Introduction

5-Fluorouracil (5-FU) is a key chemotherapeutic

agent in colorectal cancer (CRC) treatment, primarily acting by

inhibiting thymidylate synthase, which disrupts DNA synthesis, and

by incorporating toxic metabolites into RNA to impair cell

functions (1). Its efficacy is

enhanced in combination regimens such as leucovorin, 5-FU and

oxaliplatin) and FOLFIRI (leucovorin, 5-FU, and Irinotecan), often

alongside leucovorin, stabilizing its cytotoxic effects (2). Despite its effectiveness, 5-FU

treatment is frequently limited by resistance mechanisms and

adverse effects, such as myelosuppression and gastrointestinal

toxicity, highlighting the importance of biomarkers and

personalized strategies to predict treatment response and mitigate

side effects (3).

Advances in pharmacogenomics and combinatorial

approaches continue to refine the use of 5-FU, offering improved

outcomes for patients with CRC (4).

The efficacy and safety of 5-FU are notably influenced by

interindividual variability in drug metabolism, largely attributed

to genetic polymorphisms in the dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

(DPYD) gene, which encodes dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

(DPD), the key enzyme responsible for 5-FU catabolism (5). Deficient or decreased DPD activity,

caused by DPYD polymorphisms such as DPYD 85T>C

and DPYD 1896T>C, leads to the accumulation of toxic 5-FU

metabolites, resulting in severe and sometimes fatal toxicity,

including neutropenia, diarrhea and mucositis (6,7).

The three DPYD variants DPYD 85T>C,

DPYD 1627A>G, and DPYD 1896T>C are relatively

more prevalent in East and Southeast Asian populations compared

with European risk alleles such as DPYD*2A

(c.1905+1G>A) and DPYD 13 (c.1679T>G) (8). Previous pharmacogenetic studies,

including analyses in Thai cohorts and population databases, have

consistently demonstrated higher allele frequencies for these

variants in Asian populations (9,10).

Each variant has potential functional relevance: DPYD

85T>C is associated with decreased DPD enzymatic activity and

variable risk of fluoropyrimidine-related toxicity; DPYD

1627A>G represents a missense substitution with conflicting

reports on its functional consequences but occurs at a relatively

high frequency in Asian populations and DPYD 1896T>C has

been observed in patients with severe 5-FU-induced toxicity,

suggesting its role as a putative risk allele (6,7,11).

Finally, these variants are not currently incorporated into

international dosing guidelines such as those issued by the

Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (4,12).

However, evidence (9,10) indicates that they may hold clinical

value in non-European populations, thereby justifying further

investigation.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs or miRs) are small non-coding RNAs

~22 nucleotides in length. miRNAs regulate gene expression at the

post-transcriptional level by mRNA degradation or translational

inhibition (13). The key roles of

miRNAs involve several biological processes such as cell

proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis (14). The aberrant expression of miRNAs has

been investigated in various cancer types and related to drug

resistance (15-17).

Circulating miRNAs may be a non-invasive biomarker for diagnosing

and predicting disease progression (18). Ferracin et al (19) found that miR-21-5p expression is

high in the plasma of patients with CRC patients. A previous study

also showed that miR-145, miR-106a and miR-17-3p were significantly

differentially expressed between patients with pre- and

post-operative stage II/III CRC. High levels of miR-17-3p and

miR-106a are associated with shorter disease-free survival,

suggesting they may serve as serum-miRNA-based biomarkers for

prognosis and predicting disease recurrence in patients with stage

II/III CRC (20). In addition,

recent studies have identified altered expression of other miRNAs

in patients with CRC patients, including upregulation of miR-374a

in both plasma and tumor tissues (21), as well as specific miRNA signatures

in saliva and lymphatic samples, which may serve as non-invasive

diagnostic biomarkers and help identify patients at high risk of

lymph node metastasis (22,23). Offer et al (24) demonstrated that miR-27a and miR-27b

may be pharmacological modulators of hepatic DPD enzyme function.

DPD is an important enzyme in the uracil catabolic pathway

converting the anti-cancer drug 5-FU to the inactive metabolite

5-dihydrofluorouracil. Deficiency of DPD resulting from inadequate

expression or deleterious variants in DPYD is associated

with severe toxic responses to 5-FU (24).

Moreover, patients who are heterozygous for miR-27a

SNV (rs895819) have an increased risk of fluoropyrimidine toxicity,

which was investigated in both DPYD wild-type and

DPYD variant carriers (25).

This suggests that miR-27a rs895819 may serve as a biomarker for

fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity prediction. Previous studies

have predominantly focused on common DPYD variants observed

in European populations, such as DPYD 2A (c.1905+1G>A),

DPYD 13 (c.1679T>G), and HapB3 (c.1236G>A),

which are well-established markers of fluoropyrimidine toxicity

(8,26). To the best of our knowledge, few

studies (24,25) have concurrently assessed germline

DPYD polymorphisms alongside miRNA expression profiles to

investigate their combined impact on 5-FU toxicity. The present

study aimed to determine the miRNA expression profiles in the

DPYD variant (DPYD 85T>C and DPYD

1896T>C) in patients with CRC to facilitate use of miRNAs as

potential targets for predicting the toxicity of 5-FU and the

development of personalized patient profiles and therapeutic

interventions.

Materials and methods

Subjects

A total of 48 patients with CRC were recruited

between October 2020 and October 2023 at the Division of Oncology,

Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand. The

mean age was 64.7±11.9 years, ranging from 18-90 years. Among the

48 patients 28 (58.3%) were male and 20 (41.7% were female.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: CRC confirmed histologically or

cytologically; age ≥18 years; no previous treatment with 5-FU;

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) (27) performance status of 0-2; life

expectancy >3 months; white blood cell,

4.5-11.0x109/l; hemoglobin, 13.2-16.6 g/dl for male

patients and 11.6-15.0 g/dl for female patients; neutrophil count

<1.5x109/l; platelet count <8x1010/l

and serum creatinine <1.5 mg/dl. Exclusion criteria were

pregnancy and any laboratory evidence of renal or hepatic

abnormality.

The present study was carried out in compliance with

the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of

Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University, Thailand (approval no.

MURA2020/1613 Ref.2419). The study procedure was explained to the

patients before the study andall patients signed the consent form

to participate in the study.

Molecular analysis

EDTA blood samples were collected to perform DNA

extraction using MagNA Pure Compact System (Roche Diagnostics

GmbH). TaqMan® real-time (RT)PCR ViiA7™

system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was

used to detect three DPYD variants: DPYD 85T>C

(rs1801265, cat. no. C_9491497_10), DPYD 1627 A>G

(rs1801159, cat. no. C_1823316_20) and DPYD 1896T>C

(rs17376848, cat. no. C_25471727_20). All reagents were obtained

from Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., and used

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Toxicity assessment

The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

(CTCAE) v5.0(28) was used to

evaluate toxicity at first and second cycles of treatment. The

hematological toxicity included leukopenia, neutropenia,

thrombocytopenia and anemia. Grade 1-4 was regarded as

toxicity.

miRNA extraction and cDNA

synthesis

Plasma samples from patients with CRC were used for

miRNA extraction. Prior to extraction, plasma was centrifuged at

1,107 x g for 15 min at room temperature. Following the

manufacturer's protocol, 100 µl plasma was processed using the

miRNeasy® Serum/Plasma kit (cat. no. 217184; Qiagen

GmbH) for miRNA isolation. The RNA concentration was measured using

a NanoDrop 2000/2000c Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). To synthesize cDNA, 200 ng RNA was used with the miRCURY

LNA™ RT kit (cat. no. 339340; Qiagen GmbH). The reaction

mixture included 5X miRCURY SYBR Green RT reaction buffer, 10X

miRCURY RT enzyme mix, Uni Sp6 RNA spike-in and the RNA template.

The reverse transcription reaction was performed in a thermal

cycler at 42˚C for 60 min, followed by enzyme inactivation at 95˚C

for 5 min and a final hold at 4˚C. cDNA was then stored at -20˚C

until further use.

miRNA array

The miRNA expression profiles were analyzed using

RT-PCR with a customized miRNA array panel (cat. no. 217184; Qiagen

GmbH) coated with specific primers for 43 miRNAs (sequences not

provided) involved in the 5-FU metabolic pathway. miR target

sequences are listed in Table SI.

The reactions were performed using the miRCURY LNA™ SYBR

Green PCR kit (cat. no. 339345, Qiagen GmbH). cDNA was diluted to

1:80 before mixing in the reaction containing 2X miRCURY SYBRGreen

mix and nuclease-free water. The 96-well plate of the miRNA array

was subjected to RT-PCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; cat. no. CFX

96). Thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial heat

activation at 95˚C for 2 min, followed by 50 cycles of denaturation

at 95˚C for 10 sec and annealing/extension at 56˚C for 60 sec. The

relative miRNA expression was determined using the

2-ΔΔCq method (29). The

analysis of miRNA profiles was performed using the Qiagen web

portal at GeneGlobe (geneglobe.qiagen.com). Heatmaps were generated using

the GeneGlobe platform (geneglobe.qiagen.com/th, which applies an unsupervised

clustering algorithm. Unsupervised clustering groups both samples

and genes based on the similarity of their expression patterns,

rather than relying on predefined group labels. This approach

minimizes bias introduced by prior assumptions. This method was

selected because it is widely regarded as a standard for gene

expression analysis and provides an unbiased visualization of

expression profiles (30,31).

Statistical analysis

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium of DPYD was

assessed using the χ2 test. Data were assessed for

normality of distribution. Descriptive statistics for patients were

presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for variables with a

normal distribution. The association between DPYD variants

status and the hematological toxicity was evaluated by Fisher's

exact test. All tests were performed using SPSS software version

21.0 (IBM Corp.). P-values were calculated using unpaired Student's

t-test for each miRNA. The test was performed as a parametric,

unpaired, two-sample t-test assuming equal variance with a

two-tailed distribution. The present study was designed as an

exploratory screen to identify candidate miRNAs for further

validation. Therefore, no multiplicity adjustment was performed.

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Patient demographics and clinical

data

A total of 48 patients were included in the present

study. The mean age was 64.7±11.9 years, with a male predominance

(58.3%, n=28 vs. 41.7%, n=20). Most patients had a performance

status, assessed by ECOG score, of 0 or 1, with a wide distribution

of primary tumor locations, including the rectum, sigmoid colon and

other sites across the colon. Metastases were most commonly

observed at sites other than the liver and lung (22.9%, n=11), with

the liver being the second most frequent site (18.8%, n=9). Tumors

were predominantly moderately differentiated (Table I).

| Table IPatient characteristics (n=48). |

Table I

Patient characteristics (n=48).

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|

| Mean age,

years | 64.7±11.9 |

| Sex (%) | |

|

Male | 28 (58.3) |

|

Female | 20 (41.7) |

| ECOG score (%) | |

|

0 | 21 (43.8) |

|

1 | 22 (45.8) |

|

2 | 5 (10.4) |

| Site of cancer

(%) | |

|

Ascending

colon | 5 (10.4) |

|

Transverse

colon | 3 (6.3) |

|

Descending

colon | 4 (8.3) |

|

Sigmoid

colon | 14 (29.2) |

|

Rectosigmoid | 5 (10.4) |

|

Rectum | 16 (33.3) |

|

Colon,

unspecified | 1 (2.1) |

| Site of metastasis

(%) | |

|

Liver | 9 (18.8) |

|

Lung | 3 (6.3) |

|

Liver and

lung | 2 (4.2) |

|

Other | 11 (22.9) |

|

No | 23 (47.9) |

| Histopathology

(%) | |

|

Well

differentiated | 11 (22.9) |

|

Moderately

differentiated | 36 (75.0) |

|

Poorly

differentiated | 1 (2.1) |

Genotypic and allelic frequencies of

DPYD variants

A total of three single nucleotide polymorphisms

(SNPs) in the DPYD gene were analyzed: 85T>C (rs1801265),

1627A>G (rs1801159), and 1896T>C (rs17376848). All three

variants were present in the study cohort, with genotype

distributions consistent with Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

For the DPYD 85T>C polymorphism, the

majority of individuals were homozygous wild-type (72.9%), while

27.1% were heterozygous; no homozygous variant carriers were

observed. The corresponding allele frequencies were 0.86 for the

wild-type allele and 0.14 for the variant allele.

For the DPYD 1627A>G variant, 70.8% of

subjects carried the homozygous wild-type genotype, 25.0% were

heterozygous, and 4.2% were homozygous for the variant allele,

yielding allele frequencies of 0.83 (wild-type) and 0.17

(variant).

Similarly, the DPYD 1896T>C polymorphism

demonstrated 72.9% homozygous wild-type, 27.1% heterozygous, and no

homozygous variant genotypes, corresponding to allele frequencies

of 0.86 and 0.14 for the wild-type and variant alleles,

respectively (Table II).

| Table IIDihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

genotype and allele frequency. |

Table II

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

genotype and allele frequency.

| | Genotype frequency

(%) | Allele

frequency |

|---|

| SNP | rs ID no. | wt/wt | wt/vt | vt/vt | wt | vt |

|---|

| 85T>C | 1801265 | 35 (72.9) | 13 (27.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.86 | 0.14 |

| 1627A>G | 1801159 | 34 (70.8) | 12 (25.0) | 2 (4.2) | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| 1896 T>C | 17376848 | 35 (72.9) | 13 (27.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.86 | 0.14 |

Association of DPYD variants with

hematological toxicity

Hematological toxicity, including anemia,

leucopenia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, were assessed for

their association with DPYD variants across two chemotherapy

cycles (Table III). DPYD

85T>C showed a trend toward increased anemia, particularly

during the second chemotherapy cycle. Although the difference was

not significant, this suggests a possible cumulative effect of the

variant on drug metabolism over time. By contrast, DPYD

1627A>G and DPYD 1896T>C were not associated with

increased anemia in either cycle.

| Table IIIDihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

variants and hematological toxicity. |

Table III

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase

variants and hematological toxicity.

| | First cycle | Second cycle |

|---|

| Toxicity | SNP | Genotype | n | Grade 0 (%) | Grade 1-4 (%) | P-value | Grade 0 (%) | Grade 1-4 (%) | P-value |

|---|

| Anemia | 85T>C | T/T | 35 | 19 (54.3) | 16 (45.7) | 0.371 | 21 (60.0) | 14 (40.0) | 0.070 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 5 (38.5) | 8 (61.5) | | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | |

| | 1627A>G | A/A | 34 | 18 (52.9) | 16 (47.1) | 0.492 | 17 (50.0) | 17 (50.0) | 0.626 |

| | | A/G or G/G | 14 | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | | 8 (57.1) | 6 (42.9) | |

| | 1896T>C | T/T | 35 | 17 (48.6) | 18 (51.4) | 0.727 | 18 (51.4) | 17 (48.6) | 0.873 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | | 7 (53.8) | 6 (46.2) | |

| Leucopenia | 85T>C | T/T | 35 | 28 (80.0) | 7 (20.0) | 0.446 | 27 (77.1) | 8 (22.9) | 0.064 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | | 13 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| | 1627A>G | A/A | 34 | 28 (82.4) | 6 (17.6) | >0.999 | 28 (82.4) | 6 (17.6) | >0.999 |

| | | A/G or G/G | 14 | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | |

| | 1896T>C | T/T | 35 | 27 (77.1) | 8 (22.9) | 0.64 | 29 (82.9) | 6 (17.1) | >0.999 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 13 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Neutropenia | 85T>C | T/T | 35 | 27 (77.1) | 8 (22.9) | 0.724 | 25 (71.4) | 10 (28.6) | 0.498 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | | 11 (84.6) | 2 (15.4) | |

| | 1627A>G | A/A | 34 | 26 (76.5) | 8 (23.5) | 0.724 | 25 (73.5) | 9 (26.5) | >0.999 |

| | | A/G or G/G | 14 | 12 (85.7) | 2 (14.3) | | 11 (78.6) | 3 (21.4) | |

| | 1896T>C | T/T | 35 | 26 (74.3) | 9 (25.7) | 0.280 | 26 (74.3) | 9 (25.7) | >0.999 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | | 10 (76.9) | 3 (23.1) | |

|

Thrombocytopenia | 85T>C | T/T | 35 | 33 (94.3) | 2 (5.7) | 0.583 | 28 (80.0) | 7 (20.0) | 0.446 |

| | | T/C | 13 | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

| | 1627A>G | A/G | 34 | 32 (94.1) | 2 (5.9) | >0.999 | 30 (88.2) | 4 (11.8) | 0.205 |

| | | A/G or G/G | 14 | 13 (92.9) | 1 (7.1) | | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | |

| | 1896T>C | A/A | 35 | 33 (94.3) | 2 (5.7) | 0.583 | 28 (80.0) | 7 (20.0) | 0.446 |

| | | A/G | 13 | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | | 12 (92.3) | 1 (7.7) | |

For leukopenia, a lower incidence was observed among

DPYD 85T>C variant carriers during the second cycle. This

was not statistically significant. No consistent associations were

found between DPYD 1627A>G or DPYD 1896T>C

variants and any of the evaluated toxicities, including neutropenia

and thrombocytopenia.

No significant associations were found between

DPYD variants and thrombocytopenia. The incidence of grade

1-4 thrombocytopenia was similar across DPYD 85T>C,

DPYD 1627A>G, and DPYD 1896T>C variants for

both cycles. A slightly higher prevalence of thrombocytopenia was

observed among A/G or G/G carriers of 1627A>G in the second

cycle (28.6%) compared with A/A carriers (11.8%), but this

difference was not statistically significant.

miRNA expression profiles associated

with DPYD 85T>C

miRNAs were extracted from plasma samples of nine

patients with CRC (five wild-type and four with the variant

DPYD 85T>C) using the miRNeasy® Serum/Plasma

kit. miRNA array was used to analyze 43 miRNAs related to the

DPYD drug-metabolizing gene. miRNAs were arranged by

unsupervised clustering, which organizes data according to

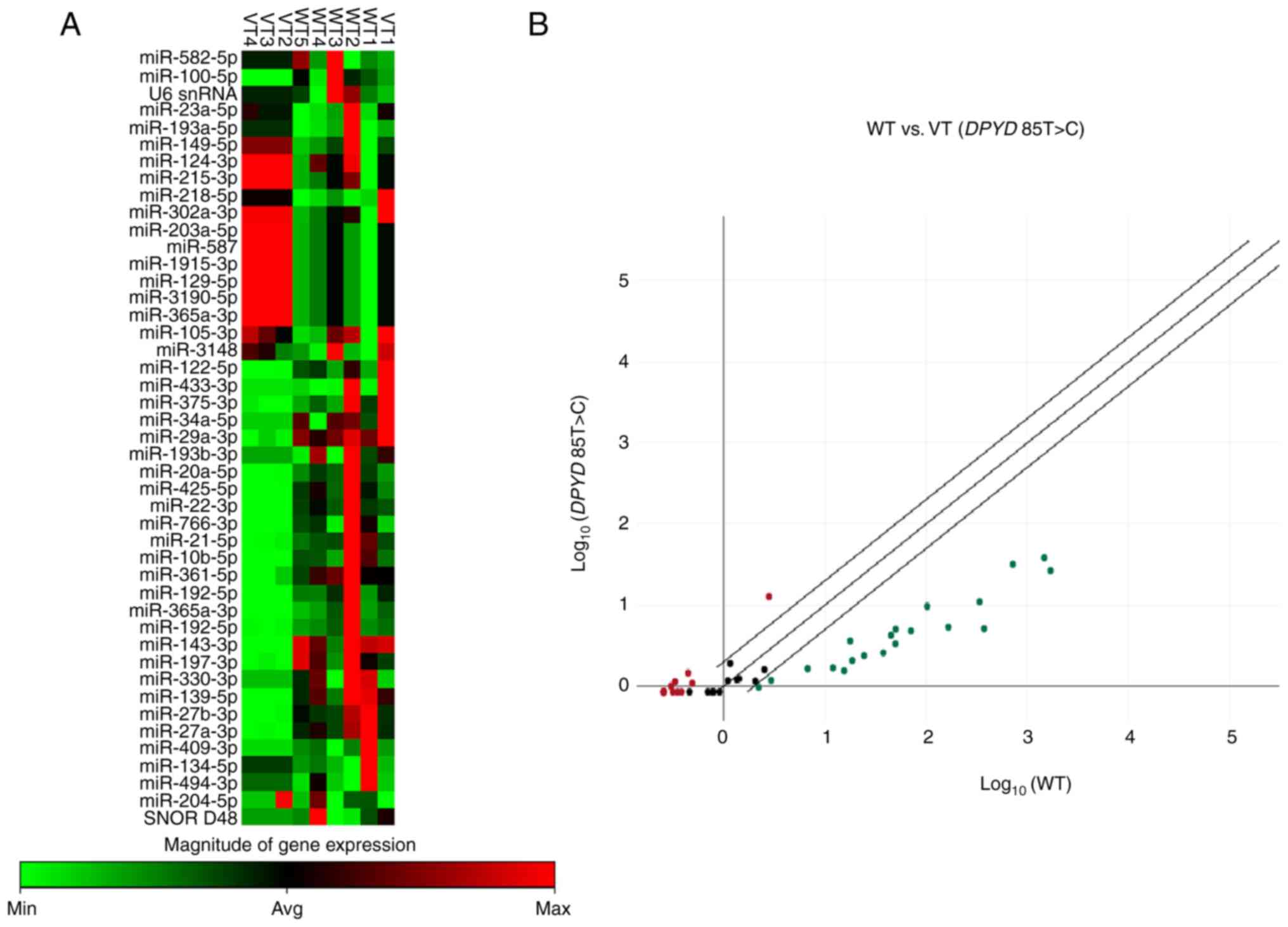

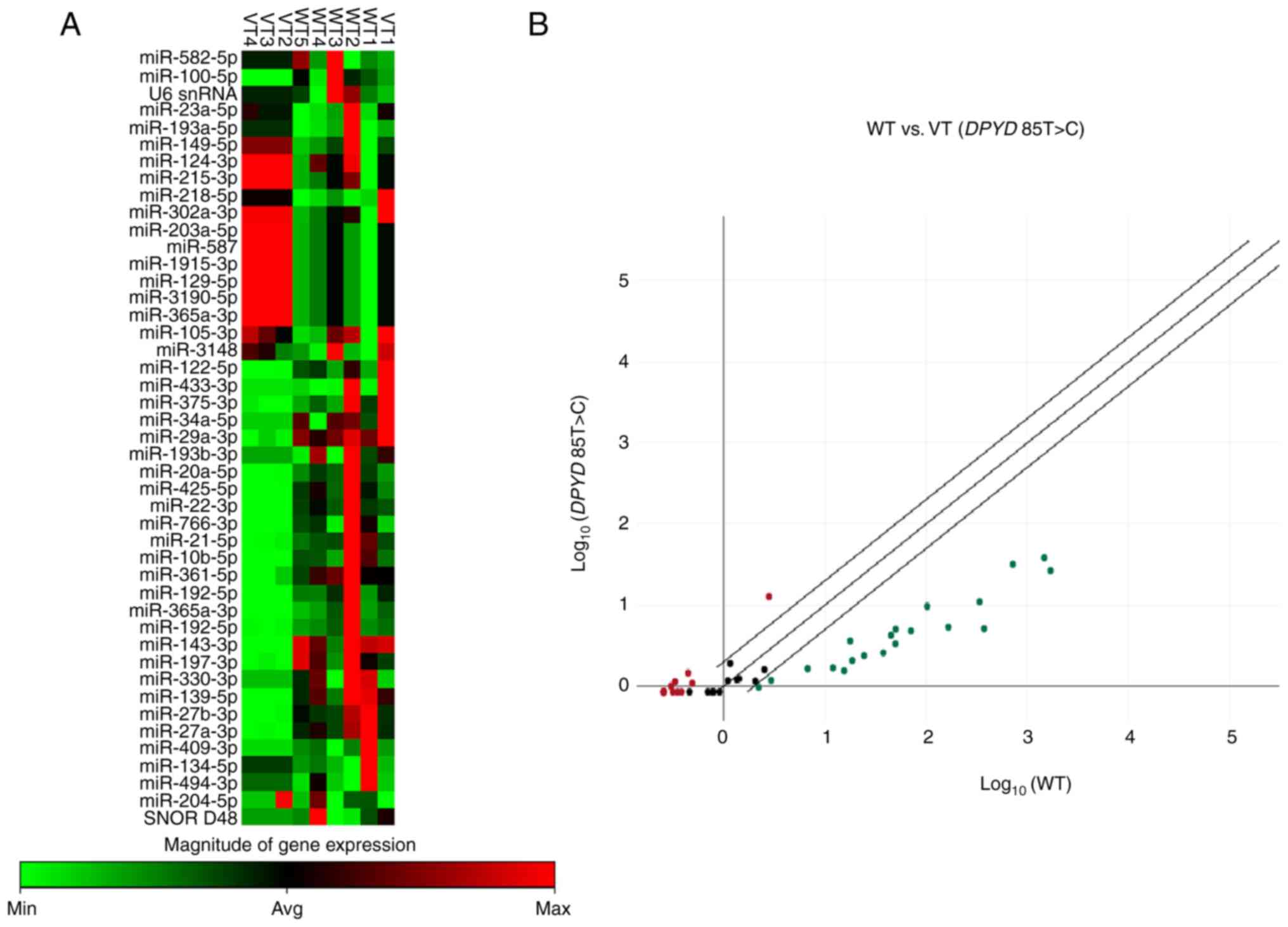

expression similarity (Fig. 1A).

This approach revealed natural groupings of WT and VT samples,

reflecting their underlying expression profiles. The results

demonstrated differential expression of miRNAs when comparing the

variant DPYD 85T>C with wild-type patients with CRC

(Fig. 1A). The scatter plot

demonstrated up- and downregulated miRNAs in variant vs. wild-type

patients, indicating a potential link between miRNA expression and

the DPYD gene polymorphism (Fig.

1B). There were nine up- and 11 downregulated miRNAs in the

variant DPYD 85T>C compared with the wild-type group

(Table IV).

| Figure 1miR expression profiles in patients

with VT (DPYD 85T>C) and WT colorectal cancer. A total of

43 miRs were detected in the plasma of patients with VT (n=4) and

WT colorectal cancer (n=5) using miR array. (A) Heat map of

differential expression of miRs in VT compared with WT colorectal

cancer. Red and green show up- and downregulation, respectively.

(B) Scatter plot showing miR profiles between VT and WT colorectal

cancer. Each dot represents the fold-change in expression of miRNA.

Red, green, and black dots represent up- and downregulated and

unchanged miRNAs, respectively. miR, microRNA; VT, Variant;

DPYD, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene; WT, Wild type;

min, minimum; avg, average; max, maximum; sn, small nuclear. |

| Table IVUp- and downregulated miRs in

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase 85T>C compared with patients

with wild-type colorectal cancer. |

Table IV

Up- and downregulated miRs in

Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase 85T>C compared with patients

with wild-type colorectal cancer.

| A, Upregulated

miRs |

|---|

| No. | miR | Fold-change | P-value |

|---|

| 1 | miR-218-5p | 3.44 | 0.001 |

| 2 | miR-203a-5p | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 3 | miR-215-3p | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 4 | miR-587 | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 5 | miR-1915-3p | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 6 | miR-129-5p | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 7 | miR-3190-5p | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 8 | miR-365a-3p | 3.35 | 0.003 |

| 9 | miR-302a-3p | 3.33 | 0.001 |

| B, Downregulated

miRs |

| No. | miR | Fold-change | P-value |

| 1 | miR-425-5p | -72.63 | 0.015 |

| 2 | miR-20a-5p | -63.79 | 0.039 |

| 3 | miR-21-5p | -38.30 | 0.042 |

| 4 | miR-27b-3p | -30.85 | 0.020 |

| 5 | miR-27a-3p | -30.45 | 0.015 |

| 6 | miR-22-3p | -22.59 | 0.031 |

| 7 | miR-197-3p | -14.96 | 0.017 |

| 8 | miR-361-5p | -10.53 | 0.019 |

| 9 | miR-766-3p | -10.01 | 0.045 |

| 10 | miR-139-5p | -8.92 | 0.045 |

| 11 | miR-10b-5p | -7.11 | 0.044 |

miRNA expression profiles associated

with DPYD 1896T>C

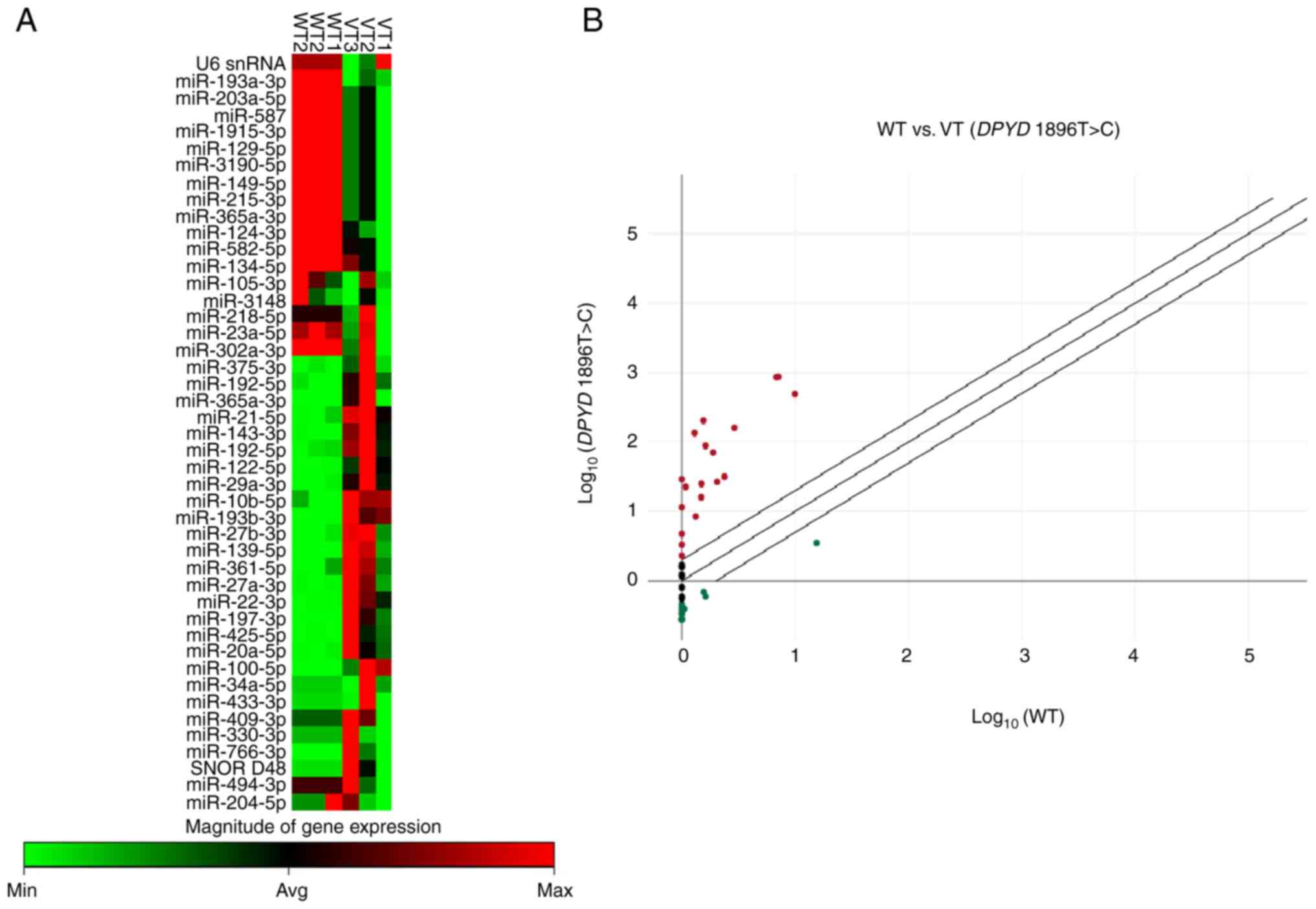

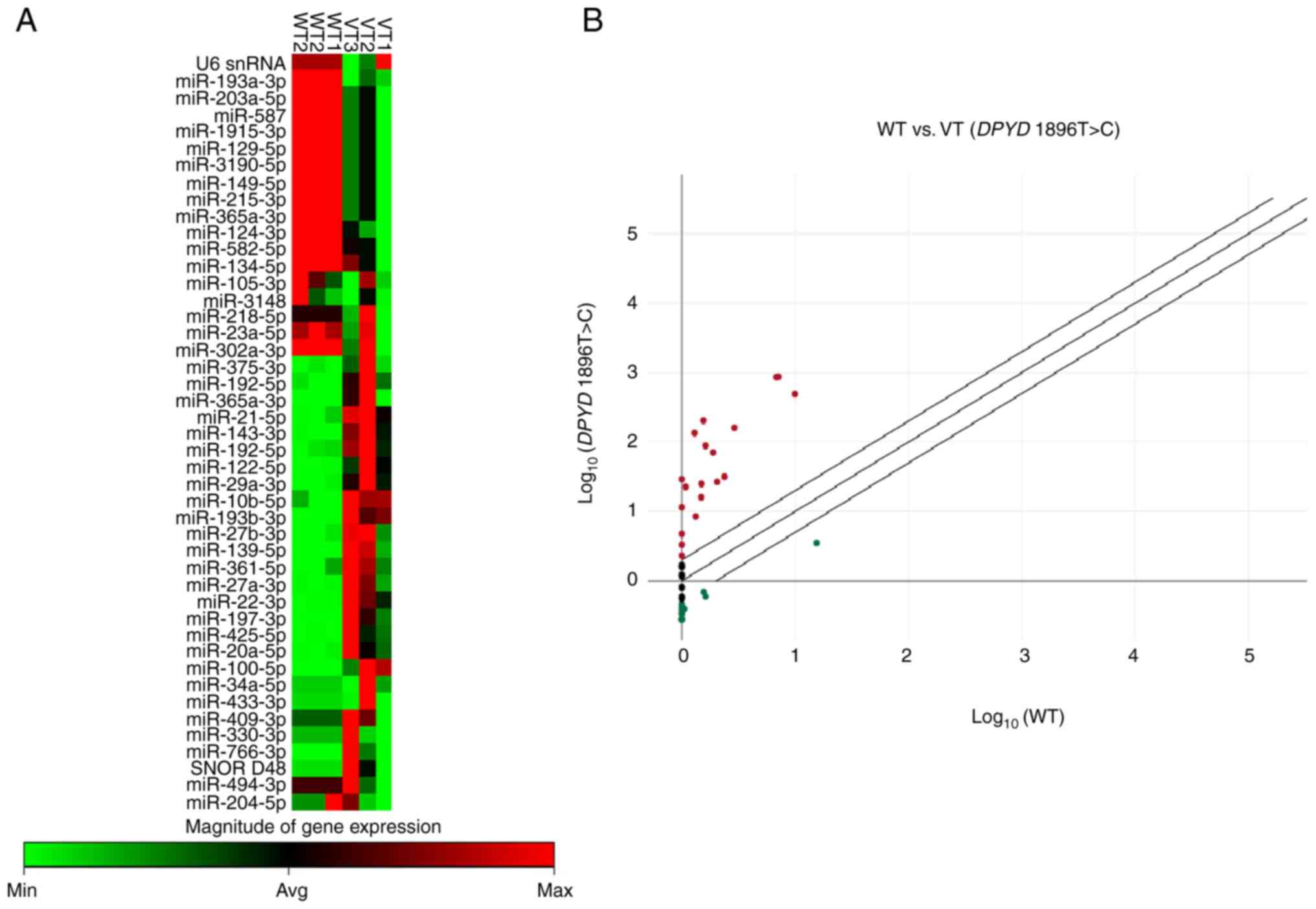

To assess the miRNA expression profiles in CRC

patients with the DPYD 1896T>C variant compared with

wild-type, miRNA was extracted from plasma samples of six patients

with CRC (three wild-type and three with the DPYD 1896T>C

variant). The results revealed differential miRNA expression

between the variant DPYD 1896T>C and wild-type patients

(Fig. 2A). The scatter plot

demonstrated both up- and downregulated miRNAs in the variant

compared with the wild-type group, suggesting a potential

association between these miRNAs and the DPYD 1896T>C

variant (Fig. 2B). There were five

up-and nine downregulated miRNAs in the variant group compared with

wild-type patients (Table V).

| Figure 2miRNA expression profiles in patients

with VT (DPYD 1896T>C) and WT colorectal cancer. A total

of 43 miRs were detected in the plasma of patients with (n=3) and

WT colorectal cancer (n=3). (A) Heat map of differential expression

of miRs in VT compared with WT colorectal cancer. Red and green

show up- and downregulation, respectively. (B) Scatter plot showing

miR profiles between VT and WT colorectal cancer. Each dot

represents the fold-change in expression of miRNA. Red, green, and

black dots represent up- and downregulated and unchanged miRNAs,

respectively. miR, microRNA; VT, Variant; DPYD,

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene; WT, Wild type; min, minimum;

avg, average; max, maximum; snRNA, small nuclear RNA. |

| Table VUp- and downregulated miRs in

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase 1896T>C compared with patients

with wild-type colorectal cancer. |

Table V

Up- and downregulated miRs in

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase 1896T>C compared with patients

with wild-type colorectal cancer.

| A, Upregulated

miRs |

|---|

| No. | miR | Fold-change | P-value |

|---|

| 1 | miR-21-5p | 122.32 | 0.028 |

| 2 | miR-22-3p | 49.31 | 0.049 |

| 3 | miR-143-3p | 20.91 | 0.043 |

| 4 | miR-10b-5p | 6.42 | <0.001 |

| 5 | miR-193b-3p | 2.31 | 0.016 |

| B, Downregulated

miRs |

| No. | miR | Fold-change | P-value |

| 1 | miR-587 | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 2 | miR-1915-3p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 3 | miR-129-5p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 4 | miR-3190-5p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 5 | miR-149-5p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 6 | miR-215-3p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 7 | miR-365a-3p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 8 | miR-203a-5p | -3.56 | 0.032 |

| 9 | miR-193a-3p | -2.37 | 0.010 |

miRNA profiling was performed on a randomly selected

subset of 16 patients. Among these, only two individuals had the

DPYD 1627A>G variant. Due to the very limited number of

variant carriers, statistical analysis of the association between

this SNP and miRNA expression as not conducted.

Discussion

DPYD encodes the enzyme DPD, which is

responsible for the catabolism of pyrimidine-based compounds,

including the chemotherapy drug 5-FU. Deficiency or reduced

activity of DPYD leads to the accumulation of 5-FU,

resulting in severe hematological toxicity, including neutropenia,

thrombocytopenia, anemia and leukopenia. Patients with partial DPD

deficiency have a 3.4-fold increased risk of developing grade IV

neutropenia compared with those with normal DPD activity (32,33).

Analysis of the DPYD gene in patients with grade IV

neutropenia revealed that 50% of the individuals tested were either

heterozygous or homozygous for the IVS14+1G>A mutation (34). In addition, the DPYD*5 gene

mutation leads to decreased DPD enzyme activity and impaired 5-FU

metabolism, which is associated with the accumulation of 5-FU and

increased chemotherapeutic toxicity in gastric and colon carcinoma

(35).

The present study assessed the association between

DPYD 85T>C, 1627A>G and 1896T>C and hematological

toxicity across two cycles of 5-FU-based chemotherapy in patients

with CRC. Recent analyses (8,36) have

demonstrated the relevance of DPYD variants in Asian

cohorts. For example, Chan et al (8) conducted a systematic review of

DPYD genotypes in non-European individuals with severe

fluoropyrimidine toxicity, identifying high-frequency variants

[c.1627A>G (DPYD*5) and c.85T>C

(DPYD*9A)] in East and Southeast Asian patients that are not

commonly included in European-focused genotyping panels. Similar to

present study, the frequency of DPYD 85T>C variant was 14% in

Thai patients with CRC. Among these, DPYD 85T>C showed a

trend toward increased anemia, especially during the second

chemotherapy cycle, with 69.2% of T/C carriers developing anemia

compared to 40.0% of T/T carriers (P=0.070). Although not

statistically significant, this trend suggests a possible

cumulative effect of the variant on drug metabolism and hematologic

toxicity. Previous studies (11,34,36)

have reported similar associations between DPYD variants and

hematological adverse effects. Patients with DPYD 85T>C

variant have a significantly increased risk of hematological

toxicity (11,35,37).

Detailleur et al (38) reported a high prevalence of the

DPYD 85T>C variant among patients who experienced severe

toxicity following treatment with 5-FU-based chemotherapy in a

retrospective study. Different DPYD polymorphisms confer

varying levels of residual DPD enzyme activity. For example, the

85T>C (DPYD*9A) variant is associated with a modest

reduction in DPD activity rather than complete loss, which may

explain the milder and variable toxicity profiles seen in certain

carriers (6,9).

The meta-analysis by Leung and Chan (10) revealed that the DPYD

1627A>G variant has a high allele frequency (>20%) in

patients from China, Korea, Japan and Thailand, while the

DPYD 1896T>C variant shows an allele frequency >14% in

Korean and Thai cohorts. The statistical power to detect

associations for both polymorphisms is >75%. Similar to present

study, the allele frequency was 17% in DPYD 1627A>G and

14% in DPYD 1896T>C. The DPYD c.1627A>G variant

is a SNP that results in a missense mutation, causing an

isoleucine-to-valine substitution at codon 543 (p.I543V) of the DPD

enzyme. Several studies have reported that it may influence DPD

enzymatic activity, particularly in compound heterozygous

individuals or in the presence of additional risk alleles (6,10).

The present study found that DPYD 1627A>G

and 1896T>C variants were not significantly associated with

anemia, neutropenia, leukopenia or thrombocytopenia in either

treatment cycle. He et al (9) reported that DPYD enzyme activity does

not differ significantly among carriers of the 85T>C (DPYD

9A), 1627A>G (DPYD 5) or 1896T>C variants.

miRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that regulate gene

expression by binding to the 3' untranslated region (UTR) of target

mRNAs, leading to mRNA degradation or inhibition of translation

(39). In drug metabolism, miRNAs

have been found to regulate a variety of enzymes involved in drug

processing, including cytochrome P450 and

UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (40).

Sun et al (41) reported

that miR-21, miR-215, miR-218, miR-326 and miR-328 are involved in

the regulation of 5-FU metabolic pathways, and their differential

expression is significantly associated with clinical outcomes and

survival in patients with CRC receiving fluoropyrimidine-based

adjuvant chemotherapy.

The present study compared the miRNA profiles of

wild-type and DPYD 85T>C and 1896T>C variants in

patients with CRC and revealed distinct miRNA profiles between

wild-type and variant patients, with different patterns of up- and

downregulation observed for each variant. Several miRNAs were

upregulated in the DPYD 85T>C variant, but downregulated

in the 1896T>C variant, including miR-587, miR-1915-3p,

miR-129-5p, miR-3190-5p, miR-215-3p, miR-365a-3p and miR-203a-5p.

By contrast, some miRNAs were upregulated in the 1896T>C variant

but downregulated in the 85T>C variant, such as miR-21-5p,

miR-22-3p and miR-10b-5p. This suggested that the regulation of

miRNAs varies across different DPYD variants, and the

expression of miRNAs may be influenced by genetic variants,

potentially modulating their target genes and cellular functions in

CRC, which may affect disease progression, treatment response and

toxicity. miR-21-5p was highly expressed in patients with the

DPYD 1896T>C variant, showing a 122-fold increase

compared with wild-type patients, suggesting its potential as a

diagnostic biomarker for DPYD 1896T>C. This finding

aligns with a previous study, which reported elevated miR-21-5p

levels in the serum of patients with CRC, with fluctuations

observed after surgery and recurrence (42). Moreover, miR-21-5p levels are

associated with TNM staging and lymph node metastasis, suggesting

that miR-21-5p may serve as an oncogene in CRC progression and a

valuable diagnostic biomarker (42). However, these observations warrant

further validation in a larger cohort to confirm their clinical

relevance.

Downregulation of miR-22-3p was observed in the

85T>C variant, which is consistent with previous studies

(43,44) showing that miR-22-3p is

downregulated in CRC and exerts antitumor effects. miR-22-3p

decreases the proliferative, invasive and migratory capacity of CRC

cells (43). Another study found

that low miR-22 in CRC tissue and metastatic cell lines correlated

with metastasis, advanced stage, and relapse, whereas ectopic

miR-22 inhibited CRC growth and metastasis (44). In the present study, miR-10b-5p was

also downregulated in DPYD 85T>C compared with wild-type

patients. The aforementioned study showed that miR-10b-5p is a

target of circular RNAs, such as circ_0021977. Additionally, p21

and p53 are potential target genes of miR-10b-5p (45). The circ_0021977/miR-10b-5p/p21/p53

axis suppresses CRC cell proliferation, migration and invasion,

suggesting its role in CRC progression (45). miR-587 contributes to drug

resistance by downregulating Protein Phosphatase 2, Regulatory

Subunit A, Beta (PPP2R1B), a subunit of the Protein Phosphatase 2

(PP2A) complex, which results in increased AKT activation and

enhanced 5-FU resistance through elevated X-linked Inhibitor of

Apoptosis Protein (XIAP) expression. Targeting the

miR-587/PPP2R1B/phosphorylated AKT/XIAP axis could offer

therapeutic strategies to overcome drug resistance in CRC (46). In the present study, miR-587 was

upregulated in patients with the 85T>C variant, which may be

associated with 5-FU resistance. This preliminary finding suggests

a possible role of miR-587 in CRC treatment and its relevance in

drug resistance, warranting further investigation in larger

cohorts. The present data also suggested that miR-1915-3p may be

upregulated in the 85T>C variant. This aligns with previous

report that exosomal delivery of miR-1915-3p can enhance the

chemotherapeutic efficacy of oxaliplatin in CRC cells by

suppressing epithelial-mesenchymal transition-promoting oncogenes,

such as 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase/fructose-2,6-bisphosphatase 3) and

USP2 (Ubiquitin-Specific Protease 2) (46). In addition, miR-129-5p was

downregulated in the 1896T>C variant. This is consistent with

previous research indicating that miR-129-5p is downregulated in

colon cancer tissue and miR-129-5p mimics suppress the

proliferation of colon cancer cells (48). However, further studies with larger

sample sizes are needed to confirm these observations.

The present study demonstrated an upregulation of

miR-3190-5p in the 85T>C variant while it was downregulated in

the 1896T>C variant compared with wild-type. To the best of our

knowledge, only one previous study has reported this miRNA in CRC

(48). miR-3190-5p regulates the

expression of ABCC4 (ATP-binding cassette sub-family C member 4) by

binding the 3' UTR of the ABCC4 gene, and this regulatory

effect is disrupted by the rs3742106 polymorphism (49). Additionally, miR-3190-5p increases

the intracellular concentration of 5-FU, thereby enhancing the

sensitivity of CRC cells to 5-FU (49), suggesting the miR-3190-5p and

DPYD variant may serve as biomarkers for the personalized

use of 5-FU in CRC treatment.

The present study demonstrated upregulation of

miR-215-3p in the 85T>C variant and a downregulation in the

1896T>C variant compared with the wild-type. Previous studies

(50-52)

have indicated that the levels of miR-215-3p are associated with

the sensitivity of CRC cells to 5-FU, with alterations in

miR-215-3p affecting 5-FU sensitivity. Specifically, miR-215-3p has

been shown to enhance the apoptosis of CRC cells treated with 5-FU

(50). Mechanistically, miR-215-3p

regulates C-X-C chemokine receptor type 1 (CXCR1) expression in

human CRC HCT116) cells, and alterations in CXCR1 affect 5-FU

sensitivity, influencing CRC cell response to the drug (50,51).

The genetic variant-dependent regulation of miR-215-3p may provide

insight into personalized treatment strategies, where miR-215-3p

may serve as a biomarker for predicting response to 5-FU

chemotherapy in patients with CRC. Moreover, p53 is a key regulator

of the DNA damage response and apoptosis, both of which are

critical in determining cell sensitivity to 5-FU (52). Studies have shown that p53 status

influences miRNA expression profiles and may modulate response to

fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy (53,54).

Thus, variability in p53 function may interact with DPYD

variants and impact downstream miRNA expression and treatment

outcomes.

miR-365a-3p and miR-203a-5p were upregulated in the

85T>C variant and downregulated in the 1896T>C variant

compared with the wild-type. miR-365a-3p inhibits CRC progression,

at least in part by suppressing ADAM10 expression and the

associated JAK/STAT signaling pathway (55). miR-203a-5p regulates tumorigenesis

by downregulating suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 expression

(56), highlighting the signaling

axis as a potential therapeutic target in CRC.

Increasing evidence (24,25)

suggests that miRNAs may regulate DPYD expression and, by

extension, impact the metabolism of fluoropyrimidines. Offer et

al (24) identified expression

of miR-27a and miR-27b as potential pharmacological modulators of

hepatic DPD enzyme function (24).

DPD serves a crucial role in the uracil catabolic pathway by

converting the chemotherapy drug 5-FU into its inactive metabolite

5-dihydrofluorouracil. A deficiency in DPD, resulting from

insufficient expression or harmful variants in the DPYD

gene, is associated with severe toxic reactions to 5-FU (24). Additionally, patients who are

heterozygous for the miR-27a SNP (rs895819) have an increased risk

of fluoropyrimidine toxicity. This has been studied in both

individuals with wild-type and variant DPYD variant

(25). These findings suggest that

miR-27a rs895819 could serve as a potential biomarker for

predicting fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity. Hirota et

al (57) demonstrated that

DPYD is a target of several miRNAs, including miR-27a,

miR-27b, miR-134 and miR-582-5p (57). Overexpression of these miRNAs leads

to a significant reduction in reporter activity in a plasmid

containing the 3' UTR of DPYD mRNA in a luciferase assay

(57). Additionally, the

overexpression of these miRNAs also results in a notable decrease

in DPD protein levels in pancreatic carcinoma MIAPaca-2 cells,

suggesting these miRNAs regulate DPD protein expression at the

post-transcriptional level (57).

In the present study, miR-27a-3p and miR-27b-3p were significantly

downregulated in patients with CRC with the variant compared with

wild-type patients, indicating the absence of DPYD deficiency in

the DPYD 85T>C variant.

Hou et al (58) demonstrated similar miRNA expression

in human colon cancer cells (HT29) in response to 5-FU treatment

and nutrient starvation using miRNA microarray analysis (58). Bioinformatic predictions, pathway

and gene network analyses revealed four downregulated miRNAs,

including hsa-miR-302a-3p, and 27 upregulated miRNAs, which may

regulate autophagy in CRC cells during 5-FU-based chemotherapy

(58). The present study showed

that miR-302a-3p was upregulated in DPYD 85T>C compared

with wild-type CRC. The present study had limitations. The sample

size for miRNA analysis was relatively small, particularly in the

variant groups (n=4 for 85T>C and n=3 for 1896T>C), which may

limit statistical power and generalizability. The small sample size

may contribute to potential bias and increased variability and

limit the ability to detect subtle but biologically meaningful

differences. The present study focused on only three SNPs of

DPYD associated with 5-FU-related toxicities; other SNPs of

DPYD variants should be considered for further study.

Additionally, the lack of longitudinal data on toxicity progression

and survival outcomes limits the ability to establish causal links.

Future studies with larger, multi-center cohorts and functional

validation assays are warranted. These should include measurements

of DPD enzyme activity and 5-FU pharmacokinetics to clarify the

mechanistic association between the identified SNP variants, miRNA

expression profiles and clinical responses to 5-FU in CRC.

In conclusion, as miRNAs are regulators of drug

metabolism and toxicity, future research should focus on their

potential role in modulating the impact of DPYD

polymorphisms. Understanding the association between miRNA

expression and DPYD activity may facilitate personalized treatment

strategies, where miRNA profiling could be used alongside

DPYD genotyping to predict toxicity and optimize drug

dosing. Additionally, miRNA-based therapy may be explored as a

potential method to modulate DPYD activity in patients with low

enzyme activity, decreasing the risk of toxicity while maintaining

therapeutic efficacy.

Supplementary Material

miR target sequences used in the miR

array.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Sam

Ormond (Clinical Research Center, Faculty of Medicine, Thammasat

University, Pathum Thani, Thailand) for English editorial

assistance.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Health Systems

Research Institute under Genomics Thailand Strategic Fund (grant

no. 65-084) and Thailand Science Research and Innovation

Fundamental Fund, fiscal year 2025.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

PP designed the study, performed experiments,

analyzed data and wrote and revised the manuscript. PC, ES, TR, SA

and SS designed the study. PJ performed experiments. CS and CA

conceived and designed the study and analyzed data. CA wrote and

edited the manuscript. PP and CA confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was carried out in compliance

with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the

Ethics Committee of Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University,

Bangkok, Thailand (approval no. MURA2020/1613 Ref.2419). Written

informed consent was provided by all participants before the start

of the study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Longley DB, Harkin DP and Johnston PG:

5-Fluorouracil: Mechanisms of action and clinical strategies. Nat

Rev Cancer. 3:330–338. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Van Cutsem E, Cervantes A, Adam R, Sobrero

A, Van Krieken JH, Aderka D, Aranda Aguilar E, Bardelli A, Benson

A, Bodoky G, et al: ESMO consensus guidelines for the management of

patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol.

27:1386–1422. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Goto T, Shinmura K, Yokomizo K, Sakuraba

K, Kitamura Y, Shirahata A, Saito M, Kigawa G, Nemoto H, Sanada Y

and Hibi K: Expression levels of thymidylate synthase,

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, and thymidine phosphorylase in

patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 32:1757–1762.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Amstutz U, Henricks LM, Offer SM,

Barbarino J, Schellens JHM, Swen JJ, Klein TE, McLeod HL, Caudle

KE, Diasio RB and Schwab M: Clinical pharmacogenetics

implementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase genotype and fluoropyrimidine dosing: 2017 Update.

Clin Pharmacol Ther. 103:210–216. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Deac AL, Burz CC, Bocşe HF, Bocşan IC and

Buzoianu AD: A review on the importance of genotyping and

phenotyping in fluoropyrimidine treatment. Med Pharm Rep.

93:223–230. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Offer SM, Wegner NJ, Fossum C, Wang K and

Diasio RB: Phenotypic profiling of DPYD variations relevant to

5-fluorouracil sensitivity using real-time cellular analysis and in

vitro measurement of enzyme activity. Cancer Res. 73:1958–1968.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Falvella FS, Cheli S, Martinetti A,

Mazzali C, Iacovelli R, Maggi C, Gariboldi M, Pierotti MA, Di

Bartolomeo M, Sottotetti E, et al: DPD and UGT1A1 deficiency in

colorectal cancer patients receiving triplet chemotherapy with

fluoropyrimidines, oxaliplatin and irinotecan. Br J Clin Pharmacol.

80:581–588. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chan TH, Zhang JE and Pirmohamed M: DPYD

genetic polymorphisms in non-European patients with severe

fluoropyrimidine-related toxicity: A systematic review. Br J

Cancer. 131:498–514. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

He YF, Wei W, Zhang X, Li YH, Li S, Wang

FH, Lin XB, Li ZM, Zhang DS, Huang HQ, et al: Analysis of the DPYD

gene implicated in 5-fluorouracil catabolism in Chinese cancer

patients. J Clin Pharm Ther. 33:307–314. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Leung HWC and Chan ALF: Association and

prediction of severe 5-fluorouracil toxicity with dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase gene polymorphisms: A meta-analysis. Biomed Rep.

3:879–883. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Atasilp C, Vanwong N, Yodwongjane P,

Chansriwong P, Sirachainan E, Reungwetwattana T, Jinda P,

Aiempradit S, Sirilerttrakul S, Chamnanphon M, et al: Influence of

DPYD gene polymorphisms on 5-fluorouracil toxicities in Thai

colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol.

95(2)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Sarhangi N, Rouhollah F, Niknam N, Sharifi

F, Nikfar S, Larijani B, Patrinos GP and Hasanzad M:

Pharmacogenetic DPYD allele variant frequencies: A comprehensive

analysis across an ancestrally diverse Iranian population. Daru.

32:715–727. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Bartel DP: MicroRNAs: Genomics,

biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 116:281–297.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Miska EA: How microRNAs control cell

division, differentiation and death. Curr Opin Genet Dev.

15:563–568. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Sarkar FH, Li Y, Wang Z, Kong D and Ali S:

Implication of microRNAs in drug resistance for designing novel

cancer therapy. Drug Resist Updat. 13:57–66. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Magee P, Shi L and Garofalo M: Role of

microRNAs in chemoresistance. Ann Transl Med. 3(332)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Si W, Shen J, Zheng H and Fan W: The role

and mechanisms of action of microRNAs in cancer drug resistance.

Clin Epigenetics. 11(25)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Condrat CE, Thompson DC, Barbu MG, Bugnar

OL, Boboc A, Cretoiu D, Suciu N, Cretoiu SM and Voinea SC: miRNAs

as biomarkers in disease: latest findings regarding their role in

diagnosis and prognosis. Cells. 9(276)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Ferracin M, Lupini L, Salamon I, Saccenti

E, Zanzi MV, Rocchi A, Da Ros L, Zagatti B, Musa G, Bassi C, et al:

Absolute quantification of cell-free microRNAs in cancer patients.

Oncotarget. 6:14545–14555. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Li J, Liu Y, Wang C, Deng T, Liang H, Wang

Y, Huang D, Fan Q, Wang X, Ning T, et al: Serum miRNA expression

profile as a prognostic biomarker of stage II/III colorectal

adenocarcinoma. Sci Rep. 5(12921)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Bader El Din NG, El-Shenawy R, Moustafa

RI, Khairy A and Farouk S: Association between the expression level

of miRNA-374a and TGF-β1 in patients with colorectal cancer. World

Acad Sci J. 6(68)2024.

|

|

22

|

Okamoto K, Nozawa H, Ozawa T, Yamamoto Y,

Yokoyama Y, Emoto S, Murono K, Sasaki K, Fujishiro M and Ishihara

S: Comparative microRNA signatures based on liquid biopsy to

identify lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal cancer patients

undergoing upfront surgery or endoscopic resection. Cell Death

Discov. 11(67)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Schwab S and Nonaka T: Circulating miRNAs

as liquid biopsy biomarkers for diagnosis in patients with

colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front

Genet. 16(1574586)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Offer SM, Butterfield GL, Jerde CR, Fossum

CC, Wegner NJ and Diasio RB: microRNAs miR-27a and miR-27b directly

regulate liver dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase expression through

two conserved binding sites. Mol Cancer Ther. 13:742–751.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Medwid S, Wigle TJ, Ross C and Kim RB:

Genetic variation in miR-27a Is associated with

fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity in patients with

dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase variants after genotype-guided dose

reduction. Int J Mol Sci. 24(13284)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Meulendijks D, Henricks LM, Sonke GS,

Deenen MJ, Froehlich TK, Amstutz U, Largiadèr CR, Jennings BA,

Marinaki AM, Sanderson JD, et al: Clinical relevance of DPYD

variants c.1679T>G, c.1236G>A/HapB3, and c.1601G>A as

predictors of severe fluoropyrimidine-associated toxicity: A

systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data.

Lancet Oncol. 16:1639–1650. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J,

Davis TE, McFadden ET and Carbone PP: Toxicity and response

criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin

Oncol. 5:649–655. 1982.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Freites-Martinez A, Santana N,

Arias-Santiago S and Viera A: Using the common terminology criteria

for adverse events (CTCAE-version 5.0) to evaluate the severity of

adverse events of anticancer therapies. Actas Dermosifiliogr (Engl

Ed). 112:90–92. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In English,

Spanish).

|

|

29

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Eisen MB, Spellman PT, Brown PO and

Botstein D: Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression

patterns. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 95:14863–14868. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Wilkinson L and Friendly M: The history of

the cluster heat map. Am Statist. 63:179–184. 2009.

|

|

32

|

Mounier-Boutoille H, Boisdron-Celle M,

Cauchin E, Galmiche JP, Morel A, Gamelin E and Matysiak-Budnik T:

Lethal outcome of 5-fluorouracil infusion in a patient with a total

DPD deficiency and a double DPYD and UTG1A1 gene mutation. Br J

Clin Pharmacol. 70:280–283. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Chai J, Dong W, Xie C, Wang L, Han DL,

Wang S, Guo HL and Zhang ZL: MicroRNA-494 sensitizes colon cancer

cells to fluorouracil through regulation of DPYD. IUBMB Life.

67:191–201. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Van Kuilenburg ABP, Meinsma R, Zoetekouw L

and Van Gennip AH: Increased risk of grade IV neutropenia after

administration of 5-fluorouracil due to a dihydropyrimidine

dehydrogenase deficiency: High prevalence of the IVS14+1g>a

mutation. Int J Cancer. 101:253–258. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Zhang H, Li YM, Zhang H and Jin X: DPYD*5

gene mutation contributes to the reduced DPYD enzyme activity and

chemotherapeutic toxicity of 5-FU: Results from genotyping study on

75 gastric carcinoma and colon carcinoma patients. Med Oncol.

24:251–258. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Raha R, Bhoyar RC, Biswal RP,

Venkatakrishnan R, Rai P, Umashankar E, Kulkarni PM, Sivasubbu S,

Scaria V and Jolly B: Opportunistic analysis of clinically

actionable DPYD gene variants in a germline testing cohort in

India. Pharmacogenomics. 1–6. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

37

|

Varma A, Jayanthi M, Dubashi B, Shewade DG

and Sundaram R: Genetic influence of DPYD*9A polymorphism on plasma

levels of 5-fluorouracil and subsequent toxicity after oral

administration of capecitabine in colorectal cancer patients of

South Indian origin. Drug Metab Pers Ther. 35:2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Detailleur S, Segelov E, Re MD and Prenen

H: Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase deficiency in patients with

severe toxicity after 5-fluorouracil: A retrospective single-center

study. Ann Gastroenterol. 34:68–72. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

O'Brien J, Hayder H, Zayed Y and Peng C:

Overview of MicroRNA biogenesis, mechanisms of actions, and

circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 9(402)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Dluzen DF and Lazarus P: MicroRNA

regulation of the major drug-metabolizing enzymes and related

transcription factors. Drug Metab Rev. 47:320–334. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Sun X, Chen J, Chen X, Gao Q, Chen W, Zou

X, Zhang F, Gao S, Qiu S, Yue X, et al: A systematic review of

clinical validated and potential miRNA markers related to the

efficacy of fluoropyrimidine drugs. Dis Markers.

2022(1360954)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Jin XH, Lu S and Wang AF: Expression and

clinical significance of miR-4516 and miR-21-5p in serum of

patients with colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 20(241)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Jin RR, Zeng C and Chen Y: MiR-22-3p

regulates the proliferation, migration and invasion of colorectal

cancer cells by directly targeting KDM3A through the Hippo pathway.

Histol Histopathol. 37:1241–1252. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Xia SS, Zhang GJ, Liu ZL, Tian HP, He Y,

Meng CY, Li LF, Wang ZW and Zhou T: MicroRNA-22 suppresses the

growth, migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells through a

Sp1 negative feedback loop. Oncotarget. 8:36266–36278.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Lu C, Jiang W, Hui B, Rong D, Fu K, Dong

C, Tang W and Cao H: The circ_0021977/miR-10b-5p/P21 and P53

regulatory axis suppresses proliferation, migration, and invasion

in colorectal cancer. J Cell Physiol. 235:2273–2285.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Zhang Y, Talmon G and Wang J: MicroRNA-587

antagonizes 5-FU-induced apoptosis and confers drug resistance by

regulating PPP2R1B expression in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis.

6(e1845)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Xiao Z, Liu Y, Li Q, Liu Q, Liu Y, Luo Y

and Wei S: EVs delivery of miR-1915-3p improves the

chemotherapeutic efficacy of oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer.

Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 88:1021–1031. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wu Q, Meng WY, Jie Y and Zhao H: LncRNA

MALAT1 induces colon cancer development by regulating

miR-129-5p/HMGB1 axis. J Cell Physiol. 233:6750–6757.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Chen Q, Meng F, Wang L, Mao Y, Zhou H, Hua

D, Zhang H and Wang W: A polymorphism in ABCC4 is related to

efficacy of 5-FU/capecitabine-based chemotherapy in colorectal

cancer patients. Sci Rep. 7(7059)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Li XW, Qiu SJ and Zhang X: Overexpression

of miR-215-3p sensitizes colorectal cancer to 5-fluorouracil

induced apoptosis through regulating CXCR1. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol

Sci. 22:7240–7250. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Jafarzadeh A, Seyedmoalemi S, Dashti A,

Nemati M, Jafarzadeh S, Aminizadeh N, Vosough M, Rajabi A,

Afrasiabi A and Mirzaei H: Interplays between non-coding RNAs and

chemokines in digestive system cancers. Biomed Pharmacother.

152(113237)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Tang X, Shi X, Wang N, Peng W and Cheng Z:

MicroRNA-215-3p suppresses the growth, migration, and invasion of

colorectal cancer by targeting FOXM1. Technol Cancer Res Treat.

18(1533033819874776)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Hermeking H: MicroRNAs in the p53 network:

Micromanagement of tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 12:613–626.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Eymin B and Gazzeri S: Role of cell cycle

regulators in lung carcinogenesis. Cell Adh Migr. 4:114–123.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Hong YG, Xin C, Zheng H, Huang ZP, Yang Y,

Zhou JD, Gao XH, Hao L, Liu QZ, Zhang W and Hao LQ: miR-365a-3p

regulates ADAM10-JAK-STAT signaling to suppress the growth and

metastasis of colorectal cancer cells. J Cancer. 11:3634–3644.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Al-Asadi S, Mansour H, Ataimish AJ,

Al-Kahachi R and Rampurawala J: MicroRNAs regulate tumorigenesis by

downregulating SOCS3 expression: An in silico approach. Bioinform

Biol Insights. 17(11779322231193535)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Hirota T, Date Y, Nishibatake Y, Takane H,

Fukuoka Y, Taniguchi Y, Burioka N, Shimizu E, Nakamura H, Otsubo K

and Ieiri I: Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) expression is

negatively regulated by certain microRNAs in human lung tissues.

Lung Cancer. 77:16–23. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Hou N, Han J, Li J, Liu Y, Qin Y, Ni L,

Song T and Huang C: MicroRNA profiling in human colon cancer cells

during 5-fluorouracil-induced autophagy. PLoS One.

9(e114779)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|