Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is characterized by

insulin resistance and dysfunction of pancreatic β cells (1). The inability of pancreatic β cells to

produce sufficient insulin to counteract insulin resistance leads

to hyperglycemia (2). Elevated

blood sugar levels result in excessive production of reactive

oxygen species (ROS), which can damage pancreatic β cells, thereby

decreasing their number and function (3,4).

Hyperglycemia not only increases ROS generation but also

compromises the antioxidant defense system in pancreatic β cells.

Research on antioxidant enzymes, including catalase (CAT),

superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione peroxidase and thioredoxin,

has shown that prolonged exposure to high glucose levels diminishes

the antioxidant capacity of pancreatic β cells (5). Additionally, hepatic insulin

resistance disrupts normal glucose metabolism by impairing the

ability to suppress gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. This

impairment results from decreased inhibition of key enzymes,

including glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate

carboxykinase (PEPCK) via the PI3K/Akt pathway (6,7).

Consequently, hepatic glucose output increases while glycogen

storage decreases (8).

Simultaneously, insulin resistance in adipose tissue enhances

lipolysis, increasing circulating fatty acids that fuel hepatic

gluconeogenesis through β-oxidation, further elevating PEPCK

activity (9). These combined

effects contribute to hyperglycemia and the progression of

T2DM.

Syzygium samarangense [SS; (Blume)] Merr.

& L. M. Perry, commonly known as rose or wax apple, belongs to

the Myrtaceae family and is widely cultivated across Southeast

Asia. Rose apple is rich in polyphenolic compounds, including

phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, ellagitannins, carotenoids and

triterpenoids (10,11). In type 1 diabetic rats induced by

streptozotocin (STZ), unprocessed rose apple powder decreases

hyperglycemia while preserving pancreatic β cell mass through

antioxidant and anti-inflammatory mechanisms (12). Our recent study employed

microwave-assisted extraction combined with response surface

technology to extract rose apple fruits, and ultrahigh-performance

liquid chromatography (UHPLC)-microtime of flight (micrOTOF) Q

II-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis was used to identify

the phytochemical profiles of the extract (13). High concentrations of 12 bioactive

compounds, including matairesinol and phenolic substances, were

discovered (13). Furthermore,

antioxidant properties of rose apple extracts can prevent

glucotoxicity in a rat insulinoma cell line (INS-1 cells) (13). However, the effects of rose apple

extracts on type 2 diabetic rats remain unexplored.

Materials and methods

Plant material and preparation of SS

extract (SSE)

SSE was prepared and the major bioactive compounds

were identified as previously described (13).

Animals

A total of 20 adult male Wistar rats (age, 6 weeks;

weight, 180-220 g) were obtained from Nomura Siam International in

Bangkok, Thailand. All rats were housed in a temperature- and

humidity-controlled environment (23±3˚C; humidity, 60±10%) with a

12/12-h light/dark cycle at the Animal Center of Ubon Ratchathani

University, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand. They had unrestricted

access to rodent diet and water and were allowed 1 week for

acclimatization. The Animal Ethics Committee of Ubon Ratchathani

University approved the protocol for animal experimentation

(approval no. 37/2564 IACUC).

Induction of T2DM using high-fat diet

(HFD) and low-dose STZ

The rats were divided into two dietary groups:

Normal pellet diet (NPD; 12% calories from fat) and HFD; 58% fat,

25% protein and 17% carbohydrate, as percentages of total kcal).

The HFD consisted of powdered NPD, 365 g/kg (National Laboratory

Animal Center, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand);

casein, 250 g/kg (Difco, Becton Dickinson); cholesterol, 10 g/kg

(Loba Chemie PVT Ltd.); vitamin and mineral mixture, 60 g/kg

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA); 2-amino-4-(methylthio) butanoic

acid-methionine, 3 g/kg (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA); yeast powder,

1 g/kg and sodium chloride, 1 g/kg (14). Following a 2 week dietary

modification period, the rats on HFD received an intraperitoneal

injection of STZ at a dosage of 45 mg/kg body weight, dissolved in

0.1 M sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.5). At 3 days post-STZ injection,

glucose levels were assessed in all rats using blood samples

obtained from the tail tip using a glucometer (Accu-Chek Performa;

Roche Diagnostics). Only rats with fasting blood glucose (FBG)

levels ≥200 mg/dl were included in the diabetic group (DM)

(15). The control rats were

administered an injection of 0.1 M sodium citrate buffer at pH

4.5.

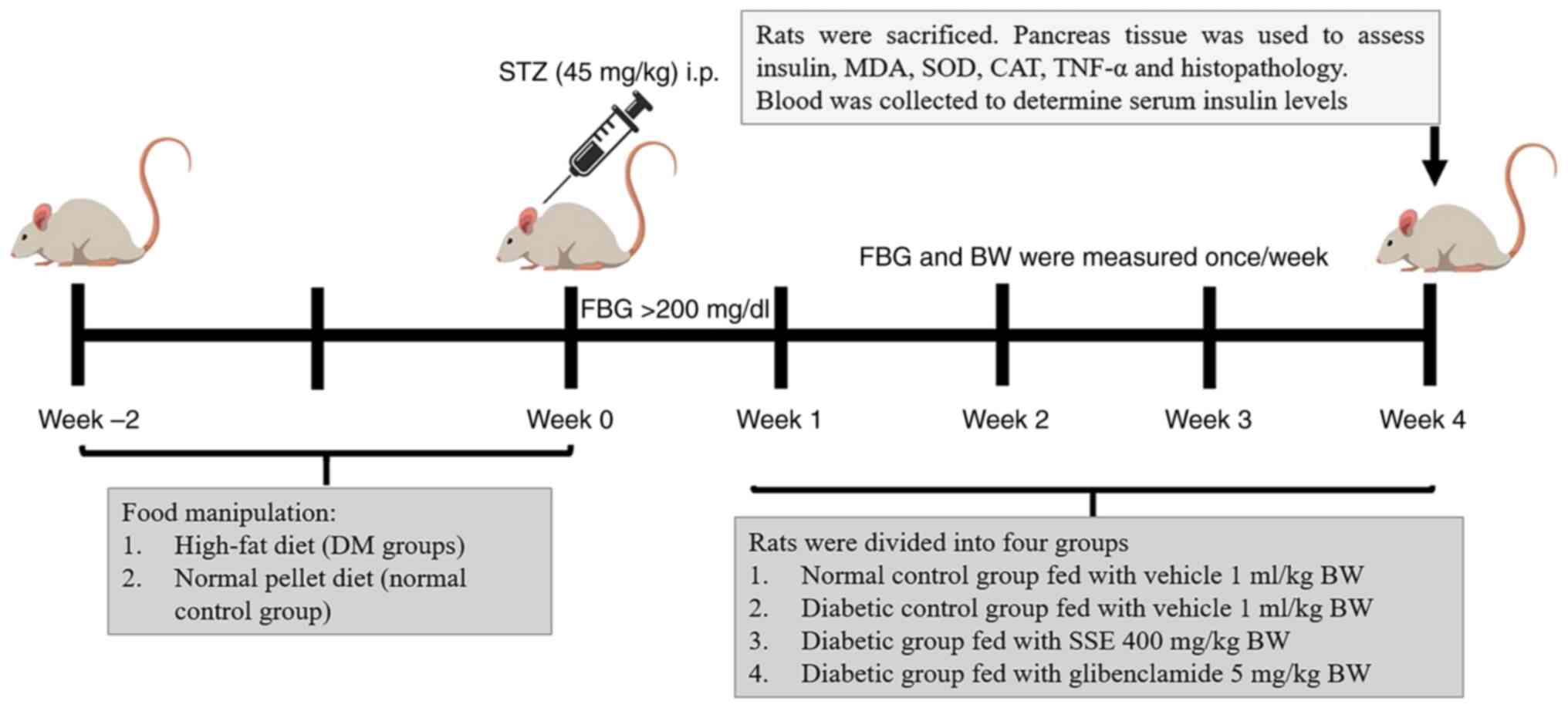

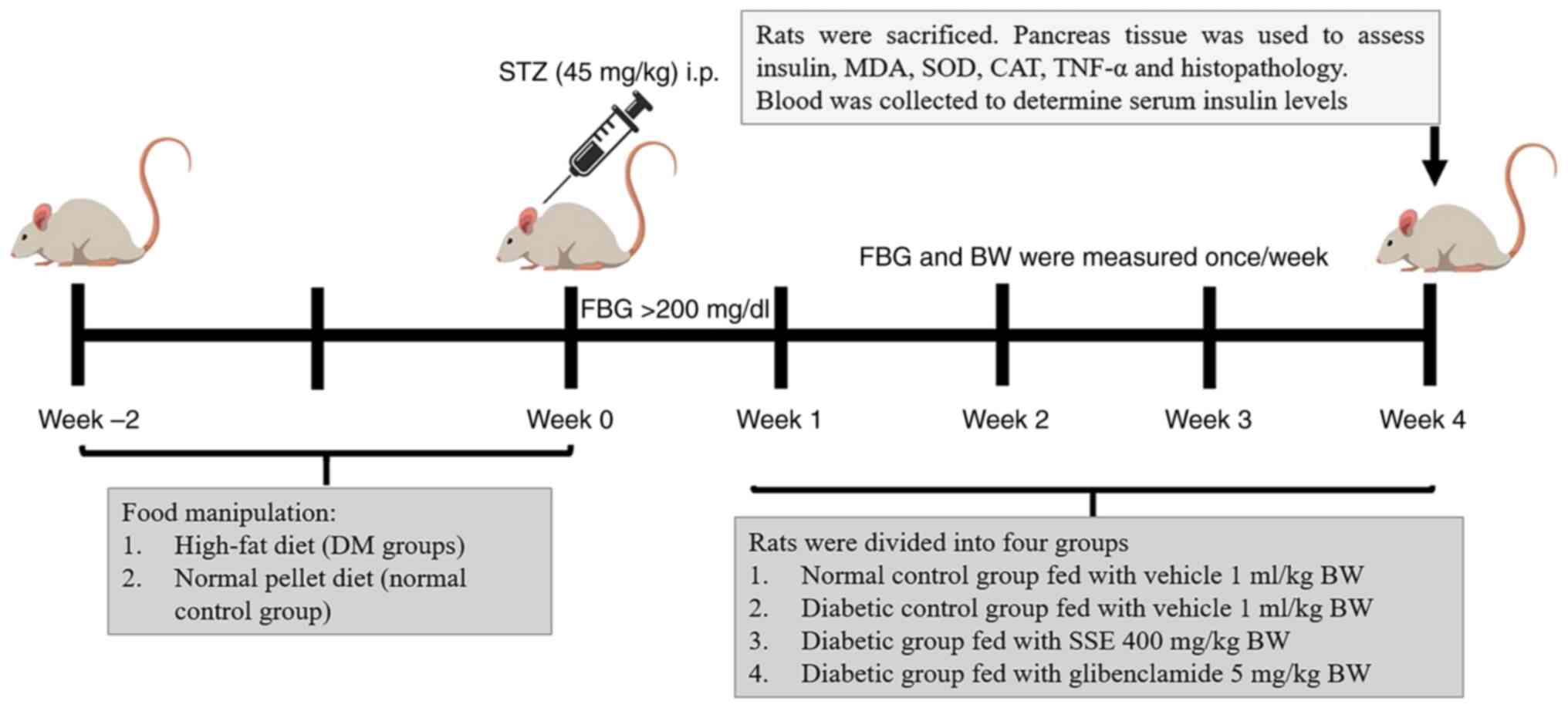

Experimental design

Following the establishment of diabetes, diabetic

rats were orally administered glibenclamide or SSE at a volume of 1

ml/kg vehicle once daily. The rats were randomly assigned into four

groups (n=5/group) as follows: Control and DM rats received only

the vehicle; DM + SSE comprised DM rats treated with SSE at a

dosage of 400 mg/kg body weight (; chosen based on preliminary

findings showing effective antihyperglycemic activity without

detectable toxicity in diabetic rats) and glibenclamide group (DM +

GB) included DM rats receiving glibenclamide [Innova CapTab, Solan

(H.P.)] at a dosage of 5 mg/kg body weight, serving as the positive

control group (16). The treatment

period lasted for 4 weeks, based on a previous study (12), and was considered sufficient for

assessing sub-chronic exposure. The experimental protocol is

illustrated in Fig. 1.

| Figure 1Experimental protocol. STZ,

streptozotocin; DM, diabetes mellitus; MDA, malondialdehyde; SOD,

superoxide dismutase; CAT, catalase; H&E, hematoxylin and

eosin; BW, body weight; SSE, Syzygium samarangense extract;

FBG, fasting blood glucose; i.p., intraperitoneal. |

Collection of blood samples

At the end of the study period, the rats underwent

an overnight fast and were euthanized via intraperitoneal

administration of thiopental sodium (120 mg/kg body weight;

Scott-Edil Pharmacia Limited). Death was confirmed by the absence

of heartbeat, respiration, corneal reflex and response to toe

pinch, in accordance with the American Veterinary Medical

Association guidelines for the euthanasia of animals (2020)

(17). Blood samples were obtained

through heart puncture. The blood collection tubes were immediately

placed on ice, and serum was separated by centrifugation at 3,500 x

g for 15 min at 4˚C. The serum samples were then stored at -80˚C

until further analysis. Fresh anticoagulated blood was transported

to the Pathological Laboratory at Ubon Ratchathani University

Hospital for the measurement of liver enzyme levels, including

alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and

aspartate aminotransferase (AST), using kinetic ultraviolet

spectrophotometry with a Beckman Coulter AU680 Analyzer (Beckman

Coulter).

Determination of pancreatic and serum

insulin levels

Pancreatic tissue (80 mg) was homogenized in a

Teflon homogenizer (Glas-Col homogenizer system) using RIPA lysis

buffer with protease inhibitor (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Following sonication (20 kHz; three cycles of 10 sec with 30-sec

intervals), the homogenate was centrifuged at 2,000 x g for 10 min

at 4˚C. The pancreatic protein concentration was measured using a

micro-BCA kit (cat. no. SK3061; Bio Basic). Serum insulin levels

and pancreatic proteins were determined using a Rat Insulin ELISA

kit (cat. no. RAB0904; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) according to the

manufacturer's guidelines.

Assay for lipid peroxidation

Malondialdehyde (MDA), a product of lipid

peroxidation, interacts with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) to generate

TBA reactive substances (TBARS), which are used to assess lipid

peroxidation. Lipid peroxidation was evaluated according to the

manufacturer's instructions (cat. no. MAK085, Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA). To produce TBARS, 600 µl TBA solution was added to each

Eppendorf tube containing either a pancreatic protein sample or an

MDA standard (0-20 mM). The tubes were incubated at 95˚C for 1 h.

Samples and MDA standards were transferred into a 96-well plate at

a volume of 200 µl/well. The concentration of TBARS in pancreatic

protein samples and MDA standards was quantified using a

spectrophotometer at 532 nm (Fluostar Omega, BMG Labtech).

Determination of antioxidant

markers

CAT activity in pancreatic tissue was measured using

a CAT assay kit (cat. no. MAK381; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA)

following the manufacturer's instructions. CAT activity was

quantified as the amount of enzyme required to degrade 1 µmol

hydrogen peroxide/min. The activity of SOD was evaluated with a SOD

Assay kit (cat. no. 574601; Merck Millipore) according to the

manufacturer's guidelines. SOD activity was quantified as the

amount of enzyme necessary to achieve 50% dismutation of the

superoxide radical.

Determination of inflammatory

markers

Quantitative measurement of TNF-α levels in the

pancreas was conducted using a Rat TNF-α ELISA kit (cat. no.

RAB0479; Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA) in accordance with the

manufacturer's guidelines.

Western blotting

Liver tissue (80 µg) was lysed in 200 µl RIPA

solution containing a protease inhibitor cocktail (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). The tissue homogenates were centrifuged at

14,000 x g for 15 min at 4˚C and the supernatant was collected. The

total protein concentration was measured using a Micro BCA protein

assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amounts of total

protein (150 µg/lane) were resolved using 12% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and

subsequently transferred to a PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories,

Inc.). Non-specific binding was blocked using 5% (w/v) skimmed milk

in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBST) for 60 min at

room temperature. The membranes were incubated overnight at 4˚C

with rat monoclonal anti-PEPCK (cat. no. 12940S; Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc.) and mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin (both 1:1,000;

cat. no. STCSC-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). After

washing with TBST buffer, the membranes were incubated with

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (PEPCK, 1:3,000; β-actin,

1:5,000; both Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. cat. nos. 7074S and

7076S, respectively) for 1 h at room temperature. Protein bands

were detected using DAB substrate (cat.no. E-IR-R101; Elabscience,

Wuhan, China), and band intensities were assessed with ImageJ

software (version 1.43; National Institutes of Health).

Histopathological examination

The pancreatic tissue was excised and weighed. Half

of each tissue specimen was preserved in 10% neutral buffered

formalin at room temperature for 24 h and processed for embedding

in paraffin blocks. Thin slices (5 µm) of paraffin-embedded tissue

were prepared, deparaffinized and stained with hematoxylin for 8

min and eosin for 1 min at room temperature. Images (x200) were

captured using Nikon ECLIPSE Ni-U light microscope and analyzed

using NIS-Elements software (Nikon Corporation).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS software (version

23; IBM Corp.). All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Normality

of the data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Differences were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by

Tukey-Kramer's post hoc test. P#x003C;0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Bioactive compounds derived from

SSE

The total phenolic compound content was 10.21±0.22

mg GAE/g, as reported in our previous work (13).

Effect of SSE on FBG, body weight and

food intake

FBG levels were elevated in diabetic (DM) compared

with control rats (Table I).

Diabetic rats treated with SSE at 400 mg/kg (DM + SSE) exhibited

decreased FBG levels, however, this reduction was not statistically

significant. By contrast, diabetic rats treated with glibenclamide

at 5 mg/kg (DM + GB) demonstrated a significant decrease in FBG

compared with DM rats. Despite increased food intake, DM rats

showed a marked decrease in body weight compared with control rats.

Following 28 days of SSE treatment, the DM + SSE rats exhibited an

increase in body weight, however, this was not significant compared

with untreated DM rats.

| Table IEffects of SSE on FBG, body weight

and food intake in diabetic rats. |

Table I

Effects of SSE on FBG, body weight

and food intake in diabetic rats.

| | Mean FBG,

mg/dl | Mean body weight,

g | Mean food intake,

g |

|---|

| Group | Week 1 | Week 4 | Week 1 | Week 4 | Week 1 | Week 4 |

|---|

| Control | 100.33±22.06 | 106.50±24.37 | 255.23±6.54 | 508.12±16.56 | 22.98±3.78 | 17.73±2.01 |

| DM |

389.33±31.20a |

425.00±34.47a | 250.15±8.01 |

334.33±20.29a | 29.87±4.62 |

35.83±2.46a |

| DM + SSE |

401.33±31.20a |

314.67±35.79a | 263.60±7.16 |

372.14±18.14a | 28.20±4.62 |

35.95±2.46a |

| DM + GB |

311.40±24.17a |

278.80±21.55a,b | 249.08±7.16 |

370.62±18.14a | 23.36±4.14 |

36.52±2.20a |

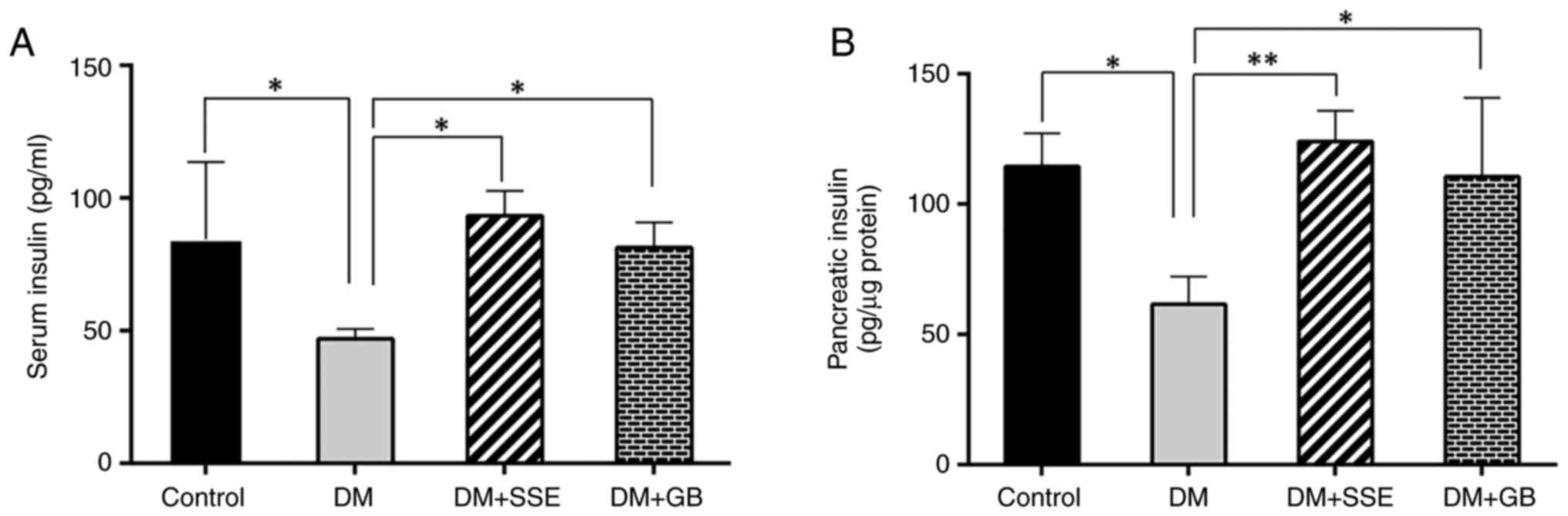

Effect of SSE on serum and pancreatic

insulin levels

Serum (Fig. 2A) and

pancreatic insulin levels (Fig. 2B)

were significantly decreased in DM compared with control rats.

Notably, DM + SSE or DM + GB rats exhibited elevated serum and

pancreatic insulin levels compared with untreated DM rats. These

findings underscore the potential of SSE to alleviate hyperglycemia

in diabetic rats by preserving pancreatic β cells, as indicated by

the maintenance of islet area and enhancing insulin release.

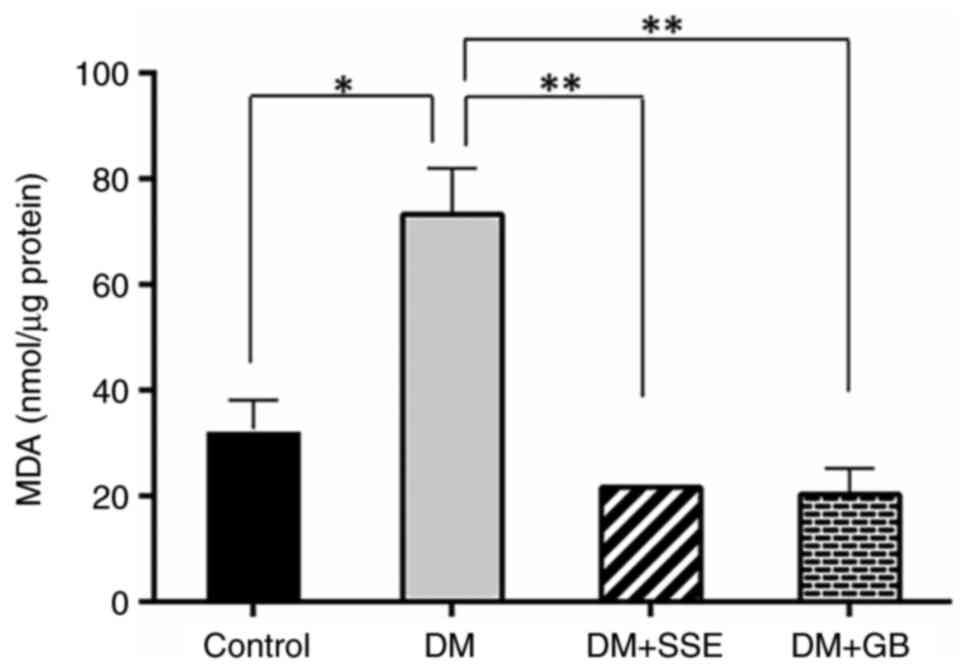

Effect of SSE on lipid peroxidation in

pancreatic tissue

TBARS levels indicate MDA as a byproduct of lipid

peroxidation. Compared with control rats, MDA levels in DM rats

were significantly elevated (Fig.

3). However, after 28 days of treatment with SSE and

glibenclamide, MDA levels in the treated diabetic rats

significantly decreased.

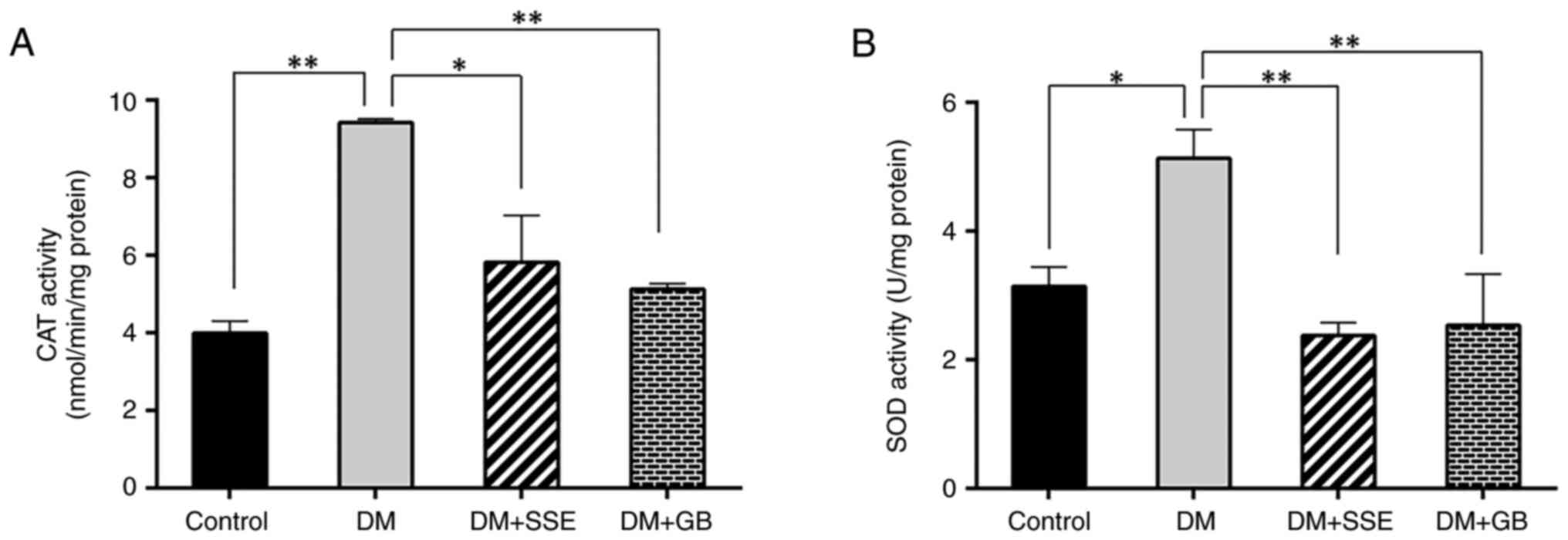

Effect of SSE on CAT and SOD

activities

DM rats exhibited increased CAT activity compared

with control rats, indicating heightened oxidative stress (Fig. 4A). SSE significantly decreased CAT

activity compared with untreated DM rats. The amount of SOD

required to eliminate superoxide radicals was elevated in DM rats,

indicating increased SOD activity. SSE treatment led to a

substantial reduction in SOD activity compared with untreated DM

rats (Fig. 4B). These data suggest

that the decrease in antioxidant enzyme activity in SSE-treated

diabetic rats resulted from a reduction of free radicals in

pancreatic tissue.

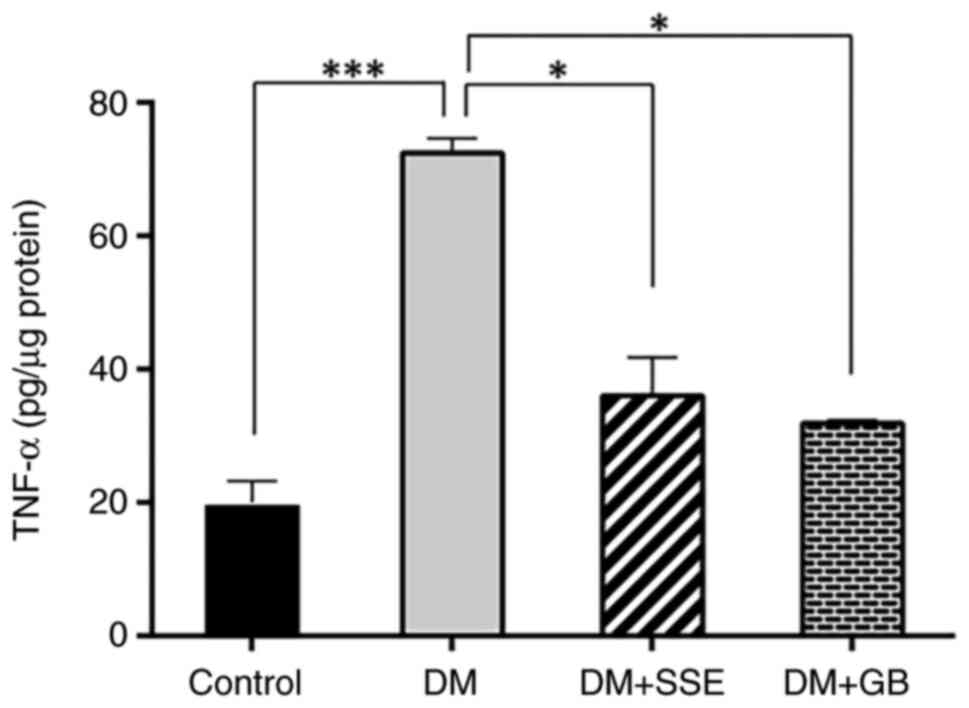

Effect of SSE on proinflammatory

cytokine markers

The apoptosis of pancreatic β cells in diabetes is

associated with proinflammatory cytokines (18). Therefore, TNF-α, a key

proinflammatory cytokine, was measured using ELISA to determine if

SSE preserves pancreatic β cells by reducing the synthesis of

proinflammatory cytokines. DM rats had significantly increased

TNF-α levels in pancreatic tissue compared with control rats. SSE

or glibenclamide resulted in a significant decrease in TNF-α levels

in DM rats (Fig. 5).

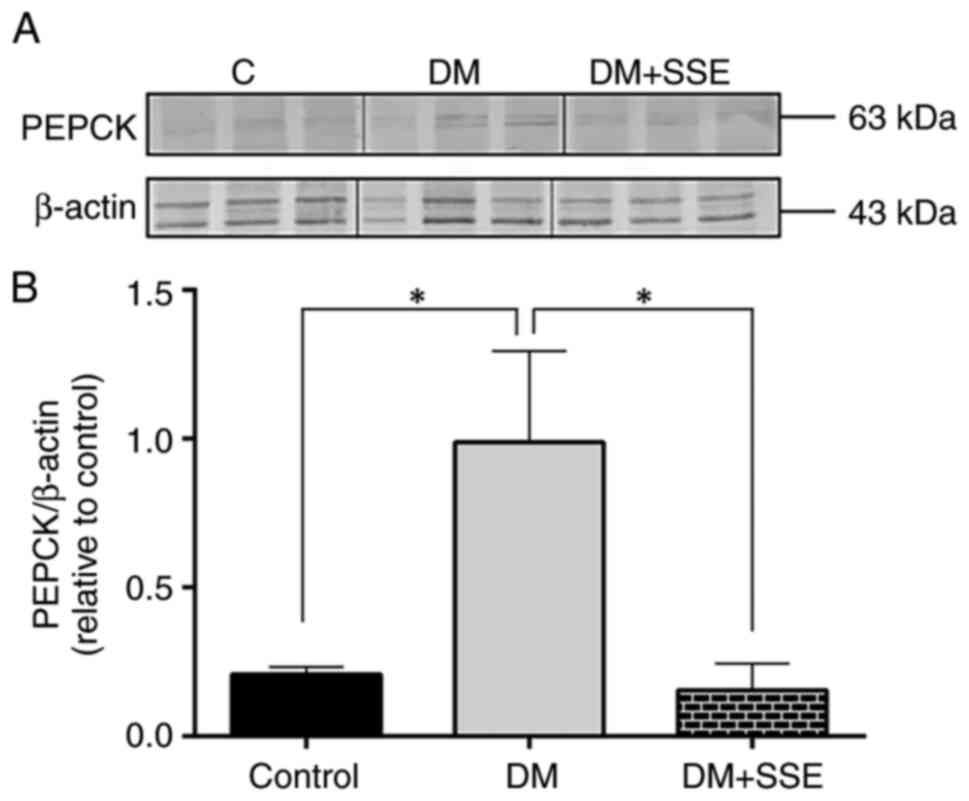

Effect of SSE on hepatic gluconeogenic

enzymes

The elevation of hepatic glucose synthesis, driven

by the activation of gluconeogenic enzymes, contributes to

hyperglycemia in diabetic conditions (19). The present study evaluated the

expression of PEPCK, a key gluconeogenic enzyme in the liver, via

western blot analysis. The results demonstrated that hepatic PEPCK

expression was significantly increased in DM rats compared with

controls. However, compared with no treatment, SSE treatment

significantly reduced hepatic PEPCK expression in DM rats (Fig. 6).

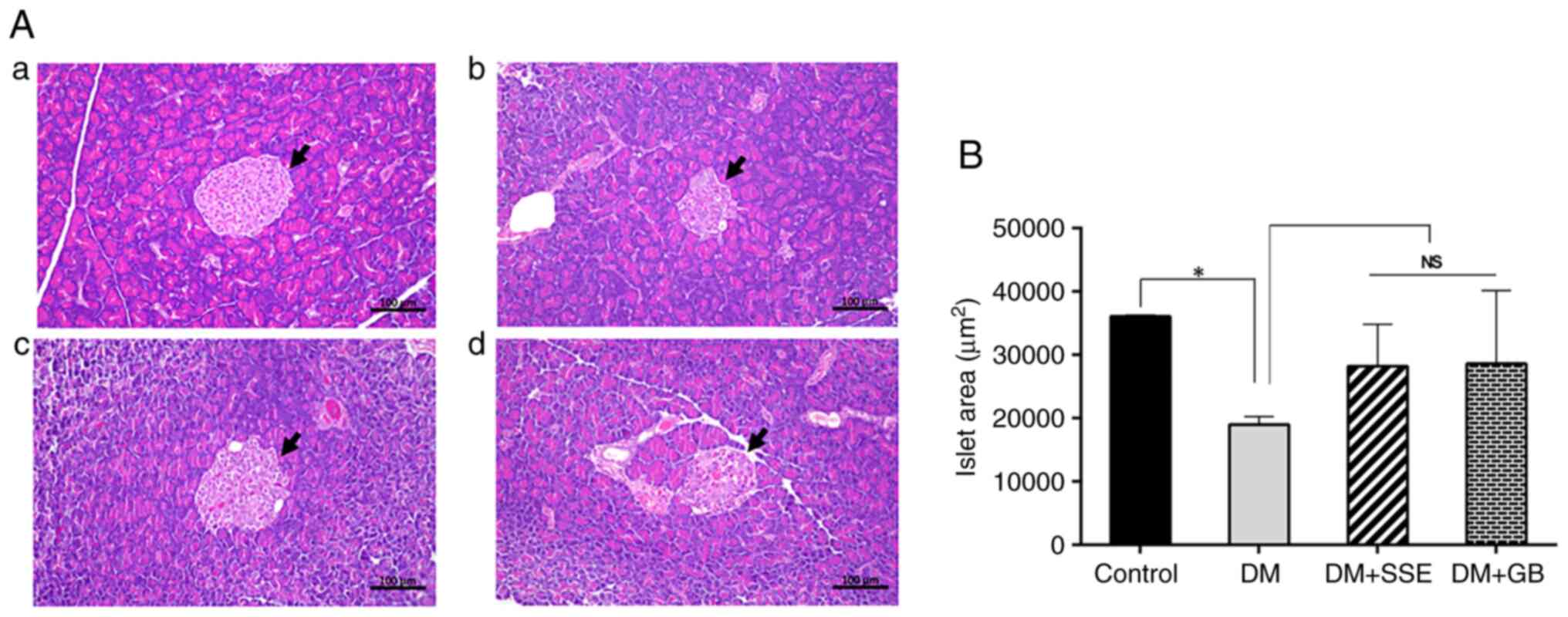

Histopathological changes in

pancreatic islets

Histo-pathological alterations in the pancreatic

islets were observed using H&E staining (Fig. 7). In control rats, the histological

examination revealed the typical structure of islet cells.

Conversely, DM rats exhibited abnormalities, as evidenced by a

notable decrease in islet size and a deviation from the typical

spherical morphology observed in control rats. DM rats administered

SSE, along with those receiving glibenclamide, showed an increase

in pancreatic islet size compared with DM rats; however, this

difference was not statistically significant.

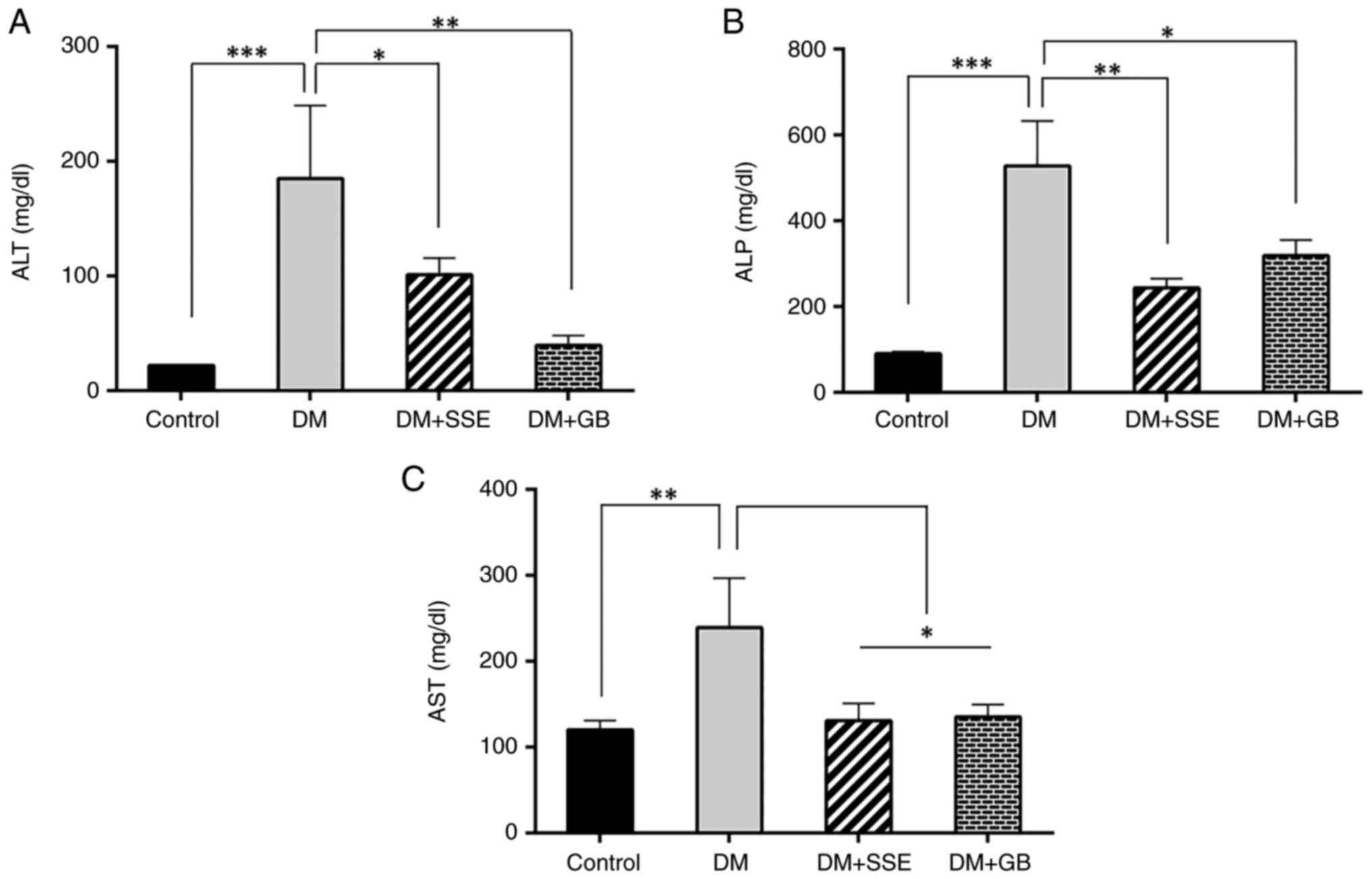

Liver function enzyme levels

Hyperglycemia is recognized as a contributor to

oxidative stress and hepatic damage (20). The present study assessed serum

liver enzyme levels, which serve as indicators of hepatic injury.

DM rats exhibited signs of hepatic injury, as evidenced by

substantial elevations in serum concentrations of alanine

aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and aspartate

aminotransferase (AST) (Fig. 8).

SSE or glibenclamide markedly reduced the increased levels of ALT,

ALP, and AST, suggesting a protective effect of SSE against

diabetes-induced hepatic damage.

Discussion

Rats with T2DM induced by a combination of HFD and

low-dose STZ were used to examine the potential antidiabetic

effects of SSE, as well as its impact on pancreatic oxidative

stress and inflammation. Consistent with findings in the literature

(21), the present results

demonstrated a notable increase in glucose levels and food intake,

accompanied by a decrease in body weight in rats subjected to HFD

and low-dose STZ treatment. Additionally, diabetic rats presented

decreased serum and pancreatic insulin levels. The weight loss in

diabetic rats can be attributed to increased protein breakdown and

fat mobilization due to diminished insulin production, which

impairs glucose absorption and utilization (12). Moreover, impaired insulin secretion

contributes to increased appetite, leading to polyphagia in

diabetic rats (22). Treatment with

SSE over a 28-day period resulted in decreased hyperglycemia in

diabetic rats, alongside significantly elevated serum and

pancreatic insulin levels, indicating the potential of SSE to

preserve pancreatic β cell mass and enhance insulin production.

This aligns with a prior study involving STZ-induced type 1

diabetic rats, where administration of SSE fruit powder (100 mg/kg)

attenuated hyperglycemia, increased serum insulin concentrations

and enhanced pancreatic β cell activity, as evidenced by increased

Homeostatic Model Assessment of β cell Function (12). SSE fruit powder contains notable

quantities of phenolics, flavonoids and anthocyanins, which exhibit

considerable antidiabetic properties by improving pancreatic β cell

function and promoting insulin production in individuals with

diabetes (23,24). Furthermore, our previous

investigation revealed that SSE comprises at least 12 compounds,

including cinnamic and glucaric acid, maloyl-hexose, citric,

mono-caffeoylquinic, gallic, 2-methylcitric and ellagic acid,

naringin-O-glucoside, kaempferol deoxyhexose, benzyl-diglycoside

and matairesinol (13). Among these

compounds, naringin has been extensively studied for its diverse

antidiabetic effects (23-26).

Naringin has demonstrated a dose-dependent decrease in blood

glucose levels and an elevation in insulin concentrations through

its antioxidative effects in STZ-induced diabetic rats (25). Additionally, naringin effectively

decreases inflammation, oxidative stress and mitochondrial

apoptosis caused by T2DM-related steatohepatitis via the RAGE/NF-κB

pathway (26). Kaempferol, another

flavonoid, also exhibits antidiabetic properties. The

administration of kaempferol to STZ-induced diabetic rats is

associated with a return to near-normal levels of plasma glucose,

insulin, lipid peroxidation products and both enzyme- and

non-enzyme-dependent antioxidants (27). In diabetic mice, kaempferol restores

hexokinase activity while inhibiting hepatic pyruvate carboxylase

activity and gluconeogenesis, indicating its ability to enhance

skeletal muscle glucose metabolism and diminish liver

gluconeogenesis (28). To the best

of our knowledge, matairesinol, a notable secondary metabolite

found in SSE, has been less extensively studied for its

antidiabetic effects. However, in a rat model of brain sepsis,

matairesinol increases antioxidant enzyme levels in brain tissue

and inhibits neuronal death (29).

Hyperglycemia induces the generation of ROS while

simultaneously impairing the antioxidant defense mechanisms. This

imbalance can lead to oxidative stress, promoting pancreatic β cell

death and a subsequent decline in insulin production over time

(30). The present study

investigated the antioxidant properties of SSE in pancreatic

tissue. SSE in diabetic rats not only enhanced the activity of

antioxidant enzymes but also decreased levels of oxidative stress

markers. In the pancreatic tissue of rats with STZ-induced

diabetes, SSE fruit powder demonstrates antioxidant activity,

associated with an increase in insulin-expressing pancreatic β

cells and pancreatic insulin protein levels (12). Additionally, SSE exerts notable

antioxidant effects in liver damage induced by carbon tetrachloride

(31). These beneficial effects may

be due to the presence of potent antioxidant compounds in SSE,

including phenolics, gallic acid, kaempferol, naringin and

matairesinol.

Oxidative stress and inflammatory responses are

associated with hyperglycemia. Hyperglycemia triggers oxidative

stress and inflammatory signaling pathways, resulting in the

synthesis of inflammatory cytokines within pancreatic β cells,

ultimately leading to cellular damage and dysfunction (32). Consistent with prior studies

(33,34), the present study observed elevated

levels of TNF-α in the pancreatic tissue of diabetic rats, while

treatment with SSE resulted in a decrease in TNF-α levels.

Furthermore, SSE alleviates insulin resistance and mitigates

inflammation in the liver following TNF-α exposure (35).

Dysregulation of glucose metabolism is a common

feature of diabetes and contributes to increased hepatic glucose

production through gluconeogenesis. This upregulation is primarily

driven by the increased expression of key gluconeogenic enzymes

such as PEPCK and glucose-6-phosphatase, which exacerbates

hyperglycemia under diabetic conditions (20). Here, SSE significantly downregulated

the expression of hepatic PEPCK, indicating its potential role in

suppressing gluconeogenesis. This effect may be due to kaempferol,

a major bioactive compound found in SSE. Additionally, other

phytochemicals present in SSE, such as matairesinol and glucaric

acid, suppress PEPCK expression by inhibiting the signaling

pathways of PGC-1α and FOXO1, key transcription factors that

regulate gluconeogenic gene expression (36,37).

SSE exhibited hepatoprotective effects, as evidenced

by a significant decrease in elevated liver enzyme levels,

including AST, ALT and ALP, in diabetic rats. These beneficial

effects may be associated with the antioxidant and

anti-inflammatory properties of the bioactive constituents within

SSE.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is

the first investigation of the antidiabetic properties of SSE in

rats with diabetes induced by HFD and low-dose STZ. The effects are

attributed to the enhancement of antioxidant defense mechanisms,

reduction in oxidative stress levels and suppression of the

proinflammatory cytokine TNF-α. These findings suggest that SSE may

serve as a supplementary treatment to help preserve β cell function

in individuals with T2DM. However, the present study had

limitations, including the use of a single SSE dose (400 mg/kg), a

relatively small sample size and a short treatment duration (4

weeks). Future investigations should include multiple doses,

extended treatment periods and larger sample sizes to optimize

therapeutic efficacy and assess potential long-term effects and

safety of SSE.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Associate Professor

Songsak Chumpawadee (Department of Agricultural Technology,

Mahasarakham University, Maha Sarakham, Thailand) for producing the

high-fat diet used to induce T2DM in the rats. The authors would

also like to thank Mr Tanapat Wisapon (Faculty of Pharmaceutical

Sciences, Ubon Ratchathani University, Ubon Ratchathani, Thailand),

who contributed to the design of equipment for pellet production

and drying, facilitating the preparation of high-fat diet for the

experimental rats.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National

Science, Research, and Innovation Fund (Fundamental Fund 2565-2566)

and the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Ubon Ratchathani

University (grant no. phar.ubu.0604-11-3/2567).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

NM and KS conceived the study and wrote the

manuscript. BY designed and performed experiments, constructed

figures and wrote the manuscript. NM, KS, PP, SP, SS, JK, PK, JO,

CP and YB designed and performed experiments and analyzed data. NC

performed experiments and analyzed data. NM and KS confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. NM edited the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal

Ethics Committee of Ubon Ratchathani University (approval no.

37/2564 IACUC).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ and van Haeften

TW: Type 2 diabetes: Principles of pathogenesis and therapy.

Lancet. 365:1333–1346. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Porte D Jr and Kahn SE: Beta-cell

dysfunction and failure in type 2 diabetes: Potential mechanisms.

Diabetes. 50 (Suppl 1):S160–S163. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Park JH, Shim HM, Na AY, Bae KC, Bae JH,

Im SS, Cho HC and Song DK: Melatonin prevents pancreatic β-cell

loss due to glucotoxicity: The relationship between oxidative

stress and endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Pineal Res. 56:143–153.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Tang C, Han P, Oprescu AI, Lee SC,

Gyulkhandanyan AV, Chan GNY, Wheeler MB and Giacca A: Evidence for

a role of superoxide generation in glucose-induced beta-cell

dysfunction in vivo. Diabetes. 56:2722–2731. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Coskun O, Kantera M, Korkmaz A and Oter S:

Quercetin, a flavonoid antioxidant, prevents and protects

streptozotocin-induced oxidative stress and beta-cell damage in rat

pancreas. Pharmacol Res. 51:117–123. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Saltiel AR and Kahn CR: Insulin signalling

and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature.

414:799–806. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Lu M, Wan M, Leavens KF, Chu Q, Monks BR,

Fernandez S, Ahima RS, Ueki K, Kahn CR and Birnbaum MJ: Insulin

regulates liver metabolism in vivo in the absence of hepatic Akt

and Foxo1. Nat Med. 18:388–395. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Adeva-Andany MM, Pérez-Felpete N,

Fernández-Fernández C, Donapetry-García C and Pazos-García C: Liver

glucose metabolism in humans. Biosci Rep. 36(e00416)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Mobasheri L, Ahadi M, Beheshti Namdar A,

Alavi MS, Bemidinezhad A, Moshirian Farahi SM, Esmaeilizadeh M,

Nikpasand N, Einafshar E and Ghorbani A: Pathophysiology of

diabetic hepatopathy and molecular mechanisms underlying the

hepatoprotective effects of phytochemicals. Biomed Pharmacother.

167(115502)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Shü ZH, Shiesh CC and Lin HL: Wax apple

(Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merr and L.M. Perry) and

related species. In: Postharvest Biology and Technology of Tropical

and Subtropical Fruits. Vol 4. pp458-473, 2011.

|

|

11

|

Mukaromah AS: Wax apple (Syzygium

samarangense (Blume) Merr & L.M. Perry): A comprehensive

review in phytochemical and physiological perspectives. Perspect J

Biol Appl Biol. 3:40–58. 2020.

|

|

12

|

Khamchan A, Paseephol T and Hanchang W:

Protective effect of wax apple [Syzygium samarangense

(Blume) Merr. & L.M. Perry] against streptozotocin-induced

pancreatic β-cell damage in diabetic rats. Biomed Pharmacother.

108:634–645. 2018.

|

|

13

|

Suksri K, Yingngam B and Muangchan N:

Optimization of phenolic extraction from Syzygium

samarangense fruit and its protective properties against

glucotoxicity-induced pancreatic β-cell death. ScienceAsia.

49:529–540. 2023.

|

|

14

|

Srinivasan K, Viswanad B, Asrat L, Kaul CL

and Ramarao P: Combination of high-fat diet-fed and low-dose

streptozotocin-treated rat: A model for type 2 diabetes and

pharmacological screening. Pharmacol Res. 52:313–320.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Miaffo D, Ntchapda F, Mahamad TA, Maidadi

D and Kamanyi A: Hypoglycemic, antidyslipidemic and antioxydant

effects of Vitellaria paradoxa barks extract on high-fat diet and

streptozotocin-induced type 2 diabetes rats. Metabol Open.

9(100071)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gandhi GR and Sasikumar P: Antidiabetic

effect of Merremia emarginata Burm. F. in streptozotocin induced

diabetic rats. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2:281–286. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

American Veterinary Medical Association.

AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. AVMA, Schaumburg,

IL, 2020. Available from: https://www.avma.org/resources-tools/avma-policies/avma-guidelines-euthanasia-animals.

|

|

18

|

Russell MA and Morgan NG: The impact of

anti-inflammatory cytokines on the pancreatic β-cell. Islets.

6(e950547)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jiang S, Young JL, Wang K, Qian Y and Cai

L: Diabetic-induced alterations in hepatic glucose and lipid

metabolism: The role of type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus

(review). Mol Med Rep. 22:603–611. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yoopum S, Wongmanee N, Rojanaverawong W,

Rattanapunya S, Sumsakul W and Hanchang W: Mango (Mangifera indica

L.) seed kernel extract suppresses hyperglycemia by modulating

pancreatic β cell apoptosis and dysfunction and hepatic glucose

metabolism in diabetic rats. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int.

30:123286–123308. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hininger-Favier I, Benaraba R, Coves S,

Anderson RA and Roussel AM: Green tea extract decreases oxidative

stress and improves insulin sensitivity in an animal model of

insulin resistance, the fructose-fed rat. J Am Coll Nutr.

28:355–361. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ozougwu JC, Obimba KC, Belonwu CD and

Unakalamba CB: The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of type 1 and

type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Physiol Pathophysiol. 4:46–57.

2013.

|

|

23

|

Lin D, Xiao M, Zhao J, Li Z, Xing B, Li X,

Kong M, Li L, Zhang Q, Liu Y, et al: An overview of plant phenolic

compounds and their importance in human nutrition and management of

type 2 diabetes. Molecules. 21(1374)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Dragan S, Andrica F, Maria-Corina S and

Timar R: Polyphenols-rich natural products for treatment of

diabetes. Curr Med Chem. 22:14–22. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ali MM and Abd El Kader MA: The influence

of naringin on the oxidative state of rats with

streptozotocin-induced acute hyperglycaemia. Z Naturforsch C J

Biosci. 59:726–733. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Syed AA, Reza MI, Shafiq M, Kumariya S,

Singh P, Husain A, Hanif K and Gayen JR: Naringin ameliorates type

2 diabetes mellitus-induced steatohepatitis by inhibiting

RAGE/NF-κB mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. Life Sci.

257(118118)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Al-Numair KS, Chandramohan G, Veeramani C

and Alsaif MA: Ameliorative effect of kaempferol, a flavonoid, on

oxidative stress in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Redox

Rep. 20:198–209. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Alkhalidy H, Moore W, Wang Y, Luo J,

McMillan RP, Zhen W, Zhou K and Liu D: The flavonoid kaempferol

ameliorates streptozotocin-induced diabetes by suppressing hepatic

glucose production. Molecules. 23(2338)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wu Q, Wang Y and Li Q: Matairesinol exerts

anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects in sepsis-mediated brain

injury by repressing the MAPK and NF-κB pathways through

up-regulating AMPK. Aging (Albany NY). 13:23780–23795.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Banday MZ, Sameer AS and Nissar S:

Pathophysiology of diabetes: An overview. Avicenna J Med.

10:174–188. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sobeh M, Youssef FS, Esmat A, Petruk G,

El-Khatib AH, Monti DM, Ashour ML and Wink M: High resolution

UPLC-MS/MS profiling of polyphenolics in the methanol extract of

Syzygium samarangense leaves and its hepatoprotective

activity in rats with CCl4-induced hepatic damage. Food

Chem Toxicol. 113:145–153. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Rehman K and Akash MSH: Mechanism of

generation of oxidative stress and pathophysiology of type 2

diabetes mellitus: How are they interlinked? J Cell Biochem.

118:3577–3585. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Rashid K and Sil PC: Curcumin enhances

recovery of pancreatic islets from cellular stress induced

inflammation and apoptosis in diabetic rats. Toxicol Appl

Pharmacol. 282:297–310. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Mardiah Zakaria FR, Prangdimurti E and

Damanik R: Anti-inflammatory of purple roselle extract in diabetic

rats induced by streptozotocin. Procedia Food Sci. 3:182–189.

2015.

|

|

35

|

Shen SC, Chang WC and Chang CL: Fraction

from wax apple [Syzygium samarangense (Blume) Merrill and

Perry] fruit extract ameliorates insulin resistance via modulating

insulin signaling and inflammation pathway in tumor necrosis factor

α-treated FL83B mouse hepatocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 13:8562–8577.

2012.

|

|

36

|

Zhang Y: Flavonoids as potential agents

for the treatment of diabetes and its complications. Molecules.

25(5646)2020.

|

|

37

|

Rendell MS: Current and emerging

gluconeogenesis inhibitors for the treatment of type 2 diabetes.

Expert Opin Pharmacother. 22:2167–2179. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|