Introduction

Hyperammonemia is a potential complication of

chronic or acute liver disease, as well as various non-hepatic

conditions. The causes of hyperammonemia in adults can generally be

divided into two main categories: Increased ammonia production

(such as via infection, high protein load, multiple myeloma, and

renal failure) and decreased ammonia elimination (such as from

liver failure, drugs, and inborn errors of metabolism) (1). However, hyperammonemia is often caused

by severe liver disease. In fact, the incidence of hyperammonemia

in hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is as high as 90% (2). Clinically, HE is a group of

neuropsychiatric signs and symptoms in patients with liver disease

or a portosystemic shunt. HE can be reversed by early treatment of

the underlying causes (3,4). Neuroimaging, particularly magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI), plays a vital role in elucidating the

neural mechanisms underlying HE (5). The brain MRI of patients with chronic

HE typically shows cerebral atrophy and bilateral symmetrical

hyperintensities of the globus pallidus on T1-weighted images

without corresponding signal intensity in T2-weighted images

(6,7). Conversely, acute hyperammonemic

encephalopathy often presents bilateral symmetrical cortical signal

abnormalities with corresponding signal intensity changes in

T2-weighted images and diffusion restriction (7-10).

The current study aims to present the clinical

characteristics and brain MRI findings of acute HE associated with

hyperammonemia in 5 adult patients.

Case report

Patients and methods

This retrospective case series study included 5

patients >18 years of age, treated between January 2016 and

December 2021 at King Fahad Specialist Hospital-Dammam (KFSH-D)

(Dammam, Saudi Arabia). The patients were all identified to have

documented hyperammonemic HE. The study was approved by the Ethics

Committee of King Fahad Specialist Hospital Dammam

(IRB-Pub-024-01). Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from all subjects. Clinical and laboratory data were

collected using electronic medical records for each patient. All 5

patients were critically ill in the intensive care unit (ICU) due

to a decline in their level of consciousness. The patients

underwent an MRI of the brain 3-10 days after the onset of

symptoms. A neuroradiologist analyzed all the images. The common

clinical features of the patients were that they presented with

decreased levels of consciousness secondary to acute hepatic

failure with hyperammonemia. The brain MRI of each patient was

performed using a 3-T MRI scanner (Magnetom Skyra; Siemens

Healthineers) with a 20-channel phased array head coil. The imaging

protocol included axial and sagittal T1-weighted images, axial and

coronal T2-weighted images, axial fluid-attenuated inversion

recovery (FLAIR), axial susceptibility weighted imaging, axial

echo-planar diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent diffusion

coefficient map. Additional axial and sagittal T1-weighted images

were recorded for 2 patients after administering the intravenous

contrast agent.

Results

A total of 5 patients (2 men and 3 women) were

included in this study (Table I).

The causes of hepatic failure were metastatic colon cancer, chronic

inflammatory hepatitis in the background of sickle cell anemia,

primary sclerosing cholangitis associated with ulcerative colitis,

autoimmune hepatitis, and post-bypass surgery steatohepatitis,

respectively. Plasma ammonia levels ranged from 165 to 512 µmol/l

(normal range, 11-32 µmol/l). Diffuse cortical swelling was

observed in the MRI brain scans of all patients, involving the

frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes, as well as the insula. The

underlying white matter, peri-rolandic area, and posterior

occipital lobe were spared. These cortical MRI abnormalities have

been shown to worsen with increased ammonia levels (Table I). In 4 of the 5 patients, the

bilateral thalami were affected, and another patient showed a few

focal ischemic lesions in the caudothalamic groove and splenium of

the corpus callosum. Of the 5 patients, 2 survived, while 3 died

due to septic shock and multiorgan failure.

| Table IClinical summary of cases

reported. |

Table I

Clinical summary of cases

reported.

| Characteristic | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|

| Age, years | 37 | 27 | 36 | 18 | 51 |

| Sex | Male | Male | Female | Female | Female |

| Diagnosis | Acute liver failure

secondary to liver surgery | Decompensated liver

failure | Acute graft rejection

post-liver transplant | Acute liver failure

secondary to autoimmune hepatitis | Acute-on-chronic

steatohepatitis |

| GCS | 4/15 | 3/15 | 4/15 | 4/15 | 5/15 |

| Presence of

seizures | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Liver enzymes,

U/la | AST, 105; ALT,

228 | AST, 263; ALT,

137 | AST, 1,856; ALT,

1,325 | AST, 1,914; ALT,

5,075 | AST, 93; ALT, 63 |

| Ammonia level,

µmol/lb | 165-188 | 193 | 512.75 | 310 | 174 |

| Total bilirubin

µmol/lc | 211 | 886 | 344.6 | 334 | 158 |

| Period between onset

of symptoms and MRI, days | 7 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 10 |

| Area of brain

involvement in MRI | Insular cortex,

frontal lobe sparing the peri-rolandic region, posterior temporal

lobe, anterior cingulate gyrus and the bilateral anterola-teral

thalami | Insular cortex,

frontal lobe sparing the peri-rolandic region, temporal lobe,

parietal lobe, and anterior cingulate gyri | Insular cortex,

frontal lobe sparing the peri-rolandic region, temporal lobe,

parietal lobe, anterior and posterior cingulate gyri, and the

bilateral thalami | Insular cortex,

frontal lobe sparing the peri-rolandic region, temporal lobe,

parietal lobe, anterior and posterior cingulate gyri, and the

bilateral postero-medial thalami | Insular cortex,

frontal lobe sparing the peri-rolandic region, posterior temporal

lobe, parietal lobe, and anterior cingulate gyrus. |

| Outcome | Recovered | Died | Died | Died | Recovered |

Case 1

A 37-year-old man with a known case of colon

adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis was admitted electively in

November 2017 under the care of the hepatobiliary team at KFSH-D

for a hepatectomy. However, the procedure was complicated by portal

vein air thrombosis and hypotension, necessitating an ICU

admission. The serum ammonia level was significantly elevated at

165 µmol/l. Additionally, liver enzymes were increased, with an

aspartate transferase (AST) level of 105 U/l (normal range, 8-38

U/l), an alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of 228 U/l (normal

range, 17-45 U/l), a total bilirubin level of 211 µmol/l (normal

range, 4-21 µmol/l) and an international normalized ratio (INR) of

2.4 (normal range, 0.80-1.20). The patient's level of consciousness

remained low even after sedation was stopped. Initially, the

patient [Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 6/15] could open their

eyes in response to painful stimulation, but had no verbal or motor

responses, although the brainstem reflexes were intact.

Routine electroencephalography (EEG) showed

generalized slowing within the delta range and no epileptiform

discharges or electrographic seizures. The brain MRI on the seventh

day post-surgery demonstrated bilateral symmetrical cortical edema

with marked diffusion restriction involving the insula, temporal

lobe, cingulate gyrus, and thalami (Fig. 1). After 10 days, the patient's

condition deteriorated even more. The liver enzymes increased (AST,

84 U/l; ALT, 139 U/l; and total bilirubin, 245 µmol/l), and the

serum ammonia level reached 188 µml/l due to acute liver failure. A

subsequent follow-up MRI revealed an increase in bilateral

symmetrical, predominantly cortical edema, with intermediate signal

intensity on T2/FLAIR, but a decrease in diffusion restriction

(Fig. 2). The patient exhibited

marked improvement gradually throughout the month following the

liver transplant. A follow-up was conducted in the clinic 2 months

after discharge, and the patient was doing well. Furthermore, the

follow-up lab results indicated a significant recovery of liver

enzymes, with AST at 23 U/l, ALT at 24 U/l, and serum ammonia at 19

µml/l. However, the patient declined further brain imaging due to

the resolution of the symptoms.

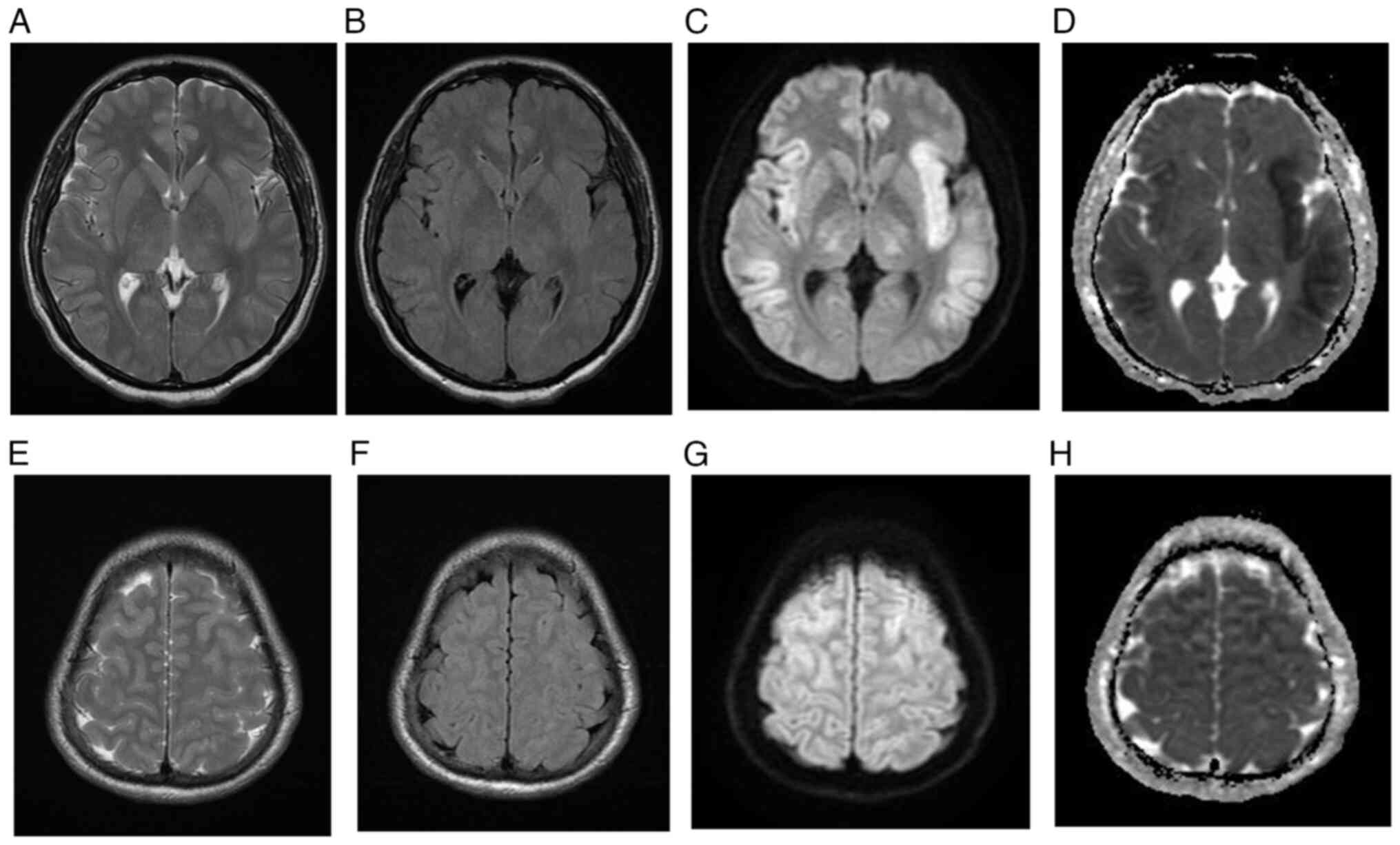

| Figure 1Initial brain MRI for case 1. (A)

T2-weighted MRI, (B) FLAIR, (C) DWI and (D) ADC map demonstrating

asymmetric cortical high T2 and FLAIR signal intensity involving

the bilateral insular cortex, temporal lobes, cingulate gyri and

bilateral lateral thalami with corresponding diffusion restriction.

The bilateral occipital lobes are spared. At the level of vertex,

(E) T2-weighted image, (F) FLAIR image, (G) DWI and (H) ADC map

demonstrating symmetric cortical high T2 and FLAIR signal

intensities involving the frontal and parietal lobes with

corresponding restricted diffusion. The bilateral peri-Rolandic

regions are spared. FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery;

DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion

coefficient. |

Case 2

A 27-year-old man with a known history of sickle

cell disease and chronic inflammatory hepatitis was admitted to the

ICU of the Procare Hospital (Khobar, Saudi Arabia) with low

consciousness and severe jaundice. In December 2018, the patient

was transferred to KFSH-D, where a diagnosis of decompensated liver

failure complicated by disseminated intravascular coagulation and

multiorgan failure was formed based on clinical and laboratory

findings. During the physical examination, it was observed that the

patient was in a deep coma, with a GCS score of 3 out of 15 and

intact brainstem reflexes. The patient exhibited generalized

hypotonia and did not respond to painful stimuli. The deep tendon

reflexes were decreased, and there was no bilateral reaction in the

plantar reflexes.

Laboratory tests showed leukocytosis, with a white

blood cell count of 28.3x109/l (normal range,

3.4-9.6x109/l), a low hemoglobin level of 5.8 g/dl

(normal range, 13.6-16.9 g/dl), thrombocytopenia, with a platelet

count of 58x103/l (normal range,

152-324x103/l), and a high ammonia level of 193 µmol/l.

Liver function tests indicated a total bilirubin level of 886

µmol/l, a conjugated bilirubin level of 809 µmol/l (normal range,

0.8-3.0 µmol/l), an alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level of 405 U/l

(normal range, 54-144 U/l), an ALT level of 137 U/l (normal range,

17-45 U/l) and an AST level of 263 U/l (normal range, 8-38 U/l).

Renal function was also elevated, with a blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

level of 50 mmol/l (normal range, 2.1-8.5 mmol/l) and a creatinine

level of 256 µmol/l (normal range, 61.9-114.9 µmol/l). The brain

MRI, taken 8 days post-admission (Fig.

S1), showed bilateral, nearly symmetric cortical swelling, with

FLAIR/T2 high signal intensity and diffusion restriction affecting

the frontal, parietal, and temporal regions while sparing the

peri-rolandic and occipital areas. The patient's clinical condition

deteriorated steadily, and they succumbed to septic shock and

multiorgan failure 2 weeks later.

Case 3

A 36-year-old woman with ulcerative colitis (UC)

underwent a deceased donor liver transplant (split liver) smooth

surgery hepaticojejunostomy for primary sclerosing cholangitis in

Feb 2021 at KFSH-D, and recovered without any complications.

However, on the fifth day after surgery the patient's level of

consciousness began to deteriorate. During a physical examination,

while not sedated, it was noted that the patient had an elevated

temperature of 38.1˚C, generalized jaundice, and a GCS score of 4

out of 15. The patient later experienced multiple generalized

tonic-clonic convulsions, and the EEG showed generalized background

slowing with epileptiform discharges. At that time, laboratory

tests revealed high level of ammonia (512.75 µmol/l), liver enzymes

(total bilirubin, 344.6 µmol/l; conjugated bilirubin, 259 µmol/l;

ALP, 118 U/l; ALT, 1,325 U/l; and AST, 1,856 U/l) and renal

function (BUN, 10.5 mmol/l; and creatinine, 179 µmol/l). The

seizures were controlled using a midazolam infusion at 2 mg/h for 3

days. An MRI of the brain 3 days later showed diffuse symmetrical

cerebral edema with high signal intensity and diffusion

restriction, sparing the bilateral occipital lobes and

peri-rolandic region (Fig. S2).

The patient passed away on the next day.

Case 4

An 18-year-old woman with autoimmune hepatitis was

transferred from Aramco Hospital (Dhahran, Saudi Arabia) to the ICU

at KFSH-D in February 2020. The patient had acute liver failure,

decreased consciousness, and a new left-sided focal unaware

seizure. The seizure was aborted after receiving levetiracetam

loading of 3,000 mg over 10 min and a midazolam infusion of 2 mg/h

over 24 h. The initial computed tomography brain scan (CT) showed

cerebral edema, diffuse sulcal effacement, and crowding of the

foramen magnum. The patient underwent a liver transplant procedure.

Brain MRI 3 days later showed diffuse symmetrical cerebral cortical

abnormalities with high signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging and

FLAIR, affecting the splenium of the corpus callosum, the left

Globus pallidus, bilateral thalamic regions, the posterior limb of

the internal capsule, and the hippocampi. This was associated with

diffusion restriction, but the occipital lobes and peri-rolandic

region were spared (Fig. S3).

After withdrawing the midazolam infusion, the physical examination

showed a GCS score of 4 out of 15, with all brainstem reflexes

intact, generalized hypotonia and hyperreflexia, and unresponsive

plantar reflexes. Laboratory tests revealed an ammonia level of 310

µmol/l and elevated liver enzymes, with an ALT level of 5,075 U/l,

an AST level of 1,914 U/l, and a total bilirubin level of 334

µmol/l.

A follow-up EEG showed a generalized slowing in the

delta range, and no epileptiform discharges were present.

Additionally, a follow-up MRI, conducted 10 days after the initial

scan, showed interval evolution of the intraparenchymal changes

(Fig. S4). The patient passed away

due to septic shock and multiorgan failure after 39 days in the

ICU.

Case 5

A 51-year-old woman with a known case of

hypothyroidism and a history of gastric bypass surgery complicated

by steatohepatitis presented with impaired consciousness and

jaundice. The patient was admitted to KFSH-D in December 2018

through the Emergency Department with acute-on-chronic liver

failure and pulmonary edema that required intubation. The patient's

level of consciousness deteriorated within 3 days. Upon

examination, the patient was unresponsive, with a GCS of 5 out of

15, and preserved brainstem reflexes. Laboratory investigations

revealed a high serum ammonia level of 174 µmol/l, mildly elevated

liver enzymes (AST, 93 U/l; and ALT, 63 U/l), and a total bilirubin

level of 158 µmol/l. The EEG results showed generalized slowing of

the background without epileptiform discharges. A brain MRI scan

performed 10 days after the onset of symptoms showed bilateral

asymmetric cortical swelling and diffusion restriction in the

insula, cingulate gyri, and bilateral hippocampi, with

corresponding T2/FLAIR hyperintensity and T1 hyperintensity sparing

the occipital lobes and peri-rolandic region (Fig. S5). The patient experienced a

prolonged generalized convulsion for 30 min, which was controlled

with levetiracetam in a 3,000-mg intravenous infusion over 15 min,

followed by 750 mg orally twice and lamotrigine at 50 mg twice. The

patient's condition improved as the seizure subsided and the

ammonia level normalized, but residual memory impairment was still

present. A follow-up brain MRI revealed complete resolution of the

cortical and subcortical T2 and FLAIR high signal intensities,

along with marked bilateral symmetrical brain atrophy (Fig. S6). The patient was regularly

followed up by the neurology team and remained seizure-free after

adding phenytoin at 100 mg every 12 h to the treatment, but still

complains of memory impairment.

Discussion

Despite the diverse and complex presentations of the

5 patients in the present study, the clinical courses were

characterized by the interplay of acute hepatic failure

superimposed on preexisting chronic liver disease. This resulted in

a rapid rise in serum ammonia levels, leading to a marked decline

in consciousness and the development of HE. Simultaneously, brain

MRI revealed extensive cortical signal-intensity changes with

associated restricted diffusion. Regardless of the primary

etiology, the patients eventually shared similar MRI brain findings

that showed bilateral symmetrical involvement of the insular cortex

and cingulate gyri on FLAIR and T2-weighted imaging sequences, with

diffusion restriction sparing the peri-rolandic and occipital

areas. These widespread cortical lesions may represent

hyperammonemia-related brain edema (3,8) and

have been reported previously in several case series (8-12).

For example, U-King-Im et al (8) reported the cases of 4 patients with

similar findings, 3 of whom had liver damage due to acute hepatic

failure and sepsis with a background of chronic liver diseases

(8). The extensive cortical brain

MRI abnormalities seen in these patients could be indicative of

other conditions, such as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, limbic

encephalitis, acute hypertension, hyponatremia, or

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (13).

However, none of the patients in the present study exhibited

clinical or laboratory evidence supporting these conditions.

Notably, the peri-rolandic and occipital areas are

usually relatively spared in hyerammonemic encephalopathy (10). A recent report detailed the cases of

3 patients with hyperammonemic encephalopathy stemming from

different causes, including infectious, toxic, and cirrhotic

origins, all of which demonstrated similar findings on MRI

(9). Furthermore, Takanashi et

al (14) described 3 cases of

hyperammonemia encephalopathy secondary to late-onset ornithine

transcarbamylase deficiency, each showing evidence of injury to the

cingulate and insular cortices (14). This later study also indicated that

the peri-rolandic and occipital cortices were spared. The authors

proposed the vulnerability of the cingulate gyrus and insular

cortex due to hyperammonemia-hyper glutaminergic encephalopathy

(14). This unique sparing pattern

is significant, as it can help differentiate hyperammonemic

encephalopathy from other conditions with similar MRI findings.

However, it remains unclear why certain brain areas, such as the

insular cortex or cingulate gyrus, appear especially susceptible to

the toxic effects of ammonia.

The involvement of various brain structures,

including the thalami, basal ganglia, periventricular white matter,

brainstem, and peri-rolandic and occipital cortical regions, has

been inconsistently reported in patients with hyperammonemic

encephalopathy (8,15,16).

In the present cases, in addition to the insular and cingulate

gyri, the thalami were affected in the MRI of patients 1, 3, 4, and

5, possibly due to their chronic liver diseases. However, a

premorbid brain MRI was not available to rule out this

possibility.

In the ICU, the patients experienced a range of

systemic complications, including acute renal failure, seizure, and

sepsis. These issues may have contributed to the MRI changes

observed. However, not every patient faced these complications, yet

they all displayed similar MRI cortical signal abnormalities. The

symmetrical changes in the insular and cingulate gyri suggest a

toxic effect. Additionally, the resemblance of the MRI findings in

the present cases to those reported in the previous literature

(5,8,9,10,12,14),

even in patients without hepatic failure, seizure or

hypoxic-ischemic injury, strongly supports the idea that the brain

MRI changes described are directly linked to hyperammonemia.

Ammonia is produced through protein metabolism in

the gastrointestinal tract, with the liver being the primary site

of ammonia breakdown in the urea cycle. Elevated serum ammonia

levels indicate compromised hepatic function or the presence of a

portosystemic shunt. Ammonia can cross the blood-brain barrier

through diffusion in its unionized form (NH3) and active

transport in its ionized form (NH4+)

(17). Astrocytes utilize ammonia

to generate high concentrations of glutamine (17), rapidly increasing cellular

osmolarity as glutamine accumulates, leading to astrocyte swelling

and heightened intracranial pressure (18). Furthermore, hyperammonemia disrupts

brain energy metabolism, causing an increase in the

lactate-to-pyruvate ratio (17).

Conversely, brain edema is less common in cases of chronic liver

failure, as there is sufficient time for compensatory cellular

adaptation mechanisms to respond to osmotic changes (19).

All patients in the present case series had high

serum levels of ammonia. However, in cases 1 and 4, an association

was observed between serum ammonia levels, deterioration of

consciousness, and cortical MRI changes. Higher ammonia levels

appeared to lead to deeper comas and increased cortical brain MRI

hyperintensities. This association has also been noted in previous

reports (8,20). By contrast, plasma ammonia levels

are often measured in clinical settings to assist in the diagnosis;

these results should be interpreted cautiously, as elevated ammonia

levels can arise from various conditions apart from acute liver

failure, such as the administration of drugs (e.g., sodium

valproate and chemotherapy), infections, hypothyroidism, multiple

myeloma, inborn errors of metabolism, and post-lung or -bone marrow

transplantation (11,12,20-23).

Prolonged and high serum hyperammonemia levels can

lead to significant brain injuries and devastating complications,

such as brain edema and herniation. In the long term, insular and

cingulate atrophy may occur (12,21,23-25).

Therefore, timely recognition and treatment of hyperammonemia are

crucial to avoid these complications. In the present study,

patients 2, 3, and 4 exhibited elevated serum ammonia levels and

sustained more extensive brain injuries, resulting in poor

prognoses. Conversely, patients 1 and 5, who had lower serum

ammonia levels, survived after their plasma ammonia levels

normalized, although patient 5 experienced residual memory

impairment, likely due to prolonged seizure activity and

hyperammonemia encephalopathy. The main limitations of the present

study are its retrospective design and the lack of baseline imaging

and laboratory data before the recent admission, which warrants the

need for future studies with larger cohorts and prospective designs

to perform correlational analyses between blood ammonia levels and

cerebral injury, and to strengthen the understanding of this

association in similar populations.

In conclusion, the current study presented the cases

of 5 adult patients who exhibited typical brain MRI features of

acute hyperammonemic HE. These patients demonstrated symmetrical

signal abnormalities in the insular and cingulate cortices, while

the peri-rolandic and occipital cortices were spared. Early

recognition of these diagnostic features could lead to improved

patient outcomes through proper treatment intervention.

Furthermore, an association was noted between serum ammonia levels

and brain MRI abnormalities, which warrants further investigation

in future studies.

Supplementary Material

MRI brain for case 2. (A) T2-weighted

MRI, (B) FLAIR, (C) DWI and (D) ADC map demonstrating symmetric

cortical swelling with corresponding high T2 and FLAIR signal

intensity involving bilateral insular cortex, frontal lobes,

parietal lobes, temporal lobes and cingulate gyri with

corresponding diffusion restriction. The bilateral occipital lobes

and deep grey matter nuclei are spared. At the level of the vertex,

(E) T2-wieghted image, (F) FLAIR, (G) DWI and (H) ADC map

demonstrating similar symmetric cortical swelling with high T2 and

FLAIR signal intensities involving the frontal and parietal lobes

with corresponding restricted diffusion. The bilateral

peri-Rolandic regions are spared. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging;

FLAIR, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery; DWI, diffusion-weighted

imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient.

MRI brain scan for case 3. (A)

T2-weighted MRI, (B) FLAIR, (C) DWI and (D) ADC map demonstrating

symmetric cortical swelling with high T2 and FLAIR signal

intensities involving the bilateral insular cortex, frontal lobes,

temporal lobes, parietal lobes, cingulate gyri and bilateral

lateral thalami, with corresponding diffusion restriction. The

bilateral occipital lobes are spared. At the level of the vertex,

(E) T2-weighted MRI, (F) FLAIR, (G) DWI and (H) ADC map

demonstrating similar symmetric cortical swelling with high T2 and

FLAIR signal intensities affecting the frontal and parietal lobes,

with corre-sponding restricted diffusion. The bilateral

peri-rolandic regions are spared. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging;

FLAIR, fluid attenuated inversion recovery; DWI, diffusion-weighted

imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient.

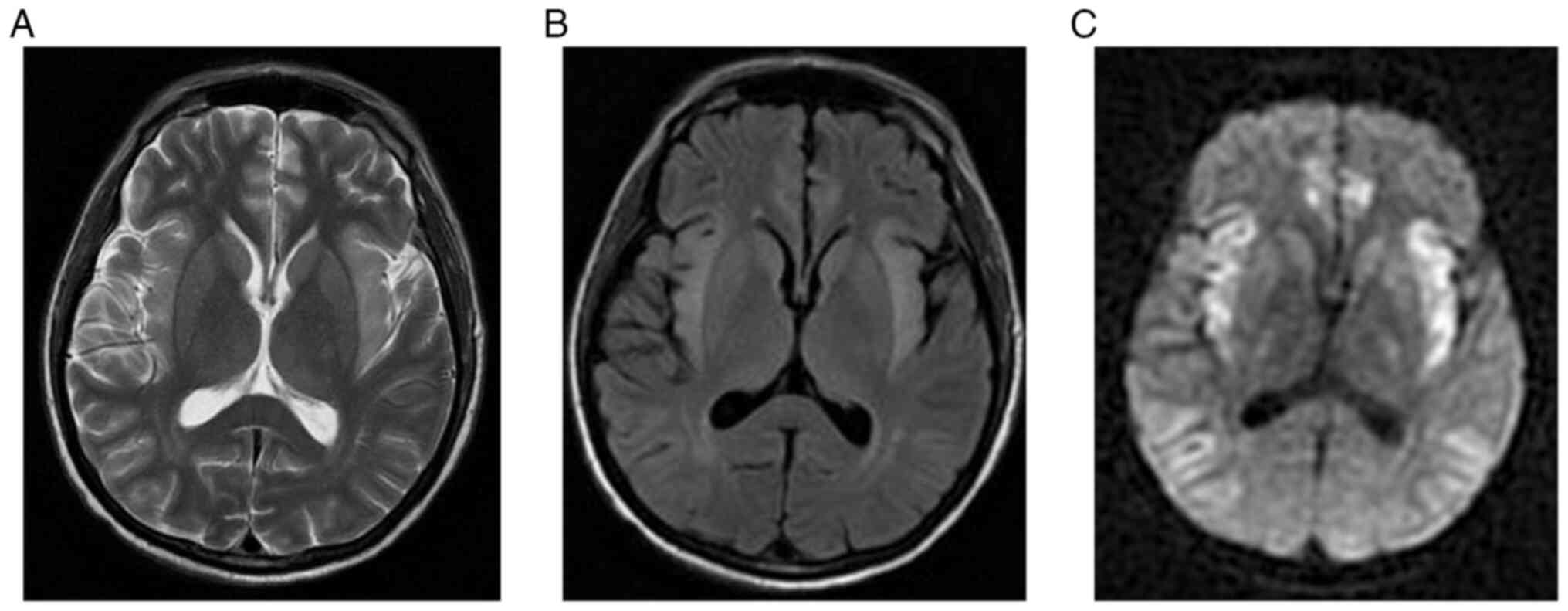

MRI brain scan for case 4. (A)

T2-weighted MRI, (B) FLAIR, (C) DWI and (D) ADC map demonstrating

symmetric cortical swelling with high T2 and FLAIR signal

intensities involving the bilateral insular cortex, frontal lobes,

temporal lobes, parietal lobes and cingulate gyri. The bilateral

occipital lobes are spared. Foci of high T2 and FLAIR signal

intensities are observed in the right anterior thalamus, left

globus pallidus and splenium of the corpus callosum, with

corresponding diffusion restriction, likely representing ischemic

insults. At the level of the vertex, (E) T2-weighted MRI, (F)

FLAIR, (G) DWI and (H) ADC map demonstrating asymmetric cortical

swelling with high T2 and FLAIR signal intensities involving the

frontal and parietal lobes, with corresponding restricted

diffusion. The bilateral peri-rolandic regions are spared. MRI,

magnetic resonance imaging; FLAIR, fluid attenuated inversion

recovery; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion

coefficient.

Follow-up MRI brain scan for case 4

after 10 days. (A) T2-weighted MRI, (B) FLAIR, (C)

diffusion-weighted imaging and (D) apparent diffusion coefficient

map demonstrating interval stability of symmetric cortical

swelling, with persistent high T2 and FLAIR signal intensities

involving the bilateral insular cortex, frontal lobes, temporal

lobes and bilateral cingulate gyri. Regression of diffusion

restriction suggests interval evolution of intraparenchymal changes

associated with acute hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy.

Interval regression of high T2 and FLAIR signal intensities, and

diffusion restriction in the right anterior thalamus, left globus

pallidus and splenium of the corpus callosum, indicate subacute

evolution of the ischemic insults. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging;

FLAIR, fluid attenuated inversion recovery.

MRI brain scan for case 5. (A)

T2-weighted MRI, (B) FLAIR, (C) DWI and (D) ADC map demonstrating

symmetric cortical swelling with corresponding high T2 and FLAIR

signal intensity involving the bilateral insular cortex, frontal

lobes, parietal lobes, temporal lobes and cingulate gyri, with

corresponding diffusion restriction. The bilateral occipital lobes

and deep grey matter nuclei are spared. At the level of the vertex,

(E) T2-weighted MRI, (F) FLAIR, (G) DWI and (H) ADC map

demonstrating similar asymmetric cortical swelling, with high T2

and FLAIR signal intensities involving the frontal and parietal

lobes, with corresponding restricted diffusion. The bilateral

peri-rolandic regions are spared. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging;

FLAIR, fluid attenuated inversion recovery; DWI, diffusion-weighted

imaging; ADC, apparent diffusion coefficient.

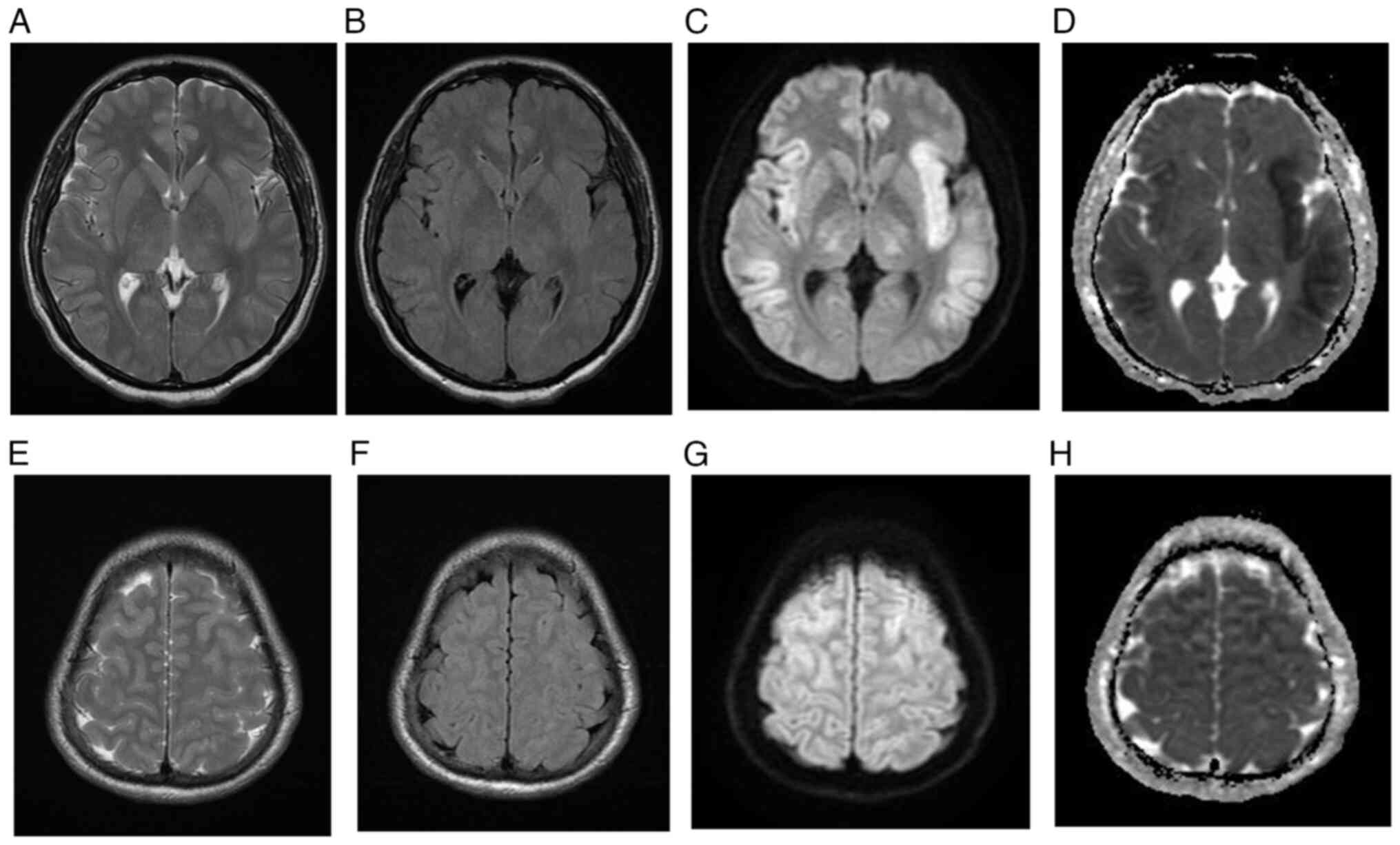

Follow-up MRI brain scan for case 5.

(A) T2-weighted MRI, (B) FLAIR and (C) diffusion-weighted imaging

demonstrating complete resolution of the cortical T2 and FLAIR high

signal intensities, with marked bilateral symmetrical brain

atrophy. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; FLAIR, fluid attenuated

inversion recovery.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The King Salman center For Disability Research funded

this work through Research Group no. KSRG-2024-307.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AB was responsible for the design of the study and

overall project coordination. HA, SO, NA, FA and SM contributed to

data collection and assisted with the literature review and

manuscript drafting. HA and HA provided radiological and clinical

oversight and supported the validation of results. SB structured

and critically revised the manuscript and secured funding. TAH

contributed to the conceptual framework and provided overall

project supervision. AB and TAH confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of

King Fahad Specialist Hospital-Dammam (IRB-Pub-024-01).

Patient consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication was

obtained from all subjects.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Hussain J, Schlachterman A, Kamel A and

Gupte A: Hyperinsulinism hyperammonemia syndrome, a rare clinical

constellation. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep.

4(2324709616632552)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Brusilow SW: Hyperammonemic

encephalopathy. Medicine (Baltimore). 81:240–249. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Atluri DK, Prakash R and Mullen KD:

Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment of hepatic encephalopathy. J

Clin Exp Hepatol. 1:77–86. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Dharel N and Bajaj JS: Definition and

nomenclature of hepatic encephalopathy. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 5

(Suppl 1):S37–S41. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang XD and Zhang LJ: Multimodal MR

imaging in hepatic encephalopathy: State of the art. Metab Brain

Dis. 33:661–671. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Morgan MY: Cerebral magnetic resonance

imaging in patients with chronic liver disease. Metab Brain Dis.

13:273–290. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rosario M, McMahon K and Finelli PF:

Diffusion-weighted imaging in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy.

Neurohospitalist. 3:125–130. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

U-King-Im JM, Yu E, Bartlett E, Soobrah R

and Kucharczyk W: Acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy in adults:

Imaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 32:413–418.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Reis E, Coolen T and Lolli V: MRI findings

in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy: Three cases of different

etiologies: Teaching point: To recognize MRI findings in acute

hyperammonemic encephalopathy. J Belg Soc Radiol.

104(9)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Arnold SM, Els T, Spreer J and Schumacher

M: Acute hepatic encephalopathy with diffuse cortical lesions.

Neuroradiology. 43:551–554. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Lora-Tamayo J, Palom X, Sarrá J, Gasch O,

Isern V, Fernández de Sevilla A and Pujol R: Multiple myeloma and

hyperammonemic encephalopathy: Review of 27 cases. Clin Lymphoma

Myeloma. 8:363–369. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Bindu PS, Sinha S, Taly AB, Christopher R

and Kovoor JME: Cranial MRI in acute hyperammonemic encephalopathy.

Pediatr Neurol. 41:139–142. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Koksel Y, Benson J, Huang H, Gencturk M

and McKinney AM: Review of diffuse cortical injury on

diffusion-weighted imaging in acutely encephalopathic patients with

an acronym: ‘CRUMPLED’. Eur J Radiol Open. 5:194–201.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Takanashi J, Barkovich AJ, Cheng SF,

Weisiger K, Zlatunich CO, Mudge C, Rosenthal P, Tuchman M and

Packman S: Brain MR imaging in neonatal hyperammonemic

encephalopathy resulting from proximal urea cycle disorders. AJNR

Am J Neuroradiol. 24:1184–1187. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

McKinney AM, Lohman BD, Sarikaya B,

Uhlmann E, Spanbauer J, Singewald T and Brace JR: Acute hepatic

encephalopathy: Diffusion-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion

recovery findings, and correlation with plasma ammonia level and

clinical outcome. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 31:1471–1479.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

McPhail MJW, Patel NR and Taylor-Robinson

SD: Brain imaging and hepatic encephalopathy. Clin Liver Dis.

16:57–72. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Ott P and Vilstrup H: Cerebral effects of

ammonia in liver disease: Current hypotheses. Metab Brain Dis.

29:901–911. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hertz L and Kala G: Energy metabolism in

brain cells: Effects of elevated ammonia concentrations. Metab

Brain Dis. 22:199–218. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Rovira A, Alonso J and Córdoba J: MR

imaging findings in hepatic encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol.

29:1612–1621. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wang V and Saab S: Ammonia levels and the

severity of hepatic encephalopathy. Am J Med. 114:237–238.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Clay AS and Hainline BE: Hyperammonemia in

the ICU. Chest. 132:1368–1378. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Lichtenstein GR, Yang YX, Nunes FA, Lewis

JD, Tuchman M, Tino G, Kaiser LR, Palevsky HI, Kotloff RM, Furth

EE, et al: Fatal hyperammonemia after orthotopic lung

transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 132:283–287. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Chou HF, Yang RC, Chen CY and Jong YJ:

Valproate-induced hyperammonemic encephalopathy. Pediatr Neonatol.

49:201–204. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Nott L, Price TJ, Pittman K, Patterson K

and Fletcher J: Hyperammonemia encephalopathy: An important cause

of neurological deterioration following chemotherapy. Leuk

Lymphoma. 48:1702–1711. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Liu J, Lkhagva E, Chung HJ, Kim HJ and

Hong ST: The pharmabiotic approach to treat hyperammonemia.

Nutrients. 10(140)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|