Introduction

Approximately one-third of patients with

drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) suffer from a structural lesion that

can be treated surgically (1,2).

Identifying these lesions is important, as they often represent the

ictal onset zone. Epilepsy surgery targeting these lesions can lead

to a significant reduction in seizure frequency and improve quality

of life. Patients with lesions identified through magnetic

resonance imaging (MRI) were more likely to experience seizure

freedom following resection, highlighting the importance of imaging

in treatment planning (3). Even

when phase I presurgical evaluations yield concordant data, 30-50%

of surgical candidates still experience seizure recurrence

(4,5). Failure of epilepsy surgery for focal

epilepsy may be caused by insufficient excision of the

epileptogenic zone (EZ) or by inadequate disruption of pathogenic

hubs within the epileptogenic network (6).

An intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG) method

was developed by Penfield and Jasper in the 1930s. This method

involved placing electrodes directly on surgically exposed cortical

surfaces and recording brain activity before and after resection.

This process allowed the identification of the irritative zone as

well as the EZ intraoperatively (7). ECoG is particularly advantageous for

patients with neocortical lesions that cause temporal or

extratemporal epilepsy. This approach has been utilized in patients

with DRE stemming from either temporal or extratemporal tumors,

mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) and focal cortical dysplasia (FCD).

It can be utilized to prevent the need for long-term extraoperative

invasive electroencephalography (EEG) in carefully selected

individuals (8,9). However, it cannot replace the

presurgical phase I evaluation, as precise lateralization and

localization of the ictal onset zone or a strong hypothesis of the

EZ is necessary before performing ECoG.

ECoG effectiveness has been well documented in

high-resource settings, particularly across academic centers in

North America and Europe (9).

However, evidence from the Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMR),

including countries such as Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Jordan, and

Lebanon remains limited. This lack of data is concerning, as

healthcare systems in the EMR often face distinct challenges such

as restricted access to specialized epilepsy surgery programs,

disparities in diagnostic resources, and delayed referral (10). Moreover, existing studies from the

region are typically limited to small case series and rarely report

long-term seizure outcomes, making it difficult to assess the

broader utility and effectiveness of ECoG-guided surgical

interventions.

To address this gap, a retrospective analysis of

ECoG-guided epilepsy surgeries performed at a tertiary care center

in Saudi Arabia was conducted. The objective of the present study

was to fill this gap by assessing whether postresection ECoG

silence is predictive of Engel Class I outcomes.

Patients and methods

The present retrospective observational study

involved 30 patients with DRE who underwent ECoG-guided epilepsy

surgery as part of the comprehensive epilepsy program at King Fahad

Specialist Hospital in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, between January 2013

and December 2024. Patients with a minimum follow-up duration of 6

months were recruited. Clinical and demographic information, such

as sex, handedness, central nervous system examination, seizure

type, epilepsy duration, MRI findings, age at surgery, and

follow-up duration, were obtained. Participants with incomplete

data were excluded. The present study received ethics approval

(approval no. NEU0402) from the Ethics Committee of King Fahad

Specialist Hospital (Dammam, Saudi Arabia). Given the retrospective

nature of the study and the use of de-identified clinical data, the

requirement for patient consent for participation in the present

study was waived by the Ethics Committee of King Fahad Specialist

Hospital.

All patients underwent phase I presurgical

evaluation in the ABRET-accredited Epilepsy Monitoring Unit. The

patients were monitored with continuous noninvasive video EEG using

a 10-20 electrode placement system with additional left and right

anterior temporal T1 and T2 electrodes. On average, at least two

seizures were recorded. Preoperative imaging studies included 1.5

Tesla or 3 Tesla MRI scans. Lesions were categorized as temporal,

extratemporal, or both temporal and extratemporal. Patients with

normal MRI scans underwent advanced modalities, such as positron

emission tomography (PET) or single photon emission computed

tomography (SPECT) scans to localize or lateralize the EZ. All

patients were reviewed during the weekly multidisciplinary epilepsy

surgery care conference. Both the patients and their relatives were

informed about the need for EcoG, and written informed consent was

obtained.

All patients underwent the procedure under general

anesthesia. Anesthesia was induced with propofol at a dose of 2-3

mg/kg, fentanyl at 2 mcg/kg, and rocuronium at 0.5 mg/kg. After

intubation, arterial and peripheral lines were secured. An infusion

of remifentanil at a rate of 0.1-0.3 mcg/kg/min, in combination

with inhaled sevoflurane at 1 MAC, was used for anesthetic

maintenance. After 2021, due to a nationwide shortage, remifentanil

was replaced by dexmedetomidine infusion at a rate of 0.2-0.5

mcg/kg/h. Rocuronium at a dose of 0.2 mg/kg was given as needed,

especially before ECoG. During ECoG recordings, the sevoflurane

concentration was reduced to 0.2 MAC to decrease anesthesia levels.

The dexmedetomidine infusion at 0.2-0.5 mcg/kg/h and rocuronium at

0.2 mg/kg/dose were continued throughout the ECoG recording.

Sevoflurane was increased back to 1 MAC at the end of each ECoG

recording session. ECoG was performed during surgery to detect the

presence of interictal discharges (IEDs) and to assist in making

surgical decisions regarding the extent of resection of the EZ.

ECoG was conducted both before and after resection to monitor for

IEDs in the cortical areas and to help guide the surgeons in

achieving maximal or complete excision of the epileptogenic

regions. In total, four to six contact strip electrodes were

utilized for recording. Engel's classification method was used to

determine the outcomes of seizures (Class I-IV), with Class I

defined as completely seizure-free (11).

The data were summarized using descriptive

statistics, covering variables such as gender, age at surgery,

duration and type of seizures, lesion type identified on MRI,

surgical approach, pre- and post-resection ECoG findings,

histological results, as well as postoperative MRI and EEG

evaluations. A postoperative CT scan of the brain was performed on

all patients to assess complications such as hemorrhage,

infarction, and hydrocephalus. Post-operative MRI was performed

only if clinically necessary due to logistical constraints at King

Fahad Specialist Hospital (Dammam, Saudi Arabia). Due to the small

sample size, descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient

demographics and clinical outcomes, including means, medians, and

ranges for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages

for categorical variables. All analyses were performed using IBM

SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (IBM Corp.). No

multivariate analysis was performed due to sample size

limitations.

Results

In the present study, a total of 30 patients were

included, consisting of 16 males and 14 females. Of these, 26

patients were right-handed and 4 patients were left-handed. A total

of 28 patients had a normal neurological examination, while two had

right hemiparesis. In terms of seizure type, 15 patients had focal

to bilateral tonic-clonic seizures, 10 patients had focal unaware

seizures, 3 patients had focal aware seizures, 1 patient had a

generalized tonic-clonic seizure, and 1 patient had epileptic

spasms. The epileptogenic lesions were lateralized to the right

hemisphere in 12 patients and to the left hemisphere in 15

patients. In addition, 1 patient had bilateral lesions, and 2

patients had a normal MRI. In terms of localization, 18 patients

had a temporal lesion, 6 patients had extratemporal lesions, 4

patients had both temporal and extratemporal lesions, and 2

patients had a normal MRI. The mean duration of epilepsy prior to

surgery was 59.5 months. At the time of surgery, the mean age was

13.7 years. Following surgery, the mean follow-up duration was 45.9

months (Table I).

| Table IDemographic and clinical

characteristics of patients. |

Table I

Demographic and clinical

characteristics of patients.

| Categories | No. of patients

(N=30) | Percentage (%) of

patients |

|---|

| Sex | | |

|

Male | 16 | 53.3 |

|

Female | 14 | 46.6 |

| Handedness | | |

|

Right | 26 | 86.6 |

|

Left | 4 | 13.3 |

| CNS examination | | |

|

Normal | 28 | 93.3 |

|

Right

hemiparesis | 2 | 6.6 |

| Seizure type | | |

|

Focal to

bilateral tonic-clonic | 15 | 50 |

|

Focal

unaware | 10 | 33.3 |

|

Focal

aware | 3 | 10 |

|

Generalized

tonic-clonic | 1 | 3.3 |

|

Epileptic

spasms | 1 | 3.3 |

| Lesion lateralization

on MRI | | |

|

Right | 12 | 40 |

|

Left | 15 | 50 |

|

Bilateral | 1 | 3.3 |

|

Normal | 2 | 6.6 |

| Lesion localization

on MRI | | |

|

Temporal | 18 | 60 |

|

Extratemporal | 6 | 20 |

|

Both | 4 | 13.3 |

|

Normal

MRI | 2 | 6.6 |

| Mean (range) epilepsy

duration before surgery (months) | 59.5 (3-204) | |

| Mean (range) age at

surgery (years) | 13.7 (3-29) | |

| Mean (range)

follow-up duration (months) | 45.9 (7-120) | |

The most commonly observed pathologies were tumors,

MTS, and FCD. Detailed MRI characteristics are presented in

Table II. Of the 30 patients, 9

underwent lesionectomy alone: 6 had extratemporal lesions, 2 had

temporal lesions, and 1 patient had both temporal and extratemporal

lesions. A total of 19 patients underwent lesionectomy with

anterior temporal lobectomy (ATL), 1 patient underwent selective

amygdalohippocampectomy and another patient underwent a complete

right hemispherectomy. The surgical approach varied depending on

the location of the lesion, but the goal in all cases was to

achieve complete or maximal resection of the EZ (Table III). Histopathological analysis

confirmed the presence of tumors in 16 patients, accounting for

53.3% of those examined. The most common tumor types identified

were gangliogliomas (7 patients), dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial

tumors (4 patients) and astrocytomas (3 patients). In addition, 3

patients with tuberous sclerosis complex had cortical tubers. FCD

was identified in 9 patients, representing 30% of the cases, with 5

of them also exhibiting MTS. Gliosis was present in 5 cases, either

as an isolated finding or in combination with other pathologies

(Table SI).

| Table IIMRI characteristics of patients. |

Table II

MRI characteristics of patients.

| Lesion location | Lesion type | No. of patients |

|---|

| Temporal | MTS + FCD | 4 |

| | MTS + tumor | 1 |

| | MTS + gliosis | 1 |

| | Tumor | 8 |

| | Tumor + FCD | 4 |

| | FCD | 2 |

| | Gliosis | 2 |

| Extra-temporal | FCD | 2 |

| | Tumors | 3 |

| | Gliosis +

calcification | 1 |

| Both temporal

and | Gliosis | 1 |

| extra-temporal | FCD | 1 |

| Table IIIDetails of surgery. |

Table III

Details of surgery.

| Type of

surgery | Details | No. of

patients |

|---|

| Lesionectomy

alone | | 9 |

| | Temporal | 2 |

| | Extra-temporal | 6 |

| | Both | 1 |

| Lesionectomy

plus | | 21 |

| | Anterior temporal

lobectomy | 19 |

| | Selective

amygdalo-hippocampectomy | 1 |

| | Right

hemispherectomy | 1 |

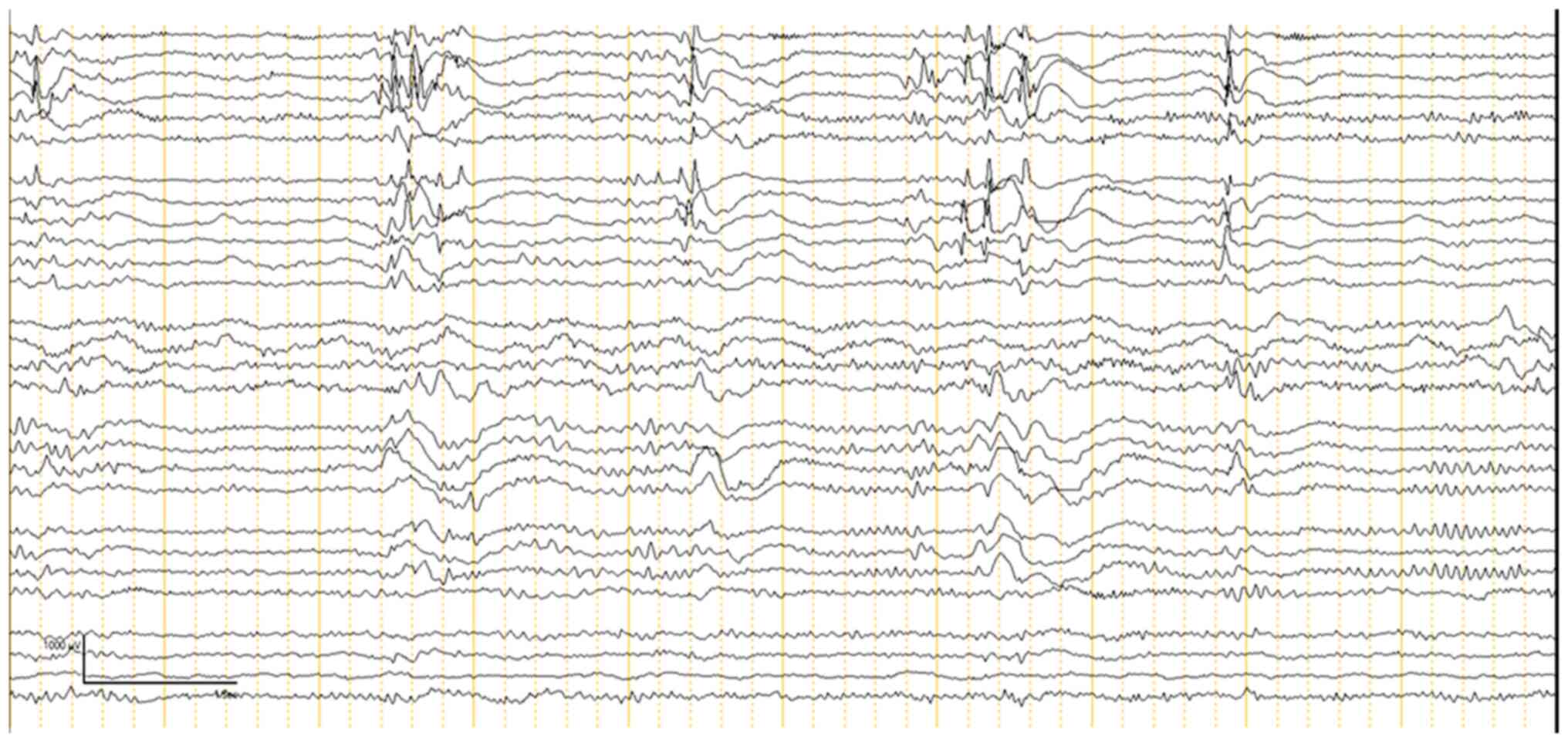

ECoG was performed on all 30 patients to guide the

extent of epileptogenic tissue resection. The ECoG findings were

categorized into two phases: Pre-resection (Fig. 1) and post-resection (Fig. 2). Pre-resection spikes were noted in

all 30 cases, indicating the presence of epileptogenic foci. The

most prominent spikes were found in areas identified by MRI as

locations of seizure focus localization. ECoG confirmed some cases

where more extensive resections were necessary due to the inability

of the previous MRI to show the full extent of the affected area.

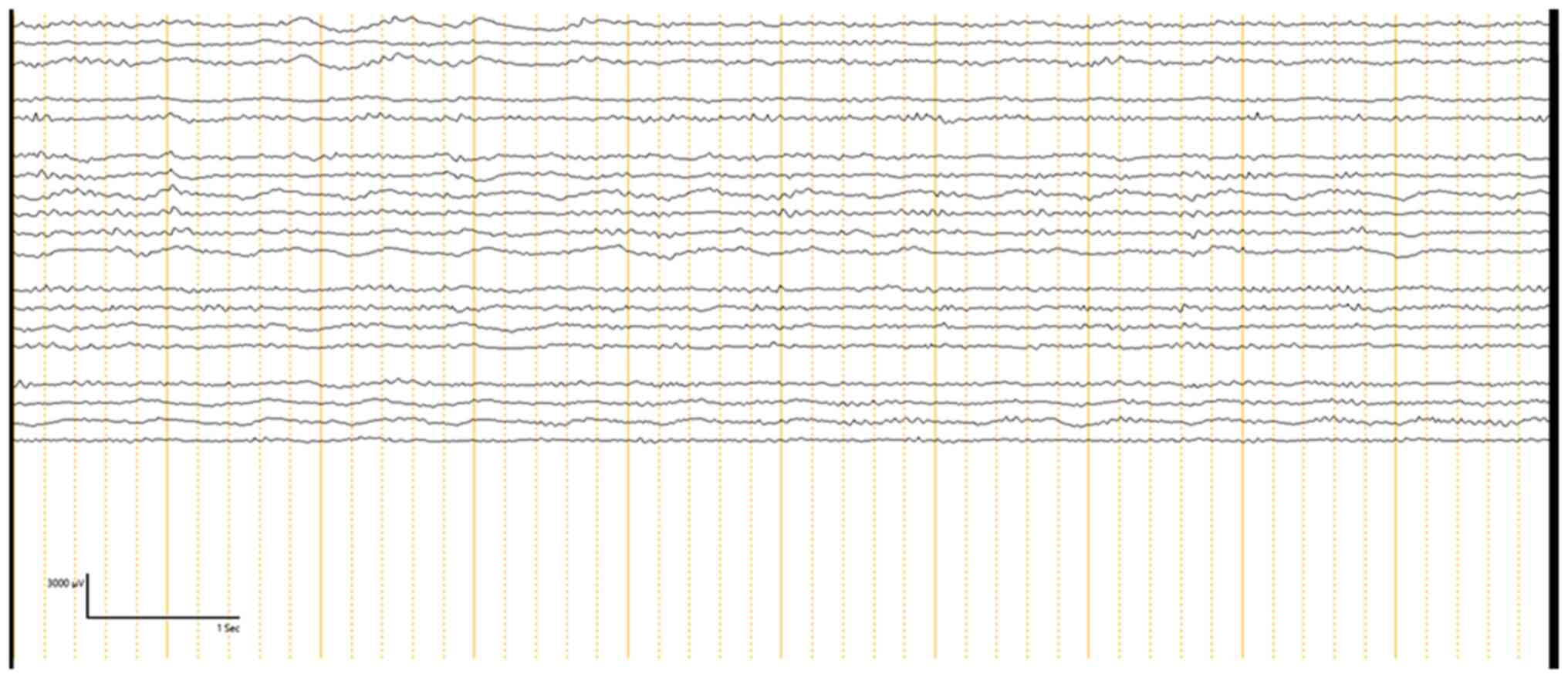

Following lesion resection, post-resection ECoG was conducted to

determine if any epileptogenic activity remained. Out of the 30

patients, 13 patients (43.3%) had no residual IEDs. These patients

were most likely to achieve seizure freedom post-operatively.

However, 17 patients (56.6%) showed attenuated spikes on

post-resection ECoG. In these cases, further resection was not

possible, either due to the proximity of the epileptogenic tissue

to eloquent brain areas or because the decision was made to

minimize the risk of neurological deficits. Among these patients, 5

achieved Engel's Class II or III seizure outcomes, while 3 patients

had Engel's Class IV outcomes, indicating persistent seizure

activity post-operatively (Tables

IV and V). Details of patients

who were seizure-free (Engel Class I) are presented in Table IV, while details of patients who

had Engel Class II-IV outcomes are presented in Table V. Of the patients that were

seizure-free, 5 patients were completely off anti-seizure

medications (ASMs), while 14 patients had their ASMs either tapered

or maintained at the same dose if 2 years of post-operative seizure

freedom had not yet passed (Table

IV). Patients who did not achieve seizure freedom continued on

ASMs with some adjustments.

| Table IVDetails of patients who achieved

seizure freedom (Engel Class I). |

Table IV

Details of patients who achieved

seizure freedom (Engel Class I).

| Serial no. | MRI | Post-resection IEDs

on iECoG | Histopathology | Type of

surgery | Post-op EEG | Post-op MRI |

|---|

| 1 | LT

occipital-parietal old infarction | Attenuated | Gliosis | Lesionectomy

alone | Abnormal | Not performed |

| 2 | RT frontal FCD | Absent | FCD IIB | Lesionectomy

alone | Not performed | Not performed |

| 3 | LT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | Ganglioglioma | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 4 | LT temporal lesion

+ MTS | Absent | Ganglioglioma +

MTS | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 5 | Multiple cortical

tubers (+ RT temporal) | Absent | Tuber + FCD

IIIB | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Not performed |

| 6 | LT hippocampal

atrophy | Absent | MTS + FCD IIIa | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Abnormal | Not performed |

| 7 | LT temporal

lesion | Absent | Ganglioglioma +

FCD | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Not performed | Complete

excision |

| 8 | LT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | Astrocytoma + FCD

IIIB | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 9 | RT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | Ganglioglioma +

FCD | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 10 | RT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | DNET | Lesionectomy

alone | Normal | Residual

lesion |

| 11 | LT temporal lesion

(incomplete previous resection) | Absent | Ganglioglioma | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Not performed | Complete

excision |

| 12 | LT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | Ganglioglioma | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 13 | RT temporal

lesion | Absent | Ganglioglioma + FCD

IIIB | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Not performed |

| 14 | Unremarkable | Attenuated | FCD | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | N/A |

| 15 | LT parietal

lesion | Absent | DNET | Lesionectomy

alone | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 16 | RT temporal

MTS | Attenuated | FCD Ia | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 17 | LT temporal

lesion | Absent | Astrocytoma | Lesionectomy

alone | Normal | Residual

lesion |

| 18 | RT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | Pleomorphic

xanthroastrocytoma | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Complete

excision |

| 19 | LT temporal

lesion | Absent | MTS + FCD IIIa | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Abnormal | Complete

excision |

| Table VDetails of patients not achieving

seizure freedom. |

Table V

Details of patients not achieving

seizure freedom.

| No. | MRI | Post-resection IEDs

ECoG | Histopathology | Type of

surgery | Post-op EEG | Post-op MRI | Engel Class |

|---|

| 1 | LT temporal

FCD | Absent | MTS + FCD IIIa | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Abnormal | Complete

excision | Class II |

| 2 | RT frontal gyrus

rectus FCD | Attenuated | MTS + FCD IIIa | Lesionectomy

alone | Abnormal | Residual

lesion | Class IV |

| 3 | LT temporal

MTS | Attenuated | MTS + FCD IIIa | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Abnormal | Not performed | Class III |

| 4 | RT inferior frontal

lesion | Absent | DNET | Lesionectomy

alone | Normal | Complete

excision | Class II |

| 5 | RT TPO

post-ischemic changes | Attenuated | Gliosis | RT

hemispherotomy | Abnormal | Residual

lesion | Class II |

| 6 | RT LV SEGA +

multiple tubers | Attenuated | Tubers | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Not performed | Class II |

| 7 | Unremarkable | Absent | MTS + gliosis | Lesionectomy +

SAH | Normal | Complete

excision | Class II |

| 8 | LT temporal

atrophy | Attenuated | Gliosis | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Abnormal | Residual

lesion | Class IV |

| 9 | RT temporal

occipital lesion | Attenuated | FCD | Lesionectomy

alone | Abnormal | Residual

lesion | Class IV |

| 10 | RT temporal

lesion | Attenuated | Gliosis | Lesionectomy +

ATL | Normal | Not performed | Class III |

| 11 | LT cingulate gyrus

lesion | Attenuated | DNET | Lesionectomy

alone | Normal | Residual

lesion | Class III |

Post-operative MRIs confirmed complete excision in

14 patients, with 7 patients showing residual lesions.

Post-operative MRIs were not performed for 9 patients. Of the

patients with residual lesions, 4 were classified as Engel's Class

III or IV (Tables IV and V). Post-operative EEG was normal in 18

patients (60%), while EEG abnormalities were associated with poorer

outcomes. In addition, 4 patients experienced transient

contralateral hemiparesis affecting gross motor function,

attributed to a lesion around the motor cortex, which resolved in 3

to 4 weeks. No other neurological deficits were observed in the

remaining patients, indicating overall favorable neurological

outcomes in this cohort.

Discussion

The present study examined the role of ECoG in

guiding epilepsy surgery and predicting seizure outcomes in a

cohort of patients with DRE. The findings demonstrated the utility

of ECoG in aiding resection decisions, especially in achieving

seizure freedom for the majority of patients, with 63.3% achieving

Engel Class I outcomes, indicating complete seizure freedom.

The results are consistent with previous studies

regarding the role of ECoG in identifying EZs and guiding resection

to achieve seizure freedom. The absence of IEDs on post-resection

ECoG was associated with Engel Class I outcomes in 13 patients

(43.3%), aligning with findings from Ravat et al (12) and Greiner et al (13), which highlight the predictive value

of the absence of IEDs for positive postoperative results. ECoG

enabled adjustments to the extent of resection during surgery,

helping to reduce seizure recurrence, particularly for patients

with temporal lesions, which were the most common pathology in the

present cohort.

The high incidence of temporal lobe pathologies,

such as MTS and FCD, highlights the surgical challenge of complete

resection, particularly when lesions are near eloquent areas. In

these instances, a decrease rather than total absence of

post-resection ECoG IEDs often indicates worse outcomes (Engel

Classes II-IV). This is in line with findings from studies by

Sugano et al (14) and

Fernandez and Loddenkemper (15),

which showed that persistent spikes in ECoG were associated with

lower rates of seizure freedom. The pre-resection ECoG identified

epileptogenic activity in all patients, offering valuable insights

into delineating the boundaries of the EZ, particularly when MRI

results are inconclusive (16,17).

Among patients who did not achieve complete absence of IEDs on

ECoG, 56.6% exhibited reduced spikes after resection. This subset

had lower rates of seizure freedom, with some falling into Engel

Class II-IV categories. These findings emphasize the significance

of striving for maximal resection while ensuring safety, as

residual epileptogenic activity tends to correlate with less

favorable seizure outcomes.

According to the present findings, the majority of

lesions were located in the temporal lobe, with MTS, FCD, and

tumors being the most common pathologies. These types of lesions

often require extensive resection, especially in cases of MTS or

FCD where the EZ may extend beyond the visible lesion. Consistent

with other studies, patients with tumors or FCD were more likely to

have epileptogenic activity beyond the lesion itself, highlighting

the importance of performing ECoG to determine the extent of

resection (12,18,19).

In the subgroup of patients who underwent ATL in addition to

lesionectomy, seizure freedom was achieved more frequently than in

patients undergoing lesionectomy alone, demonstrating the

effectiveness of combined surgical methods.

Post-operative MRI findings in the present study

underscored the critical role of imaging in evaluating surgical

success and its impact on seizure outcomes. Complete resection of

epileptogenic lesions, achieved in 14 patients (46%), was strongly

linked to favorable outcomes, with all patients attaining Engel

Class I or II status indicating significant seizure control or

freedom. These results emphasize the importance of MRI in

confirming lesion removal and establishing a foundation for ongoing

care and monitoring. By contrast, residual lesions were identified

in 7 patients, of whom 4 experienced persistent or recurrent

seizures (Engel Class III or IV). This highlights the imperative of

maximizing lesion resection to optimize seizure control, while

carefully managing the risks of neurological deficits, particularly

in cases involving lesions near eloquent brain areas.

The post-operative EEG findings further reinforced

the significance of thorough resection. Among the patients, 18

(60%) exhibited normal EEG patterns post-surgery, strongly

associated with improved seizure outcomes. However, persistent IEDs

were observed in 4 patients, aligning with poorer seizure control.

These findings are consistent with prior research highlighting the

predictive value of EEG in postoperative evaluations (20,21).

By detecting residual epileptogenic activity, EEG serves as a

crucial tool for identifying patients at risk of seizure recurrence

and guiding the need for additional therapeutic strategies.

Together, post-operative MRI and EEG offer a complementary

approach, providing a comprehensive framework to predict and

enhance surgical outcomes in epilepsy care.

Additional research is needed to explore advanced

ECoG techniques, such as high-resolution grid electrodes to improve

the accuracy of localizing EZs. Combining ECoG with novel imaging

tools such as PET or functional MRI in future studies could enhance

the precision of EZ localization, particularly in cases of

extratemporal epilepsy. Establishing a stronger association between

ECoG results and histopathological findings could guide tailored

surgical strategies based on specific lesion types. The present

study provides evidence supporting the effectiveness of

intraoperative ECoG in improving surgical outcomes for patients

with DRE. The observed seizure freedom rates align with those

reported in high-income countries, highlighting the feasibility and

value of ECoG-guided resections even at local healthcare

systems.

This research addresses a significant gap in the

literature by contributing long-term outcome data from the EMR

(Saudi Arabia), where epilepsy remains highly prevalent, yet access

to surgical care is often restricted. Unlike Western centers with

established surgical pathways and monitoring protocols,

institutions in our region commonly face challenges such as limited

specialist availability, low public awareness, and delayed

referrals (22-24).

The retrospective design of the present study

introduces limitations, including potential recall and

documentation bias, as data were collected from existing medical

records rather than prospectively. The single-center setting and

small sample size may also limit the external validity and

generalizability of the findings to broader populations.

Post-operative MRI was not obtained in almost a third of the

patients due to logistical constraints. This missing data may

introduce selection bias and limit the strength of conclusions

drawn regarding the association between the extent of resection and

seizure outcomes. Future research should aim for prospective,

multicenter studies with standardized follow-up protocols and

multidimensional outcome assessments to enhance the robustness and

applicability of findings.

Supplementary Material

Histological details of patients.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was funded by King Salman Center For

Disability Research (grant no. KSRG-2024-307).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

AA and ZMA contributed equally to data collection

and initial manuscript drafting. RAB and AM provided clinical

expertise and interpretation of findings and data. TJ, AN, FA, MF,

BH and SB contributed to data analysis and manuscript revision. FA

and MF assisted with literature review and data verification. AM

conceptualized the study, supervised the project, and finalized the

manuscript. AA and AM confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study received ethics approval (approval

no. NEU0402) from the Ethics Committee of King Fahad Specialist

Hospital (Dammam, Saudi Arabia). Given the retrospective nature of

the study and the use of de-identified clinical data, the

requirement for patient consent for participation was waived by the

Ethics Committee of King Fahad Specialist Hospital.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Bell GS and Sander JW: The epidemiology of

epilepsy: The size of the problem. Seizure. 10:306–314.

2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Dwivedi R, Ramanujam B, Chandra PS, Sapra

S, Gulati S, Kalaivani M, Garg A, Bal CS, Tripathi M, Dwivedi SN,

et al: Surgery for drug-resistant epilepsy in children. N Engl J

Med. 377:1639–1647. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Guo J, Guo M, Liu R, Kong Y, Hu X, Yao L,

Lv S, Lv J, Wang X and Kong QX: Seizure Outcome after surgery for

refractory epilepsy diagnosed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron

emission tomography (18F-FDG PET/MRI): A systematic review and

Meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 173:34–43. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Engel J Jr, McDermott MP, Wiebe S,

Langfitt JT, Stern JM, Dewar S, Sperling MR, Gardiner I, Erba G,

Fried I, et al: Early surgical therapy for drug-resistant temporal

lobe epilepsy. JAMA. 307:922–930. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Harroud A, Bouthillier A, Weil AG and

Nguyen DK: Temporal lobe epilepsy surgery failures: A review.

Epilepsy Res Treat. 2012(201651)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nair DR, Mohamed A, Burgess R and Lüders

H: A critical review of the different conceptual hypotheses framing

human focal epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 6:77–83. 2004.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Penfield W and Jasper H: Epilepsy and the

functional anatomy of the human brain. Boston, Little, Brown &

Co., Boston MA, pp363-365, 1954.

|

|

8

|

Tripathi M, Garg A, Gaikwad S, Bal CS,

Chitra S, Prasad K, Dash HH, Sharma BS and Chandra PS:

Intra-operative electrocorticography in lesional epilepsy. Epilepsy

Res. 89:133–141. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Yang T, Hakimian S and Schwartz TH:

Intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG): Indications,

techniques, and utility in epilepsy surgery. Epileptic Disord.

16:271–279. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

World Health Organization (WHO): Epilepsy

in the WHO Eastern Mediterranean Region. WHO Regional Office for

the Eastern Mediterranean, Cairo, 2010. https://applications.emro.who.int/dsaf/dsa1039.pdf.

|

|

11

|

Engel J Jr: Outcome with respect to

epileptic seizures. In: Surgical Treatment of the Epilepsies. Engel

J Jr (ed). 2nd edition. Raven Press, New York, NY, pp609-621,

1993).

|

|

12

|

Ravat S, Iyer V, Panchal K, Muzumdar D and

Kulkarni A: Surgical outcomes in patients with intraoperative

Electrocorticography (EcoG) guided epilepsy surgery-experiences of

a tertiary care centre in India. Int J Surg. 36:420–428.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Greiner HM, Horn PS, Tenney JR, Arya R,

Jain SV, Holland KD, Leach JL, Miles L, Rose DF, Fujiwara H and

Mangano FT: Preresection intraoperative electrocorticography (ECoG)

abnormalities predict Seizure-onset zone and outcome in pediatric

epilepsy surgery. Epilepsia. 57:582–589. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Sugano H, Shimizu H and Sunaga S: Efficacy

of intraoperative electrocorticography for assessing seizure

outcomes in intractable epilepsy patients with temporal-lobe-mass

lesions. Seizure. 16:120–127. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Fernández IS and Loddenkemper T:

Electrocorticography for seizure foci mapping in epilepsy surgery.

J Clin Neurophysiol. 30:554–570. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chiba R, Enatsu R, Kanno A, Tamada T,

Saito T, Sato R and Mikuni N: Usefulness of intraoperative

electrocorticography for the localization of epileptogenic zones.

Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 63:65–72. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Peng SJ, Wong TT, Huang CC, Chang H, Hsieh

KL, Tsai ML, Yang YS and Chen CL: Quantitative analysis of

intraoperative electrocorticography mirrors histopathology and

seizure outcome after epileptic surgery in children. J Formos Med

Assoc. 120:1500–1511. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Goel K, Pek V, Shlobin NA, Chen JS, Wang

A, Ibrahim GM, Hadjinicolaou A, Roessler K, Dudley RW, Nguyen DK,

et al: Clinical utility of intraoperative electrocorticography in

epilepsy surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsia.

64:253–265. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Pilcher WH, Silbergeld DL, Berger MS and

Ojemann GA: Intraoperative electrocorticography during tumor

resection: Impact on seizure outcome in patients with

gangliogliomas. J Neurosurg. 78:891–902. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Jehi L, Yardi R, Chagin K, Tassi L, Russo

GL, Worrell G, Hu W, Cendes F, Morita M, Bartolomei F, et al:

Development and validation of nomograms to provide individualised

predictions of seizure outcomes after epilepsy surgery: A

retrospective analysis. Lancet Neurol. 14:283–290. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Téllez-Zenteno JF, Hernández-Ronquillo L,

Moien-Afshari F and Wiebe S: Surgical outcomes in lesional and

non-lesional epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis.

Epilepsy Res. 89:310–318. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Benamer HT and Grosset DG: A systematic

review of the epidemiology of epilepsy in Arab countries.

Epilepsia. 50:2301–2304. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Idris A, Alabdaljabar MS, Almiro A,

Alsuraimi A, Dawalibi A, Abduljawad S and AlKhateeb M: Prevalence,

incidence, and risk factors of epilepsy in Arab countries: A

systematic review. Seizure. 92:40–50. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Alfayez SM and Aljafen BN: Epilepsy

services in Saudi Arabia. Quantitative assessment and

identification of challenges. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 21:326–330.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|