Introduction

Epigenetic DNA modification mechanisms play a key

role in various cell cycle functions (1,2). High

methylation of certain fragments or whole chromosomes may be

associated with partial or complete transcriptional inactivation. A

total of ~5% of cytosine residues are continuously methylated in

mammals (3). The methylation

percentage differs between species; for example it is often 30% in

plants but does not appear in Drosophila melanogaster

(4).

In mammals, introns constitute up to 95% of the

primary gene transcripts (5).

Although the introns do not encode proteins, they participate in

important cellular functions (6).

Firstly, introns enhance the expression of corresponding genes and

must be present in the transcribed region to enhance gene

expression (7,8). Secondly, the introns increase

transcript initiation upstream and may represent a downstream

regulatory element for genes transcribed by RNA polymerase II

(8).

DNA methylation mechanisms have been reviewed in the

context of ovarian cancer development and progression (1,9).

However, a limited number of studies have analysed the CpG island

TP53 methylation status at the promoter region and within

introns (10,11). For example, the TP53 promoter

is methylated in 51.5% of ovarian carcinoma (OC) samples and 29.7%

of patients with healthy ovaries. However, no clinicopathological

parameters are associated with the TP53 methylation pattern.

These data revealed a significant difference in promoter

TP53 methylation between OC and control samples, implying

the influence of TP53 methylation on ovarian tumorigenesis

(10).

In our recent study, the TP53 methylation

status was investigated in a cohort of 80 patients with stage III

OC. Intron 1 was un-methylated in all samples, whereas introns 3

and 4 were methylated (12). In the

present study, 10 CpG exon 4 pairs were analysed in primary OC,

corresponding metastases, healthy samples and the A2780 ovarian

endometroid adenocarcinoma. The aim of the present study was to

compare the TP53 methylation status of exon and intron 4 in

advanced-stage OC samples.

Materials and methods

Samples

The tissue samples were collected from 80 patients

aged 55-65 who had undergone surgical treatment for advanced-stage

OC at the Department of Gynecology and Gynecology Oncology at the

Military Institute of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland, between January

2014 and December 2018. The present study included only patients

with FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics)

stages IIIA-C (13).

Chemotherapy, hormonal therapy or radiotherapy were

not administered prior to the operation. In total, the study

included samples from 40 patients with serous G2/3 and 40 patients

with endometrioid G2/3 OC, corresponding metastatic samples and

healthy tissue (skin) samples from each patient. The detailed

clinicopathological features of the patients have been previously

presented (12). The human ovarian

cancer A2780 cell line (Merck KGaA), established from an ovarian

endometrioid-type adenocarcinoma in an untreated patient, was also

included. Control samples (skin) were sourced from 80 patients aged

35-45 years (50% male and 50% women), who had never had cancer who

and underwent bariatric surgical operations at the Department of

Surgery, Military Institute of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland, between

January 2014 and December 2018. The present study was approved by

the Bioethics Committee of the Military Institute of Medicine,

Warsaw, Poland with the informed consent of the patients (approval

no. N25/WIM/2013).

Following fixation in 10% buffered formalin (pH 7.4)

at room temperature for 24 h, hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides

(room temperature for 1 h) were prepared from paraffin-embedded

tissue (12). Thickness of sections

were 4 µm. The slides were analysed with light microscope by the

anatomopathologist to confirm the primary diagnosis (14).

DNA isolation and bisulfite

conversion

Total genomic DNA was isolated using the ExtractMe

DNA Tissue Isolation kit (cat. nr 51404; Qiagen GmbH, Germany). The

quantity and quality of DNA was evaluated spectrophotometrically

(DeNovix DS-11; DeNovix Inc.). Bisulfite DNA conversion was

performed using the Methyl Code Bisulfite Conversion kit (cat. nr.

1024702; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as previously

reported (12).

Primer sequences

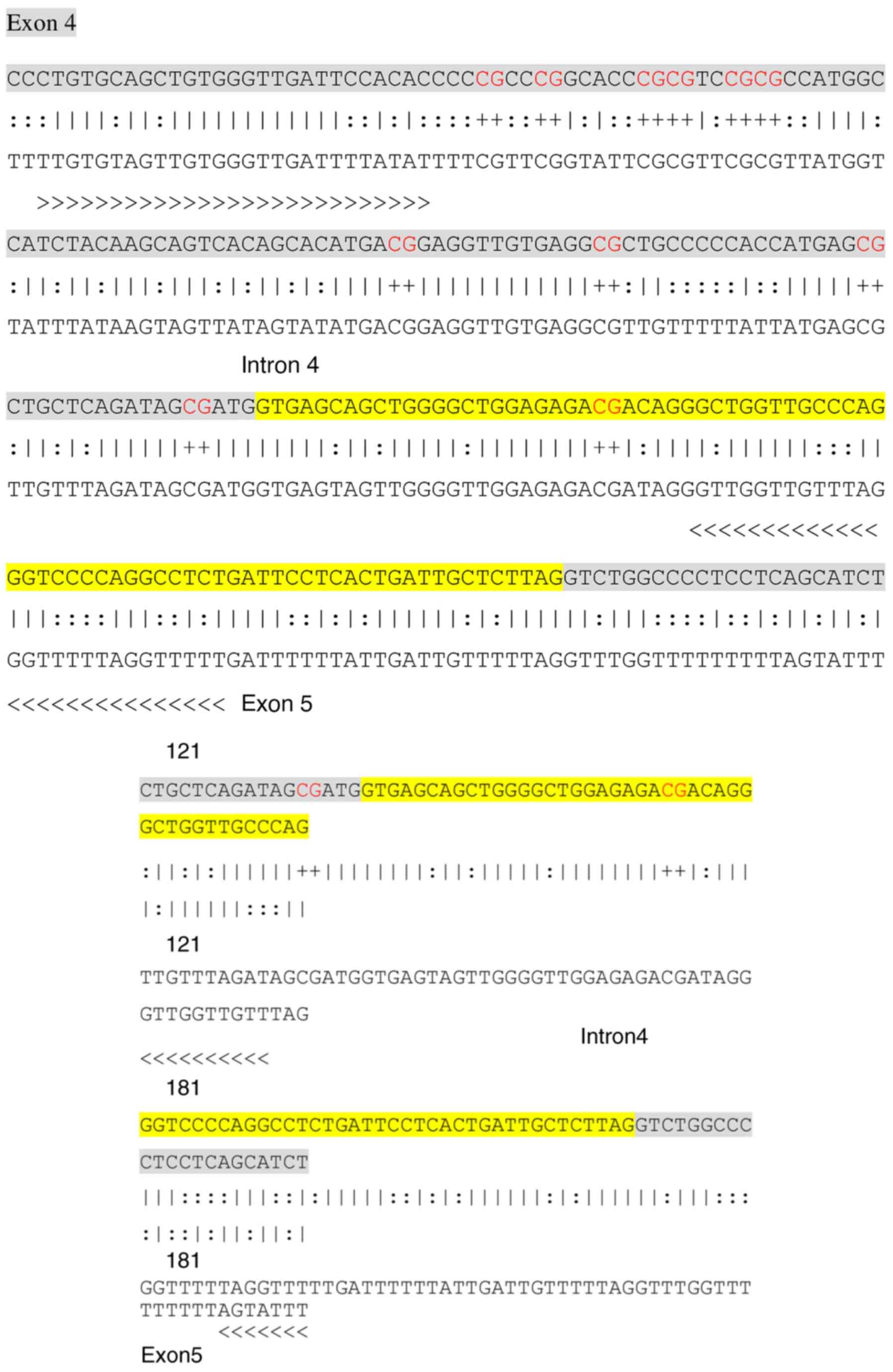

Gene-specific primer sequences for exon 4/intron 4

were designed based on the TP53 sequence published in

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NC_000017.10) using

MethPrimer-Design software version no. 1 (urogene.org.) (15).

Primer sequences were as follows: Forward,

5'-TTGTGTAGTTGTGGGTTGATTTTATAT-3', and reverse,

5'-AAAAACCTAAAAACCCTAAACAACC-3'. The product size was 193 bp. In

total, 11 CpG pairs were investigated, of which one spanned the

TP53 intron 4 and 10 the TP53 exon 4 (Fig. 1).

DNA amplification and sequencing

The amplification of the TP53 exon 4/intron 4

sequences was performed using MyTaqHS Red Mix (cat. no. BIO-25048;

Blirt) as described previously (12). Thermocycling conditions were as

follows: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 1 min, followed by

denaturation at 95˚C for 15 sec, annealing at 56˚C for 15 sec,

extension at 72˚C for 15 sec, number of cycles 45, and final

extension at 72˚C for 4 min. PCR products were verified by

electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels (1 ug/line) using Midori Green

nuclear staining dye (cat. no. MG04; Nippon Genetics Europe GmbH).

The product was extracted for cloning with the use of ExtractMe DNA

Gel-out kit (cat. no. 28706; Qiagen GmbH). The ligation between the

plasmid vector and the PCR product was performed using Qiagen PCR

Cloning kit (cat. no. 231124; Qiagen GmbH). Finally, the vectors

were transformed into E. coli high efficiency competent

cells according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England

BioLabs Ltd.). The cells were incubated at 37˚C overnight on LB

Agar Miller (Medium A&A Biotechnology) with ampicillin,

isopropyl-β-1-thiogalactopiranozyd) and X-gal (cat. no. MBO2501;

Blirt, Poland). A blue-white screening colony selection method was

used to select a recombinant white clone followed by PCR

amplification (as aforementioned) with MyTaqHS Red Mix (cat. no.

BIO-25047; Meridian Biosc., USA) of the colony to confirm the

cloning with the gene segments of interest. Only white colonies of

recombinant plasmid isolation from the bacteria growing in liquid

Luria Broth medium plate were selected and cultured in LB medium at

37˚C overnight. The plasmid was isolated using Plasmid Mini DNA

Isolation kit (cat. no. 020-50 A&A Biotechnology, Poland). The

results of the recombinant DNA were examined using 1.5% agarose gel

electrophoresis (1 µg/lane). The clones containing right inserts

were subjected to direct bidirectional sequencing using an AB3130

genetic analyser with T7/SP6 primers and an Big Dye®

Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kit (cat. no. 4337455; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All KITs were used according to the

manufacturer's instructions.

Results

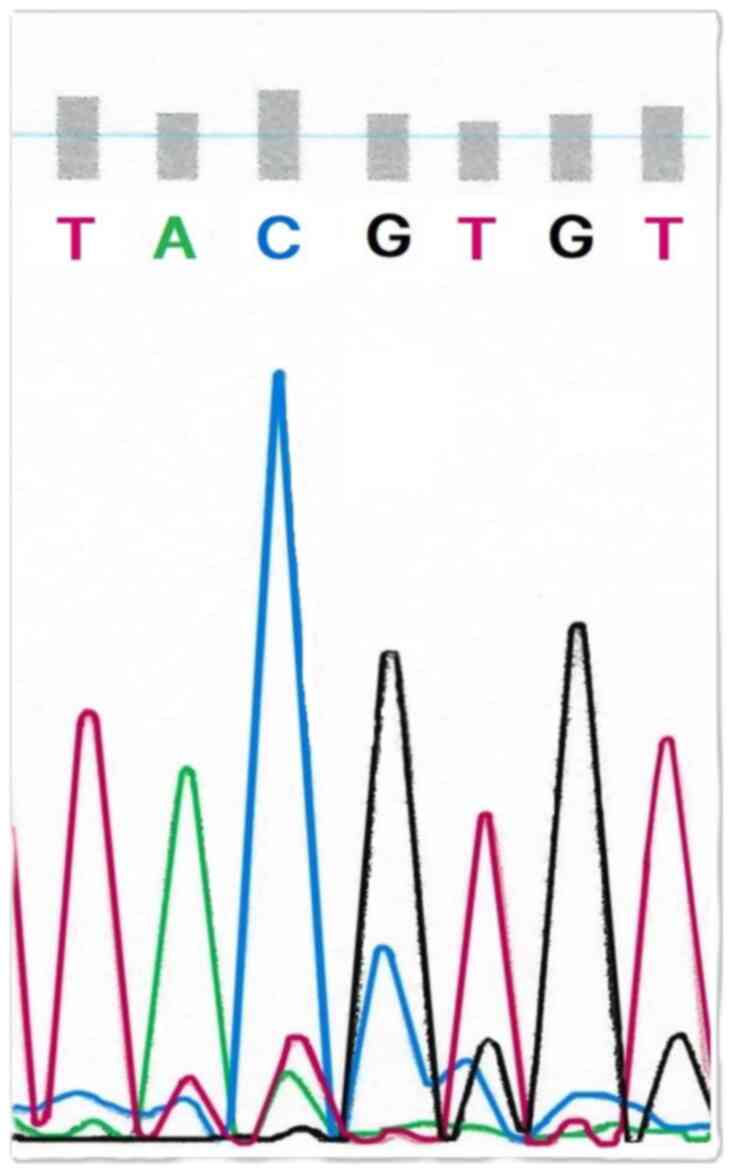

Exon 4 TP53 CpG pairs were all methylated in

neoplastic ovarian samples collected from patients with

advanced-stage OC and in the corresponding metastatic samples. The

tissue samples from healthy people who had never had cancer were

also all methylated. An example of the TP53 exon 4

methylation in the sequencing samples of primary stage IIIC

endometrioid-type OC is presented in Fig. 2.

Similarly, one intron 4 TP53 CpG pair

revealed methylation in all samples. Moreover, the A2780 human

ovarian cancer cell line revealed TP53 exon 4/intron 4

methylation (data not shown).

Finally, no differences were noted in the

exon/intron 4 methylation statuses of TP53 based on

clinicopathological OC features (Table

I).

| Table IClinical and pathological variables

of patients with ovarian carcinoma. |

Table I

Clinical and pathological variables

of patients with ovarian carcinoma.

| Characteristic | Samples (%) |

|---|

| Age, (years) | |

|

<50 | 1 (1.5) |

|

50-60 | 18 (22.5) |

|

>60 | 61(76) |

| Menopause

status | |

|

Pre-menopause | 3(4) |

|

Post-menopause | 77(96) |

| Clinical stage | |

|

IIIA | 5(6) |

|

IIIB | 36(45) |

|

IIIC | 39(49) |

| Histological

type | |

|

Serous | 40(50) |

|

Endometrioid | 40(50) |

| Histological

grade | |

|

G1 | 0 (0) |

|

G2 | 37(46) |

|

G3 | 43(54) |

Discussion

DNA methylation serves a crucial role in normal

embryonic development, aging, gene regulation and specific cells

functions (16). In general, CpG

islands located within gene promoters are unmethylated in normal

human cells, except for the inactive genes spanning the X

chromosome and those subjected to genomic imprinting (the process

where one paternal copy of the certain gene is silenced) (16,17).

However, silencing of tumour suppressor gene activity in most cases

occurs through methylation of promoter regions at all stages of

human carcinogenesis, including the development of OC (1,2,9-12,17).

OC is one of the most insidious and dangerous female

genital tract malignancies due to its high aggressiveness (18,19).

The majority of OC is reported at advanced clinical stages of the

disease. The 5-year survival rate of stages III and IV is still

unsatisfactory, despite the use of extensive surgical procedures

and the development of anti-cancer therapy treatments (20,21).

The pathogenesis of OC is still debatable. Kurman and Shih

(22) proposed that fallopian tube

epithelium (benign or malignant) that implants on the ovary is the

source of low- and high-grade serous carcinoma rather than the

ovarian surface epithelium. Two OC histological subtypes (type I,

low-grade serous or endometrioid, clear cell, mucinous and

transitional OC, and type II: high-grade serous, undifferentiated,

and carcinosarcoma) differ significantly regardless of the

TP53 alterations and p53 immunoreactivity (23). Different TP53 alterations and

p53 expression patterns have been described in human borderline

ovarian tumours (24). However,

data regarding the role of TP53 exogenic/intragenic

methylation status during ovarian carcinogenesis are scarce

(9-12,25).

Although the role of extragenic methylation on

TP53 has not been fully resolved, CpG pairs are vulnerable

to methylation/demethylation mechanisms (7). Altered exonic CpG methylation modifies

promoter initiation sites, resulting in the expression of different

protein isoforms (26,27). Exogenic CpG sequences in TP53

are methylated in various cancer types (for example colon and lung

cancer) (25). Genetic TP53

alterations are associated with transitions (G:C->A:T), which

are frequently found in human tissue and normal cell lines, for

example in lung epithelial cells, mammary epithelial cells, or in

colonic mucosa cells (25)

Moreover, non-CpG methylation in CC and CCC sequences is associated

with methylation at repetitive TP53 genetic sequences

(28).

Hydrolytic deamination of 5-mC is typically

considered as the mechanism responsible for the high incidence of

TP53 C-T transition mutations within CpG dinucleotides

(3,25). C-T transitions at CpG may also

result from methyltransferase-catalysed cytosine deamination. The

frequency and types of TP53 mutations at CpG dinucleotides

vary between human tumours (1-3,23).

For example, in colon carcinoma, 47% of mutations are reported at

CpG islands, with 17% are reported in skin cancer and 9% in lung

cancer (1-3).

Although the methylation status of introns 1-4 in

TP53 in advanced-stage OC has been previously studied

(12), to the best of our

knowledge, exon 4 has not been previously investigated. The present

study examined exon/intron 4 TP53 and demonstrated that 11

CpG islands were all methylated. Most studies that have examined

comprehensive DNA methylation have focused on the promoter regions

of genes, and, in the majority of the cases, an inverse association

between gene expression and methylation has been found (1,3,25).

Methylation in downstream exon sequences generally is not

associated with expression or lack of expression of p53 in various

tissues. The TP53 sequences along exons 5-8 are completely

methylated at each CpG, including 46 different sites on both DNA

strands (25). This methylation

pattern is tissue-independent, suggesting that tissue-specific

methylation does not contribute to the differential mutation

pattern in various tumours. A total of nine types of normal human

tissues and cell lines, including skin fibroblasts, keratinocytes,

lung and mammary epithelial and colonic mucosa cells, have been

investigated (25). However, it is

unclear whether complete methylation of all CpG sites is unique to

TP53.

Although TP53 CpG dinucleotides are prone to

methylation-dependent mechanisms (25), the regulatory role of methylation

mechanism affecting CpG sites has yet to be clarified. In previous

studies, DNA damage and cell aging are both associated with

site-specific CpG demethylation in exon 5 accompanied by the

induction of expression of truncated protein isoforms regulated by

an adjacent intronic P2 promoter (spanning intron 4) (25,26).

The changes in the levels of intragenic TP53 CpG methylation

are extrinsically inducible, suggesting that cancer progression is

mediated, in part, by dysregulation of damage-inducible intragenic

CpG demethylation (26).

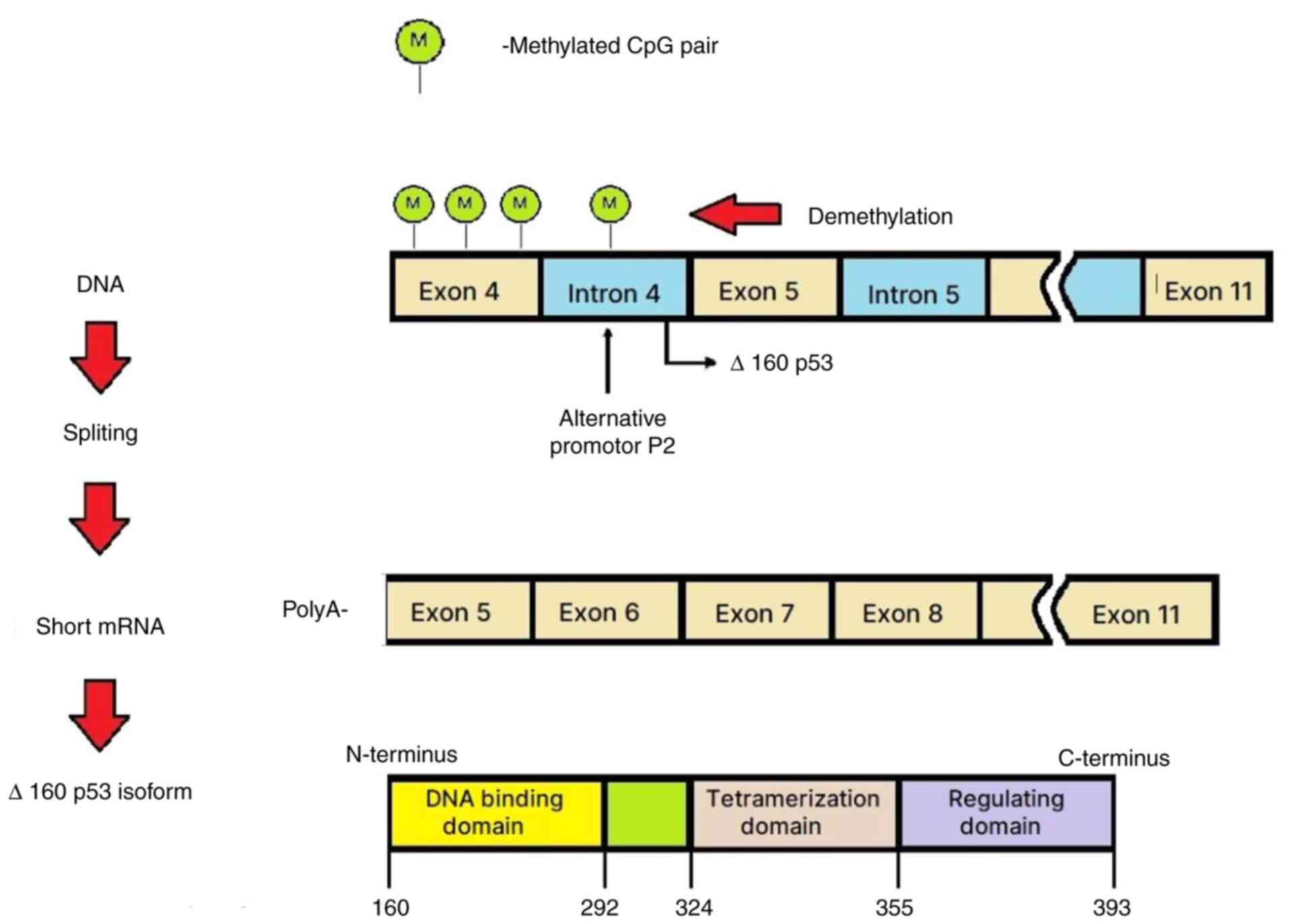

The role of alternative promoters in mammalian

genomes has been reviewed by Landry et al (27). Bourdon et al (28,29)

reported that TP53 has transcriptional start sites that span

exon 1 and contain a transcription initiation site at intron 4. The

aforementioned study revealed that TP53 had a complex

transcriptional regulatory pattern encoding different p53 mRNA

variants through the use of alternative splicing and an internal

(intron 4) promoter. The alternative promoter leads to the

expression of N-terminally truncated proteins. The two distinct

TP53 promoters (P1, upstream of exon 1, and P2, within

intron 4) and alternative splicing process and translation

initiation sites of the different mRNAs result in formation of

various p53 isoforms (30).

The transcription of TP53 mRNA can initiate

the formation of the Δ133p53 and Δ160p53 isoforms from the internal

P2 promoter. Considering alternative splicing at intron 9, these

transcripts lead to the production of various isoforms (Δ133p53α,

Δ133p53β, Δ133p53γ, Δ160p53α, Δ160p53β and Δ160p53γ) (31). Despite truncations in the DNA

binding domain, the Δ133p53 and Δ160p53 isoforms have a stable 3D

conformation (31). The alternative

promoter located in intron 4 becomes active following DNA

demethylation in this region. Therefore, the generated p53 isoforms

are shorter, lack the mouse double minute homolog 2 binding site,

have a longer life-span and can potentially induce apoptosis

(28,29,32,33).

In conclusion, the present findings suggest the

existence of intragenic mechanisms responsible for the regulation

of the TP53 activity, based on demethylation/methylation status

(Fig. 3).

The intragenic demethylation-methylation mechanism

provides the ability to switch the cellular response from cell

cycle arrest to apoptosis by manipulating only the expression of

p53 isoforms and is damaged in solid cancer. Therefore, it has been

hypothesized that demethylation of the TP53 promoter in

intron 4 may be a target for the potential treatment of solid

tumours.

The present study had limitations. Firstly, other

histopathological OC subtypes, apart from serous and endometrioid

subtypes, should be investigated to explore the intron/exon 4

TP53 methylation pattern. Secondly, survival of patients

with OC in relation the TP53 intron 4/exon 4 methylation was

not analysed. Future studies should explore potential interactions

between TP53 methylation patterns and other epigenetic

modifiers (such as histone modification). Moreover, TP53

mutational analysis in advanced-stage OC should be performed.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Military

Institute of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland (grant number 7/8826, project

302).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

WS conceived and designed the study, and performed

the experiments. OS made substantial contributions to the

conception of the study, design of the figures, and analysis and

interpretation of the data. KC analyzed and interpreted the data.

RG performed and analyzed the sequencing. MW participated in sample

collection, and analysis and interpretation of the data. MS

analyzed and interpreted the data. AS analyzed and interpreted the

data, revised the manuscript and prepared the final version of the

article. WS and AS confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors read and approved the final version of the

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Bioethics

Committee of the Military Institute of Medicine, Warsaw, Poland

(approval no. N25/WIM/2013). All participants read and signed an

informed consent form prior to participation.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Fu M, Deng F, Chen J, Fu L, Lei J, Xu T,

Chen Y, Zhou J, Gao Q and Ding H: Current data and future

perspectives on DNA methylation in ovarian cancer (review). Int J

Oncol. 64(62)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Geissler F, Nesic K, Kondrashova O,

Dobrovic A, Swisher EM, Scott CL and Wakefield MJ: The role of

aberrant DNA methylation in cancer initiation and clinical impacts.

Ther Adv Med Oncol. 16(17588359231220511)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Dong Y, Zhao H, Li H, Li X and Yang S: DNA

methylation as an early diagnostic marker of cancer (review).

Biomed Rep. 2:326–330. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Lyko F, Ramsahoye BH and Jaenisch R: DNA

methylation in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 408:538–540.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Louro R, Smirnova AS and Verjovski-Almeida

S: Long intronic noncoding RNA transcription: Expression noise or

expression choice? Genomics. 93:291–298. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mattick JS and Gagen MJ: The evolution of

controlled multitasked gene networks: The role of introns and other

noncoding RNAs in the development of complex organisms. Mol Biol

Evol. 18:1611–1630. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Rose AB: Introns as gene regulators. A

brick on the accelerator. Front Genet. 9(672)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Gallegos JE and Rose AB: The enduring

mystery of intron-mediated enhancement. Plant Sci. 237:8–15.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Earp MA and Cunningham JM: DNA methylation

changes in epithelial ovarian cancer histotypes. Genomics.

106:311–321. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chmelarova M, Krepinska E, Spacek J, Laco

J, Beranek M and Palicka V: Methylation in the p53 promoter in

epithelial ovarian cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 15:160–163.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Cunningham JM, Winham SJ, Wang C, Weiglt

B, Fu Z, Armasu SM, McCauley BM, Brand AH, Chiew YE, Elishaev E, et

al: DNA methylation profiles of ovarian clear cell carcinoma.

Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 31:132–141. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Szewczuk W, Szewczuk O, Czajkowski K,

Gromadka R, Man YG, Waledziak M and Semczuk A: Methylation of the

selected TP53 introns in advanced-stage ovarian carcinomas. J

Cancer. 15:4040–4046. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Javadi S, Ganeshan DM, Qayyum A, Iyer RB

and Bhosale P: Ovarian cancer, the revised FIGO staging system, and

the role of imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 206:1351–1360.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Comănescu M, Arsene D, Ardeleanu C and

Bussolati G: The mandate for a proper preservation in

histopathological tissues. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 53:233–242.

2012.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Li LC and Dahiya R: MethPrimer: Designing

primers for methylation PCRs. Bioinformatics. 18:1427–1431.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sulewska A, Niklinska A, Kozlowski M,

Minarowski L, Naumnik W, Niklinski J, Dabrowska K and Chyczewski L:

DNA methylation in states of cell physiology and pathology. Folia

Histochem Cytobiol. 45:149–158. 2007.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Tajlakhsh J, Mortazavi F and Gupta NK: DNA

methylation topology differentiates between normal and malignant in

cell models, resected human tissues, and exfoliated sputum cells of

lung epithelium. Front Oncol. 12(991120)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Webb PM and Jordan SJ: Epidemiology of

epithelial ovarian cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol.

41:3–14. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Didkowska J, Wojciechowska U, Michalek IM

and Dos Santos FLC: Cancer incidence and mortality in Poland in

2019. Sci Rep. 12(10875)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chi DS, Eisenhauer EL, Zivanovic O, Sonoda

Y, Abu-Rustum NR, Levine DA, Guile MW, Bristow RE, Aghajanian C and

Barakat RR: Improved progression-free and overall survival in

advanced ovarian cancer as a result of a change in surgical

paradigm. Gynecol Oncol. 114:26–31. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Tavares V, Marques IS, Guerra de Melo I,

Assis J, Pereira D and Medeiros R: Paradigm shift: A comprehensive

review of ovarian cancer management in an era of advancements. Int

J Mol Sci. 25(1845)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Kurman RJ and Shih IeM: Molecular

pathogenesis and extraovarian origin of epithelial ovarian

cancer-shifting the paradigm. Hum Pathol. 42:918–931.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Vang R, Levine DA, Soslow RA, Zaloudek C,

Shih IM and Kurman RJ: Molecular alterations of TP53 are a defining

feature of ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma. A rereview of cases

lacking TP53 mutations in the cancer genome atlas ovarian study.

Int J Gynecol Pathol. 35:48–55. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Semczuk A, Gogacz M, Semczuk-Sikora A,

Jóźwik M and Rechberger T: The putative role of TP53 alterations

and p53 expression in borderline ovarian tumors-correlation with

clinicopathological features and prognosis: A mini-review. J

Cancer. 8:2684–2691. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Tornaletti S and Pfeifer GP: Complete and

tissue-independent methylation of CpG sites in the p53 gene:

Implications for mutations in human cancers. Oncogene.

10:1493–1499. 1995.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Blackburn J, Roden DL, Ng R, Wu J, Bosman

A and Epstein RJ: Damage-inducible intragenic demethylation of the

human TP53 tumor suppressor gene is associated with transcription

from an alternative intronic promoter. Mol Carcinog. 55:1940–1951.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Landry JR, Mager DL and Wilhelm BT:

Complex controls: The role of alternative promoters in mammalian

genomes. Trends Genet. 19:640–648. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Bourdon JC, Fernandes K, Murray-Zmijewski

F, Liu G, Diot A, Xirodimas D, Saville MK and Lane DP: p53 isoforms

can regulate p53 transcriptional activity. Genes Dev. 19:2122–2137.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bourdon JC: p53 and its isoforms in

cancer. Br J Cancer. 97:277–282. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Khoury MP and Bourdon JC: p53 isoforms: An

intracellular microprocessor? Genes Cancer. 2:453–465.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Joruiz SM and Bourdon JC: p53 isoforms:

Key regulators of the cell fate decision. Cold Spring Harb Perspect

Med. 6(a026039)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Lei J, Qi R, Tang Y, Wang W, Wei G,

Nussinov R and Ma B: Conformational stability and dynamics of the

cancer-associated isoform Δ133p53β are modulated by p53 peptides

and p53-specific DNA. FASEB J. 33:4225–4235. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Camus S, Ménendez S, Fernandes K, Kua N,

Liu G, Xirodimas DP, Lane DP and Bourdon JC: The p53 isoforms are

differentially modified by Mdm2. Cell Cycle. 11:1646–1655.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|