Introduction

Glioma is the most common malignant tumor in the

central nervous system (CNS). It occurs in any part of the CNS and

exhibits highly aggressive and malignant behavior. The survival

rates of glioma remain at a low level after the traditional

treatment, including surgical resection, radiotherapy, and

chemotherapy (1,2). Tumor necrosis factor-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) has become one of the hotspots in

the last several years (3). TRAIL has

shown great anticancer activity by selectively binding to death

receptor 4 (DR4) and death receptor 5 (DR5) and inducing tumor cell

apoptosis, while healthy cells remain affected (3–6). However,

blood-brain barrier (BBB), as a protective mechanism for CNS

tumors, prevents TRAIL from reaching tumor sites (7,8). TRAIL

cannot be applied in CNS cancer therapy owing to its short

half-life (9,10). TRAIL was combined with stem cells to

address these issues. Both neural stem cells (NSCs) and mesenchymal

stem cells (MSCs) were engineered to express TRAIL and restrict

glioma cells, showing bright prospects (11–15).

However, SCs had some limitations, such as uncertain

differentiation and difficulties in acquisition from adults.

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are the

precursors of endothelial cells, with CD31 and CD34 as their

specific surface markers. They were first isolated in 1997 from

human peripheral blood (16,17). EPCs are recruited in the

neovascularization of tumor and involved in tumor vascular network

(18,19). Owing to these characteristics, EPCs

have the potential to be involved in anti-tumor therapies. Most

previous studies explored anti-angiogenic treatment by suppressing

the mobilization and homing of EPCs to tumors (20). Increasing attention has been paid to

the use of EPCs as a vector for treatment (21,22).

Recent studies have demonstrated that EPCs can move across the BBB

from peripheral blood and participate in the angiogenesis of

gliomas (23,24). Compared with NSCs and MSCs, EPCs can

be obtained from peripheral blood, which means that EPCs can be

easily acquired from adults. This makes the autotransplantation of

EPCs possible and avoids immunological rejection. Therefore, EPCs

have been recognized as an ideal vector to deliver antineoplastic

molecules to CNS tumors. However, whether the TRAIL-expressing EPCs

home to glioma cells through the BBB and induce cell apoptosis

needs further investigation.

In this study, EPCs engineered with a lentivirus

encoding TRAIL were generated and used to induce apoptosis of a

glioma cell line SHG44. First, the Transwell assay was used to

verify that EPCs could home to glioma cells. Then, the co-culture

system of TRAIL-overexpressing EPCs and SHG44 cells was

established, and the apoptotic state of SHG44 cells was examined.

Interestingly, the apoptosis percentage and change in protein

levels of caspase-8 and −3, as well as poly ADP-ribose polymerase

(PARP), in SHG44 cells were found to increase remarkably. Taken

together, the study demonstrated that the TRAIL-modified EPCs could

be a feasible approach for glioma therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures

Human glioma cell line, SHG44 cells, were purchased

from Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and cultured in

Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)/high-glucose medium

(HyClone; GE Healthcare, Logan, UT, USA) with 10% fetal bovine

serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA), 0.5 mm glutamine, and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin at

37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and

95% air.

EPCs were extracted from the blood of neonatal

Sprague-Dawley rats by the density gradient method, as previously

described (25), and cultured in

endothelial cell growth medium-2 (EGM-2; Lonza, Group, Ltd., Basel,

Switzerland) culture medium with 10% FBS (Gibco; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.), 0.5 mm glutamine, and 100 U/ml

penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at

37°C.

Immunocytochemical analysis

EPCs were washed twice with phosphate-buffered

saline (PBS) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C overnight.

After removing paraformaldehyde and washing the cells with PBS, 3%

H2O2 was used to inactivate endogenous

peroxidase for 10 min. The cells were incubated with 5% bovine

serum albumin (BSA) for 1 h at room temperature to block the

nonspecific binding. Then, the primary antibodies (CD31 and CD34,

from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) were added onto cells and incubated

at 4°C for 12 h. Only PBS with 5% BSA was used as negative control.

The cells were washed with PBS three times to remove unbound

antibody and then incubated with secondary antibody conjugated to

horseradish peroxidase (HRP; ZSGF-BIO, China) for 30 min at room

temperature. After removing the secondary antibody by washing with

PBS, the cells were incubated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine developer,

counterstained with hematoxylin, and observed under a

microscope.

Immunofluorescence

EPCs were washed with PBS and fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde after 3 days of lentiviral transfection. The cells

were blocked with 5% BSA for 30 min and then incubated with primary

antibodies (TRAIL, DR4, and DR5; Abcam) at 4°C for 12 h. After the

cells were washed with PBS, secondary antibodies were used for

staining (Alexa 594 conjugated; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.;

Alexa 405 conjugated; Wuhan Sanying Biotechnology, Wuhan, China).

Cells were observed using laser scanning confocal microscopy (Nikon

Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

Angiogenesis assay

BD Matrigel basement membrane matrix (BD

Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was melted at 0°C, implanted

in a 24-pore culture plate, and then placed in a 37°C incubator for

1 h. EPCs were inoculated on the surface of solidified Matrigel

(5×104 cells per well) and cultured in a 5%

CO2 atmosphere at 37°C. The cells were observed under a

microscope after 6 h, and images were taken under magnification,

×40 and ×100.

Lentiviral infection

The lentivirus with the TRAIL sequence was delivered

to overexpress the TRAIL protein in EPCs. The negative control

virus carrying green fluorescent protein (GFP) only was used as a

control. Both viruses were constructed and packed by Shanghai

GeneChem Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. EPCs were infected using

lentiviruses with a multiplicity of infection of 10 on the second

day after the first passage of EPCs.

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, and

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(RT-qPCR)

After a week of lentiviral infection, total RNA was

extracted from EPCs in both the groups using TRIzol reagent

(Solarbio, Beijing, China), chloroform, and isopropyl alcohol.

Then, 1 µg of extracted RNA was reverse transcribed into strand

cDNA after removing genomic DNA using a PrimeScript Reverse

Transcription Reagent kit with gDNA Eraser (TaKaRa Bio Co., Ltd.,

Otsu, Japan). Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

(PCR) was performed on Roche LightCycler (Roche Applied Science,

Rotkreuz, Switzerland) using the same reagent kit with cDNA

synthesis for the desired gene. The primers were designed and

synthesized by Sangon Biotech as follows:

TRAIL sense, 5′-AACTGGGACCAGAGGAAGAAGCAA-3′ and

antisense, 5′-ATGCCCACTCCTTGATGATTCCCA-3′;

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase sense,

5′-TCCTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′ and antisense,

5′-TCCTGCACCACCAACTGCTTAG-3′.

Co-culture

SHG44 cells were cultured with TRAIL-expressing EPCs

as the experimental group, or with EPCs expressing only GFP as the

control group. Both groups were in the same culture environment:

EGM-2 culture medium was used with 10% FBS, 0.5 mM glutamine, and

100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin in a 5% CO2 atmosphere

at 37°C.

Transwell migration assay

In vitro cell migration assays were performed

using 24-well Transwell chambers (12-µm pores; Corning Inc.,

Corning, NY, USA). Nontransfected EPCs and TRAIL-transfected EPCs

(2×104 cells per well) were cultured in the top chamber,

whereas SHG44 cells, as a positive group, were cultured in the

lower chamber. DMEM medium with 10% FBS only in the lower chamber

was used as the control group. After 24 h of cultivation, the cells

on the upper side were removed and the migrated cells were fixed in

4% paraformaldehyde, stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

(DAPI) solution, and examined using a high-content screening system

(HCS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Propidium iodide and Annexin V

assays

The cells were gently washed once with PBS on the

third day of co-culture and then stained with Annexin V-kFluor594

(Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) for 15 min at

room temperature away from light. The cells were observed under a

fluorescence microscope after replacing the staining solution with

PBS. The flow cytometry assay was performed using Annexin V-APC

(Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.) and propidium iodide (PI)

(Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd.), whose fluorescence signals were

excited at 633 and 488 nm and collected at 660 and 610 nm,

respectively, to determine the degree of apoptosis of SHG44 cells

further. More than 10,000 cells per sample group were collected and

divided into EPCs and SHG44 cells on the basis of GFP fluorescence

intensity. The percentage of Annexin V-positive SHG44 cells was

calculated as an indicator of apoptosis.

Co-immunoprecipitation

The cells from co-culture were homogenized in cell

lysis buffer (Solarbio), supplemented with 1 mM

phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) and complete protease

inhibitor mixture (Solarbio). The homogenate was centrifuged at

11,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with

anti-TRAIL (Abcam) crosslinked beads at 4°C overnight with

rotation. The Pierce Crosslink Magnetic IP kit instruction was used

for the pretreatment of beads and immunoprecipitation. The

associated proteins were detected using western blot analysis.

Homogenates from co-culture cells were used as positive

controls.

Quantitative immunoblot analysis

The cells in the two groups were collected on third

and fifth days of co-culture, homogenized in 1X cell lysis buffer

(Solarbio) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and complete protease

inhibitor mixture (Solarbio) for 30 min on ice, and then

centrifuged at 11,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was

measured using a Bicinchoninic Acid Protein Assay kit (Solarbio).

The measurement samples were combined with 5X SDS loading buffer

and boiled at 100°C for 10 min. For each protein, equal amounts of

samples (20–100 µg) from each group were analyzed using sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis as previously

described (26). After proteins were

transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, the membrane

was incubated with 5% BSA at room temperature for 2 h to block the

nonspecific protein site and then corresponded with primary

antibodies [TRAIL from Abcam; DR4 and DR5 from Abcam; vascular

endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGF-R2), caspase-8 and −3,

and PARP from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA);

β-actin from ZSGF-BIO] at 4°C overnight. This step was followed by

incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (ZSGF-BIO).

Visualization was achieved using a SuperSignal West Pico Trial kit

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Statistical analysis

Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation

(SD). One-way analysis of variance was used for comparisons among

multiple groups, followed by the Student post hoc two-tailed test.

The unpaired Student t-test was performed for comparisons between

the means of two groups. GraphPad 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La

Jolla, CA, USA) was used for all the statistical analyses.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Generation of TRAIL-expressing

EPCs

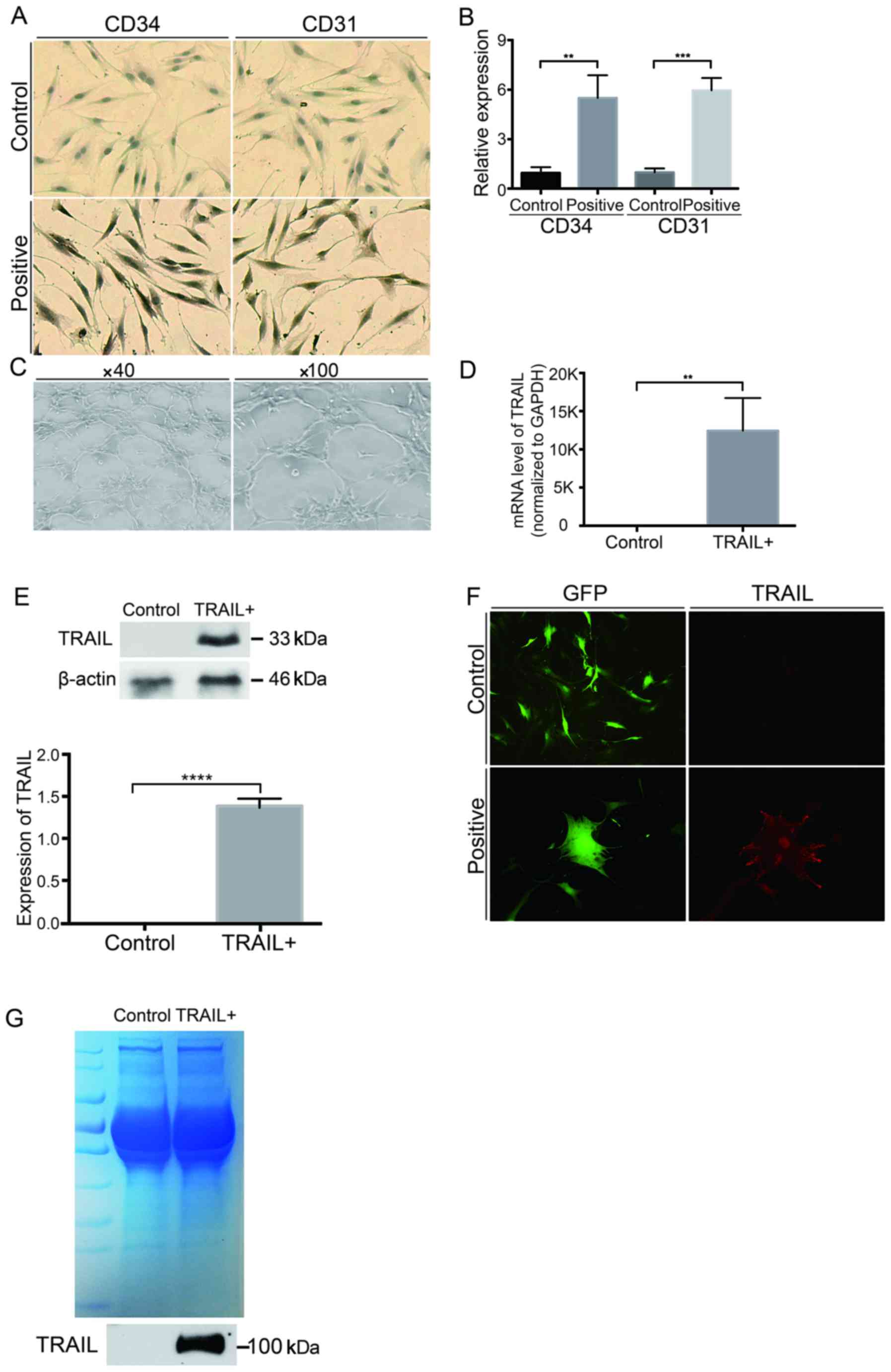

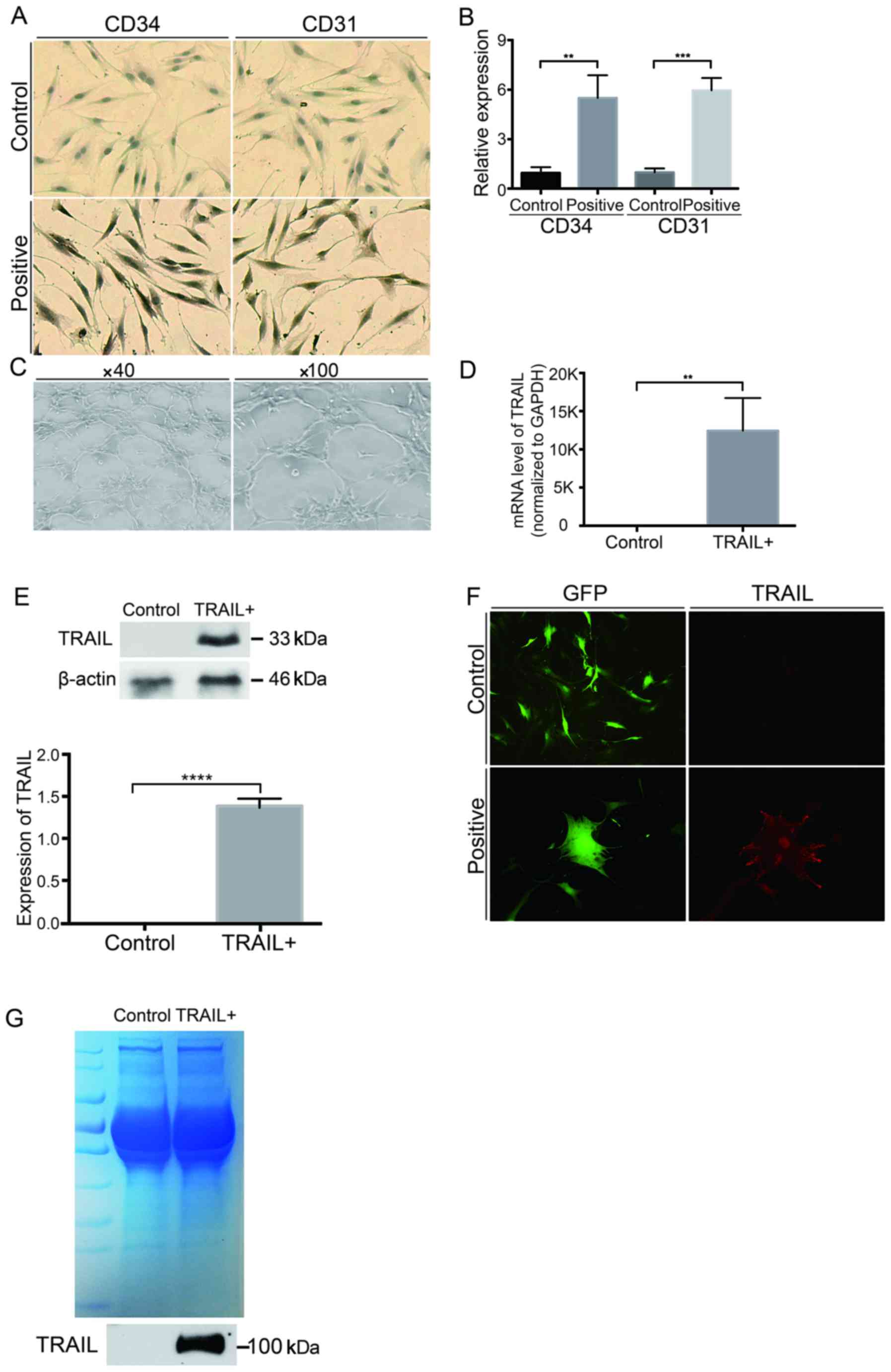

Blood cells were extracted from neonatal

Sprague-Dawley rats, and the specific surface markers CD31 and CD34

were detected by immunohistochemical analysis (27). Most cells revealed positive reactions

to CD31 and CD34 (Fig. 1A and B). The

angiogenic ability of EPCs was also identified. The cells

inoculated on the Matrigel surface formed tube-like structures

within 6 h, as shown in representative images (Fig. 1C). Thus, EPCs were isolated

successfully from the blood of neonatal rats.

| Figure 1.Construction of TRAIL-expressing

EPCs. (A and B) Immunocytochemical staining showed that the cells

were CD31 and CD34 positive (magnification, ×100) (P<0.05,

compared with the control group). (C) EPCs formed capillary-like

networks after being seeded onto the Matrigel surface for 6 h. (D

and E) EPCs were infected with lentiviruses encoding GFP or TRAIL.

The mRNA and protein levels of TRAIL in EPCs were determined using

qPCR (D) (P<0.05, compared with the control group) and western

blot analysis. β-Actin was used as a loading control (E, P<0.05,

compared with the control group). (F) EPCs harboring GFP showed

green fluorescence, and EPCs harboring TRAIL showed red

fluorescence (magnification, ×200). (G) The sTRAIL was detected

using western blot and Coomassie blue staining. Data are presented

as means ± SD. Three individual experiments were performed for each

group. **P<0.01, ***P<0.0001 and ****P<0.001, compared

with the control group. TRAIL, tumor necrosis factor-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand; EPCs, endothelial progenitor cells; GFP,

green fluorescent protein qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain

reaction; sTRAIL, soluble extracellular TRAIL; SD, standard

deviation. |

The isolated EPCs were infected and screened using

lentivirus encoding TRAIL. Then, the expression level of TRAIL on

EPCs was detected. Total mRNA was also extracted from both

TRAIL-transfected EPCs and negative controls. Quantitative PCR was

performed to quantify the mRNA levels. The TRAIL mRNA level in

infected EPCs significantly increased compared with the control

group (P<0.05) (Fig. 1D).

Furthermore, the TRAIL protein level was also enhanced, as

determined by western blot analysis (P<0.05) (Fig. 1E). The location of TRAIL was

determined by immunofluorescence staining. TRAIL was found to be

mainly expressed on the cell surface and partly in the cytoplasm

and nucleus (Fig. 1F). The soluble

extracellular TRAIL (sTRAIL) was also detected by western blot

analysis. It was found that the sTRAIL existed in the trimeric form

in the culture medium of the TRAIL-positive group (Fig. 1G). These results showed that TRAIL was

overexpressed in the EPCs after lentiviral transfection, and the

overexpressed TRAIL was further distributed both on the cell

membrane and in the culture medium.

Overexpression of TRAIL did not affect

the migration of EPCs toward SHG44 cells

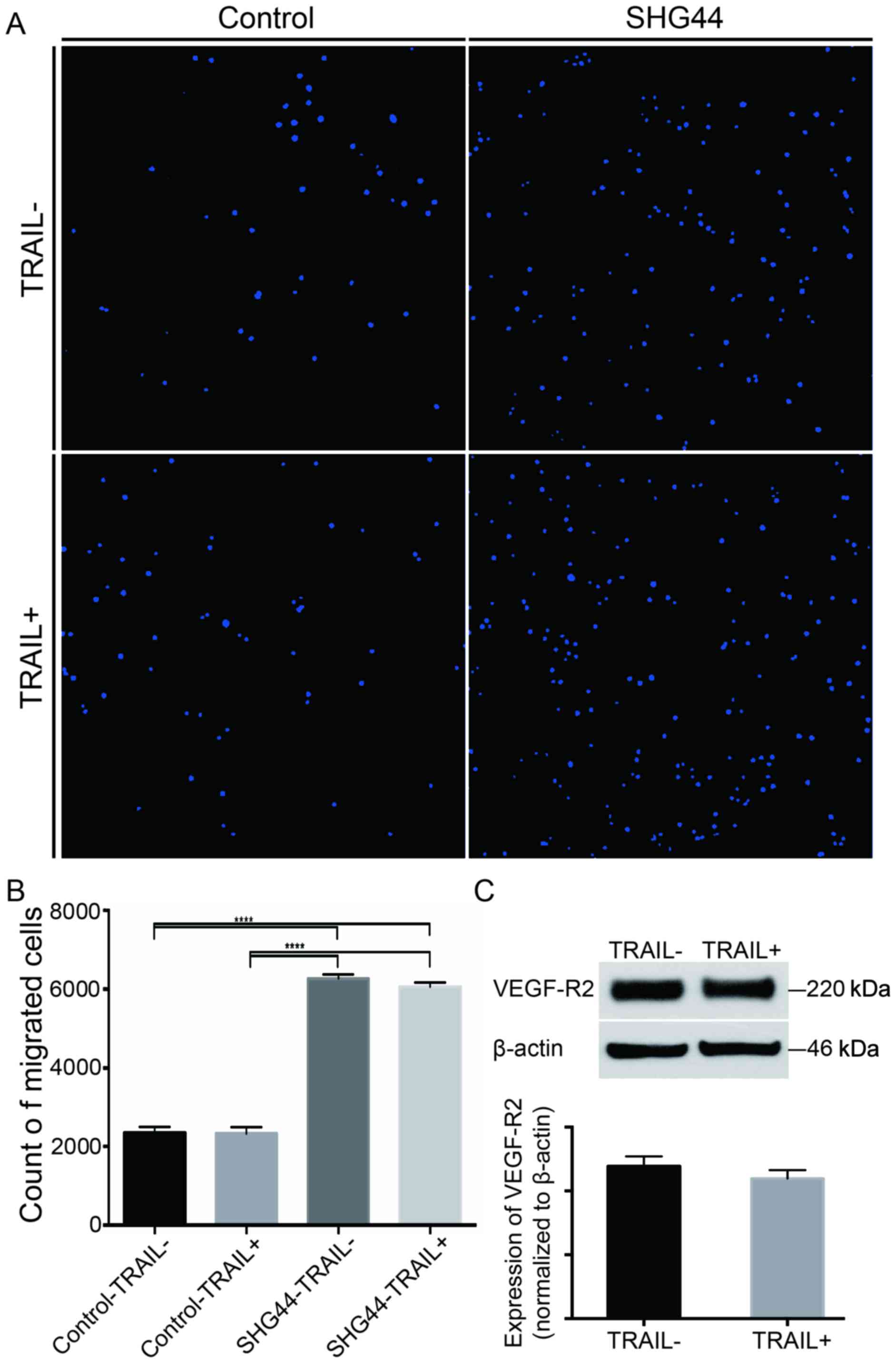

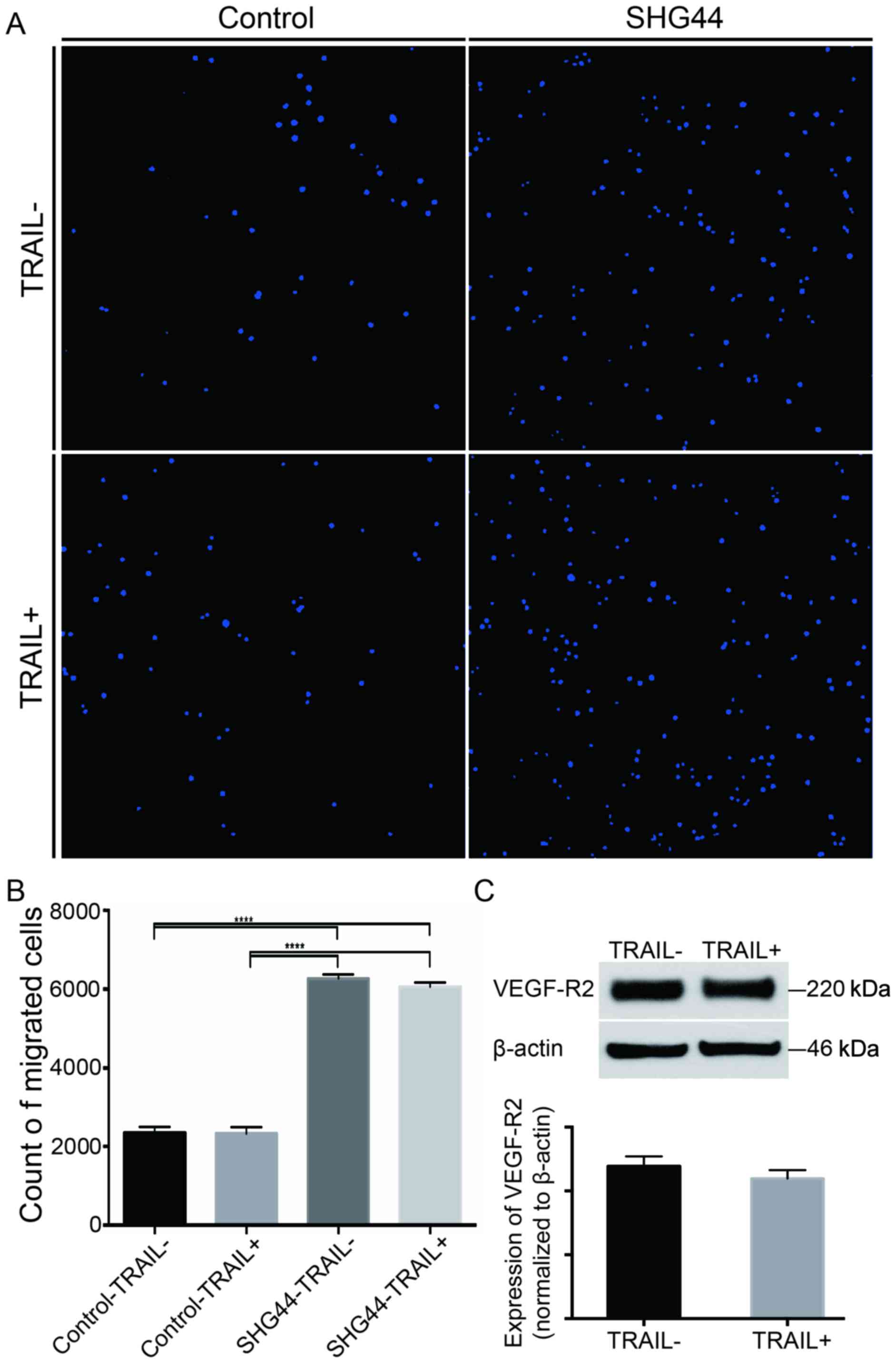

A Transwell migration assay was performed to assess

the directional migration of EPCs. The number of migrated cells

increased significantly when SHG44 cells were cultured in the lower

chamber, as evident from statistics and HCS of the images

(P<0.05) (Fig. 2A and B). However,

similar numbers of the migrated cells were found in the

TRAIL-transfected EPCs and controls, indicating that the

overexpression of TRAIL did not affect the homing of EPCs to SHG44

cells (P>0.05) (Fig. 2A and B).

Furthermore, the overexpression of TRAIL did not alter the protein

levels of VEGF-R2 in the TRAIL-transfected EPCs compared with the

controls (P>0.05) (Fig. 2C). These

findings indicated that EPCs with the overexpression of TRAIL had

the similar ability for directional migration and angiogenesis,

which could be used in the following experiments.

| Figure 2.Transwell migration assay of EPCs.

(A) Migrated EPCs were stained using DAPI, and images were obtained

using HCS of 25 continuous visual fields. (B) Numbers of migrated

cells were counted using HCS. The migrated EPCs increased obviously

when SHG44 cells were cultured in the lower chamber (magnification,

×100) (P<0.05, compared with the control group). No significant

difference was found between EPCs with or without the

overexpression of TRAIL (P>0.05). (C) Expression of VEGF-R2 on

control and TRAIL + EPCs. β-Actin was used as a loading control.

Data are presented as means ± SD. Three individual experiments were

performed for each group. ****P<0.0001, compared with the

control group. EPCs, endothelial progenitor cells; DAPI,

4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, HCS, high-content screening; SD,

standard deviation. |

Apoptosis of SHG44 in co-culture

system with EPCs

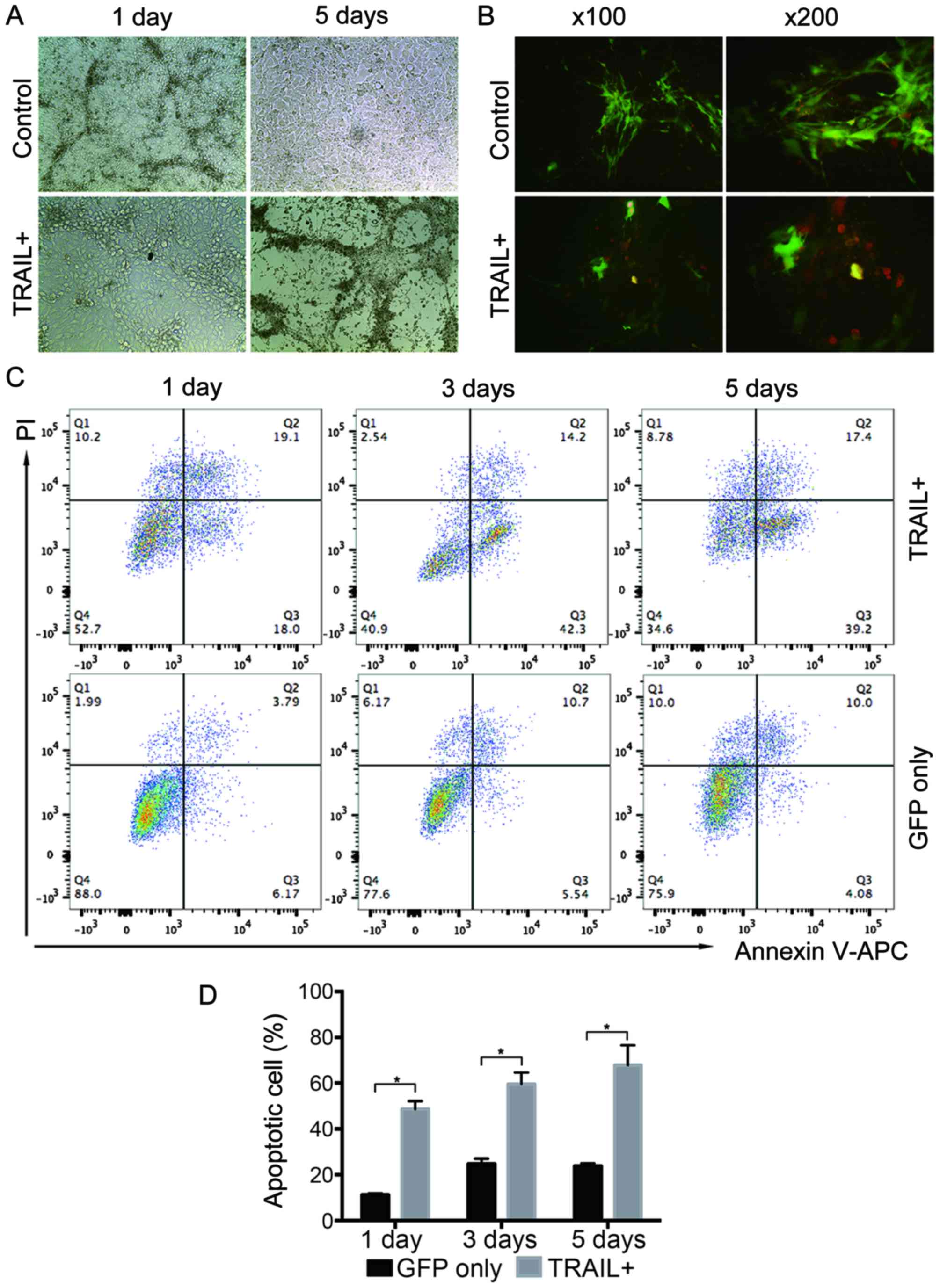

A co-culture system in which SHG44 cells were

co-cultured with EPCs harboring TRAIL or GFP was established to

determine the effect of TRAIL-overexpressing EPCs on SHG44 cells.

After 5 days of continuous observation, it was found that the

number of SHG44 cells in the TRAIL-expressing EPC-treated group

obviously reduced compared with that in the GFP-harboring EPCs

(Fig. 3A). Annexin V-kFluor594 was

used on the fifth day of co-culture to detect cell apoptosis. More

Annexin V-kFluor594-positive cells (red fluorescence) were found

around the TRAIL-expressing EPCs (green fluorescence) (Fig. 3B) in the TRAIL-expressing EPC-treated

group compared with the GFP group. It indicated that the

TRAIL-expressing EPCs could induce SHG44 cell apoptosis. Then, the

flow cytometry assay was used to measure the apoptotic rate of

SHG44 cells. The cells were collected and stained with Annexin

V-APC/PI on the first, third, and fifth days after co-culturing.

The apoptotic rate of SHG44 cells significantly increased by

co-culturing with the TRAIL-expressing EPCs, compared with that of

the cells harboring GFP, after separating EPCs and SHG44 cells

based on GFP fluorescence intensity, (Fig. 3C and D). These findings indicated that

TRAIL-positive EPCs could increase SHG44 cell apoptosis.

TRAIL bound with DR4/5 on glioma

cells

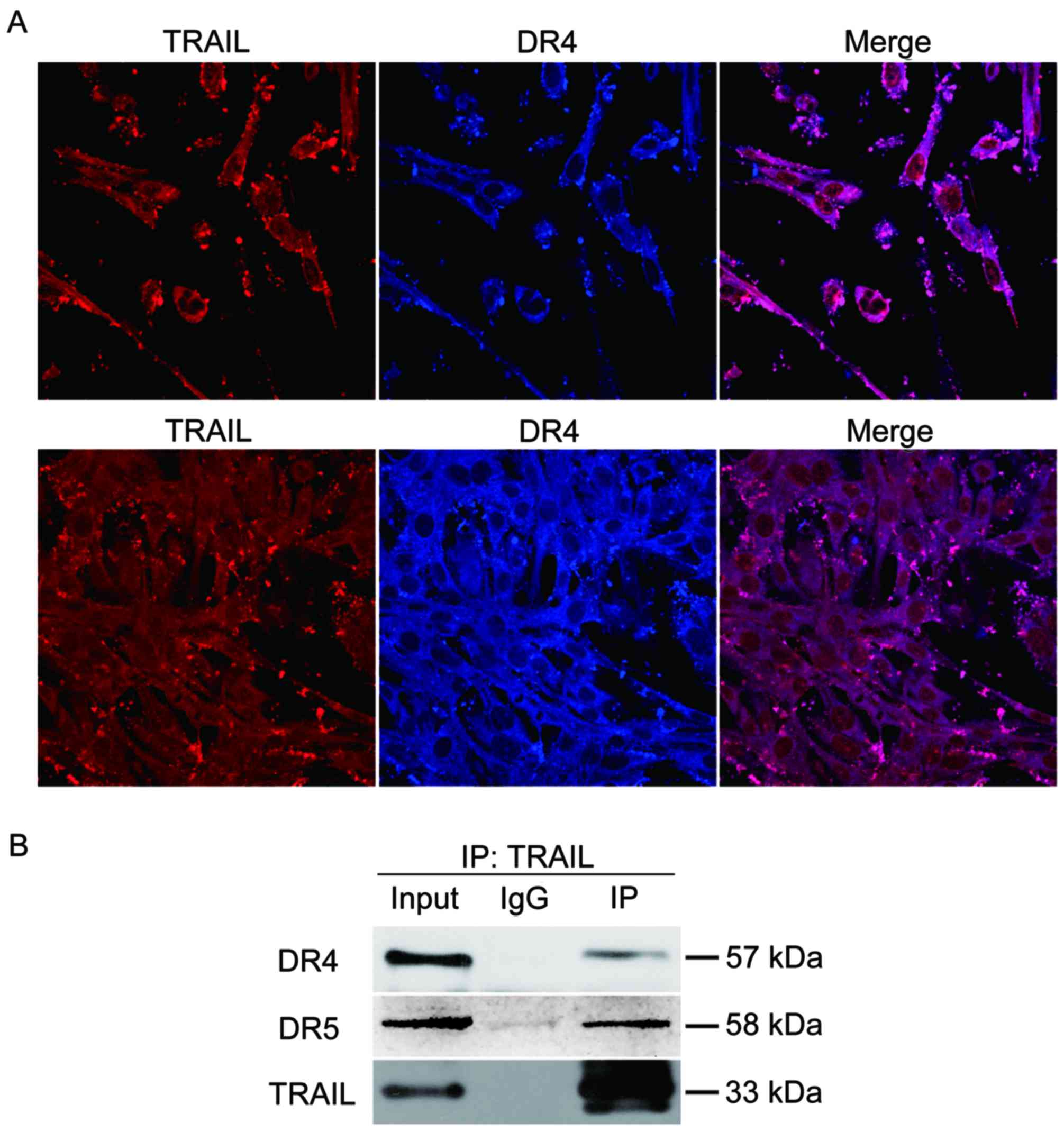

The study demonstrated that TRAIL-positive EPCs

could induce SHG44 cell apoptosis obviously. Next,

immunofluorescent co-localization and co-immunoprecipitation were

used to verify the interaction of TRAIL and death receptor so as to

explore the apoptotic mechanism further. Double-channel confocal

imaging revealed that TRAIL showed red fluorescence, TRAIL

co-localized with DR4 and DR5 (DR4 and DR5) showed blue

fluorescence (Fig. 4A). The total

proteins from the co-culture system were also extracted to test the

interaction between TRAIL and DR4/5 by immunoblotting. It was found

that TRAIL co-immunoprecipitated with DR4/5 in SHG44 cells

(Fig. 4B).

TRAIL enhanced the activation of

caspases and PARP

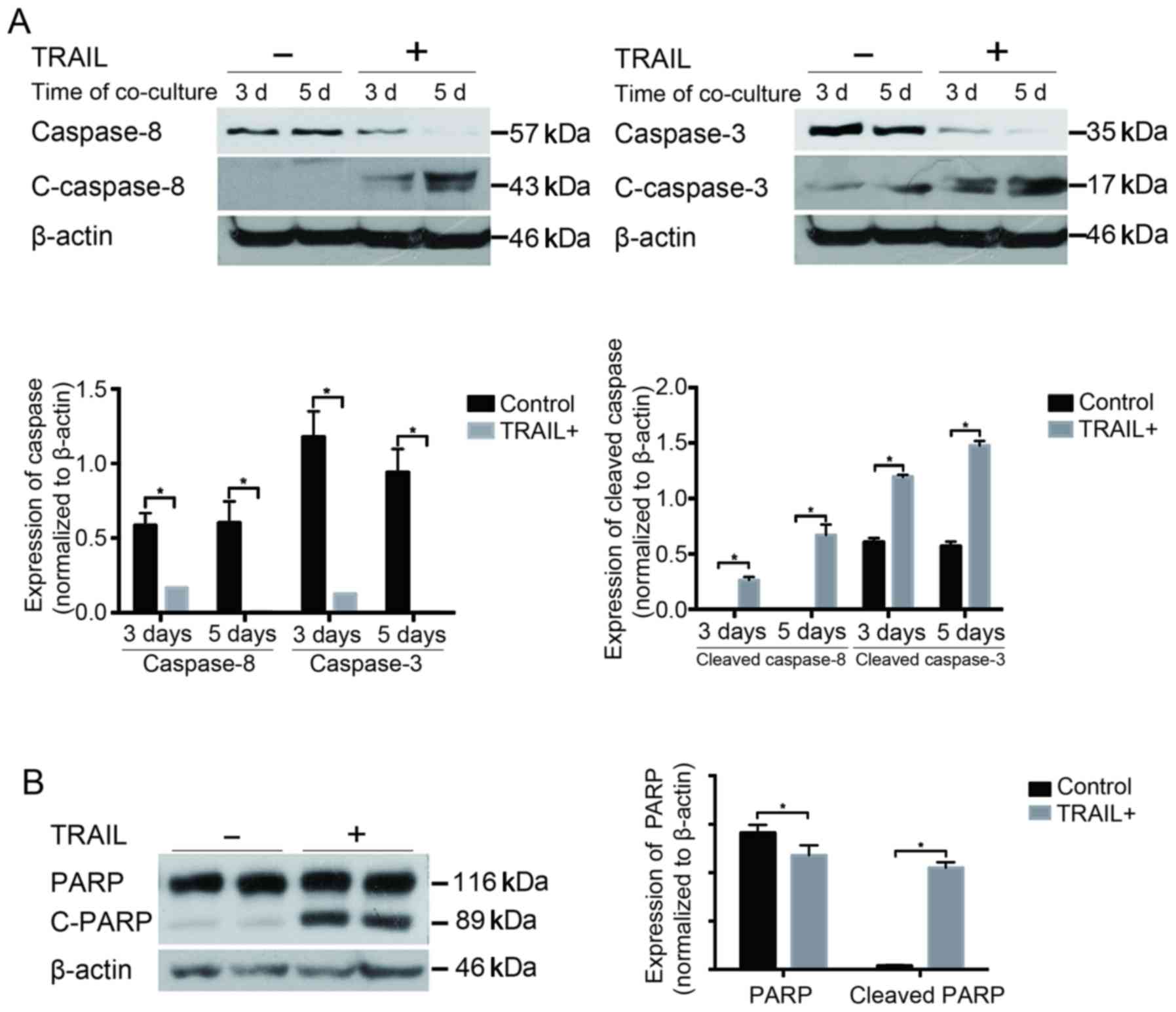

Next, the expression levels of pro/cleaved

caspase-8, pro/caspase-3, and PARP were examined. The expression

levels of cleaved caspase-8 and −3 significantly increased and were

further enhanced with time in the co-culture system, whereas the

expression levels of pro-caspase-8 and −3 decreased significantly,

compared with the GFP group (P<0.05) (Fig. 5A). Similar changes were observed in

the cleaved PARP. In contrast, the amount of full-length PARP was

much less in the TRAIL-positive group than in the GFP group

(P<0.05) (Fig. 5B), indicating

that PARP was largely activated under the effect of TRAIL on

EPCs.

Apoptosis in the co-culture system

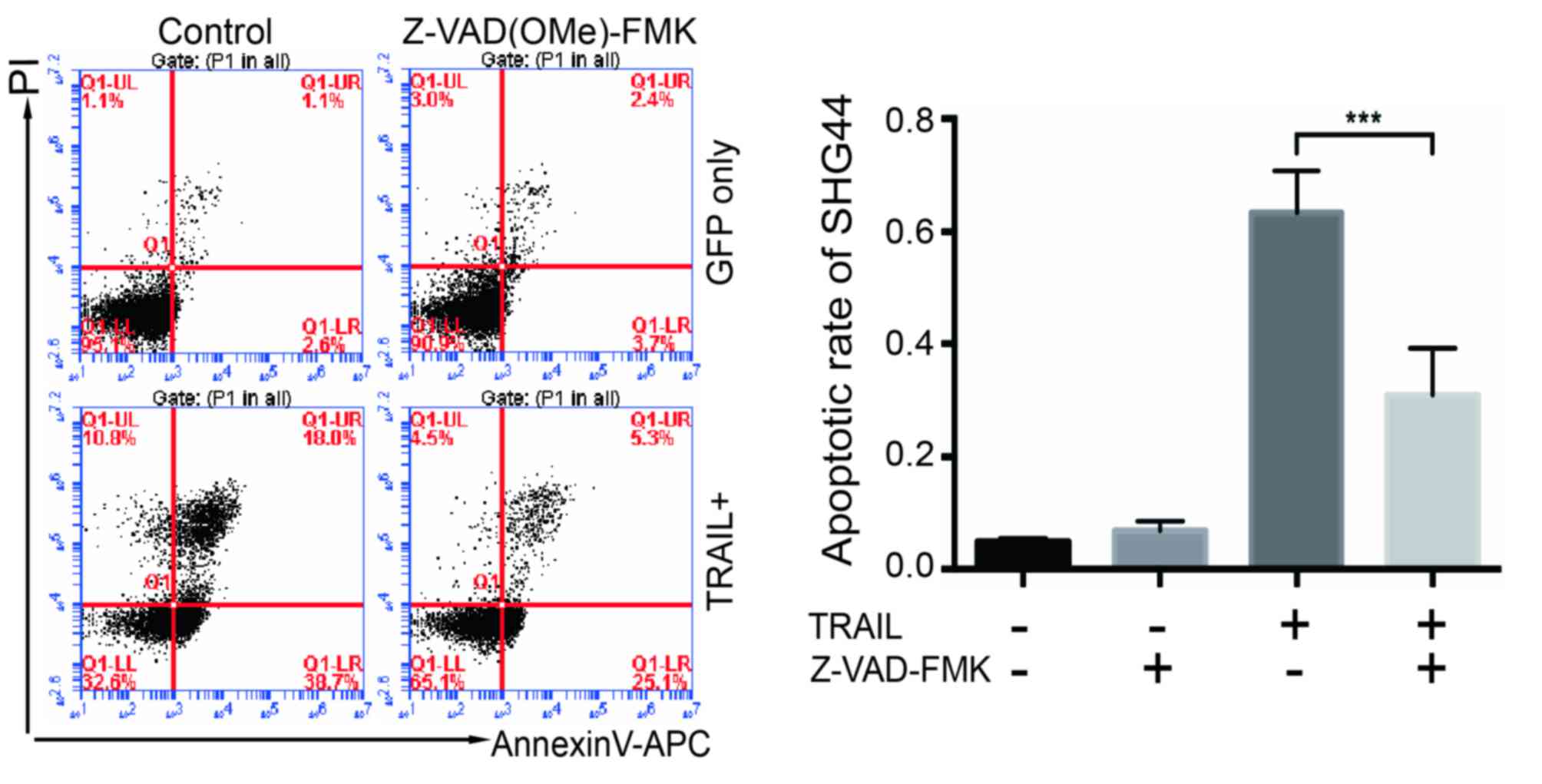

could be reversed by a caspase inhibitor

The caspase inhibitor Z-VAD(OMe)-FMK was used for 5

days of co-culture, and the apoptosis of SHG44 cells was detected

to verify the involvement of TRAIL-expressing EPCs further.

Fig. 6 shows that the apoptotic rate

was significantly reversed when Z-VAD(OMe)-FMK was added at the

concentration of 20 µmol/l (Fig.

6).

Discussion

Gliomas, the most common malignant tumors in CNS,

exhibit highly aggressive behavior. The therapeutic effect on

glioma is still not improved drastically despite various new

therapies reported for this tumor. In this study, the extracted

EPCs from the blood of neonatal Sprague-Dawley rats were identified

by detecting specific surface markers CD31 and CD34 as well as the

capability of vasculogenesis. TRAIL was found to increase the

apoptosis of SHG44 cells significantly. This trend could be

reversed by caspase-8 inhibitor. The mechanism underlying this

phenomenon might be related to the increased pro-apoptotic protein

levels of cleaved caspase-3, caspase-8, and PARP.

EPCs can self-proliferate and differentiate into the

endothelial lineage and express CD31, CD34, CD133, and VEGFR-2 on

their surface (28,29). They have the capability of

vasculogenesis and are involved in tumor vessel neogenesis. Many

studies investigated the relationship between EPCs and tumors

(22). Most previous studies focused

on anti-angiogenic treatment by suppressing the mobilization and

homing of EPCs to tumors (20). Only

a few studies used EPCs as a vector for treatment (21). EPCs harboring specific matrix

metallopeptidase-12 (MMP-12) could inhibit melanoma growth

(30). On the contrary, EPCs

releasing CD40 ligand could induce the increase in cleaved

caspase-3 and −7 in metastatic breast cancer (31). These findings proved that EPCs could

be used for tumor treatment. Growing evidence indicated that EPCs

could move across the BBB and home to brain tumors (23). EPCs can serve as a medium for

anti-glioma therapy. The Transwell assay indicated that EPCs had

the capability of homing to glioma cells, as previously reported.

The present study also proved that lentiviral infection had little

influence on the migration ability of EPCs. Therefore, it was

feasible to use the TRAIL-expressing EPCs as a therapeutic vector

after lentiviral infection.

TRAIL induces apoptosis through binding to DR4 or

DR5 on the surface of cells, recruiting and activating caspase-8

via the death domains of DRs and adaptor protein Fas-associated

death domain (FADD) (9,32). Activated caspase-8 cleaves

pro-caspase-3, inducing cell apoptosis (33,34). The

low bioavailability of TRAIL limits its application despite its

immense potential for anti-tumor therapy. Attempts were made to

address this limitation through enhancing the stability of TRAIL

(35–38) and concentrating TRAIL in the tumor

site (39–42). In this study, EPCs were used as a

vector for TRAIL, continuously producing TRAIL besides tumor cells.

The findings indicated that TRAIL delivered by EPCs could bind to

DR4 or DR5 on the surface of glioma cells. Correspondingly, the

activated caspase-8 and −3, and cleaved PARP increased obviously.

In other words, TRAIL-expressing EPCs could promote the apoptosis

of SHG44 cells through activating the death receptor pathway.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

TRAIL-overexpressing EPCs could migrate toward SHG44 cells and

induce apoptosis by activating the death receptor pathway. The

findings suggested that TRAIL and EPCs could be combined for glioma

therapy.

Acknowledgements

The present study is supported by the National

Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81100928) and the

Henan Medical Science Research Project (grant no. 2011020010). The

present study was supported by grants from the National Natural

Science Fund of China (no. 342600531547), the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (nos. 81270270 and 81470524, for WZ),

PhD Educational Award from the Ministry of Education (no.

20134101110013, for WZ), and the national Key R&D Program for

‘Key Projects’ from the Ministry of Science and Technology (no.

2016YFA0501800, for WZ).

References

|

1

|

Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Fulop J, Liu M,

Blanda R, Kromer C, Wolinsky Y, Kruchko C and Barnholtz-Sloan JS:

CBTRUS statistical report: Primary brain and central nervous system

tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2008–2012. Neuro Oncol. 4

17 Suppl:iv1–iv62. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wang X, Chen JX, Zhou Q, Liu YH, Mao Q,

You C, Chen N, Xiong L, Duan J and Liu L: Statistical report of

central nervous system tumors histologically diagnosed in the

Sichuan province of China from 2008 to 2013: A West China Glioma

Center report. Ann Surg Oncol. 23 Suppl 5:S946–S953. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lim B, Allen JE, Prabhu VV, Talekar MK,

Finnberg NK and El-Deiry WS: Targeting TRAIL in the treatment of

cancer: New developments. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 19:1171–1185.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Kichev A, Rousset CI, Baburamani AA,

Levison SW, Wood TL, Gressens P, Thornton C and Hagberg H: Tumor

necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) signaling

and cell death in the immature central nervous system after

hypoxia-ischemia and inflammation. J Biol Chem. 289:9430–9439.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Bo Y, Guo G and Yao W: MiRNA-mediated

tumor specific delivery of TRAIL reduced glioma growth. J

Neurooncol. 112:27–37. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Förster A, Falcone FH, Gibbs BF, Preussner

LM, Fiebig BS, Altunok H, Seeger JM, Cerny-Reiterer S, Rabenhorst

A, Papenfuss K, et al: Anti-Fas/CD95 and tumor necrosis

factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) differentially

regulate apoptosis in normal and neoplastic human basophils. Leuk

Lymphoma. 54:835–842. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Guo L, Fan L, Pang Z, Ren J, Ren Y, Li J,

Chen J, Wen Z and Jiang X: TRAIL and doxorubicin combination

enhances anti-glioblastoma effect based on passive tumor targeting

of liposomes. J Control Release. 154:93–102. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Gao JQ, Lv Q, Li LM, Tang XJ, Li FZ, Hu YL

and Han M: Glioma targeting and blood-brain barrier penetration by

dual-targeting doxorubincin liposomes. Biomaterials. 34:5628–5639.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Holoch PA and Griffith TS: TNF-related

apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL): A new path to anti-cancer

therapies. Eur J Pharmacol. 625:63–72. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Kelley SK and Ashkenazi A: Targeting death

receptors in cancer with Apo2L/TRAIL. Curr Opin Pharmacol.

4:333–339. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Bagci-Onder T, Agarwal A, Flusberg D,

Wanningen S, Sorger P and Shah K: Real-time imaging of the dynamics

of death receptors and therapeutics that overcome TRAIL resistance

in tumors. Oncogene. 32:2818–2827. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Perlstein B, Finniss SA, Miller C,

Okhrimenko H, Kazimirsky G, Cazacu S, Lee HK, Lemke N, Brodie S,

Umansky F, et al: TRAIL conjugated to nanoparticles exhibits

increased anti-tumor activities in glioma cells and glioma stem

cells in vitro and in vivo. Neuro Oncol. 15:29–40. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Redjal N, Zhu Y and Shah K: Combination of

systemic chemotherapy with local stem cell delivered S-TRAIL in

resected brain tumors. Stem Cells. 33:101–110. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Balyasnikova IV, Prasol MS, Ferguson SD,

Han Y, Ahmed AU, Gutova M, Tobias AL, Mustafi D, Rincón E, Zhang L,

et al: Intranasal delivery of mesenchymal stem cells significantly

extends survival of irradiated mice with experimental brain tumors.

Mol Ther. 22:140–148. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Choi SA, Yun JW, Joo KM, Lee JY, Kwak PA,

Lee YE, You JR, Kwon E, Kim WH, Wang KC, et al: Preclinical

biosafety evaluation of genetically modified human adipose

tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells for clinical applications to

brainstem glioma. Stem Cells Dev. 25:897–908. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Asahara T and Kawamoto A: Endothelial

progenitor cells for postnatal vasculogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell

Physiol. 287:C572–C579. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver

M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G and Isner JM:

Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for

angiogenesis. Science. 275:964–967. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Fang J, Chen X, Wang S, Xie T, Du X, Liu

H, Wang S, Li X, Chen J, Zhang B, et al: The expression of

P2X7 receptors in EPCs and their potential role in the

targeting of EPCs to brain gliomas. Cancer Biol Ther. 16:498–510.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Varma NR, Shankar A, Iskander A, Janic B,

Borin TF, Ali MM and Arbab AS: Differential biodistribution of

intravenously administered endothelial progenitor and cytotoxic

T-cells in rat bearing orthotopic human glioma. BMC Med Imaging.

13:172013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Flamini V, Jiang WG, Lane J and Cui YX:

Significance and therapeutic implications of endothelial progenitor

cells in angiogenic-mediated tumour metastasis. Crit Rev Oncol

Hematol. 100:177–189. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Marçola M and Rodrigues CE: Endothelial

progenitor cells in tumor angiogenesis: Another brick in the wall.

Stem Cells Int. 2015:8326492015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

de la Puente P, Muz B, Azab F and Azab AK:

Cell trafficking of endothelial progenitor cells in tumor

progression. Clin Cancer Res. 19:3360–3368. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Wang L, Chen L, Wang Q, Wang L, Wang H,

Shen Y, Li X, Fu Y, Shen Y and Yu Y: Circulating endothelial

progenitor cells are involved in VEGFR-2-related endothelial

differentiation in glioma. Oncol Rep. 32:2007–2014. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Zhang SH, Xiang P, Wang HY, Lu YY, Luo YL

and Jiang H: The characteristics of bone marrow-derived endothelial

progenitor cells and their effect on glioma. Cancer Cell Int.

12:322012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Kang SD, Carlon TA, Jantzen AE, Lin FH,

Ley MM, Allen JD, Stabler TV, Haley NR, Truskey GA and Achneck HE:

Isolation of functional human endothelial cells from small volumes

of umbilical cord blood. Ann Biomed Eng. 41:2181–2192. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Zhao W, Waggoner J, Zhang ZG, Lam CK, Han

P, Qian J, Schroder PM, Mitton B, Kontrogianni-Konstantopoulos A,

Robia SL and Kranias EG: The anti-apoptotic protein HAX-1 is a

regulator of cardiac function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 106:pp.

20776–20781. 2009; View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Huang G, Tao L, Shen S and Chen L: Hypoxia

induced CCL28 promotes angiogenesis in lung adenocarcinoma by

targeting CCR3 on endothelial cells. Sci Rep. 6:271522016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Peichev M, Naiyer AJ, Pereira D, Zhu Z,

Lane WJ, Williams M, Oz MC, Hicklin DJ, Witte L, Moore MA and Rafii

S: Expression of VEGFR-2 and AC133 by circulating human CD34(+)

cells identifies a population of functional endothelial precursors.

Blood. 95:952–958. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Fadini GP, Losordo D and Dimmeler S:

Critical reevaluation of endothelial progenitor cell phenotypes for

therapeutic and diagnostic use. Circ Res. 110:624–637. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Laurenzana A, Biagioni A, D'Alessio S,

Bianchini F, Chillà A, Margheri F, Luciani C, Mazzanti B,

Pimpinelli N, Torre E, et al: Melanoma cell therapy: Endothelial

progenitor cells as shuttle of the MMP12 uPAR-degrading enzyme.

Oncotarget. 5:3711–3727. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Purwanti YI, Chen C, Lam DH, Wu C, Zeng J,

Fan W and Wang S: Antitumor effects of CD40 ligand-expressing

endothelial progenitor cells derived from human induced pluripotent

stem cells in a metastatic breast cancer model. Stem Cells Transl

Med. 3:923–935. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

de Miguel D, Lemke J, Anel A, Walczak H

and Martinez-Lostao L: Onto better TRAILs for cancer treatment.

Cell Death Differ. 23:733–747. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ozören N and El-Deiry WS: Defining

characteristics of Types I and II apoptotic cells in response to

TRAIL. Neoplasia. 4:551–557. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Rudner J, Jendrossek V, Lauber K, Daniel

PT, Wesselborg S and Belka C: Type I and type II reactions in

TRAIL-induced apoptosis-results from dose-response studies.

Oncogene. 24:130–140. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Rozanov DV, Savinov AY, Golubkov VS,

Rozanova OL, Postnova TI, Sergienko EA, Vasile S, Aleshin AE, Rega

MF, Pellecchia M and Strongin AY: Engineering a leucine

zipper-TRAIL homotrimer with improved cytotoxicity in tumor cells.

Mol Cancer Ther. 8:1515–1525. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Berg D, Lehne M, Müller N, Siegmund D,

Münkel S, Sebald W, Pfizenmaier K and Wajant H: Enforced covalent

trimerization increases the activity of the TNF ligand family

members TRAIL and CD95L. Cell Death Differ. 14:2021–2034. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Schneider B, Münkel S,

Krippner-Heidenreich A, Grunwald I, Wels WS, Wajant H, Pfizenmaier

K and Gerspach J: Potent antitumoral activity of TRAIL through

generation of tumor-targeted single-chain fusion proteins. Cell

Death Dis. 1:e682010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Siegemund M, Pollak N, Seifert O, Wahl K,

Hanak K, Vogel A, Nussler AK, Göttsch D, Münkel S, Bantel H, et al:

Superior antitumoral activity of dimerized targeted single-chain

TRAIL fusion proteins under retention of tumor selectivity. Cell

Death Dis. 3:e2952012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Mitchell MJ, Wayne E, Rana K, Schaffer CB

and King MR: TRAIL-coated leukocytes that kill cancer cells in the

circulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 111:pp. 930–935. 2014;

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Loi M, Becherini P, Emionite L, Giacomini

A, Cossu I, Destefanis E, Brignole C, Di Paolo D, Piaggio F, Perri

P, et al: sTRAIL coupled to liposomes improves its pharmacokinetic

profile and overcomes neuroblastoma tumour resistance in

combination with Bortezomib. J Control Release. 192:157–166. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Yan C, Li S, Li Z, Peng H, Yuan X, Jiang

L, Zhang Y, Fan D, Hu X, Yang M and Xiong D: Human umbilical cord

mesenchymal stem cells as vehicles of CD20-specific TRAIL fusion

protein delivery: A double-target therapy against non-Hodgkin's

lymphoma. Mol Pharm. 10:142–151. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Seifert O, Pollak N, Nusser A, Steiniger

F, Rüger R, Pfizenmaier K and Kontermann RE: Immuno-LipoTRAIL:

Targeted delivery of TRAIL-functionalized liposomal nanoparticles.

Bioconjug Chem. 25:879–887. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|