Introduction

Neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction (NLUTD)

is a common complication in individuals with conditions such as

spinal cord injuries, multiple sclerosis (MS) and other neurologic

disorders, often presenting with symptoms of overactive bladder,

incontinence and voiding dysfunction (1,2).

Anticholinergic medications, which inhibit muscarinic receptors to

reduce detrusor muscle overactivity, are frequently employed as

first-line pharmacological interventions to manage these symptoms

(1,3). However, the widespread distribution of

muscarinic receptors in the central nervous system raises concerns

regarding potential cognitive side effects, particularly in

vulnerable populations (2,4).

Cognitive impairments, including memory loss,

attention deficits and decreased processing speed, have been

reported with anticholinergic use, especially in older populations

(2,5,6).

Studies show that anticholinergic medications cross the blood-brain

barrier, contributing to brain atrophy and increased dementia risk

(2,7). A cohort study by Wang et al

(2) found that cumulative exposure

to bladder-specific anticholinergics was associated with an

elevated risk of dementia, emphasizing the need for careful

therapeutic balancing between symptom management and cognitive

safety.

In cognitive research, functions are commonly

categorized into key domains: Memory, attention and processing

speed, executive functions, visuospatial ability and global

cognition (8). NLUTD studies often

use standardized tools to assess these domains. For instance, the

Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) is a 30-point scale examining

orientation, recall, attention, language and constructional ability

(9). The Symbol Digit Modalities

Test (SDMT) is widely used, particularly in neurological

populations, to evaluate attention and processing speed (10). More specialized tests, such as the

Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) or the Trail Making Test, are used

to evaluate executive functioning, and instruments such as the

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) assess multiple domains,

including visuospatial abilities (9). By briefly outlining these tools and

domains, a clear conceptual framework that supports analyses of

cognitive outcomes was established.

In populations with neurogenic bladder dysfunction,

the cognitive burden of anticholinergics may be particularly

problematic due to pre-existing neurological vulnerabilities.

Sakakibara et al (4)

demonstrated that although some anticholinergic agents, such as

imidafenacin, may present lower cognitive risks, others such as

oxybutynin and tolterodine have been linked to significant declines

in memory and executive function. Similarly, Morrow et al

(7) highlighted a substantial

impact on processing speed and memory in patients with MS treated

with anticholinergic medications, with impairments detected using

standardized cognitive tests.

Despite their therapeutic efficacy in alleviating

NLUTD symptoms, the long-term cognitive consequences of

anticholinergic medications remain a critical area of

investigation. Emerging evidence suggests that alternative

treatments, such as β3-adrenergic agonists like mirabegron, may

provide effective symptom control with fewer cognitive side

effects, as demonstrated in comparative studies (1). Trbovich et al (1) found improved cognitive outcomes and

comparable efficacy when switching from anticholinergics to

mirabegron in individuals with neurogenic bladder dysfunction.

The present systematic review and meta-analysis aim

to comprehensively evaluate the cognitive effects of

anticholinergic medications in patients with NLUTD, synthesizing

data from clinical trials and observational studies. By examining

the extent and nature of cognitive impairments across various

populations and drug types, the present study seeks to inform

clinical decision-making and highlight potential therapeutic

alternatives that minimize cognitive risks.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present study is a systematic review and

meta-analysis conducted to evaluate the cognitive effects of

anticholinergic medications in patients with NLUTD. The review

adhered to the guidelines outlined in the PRISMA statement to

ensure comprehensive reporting and transparency. The study protocol

was registered in accordance with best practices for meta-analyses

(11).

Search strategy and selection

criteria

A systematic search was conducted across major

electronic databases, including PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Embase (https://www.embase.com), Cochrane Library (https://www.cochrane.org/) and Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), from inception to February

2025. The search terms included combinations of the following:

‘anticholinergics’, ‘cognitive impairment’, ‘neurogenic bladder’,

‘neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction’, ‘cognition’ and

‘urinary tract dysfunction’. No language restrictions were applied.

The reference lists of included studies and relevant review

articles were manually screened to identify additional studies.

Inclusion criteria were: i) Studies assessing the cognitive effects

of anticholinergic medications in patients with NLUTD, ii)

randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, case-control studies

and cross-sectional studies, iii) studies reporting cognitive

outcomes, including memory, executive function, or overall

cognition, and iv) only studies involving anticholinergic

monotherapy delivered via oral administration were eligible for

inclusion. Exclusion criteria were: i) Studies not involving NLUTD

or anticholinergic medications, ii) animal or in vitro

studies, iii) conference abstracts, case reports and reviews

without primary data, and iv) studies using combination therapies

(for example, anticholinergics plus β3-agonists), non-oral

administration routes (for example, transdermal patches), and

studies enrolling participants with clinically diagnosed cognitive

impairment at baseline to reduce potential confounding.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (HZ and YW) screened

titles and abstracts to identify relevant studies. Discrepancies

were resolved through discussion. Full-text articles were retrieved

and evaluated against the inclusion criteria. The following data

were extracted using a standardized form: i) Study characteristics:

author, year, study design, sample size and population

characteristics; ii) intervention details: Type, dosage and

duration of anticholinergic use; iii) cognitive outcomes: type of

cognitive test used (for example, MMSE and SDMT); and iv) risk of

bias and confounders: assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

(NOS).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3. The primary outcome

was the standardized mean difference (SMD) in cognitive test scores

between patients receiving anticholinergics and those not exposed

to the medications. A random-effects model was used due to the

expected heterogeneity across studies, with effect sizes reported

as point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Heterogeneity was assessed using the Q statistic and precision

interval analysis. Tau-squared (τ²) was calculated to estimate

between-study variance. Instead of relying solely on I² to quantify

heterogeneity, the present meta-analysis employed precision

interval analysis. While I² is commonly used to measure the

percentage of variability due to heterogeneity, it has limitations,

particularly when the number of studies is small or when effect

sizes vary widely (12). Precision

interval analysis focuses on the width of the CI and how much

uncertainty surrounds the estimate, offering a more robust measure

of how precise the combined effect size is. The width of the

precision interval indicates whether the heterogeneity among

studies affects the reliability of the meta-analysis conclusion

(13). Sensitivity analyses were

conducted by excluding studies with a high risk of bias and

recalculating pooled estimates. Subgroup and moderator analyses

were performed based on population characteristics (for example,

age and sex groups) and type of cognitive test. The Begg and

Mazumdar rank correlation test and Egger's regression intercept

were used to identify publication bias. The Classic fail-safe N and

Orwin's fail-safe N were calculated to assess the robustness of the

results. Forest plots were generated to visualize effect sizes, and

the funnel plot was used to assess publication bias. The

significance of heterogeneity was tested using P-values, where

P<0.05 was considered to indicate significant heterogeneity.

Results

Study selection

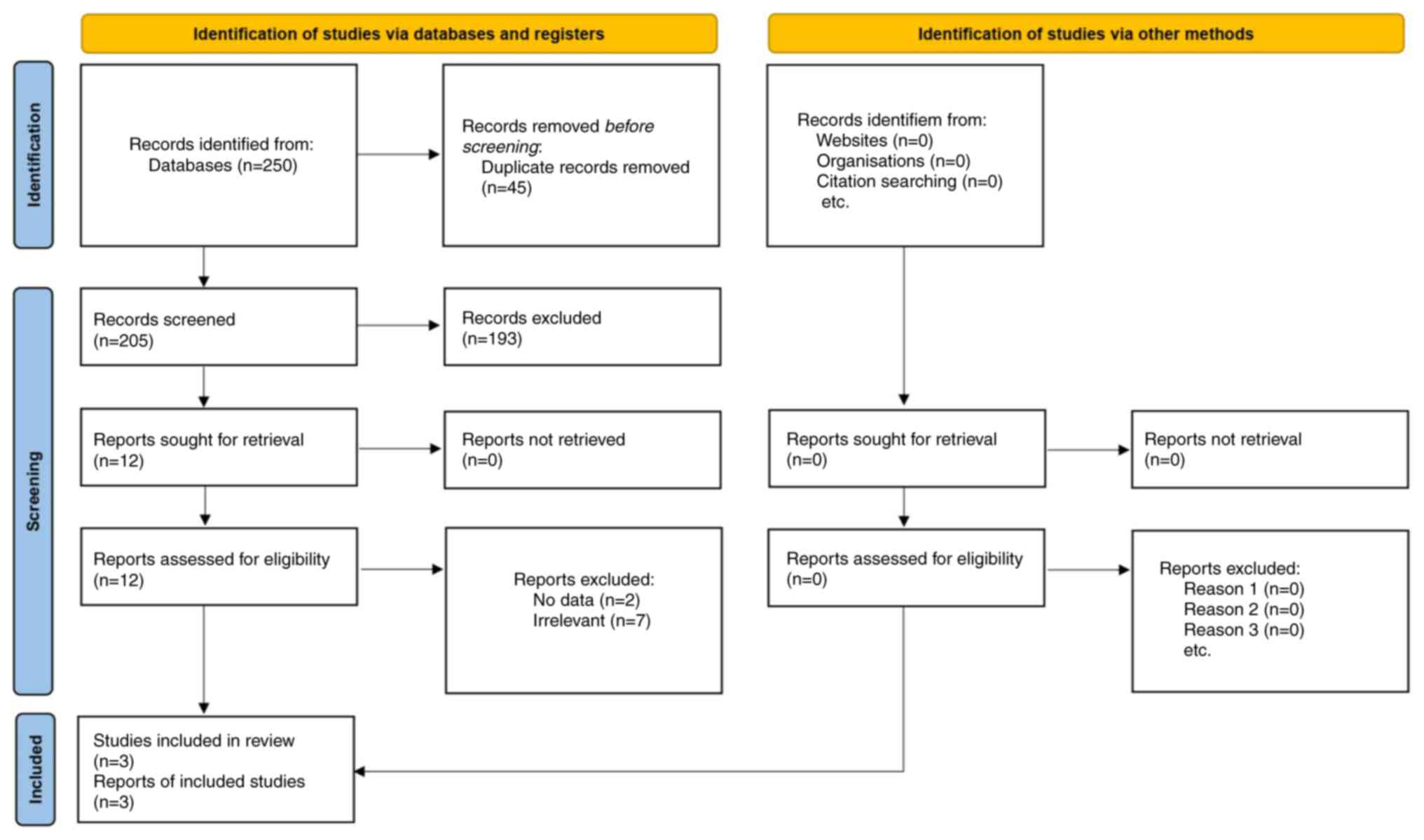

A systematic literature search of four major

electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library and Scopus)

yielded 250 potentially relevant articles. After removing 45

duplicates, 205 articles underwent title and abstract screening, of

which 12 were considered for full-text review. A total of 9

articles were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria (for

example, lack of NLUTD focus, no anticholinergic intervention, or

insufficient cognitive data). Ultimately, 3 studies (4,7,14)

fulfilled the eligibility criteria, providing 22 independent

comparisons. Two additional studies were excluded because they did

not report sufficient data for the analysis (1,2). The

entire selection process followed PRISMA guidelines and is outlined

in Fig. 1.

General characteristics of included

studies

The selected studies included 139 participants

across various clinical settings, focusing on patients with NLUTD

due to conditions such as spinal cord injury (SCI), MS and

neurologic overactive bladder (OAB). The mean age of participants

ranged from 25 to 70 years, with follow-up durations between 3 and

12 weeks. The studies examined both traditional anticholinergic

agents (for example, oxybutynin and tolterodine) and newer,

selective agents (for example, solifenacin and imidafenacin).

Treatment durations ranged from 3 months to 12 weeks. Cognitive

outcomes were assessed using standardized tests, including the

SDMT, MMSE and FAB (Table I).

| Table IStudy characteristics and

interventions in the meta-analysis. |

Table I

Study characteristics and

interventions in the meta-analysis.

| First author/s,

year | Study design | Sample size (n) | Population

characteristics | Anticholinergic

agent(s) | Dosage | Duration of

treatment | Cognitive tests

used | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Krebs et al,

2017 | Prospective

controlled cohort | 29 | Patients with spinal

cord injury with neurogenic lower urinary tract dysfunction during

post-acute rehabilitation phase | Solifenacin,

fesoterodine, darifenacin | Variable, based on

agent | 3 months | Verbal learning test,

Stroop test, word fluency test | (14) |

| Morrow et

al, 2018 | Randomized

controlled trial | 69 | Patients with

multiple sclerosis and bladder dysfunction | Oxybutynin,

tolterodine | Oxybutynin (5-10

mg/day), Tolterodine (4 mg/day) | 12 weeks | Symbol Digit

Modalities Test (SDMT), BiCAMS battery | (7) |

| Sakakibara et

al, 2013 | Prospective

cohort | 62 | Patients with

neurologic overactive bladder due to various conditions (for

example, Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, white matter lesions) | Imidafenacin | 0.2 mg/day (0.1 mg

twice daily) | 3 months | Mini-Mental State

Examination (MMSE), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), ADAS-cog | (4) |

Primary outcome: Cognitive

decline

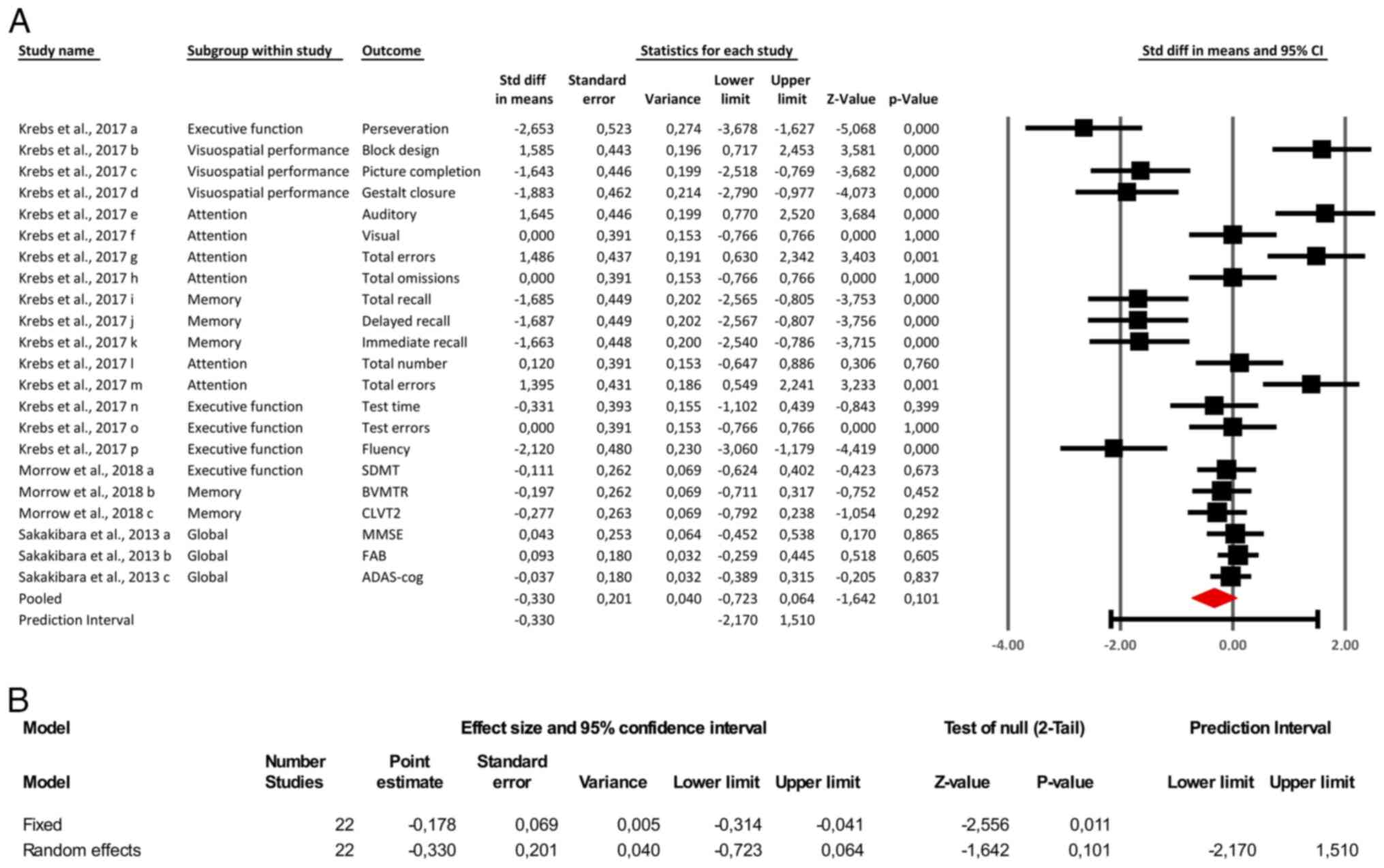

The meta-analysis of 22 comparisons yielded a pooled

SMD of -0.33 (95% CI: -0.72 to 0.06; Fig. 2A) under a random-effects model,

indicating a trend toward negative cognitive effects of

anticholinergic medications that did not reach statistical

significance (P=0.10). By contrast, a complementary fixed-effects

analysis produced a statistically significant SM -0.178 (95% CI:

-0.314 to -0.041; P=0.011), suggesting a small but significant

overall effect. However, given the substantial between-study

heterogeneity (Q=162.25, df=21, P<0.001; τ²=0.738; τ=0.859;

Fig. 2B), the random-effects model

was prioritized. This model accounts for both within- and

between-study variance and provides a more conservative and

generalizable estimate, particularly appropriate when true effect

sizes are expected to vary due to differences in patient

populations, anticholinergic agents and cognitive assessment tools.

Notably, domain-specific impairments were more evident in memory

and executive function, while global cognitive measures showed

minimal or non-significant effects. To explore potential sources of

heterogeneity, subgroup and sensitivity analyses were subsequently

performed.

Sensitivity analysis

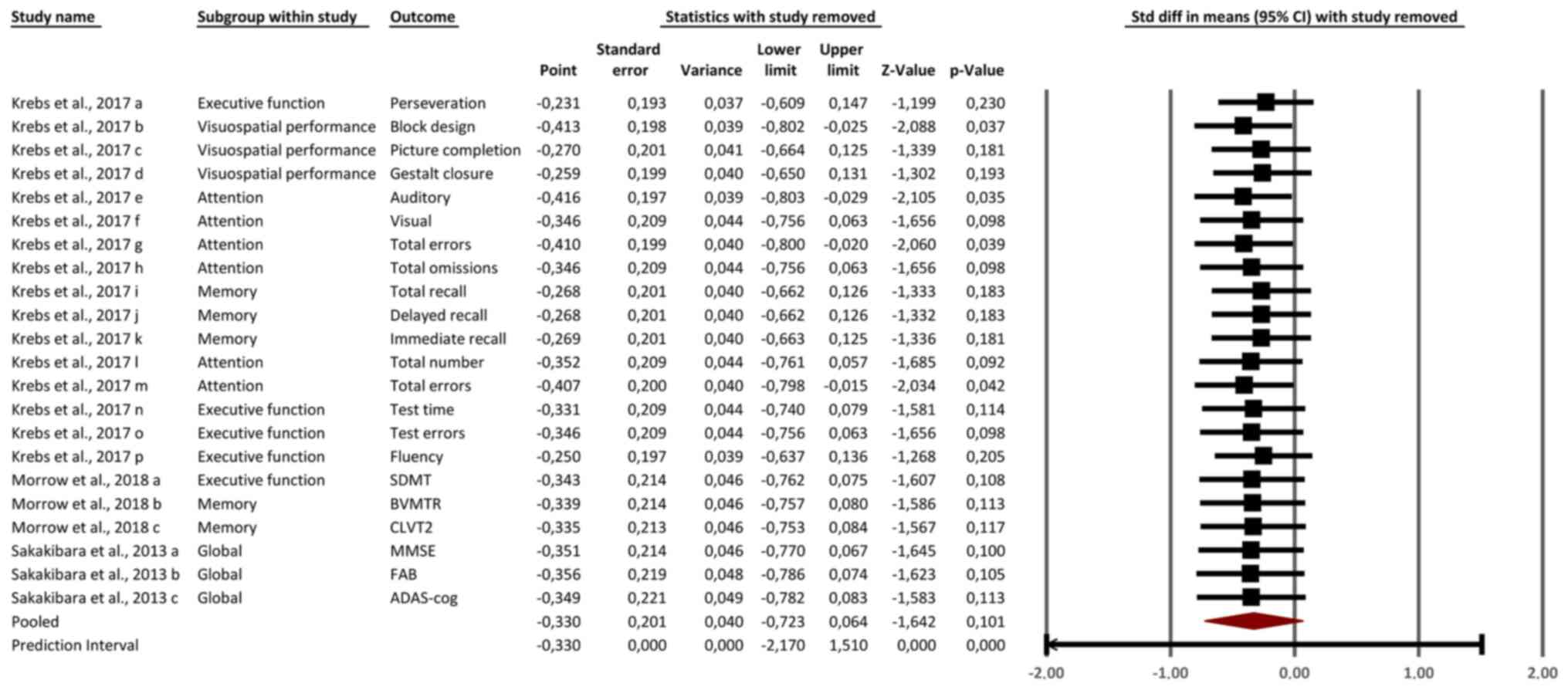

The sensitivity analysis, as shown in Fig. 3, demonstrated that the overall

effect size remained stable, with the pooled SMD ranging between

-0.25 and -0.41 after sequential removal of individual studies. No

single study had an outsized influence on the overall results,

confirming the robustness of the meta-analysis. Minor variations in

effect size were observed when removing studies assessing attention

outcomes, such as total errors and omissions from Krebs et

al (14), but these changes did

not significantly alter the overall conclusions. Similarly, the

removal of global cognitive outcomes [(for example, MMSE, FAB and

ADAS-cog in Sakakibara et al (4)] had minimal impact on the pooled

estimates, reflecting the limited influence of non-significant

global measures on the overall effect. The stability of the results

across sensitivity analyses underscores the consistent negative

impact of anticholinergic medications on cognitive outcomes,

particularly in memory, attention and executive function.

Secondary outcomes: Subgroup analysis

results

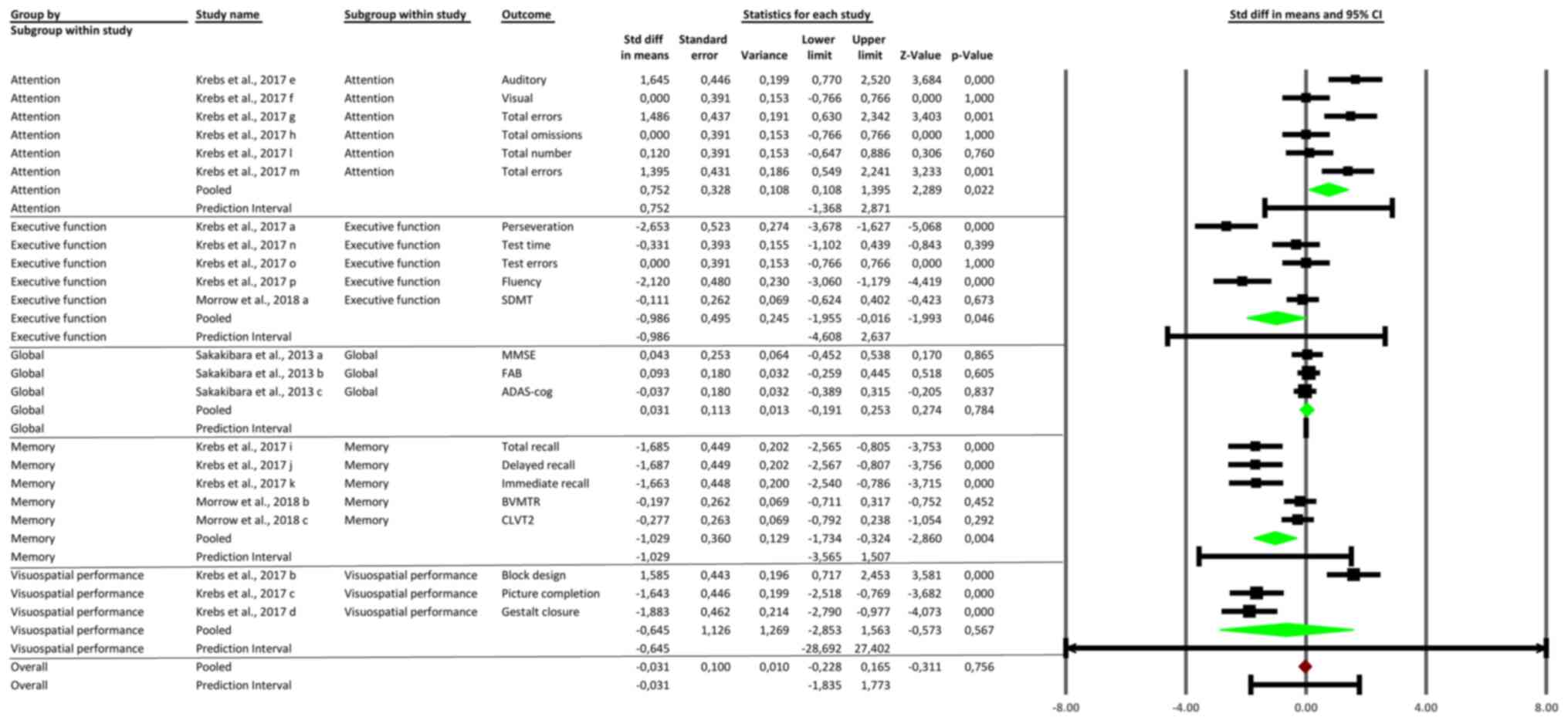

The subgroup analysis revealed significant

variability in the cognitive effects of anticholinergic medications

across different domains. Attention outcomes showed a significant

pooled (SMD) of 0.752 (95% CI: 0.108 to 1.395, P=0.022), indicating

impaired attentional processes. Executive function outcomes

demonstrated moderate impairment with a pooled SMD of -0.948 (95%

CI: -1.755 to -0.141, P=0.046). Memory outcomes also indicated

significant negative effects, with a pooled SMD of -0.645 (95% CI:

-1.269 to -0.022, P=0.043), affecting both short-term and long-term

memory. Global cognitive function showed no significant impact,

with a pooled SMD of -0.031 (95% CI: -0.311 to 0.249, P=0.837).

Visuospatial performance had a pooled SMD of -0.645 (95% CI: -1.563

to 0.273, P=0.165), suggesting a trend toward impairment that did

not reach statistical significance. These findings highlight the

greatest cognitive impairments in attention, executive function,

and memory, while global and visuospatial domains were less

impacted (Fig. 4).

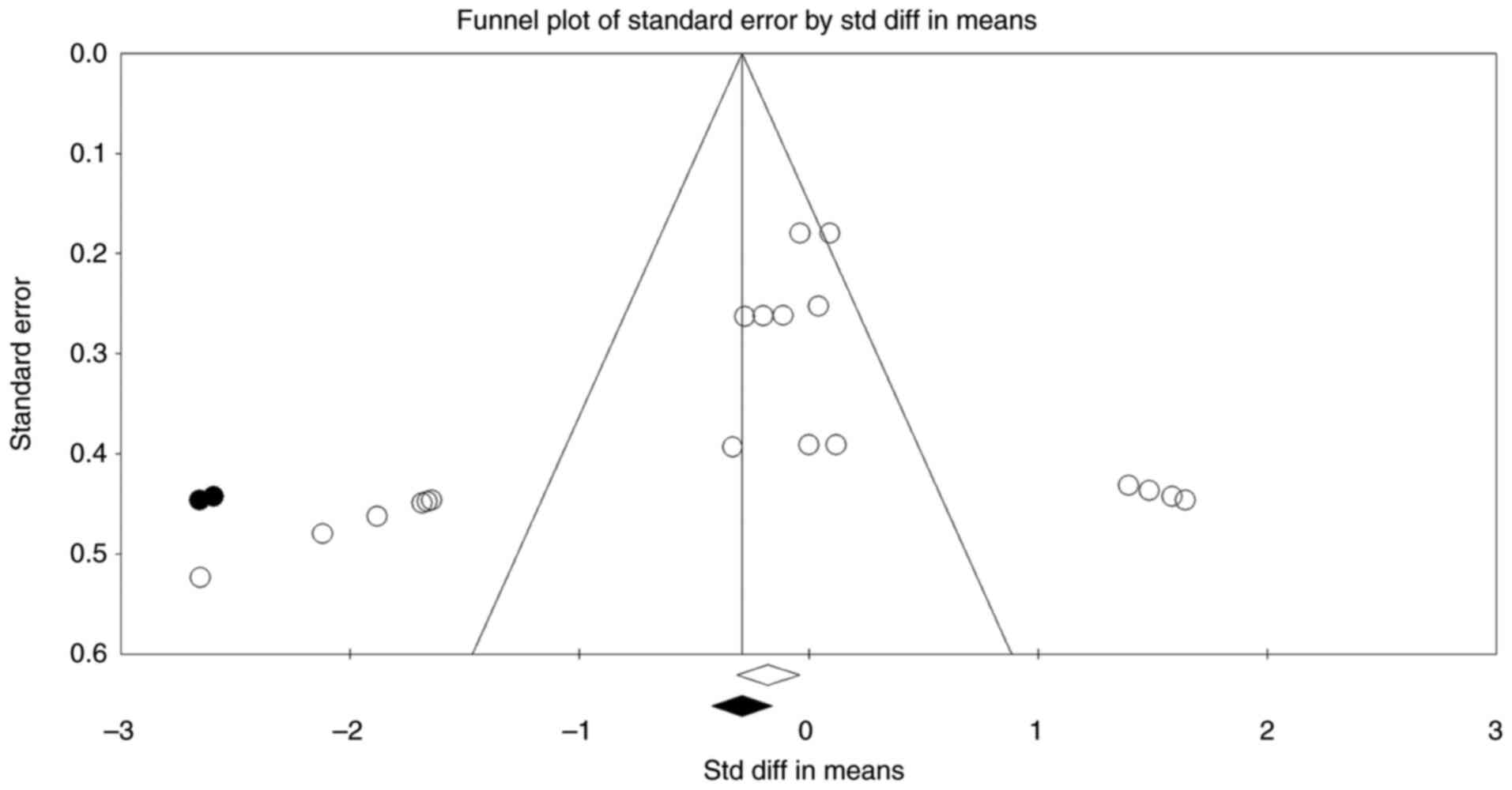

Publication bias

The funnel plot in Fig.

5 illustrates the distribution of studies based on their effect

sizes and standard errors, providing a visual assessment of

publication bias. The plot shows slight asymmetry, with a

concentration of studies on the left side (negative effect sizes),

suggesting a possible overrepresentation of studies reporting

negative cognitive effects. Begg's rank correlation test was

statistically significant (P=0.009), while Egger's regression test

was not (P=0.12). This discrepancy is not uncommon in meta-analyses

with a small number of studies. Empirical evidence indicates that

Begg's test may be more sensitive but less specific in small

samples, whereas Egger's test is more conservative and better

controls type I error under conditions of heterogeneity and

continuous outcomes. Importantly, the trim-and-fill method

estimated only two potentially missing studies, with negligible

impact on the pooled SMD, indicating that the overall effect size

remained stable after adjustment. Based on the mild funnel plot

asymmetry, the modest number of imputed studies, and the limited

change in effect size, we conclude that any potential publication

bias is unlikely to meaningfully influence the meta-analysis

results.

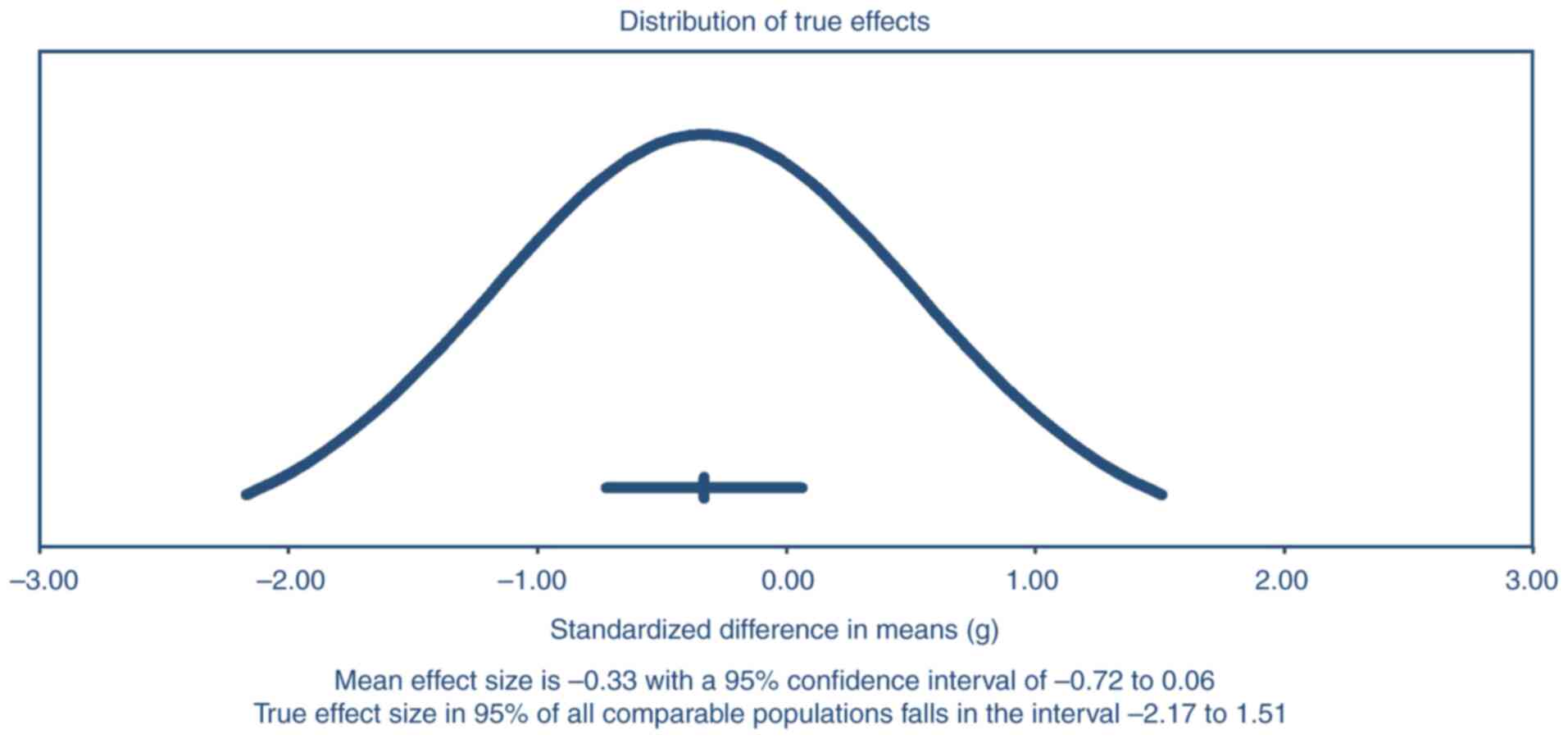

Heterogeneity

The precision interval analysis shown in Fig. 6 highlights the uncertainty

surrounding the pooled effect size of anticholinergic medications

on cognitive outcomes. The mean effect size was -0.33, with a 95%

CI ranging from -0.72 to 0.06, indicating that the overall effect

approaches but does not achieve statistical significance. The

precision interval, which extends from -2.17 to 1.51, demonstrates

substantial uncertainty due to between-study variability. This wide

precision interval suggests that while there is evidence of a

negative cognitive impact, the true effect size may vary

considerably across different populations and study contexts. This

further emphasizes the need for additional targeted studies to

reduce uncertainty and improve estimation of the true effect of

anticholinergics on cognitive function.

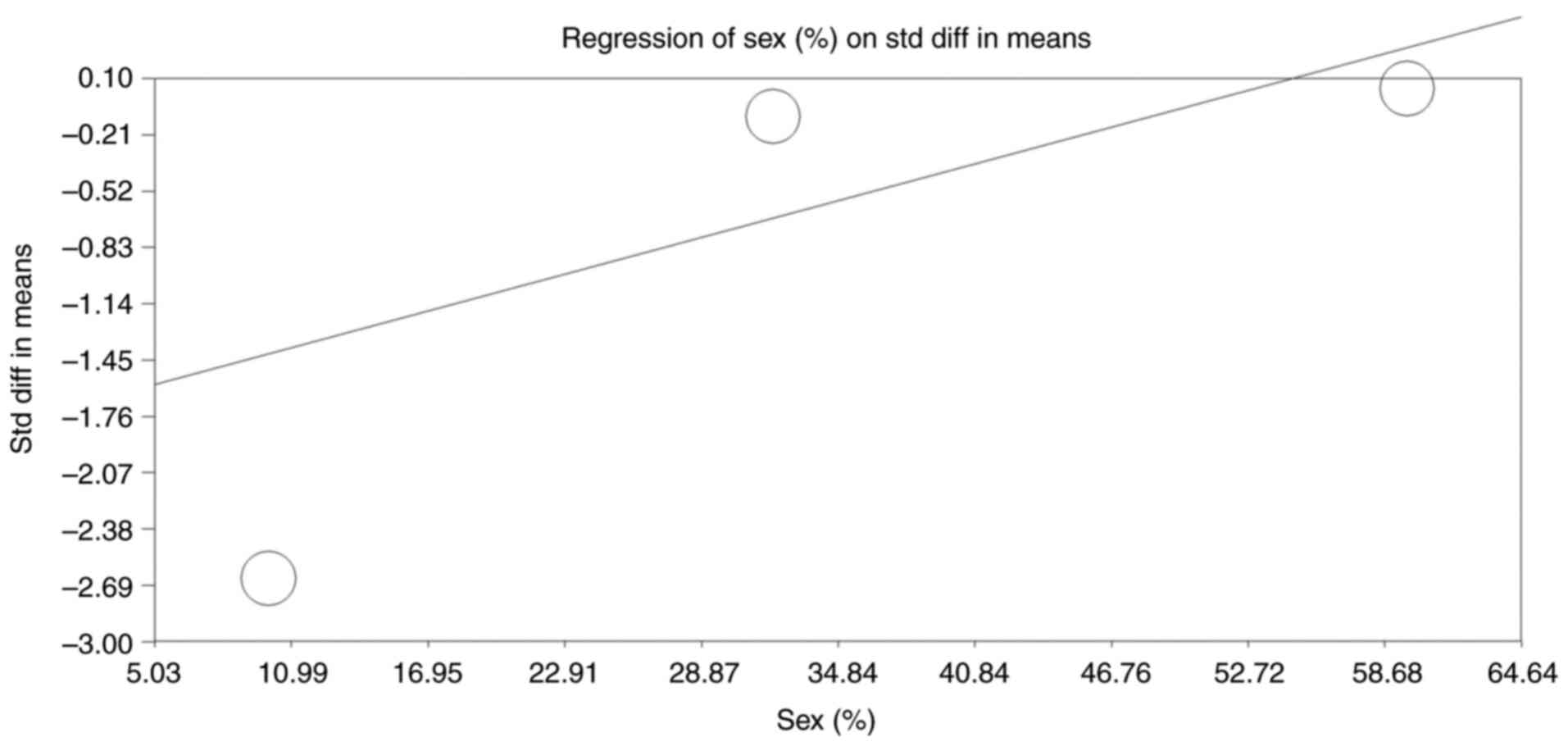

Moderator analysis

The moderator analysis evaluated the relationship

between the proportion of female participants in the included

studies and the observed SMD in cognitive outcomes, as shown in the

regression plot (Fig. 7). The

regression model yielded a positive slope of 0.033 (95% CI: 0.014

to 0.053, P<0.001), indicating a significant association between

sex distribution and the magnitude of cognitive decline. As the

proportion of female participants increased, the observed cognitive

impact of anticholinergic medications diminished, suggesting that

females may be less susceptible to adverse cognitive effects

compared with males. The intercept of -1.753 (P<0.001) reflects

the baseline SMD when the male proportion is minimal. The

significant Q-value (P<0.001) supports the robustness of this

association, with a tau-squared value of 1.096 reflecting the

variance explained by sex as a moderator. This analysis highlights

the importance of considering sex as a key factor in understanding

differential cognitive responses to anticholinergic

medications.

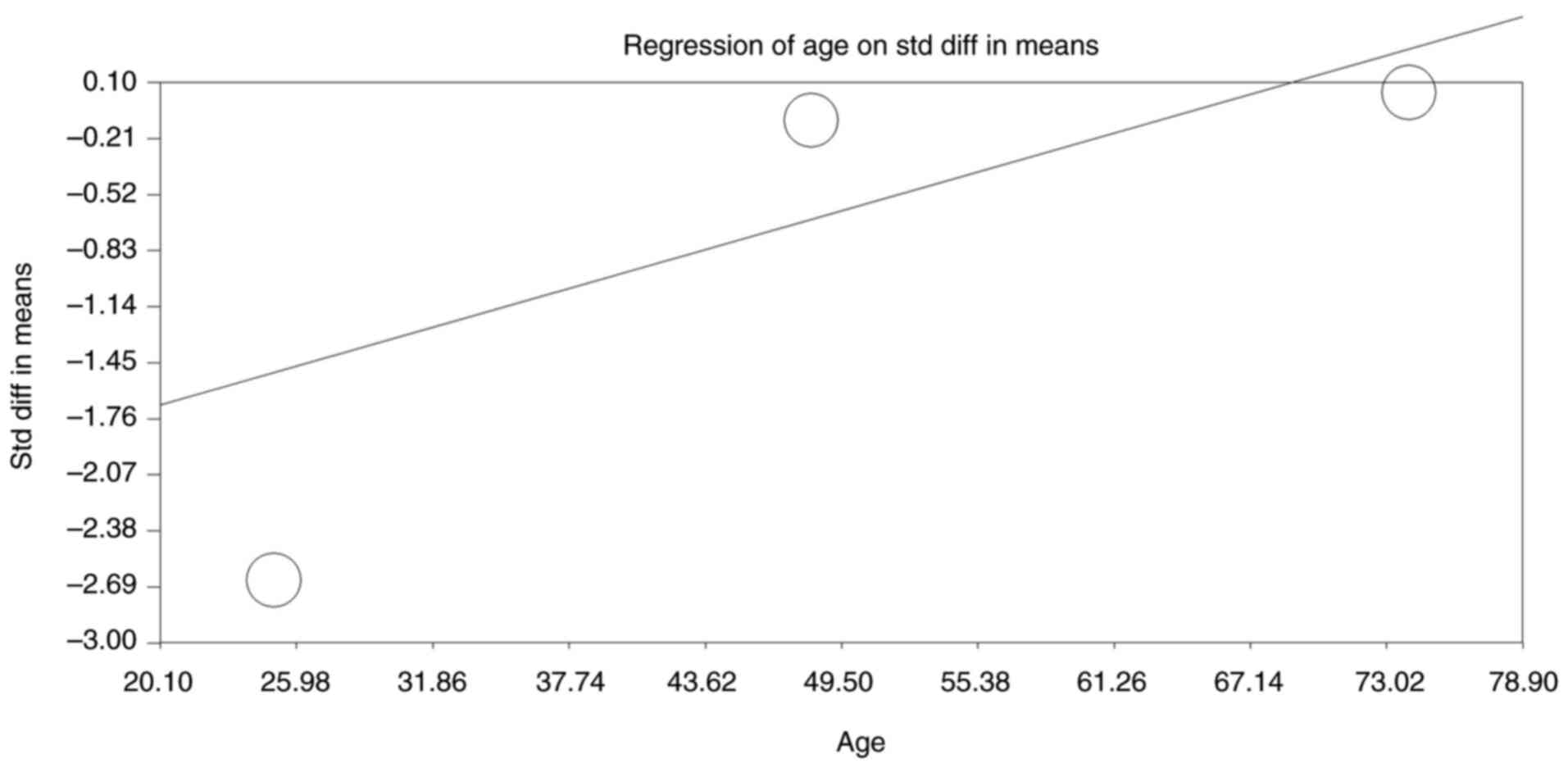

The moderator analysis also assessed the

relationship between the participants' mean age in the studies and

the observed SMD in cognitive outcomes (Fig. 8). The regression analysis yielded a

significant positive slope of 0.036 (95% CI: 0.01623 to 0.05669,

P<0.001), indicating that as the mean age of participants

increased, the magnitude of cognitive decline associated with

anticholinergic use was reduced. The intercept value of -2.414

(P<0.001) reflects the baseline SMD at a younger mean age. The

significant Q-value (P<0.001) suggests that age significantly

moderated the cognitive impact of anticholinergics, with younger

participants experiencing more severe cognitive decline. The

tau-squared value of 0.961 indicates considerable between-study

variability explained by differences in mean age. This analysis

highlights age as a critical moderator, suggesting that younger

individuals may be more susceptible to anticholinergic-induced

cognitive impairments compared with older adults.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed

using the NOS, with scores ranging from 6 to 8 out of a maximum of

9. Morrow et al (7) received

the highest score (8/9), reflecting its randomized design,

comprehensive outcome assessment, and high comparability between

groups. Krebs et al (14)

scored 7/9, with points deducted for limited blinding and potential

confounders. Sakakibara et al (4) received a score of 6/9 due to potential

selection bias, limited blinding, and reduced comparability across

groups. Overall, the studies demonstrated moderate to high

methodological quality, ensuring reliable data for meta-analysis

(Table II).

| Table IIQuality assessment using the NOS. |

Table II

Quality assessment using the NOS.

| First author/s,

year | Selection (4) | Comparability

(2) | Outcome (3) | Total score | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Krebs et al,

2017 | ++++ | +- | ++- | 7/9 | (14) |

| Morrow et

al, 2018 | ++++ | ++ | +++ | 8/9 | (7) |

| Sakakibara et

al, 2013 | +++ - | -- | ++- | 6/9 | (4) |

Discussion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis

investigated the cognitive effects of anticholinergic medications

in individuals with NLUTD. The primary findings suggest a trend

toward negative cognitive impact-particularly in the domains of

memory, executive function and attention-though the overall effect

using a random-effects model did not reach statistical

significance. This discussion contextualizes these findings within

the broader literature, highlights potential explanations for the

heterogeneous outcomes, and proposes clinical implications and

future directions.

A key observation from the pooled results is the

modest, albeit statistically non-significant, negative overall

impact of anticholinergics on cognitive performance (SMD=-0.33; 95%

CI: -0.72 to 0.06; P=0.10). Although the fixed-effects model

produced a statistically significant SMD of -0.178 (P=0.011), the

random-effects model was prioritized, which yielded a

non-significant SMD of -0.33 (P=0.10). This choice was made because

the random-effects model incorporates between-study heterogeneity,

combining both within-study and between-study variance into the

pooled estimate-an approach that is most appropriate given the

observed high heterogeneity (Q=162.25, P<0.001; τ²=0.738)

(15). By contrast, the

fixed-effects model assumes all studies estimate the same true

effect. While it offers greater statistical power, it may

underestimate uncertainty when substantial between-study

variability exists (15).

Therefore, to provide a more conservative and realistic estimate

that reflects clinical diversity, the random-effects model was

deemed more appropriate.

Our findings align with existing evidence indicating

that anticholinergic medications can impair central cholinergic

pathways involved in cognition (1,2). In

particular, the cholinergic deficit hypothesis has been

well-documented in several neurocognitive disorders, including

Alzheimer's disease, emphasizing the importance of central

acetylcholine in learning, memory, and attention (16). Given that anticholinergics block

muscarinic receptors, a reduction in central cholinergic signaling

can manifest as deficits in processing speed, executive

functioning, and memory formation (17). While the lack of significance in the

present meta-analysis calls for caution in interpreting the data,

the consistency with theoretical mechanisms and other clinical

trials warrants continued scrutiny of anticholinergic-induced

cognitive decline.

A striking feature of the present meta-analysis is

the substantial heterogeneity (Q-value of 162.25, P<0.001;

τ2=0.738). The wide prediction interval (-2.17 to 1.51)

highlights significant between-study variability and reflects

instability in the overall effect. This contrasts with the narrower

CI, which estimates the precision of the mean effect (18). The breadth of the interval indicates

that findings should be interpreted cautiously (19), and highlights the need for future

large-scale and standardized trials to reduce uncertainty and

improve estimation of the true cognitive impact of

anticholinergics. Several factors might underlie this variability

in effect sizes. First, differences in sample characteristics, such

as underlying etiologies (for example, MS, SCI and OAB) and disease

progression, could contribute to varying baseline vulnerability to

cognitive dysfunction. Individuals with MS or SCI often exhibit

pre-existing cognitive deficits due to demyelination or traumatic

central nervous system injury (20,21).

The incremental burden of anticholinergic medications may,

therefore, differ depending on neurological reserve and the

severity of baseline impairments. Second, the use of various

anticholinergic agents (for example, oxybutynin, tolterodine,

solifenacin and imidafenacin) with diverse pharmacokinetic profiles

likely influenced cognitive outcomes. Older-generation medications

such as oxybutynin and tolterodine are known to cross the

blood-brain barrier more readily, thereby increasing the likelihood

of central side effects (22).

Conversely, newer or more selective agents (for example,

solifenacin and imidafenacin) may exert a lesser central

anticholinergic burden, resulting in lower cognitive risk (22). It is thus plausible that differences

in agent selectivity, dosing schedules, and treatment durations

contributed to the heterogeneity detected in this review. Third,

variations in outcome measures across the included studies can also

drive heterogeneity. Some studies relied on global cognitive

measures (for example, MMSE, ADAS-cog, FAB), which may lack

sensitivity to subtle cognitive changes. More comprehensive or

domain-specific instruments (for example, the SDMT or detailed

memory tasks) might detect more nuanced impairments. This

meta-analysis found stronger associations in targeted domains such

as memory, executive function, and attention, suggesting that

future research should prioritize sensitive, domain-specific

assessments to capture the full extent of cognitive changes induced

by anticholinergics.

Despite the non-significant pooled effect, the

subgroup analyses offered valuable insights. Attention, executive

function, and memory domains emerged as particularly vulnerable to

the effects of anticholinergics. These domains are heavily reliant

on adequate cholinergic transmission (23). Studies utilizing tests such as the

Stroop Test, the SDMT, and word-list learning tasks have repeatedly

demonstrated that blocking cholinergic receptors impairs selective

attention, mental flexibility, and the encoding of new memories

(24,25). In NLUTD populations where patients

may already contend with the cognitive burden from neurological

disorders, even minor reductions in performance can have profound

practical consequences, affecting daily living activities,

adherence to rehabilitation protocols, and overall quality of

life.

The moderator analyses underscore the complexity of

factors influencing cognitive vulnerability. Intriguingly, a higher

proportion of females in a study's cohort correlated with smaller

negative cognitive effects (P<0.001). Although evidence is

mixed, some literature suggests that sex-related hormonal and

genetic factors could modulate pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic

responses to medications (26).

Similarly, older age was associated with reduced severity of

cognitive decline, suggesting that younger individuals with NLUTD

may be more susceptible (P<0.001). While this finding appears

counterintuitive-given that older adults are generally considered

at elevated risk of anticholinergic-induced delirium or cognitive

impairment-certain explanations may apply. Younger cohorts might

exhibit higher baseline functioning, making any decrement from

baseline more pronounced. Additionally, older adults with

significant frailty or comorbidities might be preferentially

prescribed lower doses or more selective anticholinergics, thereby

moderating their cognitive risks.

Clinical implications from these findings revolve

around two major points. First, prescribers must balance

therapeutic goals in managing NLUTD with the potential for adverse

cognitive events. Urinary incontinence, frequency, and urgency

negatively affect patient well-being, but the costs of therapy

include potential detrimental effects on higher-order brain

function. In populations with existing neurologic compromise,

vigilance is paramount. Clinicians could consider minimizing

exposure to highly lipophilic or non-selective anticholinergics and

employing the lowest efficacious dose. Second, alternative

therapies such as β3-adrenergic agonists (for example, mirabegron)

have shown promise in providing symptomatic relief with less

central cholinergic interference (27). Transitioning or combining these

agents with other interventions-for example, pelvic floor

rehabilitation and neuromodulation therapies-may be a viable

strategy for individuals with significant cognitive vulnerability

(28).

While the publication bias analysis and

trim-and-fill adjustments indicate only a minor impact of potential

unpublished negative or null studies, the slight asymmetry in the

funnel plot underscores the need for continued, transparent

reporting of cognitive outcomes in NLUTD populations. Researchers

must publish all relevant data, including neutral or equivocal

results, to ensure that meta-analytic estimates accurately reflect

true effects. Although Begg's test indicated possible small-study

effects, the non-significant Egger's result and minimal change

after applying trim-and-fill (only two studies imputed, with little

effect on the pooled SMD) suggest that publication bias likely does

not materially alter our overall conclusions (29).

The present meta-analytic systematic review has

several limitations. First, the overall number of included studies

was small (N=3), limiting the power to detect modest but clinically

relevant cognitive changes. Moreover, the short treatment durations

and heterogeneous follow-up periods (ranging from a few weeks to

months) may not fully capture the long-term cognitive trajectory of

patients receiving anticholinergics. Second, the included studies

employed various cognitive tests, ranging from global measures (for

example, MMSE) to domain-specific tools, making direct comparisons

challenging and introducing potential measurement bias. Third,

while the meta-analysis attempted to evaluate publication bias, the

limited number of studies constrains the reliability of these

statistical tests. Fourth, confounding variables-such as

concomitant medication use, overall anticholinergic burden from

multiple sources, and comorbid psychiatric or neurological

conditions-were not consistently reported or controlled for across

studies. Fifth, most studies had relatively small sample sizes and

did not stratify participants based on the severity of NLUTD or

baseline cognitive function, precluding more nuanced subgroup

analyses. Sixth, although the subgroup analyses revealed

statistically significant SMDs for attention (0.752), executive

function (-0.948), and memory (-0.645), it was emphasized that

these results are preliminary. With only three studies and small

subgroup samples, estimates may be unstable, and type I error is

possible (30). These findings

should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than

confirmatory, aligned with broader trends observed in

anticholinergic research that highlight domain-specific

vulnerabilities but await validation in larger, adequately powered

studies. Seventh, the moderator findings-suggesting less cognitive

impact in studies with more female participants and greater

declines in younger cohorts-should be interpreted cautiously. With

only three contributing studies, the estimates are statistically

underpowered and potentially confounded, in line with

methodological cautions against overinterpreting such results. As

such, these results remain hypothesis-generating and should be

confirmed in larger, more robustly powered analyses. Eights, the

subgroup and moderator analyses were performed post hoc and not

pre-specified in a formal protocol. As such, these findings should

be interpreted with caution, recognizing their exploratory nature.

Finally, the observed high heterogeneity (Q=162.25, τ²=0.738)

likely reflects not only clinical diversity but also methodological

variability-notably, differences in cognitive testing instruments

and anticholinergic pharmacodynamics. For instance, more sensitive

domain-specific tools (for example, SDMT, FAB) may detect subtle

deficits missed by global measures such as MMSE. Additionally,

drug-specific factors-such as muscarinic receptor subtype

selectivity and central nervous system penetration-might explain

variability, as older agents (for example, oxybutynin) pose higher

cognitive risks than newer, more selective agents (for example,

imidafenacin) (31,32). Future meta-regression or individual

participant data analyses are needed to more precisely quantify

these structural sources of heterogeneity.

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis suggests

that anticholinergic medications may exert a negative, though

variably expressed, impact on cognition in patients with NLUTD,

particularly in memory, executive function, and attention. While

the pooled effect did not reach statistical significance using a

random-effects model, considerable heterogeneity points to the

influence of patient characteristics, drug choice, and

methodological differences in outcome assessment. These findings

underscore the need for carefully weighing therapeutic benefits

against potential cognitive risks, especially in populations

already burdened by neurological compromise. Future large-scale,

longitudinal studies with standardized cognitive measures, detailed

patient stratification, and attention to confounding factors are

essential to refine our understanding of anticholinergic-related

cognitive changes and guide safer prescribing practices.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

HZ and YW conceptualized the study, designed the

search strategy, and drafted the initial manuscript. HZ performed

data extraction, contributed to data analysis, and assisted with

manuscript revisions. HZ conducted the quality assessment,

contributed to statistical analysis and finalized the manuscript.

HZ and YW confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. Both

authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Trbovich M, Romo T, Polk M, Koek W, Kelly

C, Stowe S, Kraus S and Kellogg D: The treatment of neurogenic

lower urinary tract dysfunction in persons with spinal cord injury:

An open label, pilot study of anticholinergic agent vs mirabegron

to evaluate cognitive impact and efficacy. Spinal Cord Ser Cases.

7(50)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Wang YC, Chen YL, Huang CC, Ho CH, Huang

YT, Wu MP, Ou MJ, Yang CH and Chen PJ: Cumulative use of

therapeutic bladder anticholinergics and the risk of dementia in

patients with lower urinary tract symptoms: A nationwide 12-year

cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 19(380)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Cameron AP: Medical management of

neurogenic bladder with oral therapy. Transl Androl Urol. 5:51–62.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Sakakibara R, Tateno F, Yano M, Takahashi

O, Sugiyama M, Ogata T, Haruta H, Kishi M, Tsuyusaki Y, Yamamoto T,

et al: Imidafenacin on bladder and cognitive function in neurologic

OAB patients. Clin Auton Res. 23:189–195. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Richardson K, Fox C, Maidment I, Steel N,

Loke YK, Arthur A, Myint PK, Grossi CM, Mattishent K, Bennett K, et

al: Anticholinergic drugs and risk of dementia: Case-control study.

BMJ. 361(k1315)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Coupland CAC, Hill T, Dening T, Morriss R,

Moore M and Hippisley-Cox J: Anticholinergic drug exposure and the

risk of dementia: A nested case-control study. JAMA Intern Med.

179:1084–1093. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Morrow SA, Rosehart H, Sener A and Welk B:

Anti-cholinergic medications for bladder dysfunction worsen

cognition in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci.

385:39–44. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Harvey PD: Domains of cognition and their

assessment. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 21:227–237. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Oleksy P, Zieliński K, Buczkowski B,

Sikora D, Góralczyk E, Zając A, Mąka M, Papież Ł and Kamiński J:

Cognitive function tests: Application of MMSE and MoCA in various

clinical settings-a brief overview. Qual Sport. 34(56285)2024.

|

|

10

|

Benedict RH, DeLuca J, Phillips G, LaRocca

N, Hudson LD and Rudick R: Multiple Sclerosis Outcome Assessments

Consortium. Validity of the symbol digit modalities test as a

cognition performance outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult

Scler. 23:721–733. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

von Hippel PT: The heterogeneity statistic

I(2) can be biased in small meta-analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol.

15(35)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Borenstein M: In a meta-analysis, the

I-squared statistic does not tell us how much the effect size

varies. J Clin Epidemiol. 152:281–284. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Krebs J, Scheel-Sailer A, Oertli R and

Pannek J: The effects of antimuscarinic treatment on the cognition

of spinal cord injured individuals with neurogenic lower urinary

tract dysfunction: A prospective controlled before-and-after study.

Spinal Cord. 56:22–27. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Dettori JR, Norvell DC and Chapman JR:

Fixed-effect vs random-effects models for meta-analysis: 3 Points

to consider. Global Spine J. 12:1624–1626. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Majdi A, Sadigh-Eteghad S, Rahigh Aghsan

S, Farajdokht F, Vatandoust SM, Namvaran A and Mahmoudi J:

Amyloid-β, tau, and the cholinergic system in Alzheimer's disease:

Seeking direction in a tangle of clues. Rev Neurosci. 31:391–413.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Naseri A, Sadigh-Eteghad S,

Seyedi-Sahebari S, Hosseini MS, Hajebrahimi S and Salehi-Pourmehr

H: Cognitive effects of individual anticholinergic drugs: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Dement Neuropsychol.

17(e20220053)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Liu XS: Sample size and the precision of

the confidence interval in meta-analyses. Ther Innov Regul Sci.

49:593–598. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Spineli LM and Pandis N: Prediction

interval in random-effects meta-analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop. 157:586–588. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Talebi M, Majdi A, Kamari F and

Sadigh-Eteghad S: The cambridge neuropsychological test automated

battery (CANTAB) versus the minimal assessment of cognitive

function in multiple sclerosis (MACFIMS) for the assessment of

cognitive function in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler

Relat Disord. 43(102172)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Motavalli A, Majdi A, Hosseini L, Talebi

M, Mahmoudi J, Hosseini SH and Sadigh-Eteghad S: Pharmacotherapy in

multiple sclerosis-induced cognitive impairment: A systematic

review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord.

46(102478)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Callegari E, Malhotra B, Bungay PJ,

Webster R, Fenner KS, Kempshall S, LaPerle JL, Michel MC and Kay

GG: A comprehensive non-clinical evaluation of the CNS penetration

potential of antimuscarinic agents for the treatment of overactive

bladder. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 72:235–246. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Han L, Agostini JV and Allore HG:

Cumulative anticholinergic exposure is associated with poor memory

and executive function in older men. J Am Geriatr Soc.

56:2203–2310. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Sittironnarit G, Ames D, Bush AI, Faux N,

Flicker L, Foster J, Hilmer S, Lautenschlager NT, Maruff P, Masters

CL, et al: Effects of anticholinergic drugs on cognitive function

in older Australians: Results from the AIBL study. Dement Geriatr

Cogn Disord. 31:173–178. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Georgiou R, Lamnisos D and Giannakou K:

Anticholinergic burden and cognitive performance in patients with

schizophrenia: A systematic literature review. Front Psychiatry.

12(779607)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Trenaman SC, Bowles SK, Andrew MK and

Goralski K: The role of sex, age and genetic polymorphisms of CYP

enzymes on the pharmacokinetics of anticholinergic drugs. Pharmacol

Res Perspect. 9(e00775)2021.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Sartori LGF, Nunes BM, Farah D, Oliveira

LM, Novoa CCT, Sartori MGF and Fonseca MCM: Mirabegron and

anticholinergics in the treatment of overactive bladder syndrome: A

meta-analysis. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 45:337–346. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Abrams P, Kelleher C, Staskin D, Kay R,

Martan A, Mincik I, Newgreen D, Ridder A, Paireddy A and van Maanen

R: Combination treatment with mirabegron and solifenacin in

patients with overactive bladder: Exploratory responder analyses of

efficacy and evaluation of patient-reported outcomes from a

randomized, double-blind, factorial, dose-ranging, phase II study

(SYMPHONY). World J Urol. 35:827–838. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

van Enst WA, Ochodo E, Scholten RJPM,

Hooft L and Leeflang MM: Investigation of publication bias in

meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy: A meta-epidemiological

study. BMC Med Res Methodol. 14(70)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Munkholm K and Paludan-Müller AS: Caution

is advised when interpreting subgroup analyses.

Neuropsychopharmacology. 46(1551)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Reinold J, Schäfer W, Christianson L,

Barone-Adesi F, Riedel O and Pisa FE: Anticholinergic burden and

fractures: A protocol for a methodological systematic review and

meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 9(e030205)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Pieper NT, Grossi CM, Chan WY, Loke YK,

Savva GM, Haroulis C, Steel N, Fox C, Maidment ID, Arthur AJ, et

al: Anticholinergic drugs and incident dementia, mild cognitive

impairment and cognitive decline: A meta-analysis. Age Ageing.

49:939–947. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|