Cancer is the second leading cause of global

mortality, with ~20 million cases and 9.7 million deaths reported

in 2022 (1). While therapeutic

strategies such as surgical resection, chemotherapy, radiotherapy,

targeted therapy and immunotherapy have advanced, drug resistance

and adverse reactions undermine clinical outcomes (2,3).

Drug resistance not only drives tumor recurrence but also

perpetuates cancer as a key public health challenge (4).

Current investigations into therapy resistance

mechanisms extend beyond ATP-binding cassette (ABC)

transporter-mediated drug efflux to encompass metabolic

reprogramming, exemplified by the Warburg effect, alongside dynamic

mitochondrial interactions (5,6).

Cancer cells exhibit a range of metabolic adaptations, enabling

them to secure energy despite limited nutrient and oxygen

availability (7). In the 1920s,

Otto Warburg demonstrated that cancer cells preferentially generate

ATP through glycolysis, even in the presence of sufficient oxygen

(8). Research on cancer cell

metabolism primarily focuses on glycolysis, glutamine metabolism

and mitochondrial protective mechanisms (9,10).

Moreover, abnormal lipid metabolism is a hallmark of metabolic

reprogramming (11). These

adaptations create interconnected networks that sustain

tumorigenesis and therapeutic evasion.

Targeting cancer metabolism gained momentum in the

20th century with nucleotide metabolism inhibitors such as

methotrexate (12). However,

clinical setbacks with glycolysis inhibitors such as 2-deoxyglucose

(13) shifted focus toward

oncogene-targeting therapies due to the limited efficacy and

undesirable side effects. Metabolic intervention strategies have

been facilitated by discoveries linking non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) to

cancer molecular biology. ncRNAs are a class of RNAs that lack

protein-coding potential and were once considered non-essential

components of the genome. Functionally diverse ncRNAs, including

long ncRNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs) and microRNAs

(miRNAs or miRs) (14), regulate

tumor progression through nuclear chromatin remodeling, cytoplasmic

mRNA interactions and competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network

formation (15,16). In addition to their roles in cell

proliferation, invasion, migration, and apoptosis, ncRNAs

orchestrate metabolic reprogramming across glycolysis,

mitochondrial function and glutamine and lipid metabolism (17), thereby driving drug resistance in

multiple types of cancer, such as prostate and breast cancer (BC)

(18,19). ncRNAs have thus become an

increasingly recognized target for cancer treatment, as well as

potential biomarkers (14,19).

The present review aimed to outline the mechanisms through which

metabolic changes influence drug resistance in tumor cells and how

ncRNAs mediate drug resistance via metabolic regulation.

Metabolism-regulating ncRNAs hold promise as both biomarkers and

therapeutic targets for overcoming drug resistance in cancer.

Chromosomal variability and immune escape predispose

tumors to both intrinsic and acquired resistance to treatment.

Intrinsic drug resistance stems from cancer cell genetic and

epigenetic traits, making certain types of tumor hard to treat with

conventional therapy (20). For

example, in colorectal cancer (CRC), the activation of the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway enhances stem cell characteristics,

thereby rendering the cells resistant to cisplatin (20). Acquired drug resistance develops

gradually under therapeutic pressure, driven by dynamic changes in

cancer cell behavior and signaling pathways (21). In parallel with tumor metabolism

research, drug resistance is frequently driven by metabolic

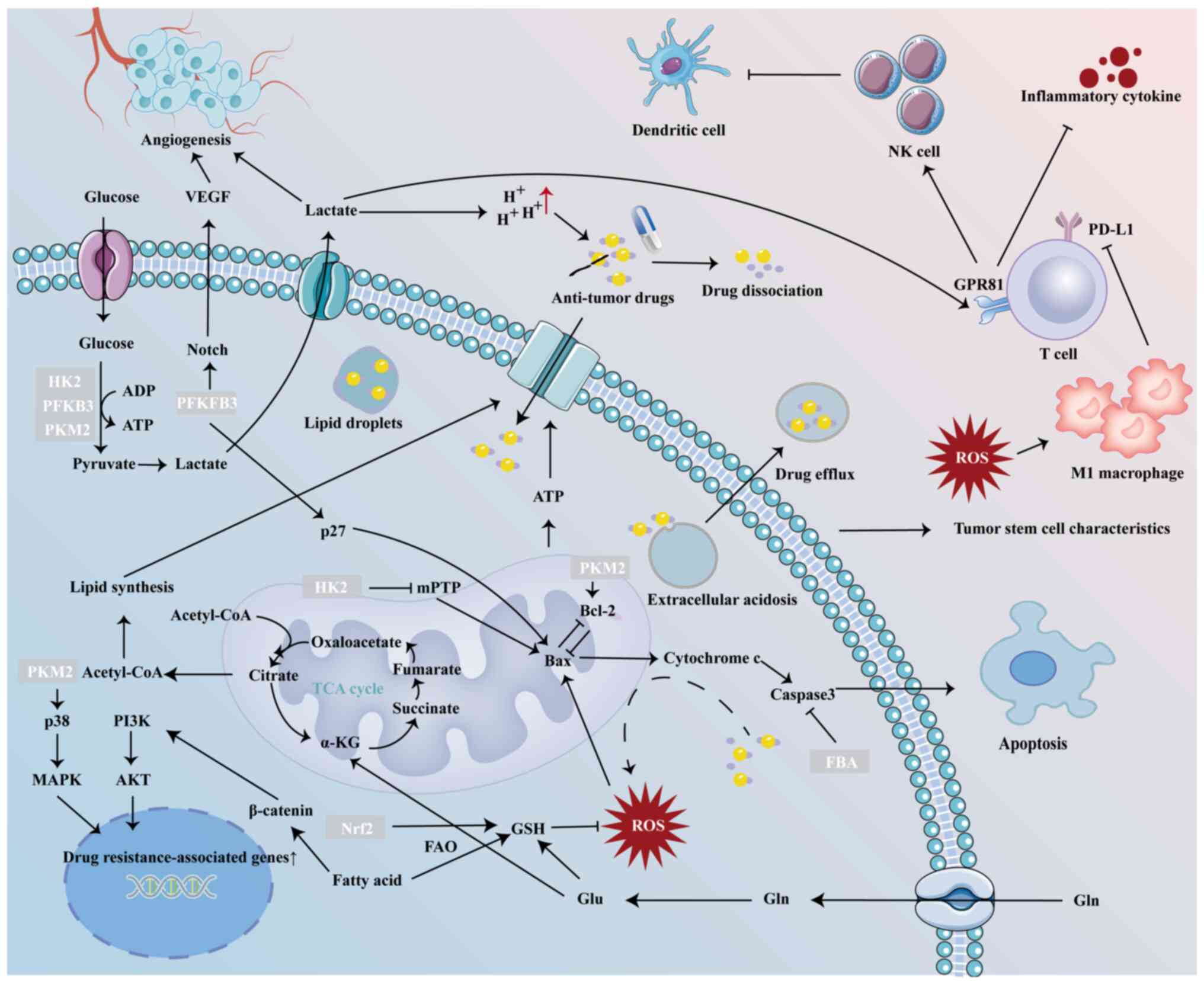

reprogramming (10,17) (Fig.

1). As a hallmark of cancer, metabolic reprogramming supplies

the essential nutrients and energy required for tumor progression,

while ncRNAs exert a notable impact. ncRNAs modulate tumor

metabolism by activating metabolism-associated signaling pathways

or targeting key metabolic enzymes (22,23). In metabolically dysregulated tumor

cells, ncRNAs display aberrant expression, influenced by factors

such as DNA methylation (24),

transcription factors (25), and

hypoxic or oncogenic stimuli (26,27). Additionally, ncRNAs can be

transferred between cells via exosomes. For example, temozolomide

(TMZ)-resistant glioma cells transfer circ-0072083 to TMZ-sensitive

cells through exosomes (28). The

deregulation of ncRNAs disrupts metabolic pathways in tumor cells,

thereby driving metabolic reprogramming and altering tumor

sensitivity to therapeutic intervention (Table I).

Aerobic glycolysis serves as a prominent example of

a reprogrammed metabolic pathway in cancer cells. Tumor cells

uptake glucose in large quantities, which is converted to pyruvate

by enzymes such as hexokinase (HK), phosphofructokinase (PFK) and

pyruvate kinase (PK). Pyruvate is subsequently converted to lactic

acid by lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) or transported to the

mitochondria, where it is catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)

to form acetyl-CoA (9).

Glycolysis contributes to drug resistance through

multiple mechanism. Glycolysis provides cancer cells with

sufficient energy to maintain malignancy (6). 3-bromopyruvate is a glycolysis

inhibitor that markedly decreases glycolytic activity by inhibiting

the enzyme HK2. This inhibition impairs the energy supply derived

from glycolysis, leading to a decrease in ATP and glutathione (GSH)

levels in tumor cells, thereby enhancing their sensitivity to

chloroethylnitrosoureas, a bifunctional anti-tumor alkylating agent

(29). In drug-resistant cancer

cells, the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway is activated, which regulates

glycolysis (30), causing higher

ATP levels than in drug-sensitive cells (31,32). This process provides the necessary

energy for ABC transporters to facilitate drug efflux (33). Chondroitin sulfate disrupts

mitochondrial electron transport and glycolysis to deplete ATP.

This energy depletion impairs P-glycoprotein (P-gp) activity,

thereby decreasing doxorubicin efflux (34).

Numerous glycolysis enzymes are associated with cell

death. For example, HK2 translocates to mitochondria where it

inhibits mitochondrial permeability transition pores to block

cytochrome c/Bax release, enhancing tumor cell survival (35). Mitochondrial PKM2 binds BCL2 to

suppress reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated apoptosis (36). Additionally,

fructose-1,6-diphosphate aldolase delays drug-induced apoptosis by

decreasing caspase-3 activity through catalytic product

accumulation (37). Furthermore,

PDH kinase 3 (PDK3) overexpression promotes lycorine hydrochloride

resistance in glioblastoma cells via apoptosis inhibition (38).

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-biphosphatase 3 (PFKFB3)

activates cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), leading to the

phosphorylation of p27, a potent inhibitor of G1/S transformation

and activator of apoptosis (39).

PFKFB3 also regulates angiogenesis through vascular endothelial

growth factor (VEGF)-mediated endothelial morphogenesis and Notch

signaling suppression (40). The

morphology of tumor blood vessels is irregular. This leads to

localized nutritional and oxygen deficiency, which in turn promote

tumor metastasis (41). Combining

anti-angiogenic therapies that target PFKFB3 reverses the abnormal

changes in tumor blood vessels, improving the delivery of

chemotherapy drugs (41).

The Warburg effect results in the accumulation of

lactic acid, which dilates blood vessels and stimulates

angiogenesis to enhance local energy supply through an increase in

oxygen and nutrients (42).

Excessive lactic acid also decreases the pH around tumor cells,

creating a pH gradient both inside and outside the cells (43). Weakly basic drugs dissociate in

the acidic extracellular environment, hindering their passage

through the cell membrane or sequestering them in acidic lysosomal

vesicles (43,44), rendering them ineffective.

Conversely, weakly acidic drugs enter cells but are often

inactivated before reaching their target due to the alkaline

intracellular conditions (45).

Furthermore, extracellular acidosis promotes drug efflux via P-gp

(46), multidrug

resistance-related protein 1 (MRP1) (47) and intracellular acidic vesicles

(48), further contributing to

chemotherapy resistance. Elevated lactate levels serve as agonists

for the G protein-coupled receptor GPR81, which is expressed on

immune cells. Activation of GPR81 decreases the release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines from T cells and may impair the function

of natural killer cells, partially through recruitment of

monocyte-derived dendritic cells (49). Monocarboxylate

transporter-1-mediated lactate transport is essential for

maintaining intracellular pH in cancer cells, a process that

supports the stem cell properties of pancreatic adenocarcinoma and

glioblastoma stem cells (50,51). Additionally, when several key

enzymes, such as HK2, PFKFB3 and PKM2, are abnormally elevated, the

Wnt/β-catenin, Erk1/2 and YAP/Hippo signaling pathways become

activated (52-54). These pathways are recognized as

key regulators that promote resistance to anti-cancer drugs.

In solid tumors, cancer cells frequently exist in a

hypoxic environment, where they tend to derive energy primarily

through glycolysis. HIF-1 serves as a crucial regulator of cancer

cell responses to hypoxia and facilitates metabolic switching,

while HIF-1α is an important subtype (55). The enhancement of glycolysis by

HIF-1 is associated with its ability to induce the expression of

various glycolytic enzymes at the transcriptional level (56). These enzymes differ from the

subtypes of glycolytic enzymes present in non-malignant cells,

including HK2, PKM and LDHA, playing a key role in the metabolic

shift of cancer cells from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis

(57). Besides, HIF-1α also

enhances the expression of Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa interacting

protein 3, which triggers mitochondrial selective autophagy,

thereby decreasing oxidative metabolism in cancer cells (58).

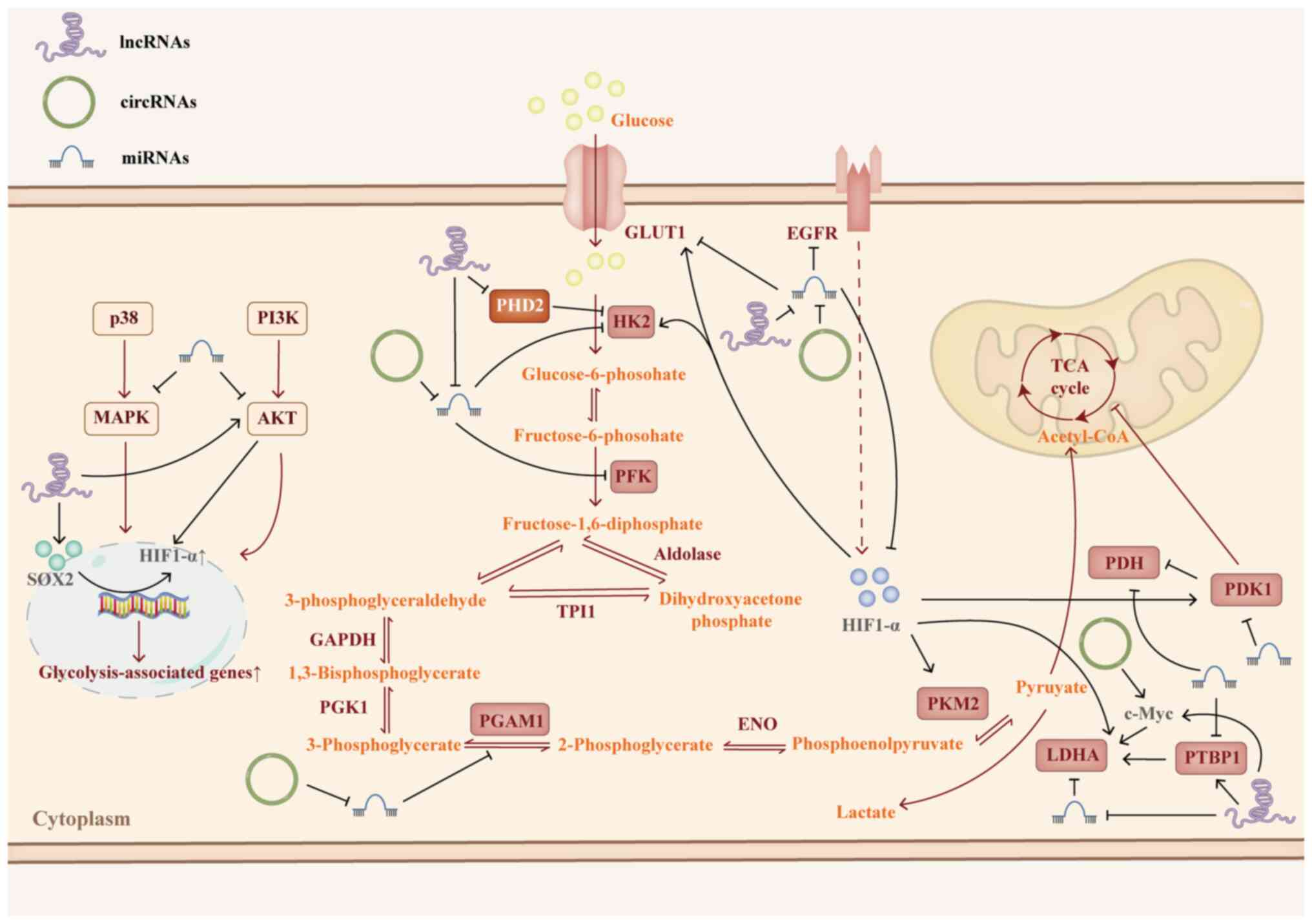

A number of ncRNAs regulate HIF-1α to promote

glycolysis. For example, circHIF1A upregulates HIF1α by

competitively binding miR-361-5p, leading to the overexpression of

enzymes such as glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) and LDHA. In a

xenograft model, silencing circHIF1A enhances sensitivity to

cetuximab treatment (59).

Similarly, circNRIP1 acts as a miR-138-5p sponge, promoting

HIF-1α-dependent glycolysis and contributing to 5-fluorouracil (FU)

resistance in gastric cancer (GC) (60). Li et al (61) demonstrated that lncRNA

RP11-536K7.3 recruits sex-determining region Y-box2 (SOX2) to

activate Ubiquitin-specific protease 7 (USP7) transcription, which

stabilizes HIF-1α by deubiquitination, thus enhancing glycolysis

and conferring resistance to oxaliplatin in CRC. In BC,

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) transfer HIF1-stabilizing

lncRNA HISLA to cancer cells via extracellular vesicles. HISLA

facilitates glycolysis and enhances resistance to

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis by preventing the interaction

between prolyl-4-hydroxylase domain protein 2 and HIF-1.

Additionally, elevated HIF-1 induces lactic acid release from BC

cells, which upregulates HISLA expression in TAMs, creating a

positive feedback loop (62).

Such positive feedback mechanisms of HIF-1α on ncRNAs are common.

For example, lncRNA HIF1α-AS1 activates AKT, promoting the

phosphorylation of Y-box binding protein 1 (YB1), which recruits

phosphorylated-YB1 to HIF-1α mRNA, enhancing its translation. HIF1α

directly binds the HIF1α-AS1 promoter, driving its transcription

(63). HIF1α also regulates the

transcription of circZNF91, notably increasing its presence in

exosomes derived from hypoxic pancreatic cancer (PC) cells.

circZNF91 is subsequently transferred to normoxic PC cells, where

it competitively binds miR-23b-3p, thereby alleviating miR-23b-3p's

inhibition of sirtuin1 (SIRT1). Elevated SIRT1 then promotes

glycolysis and confers resistance to gemcitabine (GEM) in PC cells

(64).

GLUT is a high-affinity membrane protein responsible

for glucose uptake into the cytoplasm. In cancer cells, GLUT1 is

often overexpressed, facilitating enhanced glucose uptake to meet

the energy demands required for aerobic glycolysis (62). A recent study (65) indicated that elevated GLUT1

expression in endometrial cancer (EC) is associated with increased

cell proliferation and invasion and glycolysis. Moreover, GLUT1

overexpression promotes the expression of MMP1, MMP14 and Cyclin D1

in EC cells (66).

Dual-luciferase assays confirmed GLUT1 as a direct target of

miR-140 and miR-143, which suppress EC cell proliferation and

glycolysis by inhibiting GLUT1 expression, thereby enhancing

sensitivity to Paclitaxel (PTX) (66). Additionally, circRNA-0002130,

secreted in serum exosomes of patients with non-small cell lung

cancer (NSCLC), promotes glycolysis and exacerbates resistance to

osimertinib. Mechanistically, circRNA-0002130 serves as a sponge

for miR-498, which targets GLUT1, thereby indirectly upregulating

GLUT1 expression in NSCLC cells (67). Furthermore, miR-1291-5p and

miR-218 serve as direct regulators of GLUT1, counteracting

cisplatin resistance in pancreatic and bladder cancer cells

(68,69).

HKs, located in the cytoplasm, are the primary

rate-limiting enzymes in glycolysis. HKs catalyzes the

phosphorylation of glucose to form glucose-6-phosphate,

representing the initial step in the glycolytic pathway (70). HK2, in particular, is

overexpressed in numerous types of cancer and is associated with

resistance to chemotherapy (34).

A study demonstrated that HK2 can enhance cisplatin-induced

phosphorylation of ERK1/2, thereby promoting cellular autophagy

induced by cisplatin (52).

miRNAs can directly target the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of HK2

to suppress its expression, including miR-708-5p, miR-202,

miR-125b-5p and miR-216b-5p (71-74). These miRNAs inhibit glycolysis by

downregulating HK2 expression. However, in cancer cells, these

miRNAs may be suppressed by upstream lncRNAs, contributing to drug

resistance (71-74), along with increased glucose uptake

and lactate secretion (74,75). For example, lncRNA-UCA1,

functioning as an oncogene in both solid and hematological tumors,

is associated with decreased drug sensitivity. Overexpression of

UCA1 promotes glycolysis by upregulating HK2, and UCA1 can

indirectly regulate HK2 by sponging miR-125a, thereby promoting

drug resistance (76). Inhibiting

UCA1 enhances the sensitivity of cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs

such as PTX and doxorubicin (76,77).

PFK, located in the cytoplasm, is divided into two

subtypes: PFK1, which catalyzes the conversion of fructose

6-phosphate to fructose-1,6-bisphosphate, marking the second

rate-limiting step in glycolysis, and PFKFB, which converts

fructose-6-phosphate to fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F2,6P2)

(70). PFKFB3, the most active

isoform of PFKFB, is upregulated in numerous types of cancer in

response to activation of hypoxic signals, RAS signaling, estrogen

receptor and P53 mutations, driving glycolytic metabolism in tumors

(40). PFKFB3 generates F2,6P2,

which activates CDKs. This triggers CDK-mediated phosphorylation of

p27, leading to its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation via

CDK1, thereby reducing p27 levels (40). PFKFB3 also enhances cancer cell

stemness and promotes resistance to numerous chemotherapeutic

agents by upregulating the YAP/Hippo signaling pathway in small

cell lung carcinoma (53). In

CRC, miR-488 has been shown to target and inhibit PFKFB3 expression

(78). High levels of PFKFB3

promote the proliferation, invasion and migration of CRC cells,

while also contributing to resistance to chemotherapy agents such

as 5-FU and oxaliplatin (78).

Similarly, the circ-SAMD4A is highly expressed in CRC. SAMD4A can

indirectly upregulate PFKFB3 by sponging miR-545-3p, thereby

inhibiting apoptosis and decreasing sensitivity to 5-FU in CRC

cells through the miR-545-3p/PFKFB3 axis (79).

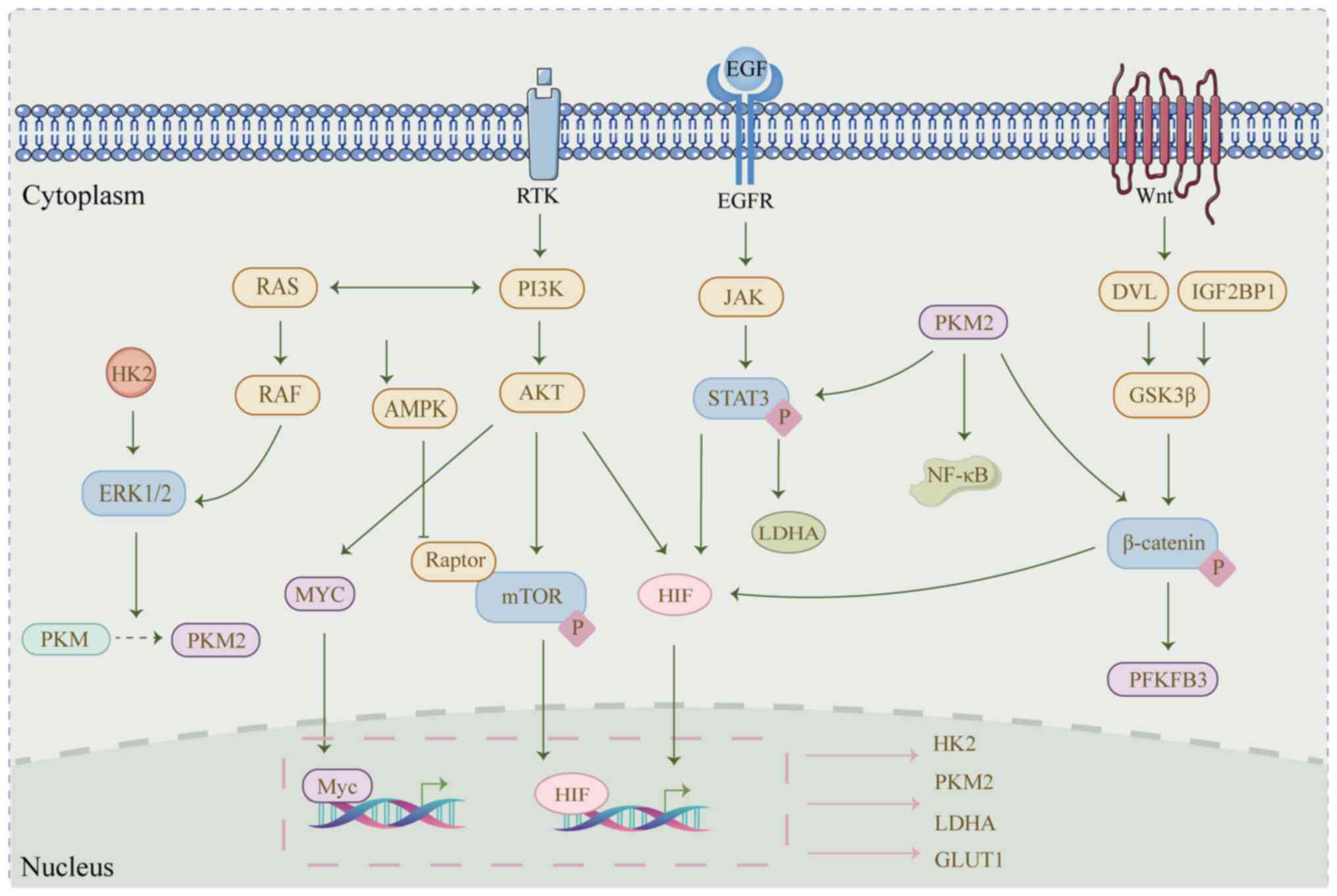

PKM2 catalyzes the final rate-limiting step of

glycolysis in cancer cells, producing pyruvate and ATP (80). The upregulation of PKM2 isoforms

in cancer is associated with drug resistance (81). In the cytoplasm, PKM2 facilitates

the process of glycolysis. Following post-translational

modification, PKM2 is translocated to the nucleus, where it serves

as a transcriptional co-activator for STAT3, β-catenin and NF-κB.

This activates drug resistance-related genes, which enhance cancer

drug resistance (54). TGF-β and

STAT3 synergistically promote the expression of PKM2, which

upregulates PD-L1 expression in cancer cells, further enhancing

cancer immune escape (82).

Recent studies (83-86) have revealed that ncRNAs mediate

PKM2-associated drug resistance through various mechanisms. For

example, miR-122 directly binds the 3′UTR of PKM2, inhibiting its

expression and reversing resistance to oxaliplatin, docetaxel and

doxorubicin by attenuating glycolysis (87-89). The glycolysis-related lncRNA SNHG3

promotes resistance to enzalutamide in prostate cancer via the

miR-139-5p/PKM2 axis (83). In

tumor cells, the ratio of PKM1 to PKM2 serves a critical role in

regulating both glycolysis and drug resistance. PKM1 and PKM2 are

isoforms generated by alternative splicing of PKM pre-mRNA, which

is regulated by the PKM gene. In cisplatin-resistant NSCLC cells,

the highly expressed lncRNA PCIF1 competes with miR-326, which can

directly interact with PKM to downregulate its expression. This

decreases the production of PKM2 by influencing PKM splicing.

Knockdown of lncRNA PCIF1 restores miR-326 expression, leading to

decreased glycolysis and PKM2 levels, which enhances cellular

sensitivity to cisplatin (84).

Additionally, RNA-binding proteins, such as Heterogeneous Nuclear

Ribonucleoprotein A1 (HNRNPA1), Polypyrimidine tract binding

protein 1 (PTBP1) and Sam68, serve critical roles in the specific

splicing of PKM (90). miR-326

also regulates PKM2 production by inhibiting HNRNPA1, HNRNPA2 and

PTBP1 (85). In hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC), miR-374b directly binds to HNRNPA1, reducing

selective splicing of PKM into PKM2 and increasing cellular

sensitivity to sorafenib (91).

In CRC, the lncRNA LINC01852l interacts with the RNA-binding

protein SR-like splicing factors5 (SRSF5), which promotes PKM

splicing to generate PKM2. Overexpression of LINC01852l leads to

upregulated PKM2 levels and increased glycolysis, thereby

contributing to resistance to 5-FU (86). Furthermore, in

doxorubicin-resistant BC, lncRNA TBX15 is downregulated. TBX15

serves as a sponge for miR-152, which targets Kinesin family member

2C (KIF2C) to inhibit PKM2-mediated glycolysis. KIF2C binds PKM2

and promotes the ubiquitination of PKM2 domain 2, enhancing PKM2

stability. The TBX15/miR-152 axis reverses doxorubicin resistance

in BC by targeting KIF2C and blocking cellular glycolysis and

autophagy (92). In ovarian

cancer (OC), the lncRNA CTSLP8 directly binds to PKM2, forming a

dimer. This PKM2-CTSLP8 dimer transcriptionally regulates c-Myc,

promoting glycolysis and cisplatin resistance in OC cells (93).

LDH, located in the cytoplasm, catalyzes the

conversion of pyruvate to lactic acid, the final product of

glycolysis. LDHA, a prominent isoform of LDH that is upregulated in

cancer, stimulates cellular lactate production, which contributes

to the acidic tumor microenvironment and enhances cancer cell

resistance to chemotherapy drugs (94). In various cancers, miRNAs such as

miR-34a, miR-101-3p and miR-329-3p target and inhibit LDHA,

suppressing lactate production and enhancing cancer cell

sensitivity to cisplatin. miR-34a and miR-101-3p are sponged by

upstream lncRNAs such as SNHG7 and XIST, respectively, leading to

their downregulation. Overexpression of these miRNAs can reverse

glycolytic metabolism and lactate-mediated cisplatin resistance

(95-97). In GC cells, the lncRNA HAGLR

sponges miR-338-3p to promote 5-FU resistance by targeting LDHA

(98). Similarly, in cervical

cancer (CC), knocking down lncRNA-NEAT1 restores miR-34a

expression, reversing LDHA-induced 5-FU resistance (99). Besides these ncRNAs that directly

bind to and inhibit LDHA expression, Shi et al (100) recently discovered that lncRNA

GLTC is overexpressed in thyroid cancer and negatively associated

with clinical prognosis. GLTC enhances LDHA succinylation at the

K155 site by disrupting the interaction between SIRT5 and LDHA.

This modification increases lactate content and the

NAD+/NADH ratio in papillary thyroid carcinoma cells,

promoting resistance to 131I therapy (100). c-Myc, a transcription factor

highly expressed in cancers, is closely linked to the tumor

microenvironment, metabolic reprogramming and the activation of

various oncogenic signaling pathways (101). c-Myc promotes glycolysis in

cancer cells by upregulating key enzymes of glycolytic metabolism.

Several ncRNAs have been shown to promote glycolysis and drug

resistance by stabilizing c-Myc mRNA. For example, circARHGAP12,

through m6A modification, binds c-Myc, promoting doxorubicin

resistance. Inhibition of circARHGAP29 decreases its interaction

with Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 mRNA-Binding Protein 1 (IGF2BP2),

enhancing c-Myc stability and increasing tumor cell sensitivity to

docetaxel. Similarly, miR-3679-5p stabilizes c-Myc by inhibiting

NEDD4-like E3 ubiquitin protein ligase (NEDD4L). Mechanistically,

c-Myc enhances the transcription of LDHA, promoting glycolysis, ATP

production and lactate generation in tumor cells, thereby mediating

cellular drug resistance (24,102,103).

PDH is an enzyme in the pyruvate dehydrogenase

complex (PDC), which catalyzes the irreversible decarboxylation of

pyruvate to acetyl-CoA in mitochondria. However, cancer cells

exhibit a preference for aerobic glycolysis rather than the

mitochondrial oxidation of pyruvate (104). miR-21-5p contributes to

cisplatin resistance in OC cells by targeting PDH E1 subunit α1

(PDHA1) (105). Additionally,

PDK1 regulates the activity of the PDC by inhibiting PDH (104). The upregulation of PDK1 inhibits

the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), leading to enhanced ATP

synthesis and decreased production of ROS under cellular hypoxic

conditions (106). Previous

studies have identified upstream regulators of PDK1, including

miR-148a and miR-4290, which suppress cellular glycolysis and

promote sensitivity to cisplatin and doxorubicin by inhibiting PDK1

expression (107,108). Overexpression of PDK1 can

reverse the effects of these miRNAs, promoting cell proliferation

and drug resistance (107,108). PTBP1 is a nuclear regulator of

alternative splicing. miR-134 and miR-506-3p directly bind to

PTBP1, reducing its expression and inhibiting glucose uptake and

lactate production in cells. The inhibition of miR-134 and

miR-506-3p induces resistance to doxorubicin and 5-FU, respectively

(25,109). PTBP1 can bind to the 3′ UTR of

LDHA, enhancing its stability. In aromatase inhibitor

(AI)-resistant BC cells, the lncRNA DIO3OS interacts with PTBP1 in

the nucleus, promoting BC cell proliferation and glycolysis

(110). Phosphoglycerate mutase

1 (PGAM1) is a key enzyme in glycolysis, catalyzing the conversion

of 2-phosphoglycerate to 3-phosphoglycerate (111). The m6A-modified circQSOX1

indirectly upregulates PGAM1 expression by sponging miR-326 and

miR-330-5p, thereby activating glycolysis in CRC cells. This

decreases the response of CRC to anti-CTLA-4 therapy and promotes

immune evasion in CRC (112).

Previous studies have highlighted the activation of

signaling pathways such as PI3K/AKT, MAPK and EGFR as key drivers

of glycolysis in cancer cells through the upregulation of

glycolysis-associated genes (113,114). For example, the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway can directly promote the phosphorylation of

glycolytic enzymes HK2 and PFKFB. Additionally, PI3K/AKT regulates

the expression of the transcription factor MYC, which further

enhances the expression of HK2, PFK-1, PDK1, PKM2 and LDHA

(115). In FMS-like tyrosine

kinase 3 (FLT3)-resistant acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells,

elevated expression of miR-155 activates the PI3K/AKT pathway by

directly binding to the 3′UTR of PIK3R1, a PI3K inhibitor. This

process enhances glycolysis, which is a key feature of resistance

to FLT3 tyrosine kinase inhibitors (116). By contrast, the inhibitory

effect of miR-149-3p on AKT1 decreases the expression of HK2, LDHA

and GLUT1 in AML cells, thereby enhancing the sensitivity of AML to

chemotherapy drugs (117).

EGFR stimulation can enhance the activation of HK2

and PKM2, thereby increasing lactate excretion to support the

acidic tumor microenvironment (118). This phenomenon may be associated

with the upregulation of HIF-1α and LDHA expression (119). Targeting EGFR has been shown to

improve glycolysis-mediated chemotherapy (120-122). Gao et al (120) found that EGFR positively

regulates lncRNA FGD5-AS1 expression in CRC. FGD5-AS1 indirectly

upregulates HK2 by sponging miR-330-3p, a negative regulator of

HK2. The EGFR-targeted inhibitor erlotinib suppresses HK2

expression and glycolysis in CRC, enhancing sensitivity to 5-FU

(119). miR-143 can target and

inhibit HK2, restoring sensitivity to cisplatin and 5-FU by

decreasing HK2-dependent glycolysis. Notably, EGFR negatively

regulates miR-143, and its downregulation in drug-resistant cancer

cells results in excess HK2 (121,122). Epiregulin (EREG) is an EGFR

ligand, which upregulates HK2, GLUT3 and PDK1 by activating EGFR

(123). miR-186-3p suppresses

the expression of EREG. However, tamoxifen decreases miR-186-3p

levels in ER-positive BC cells. The miR-186-3p/EREG axis activates

EGFR signaling, promoting glycolysis and mediating tamoxifen

resistance in BC cells (124).

The interaction between ncRNAs and the MAPK signal

transduction pathways plays a key role in tumor cell proliferation,

survival and metabolic reprogramming (125). ERK1/2 serves as the downstream

and final effector of the MAPK pathway (125) and promotes glycolysis by

facilitating the nuclear translocation of PKM2 or upregulating

HIF-1α (126,127). In apatinib-resistant GC cells,

both LINC00665 and ERK2 are upregulated. LINC00665 enhances ERK2

expression by sequestering miR-665, which stimulates the expression

of GLUT1, LDHB and HK2, thereby promoting glycolysis and inducing

apatinib resistance (128).

In summary, ncRNAs target key glycolytic enzymes and

associated signaling pathways (Fig.

2; Table II). These crucial

glycolytic enzymes not only facilitate glycolysis in cancer cells

but also activate downstream signaling pathways associated with

drug resistance (Fig. 3). While

some studies suggest ncRNAs contribute to chemotherapy resistance

through glycolysis enhancement (135,136), the precise mechanisms by which

downstream targets promote glycolysis remain unclear, with only

phenotypical changes in glycolysis observed.

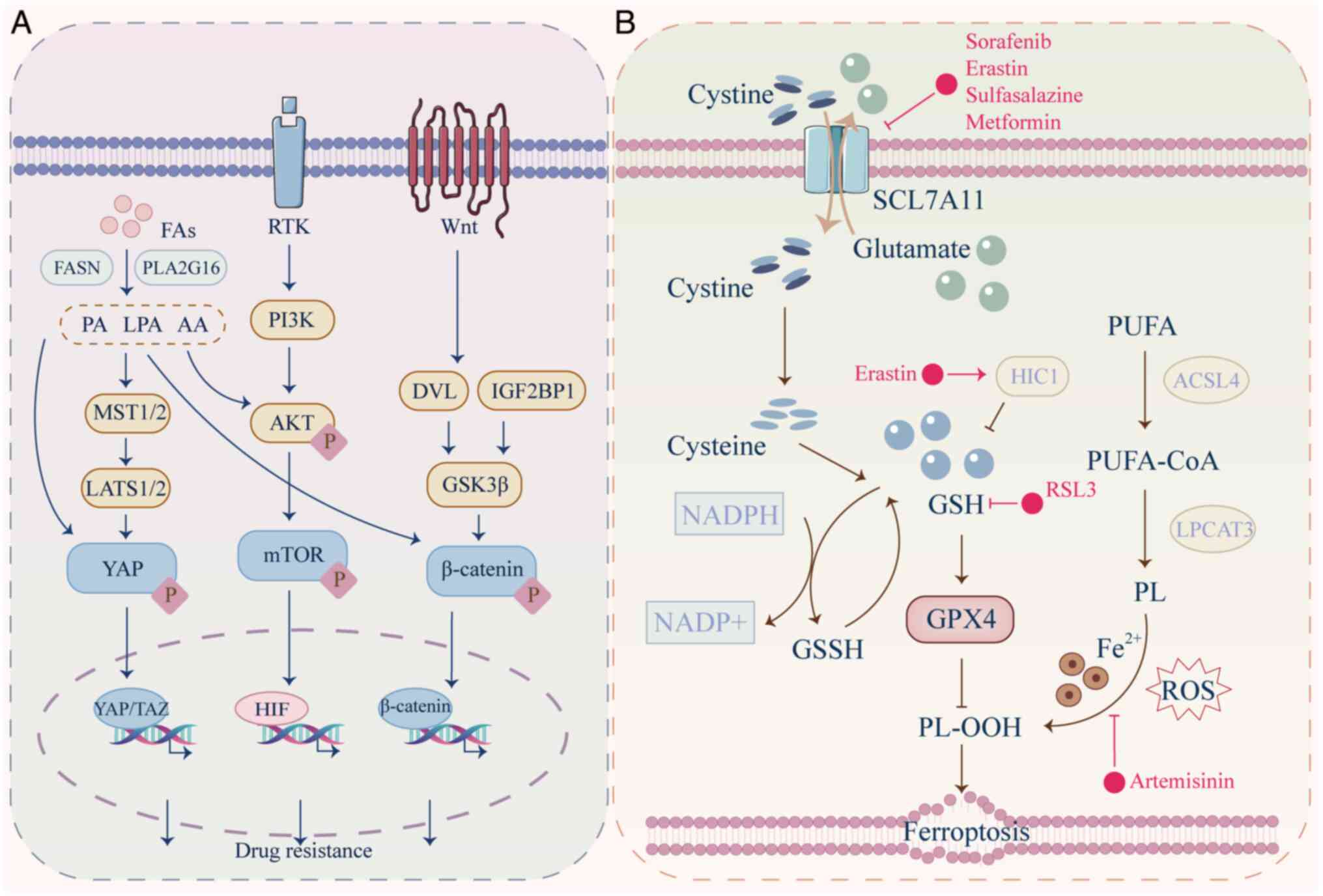

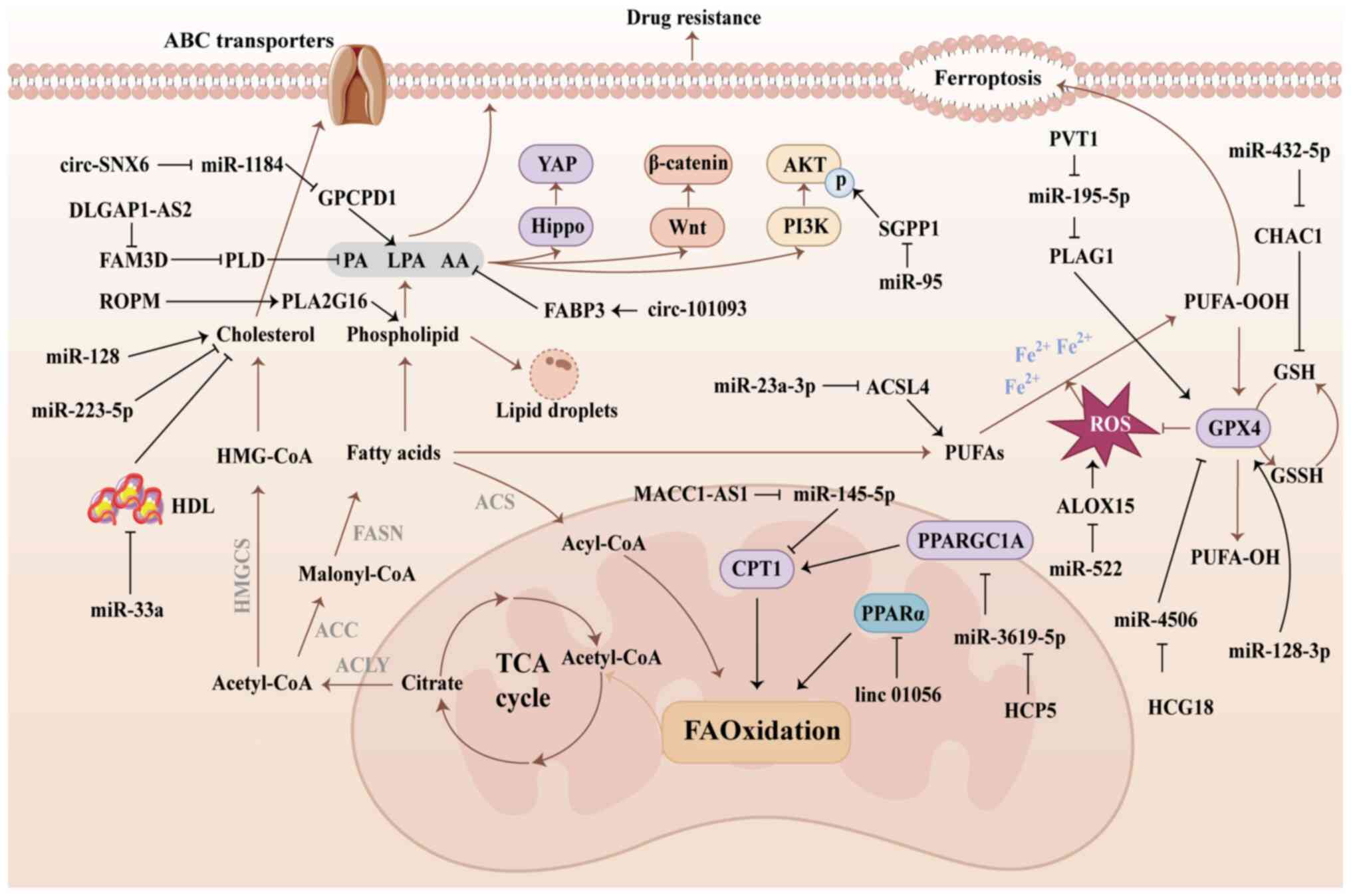

By contrast with normal cells, tumor cells require

dysregulated lipid metabolism to support proliferation, metastasis,

membrane synthesis and signaling (137). Fatty acids (FAs) accumulate in

tumor cells through both direct external uptake and de novo

synthesis (138). These

up-regulated FAs participate in lipid synthesis, leading to the

production of phospholipids, cholesterol and other lipid

metabolites, thereby fueling processes such as FA oxidation (FAO)

(138). This provides essential

ATP, lipid products and signaling molecules for tumor cell

proliferation, metastasis and drug resistance.

In drug-resistant cancer cells, the uptake and

synthesis of FAs are notably enhanced. This leads to the

accumulation of cholesterol and lipid droplets within the cells,

which decreases ROS levels and promote stemness, thereby

contributing to drug resistance (138). Furthermore, FAs and synthesized

lipid products regulate the activation of the PI3K/AKT,

Wnt/β-catenin and Hippo/YAP signaling pathways, thereby promoting

survival and drug resistance in cancer cells (Fig. 4A) (139-141).

As numerous chemotherapeutic agents require cellular

entry to target DNA and induce cell death, lipid metabolism also

mitigate toxic effects by altering drug uptake in cancer cells

(142). Drugs typically enter

cells through non-specific lipophilic interactions with the cell

membrane. Abnormal lipid metabolism alters the membrane

composition, decreasing its permeability to anti-cancer drugs

(143). Although the exact

changes in membrane composition are not fully understood, the low

permeability of certain drugs is associated with poor membrane

fluidity (144). Additionally,

lipid metabolism affects the expression of transporters on the cell

membrane. Free FAs activate the G protein-coupled receptor GPR120,

which in turn upregulates ABC transporter expression via the

AKT/NF-κB signaling pathway, leading to decreased epirubicin

accumulation in BC cells (145).

By contrast, long-chain PUFAs decrease multidrug resistance 1 gene

(MDR1) expression on the cell membrane, thereby decreasing PTX

efflux and enhancing the chemotherapy sensitivity of tumor cells

(146). Furthermore, lipid

metabolism promotes adipocyte-like transformation in cancer cells,

leading to the production of lipid droplets, which act as storage

sites for fat-soluble drugs. This results in diminished

concentrations of chemotherapeutic agents reaching intracellular

targets (147).

Cholesterol serves a pivotal role in cell membrane

protein function, receptor transport, proliferation, membrane

biogenesis and signal transduction. Increased cholesterol synthesis

is associated with poorer survival rates and cancer progression

(152). High cholesterol levels

are observed in BC cells, where miR-128 and miR-223 regulate

cholesterol metabolism by targeting genes such as

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA Synthase 1 (HMGCS1), Low-density

lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and ATP-Binding Cassette Transporter A1

(ABCA1), modulating cholesterol biosynthesis, uptake and efflux.

Cholesterol accumulation enhances lipid raft formation and membrane

rigidity, decreasing membrane permeability and contributing to drug

resistance. These miRNAs indirectly influence cell sensitivity to

tamoxifen via the regulation of cholesterol (153). Additionally, miR-33a mitigates

drug resistance in BC by inhibiting high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

expression and preventing HDL-mediated cholesterol extraction

(154).

FAs that accumulate in cancer cells are converted

into fatty acyl-CoA through the action of acyl-CoA synthetase

(ACS). Acyl-CoA is transported to the mitochondrial matrix, where

it undergoes β-oxidation to generate acetyl-CoA and ATP (43). Long-term exposure of cancer cells

to elevated ROS levels induced by chemotherapy may enhance

resistance to further treatment. This phenomenon is due to the

activation of several factors, including Nrf2, c-Jun and HIF-1α,

which enhance the antioxidant capacity of cancer cells (155). To neutralize ROS, tumor cells

produce large amounts of antioxidants such as GSH, which is reduced

from its oxidized form via NADPH (156). Elevated ROS levels can promote

FAO, enabling cancer cells to generate sufficient NADPH and reduced

GSH (157). Increased FAO has

been observed in drug-resistant GC and AML (158,159). This increase not only meets the

energy demands of tumor cells but also supports their survival in

oxidative stress environments (160). Inhibition of FAO reduces NADPH

and GSH production in tumor cells while simultaneously increasing

ROS production (161). In

addition, cancer cells counteract ferroptosis by enhancing FAO and

phospholipid synthesis, which elevates the levels of saturated FAs

and restores GSH levels, thereby improving resistance to ROS

(162).

In sorafenib-resistant HCC cells, the lncRNA

LINC01056 is notably downregulated and inversely associated with

sorafenib resistance. Mechanistically, LINC01056 binds specifically

to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α (PPARα), inhibiting

its nuclear translocation and transcriptional activity, thus

decreasing the expression of FAO-related genes. Overexpression of

LINC01056 suppresses PPARα, attenuating FAO in HCC cells and

restoring their sensitivity to sorafenib in vitro (163). Previous studies (26,164) have highlighted the key role of

mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in mediating drug resistance in GC

cells. MSCs stimulate the expression of lncRNA MACC1-AS1 in GC

through TGF-β secretion. As a sponge for miR-145-5p, MACC1-AS1

enhances the expression of FAO-associated metabolic enzymes such as

octamer-binding transcription factor 4 and carnitine

palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1), thereby promoting FAO in GC cells

and contributing to resistance to the 5-FU+leucovorin + oxaliplatin

(FOLFOX) regimen (26).

Furthermore, exosomes derived from MSCs elevate the expression of

lncRNA HCP5 in GC cells, which specifically inhibits miR-3619-5p.

By preventing miR-3619-5p from binding PPARG coactivator 1α, HCP5

enhances the transcriptional complex of PPARγ coactivator

1-α/CEBPB, leading to the induction of CPT1 transcription. This

process promotes stemness and chemoresistance in GC cancer cells by

driving FAO (164).

Ferroptosis is a form of programmed cell death

characterized by the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products

that serves a key role in cancer occurrence, treatment resistance

and tumor suppression (165).

Polyunsaturated FAs (PUFAs) are catalyzed by acyl-CoA synthetase

long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine

acyltransferases to produce phospholipids (PLs). Catalyzed by

lipoxygenase and P450 oxidoreductase, PL interacts with ROS and

iron ions to form PL hydroperoxides (PLOOH). The significant

production of PLOOH results in the instability and increased

permeability of cell membranes, leading to cell death (166). The occurrence of ferroptosis is

influenced by two pathways. The crucial pathway is the inactivation

of GSH peroxidase 4 (GPX4). GPX4 serves a pivotal role in the

reduction of PLOOH through the utilization of GSH. The other

pathway involves inhibition of the cystine/glutamate antiporter

system (xCT), mediated by solute carrier family 7A member 11

(SLC7A11). SLC7A11 facilitates the uptake of cysteine, which is key

for the synthesis of GSH, a prerequisite for the functional

activity of GPX4 (167).

Ferroptosis is induced by anti-tumor drugs that

suppress GPX4 or promote lipid peroxidation, as summarized by Li

et al (168). For

example, the combined treatment of albumin-bound paclitaxel and TMZ

enhances ferroptosis in glioblastoma by inhibiting GPX4 expression

(169). Sorafenib induces lipid

peroxidation in HCC by inhibiting solute carrier family 3A member 2

(SLC3A2) and SLC7A11, thereby suppressing GSH production and GPX4

expression, which upregulates ferroptosis in HCC cells (170). However, in drug-resistant tumor

cells, numerous types of lipid metabolic enzyme and endogenous

antioxidant mitigate the occurrence of ferroptosis by decreasing

lipid peroxidation (171). The

SLC7A11-GPX4 system is dysregulated in numerous types of

drug-resistant cancer, contributing to resistance against

oxaliplatin (172).

HER2-positive BC cells activate the β-catenin signaling pathway via

fibroblast growth factor receptor 4, leading to an increased

synthesis of GSH via the transcription factor 4/SLC7A11 axis

(173). Nrf2 is also implicated

in cancer drug resistance and ferroptosis. Excessive ROS inactivate

Keap1 via oxidation of its cysteine residues, releasing the

transcription factor Nrf2 into the nucleus, where it activates the

transcription of antioxidant genes, such as GPX4 (174). Furthermore, the activation of

Nrf2 induces Metallothionein-1G, which reduces GSH depletion and

lipid peroxidation, thereby inhibiting sorafenib-induced

ferroptosis (175).

The lncRNA PVT1 enhances pleiomorphic adenoma gene

1 (PLAG1) expression at the transcriptional level by targeting

miR-195-5p. PLAG1 interacts with GPX4, facilitating its role in

stabilizing lipid peroxidation and protecting HCC cells from

sorafenib-induced ferroptosis (187). Both miR-128-3p and miR-450b-5p

promote ferroptosis and lipid peroxidation by inhibiting the

enzymatic activity of GSH and GPX4 (188,189). Additionally, sorafenib

upregulates miR-23a-3p expression in HCC via ETS proto-oncogene 1

induction, which targets ACSL4. Sorafenib-mediated overexpression

of miR-23a-3p decreases lipid peroxidation and ferroptosis in HCC

cells by inhibiting ACSL4, thereby contributing to HCC cell

resistance to sorafenib (170).

Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete miR-522 and miR-432-5p to

inhibit lipoxygenase15 (ALOX15) and cyclotransferase1 (CHAC1).

ALOX15 degrades ROS generated by lipid peroxidation, whereas CHAC1

enhances the production of GSH, thus inducing drug resistance

(190,191).

In summary, ncRNAs modulate the sensitivity of

tumor cells to drugs by influencing lipid metabolism (Fig. 5; Table III). These mechanisms involve

lipid synthesis, FAO and the regulation of ferroptosis. While most

of the aforementioned studies have focused on how ncRNAs affect

lipid oxidation balance within cancer cells, future investigations

should explore how ncRNA-mediated lipid metabolism alters cell

membrane components and intracellular lipid droplets to promote

drug resistance.

Mitochondria are key in metabolic reprogramming,

supporting the catabolism of amino acids, nucleotides and lipids,

as well as the production of NADH and NADPH (192). In tumor cells, mitochondrial DNA

(mtDNA) mutations or alterations in content lead to mitochondrial

dysfunction. For example, the deletion of mtDNA in PC cells results

in mitochondrial dysfunction, driving a shift to the Warburg effect

and promoting stem cell-like characteristics. This reprogramming

helps the cells resist docetaxel treatment (193). In HCC, mtDNA loss contributes to

chemotherapy resistance by activating the NRF-2 signaling pathway

and upregulating multidrug resistance genes such as MDR1 and MRP1/2

(194). Further evidence from

colon cancer cells with mtDNA deletions supports the involvement of

MDR1 in resistance mechanisms (195). On the contrary,

chemotherapy-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer cells is

often accompanied by mutations in mtDNA, which increase ROS

production (196).

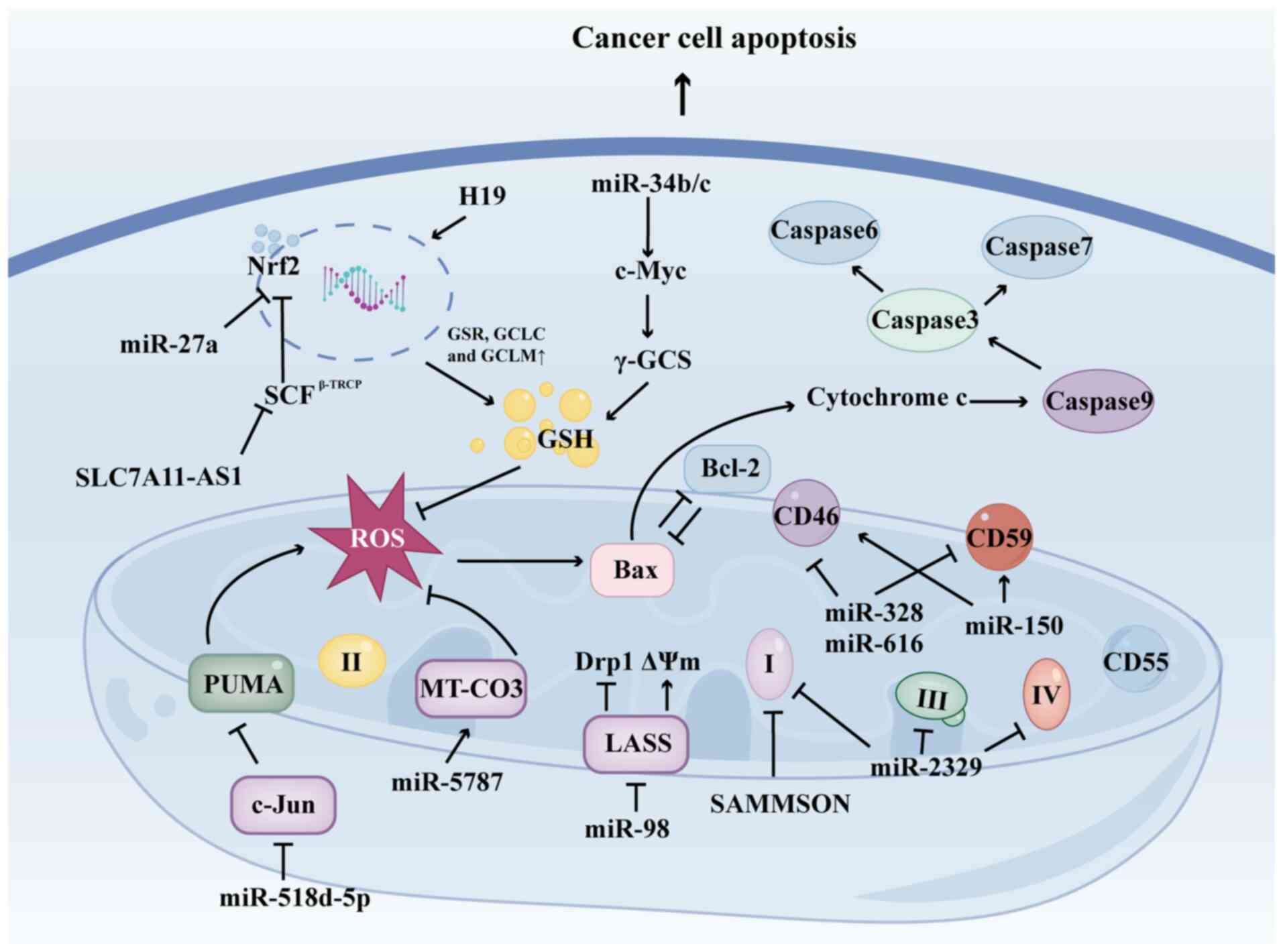

Resistance to apoptosis is a key mechanism

underlying drug resistance in cancer. Under physiological and

pathological conditions, cells maintain a balance in redox

homeostasis. However, certain chemotherapeutic agents, such as

5-FU, epirubicin and gemcitabine, induce oxidative stress by

inhibiting the antioxidant system or mitochondrial function,

leading to excessive production of ROS (197). Elevated ROS levels disrupt

mitochondrial membrane potential, resulting in the release of

cytochrome c and activation of caspases-3, -6 and -7, thereby

triggering apoptosis in cancer cells (198). Additionally, tumors often

release excess ROS into the microenvironment, which can induce

macrophages to adopt a pro-cancer phenotype (199). This phenotype reduces T cell

infiltration into tumors and decreases the expression of programmed

death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), thereby hindering the effectiveness of

anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy (200).

The dysregulation of apoptosis is a key factor in cancer resistance

to chemotherapy.

Dysregulated ncRNAs within mitochondria modulate

the activation of mitochondrial-mediated signaling pathways,

promoting tumor growth and drug resistance. miR-125b is associated

with increased release of mitochondrial cytochrome c, the induction

of apoptotic protease activating factor 1 and the activation of

caspase-3 and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (201). Furthermore, the overexpression

of miR-125b can inhibit the expression of BCL-2 while

simultaneously increasing the expression of Bax (201).

Chemotherapy agents, including cisplatin,

doxorubicin and PTX, are known pro-oxidants that induce cell death

through mitochondrial dysfunction and increased ROS production

(202). This has intensified

interest in the role of ncRNAs in modulating ROS generation within

mitochondria (203,204). Sorafenib, for example, induces

mitochondrial dysfunction and ROS production via the

C-Jun/p53-upregulated modulator of apoptosis signaling pathway,

while miR-518d-5p impedes this process by targeting and inhibiting

C-Jun, resulting in sorafenib resistance (205). Mitochondrial miRNA

(mitomiRNA)-2329 is significantly upregulated in

cisplatin-resistant cells. It inhibits the activity of

mitochondrial complexes I, III and IV, leading to elevated

mitochondrial ROS and decreased ATP production. Additionally,

mitomiR-2329 partially regulates mtDNA transcription in an

Argonaute2 (AGO2)-dependent manner, promoting glycolysis and

lactate production (206).

Similarly, the lncRNA SAMMSON increases ROS production in BC cells

by inhibiting mitochondrial complex I (207). These findings underscore the key

role of ncRNAs targeting mitochondrial complexes in regulating

mitochondrial function. Furthermore, Hillman et al (208) demonstrated that miR-150, miR-328

and miR-616 target membrane complement regulatory factors CD46,

CD55 and CD59, thereby rendering mitochondria resistant to

complement lysis and enhancing cellular tolerance to

complement-dependent cytotoxicity. miR-98 regulates mitochondrial

fusion and fission by directly targeting Longevity Assurance

Homologue 2, promoting mitochondrial fission and increasing

mitochondrial membrane potential, which contributes to resistance

to cisplatin and doxorubicin (209). Notably, mitomiR-5787 inhibits

oxidative stress and glycolysis in mitochondria by binding

mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit 3 (MT-CO3), restoring

cisplatin sensitivity (205).

Conversely, the binding of mitomiR-5787 to MT-CO3 does not suppress

MT-CO3 expression but enhances its translation. This may be due to

the absence of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC)-associated

factor GW182, which is responsible for mRNA cleavage, within

mitochondria (210).

ncRNAs serve a key role in mitigating intracellular

ROS and oxidative stress by promoting the production of GSH. For

example, in prostate cancer, miR-34b/c facilitates the generation

of GSH and Bcl-2 via the c-Myc/γ-glutamyl-cysteine synthetase axis,

which decreases the cytotoxic effects of oxidative stress and

enhances cellular tolerance to ROS (211). lncRNA H19 is overexpressed in

cisplatin-resistant high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSC), and

its overexpression enhances cisplatin resistance. H19 upregulates

Nrf2 expression, promoting the transcription of GSH-associated

proteins such as Glutathione reductase (GSR), Glutamate-cysteine

ligase catalytic subunit (GCLC) and Glutamate-cysteine ligase

modifier subunit (GCLM), which increases intracellular GSH

accumulation (212). Conversely,

miR-27a targets GSH-associated genes such as cystathionine

gamma-lyase, xCT and Nrf2, reducing cellular resistance to ROS and

increasing sensitivity to chemotherapy (213). Moreover, Nrf2 is regulated by

its upstream regulatory factor SKP1-Cul1-Rbx1

(SCFβ−TRCP). SLC7A11-AS1 blocks

SCFβ−TRCP-mediated Nrf2 ubiquitination, resulting in low

intracellular ROS levels (214).

In conclusion, ncRNAs regulate mitochondrial

complexes, apoptosis-related proteins and other factors, playing a

key role in mediating mitochondrial dysfunction in cancer cells.

Targeting ncRNAs can modify the ROS/GSH balance within

mitochondria, diminishing the tolerance of cancer cells to

drug-induced ROS (Fig. 6,

Table IV).

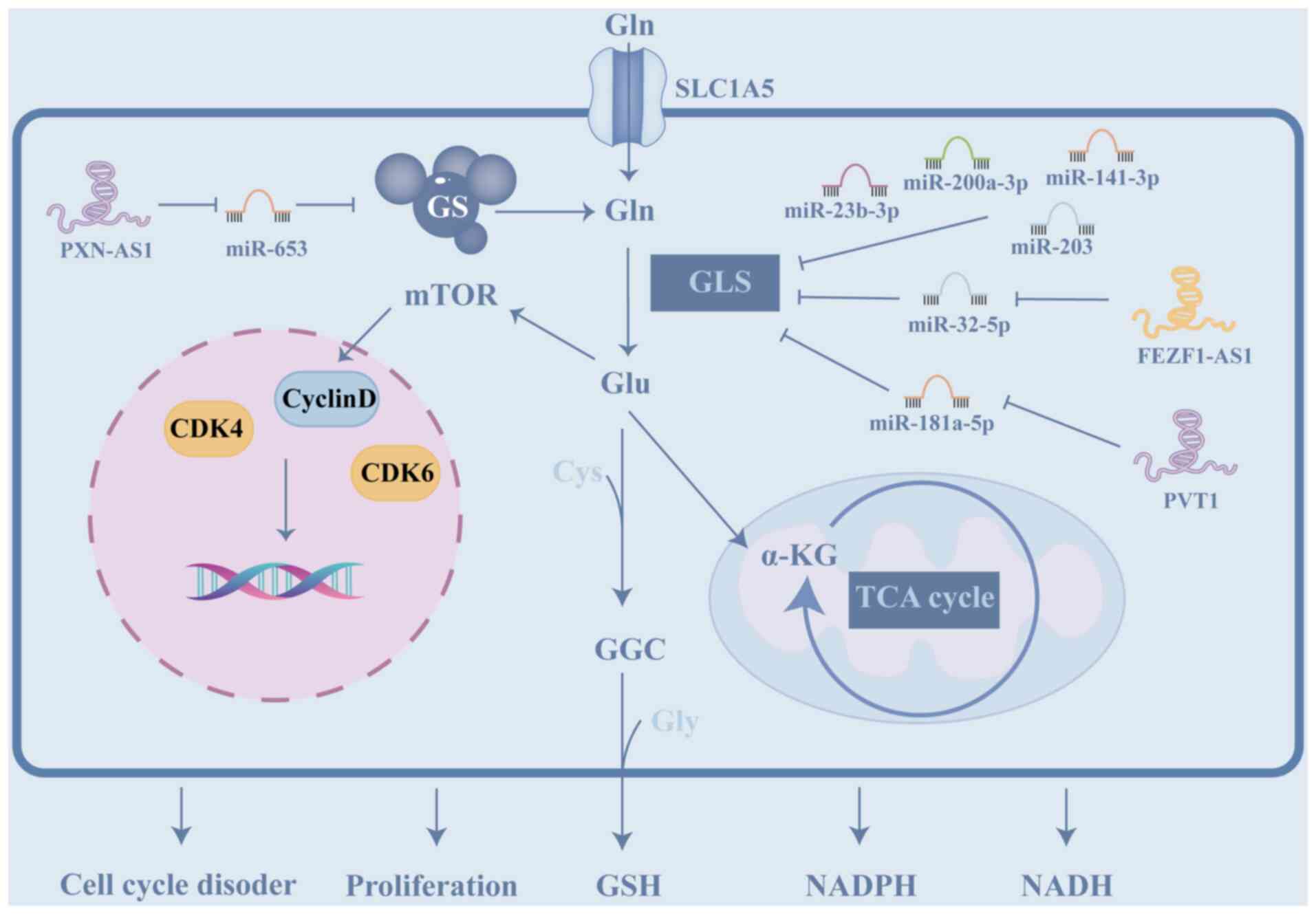

Glutamine (Gln), a non-essential amino acid, serves

a key role in cancer initiation and progression. Cancer cells

depend on glutamine for its involvement in the TCA, as well as for

the biosynthesis of nucleotides, GSH and other non-essential amino

acids, thus providing essential nutrients for cancer drug

resistance (10). Numerous

studies (215-220) have demonstrated that ncRNAs

regulate GSH metabolism in cancer cells primarily by targeting

glutaminase (GLS), a mitochondrial enzyme responsible for

catalyzing the deamidation of glutamine (Fig. 7; Table V). GLS is a key player in cancer

drug resistance, tumor growth and metastasis (221). In cancers such as HCC and NSCLC,

numerous miRNAs have been identified as tumor suppressors that

inhibit glutamine metabolism by targeting the 3′UTR of GLS

(215-218). Overexpression of these miRNAs,

which suppress GLS, enhances cancer cell sensitivity to drugs and

promotes apoptosis (214).

lncRNAs, such as PVT1 and FEZF1-AS1, restore GLS expression by

serving as sponges for miR-181a-5p and miR-32-5p, respectively,

which target GLS, thereby promoting cell resistance to cisplatin

(219,220). These findings highlight the key

role of the ncRNA network in regulating GLS expression and

contributing to cellular drug resistance. Additionally, in

imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia cells, lncRNA

PXN-AS1 indirectly upregulates glutamine synthetase by modulating

miR-653, promoting glutamine synthesis. Increased glutamine

activates the mTOR signaling pathway, leading to elevated

expression of CDK4, Cyclin D and CDK6 in the nucleus, thus

promoting cell proliferation and cell cycle dysregulation (222).

NSCLC is characterized by a strong dependence on

aerobic glycolysis, with elevated expression of glycolytic enzymes

such as GLUT1 and PKM2, which promote rapid proliferation and

confer resistance to targeted therapy, such as Osimertinib

(64,84). In NSCLC, circRNA-0002130 has been

shown to promote glycolysis and osimertinib resistance by serving

as a sponge for miR-498, leading to the upregulation of GLUT1 and

enhanced glucose uptake (64).

Similarly, miR-326 directly targets HNRNPA1, a key regulator of PKM

splicing, to suppress PKM2 expression and reverse cisplatin

resistance (84). Additionally,

lncRNA PCIF1 competitively binds miR-326, promoting PKM2 expression

and glycolysis, thereby enhancing cisplatin resistance (84). Other ncRNAs, such as miR-200a-3p,

target GLS to suppress glutamine metabolism. Concurrently

inhibiting miR-200a-3p may represent an effective strategy to

prevent the compensatory increase of glutamine in cancer cells

(214). Therapeutic strategies

targeting these axes, such as silencing circRNA-0002130 or

restoring miR-326, may sensitize NSCLC cells to chemotherapy.

CRC cells also exhibit enhanced glycolysis, which

supports stemness and drug resistance (78). In CRC, circ-SAMD4A drives

glycolysis and 5-FU resistance by sponging miR-545-3p, leading to

the upregulation of PFKFB3 and enhanced glycolytic flux (78). miR-488 also directly targets

PFKFB3 (77). Furthermore, lncRNA

LINC01852 promotes PKM2 splicing via SRSF5, enhancing glycolysis

and 5-FU resistance (86).

miR-143 inhibits HK2, reversing 5-FU resistance by suppressing

glycolysis (122). Inhibiting

glycolysis-related ncRNAs, such as circ-SAMD4A or miR-143, may

disrupt energy supply and stemness, thereby overcoming

chemoresistance.

HCC cells exploit abnormal lipid metabolism and

resistance to ferroptosis, a key mechanism of sorafenib-induced

cell death (170,187). In HCC, miR-23a-3p is upregulated

by sorafenib and suppresses ACSL4, a key enzyme in lipid

peroxidation, thereby inhibiting ferroptosis (170). lncRNA PVT1 promotes PLAG1

expression by sponging miR-195-5p, enhancing GPX4 activity

(187), while miR-128-3p

directly inhibits GPX4, promoting ferroptosis and overcoming

sorafenib resistance (188).

Additionally, LINC01056 inhibits PPARα, suppressing FAO and

restoring sorafenib sensitivity (163). Other ncRNAs, such as miR-374b,

target HNRNPA1 to reduce PKM2 expression and sensitize HCC cells to

sorafenib (91). Restoring lipid

peroxidation, for example by inhibiting miR-23a-3p or PVT1, may

enhance sorafenib efficacy in patients with HCC.

OC cells exhibit enhanced glycolysis and

antioxidant capacity, which contribute to cisplatin resistance

(93,210). In OC, lncRNA CTSLP8 binds to

PKM2, forming a dimer that transcriptionally activates c-Myc,

driving glycolysis and cisplatin resistance (93). Another key player, lncRNA H19,

upregulates Nrf2, enhancing GSH synthesis and oxidative stress

resistance (210). Additionally,

miR-21-5p targets PDHA1, suppressing mitochondrial metabolism and

promoting cisplatin resistance (105). Targeting CTSLP8 or H19 may

disrupt glycolysis and redox balance, sensitizing OC cells to

platinum-based therapy.

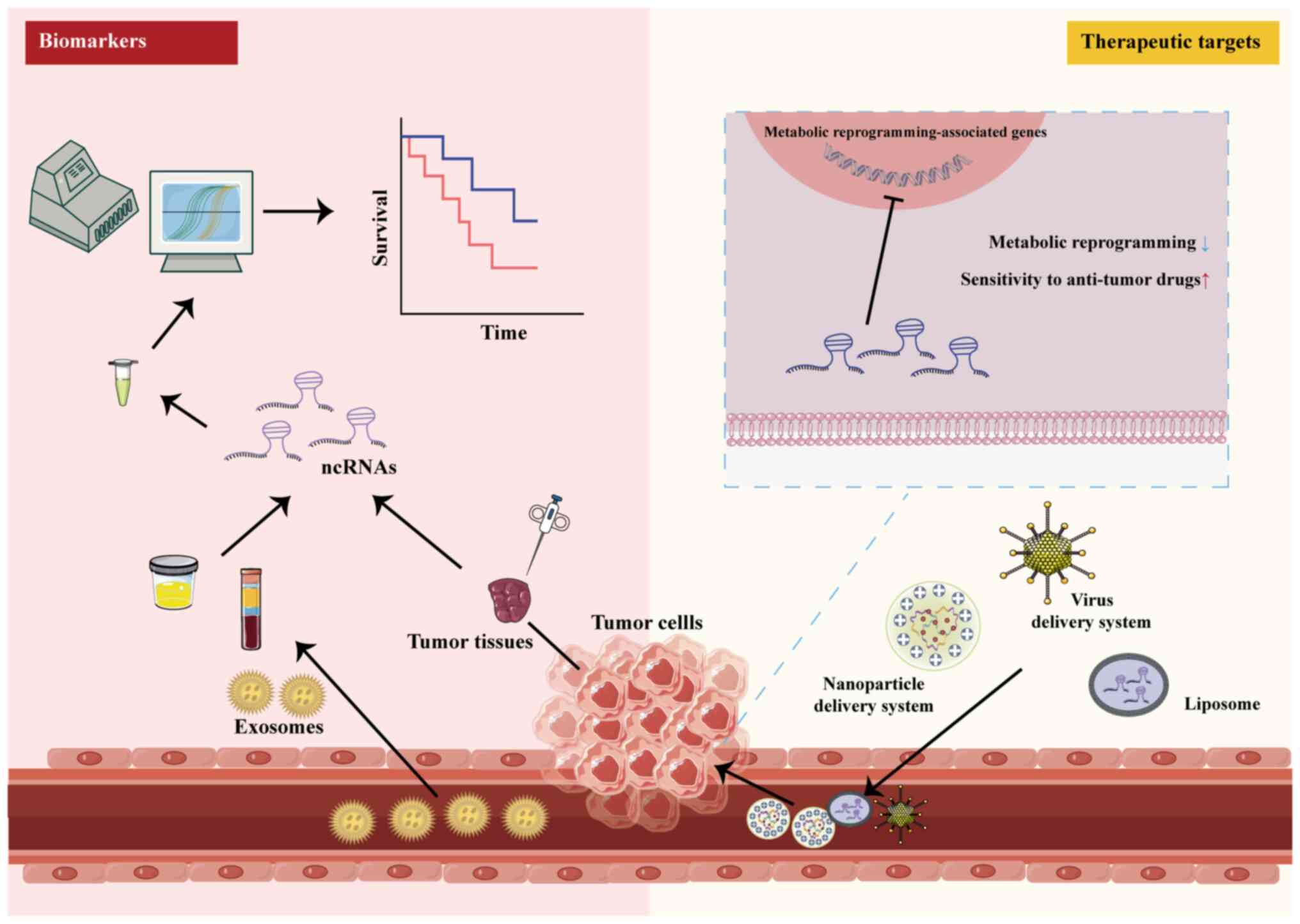

Early detection, diagnosis and treatment are

critical for improving cancer prognosis. However, many patients

with cancer experience disease progression due to drug resistance,

which delays treatment opportunities. ncRNAs, particularly

circulating miRNAs, are found in bodily fluids such as blood, urine

and saliva and exhibit high stability when stored under appropriate

conditions (223). These ncRNAs

are specifically expressed in cancer cells and enter bodily fluids

after binding proteins or being encapsulated by exosomes, making

them potential biomarkers for cancer (Fig. 8) (224). Numerous studies have

demonstrated that ncRNAs can predict patient responses to treatment

(67,93,225). For example, the upregulation of

circ-0002130 in serum exosomes from patients with

osimertinib-resistant NSCLC can predict sensitivity to osimertinib

(67). In OC, patients with high

CTSLP8 expression have notably reduced overall survival (93). Liu et al (225) used changes in the levels of

eight lncRNAs to predict the response of patients with HGSC to

platinum-based chemotherapy.

Additionally, ncRNAs reflect the association

between drug resistance and metabolic changes in cancer cells

(226). AIs, the first-line

endocrine therapy for postmenopausal patients with ER+

BC, have resistance closely linked to glycolysis (225). High baseline expression of

miR-155 is associated with increased glycolysis and poor response

to AI treatment (227). Changes

in the expression of lncRNAs associated with cholesterol and

sphingolipids predict the prognosis of HCC and pancreatic cancer

and assess their sensitivity to immunotherapy (228,229). A study used 11 lncRNAs

associated with FA metabolism to construct a risk prediction model

for skin melanoma, aimed at predicting melanoma sensitivity to

immunotherapy (230). Ongoing

research efforts are being made to establish ncRNAs as biomarkers

of tumor drug resistance (231-233). For example, a clinical trial

involving 144 patients with BC found that lncRNA MEG3 is associated

with the response and toxicity of PTX and cisplatin chemotherapy

(231).

The regulation of metabolism in combination with

anti-tumor therapy is a promising strategy to overcome tumor drug

resistance (234). Numerous

studies have demonstrated that blocking key metabolic pathways in

cancer cells contributes to the eradication of recurrent or

drug-resistant cancer cells (234,235). However, non-cancerous and immune

cells exhibit metabolic fragility; targeting the intrinsic

metabolism of cancer cells can also affect these essential cells,

leading to severe adverse reactions (12). The advantage of targeting ncRNAs

to regulate metabolism is the specific abnormal expression of these

ncRNAs in cancer cells. This specificity allows more targeted

ncRNA-based therapy. miRNAs promoting glycolysis are notably

elevated in drug-resistant cancer cells. When anti-miR drugs are

delivered to these cells, specific miRNAs are notably inhibited

(236). Although these miRNAs

are inhibited in normal cells as well, the impact on normal cells,

where these miRNAs are expressed at low levels, is smaller compared

with that on cancer cells. Furthermore, certain ncRNAs bind to

multiple sites simultaneously. For example, miR-498 binds GLUT1,

HK2 and LDHA to inhibit cellular glycolysis (64). In mitochondria, miR-634 binds to

multiple sites, including optic atrophy 1, lysosomal-associated

membrane 2 gene and Nrf2, thereby regulating mitochondrial

homeostasis, autophagy and the production of apoptosis-related

proteins (237).

The inherent instability of ncRNAs in the body

makes them highly susceptible to degradation by RNases, which

presents a notable challenge for therapeutic application. To

overcome this, the development of effective delivery systems that

ensure targeting specificity, decrease immunogenicity and maintain

the stability of ncRNAs is crucial (242). Various approaches have been

explored to address these challenges. Lin et al (243) developed a pH- and GSH-sensitive

nanocarrier for the co-delivery of docetaxel and the miR-34

activator rubbone (RUB). This carrier demonstrates good stability

in vitro, targets cancer cells efficiently and rapidly

releases docetaxel and RUB into the cytoplasm, enhancing the

sensitivity of tumor cells to docetaxel (243). Another study (244) designed GSH-sensitive

nanoparticles. These nanoparticles lead to micellar degradation and

facilitating drug release by reducing GSH to sulfhydryl groups.

This strategy is used for the targeted delivery of GEM and miR-519c

to pancreatic cancer tissue with elevated GSH levels, improving GEM

resistance. Additionally, miR-519c decreases glycolysis and

angiogenesis by inhibiting HIF-1α (244). In melanoma, Guo et al

(245) employed liposomes

containing miR-21-3p to regulate lipid metabolism. The

nanoparticles deliver miR-21-3p into melanoma cells, promoting

lipid peroxidation and lipid ROS production by inhibiting TXNRD1,

which enhances the response of melanoma cells to immunotherapy

(245). Similarly, lipid-coated

calcium carbonate nanoparticles are used to deliver 5-FU and

miR-375-3p to tumor cells in a weakly acidic environment (246). miR-375-3p interferes with

thymidylate metabolism by targeting thymidylate synthase, enhancing

the chemotherapy effect of 5-FU (246). Targeting mitochondrial

dysfunction in cancer, nanoparticles modified with

mitochondria-targeting peptides and tumor-targeting ligands

efficiently deliver miR-125 to mitochondria within cancer cells.

This approach regulates mitochondrial dynamics-associated proteins

and suppresses intracellular ATP production (247). Bioengineered miRNAs targeting

metabolic pathways have shown promise in cancer therapy (248,249). For example, the bioengineered

tRNA/miR-328-3p enables controlled release of miR-328-3p in human

osteosarcoma cells, inhibiting glycolysis and cell proliferation by

targeting GLUT1 (249).

Exosomes serve a key role in intercellular

communication and can be easily engineered with tumor-targeting

properties through molecular biology techniques, making them a

promising vehicle for ncRNA delivery (250). For example, exosomes targeting

HER2 have been used to deliver oncomiR-21 inhibitors to CRC cells,

successfully reversing 5-FU resistance in these cells (251). However, current research is

mainly focused on encapsulating both antitumor drugs and ncRNAs

within nanoparticles for synergistic antitumor effects (252), while the use of exosomes for

concurrent delivery of drugs and ncRNAs remains underexplored.

Stability issues surrounding dual delivery via exosomes need to be

addressed in future studies. In addition to nanoparticle-based

approaches, inhibition of miRNAs using antisense DNA oligomers that

incorporate locked nucleic acids (LNAs) offers a promising strategy

for gene therapy. A clinical trial investigated a 13-mer LNA

inhibitor targeting miR-221 (LNA-i-miR-221) and found that, among

17 patients treated with this therapy, 16 demonstrated good

tolerance, with eight achieving stable disease and one experiencing

partial response (253).

Furthermore, gene delivery systems based on viral vectors and

clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat-associated

protein9 (Cas9) genome editing system have been explored for

editing ncRNAs to hinder tumor progression (254).

In summary, ncRNAs exhibit specificity in targeting

key pathways in tumor cell metabolism, serving a pivotal role in

tumor growth and drug resistance. As such, ncRNAs represent

valuable targets for metabolic regulation in treating

drug-resistant cancer. Interfering with ncRNAs in tumor cells via

targeted delivery systems, such as nanoparticles, can effectively

modulate tumor metabolism and enhance the efficacy of anti-cancer

therapy (Fig. 8).

The aforementioned studies underscored the

importance of ncRNA-mediated metabolic regulation in combating drug

resistance, yet limitations persist. Studies (97,189,205,213) often focus on individual ncRNAs

in specific cancer models, neglecting the tissue-specific and

context-dependent roles of ncRNAs and rarely account for

spatiotemporal variations, which are key for predicting therapeutic

outcomes. For example, miR-181a exhibits oncogenic properties in GC

(255) but acts as a tumor

suppressor in NSCLC (256).

These fragmented views impede the identification of the complex

ncRNA regulatory network in cancer. Metabolic reprogramming

involves interconnected pathways, such as glycolysis, lipid and

glutamine metabolism. yet most studies (66,215) investigate ncRNAs targeting a

single pathway, which may trigger compensatory mechanisms. For

example, inhibition of glycolysis can enhance glutamine dependency

(257).

The regulatory mechanisms by which ncRNA influences

metabolic reprogramming pathways require further investigation. The

JAK/STAT pathway facilitates rapid signal transduction from the

cell membrane to the nucleus and induces the production of

oncogenic factors, serving as a key pathway regulating cancer cell

proliferation, metabolism and immune responses (258). The JAK/STAT3 pathway promotes

glycolysis and FAO, thereby contributing to drug resistance

(259,260). Several ncRNAs are effective

regulators of the JAK/STAT3 pathway (261,262). However, further research is

needed to elucidate the mechanisms by which these ncRNAs regulate

JAK/STAT3 in the context of metabolism and cancer drug resistance.

In addition, the circadian clock and cancer cell stemness are key

phenotypes that profoundly influence metabolic reprogramming

(263,264). ncRNAs serve a regulatory role in

the circadian gene and stemness driving pathways (265-267). For example, in gastrointestinal

tumors, miR-494-3p and miR-135b directly target the 3′UTR of brain

and muscle arnt-like protein 1 (BMAL1) to inhibit its expression.

BMAL1 interacts with Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 to suppress

glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase mitochondrial, resulting in a

reduction of LPA levels. By targeting BMAL1, miR-494-3p promotes

LPA metabolism and proliferation of HCC cells (259). Meanwhile, miR-135b disrupts the

tumor-suppressive circadian rhythm in pancreatic cancer via the

BMAL1/Yin Yang-1 axis, thereby promoting pancreatic cancer

progression and GEM resistance (268). ncRNAs mediate the occurrence and

progression of EC by disrupting circadian rhythm in EC cells

through the regulation of Zinc Finger and BTB Domain Containing 7A,

p21) and Neuronal PAS domain protein 2 expression (266). Regarding tumor stemness,

multiple ncRNAs enhance the expression of transcription factors

such as NF-κB and STAT3 in tumor cells to evade the toxic effects

of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (267). Mechanistically, these ncRNAs

activate key signaling pathways that promote the properties of

cancer stem cells. These pathways include Wnt/β-catenin,

PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Notch and TGF-β (269). This process not only promotes

cancer stemness but also facilitates the formation of feedback

loops, which in turn leads to cancer metastasis and drug resistance

(270). Exploring these ncRNAs,

particularly their modulation of circadian rhythm and

stemness-mediated metabolic alterations and drug resistance, offers

a promising and valuable option for future research.

Targeting ncRNAs to regulate metabolism presents a

promising strategy for personalized cancer therapy. However,

several challenges must be overcome before this approach can be

widely applied in clinical practice. A notable obstacle is the

toxicity of ncRNA-targeting drugs. For example, the phase 1 trial

of the liposomal miR-34a mimic MRX34 in patients with advanced

solid tumors showed some clinical activity but was terminated due

to four cases of immune-mediated serious adverse events (271). As methods for modulating ncRNA

expression in cells, common vectors such as liposomes and chitosan

and polymeric nanoparticles are relatively safe and effective for

large gene transfer, but they suffer from limitations such as low

transfection efficiency and poor transgene expression (272). Based on a mesenchymal stem cell

(MSC)-based gene delivery system, tumor suppressor genes are

introduced to enhance the specific expression of MSCs and improve

their homing effect. This positions MSC-based therapy for cancer as

a potential and effective strategy (273). By contrast, viral vectors,

including lentiviruses and adenoviruses, offer high infection

efficiency and sustained transgene expression but are hampered by

high immunogenicity and limited payload capacity (274). Future research may unlock the

potential of ncRNA-based therapy to combat drug-resistant cancer.

Collaborative efforts among molecular biologists, bioengineers and

clinicians will be essential to translate these insights into

clinically viable solutions.

The adaptability of tumor cells has led to a rising

prevalence of drug resistance, notably decreasing the overall

survival of patients with cancers (275). When resistance to first-line

chemotherapy drugs arises, adjustments to the chemotherapy regimen

or the addition of other agents are often required, which can

result in suboptimal therapeutic outcomes or more severe adverse

reactions. Previous studies (10,17) have demonstrated the pivotal role

of metabolic reprogramming in tumor drug resistance. The present

review systematically summarizes the mechanisms by which metabolic

reprogramming contributes to drug resistance in tumors, with a

focus on how ncRNAs mediate this process through the regulation of

glycolysis, lipid and glutamine metabolism and mitochondrial

dysfunction, as well as the potential of ncRNAs as biomarkers and

therapeutic targets. The specific expression patterns of ncRNAs in

tumor cells serve as indicators of both the metabolic state and

drug sensitivity of these cells. Targeting ncRNAs that regulate

metabolism may offer innovative strategies to combat tumor drug

resistance in the future.

Not applicable.

JL wrote the manuscript and constructed figures and

tables. YL wrote the manuscript. LF constructed figures. HC, ZW and

FD revised the manuscript. YZ and YH revised the manuscript. YX and

JM conceived the study. Data authentication is not applicable. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

No funding was received.

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bukhari SNA: Emerging nanotherapeutic

approaches to overcome drug resistance in cancers with update on

clinical trials. Pharmaceutics. 14:8662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Vasan N, Baselga J and Hyman DM: A view on

drug resistance in cancer. Nature. 575:299–309. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Mattiuzzi C and Lippi G: Current cancer

epidemiology. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 9:217–222. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tufail M, Hu JJ, Liang J, He CY, Wan WD,

Huang YQ, Jiang CH, Wu H and Li N: Hallmarks of cancer resistance.

iScience. 27:1099792024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Kubik J, Humeniuk E, Adamczuk G,

Madej-Czerwonka B and Korga-Plewko A: Targeting energy metabolism

in cancer treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 23:55722022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pavlova NN, Zhu J and Thompson CB: The

hallmarks of cancer metabolism: Still emerging. Cell Metab.

34:355–377. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Warburg O, Wind F and Negelein E: The

metabolism of tumors in the body. J Gen Physiol. 8:519–530. 1927.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Paul S, Ghosh S and Kumar S: Tumor

glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer

Biol. 86:1216–1230. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yoo HC, Yu YC, Sung Y and Han JM:

Glutamine reliance in cell metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 52:1496–1516.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Pavlova NN and Thompson CB: The emerging

hallmarks of cancer metabolism. Cell Metab. 23:27–47. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Stine ZE, Schug ZT, Salvino JM and Dang

CV: Targeting cancer metabolism in the era of precision oncology.

Nat Rev Drug Discov. 21:141–162. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Landau BR, Laszlo J, Stengle J and Burk D:

Certain metabolic and pharmacologic effects in cancer patients

given infusions of 2-deoxy-D-glucose. J Natl Cancer Inst.

21:485–494. 1958.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Slack FJ and Chinnaiyan AM: The role of

non-coding RNAs in oncology. Cell. 179:1033–1055. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Nemeth K, Bayraktar R, Ferracin M and

Calin GA: Non-coding RNAs in disease: From mechanisms to

therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet. 25:211–232. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sanchez-Mejias A and Tay Y: Competing

endogenous RNA networks: Tying the essential knots for cancer

biology and therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol. 8:302015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Lin W, Zhou Q, Wang CQ, Zhu L, Bi C, Zhang

S, Wang X and Jin H: LncRNAs regulate metabolism in cancer. Int J

Biol Sci. 16:1194–1206. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Shih JW, Wang LY, Hung CL, Kung HJ and

Hsieh CL: Non-coding RNAs in castration-resistant prostate cancer:

Regulation of androgen receptor signaling and cancer metabolism.

Int J Mol Sci. 16:28943–28978. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xu S, Wang L, Zhao Y, Mo T, Wang B, Lin J

and Yang H: Metabolism-regulating non-coding RNAs in breast cancer:

Roles, mechanisms and clinical applications. J Biomed Sci.

31:252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Keyvani-Ghamsari S, Khorsandi K, Rasul A

and Zaman MK: Current understanding of epigenetics mechanism as a

novel target in reducing cancer stem cells resistance. Clin

Epigenetics. 13:1202021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Zeng Z, Fu M, Hu Y, Wei Y, Wei X and Luo

M: Regulation and signaling pathways in cancer stem cells:

Implications for targeted therapy for cancer. Mol Cancer.

22:1722023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Yuan Y, Li H, Pu W, Chen L, Guo D, Jiang

H, He B, Qin S, Wang K, Li N, et al: Cancer metabolism and tumor

microenvironment: Fostering each other? Sci China Life Sci.

65:236–279. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lin X, Wu Z, Hu H, Luo ML and Song E:

Non-coding RNAs rewire cancer metabolism networks. Semin Cancer

Biol. 75:116–126. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang D, Guo Q, You K, Zhang Y, Zheng Y

and Wei T: m6A-modified circARHGAP12 promotes the

aerobic glycolysis of doxorubicin-resistance osteosarcoma by

targeting c-Myc. J Orthop Surg Res. 19:332024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhang Q, Wu J, Zhang X, Cao L, Wu Y and

Miao X: Transcription factor ELK1 accelerates aerobic glycolysis to

enhance osteosarcoma chemoresistance through miR-134/PTBP1

signaling cascade. Aging (Albany NY). 13:6804–6819. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

He W, Liang B, Wang C, Li S, Zhao Y, Huang

Q, Liu Z, Yao Z, Wu Q, Liao W, et al: MSC-regulated lncRNA

MACC1-AS1 promotes stemness and chemoresistance through fatty acid

oxidation in gastric cancer. Oncogene. 38:4637–4654. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ge X, Pan MH, Wang L, Li W, Jiang C, He J,

Abouzid K, Liu LZ, Shi Z and Jiang BH: Hypoxia-mediated

mitochondria apoptosis inhibition induces temozolomide treatment

resistance through miR-26a/Bad/Bax axis. Cell Death Dis.

9:11282018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Ding C, Yi X, Chen X, Wu Z, You H, Chen X,

Zhang G, Sun Y, Bu X, Wu X, et al: Warburg effect-promoted exosomal

circ_0072083 releasing up-regulates NANGO expression through

multiple pathways and enhances temozolomide resistance in glioma. J

Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:1642021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Sun X, Sun G, Huang Y, Hao Y, Tang X,

Zhang N, Zhao L, Zhong R and Peng Y: 3-Bromopyruvate regulates the

status of glycolysis and BCNU sensitivity in human hepatocellular

carcinoma cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 177:1139882020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Liu R, Chen Y, Liu G, Li C, Song Y, Cao Z,

Li W, Hu J, Lu C and Liu Y: PI3K/AKT pathway as a key link

modulates the multidrug resistance of cancers. Cell Death Dis.

11:7972020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Castellví A, Pequerul R, Barracco V,

Juanhuix J, Parés X and Farrés J: Structural and biochemical

evidence that ATP inhibits the cancer biomarker human aldehyde

dehydrogenase 1A3. Commun Biol. 5:3542022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hou GX, Liu PP, Zhang S, Yang M, Liao J,

Yang J, Hu Y, Jiang WQ, Wen S and Huang P: Elimination of stem-like

cancer cell side-population by auranofin through modulation of ROS

and glycolysis. Cell Death Dis. 9:892018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Giddings EL, Champagne DP, Wu MH, Laffin

JM, Thornton TM, Valenca-Pereira F, Culp-Hill R, Fortner KA, Romero

N, East J, et al: Mitochondrial ATP fuels ABC transporter-mediated

drug efflux in cancer chemoresistance. Nat Commun. 12:28042021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Lu S, Tian H, Li L, Li B, Yang M, Zhou L,

Jiang H, Li Q, Wang W, Nice EC, et al: Nanoengineering a zeolitic

imidazolate framework-8 capable of manipulating energy metabolism

against cancer chemo-phototherapy resistance. Small.

18:e22049262022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Roberts DJ and Miyamoto S: Hexokinase II

integrates energy metabolism and cellular protection: Akting on

mitochondria and TORCing to autophagy. Cell Death Differ.

22:248–257. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

36

|

Zhang Z, Deng X, Liu Y, Liu Y, Sun L and

Chen F: PKM2, function and expression and regulation. Cell Biosci.

9:522019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Jang M, Kang HJ, Lee SY, Chung SJ, Kang S,

Chi SW, Cho S, Lee SC, Lee CK, Park BC, et al:

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, a glycolytic intermediate, plays a key

role in controlling cell fate via inhibition of caspase activity.

Mol Cells. 28:559–563. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Dong Q, Niu W, Mu M, Ye C, Wu P, Hu S and

Niu C: Lycorine hydrochloride interferes with energy metabolism to

inhibit chemoresistant glioblastoma multiforme cell growth through

suppressing PDK3. Mol Cell Biochem. 480:355–369. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yalcin A, Clem BF, Imbert-Fernandez Y,

Ozcan SC, Peker S, O'Neal J, Klarer AC, Clem AL, Telang S and

Chesney J: 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase (PFKFB3) promotes cell cycle

progression and suppresses apoptosis via Cdk1-mediated

phosphorylation of p27. Cell Death Dis. 5:e13372014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Shi L, Pan H, Liu Z, Xie J and Han W:

Roles of PFKFB3 in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

2:170442017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cantelmo AR, Conradi LC, Brajic A, Goveia

J, Kalucka J, Pircher A, Chaturvedi P, Hol J, Thienpont B, Teuwen

LA, et al: Inhibition of the glycolytic activator PFKFB3 in

endothelium induces tumor vessel normalization, impairs metastasis,

and improves chemotherapy. Cancer Cell. 30:968–985. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|