Introduction

Synthetic sickness/lethality interaction is a highly

attractive strategy for cancer therapy (1–4). For

example, in cancer cells with a KRAS gene mutation, the

inhibition of polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1) resulted in cell death

(5). Similarly, cancer cells with

the KRAS mutation were sensitive to the suppression of the

serine/threonine kinase STK33 (6).

Moreover, dysfunction of DNA double-strand break repair caused by

mutations in BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene sensitized cells to

the inhibition of poly-ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) enzymatic

activity, resulting in chromosomal instability, cell cycle arrest,

and subsequent apoptosis (7). This

concept had been proved by a phase II trial where olaparib, a PARP

inhibitor, provided objective antitumor activity in patients with a

BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation (8).

TP53 is the most commonly mutated tumor

suppressor gene in several different types of human cancer

(9). TP53 encodes the 393

amino acid p53 protein, which binds to specific DNA sequences in

the regulatory region of downstream genes (10). A variety of cellular stressors

including ultraviolet rays, ionizing radiation, chemotherapeutic

drugs, and hypoxia stabilize the p53 protein, and

post-translational modifications activate it; this results in

various cellular responses including cell cycle arrest, DNA repair

and apoptosis (11,12).

According to the TP53 mutation databases,

~75% of the mutations are missense mutations (13,14);

to date, >1,200 distinct missense mutations have been reported.

Among them, those at residues Arg175(R175),

Gly245(G245), Arg248(R248),

Arg249(R249), Arg273(R273) and

Arg282(R282) have been reported most frequently

(15). The most common p53 mutant

proteins caused by TP53 hot-spot mutations are R175H, G245S,

R248W, R248Q, R249S and R273H; these mutations cause a loss of the

trans-activation function of downstream genes (16). However, some p53 mutants gain new

functions that are not observed in wild-type p53 (so called

gain-of-function mutations). For example, mice with the knock-in

mutant p53 R172H and R270H, which correspond to human p53 R175H and

R273H mutations, develop a variety of novel tumors such as lung

adenocarcinoma, renal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and

intestinal carcinoma which are not generally observed in

TP53-null mice (17). In

addition, embryonic fibroblasts derived from p53 R172H knock-in

mice gained activities of cell proliferation, DNA synthesis and

retroviral transformation (18).

Moreover, human p53 R273H or R248W interacted with Mre11 and

suppressed the binding of the Mre11-Ras50-NBS1 (MRN) complex to DNA

double-strand breaks, resulting in the chromosomal translocation

and abrogation of the G2/M check point (19). According to these results, it has

been hypothesized that some p53 mutant proteins, such as the

activated K-ras protein, are oncogenic and contribute to

carcinogenesis and cancer progression.

In the present study, we conducted high-throughput

RNAi screening by a lentiviral gene suppression system to identify

synthetic sick/lethal genes in the presence of p53 R175H, which

accounts for ~6% of the missense mutations identified in human

cancer (20). As a result, we

identified that inhibitor of differentiation 1 (ID1) is the

first gene that causes synthetic sickness when paired with p53

R175H mutant protein.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and culture

The stable SF126 cell line expressing the

doxycycline (Dox)-inducible p53 R175H mutant (SF126-tet-R175H) was

constructed according to the protocol described previously

(21). In addition, SF126-tet-TON,

which does not express p53, was used as a control (21). Mutant p53 was induced with 10 ng/ml

doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Five human cell

lines including SKBr3 and HCC1395 (both derived from breast

cancer), VMRC-LCD (derived from lung cancer), Detroit 562 (derived

from head and neck cancer), and LS123 (derived from colon cancer)

express p53 R175H endogenously. Colon cancer cell lines HT-29 and

SW480 express p53 R273H endogenously. HCT116 (derived from colon

cancer) expressed wild-type p53 endogenously. Four cell lines

including PC3 (derived from prostate cancer), H1299 and Calu-1

(both derived from lung cancer), and SK-N-MC (derived from

neuroblastomas) are TP53-null. PC3 was purchased from Cell

Research Center for Biomedical Research, Institute of Development,

Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University (Sendai, Japan). SKBr3,

HCC1395, LS123, H1299, Calu-1, SK-N-MC, HCT116 and SW480 were

purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas,

VA, USA). Detroit 562 and VMRC-LCD were purchased from DS Farma

Biomedical (Osaka, Japan) and Human Science Research Resources Bank

(Tokyo, Japan), respectively. HT-29 was a gift from Dr John M.

Mariadason. SKBr3, HCC1395, HT-29, SW480, H1299 and PC3 were

cultured in RPMI-1640, and LS123, Calu-1, SK-N-MC, Detroit 562 and

VMRC-LCD were cultured in minimum essential medium with 10% FBS at

37°C. The identity of SF126, PC3, HCC1395, LS123, H1299, Detroit

562, VMRC-LCD and HT-29 cells was tested using a set of 10 short

tandem repeats produced by BEX Co., Ltd (Tokyo, Japan) in 2011.

SKBr3, Calu-1, SK-N-MC, SW480, and HCT116 were passaged for <6

months.

Mammalian p53 expression vectors

To express p53 R175H mutant, the p53 expression

vectors pCR259-R175H and pCR259 were used (16,22).

Each plasmid was transfected into TP53-null cells using

Effectene Transfection Reagent (Qiagen, Hercules, CA, USA),

following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Expression of p53

R175H was confirmed by western blot analysis.

RNAi screening

One million SF126-tet-R175H and SF126-tet-TON cells

were seeded in 10-cm culture plates for 24 h. The medium was

removed from the plates and the Decode RNAi Viral Screening Library

(Thermo Scientific Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA) was added

to the plate at the multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.3 with

serum-free medium. After 6 h, the medium was replaced with

virus-free medium. After 48 h, puromycin was added at a final

concentration of 2 mg/ml to select the infected cells. Finally,

7×106 of lentivirus-infected SF126-tet-R175H and

SF126-tet-TON cells were obtained. These cells theoretically

contain 70,000 distinct shRNAs, and each cell should express a

single shRNA product. These cells were divided into 2 groups, and

each group was cultured with or without doxycycline for 10 days.

Genomic DNA was extracted from each group using the Blood &

Cell Culture DNA Mini kit (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer’s

recommendation. Barcode sequences corresponding to specific shRNAs

were amplified by the following primers located outside the barcode

sequence: forward, 5′-caaggggctactttaggagcaattatcttg-3′ and

reverse, 5′-ggttgattgttccagacgcgt-3′.

Amplified PCR products were separated in 1.5% TAE

agarose gel and extracted using Wizard SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up

system (Promega Corporation, Madison WI, USA). Each purified PCR

product was labeled with Cy5 (doxycycline-on group) or Cy3

(doxycycline-off group) using Agilent’s Genomic DNA Labeling kit

(Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) and was

hybridized on the barcode microarray in the hybridization oven at

65°C for 17 h. After hybridization, the arrays were scanned with

the Agilent DNA microarray scanner to quantify log2

Cy5/Cy3. The ‘log2 Cy5/Cy3’ indicates increase and decrease of

cells in the primary screening and negative value of ‘log2 Cy5/Cy3’

shows that the counts of R175H expressing cells (dyed with Cy5) is

smaller than the counts of R175H unexpressed cells (dyed with Cy3).

We conducted 2 independent experiments, and obtained 3 independent

values of log2 Cy5/Cy3 were analyzed by Student’s t-test. Candidate

genes were identified after analyzing raw data for each shRNA using

the Gene Spring software (Agilent Technologies). Microarray data

were deposited in GEO (accession no. 33362).

Knockdown analysis of candidate genes

using siRNA

The siRNAs of 50 candidate genes, identified from

primary screening, were synthesized by Hokkaido System Science

(Hokkaido, Japan). The sequences of synthesized siRNA for candidate

genes are listed in Table I.

ID1-2 siRNA was synthesized as described previously

(23). TP53 siRNA was

purchased from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA), and

TP53-2 siRNA was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology,

Inc. (Boston, MA, USA). A total of 3.5–5.0×103

cells/well were seeded and incubated in a 96-well plate for 24 h.

Each candidate siRNA and negative control siRNA was added to the

cells to make a final concentration of 30 nM or 100 nM using

DharmaFECT 1 (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO, USA). Cell proliferation

assays were performed using Cell Counting kit-8 (Dojin

Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan), as previously described (21).

| Table ISequences of synthesized siRNA for 50

candidate genes. |

Table I

Sequences of synthesized siRNA for 50

candidate genes.

| Gene symbol | siRNA sense

sequence | siRNA antisense

sequence |

|---|

| Smallest

p-value |

| UROS |

CCTCTGTGGAAGCCAGCTTAA |

TTAAGCTGGCTTCCACAGAGG |

| GYPC |

GCTCAGAACGATTGGAAATAA |

TTATTTCCAATCGTTCTGAGC |

|

PRO1596 |

CGATGAATATCTCTGTGAATA |

TATTCACAGAGATATTCATCG |

| CD69 |

GGAGCATTTATAAATGGACAA |

TTGTCCATTTATAAATGCTCC |

| PDXP |

GGTACCAGTTTAGGTTCCTAA |

TTAGGAACCTAAACTGGTACC |

| THADA |

CGCTTACAGATGATTCTGAAT |

ATTCAGAATCATCTGTAAGCG |

| KCNJ10 |

GCAGATATCTTGGCCTGGTTA |

TAACCAGGCCAAGATATCTGC |

| ABCA12 |

CCAAATTTCCTCCAACTGCAA |

TTGCAGTTGGAGGAAATTTGG |

| UBA6 |

GCATTGTTACTTGCCTTGAAA |

TTTCAAGGCAAGTAACAATGC |

| CDC7 |

GCACTTTCAGCTCTGTTTATT |

AATAAACAGAGCTGAAAGTGC |

| ID1 |

GGAAATTGCTTTGTATTGTAT |

ATACAATACAAAGCAATTTCC |

| CTBS |

GGCTCCTTATTATAACTATAA |

TTATAGTTATAATAAGGAGCC |

| EIF2B3 |

CGGAGTGAACTGATTCCATAT |

ATATGGAATCAGTTCACTCCG |

| UFM1 |

GGTAGCAAAGTGTTACAGAAA |

TTTCTGTAACACTTTGCTACC |

| PTCD1 |

CCTCGATGTGTTCAAGGAAAT |

ATTTCCTTGAACACATCGAGG |

| TPCN2 |

GGAGCTCCTGTTCAGGGATAT |

ATATCCCTGAACAGGAGCTCC |

| NEURL |

GGGTAACAACTTCTCCAGTAT |

ATACTGGAGAAGTTGTTACCC |

| STEAP4 |

GCACTATATTAGGTTAAGTAT |

ATACTTAACCTAATATAGTGC |

|

C19orf40 |

GCATATTGTGGCCAATGAGAA |

TTCTCATTGGCCACAATATGC |

|

C19orf38 |

CCACCTTGGATGATCACTCAG |

CTGAGTGATCATCCAAGGTGG |

|

C14orf37 |

GGAACTCCTTACAAGCACTAA |

TTAGTGCTTGTAAGGAGTTCC |

| Largest

fold-change |

|

MGC42105 |

CCAGCTGACGCCCTTCGAGAA |

TTCTCGAAGGGCGTCAGCTGG |

| GP6 |

GGGCTCCAGACGGATCTCTAA |

TTAGAGATCCGTCTGGAGCCC |

|

BCL2L14 |

GCCTGTAGCTTCAAGTTCTAA |

TTAGAACTTGAAGCTACAGGC |

| HILS1 |

GCCAAGTGCCACTGCAATTAA |

TTAATTGCAGTGGCACTTGGC |

| CLDND2 |

GAAGAATGCGTGGAAGAACAA |

TTGTTCTTCCACGCATTCTTC |

| UMOD |

CCACTGACACCTCAGAAGCAA |

TTGCTTCTGAGGTGTCAGTGG |

| RHAG |

GGGCATATTCTTTGAGTTATA |

TATAACTCAAAGAATATGCCC |

| GFPT2 |

GCTACGAGTTTGAGTCAGAAA |

TTTCTGACTCAAACTCGTAGC |

| SATL1 |

AAGCATGGATTACTTTCAAAT |

ATTTGAAAGTAATCCATGCTT |

|

RTN4IP1 |

GCTGCCAGTGTAAATCCTATA |

TATAGGATTTACACTGGCAGC |

| DOK7 |

CCAAGCGGATTCATCTTTGAA |

TTCAAAGATGAATCCGCTTGG |

| NUP98 |

GGCCAAAGGCTTTACAAACAA |

TTGTTTGTAAAGCCTTTGGCC |

| PWWP2A |

GCCATGCCGCTCCAAAGTAAT |

ATTACTTTGGAGCGGCATGGC |

| MEP1A |

GCCTATAAGGCCATCATAGAA |

TTCTATGATGGCCTTATAGGC |

| CCT6B |

TGGCTGAAGCTCTTGTTACAT |

ATGTAACAAGAGCTTCAGCCA |

| PDXP |

GGTACCAGTTTAGGTTCCTAA |

TTAGGAACCTAAACTGGTACC |

| ZNF300 |

GCTAATATTAGCTTGTCATAA |

TTATGACAAGCTAATATTAGC |

|

DEFB125 |

AGAGGATATAACATTGGATTA |

TAATCCAATGTTATATCCTCT |

| GJA5 |

CGTTGCTCATTAATTCTAGAA |

TTCTAGAATTAATGAGCAACG |

| EFNA4 |

CCATGTTCAATTCTCAGAGAA |

TTCTCTGAGAATTGAACATGG |

| Double entry |

| NMNAT1 |

TCATCTGAAGTGTCACGTAAA |

TTTACGTGACACTTCAGATGA |

| KLHL10 |

GCTGAGTACTTCATGAACAAT |

ATTGTTCATGAAGTACTCAGC |

| LMLN |

CCACAGTGAAACATGAGGTTA |

TAACCTCATGTTTCACTGTGG |

| FBXO22 |

TCCCTCAAATTGAAGGAATAA |

TTATTCCTTCAATTTGAGGGA |

| ITGB7 |

GGACAGTAATCCTCTCTACAA |

TTGTAGAGAGGATTACTGTCC |

| CPN1 |

GGAATGCAAGACTTTAATTAT |

ATAATTAAAGTCTTGCATTCC |

| COLQ |

GGCTACAATGCTCTTCCTCTT |

AAGAGGAAGAGCATTGTAGCC |

| AP3B2 |

GGATTGCACCTGATGTCTTAA |

TTAAGACATCAGGTGCAATCC |

| ANXA11 |

CGTGGTGAAATGTCTCAAGAA |

TTCTTGAGACATTTCACCACG |

Western blot analysis

Cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer

containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, and 1%

protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysate was

subjected to western blot analysis, as previously described

(24). Anti-p53 (Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA, USA), anti-β-actin

(Sigma-Aldrich), anti-Id1, and anti-GAPDH (Applied Biosystems)

antibodies were used.

Cell cycle analysis by FACS

A total of 1.5×104 cells/plate were

seeded and incubated in 6-cm culture plates for 24 h. The cells

were further incubated in the presence of drugs for 48 h. These

cells were collected, and FACS analysis was performed, as

previously described (24).

Results

Screening of synthetic lethal genes that

interact with p53 R175H mutant

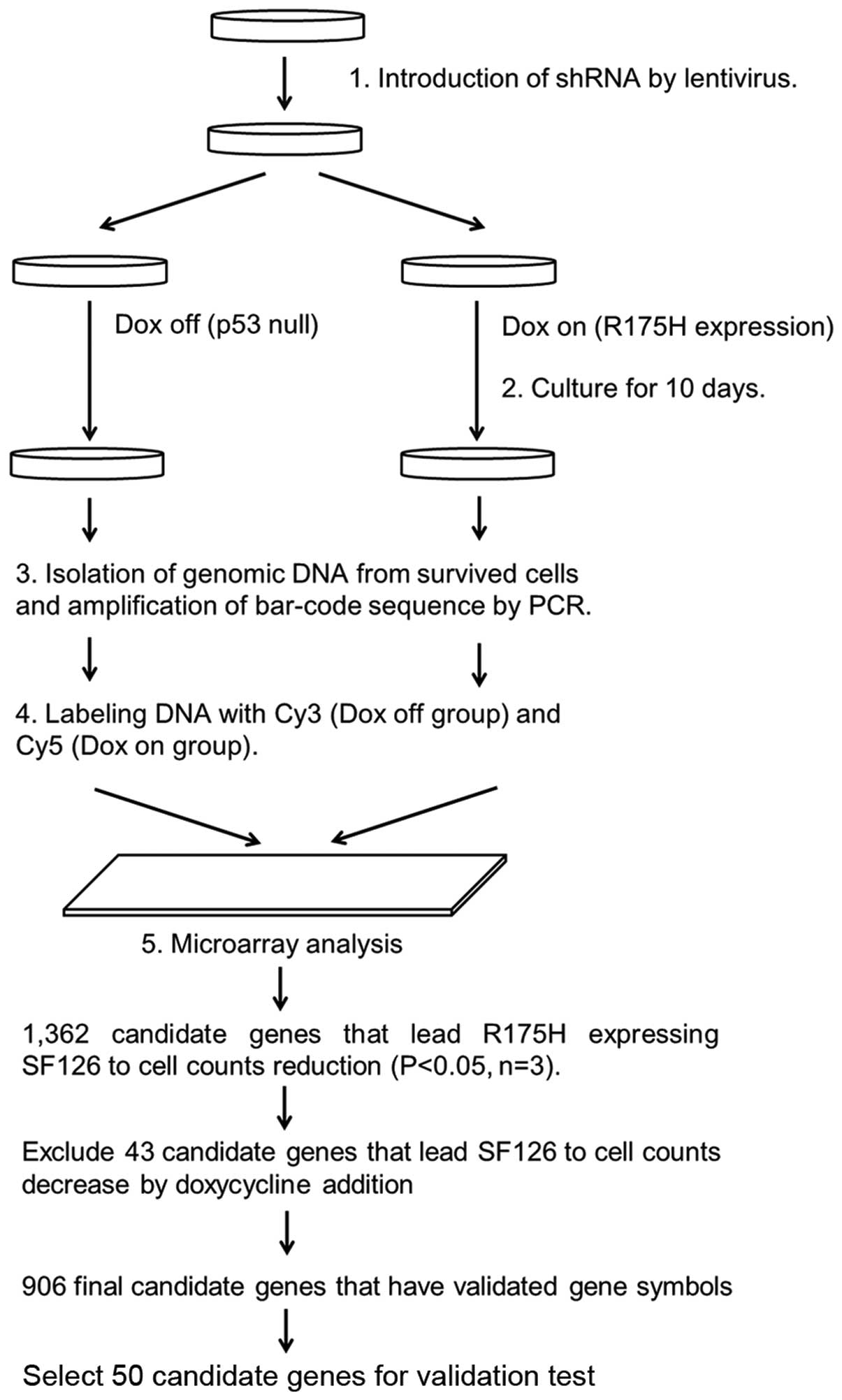

A flow chart of the high-throughput screening of

synthetic lethal genes interacting with p53 R175H is shown in

Fig. 1. By comparative analysis,

1,362 candidate genes were identified for synthetic lethality with

p53 R175H expression in the SF126-tet-R175H cell line (p<0.05

according to t-test, n=3). Among these, 43 were excluded as

suppression of these genes also resulted in decreasing cell numbers

in SF126-tet-TON cells after doxycycline treatments (no R175H

expression). In the remaining 1,319 genes, 906 genes have validated

gene symbols, which have p-value <0.05. Among these, we selected

50 genes (21 genes from the group with the smallest p-values, 20

genes from the group with the largest fold-change, and 9 genes

reproduced by different siRNA sequences) for further validation

testing (Table I).

Suppression of candidate genes by siRNA

in p53 R175H expressing cell lines and TP53-null cell lines

To investigate whether the suppression of candidate

genes by siRNA resulted in p53 R175H-dependent inhibition of cell

growth, candidate gene siRNAs were transfected into cell lines

expressing endogenous p53 R175H (SKBr3, LS123, HCC1395, Detroit 562

and VMRC-LCD) and TP53-null cells (PC3, H1299, SK-N-MC and

Calu-1). We obtained the ratio of cell growth inhibition of

candidate gene siRNA transfected cells for negative control siRNA

transfected cells on day 4. In 50 candidate genes, suppression of

GYPC, NUP98, GP6, EFNA4 and ID1 by siRNA

significantly decreased the number of p53 R175H expressing cells

compared with TP53-null cells (t-test) (Table II).

| Table IITop 5 candidate genes for synthetic

lethal interaction with R175H on t-test. |

Table II

Top 5 candidate genes for synthetic

lethal interaction with R175H on t-test.

| Gene symbol | p-value |

|---|

| GYPC | 0.002446 |

| NUP98 | 0.029324 |

| GP-6 | 0.043416 |

| EFNA4 | 0.055412 |

| ID1 | 0.061552 |

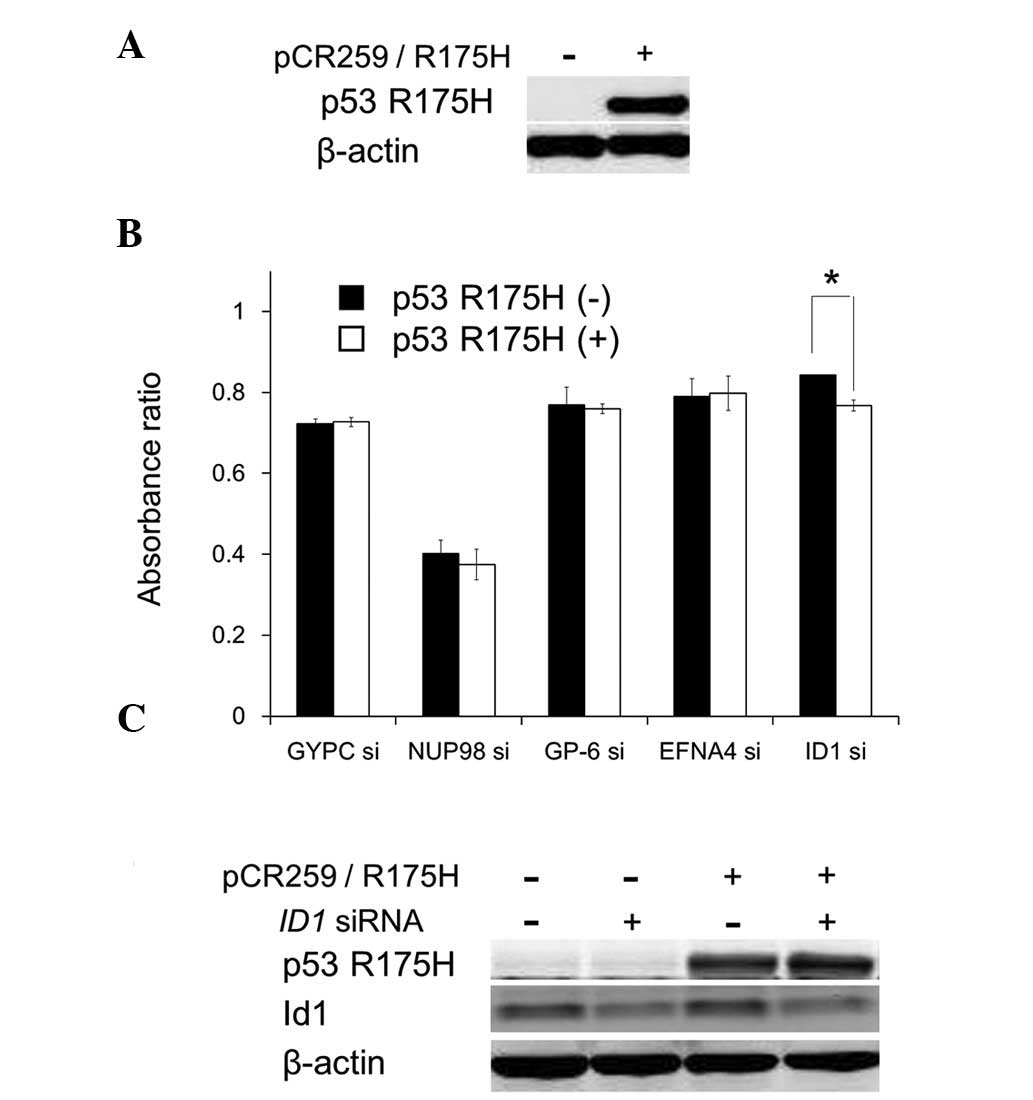

To examine whether the cell growth inhibition

resulting from suppression of the candidate genes depends on p53

R175H expression, GYPC, NUP98, GP6, EFNA4 and ID1

were suppressed by specific siRNAs in PC3 cells transiently

expressing p53 R175H. Suppression of these genes inhibited cell

growth; however, among the candidate genes, ID1 suppression

significantly accelerated the cell growth inhibition under

transient p53 R175H expression (Fig. 2A

and B). ID1 suppression and p53 R175H overexpression did

not influence the other protein expression level (Fig. 2C). These results suggest that p53

R175H expression and ID1 suppression cooperate to cause cell

growth inhibition.

Cell growth inhibition by ID1 and/or TP53

suppression in endogenously expressing p53 R175H, wt p53 cells and

in TP53-null cells

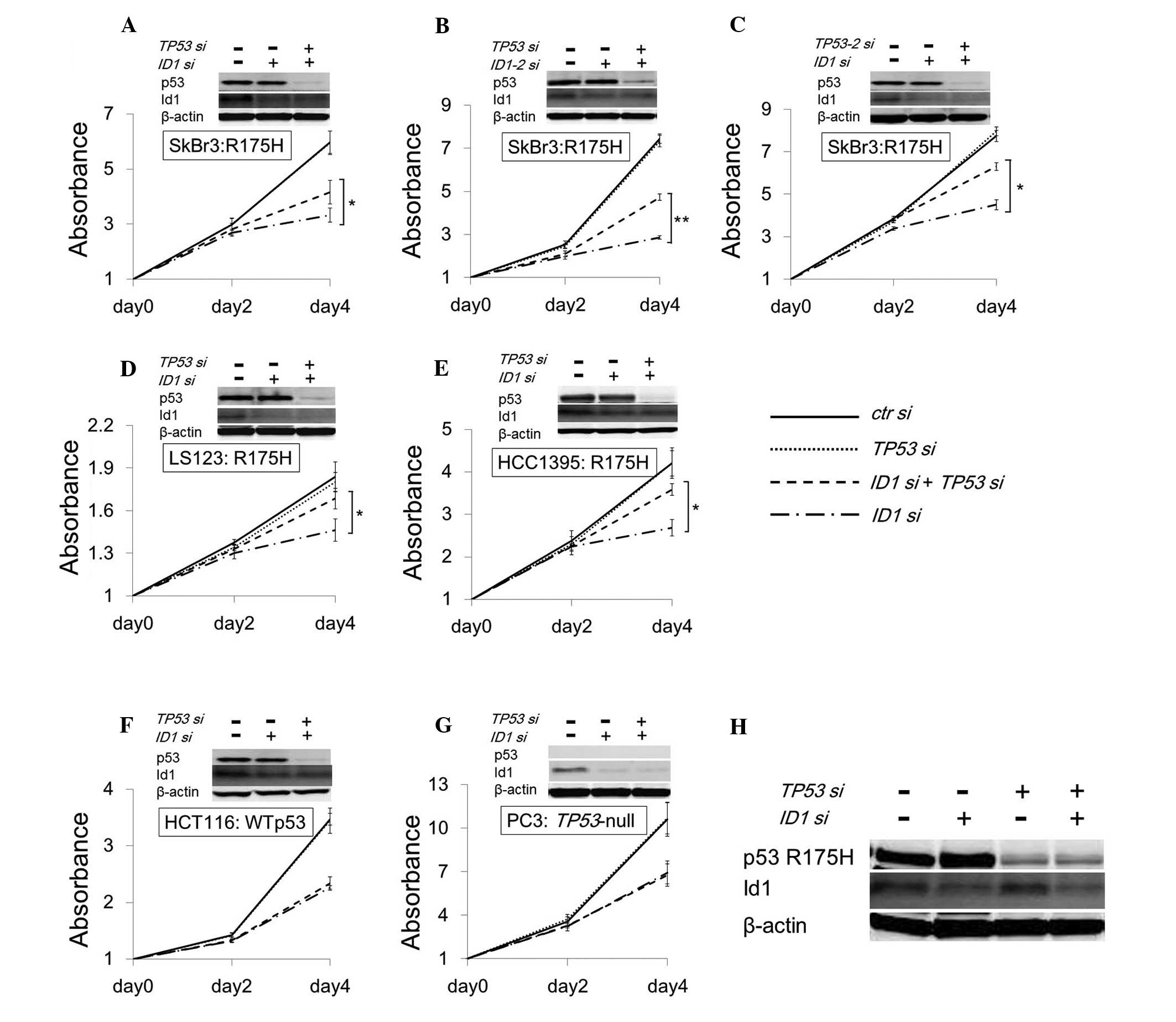

To determine whether cell growth inhibition is

rescued by the suppression of both candidate genes and p53 R175H,

siRNAs of the targeting candidate genes and TP53 were

transfected into SKBr3, a p53 R175H expressing cell line.

Downregulation of p53 R175H rescued cell growth inhibition caused

by ID1 suppression (Fig.

3A), but not by GYPC, NUP98, GP6 and EFNA4

suppression (data not shown). To exclude the off-target effect of

siRNA, other siRNA for ID1 and TP53 targeting

different sites (ID1-2 and TP53-2) were transfected

into SKBr3, and we observed reproducible results to the original

siRNAs (Fig. 3B and C). Moreover,

similar results were observed only in cell lines expressing p53

R175H (LS123, Fig. 3D and HCC1395,

Fig. 3E), but not in wt p53

(HCT116, Fig. 3F), and

TP53-null (PC3, Fig. 3G).

The quantity of the Id1 protein in SKBr3 was not altered by p53

R175H suppression (Fig. 3H), same

as p53 R175H transient expression. These results support the

finding that cell growth inhibition by ID1 suppression is

accelerated by p53 R175H.

Suppression of ID1 in cell lines

expressing another common mutant p53 (R273H)

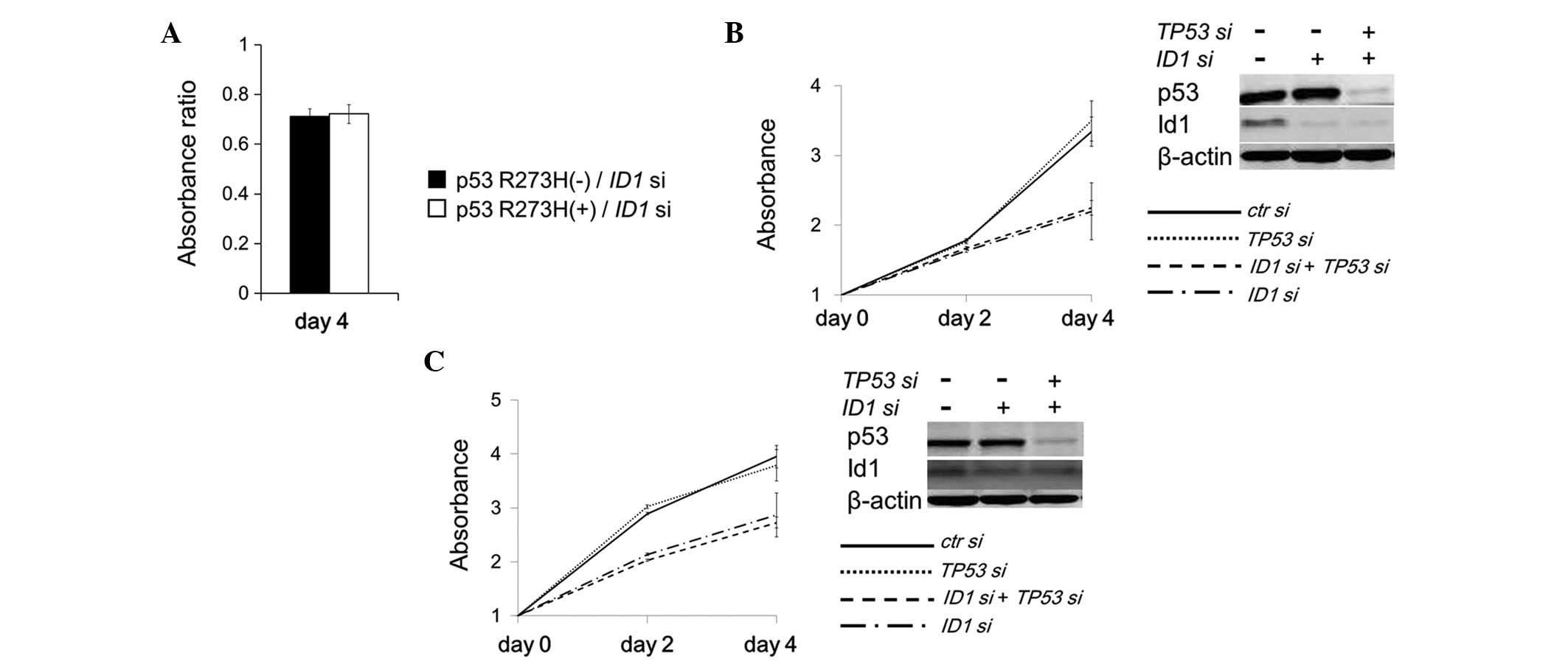

To examine whether cell growth inhibition caused by

ID1 suppression is accelerated specifically by p53 R175H

expression, another common p53 mutant (R273H) was expressed in a

PC3 cell line (TP53-null). Unlike p53 R175H expression, p53

R273H expression did not accelerate the cell growth inhibition

caused by ID1 suppression (Fig.

4A). Furthermore, the cell growth inhibition caused by

ID1 suppression was not restored by simultaneous suppression

of TP53 in HT-29 cells expressing endogenous p53 R273H

(Fig. 4B). Similar results were

observed in SW480 cells expressing endogenous p53 R273H/P309S

double mutants (Fig. 4C). These

results indicated that the growth inhibition induced by ID1

suppression may be accelerated by p53 R175H expression in a

specific manner.

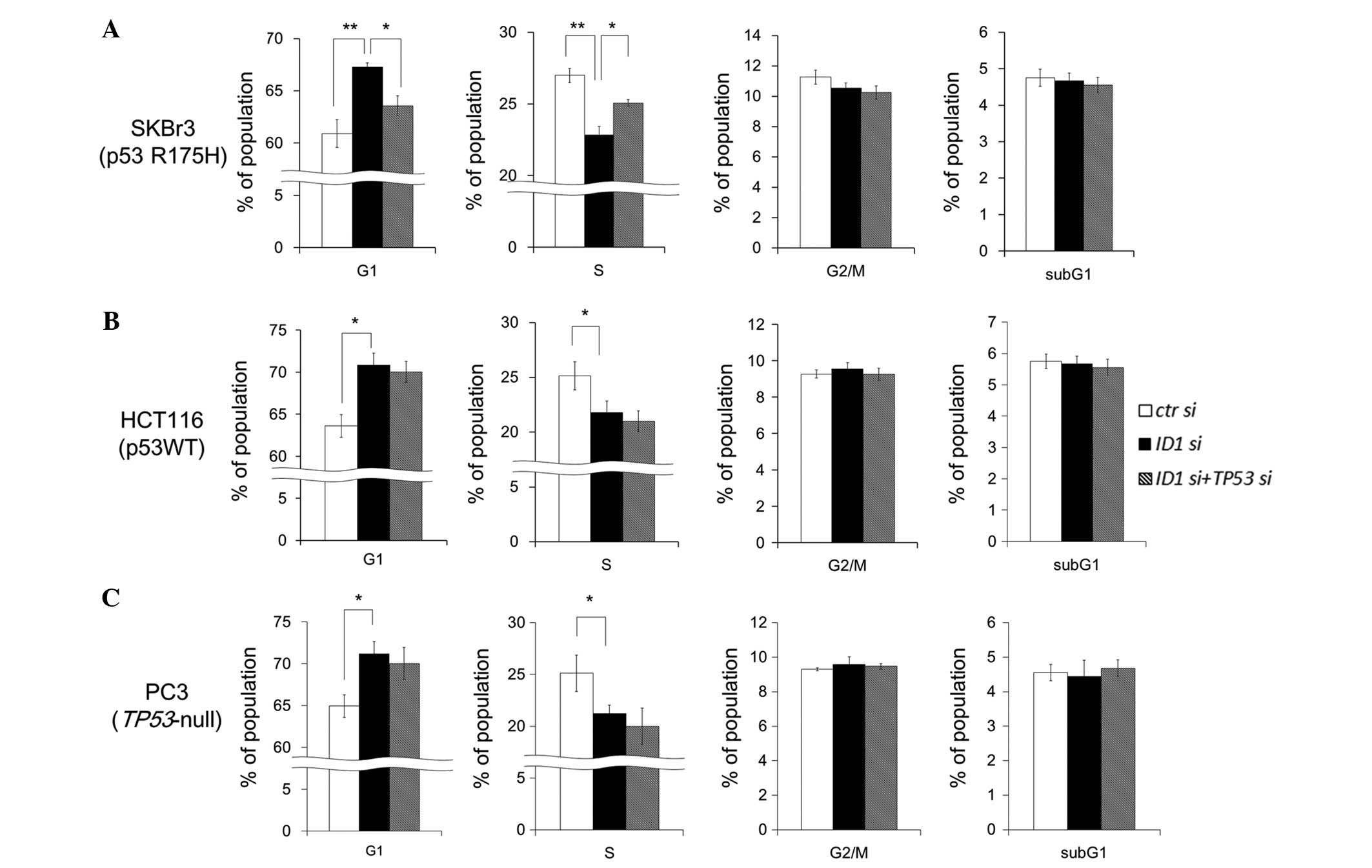

Cell cycle analysis under ID1 suppression

and ID1/TP53 double suppression

To examine whether ID1 and/or TP53

suppression change the proportion of cell cycle phases, FACS

analysis was performed in SKBr3 cells. ID1 suppression did

not change the sub-G1 fraction, but significantly decreased the S

phase fraction and increased the G1 phase fraction (Fig. 5A). ID1/TP53 double

suppression significantly restored the proportion of S phase and G1

phase fractions. These results suggest that p53 R175H potentiates

G1 arrest by ID1 suppression. In HCT116 (wild-type p53) and

PC3 (TP53-null) cells, ID1 suppression increased the

G1 phase fraction and decreased the S phase fraction. However,

unlike in SKBr3 cells, ID1/TP53 double suppression

did not restore the proportion of S phase and G1 phase fractions

(Fig. 5B and C). These results

suggest that ID1 suppression induces G1 arrest and the

arrest is specifically accelerated by p53 R175H expression.

Discussion

We identified ID1 as a synthetic sick/lethal

gene that caused cell growth inhibition in the presence of p53

R175H. Id1 is a member of the helix-loop-helix protein family

expressed in actively proliferating cells and regulates gene

transcription by hetero-dimerization with the basic

helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor (25). The homodimer of the bHLH

transcription factor activates the differentiation, whereas the

heterodimer, composed of Id1 and the bHLH transcription factor,

attenuates their ability to bind DNA and consequently inhibits cell

differentiation (26). Supporting

this finding, stable Id1 expression was found to block B cell

maturation (27). Moreover, Id1 can

inhibit differentiation of muscle and myeloid cells by associating

in vivo with E2A proteins (28,29).

It has also been reported that Id1 was immunohistochemically

expressed in majority of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) samples

(30). Furthermore, Id1 protein

expression in prostate cancer cells mediated resistance to

apoptosis induced by TNFα (31).

These lines of evidence also indicate that ID1 may play an

essential role in carcinogenesis.

In the present study, we demonstrated that

ID1 suppression resulted in cell growth inhibition that was

independent of TP53 status. However, cell growth inhibition

caused by ID1 suppression was accelerated specifically by

the p53 R175H mutant protein. If the accelerated cell growth

inhibition is attributable only to loss-of-function in p53 R175H,

this phenomenon should also be observed in TP53-null cells

and other cells expressing loss-of-function mutations other than

p53 R175H. Some p53 mutant proteins acquire additional functions

called gain-of-function (32). For

example, ectopic expression of p53 R175H resulted in

transactivation of genes that are not usually activated by

wild-type p53 (33–35). On the basis of these observations,

we concluded that the acceleration of cell growth inhibition was

likely attributable to gain-of-function of p53 R175H.

To date, synthetic sickness/lethality has been

classified into 2 types based on the initial genetic event. The

first type is attributable to a loss-of-function mutation in a

target gene and the second type is attributable to a

gain-of-function or an activated mutation in a target gene. For

example, the synthetic lethal interaction between loss-of-function

mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and PARP

inhibition (8) are a former type,

and gain-of-function mutations in the KRAS gene and STK33

inhibition (6) are a latter type.

Based on our results, it is clear that the synthetic sick/lethal

interaction between p53 R175H expression and ID1 suppression

is of the latter type. However, there is a clear difference between

the activated KRAS-STK33 interaction and the p53 R175H-Id1

interaction. Gain-of-function in activated K-ras depends on STK33

and is therefore blocked by STK33 suppression. By contrast, the

accelerated cell growth inhibition observed here cannot be

explained only by blockade of gain-of-function in p53 R175H by

ID1 suppression. By contrast, it is necessary for

accelerated growth inhibition by ID1 suppression. Taken

together, these results suggest that the synthetic

sickness/lethality of p53 R175H with ID1 suppression may be

through a gain-of-function mechanism that is distinct from the

previously identified gain-of-function mechanisms. Since both

expression and suppression of p53 R175H had no effect on the amount

of Id1 protein, p53 R175H may cooperate with downstream factor(s)

that are altered by ID1 suppression and may promote

synthetic sickness/lethality in cooperation with protein(s)

downstream of ID1.

The precise molecular mechanisms of the synthetic

sickness/lethality of ID1 suppression and p53 R175H

expression remain to be elucidated. In conclusion, Id1 and its

associated signaling pathway is one of the molecular targets of

cancer cells expressing the common p53 mutant R175H.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Atsuko Sato, Eri Yokota and Satoko

Aoki for their technical assistance. This study was supported in

part by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture,

Sports, Science and Technology (12217010 to S.K., 17015002 to C.I.,

and 20390163 to C.I.) and the Gonryo Medical Foundation to C.I. and

Sapporo Bioscience Foundation to S.K.

References

|

1

|

Molenaar JJ, Ebus ME, Geerts D, et al:

Inactivation of CDK2 is synthetically lethal to MYCN

over-expressing cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

106:12968–12973. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Canaani D: Methodological approaches in

application of synthetic lethality screening towards anticancer

therapy. Br J Cancer. 100:1213–1218. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Kaelin WG Jr: The concept of synthetic

lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer.

5:689–698. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bandyopadhyay N, Ranka S and Kahveci T:

Sslpred: predicting synthetic sickness lethality. Pac Symp

Biocomput. 7–18. 2012.

|

|

5

|

Luo J, Emanuele MJ, Li D, et al: A

genome-wide RNAi screen identifies multiple synthetic lethal

interactions with the Ras oncogene. Cell. 137:835–848. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Scholl C, Fröhling S, Dunn IF, et al:

Synthetic lethal interaction between oncogenic KRAS dependency and

STK33 suppression in human cancer cells. Cell. 137:821–834. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al:

Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a

therapeutic strategy. Nature. 434:917–921. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, et al:

Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the

efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with

BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin

Oncol. 30:372–379. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B and

Harris CC: p53 mutations in human cancers. Science. 253:49–53.

1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Levine AJ: p53, the cellular gatekeeper

for growth and division. Cell. 88:323–331. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Lill NL, Grossman SR, Ginsberg D, DeCaprio

J and Livingston DM: Binding and modulation of p53 by p300/CBP

coactivators. Nature. 387:823–827. 1997. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Sakaguchi K, Herrera JE, Saito S, et al:

DNA damage activates p53 through a phosphorylation-acetylation

cascade. Genes Dev. 12:2831–2841. 1998. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Soussi T, Dehouche K and Béroud C: p53

website and analysis of p53 gene mutations in human cancer: forging

a link between epidemiology and carcinogenesis. Hum Mutat.

15:105–113. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Olivier M, Eeles R, Hollstein M, Khan MA,

Harris CC and Hainaut P: The IARC TP53 database: new online

mutation analysis and recommendations to users. Hum Mutat.

19:607–614. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Soussi T, Ishioka C, Claustres M and

Béroud C: Locus-specific mutation databases: pitfalls and good

practice based on the p53 experience. Nat Rev Cancer. 6:83–90.

2006. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kato S, Han SY, Liu W, et al:

Understanding the function-structure and function-mutation

relationships of p53 tumor suppressor protein by high-resolution

missense mutation analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 100:8424–8429.

2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Olive KP, Tuveson DA, Ruhe ZC, et al:

Mutant p53 gain of function in two mouse models of Li-Fraumeni

syndrome. Cell. 119:847–860. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Lang GA, Iwakuma T, Suh YA, et al: Gain of

function of a p53 hot spot mutation in a mouse model of Li-Fraumeni

syndrome. Cell. 119:861–872. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Song H, Hollstein M and Xu Y: p53

gain-of-function cancer mutants induce genetic instability by

inactivating ATM. Nat Cell Biol. 9:573–580. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Liu G, McDonnell TJ, Montes de Oca Luna R,

et al: High metastatic potential in mice inheriting a targeted p53

missense mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 97:4174–4179. 2000.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Watanabe G, Kato S, Nakata H, Ishida T,

Ohuchi N and Ishioka C: αB-crystallin: a novel p53-target gene

required for p53-dependent apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 100:2368–2375.

2009.

|

|

22

|

Shiraishi K, Kato S, Han SY, et al:

Isolation of temperature-sensitive p53 mutations from a

comprehensive missense mutation library. J Biol Chem. 279:348–355.

2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Dong Z, Wei F, Zhou C, et al: Silencing

Id-1 inhibits lymphangiogenesis through down-regulation of VEGF-C

in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 47:27–32. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Kakudo Y, Shibata H, Otsuka K, Kato S and

Ishioka C: Lack of correlation between p53-dependent

transcriptional activity and the ability to induce apoptosis among

179 mutant p53s. Cancer Res. 65:2108–2114. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ling MT, Wang X, Zhang X and Wong YC: The

multiple roles of Id-1 in cancer progression. Differentiation.

74:481–487. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Benezra R, Davis RL, Lockshon D, Turner DL

and Weintraub H: The protein Id: a negative regulator of

helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 61:49–59. 1990.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Sun XH: Constitutive expression of the Id1

gene impairs mouse B cell development. Cell. 79:893–900. 1994.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jen Y, Weintraub H and Benezra R:

Overexpression of Id protein inhibits the muscle differentiation

program: in vivo association of Id with E2A proteins. Genes Dev.

6:1466–1479. 1992. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kreider BL, Benezra R, Rovera G and

Kadesch T: Inhibition of myeloid differentiation by the

helix-loop-helix protein Id. Science. 255:1700–1702. 1992.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Rothschild SI, Kappeler A, Rastchiller D,

et al: The stem cell gene ‘inhibitor of differentiation 1’ (ID1) is

frequently expressed in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer.

71:306–311. 2011.

|

|

31

|

Ling MT, Wang X, Ouyang XS, Xu K, Tsao SW

and Wong YC: Id-1 expression promotes cell survival through

activation of NF-κB signalling pathway in prostate cancer cells.

Oncogene. 22:4498–4508. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Brosh R and Rotter V: When mutants gain

new powers: news from the mutant p53 field. Nat Rev Cancer.

9:701–713. 2009.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Roger L, Jullien L, Gire V and Roux P:

Gain of oncogenic function of p53 mutants regulates E-cadherin

expression uncoupled from cell invasion in colon cancer cells. J

Cell Sci. 123:1295–1305. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Yan W and Chen X: Identification of GRO1

as a critical determinant for mutant p53 gain of function. J Biol

Chem. 284:12178–12187. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liu DP, Song H and Xu Y: A common gain of

function of p53 cancer mutants in inducing genetic instability.

Oncogene. 29:949–956. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|