Infectious diseases remain one of the top ten causes

of human morbidity and mortality worldwide (1). Pathogen identification from clinical

samples is key to guide treatment and management strategies for

patients with infections. Currently, a number of traditional

diagnostic techniques are used for etiological diagnosis, including

microbial culture, antigen and antibody testing and PCR of

microbial DNA or RNA (2). However,

in ~50% of infected patients there are difficulties in pathogen

identification due to the wide variety of pathogens, low throughput

of traditional clinical methods and time-consuming nature of

microbial culture (3).

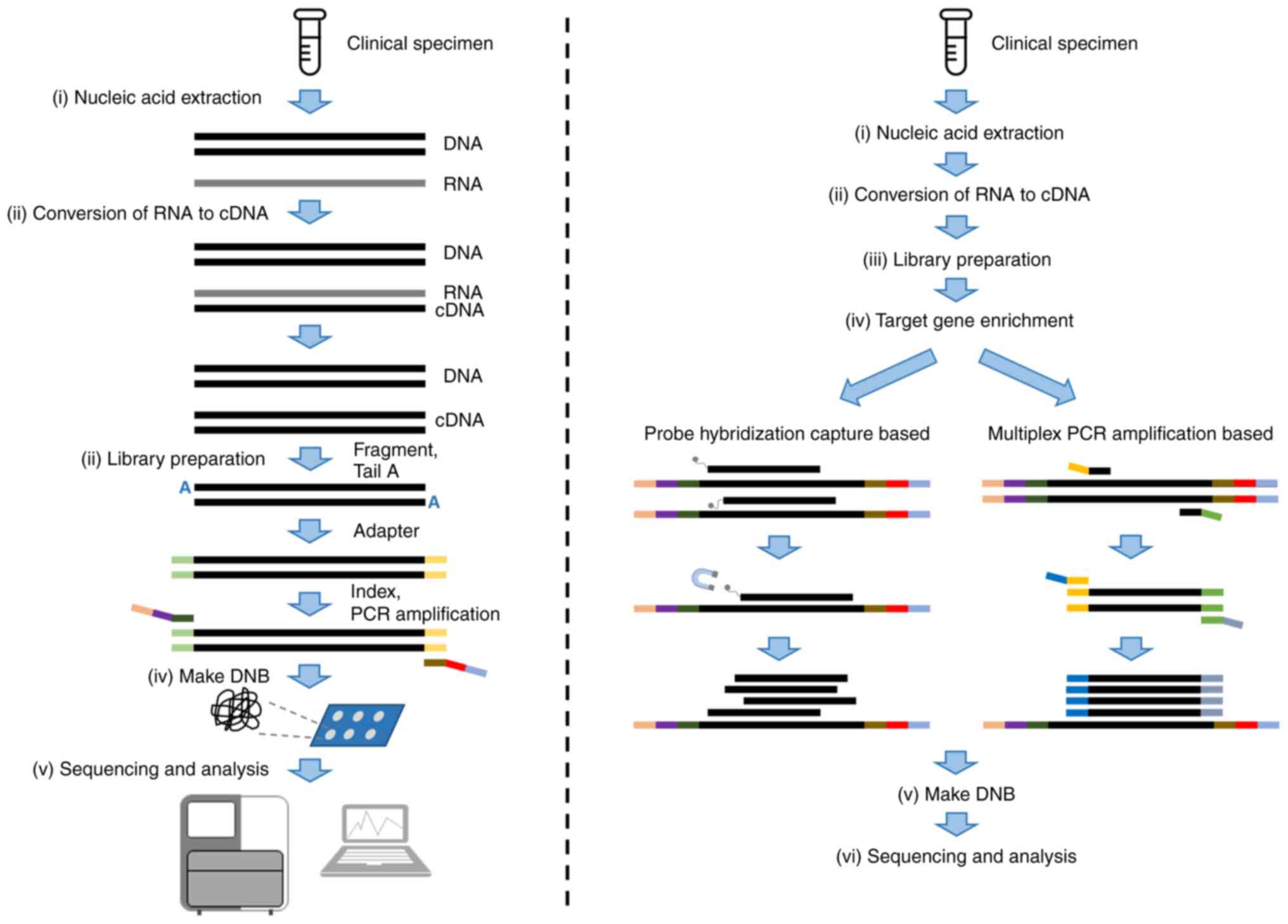

Assays using next-generation sequencing (NGS)

technology have potential to improve diagnosis of infectious

diseases. NGS allows for sequencing of multiple individual DNA or

RNA molecules in parallel, generating millions to billions of reads

per run. The common applications of NGS in diagnostic microbiology

laboratories include metagenomics NGS (mNGS) and targeted NGS

(tNGS; Fig. 1). mNGS approaches

characterize all DNA or RNA in a sample to enable analysis of the

entire microbiome, whereas tNGS approaches enrich specific genetic

targets to identify specific pathogens or genes of interest. Given

the success of the clinical exploration of mNGS, attention has been

focused on making NGS more widely and economically available in the

clinical setting. The use of tNGS as a solution for this is also

being assessed. The present review aimed to elucidate the

diagnostic value of tNGS in clinical application.

As a successful example of the clinical application

of NGS methods, previous studies have reported the promise of mNGS

in clinical application (4–14).

mNGS successfully diagnosed neuroleptospirosis in a 14-year-old,

which put the application of mNGS in the diagnosis of infectious

diseases into the public light (4). In 2019, Blauwkamp et al

(5) described the commercial mNGS

sequencing Karius test (Karius, Inc.) in a cohort of 350 patients

with suspected sepsis. It presented sensitivity of 92.9% and a

specificity of 62.7% compared with the composite reference standard

including culture, serology and nucleic acid testing and clinical

adjudication when testing the plasma specimens from this cohort

(5). Studies have confirmed the

diagnostic value of mNGS in a number of patient cohorts assessing

complex and atypical pathogen infection, including meningitis and

pneumonia (3,6–9).

mNGS is a potential method for identifying emerging or rare

pathogens. For example, RNA-based mNGS identified the novel

coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

(SARS-CoV-2) as the cause of severe pneumonia (10). mNGS could provide clues for

identifying rare pathogens including Chlamydia psittaci,

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), anaerobe and fungus (11–13).

Moreover, sensitivity of mNGS is relatively less affected by prior

antibiotics therapy compared to methods such as clinical cultures

and immunologic assays. A previous study reported the sensitivity

of mNGS is significantly higher than that of culture (52.7 vs.

34.4%) when patients had received prior antibiotic therapy

(12). This conclusion was

supported by Zhang et al (14), who found a higher sensitivity rate

(66.67%) of mNGS in empirically-treated patients.

However, with widespread clinical use, shortcomings

of mNGS have also received attention. The first problem is

over-representation of human DNA in sequence data. As samples

contain large amounts of human nucleic acid and the human genome is

notably larger than the microbial genome, 80–99% of raw NGS reads

are derived from human DNA (7,15),

which decreases sensitivity of assays for microbial detection,

especially when these are present in low abundance. Techniques for

depleting host nucleic acid include physical methods such as

centrifugation and filtration (16,17),

chemical methods, including differential cleavage with chemical

reagents (18), and selective

hybridization removal using clustered regularly interspaced short

palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated systems 9 (19) (Table

I). However, these methods introduce new problems. Partial

pathogens will be lost by these methods (20) and the risk of exogenous background

contamination increases due to the addition of reagents. The

complexity of these issues increases the difficulty of host nucleic

acid depletion. At present, there is no relatively achievable

method (20).

The detection performance of mNGS can be affected by

the characteristics of pathogens. Small-genome, low-abundance

pathogens such as viruses have limited coverage. A study assessing

mNGS virus detection reported that median viral genome coverage is

~2% (21,22). In addition, antimicrobial

resistance genes and virulence genes are also short in length,

again a challenge for mNGS detection (23). Furthermore, the application of mNGS

in fungal detection is limited. Pathogens with cell walls including

fungi and intracellular bacteria affect nucleic acid extraction

efficiency, which reduces the microbial nucleic acid abundance in

sample (6,9,15,24–27).

Besides, the high cost of mNGS limits its broader adoption in

clinical settings. In China, the average cost per mNGS test is

¥3,000 (~US$400), which is significantly more expensive than

individual traditional pathogen tests. For instance, culture tests

cost around ¥600-700, the Cryptococcus antigen test is ¥320,

and both the Aspergillus serological test and T-cell

immunospot test T.SPOT are priced at ~¥600 (12).

tNGS is an NGS method that detects a predetermined

range of target genes. tNGS has been widely applied in disease

identification including tumor detection, whereas studies assessing

its use in pathogen detection are limited. Compared with mNGS, tNGS

extracts predefined genes through enrichment, which allows

pathogens to be targeted for sequencing. Targeted approaches are

used to enrich known pathogens, especially low-concentration

pathogens and their virulence and/or antimicrobial resistance genes

in a single sample. This can increase the detection sensitivity for

microorganisms being targeted, although it limits the breadth of

potential pathogens that can be identified. Target enrichment is

key to ensure sufficient sequencing depth and coverage in the

regions of interest in tNGS workflow for accurate pathogen

identification. Compared with mNGS, tNGS can enrich microbial

nucleic acid content by several 10-fold to several 1,000-fold

(28).

Multiplex PCR amplicon-based and hybrid

capture-based methodologies are used for target enrichment in tNGS.

The multiplex PCR amplicon-based method amplifies and enriches

target fragments through multiple primers designed for target

region fragments. Multiple target fragments are amplified at the

same time for library construction and sequencing. Hybrid-capture

targeted method uses probes which hybridize with target fragments

to capture and enrich target regions. Hybrid capture-based assays

use magnetic beads to purify captured fragments to remove

non-specific hybridization and constructs a DNA library for

sequencing. The main differences between the approaches are shown

in Table II.

The advantages of the amplicon-based method are low

cost and quick and simple operation. The amplicon-based method can

detect pathogens with low concentration. A study assessing the

corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) detection ability of these

methods reported that amplicon- and hybrid probe-based methods

generally have the same enrichment effect on target gene fragments,

but the amplicon-based method has a better enrichment effect for

lower concentration viruses <1×104 copies/ml or

Ct>28.7 (29). Moreover, the

specificity of the amplicon-based method is better according to the

stringency of the primer binding to the target region. Therefore,

this method more efficiently detects single nucleotide variations.

However, the fact that it has undergone PCR amplification makes it

difficult to quantify, which may result in poor performance in

detecting copy number and structural variation (29).

There are limitations for amplicon-based assay in

applications. Firstly, the amplicon-based method has limitations

for the detection spectrum. To avoid dimerization between primers,

only ~20,000 primers can be designed. Considering the specificity

of pathogens, the melting temperature value and the secondary

structure of primers, this number will be greatly reduced. This

upper limit of the number of primers increases the difficulty of

adjusting design of primers, which affects the flexibility of

pathogen detection in the face of novel pathogens and different

environments. Secondly, the amplicon-based method has a low

tolerance for primer mismatch. This method requires almost 100%

match between the primers and target sequence, rendering the

amplification ineffective if mutations are present in the primer

binding region. Thirdly, the amplicon-based method, used for

sequencing SARS-CoV-2 genomes directly from clinical samples, has

limitations in detecting minor alleles. Specifically, this method

introduces biases that affect the accuracy of detecting the

frequency of these minor alleles. Additionally, it has a

significantly higher false-positive rate compared to the hybrid

capture-based method (0.74 vs. 0.02%). This means that the

amplicon-based method is less reliable and more prone to errors

when identifying less prevalent genetic variations within the viral

genome (29).

The hybrid capture-based method is able to detect a

wider range of pathogens with more comprehensive genome coverage

and more flexible pathogen detection design. The number of species

detected by hybrid capture can be several 1,000. In the context of

pandemics including COVID-19 and influenza A that require analysis

of genome variation and virus monitoring and traceability, the

whole genome can be covered by the hybrid capture-based method. The

hybrid capture-based method can combine new pathogen-specific

probes without affecting performance. Furthermore, hybrid

capture-based method has high tolerance for primer mismatch making

it more suitable for use in samples with a high occurrence of

mutations. Unlike the amplicon-based method, the hybrid

capture-based method is able to amplify the target region with a

matching accuracy of 70–80% (30).

A genome sequencing study of hepatitis C virus (HCV) reported that

the hybrid capture-based method can achieve the maximum capture

efficiency of HCV at 80% probe matching (31). Furthermore, the hybrid

capture-based method is less likely to capture identical nucleic

acid fragments due to technical principles and therefore has a

better uniformity. A previous study reported that the hybrid

capture-based method has better uniformity and less bias than the

amplicon-based method and may reflect the true content of pathogens

in samples more objectively (29).

According to our experience, the hybrid

capture-based method requires a higher initial concentration of

pathogens and extracted DNA and cDNA need to be fragmented prior to

probe hybridization capture. During fragmentation, loss of DNA and

cDNA is possible. Furthermore, the probes may partially hybridize

and capture non-specific fragments. IN addition, poor design of

capture probes, suboptimal capture conditions, insufficient

blocking of repetitive sequences in genomic DNA and improper ratio

of genomic DNA to capture probe can affect capture specificity.

Compared with the amplicon-based method, the hybrid capture-based

method is more complicated, has a higher cost and longer workflow

time. The time required for a typical probe hybridization capture

process is ~12 h, which limits clinical application of this method.

Rapid hybrid capture-based method can reduce the hybridization time

to 2 h; however, time for the whole process of the hybrid

capture-based tNGS is still longer than that of amplicon-based

method at ~16 vs. ~12 h, respectively.

Enriching pathogen nucleic acid sequences being

targeted can increase detection sensitivity (2). The virus identification ability

between host depletion methods and target enrichment have been

compared. Targeted capture-based approaches increase the nucleic

acid of 90% viruses assessed, but host nucleic acid load was at

times not reduced successfully (32). Zhao et al (22) used tNGS to enrich ribosomal RNA

(rRNA) and reported that the quantity of microbial nucleic acid

increases seven-fold. The detection results are consistent with the

clinical findings for the identification of virus, fungus and

antimicrobial resistance, demonstrating the accuracy of the

detection method. Through enrichment, tNGS increases abundance and

coverage of fastidious or low-abundance pathogens to improve

reliability of detection results. In a study assessing fever in

children using hybrid capture-based tNGS, the median increase in

the reads of viruses as a percentage of all reads post-capture was

674-fold and the median genome coverage increased from 2.1 to 83.2%

post-capture. This can also be applied for the analysis of an

anrovirus, even if its sequences have up to 58% variation from the

reference sequences used to select the capture probes (21).

The chemistry and software used in mNGS and

capture-based tNGS and amplification-based tNGS vary notably. mNGS

commonly uses reagents such as nucleotides and enzymes, including

DNA polymerases (33). In addition

to these, amplification-based tNGS requires primers specific to the

targeted pathogens (34).

Conversely, capture-based tNGS uses biotinylated oligonucleotide

probes and streptavidin-coated magnetic beads instead of primers

(35). Regarding bioinformatics

analysis, sequence-based ultra-rapid+ pipeline is frequently used

in mNGS for processing data, including the filtration of host

sequences and identification of microbial sequences (36). The open-source platform IDseq is

also widely applied in mNGS (37).

Amplification-based tNGS often uses Primer3 for designing PCR

primers and quantitative insights into microbial ecology for

sequence analysis and microbial community profiling (38,39).

Since capture-based tNGS is relatively new, researchers often

develop custom pipelines in-house, combining steps for alignment,

variant calling and annotation tailored to the captured targets

(40). These techniques, along

with associated costs, vary in terms of reagent and computational

resource requirement. Amplification-based methods generally incur

higher costs due to the necessity of specific primers and enzymes.

By contrast, capture-based methods, while having high initial costs

for probe design, benefit from lower ongoing operational costs.

Notably, when considering the number of reads per workflow, the

cost of capture-based tNGS is comparable to that of mNGS, at

US$150–160 per sample. Although capture-based tNGS requires notably

less time for bioinformatics analysis compared with mNGS at 5 min

vs. 1.5 h, it requires an additional 12 h for target enrichment

(41).

A notable variant of preliminary tNGS integrates 16S

rRNA gene PCR amplification with Sanger sequencing. A study using

this method in clinical pathogen identification for infective

endocarditis reported that sensitivity, specificity and positive

predictive value and negative predictive value of tNGS were 92, 78,

78 and 92% respectively, compared with the culture methods, which

reported values of 44, 100, 39 and 100%, respectively,

demonstrating a significantly higher sensitivity (56). Further research on patients with

infective endocarditis reported a similarly high positive ratio

associated with this form of tNGS (50,57).

Moreover, tNGS is used for pathogen identification in synovial

fluid from patients with periprosthetic joint infections, where the

sensitivity and specificity of tNGS are 69 and 100% respectively,

which are lower compared with the culture method which had

sensitivity and specificity values of 72 and 100%, respectively

(58). Furthermore, a comparative

study between these two forms of preliminary tNGS report that 16S

rRNA gene PCR amplification followed by NGS exhibits higher

accuracy compared with Sanger sequencing (59). Another study highlighted that after

the sequencing method was changed from NGS to Sanger, based on 16S

rRNA gene PCR amplification, notably increased the test positivity

rate by 87% (60).

Amidst the challenges posed by the COVID-19

pandemic, tNGS has been used for infectious disease surveillance

and genotyping (61,62). A comprehensive study including the

surveillance data from six hospitals in Guangzhou (China) in

2022–2023 used a number of methodologies, including tNGS, to

elucidate dynamics of the pandemic (61). The aforementioned study reported

the Οmicron BA.5.2 variant as the predominant strain in the region.

Furthermore, ~49.8% of SARS-CoV-2 infections are concomitant with

other pathogenic infections, underscoring the complexity of

clinical management scenarios during the pandemic (61). Danilenko et al (63) applied tNGS for mutation analysis of

the A(H1N1)pdm09 viruses, reporting an association between the

hemagglutinin D222G/N mutation and mortality, thereby

offering insight for effective disease prevention strategies.

Moreover, Chao et al (64)

reported the use of tNGS in pathogen identification in patients

with acute lower respiratory tract infection. Benchmarked against

the gold standard sputum culture, tNGS has a notable positive rate

of 95.6% (64). tNGS can also be

used in pediatric populations, with numerous studies reporting its

clinical applicability (65–68).

Lin et al (65) used

respiratory pathogen identity/antimicrobial resistance enrichment

sequencing (RPIP), a type of tNGS predicated on probe hybridization

capture, for analysis of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

samples from children with respiratory infections. RPIP

demonstrated sensitivities and specificities of 84.4 and 97.7%,

respectively, compared with culture-based gold standards (65). Moreover, another study reported the

use of tNGS in identification of pneumonia in children through

testing upper respiratory tract samples (66). Recent studies have reported the use

of tNGS in identifying rare pathogens, including Legionella

pneumophila, Chlamydia psittaci, Tropheryma whipplei, Aspergillus

fumigatus and Cryptococcus neoformans (69–72).

A number of studies have reported the feasibility of

tNGS in clinical application by comparing mNGS with tNGS (41,73).

A study compared the performance of mNGS and tNGS in the detection

of BALF specimens from patients with respiratory pathogen

infection. tNGS demonstrated a similar performance to mNGS but the

sequencing data were 1/3 of mNGS. The overall accuracy of tNGS

workflow was 65.6%, which is similar to mNGS workflow at 67.1%

(41). In another study of

patients with lung infection, tNGS comprised 153 species and had a

comparable detection rate to mNGS (82.17 vs. 86.51%, respectively).

Detection rate of tNGS in bacteria, fungi and viruses was

consistent with mNGS (73). These

findings underscore the significance and practicality of tNGS in

the clinical landscape, particularly in respiratory infectious

disease.

tNGS has been used to diagnose and manage

bloodstream infection in hospitalized patients, owing to its high

sensitivity, specificity and broad-spectrum pathogen detection

capabilities. Studies (74,75)

have reported the ability of tNGS to detect P. falciparum, a

malaria-causing parasite (74). In

Ghana, a tNGS approach using probes, has been used in the

surveillance of malaria in pediatric populations (75). Furthermore, Deng et al

(76) reported a metagenomic

sequencing method using primer enrichment that enriches targeted

RNA viral genomes. This methodology has improved viral diagnostics

in blood, reporting a median ten-fold enrichment and a notable

increase in genome coverage, which is particularly effective for

hard-to-detect viruses such as Zika and Ebola (76). In a comprehensive study (77), a tNGS termed ultrasensitive

single-genome sequencing (uSGS) was assessed. The aforementioned

study used uSGS for the diagnosis of patients infected with HIV-1,

reporting a >100-fold greater depth in HIV-1 RNA sequencing.

This approach not only decreases PCR errors but also offers

improved variant detection (77).

Moreover, targeted amplification sequencing technologies including

ampliseq detection system have demonstrated promising results in

rapidly identifying pathogens directly from blood samples, with a

detection accuracy >92.81% in both spiked samples and clinical

specimens (78). These results

underscore the role of tNGS in improving diagnostic precision and

guiding effective treatment strategies in clinical bloodstream

infections.

In a broader clinical context, a study of patients

with meningitis reported that tNGS exhibits improved sensitivity

compared with mNGS at 70.8 vs. 41.7%, respectively. tNGS has

improved diagnostic speed and cost-effectiveness. However, mNGS has

specificity at 78.6 vs. 64.3%, respectively. These findings suggest

that tNGS could be more suitable in certain clinical settings, such

as when pathogens cannot be detected by conventional methods

(82).

tNGS identifies antimicrobial resistance genes by

enriching target regions. In a study using RPIP for detection of

pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes in 201 respiratory

tract samples, 53.8% of antimicrobial resistance genes reported by

RPIP were consistent with clinical drug susceptibility testing

(41). Nevertheless, the

antimicrobial resistance effect of the same gene in different

microorganisms is unequal. In the aforementioned study, the

blaOXA genes encoding carbapenemases were

detected in multiple Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates;

however, these were demonstrated to be susceptible to carbapenems.

Therefore, considering the complexity of drug resistance genes and

current databases requiring supplementation, it is necessary to

analyze resistance genes in combination with pathogenic strains in

single test. Lin et al (65) evaluated the efficacy of RPIP in

pediatric patients with respiratory infections. The aforementioned

study included 25 patients with confirmed Streptococcus

pneumoniae infection who were tested for a spectrum of

antimicrobial resistance genes. A total of 58 antimicrobial

resistance genes associated with resistance to tetracycline,

macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin, β-lactams, sulfonamides and

aminoglycosides, were identified in 19 patients. Compared with the

results from clinical drug susceptibility testing, the concordance

rates for erythromycin, tetracycline, penicillin and sulfonamides

resistance are 89.5, 79.0, 36.8 and 42.1%, respectively (65). Application of tNGS for

antimicrobial resistance gene detection has been extensively

documented in an array of infectious diseases, including

bloodstream infections, localized infection, infective

endocarditis, urinary tract infections, malaria and leprosy

(57,74,75,77,78,85–88).

In TB infections, the main challenge lies in the

accessibility of efficient pathogen identification and

comprehensive drug susceptibility testing. The World Health

Organization recommended the Deeplex Myc-TB assay, a tNGS using

multiplex PCR amplification (89–94).

This assay has efficacy in prediction of resistance profiles

against anti-tuberculous drugs (89–94).

A study reported the high predictive accuracy of Deeplex Myc-TB

with sensitivity of 95.3% and specificity of 97.4% in determining

resistance to both first and second-line anti-TB medications. When

used in the analysis of sputum samples, Deeplex Myc-TB parallels,

and in some cases exceeds, performance of other advanced

whole-genome sequencing methodologies (89). Sibandze et al (93) reported on the use of Deeplex Myc-TB

with stool samples; this is an advancement for patient populations

that are unable to provide sputum samples.

A number of other tNGS platforms have been used in

the clinical application of TB testing. Predominantly, these

platforms are used in the assessment of respiratory tract specimens

(Table IV). For example, Wu et

al (95) reported the efficacy

of a multiplex PCR-based tNGS approach in the detection of MTB and

its resistance to first-line drugs directly from BALF,

demonstrating commensurate performance with traditional diagnostic

methodologies, while assessing a broader range of resistance genes.

Likewise, Colman et al (96) reported rapid and efficient

characterization of drug resistant TB directly from sputum samples

using amplicon sequencing. This method demonstrates a high

concordance with phenotypic drug susceptibility testing and detects

low abundance resistant variants (96). The effectiveness of tNGS in sputum

samples detection has been validated by numerous subsequent studies

(97–99). Extending beyond respiratory

samples, tNGS has applicability in other types of clinical

specimen. A study used tNGS for the detection of MTB in spinal

tissues, demonstrating higher sensitivity compared with traditional

culture methods at 100.00 vs. 18.75%, respectively. This approach

successfully identifies antimicrobial resistance genes and

mutations associated with drug resistance and suggests potential

use in guiding personalized treatment strategies (100). A study assessing lung tissue

samples from patients with TB reported the effectiveness of tNGS in

detecting antimicrobial resistance (101). Furthermore, Song et al

(102) reported the application

of amplicon-based tNGS for diagnosing drug resistant TB using

formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues. The

aforementioned study reported that the detection sensitivity of

tNGS for first-line drugs like rifampicin and isoniazid is high at

96 and 94%, respectively. The aforementioned study demonstrated the

feasibility of using tNGS for FFPE samples, which can be

challenging due to DNA degradation and reported advantages in terms

of cost-efficiency, customizable for specific pathogen detection

and reduced testing durations (102).

It has been reported that results obtained by tNGS

are more concise than those reported by mNGS (41). In a comparative study of mNGS and

tNGS, the number of analytes for mNGS workflow was 4–24 per sample,

while one or two analytes were identified by tNGS (41). These results were compared with a

comprehensive mNGS database, which covers tens of thousands of

microorganisms, the tNGS database includes information on dozens to

hundreds of target pathogens, with more in-depth and nuanced

differentiation of subspecies and subtypes. In bioinformatics

analysis workflows, 96.8% of microorganisms detected by mNGS are

interpreted as non-pathogenic microorganism, while 75.2%

microorganisms detected by tNGS are interpreted as non-pathogenic

microorganisms (41). Moreover,

refining the design of a database for tNGS is complex but

necessary. A good design of the database can ensure accurate

identification of pathogens. In a comparative study of tNGS and

mNGS, Pneumocystis carinii was detected by both methods, but

not reported, as it was considered a non-pathogenic microorganism

for humans, and Cryptococcus neoformans was incorrectly

reported as Cryptococcus gattii by tNGS (103).

Where mNGS sequences all nucleic acids present in a

sample, tNGS only detects pathogens within the designed panel,

resulting in a more stable performance and lower cost of sequencing

at 1/3-1/2 of the cost of mNGS. Considering of the simplified

interpretation and low cost, tNGS testing may be suitable for use

in hospital microbiology laboratories. Overall, tNGS is more

economical and may be more suitable for clinical application.

tNGS represents an advancement in infectious disease

diagnostics, particularly in its capacity to identify a range of

common pathogens via meticulously designed panels. This technology

increases the reliability of detection results through its targeted

amplification approach. tNGS may bridge the diagnostic gap between

conventional tests and mNGS. tNGS has attracted attention of the

clinical testing community. However, operational efficiency and

applicability of tNGS are dependent on a number of factors,

including the need to define the sample type, target pathogen

range, positive judgment value and supporting database.

tNGS may not operate in isolation but in conjunction

with conventional testing methods. This approach may contribute to

effective and precise clinical diagnosis. By combining the

universality of conventional tests with high specificity and

sensitivity of tNGS, clinicians may be better equipped to make more

accurate diagnoses. This integrated diagnostic strategy may improve

patient outcomes by enabling timely and appropriate therapeutic

interventions.

In summary, tNGS may serve a role in infectious

disease diagnostics. By addressing limitations of current testing

methodologies, tNGS may provide a more refined, accurate and

comprehensive approach to pathogen detection. Its continued

development and integration into clinical practice may impact

infectious disease diagnosis and management.

Not applicable.

The present study was supported by National High Level Hospital

Clinical Research Funding (grant no. 2022-PUMCH-A-139).

Not applicable.

QYC and JY supervised the study and wrote the

manuscript. YWL, YL, CLY, YJS and JD analyzed data. DJG and HL

wrote the manuscript. YC and YCX reviewed the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S,

Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, et

al: Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20

age groups in 1990 and 2010: A systematic analysis for the global

burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 380:2095–2128. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Chiu CY and Miller SA: Clinical

metagenomics. Nat Rev Genet. 20:341–355. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Li N, Cai Q, Miao Q, Song Z, Fang Y and Hu

B: High-throughput metagenomics for identification of pathogens in

the clinical settings. Small Methods. 5:20007922021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Wilson MR, Naccache SN, Samayoa E, Biagtan

M, Bashir H, Yu G, Salamat SM, Somasekar S, Federman S, Miller S,

et al: Actionable diagnosis of neuroleptospirosis by

next-generation sequencing. N Engl J Med. 370:2408–2417. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Blauwkamp TA, Thair S, Rosen MJ, Blair L,

Lindner MS, Vilfan ID, Kawli T, Christians FC, Venkatasubrahmanyam

S, Wall GD, et al: Analytical and clinical validation of a

microbial cell-free DNA sequencing test for infectious disease. Nat

Microbiol. 4:663–674. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Wilson MR, Sample HA, Zorn KC, Arevalo S,

Yu G, Neuhaus J, Federman S, Stryke D, Briggs B, Langelier C, et

al: Clinical metagenomic sequencing for diagnosis of meningitis and

encephalitis. N Engl J Med. 380:2327–2340. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ramachandran PS and Wilson MR:

Metagenomics for neurological infections-expanding our imagination.

Nat Rev Neurol. 16:547–556. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Han D, Li R, Shi J, Tan P, Zhang R and Li

J: Liquid biopsy for infectious diseases: A focus on microbial

cell-free DNA sequencing. Theranostics. 10:5501–5513. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Zheng Y, Qiu X, Wang T and Zhang J: The

Diagnostic value of metagenomic next-generation sequencing in lower

respiratory tract infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol.

11:6947562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song

J, Zhao X, Huang B, Shi W, Lu R, et al: A novel coronavirus from

patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 382:727–733.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Gu L, Liu W, Ru M, Lin J, Yu G, Ye J, Zhu

ZA, Liu Y, Chen J, Lai G and Wen W: The application of metagenomic

next-generation sequencing in diagnosing Chlamydia psittaci

pneumonia: A report of five cases. BMC Pulm Med. 20:652020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Miao Q, Ma Y, Wang Q, Pan J, Zhang Y, Jin

W, Yao Y, Su Y, Huang Y, Wang M, et al: Microbiological diagnostic

performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing when applied

to clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis. 67 (Suppl 2):S231–S240.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Shi CL, Han P, Tang PJ, Chen MM, Ye ZJ, Wu

MY, Shen J, Wu HY, Tan ZQ, Yu X, et al: Clinical metagenomic

sequencing for diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis. J Infect.

81:567–574. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Zhang Y, Cui P, Zhang HC, Wu HL, Ye MZ,

Zhu YM, Ai JW and Zhang WH: Clinical application and evaluation of

metagenomic next-generation sequencing in suspected adult central

nervous system infection. J Transl Med. 18:1992020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Zhou Y, Xu Y, Gong Y, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Wang

C, Yao R, Li P, Guan Y, Wang J, et al: Clinical factors associated

with circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in primary breast cancer. Mol

Oncol. 13:1033–1046. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ji XC, Zhou LF, Li CY, Shi YJ, Wu ML,

Zhang Y, Fei XF and Zhao G: Reduction of human DNA contamination in

clinical cerebrospinal fluid specimens improves the sensitivity of

metagenomic next-generation sequencing. J Mol Neurosci. 70:659–666.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Bal A, Pichon M, Picard C, Casalegno JS,

Valette M, Schuffenecker I, Billard L, Vallet S, Vilchez G, Cheynet

V, et al: Quality control implementation for universal

characterization of DNA and RNA viruses in clinical respiratory

samples using single metagenomic next-generation sequencing

workflow. BMC Infect Dis. 18:5372018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bowden R, Davies RW, Heger A, Pagnamenta

AT, de Cesare M, Oikkonen LE, Parkes D, Freeman C, Dhalla F, Patel

SY, et al: Sequencing of human genomes with nanopore technology.

Nat Commun. 10:18692019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Gu W, Crawford ED, O'Donovan BD, Wilson

MR, Chow ED, Retallack H and DeRisi JL: Depletion of abundant

sequences by hybridization (DASH): Using Cas9 to remove unwanted

high-abundance species in sequencing libraries and molecular

counting applications. Genome Biol. 17:412016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Gu W, Miller S and Chiu CY: clinical

metagenomic next-generation sequencing for pathogen detection. Annu

Rev Pathol. 14:319–338. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Wylie TN, Wylie KM, Herter BN and Storch

GA: Enhanced virome sequencing using targeted sequence capture.

Genome Res. 25:1910–1920. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Zhao N, Cao J, Xu J, Liu B, Liu B, Chen D,

Xia B, Chen L, Zhang W, Zhang Y, et al: Targeting RNA with next-

and third-generation sequencing improves pathogen identification in

clinical samples. Adv Sci (Weinh). 8:e21025932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Medicine CSoL: Expert consensus on the

standardized management of bioinformatics analysis for the

detection of pathogenic microorganisms in mNGS. Chin J Lab Med.

44:799–807. 2021.

|

|

24

|

Wang Q, Wu B, Yang D, Yang C, Jin Z, Cao J

and Feng J: Optimal specimen type for accurate diagnosis of

infectious peripheral pulmonary lesions by mNGS. BMC Pulm Med.

20:2682020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Fang X, Mei Q, Fan X, Zhu C, Yang T, Zhang

L, Geng S and Pan A: Diagnostic value of metagenomic

next-generation sequencing for the detection of pathogens in

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in ventilator-associated pneumonia

patients. Front Microbiol. 11:5997562020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mongkolrattanothai K, Naccache SN, Bender

JM, Samayoa E, Pham E, Yu G, Dien Bard J, Miller S, Aldrovandi G

and Chiu CY: Neurobrucellosis: Unexpected answer from metagenomic

next-generation sequencing. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 6:393–398.

2017.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Mason A, Foster D, Bradley P, Golubchik T,

Doumith M, Gordon NC, Pichon B, Iqbal Z, Staves P, Crook D, et al:

Accuracy of different bioinformatics methods in detecting

antibiotic resistance and virulence factors from staphylococcus

aureus whole-genome sequences. J Clin Microbiol. 56:e01815–17.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Singh RR: Target enrichment approaches for

next-generation sequencing applications in oncology. Diagnostics

(Basel). 12:15392022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Xiao M, Liu X, Ji J, Li M, Li J, Yang L,

Sun W, Ren P, Yang G, Zhao J, et al: Multiple approaches for

massively parallel sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 genomes directly from

clinical samples. Genome Med. 12:572020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Briese T, Kapoor A, Mishra N, Jain K,

Kumar A, Jabado OJ and Lipkin WI: Virome capture sequencing enables

sensitive viral diagnosis and comprehensive virome analysis. mBio.

6:e01491–15. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Bonsall D, Ansari MA, Ip C, Trebes A,

Brown A, Klenerman P, Buck D; STOP-HCV Consortium, ; Piazza P,

Barnes E and Bowden R: ve-SEQ: Robust, unbiased enrichment for

streamlined detection and whole-genome sequencing of HCV and other

highly diverse pathogens. F1000Res. 4:10622015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Piantadosi A, Mukerji SS, Ye S, Leone MJ,

Freimark LM, Park D, Adams G, Lemieux J, Kanjilal S, Solomon IH, et

al: Enhanced virus detection and metagenomic sequencing in patients

with meningitis and encephalitis. mBio. 12:e01143212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Wang ZY, Li LL, Cao XL, Li P, Du J, Zou MJ

and Wang LL: Clinical application of amplification-based versus

amplification-free metagenomic next-generation sequencing test in

infectious diseases. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 13:11381742023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Zhang D, Zhang J, Du J, Zhou Y, Wu P, Liu

Z, Sun Z, Wang J, Ding W, Chen J, et al: Optimized sequencing

adaptors enable rapid and real-time metagenomic identification of

pathogens during runtime of sequencing. Clin Chem. 68:826–836.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Deng X, Achari A, Federman S, Yu G,

Somasekar S, Bártolo I, Yagi S, Mbala-Kingebeni P, Kapetshi J,

Ahuka-Mundeke S, et al: Metagenomic sequencing with spiked primer

enrichment for viral diagnostics and genomic surveillance. Nat

Microbiol. 5:443–454. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Miller S, Naccache SN, Samayoa E, Messacar

K, Arevalo S, Federman S, Stryke D, Pham E, Fung B, Bolosky WJ, et

al: Laboratory validation of a clinical metagenomic sequencing

assay for pathogen detection in cerebrospinal fluid. Genome Res.

29:831–842. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kalantar KL, Carvalho T, de Bourcy CFA,

Dimitrov B, Dingle G, Egger R, Han J, Holmes OB, Juan YF, King R,

et al: IDseq-An open source cloud-based pipeline and analysis

service for metagenomic pathogen detection and monitoring.

Gigascience. 9:giaa1112020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Nugen SR, Leonard B and Baeumner AJ:

Application of a unique server-based oligonucleotide probe

selection tool toward a novel biosensor for the detection of

Streptococcus pyogenes. Biosens Bioelectron. 22:2442–2448. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Siegwald L, Touzet H, Lemoine Y, Hot D,

Audebert C and Caboche S: Assessment of common and emerging

bioinformatics pipelines for targeted metagenomics. PLoS One.

12:e01695632017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Simner PJ, Miller HB, Breitwieser FP,

Pinilla Monsalve G, Pardo CA, Salzberg SL, Sears CL, Thomas DL,

Eberhart CG and Carroll KC: Development and optimization of

metagenomic next-generation sequencing methods for cerebrospinal

fluid diagnostics. J Clin Microbiol. 56:e00472–18. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Gaston DC, Miller HB, Fissel JA, Jacobs E,

Gough E, Wu J, Klein EY, Carroll KC and Simner PJ: Evaluation of

metagenomic and targeted next-generation sequencing workflows for

detection of respiratory pathogens from bronchoalveolar lavage

fluid specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 60:e00526222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Gauduchon V, Chalabreysse L, Etienne J,

Célard M, Benito Y, Lepidi H, Thivolet-Béjui F and Vandenesch F:

Molecular diagnosis of infective endocarditis by PCR amplification

and direct sequencing of DNA from valve tissue. J Clin Microbiol.

41:763–766. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Marín M, Muñoz P, Sánchez M, Del Rosal M,

Alcalá L, Rodríguez-Créixems M and Bouza E; Group for the

Management of Infective Endocarditis of the Gregorio Marañón

Hospital (GAME), : Molecular diagnosis of infective endocarditis by

real-time broad-range polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and

sequencing directly from heart valve tissue. Medicine (Baltimore).

86:195–202. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Vondracek M, Sartipy U, Aufwerber E,

Julander I, Lindblom D and Westling K: 16S rDNA sequencing of valve

tissue improves microbiological diagnosis in surgically treated

patients with infective endocarditis. J Infect. 62:472–478. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Maneg D, Sponsel J, Müller I, Lohr B,

Penders J, Madlener K and Hunfeld KP: Advantages and limitations of

direct PCR amplification of bacterial 16S-rDNA from resected heart

tissue or swabs followed by direct sequencing for diagnosing

infective endocarditis: A retrospective analysis in the routine

clinical setting. Biomed Res Int. 2016:79238742016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Peeters B, Herijgers P, Beuselinck K,

Verhaegen J, Peetermans WE, Herregods MC, Desmet S and Lagrou K:

Added diagnostic value and impact on antimicrobial therapy of 16S

rRNA PCR and amplicon sequencing on resected heart valves in

infective endocarditis: A prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol

Infect. 23:888.e1–888.e5. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Kim MS, Chang J, Kim MN, Choi SH, Jung SH,

Lee JW and Sung H: Utility of a direct 16S rDNA PCR and sequencing

for etiological diagnosis of infective endocarditis. Ann Lab Med.

37:505–510. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Santibáñez P, García-García C, Portillo A,

Santibáñez S, García-Álvarez L, de Toro M and Oteo JA: What does

16S rRNA gene-targeted next generation sequencing contribute to the

study of infective endocarditis in heart-valve tissue? Pathogens.

11:342021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Flurin L, Wolf MJ, Fisher CR, Cano

Cevallos EJ, Vaillant JJ, Pritt BS, DeSimone DC and Patel R:

Pathogen detection in infective endocarditis using targeted

metagenomics on whole blood and plasma: A prospective pilot study.

J Clin Microbiol. 60:e00621222022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Hong HL, Flurin L, Greenwood-Quaintance

KE, Wolf MJ, Pritt BS, Norgan AP and Patel R: 16S rRNA gene

PCR/sequencing of heart valves for diagnosis of infective

endocarditis in routine clinical practice. J Clin Microbiol.

61:e00341232023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Poulsen SH, Søgaard KK, Fuursted K and

Nielsen HL: Evaluating the diagnostic accuracy and clinical utility

of 16S and 18S rRNA gene targeted next-generation sequencing based

on five years of clinical experience. Infect Dis (Lond).

55:767–775. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Hong HL, Flurin L, Thoendel MJ, Wolf MJ,

Abdel MP, Greenwood-Quaintance KE and Patel R: Targeted versus

shotgun metagenomic sequencing-based detection of microorganisms in

sonicate fluid for periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis. Clin

Infect Dis. 76:e1456–e1462. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Fida M, Wolf MJ, Hamdi A, Vijayvargiya P,

Esquer Garrigos Z, Khalil S, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Thoendel MJ

and Patel R: Detection of pathogenic bacteria from septic patients

using 16s ribosomal RNA gene-targeted metagenomic sequencing. Clin

Infect Dis. 73:1165–1172. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Okuda KI, Yoshii Y, Yamada S, Chiba A,

Hironaka I, Hori S, Yanaga K and Mizunoe Y: Detection of bacterial

DNA from central venous catheter removed from patients by next

generation sequencing: A preliminary clinical study. Ann Clin

Microbiol Antimicrob. 17:442018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Flurin L, Wolf MJ, Greenwood-Quaintance

KE, Sanchez-Sotelo J and Patel R: Targeted next generation

sequencing for elbow periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis.

Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 101:1154482021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Miller RJ, Chow B, Pillai D and Church D:

Development and evaluation of a novel fast broad-range 16S

ribosomal DNA PCR and sequencing assay for diagnosis of bacterial

infective endocarditis: Multi-year experience in a large Canadian

healthcare zone and a literature review. BMC Infect Dis.

16:1462016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Mularoni A, Mikulska M, Barbera F,

Graziano E, Medaglia AA, Di Carlo D, Monaco F, Bellavia D, Cascio

A, Raffa G, et al: Molecular analysis with 16S rRNA PCR/sanger

sequencing and molecular antibiogram performed on DNA extracted

from valve improve diagnosis and targeted therapy of infective

endocarditis: A prospective study. Clin Infect Dis. 76:e1484–e1491.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Flurin L, Hemenway JJ, Fisher CR, Vaillant

JJ, Azad M, Wolf MJ, Greenwood-Quaintance KE, Abdel MP and Patel R:

Clinical use of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene-based sanger and/or next

generation sequencing assay to test preoperative synovial fluid for

periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis. mBio. 13:e01322222022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Sabat AJ, van Zanten E, Akkerboom V,

Wisselink G, van Slochteren K, de Boer RF, Hendrix R, Friedrich AW,

Rossen JWA and Kooistra-Smid AMDM: Targeted next-generation

sequencing of the 16S-23S rRNA region for culture-independent

bacterial identification-increased discrimination of closely

related species. Sci Rep. 7:34342017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Flurin L, Wolf MJ, Mutchler MM, Daniels

ML, Wengenack NL and Patel R: Targeted metagenomic sequencing-based

approach applied to 2146 tissue and body fluid samples in routine

clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis. 75:1800–1808. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Cheng LL, Li SY and Zhong NS: New

characteristics of COVID-19 caused by the Omicron variant in

Guangzhou. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 46:441–443. 2023.(In

Chinese). PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Ramos N, Panzera Y, Frabasile S, Tomás G,

Calleros L, Marandino A, Goñi N, Techera C, Grecco S, Fuques E, et

al: A multiplex-NGS approach to identifying respiratory RNA viruses

during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Virol. 168:872023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Danilenko AV, Kolosova NP, Shvalov AN,

Ilyicheva TN, Svyatchenko SV, Durymanov AG, Bulanovich JA,

Goncharova NI, Susloparov IM, Marchenko VY, et al: Evaluation of

HA-D222G/N polymorphism using targeted NGS analysis in A(H1N1)pdm09

influenza virus in Russia in 2018–2019. PLoS One. 16:e02510192021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Chao L, Li J, Zhang Y, Pu H and Yan X:

Application of next generation sequencing-based rapid detection

platform for microbiological diagnosis and drug resistance

prediction in acute lower respiratory infection. Ann Transl Med.

8:16442020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Lin R, Xing Z, Liu X, Chai Q, Xin Z, Huang

M, Zhu C, Luan C, Gao H, Du Y, et al: Performance of targeted

next-generation sequencing in the detection of respiratory

pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes for children. J Med

Microbiol. 72:2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Ip M, Liyanapathirana V, Ang I, Fung KS,

Ng TK, Zhou H and Tsang DN: Direct detection and prediction of all

pneumococcal serogroups by target enrichment-based next-generation

sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 52:4244–4252. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Li F, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Shi P, Cao L, Su L,

Zhu Q, Wang L, Lu R, Tan W and Shen J: Etiology of severe pneumonia

in children in alveolar lavage fluid using a high-throughput gene

targeted amplicon sequencing assay. Front Pediatr. 9:6591642021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Dai Y, Sheng K and Hu L: Diagnostic

efficacy of targeted high-throughput sequencing for lower

respiratory infection in preterm infants. Am J Transl Res.

14:8204–8214. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Li S, Tong J, Li H, Mao C, Shen W, Lei Y

and Hu P: L. pneumophila infection diagnosed by tNGS in a

lady with lymphadenopathy. Infect Drug Resist. 16:4435–4442. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Zhang Y, Jiang X, Ye W and Sun J: Clinical

features and outcome of eight patients with Chlamydia

psittaci pneumonia diagnosed by targeted next generation

sequencing. Clin Respir J. 17:915–930. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Du ZM and Chen P: Co-infection of

Chlamydia psittaci and Tropheryma whipplei: A case

report. World J Clin Cases. 11:7144–7149. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Ren HQ, Zhao Q, Jiang J, Yang W, Fu AS and

Ge YL: Acute heart failure due to pulmonary Aspergillus

fumigatus and Cryptococcus neoformans infection

associated with COVID-19. Clin Lab; 69. 2023

|

|

73

|

Li S, Tong J, Liu Y, Shen W and Hu P:

Targeted next generation sequencing is comparable with metagenomic

next generation sequencing in adults with pneumonia for pathogenic

microorganism detection. J Infect. 85:e127–e129. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Kunasol C, Dondorp AM, Batty EM, Nakhonsri

V, Sinjanakhom P, Day NPJ and Imwong M: Comparative analysis of

targeted next-generation sequencing for Plasmodium falciparum drug

resistance markers. Sci Rep. 12:55632022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Mensah BA, Aydemir O, Myers-Hansen JL,

Opoku M, Hathaway NJ, Marsh PW, Anto F, Bailey J, Abuaku B and

Ghansah A: Antimalarial drug resistance profiling of plasmodium

falciparum infections in ghana using molecular inversion probes and

next-generation sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother.

64:e01423–19. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Deng X, Achari A, Federman S, Yu G,

Somasekar S, Bártolo I, Yagi S, Mbala-Kingebeni P, Kapetshi J,

Ahuka-Mundeke S, et al: Author correction: Metagenomic sequencing

with spiked primer enrichment for viral diagnostics and genomic

surveillance. Nat Microbiol. 5:5252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Boltz VF, Rausch J, Shao W, Hattori J,

Luke B, Maldarelli F, Mellors JW, Kearney MF and Coffin JM:

Ultrasensitive single-genome sequencing: accurate, targeted, next

generation sequencing of HIV-1 RNA. Retrovirology. 13:872016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Li Q, Huang W, Zhang S, Zheng Y, Lv Q,

Kong D, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Zhao Z, Wang M, et al: Target-enriched

sequencing enables accurate identification of bloodstream

infections in whole blood. J Microbiol Methods. 192:1063912022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Jiang J, Lv M, Yang K, Zhao G and Fu Y: A

case report of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of Listeria

monocytogenes meningitis with NGS. Open Life Sci.

18:202207382023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Chen W, Wu Y and Zhang Y: Next-generation

sequencing technology combined with multiplex polymerase chain

reaction as a powerful detection and semiquantitative method for

herpes simplex virus type 1 in adult encephalitis: A case report.

Front Med (Lausanne). 9:9053502022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Yang HH, He XJ, Nie JM, Guan SS, Chen YK

and Liu M: Central nervous system aspergillosis misdiagnosed as

Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis in a patient with AIDS: A

case report. AIDS Res Ther. 19:402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Gao D, Hu Y, Jiang X, Pu H, Guo Z and

Zhang Y: Applying the pathogen-targeted next-generation sequencing

method to pathogen identification in cerebrospinal fluid. Ann

Transl Med. 9:16752021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

McGill F, Tokarz R, Thomson EC, Filipe A,

Sameroff S, Jain K, Bhuva N, Ashraf S, Lipkin WI, Corless C, et al:

Viral capture sequencing detects unexpected viruses in the

cerebrospinal fluid of adults with meningitis. J Infect.

84:499–510. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Li J, Zhang L, Yang X, Wang P, Feng L, Guo

E and Chen Y: Diagnostic significance of targeted next-generation

sequencing in central nervous system infections in neurosurgery of

pediatrics. Infect Drug Resist. 16:2227–2236. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Huang C, Huang Y, Wang Z, Lin Y, Li Y,

Chen Y, Chen X, Zhang C, Li W, Zhang W, et al: Multiplex PCR-based

next generation sequencing as a novel, targeted and accurate

molecular approach for periprosthetic joint infection diagnosis.

Front Microbiol. 14:11813482023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Hulten KG, Genta RM, Kalfus IN, Zhou Y,

Zhang H and Graham DY: Comparison of culture with antibiogram to

next-generation sequencing using bacterial isolates and

formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded gastric biopsies.

Gastroenterology. 161:1433–1442.e2. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Ferreira I, Lepuschitz S, Beisken S, Fiume

G, Mrazek K, Frank BJH, Huber S, Knoll MA, von Haeseler A, Materna

A, et al: Culture-free detection of antibiotic resistance markers

from native patient samples by hybridization capture sequencing.

Microorganisms. 9:16722021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Jouet A, Braet SM, Gaudin C, Bisch G,

Vasconcellos S, Epaminondas Nicacio de Oliveira do Livramento RE,

Prado Palacios YY, Fontes AB, Lucena N, Rosa P, et al: Hi-plex deep

amplicon sequencing for identification, high-resolution genotyping

and multidrug resistance prediction of Mycobacterium leprae

directly from patient biopsies by using deeplex Myc-Lep.

EBioMedicine. 93:1046492023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Jouet A, Gaudin C, Badalato N,

Allix-Béguec C, Duthoy S, Ferré A, Diels M, Laurent Y, Contreras S,

Feuerriegel S, et al: Deep amplicon sequencing for culture-free

prediction of susceptibility or resistance to 13 anti-tuberculous

drugs. Eur Respir J. 57:20023382021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Cabibbe AM, Spitaleri A, Battaglia S,

Colman RE, Suresh A, Uplekar S, Rodwell TC and Cirillo DM:

Application of targeted next-generation sequencing assay on a

portable sequencing platform for culture-free detection of

drug-resistant tuberculosis from clinical samples. J Clin

Microbiol. 58:e00632–20. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Mesfin AB, Araia ZZ, Beyene HN, Mebrahtu

AH, Suud NN, Berhane YM, Hailu DT, Kassahun AZ, Auguet OT, Dean AS,

et al: First molecular-based anti-TB drug resistance survey in

Eritrea. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 25:43–51. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Mansoor H, Hirani N, Chavan V, Das M,

Sharma J, Bharati M, Oswal V, Iyer A, Morales M, Joshi A, et al:

Clinical utility of target-based next-generation sequencing for

drug-resistant TB. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 27:41–48. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Sibandze DB, Kay A, Dreyer V, Sikhondze W,

Dlamini Q, DiNardo A, Mtetwa G, Lukhele B, Vambe D, Lange C, et al:

Rapid molecular diagnostics of tuberculosis resistance by targeted

stool sequencing. Genome Med. 14:522022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Kambli P, Ajbani K, Kazi M, Sadani M, Naik

S, Shetty A, Tornheim JA, Singh H and Rodrigues C: Targeted next

generation sequencing directly from sputum for comprehensive

genetic information on drug resistant Mycobacterium

tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 127:1020512021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Wu X, Liang R, Xiao Y, Liu H, Zhang Y,

Jiang Y, Liu M, Tang J, Wang W, Li W, et al: Application of

targeted next generation sequencing technology in the diagnosis of

Mycobacterium tuberculosis and first line drugs resistance

directly from cell-free DNA of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. J

Infect. 86:399–401. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Colman RE, Anderson J, Lemmer D, Lehmkuhl

E, Georghiou SB, Heaton H, Wiggins K, Gillece JD, Schupp JM,

Catanzaro DG, et al: Rapid drug susceptibility testing of

drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis isolates directly

from clinical samples by use of amplicon sequencing: A

proof-of-concept study. J Clin Microbiol. 54:2058–2067. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Iyer A, Ndlovu Z, Sharma J, Mansoor H,

Bharati M, Kolan S, Morales M, Das M, Issakidis P, Ferlazzo G, et

al: Operationa-lising targeted next-generation sequencing for

routine diagnosis of drug-resistant TB. Public Health Action.

13:43–49. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Leung KS, Tam KK, Ng TT, Lao HY, Shek RC,

Ma OCK, Yu SH, Chen JX, Han Q, Siu GK and Yam WC: Clinical utility

of target amplicon sequencing test for rapid diagnosis of

drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis from respiratory

specimens. Front Microbiol. 13:9744282022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Comín J, Viñuelas J, Lafoz C, Cebollada A,

Ibarz D, Iglesias MJ and Samper S: Rapid identification of lineage

and drug resistance in clinical samples of Mycobacterium

tuberculosis. Microorganisms. 11:14672023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Zhang G, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Hu X, Tang M

and Gao Q: Targeted next-generation sequencing technology showed

great potential in identifying spinal tuberculosis and predicting

the drug resistance. J Infect. 87:e110–e112. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Murphy SG, Smith C, Lapierre P, Shea J,

Patel K, Halse TA, Dickinson M, Escuyer V, Rowlinson MC and Musser

KA: Direct detection of drug-resistant Mycobacterium

tuberculosis using targeted next generation sequencing. Front

Public Health. 11:12060562023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Song J, Du W, Liu Z, Che J, Li K and Che

N: Application of amplicon-based targeted NGS technology for

diagnosis of drug-resistant tuberculosis using FFPE specimens.

Microbiol Spectr. 10:e01358212022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Wilson MR, O'Donovan BD, Gelfand JM,

Sample HA, Chow FC, Betjemann JP, Shah MP, Richie MB, Gorman MP,

Hajj-Ali RA, et al: Chronic meningitis investigated via metagenomic

next-generation sequencing. JAMA Neurol. 75:947–955. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|