Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (BCL) (DLBCL) is the

most common subtype of non-Hodgkin lymphoma, accounting for 30-40%

of all non-Hodgkin lymphoma cases (1). Although the majority of DLBCL cases

are primary, DLBCL can also transform from various indolent

lymphomas. For example, 6.78% of splenic marginal zone lymphomas,

5.55% of follicular lymphomas, 4.05% of nodal marginal zone

lymphomas, 2.22% of lymphoplasmacytic lymphomas/Waldenström's

macroglobulinemias and 1.62% of extra-nodal marginal zone lymphomas

developed into DLBCL (2). Based

on gene expression profiles, DLBCL can be classified into various

subgroups, namely activated B-cell, germinal center B-cell and

unclassified, with each exhibiting a distinct response to treatment

(3). The rituximab

(R)-cyclophosphamide doxorubicin vincristine prednisolone (R-CHOP)

regimen, which includes a monoclonal antibody targeting CD20,

represents an advancement in the initial treatment of patients with

DLBCL (4,5). This regimen has improved the 10-year

progression-free survival (PFS) rate of patients with DLBCL from 20

to 36.5% (6), and the 5-year

overall survival (OS) rate from ~50% to 60-70% (7). However, despite this advancement,

>40% of patients with DLBCL treated with R-CHOP or R-CHOP-like

regimens will experience relapse or refractory disease (5). In addition, the majority of patients

with relapsed or refractory DLBCL will have a shorter survival

period compared with patients without relapsed or refractory

DLBLC.

Previous studies have identified a number of risk

factors for DLBCL, which are outlined in the present review.

Clinical studies indicate that Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis viral infections are

associated with DLBCL development (8-10).

EBV is a cancer-causing virus that is associated with a number of

lymphoproliferative disorders, such as DLBCL and Burkitt's

lymphoma. Furthermore, in individuals that are HIV-positive, the

risk of EBV-associated cancers, including DLBCL, increases due to

weakened immunity (8,9). Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is also

associated with DLBCL, where co-infection with HCV and HIV further

increases the risk of lymphoproliferative disorders due to combined

immunosuppression and chronic inflammation (10). In addition, numerous studies

indicate a positive association between autoimmune diseases, such

as systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren's syndrome, and an

increased risk of DLBCL (11-13). Furthermore, genetic factors are

also considered to serve an important role in the biology and

prognosis of DLBCL, and various studies reveal that DLBCL exhibits

considerable genetic heterogeneity (14,15). The expression and rearrangement of

Myc, Bcl2 and Bcl6 genes are useful for

guiding treatment and predicting the prognosis of DLBCL (16,17). In addition, the tumor

microenvironment (TME) and programmed cell death protein 1

(PD-1)/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) are key factors that

can determine DLBCL treatment outcomes, since they can enable tumor

immune escape, and thus, recurrence or refractory disease (18). Consequently, the management of

DLBCL is currently still challenging.

The influence of dietary nutrients, with a

particular emphasis on vitamin supplementation, in the prevention

and treatment of tumors is gaining interest in the present field of

research. Previous empirical studies reveal that certain vitamins

(vitamin D and E) can exert a substantial effect on tumor

development and progression (19,20). In particular, a number of trials

indicate that high doses of vitamin C (≥1 g/kg) exhibit both direct

and indirect antitumor properties (21-30) (Table

I). As a result, vitamins are regarded as an important agent in

the prevention and therapeutic management of malignancies.

Ascorbic acid (AA), commonly known as vitamin C, is

a water-soluble vitamin with potent antioxidant properties. Vitamin

C is abundant in various fruits and vegetables, with concentrations

differing among species. Citrus and kiwi fruits, mangoes, broccoli,

tomatoes, and peppers have the highest levels of vitamin C

(31). Numerous studies indicate

that high doses of vitamin C (1-4 g/kg) can inhibit tumor cell

proliferation through multiple mechanisms (30,32). These mechanisms include increased

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), activation of specific

epigenetic regulatory factors [tet methylcytosine dioxygenase 2

(TET2)] and modulation of the antitumor immune response to either

directly or indirectly eliminate tumor cells (30,32,33). Furthermore, previous clinical

trials demonstrate that vitamin C treatment has a high level of

safety and tolerability (34,35). The present review investigated the

role of vitamin C in DLBCL and assessed its effects on the various

pathogenic mechanisms of DLBCL. Additionally, the present review

examined the future prospects and challenges associated with

vitamin C-based antitumor therapy.

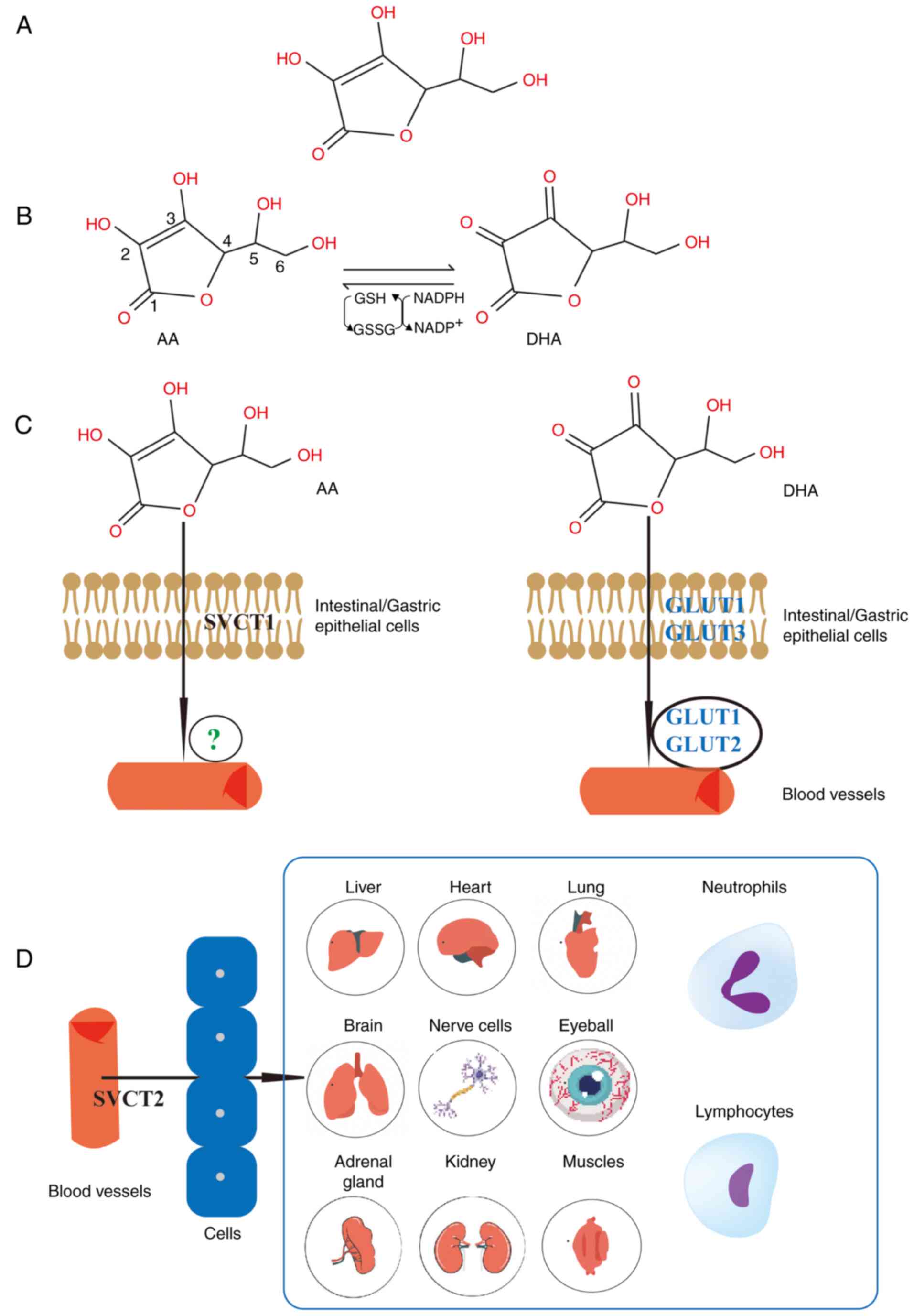

Vitamin C is a weak acid that is comprised of six

carbon atoms and is classified as an α-ketolactone. In the human

body, vitamin C mainly exists in two active forms, dehydroascorbic

acid (DHA) and AA, in an interconvertible manner (Fig. 1A and B) (36). Vitamin C is abundant in a wide

variety of fruits and vegetables and can only be obtained by humans

via ingestion through dietary means, since humans cannot synthesize

it. Following oral intake, vitamin C is primarily absorbed in the

duodenum and upper jejunum, with minimal absorption occurring in

the stomach. It enters the bloodstream through passive and active

transport, facilitating its transmembrane movement (37,38). However, the majority of vitamin C

is absorbed via the sodium-dependent vitamin C transporter (SVCT)1

(39,40). Vitamin C typically moves slowly

across the plasma membrane, even in the presence of a notable

concentration gradient. AA is absorbed in the intestine through

SVCT1 (40), whilst DHA may

undergo transmembrane diffusion and absorption through glucose

transporters (GLUT) (41).

However, the mechanism underlying AA absorption into the

bloodstream is yet to be elucidated (42). Once AA is absorbed into the

bloodstream, it is subsequently transported to various organs

through SVCT2. Vitamin C is widely distributed across various

organs and cells, with particularly high concentrations in the

brain and endocrine glands, such as the pituitary and adrenal

glands (37,43). A schematic diagram illustrating

intestinal vitamin C absorption and distribution is presented in

Fig. 1C and D. However, the

majority of vitamin C entering the body is excreted by the kidneys,

with only a small proportion eliminated through feces (41).

Via the SVCT2, vitamin C accumulates in key organs

and cells, such as the skin, lymphocytes and neutrophils. The skin

serves as the first line of defense for the body. Previous studies

indicate that vitamin C reduces the synthesis and release of

proinflammatory factors, such as IL-1β and TNF-α, by reducing the

transcription of their genes (44,45). Additionally, vitamin C contributes

to the tissue repair processes by promoting collagen synthesis and

maturation, promoting the expression of angiogenic factors (such as

VEGF), enhancing the expression of connective tissue regulators

(such as connective tissue growth factor), increasing fibroblast

activity, and activating important repair enzymes (such as heme

oxygenase 1 and TGF-β) (44-46). In addition, preliminary evidence

suggests that vitamin C can accumulate in neutrophils to an extent.

Following infection, neutrophils can rapidly uptake DHA and convert

it to AA within cells, leading to increases in its concentration.

This concentration increase is calculated to be ~10 mM (36). In vitro and clinical

studies also reveal that vitamin C can enhance the efficacy of

phagocytosis and pathogen killing by promoting neutrophil

chemotaxis (47,48). Lymphocytes, including T and B

cells, are key types of immune cells that utilize SVCT2 for vitamin

C storage. Although the precise mechanism by which vitamin C

regulates lymphocyte physiology remains unclear (49), vitamin C can stimulate lymphocyte

development, differentiation and maturation of immature cells, and

regulate cytokine secretion (36,50,51). Additionally, when vitamin C is

incubated with peripheral blood lymphocytes in vitro, it

reduces the production of various inflammatory cytokines, such as

TNF-α and IFN-γ, induced by lipopolysaccharide, whilst increasing

the production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 (50). Immunoregulatory T cells (Tregs), a

subset of CD4+ T cells, serve an important role in

immune regulation. They serve to prevent the hyperactivation of the

immune system and maintain immune homeostasis. A recent study

demonstrates that TET2 enzymes are important for maintaining a

stable population of Treg cells (52). Vitamin C can enhance the activity

of TET enzymes, suggesting that targeting TET enzymes with vitamin

C may improve the efficacy of Treg cell induction (53).

BCL6 is part of the antiapoptotic protein family and

functions as a transcriptional repressor (77). The germinal center reaction

pathway in mature B cells primarily uses BCL6, which serves an

important role in promoting germinal center formation, regulating

the cell cycle and participating in immune response signaling

transduction. BCL6 inhibits the early activation and

differentiation of germinal center B cells, rendering it an

important regulatory factor for effective humoral immunity

(77). In addition, BCL6 is

indispensable for the development and function of T follicular

helper cells and germinal center B cells (78,79). BCL6 was first identified in DLBCL.

High expression of the BCL6 protein in germinal center B cells

markedly inhibits the expression of the tumor suppressor

p53. The inhibition of p53 enables lymphoma cells to

survive in vivo and inhibits tumor cell apoptosis (78).

As an important tumor suppressor gene, p53 regulates

cell division, prevents DNA mutations and the proliferation of

damaged cells, controls apoptosis, and inhibits tumor formation

(90,91). Additionally, p53 halts the cell

cycle and facilitates DNA repair (92). However, in DLBCL cells, vascular

compression, due to rapid tumor cell proliferation, results in a

hypoxic environment, which subsequently increases the expression of

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1) in tumor cells. However, p53

competes with p300 proteins, which reduces the transcription of

HIF-1α. Under sustained hypoxia, p53 induces the degradation of

HIF-1α and triggers apoptosis, which are both important for

inhibiting tumor growth (93-95). HIF-1 is expressed in most types of

mammalian cell and primarily consists of the oxygen-dependent

HIF-1α and the oxygen-independent HIF-1β. It can regulate the

expression of genes that regulate metastasis, angiogenesis and

tumor cell invasion. In DLBCL, BCL6 primarily inhibits p53, which

in turn inhibits the effects of p53 on cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis. Overexpression of BCL6 reveals reduced wild-type p53

expression levels, resulting in enhanced tumor cell proliferation

and impaired apoptosis (79,96-98).

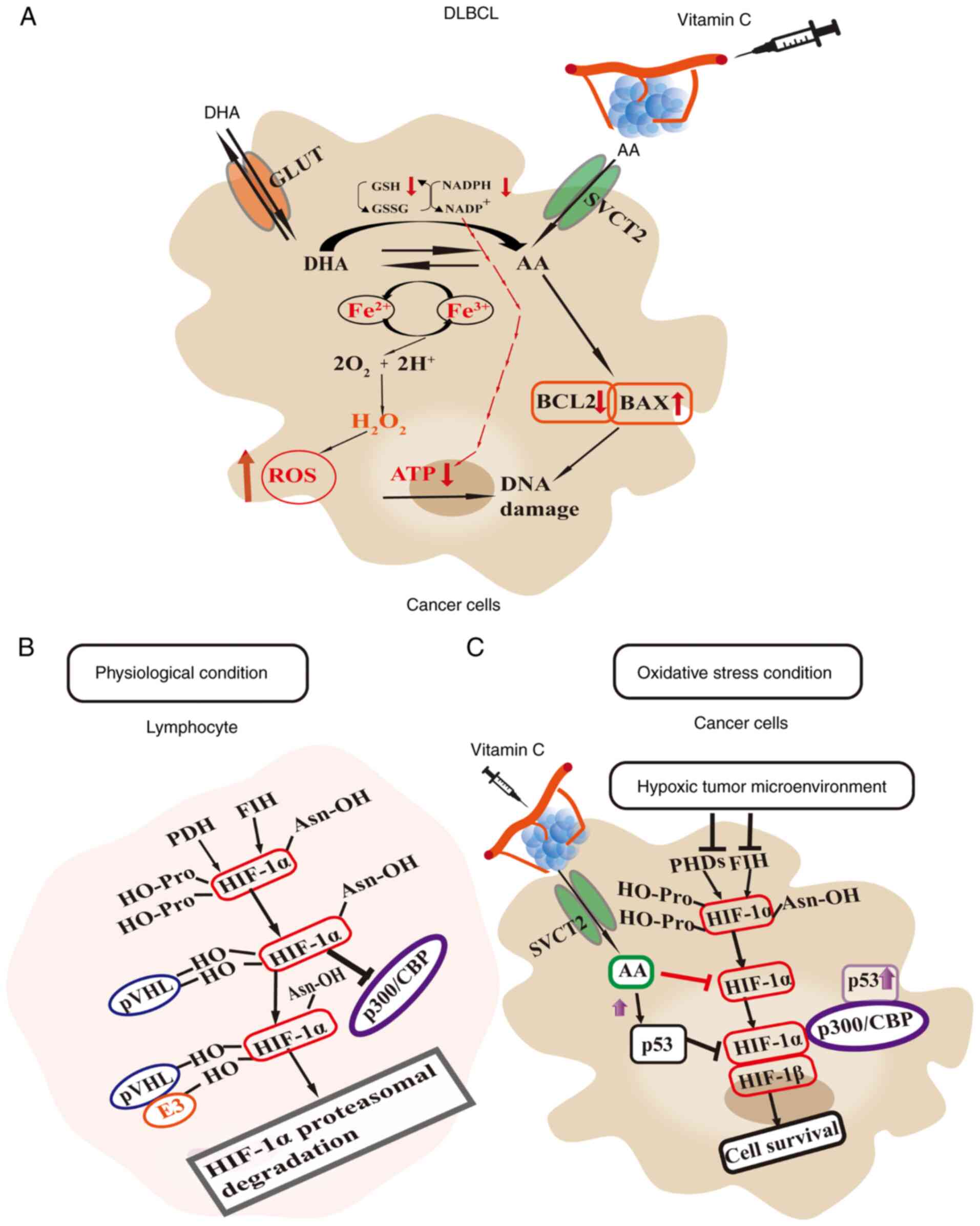

Vitamin C is a natural antioxidant. In normal cells,

its antioxidant properties dominate because it directly reacts with

superoxide anion radicals (O₂−) and hydroxyl radicals

(OH−), which reduces the level of ROS within the cells

(99). In tumor cells, vitamin C

often acts as a pro-oxidant due to high metal ion concentrations in

the cytoplasm of the cell (such as Fe2+), which leads to

oxidative stress due to reactions such as the Fenton reaction. In

addition, cancer cells also have an increased expression of GLUT1,

which enhances the cellular uptake of oxidized vitamin C (DHA).

This depletes the antioxidants such as glutathione, NADPH and

superoxide dismutase, and increases the levels of ROS in the

cytoplasm of the cell (32).

Previous studies indicate that, at pharmacological concentrations,

vitamin C can function as a pro-oxidant, selectively inducing DNA

damage in cancer cells (71-73). This targeting facilitates the

elimination of cancer cells. In cases of breast and cervical

cancer, studies indicate that vitamin C upregulates the expression

of wild-type p53 and inhibits HIF-1α activity, thus inhibiting

tumor development (Fig. 2B and C)

(74,100,101). Additionally, in DLBCL,

pharmacological doses of vitamin C can increase wild type p53

production, indirectly modulating the impact of BCL6

overexpression. Furthermore, vitamin C can also inhibit HIF-1α

activity, promoting apoptosis in tumor cells (102). In conclusion, vitamin C may be a

potential anticancer therapeutic agent.

c-Myc, a proto-oncogene, is located on chromosome

8q24. When overexpressed, c-Myc promotes cancer cells to re-enter

the cell cycle and proliferate, which promotes tumor growth

(111). Numerous studies

demonstrate that the activation of Myc in cancer cells occurs

through multiple mechanisms (112,113). For example, genetic mutations,

chromosomal translocations and genomic amplifications can induce

elevated Myc expression levels. Furthermore, alterations in an

upstream regulatory pathway (such as Wnt/β-catenin) (114) can also increase Myc oncogene

transcription levels. In addition, post-translational modifications

of the Myc protein such as phosphorylation, proteasomal degradation

and ubiquitination enhances its stability, resulting in the

activation of the Myc pathway (115). As demonstrated in a conditional

knockout mouse model, Myc is essential for hematopoietic system

development (116). It regulates

the balance between hematopoietic stem cell self-renewal and

differentiation, and is also highly expressed in proliferating

cells during lymph node development (117). In DLBCL, Myc is the third most

frequently rearranged oncogene after BCL2 and BCL6.

In total, ~15% of newly diagnosed patients with DLBCL have Myc gene

rearrangements, and these patients are frequently associated with

an increased level of tumor cell invasion and a poorer prognosis

(118-120).

Previous studies demonstrate that vitamin C, acting

as a pro-oxidant, increases the levels of ROS, which inhibits the

growth of tumor cells (74,121,122). Previous studies using tumors

such as clear cell renal carcinoma and esophageal cancer suggest

that the accumulation of ROS inhibits the expression of c-Myc,

induces DNA damage and reduces tumor cell proliferation (123,124). Another study reveals that the

combination of vitamin C with a respiratory complex I inhibitor

effectively eradicated c-Myc-overexpressing cells and enhanced

treatment outcomes in human BCL xenografts (125). However, further research is

required to elucidate the effects of vitamin C on human and

hematological tumors. In summary, vitamin C has potential benefits

in cancer treatment and may promote tumor cell apoptosis via the

ROS/c-Myc axis.

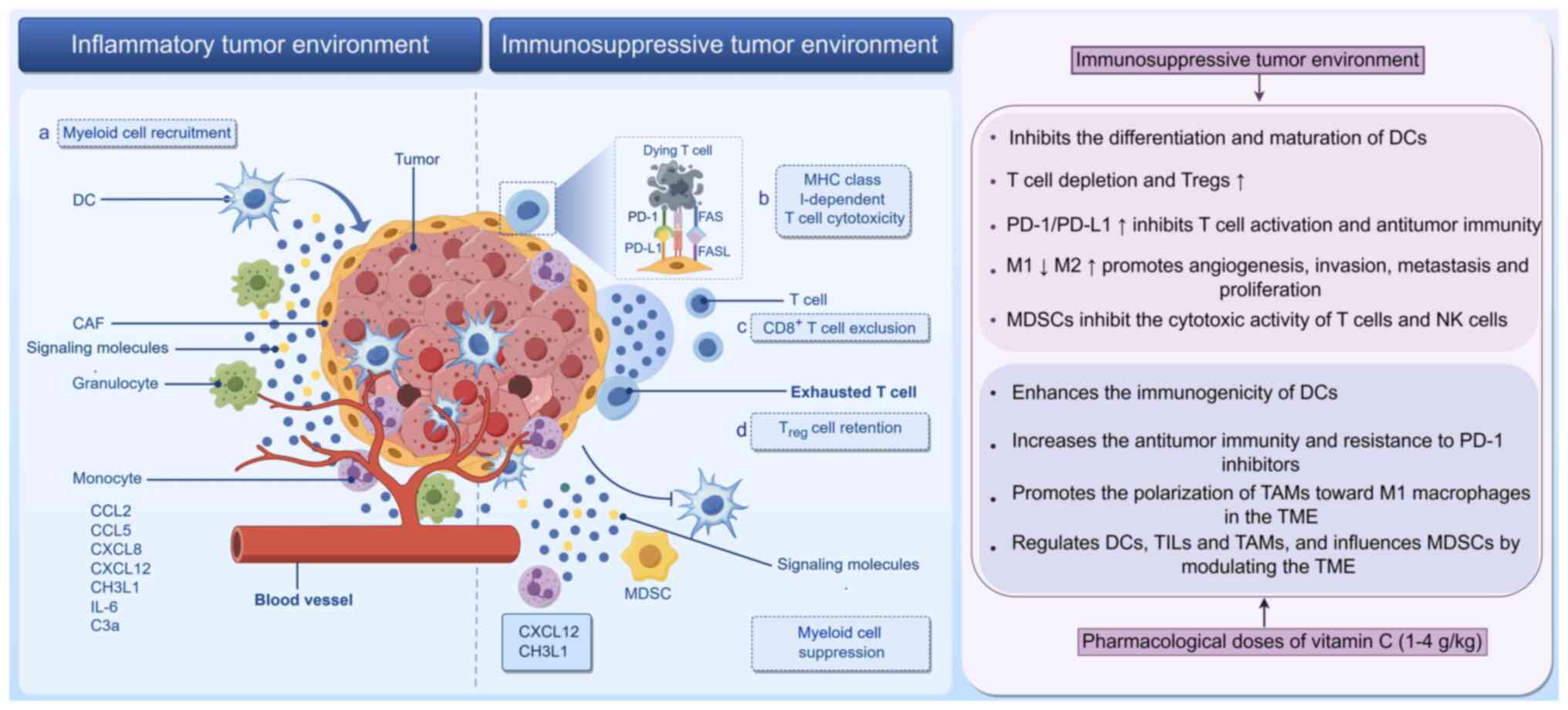

The TME is a dynamic and intricate cellular

landscape in which tumor or cancer stem cells coexist with immune

cells (myeloid and lymphoid), fibroblasts, blood vessels, the

extracellular matrix and a range of signaling molecules (such as

C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 and IL-6) (126,127). A previous study indicates that

the TME is adaptable, continuously altering its characteristics

throughout tumor development and serving a role in regulating

cancer progression (128). For

example, immune cells within the TME transition between antitumor

and protumor states in response to cytokines secreted by the TME.

Cells that suppress the antitumor response include Tregs,

myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and M2 phenotype

tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs; Fig. 3) (129). Numerous studies indicate that

the composition of immune cells in the TME, particularly endogenous

immune cells (such as MDSCs, Tregs and M2 macrophages), is directly

associated with unfavorable tumor treatment outcomes (130-132).

DCs are immune cells that originate from pluripotent

hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. These cells can be

categorized into the classical DC (cDC) and lymphoid DC subtypes,

with the latter known as plasma cell-like DCs (pDCs). cDC1 and

cDC2, two subtypes of cDCs, are differentiated by the abundance of

antigen-presenting molecules on their surfaces. These cells are

highly specialized and proficient in stimulating naive

antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

through the processing and presentation of antigens, including

tumor-associated antigens. This function is critical for the

initiation of an adaptive immune response (133).

Previous studies indicate that DCs serve a role in

the antitumor immune response (134,135). Specifically, cDC1 can recognize

tumors, secrete factors that modulate the TME, present

tumor-associated antigens, activate CD8+ T cell

responses and enhance antitumor immune function (136-138). In addition, cDC2 can activate

the CD4+ T cell response, thereby augmenting the ability

of CD8+ T cells to kill tumor cells (139,140). IFN-I produced by pDCs serves an

important role in the activation of stimulator of IFN response

cGAMP interactor 1, which causes cell cycle arrest, regulates cell

death and promotes the expression of proapoptotic proteins such as

Bax and Bak. This increases the permeability of the mitochondrial

membrane, which releases apoptotic factors such as cytochrome C,

which in turn triggers the caspase cascade, leading to apoptosis

(141). However, the TME in

contrast can inhibit the differentiation and maturation of DCs

(128), resulting in functional

defects in their ability to stimulate T cells and drive antitumor

immune responses, thereby promoting tumor growth (142-144). DC dysfunction occurs in various

types of cancer, including colon cancer and melanoma (145,146), and is associated with a poor

prognosis in patients with advanced-stage cancer (147,148). Consequently, activating DCs in

the TME is advantageous for antitumor therapy, making it a

promising target for immunotherapy.

Tumor growth is typically a slow gradual process,

where the interaction between tumor cells and the immune system can

reshape the immune environment, impacting T cell differentiation

(157). In patients with cancer,

a notable number of T lymphocytes migrate to the tumor site to

attack the malignancy. However, prolonged exposure can lead to

exhaustion, T cell depletion, cytokine production and the reduced

ability to destroy tumor cells (157). Contributing to this, Tregs in

the TME obstruct antitumor effects through various mechanisms,

including the secretion of inhibitory cytokines (such as IL-10 and

TGF-β) to reduce the antigen-presenting ability of DCs, inhibiting

CD8+ T cells from targeting tumor cells and promoting

immune evasion (158-160). This is observed in several types

of solid tumors, including melanoma (161), hepatocellular carcinoma

(162), lymphoma (163) and lung cancer (164).

Numerous studies reveal that the dysfunction of

tumor-infiltrating T cells occurs gradually (165,166). Initially, a population of

tumor-specific T cells is depleted during thymic maturation due to

negative selection, limiting the antigen recognition ability of the

remaining auto/tumor-specific T cells (167). Subsequently, in a

non-inflammatory environment, the lack of innate stimulators (such

as lipopolysaccharide) results in the weak activation of

antigen-presenting cells, leading to the poor activation of

tumor-specific T cells (167).

Finally, the TME induces and maintains T cell hypo-responsiveness

(168). PD-1 is a marker of T

cell failure (164).

Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells express PD-1, which

binds to PD-L1 on tumor cells, resulting in the inhibition of T

cell activation and antitumor immunity. Treg cell-mediated

immunosuppression is associated with the upregulation of PD-1

(169). Currently, PD-1

inhibitors are widely used in the treatment of various tumors (such

as in lung and gastric cancer) and can effectively improve disease

prognosis (170,171).

DLBCL is a prevalent type of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.

Study of the TME in DLBCL is becoming an increasingly popular

research topic in the field of immunotherapeutics. Previous studies

demonstrate immunological dysfunction in TILs and elevated PD-1

expression levels, both of which are associated with poor prognosis

(172,173). Although PD-1 inhibitors (such as

pembrolizumab and nivolumab) do not demonstrate objective remission

rates in DLBCL, PD-1 inhibitors are considered safe, with good

tolerance and promising prospects (174,175). Anti-PD-1 therapy is indicated to

confer notable synergistic effects with vitamin C in a lymphoma

mouse model (30,176,177). Vitamin C boosts antitumor

immunity and improves anti-PD-1 therapy by increasing chemokine

production and TIL (178).

Vitamin C is known to enhance the activation of tumor-specific T

cells by improving the antigen presentation ability of DCs

(152). It also enhances T cell

penetration into the tumor area to increase antitumor efficacy in

combination with anti-PD-1 drugs (179). However, research on the role of

Tregs in the antitumor effects of vitamin C remains warranted.

Macrophages serve a key role in both innate and

adaptive immunity. They are primarily derived from bone

marrow-derived monocytes and their phenotype and function depend on

the surrounding microenvironment. There are two types of

macrophages: Classical activation (M1 macrophages) and alternative

activation (M2 macrophages) (180). In different tissue environments,

macrophages can differentiate into specific subtypes. M1

macrophages function to reduce inflammation, as well as to

phagocytose and kill target cells (181). By contrast, M2 macrophages are

involved in angiogenesis, tissue repair, and tumor progression

(182).

TAMs are the most common immune cells that

infiltrate the TME. Their role in promoting tumor growth has been

extensively studied (183).

Recent studies have shown that macrophages in the TME are

continuously transitioning between two states: M1 and M2 (184,185). During the early stages of tumor

growth, macrophages primarily differentiate into tumor infiltrating

M1 macrophages to promote the antitumor immune response. However,

in the latter stages, they primarily differentiate into the M2

subtype to counteract the antitumor effect. In the TME, TAMs are

predominantly of the M2 variety (178). They primarily promote

angiogenesis, invasion, metastasis and tumor cell proliferation

(180). TAMs exert their

antitumor effects through three main mechanisms: i) Secretion of

inhibitory cytokines, which inhibit CD8+ T lymphocytes

from destroying tumor cells, such as TGF-β and IL-10 (181); ii) regulation of the

epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and extracellular matrix

remodeling, which contributes to the malignant biological

characteristics and migration of tumor cells (182,183); and iii) tumor angiogenesis, in

which growth factors (such as platelet-derived growth factor and

VEGF) released by TAMs aid in tumor angiogenesis, creating blood

vessels that promote tumor cell spread. These effects were

indicated in several malignant types of tumor, including prostate,

bladder and breast cancer (186). Therefore, TAMs serve a critical

role in tumor development.

In DLBCL, TAMs are associated with disease

progression. Their expression is inversely associated with DLBCL

prognosis (187). A number of

experimental studies reveal that vitamin C can induce the

transformation of M2 macrophages into M1 macrophages to markedly

enhance the oxidative toxicity of M1 macrophages, promoting the

infiltration of tumor-killing T cells and enhancing antitumor

effects (188-190). In summary, pharmacological doses

of vitamin C, acting as a pro-oxidant, can promote the polarization

of TAMs towards the M1 subtype in the TME. This promotes antitumor

effects and facilitates TME remodeling.

MDSCs form a heterogeneous population of cells that

suppress the immune system within the TME. They primarily inhibit

the cytotoxic activity of T cells and natural killer cells, serving

a role in tumor-mediated immune escape (127,191). MDSCs are primarily immature

myeloid cells, consisting mainly of monocytes (M-MDSC) and

polymorphonuclear cells (PMN-MDSC). Studies demonstrate that M-MDSC

and PMN-MDSC are expanded in the majority of solid tumors, such as

hepatocellular carcinoma (192)

and melanoma (193). Although

PMN-MDSC forms the predominant subgroup, a study by Azzaoui et

al (194) demonstrates that

M-MDSC is the most inhibitory subgroup, with the absence of

PMN-MDSC not altering the tumor incidence. In colorectal and breast

cancer, monocytes/M-MDSC can differentiate into TAMs within the TME

and interact with TAMs to inhibit antitumor effects (195-197). This suggests that targeting

MDSCs may enhance antitumor effects. It has been observed that a

notable number of MDSCs can effectively impair T cell responses in

DLBCL (194). Previous studies

suggest that MDSCs serve a key role in early drug resistance

following R-CHOP treatment for DLBCL (198,199). At present, to the best of our

knowledge, the direct impact of vitamin C on MDSCs has not been

studied. However, it is likely that vitamin C can mediate

regulatory effects on DCs, TILs and TAMs within the TME to

influence MDSCs by modulating the TME (200).

AA is a water-soluble vitamin with various chemical

and physical properties. It should be stored in a shaded

environment. When administered at high doses (1-1.5 g/kg), vitamin

C exhibits pro-oxidant properties and may be beneficial in

antitumor therapy (201,202). Previous studies indicate that

when taken orally, vitamin C reaches lower plasma concentrations

compared with intravenous (IV) administration (33,74). The majority of existing in

vivo studies indicate that high doses of AA (1-4 g/kg)

administered through IV or intraperitoneal injection can inhibit

tumor growth by 40-60%.

The present review investigated the role of vitamin

C in treating DLBCL, but several challenges remain that limit its

clinical application. These challenges include determining the

optimal dose and blood concentration of vitamin C, in addition to

its concentration at the tumor site. High-dose vitamin C has

demonstrated antitumor effects in various studies, with doses

ranging from 1.5 g/kg (32,202), 10 g/day (203) and 50-100 g per dose (2-3 times a

week) (204). However, no

conclusive data support an ideal dose and/or frequency of

administration that would maximize its antitumor benefits. It is

also unclear whether the antitumor effect is dose-independent or

associated with the appropriate blood concentration (205,206). Therefore, further research is

needed to determine the optimal vitamin C treatment strategy to

maximize cellular uptake whilst preventing cytotoxicity.

Another challenge is understanding the role of

SVCT2 in the transport of vitamin C. SVCT2 has low saturation and

high affinity (207), but its

involvement is crucial for effective drug distribution. In

addition, the growth and hypoxic environment of tumor blood vessels

in DLBCL can reduce the permeability and concentration of antitumor

drugs in the TME (208),

blocking the access of vitamin C to the tumor site. SVCT2 protein

cannot be detected in the cell membranes of renal cell carcinoma

and breast cancer cells, but it is unclear whether this affects the

transport of vitamin C (209).

There is insufficient information on how SVCT2 is distributed and

expressed in tumor cells. Therefore, further research is needed to

elucidate how SVCT2 is expressed and distributed in tumor cells to

enhance the concentration of vitamin C in the TME. Numerous studies

have reported that vitamin C has anticancer properties and can

enhance the efficacy of antitumor treatments (33,153). However, relevant in vitro

and in vivo experiments involving DLBCL are currently

lacking. Therefore, further research is needed to clarify the

anticancer efficacy of vitamin C in DLBCL, its associated signaling

pathways and its impact on the TME. The present paper aimed to

establish a theoretical and empirical foundation for the clinical

application of vitamin C as a supplementary agent in cancer

therapy.

DLBCL is the most common subtype of non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma and is distinguished by its aggressive nature and

unfavorable prognosis. The present review investigated the

mechanisms through which vitamin C may influence the efficacy of

DLBCL treatment, proposing a potential association between vitamin

C and DLBCL, which may enhance the antitumor effectiveness of

pharmacological therapies through various mechanisms or pathways.

However, further research is required to clarify the specific

mechanisms involved and to investigate the potential therapeutic

implications within the framework of DLBCL management.

Not applicable.

CR took part in the conceptualization, figure

curation and writing of the original draft. YW and ML took part in

the conceptualization, supervision and editing and reviewing the

manuscript. YL took part in the conceptualization and figure

curation. All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Not applicable.

Supported by the Graduate Student Research Grant from Weifang

Medical University (Weifang Science and Technology Development

Program; grant no. 2024YX045).

|

1

|

Zhao P, Zhao S, Huang C, Li Y, Wang J, Xu

J, Li L, Qian Z, Li W, Zhou S, et al: Efficacy and safety of

polatuzumab vedotin plus rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin

and prednisone for previously untreated diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: A real-world, multi-center, retrospective cohort study.

Hematol Oncol. 43:e700172025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Vaughn JL, Ramdhanny A, Munir M,

Rimmalapudi S and Epperla N: A comparative analysis of transformed

indolent lymphomas and de novo diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A

population-based cohort study. Blood Cancer J. 14:2122024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Schmitz R, Wright GW, Huang DW, Johnson

CA, Phelan JD, Wang JQ, Roulland S, Kasbekar M, Young RM, Shaffer

AL, et al: Genetics and pathogenesis of diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 378:1396–1407. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bantilan KS, Smith AN, Maurer MJ,

Teruya-Feldstein J, Matasar MJ, Moskowitz AJ, Straus DJ, Noy A,

Palomba ML, Horwitz SM, et al: Matched control analysis suggests

that R-CHOP followed by (R)-ICE may improve outcome in non-GCB

DLBCL compared with R-CHOP. Blood Adv. 8:2172–2181. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

García-Sancho AM, Cabero A and Gutiérrez

NC: Treatment of relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma: New approved options. J Clin Med. 13:702023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Coiffier B, Thieblemont C, Van Den Neste

E, Lepeu G, Plantier I, Castaigne S, Lefort S, Marit G, Macro M,

Sebban C, et al: Long-term outcome of patients in the LNH-98.5

trial, the first randomized study comparing rituximab-CHOP to

standard CHOP chemotherapy in DLBCL patients: a study by the Groupe

d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte. Blood. 116:2040–2045. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pfreundschuh M, Trümper L, Osterborg A,

Pettengell R, Trneny M, Imrie K, Ma D, Gill D, Walewski J, Zinzani

PL, et al: CHOP-like chemotherapy plus rituximab versus CHOP-like

chemotherapy alone in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse

large-B-cell lymphoma: A randomised controlled trial by the

MabThera international trial (MInT) group. Lancet Oncol. 7:379–391.

2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Pinzone MR, Berretta M, Cacopardo B and

Nunnari G: Epstein-barr virus- and Kaposi sarcoma-associated

herpesvirus-related malignancies in the setting of human

immunodeficiency virus infection. Semin Oncol. 42:258–271. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chapman JR, Bouska AC, Zhang W, Alderuccio

JP, Lossos IS, Rimsza LM, Maguire A, Yi S, Chan WC, Vega F and Song

JY: EBV-positive HIV-associated diffuse large B cell lymphomas are

characterized by JAK/STAT (STAT3) pathway mutations and unique

clinicopathologic features. Br J Haematol. 194:870–878. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Gianella S, Anderson CM, Var SR, Oliveira

MF, Lada SM, Vargas MV, Massanella M, Little SJ, Richman DD, Strain

MC, et al: Replication of human herpesviruses is associated with

higher HIV DNA levels during antiretroviral therapy started at

early phases of HIV infection. J Virol. 90:3944–3952. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang SS: Epidemiology and etiology of

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol. 60:255–266. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ekström Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M,

Engels EA, Martínez-Maza O, Turner J, Hjalgrim H, Vineis P, Seniori

Costantini A, Bracci PM, et al: Autoimmune disorders and risk of

non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: A pooled analysis within the

InterLymph consortium. Blood. 111:4029–4038. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yang L, Liang Y, Pu J, Cai L, Gao R, Han

F, Chang K, Pan S, Wu Z, Zhang Y, et al: Dysregulated serum lipid

profile is associated with inflammation and disease activity in

primary Sjögren's syndrome: A retrospective study in China. Immunol

Lett. 267:1068652024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Almasmoum HA: Molecular complexity of

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A molecular perspective and

therapeutic implications. J Appl Genet. 65:57–72. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Serganova I, Chakraborty S, Yamshon S,

Isshiki Y, Bucktrout R, Melnick A, Béguelin W and Zappasodi R:

Epigenetic, metabolic, and immune crosstalk in

germinal-center-derived B-cell lymphomas: Unveiling new

vulnerabilities for rational combination therapies. Front Cell Dev

Biol. 9:8051952022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Horn H, Ziepert M, Becher C, Barth TF,

Bernd HW, Feller AC, Klapper W, Hummel M, Stein H, Hansmann ML, et

al: MYC status in concert with BCL2 and BCL6 expression predicts

outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood. 121:2253–2263.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Riedell PA and Smith SM: Double hit and

double expressors in lymphoma: Definition and treatment. Cancer.

124:4622–4632. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Cioroianu AI, Stinga PI, Sticlaru L,

Cioplea MD, Nichita L, Popp C and Staniceanu F: Tumor

microenvironment in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: role and

prognosis. Anal Cell Pathol (Amst). 2019:85863542019.

|

|

19

|

Momivand M, Razaghi M, Mohammadi F,

Hoseinzadeh E and Najafi-Vosough R: The status of serum 25(OH)D

levels is related to breast cancer. Cancer Treat Res Commun.

42:1008702024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Jang Y and Kim CY: The role of vitamin e

isoforms and metabolites in cancer prevention: Mechanistic insights

into sphingolipid metabolism modulation. Nutrients. 16:41152024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Paller CJ, Zahurak ML, Mandl A, Metri NA,

Lalji A, Heath E, Kelly WK, Hoimes C, Barata P, Taksey J, et al:

High-dose intravenous vitamin C combined with docetaxel in men with

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: A randomized

placebo-controlled phase II trial. Cancer Res Commun. 4:2174–2182.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Gillberg L, Ørskov AD, Nasif A, Ohtani H,

Madaj Z, Hansen JW, Rapin N, Mogensen JB, Liu M, Dufva IH, et al:

Oral vitamin C supplementation to patients with myeloid cancer on

azacitidine treatment: Normalization of plasma vitamin C induces

epigenetic changes. Clin Epigenetics. 11:1432019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

O'Leary BR, Alexander MS, Du J, Moose DL,

Henry MD and Cullen JJ: Pharmacological ascorbate inhibits

pancreatic cancer metastases via a peroxide-mediated mechanism. Sci

Rep. 10:176492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Furqan M, Abu-Hejleh T, Stephens LM,

Hartwig SM, Mott SL, Pulliam CF, Petronek M, Henrich JB, Fath MA,

Houtman JC, et al: Pharmacological ascorbate improves the response

to platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced stage non-small cell

lung cancer. Redox Biol. 53:1023182022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Bodeker KL, Smith BJ, Berg DJ,

Chandrasekharan C, Sharif S, Fei N, Vollstedt S, Brown H, Chandler

M, Lorack A, et al: A randomized trial of pharmacological

ascorbate, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel for metastatic

pancreatic cancer. Redox Biol. 77:1033752024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Su X, Shen Z, Yang Q, Sui F, Pu J, Ma J,

Ma S, Yao D, Ji M and Hou P: Vitamin C kills thyroid cancer cells

through ROS-dependent inhibition of MAPK/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways

via distinct mechanisms. Theranostics. 9:4461–4473. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Zhou J, Chen C, Chen X, Fei Y, Jiang L and

Wang G: Vitamin C promotes apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in oral

squamous cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 10:9762020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Su X, Li P, Han B, Jia H, Liang Q, Wang H,

Gu M, Cai J, Li S, Zhou Y, et al: Vitamin C sensitizes

BRAFV600E thyroid cancer to PLX4032 via inhibiting the

feedback activation of MAPK/ERK signal by PLX4032. J Exp Clin

Cancer Res. 40:342021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhao X, Liu M, Li C, Liu X, Zhao J, Ma H,

Zhang S and Qu J: High dose vitamin C inhibits PD-L1 by ROS-pSTAT3

signal pathway and enhances T cell function in TNBC. Int

Immunopharmacol. 126:1113212024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lv H, Zong Q, Chen C, Lv G, Xiang W, Xing

F, Jiang G, Yan B, Sun X, Ma Y, et al: TET2-mediated tumor cGAS

triggers endothelial STING activation to regulate vasculature

remodeling and anti-tumor immunity in liver cancer. Nat Commun.

15:62024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Williams DJ, Edwards D, Pun S, Chaliha M,

Burren B, Tinggi U and Sultanbawa Y: Organic acids in Kakadu plum

(Terminalia ferdinandiana): The good (ellagic), the bad (oxalic)

and the uncertain (ascorbic). Food Res Int. 89:237–244. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Böttger F, Vallés-Martí A, Cahn L and

Jimenez CR: High-dose intravenous vitamin C, a promising

multi-targeting agent in the treatment of cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer

Res. 40:3432021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ngo B, Van Riper JM, Cantley LC and Yun J:

Targeting cancer vulnerabilities with high-dose vitamin C. Nat Rev

Cancer. 19:271–282. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chang JE, Voorhees PM, Kolesar JM, Ahuja

HG, Sanchez FA, Rodriguez GA, Kim K, Werndli J, Bailey HH and Kahl

BS: Phase II study of arsenic trioxide and ascorbic acid for

relapsed or refractory lymphoid malignancies: A wisconsin oncology

network study. Hematol Oncol. 27:11–16. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kawada H, Sawanobori M, Tsuma-Kaneko M,

Wasada I, Miyamoto M, Murayama H, Toyosaki M, Onizuka M, Tsuboi K,

Tazume K, et al: Phase I clinical trial of intravenous l-ascorbic

acid following salvage chemotherapy for relapsed B-cell

non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 39:111–115.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Carr AC and Maggini S: Vitamin C and

immune function. Nutrients. 9:12112017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Padayatty SJ and Levine M: Vitamin C: The

known and the unknown and goldilocks. Oral Dis. 22:463–493. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Bhoot HR, Zamwar UM, Chakole S and

Anjankar A: Dietary sources, bioavailability, and functions of

ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and its role in the common cold, tissue

healing, and iron metabolism. Cureus. 15:e493082023.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bowry SK: Dialysis membranes today. Int J

Artif Organs. 25:447–460. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Bürzle M, Suzuki Y, Ackermann D, Miyazaki

H, Maeda N, Clémençon B, Burrier R and Hediger MA: The

sodium-dependent ascorbic acid transporter family SLC23. Mol

Aspects Med. 34:436–454. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Lykkesfeldt J and Tveden-Nyborg P: The

pharmacokinetics of vitamin C. Nutrients. 11:24122019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Doseděl M, Jirkovský E, Macáková K,

Krčmová LK, Javorská L, Pourová J, Mercolini L, Remião F, Nováková

L, Mladěnka P, et al: Vitamin C-sources, physiological role,

kinetics, deficiency, use, toxicity, and determination. Nutrients.

13:6152021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Hasselholt S, Tveden-Nyborg P and

Lykkesfeldt J: Distribution of vitamin C is tissue specific with

early saturation of the brain and adrenal glands following

differential oral dose regimens in guinea pigs. Br J Nutr.

113:1539–1549. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Mohammed BM, Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D,

Ward S, Wayne JS, Brophy DF, Fowler AA III, Yager DR and Natarajan

R: Vitamin C promotes wound healing through novel pleiotropic

mechanisms. Int Wound J. 13:572–584. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Moores J: Vitamin C: A wound healing

perspective. Br J Community Nurs. Suppl:S6S8–S11. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Fisher BJ, Kraskauskas D, Martin EJ,

Farkas D, Puri P, Massey HD, Idowu MO, Brophy DF, Voelkel NF,

Fowler AA III and Natarajan R: Attenuation of sepsis-induced organ

injury in mice by vitamin C. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr.

38:825–839. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Carr AC, Shaw GM, Fowler AA and Natarajan

R: Ascorbate-dependent vasopressor synthesis: A rationale for

vitamin C administration in severe sepsis and septic shock? Crit

Care. 19:4182015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Bozonet SM, Carr AC, Pullar JM and Vissers

MC: Enhanced human neutrophil vitamin C status, chemotaxis and

oxidant generation following dietary supplementation with vitamin

C-rich SunGold kiwifruit. Nutrients. 7:2574–2588. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Hong JM, Kim JH, Kang JS, Lee WJ and Hwang

YI: Vitamin C is taken up by human T cells via sodium-dependent

vitamin C transporter 2 (SVCT2) and exerts inhibitory effects on

the activation of these cells in vitro. Anat Cell Biol. 49:88–98.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Molina N, Morandi AC, Bolin AP and Otton

R: Comparative effect of fucoxanthin and vitamin C on oxidative and

functional parameters of human lymphocytes. Int Immunopharmacol.

22:41–50. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

van Gorkom GNY, Klein Wolterink RGJ, Van

Elssen CHMJ, Wieten L, Germeraad WTV and Bos GMJ: Influence of

vitamin C on lymphocytes: An overview. Antioxidants (Basel).

7:412018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Zhang X, Zhang Y, Wang C and Wang X: TET

(Ten-eleven translocation) family proteins: Structure, biological

functions and applications. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

8:2972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Yue X, Trifari S, Äijö T, Tsagaratou A,

Pastor WA, Zepeda-Martínez JA, Lio CW, Li X, Huang Y, Vijayanand P,

et al: Control of Foxp3 stability through modulation of TET

activity. J Exp Med. 213:377–397. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Warren CFA, Wong-Brown MW and Bowden NA:

BCL-2 family isoforms in apoptosis and cancer. Cell Death Dis.

10:1772019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Singh R, Letai A and Sarosiek K:

Regulation of apoptosis in health and disease: The balancing act of

BCL-2 family proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 20:175–193. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Deng X, Gao F and May WS Jr: Bcl2 retards

G1/S cell cycle transition by regulating intracellular ROS. Blood.

102:3179–3185. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Güler A, Yardımcı BK and Özek NŞ: Human

anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL proteins protect yeast cells from

aging induced oxidative stress. Biochimie. 229:69–83. 2025.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Yu X, Wang Y, Tan J, Li Y, Yang P, Liu X,

Lai J, Zhang Y, Cai L, Gu Y, et al: Inhibition of NRF2 enhances the

acute myeloid leukemia cell death induced by venetoclax via the

ferroptosis pathway. Cell Death Discov. 10:352024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sies H: Oxidative stress: A concept in

redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 4:180–183. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Assi M: The differential role of reactive

oxygen species in early and late stages of cancer. Am J Physiol

Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 313:R646–R653. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Hayes JD, Dinkova-Kostova AT and Tew KD:

Oxidative stress in cancer. Cancer Cell. 38:167–197. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Sahoo BM, Banik BK, Borah P and Jain A:

Reactive oxygen species (ROS): Key components in cancer therapies.

Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 22:215–222. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Ebrahim AS, Sabbagh H, Liddane A, Raufi A,

Kandouz M and Al-Katib A: Hematologic malignancies: Newer

strategies to counter the BCL-2 protein. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol.

142:2013–2022. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Ashkenazi A, Fairbrother WJ, Leverson JD

and Souers AJ: From basic apoptosis discoveries to advanced

selective BCL-2 family inhibitors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 16:273–284.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Sermer D, Bobillo S, Dogan A, Zhang Y,

Seshan V, Lavery JA, Batlevi C, Caron P, Hamilton A, Hamlin P, et

al: Extra copies of MYC, BCL2, and BCL6 and outcome in patients

with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Adv. 4:3382–3390. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Cerón R, Martínez A, Ramos C, De la Cruz

A, García A, Mendoza I, Palmeros G, Montaño Figueroa EH, Navarrete

J, Jiménez-Morales S, et al: Overexpression of BCL2, BCL6, VEGFR1

and TWIST1 in circulating tumor cells derived from patients with

DLBCL decreases event-free survival. Onco Targets Ther.

15:1583–1595. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Low IC, Kang J and Pervaiz S: Bcl-2: A

prime regulator of mitochondrial redox metabolism in cancer cells.

Antioxid Redox Signal. 15:2975–2987. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Krishna S, Low ICC and Pervaiz S:

Regulation of mitochondrial metabolism: Yet another facet in the

biology of the oncoprotein Bcl-2. Biochem J. 435:545–551. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Eno CO, Zhao G, Olberding KE and Li C: The

Bcl-2 proteins Noxa and Bcl-xL co-ordinately regulate oxidative

stress-induced apoptosis. Biochem J. 444:69–78. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Lagadinou ED, Sach A, Callahan K, Rossi

RM, Neering SJ, Minhajuddin M, Ashton JM, Pei S, Grose V, O'Dwyer

KM, et al: BCL-2 inhibition targets oxidative phosphorylation and

selectively eradicates quiescent human leukemia stem cells. Cell

Stem Cell. 12:329–341. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Lv H, Wang C, Fang T, Li T, Lv G, Han Q,

Yang W and Wang H: Vitamin C preferentially kills cancer stem cells

in hepatocellular carcinoma via SVCT-2. NPJ Precis Oncol. 2:12018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ghanem A, Melzer AM, Zaal E, Neises L,

Baltissen D, Matar O, Glennemeier-Marke H, Almouhanna F, Theobald

J, Abu El Maaty MA, et al: Ascorbate kills breast cancer cells by

rewiring metabolism via redox imbalance and energy crisis. Free

Radic Biol Med. 163:196–209. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Chen Q, Espey MG, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB,

Corpe CP, Buettner GR, Shacter E and Levine M: Pharmacologic

ascorbic acid concentrations selectively kill cancer cells: Action

as a pro-drug to deliver hydrogen peroxide to tissues. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 102:13604–13609. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Fan D, Liu X, Shen Z, Wu P, Zhong L and

Lin F: Cell signaling pathways based on vitamin C and their

application in cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother. 162:1146952023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

El-Garawani IM, El-Nabi SH, El-Shafey S,

Elfiky M and Nafie E: Coffea arabica bean extracts and vitamin C: A

novel combination unleashes MCF-7 cell death. Curr Pharm

Biotechnol. 21:23–36. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Chen MS, Zhao HK, Cheng YY, Yuan ZH and

Zhang YL: Toxic effects of vitamin C combined with temozolomide on

glioma cells and its mechanism. Zhongguo Ying Yong Sheng Li Xue Za

Zhi. 36:616–621. 2020.In Chinese.

|

|

77

|

Liongue C, Almohaisen F and Ward AC: B

cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6): A conserved regulator of immunity and

beyond. Int J Mol Sci. 25:109682024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Basso K and Dalla-Favera R: Roles of BCL6

in normal and transformed germinal center B cells. Immunol Rev.

247:172–183. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Phan RT and Dalla-Favera R: The BCL6

proto-oncogene suppresses p53 expression in germinal-centre B

cells. Nature. 432:635–639. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kerckaert JP, Deweindt C, Tilly H, Quief

S, Lecocq G and Bastard C: LAZ3, a novel zinc-finger encoding gene,

is disrupted by recurring chromosome 3q27 translocations in human

lymphomas. Nat Genet. 5:66–70. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Johnston RJ, Poholek AC, DiToro D, Yusuf

I, Eto D, Barnett B, Dent AL, Craft J and Crotty S: Bcl6 and

Blimp-1 are reciprocal and antagonistic regulators of T follicular

helper cell differentiation. Science. 325:1006–1010. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Zan H, Wu X, Komori A, Holloman WK and

Casali P: AID-dependent generation of resected double-strand DNA

breaks and recruitment of Rad52/Rad51 in somatic hypermutation.

Immunity. 18:727–738. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Liu Y, Feng J, Yuan K, Wu Z, Hu L, Lu Y,

Li K, Guo J, Chen J, Ma C and Pang X: The oncoprotein BCL6 enables

solid tumor cells to evade genotoxic stress. Elife. 11:e692552022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

McLachlan T, Matthews WC, Jackson ER,

Staudt DE, Douglas AM, Findlay IJ, Persson ML, Duchatel RJ, Mannan

A, Germon ZP and Dun MD: B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6): From master

regulator of humoral immunity to oncogenic driver in pediatric

cancers. Mol Cancer Res. 20:1711–1723. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Louwen F, Kreis NN, Ritter A, Friemel A,

Solbach C and Yuan J: BCL6, a key oncogene, in the placenta,

pre-eclampsia and endometriosis. Hum Reprod Update. 28:890–909.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Leeman-Neill RJ and Bhagat G: BCL6 as a

therapeutic target for lymphoma. Expert Opin Ther Targets.

22:143–152. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Huang C and Melnick A: Mechanisms of

action of BCL6 during germinal center B cell development. Sci China

Life Sci. 58:1226–1232. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Krull JE, Wenzl K, Hartert KT, Manske MK,

Sarangi V, Maurer MJ, Larson MC, Nowakowski GS, Ansell SM, McPhail

E, et al: Somatic copy number gains in MYC, BCL2, and BCL6

identifies a subset of aggressive alternative-DH/TH DLBCL patients.

Blood Cancer J. 10:1172020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Ting CY, Chang KM, Kuan JW, Sathar J, Chew

LP, Wong OJ, Yusuf Y, Wong L, Samsudin AT, Pana MNBM, et al:

Clinical significance of BCL2, C-MYC, and BCL6 genetic

abnormalities, epstein-barr virus infection, CD5 protein

expression, germinal center B Cell/non-germinal center B-cell

subtypes, co-expression of MYC/BCL2 proteins and co-expression of

MYC/BCL2/BCL6 proteins in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a clinical

and pathological correlation study of 120 patients. Int J Med Sci.

16:556–566. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

90

|

Ferretti GDS, Quarti J, Dos Santos G,

Rangel LP and Silva JL: Anticancer therapeutic strategies targeting

p53 aggregation. Int J Mol Sci. 23:110232022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Bieging KT, Mello SS and Attardi LD:

Unravelling mechanisms of p53-mediated tumour suppression. Nat Rev

Cancer. 14:359–370. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Williams AB and Schumacher B: p53 in the

DNA-damage-repair process. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med.

6:a0260702016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Sermeus A and Michiels C: Reciprocal

influence of the p53 and the hypoxic pathways. Cell Death Dis.

2:e1642011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Miyata S, Ishii T and Kitanaka S:

Reduction of HIF-1α/PD-L1 by catalytic topoisomerase inhibitor

induces cell death through caspase activation in cancer cells under

hypoxia. Anticancer Res. 44:49–59. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Madan E, Parker TM, Pelham CJ, Palma AM,

Peixoto ML, Nagane M, Chandaria A, Tomás AR, Canas-Marques R,

Henriques V, et al: HIF-transcribed p53 chaperones HIF-1α. Nucleic

Acids Res. 47:10212–10234. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Ismail S, Elshimali Y, Daoud A and

Alshehabi Z: Immunohistochemical expression of transcription

factors PAX5, OCT2, BCL6 and transcription regulator P53 in

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas: A diagnostic cross-sectional study. Ann Med

Surg (Lond). 78:1037862022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Choi SH, Koh DI, Cho SY, Kim MK, Kim KS

and Hur MW: Temporal and differential regulation of

KAISO-controlled transcription by phosphorylated and acetylated p53

highlights a crucial regulatory role of apoptosis. J Biol Chem.

294:12957–12974. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Margalit O, Amram H, Amariglio N, Simon

AJ, Shaklai S, Granot G, Minsky N, Shimoni A, Harmelin A, Givol D,

et al: BCL6 is regulated by p53 through a response element

frequently disrupted in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood.

107:1599–1607. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Kaźmierczak-Barańska J, Boguszewska K,

Adamus-Grabicka A and Karwowski BT: Two faces of vitamin

C-antioxidative and pro-oxidative agent. Nutrients. 12:15012020.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Xiong Y, Xu S, Fu B, Tang W, Zaky MY, Tian

R, Yao R, Zhang S, Zhao Q, Nian W, et al: Vitamin C-induced

competitive binding of HIF-1α and p53 to ubiquitin E3 ligase CBL

contributes to anti-breast cancer progression through p53

deacetylation. Food Chem Toxicol. 168:1133212022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Kim J, Lee SD, Chang B, Jin DH, Jung SI,

Park MY, Han Y, Yang Y, Il Kim K, Lim JS, et al: Enhanced antitumor

activity of vitamin C via p53 in cancer cells. Free Radic Biol Med.

53:1607–1615. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Huang K: Chemical inducers of proximity:

Precision tools for apoptosis in transcriptional regulation. Signal

Transduct Target Ther. 9:3642024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Duffy MJ, O'Grady S, Tang M and Crown J:

MYC as a target for cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev.

94:1021542021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Das SK, Lewis BA and Levens D: MYC: A

complex problem. Trends Cell Biol. 33:235–246. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

105

|

Ellenbroek BD, Kahler JP, Arella D, Lin C,

Jespers W, Züger EA, Drukker M and Pomplun SJ: Development of

DuoMYC: A synthetic cell penetrant miniprotein that efficiently

inhibits the oncogenic transcription factor MYC. Angew Chem Int Ed

Engl. 64:e2024160822025. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

106

|

Baluapuri A, Wolf E and Eilers M: Target

gene-independent functions of MYC oncoproteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell

Biol. 21:255–267. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Liu Z, Chen SS, Clarke S, Veschi V and

Thiele CJ: Targeting MYCN in pediatric and adult cancers. Front

Oncol. 10:6236792021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Massó-Vallés D, Beaulieu ME and Soucek L:

MYC, MYCL, and MYCN as therapeutic targets in lung cancer. Expert

Opin Ther Targets. 24:101–114. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

109

|

Stoelzle T, Schwarb P, Trumpp A and Hynes

NE: c-Myc affects mRNA translation, cell proliferation and

progenitor cell function in the mammary gland. BMC Biol. 7:632009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

110

|

Felipe I, Martínez-de-Villarreal J, Patel

K, Martínez-Torrecuadrada J, Grossmann LD, Roncador G, Cubells M,

Farrell A, Kendsersky N, Sabroso-Lasa S, et al: BPTF cooperates

with MYCN and MYC to link neuroblastoma cell cycle control to

epigenetic cellular states. bioRxiv [Preprint]: 2024.02.11.579816.

2024.

|

|

111

|

Mahdavi P, Panahipoor Javaherdehi A,

Khanjanpoor P, Aminian H, Zakeri M, Zafarani A and Razizadeh MH:

The role of c-Myc in Epstein-Barr virus-associated cancers:

Mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. Microb Pathog.

197:1070252024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

112

|

Yoon J, Jeon T, Kwon JA and Yoon SY:

Characterization of MYC rearrangements in multiple myeloma: An

optical genome mapping approach. Blood Cancer J. 14:1652024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

113

|

Jakobsen ST and Siersbæk R:

Transcriptional regulation by MYC: An emerging new model. Oncogene.

44:1–7. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Bisso A, Filipuzzi M, Gamarra Figueroa GP,

Brumana G, Biagioni F, Doni M, Ceccotti G, Tanaskovic N, Morelli

MJ, Pendino V, et al: Cooperation between MYC and β-catenin in

liver tumorigenesis requires Yap/Taz. Hepatology. 72:1430–1443.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

115

|

Dhanasekaran R, Deutzmann A,

Mahauad-Fernandez WD, Hansen AS, Gouw AM and Felsher DW: The MYC

oncogene-the grand orchestrator of cancer growth and immune

evasion. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 19:23–36. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Baena E, Ortiz M, Martínez-A C and de

Alborán IM: c-Myc is essential for hematopoietic stem cell

differentiation and regulates Lin(-)Sca-1(+)c-Kit(-) cell

generation through p21. Exp Hematol. 35:1333–1343. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

117

|

Sewastianik T, Prochorec-Sobieszek M,

Chapuy B and Juszczyński P: MYC deregulation in lymphoid tumors:

Molecular mechanisms, clinical consequences and therapeutic

implications. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1846:457–467. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

118

|

Susanibar-Adaniya S and Barta SK: 2021

Update on diffuse large B cell lymphoma: A review of current data

and potential applications on risk stratification and management.

Am J Hematol. 96:617–629. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

119

|

Candelaria M, Cerrato-Izaguirre D,

Gutierrez O, Diaz-Chavez J, Aviles A, Dueñas-Gonzalez A and Malpica

L: Characterizing the mutational landscape of diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma in a prospective cohort of mexican patients. Int J Mol

Sci. 25:93282024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

120

|

Hashmi AA, Iftikhar SN, Nargus G, Ahmed O,

Asghar IA, Shirazi UA, Afzal A, Irfan M and Ali J: Double-expressor

phenotype (BCL-2/c-MYC co-expression) of diffuse large B-cell

lymphoma and its clinicopathological correlation. Cureus.

13:e131552021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

121

|

Wu G, Liu T, Li H, Li Y, Li D and Li W:

c-MYC and reactive oxygen species play roles in tetrandrine-induced

leukemia differentiation. Cell Death Dis. 9:4732018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

122

|

Koo JI, Sim DY, Lee HJ, Ahn CH, Park J,

Park SY, Lee D, Shim BS, Kim B and Kim SH: Apoptotic and

anti-Warburg effect of Morusin via ROS mediated inhibition of

FOXM1/c-Myc signaling in prostate cancer cells. Phytother Res.

37:4473–4487. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

123

|

Meng L, Gao J, Mo W, Wang B, Shen H, Cao

W, Ding M, Diao W, Chen W, Zhang Q, et al: MIOX inhibits autophagy

to regulate the ROS-driven inhibition of STAT3/c-Myc-mediated

epithelial-mesenchymal transition in clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Redox Biol. 68:1029562023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Yao L, Wu P, Yao F, Huang B, Zhong F and

Wang X: ZCCHC4 regulates esophageal cancer progression and

cisplatin resistance through ROS/c-myc axis. Sci Rep. 15:51492025.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

125

|

Donati G, Nicoli P, Verrecchia A,

Vallelonga V, Croci O, Rodighiero S, Audano M, Cassina L, Ghsein A,

Binelli G, et al: Oxidative stress enhances the therapeutic action

of a respiratory inhibitor in MYC-driven lymphoma. EMBO Mol Med.

15:e169102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

126

|

Firouzjaei AA and Mohammadi-Yeganeh S: The

intricate interplay between ferroptosis and efferocytosis in

cancer: Unraveling novel insights and therapeutic opportunities.

Front Oncol. 14:14242182024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

127

|

Ahn M, Ali A and Seo JH: Mitochondrial

regulation in the tumor microenvironment: Targeting mitochondria

for immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 15:14538862024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

128

|

Shen M and Kang Y: Complex interplay

between tumor microenvironment and cancer therapy. Front Med.

12:426–439. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

129

|

Manea AJ and Ray SK: Advanced

bioinformatics analysis and genetic technologies for targeting

autophagy in glioblastoma multiforme. Cells. 12:8972023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

130

|

Pitt JM, Marabelle A, Eggermont A, Soria

JC, Kroemer G and Zitvogel L: Targeting the tumor microenvironment:

Removing obstruction to anticancer immune responses and

immunotherapy. Ann Oncol. 27:1482–1492. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

131

|

Tong X, Tang R, Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W,

Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X and Shi S: Targeting cell death pathways for

cancer therapy: Recent developments in necroptosis, pyroptosis,

ferroptosis, and cuproptosis research. J Hematol Oncol. 15:1742022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

132

|

Babar Q, Saeed A, Tabish TA, Sarwar M and

Thorat ND: Targeting the tumor microenvironment: Potential strategy

for cancer therapeutics. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis.

1869:1667462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

133

|

Worbs T, Hammerschmidt SI and Förster R:

Dendritic cell migration in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol.

17:30–48. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

134

|

Wculek SK, Cueto FJ, Mujal AM, Melero I,

Krummel MF and Sancho D: Dendritic cells in cancer immunology and

immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 20:7–24. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

135

|

Gardner A and Ruffell B: Dendritic cells

and cancer immunity. Trends Immunol. 37:855–865. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

136

|

Noubade R, Majri-Morrison S and Tarbell

KV: Beyond cDC1: Emerging roles of DC crosstalk in cancer immunity.

Front Immunol. 10:10142019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

137

|

Böttcher JP and Reis e Sousa C: The role

of type 1 conventional dendritic cells in cancer immunity. Trends

Cancer. 4:784–792. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

138

|

Wculek SK, Amores-Iniesta J, Conde-Garrosa

R, Khouili SC, Melero I and Sancho D: Effective cancer

immunotherapy by natural mouse conventional type-1 dendritic cells

bearing dead tumor antigen. J Immunother Cancer. 7:1002019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

139

|

Binnewies M, Mujal AM, Pollack JL, Combes

AJ, Hardison EA, Barry KC, Tsui J, Ruhland MK, Kersten K,

Abushawish MA, et al: Unleashing type-2 dendritic cells to drive

protective antitumor CD4+ T cell immunity. Cell.

177:556–571.e16. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

140

|

Ruhland MK, Roberts EW, Cai E, Mujal AM,

Marchuk K, Beppler C, Nam D, Serwas NK, Binnewies M and Krummel MF:

Visualizing synaptic transfer of tumor antigens among dendritic

cells. Cancer Cell. 37:786–799.e5. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

141

|

Holicek P, Guilbaud E, Klapp V, Truxova I,

Spisek R, Galluzzi L and Fucikova J: Type I interferon and cancer.

Immunol Rev. 321:115–127. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

142

|

Chrisikos TT, Zhou Y, Slone N, Babcock R,

Watowich SS and Li HS: Molecular regulation of dendritic cell

development and function in homeostasis, inflammation, and cancer.

Mol Immunol. 110:24–39. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

143

|

Veglia F and Gabrilovich DI: Dendritic

cells in cancer: The role revisited. Curr Opin Immunol. 45:43–51.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

144

|

Han SH and Ju MH: Characterizing the tumor

microenvironment and its correlation with cDC1-related gene

expression in gastric cancer. J Immunol Res. 2024:44681452024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

145

|

Kießler M, Plesca I, Sommer U, Wehner R,

Wilczkowski F, Müller L, Tunger A, Lai X, Rentsch A, Peuker K, et

al: Tumor-infiltrating plasmacytoid dendritic cells are associated

with survival in human colon cancer. J Immunother Cancer.

9:e0018132021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

146

|

Aspord C, Leccia MT, Charles J and Plumas

J: Melanoma hijacks plasmacytoid dendritic cells to promote its own

progression. Oncoimmunology. 3:e274022014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

147

|

De Sá Fernandes C, Novoszel P, Gastaldi T,

Krauß D, Lang M, Rica R, Kutschat AP, Holcmann M, Ellmeier W,

Seruggia D, et al: The histone deacetylase HDAC1 controls dendritic

cell development and anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep. 43:1143082024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

148

|

Verneau J, Sautés-Fridman C and Sun CM:

Dendritic cells in the tumor microenvironment: Prognostic and

theranostic impact. Semin Immunol. 48:1014102020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

149

|

Ennishi D: The biology of the tumor

microenvironment in DLBCL: Targeting the 'don't eat me' signal. J

Clin Exp Hematop. 61:210–215. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

150

|

Jeong YJ, Kim JH, Hong JM, Kang JS, Kim

HR, Lee WJ and Hwang YI: Vitamin C treatment of mouse bone

marrow-derived dendritic cells enhanced CD8(+) memory T cell

production capacity of these cells in vivo. Immunobiology.

219:554–564. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

151

|

Kim HW, Cho SI, Bae S, Kim H, Kim Y, Hwang

YI, Kang JS and Lee WJ: Vitamin C up-regulates expression of CD80,

CD86 and MHC class II on dendritic cell line, DC-1 via the

activation of p38 MAPK. Immune Netw. 12:277–283. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

152

|

Morante-Palacios O, Godoy-Tena G,

Calafell-Segura J, Ciudad L, Martínez-Cáceres EM, Sardina JL and

Ballestar E: Vitamin C enhances NF-κB-driven epigenomic

reprogramming and boosts the immunogenic properties of dendritic

cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 50:10981–10994. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

153

|

Magrì A, Germano G, Lorenzato A, Lamba S,

Chilà R, Montone M, Amodio V, Ceruti T, Sassi F, Arena S, et al:

High-dose vitamin C enhances cancer immunotherapy. Sci Transl Med.

12:eaay87072020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

154

|

Chopp L, Redmond C, O'Shea JJ and Schwartz

DM: From thymus to tissues and tumors: A review of T-cell biology.

J Allergy Clin Immunol. 151:81–97. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

155

|

Lawrence T: The nuclear factor NF-kappaB

pathway in inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

1:a0016512009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

156

|

Kina E, Larouche JD, Thibault P and

Perreault C: The cryptic immunopeptidome in health and disease.

Trends Genet. 41:162–169. 2025. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

157

|

Zhao Y, Shao Q and Peng G: Exhaustion and

senescence: Two crucial dysfunctional states of T cells in the

tumor microenvironment. Cell Mol Immunol. 17:27–35. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

158

|

Knez J, Kovačič B and Goropevšek A: The

role of regulatory T-cells in the development of endometriosis. Hum

Reprod. deae1032024.Epub ahead of print. PubMed/NCBI

|

|

159

|

Sawant DV, Yano H, Chikina M, Zhang Q,

Liao M, Liu C, Callahan DJ, Sun Z, Sun T, Tabib T, et al: Adaptive

plasticity of IL-10+ and IL-35+

Treg cells cooperatively promotes tumor T cell

exhaustion. Nat Immunol. 20:724–735. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

160

|

Yi M, Niu M, Wu Y, Ge H, Jiao D, Zhu S,

Zhang J, Yan Y, Zhou P, Chu Q and Wu K: Combination of oral STING

agonist MSA-2 and anti-TGF-β/PD-L1 bispecific antibody YM101: A

novel immune cocktail therapy for non-inflamed tumors. J Hematol

Oncol. 15:1422022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

161

|

Naulaerts S, Datsi A, Borras DM, Antoranz

Martinez A, Messiaen J, Vanmeerbeek I, Sprooten J, Laureano RS,

Govaerts J, Panovska D, et al: Multiomics and spatial mapping