Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is one of the most commonly

diagnosed malignancies and the third most common lethal cancer in

men (1). Over 160,000 new cases of

prostate cancer were estimated to have been diagnosed in 2017 in

the US, which accounts for 19% of all cancer cases (2). Consequently, it is vitally important

and necessary to study the associated detailed mechanisms of this

disease.

TROAP, also named tastin and first cloned in 1995,

is a cytoplasmic protein that is necessary for the function of

trophinin as a cell adhesion molecule (3,4). The

associated adhesion molecule complex consists of bystin, trophinin

and TROAP, and bystin has been shown to be present in human PCa

(5). In addition to its function as

a component of the adhesion complex during embryo implantation,

TROAP has also been reported to be required for spindle assembly

during mitosis (6,7). It is also essential for centrosome

integrity and proper bipolar organisation of spindle assembly

during mitosis, playing an essential role in cell proliferation.

Levels of this protein peak during the G2/M phase and abruptly

decline after division. However, its biological function in

prostate cancer and cancer in general is still unclear. We found

that TROAP expression correlates with patient survival and

deduced that TROAP plays an important role in prostate cancer

progression.

In this study, we first examined the TROAP

expression profile using several online datasets of prostate

cancer; in addition, patient survival analysis with respect to the

target gene was performed using PROGgeneV2 Database. Next, the

regulatory effect of TROAP on cellular survival and apoptosis was

demonstrated by performing cell proliferation and flow cytometric

assays. Western blot analysis was used to determine the expression

of apoptosis and cell cycle-related biomarkers. Correlations

between WNT3 or survivin expression and TROAP transcripts in

prostate cancer tissues were also analysed. Finally, the regulation

of TROAP in PCa cell progression was established in vivo.

Collectively, our data suggest that TROAP could be an important

target for PCa diagnosis and treatment.

Materials and methods

Database analysis

To examine TROAP mRNA expression using microarray

data, the Oncomine database tool (www.oncomine.org) was used. Briefly, the TROAP

gene was queried in the database and the results were filtered by

selecting prostate cancer studies that reported TROAP

expression data (Reporter ID: 204649_at for Varambally Prostate,

Arredouani Prostate, Wallace Prostate and A_23_P150935 for Grasso

Prostate). Both probes were targeted to nucleotide sequence of

TROAP. P-values for each group were calculated using The Student's

t-test. Standardised normalisation techniques and statistical

calculations are provided by the Oncomine website. Additionally,

ProggeneV2 prognostic Database (http://watson.compbio.iupui.edu/chirayu) was used to

collect information about patient survival data with regards to

TROAP expression in prostate cancer (8).

Cell lines and culture conditions

Human prostate cell lines, LNCaP, WPMY-1, DU145,

22Rv1, PC-3 and C4-2 (all have been confirmed that they are not

misidentified or contaminated by checking established cell lines

with the list of known misidentified cell lines available from the

International Cell Line Authentication Committee http://iclac.org/databases/cross-contaminations) were

purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Science

(Shanghai, China). LNCaP and WPMY-1 cells were cultured in DMEM

(Hyclone Laboratories; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA;

SH30022.01B) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). C4-2 and 22RV1

cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Hyclone Laboratories; GE

Healthcare Life Sciences, SH30809.01B) containing 10% FBS (Biowest,

Riverside, MO, USA; S1810). DU145 and PC-3 cells were cultured in

Ham's/F-12 (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA,

USA; 11765054) with 10% FBS and 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA,

Hyclone Laboratories; GE Healthcare Life Sciences; SH30238.01). The

culture medium was supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin and 100

mg/ml streptomycin to avoid bacterial contamination. All cells were

cultured in humidified air at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Total RNA isolation and quantitative

real-time (qRT)-PCR analysis

Total RNA was prepared from several human prostate

cancer cell lines (WPMY-1, LNCap, 22Rv1, DU145, PC3 and C4-2) using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

following the manufacturer's protocol. Then, 1 µg of total RNA was

reverse transcribed in a final volume of 20 µl using random primers

and M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA; M170A)

and standard conditions. The reverse transcription reaction was

performed using the following conditions: 37°C for 30 min; 85°C for

5 sec and a hold at 4°C.

After reverse transcription, the qRT-PCR was

performed using the SYBR Green Master Mix Kit (Takara

Biotechnology, Co., Ltd., Dalian, China) and a BioRad CFX96

sequence detection system, according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The relative levels of TROAP were determined by

qRT-PCR using gene specific primers, and expression was normalised

to the internal control β-actin. The primer sequences used are as

follows: forward, 5′-GTGGACATCCGCAAAGAC-3′ and reverse,

5′-AAAGGGTGTAACGCAACTA-3′ for β-actin, and forward,

5′-GGTCAGGAGAAAAGCGGAGGAAG-3′ (sense) and reverse,

5′-AGGCGTGCGTTTCTGAGAGC-3′ for TROAP. The qRT-PCR was conducted

under the following conditions: 95°C for 60 sec, 40 cycles of 95°C

for 5 sec and 60°C for 20 sec. Each sample was run at least three

times. The relative expression level of TROAP was computed using

the comparative cycle threshold (CT) method 2−∆∆Cq

(9).

Lentivirus infection of prostate

cancer cells

The shRNA sequence targeting TROAP was synthesised

and ligated into pGreenPuro™ shRNA Cloning and Expression

Lentivector (#s SI505A-1; SBI System Biosciences, LLC, Palo Alto,

CA, USA), which contains green fluorescent protein (GFP) tag. The

shRNA sequence targeting human TROAP was:

5′-AGAACCAAGATCCAAGGAGATCTCGAGATCTCCTTGGATCTTGGTTCT-3′. The

non-targeting shCon sequence (control shRNA) used was

5′-TTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTCTCGAGACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAA-3′. Lentiviral

particles were then packaged in the 93T cells and harvested using

ultra-centrifugation. DU145 and 22Rv1 cell lines cultured in 6-well

plates were infected with lentivirus containing targeting shRNA or

control shRNA. Cells were harvested after 3 days for qRT-PCR and

other experiments.

Cell proliferation assays

The effect of TROAP knockdown on cell proliferation

was determined using the

3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

(MTT) method according to the manufacturer's (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) instructions. Briefly, DU145 and 22Rv1 cells infected with

shTROAP and shCon, separately, were seeded in 96-well plates

(3,000/well) and incubated for 5 days. At day 1 to day 5 after

seeding, MTT plus acidic isopropanol solution was added to every

well and samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. The absorbance

values were measured at 595 nm using a Biotek Epoch Microplate

Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

Each group comprised five replicates.

Colony formation assays

For colony formation assays, DU145 and 22Rv1 cells

were seeded in 6-well plates at 500 cells/well and cultured in

medium containing 10% FBS, changing the medium every 3 days. After

14 days, the colonies were washed with PBS, fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde, and stained with 0.1% freshly-prepared crystal

violet solution (Beyotime Unstitute of Biotechnology, Haimen,

China). Visible colonies containing 50 or more cells were observed

and manually counted using an inverted light microscope (Olympus

CKX41; Olympus Corp., Tokyo, Japan). Triplicate wells were measured

for each treatment group.

Flow cytometric analysis

For flow cytometric analysis, infected cells were

collected 6 days after inoculation by trypsinisation. Cells for

cell cycle analysis were stained using propidium iodide (PI) with

the Cycle TEST PLUS DNA Reagent kit (BD Biosciences, Franklin

Lakes, NJ, USA; NC9941088) according to the manufacturer's

protocol, and then subjected to FACScan. The percentage of the

cells in the G0/G1, S, and G2/M phases were computed and compared.

For apoptosis analysis, double staining was performed using the

FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection kit (Nanjing KeyGen Biotech,

Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), according to the manufacturer's

instructions, and then the stained cells were analysed using

FACScan (BD Biosciences). The percentage of early apoptotic and

apoptotic cells were compared to that in the control groups for

each experiment.

Western blot assay

Cells were lysed using RIPA buffer containing 100 mM

Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 10 mM EDTA, 4% SDS, and 10% glycine supplemented

with PMSF (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Total protein was quantified

using the Coomassie brilliant blue method at 560 nm. The

supernatant (10 µg of protein) was denatured and separated on 12%

SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and then

transferred to 0.22-μm polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes

(EMD Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and incubated with specific

antibodies as follows: anti-GAPDH (dilution 1:500,000; cat. no.

10494-1-AP), anti-TROAP (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 13634-1-AP),

anti-PSA (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 10679-1-AP), anti-cleaved

caspase 3 (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 25546-1-AP), anti-caspase 9

(dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 10380-1-AP), anti-cyclin A2 (dilution

1:1,000; cat. no. 18202-1-AP), anti-WNT3 (dilution 1:500; cat. no.

17983-1-AP), anti-survivin (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 10508-1-AP)

and anti-CNNB1 (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 51067-2-AP) from

Proteintech Group Inc., (Rosemont, IL, USA); anti-Bcl-2 (dilution

1:1,000; cat. no. 2876) and PARP (dilution 1:1,000; cat. no. 9542)

from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA);

anti-cyclin B1 (dilution 1:2,000; cat. no. 21540) from SAB

(Nanjing, China). Bands were visualised using enhanced

chemiluminescence (ECL-PLUS/Kit, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Tokyo,

Japan) reagents.

Pairwise correlation analysis

WNT3 and survivin were previously reported to be

relevant for carcinogenesis. To determine whether there is a

correlation between the expression of WNT3 or survivin and

TROAP transcripts in PCa, pairwise gene correlation analysis

was performed using the web server GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) (10). P<0.05 was defined as

statistically significant. Correlation analysis results were then

further validated by western blot analysis.

Xenograft tumourigenicity and gene

expression assay in vivo

The prior approval of the Ethics Committee of the

Third Affiliated Hospital, The Second Military Medical University

was obtained for use of the animals in this study.

Twelve male athymic nude mice (nu/nu), 4 weeks old

(weight, 15–20 g), were housed under pathogen-free conditions in a

barrier animal facility with a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle and

humidity (45–55%) at 21–24°C, and food and water were available

ad libitum. For in vivo tumourigenicity experiments,

DU145 cells stably infected with lentivirus or negative control

were collected, resuspended in PBS, and injected subcutaneously

into the right subaxillary of each male 4-week-old BALB/c nude

mouse (2×104 per mouse; SLRC Laboratory Animal,

Shanghai, China). The tumour volumes and weights were measured

every 3 days and maximum allowable tumour size was controlled

according to the IACUC guidelines (diameter, 2.0 cm; volume 4.2

cm3); tumour volume (V) was measured as V = length ×

width2 × 0.5. Forty-five days after injection, mice were

sacrificed by cervical dislocation and tumours were dissected,

imaged, and weighed; the tumours were also collected and fixed for

further western blot analysis. The relative amount of protein was

calculated based on the integrated optical density reference value

using ImageJ optical density gel analysis software (National

Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). GAPDH was used as the

control.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 5.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

Student's t-test was used for two-group comparisons and ANOVA with

Sidak's multiple comparisons were used to test the significance of

multigroup data. Data are presented as mean ± SD. A P-value

<0.05 was considered to be indicative of statistical

significance.

Results

TROAP is overexpressed in PCa and

higher expression is associated with shorter overall survival

To achieve a profound understanding of the role of

TROAP in PCa, a publicly available array data source, the Oncomine

database tool (www.oncomine.org), was first used to investigate the

expression levels of TROAP. The Oncomine Cancer Microarray

database contains several datasets comparing human prostate

carcinoma to normal tissue. TROAP expression was commonly highly

expressed in several PCa groups compared to that in adjacent normal

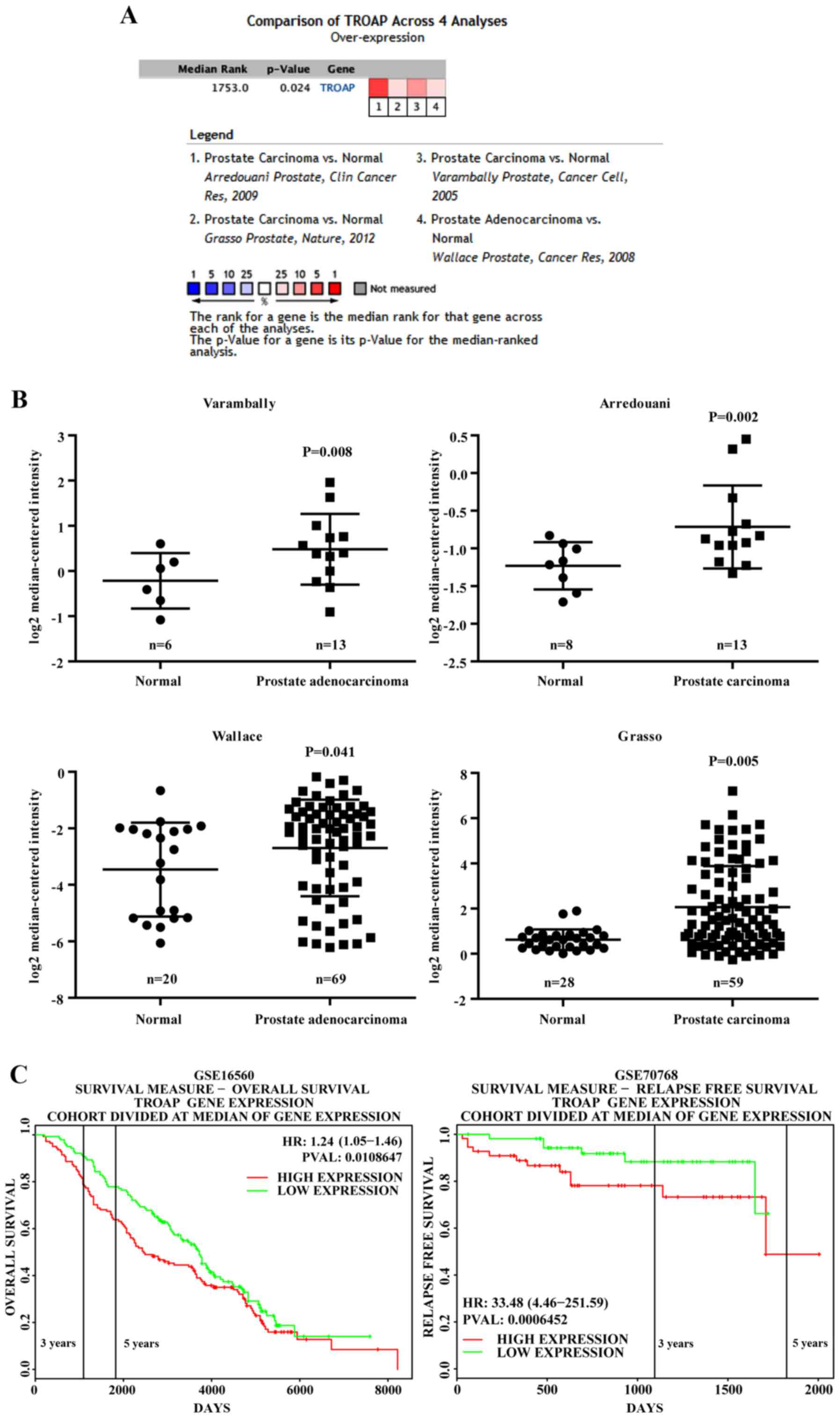

tissue. As shown in Fig. 1A and B,

four datasets [Arredouani et al (11), Grasso et al (12), Varambally et al (13) and Wallace et al (14)] showed that TROAP is significantly

overexpressed in PCa as compared to levels in adjacent normal

tissue, with fold changes ranging from 1.27 to 2.08 (11–14).

Additionally, by exploring the PROGgeneV2 Prognostic Database, we

found that PCa patients (GSE16560) (15) with TROAP levels that were higher

than the median expression level had significant shorter overall

survival than those with lower TROAP levels (Fig. 1C). Notably, another database

(GSE70768) (16) showed that higher

TROAP expression is associated with poor relapse-free survival

(Fig. 1C).

TROAP expression in prostate cells and

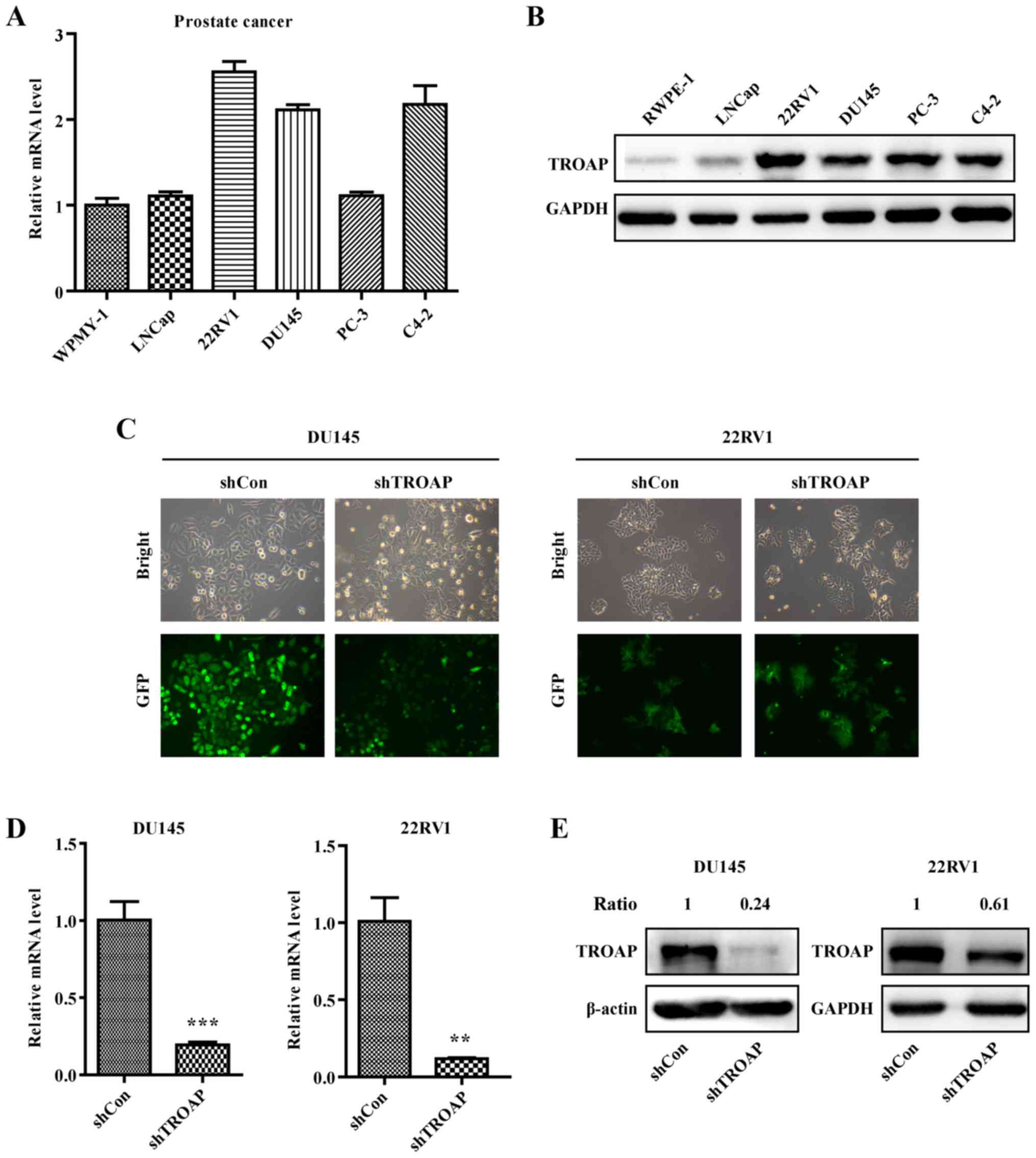

knockdown efficiency in PCa cell lines

The expression of TROAP in different PCa cell lines

including WPMY-1, LNCaP, 22Rv1, DU145, PC3 and C4-2 was detected by

qRT-PCR and western blotting. The results showed that the

expression of TROAP is relatively high in PCa cells, especially

non-metastatic 22Rv1 and metastatic DU145 cells (Fig. 2A and B), which are

androgen-independent PCa cell lines. Accordingly, these two cell

lines were selected for further study. DU145 and 22Rv1 cells were

separately infected with the shTROAP and shCon lentiviruses. Based

on the observed expression of GFP using a microscope, the infection

efficiencies were adequate (Fig.

2C). Results of qRT-PCR illustrated that the mRNA levels of

TROAP were significantly suppressed in DU145 and 22Rv1 cells

(Fig. 2D). Accordingly, the protein

levels of TROAP were decreased obviously with shRNA targeting in

DU145 and 22Rv1 cells (Fig.

2E).

Inhibition of PCa cell proliferation

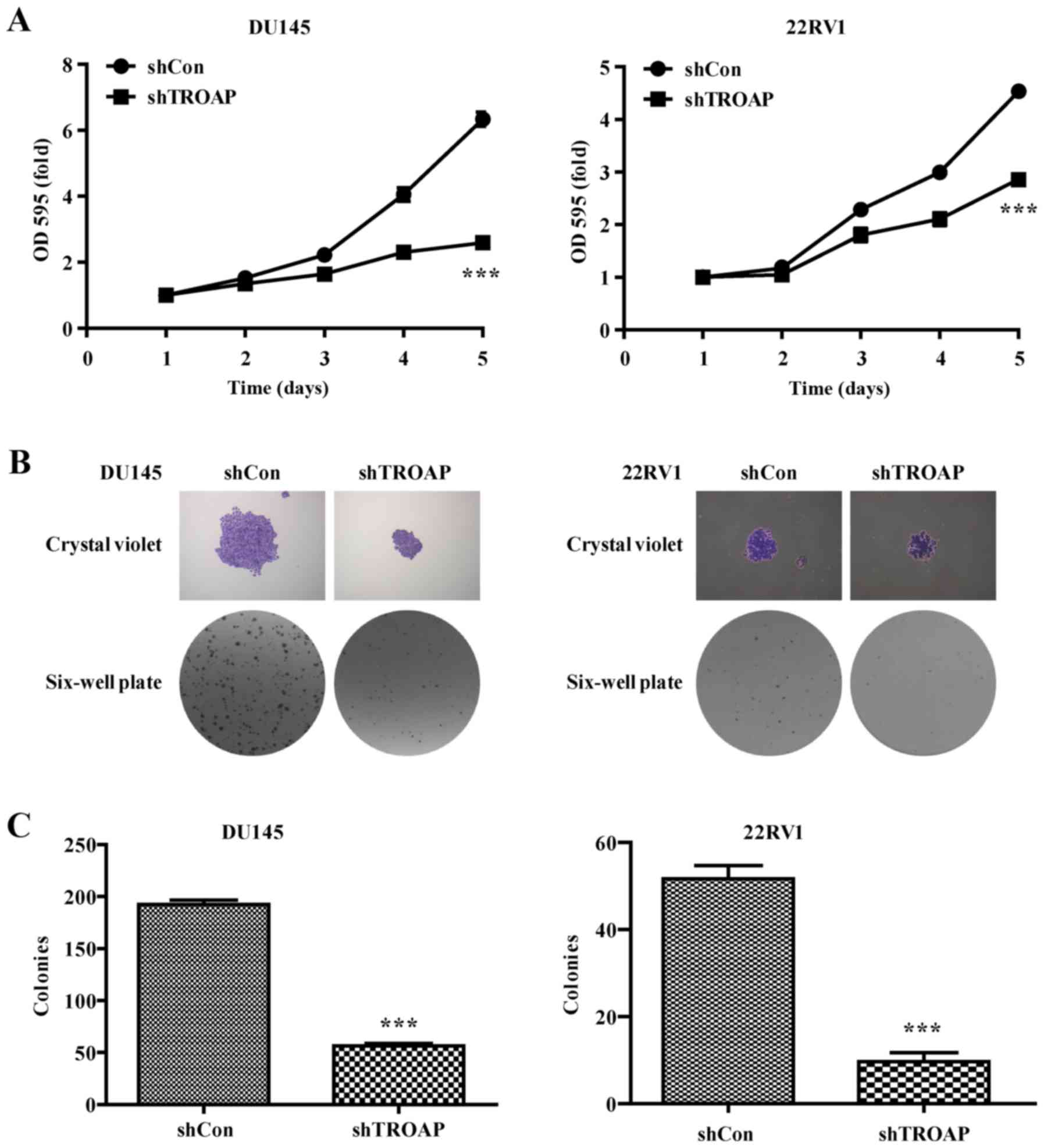

by shRNA-mediated TROAP knockdown

To determine the effect of different treatments on

PCa cell proliferation, prostate cancer cell numbers were assessed

using MTT and colony formation assays. As shown by the cell growth

curve, growth of the shTROAP-treated groups was significantly

slower than that of the shCon groups for DU145 and 22Rv1 cells

(Fig. 3A). Furthermore, the sizes

of independent colonies were much smaller in DU145 and 22RV1 cells

infected with shTROAP, compared to that in cells infected with

shCon (Fig. 3B). Moreover, the

numbers of colonies formed in shTROAP-infected groups were

significantly lower than that in shCon-infected groups (P<0.001,

Fig. 3C). The data demonstrated a

significant reduction in cell expansion with reduced TROAP

expression.

Knockdown of TROAP leads to cell cycle

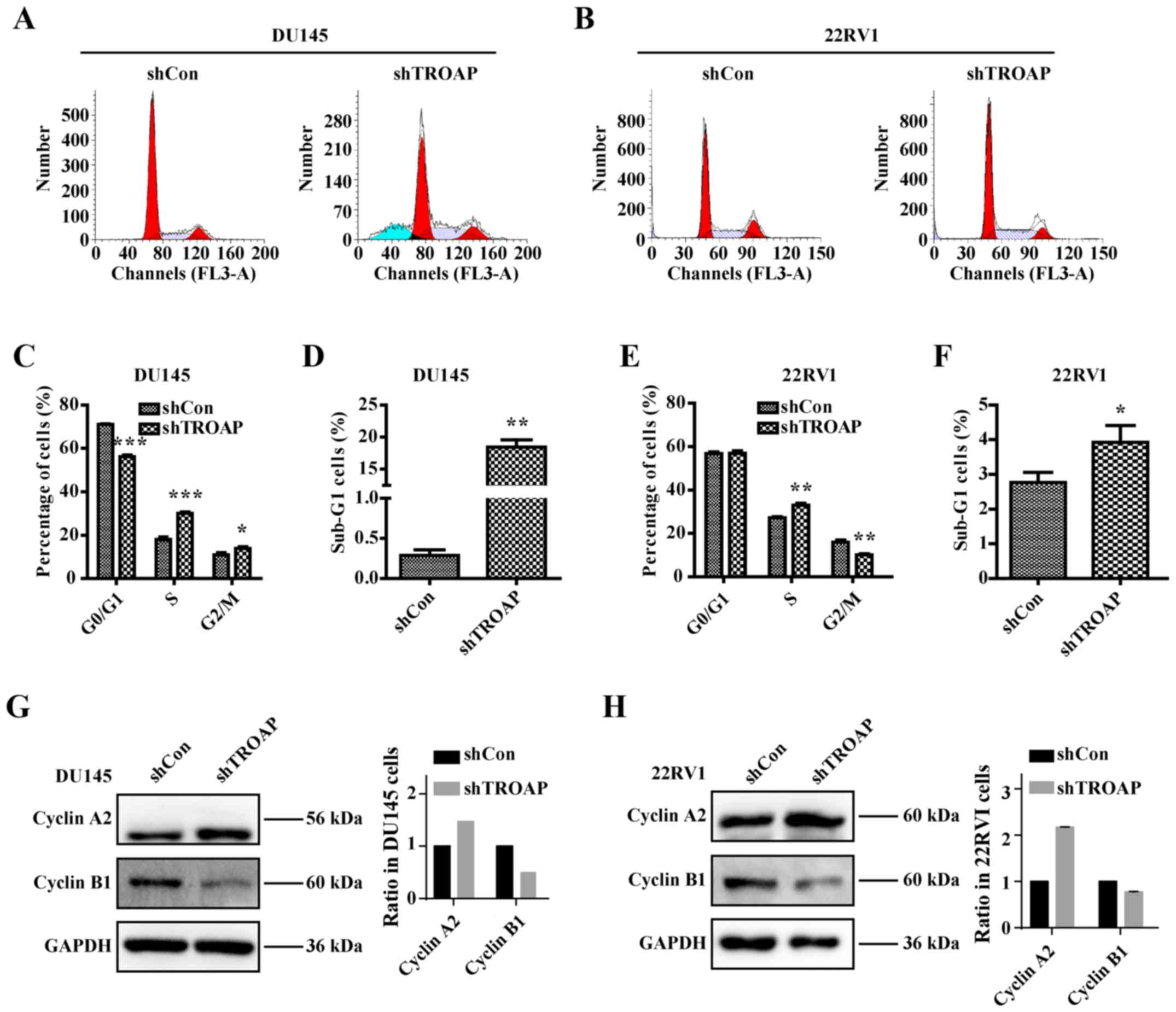

arrest and cell cycle modulation through cyclin A2/cyclinB1

Having established that TROAP expression is related

to PCa cell proliferation, we were next interested in whether the

cell cycle is influenced by TROAP. After performing cell cycle

analysis by flow cytometry, we found that inhibition of TROAP

significantly decreased the number of cells in the G0/G1 phase and

increased the number of cells in the S phase in the DU145 and 22Rv1

cells (Fig. 4A and B). The S phase

cell percentage was increased from 18% in the shCon group to 30% in

the shTROAP group in DU145 cells and from 27% in the shCon group to

33% in the shTROAP group in the 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 4C and E). TROAP knockdown further led

to significant increases in the sub-G1-phase cell population in

both DU145 and 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 4D and

F). We then focused on the molecular mechanisms through which

TROAP knockdown delays S phase to mitosis transition by analysing

the expression of checkpoint proteins. Western blotting showed that

downregulation of TROAP increased the expression of cyclin A2 but

decreased the expression of cyclin B1, compared to that in

respective controls, for the DU145 and 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 4G and H). The results thus

corresponded to a cell cycle arrest at S phase.

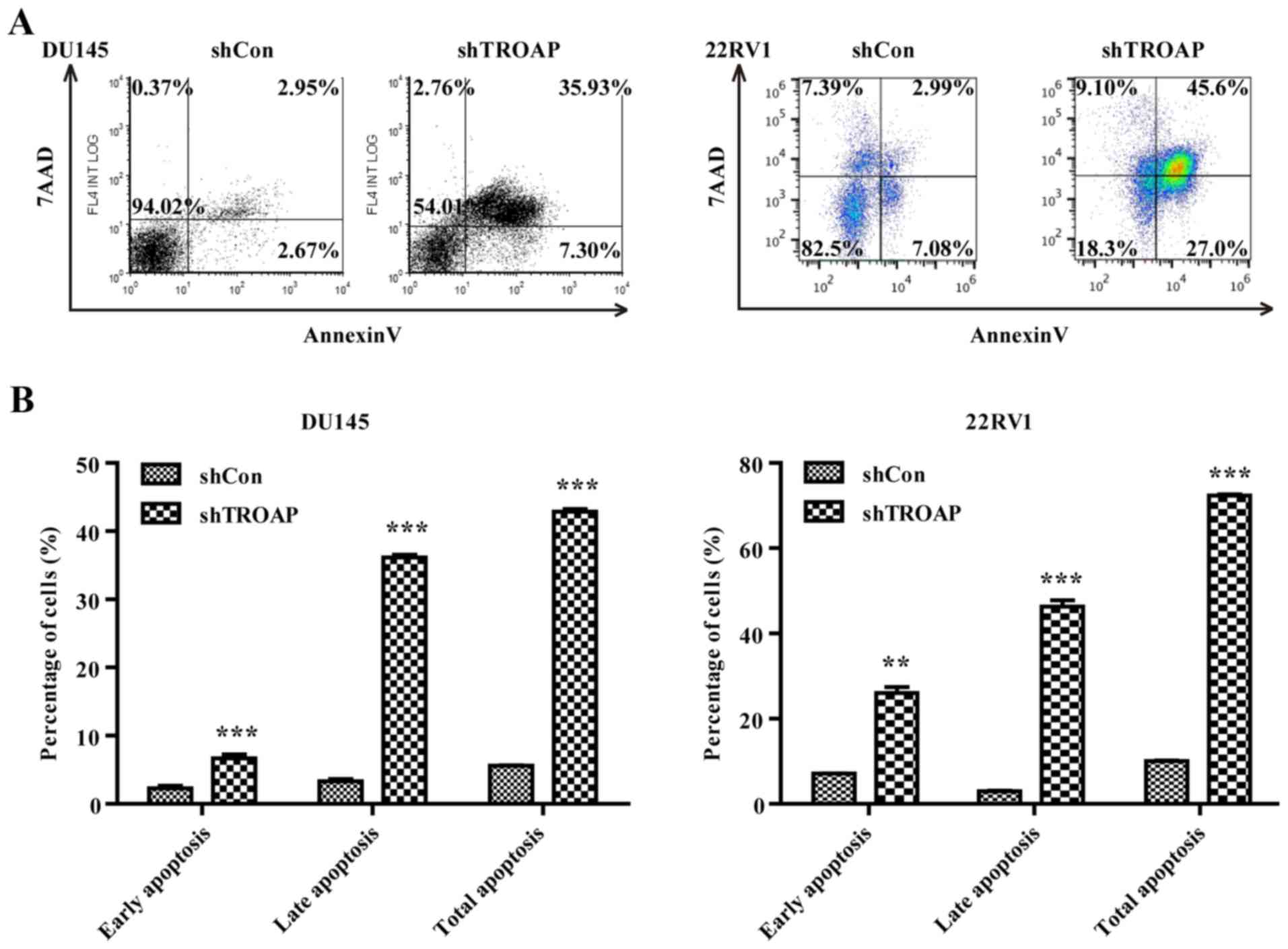

Knockdown of TROAP promotes apoptosis

in PCa cell lines through the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway

Based on the observed increases in the sub-G1-phase

cell population (Fig. 4D and F), we

attempted to determine whether the decrease in TROAP was associated

with cancer cell apoptosis by flow cytometry. TROAP silencing

significantly accelerated both DU145 and 22Rv1 cell apoptosis.

Lentivirus-mediated shRNA increased both early and late apoptosis

in the DU145 and 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 5A

and B). The total percentage of apoptotic cells increased from

6% in the shCon group to 43% in the shTROAP group for DU145 cells,

and from 10% in the shCon group to 72% in the shTROAP group for

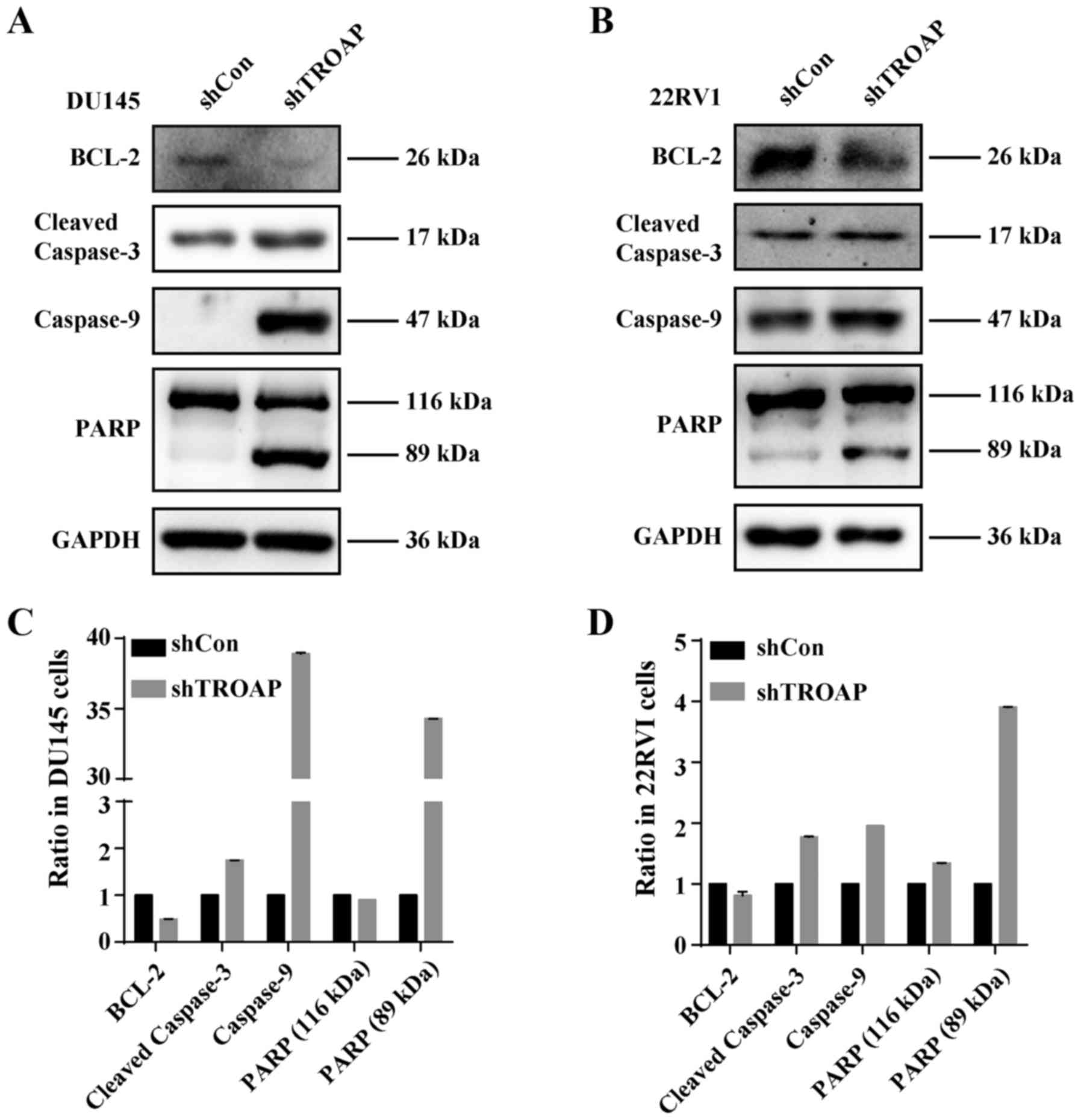

22Rv1 cells. To investigate the underlying mechanisms of TROAP

knockdown-induced apoptosis in these cells, the protein levels of

Bcl-2, caspase-9, cleaved-caspase-3 and PARP in PCa cells were

measured by western blot analysis after treatment with shTROAP.

Western blot analysis showed that depletion of TROAP decreased the

levels of Bcl-2, whereas levels of caspase-9, caspase-3 and PARP

increased (Fig. 6). The results

demonstrated that the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway was activated

by downregulation of TROAP in PCa cells.

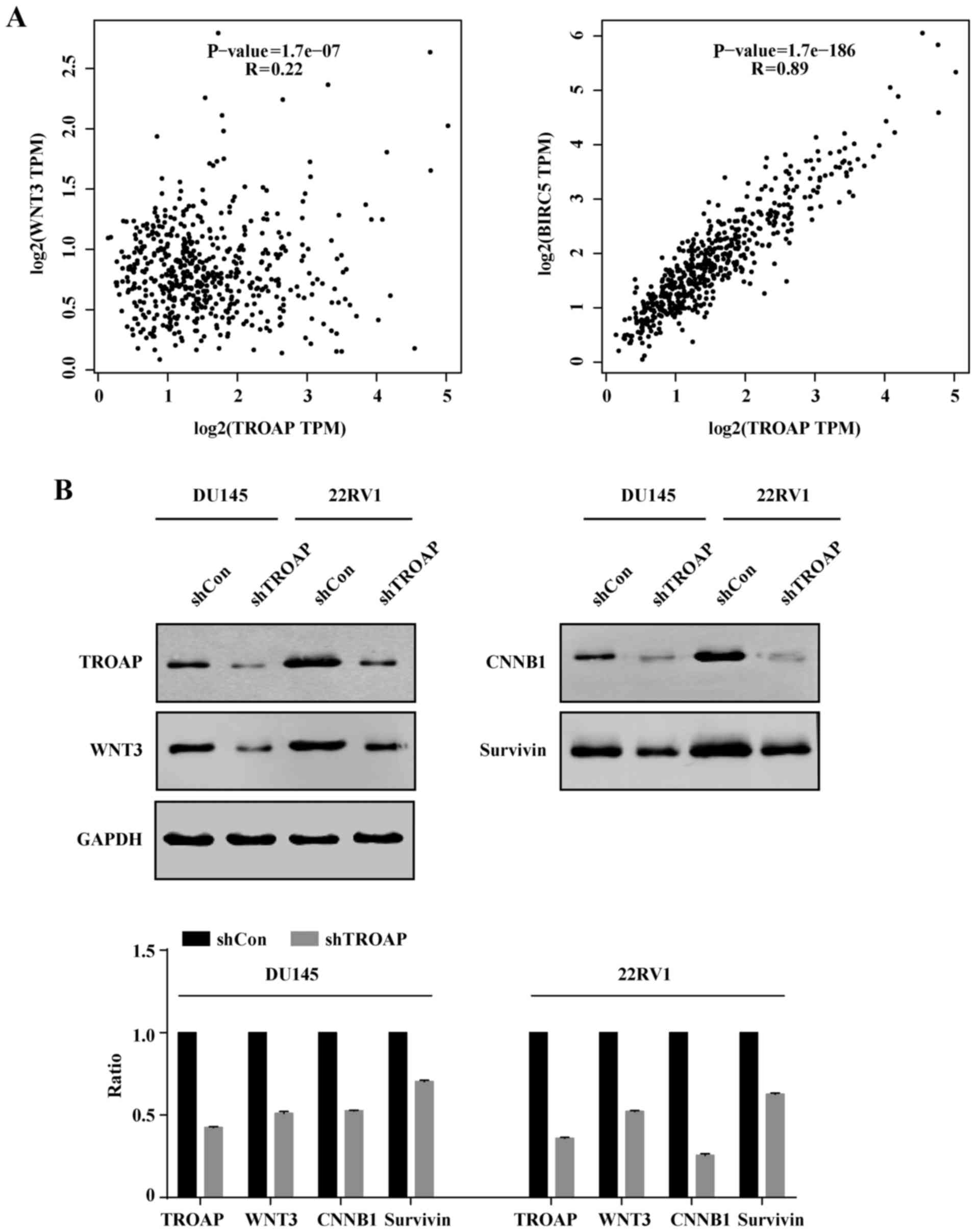

TROAP expression correlates with WNT3

and survivin levels in PCa

Survivin is demonstrated to protect cells from

caspase-induced apoptosis. Meanwhile, it was the downstream target

of wnt/β-catenin. Hence, we deduced that TROAP induced apoptosis by

interrupting the expression of surviving and wnt. Correlation

analysis indicated that WNT3 and survivin (BIRC5) levels were

positively correlated with TROAP expression (P<0.05; Fig. 7A). To further validate this

analysis, we performed western blotting. Consistently, it was

verified that protein levels of WNT3 and survivin decreased with

TROAP knockdown (Fig. 7B).

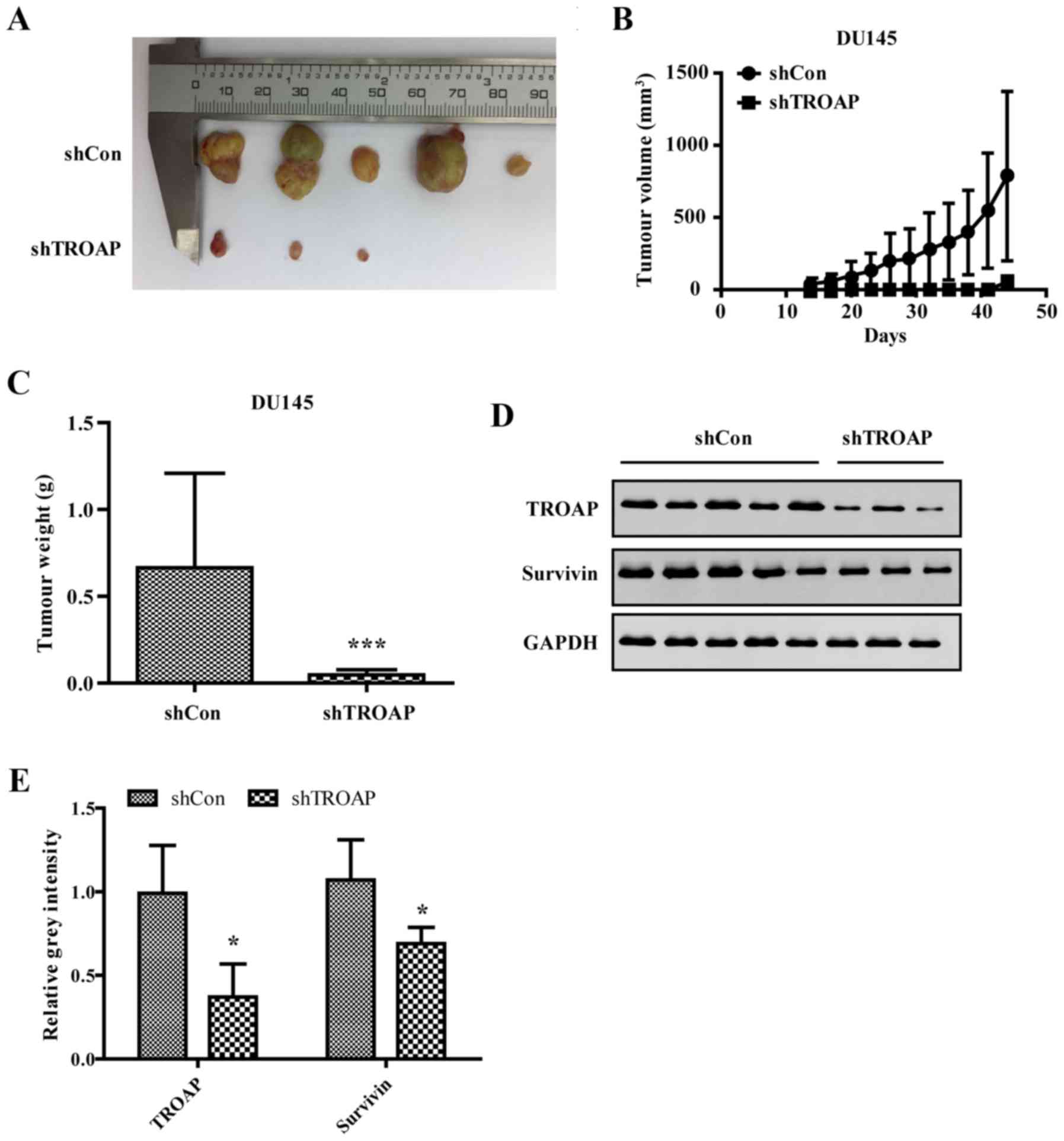

Knockdown of TROAP inhibits PCa growth

in nude mice

To investigate the effect of TROAP on PCa cell

proliferation in vivo, a xenograft model was utilised to

assess the tumorigenesis of DU145 cells after shTROAP or shCon

transduction. As shown, the largest diameter of the tumours was

approximately 10 mm in the shCon group. Tumours in mice injected

with shTROAP-transduced cells were significantly smaller than those

originating from shCon-infected cells (Fig. 8A). Both the volume and the weight of

tumours derived from shTROAP DU145 cells were significantly

decreased compared to those of the shCon group (Fig. 8B and C). Thus, the results confirmed

that TROAP knockdown can inhibit PCa tumour growth in

vivo.

To further illustrate that tumour suppression by

shTROAP is associated with the knockdown of TROAP and associated

downregulation of survivin in PCa cells, mice from the two groups

were sacrificed after the last measurement. Protein expression

levels of both TROAP and survivin were detected by western

blotting. As shown in Fig. 8D and

E, the levels of both were efficiently decreased in tumour

tissue of the shTROAP group compared to those in the shcontrol

group.

Discussion

In the present study, we initially demonstrated that

TROAP is upregulated in PCa tissues. Importantly, clinical data

have suggested that TROAP is associated with poor overall and

relapse-free survival in prostate cancer patients, underscoring the

oncogenic role of this marker, particularly in relapse. We also

demonstrated for the first time that TROAP protein expression is

relatively high in several PCa cell lines by using qRT-PCR and

western blot analysis.

Silencing of TROAP significantly inhibited the

growth and colony formation ability of PCa cells through cell cycle

arrest at the S phase and the induction of apoptosis. More

importantly, downregulation of TROAP dramatically decreased cyclin

B1 and Bcl-2 levels and increased cyclin A2, caspase-9 protein

levels and cleaved PARP.

Knockdown of TROAP caused cell cycle arrest and

apoptosis through the cyclin/Cdk pathway. Cyclin A2 is a core cell

cycle regulator that activates Cdk1 and Cdk2 (17). The expression of cyclin A2 and CDK2,

are known to promote S phase entry in mammals (18). Cyclin B1 is a key regulator of cell

cycle progression from the S phase to the G2/M phase and its

downregulation therefore results in S phase arrest (19). Therefore, upregulation of cyclin A2

and downregulation of cyclin B1, induced by TROAP silencing,

explains why PCa cells were arrested at the S phase. Furthermore,

it was found that in the shTROAP group, the G2/M phase cell ratio

was increased in DU145 cells and decreased G2/M in 22RV1 cells.

This may be owing to the different metastatic abilities in DU145

and 22RV1 cells as metastasis may relate to the cell cycle

(20,21). This needs further study. In

addition, more cell cycle markers are required to determine the

exact point at which the cell cycle is disrupted.

To further confirm that apoptosis induced by TROAP

depletion is associated with the mitochondrial pathway, the levels

of Bcl-2, cleaved caspase-3, caspase-9, and PARP were detected by

western blotting. The results demonstrated that the mitochondrial

pathway was activated by downregulation of TROAP in PCa cells.

Survivin is the smallest member of the human IAPs (inhibitor of

apoptosis proteins) and is the downstream target gene of the Wnt

signalling pathway. WNT3, a member of the Wnt family, was reported

to be associated with hepatic, lung, and colorectal carcinogenesis

(22–25). It can protect cells from

caspase-induced apoptosis, activated in mitosis, presumably by

binding caspase-3, −7, and −9 (26). The results of the correlation

analysis indicated that TROAP expression was correlated with WNT3

and survivin in PCa. Knockdown of TROAP could decrease the Wnt 3

and survivin expression, which confirms both the in vitro

and in vivo experiments. Hence, we deduced that TROAP may

affect proliferation through the WNT signalling pathway.

In conclusion, knockdown of TROAP decreased cell

proliferation and colony formation and induced cell cycle arrest

and apoptosis in vitro. Taken together, we concluded that

TROAP functions as a regulator of PCa to control tumour growth.

In conclusion, collectively, our observations

indicate that TROAP is one of the driving mechanisms of

Wnt/β-catenin signalling. Our findings provide new insights into

the mechanism of the progression of PCa.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants from the

Youth Program of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family

Planning (no. 20164Y0040); the National Natural Science Foundation

of China (no. 81772747); the National Natural Science Foundation of

China for Youths (no. 81702515, 81702501) and the Shanghai Sailing

Program (no. 17YF1425400).

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/or analysed during the present

study can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable

request.

Authors' contributions

JY, CC, MC and ZS performed the vector construction

experiments and drafted the manuscript. SG and FQ participated in

the RT-PCR and western blot experiments. XP, QY and YT participated

in the cellular function experiments. LW and WY participated in the

animal experiments and were responsible for the data analysis and

for the figure formation. XC participated in the research design,

reviewed the literature and performed data examination. All authors

read and approved the manuscript and agree to be accountable for

all aspects of the research in ensuring that the accuracy or

integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated

and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Animal experiments in this study were approved by

the Ethics Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital, The Second

Military Medical University.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors state that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD and Jemal A: Cancer

statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 66:7–30. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Hoffman RM, Meisner AL, Arap W, Barry M,

Shah SK, Zeliadt SB and Wiggins CL: Trends in United States

prostate cancer incidence rates by age and stage, 1995–2012. Cancer

Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 25:259–263. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Fukuda MN, Sato T, Nakayama J, Klier G,

Mikami M, Aoki D and Nozawa S: Trophinin and tastin, a novel cell

adhesion molecule complex with potential involvement in embryo

implantation. Genes Dev. 9:1199–1210. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Nadano D, Nakayama J, Matsuzawa S, Sato

TA, Matsuda T and Fukuda MN: Human tastin, a proline-rich

cytoplasmic protein, associates with the microtubular cytoskeleton.

Biochem J. 364:669–677. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Ayala GE, Dai H, Li R, Ittmann M, Thompson

TC, Rowley D and Wheeler TM: Bystin in perineural invasion of

prostate cancer. Prostate. 66:266–272. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Yang S, Liu X, Yin Y, Fukuda MN and Zhou

J: Tastin is required for bipolar spindle assembly and centrosome

integrity during mitosis. FASEB J. 22:1960–1972. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li CW and Chen BS: Investigating core

genetic-and-epigenetic cell cycle networks for stemness and

carcinogenic mechanisms, and cancer drug design using big database

mining and genome-wide next-generation sequencing data. Cell Cycle.

15:2593–2607. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Goswami CP and Nakshatri H: PROGgeneV2:

Enhancements on the existing database. BMC Cancer. 14:9702014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C and

Zhang Z: GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression

profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45:W98–W102.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Arredouani MS, Lu B, Bhasin M, Eljanne M,

Yue W, Mosquera JM, Bubley GJ, Li V, Rubin MA, Libermann TA, et al:

Identification of the transcription factor single-minded homologue

2 as a potential biomarker and immunotherapy target in prostate

cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 15:5794–5802. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Grasso CS, Wu YM, Robinson DR, Cao X,

Dhanasekaran SM, Khan AP, Quist MJ, Jing X, Lonigro RJ, Brenner JC,

et al: The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant

prostate cancer. Nature. 487:239–243. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Varambally S, Yu J, Laxman B, Rhodes DR,

Mehra R, Tomlins SA, Shah RB, Chandran U, Monzon FA, Becich MJ, et

al: Integrative genomic and proteomic analysis of prostate cancer

reveals signatures of metastatic progression. Cancer Cell.

8:393–406. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Wallace TA, Prueitt RL, Yi M, Howe TM,

Gillespie JW, Yfantis HG, Stephens RM, Caporaso NE, Loffredo CA and

Ambs S: Tumor immunobiological differences in prostate cancer

between African-American and European-American men. Cancer Res.

68:927–936. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Sboner A, Demichelis F, Calza S, Pawitan

Y, Setlur SR, Hoshida Y, Perner S, Adami HO, Fall K, Mucci LA, et

al: Molecular sampling of prostate cancer: A dilemma for predicting

disease progression. BMC Med Genomics. 3:82010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ross-Adams H, Lamb AD, Dunning MJ, Halim

S, Lindberg J, Massie CM, Egevad LA, Russell R, Ramos-Montoya A,

Vowler SL, et al: CamCaP Study Group: Integration of copy number

and transcriptomics provides risk stratification in prostate

cancer: A discovery and validation cohort study. EBioMedicine.

2:1133–1144. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Hochegger H, Takeda S and Hunt T:

Cyclin-dependent kinases and cell-cycle transitions: Does one fit

all? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 9:910–916. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Ding H, Han C, Guo D, Wang D, Chen CS and

D'Ambrosio SM: OSU03012 activates Erk1/2 and Cdks leading to the

accumulation of cells in the S-phase and apoptosis. Int J Cancer.

123:2923–2930. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Xu X, Zhang H, Zhang Q, Huang Y, Dong J,

Liang Y, Liu HJ and Tong D: Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus N

protein prolongs S-phase cell cycle, induces endoplasmic reticulum

stress, and up-regulates interleukin-8 expression. Vet Microbiol.

164:212–221. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Basak S, Jacobs SB, Krieg AJ, Pathak N,

Zeng Q, Kaldis P, Giaccia AJ and Attardi LD: The

metastasis-associated gene Prl-3 is a p53 target involved in

cell-cycle regulation. Mol Cell. 30:303–314. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Song H, Hur I, Park HJ, Nam J, Park GB,

Kong KH, Hwang YM, Kim YS, Cho DH, Lee WJ, et al: Selenium Inhibits

Metastasis of Murine Melanoma Cells through the Induction of Cell

Cycle Arrest and Cell Death. Immune Netw. 9:236–242. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Nambotin SB, Tomimaru Y, Merle P, Wands JR

and Kim M: Functional consequences of WNT3/Frizzled7-mediated

signaling in non-transformed hepatic cells. Oncogenesis. 1:e312012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Kato S, Hayakawa Y, Sakurai H, Saiki I and

Yokoyama S: Mesenchymal-transitioned cancer cells instigate the

invasion of epithelial cancer cells through secretion of WNT3 and

WNT5B. Cancer Sci. 105:281–289. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Voloshanenko O, Erdmann G, Dubash TD,

Augustin I, Metzig M, Moffa G, Hundsrucker C, Kerr G, Sandmann T,

Anchang B, et al: Wnt secretion is required to maintain high levels

of Wnt activity in colon cancer cells. Nat Commun. 4:26102013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Wang HS, Nie X, Wu RB, Yuan HW, Ma YH, Liu

XL, Zhang JY, Deng XL, Na Q, Jin HY, et al: Downregulation of human

Wnt3 in gastric cancer suppresses cell proliferation and induces

apoptosis. OncoTargets Ther. 9:3849–3860. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li Z, Pei XH, Yan J, Yan F, Cappell KM,

Whitehurst AW and Xiong Y: CUL9 mediates the functions of the 3M

complex and ubiquitylates survivin to maintain genome integrity.

Mol Cell. 54:805–819. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|