Introduction

Ovarian cancer (OC), which frequently occurs in

postmenopausal women (1), is a

cancer with no apparent symptoms until it reaches an advanced

stage. The symptoms include bloating, abdominal swelling, pelvic

pain and loss of appetite (2). The

three most common OC subtypes are high-grade serous carcinomas, sex

cord stromal tumors and germ cell tumors (3), which may metastasize to the

peritoneum, liver, lungs or lymph nodes (4). OC is difficult to detect and

metastasizes early in disease progression; therefore, patients with

OC frequently have a poor prognosis (5). Globally, OC affects 1.2 million women

and led to 161,100 mortalities in 2015 (6,7).

Thus, obtaining an improved understanding of OC progression and

recurrence is of great importance for improving its prognosis.

Previously, genes affecting OC were identified,

including p21-activated kinase 4 (Pak4), cyclin E1

(CCNE1), RNA binding motif protein 3 (RBM3), YY1

associated protein 1 (YAP) and prominin-1 (CD133).

Pak4 overexpression has been reported to contribute to OC

cell migration, invasion and proliferation, thus making it a

promising prognostic indicator and therapeutic target (8). CCNE1 amplification has been

demonstrated to markedly reduce disease-free survival and overall

survival, thus indicating that CCNE1-targeted treatment may

benefit patients with OC who have upregulated CCNE1

expression (9,10). In epithelial ovarian cancer,

RBM3 expression has been associated with cisplatin

sensitivity and correlated with a positive patient prognosis

(11). Furthermore, YAP has

been associated with cell growth and tumorigenesis, and its

coexpression with TEA domain transcription factor 4 serves as a

predictor of a poor outcome (12,13).

CD133 also serves as a predictor of poor OC patient survival, thus

suggesting that it may serve as a biomarker of cancer stem cells

during disease (14). However, the

further identification of prognostic indicators and their potential

uses is required.

In recent years, bioinformatics analysis of

expression profile data has been gradually used to examine the

pathogenesis of human diseases (15). It is known that the progress of a

disease is usually mediated by multiple relevant genes and not by a

single gene (16,17). Therefore, the present study was

designed to mine subnetwork features and build a model to assess OC

recurrence risk. In the present study, OC expression profiles were

downloaded from a public database, and differentially expressed

genes (DEGs) were analyzed and functionally enriched. Following

identification of a functional subnetwork, a random forest

classifier was constructed and validated. It was considered that

this constructed classifier may provide an improved approach for

predicting the prognoses of patients with OC.

Materials and methods

Data source

RNA sequence data from 307 OC samples and their

corresponding clinical data (including patient vital status and

overall survival) were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas

(TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov)

database. Based on patient vital status, 180 recurrent samples and

72 disease-free samples were identified. Additionally, the GSE44104

dataset [including 20 recurrent and 40 non-recurrent OC samples;

platform, (HG-U133_Plus_2) Affymetrix Human Genome U133 Plus 2.0

Array, Affymetrix; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA] and the GSE49997 dataset (including 204 OC samples; platform,

GPL2986 ABI Human Genome Survey Microarray version 2, Applied

Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) were obtained from the

Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) database and utilized

as validation sets.

Data preprocessing and DEG

screening

Using a z-score algorithm (18), the expression value of each gene

was normalized to a normal distribution (mean=0; variance=1). The

samples were subsequently analyzed using the differential

expression via distance synthesis (DEDS) algorithm, which may be

applied to obtain differential expression levels via the distance

synthesis of relevant data (19).

This approach was used to screen DEGs in the recurrent samples

relative to the disease-free samples.

Functional enrichment analysis

Gene ontology (GO; http://www.geneontology.org) analysis may be used to

predict the potential functions of gene products (20). Using GO Term Finder (http://search.cpan.org/dist/GO-TermFinder/) as

previously described (21),

upregulated and downregulated genes were separately enriched.

Functional terms with P<0.05 and an association with at least

three genes were selected as significant terms.

Weighted gene coexpression network

analysis (WGCNA)

Genes may jointly influence alterations in

functional terms through their interactions, with functional

consistencies between genes also confirmed by significant

expression level correlations. To systematically analyze how DEGs

with similar expression profiles co-affect OC prognosis, WGCNA

(22) was performed. Based on the

obtained weighted gene coexpression levels, DEG coexpression was

suggested to be significantly associated with OC prognosis. To

further identify the genes that were able to differentiate between

patients with OC with different prognoses, the verified DEG

protein-protein interaction (PPI) pairs were used to construct a

PPI network using BioNet 1.24.1 package (http://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/BioNet.html).

Subnetwork analysis and classifier

construction

The BioNet package (http://bionet.bioapps.biozentrum.uni-wuerzburg.de)

provides an extensive framework that enables functional subnetworks

to be isolated from biological networks. Using the BioNet package

in R 3.1.0 (23), as previously

described (24), subnetwork

analysis was conducted for the PPI network with the P-value/false

discovery rate set to 0.01. With the subnetwork nodes as feature

genes, a random forest classifier (25) was constructed. For sample labels

(recurrence/no recurrence), true and false positive rates were

calculated and combined with leave-one-out cross validation

(26). Additionally, a receiver

operating characteristic (ROC) curve was constructed (27) to evaluate the classification

efficiency of the random forest classifier.

Validation using other independent datasets. To

confirm that the subnetwork nodes were able to effectively

differentiate between patients with OC with different prognoses,

the classification efficiency of the random forest classifier for

the validation set (GSE44104) was analyzed and presented using a

confusion matrix. Additionally, a Kaplan-Meier (KM) survival

analysis (28) was performed and

combined with the clinical information belonging to the TCGA

dataset.

Results

DEG screening

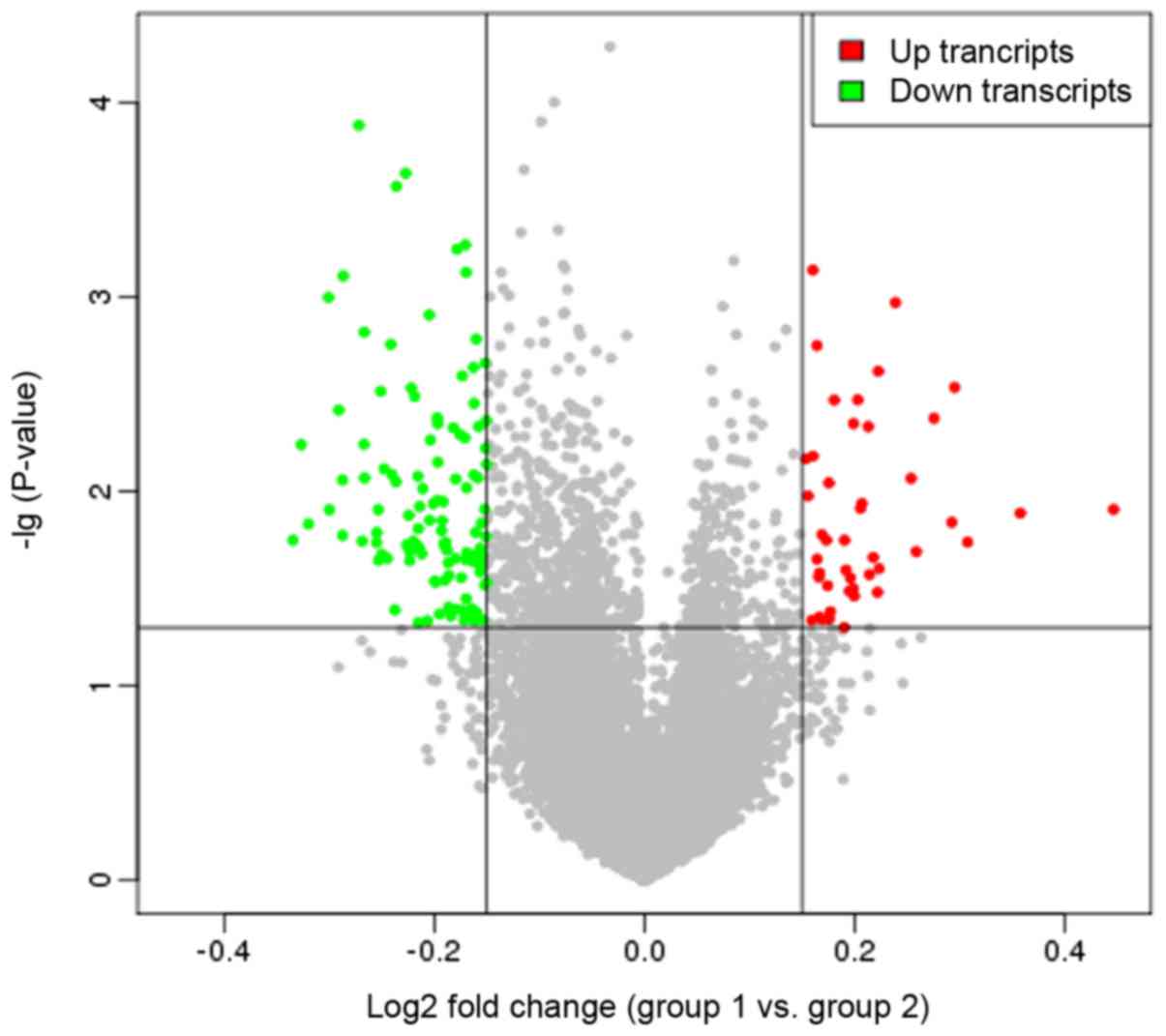

Following implementation of the DEDS algorithm, a

total of 44 upregulated and 117 downregulated genes were identified

in the recurrent samples relative to the non-recurrent samples,

with more downregulated genes identified compared with upregulated

genes. Additionally, a volcano plot was constructed to examine DEG

expression distributions (Fig.

1).

Functional enrichment analysis

Using the GO Term Finder, significant GO terms were

enriched for the upregulated and downregulated genes separately.

For the upregulated genes, the enriched GO terms were primarily

associated with the ‘regulation of synapse assembly’

(P=1.04×10−7), ‘regulation of synapse organization’

(P=5.26×10−7), and ‘regulation of synapse structure or

activity’ (P=5.71×10−7; Table IA). The downregulated genes were

associated with ‘single-multicellular organism process’

(P=4.11×10−5), ‘multicellular organismal process’

(P=5.14×10−5) and ‘positive regulation of steroid

hormone biosynthetic process’ (P=3.83×10−3; Table IB), which included cytochrome P450

family 17 subfamily A member 1 (CYP17A1).

| Table I.Significant functional terms enriched

for the upregulated and downregulated genes. |

Table I.

Significant functional terms enriched

for the upregulated and downregulated genes.

| A, Upregulated

genes |

|---|

|

|---|

| Term | Corrected

P-value | Count | Genes |

|---|

| Regulation of

synapse assembly |

1.04×10−7 | 5 | DKK1, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| regulation of

synapse organization |

5.26×10−7 | 5 | DKK1, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| regulation of

synapse structure or activity |

5.71×10−7 | 5 | DKK1, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| synapse

assembly |

2.08×10−6 | 5 | DKK1, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| positive regulation

of synapse assembly |

6.78×10−6 | 4 | LINGO2, TPBG,

SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| synapse

organization |

2.23×10−5 | 5 | DKK1, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| regulation of

nervous system development |

2.72×10−4 | 6 | LRRC7, DKK1,

LINGO2, TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| positive regulation

of nervous system development |

4.44×10−4 | 5 | LRRC7, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| regulation of

developmental process |

1.131×10−3 | 8 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, BVES, LINGO2, MEGF10, SLITRK5, TPBG |

| regulation of

multicellular organismal development |

1.96×10−3 | 7 | LRRC7, DKK1,

LINGO2, MEGF10, TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| positive regulation

of developmental process |

2.64×10−3 | 6 | LRRC7, DKK1,

LINGO2, TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| system

development |

2.84×10−3 | 10 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, WDR69, BVES, C8orf85, LINGO2, MEGF10, TPBG,

SLITRK5 |

| regulation of

multicellular organismal process |

3.63×10−3 | 8 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, BVES, LINGO2, MEGF10, SLITRK5, TPBG |

| single-organism

developmental process |

5.75×10−3 | 11 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, WDR69, BVES, C8orf85, LINGO2, MEGF10, MMP7, TPBG,

SLITRK5 |

| developmental

process |

6.65×10−3 | 11 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, WDR69, BVES, C8orf85, LINGO2, MEGF10, MMP7, TPBG,

SLITRK5 |

|

single-multicellular organism process |

8.10×10−3 | 11 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, WDR69, BVES, C8orf85, LINGO2, MEGF10, MMP7, TPBG,

SLITRK5 |

| positive regulation

of multicellular organismal process |

8.16×10−3 | 6 | LRRC7, DKK1,

LINGO2, TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

| multicellular

organism development |

9.65×10−3 | 10 | LRRC7, DKK1,

SLITRK3, WDR69, BVES, C8orf85, LINGO2, MEGF10, TPBG,

SLITRK5 |

| regulation of

cellular component biogenesis |

9.92×10−3 | 5 | DKK1, LINGO2,

TPBG, SLITRK5, SLITRK3 |

|

| B, Downregulated

genes |

|

| Terms | Corrected

P-value | Count | Genes |

|

|

single-multicellular organism process |

4.11×10−5 | 23 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, SCNN1G, CPNE5, ARX, CACNA2D2, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4,

SPTB, HOXC5, RD3, FGF9, PDZD7, PROK1, IL33, WNT6, CYP17A1, BMP6,

LGI1, COLEC11 |

| multicellular

organismal process |

5.14×10−5 | 25 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, SCNN1G, CPNE5, ARX, CACNA2D2, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4,

TAS1R3, SPTB, HOXC5, RD3, FGF9, PDZD7, PROK1, IL33, WNT6, ACCN3,

CYP17A1, BMP6, LGI1, COLEC11 |

| eye

development |

5.32×10−5 | 7 | RD3, GJA8, FGF9,

BMP6, AQP5, FOXL2, WNT6 |

| sensory organ

development |

7.88×10−5 | 8 | RD3, GJA8, FGF9,

BMP6, PDZD7, AQP5, FOXL2, WNT6 |

| multicellular

organism development |

1.86×10−4 | 20 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, CPNE5, ARX, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4, SPTB, HOXC5, FGF9,

RD3, PDZD7, PROK1, WNT6, CYP17A1, BMP6, LGI1, COLEC11 |

| anatomical

structure development |

1.87×10−4 | 21 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, CPNE5, ARX, CACNA2D2, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4, SPTB,

HOXC5, FGF9, RD3, PDZD7, PROK1, WNT6, CYP17A1, BMP6, LGI1,

COLEC11 |

| single-organism

developmental process |

5.26×10−4 | 21 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, CPNE5, ARX, CACNA2D2, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4, SPTB,

HOXC5, FGF9, RD3, PDZD7, PROK1, WNT6, CYP17A1, BMP6, LGI1,

COLEC11 |

| system

development |

5.74×10−4 | 18 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, CPNE5, ARX, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4, SPTB, FGF9, RD3,

PDZD7, PROK1, WNT6, CYP17A1, BMP6, LGI1 |

| developmental

process |

6.76×10−4 | 21 | GJA8, TRIM71,

TCF23, FOXL2, CPNE5, ARX, CACNA2D2, SLC32A1, AQP5, CCR4, SPTB,

HOXC5, FGF9, RD3, PDZD7, PROK1, WNT6, CYP17A1, BMP6, LGI1,

COLEC11 |

| positive regulation

of steroid hormone biosynthetic process |

3.83×10−3 | 2 | BMP6,

CYP17A1 |

| positive regulation

of growth |

4.05×10−3 | 5 | CACNA2D2, FGF9,

LGI1, CPNE5, ARX |

| nervous system

development |

4.48×10−3 | 12 | FGF9, PDZD7,

TRIM71, WNT6, CPNE5, CYP17A1, ARX, BMP6, LGI1, SLC32A1, CCR4,

SPTB |

| positive regulation

of organ growth |

7.93×10−3 | 3 | CACNA2D2, FGF9,

ARX |

| camera-type eye

development |

8.92×10−3 | 5 | RD3, GJA8, AQP5,

FOXL2, WNT6 |

| anatomical

structure morphogenesis |

9.15×10−3 | 12 | FGF9, PROK1,

PDZD7, TRIM71, FOXL2, WNT6, CPNE5, ARX, BMP6, LGI1, AQP5,

SPTB |

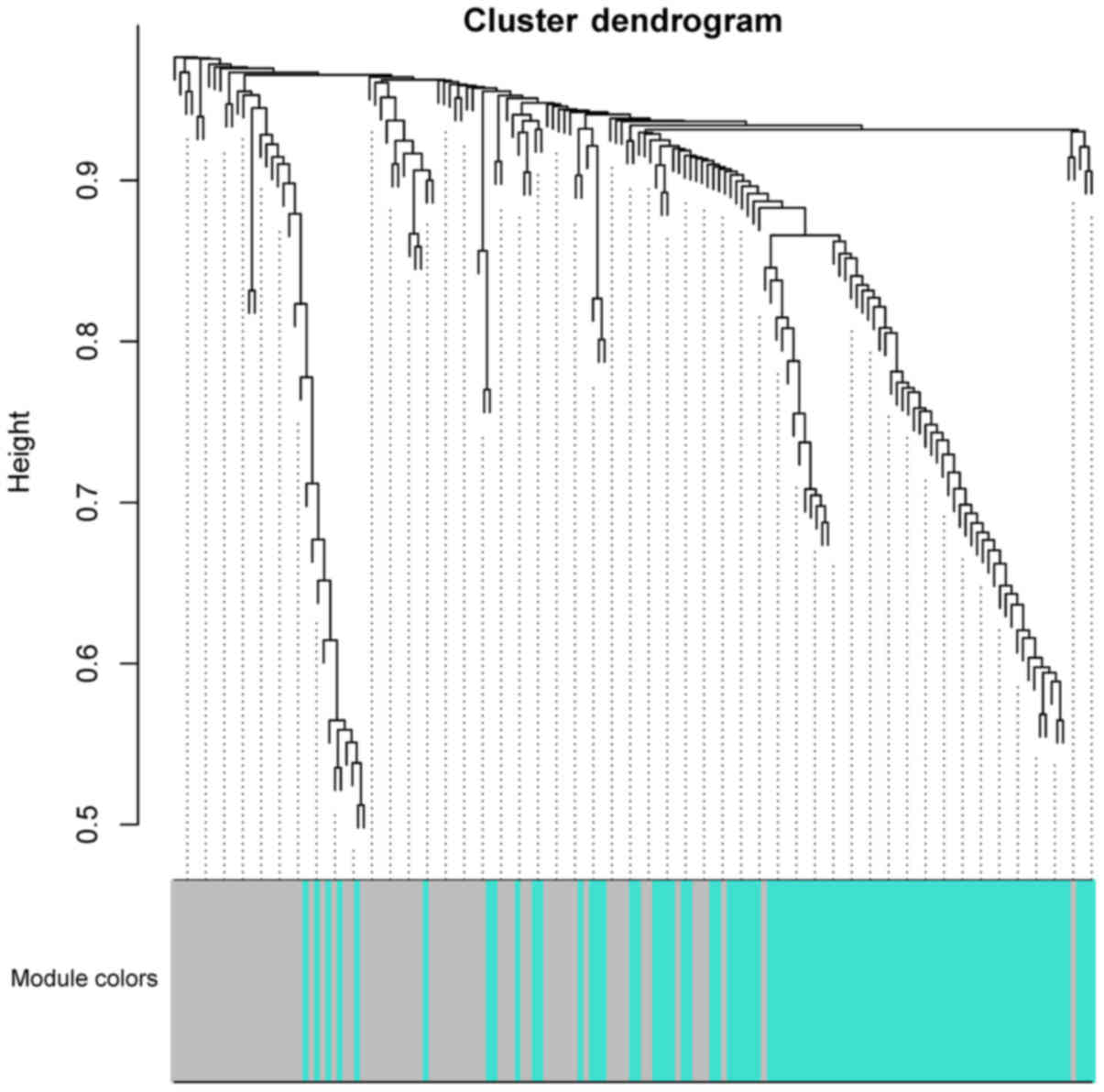

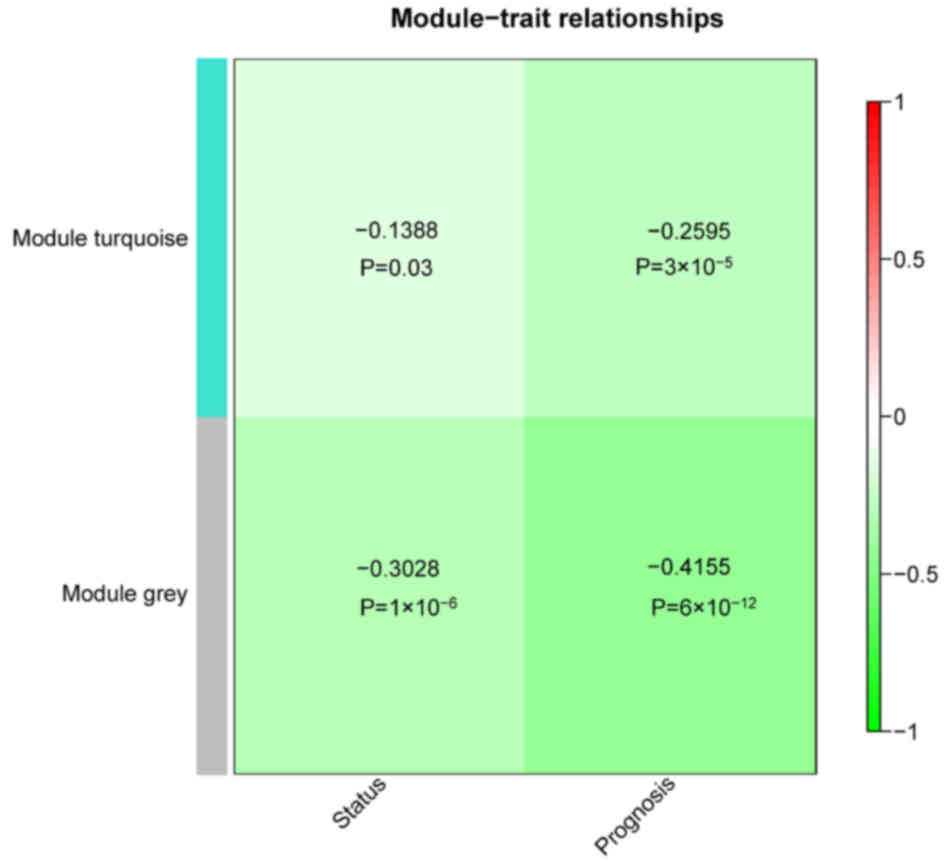

WGCNA

WGCNA was performed and turquoise and grey modules

were identified within the cluster dendrogram (Fig. 2). Within the turquoise module, 87

genes were identified (14 upregulated and 73 downregulated), while

in the grey module, 74 were identified (30 upregulated and 44

downregulated). Correlations between the two modules regarding

status/prognosis were also analyzed. The results demonstrated that

the two modules had significant correlations with status and

prognosis (P<0.05; Fig. 3).

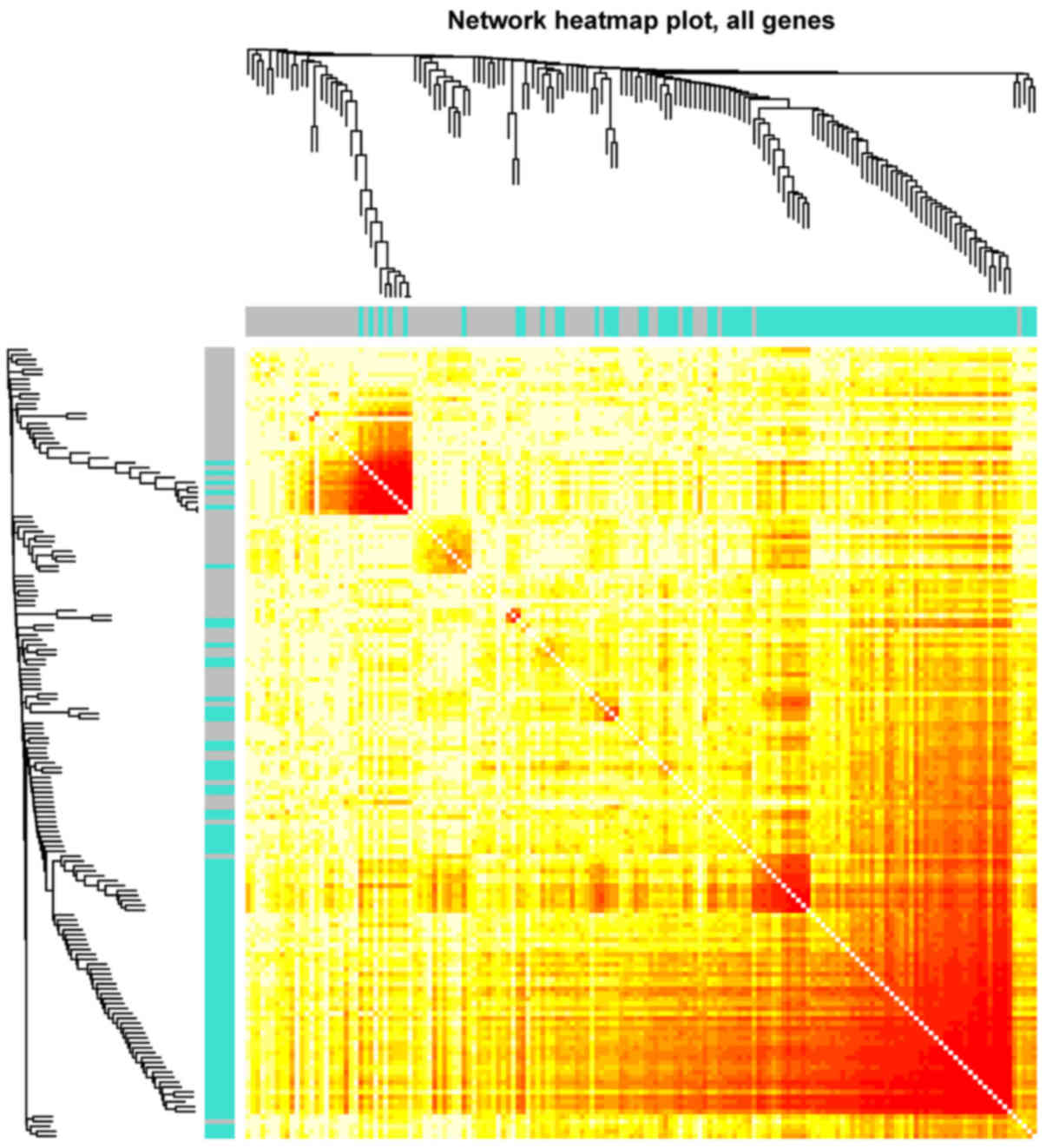

Furthermore, sample correlations were further examined via heatmap

analysis, and it was indicated that the samples in the turquoise

module were more strongly correlated when compared with those in

the grey module (Fig. 4).

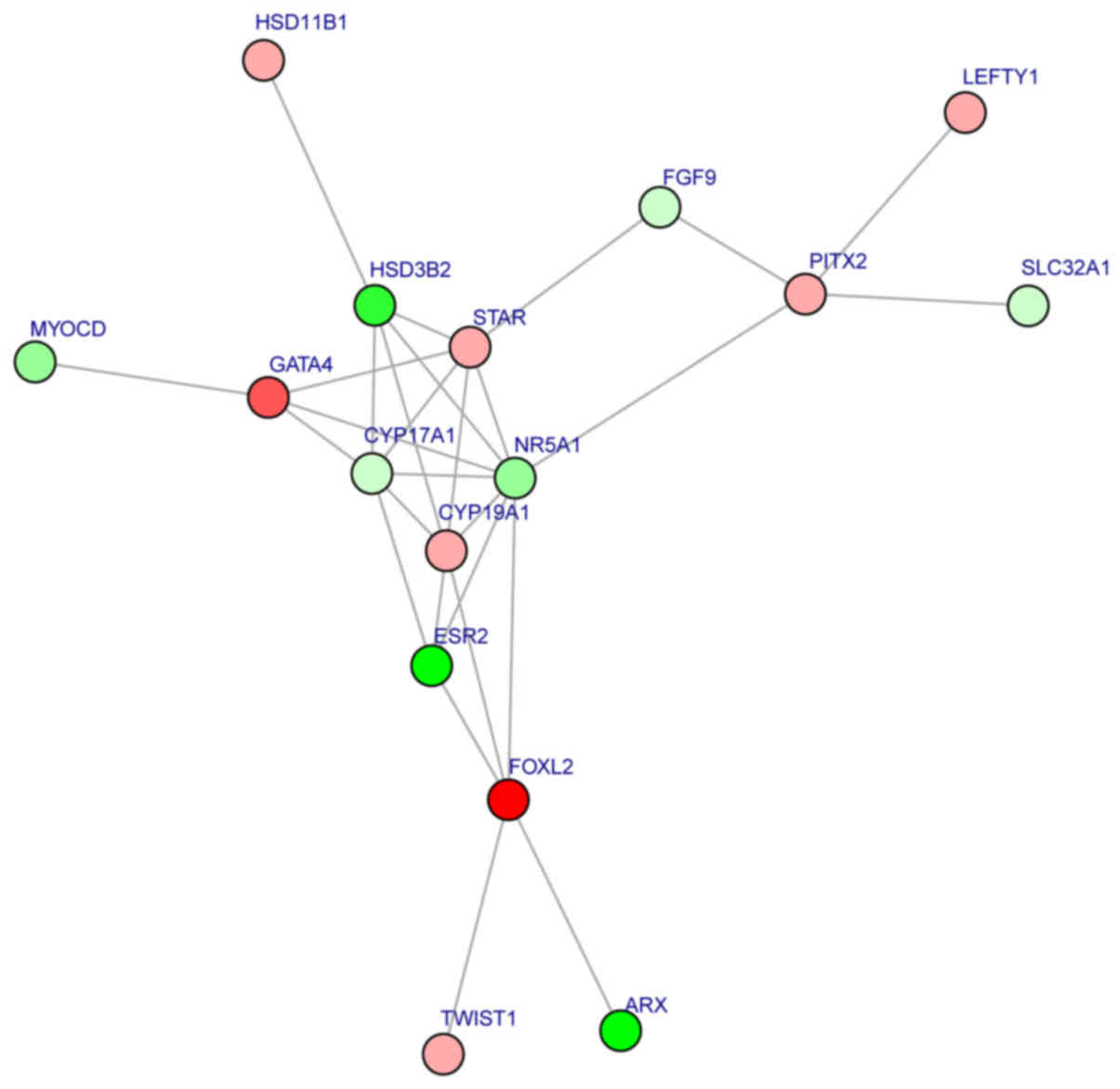

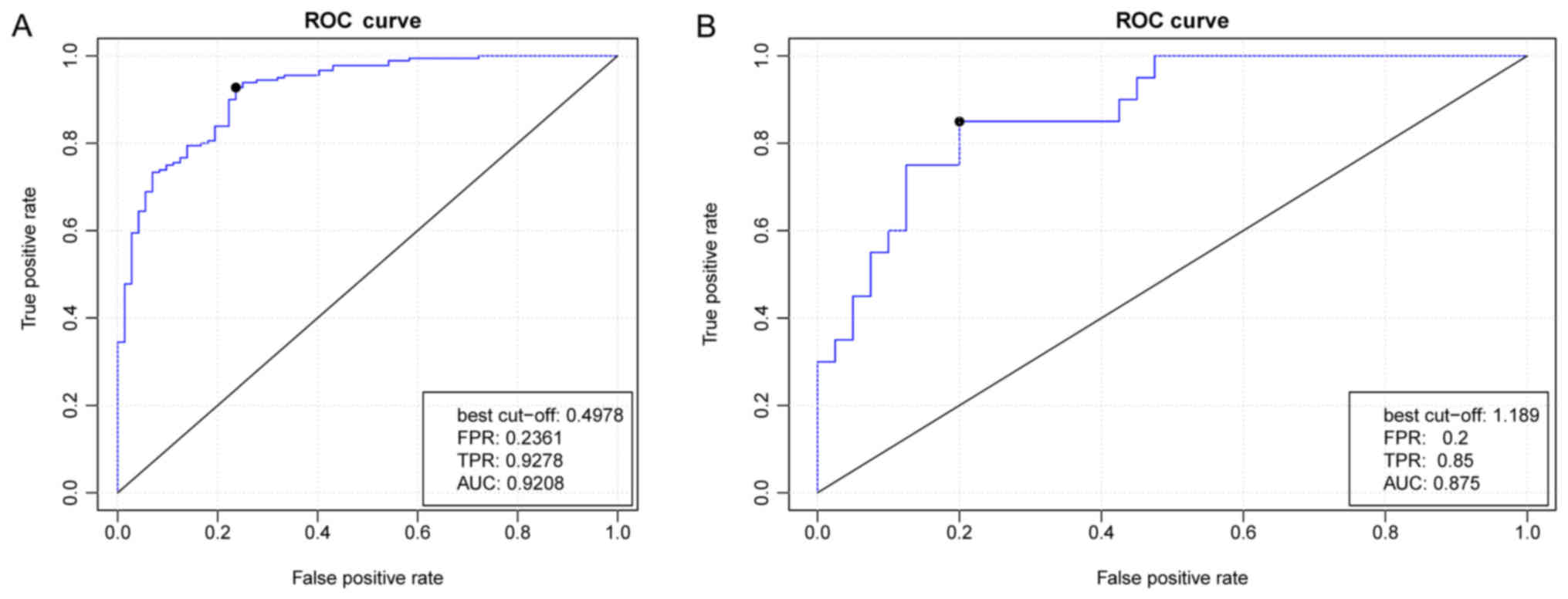

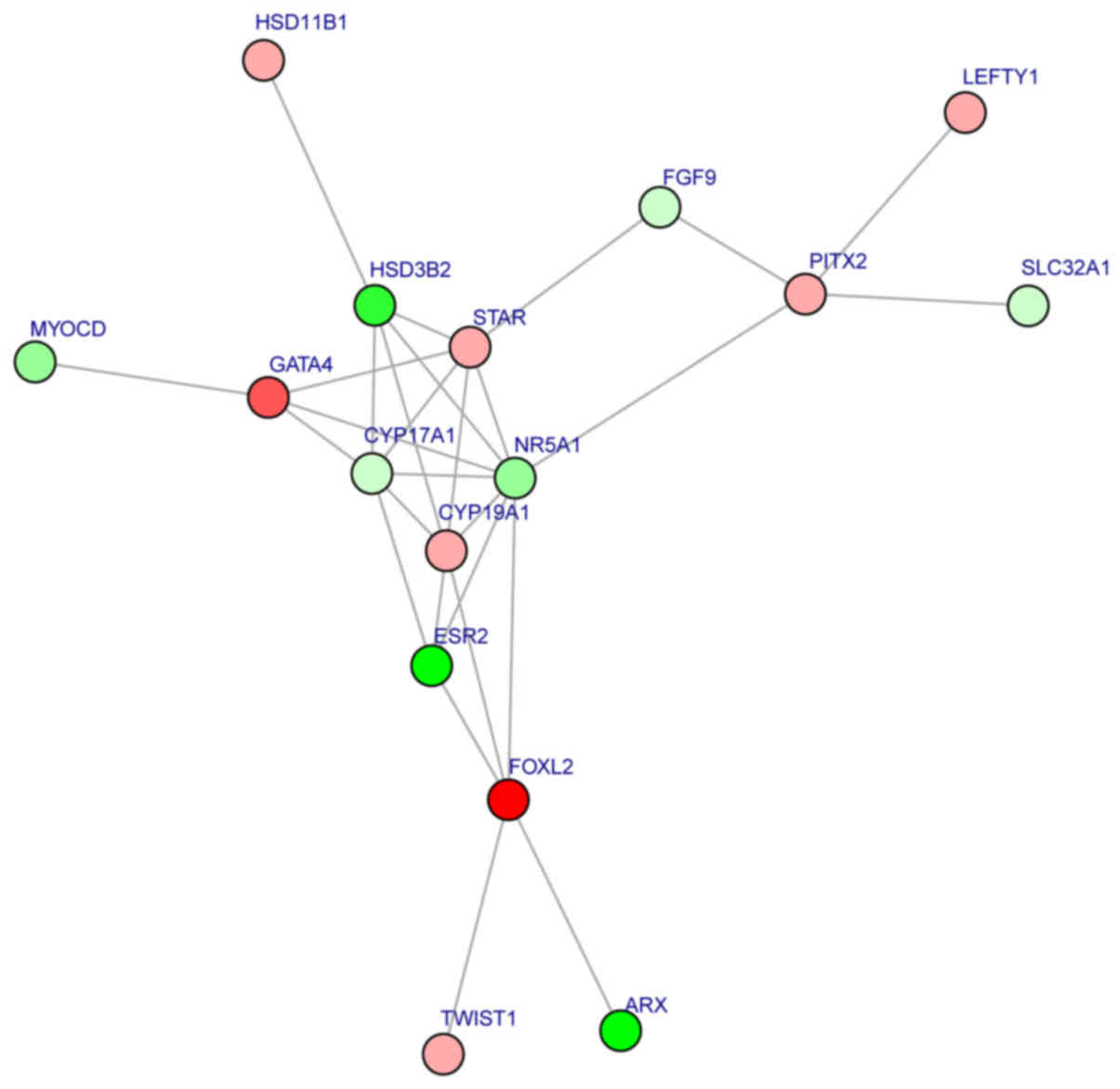

Subnetwork analysis and classifier

construction

Following building of the PPI network, subnetwork

analysis was performed and a significant subnetwork was identified

(Fig. 5). The importance scores

for the 16 subnetwork nodes [transcription factor GATA-4 (GATA4);

fibroblast growth factor 9 (FGF9); aromatase (CYP19A1);

3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/δ5-4-isomerase type 2 (HSD3B2);

corticosteroid 11β-dehydrogenase isozyme 1 (HSD11B1); CYP17A1;

pituitary homeobox 2 (PITX2); left-right determination factor 1

(LEFTY1); homeobox protein ARX (ARX); estrogen receptor β (ESR2);

steroidogenic factor 1 (NR5A1); forkhead box protein L2 (FOXL2);

myocardin (MYOCD); steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

mitochondrial (STAR); vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter

(SLC32A1); and twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1)] are listed in

Table II. There were multiple

interactions among these subnetwork nodes, including HSD3B2-NR5A1,

HSD11B1-HSD3B2, CYP17A1-GATA4, ARX-FOXL2, MYOCD-GATA4, STAR-FGF9

and SLC32A1-PITX2. The subnetwork nodes were taken as feature genes

and a random forest classifier was constructed. The generated ROC

curve demonstrated that the true and false positive rates

separately were 92 and 23% when classifying the recurrent and

non-recurrent OC samples (Fig.

6A).

| Figure 5.Significant subnetwork identified

within the protein-protein interaction network. Upregulated genes

are denoted in red and downregulated in green. GATA4, transcription

factor GATA-4; FGF9, fibroblast growth factor 9; CYP19A1,

aromatase; HSD3B2, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase/δ5-4-isomerase

type 2; HSD11B1, corticosteroid 11β-dehydrogenase isozyme 1;

CYP17A1, cytochrome P450 family 17 subfamily A member 1; PITX2,

pituitary homeobox 2; LEFTY1, left-right determination factor 1;

ARX, homeobox protein ARX; ESR2, estrogen receptor β; NR5A1,

steroidogenic factor 1; FOXL2, forkhead box protein L2; MYOCD,

myocardin; STAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

mitochondrial; SLC32A1, vesicular inhibitory amino acid

transporter; TWIST1, twist-related protein 1. |

| Table II.Importance scores of the subnetwork

nodes. |

Table II.

Importance scores of the subnetwork

nodes.

| Node | Score |

|---|

| ARX | 15.203 |

| CYP17A1 | 10.956 |

| CYP19A1 | 10.902 |

| ESR2 | 10.537 |

| FGF9 | 10.148 |

| FOXL2 | 9.827 |

| GATA4 | 9.786 |

| HSD11B1 | 9.223 |

| HSD3B2 | 9.196 |

| LEFTY1 | 8.259 |

| MYOCD | 7.867 |

| NR5A1 | 7.634 |

| SLC32A1 | 6.367 |

| STAR | 6.167 |

| PITX2 | 5.094 |

| TWIST1 | 4.708 |

Validation using other independent

datasets

The random forest classifier was used to

differentiate between samples in the GSE44104 validation set, and

the prediction accuracies for the non-recurrence and recurrence

groups were 87.5 and 85%, respectively (Fig. 6B). These findings indicated that

the subnetwork nodes were important in predicting OC prognosis.

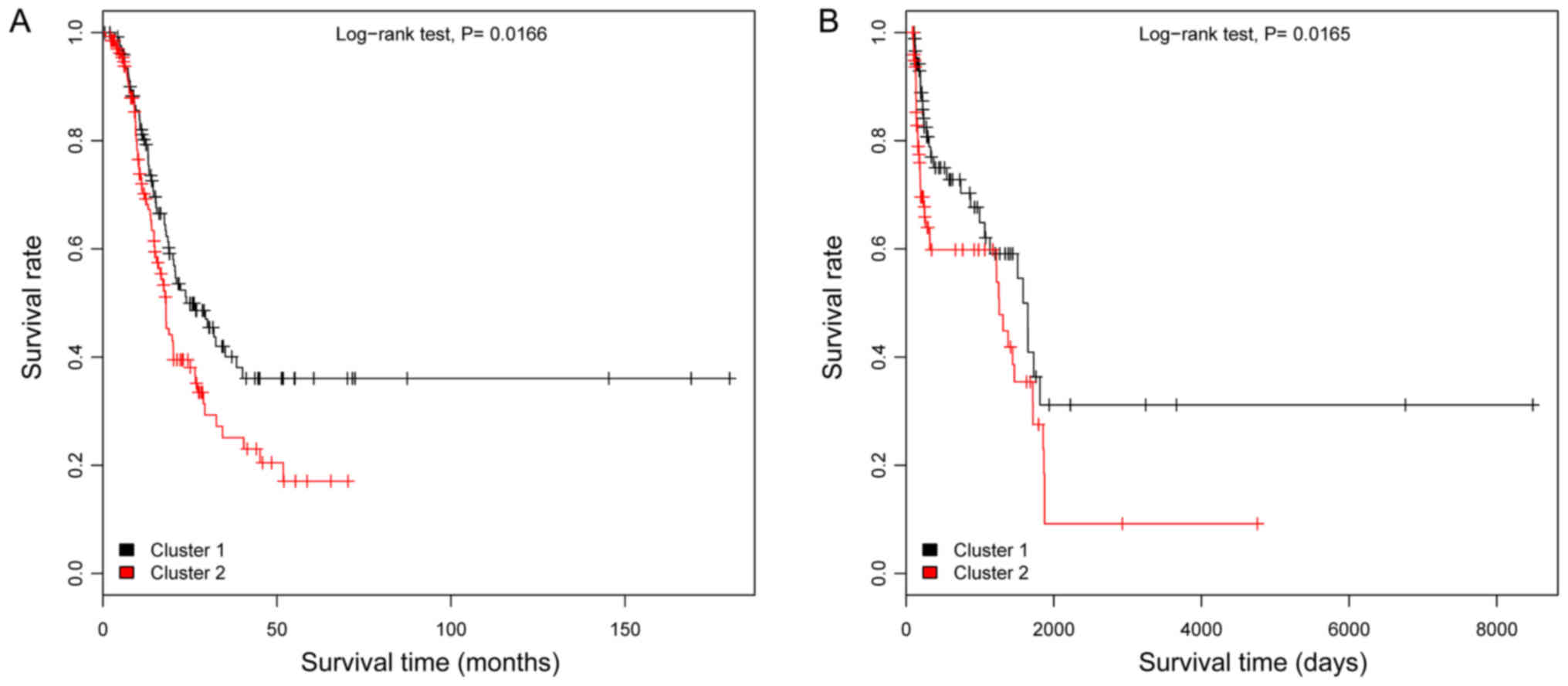

Of the 307 OC samples in the TCGA dataset, only 262

samples remained upon removal of samples without follow-up or

survival time information. These 262 samples were divided into

high- and low-risk groups using the random forest classifier, and

further examined using KM survival analysis. The results

demonstrated that the low risk group had a significantly longer

survival time compared with the high-risk group (P=0.0166; Fig. 7A). Subsequently, the samples from

the second validation set (GSE49997) were divided into high- and

low-risk groups using the random forest classifier. Following

analysis using a KM survival curve, a significant difference was

noted in survival time between the low- and high-risk groups

(P=0.0165; Fig. 7B). These

findings suggested that the random forest classifier had

portability and repeatability.

Discussion

In the present study, 44 upregulated and 117

downregulated genes were identified in the recurrent samples

relative to the non-recurrent samples. When performing WGCNA,

turquoise and grey modules were identified that had significant

correlations with status and prognosis. Furthermore, a significant

subnetwork was identified from the PPI network, with the subnetwork

nodes (including GATA4, FGF9, CYP19A1, HSD3B2, HSD11B1, CYP17A1,

PITX2, LEFTY1, ARX, ESR2, NR5A1, FOXL2, MYOCD, STAR, SLC32A1 and

TWIST1) being utilized as feature genes for constructing a random

forest classifier. Moreover, the classification efficiency of the

random forest classifier was validated and confirmed.

Of the identified nodes, previous studies have

reported that GATA4 overexpression, in conjunction with

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, may predict a shorter

disease-free survival time and may be utilized as a prognostic

marker in patients with ovarian granulosa cell tumor to optimize

follow-up management in the early stages (29,30).

In OC, GATA4 and transcription factor GATA-6 expression is

frequently lost, with this feature specifying the histological

subtype prior to tumorigenic transition of the ovarian surface

epithelium (31). The upregulation

of FGF9 has been detected in primary ovarian endometrioid

adenocarcinomas carrying a defective Wnt/β-catenin pathway and

serves an important role in promoting the cancer phenotype

(32,33). The aromatase enzyme encoded by the

CYP19A1 gene acts in the conversion of androgen to estrogen,

with CYP19A1 variants potentially able to influence OC

susceptibility (34). Thus, GATA4,

FGF9 and CYP19A1 appear to be implicated in the

mechanisms of OC pathogenesis. Enrichment analysis demonstrated

that CYP17A1, which is involved in ‘positive regulation of

steroid hormone biosynthetic processes’, was downregulated. A

previous study demonstrated that steroid hormones serve a role in

OC pathogenesis, and their receptors influence OC patient survival

(35). Therefore, CYP17A1

may affect OC patient prognoses through the positive regulation of

steroid hormones.

The overexpression of PITX2 has been

implicated in OC progression by facilitating cell growth, migration

and invasion, and thus may potentially serve as a therapeutic

target for patients with high-grade OC (36,37).

PITX2 has also been demonstrated to promote OC cell

proliferation through the Wnt pathway, which is closely associated

with ovarian development and OC (38). In ovarian clear cell carcinoma, the

overexpression of LEFTY, a transforming growth factor-β

superfamily member, exhibits an anti-tumor effect by affecting cell

proliferation and cellular susceptibility to apoptotic signals

(39). Estrogen receptor β, which

is encoded by the ESR2 gene, has been suggested to serve as

a critical factor during OC carcinogenesis (40). Furthermore, within the ESR2

promoter region, the genotypic and allelic frequencies of the

single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs3020449 have been

demonstrated to exhibit significant differences based on OC stage,

thus indicating that SNP rs3020449 may be associated with OC

progression (41). These findings

suggest that PITX2, LEFTY1 and ESR2 may also serve

roles in OC pathogenesis.

NR5A1 serves an important role in ovarian

function and development, with an NR5A1 mutation reported to

induce 46 XY disorders of sex development (42). FOXL2 is critical for GC

(granulosa cell) differentiation during the process of

folliculogenesis, with its downregulation potentially serving as an

ovarian granulosa cells tumor prognostic factor (43). TWIST1, which may induce

epithelial-mesenchymal transition and contribute to tumor

metastasis, has been demonstrated to be associated with poor

survival in patients with cancer (44,45).

Thus, NR5A1, FOXL2 and TWIST1 may be associated with

patient survival in OC. Moreover, the multiple interactions within

the PPI subnetwork (including HSD3B2-NR5A1, HSD11B1-HSD3B2,

CYP17A1-GATA4, ARX-FOXL2, MYOCD-GATA4, STAR-FGF9 and SLC32A1-PITX2)

indicate that HSD3B2, HSD11B1, CYP17A1, ARX, MYOCD, STAR and

SLC32A1 may also function in OC by interacting with other

genes.

However, the present study has several limitations

to note. First, the datasets used in the present study had sample

size differences, platform differences and data heterogeneities

that may affect the prediction accuracy of the random forest

classifier. Second, the smaller patient numbers and analytical

methods may limit the predictive capability of the present model.

Finally, only bioinformatics analyses were conducted in the present

study, and no direct experimental validation was performed.

Therefore, further analyses are required to validate the obtained

results.

In conclusion, 44 upregulated and 117 downregulated

genes associated with OC recurrence were identified. Furthermore,

the 16 subnetwork node genes that were identified may be critical

molecules associated with OC recurrence.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the

Hubei Province's Outstanding Medical Academic Leader Program and

the Hubei Province Health and Family Planning Scientific Research

Project (grant no. WJ2015MA024) and the Natural Science Foundation

of Hubei Province (grant no. 2017CFB335).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current

study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

LC and LL performed data analyses and wrote the

manuscript. LW, XL and HX contributed significantly in data

analyses and manuscript revision. JZ conceived and designed the

study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jayson GC, Kohn EC, Kitchener HC and

Ledermann JA: Ovarian cancer. Lancet. 384:1376–1388. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ebell MH, Culp MB and Radke TJ: A

systematic review of symptoms for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer.

Am J Prev Med. 50:384–394. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

McGuire S: World Cancer Report 2014.

Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, International

Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, 2015. Adv Nutr.

7:418–419. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Lengyel E: ovarian cancer development and

metastasis. Am J Pathol. 177:1053–1064. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Cree IA: Cancer biology. Methods Mol Biol.

731:1–11. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Holschneider CH and Berek JS: Ovarian

cancer: Epidemiology, biology, and prognostic factors. Semin Surg

Oncol. 19:3–10. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Tworoger SS and Doherty JA: Epidemiologic

paradigms for progress in ovarian cancer research. Cancer Causes

Control. 28:361–364. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Siu MK, Chan HY, Kong DS, Wong ES, Wong

OG, Ngan HY, Tam KF, Zhang H, Li Z, Chan QK, et al: p21-activated

kinase 4 regulates ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration,

and invasion and contributes to poor prognosis in patients. Proc

Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:18622–18627. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Nakayama N, Nakayama K, Shamima Y,

Ishikawa M, Katagiri A, Iida K and Miyazaki K: Gene amplification

CCNE1 is related to poor survival and potential therapeutic target

in ovarian cancer. Cancer. 116:2621–2634. 2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Etemadmoghadam D, George J, Cowin PA,

Cullinane C and Kansara M: Australian Ovarian Cancer Study Group,

Gorringe KL, Smyth GK and Bowtell DD: Amplicon-dependent CCNE1

expression is critical for clonogenic survival after cisplatin

treatment and is correlated with 20q11 gain in ovarian cancer. PLoS

One. 5:e154982010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Ehlén Å, Brennan DJ, Nodin B, O'Connor DP,

Eberhard J, Alvarado-Kristensson M, Jeffrey IB, Manjer J,

Brändstedt J, Uhlén M, et al: Expression of the RNA-binding protein

RBM3 is associated with a favourable prognosis and cisplatin

sensitivity in epithelial ovarian cancer. J Transl Med. 8:782010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Xia Y, Chang T, Wang Y, Liu Y, Li W, Li M

and Fan HY: YAP promotes ovarian cancer cell tumorigenesis and is

indicative of a poor prognosis for ovarian cancer patients. PLoS

One. 9:e917702014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zhang X, George J, Deb S, Degoutin JL,

Takano EA and Fox SB: AOCS Study group, Bowtell DD and Harvey KF:

The Hippo pathway transcriptional co-activator, YAP, is an ovarian

cancer oncogene. Oncogene. 30:2810–2822. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang J, Guo X, Chang DY, Rosen DG,

Mercado-Uribe I and Liu J: CD133 expression associated with poor

prognosis in ovarian cancer. Mod Pathol. 25:456–464. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Servant N, Roméjon J, Gestraud P, La Rosa

P, Lucotte G, Lair S, Bernard V, Zeitouni B, Coffin F,

Jules-Clément G, et al: Bioinformatics for precision medicine in

oncology: Principles and application to the SHIVA clinical trial.

Front Genet. 5:1522014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Altshuler D, Daly MJ and Lander ES:

Genetic mapping in human disease. Science. 322:881–888. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Chen JM, Cooper DN, Chuzhanova N, Férec C

and Patrinos GP: Gene conversion: Mechanisms, evolution and human

disease. Nat Rev Genet. 8:762–775. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Segundo ES, Tsanas A and Gómez-Vilda P:

Euclidean distances as measures of speaker dissimilarity including

identical twin pairs: A forensic investigation using source and

filter voice characteristics. Forensic Sci Int. 270:25–38. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Yang YH, Xiao Y and Segal MR: Identifying

differentially expressed genes from microarray experiments via

statistic synthesis. Bioinformatics. 21:1084–1093. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Tweedie S, Ashburner M, Falls K, Leyland

P, McQuilton P, Marygold S, Millburn G, Osumi-Sutherland D,

Schroeder A, Seal R, et al: FlyBase: Enhancing Drosophila gene

ontology annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 37:(Database issue).

D555–D559. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Lässer C, O'Neil SE, Shelke GV, Sihlbom C,

Hansson SF, Gho YS, Lundbäck B and Lötvall J: Exosomes in the nose

induce immune cell trafficking and harbour an altered protein cargo

in chronic airway inflammation. J Transl Med. 14:1812016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Iancu OD, Colville A, Oberbeck D,

Darakjian P, Mcweeney SK and Hitzemann R: Cosplicing network

analysis of mammalian brain RNA-Seq data utilizing WGCNA and Mantel

correlations. Front Genet. 6:1742015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

RC Team: R: A language and environment for

statistical computingR Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Vienna, Austria: 2016

|

|

24

|

Beisser D, Klau GW, Dandekar T, Müller T

and Dittrich MT: BioNet: An R-Package for the functional analysis

of biological networks. Bioinformatics. 26:1129–1130. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ma X, Guo J and Sun X: DNABP:

Identification of DNA-binding proteins based on feature selection

using a random forest and predicting binding residues. PLoS One.

11:e01673452016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mikshowsky A, Weigel KA and Gianola D:

0294 Assessing genomic prediction accuracy for Holstein sires using

bootstrap aggregation sampling and leave-one-out cross validation.

J Anim Sci. 94:139–140. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Thomas M: ROC curve comparison of ICNARC

and POSSUM in a UK critical care unit. Br J Anaesth. 117:6672016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

May WL: Kaplan-Meier survival

analysisEncyclopedia of Cancer. Schwab M: Springer; Berlin: pp.

1934–1937. 2011, View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Färkkilä A, Andersson N, Bützow R, Leminen

A, Heikinheimo M, Anttonen M and Unkila-Kallio L: HER2 and GATA4

are new prognostic factors for early-stage ovarian granulosa cell

tumor-a long-term follow-up study. Cancer Med. 3:526–536. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Anttonen M, Pihlajoki M, Andersson N,

Georges A, L'hôte D, Vattulainen S, Färkkilä A1, Unkila-Kallio L,

Veitia RA and Heikinheimo M: FOXL2, GATA4, and SMAD3 co-operatively

modulate gene expression, cell viability and apoptosis in ovarian

granulosa cell tumor cells. PLoS One. 9:e855452014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Cai KQ, Caslini C, Capo-Chichi CD, Slater

C, Smith ER, Wu H, Klein-Szanto AJ, Godwin AK and Xu XX: Loss of

GATA4 and GATA6 expression specifies ovarian cancer histological

subtypes and precedes neoplastic transformation of ovarian surface

epithelia. PLoS One. 4:e64542009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hendrix ND, Wu R, Kuick R, Schwartz DR,

Fearon ER and Cho KR: Fibroblast growth factor 9 has oncogenic

activity and is a downstream target of Wnt signaling in ovarian

endometrioid adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res. 66:1354–1362. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Drummond AE, Tellbach M, Dyson M and

Findlay JK: Fibroblast growth factor-9, a local regulator of

ovarian function. Endocrinology. 148:3711–3721. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Goodman MT, Lurie G, Thompson PJ, Mcduffie

KE and Carney ME: Association of two common single-nucleotide

polymorphisms in the CYP19A1 locus and ovarian cancer risk. Endocr

Relat Cancer. 15:1055–1060. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jönsson JM, Arildsen NS, Malander S,

Måsbäck A, Hartman L, Nilbert M and Hedenfalk I: Sex steroid

hormone receptor expression affects ovarian cancer survival. Transl

Oncol. 8:424–433. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Fung FK, Chan DW, Liu VW, Leung TH, Cheung

AN and Ngan HY: Increased expression of PITX2 transcription factor

contributes to ovarian cancer progression. PLoS One. 7:e370762012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Basu M, Bhattacharya R, Ray U,

Mukhopadhyay S, Chatterjee U and Roy SS: Invasion of ovarian cancer

cells is induced byPITX2-mediated activation of TGF-β and

Activin-A. Mol Cancer. 14:1622015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Basu M and Roy SS: Wnt/β-catenin pathway

is regulated by PITX2 homeodomain protein and thus contributes to

the proliferation of human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell, SKOV-3. J

Biol Chem. 288:4355–4367. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Akiya M, Yamazaki M, Matsumoto T,

Kawashima Y, Oguri Y, Kajita S, Kijima D, Chiba R, Yokoi A,

Takahashi H, et al: Identification of LEFTY as a molecular marker

for ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 8:63646–63664. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Pearce Leigh C, Near AM, Butler JL, Van

Den Berg D, Bretsky P, Conti DV, Stram DO, Pike MC, Hirschhorn JN

and Wu AH: Comprehensive evaluation of ESR2 variation and ovarian

cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 17:393–396. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Schüler S, Lattrich C, Skrzypczak M, Fehm

T, Ortmann O and Treeck O: Polymorphisms in the promoter region of

ESR2 gene and susceptibility to ovarian cancer. Gene. 546:283–287.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Lourenço D, Brauner R, Lin L, De Perdigo

A, Weryha G, Muresan M, Boudjenah R, Guerra-Junior G, Maciel-Guerra

AT, Achermann JC, et al: Mutations in NR5A1 Associated with Ovarian

Insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 360:1200–1210. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Kalfa N, Philibert P, Patte C, Ecochard A,

Duvillard P, Baldet P, Jaubert F, Fellous M and Sultan C:

Extinction of FOXL2 expression in aggressive ovarian granulosa cell

tumors in children. Fertil Steril. 87:896–901. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Wushou A, Hou J, Zhao YJ and Shao ZM:

Twist-1 up-regulation in carcinoma correlates to poor survival. Int

J Mol Sci. 15:21621–21630. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Yin G, Alvero AB, Craveiro V, Holmberg JC,

Fu HH, Montagna MK, Yang Y, Chefetz-Menaker I, Nuti S, Rossi M, et

al: Constitutive proteasomal degradation of TWIST-1 in

epithelial-ovarian cancer stem cells impacts differentiation and

metastatic potential. Oncogene. 32:39–49. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|