1. Introduction

Pathological calcification, also known as ectopic

calcification, refers to the deposition of mineralized complexes in

soft tissues outside of bones and teeth under physiological

conditions. This condition can result from genetic factors or

chronic diseases acquired later in life (1). Research indicates that pathological

calcification shares similarities with physiological calcification

but occurs due to an imbalance between inhibitory and promoting

factors, leading to abnormal mineralization in soft tissues

(2). Key mechanisms include the

induction of bone formation, differentiation of vascular smooth

muscle cells into osteoblastic phenotypes, oxidative stress,

apoptosis, mitochondrial dysfunction, calcium-phosphorus imbalance,

and decreased levels of calcification inhibitors (3). Despite ongoing research, the molecular

mechanisms underlying pathological calcification remain poorly

understood, and effective treatments have yet to be developed.

Further investigation into these mechanisms is expected to reveal

more promising therapeutic targets.

In recent years, in-depth studies on nanobacteria

(NB) have revealed their ability to aggregate calcium and

phosphorus from the surrounding environment within the body,

forming nucleation centers. These findings highlight the

significant role of NB in the pathogenesis of pathological

calcification diseases (4).

Initially identified by Finnish scientists Kajander and Ciftçioglu

(5) as contaminants in cell

cultures, NB exhibit diameters ranging from 50 to 500 nm, with a

peak particle size of ~130 nm. Their outer layer is covered with a

dense, needle-like apatite mineralized shell, and their interior

contains cavities and inclusions. The main protein component is

fetuin-A, and they are Gram-negative. Their proliferation rate is

~10,000 times slower than that of bacteria. They can withstand

temperatures as high as 100˚C and harsh chemical conditions, while

most other bacteria cannot survive in such extreme environments,

and resistance to most antibiotics (4,6-9).

Tetracycline is one of the few drugs that can effectively reduce

the damage of NB (7). However,

debate persists regarding whether NB represent the smallest known

replicating life forms or are merely mineral-protein complexes

unrelated to bacteria. Recent findings indicate that NB lack

definitive nucleic acid sequences, leading researchers to prefer

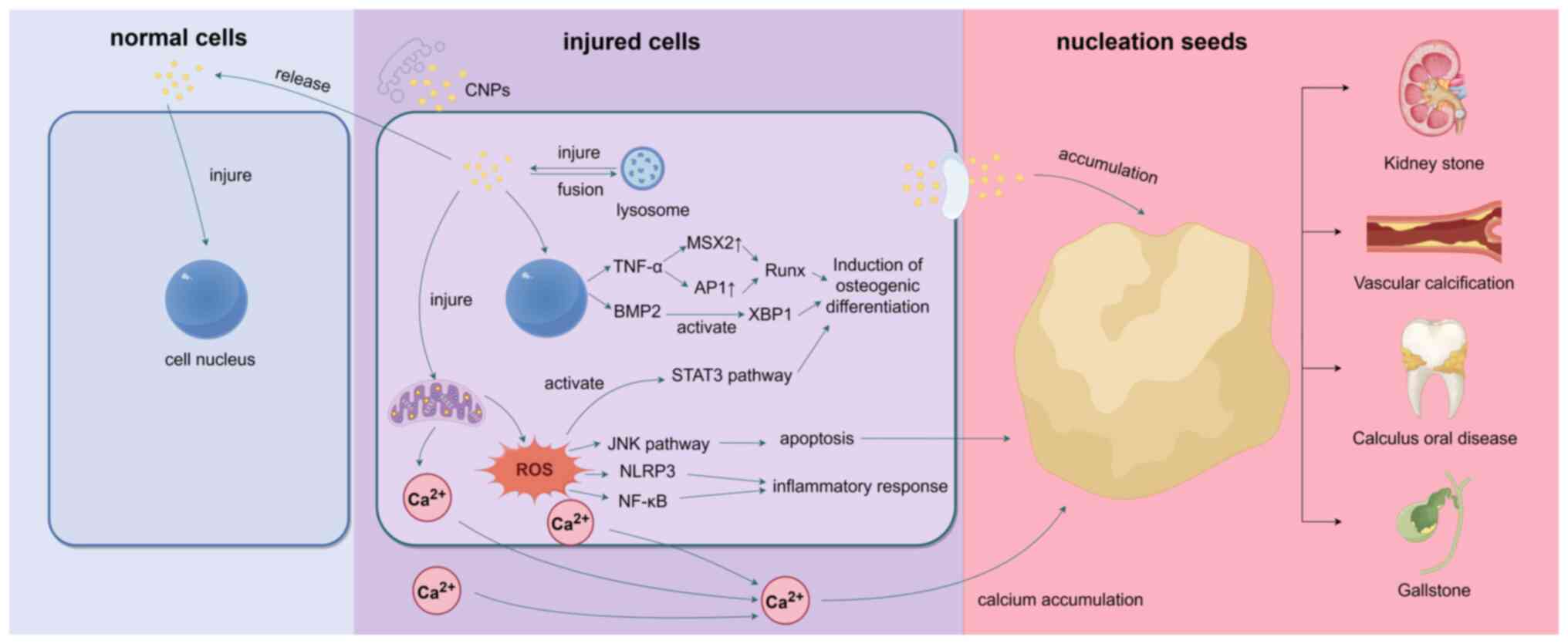

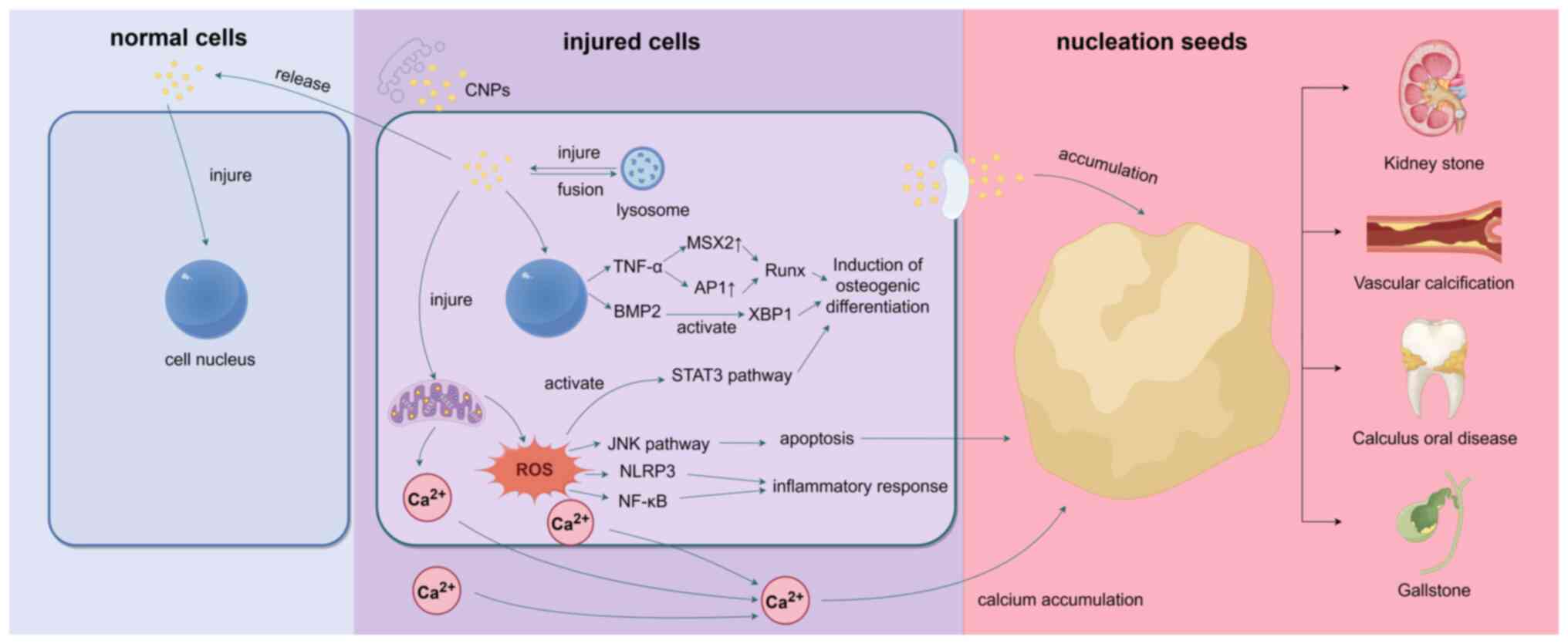

the term ‘calcified nanoparticles’ (CNPs) (10). CNPs can accumulate calcium and

phosphorus in their surrounding environment and nucleate within the

human body, especially after being internalized by cells, where

they exert a direct toxic effect. CNPs can inflict damage upon cell

membranes, mitochondria, lysosomes, and other cellular structures

and even produce a large amount of reactive oxygen species (ROS),

ultimately leading to cell necrosis and apoptosis. This process

contributes to the formation of larger nucleation centers,

resulting in the aggregation of calcium and phosphorus into

calcified cores (11) (Fig. 1). Research has established a link

between CNPs and ectopic calcification diseases and CNPs have been

detected in various conditions involving ectopic calcification,

including kidney stones, bladder stones, dental pulp stones,

salivary gland stones, cholecystolithiasis, and testicular

microstones; calcification in hemodialysis patients,

atherosclerosis, scleroderma (systemic sclerosis), and several

malignant tumors (7). Furthermore,

fetuin-A, by binding to CNPs, enhances their solubility in

circulation, thereby inhibiting calcification (12). Consequently, some researchers

propose that increasing circulating fetuin-A levels may represent a

promising therapeutic approach for pathological calcification

diseases (13). Given these

findings, the interaction between fetuin-A and NB, as well as the

underlying mechanisms in calcification diseases, has emerged as a

focal point of current research.

| Figure 1After CNPs enter cells through

endocytosis, they induce the expression of TNF-α and BMP2.

Specifically, TNF-α enhances RUNX2 expression by regulating the

transcription factors MSX2 and AP-1, while BMP-2 activates the XBP1

signaling pathway, both contributing to osteogenic differentiation.

Additionally, CNPs stimulate ROS production, which activates STAT3

and other pathways, further promoting osteogenic differentiation.

On the other hand, CNPs can disrupt cell membrane stability,

alkalize lysosomes, and stimulate mitochondria to produce excessive

ROS, leading to damage in cellular structures such as the cell

membrane, mitochondria, and lysosomes. The generated ROS not only

activate the NLRP3 inflammasome and initiate the NF-κB signaling

pathway, causing inflammatory damage, but also trigger autophagy

and apoptosis via the ROS-JNK signaling pathway. During apoptosis,

CNPs facilitate the aggregation of Ca2+ from the

cytoplasm, mitochondria, and extracellular matrix, forming a

calcification core. Apoptotic cells release matrix vesicles

containing CNPs, which damage surrounding cells, expand the

inflammatory response, and promote continuous expansion of the

calcification core, ultimately resulting in pathological

calcification. CNPs, calcified nanoparticles; RUNX2, dwarf-related

transcription factor 2; MSX2, homeobox transcription factor muscle

segment homeobox 2; AP-1, activator protein 1; XBP1, X-box binding

protein 1; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of transcription

3; ROS, reactive oxygen species; NLRP3, NLR family pyrin domain

containing 3; BMP2, bone morphogenic protein 2. |

The nucleation of CNPs continues to gather calcium

and phosphorus from the surrounding environment, leading to the

formation of hydroxyapatite and growth of cavity-filling stones.

These stones can cause tissue damage through mechanical blockage,

resulting in colic and, in severe cases, organ failure. The high

concentration of minerals in the excretory fluids of the body

promotes the nucleation of CNPs, making the bile duct and

genitourinary tract susceptible to stone formation (14). In the urinary tract, crystallization

usually begins in the renal tubules. The gradual concentration of

glomerular filtrate and the active secretion of calcium, uric acid,

oxalate, phosphate, or drug metabolites lead to mineral

supersaturation in the renal tubules. Subsequently, stones may

develop in the larger renal pelvis, where calcified Randall plaques

on the renal papilla are formed (15). In the bile duct, bile is rich in

electrolytes, bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids, and

conjugated bilirubin, especially in the gallbladder. The

concentration and storage of bile promote stone formation (14). In addition, CNPs can cause vascular

calcification in circulation, which is common in the elderly and

patients with uremia. This intermediate-level calcification

decreases vascular compliance and increases the risk of

cardiovascular disease (16). In

the oral cavity, CNPs contribute to calculus oral diseases by

alkalizing the environment, mediating inflammatory responses, and

promoting dental plaque mineralization (10).

The aim of the present review was to explore the

properties of CNPs and their mechanisms in pathological

calcification diseases such as kidney stones, vascular

calcification, calculus oral diseases and gallstones, offering new

insights for treating these conditions.

2. Mechanism of CNPs in calcified

diseases

Kidney stones

Kidney stones are caused by the abnormal

accumulation of crystalline substances, including calcium, oxalic

acid, uric acid, and cystine in the kidney. Among these, calcium

oxalate (CaOx) crystallization is the most prevalent, making kidney

stones a common and frequently occurring disease of the urinary

system. Approximately 10% of the global population is affected by

kidney stones, with this number continuing to rise (17). However, the mechanism of kidney

stone formation is not completely clear. Currently, numerous

theories attempt to explain the formation of renal calculi. These

theories include renal calcification spots, supersaturated

crystallization, stone matrix, crystal inhibitors, and

heterogeneous nucleation. Among them, the theory of calcified

plaques in the renal papilla (Randall's plaque) is a prominent

explanation for renal stone formation. Alexander Randall first

proposed the Randall plaque theory in 1937. Studies have shown that

renal CaOx stones originate from calcified plaques in the renal

papilla, with calcified plaques being almost universally present in

the renal papillary tips of patients with CaOx stones (18). In addition, in-depth studies of

renal papillary calcification plaques have revealed the presence of

CNPs through transmission electron microscopy observations of renal

sections and cultures of renal papillary calcification plaques

(19,20). This finding has established a

correlation between CNPs and Randall's plaque.

CNPs in the bloodstream can accumulate in the kidney

by passing through the glomerular filtration membrane, thereby

inflicting damage on renal tubular epithelial cells. In the blood,

CNPs exist as troponin granules with a diameter ranging from 30 to

100 nm. The intercellular gaps between capillary endothelial cells,

the main pore barrier of the glomerular filtration membrane,

measure between 50 and 100 nm. After intravenous injection of

99mTc-labeled CNPs into rabbits, CNPs can be detected in

the kidneys and urine (21). By

contrast, CNPs entering the urine can adhere to renal tubular

epithelial (HK-2) cells, leading to damage during urine excretion.

A study involving the co-culture of CNPs with fluorescence-labeled

HK-2 cells has observed that CNPs can enter HK-2 cells via

endocytosis mediated by membrane invagination and accumulate around

the nucleus. This accumulation results in a decrease in plasma

membrane cholesterol, compromising the stability of the cell

membrane and making cells susceptible to mechanical damage

(22). After entering HK-2 cells,

CNPs induce several adverse effects. First, CNP phagocytosis by

HK-2 cells can cause mitochondrial swelling and vacuolation around

CNPs, a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential, and an

overload of intracellular oxygen free radicals (such as ROS). The

latter can in turn affect the stability of the mitochondrial

membrane, aggravate mitochondrial damage, and lead to persistent

overload of ROS. Internalized CNPs not only increase the activity

of NADPH oxidase but also stimulate cells to produce a large amount

of ROS (4). Second, CNPs

internalized into cells can bind to lysosomes and lead to lysosome

alkalinization, resulting in swelling of lysosomes and inhibition

of lysosomal hydrolase activity. Alkalized lysosomes can block

autophagy flux and decrease the ability of cells to digest damaged

proteins and organelles through autophagy, especially the digestion

of damaged mitochondria (22).

In addition, a large amount of ROS can induce

inflammation in renal tubular epithelial cells. On the one hand, a

large amount of ROS can activate JNK through various pathways (such

as the apoptotic signal-regulating kinase 1 pathway and mixed

lineage kinase 3 pathway), leading to autophagy, apoptosis, and

even necrosis, resulting in local inflammation (23-26).

On the other hand, ROS is the key component in activating NLR

family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasomes. ROS can

activate NLRP3 inflammasomes through multiple mechanisms, promoting

the release of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and

IL-18(27). Moreover, ROS can

stimulate the secretion of various cytokines by initiating the

nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) signaling pathway, causing inflammatory

damage to renal tubular epithelial cells and renal tissue (28,29).

The inflammatory injury to renal tubular epithelial

cells may promote the formation of Randall plaques. Randall plaques

originate from the thin ring basement membrane of Henle (30). On the one hand, CNPs entering renal

tubular cells may reach the basement membrane by re-exocytosis or

colonize it by inducing autophagy, apoptosis, and necrosis. During

this process, CNPs release a large amount of calcium and phosphorus

stored within renal tubular epithelial cells, resulting in local

calcium and phosphorus supersaturation in the renal papilla.

Simultaneously, inflammatory lesions further strengthen the

deposition of hydroxyapatite, creating conditions for the formation

of calcified plaques in the renal papilla. Furthermore,

accumulating evidence indicates that extracellular vesicles (EVs)

play a critical role in the pathogenesis of pathological

calcification. Based on this, it is hypothesized that CNP-infected

cells may facilitate the formation of calcification cores by

releasing EVs enriched with CNPs into the basement membrane

(31).

Colonized CNPs in the basement membrane play a role

in biomineralization, aggregating apoptotic bodies and necrotic

cells as the core of mineralization, gradually expanding into

calcifications and promoting the formation of Randall plaques

(32). In addition, the

inflammatory injury to HK2 cells promotes calcium crystal adhesion

to the injured cells. Tamm-Horsfall Protein (THP) increases, acting

as an adhesion protein that facilitates the accumulation and growth

of calcium ions, oxalic acid, and phosphate in urine. When THP

polymerizes into macromolecular forms, it can inhibit or weaken the

inhibition of calcium crystal aggregation in urine. Moreover, THP

molecules exhibit weak binding ability to water molecules and poor

molecular rigidity. Particles such as calcium salt crystals in

urine attach easily, thus promoting stone formation (33).

ROS can upregulate the expression of hyaluronic

acid, osteopontin (OPN), and CD44 through the p38MAPK pathway,

alter the HK-2 cell adhesion to CaOx crystals and stimulate the

formation of CaOx stones. Stimulated by calcified crystals, renal

cells produce various inflammatory factors, which induce monocytes

or macrophages to migrate to sites of stone crystal deposition via

pinocytosis. Phagocytosis of stone crystals by macrophages induces

the production of inflammatory factors, including TNF-α, IL-6 and

IL-1β, which maintain and aggravate the inflammatory response,

causing severe damage to the kidney and promoting the deposition of

stone crystals (34,35).

In summary, CNPs cause severe inflammatory damage to

the kidneys by damaging HK-2 cells and inducing local inflammatory

responses. This inflammatory damage promotes the deposition of

stone crystals, forming a positive feedback loop that enhances the

formation of Randall spots.

Vascular calcification

Ectopic calcification in the cardiovascular system

is a strong predictor of cardiovascular disease morbidity and

mortality. This pathophysiological process entails the deposition

of minerals, mainly hydroxyapatite calcium apatite crystals, within

the intima and media of vascular walls and heart valve leaflets,

with calciprotein particles (CPPs) playing an important role. CPPs

are mineral-protein complexes formed by the combination of CNPs and

circulating proteins, dispersed in the blood as colloids (36). Circulating Gla-rich protein (GRP),

matrix Gla protein (MGP) and fetuin-A are the main proteins that

form CPPs. Among them, the most effective binding protein is

fetuin-A. MGP and GRP contain negatively charged γ-carboxylated

glutamic acid residues (37), which

can bind Ca2+ and calcium-containing compounds (38). By contrast, fetuin-A forms CPPs

through negatively charged β-fold binding to calcium phosphate in

the N-terminal cysteine protease inhibitor D1(39).

Under physiological conditions, initially formed

primary CPPs (CPPI) are usually harmless and contribute to the

clearance of calcium and phosphate, protecting the body from

extraosseous calcification (40).

These CPPI are cleared by macrophages, especially Kupffer cells in

the liver (41). However, under

pathological conditions, especially in patients with diabetes and

chronic kidney disease, the decrease of renal excretion of calcium

and phosphate leads to their accumulation in the body and a

relative decrease in fetuin-A. Consequently, CPPI undergo

rearrangement from a spherical structure ~75-nm in diameter to

larger secondary CPPs (CPPII), measuring ~120 nm in diameter. These

CPPII are denser, insoluble in serum and exhibit a needle-like

structure (42).

Research has demonstrated a close association

between the formation of CPPII and vascular calcification. CPPII

can induce vascular smooth muscle cell calcification and macrophage

secretion of TNF-α in vitro, but CPPI cannot. Calcification

of vascular smooth muscle cells has also been proven to be the

result of cellular uptake of CPPII, which can be detected in

calcified vascular smooth muscle cells (43). In addition, CPPs can induce

macrophages to secrete IL-1β (44).

Compared with CPPI, CPPII exhibit a more obvious pro-inflammatory

effect, which may be related to the content of crystalline

hydroxyapatite (45).

Vascular calcification is the result of two main

types: Intimal and medial calcification. Intimal calcification is

related to inflammation and is the main driving factor, whereas

media calcification is mostly related to mineral disorders

(46). Intimal calcification

results from the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells during

atherosclerosis, whereas medial calcification results from the

transdifferentiation of medial vascular smooth muscle cells

(47). CPPs play an important role

in these processes.

Endothelial cells form the intima of blood vessels,

the first cell type to interact with circulating CPPs.

Internalization of CPPs by endothelial cells triggers lysosome and

cytoplasmic calcium influx, resulting in intracellular calcium

overload (48). This

internalization induces significant physiological disorders in

mitochondria and lysosomes, including oxidative stress, vacuolar

acidification, accelerated protein degradation, and increased

permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane. In addition, the

incubation of intact endothelial cells with CPP-treated endothelial

cells in conditioned medium results in the release of

pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as upregulation of vascular cell

adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1,

increased release of IL-6, IL-8, and monocyte chemoattractant

protein-1, ultimately triggering endothelial cell apoptosis

(49).

CPPII also affect endothelial cell function by

modulating the bioavailability and metabolism of nitric oxide (NO)

(50). Endothelial-derived NO plays

an important role in balancing and regulating vascular dilation and

contraction mediated by vascular smooth muscle cells (51). Endothelial nitric oxide synthase

(eNOS) is the principal enzyme responsible for NO production in

endothelial cells (52,53). Research has demonstrated that CPPII

can induce the dysfunction of eNOS, reducing NO production and

bioavailability, thereby impairing endothelial function. This

dysfunction affects the vasomotor regulation of vascular smooth

muscle cells and eventually leads to hypertension (50). Additionally, eNOS-derived NO is an

important antioxidant, which can scavenge a variety of formed free

radicals (54). The inhibition of

NO production aggravates intracellular oxidative stress and

accelerates cell apoptosis.

Media calcification is the main mechanism of

vascular calcification. Vascular smooth muscle cells internalizing

CPPs can increase intracellular calcium binding and induce their

differentiation into osteoblasts through various mechanisms. First,

CPPs induce vascular smooth muscle cells to express and secrete

TNF-α (43), enhancing the

expression of dwarf-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) through

the homeobox transcription factor muscle segment homeobox 2 (MSX2)

(55) and activator protein 1

(AP-1) (56), thus triggering

osteogenic dedifferentiation. Second, CPPs stimulate vascular

smooth muscle cells to express and secrete bone morphogenic protein

2(57), which can induce osteoblast

dedifferentiation by increasing phosphate transport (58), resulting in endoplasmic reticulum

stress and activation of osteogenic transcription factor X-box

binding protein 1 (XBP1) (59).

Third, CPPs induce oxidative stress in vascular smooth muscle cells

(43), activating downstream

signaling cascades (including Akt, p38MAPK and NF-κB), which

promotes the transcriptional activation of osteochondral

differentiation (60-63).

Alternatively, CPPs promote the secretion of IL-6 from endothelial

cells (64), which may drive the

osteochondrogenic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells

in a signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

(STAT3)-dependent manner (65). The

activation of osteochondral transcription eventually leads to a

decrease in the expression of contractile proteins (for example

α-smooth muscle actin, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, smooth

muscle protein, and calmodulin) and an increase in the expression

of osteogenic markers (such as OPN, osteocalcin, alkaline

phosphatase, and collagen) (66).

The ossification of vascular smooth muscle cells aggravates the

damage of vascular homeostasis, promotes the formation of

atherosclerotic microenvironment, and exacerbates vascular

sclerosis. In addition, transformed vascular smooth muscle cells

can release EVs containing CPPs. These EVs can form the core of

vascular calcification together with apoptotic vascular smooth

muscle cells (67).

When CPPII induce endothelial cell dysfunction

through various pathways, endothelial permeability to low-density

lipoprotein is increased, causing cholesterol-rich particles to

accumulate in the subendothelial layer. Eventually, these particles

form unstable arterial plaques, and local inflammatory stimuli

further lead to plaque rupture, incorporating them into the

calcified core. In addition, CPPII induce apoptosis of vascular

smooth muscle cells and macrophages, resulting in the formation of

apoptotic bodies and necrotic cell fragments. These entities serve

as nucleation sites within ruptured plaques, initiating

microcalcification in injured sites, resulting in calcium phosphate

crystal deposition (68).

Furthermore, ossified vascular smooth muscle cells and macrophages

release EVs containing CPPs, which promote the deposition of

calcium phosphate crystals, which gradually crystallize to form

hydroxyapatite crystals. Ossified smooth muscle cells also regulate

mineralization by secreting osteogenic proteins. Finally,

hydroxyapatite crystals continue to accumulate on the calcified

core, contributing to vascular calcification.

Calculus oral disease

Calculus oral diseases include dental calculi,

dental pulp stones, and salivary gland stones. CNPs may play an

important role in these diseases due to their unique

biomineralization properties. Some scholars have proposed that CNPs

may originate from the atmosphere and can be transmitted through

the air, causing calculus oral diseases (69). Kao et al (70) observed CNPs through sampling and

imaging of salivary gland stones, whereas Zeng et al

(71) observed and cultured CNPs

from dental pulp stones. These studies have shown a large number of

CNPs in the oral cavity, which may lead to the formation of oral

calculi.

CNPs may induce calcification by damaging cells.

Through co-culture experiments of CNPs and periodontal epithelial

cells, Zhang et al (72)

found that CNPs can internalize into these cells, leading to

vacuolization of the periodontal epithelial cells. Electron

microscopy shows CNPs and calcification within vacuoles, along with

calcium deposition outside the cell membrane, which eventually

leads to apoptosis. Moreover, CNPs can use calcium and phosphorus

in periodontal crevicular fluid to form inorganic precipitates

in vivo, which are then deposited on the tooth surface as a

biomineralization centers to form dental calculus (72). In a co-culture model of human dental

pulp cells with CNPs, Yang et al (73) found that CNPs can lead to

vacuolation and mitochondrial swelling of dental pulp cells,

ultimately leading to nuclear calcification and cell necrosis.

Sakai et al (74) found that

the hydroxyapatite shell of CNPs can induce the expression of IL-8

in human gingival epithelial cells through the NF-κB signaling

pathway, resulting in inflammatory reactions that damage cells.

Furthermore, CNPs can increase pH during mineralization, which is

beneficial to the mineralization of dental plaque and the formation

of stones in the neutral and alkaline oral environment (75).

Therefore, when CNPs damage human gingival

epithelial cells or dental pulp cells, they induce inflammatory

responses by aggregating calcium and phosphate ions both intra- and

extracellularly and interacting with dental plaque, thereby forming

an initial calcified core. As the inflammatory response

progressively intensifies, the calcified core gradually enlarges,

ultimately leading to the development of calculus-related oral

diseases.

Gallstones

Cholecystolithiasis, a prevalent digestive system

disorder, mainly involves cholesterol stones or cholesterol-based

mixed stones and melanin stones. The cause of gallstones is

extremely complex, with various factors playing a role. Any factor

influencing the ratio of cholesterol to cholecystocholic acid

phospholipid concentration and cholestasis can contribute to

gallstone formation. Bacterial infection plays an important role in

the formation and progression of gallstones (76). CNPs can be found in the bile and

gallbladder mucosa of patients with gallstones (77). Additionally, animal models of

cholecystolithiasis have been successfully established by injecting

CNPs into the gallbladders of rabbits (78).

CNPs may interact with gallbladder bacteria to

promote stone formation. Research has shown the presence of living

bacteria in gallstones (79).

Culturing gallstone samples from patients with cholecystolithiasis

has revealed a high coinfection rate of CNPs and Escherichia

coli (E. coli) in gallstones, suggesting their

involvement in the formation of gallstones. Professor Kajander

reported that when E. coli and CNPs are mixed,

calcium-stained mineralized particles both inside and outside E.

coli are composed of CNPs (80). This finding implies that CNPs can

cause biological calcification of E. coli by directly

attaching to or invading the bacteria. In addition, the number of

calcium-stained positive particles found in the mixed culture of

CNPs and E. coli is significantly higher than that in

cultures of CNPs alone. Therefore, the existence of E. coli

provides a favorable adhesion matrix and microenvironment for CNPs,

promoting their reproduction and mineralization (78).

At the same time, CNPs can inflict damage on

gallbladder mucosal cells. Research has revealed that after the

co-culture of CNPs with human gallbladder epithelial cells, the

microvilli on the surface of gallbladder epithelial cells decrease

or even disappear, cytoplasmic endocrine granules significantly

decrease, and mitochondria swell and vacuolate (79). Over time, cell necrosis ensues,

accompanied by an increase in the mRNA levels of IL-6 and IL-1β,

indicating the onset of an inflammatory reaction (79). Liang et al (81) found that CNPs can stimulate a

decrease in the Bcl-2/Bax ratio and subsequently upregulate the

expression of cytochrome c and activated cysteine protease

(cleaved caspase-9) in gallbladder epithelial cells following

co-culture with CNPs. This finding suggests that CNPs can induce

apoptosis of gallbladder epithelial cells through the mitochondrial

pathway (81).

Therefore, during gallstone formation, the

interaction between CNPs and gallbladder bacteria may form a

calcification center. Furthermore, the injury of gallbladder

mucosal cells and the production of ROS to mediate inflammatory

reaction aggravate the damage of gallbladder mucosal cells and the

disorder of bile acid metabolism and promote the production of

cholesterol stones.

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, pathological calcification diseases

are a prevalent issue, and their diagnosis and treatment present

significant challenges. As research on CNPs continues to advance,

it is evident that CNPs plays a crucial role in various

pathological calcification diseases. In-depth investigation of CNPs

can further elucidate the mechanisms underlying pathological

calcification, which holds substantial scientific importance. The

present review provides a detailed examination of the primary

mechanisms by which CNPs contribute to four common types of

pathological calcification diseases. These mechanisms facilitate

the formation of an initial calcification core by CNPs, which

progressively expands and ultimately results in localized

calcification or stone formation. During this process, strategies

such as increasing the levels of circulating calcification

inhibitors, inhibiting cellular osteogenic differentiation, and

mitigating local inflammatory responses may offer new avenues for

the prevention and treatment of pathological calcification.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present review was supported by the Research of

Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (grant no. 2023GXNSFAA026142),

and The Outstanding Reserve Talent Fund of the Second Affiliated

Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (grant no. hbrc202101).

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

JW and SL conceived and designed the article. SL and

BB analysed the relevant literature. SL wrote the manuscript. JW

and SL made revisions to the manuscript. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript. Data authentication is not

applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Boraldi F, Lofaro FD and Quaglino D:

Apoptosis in the extraosseous calcification process. Cells.

10(131)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kirsch T: Determinants of pathological

mineralization. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 18:174–180. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Snijders BMG, Peters MJL and Koek HL:

Ectopic calcification: What do we know and what is the way forward?

J Clin Med. 12(3687)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wu J, Tao Z, Deng Y, Liu Q, Liu Y, Guan X

and Wang X: Calcifying nanoparticles induce cytotoxicity mediated

by ROS-JNK signaling pathways. Urolithiasis. 47:125–135.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kajander EO and Ciftçioglu N:

Nanobacteria: An alternative mechanism for pathogenic intra- and

extracellular calcification and stone formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci

USA. 95:8274–8279. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhu ML, Wang JJ, Pan WN, Liu SR and Zhu

YD: Significance of detection of nanobacteria in bile and

gallstones. Chin J Nosocomiol. 29:3279–3283. 2019.

|

|

7

|

Zhang Y, Zhu R, Liu D, Gong M, Hu W, Yi Q

and Zhang J: Tetracycline attenuates calcifying

nanoparticles-induced renal epithelial injury through suppression

of inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in rat models.

Transl Androl Urol. 8:619–630. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Wu JH, Deng YL, Liu Q, Yu JC, Liu YL, He

ZQ and Guan XF: Induction of apoptosis and autophagy by calcifying

nanoparticles in human bladder cancer cells. Tumour Biol.

39(1010428317707688)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Erdemir F, Karabulut A, Ozveren B and

Kocagoz T: How much do we know about nanobacteria? Ecotoxicol

Environ Saf. 288(117415)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Wang S, Yang L, Bai G, Gu Y, Fan Q, Guan

X, Yuan J and Liu J: A preliminary study on calcifying

nanoparticles in dental plaque: Isolation, characterization, and

potential mineralization mechanism. Clin Exp Dent Res.

10(e885)2024.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Liu Y, Sun Y, Kang J, He Z, Liu Q, Wu J,

Li D, Wang X, Tao Z, Guan X, et al: Role of ROS-induced NLRP3

inflammasome activation in the formation of calcium oxalate

nephrolithiasis. Front Immunol. 13(818625)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Jahnen-Dechent W, Heiss A, Schäfer C and

Ketteler M: Fetuin-A regulation of calcified matrix metabolism.

Circ Res. 108:1494–1509. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Jahnen-Dechent W, Schäfer C, Ketteler M

and McKee MD: Mineral chaperones: A role for fetuin-A and

osteopontin in the inhibition and regression of pathologic

calcification. J Mol Med (Berl). 86:379–389. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Mulay SR and Anders HJ: Crystallopathies.

N Engl J Med. 374:2465–2476. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Leaf DE: Calcium kidney stones. N Engl J

Med. 363:2470–2471. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Hutcheson JD, Goettsch C, Rogers MA and

Aikawa E: Revisiting cardiovascular calcification: A multifaceted

disease requiring a multidisciplinary approach. Semin Cell Dev

Biol. 46:68–77. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Mager R and Neisius A: Current concepts on

the pathogenesis of urinary stones. Urologe A. 58:1272–1280.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

18

|

Randall A: The origin and growth of renal

calculi. Ann Surg. 105:1009–1027. 1937.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Wong TY, Wu CY, Martel J, Lin CW, Hsu FY,

Ojcius DM, Lin PY and Young JD: Detection and characterization of

mineralo-organic nanoparticles in human kidneys. Sci Rep.

5(15272)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Ciftçioğlu N, Vejdani K, Lee O, Mathew G,

Aho KM, Kajander EO, McKay DS, Jones JA and Stoller ML: Association

between Randall's plaque and calcifying nanoparticles. Int J

Nanomedicine. 3:105–115. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Akerman KK, Kuikka JT, Ciftcioglu N,

Parkkinen J, Bergstroem KA, Kuronen I and Kajander EO:

Radiolabeling and in vivo distribution of nanobacteria in rabbits.

Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 3111:436–442. 1997.

|

|

22

|

Kunishige R, Mizoguchi M, Tsubouchi A,

Hanaoka K, Miura Y, Kurosu H, Urano Y, Kuro-O M and Murata M:

Calciprotein particle-induced cytotoxicity via lysosomal

dysfunction and altered cholesterol distribution in renal

epithelial HK-2 cells. Sci Rep. 10(20125)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ray PD, Huang BW and Tsuji Y: Reactive

oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular

signaling. Cell Signal. 24:981–990. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Chen K, Vita JA, Berk BC and Keaney JF Jr:

c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation by hydrogen peroxide in

endothelial cells involves SRC-dependent epidermal growth factor

receptor transactivation. J Biol Chem. 276:16045–16050.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Thévenin AF, Zony CL, Bahnson BJ and

Colman RF: GST pi modulates JNK activity through a direct

interaction with JNK substrate, ATF2. Protein Sci. 20:834–848.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Van den B MCW, Van Gogh IJA, Smits AMM,

van Triest M, Dansen TB, Visscher M, Polderman PE, Vliem MJ,

Rehmann H and Burgering BMT: The small GTPase RALA controls c-Jun

N-terminal kinase-mediated FOXO activation by regulation of a JIP1

scaffold complex. J Biol Chem. 288:21729–21741. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Song H, Liu B, Huai W, Yu Z, Wang W, Zhao

J, Han L, Jiang G, Zhang L, Gao C and Zhao W: The E3 ubiquitin

ligase TRIM31 attenuates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by promoting

proteasomal degradation of NLRP3. Nat Commun.

7(13727)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Khan SR and Thamilselvan S:

Nephrolithiasis: A consequence of renal epithelial cell exposure to

oxalate and calcium oxalate crystals. Mol Urol. 4:305–312.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Huang HS, Ma MC and Chen J: Chronic

L-arginine administration increases oxidative and nitrosative

stress in rat hyperoxaluric kidneys and excessive crystal

deposition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 295:F388–F396.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Verkoelen CF, van der Boom BG, Houtsmuller

AB, Schröder FH and Romijn JC: Increased calcium oxalate

monohydrate crystal binding to injured renal tubular epithelial

cells in culture. Am J Physiol. 274:F958–F965. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Golub EE: Biomineralization and matrix

vesicles in biology and pathology. Semin Immunopathol. 33:409–417.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Vicencio JM, Galluzzi L, Tajeddine N,

Ortiz C, Criollo A, Tasdemir E, Morselli E, Ben Younes A, Maiuri

MC, Lavandero S and Kroemer G: Senescence, apoptosis or autophagy?

When a damaged cell must decide its path-a mini-review.

Gerontology. 54:92–99. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Liu X, Su H, Chen J, Zhu Y, Luo S, Ji M,

Chen K and Tang Y: Effects of Tamm-Horsfall protein on kidney stone

formation. J Med Postgrad. 922–925. 2017.

|

|

34

|

Umekawa T, Chegini N and Khan SR:

Increased expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)

by renal epithelial cells in culture on exposure to calcium

oxalate, phosphate and uric acid crystals. Nephrol Dial Transplant.

18:664–669. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Deng Y, Sun B and Li C: UP-3.135: COM

crystals stimulate the expression and activity of NADPH oxidase in

macrophage. Urology. 74 (Suppl)(S337)2009.

|

|

36

|

Mukai H, Miura Y, Kotani K, Kotoda A,

Kurosu H, Yamada T, Kuro-O M and Iwazu Y: The effects for

inflammatory responses by CPP with different colloidal properties

in hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep. 12(21856)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Viegas CSB, Rafael MS, Enriquez JL,

Teixeira A, Vitorino R, Luís IM, Costa RM, Santos S, Cavaco S,

Neves J, et al: Gla-rich protein acts as a calcification inhibitor

in the human cardiovascular system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

35:399–408. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Tesfamariam B: Involvement of vitamin

K-dependent proteins in vascular calcification. J Cardiovasc

Pharmacol Ther. 24:323–333. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Koeppert S, Ghallab A, Peglow S, Winkler

CF, Graeber S, Büscher A, Hengstler JG and Jahnen-Dechent W: Live

imaging of calciprotein particle clearance and receptor mediated

uptake: Role of calciprotein monomers. Front Cell Dev Biol.

9(633925)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Kutikhin AG, Feenstra L, Kostyunin AE,

Yuzhalin AE, Hillebrands JL and Krenning G: Calciprotein particles:

Balancing mineral homeostasis and vascular pathology. Arterioscler

Thromb Vasc Biol. 41:1607–1624. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Herrmann M, Schäfer C, Heiss A, Gräber S,

Kinkeldey A, Büscher A, Schmitt MM, Bornemann J, Nimmerjahn F,

Herrmann M, et al: Clearance of fetuin-A-containing calciprotein

particles is mediated by scavenger receptor-A. Circ Res.

111:575–584. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Heiss A, DuChesne A, Denecke B, Grötzinger

J, Yamamoto K, Renné T and Jahnen-Dechent W: Structural basis of

calcification inhibition by alpha 2-HS glycoprotein/fetuin-A.

Formation of colloidal calciprotein particles. J Biol Chem.

278:13333–13341. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Aghagolzadeh P, Bachtler M, Bijarnia R,

Jackson C, Smith ER, Odermatt A, Radpour R and Pasch A:

Calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells is induced by

secondary calciprotein particles and enhanced by tumor necrosis

factor-α. Atherosclerosis. 251:404–414. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Smith ER, Hanssen E, McMahon LP and Holt

SG: Fetuin-A-containing calciprotein particles reduce mineral

stress in the macrophage. PLoS One. 8(e60904)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Silaghi CN, Ilyés T, Van Ballegooijen AJ

and Crăciun AM: Calciprotein particles and serum calcification

propensity: Hallmarks of vascular calcifications in patients with

chronic kidney disease. J Clin Med. 9(1287)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Blaser MC and Aikawa E: Roles and

regulation of extracellular vesicles in cardiovascular mineral

metabolism. Front Cardiovasc Med. 5(187)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Disthabanchong S and Srisuwarn P:

Mechanisms of vascular calcification in kidney disease. Adv Chronic

Kidney Dis. 26:417–426. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Shishkova DK, Velikanova EA, Bogdanov LA,

Sinitsky MY, Kostyunin AE, Tsepokina AV, Gruzdeva OV, Mironov AV,

Mukhamadiyarov RA, Glushkova TV, et al: Calciprotein particles link

disturbed mineral homeostasis with cardiovascular disease by

causing endothelial dysfunction and vascular inflammation. Int J

Mol Sci. 22(12458)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Shishkova D, Lobov A, Zainullina B,

Matveeva V, Markova V, Sinitskaya A, Velikanova E, Sinitsky M,

Kanonykina A, Dyleva Y and Kutikhin A: Calciprotein particles cause

physiologically significant pro-inflammatory response in

endothelial cells and systemic circulation. Int J Mol Sci.

23(14941)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Feenstra L, Kutikhin AG, Shishkova DK,

Buikema H, Zeper LW, Bourgonje AR, Krenning G and Hillebrands JL:

Calciprotein particles induce endothelial dysfunction by impairing

endothelial nitric oxide metabolism. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

43:443–455. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Durand MJ and Gutterman DD: Diversity in

mechanisms of endothelium-dependent vasodilation in health and

disease. Microcirculation. 20:239–247. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Zhao Y, Vanhoutte PM and Leung SWS:

Vascular nitric oxide: Beyond eNOS. J Pharmacol Sci. 129:83–94.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Förstermann U and Sessa WC: Nitric oxide

synthases: Regulation and function. Eur Heart J. 33:829–837,

837a-837d. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Oe Y, Mitsui S, Sato E, Shibata N, Kisu K,

Sekimoto A, Miyazaki M, Sato H, Ito S and Takahashi N: Lack of

endothelial nitric oxide synthase accelerates ectopic calcification

in uremic mice fed an adenine and high phosphorus diet. Am J

Pathol. 191:283–293. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Lee HL, Woo KM, Ryoo HM and Baek JH: Tumor

necrosis factor-alpha increases alkaline phosphatase expression in

vascular smooth muscle cells via MSX2 induction. Biochem Biophys

Res Commun. 391:1087–1092. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Zickler D, Luecht C, Willy K, Chen L,

Witowski J, Girndt M, Fiedler R, Storr M, Kamhieh-Milz J, Schoon J,

et al: Tumour necrosis factor-alpha in uraemic serum promotes

osteoblastic transition and calcification of vascular smooth muscle

cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinases and activator

protein 1/c-FOS-mediated induction of interleukin 6 expression.

Nephrol Dial Transplant. 33:574–585. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Sage AP, Lu J, Tintut Y and Demer LL:

Hyperphosphatemia-induced nanocrystals upregulate the expression of

bone morphogenetic protein-2 and osteopontin genes in mouse smooth

muscle cells in vitro. Kidney Int. 79:414–422. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Li X, Yang HY and Giachelli CM: BMP-2

promotes phosphate uptake, phenotypic modulation, and calcification

of human vascular smooth muscle cells. Atherosclerosis.

199:271–277. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Liberman M, Johnson RC, Handy DE, Loscalzo

J and Leopold JA: Bone morphogenetic protein-2 activates NADPH

oxidase to increase endoplasmic reticulum stress and human coronary

artery smooth muscle cell calcification. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 413:436–441. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Byon CH, Javed A, Dai Q, Kappes JC,

Clemens TL, Darley-Usmar VM, McDonald JM and Chen Y: Oxidative

stress induces vascular calcification through modulation of the

osteogenic transcription factor Runx2 by AKT signaling. J Biol

Chem. 283:15319–15327. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Liu H, Li X, Qin F and Huang K: Selenium

suppresses oxidative-stress-enhanced vascular smooth muscle cell

calcification by inhibiting the activation of the PI3K/AKT and ERK

signaling pathways and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Biol Inorg

Chem. 19:375–388. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Blanc A, Pandey NR and Srivastava AK:

Distinct roles of Ca2+, calmodulin, and protein kinase C in

H2O2-induced activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, and protein kinase B

signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Antioxid Redox Signal.

6:353–366. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Zhao MM, Xu MJ, Cai Y, Zhao G, Guan Y,

Kong W, Tang C and Wang X: Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species

promote p65 nuclear translocation mediating high-phosphate-induced

vascular calcification in vitro and in vivo. Kidney Int.

79:1071–1079. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Shishkova D, Velikanova E, Sinitsky M,

Tsepokina A, Gruzdeva O, Bogdanov L and Kutikhin A: Calcium

phosphate bions cause intimal hyperplasia in intact aortas of

normolipidemic rats through endothelial injury. Int J Mol Sci.

20(5728)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Kurozumi A, Nakano K, Yamagata K, Okada Y,

Nakayamada S and Tanaka Y: IL-6 and sIL-6R induces STAT3-dependent

differentiation of human VSMCs into osteoblast-like cells through

JMJD2B-mediated histone demethylation of RUNX2. Bone. 124:53–61.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Tintut Y, Parhami F, Boström K, Jackson SM

and Demer LL: cAMP stimulates osteoblast-like differentiation of

calcifying vascular cells. Potential signaling pathway for vascular

calcification. J Biol Chem. 273:7547–7553. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Turner ME, Bartoli-Leonard F and Aikawa E:

Small particles with large impact: Insights into the unresolved

roles of innate immunity in extracellular vesicle-mediated

cardiovascular calcification. Immunol Rev. 312:20–37.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Ewence AE, Bootman M, Roderick HL, Skepper

JN, McCarthy G, Epple M, Neumann M, Shanahan CM and Proudfoot D:

Calcium phosphate crystals induce cell death in human vascular

smooth muscle cells: A potential mechanism in atherosclerotic

plaque destabilization. Circ Res. 103:e28–e34. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Wang S and Zhang Z: Biological

characteristics of nanobacteria and the relationship between

nanobacteria and oral stone diseases. J Oral Sci Res. 35:827–829.

2019.

|

|

70

|

Kao WK, Chole RA and Ogden MA: Evidence of

a microbial etiology for sialoliths. Laryngoscope. 130:69–74.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Zeng J, Yang F, Zhang W, Gong Q, Du Y and

Ling J: Association between dental pulp stones and calcifying

nanoparticles. Int J Nanomedicine. 6:109–118. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Zhang SM, Tian F, Jiang XQ, Li J, Xu C,

Guo XK and Zhang FQ: Evidence for calcifying nanoparticles in

gingival crevicular fluid and dental calculus in periodontitis. J

Periodontol. 80:1462–1470. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Yang F, Zeng J, Zhang W, Sun X and Ling J:

Evaluation of the interaction between calcifying nanoparticles and

human dental pulp cells: A preliminary investigation. Int J

Nanomedicine. 6:13–18. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Sakai Y, Nemoto E, Kanaya S, Shimonishi M

and Shimauchi H: Calcium phosphate particles induce interleukin-8

expression in a human gingival epithelial cell line via the nuclear

factor-κB signaling pathway. J Periodontol. 85:1464–1473.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Demir T: Is there any relation of

nanobacteria with periodontal diseases? Med Hypotheses. 70:36–39.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Sun H, Warren J, Yip J, Ji Y, Hao S, Han W

and Ding Y: Factors influencing gallstone formation: A review of

the literature. Biomolecules. 12(550)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Wen Y, Li Y, Yang Z, Wang XJ, Wei H, Liu

W, Tan AL, Miao XY, Wang QW, Huang SF, et al: Nanobacteria in

serum, bile and gallbladder mucosa of cholecystolithiasis patients.

Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 41:267–270. 2003.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|

|

78

|

Wang L, Shen W, Wen J, An X, Cao L and

Wang B: An animal model of black pigment gallstones caused by

nanobacteria. Dig Dis Sci. 51:1126–1132. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Wen Y, Li YG, Yang ZL, Wang XJ, Wei H, Liu

W, Miao XY, Wang QW, Huang SF, Yang J, et al: Detection of

nanobacteria in serum, bile and gallbladder mucosa of patients with

cholecystolithiasis. Chin Med J (Engl). 118:421–424.

2005.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

80

|

Kajander EO: Nanobacteria-propagating

calcifying nanoparticles. Lett Appl Microbiol. 42:549–552.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Liang L, Jin Z, Xu B, Guo Y, Peng M and

Wen Z: Mechanism of nanobacteria promoting apoptosis of human

gallbladder epithelial cells. Chin J Exp Surg. 36:1410–1413.

2019.

|