose |

|---|

| Primary tumor | 4/5 | 0/4 | 1/3 | 0/3 |

| Liver

metastasis | 2/5 | 2/4 | 0/3 | 0/3 |

The direct effects of verapamil on pancreatic cancer

cells seen are supported by earlier reports that showed verapamil

inhibition of proliferation and induced differentiation of human

promyelocytic HL-60 cells (52), a

growth inhibitory effect on human colonic tumor cells (54), and antiproliferative effects on

brain tumor cells in vitro (55). A reversible, antiproliferative

action of verapamil on human medulloblastoma, pinealoblastoma,

glioma, and neuroblastoma tumor lines has also been reported

(55).

SP cells isolated from L3.6plGres and

AsPC-1 cell lines were more sensitive to verapamil than NSP cells.

SP-enriched L3.6plGres cells expressed higher levels of

P-gp than NSP L3.6pl cells. Verapamil treatment of

L3.6plGres cells led to a significant reduction in P-gp

expression as compared to L3.6pl cells (Fig. 7), which may explain in part the

targeted effect of verapamil detected in SP cells.

Pro-apoptotic effects of verapamil were demonstrated

by in vitro apoptosis assays (Fig. 6) and by ex vivo

immunohistochemistry analysis of the tumor samples (Fig. 9). This enhanced apoptosis by

verapamil may be explained by its actions as a calcium channel

antagonist (52,54). Calcium ions (Ca2+) are

cellular messengers that control cell and tissue physiology, and

potentially ‘death’ signals (55,56).

Calcium antagonists disrupt intracellular and extracellular

Ca2+ equilibrium (57).

Ca2+ is toxic at high concentrations, thus verapamil may

help to foster apoptosis though disruption of the Ca2+

balance.

Other ABC superfamily members are also thought to

contribute to SP chemotherapy resistance. Recently it was shown

that verapamil and its derivative-NMeOHI(2) can trigger apoptosis though

glutathione (GSH) extrusion mediated by MRP1 (58). The loss of GSH from cells can

result in increased oxidative stress, a well-recognized trigger for

apoptosis (59).

Although verapamil can enhance cytotoxicity when

used in combination with chemotherapy agents, such as

anthracyclines (28), paclitaxel

(60), epipodophyllotoxins

(61) and melphalan (62), little is known about the potential

effects of verapamil when used alone or in combination with

gemcitabine, the standard chemotherapy reagent for pancreatic

cancer. We identified combined pro-apoptotic effects of verapamil

and gemcitabine on L3.6pl but not on L3.6plGres cells.

This may be explained in part by the expression level of ENT1, a

major transporter for gemcitabine that was substantially lower in

L3.6plGres cells compared to L3.6pl cells. The absence

of ENT1 is also associated with a reduced survival in patients with

gemcitabine treated pancreatic adenocarcinoma (63).

In conclusion, this study revealed that verapamil

may act on pancreatic cancer cells in vitro by inhibiting

P-gp transporters and inducing apoptosis of stem-like SP cells in

L3.6pl, L3.6plGres and AsPC-1 cells. Verapamil can

significantly inhibit pancreatic cancer tumor growth in vivo

potentially by targeting stem-like side population cells.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Anneli Tischmacher for her

technical assistance. This study was supported by the German

Research Society (DFG) grant BR 1614/7-1 and the DKTK/DKFZ 2013

(‘Stem cells in Oncology’) to C.J.B. L.Z., Y.Z. and Q.B. were

supported by LMU-CSC (The China Scholarship Council)

scholarship.

Abbreviations:

|

ABC

|

ATP-binding cassette

|

|

CSCs

|

cancer stem cells

|

|

CNT

|

concentrative nucleoside

transporter

|

|

ENT

|

equilibrative nucleoside

transporter

|

|

EMT

|

epithelial-to-mesenchymal

transition

|

|

GSH

|

glutathione

|

|

H33342

|

Hoechst 33342

|

|

HSC

|

hematopoietic stem cells

|

|

MDR

|

multidrug resistance

|

|

MRP

|

multidrug resistance-associated

protein

|

|

PKC

|

protein kinase C

|

|

P-gp

|

P-glycoprotein

|

|

SP

|

side population

|

References

|

1

|

Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J and

Thun MJ: Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 59:225–249.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Fernandez E, La Vecchia C, Porta M, Negri

E, Lucchini F and Levi F: Trends in pancreatic cancer mortality in

Europe, 1955–1989. Int J Cancer. 57:786–792. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Chen M, Xue X, Wang F, An Y, Tang D, Xu Y,

Wang H, Yuan Z, Gao W, Wei J, et al: Expression and promoter

methylation analysis of ATP-binding cassette genes in pancreatic

cancer. Oncol Rep. 27:265–269. 2012.

|

|

4

|

Arbuck SG: Overview of chemotherapy for

pancreatic cancer. Int J Pancreatol. 7:209–222. 1990.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Suwa H, Ohshio G, Arao S, Imamura T,

Yamaki K, Manabe T, Imamura M, Hiai H and Fukumoto M:

Immunohistochemical localization of P-glycoprotein and expression

of the multidrug resistance-1 gene in human pancreatic cancer:

Relevance to indicator of better prognosis. Jpn J Cancer Res.

87:641–649. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Grant CE, Valdimarsson G, Hipfner DR,

Almquist KC, Cole SP and Deeley RG: Overexpression of multidrug

resistance-associated protein (MRP) increases resistance to natural

product drugs. Cancer Res. 54:357–361. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Germann UA, Chambers TC, Ambudkar SV,

Licht T, Cardarelli CO, Pastan I and Gottesman MM: Characterization

of phosphorylation-defective mutants of human P-glycoprotein

expressed in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 271:1708–1716. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Childs S and Ling V: The MDR superfamily

of genes and its biological implications. Important Adv Oncol.

21–36. 1994.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chin KV, Pastan I and Gottesman MM:

Function and regulation of the human multidrug resistance gene. Adv

Cancer Res. 60:157–180. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Thomas H and Coley HM: Overcoming

multidrug resistance in cancer: an update on the clinical strategy

of inhibiting P-glycoprotein. Cancer Control. 10:159–165.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hagmann W, Jesnowski R and Löhr JM:

Interdependence of gemcitabine treatment, transporter expression,

and resistance in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Neoplasia.

12:740–747. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Mackey JR, Mani RS, Selner M, Mowles D,

Young JD, Belt JA, Crawford CR and Cass CE: Functional nucleoside

transporters are required for gemcitabine influx and manifestation

of toxicity in cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 58:4349–4357.

1998.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Ritzel MW, Ng AM, Yao SY, Graham K, Loewen

SK, Smith KM, Ritzel RG, Mowles DA, Carpenter P, Chen XZ, et al:

Molecular identification and characterization of novel human and

mouse concentrative Na+-nucleoside cotransporter

proteins (hCNT3 and mCNT3) broadly selective for purine and

pyrimidine nucleosides (system cib). J Biol Chem. 276:2914–2927.

2001. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Garcia-Manteiga J, Molina-Arcas M, Casado

FJ, Mazo A and Pastor-Anglada M: Nucleoside transporter profiles in

human pancreatic cancer cells: Role of hCNT1 in

2′,2′-difluorodeoxy-cytidine- induced cytotoxicity. Clin Cancer

Res. 9:5000–5008. 2003.

|

|

15

|

Al-Hajj M and Clarke MF: Self-renewal and

solid tumor stem cells. Oncogene. 23:7274–7282. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Goodell MA, Brose K, Paradis G, Conner AS

and Mulligan RC: Isolation and functional properties of murine

hematopoietic stem cells that are replicating in vivo. J Exp Med.

183:1797–1806. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bunting KD, Zhou S, Lu T and Sorrentino

BP: Enforced P-glycoprotein pump function in murine bone marrow

cells results in expansion of side population stem cells in vitro

and repopulating cells in vivo. Blood. 96:902–909. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Zhou S, Schuetz JD, Bunting KD, Colapietro

AM, Sampath J, Morris JJ, Lagutina I, Grosveld GC, Osawa M,

Nakauchi H, et al: The ABC transporter Bcrp1/ABCG2 is expressed in

a wide variety of stem cells and is a molecular determinant of the

side-population phenotype. Nat Med. 7:1028–1034. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hirschmann-Jax C, Foster AE, Wulf GG,

Nuchtern JG, Jax TW, Gobel U, Goodell MA and Brenner MK: A distinct

‘side population’ of cells with high drug efflux capacity in human

tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:14228–14233. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Benchaouir R, Rameau P, Decraene C,

Dreyfus P, Israeli D, Piétu G, Danos O and Garcia L: Evidence for a

resident subset of cells with SP phenotype in the C2C12 myogenic

line: A tool to explore muscle stem cell biology. Exp Cell Res.

294:254–268. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Ambudkar SV, Dey S, Hrycyna CA,

Ramachandra M, Pastan I and Gottesman MM: Biochemical, cellular,

and pharmacological aspects of the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev

Pharmacol Toxicol. 39:361–398. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yao J, Cai HH, Wei JS, An Y, Ji ZL, Lu ZP,

Wu JL, Chen P, Jiang KR, Dai CC, et al: Side population in the

pancreatic cancer cell lines SW1990 and CFPAC-1 is enriched with

cancer stem-like cells. Oncol Rep. 23:1375–1382. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zhang SN, Huang FT, Huang YJ, Zhong W and

Yu Z: Characterization of a cancer stem cell-like side population

derived from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells. Tumori.

96:985–992. 2010.

|

|

24

|

Vohra J: Verapamil in cardiac arrhythmias:

An overview. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl. 6:129–134.

1982.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bellamy WT: P-glycoproteins and multidrug

resistance. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 36:161–183. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Broxterman HJ, Lankelma J and Pinedo HM:

How to probe clinical tumour samples for P-glycoprotein and

multidrug resistance-associated protein. Eur J Cancer.

32A:1024–1033. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ince P, Appleton DR, Finney KJ, Sunter JP

and Watson AJ: Verapamil increases the sensitivity of primary human

colorectal carcinoma tissue to vincristine. Br J Cancer.

53:137–139. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Merry S, Fetherston CA, Kaye SB, Freshney

RI and Plumb JA: Resistance of human glioma to adriamycin in vitro:

The role of membrane transport and its circumvention with

verapamil. Br J Cancer. 53:129–135. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Morrow M, Wait RB, Rosenthal RA and

Gamelli RL: Verapamil enhances antitumor activity without

increasing myeloid toxicity. Surgery. 101:63–68. 1987.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Tsuruo T, Iida H, Tsukagoshi S and Sakurai

Y: Overcoming of vincristine resistance in P388 leukemia in vivo

and in vitro through enhanced cytotoxicity of vincristine and

vinblastine by verapamil. Cancer Res. 41:1967–1972. 1981.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bruns CJ, Harbison MT, Kuniyasu H, Eue I

and Fidler IJ: In vivo selection and characterization of metastatic

variants from human pancreatic adenocarcinoma by using orthotopic

implantation in nude mice. Neoplasia. 1:50–62. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Guillermet-Guibert J, Davenne L,

Pchejetski D, Saint-Laurent N, Brizuela L, Guilbeau-Frugier C,

Delisle MB, Cuvillier O, Susini C and Bousquet C: Targeting the

sphingolipid metabolism to defeat pancreatic cancer cell resistance

to the chemotherapeutic gemcitabine drug. Mol Cancer Ther.

8:809–820. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E and Singh

H: Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to

the nuclear lamina. Nature. 452:243–247. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Georges E, Bradley G, Gariepy J and Ling

V: Detection of P-glycoprotein isoforms by gene-specific monoclonal

antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 87:152–156. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A,

Morrison SJ and Clarke MF: Prospective identification of

tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

100:3983–3988. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, Liu R, Wang

X, Cho RW, Hoey T, Gurney A, Huang EH, Simeone DM, et al:

Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104:10158–10163. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Clayton S and Mousa SA: Therapeutics

formulated to target cancer stem cells: Is it in our future? Cancer

Cell Int. 11:72011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Gibbs CP, Kukekov VG, Reith JD,

Tchigrinova O, Suslov ON, Scott EW, Ghivizzani SC, Ignatova TN and

Steindler DA: Stem-like cells in bone sarcomas: Implications for

tumorigenesis. Neoplasia. 7:967–976. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Challen GA and Little MH: A side order of

stem cells: The SP phenotype. Stem Cells. 24:3–12. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Wulf GG, Wang RY, Kuehnle I, Weidner D,

Marini F, Brenner MK, Andreeff M and Goodell MA: A leukemic stem

cell with intrinsic drug efflux capacity in acute myeloid leukemia.

Blood. 98:1166–1173. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Grichnik JM, Burch JA, Schulteis RD, Shan

S, Liu J, Darrow TL, Vervaert CE and Seigler HF: Melanoma, a tumor

based on a mutant stem cell? J Invest Dermatol. 126:142–153. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Szotek PP, Pieretti-Vanmarcke R, Masiakos

PT, Dinulescu DM, Connolly D, Foster R, Dombkowski D, Preffer F,

Maclaughlin DT and Donahoe PK: Ovarian cancer side population

defines cells with stem cell-like characteristics and Mullerian

inhibiting substance responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

103:11154–11159. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kondo T, Setoguchi T and Taga T:

Persistence of a small subpopulation of cancer stem-like cells in

the C6 glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:781–786. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Haraguchi N, Utsunomiya T, Inoue H, Tanaka

F, Mimori K, Barnard GF and Mori M: Characterization of a side

population of cancer cells from human gastrointestinal system. Stem

Cells. 24:506–513. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Asuthkar S, Stepanova V, Lebedeva T,

Holterman AL, Estes N, Cines DB, Rao JS and Gondi CS:

Multifunctional roles of urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) in

cancer stemness and chemoresistance of pancreatic cancer. Mol Biol

Cell. 24:2620–2632. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Zhou J, Wang CY, Liu T, Wu B, Zhou F,

Xiong JX, Wu HS, Tao J, Zhao G, Yang M, et al: Persistence of side

population cells with high drug efflux capacity in pancreatic

cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 14:925–930. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kabashima A, Higuchi H, Takaishi H,

Matsuzaki Y, Suzuki S, Izumiya M, Iizuka H, Sakai G, Hozawa S,

Azuma T, et al: Side population of pancreatic cancer cells

predominates in TGF-beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal

transition and invasion. Int J Cancer. 124:2771–2779. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Yang AD, Fan F, Camp ER, van Buren G, Liu

W, Somcio R, Gray MJ, Cheng H, Hoff PM and Ellis LM: Chronic

oxaliplatin resistance induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

in colorectal cancer cell lines. Clin Cancer Res. 12:4147–4153.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Okano M, Konno M, Kano Y, Kim H, Kawamoto

K, Ohkuma M, Haraguchi N, Yokobori T, Mimori K, Yamamoto H, et al:

Human colorectal CD24+ cancer stem cells are susceptible

to epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Int J Oncol. 45:575–580.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhao Y, Bao Q, Schwarz B, Zhao L,

Mysliwietz J, Ellwart J, Renner A, Hirner H, Niess H, Camaj P, et

al: Stem cell-like side populations in esophageal cancer: A source

of chemotherapy resistance and metastases. Stem Cells Dev.

23:180–192. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Doyle L and Ross DD: Multidrug resistance

mediated by the breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2).

Oncogene. 22:7340–7358. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Jensen RL, Lee YS, Guijrati M, Origitano

TC, Wurster RD and Reichman OH: Inhibition of in vitro meningioma

proliferation after growth factor stimulation by calcium channel

antagonists: Part II - Additional growth factors, growth factor

receptor immunohistochemistry, and intracellular calcium

measurements. Neurosurgery. 37:937–946; discussion 946-937. 1995.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Zhao Y, Zhao L, Ischenko I, Bao Q, Schwarz

B, Nieß H, Wang Y, Renner A, Mysliwietz J, Jauch KW, et al:

Antisense inhibition of microRNA-21 and microRNA-221 in

tumor-initiating stem-like cells modulates tumorigenesis,

metastasis, and chemotherapy resistance in pancreatic cancer.

Target Oncol. 10:535–548. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Jensen RL, Petr M and Wurster RD: Calcium

channel antagonist effect on in vitro meningioma signal

transduction pathways after growth factor stimulation.

Neurosurgery. 46:692–702; discussion 702-693. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Berridge MJ, Lipp P and Bootman MD: Signal

transduction. The calcium entry pas de deux. Science.

287:1604–1605. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Hajnóczky G, Csordás G, Madesh M and

Pacher P: Control of apoptosis by IP(3) and ryanodine receptor

driven calcium signals. Cell Calcium. 28:349–363. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Cao QZ, Niu G and Tan HR: In vitro growth

inhibition of human colonic tumor cells by Verapamil. World J

Gastroenterol. 11:2255–2259. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Trompier D, Chang XB, Barattin R, du

Moulinet D'Hardemare A, Di Pietro A and Baubichon-Cortay H:

Verapamil and its derivative trigger apoptosis through glutathione

extrusion by multidrug resistance protein MRP1. Cancer Res.

64:4950–4956. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ghibelli L, Coppola S, Rotilio G, Lafavia

E, Maresca V and Ciriolo MR: Non-oxidative loss of glutathione in

apoptosis via GSH extrusion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

216:313–320. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Wang F, Zhang D, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Zheng D,

Hao L, Duan C, Jia L, Liu G and Liu Y: Synergistic effect of

folate-mediated targeting and verapamil-mediated P-gp inhibition

with paclitaxel-polymer micelles to overcome multi-drug resistance.

Biomaterials. 32:9444–9456. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Yalowich JC and Ross WE: Verapamil-induced

augmentation of etoposide accumulation in L1210 cells in vitro.

Cancer Res. 45:1651–1656. 1985.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Robinson BA, Clutterbuck RD, Millar JL and

McElwain TJ: Verapamil potentiation of melphalan cytotoxicity and

cellular uptake in murine fibrosarcoma and bone marrow. Br J

Cancer. 52:813–822. 1985. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Spratlin J, Sangha R, Glubrecht D, Dabbagh

L, Young JD, Dumontet C, Cass C, Lai R and Mackey JR: The absence

of human equilibrative nucleoside transporter 1 is associated with

reduced survival in patients with gemcitabine-treated pancreas

adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 10:6956–6961. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|