Breast cancer (BC) had 2.3 million new cases and

670,000 deaths recorded in 2022 (1). Moreover, projections indicate that

by 2050, new cases will increase by 38%, and deaths will increase

by 68% (1). It is characterized

by high heterogeneity, strong tendency for metastasis and

resistance to treatment (2,3).

The numerous types of cell that constitute the tumor

microenvironment (TME) are not static bystanders within the tumor

but are key drivers of disease progression. These cells secrete and

express key regulatory factors, such as vascular endothelial growth

factor A (VEGFA), transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), matrix

metallopeptidase-9 (MMP-9), C-C motif chemokine ligand-22 and

interleukin-10 (IL-10), which modulate the TME composition, thereby

promoting the invasive progression of tumors, malignancy and

metastasis (4). As the TME

contains specific immune and stromal cell populations with notable

prognostic value, its key role in tumor development is gradually

gaining widespread recognition, making it an emerging field of

research with therapeutic potential (5-7).

As a highly conserved signaling pathway, the Wnt

signaling network serves a key role in core physiological

processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis,

migration, invasion and maintenance of cellular homeostasis

(8-10). Increasing evidence has revealed

that the abnormal regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway is

related to the occurrence and progression of BC (11,12). In more than half of BC cases, the

tumor cell nucleus has abnormally high β-catenin expression

(13). β-catenin, as a crucial

activation 'hub' in the Wnt signaling pathway and a key

transcriptional driving force in the epithelial-mesenchymal

transition (EMT) process, is associated with the histological

grade, clinical staging and lymph node metastasis and Ki-67

proliferation status of patients with BC, providing a novel

perspective for understanding the pathogenesis and prognostic

mechanisms of BC (14,15). Wnt signaling and the BC TME

exhibit a complex and multifactorial interactive dynamic

bidirectional association. Components of the TME affect the Wnt

signaling pathway within tumor cells, and abnormalities in Wnt

signaling in these cells drive changes in TME components (16-18). For example, abnormal activation of

Wnt signaling can help tumor cells in the TME evade immune system

surveillance, effectively hindering the infiltration process of T

cells, thereby mediating immune tolerance. Furthermore, in the BC

TME, the Wnt signaling pathway is not isolated but exhibits

crosstalk with other key signaling pathways (19). These signaling pathways are

coordinated, jointly regulating the dissemination and metastasis of

tumors, as well as resistance to traditional treatment methods,

revealing the complexity and diversity of BC pathogenesis (20-22).

The present review delves into the complex and

intricate mechanisms of the interaction between the Wnt signaling

pathway and TME in BC, including the functional roles of key

components and their secreted factors in the TME, unique properties

of physical influencing factors, associations with BC-related genes

and intrinsic mechanisms of interactions between cell signaling

pathways. The present review further explores the therapeutic

potential of modulating the Wnt signaling pathway within the BC TME

and its clinical implications, thereby providing new insight for BC

treatment strategies.

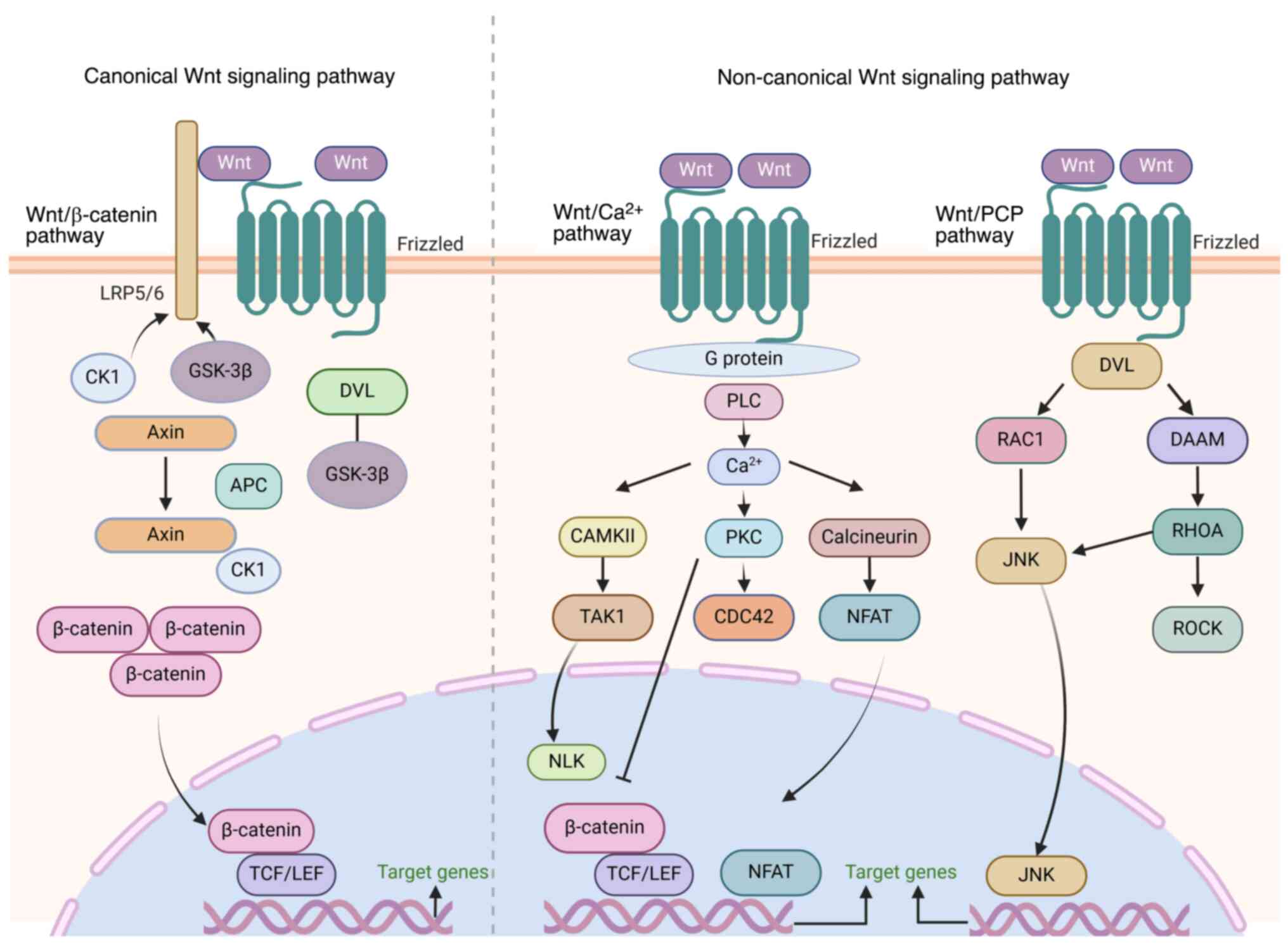

Under physiological conditions, the Wnt signaling

system acts as a core regulator of cellular functions through the

canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling, non-canonical Wnt/planar cell

polarity (PCP) and Wnt-Ca2+ signaling pathways to ensure

the balance of organismal growth, development and homeostasis.

However, when key components of this network undergo mutation,

epigenetic modification or crosstalk with other signaling networks,

they trigger abnormal activation of the Wnt signaling cascade and

its downstream genes (23).

Abnormal activation of Wnt signaling is associated with accelerated

tumor proliferation, extended survival time, enhanced invasiveness

and the maintenance of cancer stem cell (SC) characteristics

(24,25). The canonical Wnt pathway promotes

proliferation by upregulating cyclin D1, enhances anti-apoptotic

capacity through B cell lymphoma-extra large and maintains cancer

SC properties. The non-canonical pathway regulates disruption of

cell polarity and metastasis via ras-related C3 botulinum toxin

substrate guanosine triphosphatases and c-Jun N-terminal kinase

(JNK) signaling (26).

Simultaneously, Wnt signaling combats ferroptosis by activating

glutathione peroxidase 4, while mediating tissue pyroptosis and EMT

via the NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammasome (27-29). Numerous studies have explored the

diverse mechanisms of Wnt signaling activation in the occurrence

and development of cancer (23,30-32) (Fig.

1).

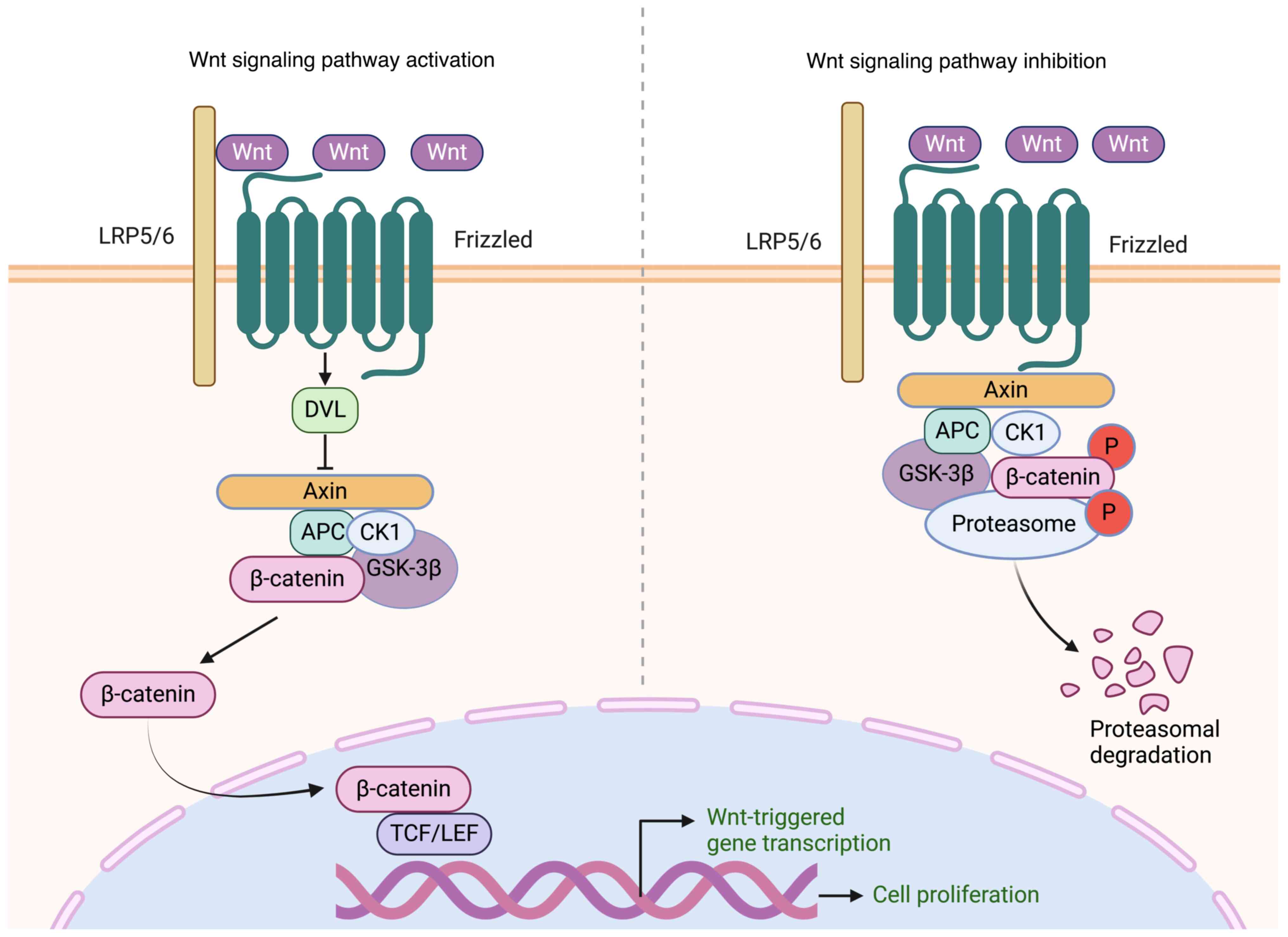

The canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway is activated by

a cascade of tightly controlled steps. Initially, the Wnt ligand

forms a complex with the frizzled receptor and low-density

lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) co-receptors,

triggering signaling. This interaction activates dishevelled (DVL),

a membrane-associated protein, which subsequently obstructs the

β-catenin degradation complex, composed of axis inhibition protein

(Axin), glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) and adenomatous

polyposis coli, preventing the breakdown of β-catenin.

Consequently, β-catenin accumulates in the cytoplasm before being

translocated to the nucleus. Upon binding to T cell factor/lymphoid

enhancer-binding factor (TCF/LEF) transcription factors, it induces

the activation of downstream genes. Through the activation of

downstream genes, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway serves a

critical role in regulating cellular functions, such as

proliferation, differentiation, migration and apoptosis (33). Within this pathway, a negative

feedback mechanism maintains signaling equilibrium, preventing both

excessive and insufficient activation, thus decreasing the risk of

pathological conditions, such as cancer (Fig. 2) (34).

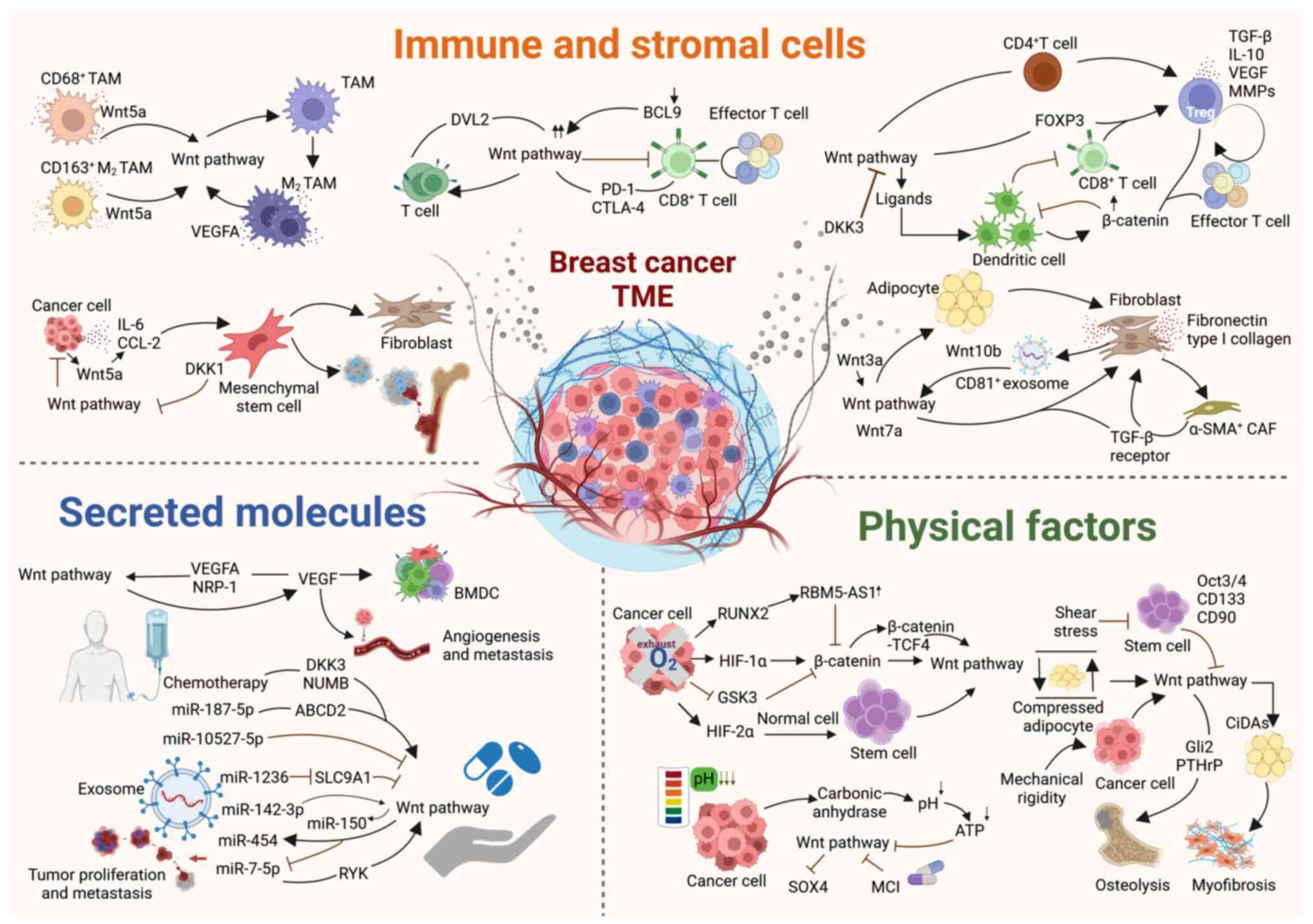

BC progression is a multifactorial process in which

the TME serves a key role. The BC TME is a diverse cellular

ecosystem that includes malignant cells, immune cell populations

and stromal tissue. These components and the factors they release

interact with the Wnt signaling pathway, collectively driving tumor

proliferation, invasion and metastasis, which are a series of

malignant events (17,37). Additionally, physical factors,

such as mechanical stress, hypoxia and acidification in tumor

regions regulate the Wnt signaling pathway and affect the

occurrence and trajectory of BC development. Analysis of the key

elements within the TME that regulate Wnt signaling provides a

theoretical foundation for uncovering the molecular mechanisms of

BC pathogenesis and developing targeted therapeutic drugs (Fig. 3).

TAMs serve a central role in innate and adaptive

immune responses because of their functional diversity and

adaptability. In the complex pathological mechanisms of BC, a

bidirectional interaction exists between Wnt signaling and TAMs,

particularly M2-type TAMs. Wnt signaling drives the polarization of

TAMs toward the M2 phenotype, which promotes the formation of an

immunosuppressive TME, thereby supporting the growth, invasion and

angiogenesis of BC and accelerating the survival and spread of

tumor cells. Inhibiting the Wnt signaling pathway through the use

of β-catenin inhibitors is an effective avenue to block M2

polarization, decreasing the expression levels of M2 markers and

thereby reversing the tumor-promoting effects of TAMs (38,39). Additionally, M2-type TAMs serve

another key role by secreting VEGFA, which activates the

neuropilin-1 (NRP-1)/GTPase-activating protein and VPS9

domain-containing protein 1/Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade in

triple-negative BC (TNBC) cells, enhancing the self-renewal ability

and metastatic potential of tumor cells (17). Moreover, TAMs serve a critical

role in regulating the activation state of the Wnt signaling

pathway. CD68+ and M2-polarized CD163+ TAMs

release Wnt5a, a signaling molecule that triggers Wnt signaling

activity in malignant and stromal cells, forming a cycle that

continuously drives tumor progression (40-43). Due to the potential of Wnt

signaling to regulate the M2 polarization of TAMs and the

activation of Wnt signaling pathways by factors secreted by M2-type

TAMs, the Wnt-TAM axis may be a therapeutic target in BC.

T lymphocytes are key elements of adaptive immune

responses, and their dysfunction is associated with tumor

progression and the formation of immune escape mechanisms (44,45). Research has revealed the impact of

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway on T cell function, which

reshapes the immune response potential of T cells by regulating the

expression of immune checkpoints, cytokine synthesis and T cell

differentiation status (46).

Specifically, the activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway

upregulates immune checkpoint markers on the surface of

CD8+ T cells, such as programmed death receptor-1 and

cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) (47-49). This upregulation pushes T cells

toward exhaustion and promotes the formation of an

immunosuppressive microenvironment, facilitating tumor progression

(50). In the immune regulatory

network of BC, DVL2 is a key hub of the Wnt signaling cascade that

controls the expression pattern of Wnt target genes in

HER2+ BC cells by regulating the transcriptional

activity of genes related to immune function and T cell survival

(51). Moreover, the loss of B

cell lymphoma 9, a key transcriptional coactivator of β-catenin,

can effectively weaken abnormal Wnt/β-catenin signaling, thereby

enhancing T cell-mediated tumor immunogenicity, offering potential

for BC immunotherapy (52). In

CD8+ T cells, Wnt signaling inhibits the differentiation

of these cells into effector T cells (TEFFs). This mechanism not

only maintains the self-renewal potential of CD8+ T

cells, but also affects the differentiation fate of T cell

progenitors, contributing to the diversity and complexity of T cell

function (53). Future research

should investigate the interaction network between different T cell

subtypes, their secreted cytokines and Wnt signaling components to

provide more precise strategies for BC immunotherapy.

As regulators of immune homeostasis, Tregs play key

roles in regulating immune response and preventing excessive

autoimmunity (54). Previous

studies have analyzed the mechanisms of the Wnt signaling pathway

and related molecules, including Wnt ligands, forkhead box P3

(FoxP3), poly(C)-binding protein 1 (PCBP1), and dickkopf-related

protein 3 (DKK3) in the TME of Tregs (55-58). Specifically, Wnt ligands activate

β-catenin signaling in dendritic cells, driving the balance between

TEFF and Tregs (55). However,

when β-catenin signaling is overly active, this balance is

disrupted, leading to impaired dendritic cell recruitment,

inhibition of CD8+ T cells, and proliferation of Tregs,

which suppress the antitumor immune response (16,56). By inducing FoxP3 expression, the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway promotes the activation and

differentiation of Tregs, triggering the release of

immunosuppressive factors, such as TGF-β and IL-10. This

facilitates tumor growth and immune evasion (56,59,60). In BC, the role of PCBP1 in

modulating Wnt signaling is key for stimulating adaptive antitumor

immune responses, and its decreased expression is associated with

the imbalance of immune cell populations within tumors, which

promotes the expansion of Tregs and subsequently inhibits the

activation of antitumor immune responses (57). Additionally, DKK3 secreted by

tumors may promote the reprogramming of CD4+ cells into

Tregs by blocking the Wnt signaling pathway, thereby supporting the

survival and spread of tumor cells (56,58). Thus, the association between

Wnt/β-catenin signaling and Tregs in the BC TME may provide a

theoretical foundation for developing targeted treatment strategies

aimed at enhancing antitumor immune responses and improving

clinical outcomes.

CAFs, a highly plastic and heterogeneous stromal

cell population in the BC TME, not only maintain the structural

framework and mechanical stability of tissue but also regulate

biochemical signal transduction processes (61,62). In response to Wnt/β-catenin

signaling, CAFs undergo transformation under the induction of Wnt

proteins, secreting a range of bioactive molecules and generating

exosomes, which facilitate tumor growth and invasion (63,64). There is an association between the

origin of CAFs in BC and Wnt proteins. For example, Wnt7a

transforms quiescent fibroblasts into α-smooth muscle

actin-positive CAFs by binding to TGF-β receptors, thereby

activating their potent tumor-promoting potential (62). Tumor-derived Wnt3a promotes

conversion of adipocytes to CAFs by activating the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway (62,65). Further research has revealed that

CAFs, as a key source of Wnt ligands, actively promote BC

progression by releasing paracrine signals (65,66). These signals maintain tumor

stemness, stimulate the growth of the primary tumor and accelerate

the metastatic colonization process (63,64). For example, Wnt3a activation

enhances the synthesis of key matrix proteins, such as fibronectin

and type I collagen, which further induces synthesis of MMP-9 in BC

cells, thereby enhancing their migration and invasion capability

(65,67,68). CAF-derived exosomes carrying CD81

serve a key role in stimulating BC cell motility due to activation

of the Wnt/PCP signaling pathway. Wnt10b contained within the

exosomes triggers a self-reinforcing cycle by activating the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway, promoting progression and widespread

dissemination of tumors (66,69). Therefore, the interaction between

CAFs and the Wnt signaling pathway underlies the progression of BC

and may provide a basis for development of innovative treatment

strategies.

MSCs have garnered attention for their potential to

differentiate into various cell types, such as adipocytes,

osteoblasts and chondrocytes, which affect tumor angiogenesis,

immune modulation and responses to antitumor therapy (70-72). In regulating interactions with BC

cells, the Wnt signaling pathway serves as a key factor in driving

tumor growth and bone metastasis, while also inhibiting tumor

progression through diverse mechanisms (73). Specifically, the Wnt signaling

pathway connects MSCs with cancer cells, enhancing the

pro-tumorigenic properties of MSCs by inducing their

differentiation into CAFs (74).

Wnt5a released by BC cells triggers the secretion of IL-6 and

monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, which enhances the

phagocytic-like activity of MSCs and accelerates tumor

dissemination. In in vitro models of BC bone metastasis, the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway regulates osteogenic activity in a bone

microenvironment composed of human MSCs, promoting the progression

of BC bone metastasis (75,76). The functions of MSCs are not

limited solely to promoting tumorigenesis; they also have the

ability to inhibit tumor growth (77-79). MSCs effectively limit tumor

progression through a number of biological mechanisms, including

weakening Wnt and AKT signaling, blocking angiogenesis, stimulating

the recruitment of inflammatory cells and inducing cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis (77-82).

In Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 cells, DKK1 derived from MSCs

successfully inhibits tumor cell proliferation by downregulating

β-catenin signaling (65,77). Additionally, in controlled

experimental settings, chondrogenic membrane-derived MSCs inhibit

the proliferation of BC cells, an effect mediated by the regulation

of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling cascade. These findings revealed the

dual nature of MSCs in BC, emphasizing their potential in both

promoting and inhibiting tumor progression through different

signaling pathways. Future studies should clarify the specific

functions and pathways of MSCs in BC.

VEGF is a key factor in regulating angiogenesis,

tumor progression and metastatic spread and promotes the generation

of a tumor immune-suppressive environment (83,84). Wnt signaling influences

endothelial cells and paracrine signaling, further regulating

vascular smooth muscle and vascular network structure (85,86). In BC, the canonical Wnt pathway

not only drives the transcription of VEGF but also interacts with

VEGF and its key receptor NRP-1, whereas the non-canonical Wnt

pathway collaborates with VEGF to affect angiogenesis and cancer

progression. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway can directly

lead to the transcription of multiple target genes, including VEGF,

by stabilizing β-catenin and promoting its transfer to the nucleus,

thereby driving angiogenesis (87). In the formation of BCSCs and the

induction of tubular angiogenic structures, the binding of VEGFA to

its receptor NRP-1 serves a key role. In the VEGFA/NRP-1 signaling

axis, the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway acts as a key downstream

effector; its transmission is triggered by the activation of VEGFA,

thereby facilitating persistence of CSCs (88,89). This cascade enhances the invasive

potential of tumors and accelerates the malignant transformation of

breast tissue. In addition, the non-canonical Wnt pathway often

works together with VEGF, regulating key events in tumor

angiogenesis, such as endothelial cell movement, increased vascular

permeability and extracellular matrix remodeling (90,91). Given the key role of Wnt signaling

in BC angiogenesis, precise therapeutic strategies targeting this

pathway may provide novel avenues for overcoming resistance to

traditional anti-angiogenic therapy, thus holding clinical

translational potential.

Exosomes, as nanoscale vesicles for intercellular

communication, play a key role in tumor progression and acquisition

of therapeutic resistance within the TME (37,92-96). In BC, the Wnt signaling pathway

influences the evolution of tumors, chemoresistance and the

development of resistance reversal strategies by regulating the

content of microRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) in different exosomes

(97,98). Specifically, under the action of

the Wnt signaling pathway, BC cells decrease levels of miR-7-5p in

exosomes, thereby enhancing their migration and invasion capability

and releasing miR-454 to maintain the self-renewal potential of

CSCs (99,100). The roles of exosomal miRNAs in

BC progression vary. Among them, exosomal miR-10527-5p can block

the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway to inhibit cancer cell

migration and invasion, whereas miR-7-5p from exosomes derived from

less invasive BC cells inhibits metastasis by targeting the

receptor-like tyrosine kinase gene and the non-canonical Wnt

pathway (99,100). Conversely, upregulated

miR-142-3p expression activates the Wnt pathway and induces miR-150

production, thereby promoting the over-proliferation of BC cells

(101). Exosomes serve a central

role in chemoresistance. Chemotherapy-induced exosomes activate the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway by targeting DKK3 and Notch signaling pathway

inhibitor protein numb homolog, inducing resistance; exosomes

released by paclitaxel-resistant BC cells carry miR-187-5p that

regulates ATP-binding cassette subfamily D member 2 and the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway, affecting proliferation. Exosomes

transported from adipose-derived MSCs transfer miR-1236, which

decreases resistance to cisplatin by inhibiting solute carrier

family 9 member A1 activity and Wnt/β-catenin signaling (101). These findings not only reveal

the dual role of exosomes in BC progression, but also provide a

basis for exploring resistance reversal strategies in BC.

Mechanical stress resulting from the integrated

action of multidimensional factors, such as tissue topography,

matrix stiffness, physical stretching, shear stress and

compression, is closely related to the initiation, development and

dissemination of cancer (102,103). Mechanical stress regulates BC

progression by affecting the response of adipocytes, SCs, cancer

cells and fibroblasts to the Wnt signaling pathway. For example,

shear stress can downregulate the expression of SC marker

molecules, thereby blocking the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, increasing

cellular stiffness and inducing the differentiation of cancer cells

toward a mature state (104).

Adipocytes, an important component of breast tissue, undergo

dedifferentiation transformation via the mechanosensitive response

mechanism of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway when subjected to physical

compression, forming compression-induced dedifferentiated

adipocytes (CiDAs) (105). CiDAs

accelerate myofibroblastosis within the TME, facilitating BC cell

proliferation (105). Matrix

rigidity serves a key role in regulating the invasive potential of

breast tumor cells at the primary site of disease (106-108). The combination of matrix

rigidity and matrix-secreted factors stimulates Gli family zinc

finger protein 2 and parathyroid hormone-related protein through

Wnt signaling in osteolytic breast cancer cells, driving

tumor-induced osteolysis (109).

Intervention strategies targeting physical factors and the Wnt

signaling pathway may provide an effective therapeutic approach to

delay tumor metastasis (103,109).

Hypoxia, a constant and heterogeneous characteristic

of the TME, is pervasive in most types of solid tumor owing to the

abnormally high expression of hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF) under

low-oxygen conditions (110,111). In the hypoxic microenvironment

of BC, HIF regulates the Wnt signaling pathway and stability of

β-catenin while inducing upregulation of runt-related transcription

factor 2 (RUNX2) and inhibiting the activation of GSK3,

facilitating aggressive progression of tumors and the enhancement

of cancer cell invasiveness. Specifically, HIF-1α stabilizes the

structure of β-catenin and enhances its transcriptional activity;

on the other hand, it upregulates the expression of Wnt ligands and

receptors, thereby transcriptionally activating Wnt1-inducible

signaling pathway protein 3. This activates the Wnt pathway,

facilitating tumor growth, metastasis and angiogenesis (112). Concurrently, HIF-2α reprograms

normal cells into a SC-like phenotype by activating the Wnt

signaling pathway in BC cells and induces chemotherapy resistance

(113). This not only drives

metabolic reprogramming and maintains stemness of BC cells but also

enhances glycolysis and glutaminolysis through the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway, ensuring the survival of cancer cells under extreme

hypoxic conditions (114-120).

Hypoxia-induced RUNX2 upregulates RNA binding motif protein

5-antisense RNA 1, preventing the degradation of β-catenin and

promoting the formation of β-catenin-TCF4 transcription complex,

thereby amplifying the effect of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and

accelerating tumor progression (121). Hypoxic conditions inhibit the

activation of GSK3, decreasing the phosphorylation and subsequent

degradation of β-catenin, further activating the Wnt/β-catenin

pathway, leading to increased expression of snail family

transcriptional repressor 1, and enhancing the invasiveness of

cancer cells (122). These

findings not only reveal the key role of hypoxia in tumor

progression but also provide perspective for the development of

innovative therapy.

A common characteristic of solid tumors is the

acidic metabolic environment, which not only promotes the

proliferation of tumor cells, but also serves a key role in

resistance to radiotherapy and chemotherapy (123). The acidic TME is primarily

shaped by hydrogen ions released from the dissociation of lactate

and carbonic acid. Lactate originates from the anaerobic glycolysis

of tumor cells, whereas carbonic acid is generated by the reaction

of CO2 with H2O catalyzed by carbonic

anhydrase (CA) (123). In BC,

abnormal regulation of CA exacerbates this acidification, further

disrupting the internal pH balance of tumors (124). Intracellular acidification

triggers the activation of the unfolded protein response and ATP

depletion, thereby inhibiting Wnt signaling activity (125). Drugs that induce intracellular

acidification (such as mitochondrial complex I) effectively

suppress the Wnt signaling pathway, decrease the expression of

SRY-box transcription factor 4 and inhibit SC characteristics and

activity of BC cells (125).

These findings not only reveal the potential of targeting the Wnt

pathway in BC treatment but also provide perspective on strategies

that exploit the acidic TME. Therefore, modulating the pH of the

TME may serve as an innovative adjuvant therapy, laying a

foundation for tumor treatment.

In recent years, with the continuous advancement of

oncology research, the association between BC-related genes and the

Wnt signaling pathway has become a research hotspot in this field

(126-128). BC-associated genes, such as

BRCA1, BRCA2 and tumor protein P53 (TP53) are associated with the

Wnt signaling pathway and serve key roles in maintaining normal

physiological function, genomic stability and cell fate

determination.

BRCA1 and BRCA2. BRCA genes, mainly BRCA1 and BRCA2,

are closely associated with the risk of hereditary BC (129,130). They effectively inhibit

excessive cell proliferation and maintain genomic stability by

repairing double-stranded DNA breaks (131). In germline BRCA1 mutation

carriers, the microenvironment harboring heterozygous BRCA1

mutations may promote BC development by creating a tumor-promoting

niche, particularly by affecting the stromal cells residing in the

TME (132,133). Wu et al (134) reported that in basal-like BC,

the Wnt effector Slug epigenetically suppresses BRCA1, resulting in

a negative association between Wnt signaling and BRCA1 expression.

Furthermore, Wu et al (134) indicated that canonical Wnt

signaling drives cancer cell EMT and tissue invasion by modulating

Slug activity, inhibiting the function of BRCA1 and BRCA2 and

rendering breast epithelial cells more vulnerable to

etoposide-mediated DNA damage. Li et al (135) revealed that BRCA1 deficiency may

increase the sensitivity of the active form of β-catenin protein to

H2O2, thereby decreasing its expression. To

the best of our knowledge, however, research on the association

between BRCA genes and the Wnt signaling pathway remains limited,

and more mechanistic studies are needed (135).

TP53 gene mutations serve a key role in BC.

Transcription factor p53, encoded by TP53, serves a crucial role in

regulating a series of cellular activities, including cell cycle

arrest, apoptosis, metabolic regulation, DNA repair and cellular

senescence (136-138). Abnormal activation of the Wnt

signaling pathway effectively suppresses TP53 activity, thereby

facilitating survival of tumor cells and enhancing their resistance

to apoptosis (139). In BC

cells, the absence of TP53 promotes the release of key Wnt factors,

such as Wnt1, Wnt6 and Wnt7a, but also stimulates TAMs to produce

IL-1β, a key inflammatory mediator, through the binding of these

factors with frizzled class receptor 7 (FZD7) and FZD9 receptors on

the surface of TAMs (140).

Moreover, in TP53-deficient basal-like BC tumors, activity of the

Wnt signaling pathway is enhanced and is often accompanied by the

expression of the non-canonical Wnt signaling mediator receptor

tyrosine kinase-like orphan receptor 2 (Ror2). The existence of

Ror2 as an alternative Wnt receptor enhances the diversity of Wnt

signaling and supports Wnt/β-catenin-independent signaling

functions in TP53-deficient model (141). Therefore, the combined

inhibition of TP53 and the Wnt signaling pathway may provide

effective therapeutic options for patients with BC.

Somatic genomic aberrations in breast tumors disrupt

key signaling networks that regulate cell division, survival and

differentiation, highlighting numerous potential biomarkers and

therapeutic targets (142).

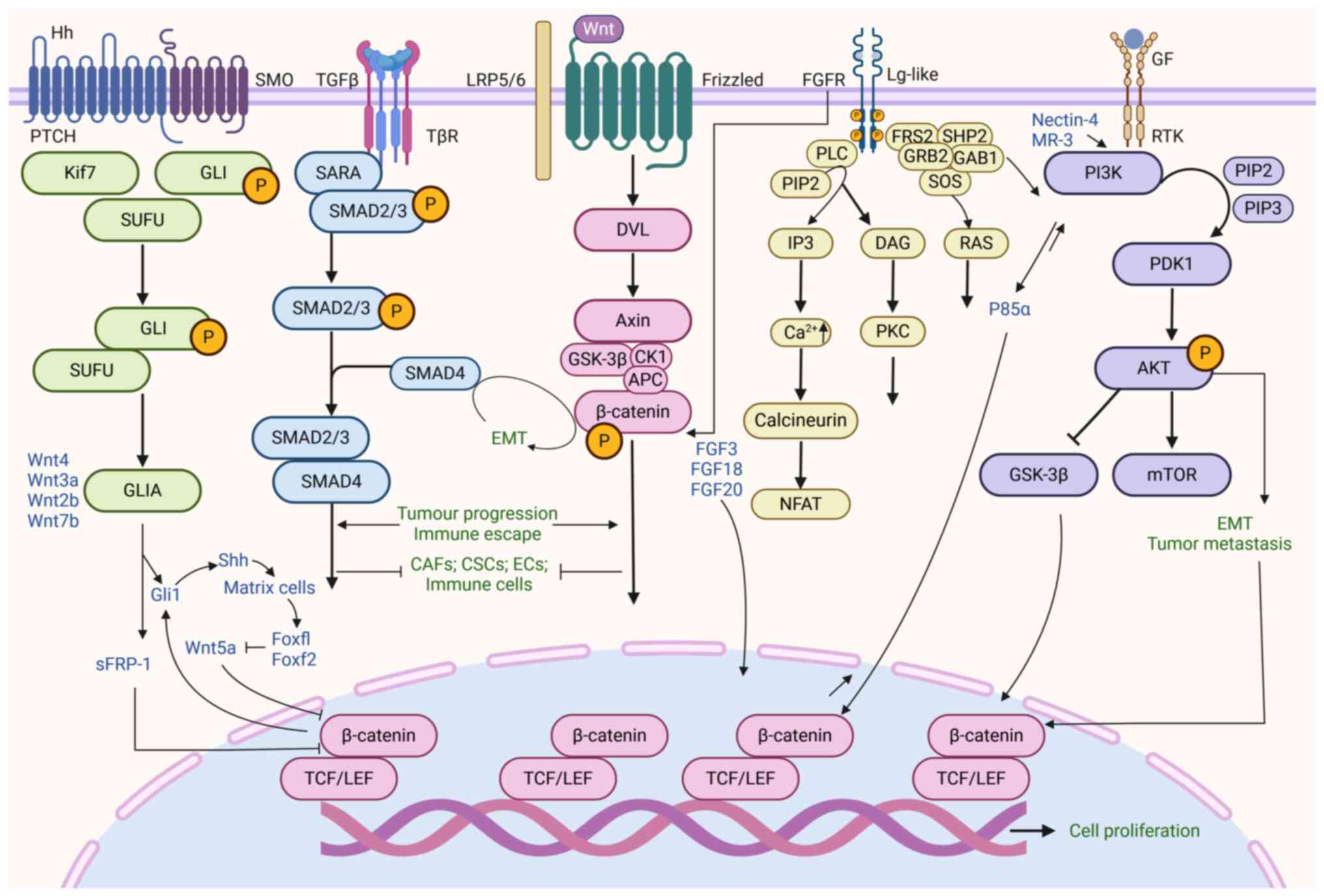

Previous studies have demonstrated crosstalk between the Wnt

signaling network and key pathways within the TME, including TGF-β,

phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/Akt, fibroblast growth factor

(FGF) and Hedgehog signaling (37,143,144). These signaling networks not only

control tumor cell proliferation and migration, but also serve

indispensable roles in immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming and

therapeutic resistance, which are critical biological processes

(145). The association between

the Wnt signaling pathway and other core pathways, as well as the

underlying biological mechanisms, may serve as potential

therapeutic strategies and biomarkers (Fig. 4).

The Wnt and TGF-β signaling pathways, as

evolutionarily conserved regulatory mechanisms, serve crucial roles

in embryonic differentiation, tissue homeostasis and pathological

processes. Abnormal activation is closely associated with BC

progression, increased potential for metastasis and poor clinical

prognosis (146,147). The mechanisms by which these

pathways influence BC primarily involve driving EMT, inducing

immune evasion and maintaining BC cell stemness (148). EMT, as a key mechanism of tumor

metastasis, is regulated by the Wnt and TGF-β signaling pathways.

TGF-β, acting as a catalyst for EMT, can prompt epithelial cells to

transition into invasive mesenchymal phenotypes (149). Concurrently, the Wnt pathway,

particularly its β-catenin-activated form, promotes EMT. These two

pathways collectively regulate gene expression networks associated

with EMT through interactions between β-catenin and SMAD proteins,

thereby accelerating the invasion and migration of BC cells

(149). In addition to

regulation of EMT, the crosstalk between the Wnt and TGF-β

signaling pathways amplifies their individual effects in promoting

immune evasion. TGF-β signaling activates immune escape mechanisms,

while Wnt signaling is involved in immune modulation, especially in

promoting immune tolerance (32,150). The maintenance of BCSCs is a

component of the functional intersection of Wnt and TGF-β pathways,

which are key for tumor development, metastasis and the emergence

of therapeutic resistance. The Wnt pathway drives the self-renewal

of BCSCs via β-catenin-mediated transcriptional activation, whereas

TGF-β enhances the maintenance of BCSCs by promoting stemness

(151). More specifically,

non-canonical Wnt signaling, by maintaining CSCs in a quiescent

state in association with TGF-β signaling, enhances the EMT

process, thereby promoting the maintenance and expansion of CSCs

(151). Interactions between

these pathways provide valuable insight for the development of

innovative therapeutic interventions. Compared with the inhibition

of a single pathway, targeting both Wnt and TGF-β pathways

simultaneously provides a more efficient approach to improving the

outcomes of BC treatment (152,153).

The PI3K/Akt pathway plays a pivotal role in

regulating core cellular activities, such as proliferation,

division, metabolic adaptation, survival and angiogenesis (154,155). The PI3K/Akt and Wnt pathways are

associated with tumor biological behaviors through regulating CSC

self-renewal, accelerating EMT and metastasis and affecting

angiogenesis, thus facilitating progression of BC. In BC, a key

factor in the combined action of the Wnt and PI3K/Akt signaling

pathways to promote CSC self-renewal is the interaction between

β-catenin and the PI3K regulatory subunit p85α, which enhances the

catalytic activity of PI3K, thereby triggering the phosphorylation

and activation of Akt (156,157). Further research has shown that

the PI3K/Akt pathway intersects with the canonical Wnt signaling

cascade under the regulation of GSK3β, where Akt phosphorylates and

inhibits GSK3β, amplifying the efficiency of Wnt signal

transduction and further promoting the self-renewal of CSCs

(158-160). In terms of promoting EMT and

metastasis, Siddharth et al (161) revealed the overexpression of

nectin-4 drives Wnt/β-catenin signaling through the PI3K/Akt axis,

thereby enhancing the EMT process and promoting metastasis.

Simultaneously, the PI3K/Akt signal phosphorylates and activates

β-catenin; this upregulates the expression spectrum of genes

associated with EMT and enhances its interaction with TCF/LEF

transcription factors, thus advancing the EMT process (162). 3,5,4′-trimethoxystilbene can

affect E-cadherin levels and nuclear localization of β-catenin by

regulating the PI3K/Akt signaling axis and GSK3β, thereby reversing

EMT in BC cells (163). In

addition, the role of Wnt3a and the PI3K/Akt pathway in

angiogenesis has attracted increasing attention (164). Thymoquinone, as an effective

inhibitor, simultaneously impairs the normal function of PI3K and

Wnt3a signaling pathways, thereby inhibiting angiogenesis (164). Arqués et al (165) reported that the combined use of

the PI3K inhibitor BKM120 and the Wnt signaling inhibitor LGK974

can decrease tumor progression and metastasis in BC. These findings

provide a theoretical and experimental basis for the development of

targeted therapeutic strategies for the PI3K/Akt and Wnt signaling

pathways and the formulation of personalized treatment plans.

FGFs are involved in controlling a broad range of

cellular functions, including SC survival, proliferation,

programmed cell death inhibition, drug resistance and angiogenesis

(166,167). The FGF signaling pathway

interacts with the Wnt pathway and regulates the transcriptional

activity of target genes. Members of the FGF family activate the

Wnt pathway through various mechanisms, such as inducing β-catenin

modification and promoting the phosphorylation of low-density LRP6,

and these pathways exhibit synergistic oncogenic effects in mouse

mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-induced tumors. FGF family members FGF18

and FGF20 promote Wnt pathway activation via

β-catenin-TCF/LEF-dependent transcription (168,169). Activation of FGF receptors

induces tyrosine phosphorylation-mediated modification of

β-catenin, leading to the detachment of β-catenin from adherens

junctions and a decrease in its N-terminal serine/threonine

phosphorylation levels. By blocking the proteasomal degradation

pathway of β-catenin, this mechanism enhances the self-reinforcing

loop of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (170-172). Additionally, FGF signaling

promotes the phosphorylation of LRP6 mediated by cyclin

Y/vertebrate homolog PFTK, further activating the Wnt pathway

during the G2/M transition of the cell cycle (173). The interaction between Wnt-1 and

FGF3 was initially detected in tumors induced by MMTV (174,175). FGF3, as an oncogene, triggers

the occurrence of ~40% of MMTV infection-dependent tumors with

Wnt-1. MMTV insertional mutagenesis studies have demonstrated that

simultaneous activation of Wnt and FGF signaling components is one

of the most common genetic alterations in breast tumors (176,177). Overactivation of the Wnt and FGF

signaling pathways is considered a potential molecular marker for

predicting the response of BC to next-generation eukaryotic

initiation factor 4A RNA helicase inhibitors (178). Therefore, the interaction

between Wnt and FGF signaling in the BC TME is a dynamic and

complex process that affects the behavioral patterns of tumor cells

and promotes BC progression.

The Hedgehog signaling cascade is a highly

conserved process in evolution and serves a crucial role in cell

differentiation, tissue development, homeostasis and EMT (179). Within the complex network of

tumor biology, the crosstalk between the Wnt and Hedgehog signaling

pathways primarily occurs through the transcription factor

Gli1-mediated control of secreted frizzled-related protein 1

(sFRP-1) and sonic hedgehog (Shh) expression, and Gli1 exerts a

synergistic impact with β-catenin, shaping the progression of BC.

Specifically, the key transcription factor Gli1 in the Hedgehog

pathway mediates crosstalk with the Wnt pathway by regulating the

negative regulator sFRP-1 in the Wnt signaling pathway (180). When the function of sFRP-1 is

compromised, the canonical Wnt pathway is abnormally activated,

leading to disorders in the signaling network (180). The regulatory role of Gli1 is

not limited to sFRP-1 but also involves other members of the Wnt

family, such as Wnt2b, Wnt4 and Wnt7b. Furthermore, Gli1

upregulates the expression of the secreted Hedgehog Shh, which

transmits paracrine signals to the surrounding stromal cells,

triggering biological effects. Upon receiving the Shh signal,

stromal cells upregulate the expression of forkhead box F1 (Foxf1)

and Foxf2, thereby inhibiting the production of Wnt5a in the stroma

and indirectly regulating the activity of β-catenin (181). There is an association between

nuclear Gli1 and β-catenin activity. The expression of exogenous

constitutive nuclear β-catenin can enhance the activity of Gli1

reporter genes, indicating that the sustained activation of Wnt

signaling can enhance the transcriptional efficacy of Gli (182). Arnold et al (183) reported that the co-elevation of

nuclear Gli1 and β-catenin activity is associated with the

progression of TNBC stage and poor clinical prognosis (183). Concurrent activation of the

Hedgehog and Wnt pathways is also associated with a decline in

recurrence-free and overall survival rates in patients with TNBC

(183). Thus, the synergistic

activation of the Wnt and Hedgehog pathways may serve as an

important biomarker for the progression and therapeutic response of

BC, providing avenues for optimizing clinical treatment plans and

improving the prognosis of patients with BC.

While exploring the complex mechanisms of the TME,

abnormal regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway has been

identified as a key element in tumor progression, affecting

angiogenesis, immune evasion and metastasis (184). In addition, the Wnt signaling

pathway affects the efficacy of anti-HER2 therapy, chemotherapy and

immunotherapy, influencing the success of BC treatment and patient

prognosis. For example, in HER2-overexpressing BC cells, Wnt3

overexpression activates the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which

not only leads to the transactivation of EGFR and promotes an

EMT-like transformation but may also be a key cause of trastuzumab

resistance (185,186). This signaling pathway may

regulate CD36 levels, prompting resistant mesenchymal CSCs to

transition to a treatment-sensitive epithelial state, thereby

affecting lapatinib resistance (187,188). In vitro studies by Xu

et al (189) have shown

that β-catenin expression is associated with chemoresistance in

TNBC, as β-catenin knockdown can restore the sensitivity of TNBC

cells to doxorubicin- or cisplatin-mediated cell death. Shetti

et al (190) reported

that the combination of low-dose paclitaxel and XAV939 (a Wnt

signaling inhibitor) can inhibit EMT and angiogenesis by inducing

apoptosis and suppressing Wnt signaling, demonstrating its

therapeutic potential for TNBC. Upregulation of CSC-related Wnt

signaling and activation of β-catenin signaling in PD-L1-high TNBC

suggest that selective Wnt/β-catenin inhibitors may decrease

resistance and re-sensitize TNBC to anti-PD-L1/anti-CTLA-4

monoclonal antibody immunotherapy (191-195).

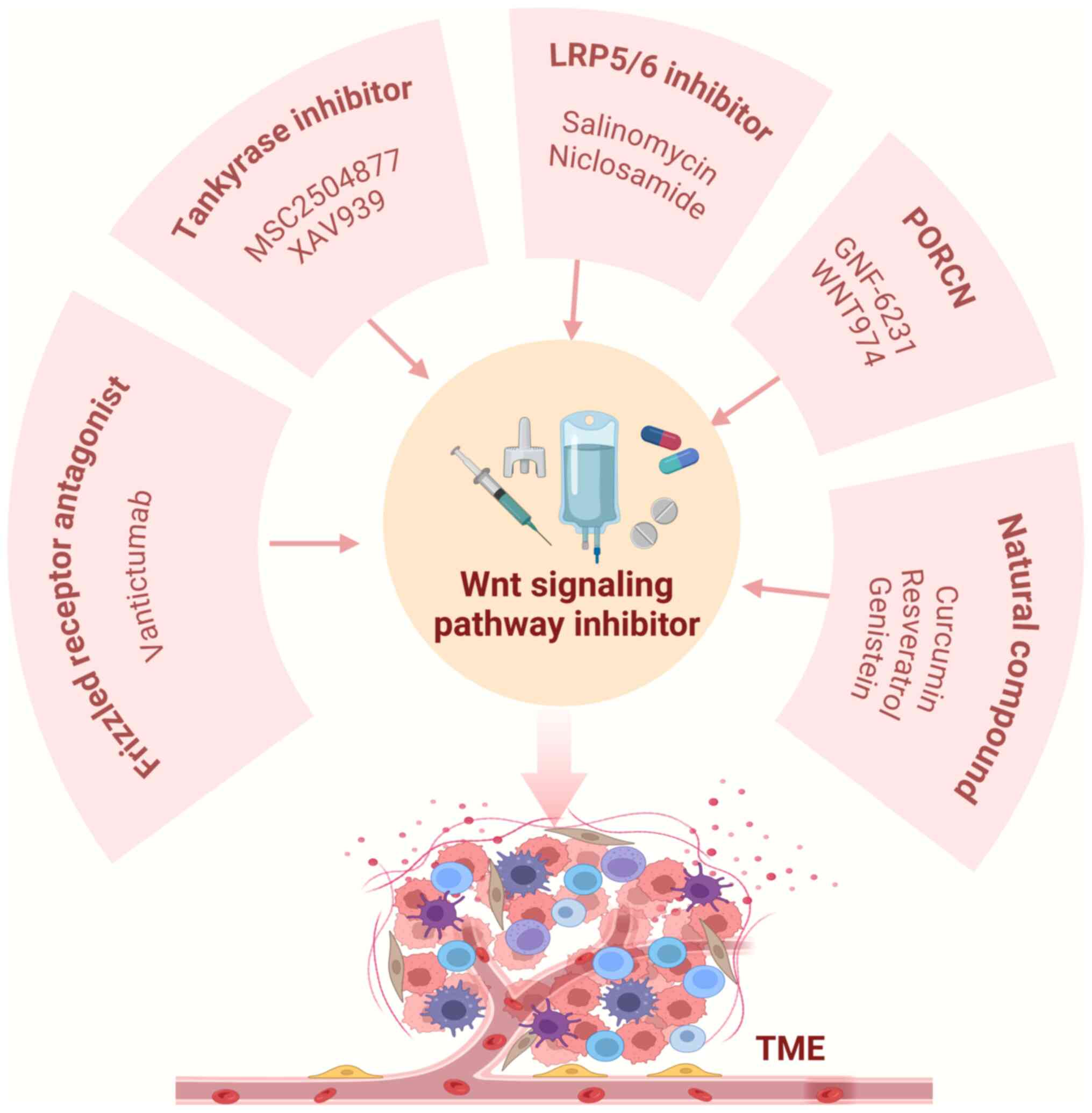

Developing therapeutic strategies targeting both

the canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways is key for

advancing precision medicine and genome-based disease therapy. Wnt

pathway inhibitors, including porcupine (PORCN) and LRP5/6

inhibitors, frizzled receptor antagonists, tankyrase inhibitors and

natural compounds may be used to target the Wnt signaling pathway

in the BC TME (Fig. 5). These

inhibitors not only modulate the complex signaling network within

the TME but also suggest that precise intervention in the Wnt

pathway may provide new avenues for BC treatment.

PORCN, a member of the membranebound

O-acyltransferase family, catalyzes the palmitoylation of Wnt

ligands, a key step that allows Wnt ligands to be secreted, and

effectively activates the Wnt signaling pathway, thereby regulating

fundamental physiological functions, such as cell differentiation,

proliferation, migration and apoptosis (196-201). To intervene in the

palmitoylation of Wnt proteins within the endoplasmic reticulum,

PORCN inhibitors effectively prevent the secretion of Wnt proteins

and curb the abnormal accumulation of β-catenin to restore normal

cell proliferation and signal transduction (202,203). In a preclinical study of BC

mice, the PORCN inhibitor GNF-6231 showed strong antitumor

activity, stimulating a notable tumor response (204). Similarly, another PORCN

inhibitor, LGK974, not only blocks the secretion of Wnt proteins,

but also effectively inhibits the activation of Wnt signaling

(205). In a preclinical study

of epithelial ovarian cancer, LGK974 in combination with paclitaxel

demonstrates synergistic antitumor effects (206). In BC models induced by Wnt

signaling, such as the MMTV model, LGK974 also performs well at

doses tolerable to animals, achieving tumor regression while

decreasing the phosphorylation levels of LRP6 and the expression of

Axin2 (207,208). LGK974 has entered phase I

clinical trials, and its potential as a monotherapy in combination

with PDR001 for the treatment of Wnt signaling-driven cancer,

including TNBC, is being evaluated (207,209). The aforementioned trials aim to

assess the clinical efficacy and safety of LGK974 and to propose

innovative strategies for Wnt signal inhibition in BC treatment

(30).

LRP5/6, a key co-receptor in the Wnt signaling

pathway, plays a key role in the β-catenin-mediated canonical

signal transduction process. Alkalescel, initially recognized as an

antimicrobial potassium ionophore, inhibits phosphorylation of

LRP5/6 and promotes its degradation, thereby inhibiting BC cell

proliferation and inducing apoptosis (210). Salinomycin can downregulate

LRP5/6 expression, further decreasing the transmission of Wnt

signaling (211,212). By contrast, niclosamide acts on

LRP6 by blocking its phosphorylation and downregulating its protein

synthesis. In BC cell models, niclosamide inhibits cellular

proliferation and promotes apoptosis without affecting DVL2

expression (213,214). Research on BC cells has

confirmed that niclosamide could inhibit tumor sphere formation in

non-obese diabetes/severe combined immunodeficiency mice, promote

apoptosis and effectively curb tumor growth, providing support for

its application in CSC-directed therapy (215). Furthermore, using a mouse BC

model, Ye et al (216)

reported that niclosamide decreases tumor cell proliferation,

migration and invasion, while promoting apoptosis and decreasing

tumor weight. These findings demonstrate the mechanisms of action

of LRP5/6 inhibitors and provide insights for BC treatment

strategies.

Vantictumab is a fully human IgG2 monoclonal

antibody that selectively targets frizzled receptors and

effectively disrupts the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (217). Preclinical experiments involving

human cancer cell cultures and patient-derived BC xenograft models

have shown that vantictumab not only impedes tumor progression but

also exhibits enhanced antitumor efficacy when combined with

paclitaxel compared to monotherapy (217,218). Sequential treatment with

vantictumab and paclitaxel induces mitotic cell death, decreases

tumor proliferation and decreases CSC numbers. Vantictumab

decreases the number of CSCs and downregulates the expression of

EMT-associated genes (219).

Tankyrase regulates Axin stability and directs its

degradation through PARsylation (220). In a BC cell culture, XAV939 or

small interfering RNA-mediated tankyrase knockdown significantly

increases the expression of Axin1 and Axin2 proteins, thereby

inhibiting Wnt-induced transcriptional activity (221). Tankyrase inhibitor MSC2504877

exerts G1 phase cell cycle arrest effects in tumor cells, promotes

cellular senescence and enhances the efficacy of clinically used

CDK4/6 inhibitors, facilitating development of BC treatment

(222).

Natural products are used for the development of

anticancer drugs. The use of these naturally derived compounds and

their derivatives to modulate the TME and target the Wnt signaling

pathway is becoming a highly promising direction in BC treatment

(223-225). Phytochemicals regulate the Wnt

signaling cascade, thereby providing options for future drug

development (Table I).

BC, which poses a threat to lives and safety, has

long been a core focus of medical research and clinical practice

(226,227). The biological research system of

BC is intricate, and the multidimensional network constructed

between the Wnt signaling pathway and TME forms a cornerstone in

this field of study (228-230). The components of the TME are

associated with the Wnt signaling pathway, creating dynamic

regulatory network. Immune cells releasing cytokines to regulate

Wnt signaling, stromal components influencing signal transmission

through chemical induction and secreted molecules directly

interacting with key proteins in the pathway affect the

proliferation, migration and invasion of tumor cells, and serve a

role in promoting immune evasion, metabolic reprogramming and

enhancing therapeutic resistance (231,232).

The hallmark features of the TME, such as hypoxia,

acidity and mechanical stress, are associated with the Wnt

signaling pathway, promoting the continuous progression of tumors

(233,234). The Wnt signaling pathway

interacts with key signaling networks, such as TGF-β, PI3K/Akt, FGF

and Hedgehog, forming a highly interconnected regulatory pattern.

Therefore, single-target treatment strategies for the Wnt signaling

pathway may be insufficient to inhibit development of tumors.

Therefore, developing combination treatment plans that act on

multiple key nodes in these signaling networks is key for more

effective treatment.

Given the role of the Wnt signaling pathway in the

heterogeneous microenvironment of BC and its association with

treatment resistance, it has become a key target for identifying

novel biomarkers (14,235). By exploring the effector

molecules of the Wnt signaling pathway and the association between

Wnt signaling activity and patient prognosis, more precise

predictive biomarkers can be developed (236,237). For example, cyclin D1 is

upregulated following activation of the Wnt pathway and may promote

the proliferation of BC cells (238). Ras GTPase-activating

protein-binding protein 1 (G3BP1) induces β-catenin by inactivating

GSK-3β, thereby increasing the proliferation of BC cells. Blocking

the interaction between G3BP1 and GSK-3β inhibits cell

proliferation (239).

Platelet-activating factor, a co-factor of β-catenin, can induce

Wnt signaling, promote the proliferation of BC cells and increase

the expression levels of CSC markers (240,241). The downregulation of

autophagy-related protein 4A leads to decreased expression of

β-catenin, cyclin D1 and MYC proto-oncogene protein c-Myc, which

impacts the autophagy process and enhances the chemosensitivity of

tamoxifen in BC. Deficiency of fibrous sheath interacting protein 1

promotes autophagy, resulting in decreased Wnt/β-catenin activity

and influencing drug sensitivity in TNBC (242). Kallistatin, a tissue

kallikrein-binding protein and a unique serine proteinase

inhibitor, inhibits the proliferation, migration, invasion, and

tumor progression of BC cells by blocking the Wnt/β-catenin

signaling pathway and inducing autophagy (243). Additionally, the genetic

background of patients, such as the mutation status of BRCA1/2, may

influence Wnt signaling activity, thereby providing a basis for the

development of personalized treatment strategies.

In studies exploring the relationship between the

Wnt signaling pathway and tumor cell death, it has been confirmed

that the Wnt signaling pathway is not only closely related to the

apoptosis and autophagy processes of breast cancer cells, but also

associated with disulfidptosis, a specific type of cell death

caused by disulfide accumulation (244,245). Wnt signaling activation not only

promotes tumor cell self-renewal but also modulates serine

peptidase inhibitor, clade B, member 6B (SERPINB6B) to decrease

immune cell death and interfere with T cell-mediated tumor lysis

(246). Specifically, SERPINB6B

suppresses pyroptosis and immune recognition, thereby inhibiting

apoptosis of immunogenic cells at metastatic sites and facilitating

tumor dissemination (246).

However, knowledge gaps persist in the context of the BC TME,

particularly regarding the interaction between Wnt signaling and

other tumor cell death modalities such as disulfidptosis,

ferroptosis, autophagy and pyroptosis. Future studies should

integrate multidisciplinary approaches, including genomics,

proteomics, bioinformatics, high-throughput screening technology

and precision medicine strategies, to systematically investigate

the crosstalk between Wnt signaling and tumor cell death mechanisms

and identify novel therapeutic targets and clinically actionable

biomarkers.

Small-molecule inhibitors and natural compounds

regulate Wnt pathway activity, effectively inhibiting the

proliferation and migration of tumor cells, while accelerating

apoptosis (247). Existing

research indicates that these inhibitors and compounds may have

clinical translation and application potential in BC (49). However, despite scientific

advancements, the pace of clinical translation is slow, with most

Wnt pathway-targeting drugs in phase I clinical trials, constrained

by thorough safety validation and preliminary efficacy assessment,

and only a few advancing to phase III trials (Table II) (248-250). The clinical safety and efficacy

of Wnt-targeting small molecules and natural compounds must be

validated to confirm their therapeutic potential where toxicity

poses a barrier. For example, salinomycin carries the risk of

neurotoxicity, potentially inducing peripheral neuropathy, whereas

niclosamide is associated with dose-limiting toxicity, posing a

threat to the gastrointestinal system (251,252). Future research should focus on

enhancing the clinical safety and efficacy of these compounds,

which may be achieved through the optimization of chemical

structures or development of innovative drug delivery technology to

enhance bioavailability and reduce adverse reactions (253). This may provide more effective

and safer treatment options for patients with BC and improve

prognosis and overall quality of life.

Not applicable.

CS and RL conceived and designed the study. MS and

HZ wrote and edited the manuscript, constructed the figures and

performed the literature review. YYu, YYa and HL revised the

manuscript. FF and QW constructed figures. All the authors have

read and approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China Key Project (grant no. 82430123), National

Natural Science Foundation of China General Program (grant no.

82174222), Science and Technology Cooperation Project of the

Department of Science and Technology of the Traditional Chinese

Medicine Administration (grant no. GZY-KJS-SD-2023-023), National

Major Scientific and Technological Special Project for the

Prevention and Treatment of Cancer, Cardio-cerebrovascular,

Respiratory, and Metabolic Diseases (grant no. 2024ZD0521406) and

Shandong Province Taishan Scholar Distinguished Expert Reward

Program (grant no. tstp20221166).

|

1

|

Kim J, Harper A, McCormack V, Sung H,

Houssami N, Morgan E, Mutebi M, Garvey G, Soerjomataram I and

Fidler-Benaoudia MM: Global patterns and trends in breast cancer

incidence and mortality across 185 countries. Nat Med. Feb

24–2025.Epub ahead of print.

|

|

2

|

Scholler N, Perbost R, Locke FL, Jain MD,

Turcan S, Danan C, Chang EC, Neelapu SS, Miklos DB, Jacobson CA, et

al: Tumor immune contexture is a determinant of anti-CD19 CAR T

cell efficacy in large B cell lymphoma. Nat Med. 28:1872–1882.

2022.

|

|

3

|

Yu T and Di G: Role of tumor

microenvironment in triple-negative breast cancer and its

prognostic significance. Chin J Cancer Res. 29:237–252. 2017.

|

|

4

|

Rodríguez-Bejarano OH, Parra-López C and

Patarroyo MA: A review concerning the breast cancer-related tumour

microenvironment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 199:1043892024.

|

|

5

|

Park J, Hsueh PC, Li Z and Ho PC:

Microenvironment-driven metabolic adaptations guiding CD8+ T cell

anti-tumor immunity. Immunity. 56:32–42. 2023.

|

|

6

|

Mao X, Xu J, Wang W, Liang C, Hua J, Liu

J, Zhang B, Meng Q, Yu X and Shi S: Crosstalk between

cancer-associated fibroblasts and immune cells in the tumor

microenvironment: new findings and future perspectives. Mol Cancer.

20:1312021.

|

|

7

|

Christofides A, Strauss L, Yeo A, Cao C,

Charest A and Boussiotis VA: The complex role of tumor-infiltrating

macrophages. Nat Immunol. 23:1148–1156. 2022.

|

|

8

|

Soleas JP, D'Arcangelo E, Huang L, Karoubi

G, Nostro MC, McGuigan AP and Waddell TK: Assembly of lung

progenitors into developmentally-inspired geometry drives

differentiation via cellular tension. Biomaterials.

254:1201282020.

|

|

9

|

Salik B, Yi H, Hassan N, Santiappillai N,

Vick B, Connerty P, Duly A, Trahair T, Woo AJ, Beck D, et al:

Targeting RSPO3-LGR4 signaling for leukemia stem cell eradication

in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 38:263–278.e6. 2020.

|

|

10

|

Choi BR, Cave C, Na CH and Sockanathan S:

GDE2-Dependent activation of canonical wnt signaling in neurons

regulates oligodendrocyte maturation. Cell Rep. 31:1075402020.

|

|

11

|

Zhuang X, Zhang H, Li X, Li X, Cong M,

Peng F, Yu J, Zhang X, Yang Q and Hu G: Differential effects on

lung and bone metastasis of breast cancer by Wnt signalling

inhibitor DKK1. Nat Cell Biol. 19:1274–1285. 2017.

|

|

12

|

Krishnamurthy N and Kurzrock R: Targeting

the Wnt/betacatenin pathway in cancer: Update on effectors and

inhibitors. Cancer Treat Rev. 62:50–60. 2018.

|

|

13

|

Wend P, Runke S, Wend K, Anchondo B,

Yesayan M, Jardon M, Hardie N, Loddenkemper C, Ulasov I, Lesniak

MS, et al: WNT10B/β-catenin signalling induces HMGA2 and

proliferation in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. EMBO Mol

Med. 5:264–279. 2013.

|

|

14

|

Zhu L, Tian Q, Gao H, Wu K, Wang B, Ge G,

Jiang S, Wang K, Zhou C, He J, et al: PROX1 promotes breast cancer

invasion and metastasis through WNT/β-catenin pathway via

interacting with hnRNPK. Int J Biol Sci. 18:2032–2046. 2022.

|

|

15

|

Teng Y, Mei Y, Hawthorn L and Cowell JK:

WASF3 regulates miR-200 inactivation by ZEB1 through suppression of

KISS1 leading to increased invasiveness in breast cancer cells.

Oncogene. 33:203–211. 2014.

|

|

16

|

Mortezaee K: WNT/β-catenin regulatory

roles on PD-(L)1 and immunotherapy responses. Clin Exp Med.

24:152024.

|

|

17

|

Wang L, Zhang L, Zhao L, Shao S, Ning Q,

Jing X, Zhang Y, Zhao F, Liu X, Gu S, et al: VEGFA/NRP-1/GAPVD1

axis promotes progression and cancer stemness of triple-negative

breast cancer by enhancing tumor cell-macrophage crosstalk. Int J

Biol Sci. 20:446–463. 2024.

|

|

18

|

Foldynová-Trantírková S, Sekyrová P,

Tmejová K, Brumovská E, Bernatík O, Blankenfeldt W, Krejcí P,

Kozubík A, Dolezal T, Trantírek L and Bryja V: Breast

cancer-specific mutations in CK1epsilon inhibit Wnt/beta-catenin

and activate the Wnt/Rac1/JNK and NFAT pathways to decrease cell

adhesion and promote cell migration. Breast Cancer Res.

12:R302010.

|

|

19

|

Zhou Y, Xu J, Luo H, Meng X, Chen M and

Zhu D: Wnt signaling pathway in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett.

525:84–96. 2022.

|

|

20

|

Liao Y, Badmann S, Kraus F, Topalov NE,

Mayr D, Kolben T, Hester A, Beyer S, Mahner S, Jeschke U, et al:

PLA2G7/PAF-AH as potential negative regulator of the wnt signaling

pathway mediates protective effects in BRCA1 mutant breast cancer.

Int J Mol Sci. 24:8822023.

|

|

21

|

Liu L, Xiao B, Hirukawa A, Smith HW, Zuo

D, Sanguin-Gendreau V, McCaffrey L, Nam AJ and Muller WJ: Ezh2

promotes mammary tumor initiation through epigenetic regulation of

the Wnt and mTORC1 signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

120:e23030101202023.

|

|

22

|

Wu F, Yang J, Liu J, Wang Y, Mu J, Zeng Q,

Deng S and Zhou H: Signaling pathways in cancer-associated

fibroblasts and targeted therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct

Target Ther. 6:2182021.

|

|

23

|

Song P, Gao Z, Bao Y, Chen L, Huang Y, Liu

Y, Dong Q and Wei X: Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in

carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. J Hematol Oncol. 17:462024.

|

|

24

|

Liu Y, Zhao C, Wang G, Chen J, Ju S, Huang

J and Wang X: SNORD1C maintains stemness and 5-FU resistance by

activation of Wnt signaling pathway in colorectal cancer. Cell

Death Discov. 8:2002022.

|

|

25

|

Wei B, Cao J, Tian JH, Yu CY, Huang Q, Yu

JJ, Ma R, Wang J, Xu F and Wang LB: Mortalin maintains breast

cancer stem cells stemness via activation of Wnt/GSK3β/β-catenin

signaling pathway. Am J Cancer Res. 11:2696–2716. 2021.

|

|

26

|

Zhao H, Ming T, Tang S, Ren S, Yang H, Liu

M, Tao Q and Xu H: Wnt signaling in colorectal cancer: Pathogenic

role and therapeutic target. Mol Cancer. 21:1442022.

|

|

27

|

Wang Y, Zheng L, Shang W, Yang Z, Li T,

Liu F, Shao W, Lv L, Chai L, Qu L, et al: Wnt/beta-catenin

signaling confers ferroptosis resistance by targeting GPX4 in

gastric cancer. Cell Death Differ. 29:2190–2202. 2022.

|

|

28

|

Wei L, Ding L, Mo MS, Lei M, Zhang L, Chen

K and Xu P: Wnt3a protects SH-SY5Y cells against 6-hydroxydopamine

toxicity by restoration of mitochondria function. Transl

Neurodegener. 4:112015.

|

|

29

|

Lin TY, Tsai MC, Tu W, Yeh HC, Wang SC,

Huang SP and Li CY: Role of the NLRP3 inflammasome: Insights into

cancer hallmarks. Front Immunol. 11:6104922021.

|

|

30

|

Zhang Y and Wang X: Targeting the

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in cancer. J Hematol Oncol.

13:1652020.

|

|

31

|

Rim EY, Clevers H and Nusse R: The wnt

pathway: From signaling mechanisms to synthetic modulators. Annu

Rev Biochem. 91:571–598. 2022.

|

|

32

|

Katoh M and Katoh M: WNT signaling and

cancer stemness. Essays Biochem. 66:319–331. 2022.

|

|

33

|

Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang

X, Zhou Z, Shu G and Yin G: Wnt/β-catenin signalling: function,

biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 7:32022.

|

|

34

|

Ozalp O, Cark O, Azbazdar Y, Haykir B,

Cucun G, Kucukaylak I, Alkan-Yesilyurt G, Sezgin E and Ozhan G:

Nradd acts as a negative feedback regulator of Wnt/β-Catenin

signaling and promotes apoptosis. Biomolecules. 11:1002021.

|

|

35

|

Duchartre Y, Kim YM and Kahn M: The Wnt

signaling pathway in cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 99:141–149.

2016.

|

|

36

|

Gao Y, Chen N, Fu Z and Zhang Q: Progress

of wnt signaling pathway in osteoporosis. Biomolecules.

13:4832023.

|

|

37

|

Malla RR and Kiran P: Tumor

microenvironment pathways: Cross regulation in breast cancer

metastasis. Genes Dis. 9:310–324. 2020.

|

|

38

|

Yang Y, Ye YC, Chen Y, Zhao JL, Gao CC,

Han H, Liu WC and Qin HY: Crosstalk between hepatic tumor cells and

macrophages via Wnt/β-catenin signaling promotes M2-like macrophage

polarization and reinforces tumor malignant behaviors. Cell Death

Dis. 9:7932018.

|

|

39

|

Jiang Y, Han Q, Zhao H and Zhang J:

Promotion of epithelial-mesenchymal transformation by

hepatocellular carcinoma-educated macrophages through

Wnt2b/β-catenin/c-Myc signaling and reprogramming glycolysis. J Exp

Clin Cancer Res. 40:132021.

|

|

40

|

Tigue ML, Loberg MA, Goettel JA, Weiss WA,

Lee E and Weiss VL: Wnt signaling in the phenotype and function of

tumor-associated macrophages. Cancer Res. 83:3–11. 2023.

|

|

41

|

Bergenfelz C, Medrek C, Ekström E,

Jirström K, Janols H, Wullt M, Bredberg A and Leandersson K: Wnt5a

induces a tolerogenic phenotype of macrophages in sepsis and breast

cancer patients. J Immunol. 188:5448–5458. 2012.

|

|

42

|

Liu Q, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Wei C, Song

J, Lin X, Dou R, Bai J, Xiang Z, et al: Wnt5a-induced M2

polarization of tumor-associated macrophages via IL-10 promotes

colorectal cancer progression. Cell Commun Signal. 18:512020.

|

|

43

|

van Amerongen R: Alternative Wnt pathways

and receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 4:a0079142012.

|

|

44

|

Spranger S and Gajewski TF: A new paradigm

for tumor immune escape: β-catenin-driven immune exclusion. J

Immunother Cancer. 3:432015.

|

|

45

|

Zebley CC, Zehn D, Gottschalk S and Chi H:

T cell dysfunction and therapeutic intervention in cancer. Nat

Immunol. 25:1344–1354. 2024.

|

|

46

|

Ying J, Li H, Yu J, Ng KM, Poon FF, Wong

SC, Chan AT, Sung JJ and Tao Q: WNT5A exhibits tumor-suppressive

activity through antagonizing the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling, and

is frequently methylated in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

14:55–61. 2008.

|

|

47

|

Muto S, Enta A, Maruya Y, Inomata S,

Yamaguchi H, Mine H, Takagi H, Ozaki Y, Watanabe M, Inoue T, et al:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling and resistance to immune checkpoint

inhibitors: From non-small-cell lung cancer to other cancers.

Biomedicines. 11:1902023.

|

|

48

|

Li Q, Wei S, Li Y, Wu F, Qin X, Li Z, Li J

and Chen C: Blocking of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)

expressed on endothelial cells promoted the recruitment of

CD8+IFN-γ+ T cells in atherosclerosis. Inflamm Res. 72:783–796.

2023.

|

|

49

|

Xu X, Zhang M, Xu F and Jiang S: Wnt

signaling in breast cancer: Biological mechanisms, challenges and

opportunities. Mol Cancer. 19:1652020.

|

|

50

|

Wherry EJ and Kurachi M: Molecular and

cellular insights into T cell exhaustion. Nat Rev Immunol.

15:486–499. 2015.

|

|

51

|

Rasha F, Boligala GP, Yang MV,

Martinez-Marin D, Castro-Piedras I, Furr K, Snitman A, Khan SY,

Brandi L, Castro M, et al: Dishevelled 2 regulates cancer cell

proliferation and T cell mediated immunity in HER2-positive breast

cancer. BMC Cancer. 23:1722023.

|

|

52

|

Yang M, Wei Z, Feng M, Zhu Y, Chen Y and

Zhu D: Pharmacological inhibition and genetic knockdown of BCL9

modulate the cellular landscape of cancer-associated fibroblasts in

the tumor-immune microenvironment of colorectal cancer. Front

Oncol. 11:6035562021.

|

|

53

|

Gattinoni L, Zhong XS, Palmer DC, Ji Y,

Hinrichs CS, Yu Z, Wrzesinski C, Boni A, Cassard L, Garvin LM, et

al: Wnt signaling arrests effector T cell differentiation and

generates CD8+ memory stem cells. Nat Med. 15:808–813. 2009.

|

|

54

|

Shan F, Somasundaram A, Bruno TC, Workman

CJ and Vignali DAA: Therapeutic targeting of regulatory T cells in

cancer. Trends Cancer. 8:944–961. 2022.

|

|

55

|

Hong Y, Manoharan I, Suryawanshi A,

Majumdar T, Angus-Hill ML, Koni PA, Manicassamy B, Mellor AL, Munn

DH and Manicassamy S: β-catenin promotes regulatory T-cell

responses in tumors by inducing vitamin A metabolism in dendritic

cells. Cancer Res. 75:656–665. 2015.

|

|

56

|

van Loosdregt J, Fleskens V, Tiemessen MM,

Mokry M, van Boxtel R, Meerding J, Pals CE, Kurek D, Baert MR,

Delemarre EM, et al: Canonical wnt signaling negatively modulates

regulatory T cell function. Immunity. 39:298–310. 2013.

|

|

57

|

Yang ZY, Zhang WL, Jiang CW and Sun G:

PCBP1-mediated regulation of WNT signaling is critical for breast

tumorigenesis. Cell Biol Toxicol. 39:2331–2343. 2023.

|

|

58

|

Trotter TN, Dagotto CE, Serra D, Wang T,

Yang X, Acharya CR, Wei J, Lei G, Lyerly HK and Hartman ZC: Dormant

tumors circumvent tumor-specific adaptive immunity by establishing

a Treg-dominated niche via DKK3. JCI Insight. 8:e1744582023.

|

|

59

|

Ding Y, Shen S, Lino AC, Curotto de

Lafaille MA and Lafaille JJ: Beta-catenin stabilization extends

regulatory T cell survival and induces anergy in nonregulatory T

cells. Nat Med. 14:162–169. 2008.

|

|

60

|

Dai W, Liu F, Li C, Lu Y, Lu X, Du S, Chen

Y, Weng D and Chen J: Blockade of Wnt/β-catenin pathway aggravated

silica-induced lung inflammation through tregs regulation on Th

immune responses. Mediators Inflamm. 2016:62356142016.

|

|

61

|

Gunaydin G: CAFs interacting With TAMs in

tumor microenvironment to enhance tumorigenesis and immune evasion.

Front Oncol. 11:6683492021.

|

|

62

|

Hu D, Li Z, Zheng B, Lin X, Pan Y, Gong P,

Zhuo W, Hu Y, Chen C, Chen L, et al: Cancer-associated fibroblasts

in breast cancer: Challenges and opportunities. Cancer Commun

(Lond). 42:401–434. 2022.

|

|

63

|

Xie J, Qi X, Wang Y, Yin X, Xu W, Han S,

Cai Y and Han W: Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete

hypoxia-induced serglycin to promote head and neck squamous cell

carcinoma tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo by activating the

Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 44:661–671. 2021.

|

|

64

|

Aizawa T, Karasawa H, Funayama R, Shirota

M, Suzuki T, Maeda S, Suzuki H, Yamamura A, Naitoh T, Nakayama K

and Unno M: Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete Wnt2 to promote

cancer progression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 8:6370–6382.

2019.

|

|

65

|

Bochet L, Lehuédé C, Dauvillier S, Wang

YY, Dirat B, Laurent V, Dray C, Guiet R, Maridonneau-Parini I, Le

Gonidec S, et al: Adipocyte-derived fibroblasts promote tumor

progression and contribute to the desmoplastic reaction in breast

cancer. Cancer Res. 73:5657–5668. 2013.

|

|

66

|

Chen Y, Zeng C, Zhan Y, Wang H, Jiang X

and Li W: Aberrant low expression of p85α in stromal fibroblasts

promotes breast cancer cell metastasis through exosome-mediated

paracrine Wnt10b. Oncogene. 36:4692–4705. 2017.

|

|

67

|

Liu J, Shen JX, Wu HT, Li XL, Wen XF, Du

CW and Zhang GJ: Collagen 1A1 (COL1A1) promotes metastasis of

breast cancer and is a potential therapeutic target. Discov Med.

25:211–223. 2018.

|

|

68

|

Kim SH, Lee HY, Jung SP, Kim S, Lee JE,

Nam SJ and Bae JW: Role of secreted type I collagen derived from

stromal cells in two breast cancer cell lines. Oncol Lett.

8:507–512. 2014.

|

|

69

|

Luga V, Zhang L, Viloria-Petit AM,

Ogunjimi AA, Inanlou MR, Chiu E, Buchanan M, Hosein AN, Basik M and

Wrana JL: Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine

Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell.

151:1542–1556. 2012.

|

|

70

|

Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I,

Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A,

Prockop Dj and Horwitz E: Minimal criteria for defining multipotent

mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular

Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 8:315–317. 2006.

|

|

71

|

Cuiffo BG and Karnoub AE: Mesenchymal stem

cells in tumor development: Emerging roles and concepts. Cell Adh

Migr. 6:220–230. 2012.

|

|

72

|

Liang W and Chen X, Zhang S, Fang J, Chen

M, Xu Y and Chen X: Mesenchymal stem cells as a double-edged sword

in tumor growth: Focusing on MSC-derived cytokines. Cell Mol Biol

Lett. 26:32021.

|

|

73

|

Sun Z, Wang S and Zhao RC: The roles of

mesenchymal stem cells in tumor inflammatory microenvironment. J

Hematol Oncol. 7:142014.

|

|

74

|

Shi Y, Du L, Lin L and Wang Y:

Tumour-associated mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: Emerging

therapeutic targets. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 16:35–52. 2017.

|

|

75

|

Kar S, Jasuja H, Katti DR and Katti KS:

Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regulates osteogenesis for breast

cancer bone metastasis: Experiments in an in vitro nanoclay

scaffold cancer testbed. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 6:2600–2611.

2020.

|

|

76

|

Arrigoni C, De Luca P, Gilardi M, Previdi

S, Broggini M and Moretti M: Direct but not indirect co-culture

with osteogenically differentiated human bone marrow stromal cells

increases RANKL/OPG ratio in human breast cancer cells generating

bone metastases. Mol Cancer. 13:2382014.

|

|

77

|

Qiao L, Xu ZL, Zhao TJ, Ye LH and Zhang

XD: Dkk-1 secreted by mesenchymal stem cells inhibits growth of

breast cancer cells via depression of Wnt signalling. Cancer Lett.

269:67–77. 2008.

|

|

78

|

Qiao L, Xu Z, Zhao T, Zhao Z, Shi M, Zhao

RC, Ye L and Zhang X: Suppression of tumorigenesis by human

mesenchymal stem cells in a hepatoma model. Cell Res. 18:500–507.

2008.

|

|

79

|

Khakoo AY, Pati S, Anderson SA, Reid W,

Elshal MF, Rovira II, Nguyen AT, Malide D, Combs CA, Hall G, et al:

Human mesenchymal stem cells exert potent antitumorigenic effects

in a model of Kaposi's sarcoma. J Exp Med. 203:1235–1247. 2006.

|

|

80

|

Dasari VR, Velpula KK, Kaur K, Fassett D,

Klopfenstein JD, Dinh DH, Gujrati M and Rao JS: Cord blood stem

cell-mediated induction of apoptosis in glioma downregulates

X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP). PLoS One.

5:e118132010.

|

|

81

|

Otsu K, Das S, Houser SD, Quadri SK,

Bhattacharya S and Bhattacharya J: Concentration-dependent

inhibition of angiogenesis by mesenchymal stem cells. Blood.

113:4197–4205. 2009.

|

|

82

|

Zhu Y, Sun Z, Han Q, Liao L, Wang J, Bian

C, Li J, Yan X, Liu Y, Shao C and Zhao RC: Human mesenchymal stem

cells inhibit cancer cell proliferation by secreting DKK-1.

Leukemia. 23:925–933. 2009.

|

|

83

|

Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R and

Vallée JN: Interactions between TGF-β1, canonical WNT/β-catenin

pathway and PPAR γ in radiation-induced fibrosis. Oncotarget.

8:90579–90604. 2017.

|

|

84

|

Patel SA, Nilsson MB, Le X, Cascone T,

Jain RK and Heymach JV: Molecular mechanisms and future

implications of VEGF/VEGFR in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res.

29:30–39. 2023.

|

|

85

|

Zerlin M, Julius MA and Kitajewski J:

Wnt/Frizzled signaling in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 11:63–69.

2008.

|

|

86

|

Mankuzhy P, Dharmarajan A, Perumalsamy LR,

Sharun K, Samji P and Dilley RJ: The role of Wnt signaling in

mesenchymal stromal cell-driven angiogenesis. Tissue Cell.

85:1022402023.

|

|

87

|

Xie W, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wang F, Zhang K,

Huang Y, Zhou Z, Huang G and Wang J: Oxymatrine enhanced anti-tumor

effects of Bevacizumab against triple-negative breast cancer via

abating Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway. Am J Cancer Res.

9:1796–1814. 2019.

|

|

88

|

Pagani E, Ruffini F, Antonini Cappellini

GC, Scoppola A, Fortes C, Marchetti P, Graziani G, D'Atri S and

Lacal PM: Placenta growth factor and neuropilin-1 collaborate in

promoting melanoma aggressiveness. Int J Oncol. 48:1581–1589.

2016.

|

|

89

|

Ruffini F, D'Atri S and Lacal PM:

Neuropilin-1 expression promotes invasiveness of melanoma cells

through vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2-dependent and

-independent mechanisms. Int J Oncol. 43:297–306. 2013.

|

|

90

|

Nilsson LM, Nilsson-Ohman J, Zetterqvist

AV and Gomez MF: Nuclear factor of activated T-cells transcription

factors in the vasculature: The good guys or the bad guys? Curr

Opin Lipidol. 19:483–490. 2008.

|

|

91

|

Reis M and Liebner S: Wnt signaling in the

vasculature. Exp Cell Res. 319:1317–1323. 2013.

|

|

92

|

Roma-Rodrigues C, Fernandes AR and

Baptista PV: Exosome in tumour microenvironment: Overview of the