Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection remains a

significant public health concern globally. Approximately 350

million individuals worldwide are chronically infected with HBV,

and such infections may lead to the development of liver cirrhosis

or hepatocellular carcinoma (1,2).

Although various types of antiviral drugs, including

nucleotide/nucleotide analogue and interferon, have been used to

eradicate this virus in recent years, no significant progress has

been achieved (3). Increasing

evidence has demonstrated that patients acutely infected with HBV

usually develop marked, multispecific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL)

responses to the virus, whereas chronically infected individuals

exhibit weak responses (4,5). Therefore, the development of

immunotherapeutic strategies to improve weak virus-specific T cell

responses is critical.

Dendritic cells (DCs) are considered the most potent

antigen-presenting cells (APCs); and as such, are able to initiate

immune responses against invading pathogens (6) and have been observed to be

responsible for the cross-presentation of antigens in vitro

and in vivo as well as the stimulation of naïve cluster of

differentiation (CD)8+ T cell proliferation and

maturation (7). A previous study

revealed that defective CTL responses may be attributed to impaired

DC function (8). Therefore,

promoting and improving the functions of DCs may comprise an

efficient treatment strategy for persistent HBV infections.

Ubiquitin (Ub) is a highly conserved small

regulatory protein (9), and a

centrally significant component of the Ub-proteasome system (UPS),

which attaches covalently to numerous cellular proteins through a

highly regulated process (10,11).

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class-I antigen presentation

is strictly dependent on the supply of appropriate peptides,

mediated by the UPS, with which to efficiently prime

CD8+ T cells and initiate an adaptive immune response

(12,13). The HBV core antigen (HBcAg) is a

highly immunogenic subviral particle that in natural and

recombinant forms may induce marked immune responses characterized

by acute T-cell activity (14).

These hypotheses prompted the present study to investigate whether

a Ub-modified HBcAg fusion protein was able to enter DCs and be

presented by MHC class-I molecules in order to elicit robust CTL

responses.

However, direct intracellular protein delivery is

inhibited by the lipophilic nature of biological membranes

(15). The cytoplasmic

transduction peptide (CTP), which is derived from the protein

transduction domain (PTD) of the human immunodeficiency virus-1

trans-activator of transcription protein, is a novel and

deliberately designed transduction protein used to efficiently

deliver biomolecules into the cytoplasm (16). Therefore, the properties of CTP

provide an opportunity for antigens to enter DCs and thus be

presented by MHC class I molecules.

In the present study, a prokaryotic expression

vector for Ub-HBcAg-CTP (GGRRARRRRRR) was constructed and purified.

Subsequently, the biological activity of the purified fusion

protein was examined to determine whether it was able to be

presented by MHC class-I molecules and consequently efficiently

enhance HBV-specific CTL responses in vitro.

Materials and methods

Animals and cell lines

The present study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of Shanghai JiaoTong University Affiliated Sixth People’s

Hospital (Shanghai, China). Thirty BALB/c mice (H-2d),

aged 6–8 weeks, were purchased from the Shanghai Experimental

Animal Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China)

and maintained in the Experimental Animal Center of the Shanghai

Sixth People’s Hospital under specific pathogen-free conditions

(22–24°C; humidity 50–55%; 12 h light/12 h dark cycle). The mice

were pellet fed standard mouse food and given access to sterilized

water. The mice were cared for and treated in accordance with the

guidelines established by the Shanghai Public Health Service Policy

on the Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. After one week,

10 BALB/c mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation following

anesthesia with 3% pentobarbital sodium (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis,

MO, USA) via intramuscular injection (1:5 dilution; dose, 10 g/0.1

ml). The bone marrow was collected from their femurs and tibiae,

which was the source of the bone marrow cells. Briefly, the femurs

and tibiae were removed from the mice and the surrounding muscle

tissue was removed from the bones. The intact bones were placed in

70% ethanol for 5 min, for disinfection, and were then washed with

phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Keygentec, Nanjing, China). Both

ends were cut with scissors and the marrow was flushed with PBS.

Clusters within the marrow suspension were dispersed by vigorous

pipetting. The experiment was repeated three times.

HEK293T cells (Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing,

China) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U/ml penicillin

and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen Life Technologies,

Carlsbad, CA, USA), under humidified conditions with 5%

CO2 at 37°C. The H-2d mastocytoma cell line

P815/c (expressing the HBV core antigen) (Nanjing Medical

University) was maintained in our lab (Department of Infectious

Disease, Shanghai JiaoTong University Affiliated Sixth People’s

Hospital), and was cultured under the same conditions as the

HEK293T cells.

Vector construction

The plasmid pcDNA3.1 (-)-Ub-HBcAg was constructed

and maintained in our lab. The Ub-HBcAg cDNA sequence was generated

via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to obtain an 820 bp PCR

product. The paired primer sequences were as follows: Forward,

5-AATGGATCCGGCGGCCGTCGTGCGCGTCGTCGTCGTCGTCGTATGGACAT

TGACCCG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCCAAGCTTGCCACCTCTCAGG CGAAGG-3′

(Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China). The underlined

nucleotides represent the BamHI and HindIII sites,

respectively. The Ub-HBcAg-CTP gene (Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd.) was

inserted into the pMAL-c2X prokaryotic expression vector

(Invitrogen Life Technologies) at the BamHI and

HindIII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA) sites. The

control genes (Ub-HBcAg and HBcAg-CTP) were also amplified via PCR

and cloned separately into pMAL-c2X vectors. The aforementioned

plasmids were further identified via restriction enzyme digestion

and bidirectional DNA sequencing.

Protein expression, purification and

western blotting

The recombinant plasmids were transformed into the

Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3) bacterial strain (Keygentec) to

induce the expression of the recombinant fusion proteins. Following

being lysed by sonication (SM-650D; Shunma, Nanjing, China) and

centrifuged (5415C; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at

8,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatants containing the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP, Ub-HBcAg and HBcAg-CTP fusion proteins were purified

using an amylose resin column (Polysciences, Inc., Eppelheim,

Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and were

evaluated via western blot analysis with an anti-HBcAg mouse

monoclonal antibody (1:500 dilution; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) at 4°C

overnight, and a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse

secondary monoclonal antibody (1:5,000 dilution; Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 2 h at room

temperature. The maltose binding protein-tag (Sangon Biotech Co.,

Ltd.) was ultimately cleaved by the Tobacco Etch Virus protease

(Invitrogen Life Technologies). All proteins were stored at 4°C

until use.

DC generation

DCs were generated according to a previously

published method with certain modifications (17). Briefly, bone marrow cells from the

femurs and tibiae of the mice were collected and cultured at a

density of 2×106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 medium (Hyclone

Biocehmical Product Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) supplemented with

10% FBS, 20 ng/ml recombinant mouse granulocyte-monocyte colony

stimulating factor (rmGM-CSF; Peprotech EC Ltd., London, UK) and 10

ng/ml recombinant mouse interleukin 4 (rmIL-4; Peprotech EC Ltd.).

Following a two day incubation, the adherent cells were divided

into five groups, and four of the groups were cultured for an

additional 72 h in the presence of Ub-HBcAg-CTP, Ub-HBcAg,

HBcAg-CTP and HBcAg (Abcam; all concentrations 20 μg/ml),

respectively. All groups were treated with lipopolysaccharide (20

ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich). On day eight, the non-adherent and loosely

adherent cells were harvested as DCs.

DC morphology, intracellular localization

and western blot analysis

The day five and day eight DCs were observed via

scanning (Quanta 450) and transmission (Tecnai 12) electron

microscopy (FEI Company, Eindhobven, Netherlands). The samples were

treated according to the standard experimental methods (18). The day five DCs were cocultured

with the aforementioned proteins at a concentration of 20

μg/ml for 24 h. Following washing with PBS, the cells were

fixed in 100% pre-chilled methanol (Keygentec). Following an

additional three washes with PBS, the cells were permeabilized with

0.3% Triton X-100 (Keygentec) and blocked with 10% normal goat

serum (Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.). The cells were

subsequently incubated overnight with an anti-HBcAg mAb (1:500

dilution) at 4°C. The cells were then further incubated with goat

anti-mouse fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-Immunoglobulin G

(Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd.) for 1 h at room

temperature. Following washing with PBS and DAPI-staining

(Keygentec), the cells were visualized with a LSM 510 laser

scanning confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany) and

analyzed using LSM image examiner software (Carl Zeiss). The mean

fluorescence intensity (MFI) of the entire view was calculated from

five sites (the four corners and center of each section).

Day five DCs, which were treated as described above,

were also cocultured with or without the specific proteasome

inhibitor MG-132 (10 μmol; Sigma-Aldrich). Following 24 h of

incubation, the DCs were harvested to analyze the level of HBcAg

via western blotting.

Western blot analysis

Following a 24 h incubation the DCs were harvested

and washed twice with PBS. The cells were then gently dispersed

into a single-cell suspension and homogenized using

radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Keygentec). Protein

concentrations were determined using Pierce Bicinchoninic Acid

Protein Assay Reagent kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc., Rockford,

IL, USA). The homogenates were diluted to the desired protein

concentration using 2X SDS-PAGE loading buffer (Invitrogen Life

Technologies). The samples were then boiled and loaded onto

polyacrylamide mini-gels (Invitrogen Life Technologies) for

electrophoresis. The protein samples were then transferred to

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (EMD Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA)

using semi-dry apparatus. The membranes were then incubated with

HBcAg monoclonal human anti-mouse antibody at 4°C overnight,

followed by an incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated

goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G secondary antibody at room

temperature for 2 h. GAPDH was used as the control (GAPDH antibody,

1:1,000, 4°C overnight; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz,

CA, USA). Image-Pro Plus (version, 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Inc,

Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to visualize and quantify the blots.

Gray value was used to compare the differences between the groups.

Gray value=gray value of HBcAg/gray value of GAPDH.

IL-12p70 production, DC immunophenotypic

analysis and T cell proliferation

Day 5 DCs were cocultured with the aforementioned

proteins for 72 h, and the IL-12p70 concentrations in the

supernatants were measured using a standard sandwich ELISA kit

(R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The concentrations were calculated and

expressed as pg/ml. The surface molecules of day eight DCs were

analyzed following incubation with phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled

monoclonal antibodies against mouse CD11c (1:50 dilution), CD80

(1:50 dilution), CD83 (1:100 dilution), CD86 (1:100 dilution) and

MHC class-I (1:40 dilution) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA) at

4°C in the dark for 30 min. Fluorescence analyses were performed on

a COULTER EPICS XL Flow Cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL, USA)

using Expo32-ADC software (Beckman Coulter).

Day five DCs were cocultured with Ub-HBcAg-CTP,

Ub-HBcAg, HBcAg-CTP and HBcAg (20 μg/ml; Abcam). After 72 h, day

eight DCs were pretreated with 25 μg/ml mitomycin C

(Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. T cells were sorted from splenocytes of

allogenenic naïve mice using nylon wool columns (Polysciences.

Inc.) and grown as responder cells in coculture with DCs at various

responder/stimulator (T cell/DC) ratios (5:1, 10:1 and 20:1). The

cells were incubated in a final volume of 100 μl for 96 h,

during which 10 μl Cell Counting Kit-8 solution (Dojindo

Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) was added for 4 h. The absorbance

values of the cultures were read at a wavelength of 450 nm

(Multiskan Ascent; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Intracellular cytokine analysis of

proliferative T cells

Proliferative T cells were stimulated for 6 h in the

presence of 25 μg/ml phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

(Sigma-Aldrich), 1 μg/ml ionomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 1.7

μg/ml monensin (Sigma-Aldrich) (19). The cells were subsequently stained

with a PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-CD3 mAb (eBioscience) and a

FITC-conjugated anti-CD8α mAb (eBioscience) for 15 min at room

temperature. Following fixation and permeabilization using the

Fix/Perm reagents A and B (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) for

15 and 5 min respectively, the cells were incubated with a

PE-labeled anti-interferon (IFN)-γ mAb (eBioscience) for 30 min.

Fluorescence analyses were performed on a COULTER EPICS XL flow

cytometer (Beckman Coulter) with Expo 32-Advanced Digital

Compensation software (Navios™ Cytometer, version 1.0; Beckman

Coulter).

Cytokine secretion and CTL assay

T cells were cocultured with mature DCs in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C for four

days at a T cell/DC ratio of 10:1. The concentrations of various

cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2) in the supernatants were measured using

mouse cytokine ELISA kits (R&D Systems). The concentrations

were expressed as pg/ml.

The P815/c cells were seeded as the target cells,

and previously stimulated T cells were used as the effector cells.

The T cells were cocultured with the P815/c cells at

effector/target ratios of 5:1, 10:1 and 20:1 for 4 h at 37°C in a

humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. HBcAg-specific

CTL activity was measured using a lactate dehydrogenase release

assay (CytTox 9 6 ® non-radioactive cytotoxicity kit;

Promega Corporation, Madison, WI, USA), according to the

manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance values were recorded at

a wavelength of 490 nm (Multiskan Ascent). The percentage

cytotoxicity was calculated as follows: [(experimental release -

effector spontaneous release - target spontaneous release) /

(target maximum release - target spontaneous release)] × 100

(20).

Statistical analysis

Each value in the present study was obtained from a

minimum of three independent experiments and data are expressed as

the mean ± standard deviation. The differences between groups were

determined using one-way analysis of variance. Statistical data

analyses were performed with SPSS 16.0 software (SPSS, Inc.,

Chicago, IL, USA). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Fusion protein expression, purification

and western blotting

The Ub-HBcAg-CTP, Ub-HBcAg and HBcAg-CTP fusion gene

constructs were 813, 780 and 585 bp in size, respectively, as

determined by PCR amplification. All the target prokaryotic

expression plasmids were successfully constructed and identified by

restriction endonuclease analysis and bidirectional DNA sequencing

(data not shown). The purified fusion proteins were identified to

be ~80% pure via SDS-PAGE analysis (Fig. 1A) and the products were further

confirmed by western blot analysis (Fig. 1B).

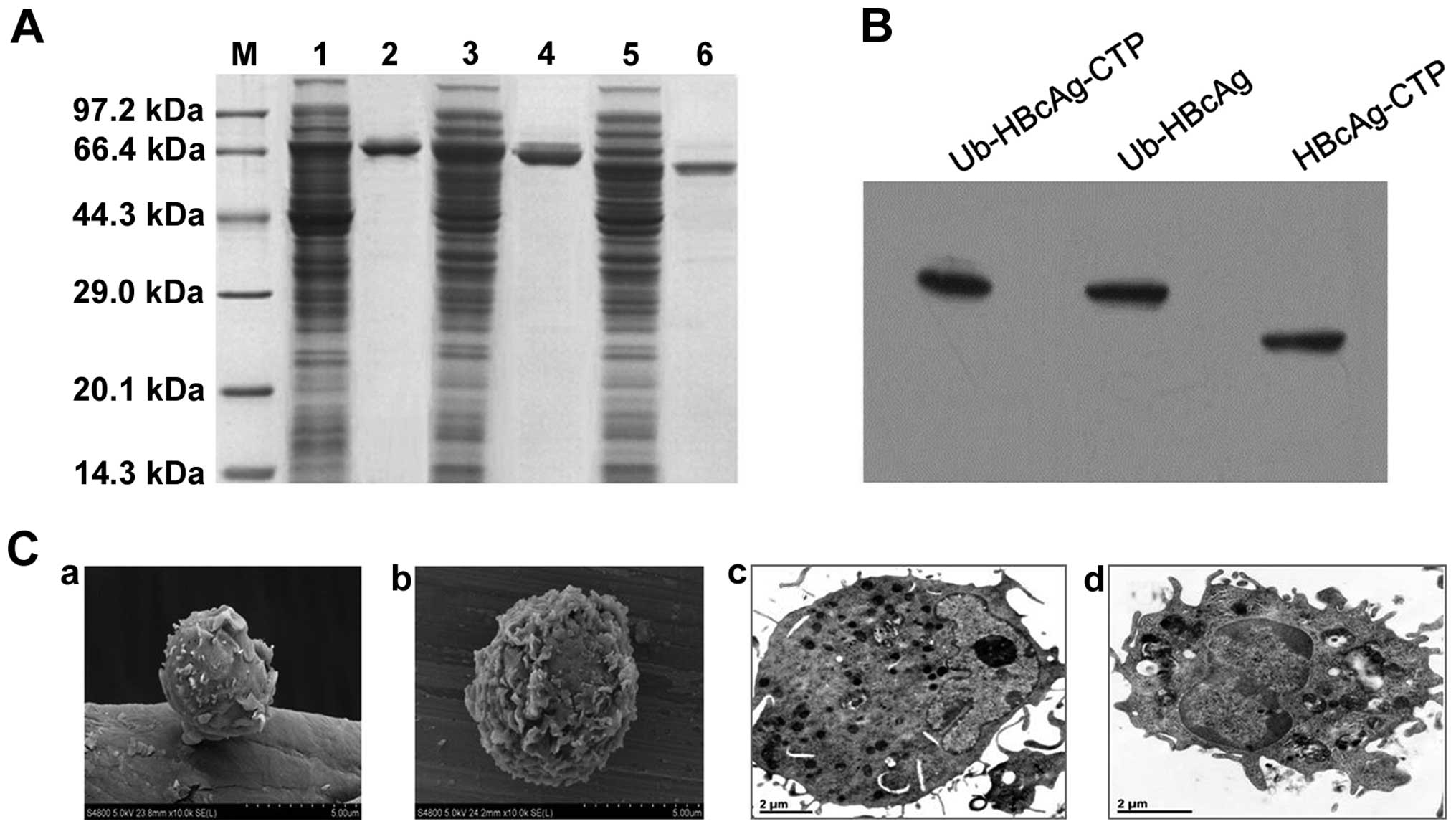

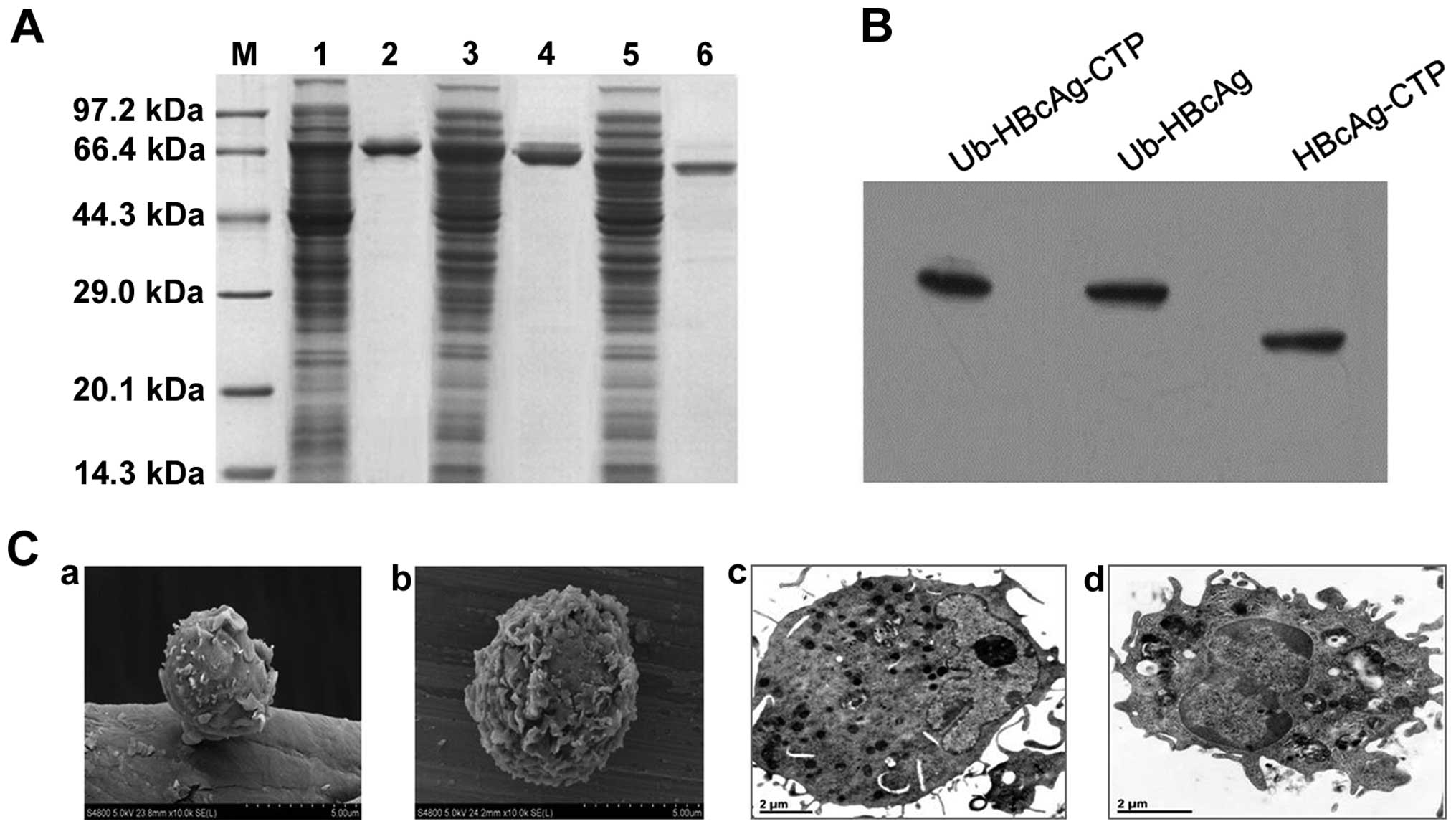

| Figure 1Fusion protein expression,

purification, western blot analysis and DC morphology. (A)

Expression and purification of fusion proteins by SDS-PAGE. Lanes:

M, molecular weight standards; 1 and 2, expression and purification

of MBP-Ub-HBcAg-CTP recombinant protein, respectively; 3 and 4,

expression and purification of MBP-Ub-HBcAg recombinant protein,

respectively; 5 and 6, expression and purification of MBP-HBcAg-CTP

recombinant protein, respectively. (B) Purified fusion proteins

were analyzed via western blotting using anti-HBcAg monoclonal

antibody. (C) Ultrastructures of day five and day eight DCs were

observed using (a and b) scanning electron microscopy

(magnification, ×5,000) and (c and d) transmission electron

microscopy (magnification, ×20,000), respectively. HBcAg, hepatitis

B virus core antigen; DC, dendritic cell; CTP, cytoplasmic

transduction peptide; MBP, maltose binding protein; Ub,

ubiquitin. |

DC maturation, cytoplasmic localization

and western blotting

On the DC surfaces, increased numbers of ruffes and

rough dendrites were observed by scanning electron microscopy.

Similarly, the morphological characteristics of mature DCs were

detected by transmission electron microscopy, and identified larger

nuclei, as well as increased numbers of mitochondria and ribosomes

(Fig. 1C).

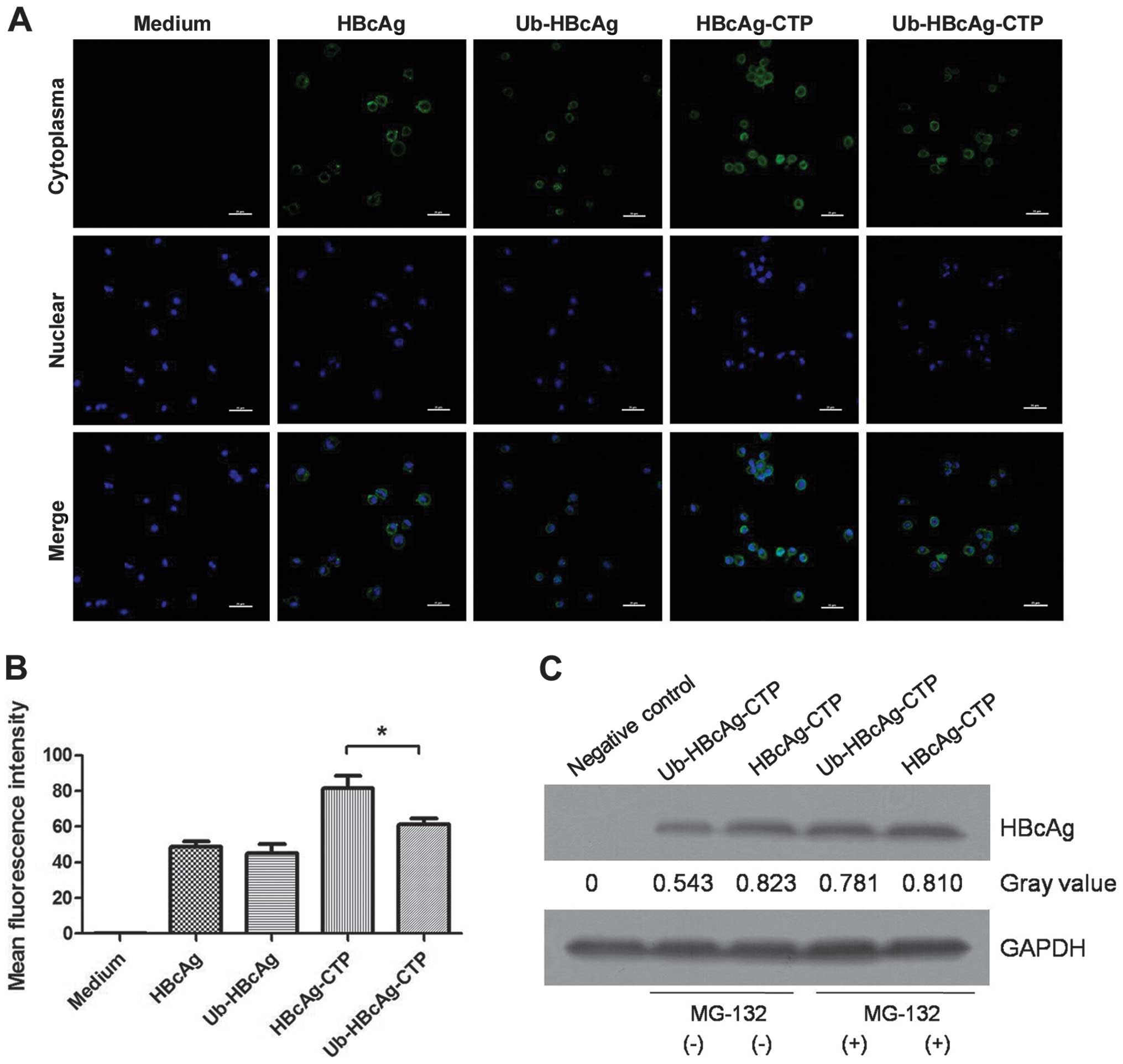

Immunofluorescent staining and confocal microscopy

were used to characterize the intracellular localization of the

various proteins in DCs. The HBcAg protein was identified in the

cytoplasm of DCs treated with Ub-HBcAg-CTP and HBcAg-CTP via the

presence of green fluorescence (FITC-labeled HBcAG) (Fig. 2A). This fluorescence was clearly

distinguished from the nuclear-specific counterstain, DAPI. Green

fluorescence was observed to aggregate primarily on the DC

cytomembranes in the Ub-HBcAg and HBcAg-treated groups (Fig. 2A), demonstrating the potent

transduction potential and cytoplasmic localization mediated by the

CTP peptide. The green fluorescence intensity detected in the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP group was weaker than that in the HBcAg-CTP group,

indirectly demonstrating the lower HBcAg levels in the former group

(Fig. 2B). Furthermore, the levels

of HBcAg were detected in the Ub-HBcAg-CTP and HBcAg-CTP groups

using western blot analysis to determine the rates of intracellular

degradation. As expected, HBcAg levels in Ub-HBcAg-CTP-group were

lower than those in the HBcAg-CTP-group, but recovered to the same

level as those of HBcAg following the addition of MG-132 (Fig. 2C).

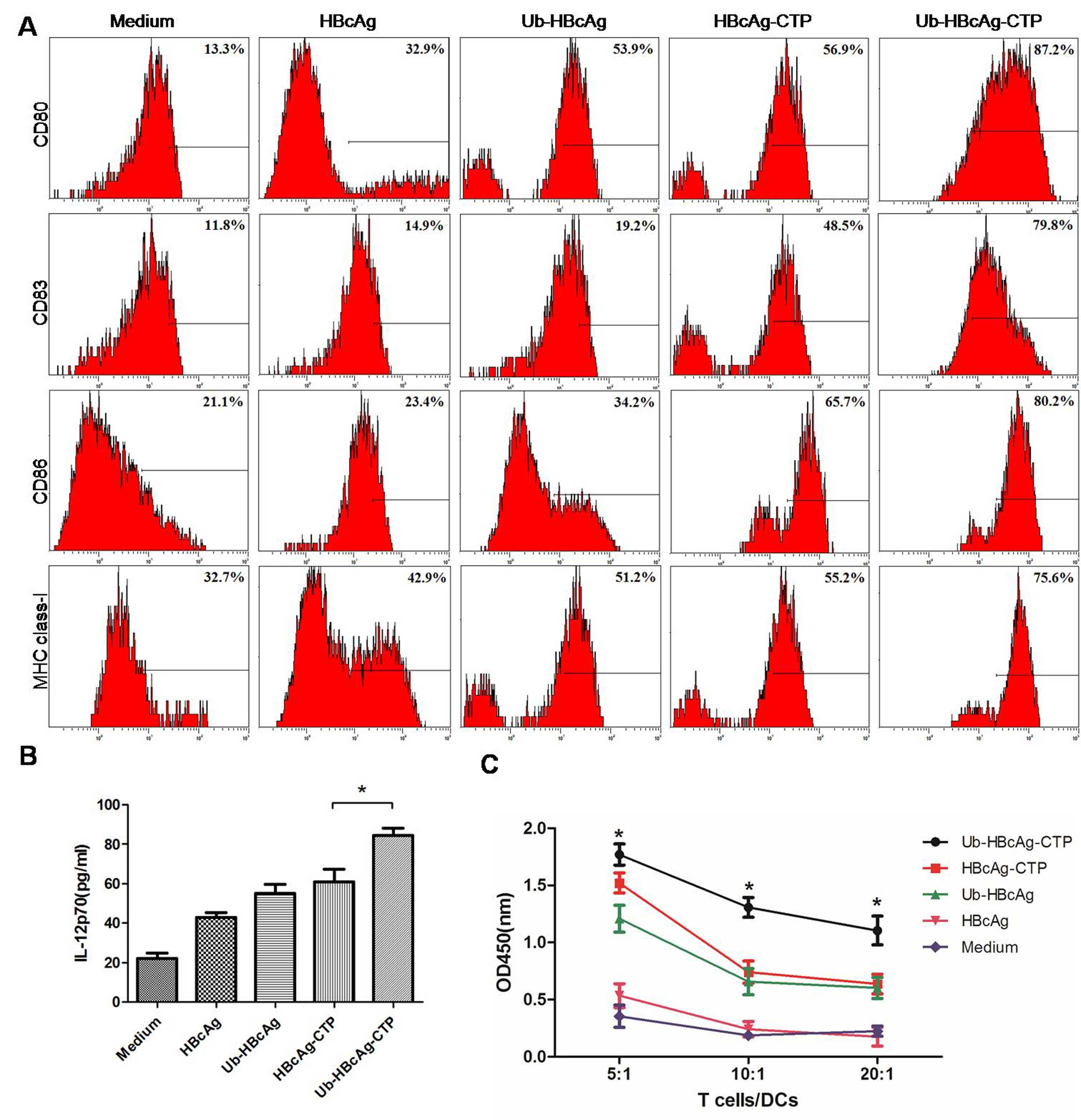

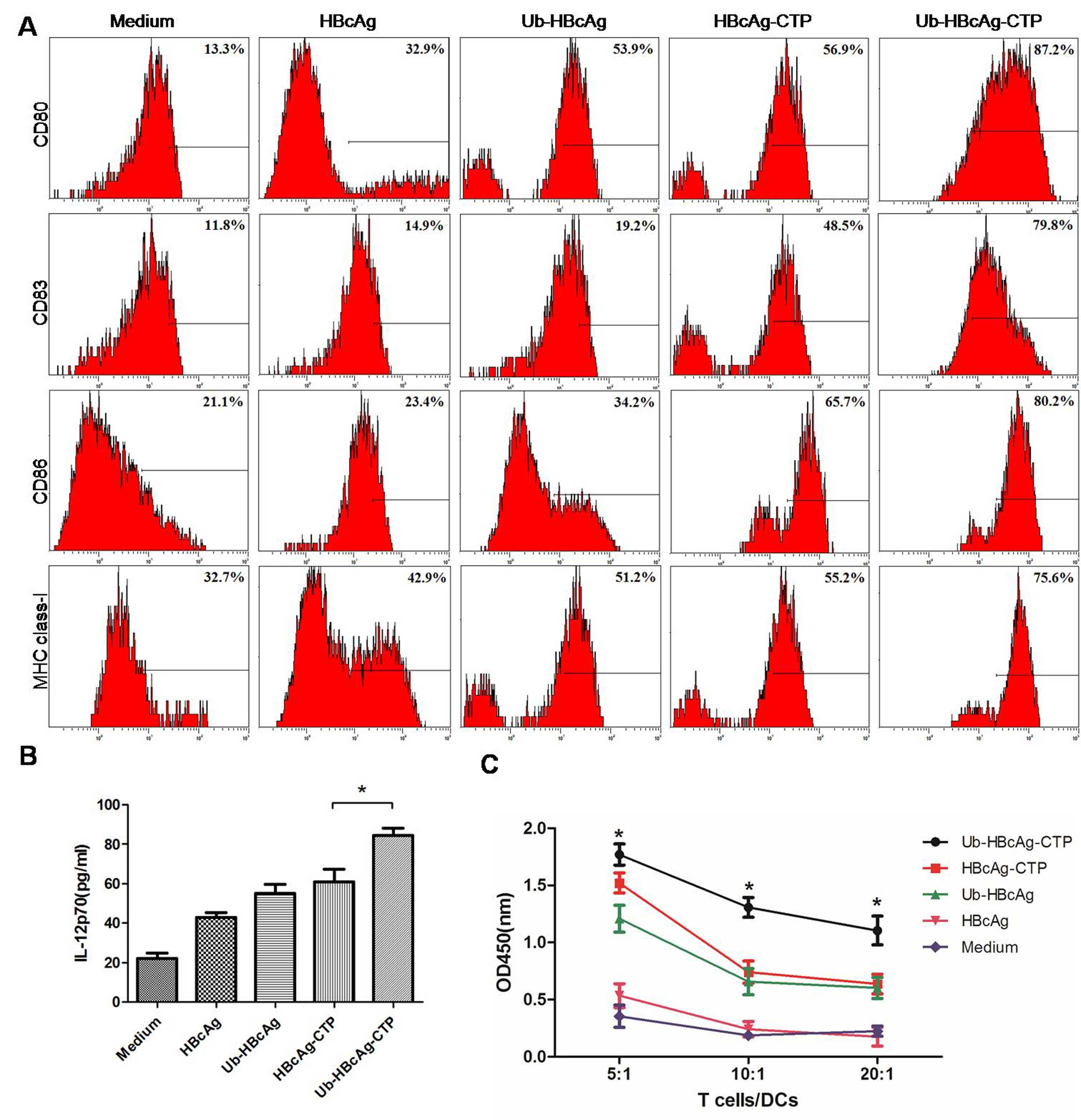

Ub-HBcAg-CTP leads to increased IL-12

production and surface molecule expression

IL-12 is considered a vital cytokine, produced by

DCs, and is a key cytokine involved in the induction of Type-1

immune responses (21). The

IL-12p70 concentrations were assayed in the various protein-treated

groups. The results demonstrated that DCs cocultured with

Ub-HBcAg-CTP secreted significantly greater quantities of IL-12p70

(84.38±9.625 pg/ml) than those of the other groups (P<0.05;

Fig. 3B). However, no differences

were identified among the other groups. Additionally, following

treatment, the quantity of DCs (CD11c+) in the culture

was ~85% (flow cytometric analysis) and the surface molecules CD80,

CD83, CD86 and MHC class-I were highly expressed on the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP-treated DCs (Fig.

3A).

| Figure 3DC immunophenotypic analysis,

detection of IL-12p70 production and T-cell proliferation. (A)

Surface molecules on DCs (CD80, CD83, CD86, and major

histocompatibility complex class-I) were detected using flow

cytometry. Surface molecule expression was significantly higher in

the Ub-HBcAg-CTP group than in the other groups.

*P<0.05, **P<0.01. (B) IL-12p70

concentrations in supernatants of DCs were measured via ELISA. Data

is expressed as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05 vs. HBcAg-CTP

group. (C) T-cell proliferation capacities at various

responder/stimulator (T cell/DC) ratios. Data is expressed as the

mean ± SD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs.

HBcAg-CTP group. HBcAg, hepatitis B virus core antigen; DC,

dendritic cell; CTP, cytoplasmic transduction peptide; MBP, maltose

binding protein; Ub, ubiquitin; SD, standard deviation; IL,

interleukin; CD, cluster of differentiation; OD, optical

density. |

T-cell proliferation

T cells were cocultured with DCs, which had been

pulsed with various proteins in order to analyze their T-cell

proliferation capacities. It was identified that the T-cell

proliferation capacity was markedly higher in the Ub-HBcAg-CTP

group (P<0.05; Fig. 3C), and

was enhanced by lower T cell/DC ratios.

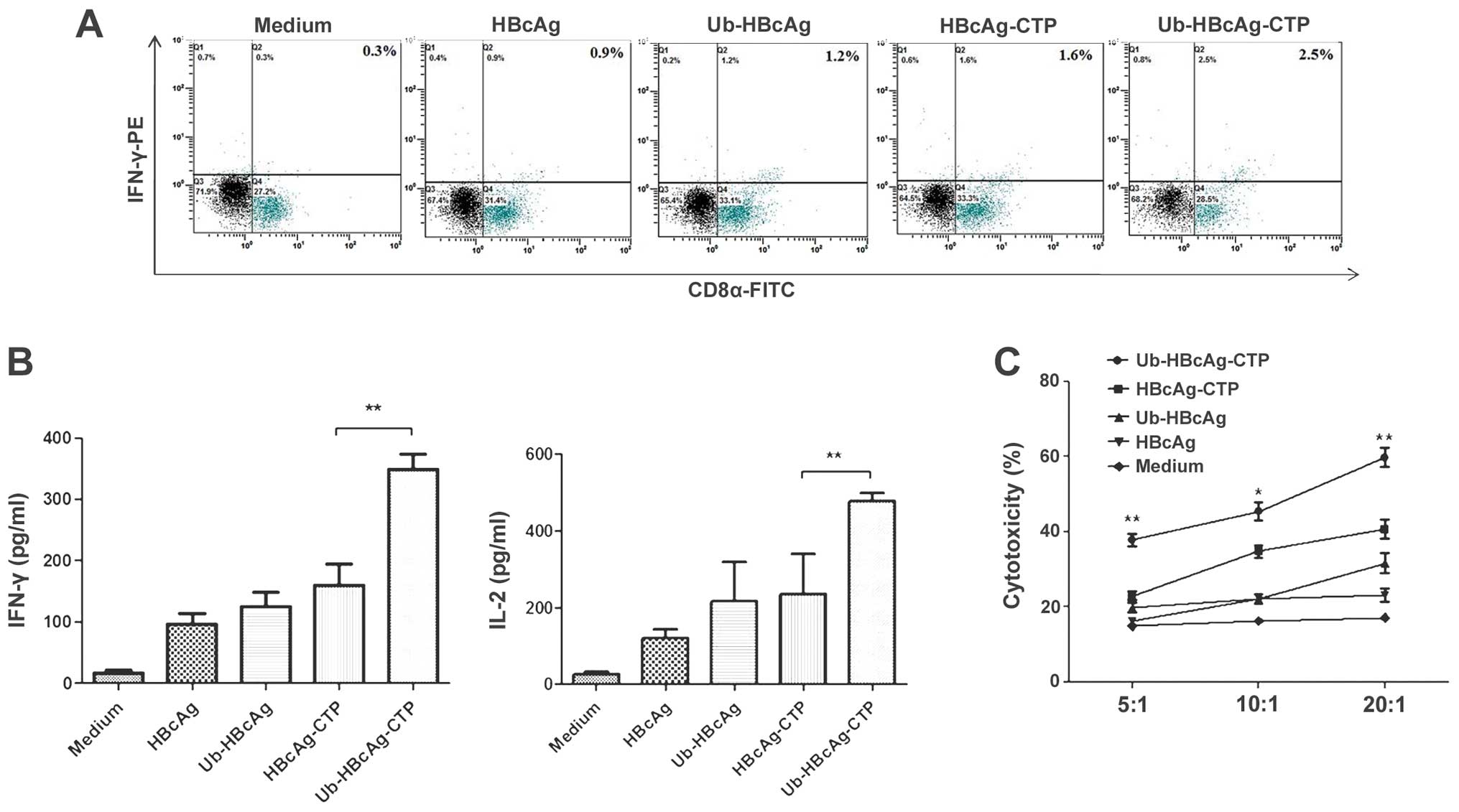

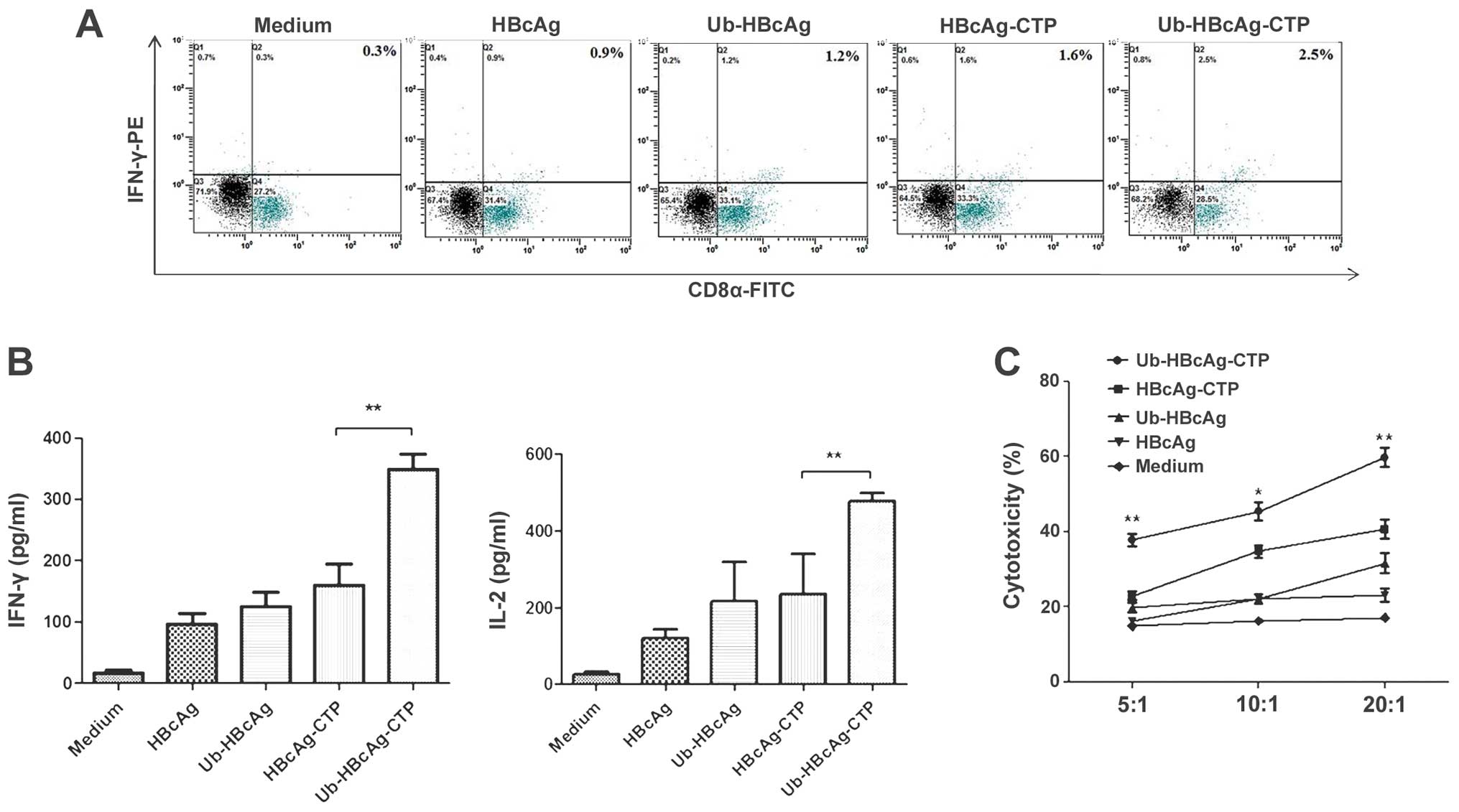

Ub-HBcAg-CTP leads to increased IFN-y

production by CD8+ T cells in vitro

The levels of CD8+ T cell-produced IFN-γ

were measured by intracellular staining and fow cytometry. The

cells were stained with an anti-CD3 mAb to identify T cells within

the cell populations, and the samples were subsequently subjected

to intracellular staining. As shown in Fig. 4A, the percentage of specific

IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells was greater in the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP group than in the other groups (P<0.05), suggesting

that Ub-HBcAg-CTP-treated DCs may enhance the generation of

specific CTLs.

| Figure 4Intracellular cytokine analysis of

proliferative T cells, cytokine production and CTL assay. (A)

Specific IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells were detected by

flow cytometry. (B) Levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 in the supernatants of

proliferative T cells stimulated by various protein-treated DCs.

Data is expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

*P<0.05. (C) Specific CTL activity was measured by

lactate dehydrogenase release assay. The proliferative T cells were

incubated with target cells at various effector/target ratios (5:1,

10:1 and 20:1). CTL activity was indicated as the mean percentage

of specific lysis (mean ± standard deviation).

*P<0.05, **P<0.01, compared with

control. CTL, cytotoxic T lymphocytes; IFN-γ, interferon-γ; IL,

interleukin; CD, cluster of differentiation; DC, dendritic cell;

HBcAg, hepatitis B virus core antigen; CTP, cytoplasmic

transduction peptide; Ub, ubiquitin; FITC, fluorescein

isothiocyanate. |

Ub-HBcAg-CTP-induces the enhancement of

cytokine production and CTL activity

Subsequently, the levels of IFN-γ and IL-2 secreted

by T cells were measured. The Ub-HBcAg-CTP group produced higher

levels of IFN-γ (348.8±24.78 pg/ml) and IL-2 (476.5±20.81pg/ml)

than those in the other groups (P<0.05, Fig. 4B). Clearer CTL responses were

detected at differing effector/target ratios in the Ub-HBcAg-CTP

group, compared with those in the other groups (Fig. 4C). These results suggested that

Ub-HBcAg-CTP may induce marked specific CTL responses, which was

consistent with the high level of IFN-γ expressed in

CD8+ T cells.

Discussion

Various immunotherapeutic strategies have been

developed to eliminate HBV; however, these strategies have not had

a substantial impact (22). The

host antiviral immune response, particularly CTL activity, to

HBV-antigens has been established as the main determinant in the

processes of viral replication and clearance (23,24).

Therefore, the induction of HBV-specific CD8+ T cells is

a current goal in the development of effective immune-based

therapeutic interventions for the treatment of HBV infection,

intended to enhance antigen presentation in order to induce broad

CTL responses.

C D8+ T cell priming requires the direct

and/or cross-presentation of antigenic peptides on MHC class I

molecules by APCs (25). DCs are

among the most potent APCs and possess a unique capacity to

interact with naïve T cells and consequently induce immune

responses (26). Patients with

chronic HBV infections generally exist in an immune-comprised

state, comprising immune tolerance with impaired DC function

(27,28). Therefore, efforts should be made to

enhance the antigen presenting capacities of DCs.

CTP, which is derived from PTD, was verified to

facilitate specific cytoplasmic localization and possess potent

membrane transduction potential (16). Accordingly, cytoplasmic functional

molecules may be more efficiently targeted by CTP-mediated delivery

(16,29). In the present study, a

Ub-HBcAg-CTP-expressing vector was constructed in order to achieve

increased transduction into cells. Following transduction, the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP fusion protein was detected via confocal microscopy,

in order to characterize the intracellular localization. It was

revealed that CTP-containing fusion proteins remained primarily in

the cytoplasm of DCs, whereas proteins without CTP were detected

primarily on the cell surface. This result confirmed that target

proteins were able to be transported efficiently into the DC

cytoplasm via CTP, thus providing a basis for the further

verification of protein immunogenicity.

Ub is a well-conserved and ubiquitously expressed

protein that is conjugated to target proteins (30). It is best known for its role as a

marker for protein destruction by the UPS (31). In the present study, the MFI of

Ub-HBcAg-CTP-transduced DCs was weaker than that of the HBcAg-CTP

group, thus indirectly demonstrating the degradation of HBcAg.

Furthermore, HBcAg was quantitatively measured by western blot

analysis. It was identified that the Ub-tagged HBcAg protein was at

a lower level in the absence of MG-132 (specific proteasome

inhibitor), indicating rapid recognition of the fusion protein by

the UPS, leading to HBcAg degradation. Ub-mediated antigen

processing has been widely used to enhance immune responses in

infectious disease and cancer studies (32,33).

A previous study confirmed that Ub-fused proteins may improve CTL

activity by promoting the introduction of the encoded protein into

the MHC class I pathway (34).

HBcAg, which possesses unique immunological features, elicits

prominent immune responses during chronic HBV infection (35). Therefore, a Ub-modified HBcAg gene

was amplified.

In the present study, the immunomodulatory effects

of these proteins on bone marrow-derived DC (BMDC) development

in vitro was investigated. It was identified that

Ub-HBcAg-CTP-treated BMDCs expressed higher levels of surface

molecules. Additionally, the associated mature DCs secreted higher

levels of IL-12 in response to various intracellular pathogenic

infections. This response has a key role in the initiation of

specific T cell-mediated immune responses and the promotion of

T-helper (Th)1 cell activation and differentiation (21). Accordingly, IL-12p70 production was

evaluated. As desired, the DC production of IL-12p70 was markedly

increased in response to Ub-HBcAg-CTP treatment, compared with that

in the other treatment groups. The DC morphology in the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP group was also observed to include numerous

mitochondria, as well as increased quantities of ribosomes and

rough endoplasmic reticulum. The results demonstrated that the

Ub-modified HBcAg protein may facilitate DC maturation and increase

MHC class-I expression.

Th1 cells are known to produce large quantities of

Type-1 cytokines, including IFN-γ and IL-2, whereas Th2 cells

produce large quantities of Type-2 cytokines, including IL-4 and

IL-10 (36). In the current study,

the secretion of Type-1 cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2) was demonstrated

to be significantly increased in the Ub-HBcAg-CTP group, which

indicated that Ub-HBcAg-CTP-pulsed DCs had a tendency to promote

Th1 polarization and activate cell-mediated immunity. In addition,

in order to determine whether this maturation sufficiently

modulated CD8+ T cells, the production of IFN-γ was

measured via intracellular cytokine staining. The cells in the

Ub-HBcAg-CTP group were found to induce a greater quantity of

IFN-γ+CD8+ T cells and more robust specific

CTL activity. The specific cytotoxic response assay confirmed the

enhancing effect of Ub-HBcAg-CTP on specific CTL responses. The

results demonstrated that Ub-HBcAg-CTP fusion proteins may enhance

the capacity of T cells to proliferate, secrete cytokines and

develop into CTLs in vitro. Based on these findings, it is

possible that the role of the Ub-HBcAg-CTP fusion protein in the

induction of specific CTLs may be attributed to the fact that

UPS-degraded antigenic peptides are presented by

cell-surface-expressed MHC class-I molecules and are, therefore,

specifically recognized by CTLs.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

Ub-HBcAg-CTP fusion proteins do not only increase the expression of

MHC class-I molecules, but also enhance the presentation of

antigenic peptides and elicit robust HBcAg-specific CTL immune

responses in vitro. Although the data presented in the

present study may not be fully translatable to studies in humans,

these findings may suggest a potential therapeutic strategy for

chronically infected HBV patients.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81270502)

and the Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant no.

11ZR1427100).

References

|

1

|

Ganem D and Prince AM: Hepatitis B virus

infection - natural history and clinical consequences. New Engl J

Med. 350:1118–1129. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Shepard CW, Simard EP, Finelli L, Fiore AE

and Bell BP: Hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and

vaccination. Epidemiol Rev. 28:112–125. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Raney AK, Hamatake RK and Hong Z: Agents

in clinical development for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B.

Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 12:1281–1295. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Rehermann B: Immune responses in hepatitis

B virus infection. Semin Liver Dis. 23:21–38. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Kakimi K, Isogawa M, Chung J, Sette A and

Chisari FV: Immunogenicity and tolerogenicity of hepatitis B virus

structural and nonstructural proteins: implications for

immunotherapy of persistent viral infections. J Virol.

76:8609–8620. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Steinman RM and Hemmi H: Dendritic cells:

translating innate to adaptive immunity. Curr Top Microbiol

Immunol. 311:17–58. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Pozzi LA, Maciaszek JW and Rock KL: Both

dendritic cells and macrophages can stimulate naive CD8 T cells in

vivo to proliferate, develop effector function, and differentiate

into memory cells. J Immunol. 175:2071–2081. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Almand B, Resser JR, Lindman B, et al:

Clinical significance of defective dendritic cell differentiation

in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 6:1755–1766. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Glickman MH and Ciechanover A: The

ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake

of construction. Physiol Rev. 82:373–428. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Shabek N and Ciechanover A: Degradation of

ubiquitin: the fate of the cellular reaper. Cell Cycle. 9:523–530.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Hershko A and Ciechanover A: The ubiquitin

system. Annu Rev Biochem. 67:425–479. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Warnatsch A, Bergann T and Krüger E:

Oxidation matters: the ubiquitin proteasome system connects innate

immune mechanisms with MHC class I antigen presentation. Mol

Immunol. 55:106–109. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Burr ML, Boname JM and Lehner PJ: Studying

ubiquitination of MHC class I molecules. Methods Mol Biol.

960:109–125. 2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Schödel F, Moriarty AM, Peterson DL, et

al: The position of heterologous epitopes inserted in hepatitis B

virus core particles determines their immunogenicity. J Virol.

66:106–114. 1992.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Singh TR, Garland MJ, Cassidy CM, et al:

Microporation techniques for enhanced delivery of therapeutic

agents. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 4:1–17. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kim D, Jeon C, Kim JH, et al: Cytoplasmic

transduction peptide (CTP): new approach for the delivery of

biomolecules into cytoplasm in vitro and in vivo. Exp Cell Res.

312:1277–1288. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Huang Y, Chen Z, Jia H, Wu W, Zhong S and

Zhou C: Induction of Tc1 response and enhanced cytotoxic T

lymphocyte activity in mice by dendritic cells transduced with

adenovirus expressing HBsAg. Clin Immunol. 119:280–290. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Tatu RF, Anuşca DN, Groza SŞ, et al:

Morphological and functional characterization of femoral head

drilling-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Rom J Morphol Embryol.

55:1415–1422. 2014.

|

|

19

|

Crawford TQ, Ndhlovu LC, Tan A, et al:

HIV-1 infection abrogates CD8+ T cell mitogen-activated protein

kinase signaling responses. J Virol. 85:12343–12350. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Chen JH, Yu YS, Chen XH, Liu HH, Zang GQ

and Tang ZH: Enhancement of CTLs induced by DCs loaded with

ubiquitinated hepatitis B virus core antigen. World J

Gastroenterol. 18:1319–1327. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Giermasz AS, Urban JA, Nakamura Y, et al:

Type-1 polarized dendritic cells primed for high IL-12 production

show enhanced activity as cancer vaccines. Cancer Immunol

Immunother. 58:1329–1336. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Wang L, Zou ZQ, Liu CX and Liu XZ:

Immunotherapeutic interventions in chronic hepatitis B virus

infection: a review. J Immunol Methods. 407:1–8. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Tsai SL, Sheen IS, Chien RN, et al:

Activation of Th1 immunity is a common immune mechanism for the

successful treatment of hepatitis B and C: tetramer assay and

therapeutic implications. J Biomed Sci. 10:120–135. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Phillips S, Chokshi S, Riva A, Evans A,

Williams R and Naoumov NV: CD8(+) T cell control of hepatitis B

virus replication: direct comparison between cytolytic and

noncytolytic functions. J Immunol. 184:287–295. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Schliehe C, Bitzer A, van den Broek M and

Groettrup M: Stable antigen is most effective for eliciting

CD8+ T-cell responses after DNA vaccination and

infection with recombinant vaccinia virus in vivo. J Virol.

86:9782–9793. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chiang CL, Balint K, Coukos G and

Kandalaft LE: Potential approaches for more successful dendritic

cell-based immunotherapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. Jan 2–2015.Epub

ahead of print. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tavakoli S, Mederacke I, Herzog-Hauff S,

et al: Peripheral blood dendritic cells are phenotypically and

functionally intact in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.

Clin Exp Immunol. 151:61–70. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Op den Brouw ML, Binda RS, van Roosmalen

MH, et al: Hepatitis B virus surface antigen impairs myeloid

dendritic cell function: a possible immune escape mechanism of

hepatitis B virus. Immunology. 126:280–289. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar :

|

|

29

|

Chen HZ, Wu CP, Chao YC and Liu CY:

Membrane penetrating peptides greatly enhance baculovirus

transduction efficiency into mammalian cells. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 405:297–302. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Schaefer A, Nethe M and Hordijk PL:

Ubiquitin links to cytoskeletal dynamics, cell adhesion and

migration. Biochem J. 442:13–25. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Gao G and Luo H: The ubiquitin-proteasome

pathway in viral infections. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 84:5–14.

2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Wang QM, Kang L and Wang XH: Improved

cellular immune response elicited by a ubiquitin-fused ESAT-6 DNA

vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbiol Immunol.

53:384–390. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Pal A and Donato NJ: Ubiquitin-specific

proteases as therapeutic targets for the treatment of breast

cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 16:4612014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Rodriguez F, Zhang J and Whitton JL: DNA

immunization: ubiquitination of a viral protein enhances cytotoxic

T-lymphocyte induction and antiviral protection but abrogates

antibody induction. J Virol. 71:8497–8503. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Cao T, Lazdina U, Desombere I, et al:

Hepatitis B virus core antigen binds and activates naive human B

cells in vivo: studies with a human PBL-NOD/SCID mouse model. J

Virol. 75:6359–6366. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Chen W, Shi M, Shi F, et al: HBcAG-pulsed

dendritic cell vaccine induces Th1 polarization and production of

hepatitis B virus-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Hepatol Res.

39:355–365. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|