Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is a group of neoplastic

diseases that affect the renal parenchyma and represent 2–3% of all

cancer diagnoses (1). In 2022, the

GLOBOCAN database estimated the global incidence of RCC as 434,419

cases, which were associated with 155,702 deaths (2). RCC is more commonly diagnosed in men

(ratio men to women, 2:1), and in the sixth decade of life

(3). Up to 70% of patients are

incidentally diagnosed with RCC, 50% of them with metastatic

disease (4); although localized RCC

is curable, in up to 30% of patients this will progress to

metastatic disease, which has a median survival time of 6–10 months

(5). Among the different types of

RCCs, 80% of all diagnoses consist of the clear cell histological

variety (ccRCC), which is followed in frequency by the papillary

variant (10–15% of cases), the chromophobe cell variant (4–5% of

cases), and other molecularly defined phenotypes (<1% of cases)

(6).

The high rates of mortality that are observed in RCC

have been associated with factors such as the high prevalence of

advanced disease at diagnosis (7)

and the intrinsic chemoresistance of RCC tumors, which is mostly

related to apoptotic resistance, the upregulation of xenobiotic

excretion systems (8–10) and the metabolic dependence of such

tumors on the Warburg effect (11).

In total, <10% of patients with RCC will respond to cytotoxic

chemotherapy (12), which makes it

necessary to use novel approaches for which little clinical

information is available. Current RCC treatments can be grouped

into the following categories: cytotoxic chemotherapy, surgery,

local therapy, recombinant-cytokine therapy, targeted

anti-angiogenic therapy, immunotherapy [immune checkpoint blockade

(ICB)], and other therapies that include the use of inhibitors of

the mechanistic target of rapamycin pathway (Table I). Despite the broad diversity and

availability of RCC treatments, the need for a prognostic tool for

use in selecting the treatment of choice and evaluating the

clinical responses of patients remains a matter of controversy

(13). Treatment selection depends

on factors such as the histological variety, cellular grade and

clinical stage of the disease, as well as the failure of previous

treatments (14–16). In this regard, there are currently

several scales that have been validated for risk classification and

clinical decision-making in patients with RCC; among these, the

Heng score (International Metastatic RCC Database Consortium or

IMDC), the MSKCC scale (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center),

and the general physical status according to ECOG-PS criteria (the

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance score) (17–19)

stand out (Table II).

In the last decade, the use of monoclonal antibodies

for reversing the ‘exhaustion’ state in tumor infiltrating

lymphocytes (TILs) has proven to be a valuable treatment for

numerous solid tumors and hematologic cancers. In 2015, the

ChekMate-025 study demonstrated the efficacy of nivolumab (which

was initially approved for treating melanoma and non-small cell

lung cancer) in treating patients with RCC (20). In addition to nivolumab [which

blocks the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor], four

other monoclonal antibodies are currently approved for use in RCC,

all of which reverse the inhibition of lymphocyte immune effectors:

Pembrolizumab, which is also a PD-1 blocker; ipilimumab, which

blocks the cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4; and

atezolizumab/avelumab, which blocks PD-1 ligand in myeloid and

tumor cells and prevents PD-1 inhibitory signals in lymphocytes

(Table III) (20–30).

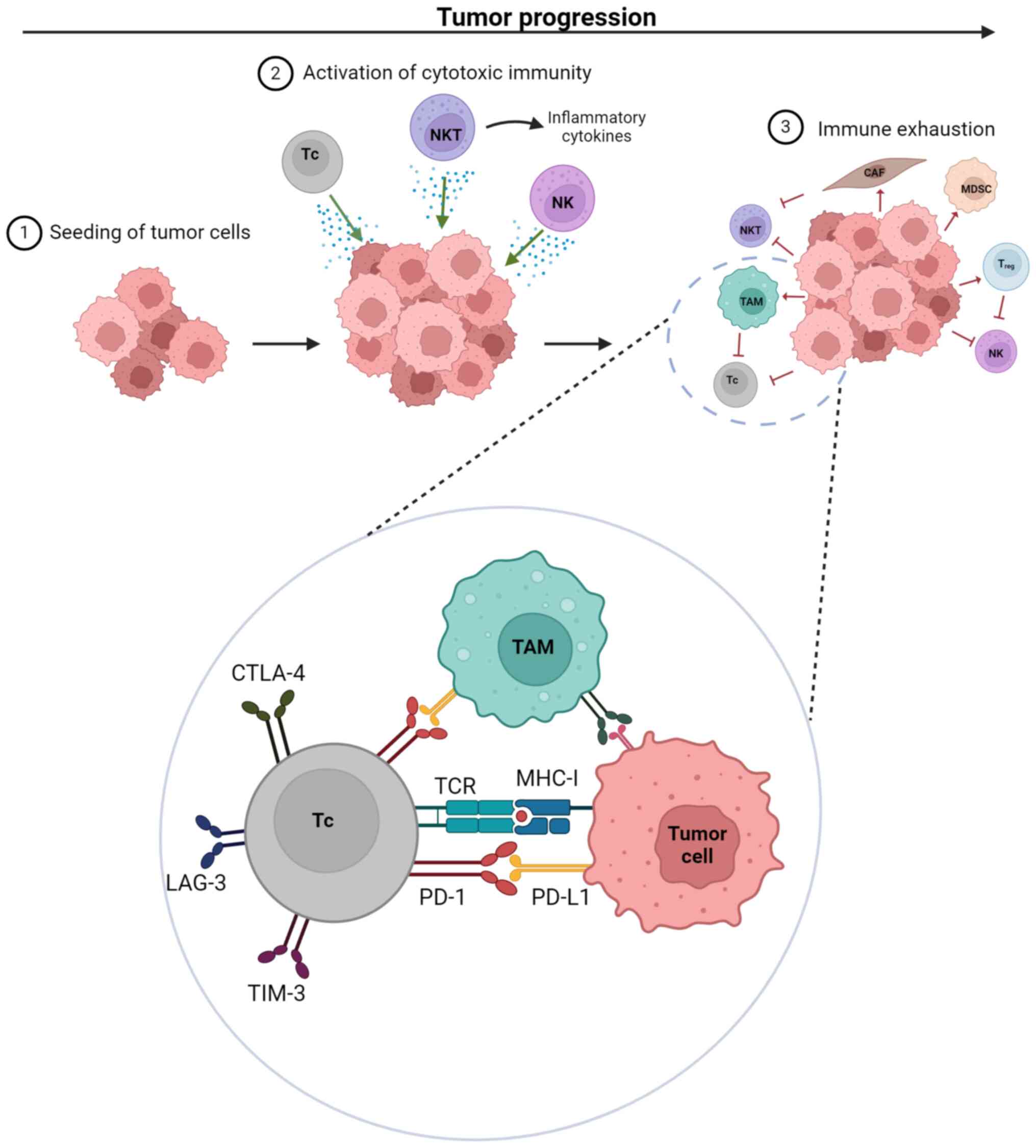

In the following section, the current knowledge of

the cellular mechanisms that lead to lymphocyte exhaustion within

the highly dynamic tumor-immune microenvironment (TIME) was

reviewed. It was concluded with a short description of experimental

biomarkers that have been used to predict the patients' responses

to ICB therapy.

The TIME comprises a network of interacting elements

within the tumor tissue that can be categorized as follows: Cells

(tumor, stroma and infiltrating immune cells), small soluble

elements (proteins, cytokines, growth factors, metabolites and

chemokines), and the extracellular matrix (31). The growth of tumors requires two

conditions: Cell transformation, whether genetic or acquired

(32) and immune dysfunction

(33). This second requirement

explains the association between immunodeficiency status and cancer

development (34). The clearance of

transformed cells from tissues requires the activation of cytotoxic

immunity that is achieved through the infiltration of

CD8+ cytotoxic lymphocytes and natural killer cells into

a tumor (35). Antitumor immunity

is so efficient that even though transformation and cell damage

occur over the course of every life, cancer develops only in a

small proportion of patients; the occurrence of cancer is promoted

by immune dysfunction.

Tumor cells proliferate at higher rates compared

with normal cells. This accelerated proliferation, which is linked

to metabolic changes that take place within the tumor bed, results

in dysfunctional local immunity and further selection of the

best-adapted tumor cells (36–38).

Cytotoxic chemotherapy exploits this increased proliferative rate,

and cytotoxic treatments are widely used in most neoplastic

diseases other than RCC. The peculiarities of RCC include its

intrinsic aggressive nature, its increased infiltration with

lipids, its high rate of metastasis, and its resistance to

cytotoxic chemotherapy (39). This

chemo-resistance has numerous causal factors, both intrinsic (or

genetic) and acquired. It is important to note that the epithelial

renal cells normally have secretion systems for xenobiotics and

intrinsic antioxidant mechanisms protecting the cells from toxic

damage (40). Given that most RCC

subtypes arise from renal epithelia, it is not surprising that such

mechanisms are enhanced in renal carcinoma. In addition, renal

tumor cells have increased expression of anti-apoptotic proteins

Bcl-2, Bcl-XL, ARC (apoptosis repressor with a caspase

recruitment domain) and XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis)

while pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bim are decreased.

Anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic proteins are regulated by NF-κB

and von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) pathways, respectively (8,10,41).

In addition, although the presence of TILs is a

favorable prognostic factor for most cancers, such infiltrative

cells are associated with poor outcomes in RCC (44,45).

Consequently, a hostile TIME develops that leads to the selection

of tumors that are resistant to hypoxia, acidosis and the low

availability of nutrients. In addition, a hostile TIME negatively

affects lymphocyte-dependent antitumor immunity (Fig. 1 and Table IV) (31,46–51).

Previous studies suggested that dysbiosis is an important element

to be considered when evaluating either the responses of tumors to

ICB or the general prognosis of patients with neoplastic diseases

(52,53). The molecular basis for lymphocyte

dysfunction involves several mechanisms that are associated with

peripheral tolerance, namely anergy, suppression and exhaustion

(54). Immune cell exhaustion is

reversed by ICB, which blocks interactions between the inhibitory

receptors of lymphocytes and their ligands (55). The PD-1/programmed death-ligand 1

(PD-L1) axis is the most studied of these interactions within TILs

(56,57).

Even though numerous patients achieve complete

clinical response to ICB therapy, a significant proportion of

patients show only a partial response or no response at all, which

is occasionally accompanied by signs of systemic toxicity (58). This situation explains why the

search for prognostic markers for ICB in patients with RCC is a

highly active area of research. Most prognostic markers for RCC can

be divided into those addressing disease progression and those

addressing responses to treatments, in particular immunotherapy and

directed therapies. Thus, predicting the ICB responsiveness will

impact in selecting the patients who will benefit the most and have

the lowest probability of developing adverse events after receiving

immunotherapy. There are currently no standardized and validated

methods for properly assessing the risk/benefit ratio of using ICB

therapy. Therefore, the goal of the present review was to

synthesize the reported findings of the studies that have focused

on this important topic.

ICB therapy is associated with an average mortality

rate of 1%, with death mostly caused by immune-related adverse

events (58). After the reporting

of successful results from the CheckMate-025 study, and given the

low predictability and consistency of ICB responsiveness (59), interest has been increasing in the

search for reliable markers of ICB responsiveness. Among the

biomarkers that have been studied, three stand out for their

consistency: the level of C-reactive protein (CRP), the number of

TILs and the basal expression levels of exhaustion markers in tumor

tissue. CRP is an acute phase reactant that is frequently used for

evaluating systemic inflammation, making it a logical putative

marker for ICB responsiveness given the close association between

inflammation and cancer. Previous studies have indicated that low

basal CRP levels or low normalized levels of CRP measured after

patients received their first ICB doses were predictive of their

ICB responsiveness (60–63). Studies investigating TILs found that

a patient's prognosis is associated with the nature of his or her

infiltrating cells; infiltration with inflammatory leukocytes was

associated with the best responses to ICB therapy (64–66).

In peripheral blood, a recent study observed that increased numbers

of circulating eosinophils were associated with an improved

response to ICB, which is an intriguing result given the regulatory

role that eosinophils play in systemic inflammation (67). Interestingly, the basal expression

level of PD-L1 has not been consistently predictive of ICB

responsiveness (68–70), whereas the basal expression level of

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3) appears

to be (71).

Several additional markers have been studied for

predicting the response to ICB in patients with RCC. For example,

longer responses to ICB have been associated with decreased levels

of circulating tumor DNA, increased levels of chemokine CXCL14,

increased levels of circulating miR-22 and miR-24, and the presence

of immunogenic transcriptional signatures (72–75).

In this context, several markers have been associated with poor

responses after ICB therapy (increased levels of interleukin-8) or

predictive of the development of immune-related adverse events

(decreased levels of miR-146a) (76,77).

All the studies described in this section are summarized in

Table V.

From a technical perspective, the evaluation of

leukocytes' exhaustion markers require the performance of

histopathology after the direct sampling of tissue, which is not

feasible for all diagnoses (78).

In this context, the studies assessing the suitability of

peripheral biomarkers for predicting ICB responsiveness are

encouraging (79,80).

Several limitations currently prevent the formal use

of markers to predict ICB responsiveness. First, the inconsistency

of reported outcomes is mostly related to heterogeneity in the

target population and the low number of patients that have been

studied. In addition, a lack of standardization in the use of

methods and reagents is complicating the replication of pioneering

studies. Furthermore, the relationship between the expression of

such potential biomarkers and the underlying mechanisms of

resistance to ICB is not fully understood, making it difficult not

only to predict ICB responsiveness but also to know the clinical

safety of using ICB. Finally, the intrinsic resistance of RCCs to

chemotherapy and the complex combinations required for treatment

make it difficult to determine a logical approach for studying the

expression of putative cancer biomarkers. In the future, by

integrating multi-omics data and machine-learning approaches, it

should be possible to create more accurate prediction models that

will help in the identification of novel biomarkers for ICB

responsiveness.

The authors are grateful to Dr. Susana Chávez

(Department for Research Assistance, University Hospital ‘José

Eleuterio González’, Autonomous University of Nuevo León) for

reviewing the English language in this manuscript.

The present study was supported by CONAHCYT México (grant no.

783446).

Not applicable.

RGG and MMT performed the literature review, wrote

the manuscript, made the illustrations and constructed the tables.

AGG, MCSC and MMT revised the manuscript. RGG and MMT were involved

in the conception of the study. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Padala SA and Barsouk A, Thandra KC,

Saginala K, Mohammed A, Vakiti A, Rawla P and Barsouk A:

Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. World J Oncol. 11:79–87.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Bukavina L, Bensalah K, Bray F, Carlo M,

Challacombe B, Karam JA, Kassouf W, Mitchell T, Montironi R and

O'Brien T: Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma: 2022 update. Eur

Urol. 82:529–542. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Musaddaq B, Musaddaq T, Gupta A, Ilyas S

and von Stempel C: Renal cell carcinoma: The evolving role of

imaging in the 21st century. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 41:344–350.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Scosyrev E, Messing EM, Sylvester R and

Van Poppel H: Exploratory subgroup analyses of renal function and

overall survival in european organization for research and

treatment of cancer randomized trial of Nephron-sparing surgery

versus radical nephrectomy. Eur Urol Focus. 3:599–605. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Goswami PR, Singh G, Patel T and Dave R:

The WHO 2022 classification of renal neoplasms (5th Edition):

Salient updates. Cureus. 16:e584702024.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Didwaniya N, Edmonds RJ, Fang X,

Silberstein PT and Subbiah S: Survival outcomes in metastatic renal

carcinoma based on histological subtypes: SEER database analysis. J

Clin Oncol. 29:381. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Morais C, Gobe G, Johnson DW and Healy H:

Inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B transcription activity drives

a synergistic effect of pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate and cisplatin

for treatment of renal cell carcinoma. Apoptosis. 15:412–425. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Toth C, Funke S, Nitsche V, Liverts A,

Zlachevska V, Gasis M, Wiek C, Hanenberg H, Mahotka C, Schirmacher

P and Heikaus S: The role of apoptosis repressor with a CARD domain

(ARC) in the therapeutic resistance of renal cell carcinoma (RCC):

The crucial role of ARC in the inhibition of extrinsic and

intrinsic apoptotic signalling. Cell Commun Signal. 15:162017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Yang WZ, Zhou H and Yan Y: XIAP underlies

apoptosis resistance of renal cell carcinoma cells. Mol Med Rep.

17:125–130. 2018.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Wang L, Fu B, Hou DY, Lv YL, Yang G, Li C,

Shen JC, Kong B, Zheng LB, Qiu Y, et al: PKM2 allosteric converter:

A self-assembly peptide for suppressing renal cell carcinoma and

sensitizing chemotherapy. Biomaterials. 296:1220602023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Diamond E, Molina AM, Carbonaro M, Akhtar

NH, Giannakakou P, Tagawa ST and Nanus DM: Cytotoxic chemotherapy

in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma in the era of

targeted therapy. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 96:518–526. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Saliby RM, Saad E, Kashima S, Schoenfeld

DA and Braun DA: Update on biomarkers in renal cell carcinoma. Am

Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 44:e4307342024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Lam JS, Pantuck AJ, Belldegrun AS and

Figlin RA: Protein expression profiles in renal cell carcinoma:

Staging, prognosis, and patient selection for clinical trials. Clin

Cancer Res. 13((2 Pt 2)): 703s–708s. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Lee JN, Chun SY, Ha YS, Choi KH, Yoon GS,

Kim HT, Kim TH, Yoo ES, Kim BW and Kwon TG: Target molecule

expression profiles in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Development

of individual targeted therapy. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 13:416–427.

2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Patard JJ, Leray E, Rioux-Leclercq N,

Cindolo L, Ficarra V, Zisman A, De La Taille A, Tostain J, Artibani

W, Abbou CC, et al: Prognostic value of histologic subtypes in

renal cell carcinoma: A multicenter experience. J Clin Oncol.

23:2763–2771. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Harshman LC,

Bjarnason GA, Vaishampayan UN, Mackenzie M, Wood L, Donskov F, Tan

MH, et al: External validation and comparison with other models of

the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database

Consortium prognostic model: A population-based study. Lancet

Oncol. 14:141–148. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Kattan MW, Reuter V, Motzer RJ, Katz J and

Russo P: A Postoperative prognostic nomogram for renal cell

carcinoma. J Urol. 166:63–67. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Motzer RJ, Escudier B, McDermott DF,

George S, Hammers HJ, Srinivas S, Tykodi SS, Sosman JA, Procopio G,

Plimack ER, et al: Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced

Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 373:1803–1813. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, Arén

Frontera O, Melichar B, Choueiri TK, Plimack ER, Barthélémy P,

Porta C, George S, et al: Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus

sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med.

378:1277–1290. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Motzer R, Alekseev B, Rha SY, Porta C, Eto

M, Powles T, Grünwald V, Hutson TE, Kopyltsov E, Méndez-Vidal MJ,

et al: Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus for advanced

renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 384:1289–1300. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Motzer RJ, Penkov K, Haanen J, Rini B,

Albiges L, Campbell MT, Venugopal B, Kollmannsberger C, Negrier S,

Uemura M, et al: Avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for

advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 380:1103–1115. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, Gafanov R,

Hawkins R, Nosov D, Pouliot F, Alekseev B, Soulières D, Melichar B,

et al: Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced

Renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 380:1116–1127. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Rini BI, Powles T, Atkins MB, Escudier B,

McDermott DF, Suarez C, Bracarda S, Stadler WM, Donskov F, Lee JL,

et al: Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sunitinib in patients

with previously untreated metastatic renal cell carcinoma

(IMmotion151): A multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised

controlled trial. The Lancet. 393:2404–2415. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Vogelzang NJ, Olsen MR, McFarlane JJ,

Arrowsmith E, Bauer TM, Jain RK, Somer B, Lam ET, Kochenderfer MD,

Molina A, et al: Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in patients with

advanced Non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Results from the

Phase IIIb/IV CheckMate 374 study. Clin Genitourin Cancer.

18:461–468.e3. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Tykodi SS, Gordan LN, Alter RS, Arrowsmith

E, Harrison MR, Percent I, Singal R, Van Veldhuizen P, George DJ,

Hutson T, et al: Safety and efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab

in patients with advanced non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma:

Results from the phase 3b/4 CheckMate 920 trial. J Immunother

Cancer. 10:e0038442022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Pal SK, Albiges L, Tomczak P, Suárez C,

Voss MH, de Velasco G, Chahoud J, Mochalova A, Procopio G,

Mahammedi H, et al: Atezolizumab plus cabozantinib versus

cabozantinib monotherapy for patients with renal cell carcinoma

after progression with previous immune checkpoint inhibitor

treatment (CONTACT-03): A multicentre, randomised, Open-label,

phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 402:185–195. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Choueiri TK, Powles T, Burotto M, Escudier

B, Bourlon MT, Zurawski B, Oyervides Juárez VM, Hsieh JJ, Basso U,

Shah AY, et al: Nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib for

advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 384:829–841. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Choueiri TK, Tomczak P, Park SH, Venugopal

B, Ferguson T, Chang YH, Hajek J, Symeonides SN, Lee JL, Sarwar N,

et al: Adjuvant pembrolizumab after nephrectomy in renal-cell

carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 385:683–694. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Monjaras-Avila CU, Lorenzo-Leal AC,

Luque-Badillo AC, D'Costa N, Chavez-Muñoz C and Bach H: The tumor

immune microenvironment in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Int J

Mol Sci. 24:79462023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Karras P, Black JRM, McGranahan N and

Marine JC: Decoding the interplay between genetic and Non-genetic

drivers of metastasis. Nature. 629:543–554. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Ucche S and Hayakawa Y: Immunological

aspects of cancer cell metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 25:52882024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Bucciol G, Delafontaine S, Meyts I and

Poli C: Inborn errors of immunity: A field without frontiers.

Immunol Rev. 322:15–27. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Kramer G, Blair T, Bambina S, Kaur AP,

Alice A, Baird J, Friedman D, Dowdell AK, Tomura M, Grassberger C,

et al: Fluorescence tracking demonstrates T cell recirculation is

transiently impaired by radiation therapy to the tumor. Sci Rep.

14:119092024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Tan D, Miao D, Zhao C, Shi J, Lv Q, Xiong

Z, Yang H and Zhang X: Comprehensive analyses of A

12-metabolism-associated gene signature and its connection with

tumor metastases in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer.

23:2642023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Wu Y and Li X: Senescence gene expression

in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Role of tumor immune

microenvironment and senescence-associated survival prediction.

Medicine (Baltimore). 102:e352222023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Zhang Q, Lin B, Chen H, Ye Y, Huang Y,

Chen Z and Li J: Lipid Metabolism-related gene expression in the

immune microenvironment predicts prognostic outcomes in renal cell

carcinoma. Front Immunol. 14:13242052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Bahadoram S, Davoodi M, Hassanzadeh S,

Bahadoram M, Barahman M and Mafakher L: Renal cell carcinoma: An

overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. G Ital

Nefrol. 39:2022–vol3. 2022.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Mickisch G, Bier H, Bergler W, Bak M,

Tschada R and Alken P: P-170 glycoprotein, glutathione and

associated enzymes in relation to chemoresistance of primary human

renal cell carcinomas. Urol Int. 45:170–176. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Guo Y, Schoell MC and Freeman RS: The von

Hippel-lindau protein sensitizes renal carcinoma cells to apoptotic

stimuli through stabilization of BIMEL. Oncogene. 28:18642009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Büscheck F, Fraune C, Simon R, Kluth M,

Hube-Magg C, Möller-Koop C, Sarper I, Ketterer K, Henke T,

Eichelberg C, et al: Prevalence and clinical significance of VHL

mutations and 3p25 deletions in renal tumor subtypes. Oncotarget.

11:237–249. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Ascierto ML, McMiller TL, Berger AE,

Danilova L, Anders RA, Netto GJ, Xu H, Pritchard TS, Fan J, Cheadle

C, et al: The intratumoral balance between metabolic and

immunologic gene expression is associated with Anti-PD-1 response

in patients with renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res.

4:726–733. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Rooney MS, Shukla SA, Wu CJ, Getz G and

Hacohen N: Molecular and genetic properties of tumors associated

with local immune cytolytic activity. Cell. 160:48–61. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Möller K, Fraune C, Blessin NC, Lennartz

M, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C, Lindhorst L, Dahlem R, Fisch M, Eichenauer

T, et al: Tumor cell PD-L1 expression is a strong predictor of

unfavorable prognosis in immune checkpoint Therapy-naive clear cell

renal cell cancer. Int Urol Nephrol. 53:2493–2503. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Kawashima A, Kanazawa T, Kidani Y, Yoshida

T, Hirata M, Nishida K, Nojima S, Yamamoto Y, Kato T, Hatano K, et

al: Tumour grade significantly correlates with total dysfunction of

tumour Tissue-infiltrating lymphocytes in renal cell carcinoma. Sci

Rep. 10:62202020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Wang Y, Yin C, Geng L and Cai W: Immune

infiltration landscape in clear cell renal cell carcinoma

implications. Front Oncol. 10:4916212021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Sabrina S, Takeda Y, Kato T, Naito S, Ito

H, Takai Y, Ushijima M, Narisawa T, Kanno H, Sakurai T, et al:

Initial myeloid cell status is associated with clinical outcomes of

renal cell carcinoma. Biomedicines. 11:12962023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Liu B, Chen X, Zhan Y, Wu B and Pan S:

Identification of a gene signature for renal cell

Carcinoma-associated fibroblasts mediating cancer progression and

affecting prognosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 8:6046272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Zhang Y, Chen X, Fu Q, Wang F, Zhou X,

Xiang J, He N, Hu Z and Jin X: Comprehensive analysis of pyroptosis

regulators and tumor immune microenvironment in clear cell renal

cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 21:6672021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Ballesteros PÁ, Chamorro J, Román-Gil MS,

Pozas J, Gómez Dos Santos V, Granados ÁR, Grande E, Alonso-Gordoa T

and Molina-Cerrillo J: Molecular mechanisms of resistance to

immunotherapy and antiangiogenic treatments in clear cell renal

cell carcinoma. Cancers. 13:59812021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Derosa L, Hellmann MD, Spaziano M,

Halpenny D, Fidelle M, Rizvi H, Long N, Plodkowski AJ, Arbour KC,

Chaft JE, et al: Negative association of antibiotics on clinical

activity of immune checkpoint inhibitors in patients with advanced

renal cell and Non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 29:1437–1444.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Routy B, Le Chatelier E, Derosa L, Duong

CPM, Alou MT, Daillère R, Fluckiger A, Messaoudene M, Rauber C,

Roberti MP, et al: Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based

immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 359:91–97. 2018.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Xing Y and Hogquist KA: T-cell tolerance:

Central and peripheral. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol.

4:a0069572012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Braun DA, Street K, Burke KP, Cookmeyer

DL, Denize T, Pedersen CB, Gohil SH, Schindler N, Pomerance L,

Hirsch L, et al: Progressive immune dysfunction with advancing

disease stage in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell. 39:632–648.e8.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

McKay RR, Bossé D, Xie W, Wankowicz SAM,

Flaifel A, Brandao R, Lalani AA, Martini DJ, Wei XX, Braun DA, et

al: The clinical activity of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors in metastatic

non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 6:758–765.

2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Pichler R, Siska PJ, Tymoszuk P, Martowicz

A, Untergasser G, Mayr R, Weber F, Seeber A, Kocher F, Barth DA, et

al: A chemokine network of T cell exhaustion and metabolic

reprogramming in renal cell carcinoma. Front Immunol.

14:10951952023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Wang DY, Salem JE, Cohen JV, Chandra S,

Menzer C, Ye F, Zhao S, Das S, Beckermann KE, Ha L, et al: Fatal

toxic effects associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. JAMA

Oncol. 4:1721–1728. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Lin E, Liu X, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Xie L, Tian

K, Liu J and Yu Y: Roles of the dynamic tumor immune

microenvironment in the individualized treatment of advanced clear

cell renal cell carcinoma. Front Immunol. 12:6533582021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Ishihara H, Takagi T, Kondo T, Fukuda H,

Tachibana H, Yoshida K, Iizuka J, Okumi M, Ishida H and Tanabe K:

Predictive impact of an early change in serum C-reactive protein

levels in nivolumab therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma.

Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 38:526–532. 2020.

|

|

61

|

Noguchi G, Nakaigawa N, Umemoto S,

Kobayashi K, Shibata Y, Tsutsumi S, Yasui M, Ohtake S, Suzuki T,

Osaka K, et al: C-reactive protein at 1 month after treatment of

nivolumab as a predictive marker of efficacy in advanced renal cell

carcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 86:75–85. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Yano Y, Ohno T, Komura K, Fukuokaya W,

Uchimoto T, Adachi T, Hirasawa Y, Hashimoto T, Yoshizawa A,

Yamazaki S, et al: Serum C-reactive protein level predicts overall

survival for clear cell and Non-clear cell renal cell carcinoma

treated with ipilimumab plus nivolumab. Cancers. 14:56592022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Tomita Y, Larkin J, Venugopal B, Haanen J,

Kanayama H, Eto M, Grimm MO, Fujii Y, Umeyama Y, Huang B, et al:

Association of C-reactive protein with efficacy of avelumab plus

axitinib in advanced renal cell carcinoma: Long-term follow-up

results from JAVELIN renal 101. ESMO Open. 7:1005642022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Kim JH, Kim GH, Ryu YM, Kim SY, Kim HD,

Yoon SK, Cho YM and Lee JL: Clinical implications of the tumor

microenvironment using multiplexed immunohistochemistry in patients

with advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with

nivolumab plus ipilimumab. Front Oncol. 12:9695692022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Sammarco E, Rossetti M, Salfi A, Bonato A,

Viacava P, Masi G, Galli L and Faviana P: Tumor microenvironment

and clinical efficacy of first line Immunotherapy-based

combinations in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Med Oncol.

41:1502024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Kazama A, Bilim V, Tasaki M, Anraku T,

Kuroki H, Shirono Y, Murata M, Hiruma K and Tomita Y:

Tumor-infiltrating immune cell status predicts successful response

to immune checkpoint inhibitors in renal cell carcinoma. Sci Rep.

12:203862022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Herrmann T, Ginzac A, Molnar I, Bailly S,

Durando X and Mahammedi H: Eosinophil counts as a relevant

prognostic marker for response to nivolumab in the management of

renal cell carcinoma: A retrospective study. Cancer Med.

10:6705–6713. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

68

|

Atkins MB, Jegede OA, Haas NB, McDermott

DF, Bilen MA, Stein M, Sosman JA, Alter R, Plimack ER, Ornstein M,

et al: Phase II study of nivolumab and salvage Nivolumab/Ipilimumab

in Treatment-naive patients with advanced clear cell renal cell

carcinoma (HCRN GU16-260-Cohort A). J Clin Oncol. 40:2913–2923.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Motzer RJ, Choueiri TK, McDermott DF,

Powles T, Vano YA, Gupta S, Yao J, Han C, Ammar R,

Papillon-Cavanagh S, et al: Biomarker analysis from CheckMate 214:

Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma.

J Immunother Cancer. 10:e0043162022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Brown LC, Zhu J, Desai K, Kinsey E, Kao C,

Lee YH, Pabla S, Labriola MK, Tran J, Dragnev KH, et al: Evaluation

of tumor microenvironment and biomarkers of immune checkpoint

inhibitor response in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Immunother

Cancer. 10:e0052492022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Kato R, Jinnouchi N, Tuyukubo T, Ikarashi

D, Matsuura T, Maekawa S, Kato Y, Kanehira M, Takata R, Ishida K

and Obara W: TIM3 expression on tumor cells predicts response to

anti-PD-1 therapy for renal cancer. Transl Oncol. 14:1009182020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Koh Y, Nakano K, Katayama K, Yamamichi G,

Yumiba S, Tomiyama E, Matsushita M, Hayashi Y, Yamamoto Y, Kato T,

et al: Early dynamics of circulating tumor DNA predict clinical

response to immune checkpoint inhibitors in metastatic renal cell

carcinoma. Int J Urol. 29:462–469. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Incorvaia L, Fanale D, Badalamenti G,

Brando C, Bono M, De Luca I, Algeri L, Bonasera A, Corsini LR,

Scurria S, et al: A ‘Lymphocyte MicroRNA Signature’ as predictive

biomarker of immunotherapy response and plasma PD-1/PD-L1

expression levels in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma:

Pointing towards epigenetic reprogramming. Cancers. 12:33962020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

74

|

Pan Q, Liu R, Zhang X, Cai L, Li Y, Dong

P, Gao J, Liu Y and He L: CXCL14 as a potential marker for

immunotherapy response prediction in renal cell carcinoma. Ther Adv

Med Oncol. 15:175883592312179662023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Pabla S, Seager RJ, Van Roey E, Gao S,

Hoefer C, Nesline MK, DePietro P, Burgher B, Andreas J, Giamo V, et

al: Integration of tumor inflammation, cell proliferation, and

traditional biomarkers improves prediction of immunotherapy

resistance and response. Biomark Res. 9:562021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Schalper KA, Carleton M, Zhou M, Chen T,

Feng Y, Huang SP, Walsh AM, Baxi V, Pandya D, Baradet T, et al:

Elevated serum interleukin-8 is associated with enhanced intratumor

neutrophils and reduced clinical benefit of immune-checkpoint

inhibitors. Nat Med. 26:688–692. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Ivanova E, Asadullina D, Rakhimov R,

Izmailov A, Izmailov A, Gilyazova G, Galimov S, Pavlov V,

Khusnutdinova E and Gilyazova I: Exosomal miRNA-146a is

downregulated in clear cell renal cell carcinoma patients with

severe immune-related adverse events. Noncoding RNA Res. 7:159–163.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Petitprez F, Ayadi M, de Reyniès A,

Fridman WH, Sautès-Fridman C and Job S: Review of prognostic

expression markers for clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Front

Oncol. 11:6430652021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

Lee A, Lee HJ, Huang HH, Tay KJ, Lee LS,

Sim SPA, Ho SSH, Yuen SPJ and Chen K: Prognostic significance of

inflammation-associated blood cell markers in nonmetastatic clear

cell renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 18:304–313.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Teishima J, Inoue S, Hayashi T and

Matsubara A: Current status of prognostic factors in patients with

metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int J Urol. 26:608–617. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|