Introduction

Preeclampsia is a pregnancy-specific disease

associated with obstruction of uterine spiral arteries, excessive

activation of inflammatory immunity, endothelial cell damage,

genetic factors, metabolic dysfunction and nutritional deficiencies

(1–3). In total, ~4 million women are

diagnosed with preeclampsia annually worldwide, leading to over

70,000 maternal and 500,000 infant deaths (4). The prognosis of preeclampsia remains

elusive, particularly in late onset cases. SPARC plays a crucial

role in placenta development, and its downregulation under hypoxic

conditions potentially contributes to preeclampsia and -associated

intrauterine growth restriction (5). Similarly, maternal microRNA-125b

plasma levels in the first trimester have been shown to strongly

predict pre-eclampsia way before clinical manifestations (6). Women with a history of pre-eclampsia

have approximately double the risk of cardiovascular disease,

including cardiovascular-related death, coronary artery disease,

heart failure and stroke, persisting for up to 39 years of

follow-up (7). According to global

cancer statistics for 2020, breast cancer (BC) is the most common

malignant tumor worldwide, posing serious risks to women's physical

and mental health (8). The

epidemiological link between preeclampsia and BC was first

described in a 1983 case-control study by Polednak and Janerich,

which showed reduced BC risk before age 45 among women with

preeclampsia during their first pregnancy (9). Subsequent studies over the past 40

years have provided increasing evidence of this association.

Neutrophils, the most abundant immune cells, have

been identified to play a significant role in preeclampsia. In

preeclamptic patients, neutrophils are heavily activated,

increasing superoxide production, systemic inflammation and

vascular endothelial damage (10).

Activated neutrophils interact with platelets through signaling

pathways involving chemokines and adhesion factors, contributing to

preeclampsia development (11).

Platelet-activating factor released by platelets also plays a key

role in the condition's pathogenesis (12). Previous studies revealed that

neutrophils accelerate endothelial cell apoptosis through increased

NET expression, a critical step in vascular endothelial injury in

preeclampsia (13). In tumors,

neutrophils, known as tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), are a

heterogeneous and integral component of the tumor microenvironment,

with dual roles in tumor promotion and prevention (14,15).

Fridlender et al (16) in

2009 introduced the N1 (antitumor) and N2 (protumor) nomenclature

for TANs. Neutrophils can mediate cytotoxicity against tumor cells

via reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as hydrogen peroxide and

superoxide, with ROS-mediated elimination depending on TRPM2, an

H2O2-dependent Ca2+ channel

(17). Neutrophils can also present

antigens to T cells, inducing IFN-γ production and adaptive immune

responses, or directly interact with T cells to lower activation

thresholds, aiding tumor cell clearance (18,19).

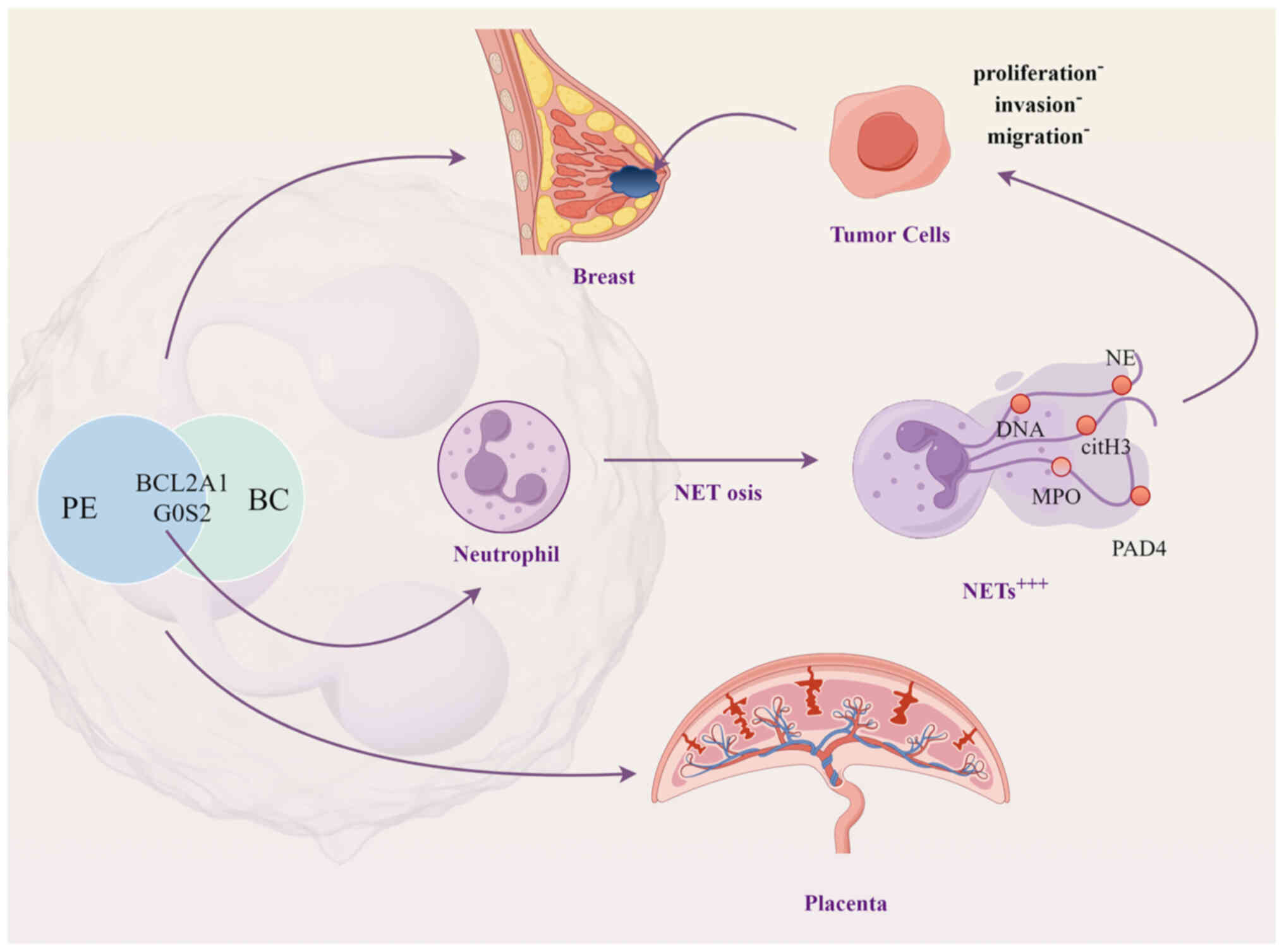

These findings suggest that NETs produced by neutrophils may

provide a crucial link between preeclampsia and reduced BC

risk.

In recent years, integrative genomic analyses have

advanced the understanding of shared pathogenesis between diseases.

The present study employed single-cell sequencing and

bioinformatics to investigate the relationship between neutrophils

and the reduced risk of BC in preeclamptic patients. Supported by

in vitro validation, the findings suggest that NETs mediate

a protective mechanism linking preeclampsia to a reduced risk of

BC. The pivotal roles of BCL2A1 and G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) in

regulating neutrophil activity and NET production underscore their

potential as therapeutic targets for cancer and inflammatory

diseases.

Materials and methods

Reagents and kits

List of reagents and kits used in the study are

provided along with company names and cat. nos. in Table SI.

Data sources

A scRNA-seq dataset (GSE173193) was obtained from

Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). This dataset

contained placental tissue samples of the gestational diabetes

group (n=2), preeclampsia group (n=2), advanced age group (n=2) and

normal control group (n=2). Normal control group (n=2) and

preeclampsia group (n=2) were used to characterize cellular

landscape of preeclampsia.

Single cell sequencing data analysis

processing

Quality control

Initially, the DropletUtils package (20) was utilized to assess the expression

levels of each cell and to filter out barcoded cells that showed no

expression. Next, cells were further filtered based on their unique

molecular identifier counts. Subsequently, the scatter package

(21) was employed to quantify gene

expression in the cells, leading to the exclusion of cells with

mitochondrial gene proportions >10% and ribosomal gene

proportions <10%. Finally, gene counts were obtained.

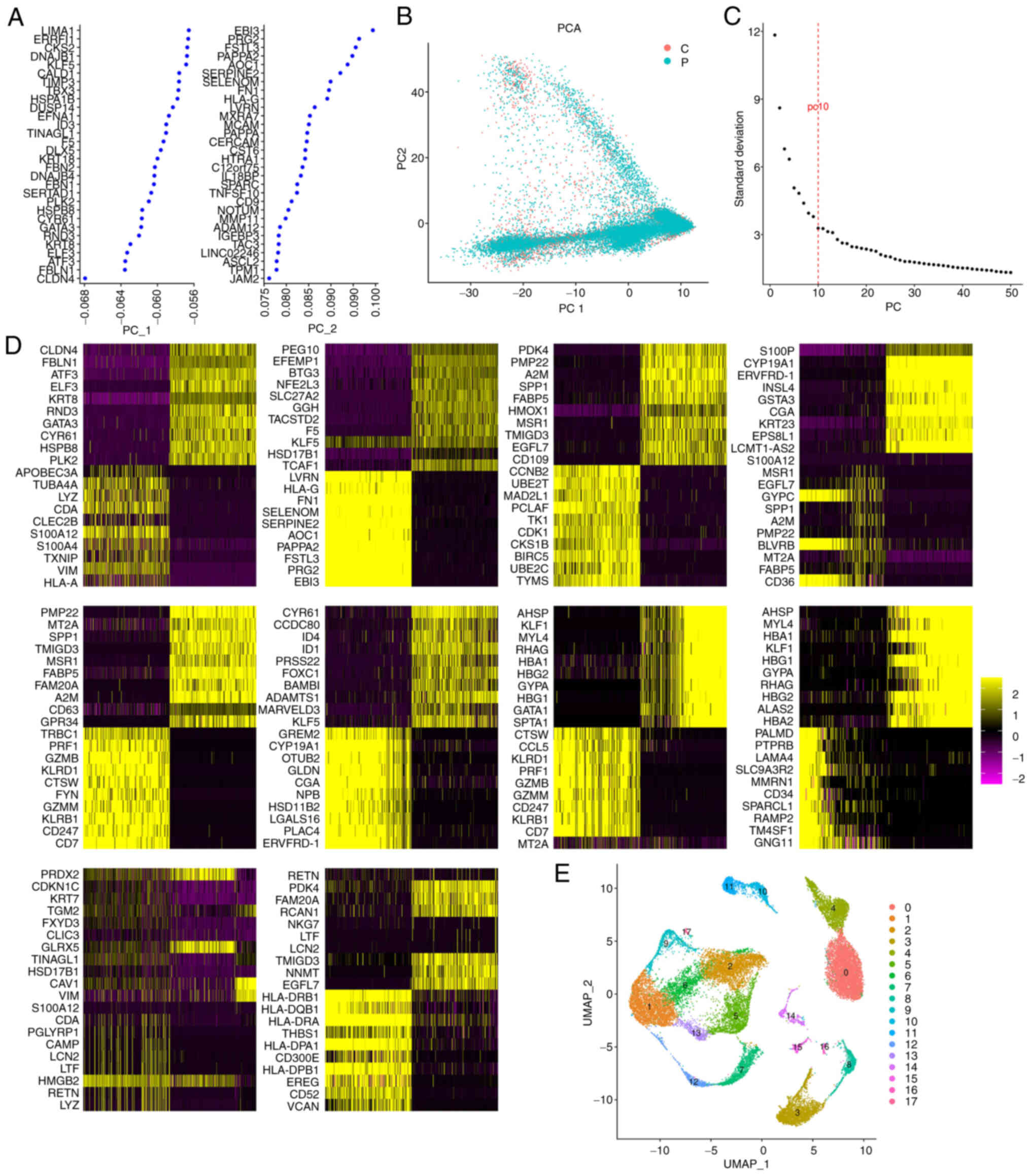

Data preprocessing and principal

component analysis (PCA)

First, the NormalizeData function from the Seurat

package (22) was employed to

standardize the expression matrix of the filtered samples. Next,

the FindVariableFeatures function was used to identify the first

2,000 genes with the most significant differences among cells.

Concentrating on these genes in subsequent analyses will enhance

the detection of biological signals in single-cell datasets.

Following this, the expression data were linearly scaled using the

ScaleData function from the Seurat package. Finally, PCA was

conducted using the RunPCA function within the Seurat package.

Cell cluster and annotation

First, principal components with high standard

deviations were selected. Next, cell clustering analysis was

conducted using the FindNeighbors and FindClusters functions from

the Seurat package. Then, Uniform Manifold Approximation and

Projection (UMAP) for dimensionality reduction was performed using

the RunUMAP function of the Seurat package. Cell types were

annotated based on the known marker genes.

Identification of marker genes

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

between each cluster and all other cells, the FindAllMarkers

function from the Seurat package was utilized. Novel marker genes

were determined based on the following criteria: (log2FC ≥0.1, a

minimum expression ratio of cell population=0.25, and P≤0.05),

resulting in the selection of the top 500 logFC markers (23). Cells were then labeled according to

the known marker genes, and a cluster display diagram was

created.

Cell-cell communication analysis

CellChatv1.1 (24)

was used to infer the communication between cells according to the

corresponding receptor ligand gene expression values of various

cells. And then, the receptor ligand pair network between cells was

obtained.

Pseudotime analysis

Pseudotime analysis was conducted using Monocle

(25). First, genes expressed in at

least 5% of the cells were selected. Next, the reduceDimension

function was applied to perform dimensionality reduction analysis,

followed by clustering of the cells using the clusterCells

function. The differentialGeneTest function was then used to

identify candidate genes that differed between the clusters with a

P<0.05. Dimensionality reduction analysis of the cells was

performed using the DDRTree method and the reduceDimension function

based on the candidate genes. Finally, the orderCells function was

utilized to arrange and visualize the cells along a

quasi-chronological trajectory.

DEG analysis and functional enrichment

analysis

DEGs were identified using the FindMarkers function

(test.use=MAST) in Seurat. A P<0.05 and a log2 fold change

>0.58 were established as the criteria for significant

differential expression. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment and KEGG

pathway enrichment analyses of the DEGs were performed using the

DAVID database, (https://davidbioinformatics.nih.gov/) encompassing all

GO categories, including biological processes, cellular components

and molecular functions.

Identification of significant DEGs in

preeclampsia and BC

The ‘limma’ function from the R suite was employed

to identify DEGs from The Cancer Genome Atlas-BC and GSE24129

datasets. DEGs were classified as those exhibiting |log2 (fold

change)|>1 and P<0.01. The findings are presented using

volcano plots.

Construction and visualization of the

co-expression network

The DEGs were analyzed for co-expression networks

using the R package Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis

(WGCNA) (26). WGCNA was employed

to construct a gene co-expression network based on the standardized

gene data in order to identify the optimal soft threshold. A

scale-free network was built using this best soft threshold, and

the genes were then clustered into functional modules, each

represented by different colors, with clustering and classification

performed using the dynamic tree cutting algorithm. Finally, PCA

was applied to describe the module eigengenes, which reflect a

unique expression profile for all the genes within each module. The

correlations between these eigengenes and clinical characteristics

were calculated to determine which modules were clinically

relevant.

Patient samples

In the present study, the inclusion criteria for

patients with BC included a preoperative diagnosis confirmed by

Mammotome biopsy and no prior history of radiation therapy or

chemotherapy. Tumor tissue samples, along with adjacent normal

tissues (control), were collected from 3 patients with BC, aged 40

to 70 years, with a median age of 55. The inclusion criteria for

patients with preeclampsia required a clear clinical diagnosis,

absence of other complications and a singleton cesarean delivery. A

total of 3 placenta samples were collected from both patients with

preeclampsia and control subjects, aged 20–40 years, with a median

age of 29 in the preeclampsia group and 32 in the control group.

Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants

for the use of tissue samples in scientific research. The present

study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines and

was approved (approval no. 2022-E0118) by the Ethical Review

Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical

University (Nanning, China).

Flow cytometric analysis

The cells obtained from freshly excised preeclampsia

and control tissues were washed and centrifuged (300 × g, 4°C, 5

min), after which a dye was added, and the cells were incubated in

the dark for 30 min before being promptly quantified using flow

cytometry. The detection reagents used were FITC-conjugated

anti-GR-1 (cat. no. 65140-1-Ig; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and

PE-Cy5-conjugated anti-F4/80 (cat. no. B281020; BioLegend, Inc.).

Fluorochrome labeling: GR-1: FITC (detected in FL1 channel) and

F4/80: PE-Cy5 (detected in FL3 channel). BD FACSVerse flow

cytometer (Becton Dickinson) was used, and data analysis was

conducted using FlowJo software (version 10; Tree Star, Inc.).

RNA extraction and reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from preeclampsia and BC

samples using TRIzol® reagent and cDNA was synthesized

with the TRUEscript H Minus M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase. Enzymes

and reagents used included: Reverse transcriptase (TRUEscript H

Minus M-MuLV; cat. no. PC1703; Aidlab), RNase inhibitor (RNasin;

cat. no. RN3501; Aidlab) and nucleotides (dNTP Mixture; 10 mM each;

cat. no. PC2403; Aidlab). All primers were designed using Primer

Premier 5.0 software (https://primer-premier.software.informer.com/) and

were commercially synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd. GAPDH was

used as an internal control. The cDNA was stored at −20°C until

needed. The reverse transcription protocol was performed as

follows: 42°C for 60 min followed by 70°C for 10 min. A two-step

RT-qPCR was conducted with SYBR Green Master Mix (cat. no. PC3302;

Aidlab) to assess the expression levels of BCL2A1 and G0S2.

Thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

94°C for 10 min; followed 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 20

sec, annealing at 55°C for 20 sec and extension at 72°C for 20 sec.

The primers used in the present study are listed in Table SII. GAPDH was used as housekeeping

control. Data were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method

(27).

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from cells lysed in

RIPA buffer (cat. no. P0013B; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

Next, the concentration of proteins was detected by BCA analysis.

The extracted proteins were collected, denatured and separated

using 10% SDS-PAGE gels. The samples (30 µg) were loaded onto the

gels, and electrophoresis was conducted for 120 min. Following

this, the proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and blocked

with 5% skimmed milk by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. After shaking

for 1 h, elution was performed. Next, the membranes were incubated

with primary antibodies (Table

SIII) at 4°C overnight with shaking. Next day, the PVDF

membrane was washed with TBST (0.1% Tween-20) and subjected to

secondary antibody (Table SIII)

incubation for 1 h at room temperature (RT). The images were

acquired using the Infrared electrochemical luminescence (cat. no.

ECL-0011; Beijing Dingguo Changsheng Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The

gray value of the target bands was calculated using ImageJ software

2.0 (National institutes of Health). The experiment was repeated 3

times. The housekeeping gene β-actin was used as loading

control.

Immunofluorescence staining

After rehydration through graded ethanol (100→70%),

tissue sections were washed with PBS and underwent antigen

retrieval (cat. no. P0086; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) via

microwave heating in retrieval buffer at low power for 15 min.

Following PBS washes, sections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton

X-100 for 10 min at RT and blocked with 5% BSA at 37°C for 1 h.

Primary antibodies (anti-BCL2A1 and anti-G0S2; diluted at

1:10,000-1:40,000) were incubated at 37°C for 2 h, followed by 3×5

min PBS washes. Fluorescent secondary antibodies, including

Cy3-labeled anti-rabbit (cat. no. SA00009-2) and FITC-labeled

anti-mouse (cat. no. SA00003-1; both from Proteintech Group, Inc.),

were incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After nuclear staining with Hoechst

(cat. no. P0133; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) at RT for 15

min and final PBS washes, slides were dehydrated in absolute

ethanol for 1 min, air-dried, and mounted with antifade medium

(cat. no. P0128M; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). Images were

acquired using an inverted confocal microscope (IX71; Olympus

Corporation).

Cell culture and transfection

Cells were used to identify neutrophils, which were

subsequently cultured in RPMI-1640 (cat. no. 12633020; Gibco;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) medium supplemented with 10% FBS +

1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells

with favorable proliferation status were transfected with 50 nM

small interfering RNA (siRNA). Cells were seeded in six-well plates

at a density of 5×105 cells per well and cultured until

reaching 80% confluency. Transfection was then performed using

Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by 6

h incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2 before medium change

Neutrophils were divided into 5 groups: Control, vector, BCL2A1-OE,

G0S2-OE and BCL2A1-OE + G0S2-OE. Neutrophils and MCF-7 cells

(5×105 cells/ml) were separately seeded in a two-chamber

culture system. Using a Transwell model, MCF-7 cells were plated in

the lower chamber with culture medium in the upper chamber.

Neutrophils (1×106 cells/ml) were then seeded in the

upper compartment of the Transwell insert and co-cultured with the

lower-chamber breast cancer cells for 24 h under standard

incubation conditions. MCF-7 cells (cat. no. HTB-22) were purchased

from the American Type Culture Collection.

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8)

assays

Assays were conducted using a CCK-8 reagent. The

cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of

1×104 cells per well. Next, 10 µl of CCK-8 was added to

each well in a light-protected environment. The cells were then

incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 1.5 h.

Finally, absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a ThermoMax

microplate reader.

Transwell migration assay

For the cell migration assay, 200 µl of cell

suspension (1×105 cells) was added to the upper

compartment of a Transwell chamber with an 8-µm pore size and a

24-well insert. In each well, 50 µl of serum-free medium

supplemented with 10 g/l BSA was mixed with the co-cultured cells

in the upper chamber. The lower chambers contained 10% FBS. Cell

migration ability was assessed by counting the number of cells that

migrated to the lower chamber of the Transwell using a fluorescence

microscope (IX51; Olympus Corporation).

Cell scratch assay

A total of ~5×105 cells were placed into

a six-well plate, with three replicate wells designated for each

group. Cells were maintained in serum-free medium throughout the

assay. Once the cells adhered to the surface in a single layer, a

200-µl pipette tip was employed to create vertical scratches in the

six-well plate. The cells were then washed three times with PBS,

and the suspension was discarded before incubating the cells in a

chamber with 5% CO2 at 37°C. Images were captured under

a microscope at 0 and 48 h, and the experiment was repeated three

times.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using

GraphPad Prism 8 (version 8.0; Dotmatics) and R software (version

4.2) (https://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.2.0/).

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviations (SDs).

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired two-tailed

t-test for two groups or one-way ANOVA for more than two groups,

followed by Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq)

reveals the cell composition of preeclamptic and control

placentas

To examine cell-type-specific changes in

preeclampsia at the single-cell level, scRNA-seq) was performed on

the GSE173193 dataset, which included two control patients and two

preeclamptic patients. After conducting quality control and

normalization, the first 2,000 highly variable genes within the

cells were identified (Fig. 1A).

Dimensionality reduction was then performed using PCA to analyze

the linearly scaled scRNA data, focusing on the top two principal

components for further investigation. The PCA results indicated a

distinct separation between preeclamptic and control placental

cells (Fig. 1B). Based on the elbow

point criterion, the optimal number of principal components was

determined to be 10 (Fig. 1C).

Heatmaps illustrating the top 20 marker genes for each principal

component are shown (Fig. 1D).

Using the UMAP method, the placental cells were clustered into 18

groups (Fig. 1E). The top ten

marker genes of each cell cluster are presented in Figs. S1 (group 0–8) and S2 (group 9–17).

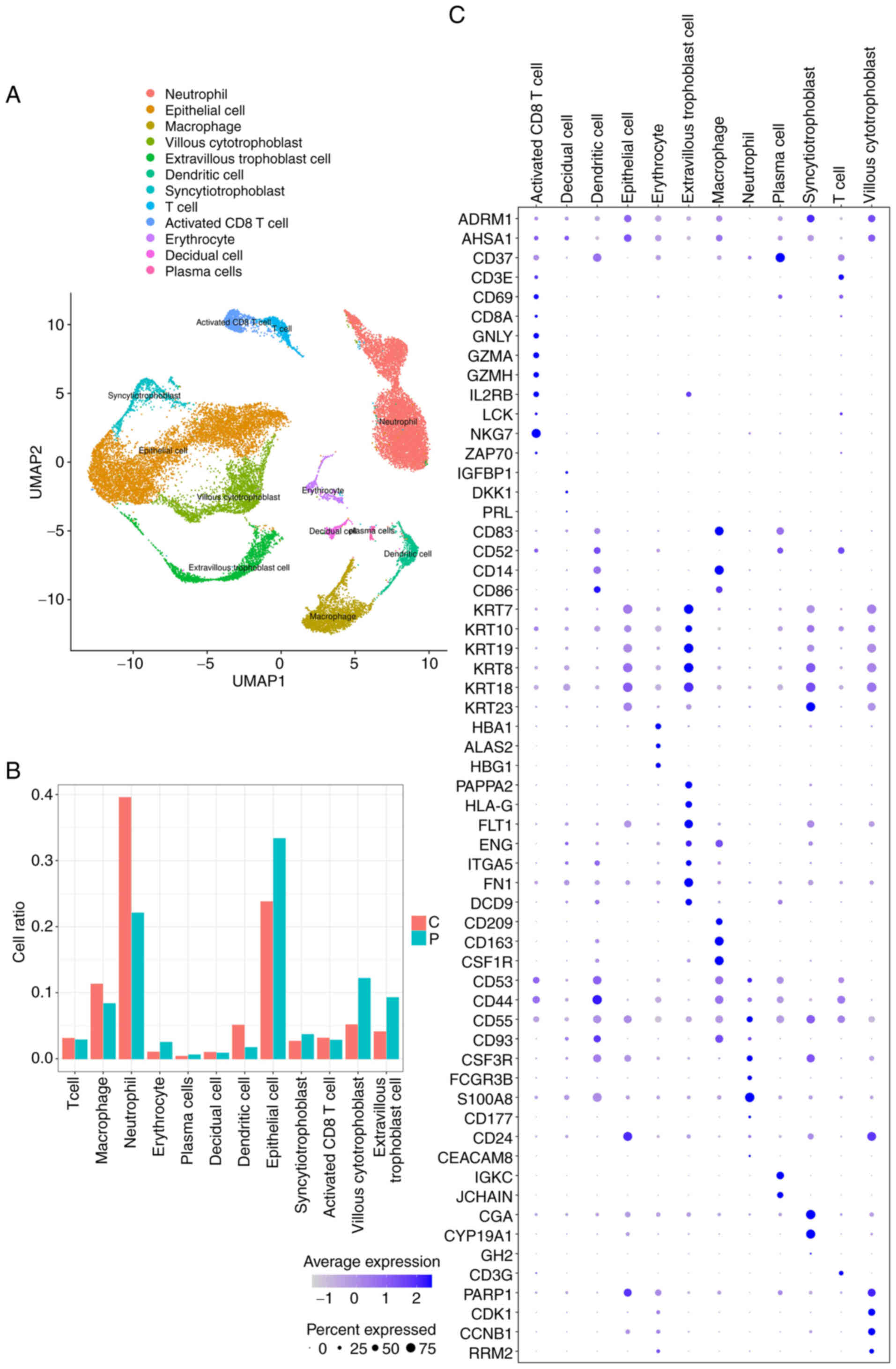

Identification of cell types and their

marker genes in placental cells

Next it was aimed to identify various cell types

within placental cells from both normal individuals and patients

with preeclampsia. Using known marker genes, 12 distinct cell types

were annotated (Fig. 2A). The

relative abundance of each cell type is illustrated in Fig. 2B. Notably, differences in the ratios

of placental cells were observed between preeclampsia patients and

controls. By applying a |logFC|≥0.1, a minimum expression ratio of

the cell population of 0.25, and a P≤0.05, novel marker genes were

identified for each cell type. The top ten marker genes for each

cell type were visualized as follows: Neutrophils (ALOX5AP, BCL2A1,

CAMP, CXCL8, G0S2, IFITM2, RETN, S100A12, S100A8 and S100A9);

villous cytotrophoblast cells (CCNB1, CDK1, HIST1H4C, HMGB1, PTTG1,

STMN1, TUBA1B, TUBB, TYMS and UBE2C); extravillous trophoblast

cells (AOC1, EBI3, FN1, FSTL3, HPGD, NOTUM, PAPPA2, PRG2, SERPINE2

and TAC3); and syncytio-trophoblast cells (CGA, CYP19A1, ERVFRD-1,

GADD45G, GDF15, HOPX, INSL4, KISS1, KRT23 and CSH1) (Fig. S3). Additionally, the expression

levels of the known marker genes used for cell type annotation were

analyzed (Fig. 2C).

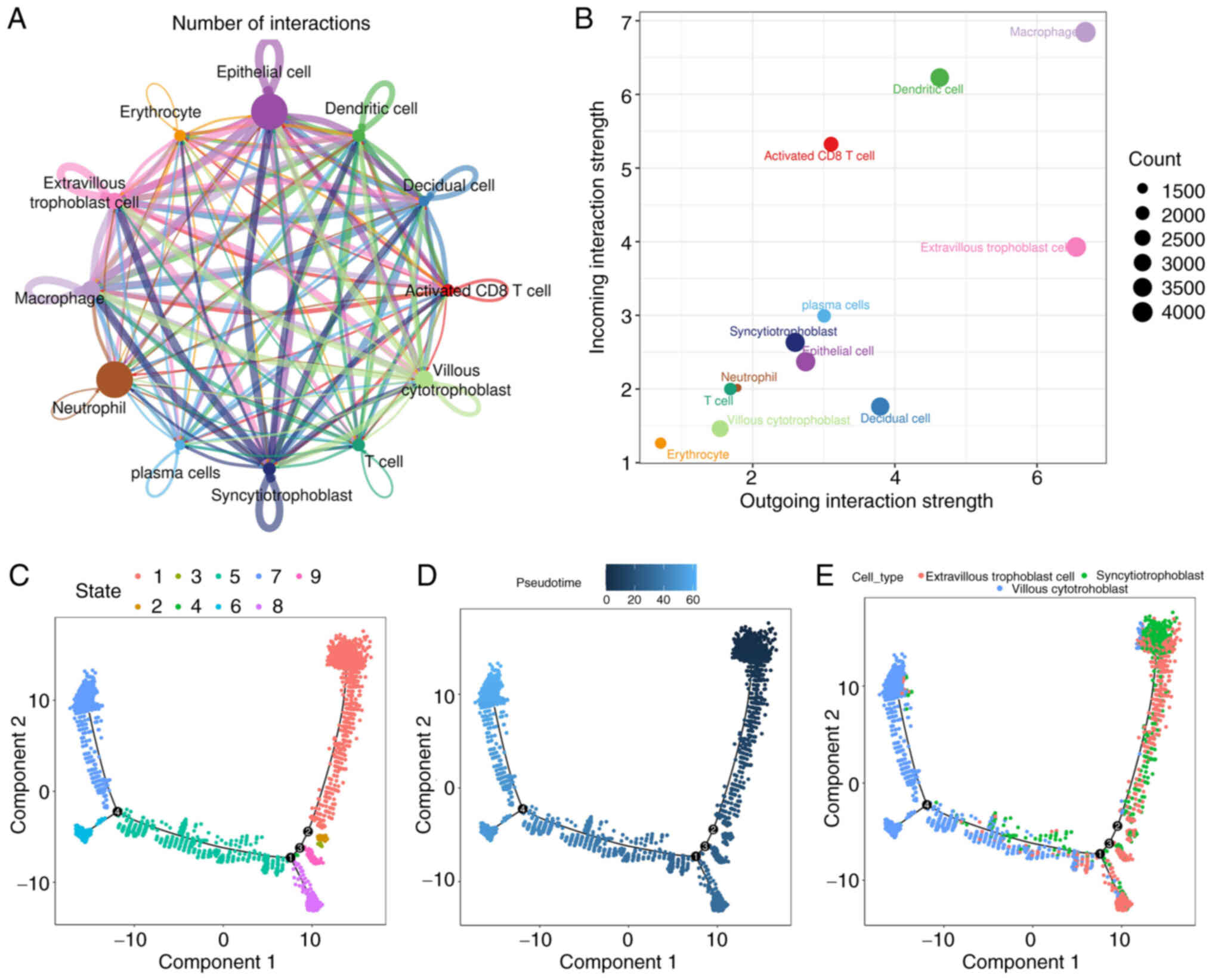

Cell-cell interactions based on

ligand-receptor interactions and reconstruction of the temporal

dynamics of trophoblasts

The placenta is formed through a complex process

that requires the collaborative efforts of various cell lineages.

Intercellular communications among different cell types govern the

proper functions of metazoans and heavily depend on the

interactions between secreted ligands and cell-surface receptors.

Based on marker genes, ligand-receptor interactions were

identified. It was demonstrated that each cell type possesses a

significant number of receptor ligands (Fig. 3A and B). Among these interactions,

those occurring between macrophages and other cells show the

highest number and intensity in the placentas of patients with

preeclampsia. Additionally, there are numerous interactions between

neutrophils and other cells that are characterized by high

intensity as well. Overall, the present findings suggest that

complex intercellular communication occurs within the placental

microenvironment, with distinct changes in this communication.

Furthermore, to explore the evolutionary processes of trophoblasts,

the present study utilized the Monocle tool to uncover

pseudo-temporal ordering due to the similarity of cell clusters

with developmental lineages. The trends of pseudotime-dependent

genes along the pseudo-timeline were categorized into nine cell

clusters of trophoblasts, each exhibiting diverse expression

dynamics. The analysis indicated a progressive development of

trophoblasts from Cluster 7 to Cluster 9 (Fig. 3C-E); syncytio-trophoblast and

extravillous trophoblast cells were positioned at the beginning of

the differentiation process, while villous cytotrophoblast cells

were found at the end. This suggests that extravillous trophoblast

cells or syncytio-trophoblast cells may differentiate into villous

cytotrophoblast cells during the development of preeclamptic

placentas, suggesting that different trophoblast subtypes may

fulfill distinct biological functions.

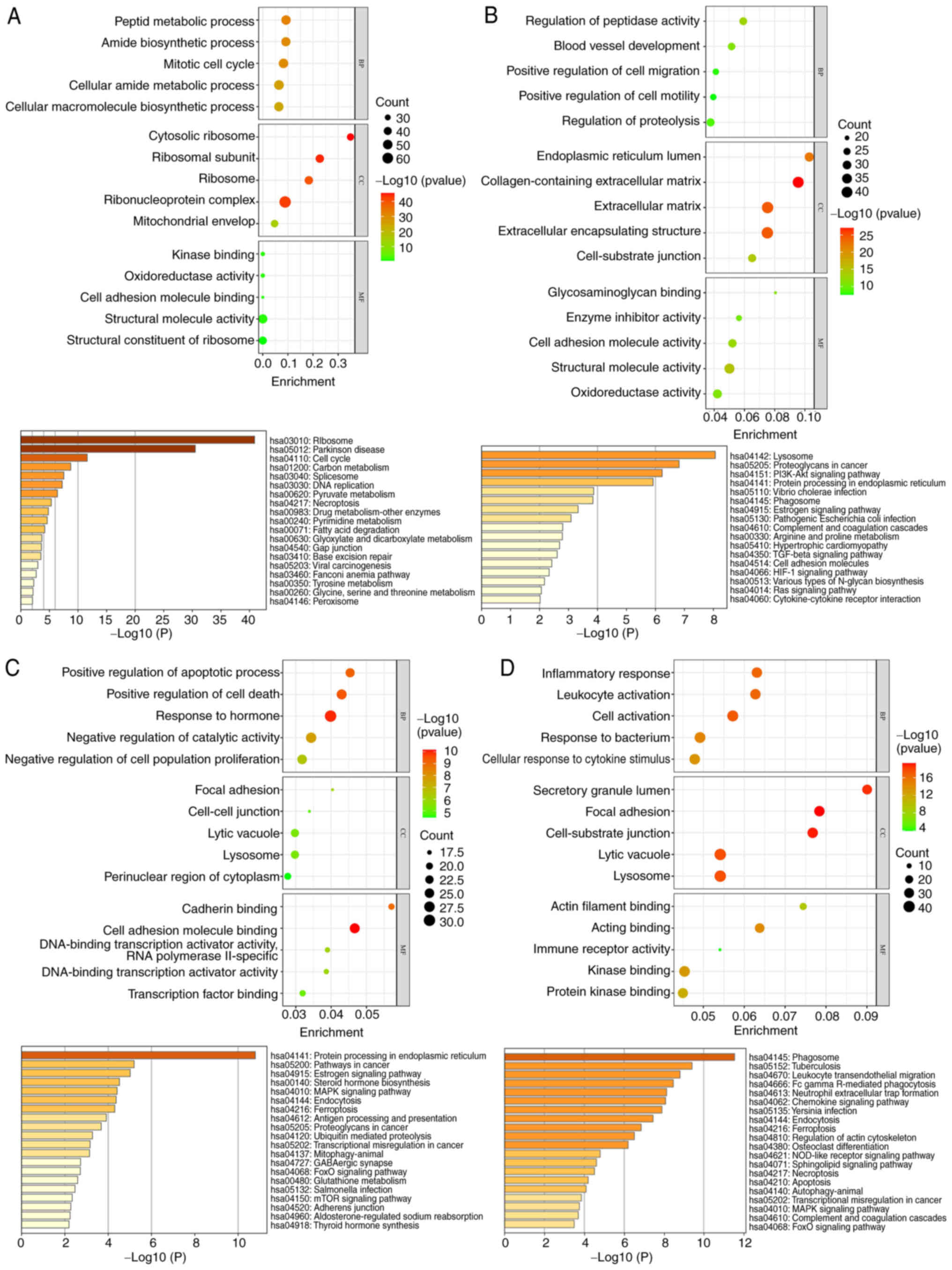

Biological processes associated with

marker genes of trophoblast and neutrophil subsets

To further investigate the functional status and

potential regulatory factors associated with trophoblast and

neutrophil subsets in preeclamptic placentas, GO and Kyoto

Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analyses on the

DEGs identified in the cell populations (Fig. 4A-D) were performed in the present

study. The results indicated that in the annotated villous

cytotrophoblast cell populations, the biological functions were

primarily enriched in the regulation of cell metabolism,

biosynthesis, mitosis and cell cycle processes. This aligns with

the findings of Zhou et al (28). In the annotated extravillous

trophoblast cell population, biological functions were mainly

related to proteolysis, cell migration and movement, angiogenesis

and regulation. For the annotated syncytio-trophoblast cell

population, genes linked to biological functions were enriched in

the positive regulation of cell apoptosis and death, as well as

hormone regulation. In the annotated neutrophil population,

biological functions predominantly involved cell activation,

responses to cytokine stimulation, cell migration, movement, the

actin filament process and the inflammatory response. Regarding

cell components, the genes were mainly enriched in lysosomes and

secretory granules. In terms of molecular function, the genes

showed enrichment primarily in kinase and protein kinase binding,

actin binding, and immune receptor activity. The KEGG pathway

enrichment analysis revealed significant pathways such as

phagosomes, pulmonary tuberculosis, leukocyte migration across the

endothelium, Fcγ receptor-mediated phagocytosis and the formation

of neutrophil extracellular traps.

BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes are

significantly increased in neutrophils from preeclamptic placental

tissue

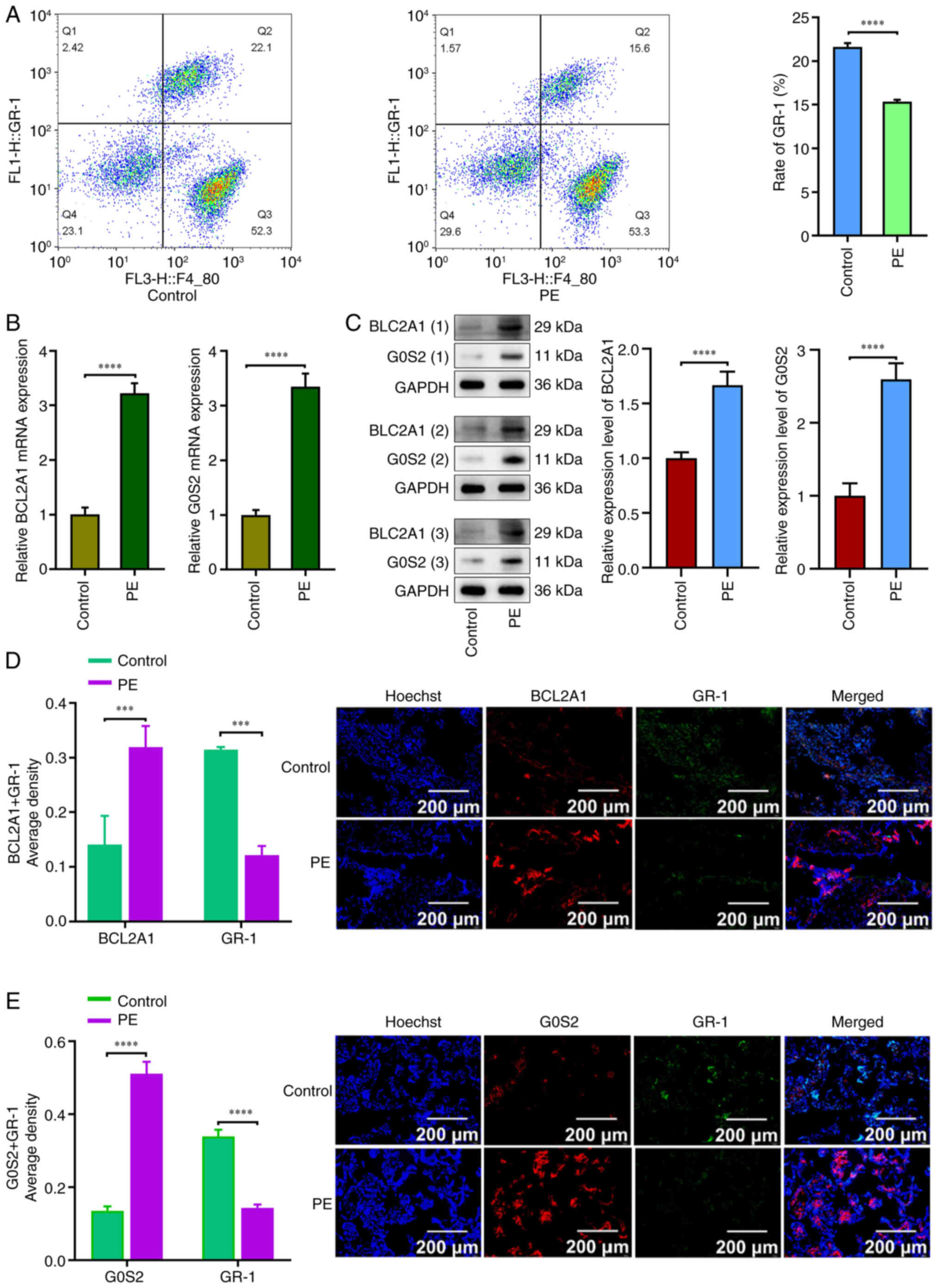

The flow cytometric results indicated that GR-1 was

downregulated in the preeclampsia group compared with the normal

group (P<0.05; Fig. 5A). RT-qPCR

results revealed that BCL2A1 and G0S2 were upregulated in the

preeclampsia group relative to the normal group (P<0.05;

Fig. 5B). Western blot analysis

revealed that the expression of BCL2A1 and G0S2 was increased in

the preeclampsia group compared with the control group (P<0.05;

Fig. 5C). Immunofluorescence

results demonstrated that the expression levels of BCL2A1 and G0S2

were significantly higher in the preeclampsia group than in the

control group, while GR-1 expression was significantly lower in the

preeclampsia group (P<0.05; Fig. 5D

and E).

Overexpression of the BCL2A1 and G0S2

genes in neutrophils promotes the production of NETs

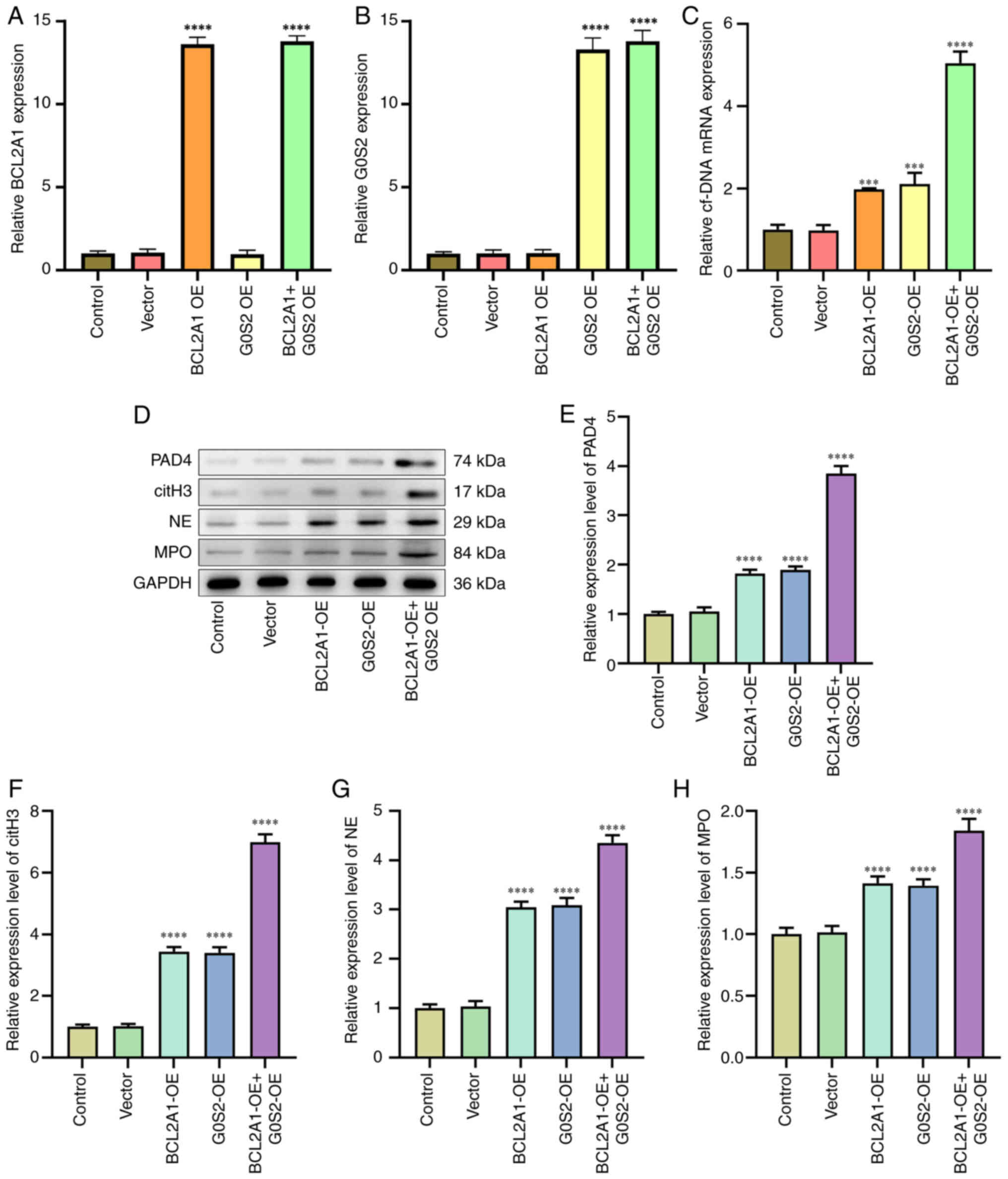

The RT-qPCR results indicated that circulating free

DNA expression was upregulated in the groups overexpressing BCL2A1

and G0S2 compared with the blank group (P<0.05; Fig. 6A-C). Western blot analysis showed

that the expression of PAD4, citH3, NE and MPO was increased in the

BCL2A1-overexpressing and G0S2-overexpressing groups relative to

the blank group (P<0.05; Fig.

6D-H).

Clinical relationship between BCL2A1

and G0S2 genes and BC

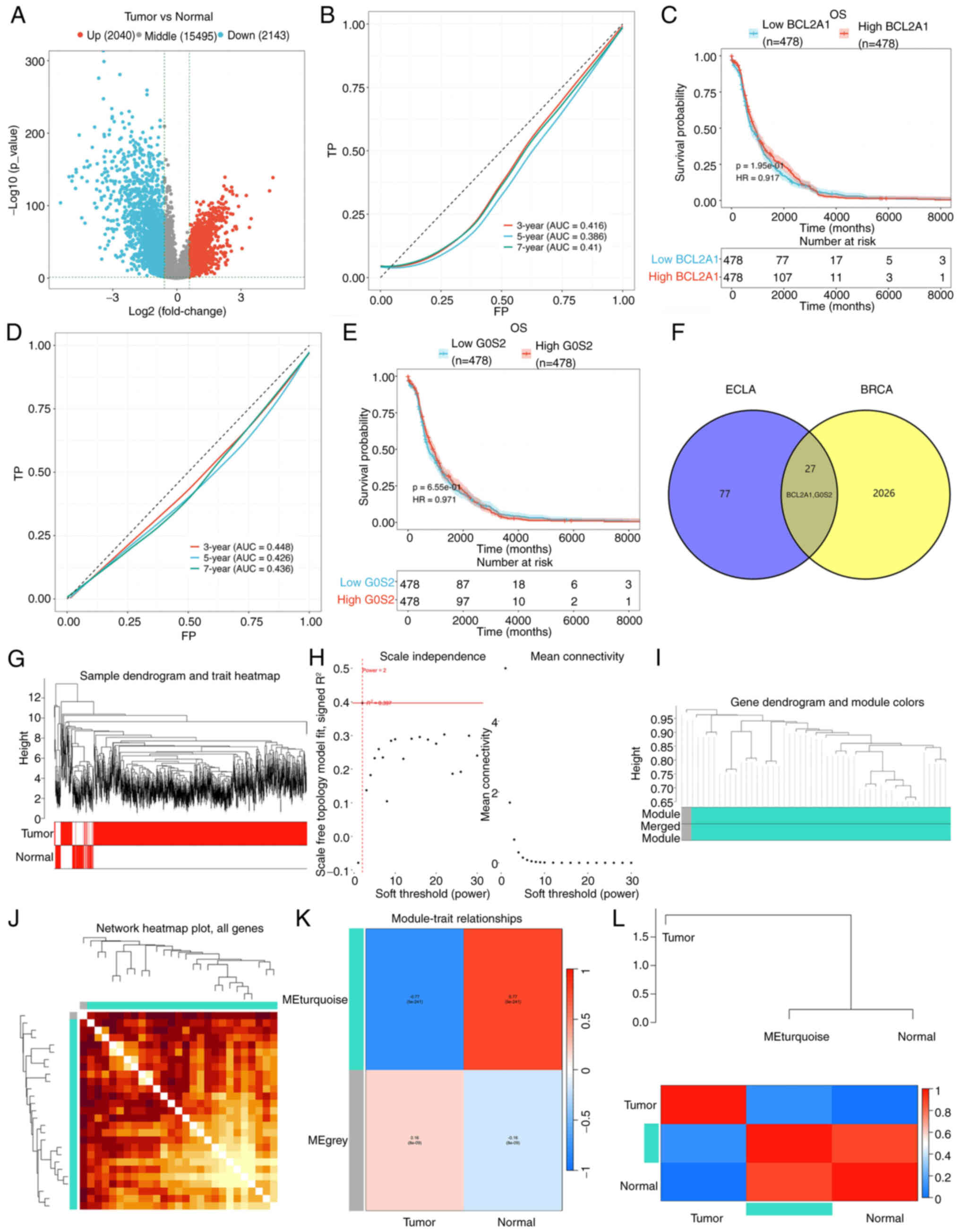

The combined analysis of the GEO (GSE24129) and

TCGA-BC datasets identified 4,183 DEGs, comprising 2,040

upregulated genes and 2,143 downregulated genes (Fig. 7A). The present study specifically

focused on the upregulated genes BCL2A1 and G0S2. Using the TCGA-BC

database, patients were categorized into high- and low-BCL2A1

groups. To assess the diagnostic accuracy of the prognostic risk

model, the areas under the time-dependent ROC curves (AUCs) were

calculated. The AUCs for the risk model in predicting 3-, 5-, and

7-year survival were 0.416, 0.386, and 0.410, respectively

(Fig. 7B). Additionally, patients

with high BCL2A1 expression did not show significantly different

overall survival (OS) compared with those with low BCL2A1

expression (Fig. 7C). In the

subgroup analyses based on G0S2 expression, the AUC of the risk

model for predicting 3-, 5-, and 7-year survival was 0.448, 0.426,

and 0.436, respectively (Fig. 7D).

Patients with high G0S2 expression also did not exhibit

significantly different OS when compared with those with low G0S2

expression (Fig. 7E). These results

indicated that the models lack strong predictive power.

Consequently, further analysis of the DEGs between patients with

preeclampsia and BC was performed using Venn diagrams, which

revealed 27 overlapping upregulated DEGs, including BCL2A1 and G0S2

(Fig. 7F).

Co-expression modules for 27 DEGs

To further investigate these 27 DEGs, WGCNA was

conducted to uncover the interactions and coregulatory mechanisms

among them. A cluster tree of samples was constructed using a

scale-free network and topological overlap based on dynamic hybrid

cutting (Fig. 7G). The optimal soft

threshold was determined according to the fitting index and the

average degree of network connection, in line with the scale-free

topology criterion (Fig. 7H). Based

on this optimal soft threshold, the gene modules were categorized

into two distinct modules, and a module cluster graph was created

(Fig. 7I). A correlation analysis

was performed between the modules and clinical features, presenting

the results in a heatmap (Fig. 7J).

The analysis revealed that the turquoise module exhibited the

strongest correlation with tumors (R=0.77, P=5e-241; Fig. 7K). The genes within this module were

then analyzed and the core genes closely associated with

preeclampsia and BC (BCL2A1 and G0S2) were further identified

(Fig. 7L).

Overexpression of the BCL2A1 and G0S2

genes in neutrophils inhibits malignant progression of BC

cells

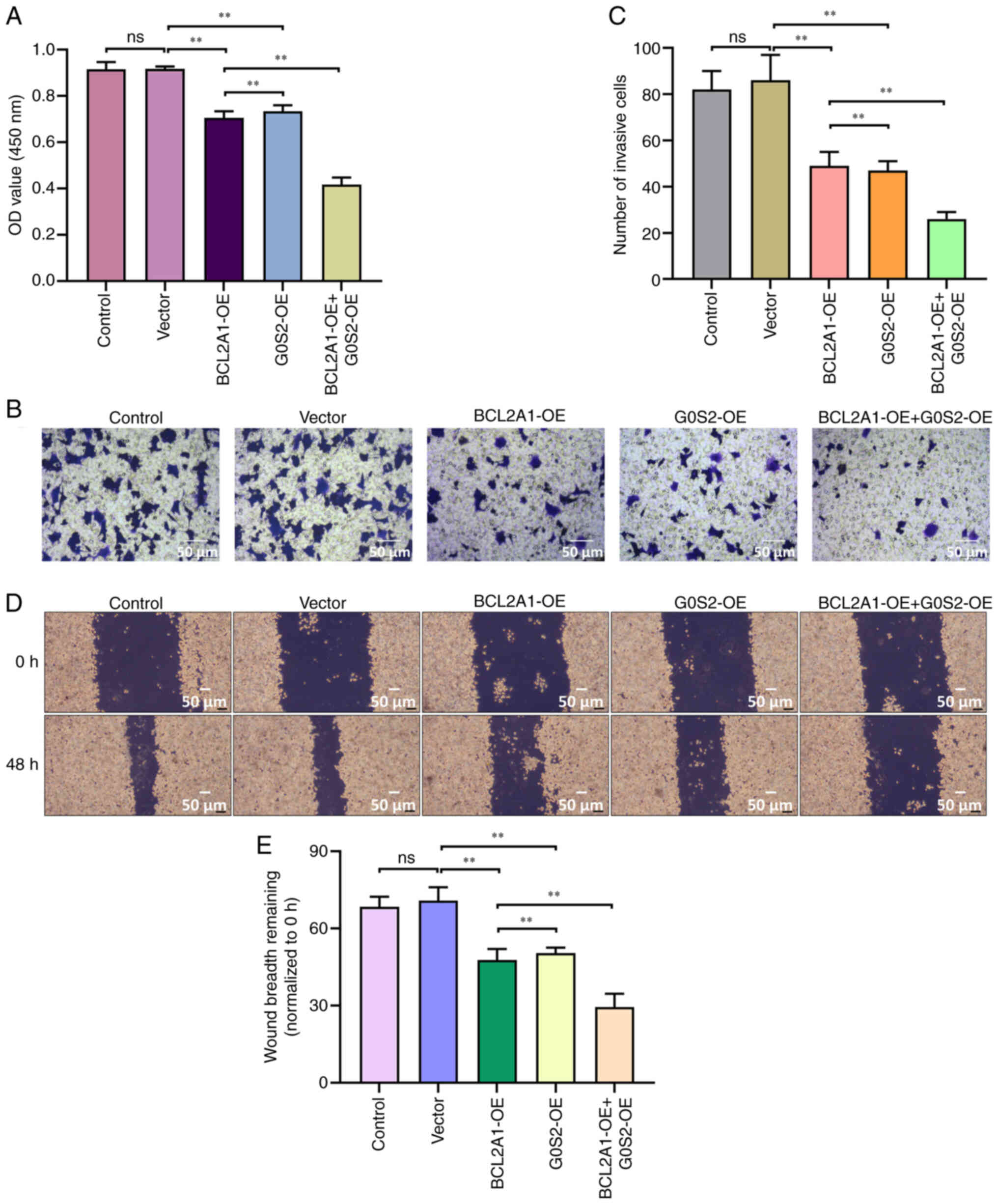

To validate this hypothesis, neutrophils that were

overexpressing BCL2A1 and G0S2 were co-cultured with MCF-7 cells

indirectly, followed by functional analysis. The results from the

CCK-8 assay indicated that the combination of BCL2A1-OE and G0S2-OE

led to a reduced proliferation capacity in MCF-7 cells (P<0.05;

Fig. 8A). Transwell experiments

demonstrated that the BCL2A1-OE + G0S2-OE group showed a

significant reduction in the invasive ability of MCF-7 cells

(P<0.05; Fig. 8B and C).

Additionally, this group also displayed the lowest level of

migration (P<0.05; Fig. 8D and

E). These findings suggest that the co-culture of BC cells with

neutrophils overexpressing BCL2A1 and G0S2 inhibits the

proliferation, invasion and migration of BC cells.

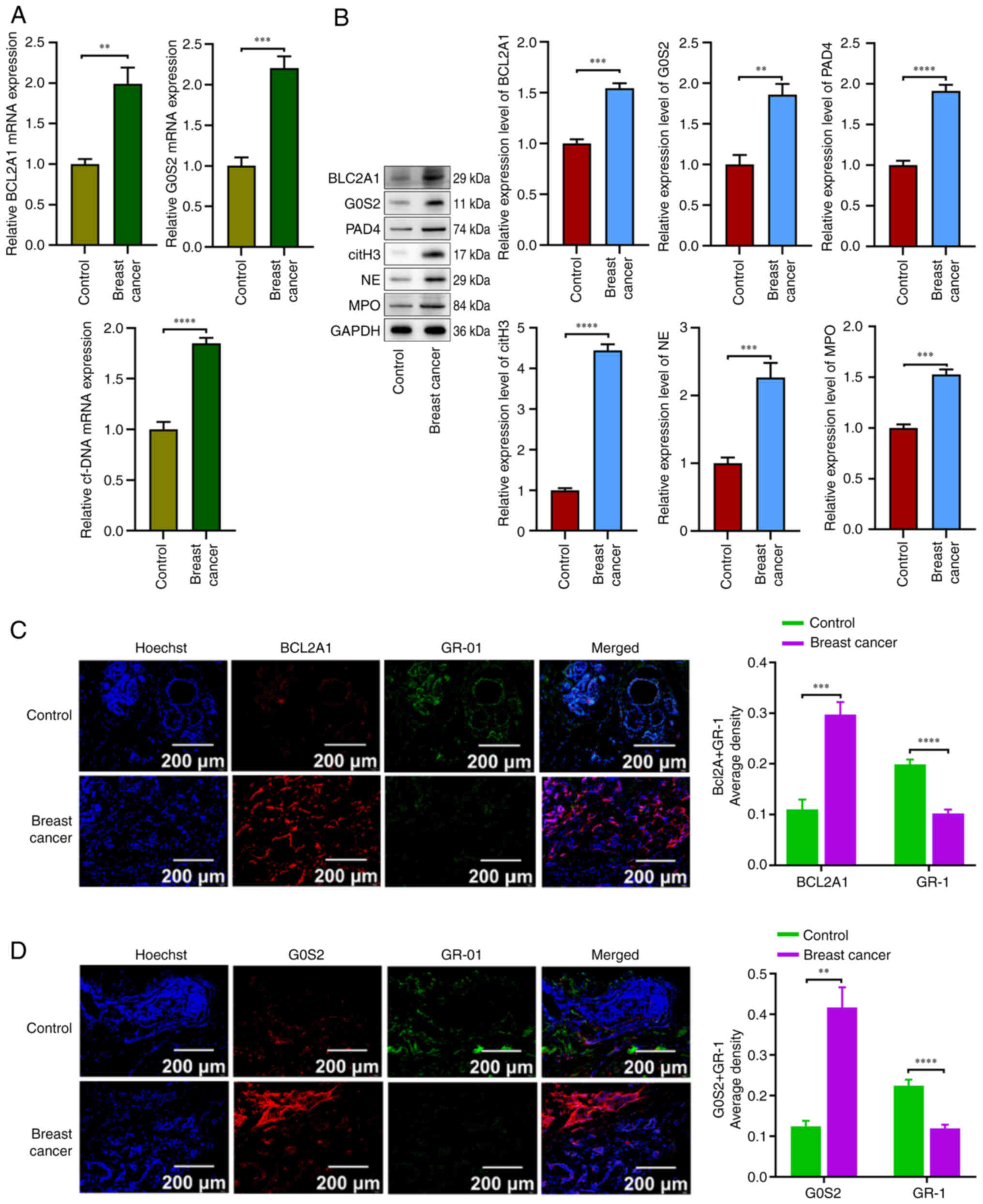

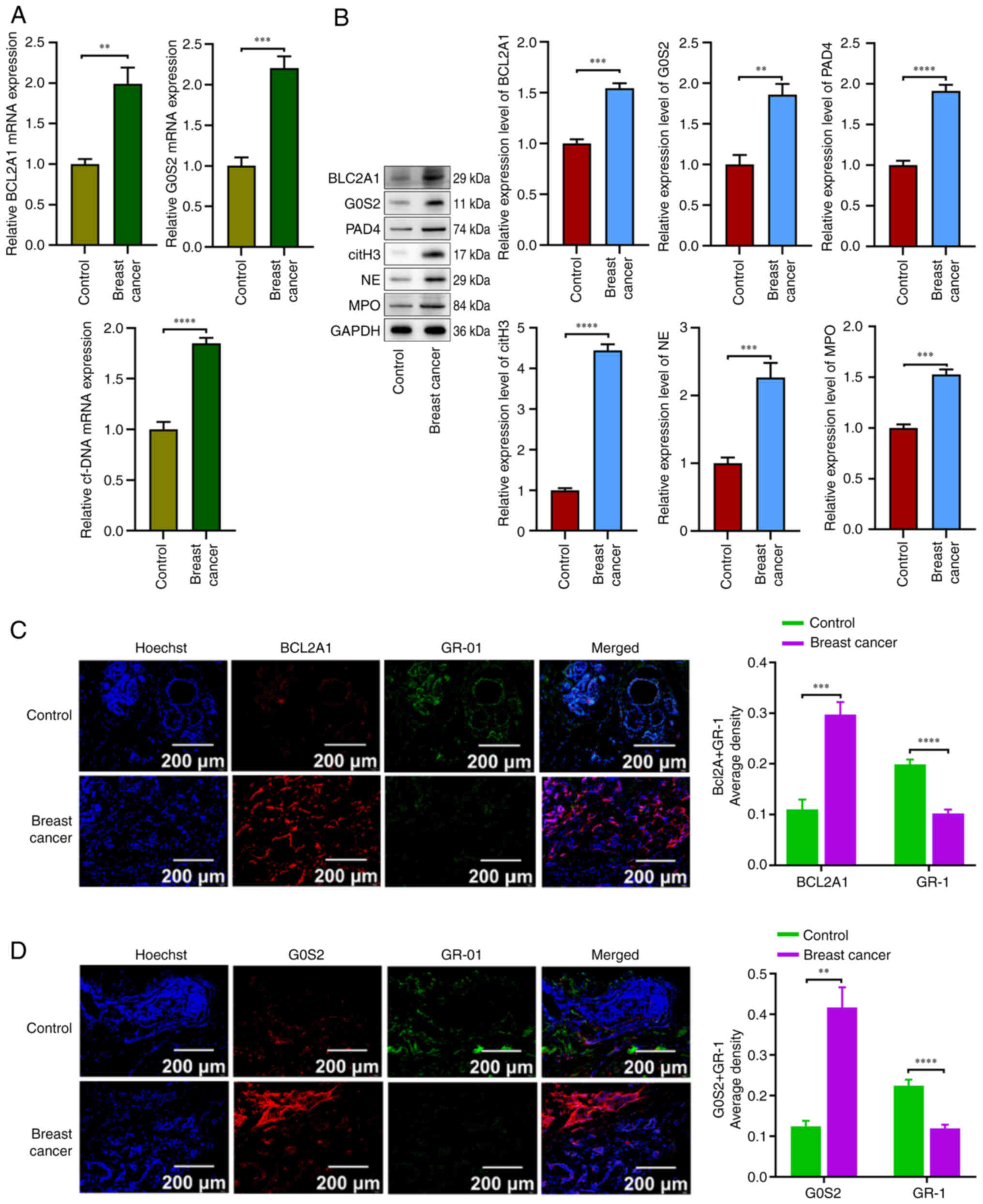

BCL2A1 and G0S2 gene expression levels

were significantly elevated in neutrophils from BC tissue, and

there was also an increase in NETs

To confirm the present findings, the expression

levels of BCL2A1, G0S2, cf.-DNA, PAD4, citH3, NE and MPO in BC

neutrophils were assessed using RT-qPCR and western blotting.

Additionally, immunofluorescence was employed to further validate

the expression of the BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes in neutrophils.

Notably, the RT-qPCR results indicated that the mRNA expression

levels of BCL2A1 and G0S2 were significantly elevated in BC

neutrophils compared with those in the control group (P<0.05;

Fig. 9A). Furthermore, western blot

analysis confirmed that the levels of BCL2A1, G0S2, PAD4, citH3, NE

and MPO were upregulated in the BC neutrophil group compared with

the blank group (P<0.05; Fig.

9B). The immunofluorescence results demonstrated that the

expression of BCL2A1 and G0S2 was significantly higher in the BC

tissue than in the control group, while GR-1 expression was

significantly lower in the BC tissue (P<0.05; Fig. 9C and D). Collectively, these data

suggest that the BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes play essential roles in

regulating neutrophil survival in BC tissues.

| Figure 9.BCL2A1 and G0S2 gene expression

levels were significantly elevated in neutrophils from breast

cancer tissue, along with increase in production of neutrophil

extracellular traps. (A) The mRNA expression level of BCL2A1, G0S2

and cf-DNA in breast cancer tissue compared with control. (B) The

protein expression level of BCL2A1, G0S2, PAD4, citH3, NE and MPO

in breast cancer tissue compared with control. (C and D) Expression

and localization of neutrophils, and BCL2A1 and G0S2 in breast

cancer cells at ×10 magnification. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 and

****P<0.0001. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. MPO,

myeloperoxidase; G0S2, G0/G1 switch gene 2. |

Discussion

A number of epidemiological studies have shown that

preeclampsia can reduce the risk of BC through different pathways

(29–32). However, the specific underlying

mechanism is not yet clear. This is the first study in which

multi-omics analysis, clinical validation and cell culture

experiments have been combined to reveal the specific mechanisms by

which preeclampsia affects the incidence of BC. First, single-cell

sequencing data provided a clear understanding of the

cell-type-specific transcriptome alterations that occur in

preeclampsia placental tissue. The biological processes of 27,724

cells, including trophoblasts and neutrophils, were identified in

12 different cell types. These findings indicate that the

biological activities of these cells are mostly related to the cell

cycle, cell migration, angiogenesis, hormone release and the

inflammatory response. This stage of disease progression is crucial

to our understanding of this disease. Therefore, the authors

focused on the genes whose expression increased in neutrophils,

BCL2A1 and G0S2, to further investigate the relationship between

preeclampsia and BC.

Based on information in the TCGA database, the

associations between the differential mRNA expression in BC,

patients and the BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes, and the survival rate of

patients with BC were examined. Similarly, the expression of the

BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes was elevated in BC. The genes upregulated in

BC from the TCGA database were combined with the preeclampsia

dataset from the GEO database by Venn diagram analysis to identify

27 overlapping genes, including BCL2A1 and G0S2, to study the

relationship between preeclampsia and BC. According to our

findings, the BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes are associated with both

preeclampsia and BC, and they may be crucial in the onset and

progression of these two diseases. Using WGCNA analysis, it was

also discovered that BCL2A1 and G0S2 were both important genes. As

a result, BCL2A1 and G0S2 may be crucial in the disorders

preeclampsia and BC.

Like other Bcl-2 family members, BCL2A1 is crucial

for controlling apoptosis. It has been revealed that BCL2A1 also

plays additional critical roles in vascular endothelial cells. In

activated endothelial cells, TNF-α was found to be a gene caused by

cytokine treatment (33).

Preeclampsia is a significant pregnancy complication characterized

by hypertension, proteinuria, endothelial dysfunction and an

immune-inflammatory response (1).

In the present study, it was discovered that neutrophils from the

placental tissue of preeclampsia patients had considerably greater

BCL2A1 expression. BCL2A1 is specifically involved in the

pathogenesis of preeclampsia. BCL2A1 is a tightly regulated target

gene of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) that plays a crucial role in cell

survival (34). Additionally,

BCL2A1 is primarily expressed in the hematopoietic system, where it

enhances the survival and inflammatory responses of specific

subsets of leukocytes. According to previous studies, BCL2A1 is

overexpressed in various cancer types, including ovarian cancer

(35), BC (36), colon cancer (37) and prostate cancer (38). Furthermore, as an NF-κB target gene,

BCL2A1 also plays a significant role in inflammation (34). Inflammation is a key aspect of the

innate immune response, with NOD-like receptors participating in

inflammasome formation under the influence of pattern recognition

receptors (PRRs). One of the primary signaling pathways activated

by PRRs involves the activation of NF-κB and the upregulation of

proinflammatory genes (39).

Consequently, the formation of inflammasomes may also trigger the

expression of BCL2A1, thereby supporting the survival of

proinflammatory cells during the immune response (34). The present findings suggest that the

overexpression of BCL2A1 in neutrophils could promote apoptosis and

inhibit the proliferation of BC cells, providing a plausible

explanation for this observation.

G0S2 was initially discovered to be involved in the

transition of the cell cycle from the G0 to the G1 phase induced by

lectin (40). The G0S2 gene plays

an important role in cell cycle regulation and apoptosis (41). Studies have shown that G0S2 can

affect cell apoptosis and survival by inhibiting lipolysis and

fatty acid oxidation under certain conditions (42,43).

Furthermore, the expression of G0S2 may be associated with the

function of vascular endothelial cells and vascular pathology. For

example, G0S2 can ameliorate oxidative low-density

lipoprotein-induced vascular endothelial cell damage by regulating

mitochondrial apoptosis (44).

Placental abnormalities and metabolic disorders are important

features of preeclampsia, and adipose metabolism plays a role in

these conditions (45). Moreover,

adipose tissue also plays an important regulatory role in the

progression of breast tumors, as adipose tissue can provide

nutrients and adipokines for proliferating tumor cells. Studies

have shown that fatty acid metabolism also plays an important role

in various aspects of tumor cell proliferation, transformation and

migration (46). It has been

reported that siRNA-mediated knockdown of G0S2 leads to reduced

proliferation, migration and invasion of BC cells, suggesting that

G0S2 is a major factor that promotes the survival and metastasis of

BC cells (47). Notably, the

present findings revealed that the overexpression of G0S2 in

neutrophils can reduce the proliferation, invasion and migration

capacity of BC cells. This suggests that the invasion and migration

of BC cells are influenced by fatty acid metabolism, where the

overexpression of G0S2 can inhibit fatty acid oxidation, thereby

disrupting the invasive and migratory abilities of BC cells.

Furthermore, G0S2 can localize to the endoplasmic

reticulum and mitochondria (48,49).

G0S2 can interact with Bcl-2, preventing the formation of the

Bcl-2/Bax heterodimeric complex by controlling mitochondrial

membrane permeability and cytochrome release, thereby modulating

its antiapoptotic activity in human cancer cells (49). Thus, these results suggest that the

synergistic effect of BCL2A1 and G0S2 in neutrophils can inhibit

the growth and metastasis of BC cells.

Neutrophils are the first line of defense in the

immune system, and they function by phagocytosis and degranulation.

Recent research has unveiled the existence of a distinctive variant

of neutrophil death, known as neutrophil necrosis. This process

actively contributes to the extermination of pathogens through the

extracellular release of NETs (50). NETs are intricate DNA networks

filled with antimicrobial peptides that are diligently discharged

by neutrophils in response to diverse stimuli. NETs are not only

essential for neutrophil innate immune responses but also play a

role in autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus,

rheumatoid arthritis (51) and

psoriasis (52). Additionally, they

are implicated in non-infectious conditions, including

coagulopathies (53), thrombosis

(54), diabetes (55) and atherosclerosis (56). Notably, NETs play dual roles in

tumors, serving both as facilitators and inhibitors of tumor

progression. NETs composed of myeloperoxidase, proteases and

histones can eliminate tumors, and impede tumor proliferation and

metastasis. However, they also have the potential to degrade the

extracellular matrix, promoting the escape and metastasis of cancer

cells (57). In the present study,

an increase was observed in the release of NETs in BC. In

vitro cell experiments indicated that the BCL2A1 and G0S2 genes

regulate the generation of NETs, leading to the inhibition of

proliferation, migration and invasion in BC cells. Consequently,

NETs can potentially impede the malignant progression of BC by

suppressing the biological functions of these cells.

The present study has several limitations. First,

the small public dataset used could skew the outcomes of the

investigation. Second, the present study confirmed a lower risk of

BC in preeclamptic women, which is consistent with the results

reported in the majority of related studies (29–32);

however, there are also conflicting results. A positive correlation

was reported in one study (58),

and it was also reported in two additional studies (59,60).

Finally, additional research is still needed to confirm the

co-expression of BCL2A1 and G0S2 as a reliable indicator of

preeclampsia and BC. In conclusion, the present study proposed that

neutrophils may be co-pathogenic factors between preeclampsia and

BC, and further elucidated that BC risk was reduced in patients

with preeclampsia due to the regulatory role of the BCL2A1 and G0S2

genes in neutrophil-mediated NET production (Fig. 10).

Supplementary Material

Supporting Data

Supporting Data

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by the Guangxi Natural Science

Foundation Program (grant nos. 2023GXNSFAA026037 and

2024GXNSFAA010368), the Guangxi medical and health appropriate

technology development and application project (grant nos. S2022080

and S2022062), the Excellent medical talents training program of

the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University and the

Project on Enhancement of Basic Research Ability of Young and

Middle-aged Teachers in Guangxi Universities and Colleges (grant

no. 2024KY0110).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LX and JinL performed data analysis and prepared

figures. LX, JinL, JiaL, MW and XL performed experiments. LX wrote

the manuscript. JieL and YZ designed and supervised the study, and

revised the manuscript. LX and JL confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors read and approved the final version of

the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all study

participants for the use of tissue samples in scientific research.

The present study was conducted in accordance with the ethical

guidelines and was approved (approval no. 2022-E0118) by the

Ethical Review Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of

Guangxi Medical University (Nanning, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Glossary

Abbreviations

Abbreviations:

|

CCK-8

|

Cell Counting Kit-8

|

|

DEGs

|

differentially expressed genes

|

|

G0S2

|

G0/G1 switch gene 2

|

|

GO

|

Gene Ontology

|

|

KEGG

|

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and

Genomes

|

|

NETs

|

neutrophil extracellular traps

|

|

NF-κB

|

nuclear factor κB

|

|

PCA

|

principal component analysis

|

|

PRRs

|

pattern recognition receptors

|

|

RT-qPCR

|

reverse transcription-quantitative

PCR

|

|

ROS

|

reactive oxygen species

|

|

scRNA-seq

|

single-cell RNA sequencing

|

|

TANs

|

tumor-associated neutrophils

|

|

UMAP

|

Uniform Manifold Approximation and

Projection

|

|

WGCNA

|

weighted gene co-expression network

analysis

|

References

|

1

|

Rana S, Lemoine E, Granger JP and

Karumanchi SA: Preeclampsia: Pathophysiology, challenges, and

perspectives. Circ Res. 124:1094–1112. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

El-Sayed AAF: Preeclampsia: A review of

the pathogenesis and possible management strategies based on its

pathophysiological derangements. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol.

56:593–598. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Piani F, Agnoletti D, Baracchi A,

Scarduelli S, Verde C, Tossetta G, Montaguti E, Simonazzi G, Degli

Esposti D and Borghi C; HDP Bologna Study Group, : Serum uric acid

to creatinine ratio and risk of preeclampsia and adverse pregnancy

outcomes. J Hypertens. 41:1333–1338. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Dimitriadis E, Rolnik DL, Zhou W,

Estrada-Gutierrez G, Koga K, Francisco RPV, Whitehead C, Hyett J,

da Silva Costa F, Nicolaides K and Menkhorst E: Pre-eclampsia. Nat

Rev Dis Primers. 9:82023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Tossetta G, Fantone S, Giannubilo SR,

Marinelli Busilacchi E, Ciavattini A, Castellucci M, Di Simone N,

Mattioli-Belmonte M and Marzioni D: Pre-eclampsia onset and SPARC:

A possible involvement in placenta development. J Cell Physiol.

234:6091–6098. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Licini C, Avellini C, Picchiassi E, Mensà

E, Fantone S, Ramini D, Tersigni C, Tossetta G, Castellucci C and

Tarquini F: Pre-eclampsia predictive ability of maternal miR-125b:

A clinical and experimental study. Transl Res. 228:13–27. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Inversetti A, Pivato CA, Cristodoro M,

Latini AC, Condorelli G and Di Simone N: Update on long-term

cardiovascular risk after pre-eclampsia: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 10:4–13. 2024.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M,

Soerjomataram I, Jemal A and Bray F: Global cancer statistics 2020:

GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36

cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 71:209–249. 2021.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Gilbert JS, Bauer AJ, Gilbert SA and Banek

CT: The opposing roles of anti-angiogenic factors in cancer and

preeclampsia. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 4:2652–2669. 2012.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Miller D, Motomura K, Galaz J, Gershater

M, Lee ED, Romero R and Gomez-Lopez N: Cellular immune responses in

the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. J Leukoc Biol. 111:237–260.

2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Sreeramkumar V, Adrover JM, Ballesteros I,

Cuartero MI, Rossaint J, Bilbao I, Nácher M, Pitaval C, Radovanovic

I, Fukui Y, et al: Neutrophils scan for activated platelets to

initiate inflammation. Science. 346:1234–1238. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Chawla N, Shah H, Huynh K, Braun A,

Wollocko H and Shah NC: The role of Platelet-activating factor and

magnesium in obstetrics and gynecology: Is there crosstalk between

pre-Eclampsia, clinical hypertension, and HELLP syndrome?

Biomedicines. 11:13432023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gupta AK, Hasler P, Holzgreve W and Hahn

S: Neutrophil NETs: A novel contributor to Preeclampsia-associated

placental hypoxia? Semin Immunopathol. 29:163–167. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

McFarlane AJ, Fercoq F, Coffelt SB and

Carlin LM: Neutrophil dynamics in the tumor microenvironment. J

Clin Invest. 131:e1437592021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li MO, Wolf N, Raulet DH, Akkari L, Pittet

MJ, Rodriguez PC, Kaplan RN, Munitz A, Zhang Z, Cheng S and

Bhardwaj N: Innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment.

Cancer Cell. 39:725–729. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V,

Cheng G, Ling L, Worthen GS and Albelda SM: Polarization of

tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: ‘N1’ versus ‘N2’

TAN. Cancer Cell. 16:183–194. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Granot Z, Henke E, Comen EA, King TA,

Norton L and Benezra R: Tumor entrained neutrophils inhibit seeding

in the premetastatic lung. Cancer Cell. 20:300–314. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Giese MA, Hind LE and Huttenlocher A:

Neutrophil plasticity in the tumor microenvironment. Blood.

133:2159–2167. 2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Hirschhorn D, Budhu S, Kraehenbuehl L,

Gigoux M, Schröder D, Chow A, Ricca JM, Gasmi B, De Henau O,

Mangarin LMB, et al: T cell immunotherapies engage neutrophils to

eliminate tumor antigen escape variants. Cell. 186:1432–1447.e17.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Lun ATL, Riesenfeld S, Andrews T, Dao TP,

Gomes T; participants in the 1st Human Cell Atlas Jamboree, ;

Marioni JC: EmptyDrops: Distinguishing cells from empty droplets in

Droplet-based Single-cell RNA sequencing data. Genome Biol.

20:632019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

McCarthy DJ, Campbell KR, Lun AT and Wills

QF: Scater: Pre-processing, quality control, normalization and

visualization of single-cell RNA-seq data in R. Bioinformatics.

33:1179–1186. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Hao Y, Hao S, Andersen-Nissen E, Mauck WM

III, Zheng S, Butler A, Lee MJ, Wilk AJ, Darby C, Zager M, et al:

Integrated analysis of multimodal single-cell data. Cell.

184:3573–3587.e29. 2021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Puthumana J, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Xu L,

Coca SG, Garg AX, Himmelfarb J, Bhatraju PK, Ikizler TA, Siew ED,

Ware LB, et al: Biomarkers of inflammation and repair in kidney

disease progression. J Clin Invest. 131:e1399272021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, Chang

I, Ramos R, Kuan CH, Myung P, Plikus MV and Nie Q: Inference and

analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun.

12:10882021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J,

Pokharel P, Li S, Morse M, Lennon NJ, Livak KJ, Mikkelsen TS and

Rinn JL: The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are

revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat

Biotechnol. 32:381–386. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Langfelder P and Horvath S: WGCNA: An R

package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC

Bioinformatics. 9:5592008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Zhou W, Wang H, Yang Y, Guo F, Yu B and Su

Z: Trophoblast cell subtypes and dysfunction in the placenta of

individuals with preeclampsia revealed by SingleCell RNA

sequencing. Mol Cells. 45:317–328. 2022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Powell M, Fuller S, Gunderson E and Benz

C: A common IGF1R gene variant predicts later life breast cancer

risk in women with preeclampsia. Breast Cancer Res Treat.

197:149–159. 2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Nichols HB, House MG, Yarosh R, Mitra S,

Goldberg M, Bertrand KA, Eliassen AH, Giles GG, Jones ME, Milne RL,

et al: Hypertensive conditions of pregnancy, preterm birth, and

premenopausal breast cancer risk: A premenopausal breast cancer

collaborative group analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 199:323–334.

2023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Opdahl S, Romundstad PR, Alsaker MDK and

Vatten LJ: Hypertensive diseases in pregnancy and breast cancer

risk. Br J Cancer. 107:176–182. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Vatten LJ, Romundstad PR, Trichopoulos D

and Skjaerven R: Pre-eclampsia in pregnancy and subsequent risk for

breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 87:971–973. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

33

|

Karsan A, Yee E, Kaushansky K and Harlan

JM: Cloning of human Bcl-2 homologue: Inflammatory cytokines induce

human A1 in cultured endothelial cells. Blood. 87:3089–3096. 1996.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

34

|

Vogler M: BCL2A1: The underdog in the BCL2

family. Cell Death Differ. 19:67–74. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

Liang R, Yung MMH, He F, Jiao P, Chan KKL,

Ngan HYS and Chan DW: The Stress-inducible BCL2A1 is required for

ovarian cancer metastatic progression in the peritoneal

microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 13:45772021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Murthy SRK, Cheng X, Zhuang T, Ly L, Jones

O, Basadonna G, Keidar M and Canady J: BCL2A1 regulates Canady

Helios Cold Plasma-induced cell death in triple-negative breast

cancer. Sci Rep. 12:40382022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Yue T, Liu X, Zuo S, Zhu J, Li J, Liu Y,

Chen S and Wang P: BCL2A1 and CCL18 are predictive biomarkers of

cisplatin chemotherapy and immunotherapy in colon cancer patients.

Front Cell Dev Biol. 9:7992782021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

38

|

Pucci P, Venalainen E, Alborelli I,

Quagliata L, Hawkes C, Mather R, Romero I, Rigas SH, Wang Y and

Crea F: LncRNA HORAS5 promotes taxane resistance in

castration-resistant prostate cancer via a BCL2A1-dependent

mechanism. Epigenomics. 12:1123–1138. 2020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Takeuchi O and Akira S: Pattern

recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 140:805–820. 2010.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

40

|

Russell L and Forsdyke DR: A human

putative lymphocyte G0/G1 switch gene containing a CpG-rich island

encodes a small basic protein with the potential to be

phosphorylated. DNA Cell Biol. 10:581–591. 1991. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

41

|

Heckmann BL, Zhang X, Xie X and Liu J: The

G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2): Regulating metabolism and beyond.

Biochim Biophys Acta. 1831:276–281. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

42

|

Zhang X, Heckmann BL, Campbell LE and Liu

J: G0S2: A small giant controller of lipolysis and adipose-liver

fatty acid flux. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids.

1862:1146–1154. 2017. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

43

|

Yang X, Lu X and Lombès M, Yang X, Lu X

and Lombès M: The G(0)/G(1) switch gene 2 regulates adipose

lipolysis through association with adipose triglyceride lipase.

Cell Metab. 11:194–205. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

44

|

Liang Z, Diao W, Jiang Y and Zhang Y: G0S2

ameliorates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced vascular

endothelial cell injury by regulating mitochondrial apoptosis. Ann

Transl Med. 10:13832022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

45

|

Kaaja R, Tikkanen MJ, Viinikka L and

Ylikorkala O: Serum lipoproteins, insulin, and urinary prostanoid

metabolites in normal and hypertensive pregnant women. Obstet

Gynecol. 85:353–356. 1995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Wu X, Deng F, Li Y, Daniels G, Du X, Ren

Q, Wang J, Wang LH, Yang Y, Zhang V, et al: ACSL4 promotes prostate

cancer growth, invasion and hormonal resistance. Oncotarget.

6:44849–44863. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

47

|

Cho E, Kwon YJ, Ye DJ, Baek HS, Kwon TU,

Choi HK and Chun YJ: G0/G1 switch 2 induces cell survival and

metastasis through Integrin-mediated signal transduction in human

invasive breast cancer cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul). 27:591–602.

2019. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

48

|

Zandbergen F, Mandard S, Escher P, Tan NS,

Patsouris D, Jatkoe T, Rojas-Caro S, Madore S, Wahli W, Tafuri S,

et al: The G0/G1 switch gene 2 is a novel PPAR target gene. Biochem

J. 392:313–324. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

49

|

Welch C, Santra MK, El-Assaad W, Zhu X,

Huber WE, Keys RA, Teodoro JG and Green MR: Identification of a

protein, G0S2, that lacks Bcl-2 homology domains and interacts with

and antagonizes Bcl-2. Cancer Res. 69:6782–6789. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

50

|

Islam MM and Takeyama N: Role of

neutrophil extracellular traps in health and disease

pathophysiology: Recent insights and advances. Int J Mol Sci.

24:158052023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

51

|

Fresneda Alarcon M, McLaren Z and Wright

HL: Neutrophils in the pathogenesis of rheumatoid arthritis and

systemic lupus erythematosus: Same Foe Different M.O. Front

Immunol. 12:6496932021. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

52

|

Shao S, Fang H, Dang E, Xue K, Zhang J, Li

B, Qiao H, Cao T, Zhuang Y, Shen S, et al: Neutrophil extracellular

traps promote inflammatory responses in psoriasis via activating

epidermal TLR4/IL-36R crosstalk. Front Immunol. 10:7462019.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

53

|

Jin J, Wang F, Tian J, Zhao X, Dong J,

Wang N, Liu Z, Zhao H, Li W, Mang G and Hu S: Neutrophil

extracellular traps contribute to coagulopathy after traumatic

brain injury. JCI Insight. 8:e1411102023. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

54

|

Van Bruggen S and Martinod K: The coming

of age of neutrophil extracellular traps in thrombosis: Where are

we now and where are we headed? Immunol Rev. 314:376–398. 2022.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

55

|

Yang S, Wang S, Chen L, Wang Z, Chen J, Ni

Q, Guo X, Zhang L and Xue G: Neutrophil extracellular traps delay

diabetic wound healing by inducing Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal

transition via the hippo pathway. Int J Biol Sci. 19:347–361. 2023.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

56

|

Sano M, Maejima Y, Nakagama S,

Shiheido-Watanabe Y, Tamura N, Hirao K, Isobe M and Sasano T:

Neutrophil extracellular traps-mediated Beclin-1 suppression

aggravates atherosclerosis by inhibiting macrophage autophagy.

Front Cell Deve Biol. 10:8761472022. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

57

|

Masucci MT, Minopoli M, Del Vecchio S and

Carriero MV: The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps

(NETs) in tumor progression and metastasis. Front Immunol.

11:17492020. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

58

|

Calderon-Margalit R, Friedlander Y, Yanetz

R, Deutsch L, Perrin MC, Kleinhaus K, Tiram E, Harlap S and Paltiel

O: Preeclampsia and subsequent risk of cancer: Update from the

Jerusalem Perinatal Study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 200:63.e1–5. 2009.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

59

|

Brasky TM, Li Y, Jaworowicz DJ Jr,

Potischman N, Ambrosone CB, Hutson AD, Nie J, Shields PG, Trevisan

M, Rudra CB, et al: Pregnancy-related characteristics and breast

cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control. 24:1675–1685. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

60

|

Nechuta S, Paneth N and Velie EM:

Pregnancy characteristics and maternal breast cancer risk: A review

of the epidemiologic literature. Cancer Causes Control. 21:967–989.

2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|