Introduction

Acute lung injury (ALI) and acute respiratory

distress syndrome (ARDS) are serious respiratory conditions

characterized by hypoxemia, bilateral opacities on chest

radiographs and reduced lung compliance (1,2).

ALI/ARDS has a high annual mortality rate among critically ill

patients. The underlying pathology of ALI/ARDS involves the

disruption of the pulmonary vascular endothelial barrier function,

due to endothelial cell death and the loss of endothelial adhesion

connections (3,4). The mechanism of cell death in

pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (PMVECs) is relatively

complex, with pyroptosis being considered as the primary mode

(5,6).

Pyroptosis is a form of programmed cell death

primarily mediated by gasdermin D (GSDMD), resulting in the release

of numerous pro-inflammatory cytokines (7). In addition, autophagy is a process

essential for maintaining cellular homeostasis (8). Comprehensively, autophagy can

negatively regulate pyroptosis by degrading, pathogen-associated

molecular patterns and other cellular components involved in this

process (9).

SPD, as an autophagic inducer, may exert protective

effects against ALI. In the present study, the role and mechanism

of SPD in LPS-induced ALI was investigated by establishing both an

in vivo ALI mouse model and an in vitro pyroptosis

model using PMVECs. The aim of the study was to demonstrate that

spermidine (SPD) effectively suppresses PMVEC pyroptosis by

promoting autophagic flux, thereby ameliorating LPS-induced

ALI.

Materials and methods

Reagents and antibodies

LPS and SPD were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Merck

KGaA). Nigericin (cat. no. HY-100381) and chloroquine (CQ) (cat.

no. HY-17589A) were provided by MedChemExpress. Antibodies against

caspase-1 (cat. no. ab207802), GSDMD (cat. no. ab219800), and

sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1)/p62 (cat. no. ab109012) were supplied by

Abcam. The antibody against microtubule-associated protein light

chain 3 (LC3) I/II (cat. no. 12741) was supplied by Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc. The HRP-conjugated β-actin antibody (cat. no.

ET1702-67) and goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP antibody (cat. no. HA1001)

were supplied by HUABIO. Calcein/PI Cell Viability and Cytotoxicity

Assay Kit (cat. no. C2015M), RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B),

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) (cat. no. C0038), BCA Protein

Concentration Assay Kit (cat. no. P0010S) were obtained from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. The ECL chemiluminescent

substrate (cat. no. RM02867) was obtained from ABclonal. The

CheKineTM Micro Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) Assay Kit (cat. no.

KTB1110) was provided by Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd.

LPS-induced ALI model

Male C57BL/6 mice (n=30), weighing 20-25 g and aged

8-10 weeks, were obtained from Jinan Pengyue Experimental Animal

Breeding Center (Jinan, China). The mice were housed in a

controlled environment with regulated temperature (22-24˚C) and

humidity (50-60%), maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle, and

provided with a standard diet and tap water ad libitum. SPD was

administered at doses of 10 mg/kg once daily, 10 mg/kg twice daily

and 20 mg/kg once daily (10). Mice

were pretreated with different concentrations of SPD for 3 days,

followed by the induction of ALI via intratracheal instillation of

LPS (5 mg/kg) for 24 h (11,12).

Mice were anesthetized by an i.p. injection of 0.3% sodium

pentobarbital (30 mg/kg), and then subjected to intratracheal

instillation of LPS. After 24 h, mice were euthanized via an i.p.

injection of an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg). The

present study was approved (approval no. KYDWLL-202212) by the

Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong University (Qingdao,

China). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with

the ARRIVE guidelines (13) and

complied with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory

Animals (14).

Protein concentration determination in

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF)

The collected BALF was centrifuged at 500 x g for 10

min at 4˚C. The protein concentration of the supernatant was

determined using the BCA Protein Concentration Assay Kit.

Lung tissue examination

The right lung lobe was fixed by soaking in 10%

formalin buffer at room temperature for 48 h. It was then embedded

in paraffin and sliced. The lung tissue sections (4 µm in

thickness) were stained with hematoxylin for 2 min and eosin

for 10 min at room temperature. Images were observed under a light

microscope (Olympus Corporation).

Lung wet-to-dry ratio (W/D)

Following the removal of the right lung, its wet

weight was measured and then dried in an oven at 60˚C for ~48 h.

The W/D was calculated by dividing the wet weight by the dry

weight.

Cell culture, cell cytoxicity assay

and LDH assay

The HULEC-5a (cat. no. C1402) immortalized pulmonary

microvascular endothelial cell line (cat. no. CVCL_0A11) was

purchased from Wuhan SUNNCELL Biotechnology Co., Ltd. To establish

the pyroptosis model of PMVECs, the cells were stimulated with LPS

(1 µg/ml) for 4 h, followed by treatment with nigericin (NIG) (20

µM) for 1 h. In the SPD group, the cells were pretreated with SPD

for 12 h prior to stimulation with LPS and NIG. In the LPS + NIG +

SPD + CQ group the cells were pretreated with CQ (20 µM) for 2 h

prior to stimulation with SPD. Cells were incubated with CCK-8

working solution for 2 h, followed by cell viability detection. The

necrotic cells were detected using the Calcein/PI Cell Viability

and Cytotoxicity Assay Kit, according to the manufacturer's

instructions. The cells were observed using a fluorescence

microscope (Nikon, Ti-E Live Cell Imaging System; Nikon

Corporation). LDH concentrations in cell homogenates were measured

using the CheKine™ Micro Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH)

Assay Kit. After incubation, the cells were analyzed using an

automatic microplate reader (SpectraMax i3x; Molecular Devices,

LLC).

Western blotting

Lung tissue homogenate and cell lysate were prepared

in RIPA lysis buffer. The protein concentration of the extracted

samples was determined using a BCA assay kit. Equal protein amounts

(20 µg) were analyzed using 12% SDS-PAGE electrophoresis, followed

by transfer to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5%

non-fat milk at room temperature for 2 h and then incubated

overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies against caspase-1

(1:1,000), GSDMD (1:1,000), SQSTM1/p62 (1:10,000), LC3 I/II

(1:1,000) and β-actin (1:2,000). The membrane was then incubated

with the secondary antibody (1:10,000) at room temperature for 60

min and then developed using ECL chemiluminescent substrate.

Densitometric analysis was performed using ImageJ (version 1.54;

National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± standard error

of the mean. The experiments were repeated 3 times. Unpaired

Student's t-tests were used for comparisons between two groups, and

one-way ANOVA was used for comparisons among multiple groups. Post

hoc Tukey's HSD test was applied following ANOVA to identify

specific group differences. All statistical analyses were performed

using GraphPad Prism (version 9.0.0, GraphPad Software; Dotmatics).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

SPD alleviates LPS-induced ALI

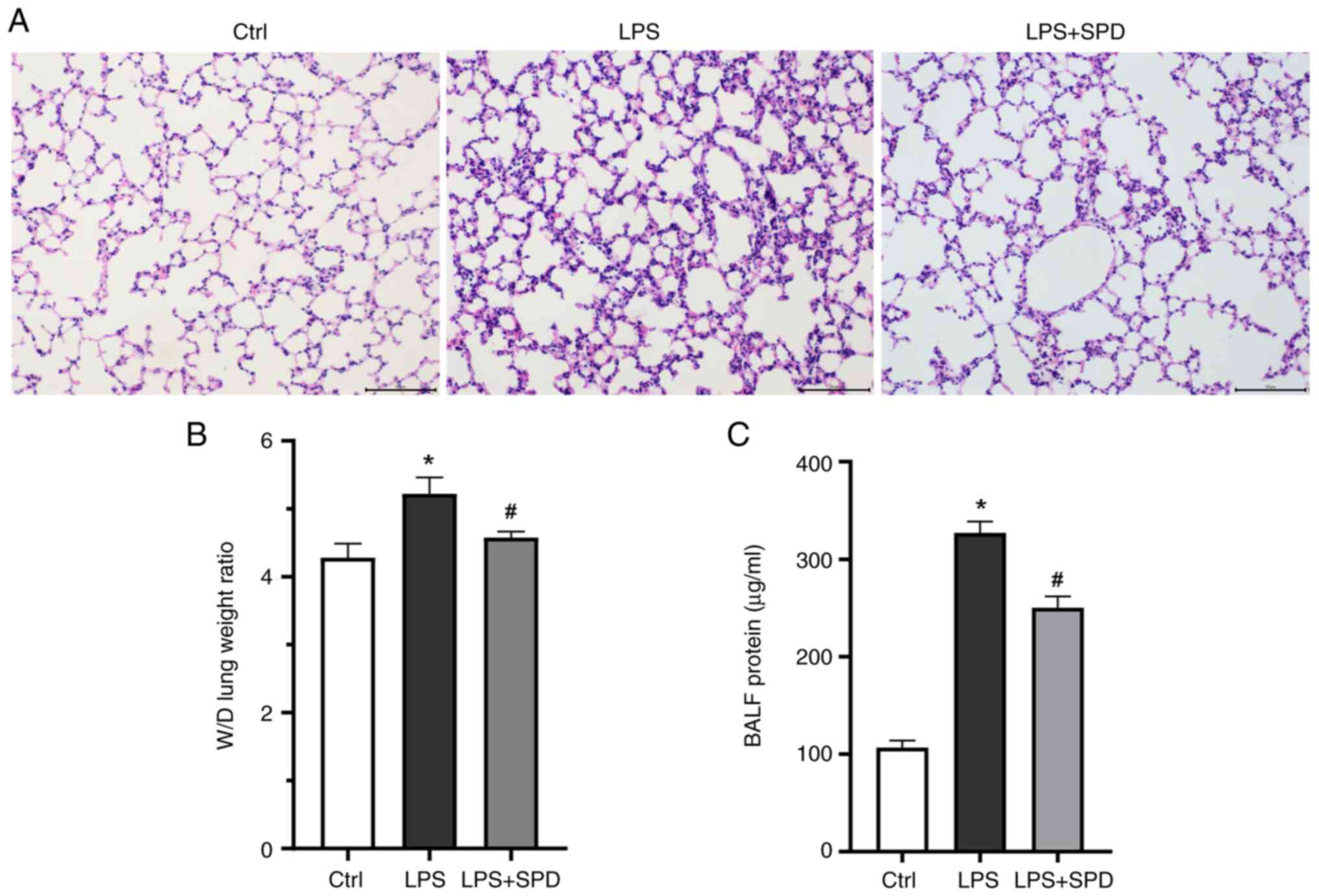

As shown in Fig.

S1, SPD at 10 mg/kg twice daily significantly alleviated lung

injury. Consequently, this dosing regimen (10 mg/kg twice daily)

was selected for all subsequent experiments. Notably, mice treated

with LPS exhibited significant lung damage, including diffuse

alveolar and interstitial edema, when compared with the control

group as revealed in Fig. 1A. SPD

pretreatment significantly reduced alveolar and interstitial edema

and inflammatory cell infiltration. Lung W/D and protein levels in

BALF were also measured (Fig. 1B

and C) to assess pulmonary vascular

endothelial permeability. SPD pretreatment significantly reduced

the lung W/D and protein in BALF. These findings indicated that SPD

pretreatment effectively reduces LPS-induced lung damage.

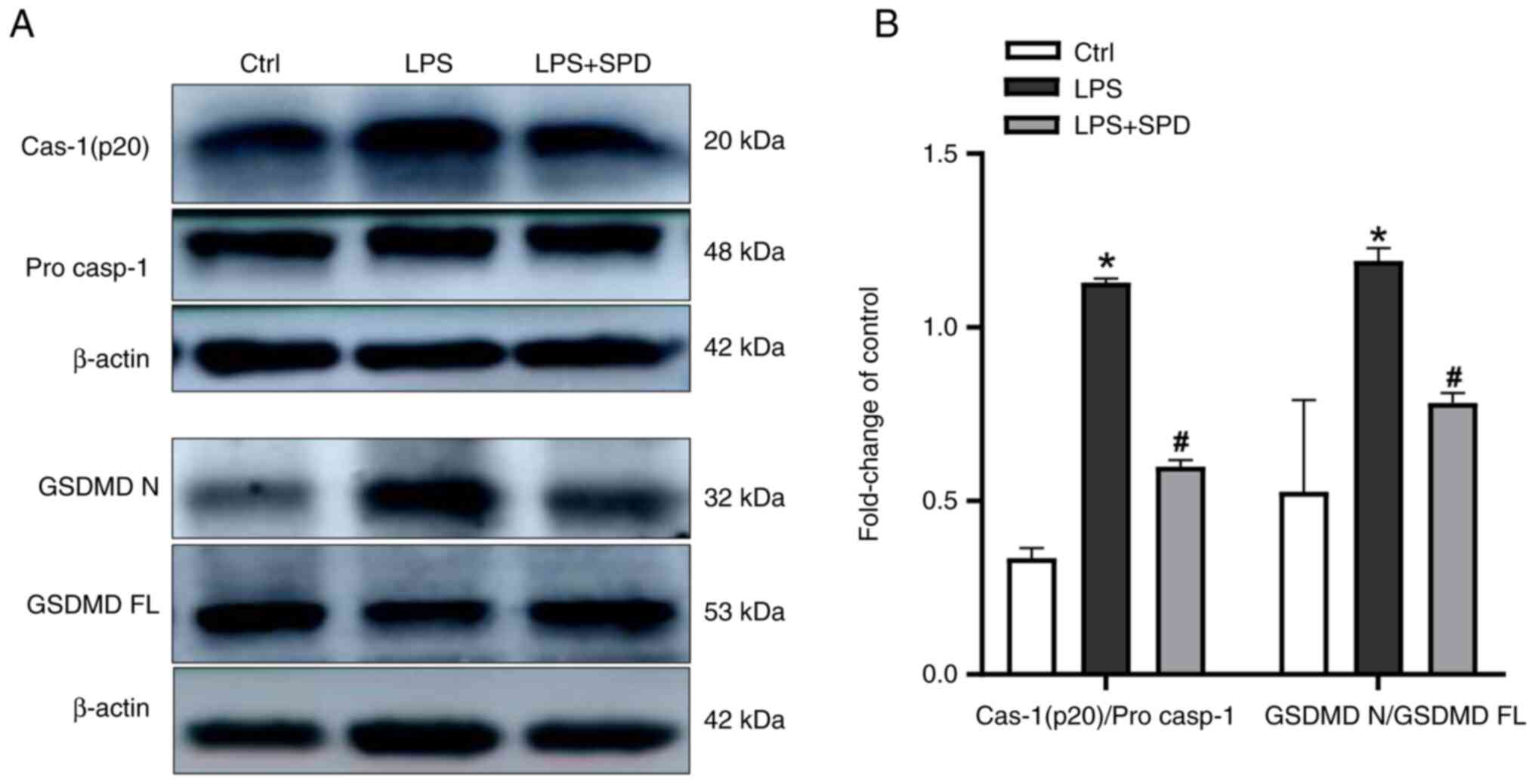

SPD alleviates lung pyroptosis

To explore whether SPD alleviates lung damage

through its effect on pyroptosis, the expression levels of

pyroptosis-related proteins were detected in lung tissue. As shown

in Fig. 2A and B, LPS administration significantly

increased the levels of cleaved caspase-1 and the gasdermin D

N-terminal (GSDMDNT) in lung tissue, as compared with

the control group. By contrast, SPD pretreatment decreased the

levels of these proteins. This suggested that SPD reduces

LPS-induced lung damage by inhibiting pyroptosis in lung

tissue.

LPS- and NIG-induced pyroptosis in

PMVECs

A concentration-dependent NIG screening (5, 10, 20,

30 and 40 µM) was performed on LPS-primed (1 µg/ml, 4 h) PMVECs

(15-17).

As shown in Fig. S2A, 20 µM NIG

was identified as the optimal concentration, balancing pyroptosis

induction with preserved assay sensitivity, and was thus employed

in further studies. Following SPD pretreatment (20, 40, 60, 80, 100

and 200 µM) and sequential LPS/NIG challenge, CCK-8 analysis

(Fig. S2B) revealed maximal

viability enhancement at 40 µM. Absence of additional benefit at

higher concentrations (80-200 µM) established 40 µM as the optimal

concentration for subsequent experimental applications.

SPD attenuates endothelial cell

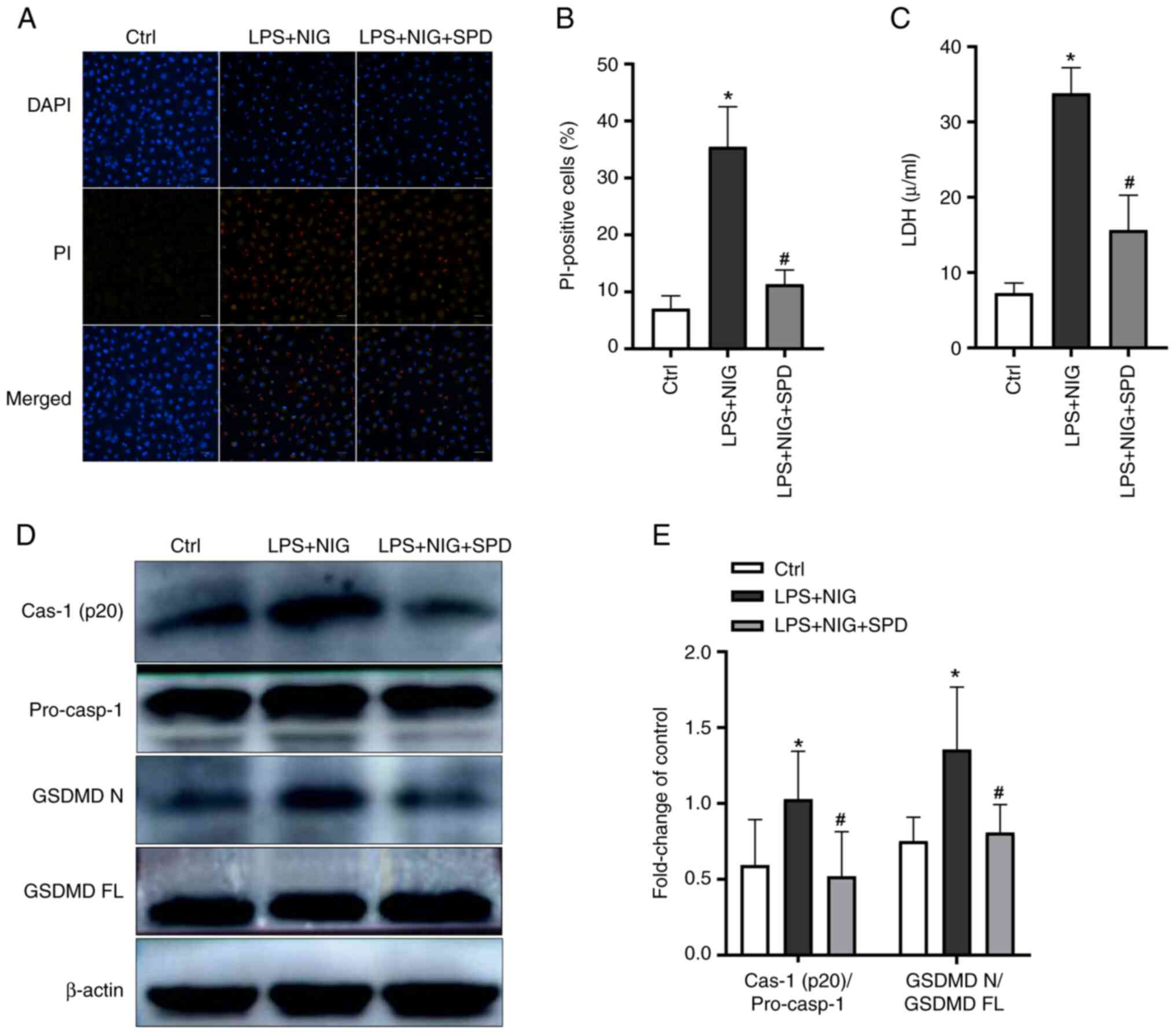

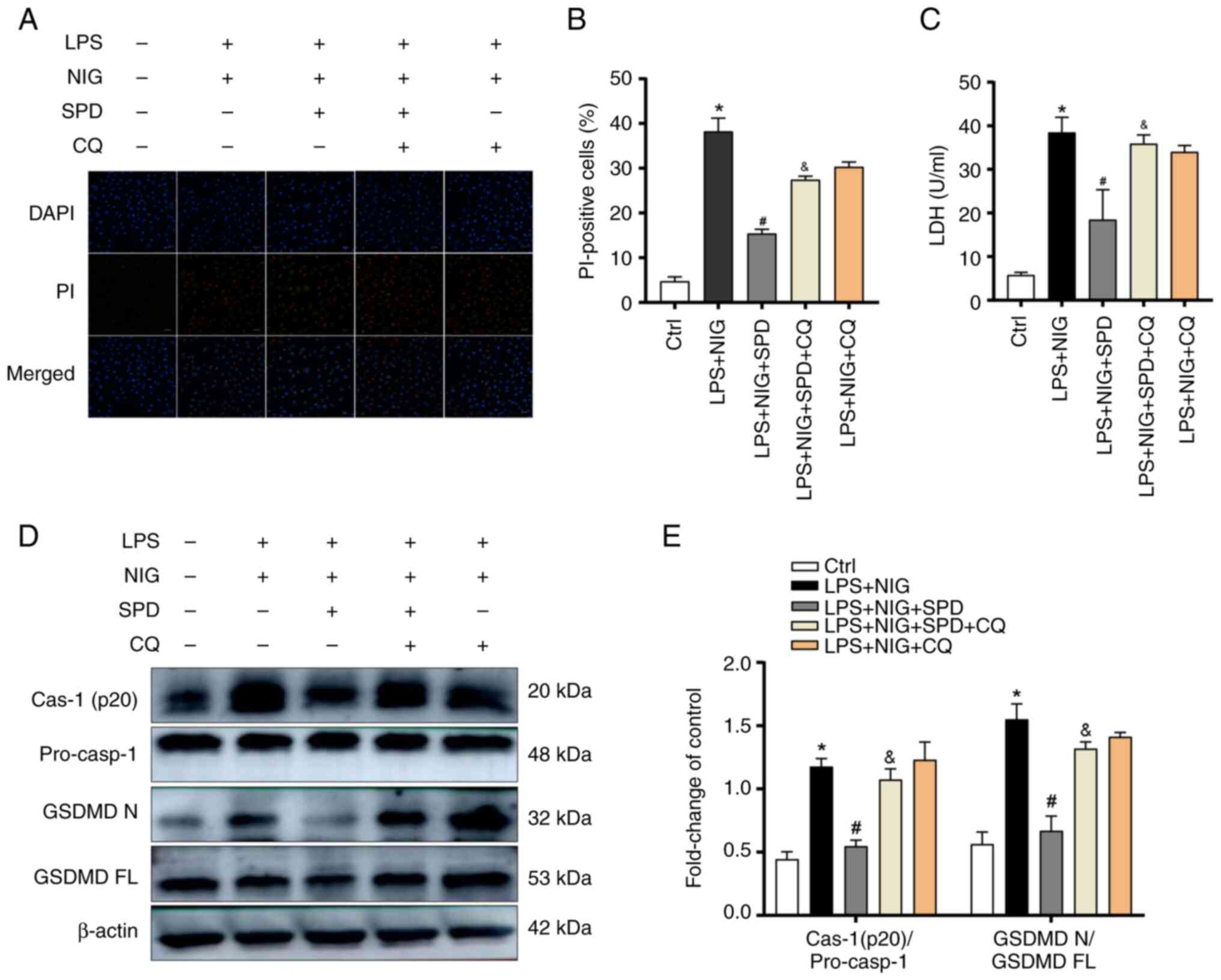

pyroptosis

To investigate the effect of SPD on endothelial cell

pyroptosis, cells were treated with LPS and NIG. Pyroptotic cells

form membrane pores that permit extracellular dyes, such as

propidium iodide (PI), to enter and stain the nucleus (18). As revealed in Fig. 3A and B, a significant increase in the percentage

of PI-positive cells was observed following stimulation with LPS

and NIG. In addition, the stimulation with LPS and NIG led to a

significant increase in the release of LDH from endothelial cells

(Fig. 3C). Following stimulation

with LPS and NIG, the expression levels of cleaved caspase-1 and

GSDMDNT increased in endothelial cells (Fig. 3D and E). However, SPD reduced all LPS- and

NIG-induced effects.

| Figure 3SPD reduces pyroptosis in PMVECs.

PMVECs were first treated with 40 µm SPD for 12 h, followed by

exposure to LPS and NIG. (A) Pyroptotic cells were identified

through PI staining, with nuclei stained blue using DAPI. Scale

bars, 50 µm. (B) Percentages of PI-positive cells. (C) LDH

concentrations in cell homogenates were measured using the

CheKine™ LDH Assay Kit. (D) Western blotting was

performed to detect cleaved caspase-1 (p20) and GSDMDNT

in PMVECs. (E) Semi-quantification of (D). The results are

presented as the mean ± SD. *P<0.05, the LPS + NIG

group vs. the control group; #P<0.05, the LPS + NIG +

SPD group vs. the LPS + NIG group. SPD, spermidine; PMVECs,

pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells; LPS, lipopolysaccharide;

NIG, nigericin; PI, propidium iodide; DAPI,

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

GSDMDNT or GSDMD N, gasdermin D N-terminal; GSDMD FL,

gasdermin D full length; Ctrl, control. |

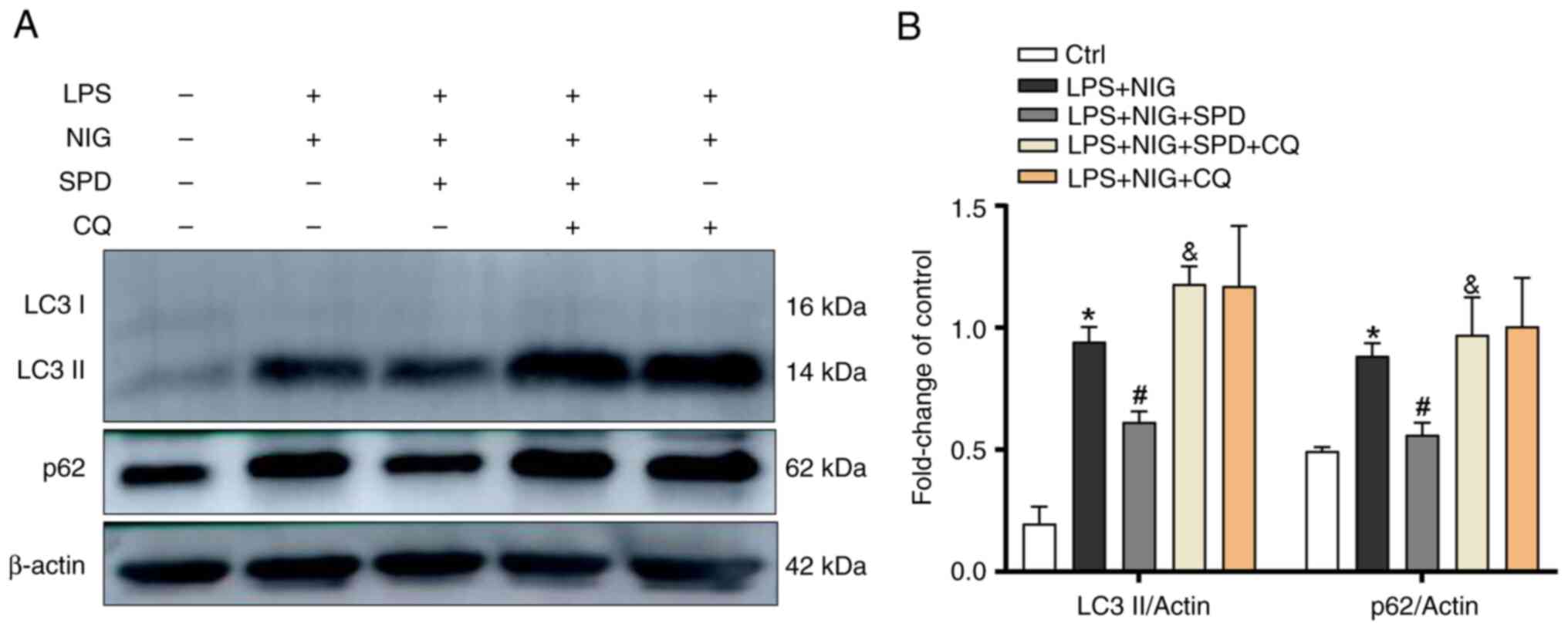

SPD enhances the disrupted autophagic

process in endothelial cells undergoing LPS- and NIG-induced

pyroptosis

SPD promotes autophagy, which can inhibit pyroptosis

through different mechanisms. It was examined whether SPD restores

autophagy in LPS- and NIG-treated endothelial cells. This was

performed by measuring the levels of autophagic proteins LC3-II and

p62. As shown in Fig. 4A and

B, the levels of autophagy markers

LC3-II and p62 increased in LPS- and NIG-treated endothelial cells.

Following SPD treatment, the levels of LC3-II and p62 in

endothelial cells affected by LPS and NIG decreased. Notably, the

addition of CQ to the LPS + NIG + SPD group further elevated LC3-II

and p62 levels, suggesting that the protective effect of SPD was

attenuated by CQ-mediated autophagy blockade. These results

indicated that LPS and NIG inhibited autophagic flux in PMVECs,

while SPD successfully restored this disrupted process.

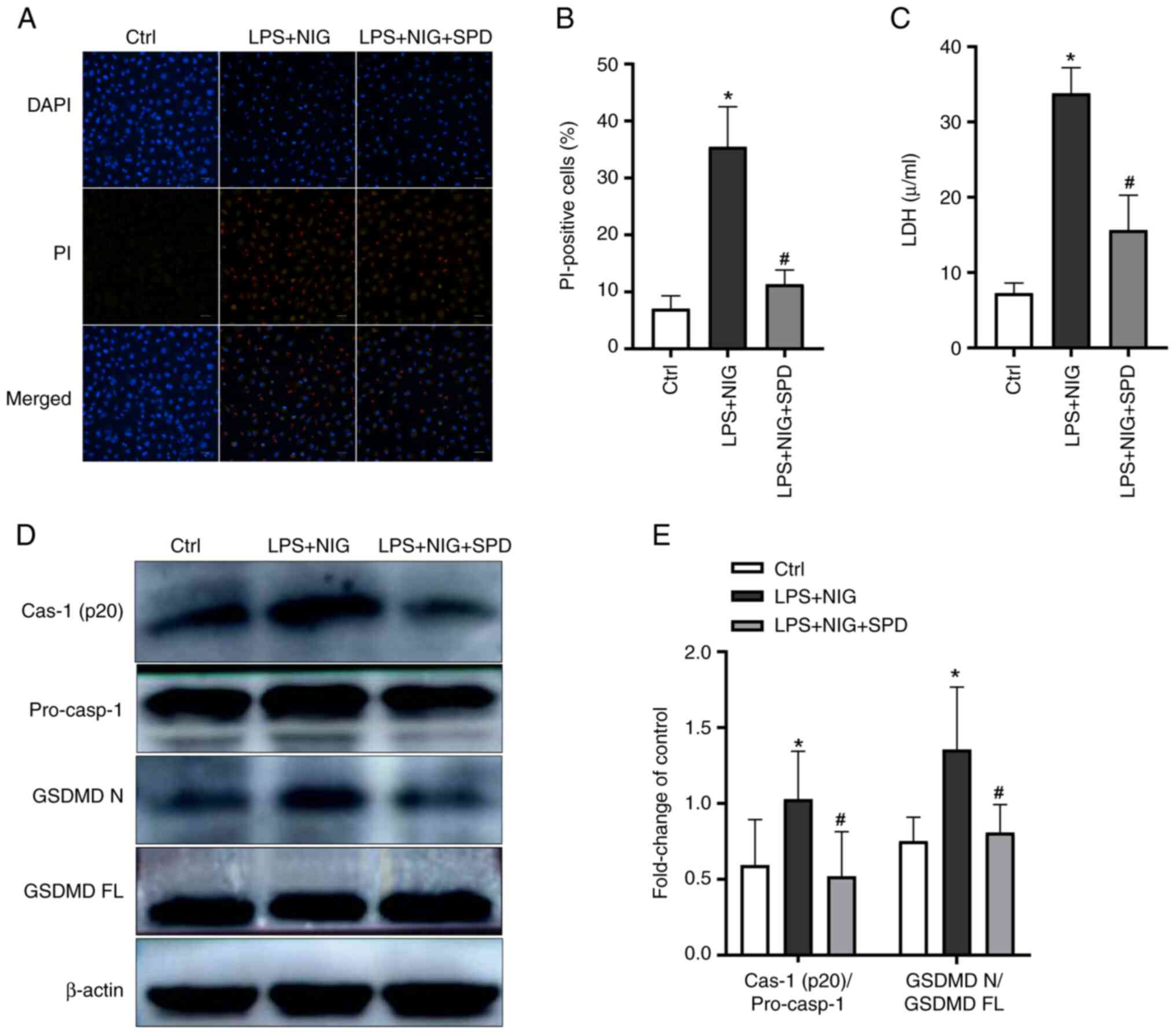

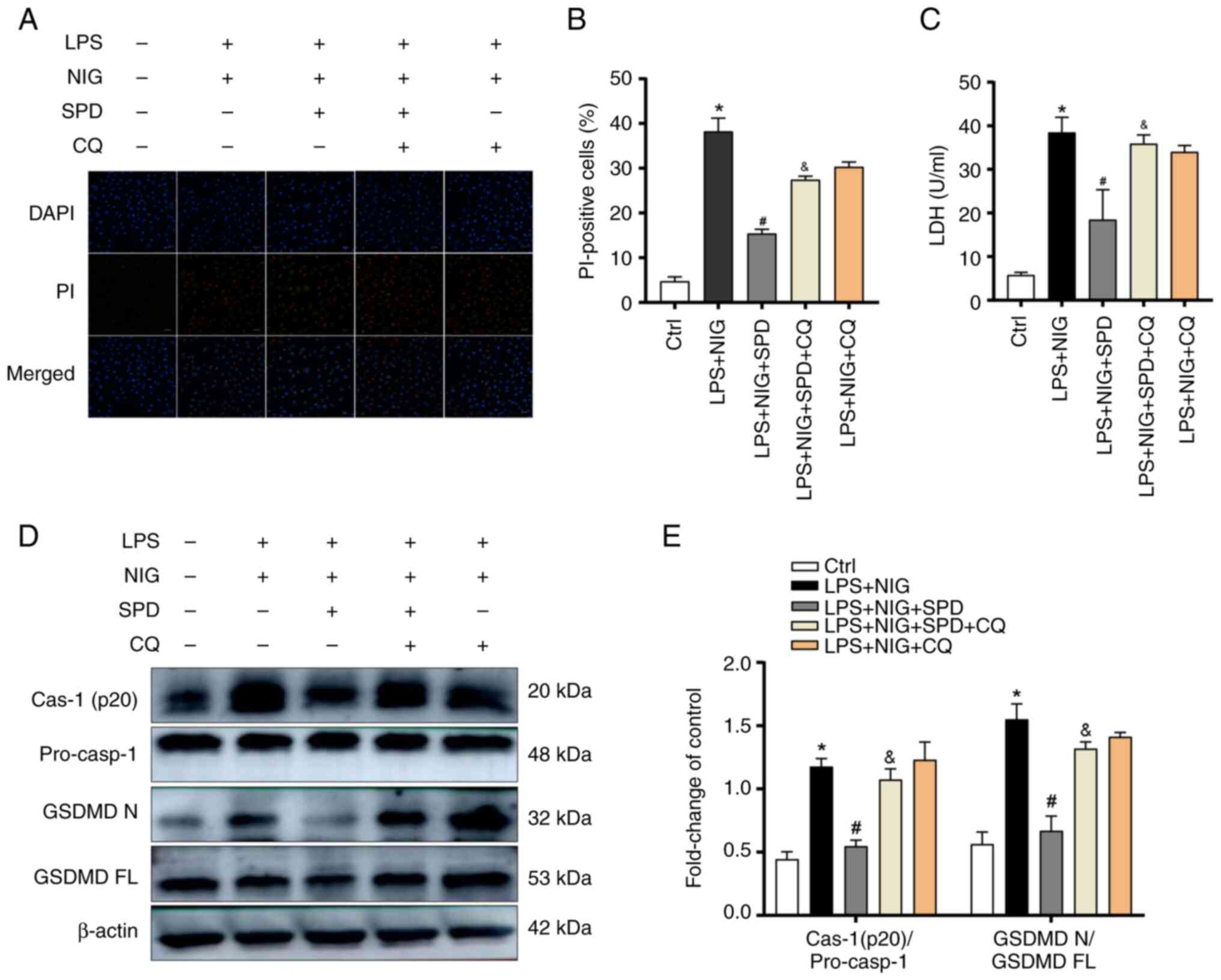

SPD reduces pyroptosis in LPS- and

NIG-treated endothelial cells by restoring the damaged autophagic

flux

To better understand this process, the autophagy

inhibitor CQ was used to block autophagic flux. As revealed in

Fig. 5, the LPS + NIG + SPD + CQ

group had more PI staining-positive cells and higher LDH release

than the LPS + NIG + SPD group. In addition, this group exhibited

increased levels of cleaved caspase-1 and GSDMDNT. These

findings indicated that by restoring autophagic flux, SPD mitigates

pyroptosis in LPS- and NIG-treated PMVECs.

| Figure 5SPD reduces PMVEC pyroptosis caused by

LPS and NIG by restoring the impaired autophagic flux. (A)

Pyroptotic cells were labeled red using PI staining, while the cell

nuclei were stained blue with DAPI. Scale bars, 50 µm. (B)

Percentages of PI-positive cells. (C) LDH concentrations in cell

homogenates were measured using the CheKine™ LDH Assay

Kit. (D) Western blotting was conducted to assess the levels of

cleaved caspase-1 (p20) and GSDMDNT in PMVECs. (E)

Semi-quantification of (D). Results are presented as the mean ± SD.

*P<0.05, the LPS + NIG group vs. the control group;

#P<0.05, the LPS + NIG + SPD group vs. the LPS + NIG

group; &P<0.05, the LPS + NIG + SPD + CQ group

vs. LPS + NIG + SPD group. SPD, spermidine; PMVECs, pulmonary

microvascular endothelial cells; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NIG,

nigericin; PI, propidium iodide; DAPI,

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase;

GSDMDNT or GSDMD N, gasdermin D N-terminal; GSDMD FL,

gasdermin D full length; CQ, chloroquine; Cas-1, caspase-1;

pro-casp-1, pro-caspase-1; Ctrl, control. |

Discussion

SPD is a key metabolic regulator produced from the

breakdown of ornithine in mammals, playing significant roles in

various physiological and pathological processes (19). It has been shown to be a potent

inducer of autophagy, contributing to anti-aging and antioxidant

effects, inflammation reduction and apoptosis inhibition (20-22).

However, the therapeutic potential of SPD for ameliorating ALI has

not been previously reported. Hence, exploration of the therapeutic

effects of SPD in ALI may provide novel insights for clinical

applications.

Pyroptosis is recognized as the main mechanism

through which LPS induces endothelial cell death. Early in the

process of inflammation, endothelial cells undergo pyroptotic death

to remove damaged cells. However, if this process is not

controlled, it can damage the vascular endothelial barrier

(23-25).

Pyroptosis is a distinct form of programmed cell death that depends

on caspases and gasdermins. The key effector, GSDMD, is cleaved by

caspases into two fragments: The N-terminal fragment

(GSDMDNT) and the C-terminal fragment

(GSDMDCT). The GSDMDNT binds to cell

membranes to create pores, resulting in cell destruction (26). The present findings were aligned

with those of previous studies (23-26),

showing an increase in GSDMDNT and pro-caspase-1

expression in the lungs of mice with LPS-induced ALI and pulmonary

vascular cells.

There are three main types of autophagy:

Macroautophagy, microautophagy and chaperone-mediated autophagy.

Macroautophagy is considered the primary form. During this process,

the membrane of the autophagic vesicle encloses cellular

components, leading to the formation of an autophagosome. The

autophagosome then merges with a lysosome to create an

autophagolysosome, where the cellular contents are broken down.

This sequence of events is called autophagic flux (27). Studies have demonstrated that

activating autophagy mitigates sepsis and attenuates organ

dysfunction by suppressing pyroptosis (25,28,29).

To date, therapies targeting both autophagy and pyroptosis for

treating ARDS have not yet been reported in clinical practice.

p62, or SQSTM1, is a key target of autophagy; it

interacts with LC3 on the autophagosome membrane, gets incorporated

into the autophagosome, and is eventually degraded (8). The disruption of autophagy can cause

the buildup of p62 protein. In the pyroptosis of LPS- and

NIG-treated PMVECs, higher levels of p62 and LC3 II were observed,

which suggested that autophagic flux was inhibited in PMVECs.

Previous research has shown that autophagy negatively regulates

cellular pyroptosis. Pu et al (30) found that autophagy inhibition

increased macrophage pyroptosis in a Pseudomonas

aeruginosa-induced sepsis model. In addition, a previous study

showed that activating autophagy reduces neuronal cell pyroptosis

in a mouse model of brain injury (31). To examine the effects of SPD, a

potent autophagy inducer, on pyroptosis and autophagy in PMVECs,

the cells were treated in vitro with SPD. It was observed

that SPD attenuated LPS/nigericin-induced pyroptosis and rescued

the suppressed autophagic flux in PMVECs. CQ has been revealed to

block autophagic flux by inhibiting the fusion of autophagosomes

with lysosomes (32). To

investigate whether the SPD-mediated attenuation of PMVEC

pyroptosis is dependent on the enhancement of autophagic flux,

autophagic flux was inhibited using CQ in PMVECs. When autophagic

flux was pharmacologically blocked by CQ, the protective effect of

SPD against PMVEC pyroptosis was significantly abrogated. These

findings collectively indicated that SPD mitigates PMVEC pyroptosis

through the potentiation of autophagic flux.

In conclusion, in the present study it was

demonstrated that SPD alleviates LPS-induced ALI by suppressing

pyroptosis in PMVECs through an autophagy-dependent mechanism.

These findings provide novel insights for the clinical management

of ARDS. However, it should be noted that the present study has

certain limitations. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) is a well-established

downstream effector of caspase-1(33), and although it was demonstrated that

SPD suppresses caspase-1 activation, additional validation for this

specific cytokine within the scope of the present study was not

performed. Evidence indicates that SPD can induce autophagy through

the adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

(AMPK)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway to improve

cardiac function and reverse B-cell senescence by controlling eIF5A

hypusination (21,22). Future research should focus on

elucidating whether SPD exerts its protective effects against ALI

and PMVEC pyroptosis by inducing autophagy through the AMPK/mTOR

signaling pathway, H5A phosphorylation or alternative mechanisms,

along with its effects on IL-1β maturation and secretion. Further

clinical trials are warranted to validate the therapeutic efficacy

of SPD in human patients.

Supplementary Material

Effect of SPD at various

concentrations on LPS-induced acute lung injury. H&E staining

of lung tissue sections showing that SPD (10 mg/kg twice daily)

pretreatment alleviated LPS-induced lung injury. Scale bars, 100

μm. SPD, spermidine; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; H&E,

hematoxylin & eosin; Ctrl, control.

Protective effect of SPD concentration

pretreatment on LPS/NIG-induced pyroptosis. (A) PMVECs were treated

with LPS (1 μg/ml) for 4 h, followed by incubation with

different concentrations of NIG (5, 10, 20, 30 and 40 μM).

Cell viability was measured using the CCK-8 assay 1 h following the

addition of NIG. *P<0.05, the NIG (20 μM)

group vs. the NIG (0 μM) group. (B) Pulmonary vascular

endothelial cells were pretreated with different concentrations of

SPD (20, 40, 60, 80, 100 and 200 μM), followed by sequential

treatment with LPS and NIG. Cell viability was assessed using the

CCK-8 assay 1 h after the final treatment. *P<0.05,

the SPD (40 μM) group vs. the SPD (0 μM) group. LPS,

lipopolysaccharide; NIG, nigericin; PMVECs, pulmonary microvascular

endothelial cells; CCK-8, Cell Counting Kit-8; SPD,

spermidine.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by grants from the

Scientific Research Foundation of Qilu Hospital (Qingdao) (grant

no. QDKY2020RX05) and Qingdao Science and Technology Project (grant

no. 25-1-5-smjk-9-nsh).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

XX designed the study, critically reviewed and

edited the draft, supervised the study, and acquired funding. XZ

conducted the investigation, performed data collection and analysis

and drafted the manuscript. HL worked on partial data collection

and analysis, and participated in manuscript revision. XX and XZ

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved (approval no.

KYDWLL-202212) by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital of Shandong

University (Qingdao, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

ARDS Definition Task Force. Ranieri VM,

Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, Ferguson ND, Caldwell E, Fan E,

Camporota L and Slutsky AS: Acute respiratory distress syndrome:

The berlin definition. JAMA. 307:2526–2533. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Fan E, Brodie D and Slutsky AS: Acute

respiratory distress syndrome: Advances in diagnosis and treatment.

JAMA. 319:698–710. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Matthay MA and Zemans RL: The acute

respiratory distress syndrome: Pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev

Pathol. 6:147–163. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Matthay MA, Ware LB and Zimmerman GA: The

acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 122:2731–2740.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Wang L, Mehta S, Brock M and Gill SE:

Inhibition of murine pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell

apoptosis promotes recovery of barrier function under septic

conditions. Mediators Inflamm. 2017(3415380)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gill SE, Rohan M and Mehta S: Role of

pulmonary microvascular endothelial cell apoptosis in murine

sepsis-induced lung injury in vivo. Respir Res.

16(109)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Moreno-Gonzalez G, Vandenabeele P and

Krysko DV: Necroptosis: A novel cell death modality and its

potential relevance for critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit

Care Med. 194:415–428. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Mizushima N and Komatsu M: Autophagy:

Renovation of cells and tissues. Cell. 147:728–741. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Guo R, Wang H and Cui N: Autophagy

regulation on pyroptosis: Mechanism and medical implication in

sepsis. Mediators Inflamm. 2021(9925059)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gao M, Zhao W, Li C, Xie X, Li M, Bi Y,

Fang F, Du Y and Liu X: Spermidine ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty

liver disease through regulating lipid metabolism via AMPK. Biochem

Biophys Res Commun. 505:93–98. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Ehrentraut H, Weisheit CK, Frede S and

Hilbert T: Inducing acute lung injury in mice by direct

intratracheal lipopolysaccharide instillation. J Vis Exp: Jul 6,

2019 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

12

|

D'Alessio FR: Mouse models of acute lung

injury and ARDS. Methods Mol Biol. 1809:341–350. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A,

Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl

U, et al: The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for

reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 18(e3000410)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

National Research Council: Committee for

the Update of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals:

Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th edition.

National Academies Press, Washington, DC, pp1-246, 2011.

|

|

15

|

Yan S, Yu L, Chen Z, Xie D, Huang Z and

Ouyang S: ZBP1 promotes hepatocyte pyroptosis in acute liver injury

by regulating the PGAM5/ROS pathway. Ann Hepatol.

29(101475)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Liang Q, Cai W, Zhao Y, Xu H, Tang H, Chen

D, Qian F and Sun L: Lycorine ameliorates bleomycin-induced

pulmonary fibrosis via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and

pyroptosis. Pharmacol Res. 158(104884)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Li Q, Tan Y, Chen S, Xiao X, Zhang M, Wu Q

and Dong M: Irisin alleviates LPS-induced liver injury and

inflammation through inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome and NF-κB

signaling. J Recept Signal Transduct Res. 41:294–303.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Zhang X, Zhang P, An L, Sun N, Peng L,

Tang W, Ma D and Chen J: Miltirone induces cell death in

hepatocellular carcinoma cell through GSDME-dependent pyroptosis.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 10:1397–1413. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Pegg AE: Mammalian polyamine metabolism

and function. IUBMB Life. 61:880–894. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Madeo F, Eisenberg T, Büttner S,

Ruckenstuhl C and Kroemer G: Spermidine: A novel autophagy inducer

and longevity elixir. Autophagy. 6:160–162. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Zhang H, Alsaleh G, Feltham J, Sun Y,

Napolitano G, Riffelmacher T, Charles P, Frau L, Hublitz P, Yu Z,

et al: Polyamines control eIF5A hypusination, TFEB translation, and

autophagy to reverse B cell senescence. Mol Cell. 76:110–125.e9.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Yan J, Yan JY, Wang YX, Ling YN, Song XD,

Wang SY, Liu HQ, Liu QC, Zhang Y, Yang PZ, et al:

Spermidine-enhanced autophagic flux improves cardiac dysfunction

following myocardial infarction by targeting the AMPK/mTOR

signalling pathway. Br J Pharmacol. 176:3126–3142. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Shi J, Gao W and Shao F: Pyroptosis:

Gasdermin-mediated programmed necrotic cell death. Trends Biochem

Sci. 42:245–254. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Brigham KL and Meyrick B: Endotoxin and

lung injury. Am Rev Respir Dis. 133:913–927. 1986.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Singla S and Machado RF: Death of the

endothelium in sepsis: Understanding the crime scene. Am J Respir

Cell Mol Biol. 59:3–4. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Broz P, Pelegrín P and Shao F: The

gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation.

Nat Rev Immunol. 20:143–157. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Liu S, Yao S, Yang H, Liu S and Wang Y:

Autophagy: Regulator of cell death. Cell Death Dis.

14(648)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mitra S, Exline M, Habyarimana F, Gavrilin

MA, Baker PJ, Masters SL, Wewers MD and Sarkar A: Microparticulate

caspase 1 regulates gasdermin D and pulmonary vascular endothelial

cell injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 59:56–64. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Wang YC, Liu QX, Zheng Q, Liu T, Xu XE,

Liu XH, Gao W, Bai XJ and Li ZF: Dihydromyricetin alleviates

sepsis-induced acute lung injury through inhibiting NLRP3

inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis in mice model. Inflammation.

42:1301–1310. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Pu Q, Gan C, Li R, Li Y, Tan S, Li X, Wei

Y, Lan L, Deng X, Liang H, et al: Atg7 deficiency intensifies

inflammasome activation and pyroptosis in Pseudomonas

sepsis. J Immunol. 198:3205–3213. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Gao C, Yan Y, Chen G, Wang T, Luo C, Zhang

M, Chen X and Tao L: Autophagy activation represses pyroptosis

through the IL-13 and JAK1/STAT1 pathways in a mouse model of

moderate traumatic brain injury. ACS Chem Neurosci. 11:4231–4239.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Mauthe M, Orhon I, Rocchi C, Zhou X, Luhr

M, Hijlkema KJ, Coppes RP, Engedal N, Mari M and Reggiori F:

Chloroquine inhibits autophagic flux by decreasing

autophagosome-lysosome fusion. Autophagy. 14:1435–1455.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Xu J and Núñez G: The NLRP3 inflammasome:

Activation and regulation. Trends Biochem Sci. 48:331–344.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|