Introduction

The incidence of tumors is rising due to population

growth, aging and advancements in tumor diagnostics (1), making malignant tumors a significant

threat to human health and life (2,3).

Cancer treatment options include surgery, radiotherapy,

chemotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy and immunotherapy

(1), with chemotherapy being the

most widely used across various cancer types. However,

chemoresistance remains a complex clinical challenge, leading to

the majority of cancer-related deaths (4,5).

Understanding the mechanisms of chemoresistance is therefore

essential for enhancing therapeutic efficacy, and the present

article reviewed the latest developments in tumor chemoresistance.

Notably, since numerous studies have already detailed the drug

resistance mechanisms of molecular targeted therapies, the present

review did not delve into those aspects (6–8).

Anatomical barriers that limit or obstruct the entry

of foreign substances into target tissues or cells play a

significant role in tumor chemoresistance. For example, in mammals,

the blood-brain barrier, composed of tightly connected endothelial

cells, basement membranes and astrocytes, restricts the passage of

most chemotherapeutic drugs, thereby reducing their efficacy

against central nervous system cancers. Mechanosensitive

Sox2+ tumor cells, for instance, develop chemoresistance

by constructing a blood-tumor barrier around capillaries (9). Similarly, the blood-testis barrier,

formed by testicular supporting cells, protects germ cells from

toxic substances. Sertoli cells, which are resistant to apoptosis

despite strong inflammatory stimuli (for example, LPS and IL-18),

play a pivotal role in maintaining the homeostasis of the

testicular environment, and this anti-apoptotic and

anti-inflammatory capability further enhances their resistance to

chemotherapy (10).

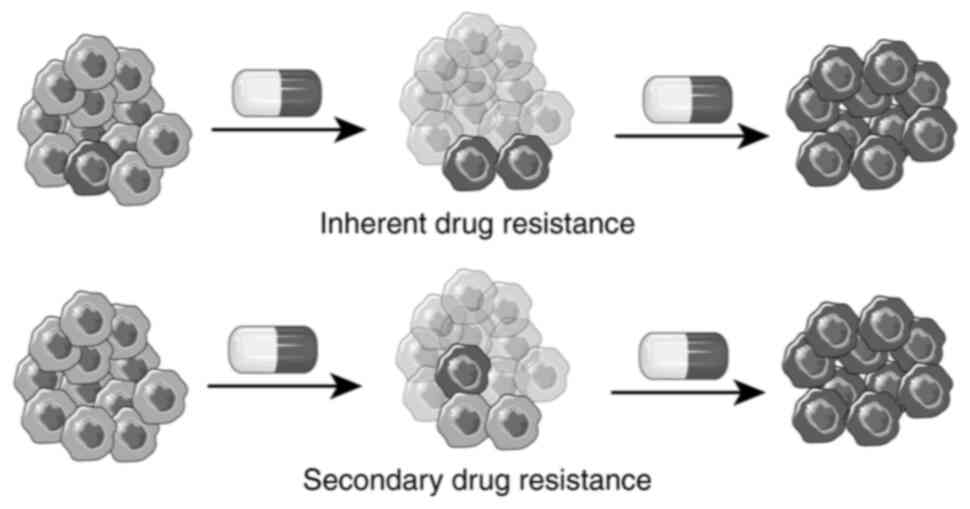

Chemotherapy resistance in cancer can be categorized

into inherent and secondary resistance based on its origin.

Inherent resistance refers to the presence of drug-resistant cells

within the tumor tissue before treatment begins (11). This concept suggests that drug

resistance is a ‘fait accompli’, with relapse occurring once

preexisting resistant cells repopulate (12). By contrast, secondary drug

resistance arises when tumor cells develop resistance to

chemotherapeutic drugs due to intracellular changes induced by the

drugs themselves (Fig. 1).

Chemotherapy resistance can also be classified into

primary drug resistance and multidrug resistance, depending on the

response of tumor cells to chemotherapy agents (13). Primary drug resistance occurs when

tumor cells develop resistance to a therapeutic drug after

treatment, commonly due to decreased drug uptake or increased drug

efflux. Multidrug resistance, on the other hand, involves tumor

cells becoming resistant not only to the therapeutic agent but also

to other chemotherapeutic drugs to which they have not been

previously exposed. This phenomenon is driven by mechanisms such as

enhanced drug efflux, increased DNA repair, neutralization of

chemotherapeutic agents, closure of nuclear pores and tumor cell

dormancy.

Mechanisms of action of chemotherapy

drugs

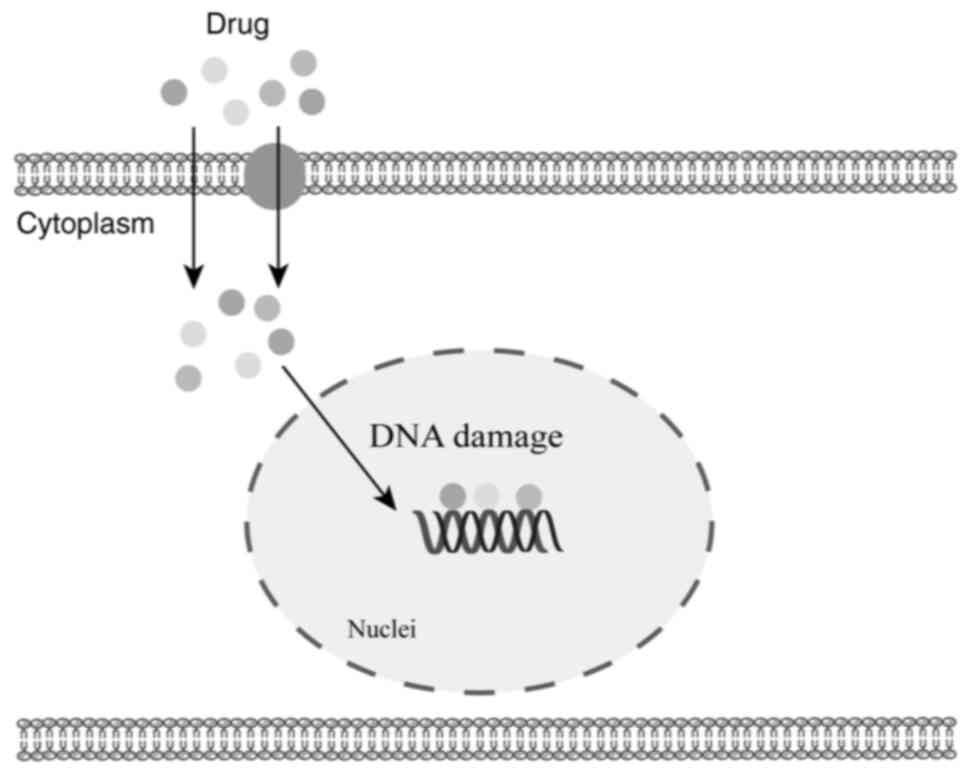

Chemotherapeutic agents encompass a wide range of

categories, including alkylating agents, antimetabolites,

antibiotics and antitumor phytopharmaceuticals, among others.

Although these agents employ diverse mechanisms of action, the

majority must penetrate the cell nucleus to exert their therapeutic

effects (Fig. 2).

Alkylating agents, such as cyclophosphamide and

cisplatin, are capable of targeting both proliferative and

non-proliferative cells. These agents possess active alkylating

groups that generate electrophilic groups with positive carbon

ions. These ions form covalent bonds with various nucleophilic

groups within cells, leading to cross-linking between DNA molecules

or between DNA and proteins, ultimately causing disruptions in DNA

replication and transcription, culminating in cell death (14,15).

Furthermore, alkylating agents have been shown to induce protein

oxidation and acetylation, which can impair the lipid homeostasis

of the nuclear membrane and destabilize the cellular genome

(15). Cisplatin, a cis-alkylating

agent, specifically induces cross-links within DNA double strands,

resulting in the cessation of DNA replication and transcription, or

even causing DNA strand breaks and apoptosis (16). As the first metal-based

chemotherapeutic drug, cisplatin has been extensively used, though

its side effects, including ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity, have

posed significant challenges in its clinical application (17,18).

Antimetabolites, structurally similar to natural

metabolites but lacking their corresponding biological functions,

competitively inhibit and disrupt nucleic acid and protein

synthesis, ultimately leading to cell death (19). The most notable example is

5-fluorouracil, which inhibits thymidine synthetase, thereby

impairing DNA synthesis within the body (20).

Antitumor antibiotics, derived from microorganisms,

exert their effects by directly damaging DNA or intercalating

within it, thereby disrupting transcription (21). A key example is doxorubicin, which

is extensively employed in the treatment of hematological

malignancies, breast cancer and lung cancer (22).

Plant-derived antitumor agents, such as paclitaxel

and vincristine, inhibit tumor cell proliferation by targeting

microtubule proteins. Paclitaxel primarily prevents the

depolymerization of microtubules during mitosis, whereas

vincristine inhibits microtubule polymerization (23). Despite the clinical success of these

plant-derived anticancer drugs, tumor resistance to them remains

prevalent, particularly in some gastrointestinal cancers that

exhibit resistance from the onset of chemotherapy.

Molecular mechanisms of chemotherapy

resistance

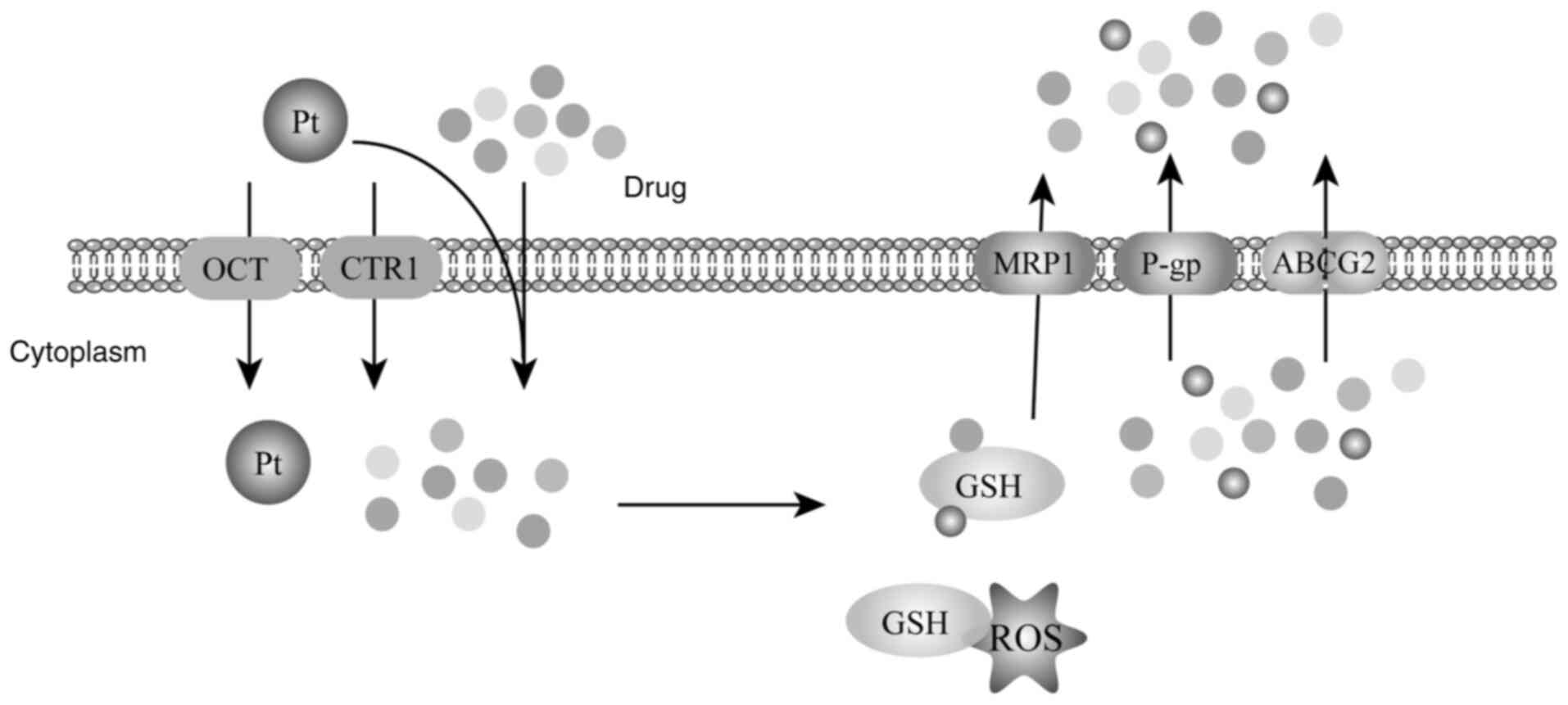

Decreased drug entry into cells

Plant-derived chemotherapeutic agents, such as

paclitaxel and vincristine, possess favorable lipid solubility,

enabling them to permeate cells via passive diffusion through the

lipid bilayer of the cell membrane (24,25).

By contrast, cisplatin, a metal-based anticancer drug, increases

its water solubility by replacing chloride ions with

Pt(NH3)2(H2O)2.

However, this substitution process occurs slowly, necessitating

that cisplatin primarily enters cells through active transport

mechanisms (26).

Research has identified that defective expression of

copper ion transporter protein 1 (CTR1) correlates with reduced

platinum accumulation in tissues, leading to decreased therapeutic

efficacy of platinum-based drugs in various tumors (27). Under basal conditions, CTR1 is

predominantly localized in the perinuclear region of cultured

cells, but in the presence of copper complexes, CTR1 is highly

expressed on the cell membrane, facilitating cisplatin's active

transport. The uptake of cisplatin mediated by CTR1 depends on its

metal-bound extracellular region, which is connected to the

N-glycan chain at Asn15 and the O-glycan chain at Thr27 (28). Although cisplatin does not alter the

subcellular localization of CTR1, co-localization studies using

fluorescent cisplatin derivatives revealed their presence in

CTR1-associated vesicular structures, indicating that cisplatin is

endocytosed concurrently with CTR1 and transported into the cell

(29).

Organic cation transporters (OCTs) are essential for

the cellular uptake of endogenous cationic substrates, hydrophilic

exogenous compounds, and platinum-based anticancer drugs. OCTs are

highly expressed in the renal basement membranes of humans and

mice, playing a significant role in mediating cisplatin uptake

(30). Elevated levels of OCT2 in

pre-chemotherapy biopsy samples have been associated with improved

prognosis when treated with cisplatin-inclusive regimens (31). Conversely, in OCT2 knockout (−/-)

mouse models, both nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity were

significantly reduced following cisplatin treatment (32). Although overexpressing transport

proteins exogenously is not yet feasible in clinical practice,

current strategies focus on developing novel carriers, such as

nanomaterial conjugates, to enhance the intracellular delivery of

chemotherapeutic drugs. This approach aims to increase the

intracellular concentration of these drugs, thereby enhancing their

efficacy in tumor cell eradication.

Increased chemotherapy drug

excretion

Members of the ABC protein transporter family,

primarily located in cell membranes, are responsible for expelling

cytotoxic substances, including chemotherapeutic drugs, out of the

cell by utilizing ATP hydrolysis for energy (33). This process impedes the accumulation

of therapeutic drug concentrations in target cells or organs,

thereby contributing to chemoresistance (34). Moreover, ABC transporter proteins

have been implicated in promoting tumor cell migration and invasion

(35). The ABC transporter family

is categorized into seven subgroups (ABCA-ABCG) comprising 48

proteins, based on sequence homology (36). All subfamilies, except the ABCF

family, have been linked to tumor chemoresistance, with key members

including ABCB1, ABCC1 and ABCG2.

The ABCB1 protein, also known as P-glycoprotein

(P-gp), serves a physiological role in safeguarding sensitive

tissues and the fetus from endogenous and exogenous toxins. It

primarily facilitates the transport of lipid-soluble drugs, such as

paclitaxel, vincristine and adriamycin (34,36–38).

Although P-gp binding substrates like everolimus have shown

potential in reversing chemoresistance in vitro and in

animal models by interacting with extracellular binding epitopes,

clinical trials have not yielded significant results, leaving the

underlying mechanisms unclear. Developing inhibitors that induce

conformational changes in ATP transport proteins remains a

promising avenue for future research (34,39–41).

The ABCC1 protein, also known as multidrug

resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1), was the second drug

resistance transporter identified after P-gp. MRP1 transports a

wide array of pathophysiological substrates, including folic acid,

bilirubin, anthracyclines, glutathione (GSH) and glucuronide

conjugates, though it is less effective at transporting

paclitaxel-like drugs compared with other ABC transporters

(36,41–43).

Tumor cells overexpressing MRP1 exhibit lower intracellular GSH

levels and higher GSH efflux, leading to its designation as a GSH

transporter protein. After GSH binds to chemotherapeutic drugs to

form a complex, MRP1-mediated co-extrusion reduces the

intracellular concentration of these drugs, contributing to tumor

cell drug resistance (41,44).

ABCG2, also known as breast cancer resistance

protein, was first identified in breast cancer-resistant tumors and

functions as a hemi-transport protein, requiring homo- or

heterodimerization to act as an effective transporter (45). Cryo-electron microscopy has revealed

that ABCG2 can bind and transport chemotherapeutic agents such as

topotecan and mitoxantrone, as well as P-gp inhibitors such as

tariquidar (46).

Currently, the primary strategy for modulating the

ABC transporter protein family involves targeting overexpressed

proteins, but clinical benefits have been limited. Future research

may focus on developing drugs that induce conformational changes in

ABC transporter proteins, potentially offering a new direction for

overcoming chemoresistance.

GSH and drug binding

GSH, a tripeptide consisting of glutamate, cysteine

and glycine, is a critical component of the cellular antioxidant

system, essential for tumor cells in scavenging reactive oxygen

species (ROS) and neutralizing chemotherapeutic agents (47). Predominantly existing in its reduced

form within the cell, GSH reacts with oxidizing agents such as ROS,

converting to GSH disulfide (GSSG). Excess GSSG can be expelled

from the cell or reduced back to GSH via GSH reductase. The

intracellular GSH concentration typically ranges from 2–10 mM,

~1,000-fold higher than in the extracellular environment (2–10 µM)

(47).

GSH also plays a critical role in ROS scavenging as

part of the cellular antioxidant system. Elevated GSH levels in

tumor cells safeguard them from ROS-induced DNA damage and

apoptosis by neutralizing ROS during tumor growth. Research

indicates that reducing GSH levels in tumor cells can elevate ROS

levels, thereby enhancing the cytotoxic effects of therapeutic

agents on these cells (48,49) (Fig.

3).

Moreover, GSH is involved in the neutralization of

cytotoxic substances under physiological conditions, with numerous

chemotherapeutic drugs, such as cisplatin and adriamycin, acting as

binding substrates for GSH (50).

Catalyzed by GSH-S-transferase (GST), GSH directly binds to

electrophilic xenobiotics in the cytoplasm, preventing these

chemotherapeutic drugs from entering the nucleus and exerting their

inhibitory effects. The resulting GSH-drug conjugates are then

exported from the cell via MRP1, thereby reducing the intracellular

concentration of these drugs and contributing to the development of

chemoresistance in tumor cells (51). Experimental evidence suggests that

decreasing intracellular GSH levels can reverse cisplatin

resistance and enhance its therapeutic efficacy (52).

Intracellular GSH levels are modulated by various

factors. Transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) is a well-known

inhibitor of normal epithelial cell proliferation, and its

suppression can increase the susceptibility of epithelial tissues

to cancer. Interestingly, while high TGF-β signaling expression in

the skin prevents benign papillary tumors from progressing to

malignancy, it paradoxically facilitates the malignant

transformation of squamous cell carcinoma stem cells into squamous

carcinoma, thereby promoting metastasis (53). Upon activation, TGF-β ligands bind

to TbRII, which phosphorylates TbRI. The activated TbRI then

transmits signals by phosphorylating intracellular effectors SMAD2

and SMAD3 (SMAD2/3). These phosphorylated SMAD proteins form a

complex with SMAD4, which interacts with other transcriptional

regulators to activate downstream target genes. Notably, TGF-β

reporter gene-positive basal cells exhibit high expression of genes

involved in GSH metabolism and significantly lower ROS levels

(53). In RNA-seq analysis of

tyrosine kinase receptor inhibitor (TKI)-resistant non-small cell

lung cancer, aldo-keto reductase 1B1 (AKR1B1) was found to be

highly expressed in multiple drug-resistant cell lines, promoting

GSH biosynthesis through STAT3-mediated upregulation of

SLC7A11-dependent cystine uptake, leading to TKI resistance

(54).

Both GSH and GST levels are elevated in tumor cells

compared with normal cells, closely correlating with drug

resistance. GSH levels can be measured using gold nanoparticles

detected by a lateral flow plasma biosensor or even visually, with

quantification achieved through automated analysis software. This

method has shown a strong positive correlation between GSH levels

and temozolomide resistance in GBM cells (55).

Beyond the GSH antioxidant system, eukaryotes

possess another critical antioxidant mechanism-the thioredoxin

system-which manages intracellular oxidative stress and supports

cell proliferation when GSH is depleted (56). Cytosolic flavin adenine dinucleotide

oxidoreductase 1 (TXNRD1), a selenoprotein with extensive

antioxidant and redox regulatory functions, is overexpressed in

numerous cancers and plays a key role in their growth and survival.

Inhibiting TXNRD1, especially in the context of GSH depletion,

increases oxidative stress within tumor cells, leading to their

death (57). Given the protective

role of the GSH system in shielding tumor cells from

chemotherapeutic agents and ROS, exploring the regulatory

mechanisms of this system and developing strategies to deplete GSH

in tumor cells using molecularly targeted drugs or nanomaterials

holds significant therapeutic promise.

Closure of nuclear pores and

exocytosis of drugs in the nucleus

The nuclear pore complex is a basket-like structure

embedded within the inner and outer nuclear membranes, featuring

apertures of ~70-80 nm and a channel diameter of ~9 nm,

facilitating the exchange of substances between the nucleus and the

cytoplasm. Numerous chemotherapeutic agents, such as platinum and

fluoropyrimidines, which inhibit DNA replication, must traverse the

nuclear pore complex to reach their targets and exert their

cytotoxic effects (58). Vault

particles, barrel-shaped structures primarily composed of major

vault protein (MVP), vADP-ribose polymerase, and

telomerase-associated protein 1, are considered to interact with

the nuclear pore complex. MVP, which constitutes 70% of the vault's

mass, is considered to mediate the translocation of macromolecules,

potentially rerouting chemotherapeutic drugs away from their

subcellular targets and contributing to multidrug resistance in

tumor cells (59,60). However, this hypothesis requires

further validation.

Lung resistance-related protein (LRP), also known as

major vault protein, is a key component of vault particles and

nuclear pore complexes in humans (61). Studies have demonstrated that LRP is

highly expressed in numerous tumor cells that lack P-gp expression,

and its elevated levels are associated with reduced chemotherapy

sensitivity (62). In a lung

adenocarcinoma cell model, gefitinib-resistant cells exhibited

significant upregulation of YB-1, which promotes downstream AKT

signaling and activates epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT),

thereby increasing resistance to gefitinib through direct

activation of MVP (63). CD73, a

glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored plasma membrane protein,

physiologically hydrolyzes extracellular adenosine monophosphate

into adenosine and inorganic phosphate. Evidence suggests that CD73

interacts with MVP, activating the SRC-AKT pathway and affecting

gemcitabine chemosensitivity in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

(64).

While LRP is known to enhance tumor cell resistance

to chemotherapeutic agents, MVP deficiency has been associated with

a reduced likelihood of tumor progression. In HBV-encoded protein X

(HBx)-transgenic (TG) mice crossed with LRP-deficient mice,

significant reductions in tumor number, size, liver-to-body weight

ratio, alanine aminotransferase levels and alpha-fetoprotein levels

were observed compared with HBx-TG mice carrying the HBx,

indicating that LRP loss greatly diminishes tumor progression and

extends survival time (65).

Vault RNAs (vtRNAs), non-coding RNAs comprising ~5%

of vault particles, have been found to show high expression in cell

lines with elevated EBV protein levels, particularly those

expressing high levels of LMP1. Overexpression of vtRNAs has been

associated with increased EBV expression and the inhibition of

apoptosis through the overexpression of NOL3 and BCL-xl (59). Although most chemotherapeutic

agents, including platinum compounds, antibiotics and

phytochemicals, require nuclear entry to function effectively, the

mechanisms governing their translocation across the nuclear

membrane remain underexplored. Further investigation into the

nuclear transport mechanisms of chemotherapeutic drugs and other

macromolecules is essential for advancing the understanding of

tumor chemoresistance.

Increased DNA repair

The DNA damage response (DDR) pathway plays a

pivotal role in recognizing, signaling and repairing DNA damage

caused by endogenous or exogenous factors, including

chemotherapeutic agents. It also regulates cell cycle progression

through DNA repair mechanisms, mitigating damage and preventing

apoptosis in the case of unrepaired lesions. As such, the DDR

pathway is a critical target in cancer therapy (66–68).

Numerous chemotherapeutic drugs, such as platinum compounds,

alkylating agents and antibiotics, induce DNA double-strand breaks

by directly binding to DNA. These breaks are among the most lethal

forms of DNA damage; failure to repair them triggers cell death.

Enhanced DNA repair mechanisms are a key factor in the development

of multidrug resistance in tumor cells (58,69–71).

Two primary pathways are responsible for repairing

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs): non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ)

and homologous recombination (HR). HR typically requires sister

chromatids as templates, limiting its activity to the S and G2

phases of the cell cycle. The efficiency of DNA repair largely

depends on HR-promoting factors including BRCA1 and NHEJ-promoting

proteins such as TP53BP1 (72).

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are essential for repairing DSBs, playing a key

role in inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and contributing to

drug resistance (73–75). Cells with defective BRCA1 or BRCA2

genes exhibit reduced homologous recombination repair capacity,

making them more sensitive to DNA-damaging agents such as cisplatin

and poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (75).

DNA topoisomerase-2 (TOP2) is an enzyme essential

for DNA replication, transcription and recombination, with a known

role in promoting cancer across various tumors (76). In hepatocellular carcinoma cells,

continuous exposure to regorafenib leads to upregulation of TOP2A

expression, while silencing TOP2A increases the sensitivity of

these cells to regorafenib (77).

PARP, a poly ADP-ribose polymerase, is involved in

chromatin modification, DNA replication, transcription and DNA

repair, particularly through base excision repair of single-strand

DNA (ssDNA) damage. In the absence of functional PARP, ssDNA breaks

remain unrepaired, leading to DSBs during subsequent cell cycles as

DNA replication forks encounter ssDNA regions. Cells with intact

DSB repair pathways can repair such breaks and survive. PARP

inhibitors (PARPi) specifically target BRCA1/2-deficient tumors,

inducing apoptosis (73). BRCA1/2

mutant cells are particularly vulnerable to PARPi due to their

inability to repair DSBs effectively (73). Treatment with the PARP inhibitor

olaparib has been shown to restore sensitivity to conventional

chemotherapy in patients with prostate cancer resistant to standard

treatments and carrying defective DNA repair genes, such as BRCA1/2

(78).

The phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) gene is

critical in regulating DNA damage repair, chromosome stability and

cell cycle progression through phosphatase-independent mechanisms.

Phosphorylation at tyrosine 240 (pY240-PTEN) is frequently observed

in patients with tumors undergoing radiotherapy. This

phosphorylated form of PTEN is highly expressed, associates with

chromatin via interaction with Ki-67, facilitates RAD51

recruitment, and enhances DNA repair processes, contributing to

chemoresistance and poor prognosis (70).

Schlafen family member 11 (SLFN11) is another key

regulator of DNA damage repair and is linked to the cellular

response to DNA-damaging agents in vitro. Replication

protein A (RPA), a heterotrimeric complex, is the primary

eukaryotic single-stranded DNA-binding protein, crucial for various

DNA metabolic pathways, including DNA replication, recombination,

damage checkpoints and repair. SLFN11 is recruited to sites of DNA

damage in an RPA-dependent manner, destabilizing the RPA-ssDNA

complex. Elevated levels of SLFN11 result in defects in checkpoint

maintenance and homologous recombination repair, thereby

sensitizing cells to DNA-damaging agents (79). Enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2)

induces the H3K27me3 histone modification, leading to the silencing

of SLFN11 in vivo. The use of EZH2 inhibitors in combination

with standard cytotoxic therapies has been identified to prevent

secondary resistance and improve the efficacy of chemotherapy in

both chemo-sensitive and chemoresistant small-cell lung cancer

models (80).

Mutations in DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A),

particularly at arginine 882 (DNMT3Amut), are commonly associated

with poor response to erythromycin chemotherapy. DNMT3Amut cells

exhibit impaired nucleosome expulsion and chromatin remodeling in

response to anthracyclines, which in turn hinders the recruitment

of the histone chaperone SPT-16. This defect impairs the cell's

ability to detect and repair DNA damage, exacerbating the DNMT3Amut

phenotype. Additionally, DNMT3Amut cells display reduced CHK1

phosphorylation, along with diminished downstream p53

phosphorylation/stabilization and apoptotic signaling, further

contributing to chemoresistance (81).

DNA mismatch repair (MMR) is a conserved process

that identifies and corrects spontaneously misincorporated bases

during DNA replication, ensuring genomic integrity (82). Impairment in MMR leads to

microsatellite instability (MSI), a hallmark found in >20

different tumor types (82). Werner

helicase (WRN), part of the RecQ family of DNA helicases, is

critical in maintaining genomic stability, DNA repair, replication,

transcription and telomere maintenance. WRN has been identified as

a synthetic lethal target in deficient (d)MMR/MSI-H cancers, being

essential for the survival of dMMR/MSI-H cells both in vitro

and in vivo. Knockdown of WRN in these cells induces

double-stranded DNA breaks and significant genomic instability,

leading to apoptosis. WRN inhibition has proven effective in dMMR

colorectal cancer models that develop secondary resistance to

broad-spectrum chemotherapeutic agents such as irinotecan,

oxaliplatin, or 5-FU, as well as combinations involving epidermal

growth factor receptor (EGFR) monoclonal antibodies and BRAF or

NTRK inhibitors (82).

While enhanced DNA repair can contribute to

chemotherapy resistance, molecular alterations in MMR-related genes

can also drive tumorigenesis and progression (83). Studies have revealed that cells

exposed to targeted therapies (for example, EGFR inhibitors or BRAF

inhibitors) temporarily downregulate the expression of DDR-related

genes, including those involved in MMR and HR. This transient

suppression of DDR capacity is reversible, with gene expression

returning to normal levels after the cessation of targeted therapy

(84). The presence of DNA damage

and repair mechanisms within tumor cells-and whether these

mechanisms are actively engaged to prevent apoptosis-presents a

strategic opportunity for combination therapies. Exploiting the

transient DDR deficiencies that tumors experience during treatment

could enhance the effectiveness of anticancer therapies.

Effect of TME on chemotherapy

resistance

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is characterized by

several distinct features that differentiate it from normal

tissues, including acidic pH, hypoxia, elevated ROS, upregulated

antioxidant systems and overexpression of specific enzymes

(47). Hypoxia, a hallmark of

tumors, arises from the imbalance between oxygen consumption and

vascular oxygen supply in tumor tissues and is a critical factor in

promoting tumorigenesis and progression. This condition drives

metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells, allowing them to adapt to

the hypoxic TME (85). While

platinum-based chemotherapeutic drugs target rapidly proliferating

cancer cells, the quiescent cell population, often associated with

hypoxia, remains largely unaffected by such treatments.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), composed of alpha and beta

subunits, is a key regulator of cellular hypoxic responses. HIF-1α

specifically modulates the cellular response to hypoxia,

influencing processes such as apoptosis, proliferation,

vasodilation, energy metabolism and angiogenesis. Salidroside has

been identified to promote the degradation of HIF-1α, and its

administration in combination with platinum drugs can reverse

platinum resistance and inhibit metastasis induced by the hypoxic

TME (86).

Hypoxia also contributes to tumor growth by

affecting exosome secretion. Exosomes, nanoscale extracellular

vesicles (30–150 nm in diameter), facilitate the transfer of

proteins, RNA and other molecules between cells within the TME,

thereby influencing the behavior of surrounding cells. In the

context of EGFR-mutant lung cancer, a common target in clinical

therapy, drug resistance remains a significant challenge. It has

been demonstrated that cells with wild-type EGFR can be

internalized by EGFR-mutant cancer cells via clathrin-dependent

endocytosis, leading to the acquisition of a wild-type EGFR

phenotype. This phenotypic change activates downstream PI3K/AKT and

MAPK signaling pathways, thereby triggering drug resistance

(87). Additionally, the

EGFR-targeted drug oxitinib has been shown to promote exosome

release by upregulating Rab GTPase, further contributing to drug

resistance (87).

In acute myeloid leukemia (AML), the apoptosis

repressor with caspase recruitment domain (ARC) protein serves as a

potent independent marker of poor prognosis. ARC activates NF-κB,

leading to increased IL1β expression in AML cells, which in turn

elevates the expression of CCL2, CCL4 and CXCL12 in mesenchymal

stromal cells (MSCs) (88). When

AML cells are co-cultured with MSCs, IL1β expression is further

elevated, driving AML cell migration towards CCL2, CCL4 and CXCL12.

Inhibition of IL1β has been revealed to reduce AML cell migration

(88). Moreover, co-cultures of AML

and MSCs have been found to increase Cox-2 expression in MSCs

through PGE2-mediated signaling in an ARC/IL1β-dependent manner,

thereby modulating ARC expression and enhancing the chemoresistance

of AML cells (89).

Microorganisms within the TME are significant

contributors to cancer progression and treatment resistance. A

study on ovarian epithelial cancer revealed that antibiotic use

during chemotherapy was linked to poorer overall survival,

primarily due to bacterial imbalance. Stool analysis indicated that

co-treatment with antibiotics and cisplatin disrupted 49

non-resistant intestinal microbes in mice, leading to accelerated

tumor growth and cisplatin resistance compared with mice treated

with chemotherapy alone. This resistance was characterized by

reduced apoptosis, increased DNA damage repair and enhanced

angiogenesis. However, transplanting cecal microbes from control

mice into the co-treated mice restored cisplatin sensitivity

(90). Similarly, L-lactic acid

produced by Lactobacillus iners in tumors reprograms

cervical tumor metabolism, enhancing resistance to gemcitabine

combined with 5-FU chemotherapy (91). Fusobacterium nucleatum and

its metabolite succinic acid induce resistance to anti-PD-1

monoclonal antibody immune checkpoint blockade therapy in

colorectal cancer by inhibiting key immune pathways and reducing

CD8+ T cell migration into the TME (92). In addition, telomelysin OBP-301, a

telomerase-specific, replication-competent oncolytic adenovirus

with an hTERT promoter upstream of the E1 gene, has been

demonstrated to enhance Akt phosphorylation in hepatocellular

carcinoma cells. However, the histone deacetylase inhibitor AR42

reduces telomerase-induced Akt phosphorylation and enhances

telomerase-induced apoptosis. Combined treatment with telomelysin

and AR42 demonstrated synergistic anti-hepatocellular carcinoma

effects (93).

Tumor cells do not exist in isolation; their

characteristics are intricately linked to the TME. The interactions

between tumor cells and other cells, including bacteria within the

microenvironment, as well as the unique pH and hypoxic conditions,

profoundly influence tumor cell characteristics and drug

sensitivity. Inflammation within the TME promotes drug resistance

by activating pro-inflammatory cytokines and signaling pathways.

This chronic inflammatory response not only drives tumor growth and

metastasis but also significantly reduces cancer cell sensitivity

to chemotherapy through the regulation of resistance protein

expression (94). Investigating how

the microenvironment contributes to chemotherapy resistance may

provide new therapeutic strategies that focus on targeting the TME,

rather than the tumor cells alone.

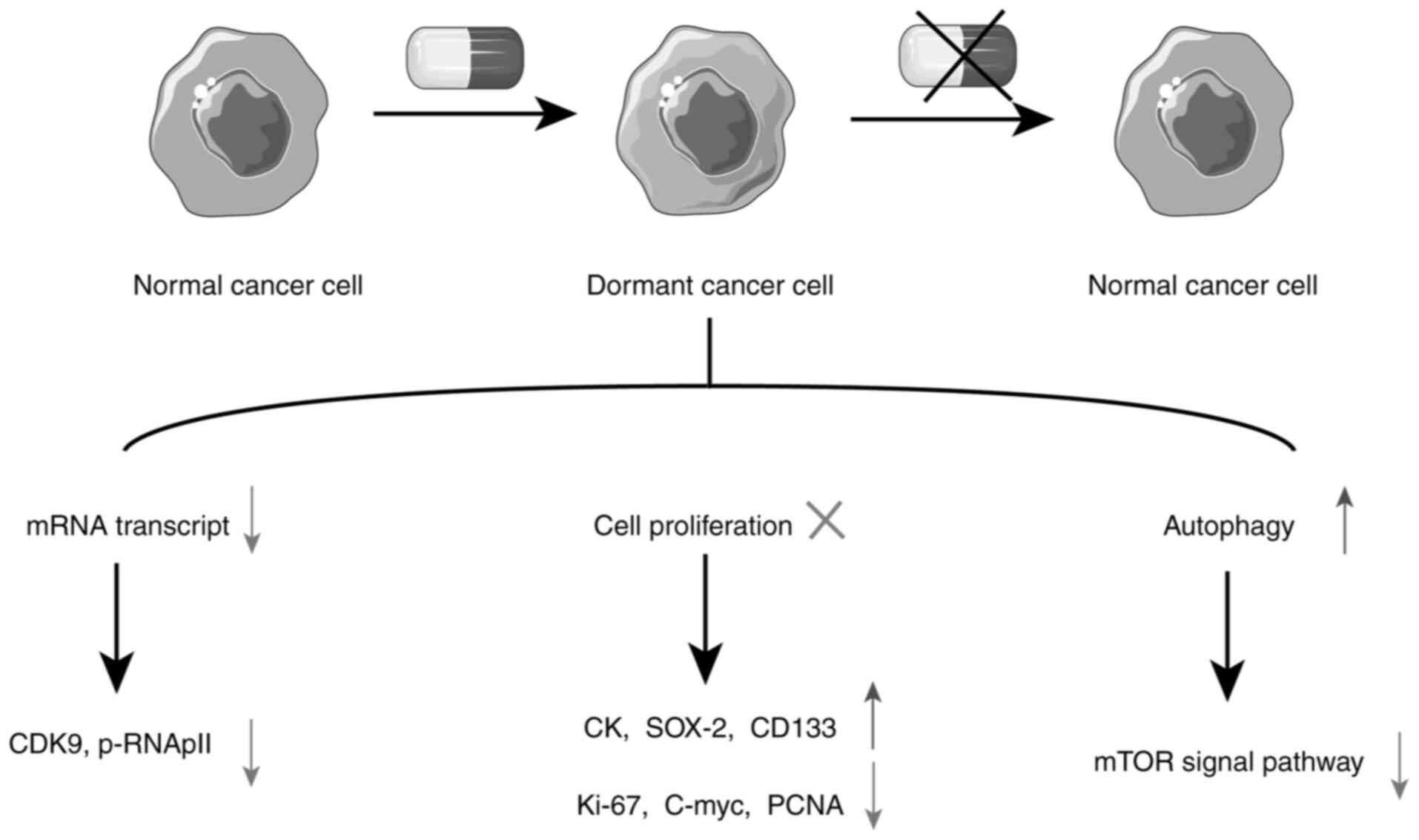

Tumor cells escape from the pressure of

chemotherapy through dormancy

What is tumor cell dormancy?

Tumor recurrence years after chemotherapy or surgery

is often attributed to the presence of dormant cancer cells within

the tumor mass. Dormancy refers to a reversible state in which

cells cease division, exhibit low metabolic activity, and reduce

mRNA synthesis, yet remain responsive to external stimuli (95–97).

Dormancy can occur in early metastatic sites as well as in residual

lesions following chemotherapy (98–100).

Traditionally, cellular dormancy was viewed as a quiescent state

associated with the G0 phase of the cell cycle (101). However, it was recently suggested

that these non-dividing cells exist in a slow-cycling survival

mode, akin to embryonic stasis, and are therefore also known as

slow-cycling or drug-resistant persister cells (100).

Dormant tumor cells differ from tumor stem-like

cells, though there is overlap between the two. Tumor stem-like

cells are generally considered a subset of dormant tumor cells,

possessing the ability to remain dormant, yet not all dormant cells

possess stem cell properties such as self-renewal and

differentiation.

Most chemotherapeutic agents target proliferating

cells, allowing tumor cells to evade therapeutic stress by entering

a dormant state, thereby contributing to drug resistance (102,103). Although some reactivated cells may

remain sensitive to chemotherapy, the prognosis for patients with

recurrent tumors is often poor (100,104). The induction of dormancy in

response to drug treatment underscores the importance of accurately

identifying dormant tumor cells to improve guidance of clinical

drug use (105).

How to determine tumor cell

dormancy

Next-generation sequencing and lentiviral barcoding

experiments have revealed that xenograft tumors arising after

chemotherapy-induced dormancy do not exhibit significant reductions

in genetic or barcode complexity, indicating that dormancy is a

non-genetic state (100). Tumor

cell dormancy functions as a survival strategy, enabling cells to

adapt to external stress rather than representing a distinct

subpopulation; all tumor cells have the potential to enter a

dormant state (100). Currently,

there are no specific markers for identifying dormant tumor cells.

Detection primarily relies on immunohistochemistry,

immunofluorescence and western blot analysis of relevant

indicators, typically associated with tumor stem-like cells, such

as CK, Sox-2 and CD133, as well as dormancy activation markers

including Ki-67, cyclin D1, C-myc, VEGF and proliferating cell

nuclear antigen. TUNEL staining is also commonly used (106). Additionally, tracking the mitotic

kinetics of dormant tumor cells with lipophilic fluorescent dyes

serves as another method for determining cellular dormancy

(107). One of the key features of

dormant cells is reduced mRNA synthesis activity. Since mRNA is

transcribed by RNA polymerase II (RNApII), low RNApII

phosphorylation is highly specific to dormant cells, with

cyclin-dependent kinase 9 (CDK9) being critical for

RNApII-dependent gene transcription. The Optical Stem Cell Activity

Reporter system distinguishes dormant cells from proliferating

cells by detecting intracellular transcriptional status (95). In vitro immobilization

techniques can also be employed to isolate and recover dormant

cancer cells. This can be achieved using a microfluidic

flow-focusing device that allows individual cells coated with

agarose to be immobilized and survive on silica gel wells.

Typically, actively proliferating cells do not survive the

immobilization process, but dormant cells can be re-awakened by

in situ digestion of the agarose gel and effectively

recovered through magnetic separation of the silica gel (108) (Fig.

4).

Mechanisms of tumor cell dormancy

In breast cancer, the tyrosine kinase receptor TIE2

induces cell dormancy and resistance to 5-FU and adriamycin by

activating the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors

CDKN1A and CDKN1B (109). The

treatment of diabetes with metformin or a high-fat diet can promote

the survival of dormant ER+ breast cancer cells through

the upregulation of the AMPK signaling pathway and the activation

of fatty acid oxidation (105).

FBX8, a member of the F-box protein family, plays a role in

maintaining tumor cell dormancy under the pressure of chemotherapy

with drugs such as oxaliplatin and 5-FU. Overexpression of FBX8 in

dormant cells enhances the degradation of HIF-1α, CDK4 and C-Myc

via the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, thereby prolonging the

dormancy period, whereas FBX8 knockdown shortens this period

(106). In paclitaxel-treated

non-small cell lung cancer, regulator of G protein signaling 2

(RGS2) mediates translational arrest and dormancy in tumor cells

through the proteasomal degradation of activating transcription

factor 4, while antagonizing RGS2 in the endoplasmic reticulum

pathway induces apoptosis in dormant cells (110). CXCL10 has been identified as a

factor that can reactivate the proliferation of dormant tumor cells

within micro-metastases, making it a potential therapeutic target

for addressing tumor dormancy (111). Elevated intracellular copper

levels are generally associated with tumor progression; however,

copper carrier drugs such as elesclomol can induce cell death in a

copper-ion-dependent manner. Consequently, blocking copper uptake

can inhibit tumor cell proliferation and induce dormancy, reducing

overall cell mortality (112,113).

The MAPK/ERK signaling pathway, a classical

proliferation-related pathway, also plays a role in the induction

of cell dormancy. In EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer, the

combination of EGFR inhibitors and TKIs drives tumor cells into a

senescence-like dormant state characterized by high YAP/TEAD

activity, owing to ERK1/2 blockade. Inhibiting YAP and TEAD in

conjunction with EGFR/MEK inhibition has been shown to enhance

apoptosis, effectively depleting dormant cells (114).

Myc is a critical gene that regulates tumor cell

growth and proliferation. Inhibition of Myc or

bromodomain-containing protein 4 prompts tumor cells to enter

dormancy by reducing the initiation of apoptosis. Conversely,

inducing Myc expression increases chemotherapy sensitivity,

suggesting that maintaining dormancy through Myc inhibition

post-chemotherapy or disrupting dormancy by inhibiting CDK9 could

be promising therapeutic strategies against dormant tumor cells

(115).

Autophagy plays a pivotal role in cellular stress

response by eliminating damaged organelles, misfolded proteins and

abnormal protein aggregates, regulating mitochondrial mass, and

preventing the accumulation of ROS, thereby aiding cell survival

(102). Studies have revealed that

when tumor cells enter a dormant state, the activity of the

autophagy-related mTOR pathway decreases, while

autophagy-associated phenotypes increase (102,116). Conversely, inhibiting autophagy

with drugs such as chloroquine can reawaken dormant cells,

prompting them to re-enter the proliferative state (117). The combination of autophagy

inhibitors with chemotherapeutic agents has been found to induce

the death of dormant cells (100,118). Thus, autophagy is integral not

only to the initiation and maintenance of dormancy but also to the

transition from dormancy to proliferation.

The TME significantly contributes to inducing tumor

cell dormancy. In a mouse model of breast cancer metastasis, Ki-67

immunofluorescence revealed that tumor cells metastasizing to the

lungs entered a dormant state. This metastatic dormancy was

dependent on the presence of T cells, particularly

CD39+PD-1+CD8+ T cells, which

induced cell cycle arrest by secreting IFNγ and TNF-α, thereby

promoting a dormant phenotype (119). Hypoxia, another key feature of the

TME, also influences dormancy. Under hypoxic conditions, the

expression of CSN8, a subunit of the COP9 signalosome, is elevated.

This upregulation is accompanied by increased levels of dormancy

markers (NR2F1, DEC2 and p27) and hypoxia markers (HIF-1α and

GLUT1), along with decreased expression of the proliferation marker

Ki-67, suggesting that CSN8 plays a role in regulating

hypoxia-induced dormancy (120).

While most chemotherapeutic agents target

proliferating cells and are ineffective against dormant cells,

nimustine has shown efficacy in targeting dormant cells in

BRCA1-deficient mice. Platinum-induced intra-strand crosslinks can

be repaired by nucleotide excision during the G0-G1 phase; however,

in BRCA1-deficient tumor cells, nimustine-induced inter-strand

crosslink repair is impaired, leading to cell death (98).

The study of tumor cell dormancy and its role in

chemotherapy resistance remains an emerging field. The definitions,

markers and specific mechanisms of tumor cell dormancy remain

incompletely understood. However, continued research is essential

to elucidate how tumor cells evade chemotherapy and survive as

micro-metastases, ultimately improving therapeutic strategies.

Conclusion and future directions

In recent decades, the molecular mechanisms

underlying chemoresistance have become increasingly

well-understood. These mechanisms include reduced drug uptake into

cells, increased drug efflux, GSH-mediated drug neutralization,

nuclear pore closure, enhanced DNA repair, promotion of tumor cell

dormancy, and the complex interactions between tumor cells and the

TME. Although the mechanisms underlying chemotherapy resistance in

tumor cells are increasingly well understood, their complexity in

clinical practice presents significant challenges. For example, the

use of inhibitors targeting multidrug resistance transporter

proteins such as MDR1 is complicated by their role in immune

function. Literature indicates that CD8+ T cells secrete

various cytokines to mediate immune responses and exert cytotoxic

effects on viruses and tumor cells, processes in which MDR1 plays a

critical role. MDR1 is essential for the development of naive

CD8+ T cells, regulated primarily by Runt-Related

transcription factors, which help inhibit oxidative stress, enhance

cell survival, and protect the mitochondrial function of nascent

CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Therefore, inhibiting MDR1

in patients with cancers could impair immune function, potentially

leading to treatment failure (121).

The development of nanomaterials designed to deliver

chemotherapeutic agents directly to specific tumor sites or

intracellular targets is a rapidly expanding area of research aimed

at reversing chemoresistance. For example, a nanomaterial

containing an iron oxide core has been engineered to deliver the

cytotoxic agent adriamycin and the TLR3 agonist polyinosinic:

Polycytidylic acid (Poly IC) to both breast cancer and dendritic

cells. The Endoglin-binding peptide on the nanomaterial targets

triple-negative breast cancer cells, inducing apoptosis through

multiple mechanisms, thereby inhibiting tumor growth and

metastasis. This approach has shown significant success in

prolonging the survival of mouse models with aggressive and

resistant triple-negative breast cancer metastases (122). Current strategies to combat

GSH-mediated cellular resistance focus on GSH depletion or

targeting GST. For instance, ethacraplatin, a platinum prodrug,

inhibits GST by releasing ethacrynic acid, and encapsulating this

compound in nanomicelles has been identified to enhance the

intracellular accumulation of cisplatin (123).

Some polysulfides have been developed to target high

GSH levels in tumor cells, serving as a prodrug backbone that also

reverses multidrug resistance (5,124).

Additionally, nanocarriers such as dendritic mesoporous silica

nanoparticles can integrate components such as ultrasmall

Fe3O4 nanoparticles, Mn2+ ions and

the glutaminase inhibitor Telaglenastat (CB-839) into their large

mesopores to form nanodrugs. These nanodrugs exhibit

peroxidase-mimetic activity under acidic conditions, catalyzing the

decomposition of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

into hydroxyl radicals (−OH) and depleting existing GSH while

blocking endogenous GSH synthesis. This process enhances

ROS-mediated tumor catalytic therapy (125). Given the ongoing challenges with

traditional inhibitors in combating chemotherapy resistance, the

development of new nanomaterials represents a promising strategy

for overcoming multidrug resistance in tumors, and it is expected

to be a key focus of future research.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was partially supported by the Natural Science

Foundation of Hunan Province (2023JJ50135, 2023JJ30521), the

Projects of the Health Commission of Hunan Province (202201043124),

the Aid Program for Science and Technology Innovative Research Team

in Higher Educational Institutions of Hunan Province [No.

(2023)233] and the Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan

(grant no. 21B0444).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

XW and WHZ conceived and designed the analysis,

conducted the research, and drafted the manuscript. LHX created the

figures. LYZ and PL contributed to the revision and polishing of

the manuscript. ZL, WJG, QQ, DLC and XZ were involved in the

conception and design of the analysis. XZ made significant

contributions to the discussion of the content and reviewed, edited

and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Miller KD, Nogueira L, Devasia T, Mariotto

AB, Yabroff KR, Jemal A, Kramer J and Siegel RL: Cancer treatment

and survivorship statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:409–436.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE and Jemal

A: Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 72:7–33. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K,

Chen R, Li L, Wei W and He J: Cancer incidence and mortality in

China, 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2:1–9. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Bukowski K, Kciuk M and Kontek R:

Mechanisms of multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Int J

Mol Sci. 21:32332020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Xiao X, Wang K, Zong Q, Tu Y, Dong Y and

Yuan Y: Polyprodrug with glutathione depletion and cascade drug

activation for multi-drug resistance reversal. Biomaterials.

270:1206492021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Bedard PL, Hyman DM, Davids MS and Siu LL:

Small molecules, big impact: 20 Years of targeted therapy in

oncology. Lancet. 395:1078–1088. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Li X, Li M, Huang M, Lin Q, Fang Q, Liu J,

Chen X, Liu L, Zhan X, Shan H, et al: The multi-molecular

mechanisms of tumor-targeted drug resistance in precision medicine.

Biomed Pharmacother. 150:1130642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Phan TG and Croucher PI: The dormant

cancer cell life cycle. Nat Rev Cancer. 20:398–411. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Chen X, Momin A, Wanggou S, Wang X, Min

HK, Dou W, Gong Z, Chan J, Dong W, Fan JJ, et al: Mechanosensitive

brain tumor cells construct blood-tumor barrier to mask

chemosensitivity. Neuron. 111:30–48. e142023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Inoue T, Aoyama-Ishikawa M, Uemura M,

Kohama K, Fujisaki N, Murakami H, Yamada T and Hirata J: The role

of death receptor signaling pathways in mouse Sertoli cell

avoidance of apoptosis during LPS- and IL-18-induced inflammatory

conditions. J Reprod Immunol. 158:1039702023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Russo M, Crisafulli G, Sogari A, Reilly

NM, Arena S, Lamba S, Bartolini A, Amodio V, Magrì A, Novara L, et

al: Adaptive mutability of colorectal cancers in response to

targeted therapies. Science. 366:1473–1480. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Diaz LA Jr, Williams RT, Wu J, Kinde I,

Hecht JR, Berlin J, Allen B, Bozic I, Reiter JG, Nowak MA, et al:

The molecular evolution of acquired resistance to targeted EGFR

blockade in colorectal cancers. Nature. 486:537–540. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Zheng N, Fang J, Xue G, Wang Z, Li X, Zhou

M, Jin G, Rahman MM, McFadden G and Lu Y: Induction of tumor cell

autosis by myxoma virus-infected CAR-T and TCR-T cells to overcome

primary and acquired resistance. Cancer Cell. 40:973–985.e7. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Hirota K, Ooka M, Shimizu N, Yamada K,

Tsuda M, Ibrahim MA, Yamada S, Sasanuma H, Masutani M and Takeda S:

XRCC1 counteracts poly(ADP ribose)polymerase (PARP) poisons,

olaparib and talazoparib, and a clinical alkylating agent,

temozolomide, by promoting the removal of trapped PARP1 from broken

DNA. Genes Cells. 27:331–344. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Ovejero S, Soulet C and Moriel-Carretero

M: The alkylating agent Methyl methanesulfonate triggers lipid

alterations at the inner nuclear membrane that are independent from

its DNA-damaging ability. Int J Mol Sci. 22:74612021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Ghosh S: Cisplatin: The first metal based

anticancer drug. Bioorg Chem. 88:1029252019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Fetoni AR, Paciello F and Troiani D:

Cisplatin chemotherapy and cochlear damage: Otoprotective and

chemosensitization properties of polyphenols. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 36:1229–1245. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Curry JN and McCormick JA:

Cisplatin-induced kidney injury: Delivering the goods. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 33:255–256. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Balboni B, El Hassouni B, Honeywell RJ,

Sarkisjan D, Giovannetti E, Poore J, Heaton C, Peterson C, Benaim

E, Lee YB, et al: RX-3117 (fluorocyclopentenyl cytosine): A novel

specific antimetabolite for selective cancer treatment. Expert Opin

Investig Drugs. 28:311–322. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Guo J, Yu Z, Das M and Huang L: Nano

codelivery of oxaliplatin and folinic acid achieves synergistic

chemo-immunotherapy with 5-fluorouracil for colorectal cancer and

liver metastasis. Acs Nano. 14:5075–5089. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Li Z, Li C, Wu Q, Tu Y, Wang C, Yu X, Li

B, Wang Z and Sun S and Sun S: MEDAG enhances breast cancer

progression and reduces epirubicin sensitivity through the

AKT/AMPK/mTOR pathway. Cell Death Dis. 12:972021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Li J, Yu K, Pang D, Wang C, Jiang J, Yang

S, Liu Y, Fu P, Sheng Y, Zhang G, et al: Adjuvant capecitabine with

docetaxel and cyclophosphamide plus epirubicin for triple-negative

breast cancer (CBCSG010): An open-label, randomized, multicenter,

phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 38:1774–1784. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

You JH, Lee J and Roh JL: PGRMC1-dependent

lipophagy promotes ferroptosis in paclitaxel-tolerant persister

cancer cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 40:3502021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Chen Y, Liu R, Li C, Song Y, Liu G, Huang

Q, Yu L, Zhu D, Lu C, Lu A, et al: Nab-paclitaxel promotes the

cancer-immunity cycle as a potential immunomodulator. Am J Cancer

Res. 11:3445–3460. 2021.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Elshamy AM, Salem OM, Safa MAE, Barhoma

RAE, Eltabaa EF, Shalaby AM, Alabiad MA, Arakeeb HM and Mohamed HA:

Possible protective effects of CO Q10 against vincristine-induced

peripheral neuropathy: Targeting oxidative stress, inflammation,

and sarmoptosis. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 36:e229762022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Rajković S, Živković MD and Djuran MI:

Reactions of dinuclear Platinum(II) complexes with peptides. Curr

Protein Pept Sci. 17:95–105. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kim ES, Tang X, Peterson DR, Kilari D,

Chow CW, Fujimoto J, Kalhor N, Swisher SG, Stewart DJ, Wistuba II

and Siddik ZH: Copper transporter CTR1 expression and tissue

platinum concentration in non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer.

85:88–93. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Lv X, Song J, Xue K, Li Z, Li M, Zahid D,

Cao H, Wang L, Song W, Ma T, et al: Core fucosylation of copper

transporter 1 plays a crucial role in cisplatin-resistance of

epithelial ovarian cancer by regulating drug uptake. Mol Carcinog.

58:794–807. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kalayda GV, Wagner CH and Jaehde U:

Relevance of copper transporter 1 for cisplatin resistance in human

ovarian carcinoma cells. J Inorg Biochem. 116:1–10. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Gao H, Zhang S, Hu T, Qu X, Zhai J, Zhang

Y, Tao L, Yin J and Song Y: Omeprazole protects against

cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity by alleviating oxidative stress,

inflammation, and transporter-mediated cisplatin accumulation in

rats and HK-2 cells. Chem Biol Interact. 297:130–140. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Naka A, Takeda R, Shintani M, Ogane N,

Kameda Y, Aoyama T, Yoshikawa T and Kamoshida S: Organic cation

transporter 2 for predicting cisplatin-based neoadjuvant

chemotherapy response in gastric cancer. Am J Cancer Res.

5:2285–2293. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Hucke A, Rinschen MM, Bauer OB, Sperling

M, Karst U, Köppen C, Sommer K, Schröter R, Ceresa C, Chiorazzi A,

et al: An integrative approach to cisplatin chronic toxicities in

mice reveals importance of organic cation-transporter-dependent

protein networks for renoprotection. Arch Toxicol. 93:2835–2848.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Verhalen B, Dastvan R, Thangapandian S,

Peskova Y, Koteiche HA, Nakamoto RK, Tajkhorshid E and Mchaourab

HS: Energy transduction and alternating access of the mammalian ABC

transporter P-glycoprotein. Nature. 543:738–741. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Alam A, Kowal J, Broude E, Roninson I and

Locher KP: Structural insight into substrate and inhibitor

discrimination by human P-glycoprotein. Science. 363:753–756. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Pasello M, Giudice AM and Scotlandi K: The

ABC subfamily A transporters: Multifaceted players with incipient

potentialities in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 60:57–71. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Hanssen KM, Haber M and Fletcher JI:

Targeting multidrug resistance-associated protein 1

(MRP1)-expressing cancers: Beyond pharmacological inhibition. Drug

Resist Updat. 59:1007952021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kim Y and Chen J: Molecular structure of

human P-glycoprotein in the ATP-bound, outward-facing conformation.

Science. 359:915–919. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Miyamoto S, Azuma K, Ishii H, Bessho A,

Hosokawa S, Fukamatsu N, Kunitoh H, Ishii M, Tanaka H, Aono H, et

al: Low-dose erlotinib treatment in elderly or frail patients with

EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer: A multicenter

phase 2 trial. JAMA Oncol. 6:e2012502020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Robey RW, Pluchino KM, Hall MD, Fojo AT,

Bates SE and Gottesman MM: Revisiting the role of ABC transporters

in multidrug-resistant cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 18:452–464. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Carvalho DM, Richardson PJ, Olaciregui N,

Stankunaite R, Lavarino C, Molinari V, Corley EA, Smith DP, Ruddle

R, Donovan A, et al: Repurposing vandetanib plus everolimus for the

treatment of ACVR1-mutant diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. Cancer

Discov. 12:416–431. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Cole SPC: Targeting multidrug resistance

protein 1 (MRP1, ABCC1): Past, present, and future. Annu Rev

Pharmacol Toxicol. 54:95–117. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Johnson ZL and Chen J: ATP binding enables

substrate release from multidrug resistance protein 1. Cell.

172:81–89.e10. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Vulsteke C, Lambrechts D, Dieudonné A,

Hatse S, Brouwers B, van Brussel T, Neven P, Belmans A, Schöffski

P, Paridaens R and Wildiers H: Genetic variability in the multidrug

resistance associated protein-1 (ABCC1/MRP1) predicts hematological

toxicity in breast cancer patients receiving (neo-)adjuvant

chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide

(FEC). Ann Oncol. 24:1513–1525. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Cole SPC: Multidrug resistance protein 1

(MRP1, ABCC1), a ‘multitasking’ ATP-binding cassette (ABC)

transporter. J Biol Chem. 289:30880–30888. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Taylor NMI, Manolaridis I, Jackson SM,

Kowal J, Stahlberg H and Locher KP: Structure of the human

multidrug transporter ABCG2. Nature. 546:504–509. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kowal J, Ni D, Jackson SM, Manolaridis I,

Stahlberg H and Locher KP: Structural basis of drug recognition by

the multidrug transporter ABCG2. J Mol Biol. 433:1669802021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Niu B, Liao K, Zhou Y, Wen T, Quan G, Pan

X and Wu C: Application of glutathione depletion in cancer therapy:

Enhanced ROS-based therapy, ferroptosis, and chemotherapy.

Biomaterials. 277:1211102021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zhang J, Bai J, Zhou Q, Hu Y, Wang Q, Yang

L, Chen H, An H, Zhou C, Wang Y, et al: Glutathione prevents high

glucose-induced pancreatic fibrosis by suppressing pancreatic

stellate cell activation via the ROS/TGFβ/SMAD pathway. Cell Death

Dis. 13:4402022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Chen M, Zhao S, Zhu J, Feng E, Lv F, Chen

W, Lv S, Wu Y, Peng X and Song F: Open-source and

reduced-expenditure nanosystem with ROS self-amplification and

glutathione depletion for simultaneous augmented

chemodynamic/photodynamic therapy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces.

14:20682–20692. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Cheng X, Xu HD, Ran HH, Liang G and Wu FG:

Glutathione-depleting nanomedicines for synergistic cancer therapy.

ACS Nano. 15:8039–8068. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Gao P, Yang X, Xue YW, Zhang XF, Wang Y,

Liu WJ and Wu XJ: Promoter methylation of glutathione S-transferase

pi1 and multidrug resistance gene 1 in bronchioloalveolar carcinoma

and its correlation with DNA methyltransferase 1 expression.

Cancer. 115:3222–3232. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Xu Y, Han X, Li Y, Min H, Zhao X, Zhang Y,

Qi Y, Shi J, Qi S, Bao Y and Nie G: Sulforaphane mediates

glutathione depletion via polymeric nanoparticles to restore

cisplatin chemosensitivity. ACS Nano. 13:13445–13455. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Oshimori N, Oristian D and Fuchs E: TGF-β

promotes heterogeneity and drug resistance in squamous cell

carcinoma. Cell. 160:963–976. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Zhang KR, Zhang YF, Lei HM, Tang YB, Ma

CS, Lv QM, Wang SY, Lu LM, Shen Y, Chen HZ and Zhu L: Targeting

AKR1B1 inhibits glutathione de novo synthesis to overcome acquired

resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy in lung cancer. Sci Transl Med.

13:eabg64282021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Pang HH, Ke YC, Li NS, Chen YT, Huang CY,

Wei KC and Yang HW: A new lateral flow plasmonic biosensor based on

gold-viral biomineralized nanozyme for on-site intracellular

glutathione detection to evaluate drug-resistance level. Biosens

Bioelectron. 165:1123252020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Harris IS, Endress JE, Coloff JL, Selfors

LM, McBrayer SK, Rosenbluth JM, Takahashi N, Dhakal S, Koduri V,

Oser MG, et al: Deubiquitinases maintain protein homeostasis and

survival of cancer cells upon glutathione depletion. Cell Metab.

29:1166–1181.e6. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Stafford WC, Peng X, Olofsson MH, Zhang X,

Luci DK, Lu L, Cheng Q, Trésaugues L, Dexheimer TS, Coussens NP, et

al: Irreversible inhibition of cytosolic thioredoxin reductase 1 as

a mechanistic basis for anticancer therapy. Sci Transl Med.

10:eaaf74442018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Zhang X, Wang M, Feng J, Qin B, Zhang C,

Zhu C, Liu W, Wang Y, Liu W, Huang L, et al: Multifunctional

nanoparticles co-loaded with Adriamycin and MDR-targeting siRNAs

for treatment of chemotherapy-resistant esophageal cancer. J

Nanobiotechnology. 20:1662022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Amort M, Nachbauer B, Tuzlak S, Kieser A,

Schepers A, Villunger A and Polacek N: Expression of the vault RNA

protects cells from undergoing apoptosis. Nat Commun. 6:70302015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Liu S, Hao Q, Peng N, Yue X, Wang Y, Chen

Y, Wu J and Zhu Y: Major vault protein: A virus-induced host factor

against viral replication through the induction of type-I

interferon. Hepatology. 56:57–66. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Bai H, Wang C, Qi Y, Xu J, Li N, Chen L,

Jiang B, Zhu X, Zhang H, Li X, et al: Major vault protein

suppresses lung cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting STAT3

signaling pathway. BMC Cancer. 19:4542019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Shen W, Qiu Y, Li J, Wu C, Liu Z, Zhang X,

Hu X, Liao Y and Wang H: IL-25 promotes cisplatin resistance of

lung cancer cells by activating NF-κB signaling pathway to increase

of major vault protein. Cancer Med. 8:3491–3501. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lou L, Wang J, Lv F, Wang G, Li Y, Xing L,

Shen H and Zhang X: Y-box binding protein 1 (YB-1) promotes

gefitinib resistance in lung adenocarcinoma cells by activating AKT

signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition through targeting

major vault protein (MVP). Cell Oncol (Dordr). 44:109–133. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Yu X, Liu W, Wang Z, Wang H, Liu J, Huang

C, Zhao T, Wang X, Gao S, Ma Y, et al: CD73 induces gemcitabine

resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: A promising target

with non-canonical mechanisms. Cancer Lett. 519:289–303. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Yu H, Li M, He R, Fang P, Wang Q, Yi Y,

Wang F, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Chen A, et al: Major vault protein

promotes hepatocellular carcinoma through targeting interferon

regulatory factor 2 and decreasing p53 activity. Hepatology.

72:518–534. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Pilié PG, Tang C, Mills GB and Yap TA:

State-of-the-art strategies for targeting the DNA damage response

in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 16:81–104. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Gourley C, Balmaña J, Ledermann JA, Serra

V, Dent R, Loibl S, Pujade-Lauraine E and Boulton SJ: Moving from

poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase inhibition to targeting DNA repair and

DNA damage response in cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 37:2257–2269.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Pettitt SJ, Frankum JR, Punta M, Lise S,

Alexander J, Chen Y, Yap TA, Haider S, Tutt ANJ and Lord CJ:

Clinical BRCA1/2 reversion analysis identifies hotspot mutations

and predicted neoantigens associated with therapy resistance.

Cancer Discov. 10:1475–1488. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Ma J, Benitez JA, Li J, Miki S, Ponte de

Albuquerque C, Galatro T, Orellana L, Zanca C, Reed R, Boyer A, et

al: Inhibition of nuclear PTEN tyrosine phosphorylation enhances

glioma radiation sensitivity through attenuated DNA repair. Cancer

Cell. 35:504–518.e7. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Goodall J, Mateo J, Yuan W, Mossop H,

Porta N, Miranda S, Perez-Lopez R, Dolling D, Robinson DR, Sandhu

S, et al: Circulating cell-free DNA to guide prostate cancer

treatment with PARP inhibition. Cancer Discov. 7:1006–1017. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Dev H, Chiang TW, Lescale C, de Krijger I,

Martin AG, Pilger D, Coates J, Sczaniecka-Clift M, Wei W,

Ostermaier M, et al: Shieldin complex promotes DNA end-joining and

counters homologous recombination in BRCA1-null cells. Nat Cell

Biol. 20:954–965. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Schlacher K: PARPi focus the spotlight on

replication fork protection in cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 19:1309–1310.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Lord CJ and Ashworth A: Mechanisms of

resistance to therapies targeting BRCA-mutant cancers. Nat Med.

19:1381–1388. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Ray Chaudhuri A, Callen E, Ding X, Gogola

E, Duarte AA, Lee JE, Wong N, Lafarga V, Calvo JA, Panzarino NJ, et

al: Replication fork stability confers chemoresistance in

BRCA-deficient cells. Nature. 535:382–387. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Awah CU, Chen L, Bansal M, Mahajan A,

Winter J, Lad M, Warnke L, Gonzalez-Buendia E, Park C, Zhang D, et

al: Ribosomal protein S11 influences glioma response to TOP2

poisons. Oncogene. 39:5068–5081. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Wang Z, Zhu Q, Li X, Ren X, Li J, Zhang Y,

Zeng S, Xu L, Dong X and Zhai B: TOP2A inhibition reverses drug

resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma to regorafenib. Am J Cancer

Res. 12:4343–4360. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Mateo J, Carreira S, Sandhu S, Miranda S,

Mossop H, Perez-Lopez R, Nava Rodrigues D, Robinson D, Omlin A,

Tunariu N, et al: DNA-repair defects and olaparib in metastatic

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:1697–1708. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Mu Y, Lou J, Srivastava M, Zhao B, Feng

XH, Liu T, Chen J and Huang J: SLFN11 inhibits checkpoint

maintenance and homologous recombination repair. EMBO Rep.

17:94–109. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Gardner EE, Lok BH, Schneeberger VE,

Desmeules P, Miles LA, Arnold PK, Ni A, Khodos I, de Stanchina E,

Nguyen T, et al: Chemosensitive relapse in small cell lung cancer

proceeds through an EZH2-SLFN11 axis. Cancer Cell. 31:286–299.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Guryanova OA, Shank K, Spitzer B, Luciani

L, Koche RP, Garrett-Bakelman FE, Ganzel C, Durham BH, Mohanty A,

Hoermann G, et al: DNMT3A mutations promote anthracycline

resistance in acute myeloid leukemia via impaired nucleosome

remodeling. Nat Med. 22:1488–1495. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Picco G, Cattaneo CM, van Vliet EJ,

Crisafulli G, Rospo G, Consonni S, Vieira SF, Rodríguez IS,

Cancelliere C, Banerjee R, et al: Werner helicase is a

synthetic-lethal vulnerability in mismatch repair-deficient

colorectal cancer refractory to targeted therapies, chemotherapy,

and immunotherapy. Cancer Discov. 11:1923–1937. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Germano G, Lamba S, Rospo G, Barault L,

Magrì A, Maione F, Russo M, Crisafulli G, Bartolini A, Lerda G, et

al: Inactivation of DNA repair triggers neoantigen generation and

impairs tumour growth. Nature. 552:116–120. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Gay CM, Parseghian CM and Byers LA: This

is our cells under pressure: Decreased DNA damage repair in

response to targeted therapies facilitates the emergence of

drug-resistant clones. Cancer Cell. 37:5–7. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Guo W, Qiao T, Dong B, Li T, Liu Q and Xu

X: The effect of hypoxia-induced exosomes on anti-tumor immunity

and its implication for immunotherapy. Front Immunol.

13:9159852022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Qin Y, Liu HJ, Li M, Zhai DH, Tang YH,

Yang L, Qiao KL, Yang JH, Zhong WL, Zhang Q, et al: Salidroside

improves the hypoxic tumor microenvironment and reverses the drug

resistance of platinum drugs via HIF-1α signaling pathway.

EBioMedicine. 38:25–36. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Wu S, Luo M, To KKW, Zhang J, Su C, Zhang

H, An S, Wang F, Chen D and Fu L: Intercellular transfer of

exosomal wild type EGFR triggers osimertinib resistance in

non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 20:172021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

Carter BZ, Mak PY, Chen Y, Mak DH, Mu H,

Jacamo R, Ruvolo V, Arold ST, Ladbury JE, Burks JK, et al:

Anti-apoptotic ARC protein confers chemoresistance by controlling

leukemia-microenvironment interactions through a NFκB/IL1β

signaling network. Oncotarget. 7:20054–20067. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Carter BZ, Mak PY, Wang X, Tao W, Ruvolo

V, Mak D, Mu H, Burks JK and Andreeff M: An ARC-regulated

IL1β/Cox-2/PGE2/β-catenin/ARC circuit controls

leukemia-microenvironment interactions and confers drug resistance

in AML. Cancer Res. 79:1165–1177. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

Chambers LM, Esakov Rhoades EL, Bharti R,

Braley C, Tewari S, Trestan L, Alali Z, Bayik D, Lathia JD, Sangwan

N, et al: Disruption of the gut microbiota confers cisplatin

resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 82:4654–4669.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Johnston CD and Bullman S:

Bacteria-derived L-lactate fuels cervical cancer chemoradiotherapy

resistance. Trends Cancer. 10:97–99. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Jiang SS, Xie YL, Xiao XY, Kang ZR, Lin

XL, Zhang L, Li CS, Qian Y, Xu PP, Leng XX, et al: Fusobacterium

nucleatum-derived succinic acid induces tumor resistance to

immunotherapy in colorectal cancer. Cell Host Microbe.

31:781–797.e9. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Lin ZZ, Hu MC, Hsu C, Wu YM, Lu YS, Ho JA,

Yeh SH, Chen PJ and Cheng AL: Synergistic efficacy of

telomerase-specific oncolytic adenoviral therapy and histone

deacetylase inhibition in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer

Lett. 556:2160632023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Vaidya FU, Sufiyan Chhipa A, Mishra V,

Gupta VK, Rawat SG, Kumar A and Pathak C: Molecular and cellular

paradigms of multidrug resistance in cancer. Cancer Rep (Hoboken).