Introduction

Estrogens are hormones involved in a number of

physiological functions both pre- and postnatally, including brain

development, growth, reproduction and metabolism. The primary

members of the estrogen family include estrone (E1), estriol and

17β-estradiol (17β-E2), which are primarily produced through the

aromatization of testosterone in the granulosa cells in the ovaries

and peripheral tissues such as the placenta, adipose tissue,

osteoblasts, brain and smooth muscle cells (1,2).

Steroidogenesis begins in the ovarian theca cells where cholesterol

is converted to androgens, and is completed by the ovarian

granulosa cells through the conversion of these androgens to

estrogens. Estrogen synthesis begins with the conversion of

cholesterol into pregnenolone by the P450 side chain cleavage

enzyme. Pregnenolone is then converted into progesterone by

3-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), or into

17-hydroxypregnenolone by 17-α-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase (CYP17).

Progesterone is then converted into 17-hydroxyprogesterone by the

CYP17 enzyme, whereas 17-hydroxypregnenolone is converted into

17-hydroxyprogesterone by 3β-HSD. Next, CYP17 converts

17-hydroxypregnenolone and 17-hydroxyprogesterone into

dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, respectively

(1,2). Next, different 17β-HSD enzymes

catalyze the synthesis of androstenediol from DHEA and testosterone

from androstenedione. Finally, in the granulosa cells of the

ovaries, the enzyme aromatase converts androstenedione and

testosterone into E1 and E2, respectively (1,2).

Another enzyme, 5α-reductase, converts testosterone into the potent

androgen 5α-dihydrotestosterone. In men, estrogens are primarily

produced in the peripheral tissues and, to a lesser extent in the

testes by the aromatization of testosterone (1,2). The

primary biologically active estrogen is 17β-E2, which demonstrates

a high affinity for estrogen nuclear receptors and regulates vital

physiological processes both pre- and postnatally. Estrone is a

less active estrogen given its low affinity to estrogen receptors

(ERs) and predominates in peri- and post-menopausal women. Estriol

is primarily secreted by the placenta during pregnancy and has a

weak affinity to ERs (1).

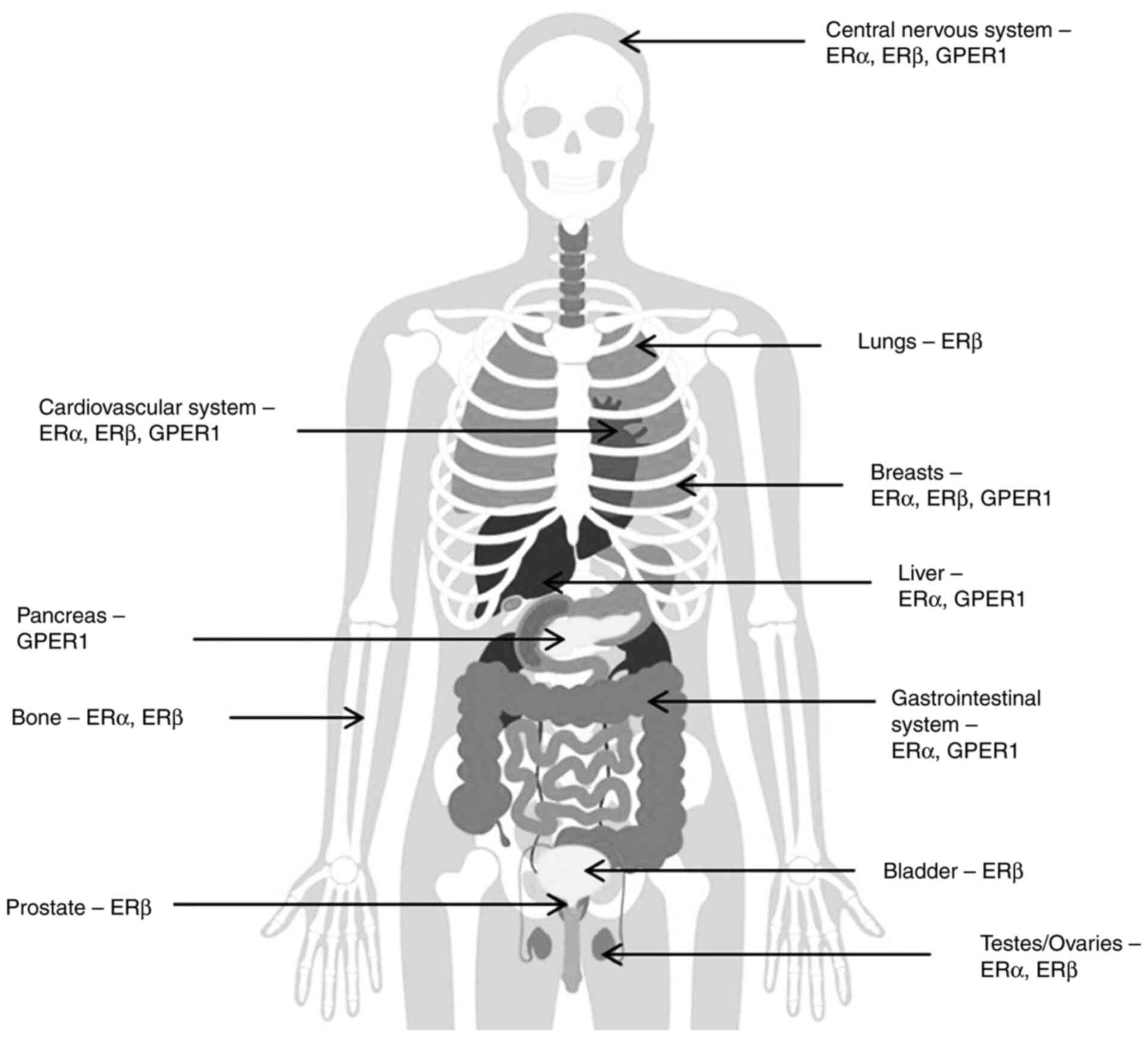

ERα, ERβ and G-protein coupled ER1 (GPER1) are the

primary ERs and are expressed in numerous target tissues. ERα is

primarily present in breast tissues, bones, the uterus, thecal

ovarian cells, testes, epididymis, the prostate and the liver. ERβ

is expressed in the bladder, granulosa ovarian cells, prostate

epithelium, the colon and immune system cells. In adipose tissue

and to a greater extent, in the brain and cardiovascular tissues,

both ERα and ERβ are expressed (3,4)

(Fig. 1). Expression of GPER1 has

been detected in multiple tissues, including in the endometrium,

breast, ovaries, brain, adrenal glands, kidneys, vasculature and

heart endothelium (5). More recent

studies on mice and in vitro have reported the homeostatic

role of GPER1 in physiological actions such as energy homeostasis,

cardiovascular function, bone and cartilage development, immune

system response and neurodevelopment and neurotransmission

(6). Any defects in ER signaling

lead to a number of diseases, including those affecting growth and

puberty, fertility and reproduction abnormalities, cancer,

metabolic diseases, osteoporosis and neurodegeneration (4).

Estrogens and ERs exert their effects via genomic

and non-genomic processes. Estrogens bind to ERs to cause ER

dimerization and translocation to the nucleus, where they function

with specific auxiliary elements known as estrogen response

elements (EREs) located in the promoter regions of target genes.

Alternatively, ERs also act via kinases and other molecular

interactions leading to gene expression and functions through a

non-genomic mechanism (7–10). The actions of ERα and ERβ

antagonize each other in specific tissues such as the bones,

breasts and brain, and in prostate cancer cells (8–12).

ERβ has isoforms that can act separately and by different actions

on specific tissues (11). For

instance, the ERβ isoforms ERβ2 and ERβ5 inhibit ERα in breast

cancer cells, exerting a protective role (8,10,12).

Likewise, in breast cancer T47D cells, ERβ expression is

upregulated compared with ERα (10). In addition, in the bone, ERα is

primarily expressed in the cortical bone, whereas ERβ is expressed

mostly in the trabecular bone (11).

ERs: Location, structure and function

Location and structure

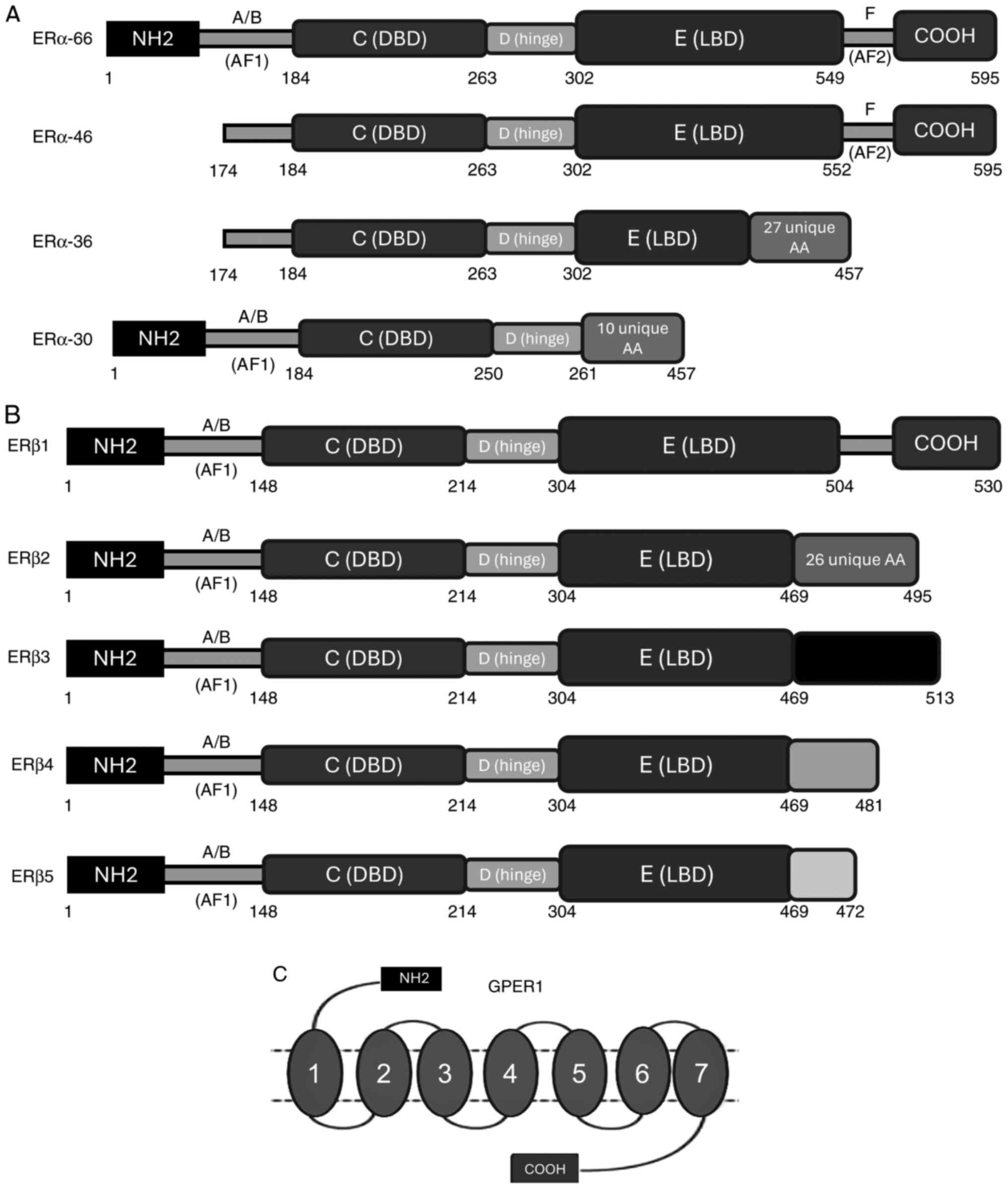

Estrogen nuclear receptors belong to the nuclear

receptor superfamily and thus have similar structural properties to

thyroid and steroid hormone receptors. ERα consists of 595 amino

acids and is encoded by the ESR1 gene located on chromosome

6 (6q25.1) (12). ERβ is 530 amino

acids long and is encoded by the ESR2 gene on chromosome 14

(14q23.2) (13). ER, similar to

all the other members of the nuclear receptor family of proteins is

domain-structured. Specifically, ER consists of six domains: A, B,

C, D, E and F (Fig. 2). The A and

B domains, also referred to as the N-terminal domain, connects and

activates the DNA transactivation function domain [activation

function 1 (AF-1)]. The A and B domains are associated with

receptor specificity and contribute to the transcriptional

activation of target genes; they are also required for

ligand-independent transcriptional regulation (12–15).

Domain C, also known as the DNA-binding domain, is a highly

preserved domain that enhances the DNA-binding ability of ER

(12–15). Two zinc fingers are localized on

the C domain, which interact with specific hormonal response

elements, EREs, leading to receptor dimerization. Domain D is the

hinge region between domains C and E, which binds to heat shock

proteins. Domain D also acts to stabilize the DNA-binding function

of the C domain and provides the receptor with flexibility in

binding to EREs (14,15). Finally, the E and F domains are the

ligand-binding domains (LBD), which are located at the C-terminus.

The E and F domains exhibit a complex monitoring ligand-dependent

action through the transcriptional activation function domain

(AF-2) and coactivators in Helix 12. Helix 12 serves a key role in

the LBD, modifying its structure when bound to a ligand; this

results in the active form when ER is bound to an agonist, or the

inactive form when bound to an antagonist, and this structural

change modulates the transcriptional regulation (14,15).

Finally, GPER1, previously known as GPR30, consists of 375 amino

acids and is located on chromosome 7 (7p22.3). GPER1 consists of

seven transmembrane α-helices, which form four extracellular

segments and four cytosolic segments. The binding affinity of GPER1

to estrogen is weaker than that of the nuclear ERs. GPER1 was

discovered 20 years ago and the details of its exact interactions

with estrogens and other steroid hormones remain to be determined

(16).

Different isoforms of ERα arise due to gene splicing

(Fig. 2). ERα isoforms include

ERα-46 and ERα-36, which are the primary reactive estrogen isoforms

(17) ERα-36 is formed due to the

presence of an alternative transcription site at the first intron

and lacks AF1 and AF2 domains. ERα-36 contains exons 2–6 of the

wild-type EΡα and exon 9 (27 amino acids at the C-terminal)

(18,19). ERα-46 is another ERα variant

lacking exon 1; it contains all exons of the wild-type receptor

(18). Numerous variants of ERβ

have also been identified, including ERβ2, ERβ4 and ERβ5, which

lack a different C-terminal sequence in order to bind to different

EREs (20,21).

ERβ1 consists of 530 amino acids and is the

full-length version of wild-type ERβ, whereas ERβ2, 3, 4 and 5 have

a single LBD sequence. These differences result in a shorter LBD

and a lack of AF2 domain function. ERβ1 is the only isoform that

can bind to an estrogen-ligand, the remaining truncated ERβ

isoforms have no estrogen-binding ability (20).

Function

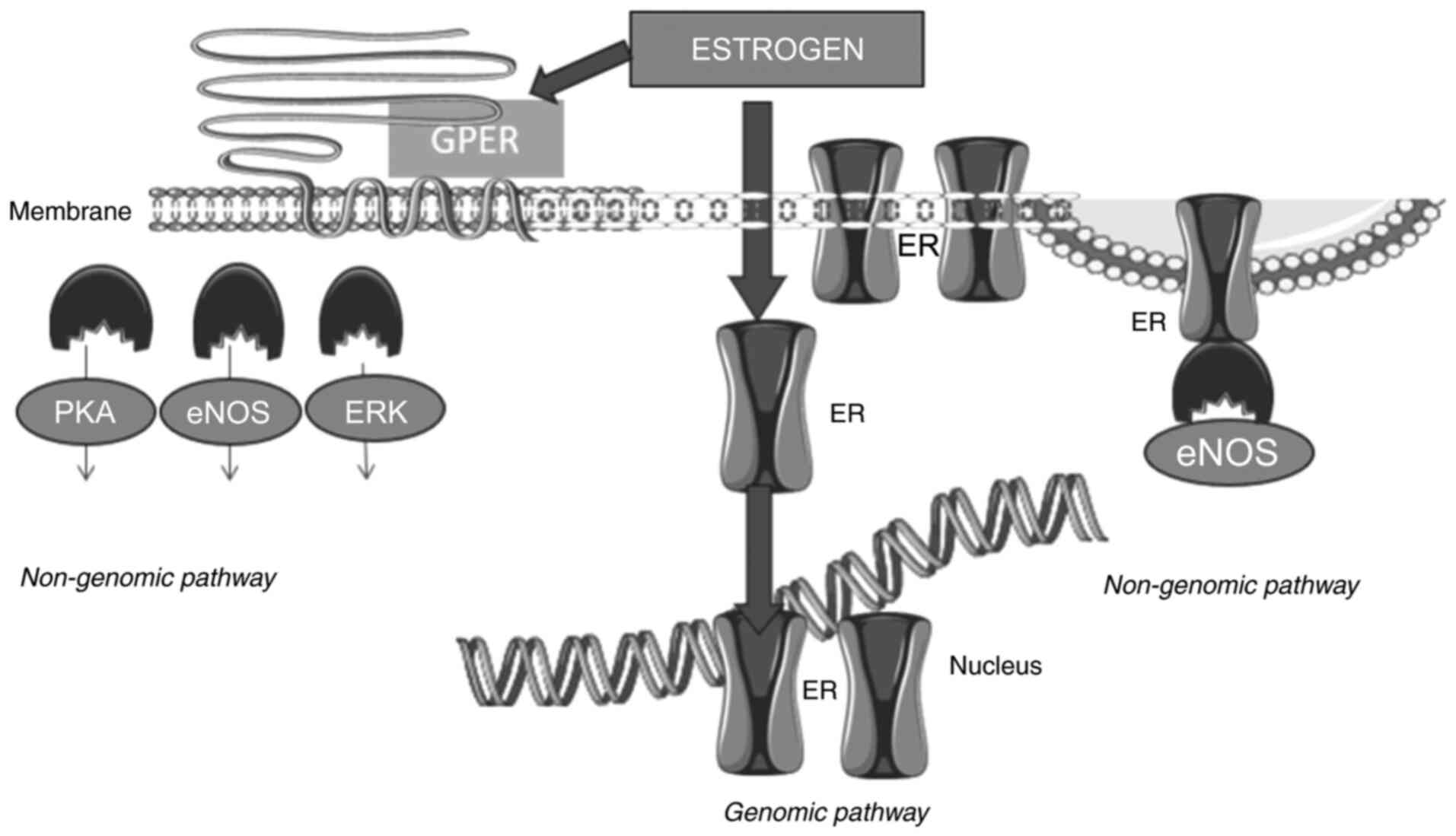

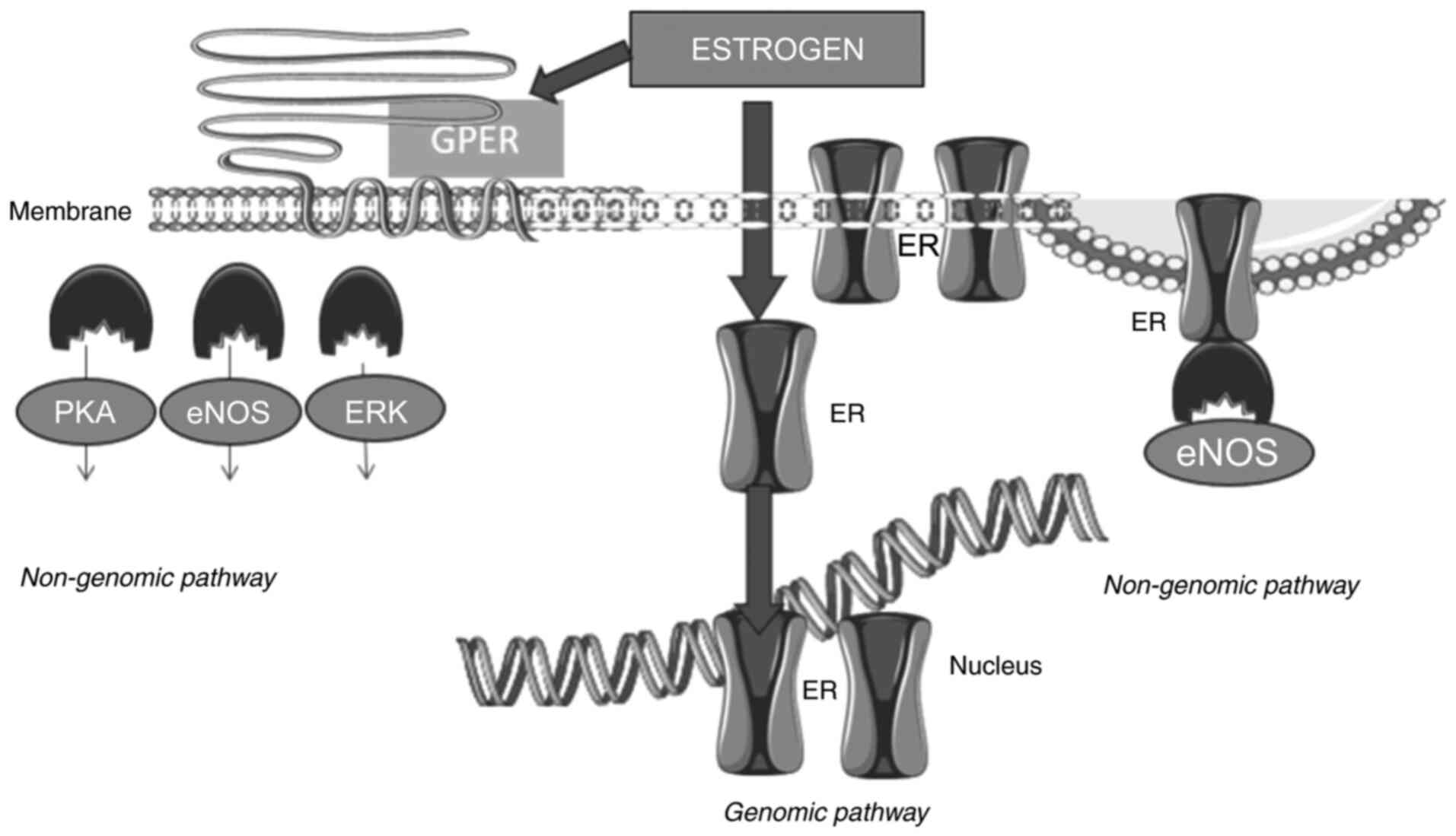

Estrogens exert their effects upon binding to their

receptors via complex genomic and non-genomic mechanisms (Fig. 3) (22). The mechanisms of ER expression and

action are complex. Both ERα and ERβ are activated via AF-1 and

AF-2 domains, which are located in the N-terminal domain and LBD,

respectively, and mediate synergistic transcriptional regulation

(14,23). The genomic action of ERs regulates

the transcription of numerous target genes involved in the growth

and differentiation of the cell. When estrogen hormones bind to

ERα, the receptor is activated, dimerizes and translocates to the

nucleus where it interacts with transcriptional coactivators. The

activated form of ERα targets the promoters of the target genes

binding to EREs. Moreover, ERα is able to bind to serum-responsive

elements forming a complex, which then interacts with transcription

factors, including activator protein 1 and specific protein 1, to

modulate the expression of genes lacking EREs in their promoter

regions (9,10,15,24).

| Figure 3.Estrogen receptor signaling pathway.

By the genomic mechanism, ER after ligand binding and dimerization,

translocates to the nucleus, where it directly binds to the

responsive elements of target genes involved in cell growth,

inflammation, proliferation, survival and protein synthesis. By the

non-genomic mechanism, estrogens bind to ERs modulating eNOS

activity. Estrogens also bind to the GPER located on the membrane

to regulate signaling through eNOS, PKA and extracellular

signal-regulated kinases ERK or MAPK. ER, estrogen receptor; eNOS,

endothelial nitric oxide synthase; GPER, G-protein coupled ER; PKA,

protein kinase A. |

ERα also exerts non-genomic activity (25,26).

Estrogen binds to membrane ERs and regulates ion channel opening,

or activates related enzymes and Ca2+ mobilization that

triggers the activation of nuclear transcription factors. This

involves the fast activation of intracellular signaling pathways

including the cyclic adenosine monophosphate and the growth factor

receptor PI3K/Akt or Ras/MAPK pathways. The ERα-E2 complex binds

with a number of different proteins leading to the generation of a

complex molecule within the cytoplasm. Such proteins include the

Src protein kinase and the p85 subunit of PI3K. Such complexes can

rapidly trigger the activation of the MAPK and Akt pathways

(27). Furthermore, ERs can also

act via a ligand-independent mechanism through interaction with

growth factors such as insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and

epidermal growth factor. These growth factors trigger the

phosphorylation of the ERs via the growth factor membrane receptor

to regulate intracellular signaling pathways. Through this

mechanism, ERs can regulate gene expression without the need for

ligand binding (22,23).

The non-genomic mechanisms of ERα involving the

plasma membrane are based on post-translational alterations. The

two mechanisms, genomic and non-genomic, are not completely

independent. In fact, there is an interchange between the two

mechanisms of action, particularly via the phosphorylation of ERα

or its cofactors. An example of the overlap between the two types

of mechanisms of ER signaling is the estrogenic activation of

cyclin D1 via the AP-1 binding site, which requires MAPK activity

and formation of an ER/Src/PI3K complex (7,28).

In the present review, ERs' effects in three target

tissues as paradigms of the multiple facets of the ER, including

bone and growth disorders, cancer, gender dysphoria and ageing, are

discussed. The antagonistic action of ERs in the aforementioned

tissues complicates the understanding of their mechanisms of action

(4). The increasing prevalence of

breast cancer, particularly hormone receptor-positive breast

cancer, remains a challenge for the development of novel

anti-hormonal therapies other than tamoxifen and aromatase

inhibitors, to minimize the toxicity of long treatment regimens in

patients with breast cancer. A complete understanding of the

mechanisms of action of ERs in the bones may result in the

identification of novel pathways for the treatment of osteoporosis.

Aging of the brain and related diseases such as dementia and

depression are associated with the lack of estrogens, particularly

in women after menopause. ERs serve a key role in aging. Estrogens

are known to exert a neuroprotective role on the brain via ERs.

Decreases of estrogens with age is followed by brain cell

degeneration and decreased of memory and cognition. Gender

dysphoria, a marked incongruence between experienced gender and

biological sex, is commonly hypothesized to arise from discrepant

cerebral and genital sexual differentiation. The exact role of ERs

in gender dysphoria is a challenge that requires further

research.

In the present review, a comprehensive literature

search was performed using PubMed and the search terms ‘ER’,

‘structure’, ‘function’, ‘bones’, ‘cancer’, ‘breast cancer’,

‘brain’ and ‘gender dysphoria’ along with the appropriate Boolean

modifiers.

ERs in the bones

Estrogens are vital for skeletal growth and for the

maintenance of bone mass in both males and females. Estrogen action

is mediated via ERα and ERβ in both the growth plate and

mineralized bone from early in human development to adulthood

(29). During puberty, estrogens

begin exhibiting their roles in the pubertal growth spurt by

binding to ERs on osteoblasts and chondrocytes. Estrogens promote

osteoblastic activity and inhibit osteoclastic activity via

advancing of the growth plate, bone proliferation and epiphyseal

fusion (29,30). The fact that estrogen deficiency

leads to osteopenia and presumably osteoporosis in postmenopausal

women is well established (29).

Both estrogens and androgens also act directly and/or via the

ERα gene in osteoblasts by altering the physiological

balance of the osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of NF-κB ligand

system (30). Another mechanism

involved in the osteoprotective actions of estrogens is achieved

via the upregulation of the Fas ligand (FasL) gene.

FasL action is mediated by ERα, resulting in increased

apoptosis in differentiated osteoclasts (31). Moreover, androgens also contribute

to skeletal growth and bone mineral density either via a direct

action on the growth plate or indirectly through their

aromatization to estrogens (30).

Estrogen deficiency leads to an increase in

osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis in both humans and rodents.

There are different patterns of expression of ERs on specific bone

cells, including osteoblasts and osteoclasts, and on cartilage

cells known as chondrocytes, and these patterns of expression are

influenced by age and sex. ERα chondrocyte knock-out mice

have been reported to exhibit increased longitudinal bone growth

and wider growth plates (32).

However, ERα deletion from the osteoclast lineage does not

affect the cortical bone mass (33). ERα knock-out mice

demonstrated trabecular bone loss and high bone turnover, which may

be related to increased osteoclast counts in females compared with

males. However, deletion of the ERα gene in osteoblast

progenitors in female mice demonstrated no effect on trabecular

bone mass (11,34,35).

Furthermore, ERβ is also highly expressed in osteoclasts (23). Studies in humans reported similar

findings (11,34,35).

Expression of ERα and ERβ also differs in bone compartments in

humans, where ERβ is expressed in higher levels on the trabecular

bone whereas ERα is primarily expressed in the cortical bone

(11,34,35).

The clinical implications of ER function were first

described approximately four decades ago. The first case of

estrogen resistance in a male patient of tall stature, with

markedly delayed skeletal maturation and osteoporosis, was

described in 1986. This patient was reported to possess a

disruptive mutation in the ERα gene (36) and the administration of estrogen

did not improve the condition of the patient (36). A similar clinical presentation was

observed in male patients with an aromatase deficiency. The

aromatase gene CYP19, is located on chromosome 15q21.1 and

is expressed in a number of tissues, including the placenta,

ovaries, testes, adipose tissues and the brain. Specific promoters

in each tissue type lead to different splice variants and different

expression profiles of the CYP19 gene in the respective

tissues (37). The aromatase

enzyme serves an essential role in sex steroid physiology by

converting C19 androgenic steroids (androstenedione and

testosterone) to C18 estrogens (E2 and E1), which promote growth

acceleration, skeletal maturation and epiphyseal fusion. Aromatase

gene inactivating mutations in males cause delayed bone maturation

and decreased bone mineralization. In contrast with estrogen

resistance, administration of estrogen in patients with aromatase

deficiency, promotes the closure of growth plates (38). Conversely, females with an

aromatase deficiency demonstrate different degrees of virilization,

from an infant with ambiguous genitalia to a woman with polycystic

ovarian syndrome (39).

ERs and cancer

Estrogen nuclear receptors are involved in tumor

development and progression in numerous types of cancer (10). Gynecological, endocrine gland,

gastrointestinal and lung cancer may exhibit either up- or

downregulation of ERs. Both ERα and ERβ are expressed in numerous

types of tumors but usually in different cancer types (40). ERα expression appears to

predominate in breast, ovarian, endometrial and endocrine gland

cancer, whereas ERβ is upregulated in gastrointestinal and lung

cancer (10). Conversely, ERβ

inhibits the proliferation of colon and lung cancer, whereas ERα

exerts an onco-protective role in breast cancer, with decreased ERα

levels associated with a poorer prognosis (40). The polymorphic expression of ERs in

different types of cancer supports the notion that estrogenic

function is tissue-dependent. However, the exact mechanisms of

action in the different types of tissues remain incompletely

understood. The present review focuses on breast cancer, with a

summary of ER expression in other types of cancer provided in

Table I (41–57).

| Table I.ERα, ERβ and GPER actions in cancer

tissues. |

Table I.

ERα, ERβ and GPER actions in cancer

tissues.

|

| Role of

receptors |

|---|

|

|

|

|---|

| Cancer type | ERα | ERβ | GPER |

|---|

| Ovarian | Tumor promoter

(41) | Tumor suppressor

(41); | GPER1 tumor

suppressor (43); |

|

|

| ERβ and ERβ2

suppress ERα (42); | GPER30 tumor

promoter (44) |

|

|

| ERβ5 tumor promoter

(42) |

|

| Prostatic | Tumor promoter

(42) | Tumor suppressor

ERβ5 (45); | Tumor suppressor

(46) |

|

|

| Tumor promoter

(45) |

|

|

Gastric/intestinal | Tumor suppressor

(47); | ERβ5 tumor promoter

(49) | Tumor promoter

(50); |

|

| ERα36 tumor

promoter (48) |

| Tumor suppressor

(50) |

| Liver | Tumor suppressor

(51); | Tumor promoter

(51) | Tumor suppressor

(52) |

|

| Tumor promoter

(51) |

|

|

| Pancreatic | Tumor promoter

(53) | Tumor promoter

(53) | Tumor suppressor

(53) |

| Melanoma | Tumor promoter

(54) | Tumor suppressor

(54) | Tumor suppressor

(54) |

| Lung | Tumor promoter

(55) | Tumor promoter

(56) | Tumor suppressor

(57) |

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women,

accounting for 30% of all new female cancer cases, with a rising

global incidence in both pre- and postmenopausal women (58). Breast tumors are categorized based

on histopathological analysis as either lobular or ductal, in

situ or invasive carcinoma (59). According to the molecular profile,

breast cancer can be classified as positive or negative for ERα,

progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor

receptor 2 (HER2). The latter classification of breast cancers

relies on three primary subtypes as follows: Luminal, which is

ER+PR+HER2−, HER2-positive, which

is ER−PR−HER2+, or

triple-negative, which is

ER−PR−HER2−. The majority of

breast cancer cases (~80%) are ERα-positive. The luminal type is

separated into two subclasses, A and B. Both subclasses express ERα

but vary in terms of aggressiveness. Luminal A cases are typically

low-grade, whereas luminal B can be of higher grade and with worse

prognosis. Luminal B cases demonstrate upregulated expression of

HER2, reduced ERα expression and increased cancer cell

proliferation (60). Knowing the

molecular profile of breast cancer allows for the selection of the

most appropriate treatment, management and follow-up for

patients.

Physiologically, ERα is expressed in the ducts and

lobules of the breast gland, while ERβ is expressed in the luminal,

myoepithelial and stromal cells. ERα serves a major role in breast

development, while ERβ depletion has no effect on mammary gland

growth and development (60). The

etiology of breast cancer is multifactorial. Mutations in tumor

suppressor genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, TP53 or

PTEN, or gain of function mutations in oncogenes such as

EGFR, IGF1R and HER2 only account for a small

percentage of breast cancer cases (58). Given that ERα is found only in 10%

of breast tissue cells, mutations in the ERα gene are not

the primary cause of breast cancer formation. However, ERα

dysregulation is involved in breast cancer development and

progression. ERα is found in ~80% of breast cancer cells (61), which shows the importance of the

role of estrogens in hormone-dependent breast cancer. Numerous

studies have linked the occurrence of breast cancer with exposure

to estrogen replacement therapy in menopausal women, and the

involvement of ERs has been hypothesized (62,63).

The pathophysiological mechanisms of the

carcinogenic effects of estrogen in the breast are still under

evaluation. Estrogens, through ER-dependent and independent

mechanisms, can promote the upregulation or downregulation of

numerous molecules involved in cell proliferation, differentiation

and apoptosis (40). ERα functions

as a transcription factor for several tumor-associated genes,

including IGF1 receptor (IGF1R), cyclin D1, the anti-apoptotic

protein BCL-2 and vascular endothelial growth factor (62–64).

Moreover, estrogens, primarily 17β-E2, can stimulate ERα-mediated

genes such as the LRP16 gene, which interferes with and

downregulates ERα-mediated transcription of E-cadherin (64). The reduction of E-cadherin enhances

the invasiveness of breast cancer (64). Furthermore, estrogens may

upregulate the expression of Wnt11 via an ER-dependent

mechanism in breast cancer (65).

Likewise, studies have reported that phosphorylation of ERα at

serine residues 118 and 167 in breast cancer cells induces

expression of genes that impact tumor progression and treatment

responsiveness (65–67). Conversely, estrogens can promote

cell proliferation via non-ER related cell membrane phosphorylation

of target molecules such as Akt (67). Such knowledge may allow the

development of innovative cancer treatments based on non-ER-related

mechanisms of estrogen action.

ERα is expressed in ~80% of breast cancer cells,

meaning that these breast cancer cases respond to endocrine

therapy. Conversely, patients with ESRα mutant-positive

metastases demonstrate resistance to hormonal therapy. Missense

mutations in ESRα have been identified in >51 residues

most of which are within the ER-LBD. Such mutations are either

hormone-dependent, hormone-independent or neutral. Y537S and D538G

are the most common mutations and are characterized as

hormone-independent mutations (68). Other mutations such as K303R and

E380Q result in estrogen hypersensitivity and are characterized as

hormone-dependent. Finally, neutral mutations such as S432L and

V534E have also been reported (69). ERα splice variants are also

involved in breast cancer. ERα-46 is expressed in ~70% of breast

cancer tissues and inhibits cell proliferation and ERα-66-regulated

target gene transcription. ERα-46 appears to enhance endocrine

responses by inhibiting selected ERa-66 endocrine responses. Via

this mechanism, ERα-46 appears to increase the response to

endocrine therapy (70). ERα-36

regulates non-genomic signaling. It has been reported that patients

with breast cancer with tumors expressing high levels of ERα-36

benefit less from tamoxifen therapy compared with those with low

levels of ERα-36 expression. Thus, ERα-36 is suggested to act as an

antagonist of tamoxifen contributing to hormone therapy resistance

and cancer metastases (71).

Genomic studies of breast cancer have reported the

role of epigenetics in ERα dysregulation. The loss of ERα

expression can be the result of hypermethylation of CpG islands

within the ERα promoter region. Deacetylation and histone

methylation of the ER promoter are also epigenetic events involved

in ERα deregulation. Demethylating agents and methylation

inhibitors may thus serve as potential treatments for ERα-negative

or endocrine therapy-resistant tumors (72).

ERβ is expressed in breast cancer cells, but to a

lesser degree than ERα. There are conflicting studies regarding the

role of ERβ in breast cancer. Some studies have identified a

protective effect of ERβ expression in breast cancer cells by

antagonizing the action of Erα (73). Moreover, the expression of ERβ is

associated with a better prognosis and with an increased response

to endocrine therapy (74). Other

studies have reported opposing results, demonstrating that ERβ

expression is associated with adverse outcomes in breast cancer and

is not predictive of resistance to tamoxifen (75,76).

More recently, studies have focused on the protective effects of

ERβ-5 in patients with breast cancer and the positive association

with longer relapse-free survival times. ERβ-5 has also been

reported to induce the sensitivity of breast cancer cell lines to

chemotherapy-induced apoptosis (77,78).

Finally, GPER1 expression is detected in 60% of

breast cancer cases, primarily in Luminal A cases. GPER1

downregulation in the tumor cells is associated with poorer outcome

(66). Likewise, studies have

reported that expression of GPER1 decreases during tamoxifen

treatment. Thus, breast cancers with low expression of GPER1 show

endocrine treatment resistance (79).

The exact mechanisms of action and antagonism of ERs

in different types of cancer is an ongoing area of research, which

may highlight novel strategies for the development of therapeutics

for the management of specific types of cancer. Research on novel

treatments for combating endocrine-resistant tumors is also

ongoing.

ERs in gender dysphoria

ERα and ERβ expression are upregulated during the

development of the central nervous system (CNS) (80). ERα is primarily located in the

hypothalamic nuclei, the periaqueductal grey, the parabrachial

nucleus, the medial amygdala, the preoptic area and on the bed

nucleus of the stria terminalis. ERα is also expressed to a lesser

degree in the locus coeruleus. ERβ is also expressed in the

aforementioned areas, but is primarily expressed in the lateral

septum, the basolateral amygdala and the trigeminal nuclei. Lower

levels of ERβ are also observed in the hippocampus, the locus

coeruleus, the cerebral cortex and the cerebellum. The most

recently discovered ER, GPER1, is also expressed in the brain, with

high levels in the olfactory bulbs, the hypothalamus, cortex, the

hippocampus, and the Purkinje and granule cells of the cerebellum

(80). ERs function in the brain

primarily through non-genomic pathways and to a lesser extent via

the genomic pathways, where ERs regulate brain development, sexual

behavior, cognitive ability, temperature homeostasis and appetite

(81–83).

The masculinization of the brain in humans is

primarily mediated by the androgen receptor (AR) and partly by ERs

(81). In humans, the expression

of aromatase is highest in the thalamus (82). During embryogenesis, fetal

testosterone passes into the brain and is metabolized by the enzyme

aromatase to E2, which exerts its action by binding to ERs, which

masculinizes specific brain regions. It has been previously

reported in mouse knockout studies that ERβ has a defeminization

role in male brains and in male behavior (83). The effects of sex steroids on the

brain during development determine sexual differentiation. A

suggested pathway for brain masculinization is the direct

initiation of gene expression via the activation of AR and ERs.

Gender dysphoria, a marked discordance between experienced gender

and biological sex, is commonly hypothesized to be attributed to

discrepant of typical male or female brain and genital sexual

differentiation (84). The

contribution of ERs to the development of gender incongruence has

been widely studied with contradicting and only partially

convincing results (85,86). Interactions of genes and

polymorphisms may contribute to the polygenic bases of gender

dysphoria. However, genetics is not the only determining factor to

change sexual orientation. The majority of studies that

investigated the implication of the genetic component focused on

polymorphisms related to ERα and ERβ (Table II) (85–92).

| Table II.Studies on the contribution of ERs in

gender dysphoria. |

Table II.

Studies on the contribution of ERs in

gender dysphoria.

| First author,

year | Gender | ERs | Findings | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Henningsson et

al, 2005 | MTF | ERβ | Significant

association with a dinucleotide CA polymorphism in the ERβ gene.

The higher number of CA repeats implies greater transcription

activation and therefore lower feminization or greater

defeminization | (85) |

| Hare et al,

2009 | MTF | ERβ | Unable to replicate

the significant association between longer CA repeat lengths in the

ERβ gene | (86) |

| Ujike et al,

2009 | MTF and FTM | ERβ and ERα | No difference in

allelic or genotypic distribution of the genes, thus no evidence

that genetic variants of sex hormone-related genes confer

individual susceptibility to transsexualism | (87) |

| Fernández et

al, 2014 | MTF and FTM | ERβ | No difference in

allelic or genotypic distribution of the sex hormone-related genes

between transgender patients and controls | (88) |

| Cortés-Cortés et

al, 2017 | MTF and FTM | ERα | The polymorphism

XbaI-rs9340799 and the haplotypes L-C-G and L-C-A are associated

with FTM in adults | (89) |

| Fernández et

al, 2018 | MTF and FTM | ERα and ERβ | The key receptors

implicated in sexual differentiation of the brain have a specific

allele combination for ERβ and ERα in MTFs. The FTM gender is

associated with specific polymorphisms of ERβ and ERα. Thus, ERα

and ERβ serve a key role in the sexual differentiation of the

brain | (90) |

| Foreman et

al, 2019 | MTF | ERα and ERβ | Overrepresented

alleles and genotypes are proposed to under-masculinize/feminize on

the basis of their reported effects in other disease contexts | (91) |

| Ramírez et

al, 2021 | MTF and FTM | ER

coactivators | The coactivators

SRC-1 and SRC-2 could be considered as candidates for increasing

the list of potential genes for gender incongruence. The role of

SRCs in ER-mediated gene expression is known | (92) |

Based on the limited available published data, the

primary receptors involved in sexual differentiation of the brain

have a specific allele combination for ERβ, ERα and AR in trans

females, whose gender incongruence is associated with a specific

genotypic combination of ERs and AR variants. Specific

polymorphisms of ERβ and ERα have also been reported in trans

males. Both ERα and ERβ serve a key role in the typical sexual

differentiation of the human brain. Estrogens, primarily E2,

regulate the growth, development and function of the reproductive

system and the CNS. The mechanisms of ERs and their interactions

with estrogens in gender differentiation are not completely

understood. The two receptors ERα and ERβ bind with the E2 ligand,

resulting in the dimerization of the receptor, resulting in the

necessary fundamental changes in the LBD and thus allowing for

coactivators to be engaged. This step is required for the

transcriptional regulation of gender-determination genes dependent

on E2 (93,94). Moreover, the E2-ER complex

interacts with steroid receptor coactivators (SRCs) to activate the

transcription of the target genes. SRCs can also influence the

ability of the transcription factors to activate or inhibit the

expression of numerous genes (95). There are three SRC members: SRC-1,

SRC-2 and SRC-3. It has been suggested that variations at the DNA

level in SRCs can affect the function of the E2-ER complex and

therefore modify the transcription of the genes regulated by E2.

The coactivators SRC-1 and SRC-2 are hypothesized to serve a key

role in the potential expression of the gene for gender

incongruence (92). Overall, it is

hypothesized that gender incongruence has a complex underlying

pathophysiology that involves interactions between sex steroids,

sex steroid receptors, coactivators and genes (92). Furthermore, reduced androgen levels

and androgen signaling may serve a role in the acquisition of a

female gender identity of male-to-female transsexuals, whereas a

higher number of CA repeats in the ERβ gene lead to reduced ERβ

signaling and inhibit the ERβ dimerization on the male brain, which

results in increased transcriptional activation and thus lower

feminization, may explain the acquisition of a male gender identity

in female-to-male transexuals.

ERs and the aging brain

Estrogens have been recognized as potent

neuroprotective agents. Estrogens, via their ERs, mediate gene

transcription. The participation of ERs in regulating

differentiation, proliferation and inflammation of neurons and

synapses is fundamental to general physiology. The levels of sex

hormones decrease with age, although this decrease is more

pronounced during the menopause in women (96). The levels of ERs in the brain

decrease just after birth and their actions in the CNS become

slowly restricted to different regions of the brain. ERα is

expressed in the amygdala and the hypothalamus, whereas ERβ is

distributed in the cerebral cortex in the cerebellum, hippocampus,

periventricular nuclei, bed nucleus of the stria terminalis,

substantia nigra, ventral tegmental area and the dorsal raphe

nucleus (80,97–99).

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), found in the brain,

regulates synaptic genesis and development (60,80).

BDNF protein levels increase following ERβ activation in

postmenopausal mice, which serves a crucial role in promoting the

survival and differentiation of neurons (60). Both ERα and in particular ERβ,

contribute to neuroprotection via the striatum in the basal ganglia

of the brain, which regulates muscle tone and coordinates motor

ability (99). Hippocampal GPER1

also contributes to estrogen-dependent conciliation memory via the

regulation of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and neuroprotection.

BDNF expression induced by selective GPER1 activation via the

E2-PI3K/Akt and E2-MAPK signaling pathways promotes synaptic

plasticity, exerting a neuroprotective effect (99).

Behavioral manifestations such as emotion and

cognition are controlled by sex steroid hormones and have been

studied by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). During the

follicular and luteal phases in healthy women with a normal

menstrual cycle, fMRI demonstrated differences in several areas of

the brain, such as the amygdala, anterior hippocampus and several

cortical regions (100). The role

of ERs in neurodevelopment is vital in the adult brain, in addition

to their more established roles in sexual behavior and

reproduction.

During aging, several modifications and adjustments

to tissues in the brain occur that result in adverse events. The

levels of both ERα and ERβ, found in synapses of the cornu ammonis

neurons in the hippocampus of female rats, decrease as the animal

ages (101). As the expression of

ERs is associated with neuroprotection, this level of

neuroprotection may decrease as an individual ages, particularly

during pre-menopause and menopause, increasing the risk of adverse

neurological events in women, whereas men, who exhibit a gradual

slow decrease in testosterone levels, may experience longer

neuroprotective effects (102).

Complete loss of estrogen during menopause is associated with

neurological changes, since perimenopausal females have an

increased risk of depression that is reduced when they receive

treatment with estrogens (102,103).

Menopausal women demonstrate a decrease in cognitive

function and in both verbal and working memory. According to the

Women's Health Initiative Memory Study, the incidence of memory and

cognitive impairment in menopausal women was 4.5% (104). Moreover, there is evidence of

changes in the cognitive test performance of women that are

consistently related to the reproductive period and menopausal

transition. Population-based studies reported an increased risk of

dementia by up to 23% in females with late menarche, early

menopause and a short reproductive period (96,105). A recent study investigated the

factors associated with a decrease in cognition and found a

synergistic association with an early age of menopause and vascular

risk impacting the cognitive function in menopausal women for >3

years of follow-up after menopause (106). The same study reported that

hormone treatment with estrogens attenuated this association to

preserve cognition (106).

Conversely, an age-related shift in ERα or ERβ may underlie a

decreased response to E2, suggesting that estrogen treatment may

not always lead to cognitive preservation. The effects of ERα or

ERβ on cognitive function are dose-dependent (107). Furthermore, hormone replacement

will interact with locally produced E2, such that the effective

dose of E2 to optimize hippocampal function will depend on local E2

and the relative expression of functional ERα and Erβ (96).

Neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer's

disease (AD), are associated with estrogen depletion. A higher

prevalence of AD and a more rapid cognitive decline were reported

in women compared with men (106). Furthermore, a meta-analysis

reported that estrogen replacement treatment could benefit

postmenopausal women with neurodegenerative disease (108). Numerous studies have reported the

neuroprotective function of estrogens, including acting as

antioxidants, enabling DNA repair, inducing growth factor

expression and regulating cerebral blood flow. Parkinson's disease

(PD) affects motor skills, followed by cognitive impairment. Women

with lower estrogen levels are more likely to develop PD compared

with those with higher estrogen levels (60,108). The role of estrogen-based

treatments in this group of women for the prevention of dementia,

loss of motor ability and depression is still under evaluation.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Undoubtedly, an understanding of the role of ERs in

different tissues, the estrogen signaling mechanisms and the

interactions between the three ERs (ERα, Erβ and GPER1) is required

for the development of novel therapeutics. Bridging the gap between

animal and human studies may open future research avenues for the

development of novel treatments for ER-related diseases. Notably,

ER signaling members in cancer may be targets for next-generation

ER-targeted treatments. The rising incidence of breast cancer and

also other types of cancer, related to ER pathology, is a hallmark

for the need for more targeted treatments focused on ERs. Existing

hormonal auxiliary treatments for osteoporosis are promising.

However, the association between hormone replacement therapy and

the development of breast cancer highlights the need for more

targeted treatments focusing on ER signaling pathways. Although

notable advancements have been made regarding sex hormone signaling

in the brain, a deeper understanding of the spatiotemporal

expression and ER signaling in the brain is still required. Further

research on the physiological and pathophysiological aging of the

brain and the differences between sexes observed in these processes

is required. In vivo and integrated in vitro studies

assessing the neuroprotective effects of estrogen highlight ERs as

potential therapeutic targets in neurodegenerative diseases and

aging.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

MT wrote, edited and reviewed the article. AK and KP

wrote the structure, location, function of ERs sections of the

article. NS wrote, edited, reviewed and supervised the writing of

the manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Green S, Walter P, Kumar V, Krust A,

Bornert JM, Argos P and Chambon P: Human oestrogen receptor cDNA:

Sequence, expression and homology to v-erb-A. Nature. 320:134–139.

1986. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Jameson L, De Groot LJ, de Kretser DM,

Giudice LC, Grossman AB, Melmed S, Potts JT and Weir GC:

Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric. 7th edition. W.B Saunders;

Philadelphia, PH: pp. 2200–2350. 2016

|

|

3

|

Fuentes N and Silveyra P: Estrogen

receptor signaling mechanisms. Adv Protein Chem Struct Biol.

116:135–170. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Faltas CL, LeBron KA and Holz MK:

Unconventional estrogen signaling in health and disease.

Endocrinology. 161:bqaa0302020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Hazell GG, Yao ST, Roper JA, Prossnitz ER,

O'Carroll AM and Lolait SJ: Localisation of GPR30, a novel G

protein-coupled oestrogen receptor, suggests multiple functions in

rodent brain and peripheral tissues. J Endocrinol. 202:223–236.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Arterburn JB and Prossnitz ER: G

Protein-Coupled Estrogen Receptor GPER: Molecular pharmacology and

therapeutic applications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 63:295–320.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Björnström L and Sjöberg M: Mechanisms of

estrogen receptor signaling: Convergence of genomic and nongenomic

actions on target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 19:833–842. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Williams C, Edvardsson K, Lewandowski SA,

Ström A and Gustafsson JA: A genome-wide study of the repressive

effects of estrogen receptor beta on estrogen receptor alpha

signaling in breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 27:1019–1032. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Klinge CM, Jernigan SC, Smith SL,

Tyulmenkov VV and Kulakosky PC: Estrogen response element sequence

impacts the conformation and transcriptional activity of estrogen

receptor alpha. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 174:151–166. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Clusan L, Ferrière F, Flouriot G and

Pakdel F: A basic review on estrogen receptor signaling pathways in

breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 24:68342023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bord S, Horner A, Beavan S and Compston J:

Estrogen receptors alpha and beta are differentially expressed in

developing human bone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 86:2309–2314. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Gosden JR, Middleton PG and Rout D:

Localization of the human oestrogen receptor gene to chromosome

6q24-q27 by in situ hybridization. Cytogenet Cell Genet.

43:218–220. 1986. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Enmark E, Pelto-Huikko M, Grandien K,

Lagercrantz S, Lagercrantz J, Fried G, Nordenskjöld M and

Gustafsson JA: Human estrogen receptor beta-gene structure,

chromosomal localization and expression pattern. J Clin Endocrinol

Metab. 82:4258–4265. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Kumar R, Zakharov MN, Khan SH, Miki R,

Jang H, Toraldo G, Singh R, Bhasin S and Jasuja R: The dynamic

structure of the estrogen receptor. J Amino Acids. 2011:8125402011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Hewitt SC and Korach KS: Estrogen

receptors: Structure, mechanisms and function. Rev Endocr Metab

Disord. 3:193–200. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Barton M, Filardo EJ, Lolait SJ, Thomas P,

Maggiolini M and Prossnitz ER: Twenty years of the G

protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPER: Historical and personal

perspectives. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 176:4–15. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Saito K and Cui H: Estrogen receptor alpha

splice variants, post-translational modifications and their

physiological functions. Cells. 12:8952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Flouriot G, Brand H, Denger S, Metivier R,

Kos M, Reid G, Sonntag-Buck V and Gannon F: Identification of a new

isoform of the human estrogen receptor-alpha (hER-alpha) that is

encoded by distinct transcripts and that is able to repress

hER-alpha activation function 1. EMBO J. 19:4688–4700. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Wang Z, Zhang X, Shen P, Loggie BW, Chang

Y and Deuel TF: Identification, cloning and expression of human

estrogen receptor-alpha36, a novel variant of human estrogen

receptor-alpha66. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 336:1023–1027. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Warner M, Fan X, Strom A, Wu W and

Gustafsson JÅ: 25 years of ERβ: A personal journey. J Mol

Endocrinol. 68:R1–R9. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Monteiro FL, Stepanauskaite L, Archer A

and Williams C: Estrogen receptor beta expression and role in

cancers. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 242:1065262024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Jia M, Dahlman-Wright K and Gustafsson JÅ:

Estrogen receptor alpha and beta in health and disease. Best Pract

Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 29:557–568. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Arao Y and Korach KS: The physiological

role of estrogen receptor functional domains. Essays Biochem.

65:867–875. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Stender JD, Kim K, Charn TH, Komm B, Chang

KC, Kraus WL, Benner C, Glass CK and Katzenellenbogen BS:

Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor alpha DNA binding and

tethering mechanisms identifies Runx1 as a novel tethering factor

in receptor-mediated transcriptional activation. Mol Cell Biol.

30:3943–3955. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Song RX, Zhang Z and Santen RJ: Estrogen

rapid action via protein complex formation involving ERalpha and

Src. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 16:347–353. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Kelly MJ and Levin ER: Rapid actions of

plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends Endocrinol Metab.

12:152–156. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Castoria G, Migliaccio A, Bilancio A, Di

Domenico M, de Falco A, Lombardi M, Fiorentino R, Varricchio L,

Barone MV and Auricchio F: PI3-kinase in concert with Src promotes

the S-phase entry of oestradiol-stimulated MCF-7 cells. EMBO J.

20:6050–6059. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pedram A, Razandi M, Aitkenhead M, Hughes

CC and Levin ER: Integration of the non-genomic and genomic actions

of estrogen. Membrane-initiated signaling by steroid to

transcription and cell biology. J Biol Chem. 277:50768–50775. 2002.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Delmas PD: Treatment of postmenopausal

osteoporosis. Lancet. 359:2018–2026. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Lindberg MK, Erlandsson M, Alatalo SL,

Windahl S, Andersson G, Halleen JM, Carlsten H, Gustafsson JA and

Ohlsson C: Estrogen receptor alpha, but not estrogen receptor beta,

is involved in the regulation of the OPG/RANKL

(osteoprotegerin/receptor activator of NF-kappa B ligand) ratio and

serum interleukin-6 in male mice. J Endocrinol. 171:425–433. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Nakamura T, Imai Y, Matsumoto T, Sato S,

Takeuchi K, Igarashi K, Harada Y, Azuma Y, Krust A, Yamamoto Y, et

al: Estrogen prevents bone loss via estrogen receptor alpha and

induction of Fas ligand in osteoclasts. Cell. 130:811–823. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Börjesson AE, Windahl SH, Karimian E,

Eriksson EE, Lagerquist MK, Engdahl C, Antal MC, Krust A, Chambon

P, Sävendahl L and Ohlsson C: The role of estrogen receptor-α and

its activation function-1 for growth plate closure in female mice.

Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 302:E1381–E1389. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Martin-Millan M, Almeida M, Ambrogini E,

Han L, Zhao H, Weinstein RS, Jilka RL, O'Brien CA and Manolagas SC:

The estrogen receptor-alpha in osteoclasts mediates the protective

effects of estrogens on cancellous but not cortical bone. Mol

Endocrinol. 24:323–334. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Manolagas SC, O'Brien CA and Almeida M:

The role of estrogen and androgen receptors in bone health and

disease. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 9:699–712. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Almeida M, Han L, Martin-Millan M, O'Brien

CA and Manolagas SC: Oxidative stress antagonizes Wnt signaling in

osteoblast precursors by diverting beta-catenin from T cell factor-

to forkhead box O-mediated transcription. J Biol Chem.

282:27298–27305. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Smith EP, Boyd J, Frank GR, Takahashi H,

Cohen RM, Specker B, Williams TC, Lubahn DB and Korach KS: Estrogen

resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a

man. N Engl J Med. 331:1056–1061. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Rochira V and Carani C: Aromatase

deficiency in men: A clinical perspective. Nat Rev Endocrinol.

5:559–568. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Morishima A, Grumbach MM, Simpson ER,

Fisher C and Qin K: Aromatase deficiency in male and female

siblings caused by a novel mutation and the physiological role of

estrogens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 80:3689–3698. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Conte FA, Grumbach MM, Ito Y, Fisher CR

and Simpson ER: A syndrome of female pseudohermaphrodism,

hypergonadotropic hypogonadism and multicystic ovaries associated

with missense mutations in the gene encoding aromatase (P450arom).

J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 78:1287–1292. 1994. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Chen GG, Zeng Q and Tse GM: Estrogen and

its receptors in cancer. Med Res Rev. 28:954–974. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Chan KKL, Siu MKY, Jiang YX, Wang JJ, Wang

Y, Leung THY, Liu SS, Cheung ANY and Ngan HYS: Differential

expression of estrogen receptor subtypes and variants in ovarian

cancer: Effects on cell invasion, proliferation and prognosis. BMC

Cancer. 17:6062017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Ciucci A, Zannoni GF, Travaglia D,

Petrillo M, Scambia G and Gallo D: Prognostic significance of the

estrogen receptor beta (ERβ) isoforms ERβ1, ERβ2 and ERβ5 in

advanced serous ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 132:351–359. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ignatov T, Modl S, Thulig M, Weißenborn C,

Treeck O, Ortmann O, Zenclussen A, Costa SD, Kalinski T and Ignatov

A: GPER-1 acts as a tumor suppressor in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian

Res. 6:512013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Smith HO, Arias-Pulido H, Kuo DY, Howard

T, Qualls CR, Lee SJ, Verschraegen CF, Hathaway HJ, Joste NE and

Prossnitz ER: GPR30 predicts poor survival for ovarian cancer.

Gynecol Oncol. 114:465–471. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Ramírez-de-Arellano A, Pereira-Suárez AL,

Rico-Fuentes C, López-Pulido EI, Villegas-Pineda JC and Sierra-Diaz

E: Distribution and effects of estrogen receptors in prostate

cancer: Associated molecular mechanisms. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 12:8115782022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Bonkhoff H: Estrogen receptor signaling in

prostate cancer: Implications for carcinogenesis and tumor

progression. Prostate. 78:2–10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Ryu WS, Kim JH, Jang YJ, Park SS, Um JW,

Park SH, Kim SJ, Mok YJ and Kim CS: Expression of estrogen

receptors in gastric cancer and their clinical significance. J Surg

Oncol. 106:456–461. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Deng H, Huang X, Fan J, Wang L, Xia Q,

Yang X, Wang Z and Liu L: A variant of estrogen receptor-alpha,

ER-alpha36 is expressed in human gastric cancer and is highly

correlated with lymph node metastasis. Oncol Rep. 24:171–176.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Xu CY, Guo JL, Jiang ZN, Xie SD, Shen JG,

Shen JY and Wang LB: Prognostic role of estrogen receptor alpha and

estrogen receptor beta in gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol.

17:2503–2509. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Jacenik D and Krajewska WM: Significance

of G protein-coupled estrogen receptor in the pathophysiology of

irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel diseases and

colorectal cancer. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 11:3902020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Baldissera VD, Alves AF, Almeida S,

Porawski M and Giovenardi M: Hepatocellular carcinoma and estrogen

receptors: Polymorphisms and isoforms relations and implications.

Med Hypotheses. 86:67–70. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Wei T, Chen W, Wen L, Zhang J, Zhang Q,

Yang J, Liu H, Chen BW, Zhou Y, Feng X, et al: G protein-coupled

estrogen receptor deficiency accelerates liver tumorigenesis by

enhancing inflammation and fibrosis. Cancer Lett. 382:195–202.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Gupta VK, Banerjee S and Saluja AK:

Learning from gender disparity: Role of estrogen receptor

activation in coping with pancreatic cancer. Cell Mol Gastroenterol

Hepatol. 10:862–863. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Dika E, Patrizi A, Lambertini M,

Manuelpillai N, Fiorentino M, Altimari A, Ferracin M, Lauriola M,

Fabbri E, Campione E, et al: Estrogen receptors and melanoma: A

review. Cells. 8:14632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

He M, Yu W, Chang C, Miyamoto H, Liu X,

Jiang K and Yeh S: Estrogen receptor α promotes lung cancer cell

invasion via increase of and cross-talk with infiltrated

macrophages through the CCL2/CCR2/MMP9 and CXCL12/CXCR4 signaling

pathways. Mol Oncol. 14:1779–1799. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Liu S, Hu C, Li M, An J, Zhou W, Guo J and

Xiao Y: Estrogen receptor beta promotes lung cancer invasion via

increasing CXCR4 expression. Cell Death Dis. 13:702022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Liu C, Liao Y, Fan S, Tang H, Jiang Z,

Zhou B, Xiong J, Zhou S, Zou M and Wang J: G protein-coupled

estrogen receptor (GPER) mediates NSCLC progression induced by

17β-estradiol (E2) and selective agonist G1. Med Oncol. 32:1042015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Heer E, Harper A, Escandor N, Sung H,

McCormack V and Fidler-Benaoudia MM: Global burden and trends in

premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancer: A population-based

study. Lancet Glob Health. 8:e1027–e1037. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Cserni G: Histological type and typing of

breast carcinomas and the WHO classification changes over time.

Pathologica. 112:25–41. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Chen P, Li B and Ou-Yang L: Role of

estrogen receptors in health and disease. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13:8390052022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Huang B, Omoto Y, Iwase H, Yamashita H,

Toyama T, Coombes RC, Filipovic A, Warner M and Gustafsson JÅ:

Differential expression of estrogen receptor α, β1 and β2 in

lobular and ductal breast cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

111:1933–1938. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Beral V; Million Women Study

Collaborators, : Breast cancer and hormone-replacement therapy in

the Million Women Study. Lancet. 362:419–427. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Salagame U, Canfell K and Banks E: An

epidemiological overview of the relationship between hormone

replacement therapy and breast cancer. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab.

6:397–409. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Meng YG, Han WD, Zhao YL, Huang K, Si YL,

Wu ZQ and Mu YM: Induction of the LRP16 gene by estrogen promotes

the invasive growth of Ishikawa human endometrial cancer cells

through the downregulation of E-cadherin. Cell Res. 17:869–880.

2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Xu X, Zhang M, Xu F and Jiang S: Wnt

signaling in breast cancer: Biological mechanisms, challenges and

opportunities. Mol Cancer. 19:1652020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Anbalagan M and Rowan BG: Estrogen

receptor alpha phosphorylation and its functional impact in human

breast cancer. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 418:Pt 3:264–272. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Tsai EM, Wang SC, Lee JN and Hung MC: Akt

activation by estrogen in estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 61:8390–8392. 2001.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Dustin D, Gu G and Fuqua SAW: ESR1

mutations in breast cancer. Cancer. 125:3714–3728. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Toy W, Weir H, Razavi P, Lawson M,

Goeppert AU, Mazzola AM, Smith A, Wilson J, Morrow C, Wong WL, et

al: Activating ESR1 mutations differentially affect the efficacy of

ER antagonists. Cancer Discov. 7:277–287. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Klinge CM, Riggs KA, Wickramasinghe NS,

Emberts CG, McConda DB, Barry PN and Magnusen JE: Estrogen receptor

alpha 46 is reduced in tamoxifen resistant breast cancer cells and

re-expression inhibits cell proliferation and estrogen receptor

alpha 66-regulated target gene transcription. Mol Cell Endocrinol.

323:268–276. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Wang ZY and Yin L: Estrogen receptor

alpha-36 (ER-α36): A new player in human breast cancer. Mol Cell

Endocrinol. 418:Pt 3:193–206. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Giacinti L, Claudio PP, Lopez M and

Giordano A: Epigenetic information and estrogen receptor alpha

expression in breast cancer. Oncologist. 11:1–8. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Zhao C, Matthews J, Tujague M, Wan J,

Ström A, Toresson G, Lam EW, Cheng G, Gustafsson JA and

Dahlman-Wright K: Estrogen receptor beta2 negatively regulates the

transactivation of estrogen receptor alpha in human breast cancer

cells. Cancer Res. 67:3955–3962. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Hopp TA, Weiss HL, Parra IS, Cui Y,

Osborne CK and Fuqua SA: Low levels of estrogen receptor b protein

predict resistance to tamoxifen therapy in breast cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 10:7490–7499. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Markey GC, Cullen R, Diggin P, Hill AD, Mc

Dermott EW, O'Higgins NJ and Duffy MJ: Estrogen receptor-beta mRNA

is associated with adverse outcome in patients with breast cancer.

Tumour Biol. 30:171–175. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Esslimani-Sahla M, Simony-Lafontaine J,

Kramar A, Lavaill R, Mollevi C, Warner M, Gustafsson JA and

Rochefort H: Estrogen receptor beta (ER beta) level but not its ER

beta cx variant helps to predict tamoxifen resistance in breast

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 10:5769–5776. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Shaaban AM, Green AR, Karthik S, Alizadeh

Y, Hughes TA, Harkins L, Ellis IO, Robertson JF, Paish EC, Saunders

PT, et al: Nuclear and cytoplasmic expression of ERbeta1, ERbeta2

and ERbeta5 identifies distinct prognostic outcome for breast

cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 14:5228–5235. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Lee MT, Ho SM, Tarapore P, Chung I and

Leung YK: Estrogen receptor β isoform 5 confers sensitivity of

breast cancer cell lines to chemotherapeutic agent-induced

apoptosis through interaction with Bcl2L12. Neoplasia.

15:1262–1271. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Ignatov T, Weißenborn C, Poehlmann A,

Lemke A, Semczuk A, Roessner A, Costa SD, Kalinski T and Ignatov A:

GPER-1 expression decreases during breast cancer tumorigenesis.

Cancer Invest. 31:309–315. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Fan X, Xu H, Warner M and Gustafsson JA:

ERbeta in CNS: New roles in development and function. Prog Brain

Res. 181:233–250. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Zuloaga DG, Puts DA, Jordan CL and

Breedlove SM: The role of androgen receptors in the masculinization

of brain and behavior: What we've learned from the testicular

feminization mutation. Horm Behav. 53:613–626. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Biegon A: In vivo visualization of

aromatase in animals and humans. Front Neuroendocrinol. 40:42–51.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Kudwa AE, Bodo C, Gustafsson JA and

Rissman EF: A previously uncharacterized role for estrogen receptor

beta: Defeminization of male brain and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 102:4608–4612. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Skordis N, Kyriakou A, Dror S, Mushailov A

and Nicolaides NC: Gender dysphoria in children and adolescents: An

overview. Hormones (Athens). 19:267–276. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Henningsson S, Westberg L, Nilsson S,

Lundström B, Ekselius L, Bodlund O, Lindström E, Hellstrand M,

Rosmond R, Eriksson E and Landén M: Sex steroid-related genes and

male-to-female transsexualism. Psychoneuroendocrinology.

30:657–664. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Hare L, Bernard P, Sánchez FJ, Baird PN,

Vilain E, Kennedy T and Harley VR: Androgen receptor repeat length

polymorphism associated with male-to-female transsexualism. Biol

Psychiatry. 65:93–96. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Ujike H, Otani K, Nakatsuka M, Ishii K,

Sasaki A, Oishi T, Sato T, Okahisa Y, Matsumoto Y, Namba Y, et al:

Association study of gender identity disorder and sex

hormone-related genes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry.

33:1241–1244. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Fernández R, Esteva I, Gómez-Gil E, Rumbo

T, Almaraz MC, Roda E, Haro-Mora JJ, Guillamón A and Pásaro E:

Association study of ERβ, AR and CYP19A1 genes and MtF

transsexualism. J Sex Med. 11:2986–2994. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Cortés-Cortés J, Fernández R, Teijeiro N,

Gómez-Gil E, Esteva I, Almaraz MC, Guillamón A and Pásaro E:

Genotypes and Haplotypes of the Estrogen Receptor α Gene (ESR1) Are

Associated With Female-to-Male Gender Dysphoria. J Sex Med.

14:464–472. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Fernández R, Guillamon A, Cortés-Cortés J,

Gómez-Gil E, Jácome A, Esteva I, Almaraz M, Mora M, Aranda G and

Pásaro E: Molecular basis of Gender Dysphoria: Androgen and

estrogen receptor interaction. Psychoneuroendocrinology.

98:161–167. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Foreman M, Hare L, York K, Balakrishnan K,

Sánchez FJ, Harte F, Erasmus J, Vilain E and Harley VR: Genetic

link between gender dysphoria and sex hormone signaling. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 104:390–396. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Ramírez KDV, Fernández R, Delgado-Zayas E,

Gómez-Gil E, Esteva I, Guillamon A and Pásaro E: Implications of

the Estrogen Receptor Coactivators SRC1 and SRC2 in the Biological

Basis of Gender Incongruence. Sex Med. 9:1003682021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Nilsson S, Mäkelä S, Treuter E, Tujague M,

Thomsen J, Andersson G, Enmark E, Pettersson K, Warner M and

Gustafsson JA: Mechanisms of estrogen action. Physiol Rev.

81:1535–1565. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

McKenna NJ, Lanz RB and O'Malley BW:

Nuclear receptor coregulators: Cellular and molecular biology.

Endocr Rev. 20:321–344. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Yi P, Wang Z, Feng Q, Pintilie GD, Foulds

CE, Lanz RB, Ludtke SJ, Schmid MF, Chiu W and O'Malley BW:

Structure of a biologically active estrogen receptor-coactivator

complex on DNA. Mol Cell. 57:1047–1058. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Maioli S, Leander K, Nilsson P and

Nalvarte I: Estrogen receptors and the aging brain. Essays Biochem.

65:913–925. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Osterlund MK and Hurd YL: Estrogen

receptors in the human forebrain and the relation to

neuropsychiatric disorders. Prog Neurobiol. 64:251–267. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Mehra RD, Sharma K, Nyakas C and Vij U:

Estrogen receptor alpha and beta immunoreactive neurons in normal

adult and aged female rat hippocampus: A qualitative and

quantitative study. Brain Res. 1056:22–35. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

González M, Cabrera-Socorro A,

Pérez-García CG, Fraser JD, López FJ, Alonso R and Meyer G:

Distribution patterns of estrogen receptor alpha and beta in the

human cortex and hippocampus during development and adulthood. J

Comp Neurol. 503:790–802. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Toffoletto S, Lanzenberger R, Gingnell M,

Sundström-Poromaa I and Comasco E: Emotional and cognitive

functional imaging of estrogen and progesterone effects in the

female human brain: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology.

50:28–52. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Waters EM, Yildirim M, Janssen WG, Lou WY,

McEwen BS, Morrison JH and Milner TA: Estrogen and aging affect the

synaptic distribution of estrogen receptor β-immunoreactivity in

the CA1 region of female rat hippocampus. Brain Res. 1379:86–97.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Morrison JH, Brinton RD, Schmidt PJ and

Gore AC: Estrogen, menopause and the aging brain: How basic

neuroscience can inform hormone therapy in women. J Neurosci.

26:10332–10348. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Dwyer JB, Aftab A, Radhakrishnan R, Widge

A, Rodriguez CI, Carpenter LL, Nemeroff CB, McDonald WM and Kalin

NH; APA Council of Research Task Force on Novel Biomarkers and

Treatments, : Hormonal treatments for major depressive disorder:

State of the Art. Am J Psychiatry. 177:686–705. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

Goveas JS, Espeland MA, Woods NF,

Wassertheil-Smoller S and Kotchen JM: Depressive symptoms and

incidence of mild cognitive impairment and probable dementia in

elderly women: The Women's Health Initiative Memory Study. J Am

Geriatr Soc. 59:57–66. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Kilpi F, Soares ALG, Fraser A, Nelson SM,

Sattar N, Fallon SJ, Tilling K and Lawlor DA: Changes in six

domains of cognitive function with reproductive and chronological

ageing and sex hormones: A longitudinal study in 2411 UK mid-life

women. BMC Womens Health. 20:1772020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Wood Alexander M, Wu CY, Coughlan GT, Puri

T, Buckley RF, Palta P, Swardfager W, Masellis M, Galea LAM,

Einstein G, et al: Associations between age at menopause, vascular

risk and 3-year cognitive change in the canadian longitudinal study

on aging. Neurology. 102:e2092982024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Georgakis MK, Kalogirou EI, Diamantaras

AA, Daskalopoulou SS, Munro CA, Lyketsos CG, Skalkidou A and

Petridou ET: Age at menopause and duration of reproductive period

in association with dementia and cognitive function: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 73:224–243.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

108

|

Song YJ, Li SR, Li XW, Chen X, Wei ZX, Liu

QS and Cheng Y: The effect of estrogen replacement therapy on

Alzheimer's disease and parkinson's disease in postmenopausal

women: A meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. 14:1572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|