Introduction

The incidence of prostate cancer (PCa) is increasing

yearly, and in 2022, PCa was the second most common cancer in men,

with >1 million new cases and >390,000 deaths worldwide

(1). Localized PCa can be treated

by surgery or radiotherapy and has a good prognosis. Although the

treatment of metastatic PCa is improving, the 5-year survival rate

of metastatic PCa is only 32% (2).

PCa is an androgen-dependent tumor and androgens can strongly

promote PCa cell proliferation and metastasis. Thus, androgen

deprivation therapy (ADT) is a modality that has been used to treat

PCa for decades and has become one of the most effective treatment

options for patients with metastatic hormone-sensitive PCa (mHSPC)

(3). Recently, a number of studies

have shown that ADT combined with docetaxel or androgen receptor

pathway inhibitors (ARPIs) can improve the overall survival (OS) of

patients with mHSPC (4–8), and this new treatment regimen has

become the standard treatment for this disease (9). Unfortunately, despite the advances in

therapeutic drugs, HSPC can gradually lose sensitivity to treatment

and eventually develop into metastatic castration-resistant PCa

(mCRPC) (10). First-line treatment

of mCRPC includes ARPIs, docetaxel, sipuleucel-T, Ipatasertib and

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors combined with an ARPI

(11). All patients with mCRPC who

receive first-line treatment will eventually experience disease

progression (11).

Subsequent treatment options for mCRPC include

several novel agents. For instance, antibody-drug conjugates

(ADCs), consisting of monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and potent

cytotoxic payloads conjugated by chemical linkers, are a

therapeutic option that has been rapidly developing in recent years

(12). The basic principle of ADCs

is the specific combination of antigens and antibodies. Antitumor

drugs can specifically bind to antigens on the surface of cancer

cells and eliminate these cells through antibody delivery, which

reduces the toxicity of antitumor drugs (13). The enhanced antitumor efficacy of

ADCs leads to an improved quality of life of the patient and

reduced toxicity compared with conventional chemotherapies

(14). Additionally, ADCs targeting

the same molecular pathway may retain efficacy in patients who have

developed resistance to specific targeted therapies, thereby

expanding their potential indications for antitumor treatment

(15). Human epidermal growth

factor receptor 2 (HER2) serves as a crucial therapeutic target for

advanced breast cancer, and in cases where patients with metastatic

breast cancer develop resistance to anti-HER2 targeted agents,

anti-HER2 ADCs can still effectively exert antitumor activity

(16). Notably, the anti-HER2 ADC

trastuzumab deruxtecan has demonstrated efficacy even in patients

with advanced breast cancer and low HER2 expression (17). ADCs are also effective in targeting

novel therapeutic targets. For instance, sacituzumab govitecan

(SG), which specifically targets trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2

(TROP-2), offers additional treatment alternatives for advanced

triple-negative breast cancer management (18).

At present, patients with advanced PCa, such as

mCRPC, have few treatment options and the emergence of ADCs brings

new alternatives for these patients. Although ADCs were developed

decades ago for treating patients with advanced solid tumors, their

use in PCa treatment is still in the clinical drug development

stages. Therefore, how to further utilize ADCs in the field of PCa

treatment is the current clinical challenge, including reducing

adverse events (AEs) and improving effectiveness. In the treatment

of PCa, several therapeutic targets of ADCs have been developed,

including prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), STEAP family

member 1 (STEAP1), TROP-2, CD46, B7-H3, tissue factor (TF) and

delta-like protein 3 (DLL3).

In the present review, first, the developmental

course, structural composition and mechanism of action of ADCs is

illustrated. Second, the clinical outcomes of ADCs in the field of

PCa treatment as well as the ongoing clinical trials are

systematically described. Finally, the ongoing challenges in ADC

development and the corresponding strategies to overwhelm them are

discussed.

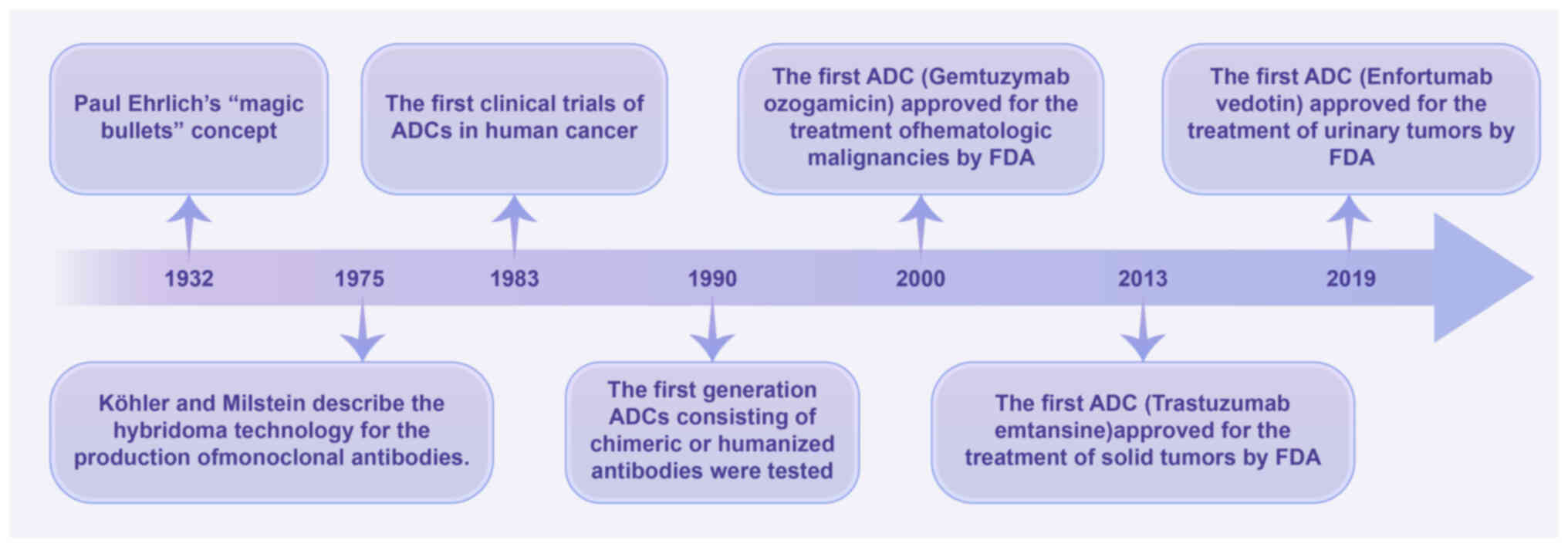

Development of ADCs

ADCs originate from the idea by Paul Ehrlich in 1913

that ‘antibodies are in a way magic bullets that identify their

target themselves without harming the organism’ (19). In 1975, Köhler and Milstein

(20) developed hybridoma

technology and successfully produced mAbs, which was an important

step in turning this ‘idea’ into a treatment reality. In 1983, ADCs

were first used in clinical trials; however, clinical efficacy was

not successful due to the inclusion of murine mAbs (19). This prompted researchers to further

develop ADCs containing humanized or chimeric antibodies that can

eliminate cancer cells through multiple mechanisms, such as

antibody-dependent cytotoxicity, interference with signaling,

complement-dependent cytotoxicity and immune regulation (21,22).

In 1990, novel ADCs containing chimeric or humanized antibodies

were tested in clinical trials. Ultimately, ADCs passed clinical

trials and were approved by the United States Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) in 2000. The first ADC approved for use in

hematological malignancies was gemtuzumab ozogamicin, which was

approved by the FDA on May 17, 2000, for the treatment of

CD33+ acute myelogenous leukemia (23). Furthermore, the FDA granted approval

to trastuzumab emtansine on February 22, 2013, marking the first

authorization of an ADC for the treatment of solid tumors in

patients with HER2+ advanced breast cancer (24,25).

On December 18, 2019, enfortumab vedotin was approved by the FDA

for the treatment of metastatic urothelial carcinoma, which was the

first ADC approved for the treatment of urological malignancies

(Fig. 1) (26). At present, >10 ADCs have been

approved by the FDA and ~200 ADCs are being evaluated in clinical

trials. ADCs have changed the treatment strategy of numerous

malignant tumors and have expanded the treatment options for

patients with advanced tumors; however, to the best of our

knowledge, there are still no approved ADCs for PCa.

Components and mechanism of action of

ADCs

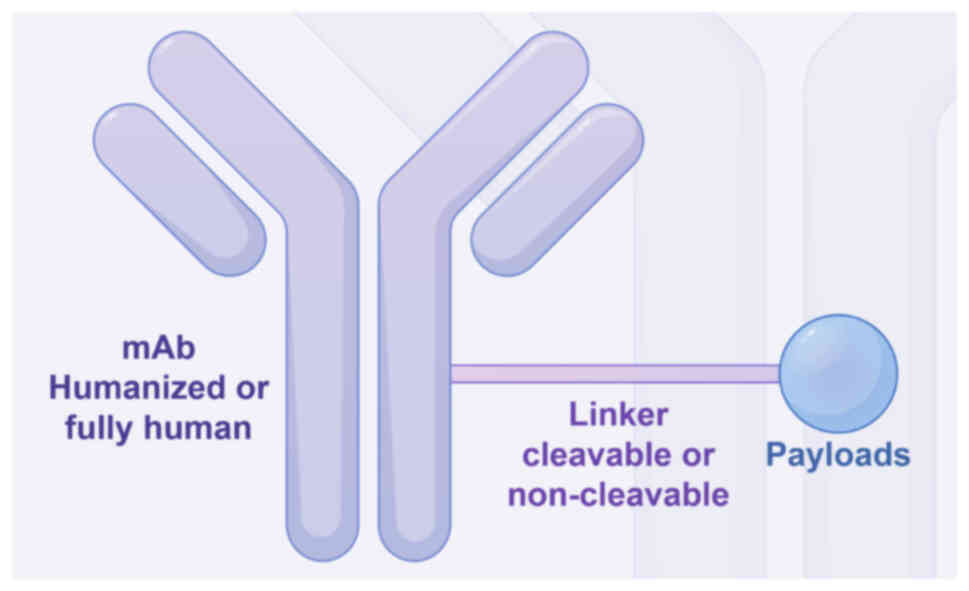

ADCs are developed based on enhanced antibody

technology and comprise three essential components: A mAb that

specifically targets tumor surface antigens, a potent cytotoxic

payload engineered to induce damage to DNA or tubulin within the

targeted cancer cells and a linker that firmly attaches the

antibody to the payload (Fig. 2)

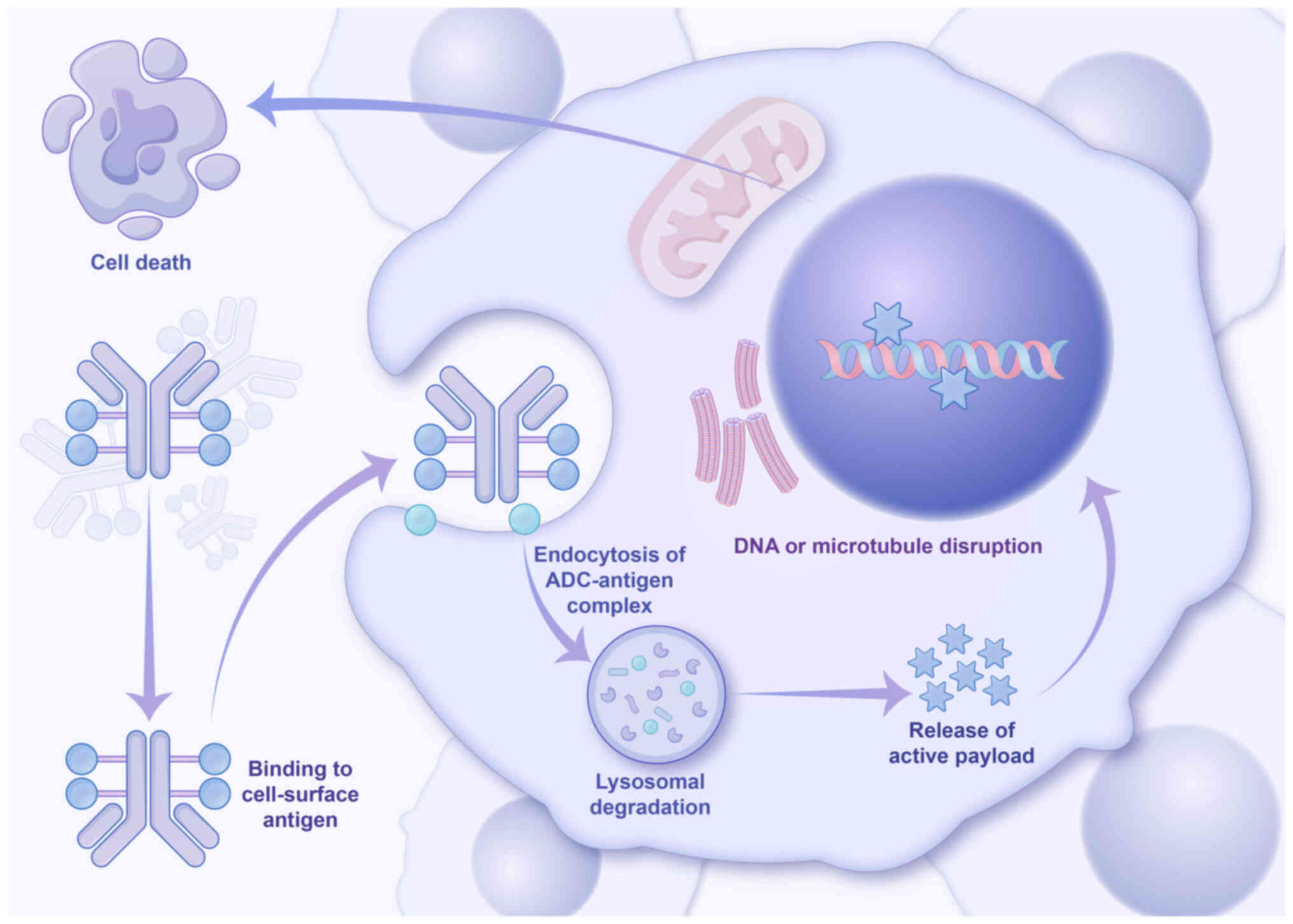

(27). The general mechanism of

action of ADCs is shown in Fig. 3.

Briefly, once introduced into the bloodstream, ADCs specifically

recognize and bind to antigens that are upregulated on the surface

of cancer cells. Subsequently, these bound ADCs undergo rapid

internalization into the cells, where they are then processed by

intracellular lysosomes for the release of the cytotoxic payloads

(28). After being released from

the antibody within the cell, a portion of the hydrophobic payload

has the ability to diffuse beyond the target cell and effectively

eliminate surrounding antigen-negative cancer cells or

non-malignant cells. This phenomenon, referred to as the bystander

killing effect, has been extensively studied, and research

indicates that this effect can significantly augment the antitumor

activity of ADCs (29–31).

The antibody component of ADCs, which serves a

crucial role in specifically binding to target cell surface

antigens, has undergone significant advancements and refinements in

recent decades (28). The targets

of ADCs (cell surface antigens) should ideally be upregulated on

cancer cells while maintaining low expression on normal cells. This

specificity enables the specific binding of ADCs and the subsequent

release of toxic payloads, thereby minimizing the cytotoxic effects

on normal cells (32). The

identification of two distinct types of tumor surface antigens,

namely tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and tumor-specific antigens

(TSAs), has been accomplished (33). TAAs are upregulated in cancer cells

and downregulated in normal cells, whereas TSAs are exclusively

expressed on the surface of cancer cells rather than normal cells.

Consequently, TSAs can serve as markers for discriminating between

tumor and normal cells (34). The

use of a TSA as the target of an ADC will greatly improve the

effectiveness of the ADC and reduce the toxicity to normal cells.

However, most of the ADC targets in current clinical trials are

TAAs (35).

The linker, a crucial component of ADCs, has a

pivotal role in determining the toxicity and efficacy of ADCs. Once

introduced into the bloodstream, it is imperative for the linker to

maintain stability throughout circulation to prevent premature

detachment of toxic payloads from the ADCs (36). The two primary types of linkers in

current use are cleavable and non-cleavable linkers. At present,

the majority of ADCs employ cleavable linkers that incorporate

chemical triggers capable of efficient cleavage, leading to the

release of cytotoxic payloads (37). These linkers are designed to be

cleaved after internalization into cancer cells, ensuring optimal

efficacy by releasing toxic loads at the desired site. However,

premature cleavage of these cleavable linkers in circulation

results in the early release of effective payloads, thereby

increasing blood toxicity and diminishing the effectiveness of ADCs

(38). Non-cleavable linkers

consist of stable bonds and are resistant to protease degradation.

These linkers are an integral part of the payload, and the release

of the cytotoxic payload occurs only after complete internalization

of ADCs into the cell. This mechanism enhances the efficacy while

reducing the toxicity of ADCs (37). At present, research is focused on

the development of novel linkers with improved stability,

solubility and release characteristics.

The cytotoxic payload is the primary component

responsible for the eradication of cancer cells by ADCs, which is

released subsequent to ADC internalization into the cellular milieu

(39). The in vitro toxicity

levels of commonly used chemotherapies are in the micromolar range,

whereas the payloads utilized for ADCs exhibit sub-nanomolar or

even picomolar levels of cytotoxicity in vitro (40). The current repertoire of cytotoxic

payloads utilized for ADCs primarily encompass potent tubulin

inhibitors, DNA damage agents and recently developed

immunomodulators (41). Tubulin

inhibitors function by disrupting microtubule-dependent mitosis.

Prominent tubulin inhibitors include monomethyl auristatin (MMA)E,

MMAF and their maytansine derivatives, DM1 and DM4 (42). The half-maximal inhibitory

concentration (IC50) values of microtubule inhibitors

typically fall within the nanomolar range, whereas DNA damaging

agents can exhibit IC50 values as low as picomolar

(43). Therefore, ADCs are

occasionally more effective when conjugated to DNA damaging agents,

even when targeting cells with low surface antigen expression

(43). The currently utilized DNA

damaging agents include calicheamicins and pyrrolobenzodiazepine

dimers (PBDs), as well as topoisomerase I inhibitors such as SN-38

and the exatecan derivative (DXd). The field of ADCs is witnessing

a surge in the development of novel payloads, with small molecule

immunomodulators, also known as immunostimulatory antibody

conjugates, emerging as a promising class of cytotoxic agents

(44). This innovative payload

holds great potential in enhancing the efficacy of ADCs and

extending patient survival.

ADCs in PCa

PSMA

PSMA is a transmembrane protein consisting of 750

amino acids that is located on the surface of prostate epithelial

cells (45). The expression of PSMA

is typically low in normal prostate tissue, but it undergoes a

notable increase of >1,000-fold in PCa. Moreover, the

upregulation of PSMA expression is positively correlated with a

higher tumor grade, castration resistance and tumor metastasis

(46). Therefore, PSMA has emerged

as a commonly employed target for the diagnosis and treatment of

PCa. At present, four PSMA-targeting ADCs, namely MLN2704, PSMA

ADC, MEDI3726 and ARX517, have been developed for clinical

trials.

MLN591 is a deimmunized anti-PSMAext mAb,

which exhibits rapid internalization and high affinity for the

external domain of PSMA, and MLN2704 is an ADC consisting of MLN591

linked to DM1, a potent chemotherapeutic drug that acts against

microtubules (47). MLN2704

exhibits rapid internalization upon binding to PSMA, resulting in

the intracellular release of DM1 and the subsequent eradication of

PCa cells. MLN2704 has shown dose-and schedule-dependent antitumor

activity in a PCa xenograft model (48). The initial human trial of MLN2704,

aimed at assessing the safety profile of doses ranging 18–343

mg/m2 administered every 4 weeks, encompassed a cohort

of 23 patients with mCRPC. Among this cohort, 3 individuals

experienced grade 3 drug-related AEs, and while no grade 4

toxicities were observed, 8 patients reported neuropathy. Notably,

a prostate-specific antigen (PSA)50 response was

detected in ~22% of the participants. These findings unequivocally

established the favorable safety profile of MLN2704 (Table I) (49). The PSA50 response is

defined as a ≥50% decrease from the initial level of serum PSA,

which is confirmed by a measurement taken at least 4 weeks after

treatment. In a subsequent phase I/II trial including 62 patients

with mCRPC, only 8% (5 out of 62) of patients demonstrated a

PSA50 response, while an equal proportion of patients

(8%) exhibited PSA stability lasting for ≥90 days. However, the

majority of patients (71%) experienced peripheral neuropathy and a

small percentage (10%) encountered grade 3/4 AEs (47). Due to the limited clinical efficacy

of MLN2704 and its narrow therapeutic range, further clinical

studies were not conducted.

| Table I.The clinical trial data of ADCs in

PCa. |

Table I.

The clinical trial data of ADCs in

PCa.

| First author/s,

year | Drug | Target | Conditions | Treatment | Phase | Trial number | Efficacy | Safety | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Ma et al,

2006 | MLN2704 | PSMA | mCRPC | Single agent | 1 | NCT00052000 | 22%

PSA50 response. | 13% Study

drug-related G 3 toxicities | (50) |

| Milowsky et

al, 2016 | MLN2704 | PSMA | mCRPC | Single agent | 1/2 | NCT00070837 | 8% PSA50

response; 8% PSA stabilization ≥90 days. | 71% exhibited

peripheral neuropathy: 10% had G 3/4. | (47) |

| Petrylak et

al, 2020 | PSMA ADC | PSMA | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI or docetaxel | Single agent | 1 | NCT01414283 | 15%

PSA50 response. | Most common

toxicities: fatigue (40%), neutropenia (33%). | (52) |

| Cho et al,

2018 | PSMA ADC | PSMA | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI or docetaxel | Single agent | 2 | NCT01695044 | 14%

PSA50 response; 78% CTC declined ≥50%. | Most common G ≥3

TRAEs: neutropenia, fatigue; most common serious AEs: dehydration,

hyponatremia. | (53) |

| Shen et al,

2023 | MEDI3726 | PSMA | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI or docetaxel | Single agent | 1 | NCT02991911 | 6.1%

PSA50 response. | 45%G3/4TRAEs. | (55) |

| Doronina et

al, 2003 | DSTP3086S | STEAP family member

1 | mCRPC | Single agent | 1 | NCT01283373 | 17.7%

PSA50 response. | Most common Gr ≥3

TRAEs: hyperglycaemia; hyperglycaemia and hypophosphataemia were

dose limiting. | (59) |

| Zang and Allison,

2022 | FOR46 | CD46 | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI | Single agent | 1a/1b | NCT03575819 | 45.5%

PSA50 response. | Most common Gr ≥3

TRAEs: neutropenia (77%) | (68) |

| Shenderov et

al, 2021 | MGC018 | B7-H3 | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI or docetaxel | Single agent | 1 | NCT03729596 | 55.5%

PSA50 response. | At least 1

treatment emergent AEs in 87% with commonest being

neutropenia. | (73) |

| Corti et al,

2023 | Tisotumab

vedotin | Tissue factor | Advanced solid

tumours including mCRPC | Single agent | 1/2 | NCT02001623 | None | Most common Gr ≥ 3

AEs: fatigue | (80) |

| Fuentes-Antras

et al, 2023 | Rovalpituzumab

tesirine | Delta-like protein

3 | Neuroendocrine

including carcinomas neuroendocrine PCa | Single agent | 1/2 | NCT02709889 | 76% clinical

benefit rate | Most common G3/4

AEs: anemia,. thrombocytopenia | (86) |

The PSMA ADC is prepared by conjugating a fully

human anti-PSMA mAb with MMAE through a valine-citrulline linker

(50). The PSMA ADC undergoes rapid

internalization upon binding to PSMA, leading to the release of

MMAE within the cell and the subsequent induction of cell cycle

arrest and apoptosis (50). The

initial 2019 phase I clinical trial of PSMA ADC involved dose

escalation and included patients with mCRPC who had previously

undergone taxane-based chemotherapy (51). The aforementioned study aimed to

determine the maximum tolerated dose of PSMA ADC and evaluate its

safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics (51). The PSMA ADC exhibited encouraging

antitumor efficacy and tolerable toxicity in this phase I trial.

The findings prompted a subsequent phase II trial involving 119

patients with mCRPC, wherein 14% achieved a PSA50

response, >75% experienced at least a 50% reduction in

circulating tumor cell (CTC) counts and 65% transitioned from an

unfavorable to a favorable CTC status (52). The most frequently observed

treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) of grade ≥3 in this study included

neutropenia, fatigue, electrolyte imbalance, anemia and neuropathy

(52). Serious AEs (SAEs)

encompassed dehydration, hyponatremia, febrile neutropenia and

constipation. Among the subjects who received a dosage of 2.5

mg/kg, 2 succumbed to sepsis.

The ADC, MEDI3726, is composed of an anti-PSMA

antibody conjugated with PBDs (53). MEDI3726 binds to the highly

expressed PSMA on PCa cells and is rapidly internalized, followed

by intracellular cathepsin cleavage, mediating the PBD payload

release. In a phase I trial involving 33 patients with mCRPC who

had experienced disease progression after prior treatment with

abiraterone, enzalutamide or taxane-based chemotherapy, the rate of

PSA50 response or a conversion in CTC count was found to

be 6.1% after treatment, while the rate of composite response was

12.1% (54). TRAEs were observed in

30 patients (90.9%), predominantly presenting as skin toxicities

and effusions, with grade 3/4 TRAEs occurring in 15 patients

(45.5%) and SAE-related discontinuation reported in 11 patients

(33.3%). Therefore, due to the lack of safety and efficacy,

MEDI3726 was not tested in a phase II trial.

The recruitment of patients with mCRPC commenced in

2021 for a phase I clinical trial aimed at evaluating the safety

profile of ARX517, an ADC comprising a human mAb targeting PSMA

that is covalently linked to the microtubule-disrupting toxin,

amberstatin-269. The study enrolled 24 patients with mCRPC who had

received at least one ARPI treatment line by October 2023. The

results demonstrated a PSA50 response in 8 patients and

a significant decline in CTCs in 12 patients. No SAEs were

reported, except for four grade 3 AEs, including thrombocytopenia

and lymphopenia (55). An ongoing

clinical trial (NCT04662580) aims to further verify the safety and

efficacy of ARX517 (Table II).

| Table II.The ongoing clinical trial data of

antibody-drug conjugates in prostate cancer. |

Table II.

The ongoing clinical trial data of

antibody-drug conjugates in prostate cancer.

| Drug | Target | Conditions | Treatment | Phase | Trial number | Estimated

Completion Date |

|---|

| ARX517 | Prostate-specific

membrane antigen | mCRPC | Single agent | 1 | NCT04662580 | March 2027 |

| Datopotamab | TROP-2 |

Advanced/Metastatic | Single agent

or | 2 | NCT05489211 | August 2026 |

| Deruxtecan |

| solid tumours | with Saruparib |

|

|

|

| (Dato-DXd) |

| including

mCRPC |

|

|

|

|

| Sacituzumab

govitecan (SG) | TROP-2 | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI | Single agent | 2 | NCT03725761 | April 2025 |

| FOR46 | CD46 | mCRPC progressing

on abiraterone | Combination with

enzalutamide | 1b/2 | NCT05011188 | March 2027 |

| MGC018 | B7-H3 | mCRPC progressing

on ARSI or docetaxel | Single agent | 2 | NCT05551117 | May 2027 |

| MGC018 | B7-H3 | Advanced/Metastatic

solid tumours including mCRPC | Combination with

lorigerlimab (MGD019) | 1 | NCT05293496 | March 2026 |

| Ifinatamab

deruxtecan (I-DXd) | B7-H3 | Advanced solid

tumours including mCRPC | Single agent | 1/2 | NCT04145622 | March 2027 |

| XB002 | Tissue factor | Advanced solid

tumours including mCRPC | Single agent or

with nivolumab | 1 | NCT04925284 | October 2024 |

STEAP1

The STEAP1 protein, also known as prostate

six-transmembrane epithelial antigen 1, is recognized for its role

as an ion channel or multi-transmembrane transporter (56). The expression levels of STEAP1 are

5-10-fold higher in human PCa cells compared with other cancer cell

types, thus positioning STEAP1 as a promising therapeutic target

for PCa (57). The DSTP3086S ADC is

designed to target STEAP1, consisting of the anti-STEAP1 mAb,

MSTP2109A, conjugated to MMAE via a cleavable linker (58). The DSTP3086S molecule specifically

binds to the surface of PCa cells, targeting STEAP1, and undergoes

rapid internalization. This leads to the intracellular release of

MMAE, which effectively inhibits the mitotic process in cancer

cells and ultimately induces cell death (59). In a phase I dose-escalation trial of

DSTP3086S, 77 patients with mCRPC and high STEAP1 expression were

enrolled. The dose range administered was escalated from 0.3–2.8

mg/kg every 3 weeks. Among these patients, doses >2 mg/kg were

well tolerated by 62 individuals, and while grade ≥3 AEs occurred

in 26 patients, a PSA50 response was observed in 11 patients

(17.7%) (58). The safety and

efficacy of DSTP3086S need to be further evaluated through phase II

trials.

TROP-2

TROP-2 is a glycoprotein expressed on the surface of

prostate cells, with upregulation observed in PCa cells (60). The majority of patients with mCRPC

treated with androgen receptor signaling inhibitors (ARSIs) who

progressed have been reported to exhibit upregulation of TROP-2

(61). The emergence of this

phenomenon has therefore prompted researchers to develop ADCs that

specifically target TROP-2 for the treatment of mCRPC. SG, an ADC

designed to target TROP-2, consists of a humanized RS7 mAb coupled

with SN-38 via a moderately stable carbonate bond (62). An ongoing open-label phase II trial

(NCT03725761) is currently enrolling patients with mCRPC who have

experienced disease progression following treatment with ARSIs. At

the time of the interim analysis, 20 patients had been enrolled,

demonstrating a 6-month radiographic progression-free survival rate

(PFS) of 45%. Among the observed AEs, neutropenia was the most

frequently reported (63).

The compound, Datopotamab Dxd (Dato-DXd), is an ADC

that specifically targets TROP-2 and is a humanized mAb linked to a

topoisomerase 1 inhibitor (64).

The safety and efficacy of Dato-DXd in patients with advanced solid

tumors, including mCRPC, are currently being investigated through

an ongoing phase II clinical trial (NCT05489211).

CD46

The membrane protein, CD46, is widely expressed in

human cell membranes, with the exception of red blood cells. CD46

has a crucial role in regulating the deposition of C3b/C4b on

various cell populations and serves as a target for numerous

pathogens (65). CD46 is

upregulated in mCRPC cells, and its expression is significantly

elevated in patients with mCRPC undergoing abiraterone and

enzalutamide treatment. Genomic analysis revealed that 45% of

patients with abiraterone-resistant mCRPC had acquired the CD46

gene (66). The ADC, FOR46,

consists of a mAb that specifically targets CD46 and is conjugated

with MMAE. In a phase Ia/Ib dose-escalation trial involving 33

patients with mCRPC who had experienced disease progression while

receiving ARPI, neutropenia emerged as the sole significant grade 3

AE, with 45.2% of the evaluable patients (14 out of 31) achieving a

PSA50 response (67). The efficacy

of FOR46 in patients with mCRPC necessitates further investigation,

and patient recruitment is currently underway for a phase Ib/II

trial evaluating the combination of FOR46 with enzalutamide in

patients with mCRPC who have experienced disease progression

following prior abiraterone therapy (NCT05011188).

B7-H3

B7-H3, an immunomodulatory protein, is also known as

CD276 (68). Studies have

demonstrated a correlation between the expression of B7-H3 on the

surface of PCa cells and an unfavorable prognosis following

surgical intervention, including early postoperative PSA recurrence

as well as the development of CRPC (69,70).

Moreover, the majority of patients with CRPC exhibit significant

upregulation of B7-H3 expression (93%) (71). The humanized ADC, MGC018,

specifically targets and eliminates cancer cells that upregulate

B7-H3. MGC018 exhibits favorable pharmacokinetic properties and has

demonstrated safety in preclinical tumor models (72). The recruitment of patients is

currently ongoing in a phase I trial evaluating the efficacy and

safety of MGC108 in mCRPC. As of May 3, 2021, 26 patients with

mCRPC had been enrolled, of which 11/22 evaluable patients showed a

PSA50 response, while the most frequently reported AEs included

neutropenia, fatigue, weakness and headache (73). At present, two clinical trials of

MGC018 in solid tumors, including mCRPC, are recruiting patients

(NCT05551117 and NCT05293496).

Ifinatamab Dxd (I-Dxd) is an additional ADC that

targets B7-H3. I-Dxd consists of a mAb that specifically binds to

B7-H3, which is linked to the topoisomerase I inhibitor, Dxd, via a

cleavable tetrapeptide linker (74). Enrollment is currently ongoing in a

phase I/II clinical trial (NCT04145622) aimed at investigating the

safety and efficacy of I-Dxd in patients diagnosed with advanced

solid tumors, including mCRPC.

TF

TF is alternatively referred to as thromboplastin,

factor III or CD142 (75). TF is a

transmembrane glycoprotein and, under physiological conditions, TF

activation marks the start of the exogenous coagulation pathway

(76). TF binds to its

physiological ligand, FVIIa, triggering the activation of

protease-activated receptor 2 and initiating an intracellular

signaling cascade that can be exploited by tumors to facilitate

tumor angiogenesis, enhance cancer cell survival and growth as well

as facilitate metastasis (77). The

expression of TF is upregulated in numerous solid malignancies,

including pancreatic, lung, breast, bladder and PCa (75). Tisolumab vedotin, an ADC composed of

a fully human mAb specific to TF conjugated with MMAE, has been

developed to target tumors that express TF (78). The InnovaTV 201 trial was a phase

I/II open-label study that involved dose-escalation and

dose-expansion in 147 patients with advanced solid tumors,

including PCa. During the dose-expansion phase, fatigue emerged as

the most frequently reported grade ≥3 AE (79). Among the patients with PCa included

in the study, none exhibited radiographic changes or a PSA response

(79). It is necessary to continue

evaluating the antitumor activity of TF in the context of PCa.

XB002 is an additional ADC that specifically targets

TF, consisting of a mAb directed against TF coupled with the

tubulin inhibitor, MMAE, via a cleavable linker (80). The ongoing clinical trial is a phase

I, open-label, multicenter study involving dose-escalation and

expansion of XB002 or XB002 in combination with nivolumab for

advanced solid tumors, including mCRPC (NCT04925284).

DLL3

The DLL3 ligand is involved in the Notch signaling

pathway and exhibits elevated expression levels in neuroendocrine

tumors, while remaining absent in normal tissues (81). The neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs)

represent a cluster of poorly differentiated neuroendocrine tumors

characterized by the upregulation of DLL3. Research findings have

indicated that DLL3 is upregulated in 65–74% of large-cell NECs and

77% of castration-resistant neuroendocrine PCa (NEPC) cells

(82). The Rovalpituzumab tesirine

(Rova-T) ADC specifically targets DLL3 and consists of a mAb that

binds to DLL3 that is linked to a DNA damaging agent via a

cleavable linker (83). In a phase

I/II trial involving NEPC and other advanced NECs that upregulate

DLL3, the primary objective of the study was to evaluate the safety

profile of Rova-T. The most frequently observed grade 3/4 AEs

included anemia (17%), thrombocytopenia (15%) and elevated

aspartate aminotransferase levels (8%) (84). Among the 21 patients with NEPC

enrolled in the trial, the clinical benefit rate reached 76.2%,

with an average PFS time of 4.5 months and an average OS time of

5.7 months. The clinical benefit rate was defined as the percentage

of participants with the best overall response (confirmed or

unconfirmed) of complete response, partial response or stable

disease according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid

Tumors v1.1 (85).

Discussion and perspectives

The treatment options for PCa are evolving rapidly

but more effective treatment options are still needed. ADCs

represent a novel class of tumor targeting therapeutic drugs that

have demonstrated both efficacy and safety in the treatment of

solid tumors such as breast cancer. These agents possess the

ability to selectively recognize antigens that are upregulated on

the surface of cancer cells and subsequently deliver cytotoxic

payloads within these cells to effectively target and eliminate

malignant growth. In recent years, there has been notable progress

in the development of ADCs for PCa. However, these therapeutic

agents have also encountered numerous challenges in effectively

treating PCa, including limited efficacy, safety concerns and a

narrow treatment window (86).

The progression of PCa is driven by androgen

signaling, resulting in a limited response to conventional

chemotherapeutic agents due to slow growth kinetics and activation

of the androgen receptor (87). The

cytotoxic payloads in most ADCs designed for the treatment of PCa

exert their action by suppressing cancer cell division, which could

be one contributing factor to the relatively lower efficacy of ADCs

in PCa compared with other malignancies. However, chemotherapy

drugs currently used for PCa, such as docetaxel and cabazitaxel,

have shown significant efficacy against, and mainly act by

affecting tubulin and then inhibiting the mitotic process (88,89).

The potential difference may stem from the specific expression of

targeted antigens on the surface of cancer cells, as ADCs are

designed to selectively target these antigens, distinguishing them

from conventional chemotherapy drugs. The efficacy and toxicity of

ADCs are also influenced by the inherent structure of the drug and

enhancing any component of the ADC will ameliorate these

issues.

The selection of appropriate targets is pivotal for

the efficacy of ADCs. At present, most antigens targeted in PCa

treatment with ADCs are TAAs, such as PSMA, STEAP1, TROP-2 and

CD46. The development of TSA-targeted ADCs is currently in the

preclinical research stage, with no clinical trials conducted thus

far, to the best of our knowledge. However, it is anticipated that

TSA targeting ADCs may receive approval in the future, offering

potential enhancements in efficacy and a reduction in the

off-target side effects associated with ADCs. In addition to the

cancer cell surface antigen expression profiles, the

internalization and turnover rates of ADCs have a notable impact on

efficacy (90). Thus, optimizing

the binding affinity between antigens and antibodies is a key step

in enhancing the efficacy of ADCs. However, an excessively high

binding affinity can lead to the retention of ADC molecules on the

surface of cancer cells, thereby impeding their internalization

capacity, a phenomenon referred to as the binding site barrier

effect (91).

Optimizing the antibody structure is also a viable

approach to enhance efficacy and to mitigate the toxicity of ADCs

(92). Conditional antibody ADCs

and bispecific ADCs are novel design ideas (13,93).

The activation of conditional antibody ADCs is restricted to cancer

cells, thereby significantly augmenting the efficacy of ADCs and

preventing off-target toxicity (13). In addition, the advancement of

bispecific antibody technology also presents enhanced prospects for

ADC innovation since these antibody ADCs exhibit heightened

internalization efficiency and improved tumor specificity (39). For instance, the utilization of

bispecific ADCs enables the targeting of distinct epitopes on a

single antigen, thereby enhancing both the antigen and antibody

binding affinity while facilitating internalization of ADCs

(94). Similarly, the development

of dual-payload ADCs incorporating diverse cytotoxic payloads

allows for the controlled delivery to cancer cells by manipulating

the drug ratio, resulting in improved efficacy and reduced drug

resistance (95).

Most ADC toxicities originate from off-target,

non-tumor toxicities that are caused by premature detachment of

ADCs in the systemic circulation and subsequent release of the

payload (96). The released payload

can infiltrate neighboring non-malignant cells and induce the

bystander killing effect through passive diffusion or

transporter-mediated uptake (97,98).

Certain ADCs that use microtubule inhibitors as the payload have

off-target toxicity associated with peripheral neuropathy. For

instance, the majority of patients with PCa (71%) who received

MLN2704, a microtubule inhibitor with M1 as the payload,

experienced peripheral neuropathy and were unable to proceed to the

next phase of clinical trials due to excessive toxicity (47). The exploration of novel compounds as

potential payloads for ADCs is imperative to mitigate off-target

toxicity and achieve comparable or superior efficacy in cancer cell

eradication.

The premature release of the payload in the systemic

circulation is primarily responsible for off-target toxicity, as

aforementioned. Therefore, maintaining stability in the systemic

circulation is crucial for linkers to minimize off-target toxicity

of ADCs (99). The ideal linker

should exhibit stability in the bloodstream and selectively release

cytotoxic payloads upon internalization of ADCs into cancer cells.

Nevertheless, existing linkers often demonstrate non-specific

payload release in circulation, inevitably resulting in off-target

toxicity (100). Among the ADCs

designed to treat PCa, hematological toxicities, including

neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, leukopenia and anemia, were observed

as the most prevalent AEs. The occurrence of hematotoxicity may be

attributed to the premature release of cytotoxic payloads into the

systemic circulation (101). The

current requirement is to further advance the development of novel

linkers to ensure the stability of ADCs within the bloodstream and

their targeted release of effective payloads upon internalization

into cancer cells. This will effectively minimize off-target

toxicity and enhance the overall efficacy of ADCs (37).

It has been suggested that combining ADCs with other

therapies possessing distinct mechanisms of action and minimal

overlapping toxic effects may be an effective approach for

mitigating AEs and enhancing efficacy (102). The utilization of ADCs in

conjunction with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has emerged as

a promising therapeutic approach for patients with advanced PCa in

recent years (103). In several

studies, the combination of ADCs and ICIs has been demonstrated to

significantly augment efficacy (104,105). ICIs enhance the capacity of the

immune system to eliminate cancer cells (106), while ADCs selectively target and

eradicate cancer cells (107). The

combination of ADCs and ICIs can therefore augment the cytotoxicity

of the immune system against cancer cells, facilitate targeted

elimination of cancer cells and notably enhance clinical efficacy

(102). Personalized studies of

ADCs in combination with ICIs is currently undergoing clinical

trials, indicating its potential as a promising alternative

treatment for PCa in the future.

At present, ADCs are mainly used to treat patients

with mCRPC. Due to excessive AEs and insufficient efficacy, the

development of ADCs for PCa therapy is still at the phase I/II

clinical trial stage. However, several studies are ongoing and

researchers are also developing new ADCs and improving their

structure. It is conceivable that additional ADCs will receive

approval for the management of PCa in the foreseeable future.

Although most of the ongoing clinical trials focus on patients with

mCRPC, if ADCs show considerable efficacy in more clinical trials,

their potential application for the treatment of patients with

early-stage PCa is likely to materialize.

In conclusion, although there are numerous treatment

options for advanced PCa such as mCRPC, more treatment options are

currently needed. ADCs represent a new hope in the treatment of

PCa. A number of clinical trials investigating ADCs for the

treatment of PCa have been prematurely terminated due to inadequate

efficacy or excessive toxicity. Moving forward, it is imperative to

develop more stable linkers, highly specific antibodies and more

potent payloads to further enhance the pharmacological properties

of ADCs and expand the therapeutic options for patients with

PCa.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science

Foundation of China (grant no. 82360603).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

CY, CG and LW were the major contributors in writing

and editing the manuscript. HL, ZT and MD provided direction and

guidance throughout the preparation of this manuscript. DL, YH, JL,

WC and SF analyzed and organized the data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript. Data authentication

is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J,

Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I and Jemal A: Global cancer statistics

2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for

36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 74:229–263. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Calabrese M, Saporita I, Turco F,

Gillessen S, Castro E, Vogl UM, Di Stefano RF, Carfì FM, Poletto S,

Farinea G, et al: Synthetic lethality by co-inhibition of androgen

receptor and polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose in metastatic

prostate cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 25:782023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Yamada Y and Beltran H: The treatment

landscape of metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 519:20–29.

2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Armstrong AJ, Szmulewitz RZ, Petrylak DP,

Holzbeierlein J, Villers A, Azad A, Alcaraz A, Alekseev B, Iguchi

T, Shore ND, et al: ARCHES: A randomized, phase III study of

androgen deprivation therapy with enzalutamide or placebo in men

with metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol.

37:2974–2986. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Chi KN, Agarwal N, Bjartell A, Chung BH,

de Santana Gomes AJ, Given R, Soto ÁJ, Merseburger AS, Özgüroğlu M,

Uemura H, et al: Apalutamide for metastatic, castration-sensitive

prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 381:13–24. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Davis ID, Martin AJ, Stockler MR, Begbie

S, Chi KN, Chowdhury S, Coskinas X, Frydenberg M, Hague WE, Horvath

LG, et al: Enzalutamide with standard first-line therapy in

metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 381:121–131. 2019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Fizazi K, Tran N, Fein L, Matsubara N,

Rodriguez-Antolin A, Alekseev BY, Özgüroğlu M, Ye D, Feyerabend S,

Protheroe A, et al: Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic,

castration-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 377:352–360.

2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, Liu G,

Jarrard DF, Eisenberger M, Wong YN, Hahn N, Kohli M, Cooney MM, et

al: Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate

cancer. N Engl J Med. 373:737–746. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gillessen S, Armstrong A, Attard G, Beer

TM, Beltran H, Bjartell A, Bossi A, Briganti A, Bristow RG, Bulbul

M, et al: Management of patients with advanced prostate cancer:

Report from the advanced prostate cancer consensus conference 2021.

Eur Urol. 82:115–141. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Verry C, Vincendeau S, Massetti M,

Blachier M, Vimont A, Bazil ML, Bernardini P, Pettré S and Timsit

MO: Pattern of clinical progression until metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer: An epidemiological study from

the European prostate cancer registry. Target Oncol. 17:441–451.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Tilki D, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van

den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, Eberli D, De Meerleer G,

De Santis M, Farolfi A, et al: EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG

guidelines on prostate cancer. Part II-2024 update: Treatment of

relapsing and metastatic prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 86:164–182.

2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Dumontet C, Reichert JM, Senter PD,

Lambert JM and Beck A: Antibody-drug conjugates come of age in

oncology. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 22:641–661. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Drago JZ, Modi S and Chandarlapaty S:

Unlocking the potential of antibody-drug conjugates for cancer

therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 18:327–344. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Beck A, Goetsch L, Dumontet C and Corvaia

N: Strategies and challenges for the next generation of

antibody-drug conjugates. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 16:315–337. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Trail PA, Dubowchik GM and Lowinger TB:

Antibody drug conjugates for treatment of breast cancer: Novel

targets and diverse approaches in ADC design. Pharmacol Ther.

181:126–142. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, Park YH, Kim

SB, Tamura K, Andre F, Iwata H, Ito Y, Tsurutani J, et al:

Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast

cancer. N Engl J Med. 382:610–621. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Modi S, Jacot W, Yamashita T, Sohn J,

Vidal M, Tokunaga E, Tsurutani J, Ueno NT, Prat A, Chae YS, et al:

Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-low advanced

breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 387:9–20. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Bardia A, Hurvitz SA, Tolaney SM, Loirat

D, Punie K, Oliveira M, Brufsky A, Sardesai SD, Kalinsky K, Zelnak

AB, et al: Sacituzumab govitecan in metastatic triple-negative

breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 384:1529–1541. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Strebhardt K and Ullrich A: Paul Ehrlich's

magic bullet concept: 100 years of progress. Nat Rev Cancer.

8:473–480. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Kohler G and Milstein C: Continuous

cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined

specificity. Nature. 256:495–497. 1975. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Carter P: Improving the efficacy of

antibody-based cancer therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 1:118–129. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Schrama D, Reisfeld RA and Becker JC:

Antibody targeted drugs as cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug

Discov. 5:147–159. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Sievers EL: Efficacy and safety of

gemtuzumab ozogamicin in patients with CD33-positive acute myeloid

leukaemia in first relapse. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 1:893–901. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Amiri-Kordestani L, Blumenthal GM, Xu QC,

Zhang L, Tang SW, Ha L, Weinberg WC, Chi B, Candau-Chacon R, Hughes

P, et al: FDA approval: Ado-trastuzumab emtansine for the treatment

of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 20:4436–4441. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Ghose A, Lapitan P, Apte V, Ghosh A,

Kandala A, Basu S, Parkes J, Shinde SD, Boussios S, Sharma A, et

al: Antibody drug conjugates in urological cancers: A review of the

current landscape. Curr Oncol Rep. 26:633–646. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Chang E, Weinstock C, Zhang L, Charlab R,

Dorff SE, Gong Y, Hsu V, Li F, Ricks TK, Song P, et al: FDA

approval summary: Enfortumab vedotin for locally advanced or

metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 27:922–927. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Li K, Xie G, Deng X, Zhang Y, Jia Z and

Huang Z: Antibody-drug conjugates in urinary tumors: Clinical

application, challenge, and perspectives. Front Oncol.

13:12597842023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Tsuchikama K and An Z: Antibody-drug

conjugates: Recent advances in conjugation and linker chemistries.

Protein Cell. 9:33–46. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Giugliano F, Corti C, Tarantino P,

Michelini F and Curigliano G: Bystander effect of antibody-drug

conjugates: Fact or fiction? Curr Oncol Rep. 24:809–817. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Khera E, Dong S, Huang H, de Bever L, van

Delft FL and Thurber GM: Cellular-Resolution imaging of bystander

payload tissue penetration from antibody-drug conjugates. Mol

Cancer Ther. 21:310–321. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Staudacher AH and Brown MP: Antibody drug

conjugates and bystander killing: Is antigen-dependent

internalisation required? Br J Cancer. 117:1736–1742. 2017.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Mjaess G, Aoun F, Rassy E, Diamand R,

Albisinni S and Roumeguere T: Antibody-drug conjugates in prostate

cancer: Where are we? Clin Genitourin Cancer. 21:171–174. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Trail PA, King HD and Dubowchik GM:

Monoclonal antibody drug immunoconjugates for targeted treatment of

cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 52:328–337. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Li Y, Cozzi PJ and Russell PJ: Promising

tumor-associated antigens for future prostate cancer therapy. Med

Res Rev. 30:67–101. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Jin Y, Schladetsch MA, Huang X, Balunas MJ

and Wiemer AJ: Stepping forward in antibody-drug conjugate

development. Pharmacol Ther. 229:1079172022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Conilh L, Sadilkova L, Viricel W and

Dumontet C: Payload diversification: A key step in the development

of antibody-drug conjugates. J Hematol Oncol. 16:32023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Su Z, Xiao D, Xie F, Liu L, Wang Y, Fan S,

Zhou X and Li S: Antibody-drug conjugates: Recent advances in

linker chemistry. Acta Pharm Sin B. 11:3889–3907. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Baah S, Laws M and Rahman KM:

Antibody-drug conjugates-a tutorial review. Molecules. 26:29432021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Fu Z, Li S, Han S, Shi C and Zhang Y:

Antibody drug conjugate: The ‘biological missile’ for targeted

cancer therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7:932022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Samantasinghar A, Sunildutt NP, Ahmed F,

Soomro AM, Salih ARC, Parihar P, Memon FH, Kim KH, Kang IS and Choi

KH: A comprehensive review of key factors affecting the efficacy of

antibody drug conjugate. Biomed Pharmacother. 161:1144082023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Diamantis N and Banerji U: Antibody-drug

conjugates-an emerging class of cancer treatment. Br J Cancer.

114:362–367. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Kaur R, Kaur G, Gill RK, Soni R and

Bariwal J: Recent developments in tubulin polymerization

inhibitors: An overview. Eur J Med Chem. 87:89–124. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Cheung-Ong K, Giaever G and Nislow C:

DNA-damaging agents in cancer chemotherapy: Serendipity and

chemical biology. Chem Biol. 20:648–659. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Ackerman SE, Pearson CI, Gregorio JD,

Gonzalez JC, Kenkel JA, Hartmann FJ, Luo A, Ho PY, LeBlanc H, Blum

LK, et al: Immune-stimulating antibody conjugates elicit robust

myeloid activation and durable antitumor immunity. Nat Cancer.

2:18–33. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Rahbar K, Afshar-Oromieh A, Jadvar H and

Ahmadzadehfar H: PSMA theranostics: Current status and future

directions. Mol Imaging. 17:15360121187760682018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Sun M, Niaz MJ, Niaz MO and Tagawa ST:

Prostate-Specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-targeted radionuclide

therapies for prostate cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 23:592021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Milowsky MI, Galsky MD, Morris MJ, Crona

DJ, George DJ, Dreicer R, Tse K, Petruck J, Webb IJ, Bander NH, et

al: Phase 1/2 multiple ascending dose trial of the

prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted antibody drug conjugate

MLN2704 in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urol

Oncol. 34:530 e515–530 e521. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Henry MD, Wen S, Silva MD, Chandra S,

Milton M and Worland PJ: A prostate-specific membrane

antigen-targeted monoclonal antibody-chemotherapeutic conjugate

designed for the treatment of prostate cancer. Cancer Res.

64:7995–8001. 2004. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Galsky MD, Eisenberger M, Moore-Cooper S,

Kelly WK, Slovin SF, DeLaCruz A, Lee Y, Webb IJ and Scher HI: Phase

I trial of the prostate-specific membrane antigen-directed

immunoconjugate MLN2704 in patients with progressive metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 26:2147–2154.

2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Ma D, Hopf CE, Malewicz AD, Donovan GP,

Senter PD, Goeckeler WF, Maddon PJ and Olson WC: Potent antitumor

activity of an auristatin-conjugated, fully human monoclonal

antibody to prostate-specific membrane antigen. Clin Cancer Res.

12:2591–2596. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Petrylak DP, Kantoff P, Vogelzang NJ, Mega

A, Fleming MT, Stephenson JJ Jr, Frank R, Shore ND, Dreicer R,

McClay EF, et al: Phase 1 study of PSMA ADC, an antibody-drug

conjugate targeting prostate-specific membrane antigen, in

chemotherapy-refractory prostate cancer. Prostate. 79:604–613.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Petrylak DP, Vogelzang NJ, Chatta K,

Fleming MT, Smith DC, Appleman LJ, Hussain A, Modiano M, Singh P,

Tagawa ST, et al: PSMA ADC monotherapy in patients with progressive

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer following

abiraterone and/or enzalutamide: Efficacy and safety in open-label

single-arm phase 2 study. Prostate. 80:99–108. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Cho S, Zammarchi F, Williams DG, Havenith

CEG, Monks NR, Tyrer P, D'Hooge F, Fleming R, Vashisht K, Dimasi N,

et al: Antitumor activity of MEDI3726 (ADCT-401), a

pyrrolobenzodiazepine antibody-drug conjugate targeting PSMA, in

preclinical models of prostate cancer. Mol Cancer Ther.

17:2176–2186. 2018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

de Bono JS, Fleming MT, Wang JS, Cathomas

R, Miralles MS, Bothos J, Hinrichs MJ, Zhang Q, He P, Williams M,

et al: Phase I study of MEDI3726: A prostate-specific membrane

antigen-targeted antibody-drug conjugate, in patients with mCRPC

after failure of abiraterone or enzalutamide. Clin Cancer Res.

27:3602–3609. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Shen J, Pachynski R, Nordquist LT, Adra N,

Bilen MA, Aggarwal R, Reichert Z, Schweizer M, Iravani A, Aung S,

et al: 1804P APEX-01: First-in-human phase I/II study of ARX517 an

anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) antibody-drug

conjugate (ADC) in patients (pts) with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC). Ann Oncol.

34:S974–S975. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Gomes IM, Maia CJ and Santos CR: STEAP

proteins: From structure to applications in cancer therapy. Mol

Cancer Res. 10:573–587. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Rocha SM, Nascimento D, Coelho RS, Cardoso

AM, Passarinha LA, Socorro S and Maia CJ: STEAP1 knockdown

decreases the sensitivity of prostate cancer cells to paclitaxel,

docetaxel and cabazitaxel. Int J Mol Sci. 24:66432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Danila DC, Szmulewitz RZ, Vaishampayan U,

Higano CS, Baron AD, Gilbert HN, Brunstein F, Milojic-Blair M, Wang

B, Kabbarah O, et al: Phase I study of DSTP3086S, an antibody-drug

conjugate targeting six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of

prostate 1, in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J

Clin Oncol. 37:3518–3527. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Doronina SO, Toki BE, Torgov MY,

Mendelsohn BA, Cerveny CG, Chace DF, DeBlanc RL, Gearing RP, Bovee

TD, Siegall CB, et al: Development of potent monoclonal antibody

auristatin conjugates for cancer therapy. Nat Biotechnol.

21:778–784. 2003. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Trerotola M, Ganguly KK, Fazli L, Fedele

C, Lu H, Dutta A, Liu Q, De Angelis T, Riddell LW, Riobo NA, et al:

Trop-2 is up-regulated in invasive prostate cancer and displaces

FAK from focal contacts. Oncotarget. 6:14318–14328. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

61

|

Sperger JM, Helzer KT, Stahlfeld CN, Jiang

D, Singh A, Kaufmann KR, Niles DJ, Heninger E, Rydzewski NR, Wang

L, et al: Expression and therapeutic targeting of TROP-2 in

treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 29:2324–2335.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

62

|

Starodub AN, Ocean AJ, Shah MA, Guarino

MJ, Picozzi VJ Jr, Vahdat LT, Thomas SS, Govindan SV, Maliakal PP,

Wegener WA, et al: First-in-Human trial of a novel anti-trop-2

antibody-sn-38 conjugate, sacituzumab govitecan, for the treatment

of diverse metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 21:3870–3878.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Lang J, Tagawa ST, Slovin S, Emamekhoo H,

Rathkopf D, Abida W, Autio K, Xiao H, Molina AM, Eickhoff J, et al:

1406P Interim results of a phase II trial of sacituzumab govitecan

(SG) in patients (Pts) with metastatic castration resistant

prostate cancer (mCRPC) progressing on androgen receptor signaling

inhibitors (ARSI). Ann Oncol. 33:S11882022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Corti C, Antonarelli G, Valenza C, Nicolò

E, Rugo H, Cortés J, Harbeck N, Carey LA, Criscitiello C and

Curigliano G: Histology-agnostic approvals for antibody-drug

conjugates in solid tumours: Is the time ripe? Eur J Cancer.

171:25–42. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

65

|

Elvington M, Liszewski MK and Atkinson JP:

CD46 and oncologic interactions: Friendly fire against cancer.

Antibodies (Basel). 9:592020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

66

|

Su Y, Liu Y, Behrens CR, Bidlingmaier S,

Lee NK, Aggarwal R, Sherbenou DW, Burlingame AL, Hann BC, Simko JP,

et al: Targeting CD46 for both adenocarcinoma and neuroendocrine

prostate cancer. JCI Insight. 3:e1214972018. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

67

|

Aggarwal RR, Vuky J, VanderWeele DJ,

Rettig M, Heath EI, Beer TM, Huang J, Pawlowska N, Sinit R, Abbey

J, et al: Phase 1a/1b study of FOR46, an antibody drug conjugate

(ADC), targeting CD46 in metastatic castration-resistant prostate

cancer (mCRPC). J Clin Oncol. 40:3001. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Zang X and Allison JP: The B7 family and

cancer therapy: Costimulation and coinhibition. Clin Cancer Res.

13:5271–5279. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

69

|

Bonk S, Tasdelen P, Kluth M, Hube-Magg C,

Makrypidi-Fraune G, Möller K, Höflmayer D, Rico SD, Büscheck F,

Minner S, et al: High B7-H3 expression is linked to increased risk

of prostate cancer progression. Pathol Int. 70:733–742. 2020.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

70

|

Mendes AA, Lu J, Kaur HB, Zheng SL, Xu J,

Hicks J, Weiner AB, Schaeffer EM, Ross AE, Balk SP, et al:

Association of B7-H3 expression with racial ancestry, immune cell

density, and androgen receptor activation in prostate cancer.

Cancer. 128:2269–2280. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

71

|

Guo C, Figueiredo I, Gurel B, Neeb A, Seed

G, Crespo M, Carreira S, Rekowski J, Buroni L, Welti J, et al:

B7-H3 as a therapeutic target in advanced prostate Cancer. Eur

Urol. 83:224–238. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

72

|

Scribner JA, Brown JG, Son T, Chiechi M,

Li P, Sharma S, Li H, De Costa A, Li Y, Chen Y, et al: Preclinical

development of MGC018, a duocarmycin-based antibody-drug conjugate

targeting B7-H3 for solid cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 19:2235–2244.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

73

|

Shenderov E, Mallesara GHG, Wysocki PJ, Xu

W, Ramlau R, Weickhardt AJ, Zolnierek J, Spira A, Joshua AM,

Powderly J, et al: 620P MGC018, an anti-B7-H3 antibody-drug

conjugate (ADC), in patients with advanced solid tumors:

Preliminary results of phase I cohort expansion. Ann Oncol.

32:S657–S659. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Belluomini L, Sposito M, Avancini A,

Insolda J, Milella M, Rossi A and Pilotto S: Unlocking new horizons

in small-cell lung cancer treatment: The onset of antibody-drug

conjugates. Cancers (Basel). 15:53682023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

75

|

Breij EC, de Goeij BE, Verploegen S,

Schuurhuis DH, Amirkhosravi A, Francis J, Miller VB, Houtkamp M,

Bleeker WK, Satijn D and Parren PW: An antibody-drug conjugate that

targets tissue factor exhibits potent therapeutic activity against

a broad range of solid tumors. Cancer Res. 74:1214–1226. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

76

|

Chu AJ: Tissue factor, blood coagulation,

and beyond: An overview. Int J Inflam. 2011:3672842011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

77

|

Versteeg HH: Tissue factor: Old and new

links with cancer biology. Semin Thromb Hemost. 41:747–755. 2015.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

78

|

Markham A: Tisotumab vedotin: First

approval. Drugs. 81:2141–2147. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

79

|

de Bono JS, Concin N, Hong DS,

Thistlethwaite FC, Machiels JP, Arkenau HT, Plummer R, Jones RH,

Nielsen D, Windfeld K, et al: Tisotumab vedotin in patients with

advanced or metastatic solid tumours (InnovaTV 201): A

first-in-human, multicentre, phase 1–2 trial. Lancet Oncol.

20:383–393. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Corti C, Bielo LB, Schianca AC, Salimbeni

BT, Criscitiello C and Curigliano G: Future potential targets of

antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer. Breast. 69:312–322.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

81

|

Saunders LR, Bankovich AJ, Anderson WC,

Aujay MA, Bheddah S, Black K, Desai R, Escarpe PA, Hampl J, Laysang

A, et al: A DLL3-targeted antibody-drug conjugate eradicates

high-grade pulmonary neuroendocrine tumor-initiating cells in vivo.

Sci Transl Med. 7:302ra1362015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

82

|

Puca L, Gavyert K, Sailer V, Conteduca V,

Dardenne E, Sigouros M, Isse K, Kearney M, Vosoughi A, Fernandez L,

et al: Delta-like protein 3 expression and therapeutic targeting in

neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med. 11:eaav08912019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

83

|

Rudin CM, Pietanza MC, Bauer TM, Ready N,

Morgensztern D, Glisson BS, Byers LA, Johnson ML, Burris HA III,

Robert F, et al: Rovalpituzumab tesirine, a DLL3-targeted

antibody-drug conjugate, in recurrent small-cell lung cancer: A

first-in-human, first-in-class, open-label, phase 1 study. Lancet

Oncol. 18:42–51. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

84

|

Mansfield AS, Hong DS, Hann CL, Farago AF,

Beltran H, Waqar SN, Hendifar AE, Anthony LB, Taylor MH, Bryce AH,

et al: A phase I/II study of rovalpituzumab tesirine in delta-like

3-expressing advanced solid tumors. NPJ Precis Oncol. 5:742021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

85

|

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J,

Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S,

Mooney M, et al: New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours:

Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 45:228–247.

2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

86

|

Fuentes-Antras J, Genta S, Vijenthira A

and Siu LL: Antibody-drug conjugates: In search of partners of

choice. Trends Cancer. 9:339–354. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

87

|

Lohiya V, Aragon-Ching JB and Sonpavde G:

Role of chemotherapy and mechanisms of resistance to chemotherapy

in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Med

Insights Oncol. 10:57–66. 2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

88

|

de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, Hansen

S, Machiels JP, Kocak I, Gravis G, Bodrogi I, Mackenzie MJ, Shen L,

et al: Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel

treatment: A randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 376:1147–1154.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

89

|

Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, Horti J,

Pluzanska A, Chi KN, Oudard S, Théodore C, James ND, Turesson I, et

al: Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for

advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 351:1502–1512. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

90

|

de Goeij BE, Satijn D, Freitag CM,

Wubbolts R, Bleeker WK, Khasanov A, Zhu T, Chen G, Miao D, van

Berkel PH and Parren PW: High turnover of tissue factor enables

efficient intracellular delivery of antibody-drug conjugates. Mol

Cancer Ther. 14:1130–1140. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

91

|

Thurber GM, Schmidt MM and Wittrup KD:

Antibody tumor penetration: Transport opposed by systemic and

antigen-mediated clearance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 60:1421–1434. 2008.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

92

|

Ruan DY, Wu HX, Meng Q and Xu RH:

Development of antibody-drug conjugates in cancer: Overview and

prospects. Cancer Commun (Lond). 44:3–22. 2024. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

93

|

Autio KA, Boni V, Humphrey RW and Naing A:

Probody therapeutics: An emerging class of therapies designed to

enhance on-target effects with reduced off-tumor toxicity for use

in immuno-oncology. Clin Cancer Res. 26:984–989. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

94

|

Andreev J, Thambi N, Bay AE, Delfino F,

Martin J, Kelly MP, Kirshner JR, Rafique A, Kunz A, Nittoli T, et

al: Bispecific antibodies and antibody-drug Conjugates (ADCs)

bridging HER2 and prolactin receptor improve efficacy of HER2 ADCs.

Mol Cancer Ther. 16:681–693. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

95

|

Tang F, Yang Y, Tang Y, Tang S, Yang L,

Sun B, Jiang B, Dong J, Liu H, Huang M, et al: One-pot

N-glycosylation remodeling of IgG with non-natural

sialylglycopeptides enables glycosite-specific and dual-payload

antibody-drug conjugates. Org Biomol Chem. 14:9501–9518. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

96

|

Colombo R and Rich JR: The therapeutic

window of antibody drug conjugates: A dogma in need of revision.

Cancer Cell. 40:1255–1263. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

97

|

Tarantino P, Ricciuti B, Pradhan SM and

Tolaney SM: Optimizing the safety of antibody-drug conjugates for

patients with solid tumours. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 20:558–576. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

98

|

Zhu Y, Liu K, Wang K and Zhu H:

Treatment-related adverse events of antibody-drug conjugates in

clinical trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer.

129:283–295. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

99

|

Donaghy H: Effects of antibody, drug and

linker on the preclinical and clinical toxicities of antibody-drug

conjugates. MAbs. 8:659–671. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

100

|

Tumey LN and Han S: ADME considerations

for the development of biopharmaceutical conjugates using cleavable

linkers. Curr Top Med Chem. 17:3444–3462. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

101

|

Mahalingaiah PK, Ciurlionis R, Durbin KR,

Yeager RL, Philip BK, Bawa B, Mantena SR, Enright BP, Liguori MJ

and Van Vleet TR: Potential mechanisms of target-independent uptake

and toxicity of antibody-drug conjugates. Pharmacol Ther.

200:110–125. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

102

|

Chen YF, Xu YY, Shao ZM and Yu KD:

Resistance to antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: Mechanisms

and solutions. Cancer Commun (Lond). 43:297–337. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

103

|

Piombino C, Tonni E, Oltrecolli M, Pirola

M, Pipitone S, Baldessari C, Dominici M, Sabbatini R and Vitale MG:

Immunotherapy in urothelial cancer: Current status and future

directions. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 23:1141–1155. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

104

|

O'Malley DM, Matulonis UA, Birrer MJ,

Castro CM, Gilbert L, Vergote I, Martin LP, Mantia-Smaldone GM,

Martin AG, Bratos R, et al: Phase Ib study of mirvetuximab

soravtansine, a folate receptor alpha (FRalpha)-targeting

antibody-drug conjugate (ADC), in combination with bevacizumab in

patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol.

157:379–385. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

105

|

Uliano J, Nicolo E, Corvaja C, Salimbeni

BT, Trapani D and Curigliano G: Combination immunotherapy

strategies for triple-negative breast cancer: Current progress and

barriers within the pharmacological landscape. Expert Rev Clin

Pharmacol. 15:1399–1413. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

106

|

Thana M and Wood L: Immune checkpoint

inhibitors in genitourinary malignancies. Curr Oncol. 27:S69–S77.

2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

107

|

Bakhtiar R: Antibody drug conjugates.

Biotechnol Lett. 38:1655–1664. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|