Introduction

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) is

highly prevalent and accounts for the majority of mortalities

worldwide (1). Characterized by a

chronic non-resolving low-grade sterile inflammation of the

arterial wall, atherosclerosis (AS) is mainly caused by low-density

lipoprotein (LDL) (2). The main

lesions in AS are characterized by LDL deposition in the intima,

the innermost layer of the artery wall. Activated by such stimuli,

endothelial cells express a leukocyte adhesion molecule, such as

vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, interacting with its cognate

ligands to promote the rolling and adherence of monocytes and

lymphocytes, accompanied by smooth muscle cells and fibrous matrix

proliferation, which gradually develop into the formation of an AS

plaque (3). Lipoproteins

sequestered in the arterial wall are susceptible to modifications,

such as oxidation, which render these particles pro-inflammatory

and immunogenic. Recruited monocytes mature into mononuclear

phagocytes, take in normal or modified lipoproteins and transform

into foam cells, a type of macrophage that promotes disease

progression. Above various cell types in AS plaques, macrophages

and foam cells are considered to be major contributors to

atherogenesis: Not only do they respond inflammatorily through the

secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators, matrix-degrading proteases

and final death, but also release lipid contents and tissue

factors, constituting a pro-thrombotic necrotic core after necrosis

or apoptosis (4). Thus, the

dynamics of macrophages should play a decisive part in

atherogenesis.

In contrast to traditional immunology, researchers

recently found the capacity of the innate immune system to build an

inflammatory memory named trained immunity. Trained immunity

possesses most prosperities from innate immunity and has the

ability to give a rapid response in reinfection, which is built on

epigenetic and metabolic reprogramming. The inflammatory memory

gifts the host both protection and susceptibility to

inflammation-driven diseases such as AS. As monocytes and

macrophages have a major role in atherogenesis and are widely

investigated in the field of trained immunity, the present review

will focus on them. After elaborating on trained immunity,

phenotypes of macrophages under signals in AS plaques will be

discussed. The mechanisms of this immune memory in trained AS

macrophages in aspects of metabolism, transcription and epigenetics

will then be presented, which may inspire future treatments of the

disease.

Trained immunity: A novel mechanism of

AS

Trained immunity

In the traditional cognation of immunology, in

contrast of adaptive immunity, innate immunity is unable to build

an immunological memory. However, prompted by evidence of

protection against reinfection in plants and invertebrates,

transplant rejection in invertebrates and cross-protection between

infections in mammals with dysfunctional T and B lymphocytes, Netea

et al (5) named the

inflammatory memory in innate immune cells ‘trained immunity’,

which represented hyper-responsiveness in the innate immune system

facing a second stimulus.

Like innate immunity, trained immunity is built on

pattern recognition receptors allowing recognition of different

kinds of, but not individual, pathogens (6) and induced by stimuli, including

pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated

molecular patterns (7). Also, its

properties have been described mainly in populations of innate

immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages and natural killer

(NK) cells. Studies have indicated the existence of trained

hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells (8), along with an inflammatory memory in

epidermal stem cells (9), showing

a broader scale of trained immunity both in time and space. The

innate immune memory lays its basis on epigenetic reprogramming in

the first stimulation (10), which

persists after the removal of the stimulus and leads to accessible

chromatin and rapid recruitment of RNA polymerase II (11) in the reinfection.

While trained immunity guarantees the host a rapid

response and better protection against restimulation, it brings the

potential danger of inflammatory disorders and cancer. For

instance, it was found that once infected, a pregnant individual

with higher levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) passed on the

inflammatory memory to the fetal intestinal epithelium, which

persisted to adulthood. As a result, inflammatory-primed intestinal

stem cells showed both enhanced protection against

Salmonella infection and worsened pathology in a model of

colitis (12). Studies have been

centered widely around the maladaptation of the innate immune

memory and diseases, such as periodontitis (13) and Alzheimer's disease (14). AS, as a chronic inflammatory

disease, is no exception.

Trained immunity in AS

Trained immunity can be induced by endogenous

ligands, such as oxidized (ox)LDL (15), which has a major role in

atherogenesis, indicating the contribution of this proinflammatory

memory to AS. In fact, not only do traditional risk factors such as

dyslipidemia and hypertension predispose individuals to ASCVD via

trained immunity, but other factors, including lifestyle factors,

inflammatory conditions and acute adverse cardiovascular events,

were well classified in a review by Riksen et al (16).

Relevant research has also been conducted at the

cellular level. For instance, isolated human monocytes were shown

to mature into macrophages responding with enhanced production of

tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IL-6 after brief stimulation by

oxLDL (15). Also, in a clinical

trial, isolated monocytes from patients with ASCVD had a higher

capacity of cytokine production than those from healthy subjects

(17). The property was indicated

to be maintained following conversion to macrophages. Furthermore,

trained immunity was shown to be induced not only in circulating

monocytes and tissue-resident macrophages, but also in

hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, termed central trained

immunity, which guaranteed a long-term inflammatory memory

(18). Other immune and non-immune

cells related to AS, such as NK cells (19), neutrophils (20), dendritic cells (21) and endothelial cells (22), have also shown this potential, but

as monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages make a predominant

contribution in all phases of AS (4), the present review will mainly focus

on them.

Phenotypes of macrophages in AS

Aside from functional reprogramming of trained

immunity, another form of immune cell adaption is differentiation

(23). Monocytes infiltrating the

sub-endothelium are exposed to multiple microenvironmental signals,

such as pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, irons, calcium,

lipids and their derivatives and heme from senescent erythrocytes.

Initially, they differentiate into M0 macrophages, also known as

resident-like macrophages, which can then become polarized into

several categories of macrophages (24). Previously, these cells were

classified by their activation states, such as classical,

alternative and innate activation and deactivation (25); while, nowadays, they are mostly

recognized by their secreta and the expression of various surface

markers.

Above all of the subtypes, M1 and M2 were first

described. M1 macrophages are classically activated by products of

type-1 T-helper lymphocytes, such as interferon-γ. In AS plaques,

observations suggested that cholesterol crystals (26), oxLDL (27,28)

and pro-inflammatory cytokines drive, alone or in combination, M1

activation. Trained M1 macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory

cytokines, such as IL-6, IL-1β, TNF, IL-23 and IL-12 (29), sustain inflammatory response and

cause tissue damage. At the opposite end, M2 macrophages, mainly

referred to as anti-inflammatory macrophages, are classically

activated by IL-4 and IL-13 cytokines produced by type 2 T-helper

cells (30,31). Activated by different signals, M2

macrophages have been classified into M2a, M2b and M2c, functioning

separately. While M2a macrophages are classically regarded as

‘wound healing macrophages’, M2b and M2c macrophages are considered

to be ‘regulatory macrophages’ (32). Studies on mice or humans have found

other types of macrophages: Mox, M4, M(Hb) and Mhem macrophages.

Mox macrophages found in mice are induced by oxLDL and act in a

proatherogenic way. M4 macrophages are induced by platelets, while

M(Hb) and Mhem macrophages are induced by the uptake of free

hemoglobin (33). Of note, those

polarized macrophages are able to depolarize and switch their

phenotypes in different microenvironments (34) (Table

I).

| Table I.Phenotypes of macrophages in

atherosclerosis. |

Table I.

Phenotypes of macrophages in

atherosclerosis.

| Phenotype | Stimulus | Secreta |

|---|

| M1 macrophage | Cholesterol

crystals, lipopolysaccharide, proinflammatory cytokines, oxidized

LDL | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α,

IL-23, IL-12 |

| M2 macrophage |

|

|

|

M2a | IL-4, IL-13 | Fibronectin,

insulin-like growth factor, TGF-β |

|

M2b | Immune complexes,

IL-1β, lipopolysaccharide | IL-6, IL-1β, TNF-α,

IL-10, TGF-β1 |

|

M2c | IL-10,

glucocorticoids, TGF-β | IL-10, TGF-β,

Pentraxin-3, MERTKa |

| Mox macrophage | Oxidized

phospholipids | IL-1β,

cyclooxygenase 2 |

| M4 macrophage | C-X-C motif

chemokine ligand 4 | IL-6, TNF-α,

MMP-7 |

| M(Hb)

macrophage |

Haemoglobin/haptoglobin | IL-10 |

| Mhem

macrophage | Haem | IL-10 HMOX-1 |

In the context of AS, M1 and M2 macrophages were

shown to constitute 40 and 20% of total AS lesion macrophages,

respectively, in mice (35).

Furthermore, they possess distinct properties and separate tissue

localizations: While M1 macrophages localize near the lipid core

(36) and impair wound healing

(37), M2 macrophages are more

enriched in neo-angiogenic areas within the plaque (36) and more related to AS regression

(38). Since M1 and M2 macrophages

play a significant role in AS and have been widely studied, this

review will mainly focus on them.

Metabolic changes in trained

macrophages

Cellular metabolism not only follows and meets

energy demands, but also creates intermediate metabolites serving

important biological roles and responds to environmental cues by

regulating the functional state of cells (39,40).

The metabolism of macrophages in AS is no exception. Within AS

plaques, through external stimuli and corresponding signaling

pathways, intracellular metabolism reprograms and induces

epigenetic reprogramming, which mediates trained immunity and

macrophage phenotypes (16).

Furthermore, metabolic reprogramming occurs not only in macrophages

located in AS plaques, but also in circulating monocytes and their

bone marrow progenitors exposed to pro-atherogenic stimuli such as

lipoproteins (41), creating a

long-lasting inflammatory memory.

Via pathway analysis, genome-wide transcriptome and

histone modification profiling, Cheng et al (42) found that β-glucan-trained murine

monocytes showed elevated aerobic glycolysis with a reduced basal

respiration rate, as well as increased glucose consumption and

lactate production; further investigation suggested the

dectin-1/Akt/mTOR-hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1α pathway

responsible for the metabolic shift. The results indicated aerobic

glycolysis (Warburg effect) as a metabolic basis of trained

immunity. Further metabolic pathways, such as fatty acid oxidation

(FAO) and fatty acid synthesis (FAS), also have important roles in

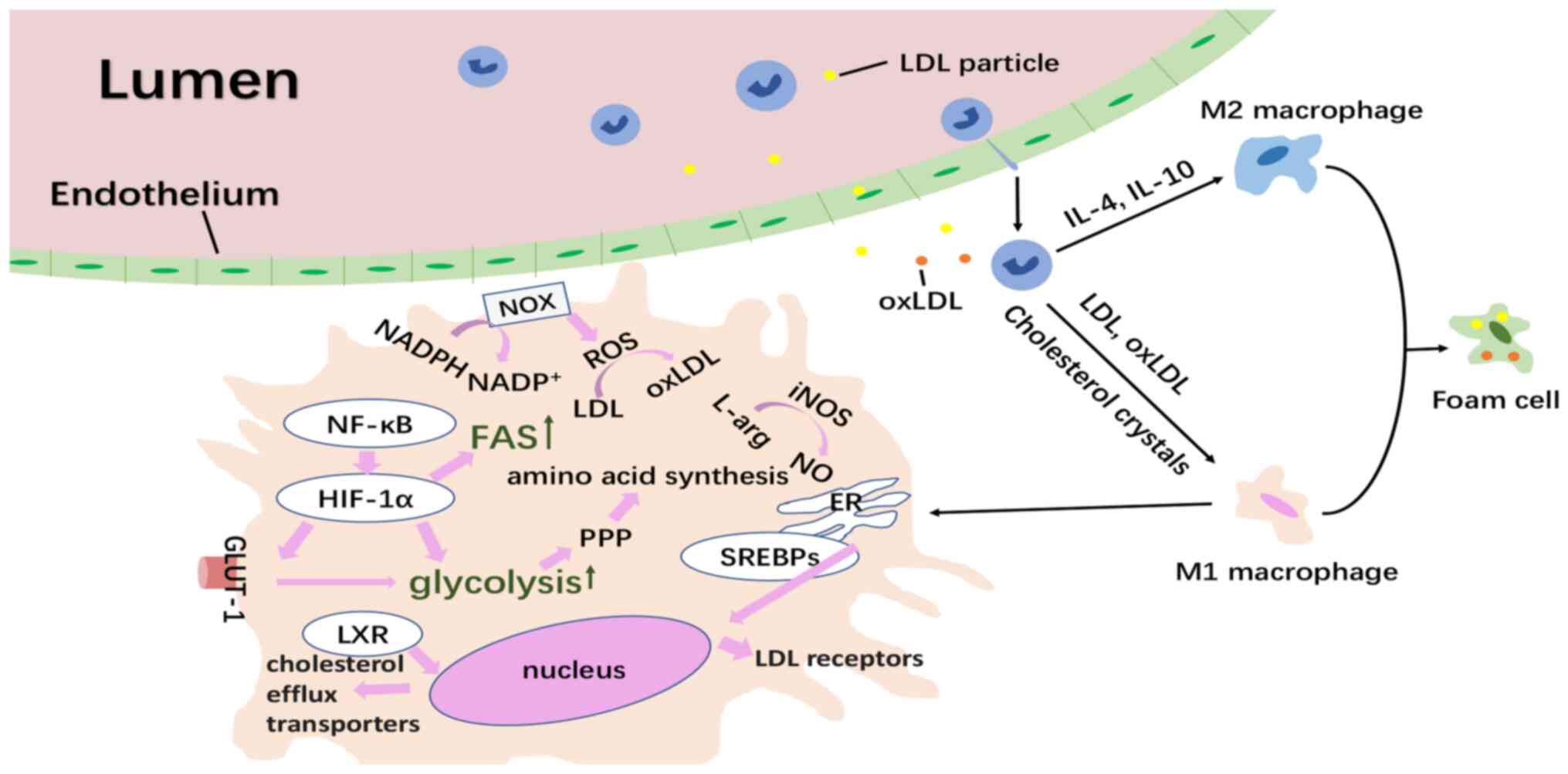

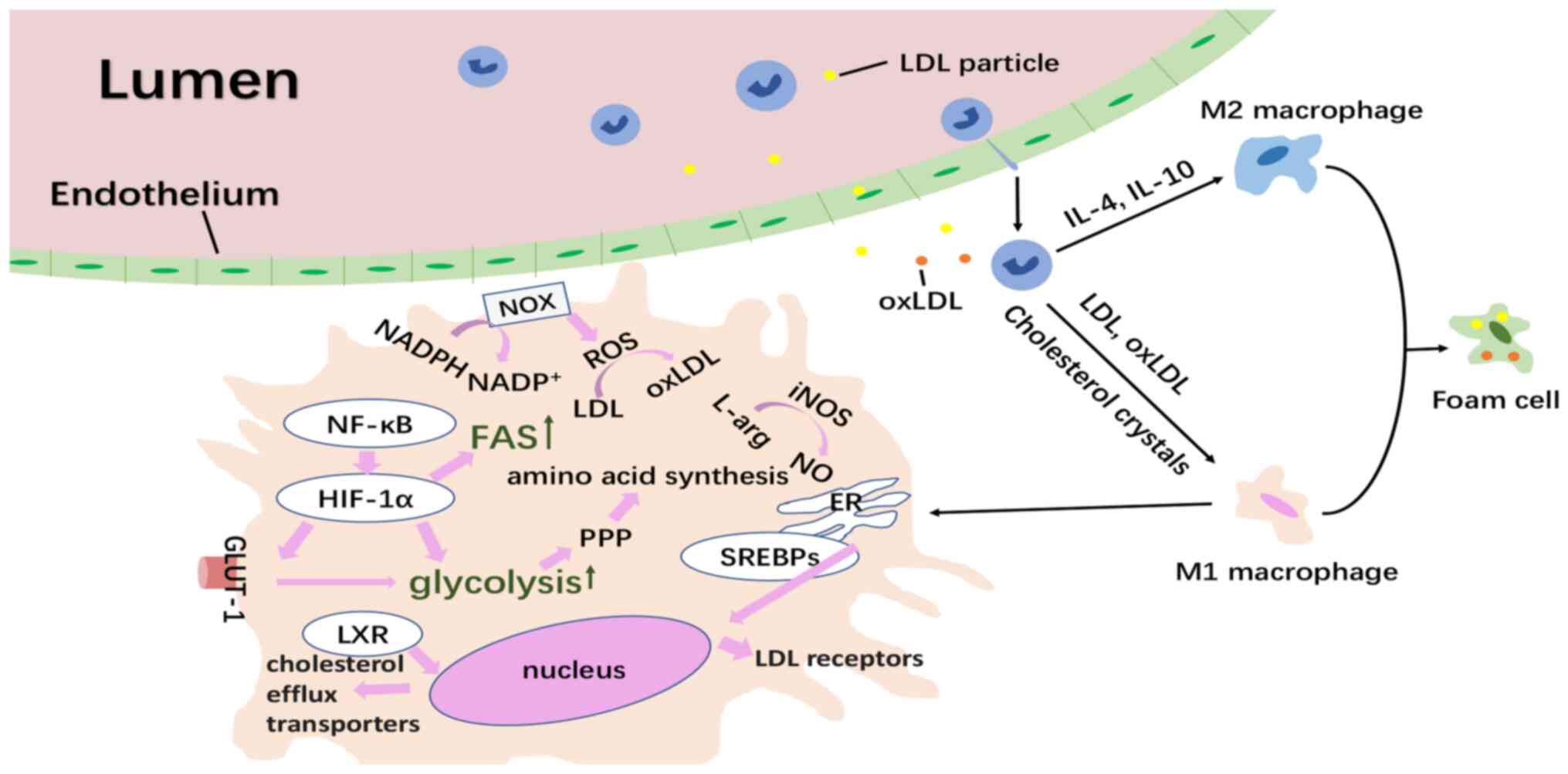

metabolic reprogramming, as will be discussed below (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1.Overview of the formation of trained

macrophages in atherosclerosis and their inner metabolic changes.

LDL deposition in the intima activates endothelial cells to express

a leukocyte adhesion molecule promoting the rolling and adherence

of monocytes. Lipoproteins are modified occasionally and taken in

by recruited monocytes, which then polarize into diverse phenotypes

of macrophages according to their signals from the

microenvironment. Monocytes or macrophages encountering oxLDL

increase the expression of HIF-1α through the NF-κB pathway. The

HIF-1α increases the expression of the GLUT-1, enhancing the uptake

of glucose to support glycolysis, which then accelerates the PPP

for amino acid synthesis. Activated PPP produces NADPH, which can

further act as the electron donor in the production of oxygen

radicals, contributing to oxidative stress. Also, the HIF1-α

stimulates FAS. As for cholesterol metabolism, nuclear receptors

LXR have the ability to reverse cholesterol transport and the SREBP

family located within the ER can migrate into the nucleus and drive

the expression of LDL receptors. The trained pro-inflammatory M1

macrophages synthesize NO from arginine via iNOS. oxLDL, oxidized

low-density lipoprotein; arg, arginine; HIF-1α, hypoxia inducible

factor-1α; SREBP, sterol-regulatory element binding protein; PPP,

pentose phosphate pathway; GLUT1, glucose transporter 1; FAS, fatty

acid synthesis; NF-κB, nuclear factor κ light-chain-enhancer of

activated B cells; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; LXR, liver X

receptors; NOX, NADPH oxidase. |

Glucose metabolism

Monocytes or macrophages encountering

inflammation-induced stimuli such as oxLDL increase the expression

of HIF-1α through signaling pathways, including the nuclear factor

κ light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway. In

addition, hypoxia in regions rich in plaques is also an important

activator of the HIF-1α transcription factor (TF). HIF-1α increases

the expression of the glucose transporter 1 to enhance the uptake

of glucose. Furthermore, the TF initiates glycolytic metabolism, as

well as increases the expression of key glycolytic enzymes, such as

hexokinase II (HK-II) and

6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase (PFKFB3),

resulting in increased glycolytic flux (43). Research has shown that monocytes

from patients with symptomatic AS expressed higher levels of

glycolysis-related genes, including HK-II, PFKFB3 and pyruvate

kinase M (PKM)1 (44).

Though less efficient, the enhancement of glucose

uptake and glycolysis accelerate ATP production and become the

major pathway for energy production (45). In addition, certain relevant

enzymes contribute to the inflammatory states. For instance, PKM2,

shown to be upregulated in pro-inflammatory macrophages,

phosphorylates the TF STAT3, which consequently enhances the

production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and IL-1β (17). Apart from fueling the inflammation

in atherogenesis, glycolysis also accelerates the pentose phosphate

pathway (PPP) to synthesize amino acids needed for the increased

protein, RNA and DNA synthesis burden of trained macrophages. An

observation of only trained macrophages with an activated PPP

(42) suggests that PPP is vital

to the increased cellular dynamics of trained macrophages and takes

part in the inflammatory process of atherogenesis (46). In addition, activated PPP produces

NADPH. NADPH can further act as the electron donor in the

production of oxygen radicals, which contribute to the oxidative

stress within the AS plaque.

The pro-inflammatory macrophages with aerobic

glycolysis also maintain a tricarboxylic acid cycle, despite two

blockades after citrate and succinate leading to the accumulation

of the two metabolites (17,47).

Citrate is crucial for cholesterol and phospholipid synthesis,

leading to the formation of new membranes. As for succinate,

together with α-ketoglutarate, it is critical for the activity of

two families of enzymes controlling epigenetic modifications: The

JMJ family of lysine demethylases and the TET family of

methyl-cytosine hydroxylases (48,49),

mediating the epigenetic reprogramming in innate immune memory.

Succinate is also able to activate HIF-1α and induces IL-1β

production (46), contributing to

the inflammatory states of pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages.

Cholesterol metabolism

A major risk factor for the development of AS is the

high levels of oxLDL within AS plaques, which is taken up by

macrophages, resulting in cholesterol-loaded macrophage foam cells.

Foam cells secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, as

well as produce matrix metalloproteinases to degrade the

extracellular matrix of the plaque, leading to rupture (50,51).

Furthermore, oxLDLs are highly pro-inflammatory and can induce a

trained immune macrophage phenotype, making the control of

cholesterol influx vs. efflux vital for atherogenesis.

This regulation extensively relies on nuclear

receptors liver X receptors (LXRs) including LXR-α and -β.

Activated by oxysterols, LXRs promote reverse cholesterol transport

and have potent anti-inflammatory effects (52). Studies have indicated that LXRs are

able to suppress the expression of inflammatory genes in

macrophages, such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated cultured

macrophages (52–55) and foam cells (56,57).

It has also been reported that LXR agonists are able to reduce AS

plaque formation (50). A recent

study also showed that myeloid LXR deficiency led to a marked

increase in AS with increased monocyte entry, foam-cell formation

and plaque inflammation (58),

marking the importance of LXRs in atherogenesis.

LXRs are also vital to the expression of

sterol-regulatory element binding protein (SREBP)-1c, which is

upregulated in the pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and turns on the

FAS (59). SREBP-1c belongs to the

SREBP family of TFs, which also include SREBP-1a and SREBP-2 and

contribute to the regulation of cholesterol and fatty acid

biosynthetic gene expression (60). The family is located within the

endoplasmic reticulum, where they are retained by cholesterols,

oxysterols and desmosterols. When the intracellular concentration

of these metabolites declines, the SREBPs are released, migrate

into the nucleus and drive the expression of LDL receptors and

genes involved in the synthesis pathway of both cholesterol and

fatty acid (61). Studies have

shown that cholesterol synthesis is upregulated in macrophages

trained with β-glucan or Bacillus Calmette-Guérin, and

β-glucan-induced trained immunity both in vivo and in

vitro can be abrogated by statins inhibiting cholesterol

synthesis (62); however, the role

of cholesterol synthesis in oxLDL-induced trained macrophages

remains to be elucidated.

Lipid metabolism

While glycolysis predominantly energizes the

pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages, FAO is the major source of energy

production in M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages (63,64).

Thanks to the overexpression of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1

transporting long-chain fatty acids into the mitochondria, rates of

FAO are predictably increased, accompanied with decreased

production of inflammatory cytokines in these cells (65).

By contrast, FAS is generally associated with a

pro-inflammatory macrophage phenotype (66). In this pathway, genes involved in

the multi-complex enzyme, such as fatty acid synthase (FASN), are

upregulated (59), and observation

has shown that macrophage-targeted deletion of FASN reduced

AS plaque formation and foam cell formation in Apolipoprotein

E−/− mice (67).

Hypoxia, together with NF-κB, activates the expression of HIF1-α,

which stimulates stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturase (SCD), an important

enzyme in FAS. That way, hypoxia enhances FAS, while suppressing

FAO (68). SCD also drives the

synthesis of monounsaturated fatty acids from palmitic acid.

Increased intracellular levels of unsaturated fatty acids stimulate

a pro-inflammatory phenotype by upregulating IL-1α production in

foam cells (69).

Amino acid metabolism

Another classic example of metabolic reprogramming

is amino acid metabolism, particularly that of arginine. While M2

macrophages catabolize arginine via arginase and finally break it

down into molecules that support cell growth and division, as well

as a building block for collagen production, the trained

pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages synthesize nitric oxide (NO) from

arginine via inducible-NO synthase (iNOS) (70). NO acts not only as a signal of

important cues including vasodilation, insulin secretion and

angiogenesis, but also as an important microbicidal agent, which is

vital for the early stages of AS (71). Enhanced expression of the iNOS has

been used to characterize activated M1 macrophages, and the

expression of iNOS is demonstrated to be elevated compared to

normal arterial tissue by in situ hybridization experiments

(72,73).

Experiments also found that glutamine had pro-AS

effects on a murine macrophage-like cell line (74). Other research has shown the

importance of glutamine in the induction of IL-1 by macrophages in

response to LPS stimulation (75),

highlighting the nonnegligible role of glutamine metabolism in

trained immunity.

Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation in

trained plaque macrophages

In the pathogenesis of AS, the cellular phenotype

and function of macrophages, including differentiation and

activation, are of great importance. The robust execution of this

cascade of biological reactions is guaranteed by multilayered

regulation, such as TF and co-factor binding, the epigenetic

landscape, long-range interactions, DNA methylation, RNA editing

and long non-coding (lnc)RNAs (76). Specifically, in trained macrophages

in AS, studies have found that epigenetic processes, including

histone modification, DNA methylation, modulation of microRNA and

lncRNA expression (8), are at the

basis of the innate immune memory (10,77)

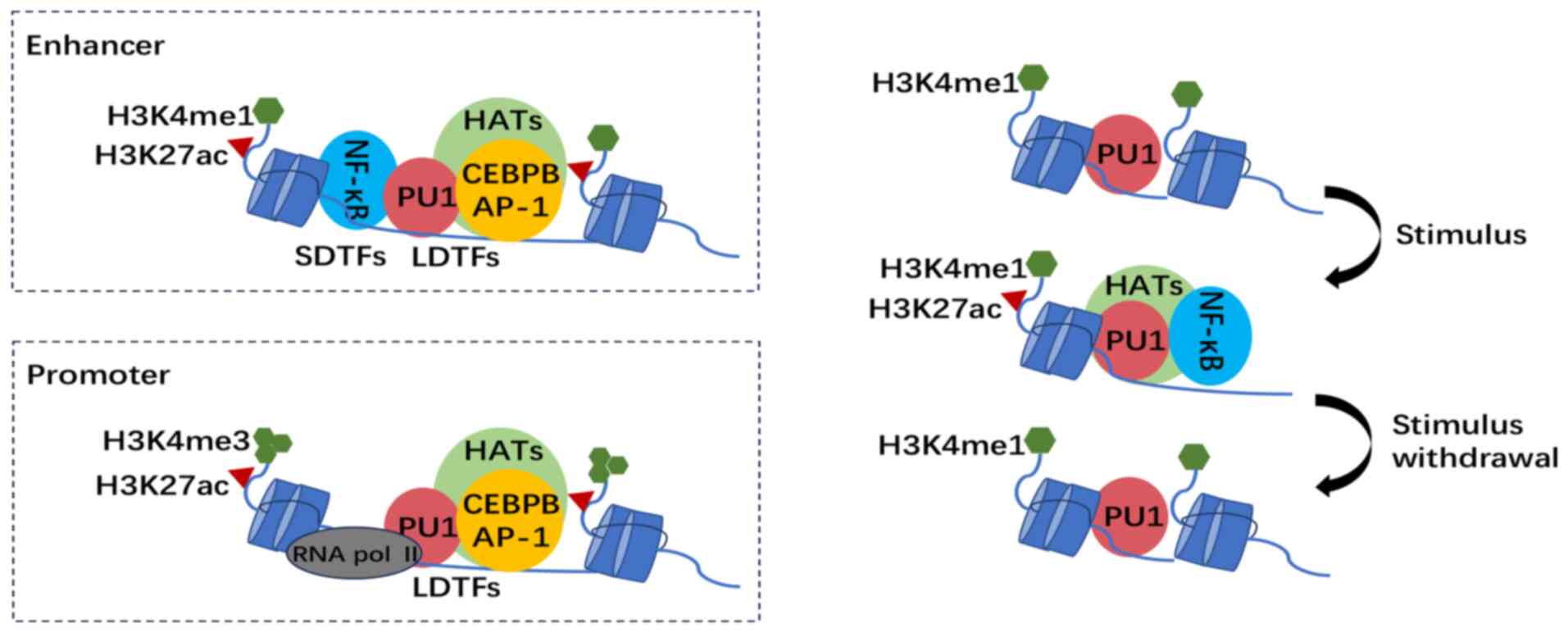

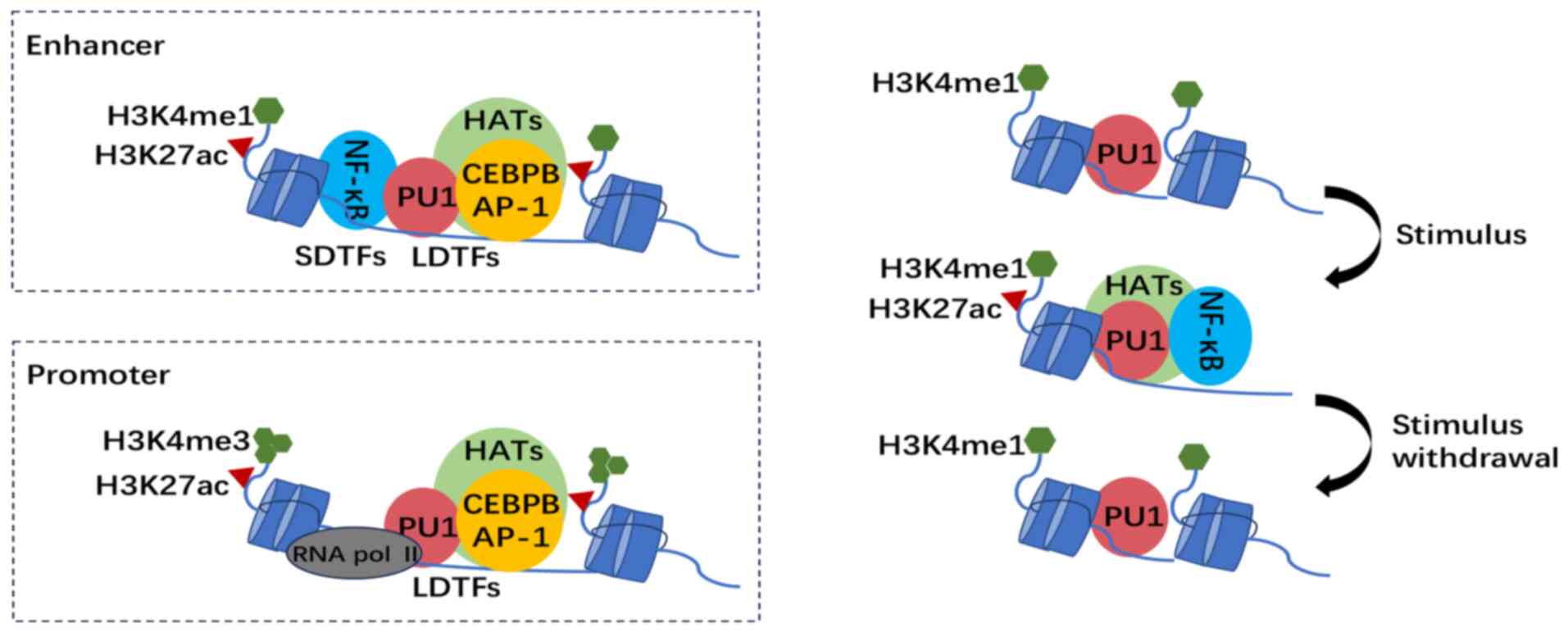

(Fig. 2).

| Figure 2.Epigenetic landscape and

transcription factors binding in trained macrophages. Top left

panel: Distal genetic elements are set up by LDTFs PU-1, CEBPB and

AP-1 via deposition of H3K4me1 by HMEs. Signal-dependent TFs such

as NF-κB recruit histone acetyltransferases, leading to histone

acetylation, including H3K27ac and the formation of active

chromatin. Bottom left panel: H3K4me3 accumulates on immune gene

promoters, where RNA pol II, instead of SDTFs, binds and initiates

gene transcription. Right-hand panel: During myeloid lineage

differentiation, LDTF PU-1 and the accumulation of H3K4me1 prime

the enhancers. Upon stimulation with factors such as oxLDL and

cholesterol crystals, NF-κB binds pre-accessible chromatin and

recruits HATs, leading to histone acetylation such as H3K27ac and

the formation of active chromatin. The SDTF leaves and the H3K27ac

marks are lost gradually after the removal of the initial stimulus,

while H3K4me1 remains, keeping the enhancer in a primed state for

subsequent activation. LDTFs, lineage-determining TFs; HATs,

histone acetyltransferases; CEBPB, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein

beta; AP-1, activator protein 1; H3K27ac, histone 3 lysine 27

acetylation; H3K4me3, histone 3 lysine 4 trimethylation; H3K4me1,

histone 3 lysine 4 methylation; HME, histone-modifying enzyme;

SDTF, signal-dependent TF; PU-1, Spi-1 proto-oncogene; NF-κB,

nuclear factor κ light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; TF,

transcription factor; pol, polymerase. |

Histone modification

Histone-modifying enzymes (HMEs) with

histone-binding domains have the ability to recognize histone tails

extended out of the octamers and catalyze the addition or removal

of different histone modifications. Several modifications, such as

methylation, acetylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination,

together with their role in supporting transcriptional processes,

have been well-studied. Amid a vast repertoire of histone

modifications, acetylation (lysine residues) and methylation

(arginine and lysine residues) are the most broadly studied and

extensively characterized (78).

In the context of a trained immune response,

epigenetic reprogramming takes place in different types of immune

cells at a large number of immune genes and their distal genetic

elements called enhancers. Upon primary stimulation, histone 3

lysine 4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) accumulates on immune gene

promoters, with histone 3 lysine 4 methylation (H3K4me1) on

enhancers and histone 3 lysine 27 acetylation (H3K27ac) marking

active promoters and enhancers (79,80).

H3K27ac marks are gradually lost after removal of the initial

stimulus, while H3K4me1 and H3K4me3 modifications remain (49), suggesting that H3K27ac appears to

function more as a mark of changes in promoter activity than

H3K4me3, and H3K4me1 provides an epigenetic memory function in

macrophages (81).

DNA methylation

CpG islands at promoters and enhancers can be

recognized by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) and are generally

related to transcriptional repression. DNA methylation has been

shown to be more associated with monocyte-to-macrophage

differentiation than subsequent activation (82,83).

Epigenome-wide analyses have demonstrated a general loss of 5mc

during ex vivo monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation

(84). The role of DNA methylation

in trained immunity is still in need of further investigation, and

different combinations of histone and DNA modifications should

determine the accessibility of DNA undoubtedly.

TF binding

TFs usually bind to specific DNA motifs, in

requirement of chromatin accessibility, which is modulated by

epigenetic modification. The macrophage epigenetic and chromatin

accessibility landscape is established by the divergent binding of

lineage-determining TFs (LDTFs) and signal-dependent TFs (SDTFs).

LDTFs act as master regulators of the cell-specific epigenetic

landscape by binding to closed chromatin, setting up a

cell-specific regulatory landscape and driving cell-specific

transcription programs (85).

SDTFs can activate a stimulus-specific regulatory program (86,87)

and can also activate epigenetically unmarked elements termed

latent enhancers, which can remain marked after stimulus removal

and ready for rapid response to a second activation, acting as

cellular memory (81). In the

context of AS, LDTFs such as PU-1 and CCAAT/enhancer binding

protein β (C/EBPβ) instruct macrophage differentiation, while SDTFs

such as NF-κB trigger macrophage activation regulated by cytokine

stimulation (86).

NF-κB, for instance, is in the cytoplasm under basal

conditions. Upon stimulation with substances such as oxLDL or

cholesterol crystals, it translocates to the nucleus (88) and binds pre-accessible chromatin.

Prior to this, classic enhancers are set up by LDTFs PU-1 and

C/EBPβ (89) via deposition of

H3K4me1 by HMEs. Upon binding, NF-κB recruits the histone

acetyltransferase EP300, leading to histone acetylation such as

H3K27ac and formation of active chromatin (90). Subsequently, the translation of

genes such as HIF-1α is permitted and then causes changes in

cellular metabolic and consequent biologic behavior. After removal

of the stimulus, the SDTF leaves, and activating histone marks are

removed under recruitment of histone deacetylases (HDACs), whereas

H3K4me1 remains and keeps the enhancers in a primed state for

subsequent activation.

Besides the above epigenetic and chromatin

accessibility landscape, long-range interactions and ncRNAs are

also found to be critical modulators of macrophage activation. For

instance, an immune gene-priming lncRNA called upstream master

lncRNA of the inflammatory chemokine locus is able to direct

histone methyltransferase to immune-related genes topologically,

leading to increased local H3K4me3, which is a ubiquitous

epigenetic modification in trained immunity (91). The deposition of this mark and its

persistence through the inhibition of histone demethylases provide

specificity for trained immunity (16). Recent findings of epigenetic

mechanisms and metabolic processes from the molecular basis of

trained immunity were summarized in a previous review (92).

In an AS plaque environment, macrophages are exposed

to a variety of signals and differentiate into complex phenotypes

(93). Studies have shown that the

identified pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory macrophage

subsets in the plaque do not resemble the classical M1 and M2

macrophages and express both pro- and anti-inflammatory macrophage

markers at the same time (94).

Indeed, an epigenetic and transcriptional crosstalk between pro-

and anti-inflammatory signaling in macrophages is suggested in

several studies, highlighting the complexity of inflammatory

signaling in an AS plaque in vivo (95,96).

Therapeutic approaches

AS is an inflammation-driven disease and macrophages

have a central role in the modulation of inflammation. Due to the

need to respond in a rapid and specific way, macrophages adopt a

unique, permissive epigenetic landscape that is established and

controlled by sequential binding of LDTFs and SDTFs, which shed

light on therapy targeting epigenetic enzymes. Indeed,

macrophage-specific genetic ablation or pharmacological inhibition

of HMEs holds promise for the treatment of inflammatory diseases

(97). For instance, HDAC3 is able

to deactivate key factors needed for IL-4-dependent

anti-inflammatory activation (98). Macrophage-specific knockout of

HDAC3 in mice promotes plaque stability and steers the cells

into a more wound-healing, fibrotic and anti-inflammatory phenotype

(99). Thus, the deletion of

HDAC3 may attenuate AS. However, owing to the broad action

of epigenetic enzymes, strategies to increase specificity would be

beneficial and possibly even required. There is a great demand to

characterize the epigenetic landscape and pinpoint TFs, as well as

upstream signaling pathways regulating cell type-specific gene

expression programs.

Furthermore, due to the reprogramming of metabolism

in trained macrophages in AS, new drugs interfering with key

metabolic pathways such as glycolysis, which is involved in the

activation and differentiation of monocytes, should be taken into

consideration. Indeed, the observation that trained immunity is

completely prevented by pharmacological blockers of glycolysis

(42) not only validates the

causal role of glycolysis in trained immunity but also enlightens

future treatments of AS. Also, several animal studies have reported

that LXR agonists can reduce AS plaque formation (50), making cholesterol metabolism a key

pathway in AS treatment. For future employment, a targeted therapy

would be required likewise. Also, it may be worthwhile

investigating to what extent the metabolic pathways determine the

destiny of macrophages.

Conclusions

AS, a major threat to global public health, has its

basis in chronic inflammation of the artery wall. Above all cells

involved in atherogenesis, monocytes and macrophages have a major

role in the pathogenesis, highlighting the importance of their

biological activities. Trained immunity, the memory of innate

immunity, has aroused the interest of investigators and may be a

novel mechanism of atherogenesis. In the microenvironment of AS

plaque, monocytes are activated and differentiate into various

phenotypes of macrophages in response to a cascade of signals,

mainly pro-inflammatory M1 and anti-inflammatory M2 cells. During

this process, metabolic changes take place, such as enhanced

glycolysis in trained pro-inflammatory macrophages. Epigenetic and

transcriptional regulation acts as initiators in these metabolic

changes.

Recent discoveries of trained immunity not only

refresh the concept of immunology, but also inspire researchers to

reconsider inflammatory processes in AS. In that way, researchers

find heterogeneity of macrophages in AS plaque and further

elucidate mechanisms that drive the differentiation. To meet the

need for more experiments and findings, research on potential

therapies for AS based on metabolism and gene expression is

underway.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work is supported by grants from the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82273011 and 82072648), the

Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no.

BK20211508) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central

Universities (grant no. 021414380472).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

TL and WF collected the references and were involved

in the initial conception of this review. TL wrote most parts of

the manuscript. TW and WY provided writing guidance and revisions.

All authors have read and approved the final version of the

manuscript. Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Libby P: The changing landscape of

atherosclerosis. Nature. 592:524–533. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Boren J, Chapman MJ, Krauss RM, Packard

CJ, Bentzon JF, Binder CJ, Daemen MJ, Demer LL, Hegele RA, Nicholls

SJ, et al: Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease: Pathophysiological, genetic, and

therapeutic insights: A consensus statement from the european

atherosclerosis society consensus panel. Eur Heart J. 41:2313–2330.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zhu Y, Xian X, Wang Z, Bi Y, Chen Q, Han

X, Tang D and Chen R: Research progress on the relationship between

atherosclerosis and inflammation. Biomolecules. 8:802018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ and Fisher EA:

Macrophages in atherosclerosis: A dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol.

13:709–721. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Netea MG, Quintin J and van der Meer JW:

Trained immunity: A memory for innate host defense. Cell Host

Microbe. 9:355–361. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Netea MG: Training innate immunity: The

changing concept of immunological memory in innate host defence.

Eur J Clin Invest. 43:881–884. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Dominguez-Andres J, Santos JC, Bekkering

S, Mulder WJM, van der Meer JWM, Riksen NP, Joosten LAB and Netea

MG: Trained immunity: Adaptation within innate immune mechanisms.

Physiol Rev. 103:313–346. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Netea MG, Joosten LA, Latz E, Mills KH,

Natoli G, Stunnenberg HG, O'Neill LA and Xavier RJ: Trained

immunity: A program of innate immune memory in health and disease.

Science. 352:aaf10982016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Naik S, Larsen SB, Gomez NC, Alaverdyan K,

Sendoel A, Yuan S, Polak L, Kulukian A, Chai S and Fuchs E:

Inflammatory memory sensitizes skin epithelial stem cells to tissue

damage. Nature. 550:475–480. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

van den Burg HA and Takken FL: Does

chromatin remodeling mark systemic acquired resistance? Trends

Plant Sci. 14:286–294. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Foster SL, Hargreaves DC and Medzhitov R:

Gene-specific control of inflammation by TLR-induced chromatin

modifications. Nature. 447:972–978. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Lim AI, McFadden T, Link VM, Han SJ,

Karlsson RM, Stacy A, Farley TK, Lima-Junior DS, Harrison OJ, Desai

JV, et al: Prenatal maternal infection promotes tissue-specific

immunity and inflammation in offspring. Science. 373:eabf30022021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Li Y, Chen Y, Cai G, Ni Q, Geng Y, Wang T,

Bao C, Ruan X, Wang H and Sun W: Roles of trained immunity in the

pathogenesis of periodontitis. J Periodontal Res. 58:864–873. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wendeln AC, Degenhardt K, Kaurani L,

Gertig M, Ulas T, Jain G, Wagner J, Häsler LM, Wild K, Skodras A,

et al: Innate immune memory in the brain shapes neurological

disease hallmarks. Nature. 556:332–338. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Bekkering S, Quintin J, Joosten LA, van

der Meer JW, Netea MG and Riksen NP: Oxidized low-density

lipoprotein induces long-term proinflammatory cytokine production

and foam cell formation via epigenetic reprogramming of monocytes.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 34:1731–1718. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Riksen NP, Bekkering S, Mulder WJM and

Netea MG: Trained immunity in atherosclerotic cardiovascular

disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 20:799–811. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Shirai T, Nazarewicz RR, Wallis BB, Yanes

RE, Watanabe R, Hilhorst M, Tian L, Harrison DG, Giacomini JC,

Assimes TL, et al: The glycolytic enzyme PKM2 bridges metabolic and

inflammatory dysfunction in coronary artery disease. J Exp Med.

213:337–354. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mitroulis I, Hajishengallis G and Chavakis

T: Bone marrow inflammatory memory in cardiometabolic disease and

inflammatory comorbidities. Cardiovasc Res. 119:2801–2812. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Kleinnijenhuis J, Quintin J, Preijers F,

Joosten LA, Jacobs C, Xavier RJ, van der Meer JW, van Crevel R and

Netea MG: BCG-induced trained immunity in NK cells: Role for

non-specific protection to infection. Clin Immunol. 155:213–219.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Moorlag SJCFM, Rodriguez-Rosales YA,

Gillard J, Fanucchi S, Theunissen K, Novakovic B, de Bont CM,

Negishi Y, Fok ET, Kalafati L, et al: BCG vaccination induces

long-term functional reprogramming of human neutrophils. Cell Rep.

33:1083872020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Hole CR, Wager CML, Castro-Lopez N,

Campuzano A, Cai H, Wozniak KL, Wang Y and Wormley FL Jr: Induction

of memory-like dendritic cell responses in vivo. Nat Commun.

10:29552019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Sohrabi Y, Lagache SMM, Voges VC, Semo D,

Sonntag G, Hanemann I, Kahles F, Waltenberger J and Findeisen HM:

OxLDL-mediated immunologic memory in endothelial cells. J Mol Cell

Cardiol. 146:121–132. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Netea MG, Domínguez-Andrés J, Barreiro LB,

Chavakis T, Divangahi M, Fuchs E, Joosten LAB, van der Meer JWM,

Mhlanga MM, Mulder WJM, et al: Defining trained immunity and its

role in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 20:375–388. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Bonetti J, Corti A, Lerouge L, Pompella A

and Gaucher C: Phenotypic modulation of macrophages and vascular

smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis-nitro-redox

interconnections. Antioxidants (Basel). 10:5162021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Gordon S and Taylor PR: Monocyte and

macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 5:953–964. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Duewell P, Kono H, Rayner KJ, Sirois CM,

Vladimer G, Bauernfeind FG, Abela GS, Franchi L, Nuñez G, Schnurr

M, et al: NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and

activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature. 464:1357–1361. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Chavez-Sanchez L, Garza-Reyes MG,

Espinosa-Luna JE, Chávez-Rueda K, Legorreta-Haquet MV and

Blanco-Favela F: The role of TLR2, TLR4 and CD36 in macrophage

activation and foam cell formation in response to oxLDL in humans.

Hum Immunol. 75:322–329. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Hirose K, Iwabuchi K, Shimada K, Kiyanagi

T, Iwahara C, Nakayama H and Daida H: Different responses to

oxidized low-density lipoproteins in human polarized macrophages.

Lipids Health Dis. 10:12011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Verreck FA, de Boer T, Langenberg DM,

Hoeve MA, Kramer M, Vaisberg E, Kastelein R, Kolk A, de

Waal-Malefyt R and Ottenhoff TH: Human IL-23-producing type 1

macrophages promote but IL-10-producing type 2 macrophages subvert

immunity to (myco)bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 101:4560–4565.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Stein M, Keshav S, Harris N and Gordon S:

Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor

activity: A marker of alternative immunologic macrophage

activation. J Exp Med. 176:287–292. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Gordon S: Alternative activation of

macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 3:23–35. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mosser DM and Edwards JP: Exploring the

full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nat Rev Immunol. 8:958–969.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Jinnouchi H, Guo L, Sakamoto A, Torii S,

Sato Y, Cornelissen A, Kuntz S, Paek KH, Fernandez R, Fuller D, et

al: Diversity of macrophage phenotypes and responses in

atherosclerosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 77:1919–1932. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Chinetti-Gbaguidi G, Colin S and Staels B:

Macrophage subsets in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 12:10–17.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kadl A, Meher AK, Sharma PR, Lee MY, Doran

AC, Johnstone SR, Elliott MR, Gruber F, Han J, Chen W, et al:

Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in

response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ Res.

107:737–746. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Stoger JL, Gijbels MJ, van der Velden S,

Manca M, van der Loos CM, Biessen EA, Daemen MJ, Lutgens E and de

Winther MP: Distribution of macrophage polarization markers in

human atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 225:461–468. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Stewart CR, Stuart LM, Wilkinson K, van

Gils JM, Deng J, Halle A, Rayner KJ, Boyer L, Zhong R, Frazier WA,

et al: CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly

of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat Immunol.

11:155–161. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Feig JE, Vengrenyuk Y, Reiser V, Wu C,

Statnikov A, Aliferis CF, Garabedian MJ, Fisher EA and Puig O:

Regression of atherosclerosis is characterized by broad changes in

the plaque macrophage transcriptome. PLoS One. 7:e397902012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

O'Neill LA, Kishton RJ and Rathmell J: A

guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol.

16:553–565. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Stienstra R, Netea-Maier RT, Riksen NP,

Joosten LAB and Netea MG: Specific and complex reprogramming of

cellular metabolism in myeloid cells during innate immune

responses. Cell Metab. 26:142–156. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Groh L, Keating ST, Joosten LAB, Netea MG

and Riksen NP: Monocyte and macrophage immunometabolism in

atherosclerosis. Semin Immunopathol. 40:203–214. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Cheng SC, Quintin J, Cramer RA, Shepardson

KM, Saeed S, Kumar V, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Martens JH, Rao

NA, Aghajanirefah A, et al: mTOR- and HIF-1α-mediated aerobic

glycolysis as metabolic basis for trained immunity. Science.

345:12506842014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Tawakol A, Singh P, Mojena M,

Pimentel-Santillana M, Emami H, MacNabb M, Rudd JH, Narula J,

Enriquez JA, Través PG, et al: HIF-1α and PFKFB3 mediate a tight

relationship between proinflammatory activation and anerobic

metabolism in atherosclerotic macrophages. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc

Biol. 35:1463–1471. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Bekkering S, van den Munckhof I, Nielen T,

Lamfers E, Dinarello C, Rutten J, de Graaf J, Joosten LA, Netea MG,

Gomes ME and Riksen NP: Innate immune cell activation and

epigenetic remodeling in symptomatic and asymptomatic

atherosclerosis in humans in vivo. Atherosclerosis. 254:228–236.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Riksen NP and Netea MG: Immunometabolic

control of trained immunity. Mol Aspects Med. 77:1008972021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Tannahill GM, Curtis AM, Adamik J,

Palsson-McDermott EM, McGettrick AF, Goel G, Frezza C, Bernard NJ,

Kelly B, Foley NH, et al: Succinate is an inflammatory signal that

induces IL-1β through HIF-1α. Nature. 496:238–242. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Jha AK, Huang SC, Sergushichev A,

Lampropoulou V, Ivanova Y, Loginicheva E, Chmielewski K, Stewart

KM, Ashall J, Everts B, et al: Network integration of parallel

metabolic and transcriptional data reveals metabolic modules that

regulate macrophage polarization. Immunity. 42:419–430. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Benit P, Letouzé E, Rak M, Aubry L,

Burnichon N, Favier J, Gimenez-Roqueplo AP and Rustin P:

Unsuspected task for an old team: Succinate, fumarate and other

Krebs cycle acids in metabolic remodeling. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1837:1330–1337. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Saeed S, Quintin J, Kerstens HH, Rao NA,

Aghajanirefah A, Matarese F, Cheng SC, Ratter J, Berentsen K, van

der Ent MA, et al: Epigenetic programming of monocyte-to-macrophage

differentiation and trained innate immunity. Science.

345:12510862014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Tall AR and Yvan-Charvet L: Cholesterol,

inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 15:104–116.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Khokha R, Murthy A and Weiss A:

Metalloproteinases and their natural inhibitors in inflammation and

immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 13:649–665. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Ito A, Hong C, Rong X, Zhu X, Tarling EJ,

Hedde PN, Gratton E, Parks J and Tontonoz P: LXRs link metabolism

to inflammation through Abca1-dependent regulation of membrane

composition and TLR signaling. Elife. 4:e080092015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Thomas DG, Doran AC, Fotakis P, Westerterp

M, Antonson P, Jiang H, Jiang XC, Gustafsson JÅ, Tabas I and Tall

AR: LXR suppresses inflammatory gene expression and neutrophil

migration through cis-repression and cholesterol efflux. Cell Rep.

25:3774–3785. e42018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Ghisletti S, Huang W, Ogawa S, Pascual G,

Lin ME, Willson TM, Rosenfeld MG and Glass CK: Parallel

SUMOylation-dependent pathways mediate gene- and signal-specific

transrepression by LXRs and PPARgamma. Mol Cell. 25:57–70. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Bories G, Colin S, Vanhoutte J, Derudas B,

Copin C, Fanchon M, Daoudi M, Belloy L, Haulon S, Zawadzki C, et

al: Liver X receptor activation stimulates iron export in human

alternative macrophages. Circ Res. 113:1196–1205. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Spann NJ, Garmire LX, McDonald JG, Myers

DS, Milne SB, Shibata N, Reichart D, Fox JN, Shaked I, Heudobler D,

et al: Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage

lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 151:138–152.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Zhang X, McDonald JG, Aryal B,

Canfrán-Duque A, Goldberg EL, Araldi E, Ding W, Fan Y, Thompson BM,

Singh AK, et al: Desmosterol suppresses macrophage inflammasome

activation and protects against vascular inflammation and

atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 118:e21076821182021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Endo-Umeda K, Kim E, Thomas DG, Liu W, Dou

H, Yalcinkaya M, Abramowicz S, Xiao T, Antonson P, Gustafsson JÅ,

et al: Myeloid LXR (Liver X Receptor) deficiency induces

inflammatory gene expression in foamy macrophages and accelerates

atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 42:719–731. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Ecker J, Liebisch G, Englmaier M, Grandl

M, Robenek H and Schmitz G: Induction of fatty acid synthesis is a

key requirement for phagocytic differentiation of human monocytes.

Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:7817–7822. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Rong S, Cortés VA, Rashid S, Anderson NN,

McDonald JG, Liang G, Moon YA, Hammer RE and Horton JD: Expression

of SREBP-1c requires SREBP-2-mediated generation of a sterol ligand

for LXR in livers of mice. Elife. 6:e250152017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Im SS, Yousef L, Blaschitz C, Liu JZ,

Edwards RA, Young SG, Raffatellu M and Osborne TF: Linking lipid

metabolism to the innate immune response in macrophages through

sterol regulatory element binding protein-1a. Cell Metab.

13:540–549. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Arts RJ, Novakovic B, Horst RT, Carvalho

A, Bekkering S, Lachmandas E, Rodrigues F, Silvestre R, Cheng SC,

Wang SY, et al: Glutaminolysis and fumarate accumulation integrate

immunometabolic and epigenetic programs in trained immunity. Cell

Metab. 24:807–819. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O'Sullivan

D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY,

O'Neill CM, et al: Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential

for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol. 15:846–855.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Van den Bossche J, O'Neill LA and Menon D:

Macrophage immunometabolism: Where are we (Going)? Trends Immunol.

38:395–406. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Malandrino MI, Fucho R, Weber M,

Calderon-Dominguez M, Mir JF, Valcarcel L, Escoté X, Gómez-Serrano

M, Peral B, Salvadó L, et al: Enhanced fatty acid oxidation in

adipocytes and macrophages reduces lipid-induced triglyceride

accumulation and inflammation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab.

308:E756–E769. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Feingold KR, Shigenaga JK, Kazemi MR,

McDonald CM, Patzek SM, Cross AS, Moser A and Grunfeld C:

Mechanisms of triglyceride accumulation in activated macrophages. J

Leukoc Biol. 92:829–839. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Schneider JG, Yang Z, Chakravarthy MV,

Lodhi IJ, Wei X, Turk J and Semenkovich CF: Macrophage fatty-acid

synthase deficiency decreases diet-induced atherosclerosis. J Biol

Chem. 285:23398–23409. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Bostrom P, Magnusson B, Svensson PA,

Wiklund O, Borén J, Carlsson LM, Ståhlman M, Olofsson SO and Hultén

LM: Hypoxia converts human macrophages into triglyceride-loaded

foam cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 26:1871–1876. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Freigang S, Ampenberger F, Weiss A,

Kanneganti TD, Iwakura Y, Hersberger M and Kopf M: Fatty

acid-induced mitochondrial uncoupling elicits

inflammasome-independent IL-1α and sterile vascular inflammation in

atherosclerosis. Nat Immunol. 14:1045–1053. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Rath M, Müller I, Kropf P, Closs EI and

Munder M: Metabolism via Arginase or nitric oxide synthase: Two

competing arginine pathways in macrophages. Front Immunol.

5:5322014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Napoli C, de Nigris F, Williams-Ignarro S,

Pignalosa O, Sica V and Ignarro LJ: Nitric oxide and

atherosclerosis: An update. Nitric Oxide. 15:265–279. 2006.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Luoma JS and Yla-Herttuala S: Expression

of inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages and smooth muscle

cells in various types of human atherosclerotic lesions. Virchows

Arch. 434:561–568. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Esaki T, Hayashi T, Muto E, Yamada K,

Kuzuya M and Iguchi A: Expression of inducible nitric oxide

synthase in T lymphocytes and macrophages of cholesterol-fed

rabbits. Atherosclerosis. 128:39–46. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Rom O, Grajeda-Iglesias C, Najjar M,

Abu-Saleh N, Volkova N, Dar DE, Hayek T and Aviram M:

Atherogenicity of amino acids in the lipid-laden macrophage model

system in vitro and in atherosclerotic mice: A key role for

triglyceride metabolism. J Nutr Biochem. 45:24–38. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Wallace C and Keast D: Glutamine and

macrophage function. Metabolism. 41:1016–1020. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Kuznetsova T, Prange KHM, Glass CK and de

Winther MPJ: Transcriptional and epigenetic regulation of

macrophages in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 17:216–228. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Conrath U: Molecular aspects of defence

priming. Trends Plant Sci. 16:524–531. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

van der Heijden C, Noz MP, Joosten LAB,

Netea MG, Riksen NP and Keating ST: Epigenetics and trained

immunity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 29:1023–1040. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD,

Kheradpour P, Stark A, Harp LF, Ye Z, Lee LK, Stuart RK, Ching CW,

et al: Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global

cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. 459:108–112. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Rada-Iglesias A, Bajpai R, Swigut T,

Brugmann SA, Flynn RA and Wysocka J: A unique chromatin signature

uncovers early developmental enhancers in humans. Nature.

470:279–283. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Ostuni R, Piccolo V, Barozzi I, Polletti

S, Termanini A, Bonifacio S, Curina A, Prosperini E, Ghisletti S

and Natoli G: Latent enhancers activated by stimulation in

differentiated cells. Cell. 152:157–171. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Vento-Tormo R, Company C, Rodríguez-Ubreva

J, de la Rica L, Urquiza JM, Javierre BM, Sabarinathan R, Luque A,

Esteller M, Aran JM, et al: IL-4 orchestrates STAT6-mediated DNA

demethylation leading to dendritic cell differentiation. Genome

Biol. 17:42016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Dekkers KF, Neele AE, Jukema JW, Heijmans

BT and de Winther MPJ: Human monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation

involves highly localized gain and loss of DNA methylation at

transcription factor binding sites. Epigenetics Chromatin.

12:342019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Novakovic B, Habibi E, Wang SY, Arts RJW,

Davar R, Megchelenbrink W, Kim B, Kuznetsova T, Kox M, Zwaag J, et

al: β-glucan reverses the epigenetic state of LPS-induced

immunological tolerance. Cell. 167:1354–1368. e142016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Zaret KS and Mango SE: Pioneer

transcription factors, chromatin dynamics, and cell fate control.

Curr Opin Genet Dev. 37:76–81. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Glass CK and Natoli G: Molecular control

of activation and priming in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 17:26–33.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Schmidt SV, Krebs W, Ulas T, Xue J, Baßler

K, Günther P, Hardt AL, Schultze H, Sander J, Klee K, et al: The

transcriptional regulator network of human inflammatory macrophages

is defined by open chromatin. Cell Res. 26:151–170. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D and Sun SC: NF-κB

signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther.

2:170232017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, Bertolino E,

Lin YC, Laslo P, Cheng JX, Murre C, Singh H and Glass CK: Simple

combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime

cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell

identities. Mol Cell. 38:576–589. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Ghisletti S, Barozzi I, Mietton F,

Polletti S, De Santa F, Venturini E, Gregory L, Lonie L, Chew A,

Wei CL, et al: Identification and characterization of enhancers

controlling the inflammatory gene expression program in

macrophages. Immunity. 32:317–328. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Fanucchi S, Fok ET, Dalla E, Shibayama Y,

Börner K, Chang EY, Stoychev S, Imakaev M, Grimm D, Wang KC, et al:

Immune genes are primed for robust transcription by proximal long

noncoding RNAs located in nuclear compartments. Nat Genet.

51:138–150. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Fanucchi S, Domínguez-Andrés J, Joosten

LAB, Netea MG and Mhlanga MM: The intersection of epigenetics and

metabolism in trained immunity. Immunity. 54:32–43. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Colin S, Chinetti-Gbaguidi G and Staels B:

Macrophage phenotypes in atherosclerosis. Immunol Rev. 262:153–166.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Arampatzi P,

Pelisek J, Winkels H, Ley K, Wolf D, Saliba AE and Zernecke A:

Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the transcriptional landscape and

heterogeneity of aortic macrophages in murine atherosclerosis. Circ

Res. 122:1661–1674. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Piccolo V, Curina A, Genua M, Ghisletti S,

Simonatto M, Sabò A, Amati B, Ostuni R and Natoli G: Opposing

macrophage polarization programs show extensive epigenomic and

transcriptional cross-talk. Nat Immunol. 18:530–540. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Czimmerer Z, Daniel B, Horvath A, Rückerl

D, Nagy G, Kiss M, Peloquin M, Budai MM, Cuaranta-Monroy I, Simandi

Z, et al: The transcription factor STAT6 mediates direct repression

of inflammatory enhancers and limits activation of alternatively

polarized macrophages. Immunity. 48:75–90. e62018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Neele AE, Van den Bossche J, Hoeksema MA

and de Winther MP: Epigenetic pathways in macrophages emerge as

novel targets in atherosclerosis. Eur J Pharmacol. 763:79–89. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Mullican SE, Gaddis CA, Alenghat T, Nair

MG, Giacomin PR, Everett LJ, Feng D, Steger DJ, Schug J, Artis D

and Lazar MA: Histone deacetylase 3 is an epigenomic brake in

macrophage alternative activation. Genes Dev. 25:2480–2488. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Hoeksema MA, Gijbels MJ, Van den Bossche

J, van der Velden S, Sijm A, Neele AE, Seijkens T, Stöger JL,

Meiler S, Boshuizen MC, et al: Targeting macrophage Histone

deacetylase 3 stabilizes atherosclerotic lesions. EMBO Mol Med.

6:1124–1132. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Chistiakov DA, Kashirskikh DA, Khotina VA,

Grechko AV and Orekhov AN: Immune-inflammatory responses in

atherosclerosis: The role of myeloid cells. J Clin Med. 8:17982019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|