Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is a proliferative

vascular disease that occurs in areas of the retina where vascular

development is incomplete in preterm infants. It is characterized

by abnormal blood vessel proliferation, which can lead to retinal

detachment and blindness (1). A

meta-analysis involving 121,618 preterm infants reported that the

global incidence of ROP in preterm infants is 31.9%, with the

incidence of severe ROP at 7.5% (2). A cohort study (3) conducted in the United States from 2003

to 2019 involving 125,212 cases of ROP showed that the overall

incidence of ROP in premature infants increased from 4.4 to 8.1%;

the incidence in African-American infants rose from 5.8 to 11.6%

and that in infants from low-income families rose from 4.9 to 9.0%;

and the increase was the greatest in the southern region (3.7 to

8.3%). Therefore, there are certain differences in the incidence of

ROP in various regions and populations, and it is necessary to

develop risk prediction models for different groups. Clinically,

the diagnosis and severity assessment of ROP are based on the

International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity, 3rd

Edition (ICROP3), released in 2021. This classification

systematically defines the lesion location, progression extent and

risk level of ROP through indicators including lesion zones I-III,

disease stages 1-5 and plus disease (severe retinal vascular

dilation and tortuosity in the posterior pole), thereby providing a

foundation for clinical diagnosis (4).

Current research suggests that the pathogenesis of

ROP is characterized by a biphasic pattern of retinal vascular

development: An initial phase of reduced retinal vascular growth,

followed by excessive vessel proliferation into the vitreous body

(5). Vascular endothelial growth

factor (VEGF) serves a critical role in retinal neovascularization.

In recent years, therapeutic approaches have shifted from laser

therapy to anti-VEGF therapy (6).

The RAINBOW Extension study confirmed that ranibizumab, when

administered to preterm infants with ROP, significantly decreases

the risk of high myopia (7).

However, follow-up studies (8,9) have

indicated that infants receiving anti-VEGF therapy may have a

higher risk of adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes. Furthermore, in

remote areas, the lack of medical resources and equipment can lead

to worsening conditions in preterm infants, resulting in blindness

(10). Therefore, compared with

single biomarkers or imaging examinations, ROP prediction models

have value in integrating multi-dimensional clinical data to

achieve dynamic risk stratification. Particularly in resource-poor

regions, these models may compensate for the insufficiency of

fundus screening equipment, enabling the rapid identification of

high-risk preterm infants through basic indicators. To obtain more

practical evidence for ROP risk prediction, current research

(11) focuses on early disease risk

prediction, conducting large-scale clinical cohort studies, and

developing new artificial intelligence/machine learning algorithms

to enhance the accuracy and practicality of ROP risk prediction.

However, with the development of computer vision and deep learning

algorithms, despite the continuous emergence of various prediction

models and algorithms, challenges such as overfitting and

insufficient data diversity remain. There is significant

heterogeneity among studies (12,13) in

terms of sample size, predictors, model construction methods and

reported performance metrics, and there are relatively few

systematic reviews on the diagnostic performance of these models

(14,15).

Almutairi et al (10) performed a meta-analysis that focused

on the association between platelet count, thrombocytopenia and

severe ROP, and explored the potential mechanisms linking a single

biomarker to the disease through methods such as Bayesian model

averaging. However, this previous study was limited to the causal

exploration of a single risk factor, failing to involve the

systematic integration and methodological evaluation of existing

multifactorial ROP risk prediction models. It also did not assess

differences in applicability of various predictive tools in

clinical settings, and did not provide a comprehensive

understanding and basis for selecting ROP risk screening tools. The

present study aimed to overcome the limitations of single-factor

association studies by conducting a systematic review and

meta-analysis on risk prediction models for ROP in preterm infants.

It systematically organizes, synthesizes and evaluates the

methodological characteristics and application potential of

existing models, thereby providing a design framework for the

rational selection and optimization of ROP risk prediction models

in clinical practice.

Materials and methods

Study design

The present study adhered to the Transparent

Reporting of a Multivariable Prediction Model for Individual

Prognosis Or Diagnosis statement (16), and followed the critical appraisal

and data extraction checklist of Critical Appraisal and Data

Extraction for Systematic Reviews of Prediction Modelling Studies

(17). The study did not involve

human experiments or direct collection of clinical data, thus no

ethics committee approval was required. The key items of the

systematic review were as follows: People, preterm infants;

intervention model, development and publication of risk prediction

models for ROP in preterm infants; comparator, no competing model;

outcome, incidence of ROP in preterm infants (primary) and

performance metrics of the prediction model (secondary); timing,

from birth of preterm infants until ROP stabilizes or the relevant

observation period ends and setting, healthcare settings, including

neonatal intensive care units, pediatric wards and specialized

ophthalmic clinics in hospitals of various levels.

Search strategy

A comprehensive literature search was conducted

using the PubMed (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Cochrane Library

(cochranelibrary.com/), Web of Science

(https://www.webofscience.com/) and

Embase (https://www.embase.com/) databases to

identify studies associated with ROP in preterm infants. The core

search terms used across the four databases are as follows: PubMed:

‘Infant, Premature’ (MeSH), ‘Infant, Extremely Premature’ (MeSH),

‘Retinopathy of Prematurity’ (MeSH), ‘Retinal Diseases’ (MeSH),

‘Area Under Curve’ (MeSH); Web of Science: core topic terms

including ‘Infant, Premature’, ‘Infant, Extremely Premature’,

‘Retinopathy of Prematurity’, ‘Retinal Diseases’, ‘Area Under

Curve’, ‘AUC’; Embase: ‘prematurity’/exp, ‘retrolental

fibroplasia’/exp, ‘retina disease’/exp, ‘area under the curve’/exp;

Cochrane Library: ‘Infant, Premature’ (explode all trees), ‘Infant,

Extremely Premature’ (explode all trees), ‘Retinal Diseases’

(explode all trees), ‘Retinopathy of Prematurity’ (explode all

trees), ‘Area Under Curve’ (explode all trees). A detailed search

strategy is provided in Table SI,

Table SII, Table SIII and Table SIV. To minimize discrepancies from

database updates, searches were conducted from database inception

until April 18, 2025, with all data collection completed by this

date.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: i)

Cross-sectional, cohort, retrospective or prospective studies; ii)

Diagnosis of ROP according to ICROP3(4), based on the affected area (zone I, II

or III), disease stage (stage 1-5) and retinal vascular

abnormalities [pre-plus disease (mild retinal vascular dilation and

tortuosity confined to the posterior pole, not meeting the severity

threshold for plus disease) or plus disease (severe retinal

vascular dilation and tortuosity involving the posterior pole,

typically affecting at least two quadrants, as defined by ICROP3 to

indicate advanced disease severity)] to determine disease severity;

iii) studies focusing on the development, validation or evaluation

of ROP prediction models in preterm infants; iv) study subjects

including preterm infants with a birth weight of ≥500 g or

gestational age of <37 weeks; v) prediction model including ≥2

predictors; vi) models associated with the occurrence, screening or

risk prediction of ROP, including traditional statistical models

(such as logistic regression) and machine learning algorithms (such

as decision trees and neural networks); vii) study providing

statistical indicators related to the model, such as the area under

the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and viii) English

literature. The exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Systematic

reviews, meta-analyses or other types of review articles; ii)

studies that did not provide quantitative results for the

prediction model, or where key data were unavailable or there was a

substantial amount of missing data; iii) studies involving children

with severe congenital malformation, complex systemic disease or

other ocular disease; iv) studies lacking a control group or with

unclear control group definitions; v) unclear sample definitions or

a large number of non-preterm infants and vii) conference

abstracts, editorials or studies on radiomics.

Literature screening

The literature screening was conducted using the

EndNote reference management tool (version 21, endnote.com/). Two authors independently screened the

titles and abstracts of the studies, excluding those that did not

meet the inclusion criteria. Full texts of the remaining studies

were reviewed for further screening. In case of disagreements, a

third researcher (was consulted to resolve the discrepancies and

reach a consensus.

Data extraction

The following information was collected from the

included studies: First author, publication year, region, study

design, sample size, predictive variables, model type, validation

methods and model evaluation metrics. All data were independently

extracted by two researchers and cross-checked for accuracy.

Assessment of literature quality

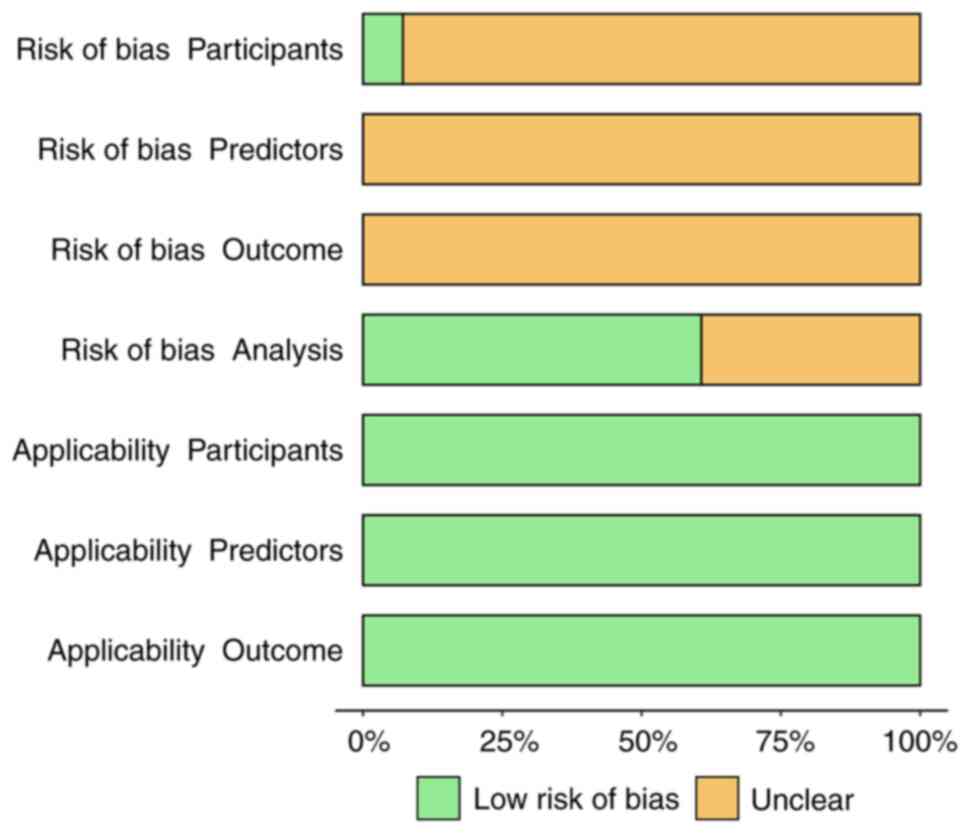

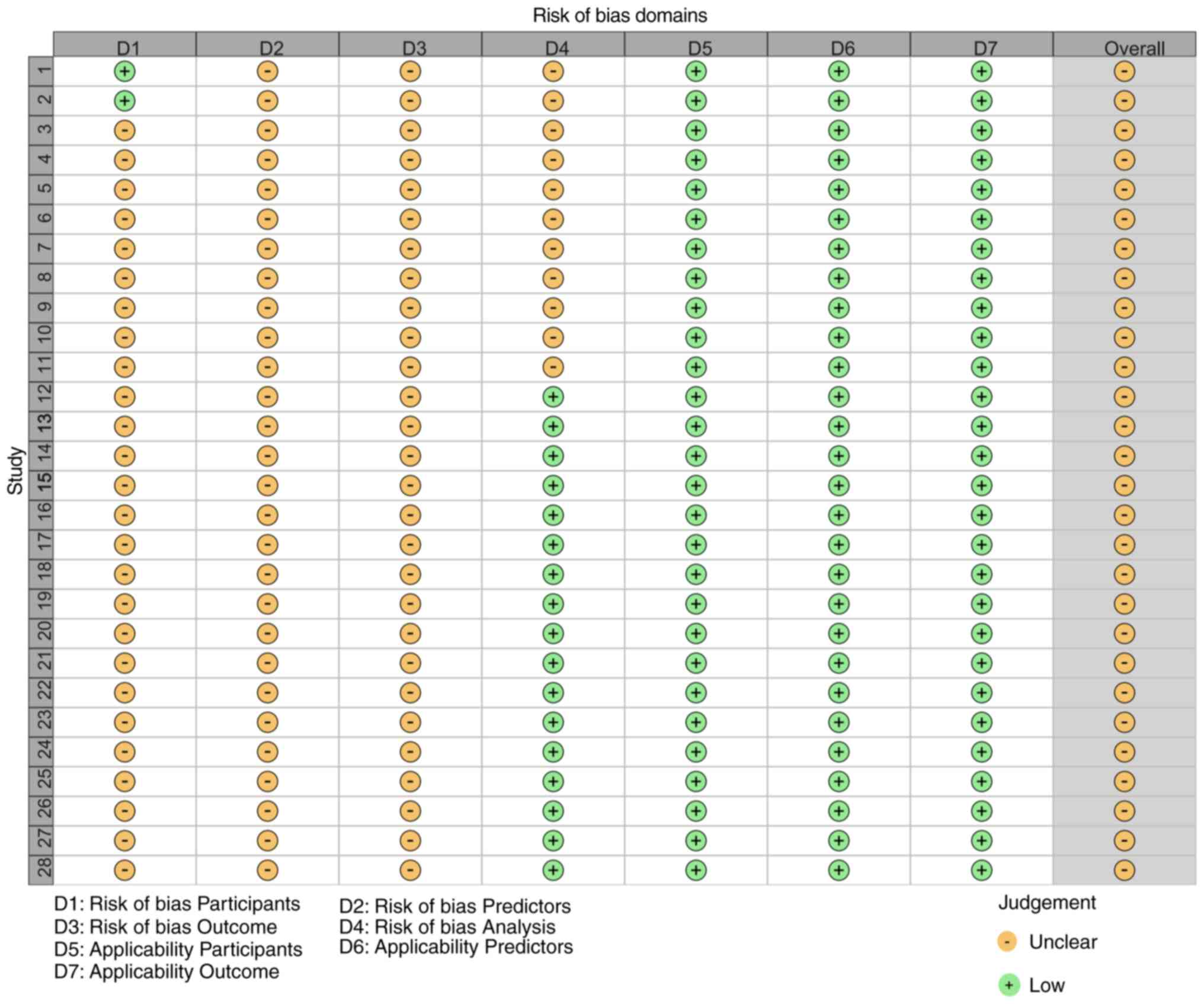

The risk of bias in the predictive models was

assessed using the Prediction Model Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool

(PROBAST) (18). A total of two

authors independently conducted the evaluation and cross-validated

the results; in case of discrepancies, a third author was consulted

for final assessment. PROBAST is designed for evaluating the risk

of bias and applicability of prediction model studies. It has been

used in systematic reviews (19,20)

and is suitable for the development, validation, and updating of

diagnostic or prognostic prediction models (21). The core framework of PROBAST

includes four primary domains and 20 items, aiming to

systematically assess potential biases introduced during the

research design, implementation and analysis phases to ensure the

reliability and clinical applicability of the prediction models.

The evaluation considers whether the outcome definitions align with

clinical needs. If the outcome definitions in the domain match

clinical concerns and provide valuable information for clinical

decision-making, the applicability is classified as ‘low risk’. If

the outcome definitions are disconnected from clinical needs and do

not effectively guide clinical practice, the applicability is

considered ‘high risk’. If the alignment of the outcome definitions

with clinical needs is unclear, the applicability is rated as

‘unclear’.

Subgroup analyses

To explore potential sources of heterogeneity in the

performance of ROP risk prediction models, predefined subgroup

analyses were planned and conducted based on model type and

geographic region.

For subgroup analysis by model type, studies were

stratified into two distinct subgroups according to the modeling

approaches employed. The first subgroup included studies utilizing

traditional statistical models, with logistic regression being the

primary method. The second subgroup comprised studies that adopted

machine learning models, which encompassed various techniques such

as neural networks, support vector machines, long short-term

memory, and deep learning models.

For subgroup analysis by geographic region, studies

were stratified into three regional subgroups based on the

geographical locations of the study populations. The first subgroup

included studies conducted in South America. The second subgroup

consisted of studies performed in Asia. The third subgroup combined

studies from North America and Europe, as these regions share

similarities in healthcare systems and population characteristics,

justifying their integration for comparative analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version

4.4.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2024; cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/old/4.4.2/),

utilizing the ‘meta (https://cran.r-project.org/package=meta)’ and ‘metafor

(https://cran.r-project.org/package=metafor)’ packages

to perform data pooling, heterogeneity testing, subgroup and

sensitivity analyses and publication bias assessment. The AUC and

its 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were extracted from studies as

the primary measure of predictive performance. Cochran's Q test and

I² statistic were used to assess heterogeneity between studies. A

random-effects model was used to pool the data, addressing the

heterogeneity across studies. To assess potential publication bias,

funnel plots were constructed. According to the Cochrane Handbook

(22), when the number of included

studies is ≥10, publication bias risk assessment should not rely on

Egger's or Begg's test. Instead, Peters' test (23) was used to assess the symmetry of the

funnel plot. Sensitivity analysis was performed using the

Leave-One-Out method to evaluate the impact of each individual

study on the overall pooled effect size. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Literature screening results

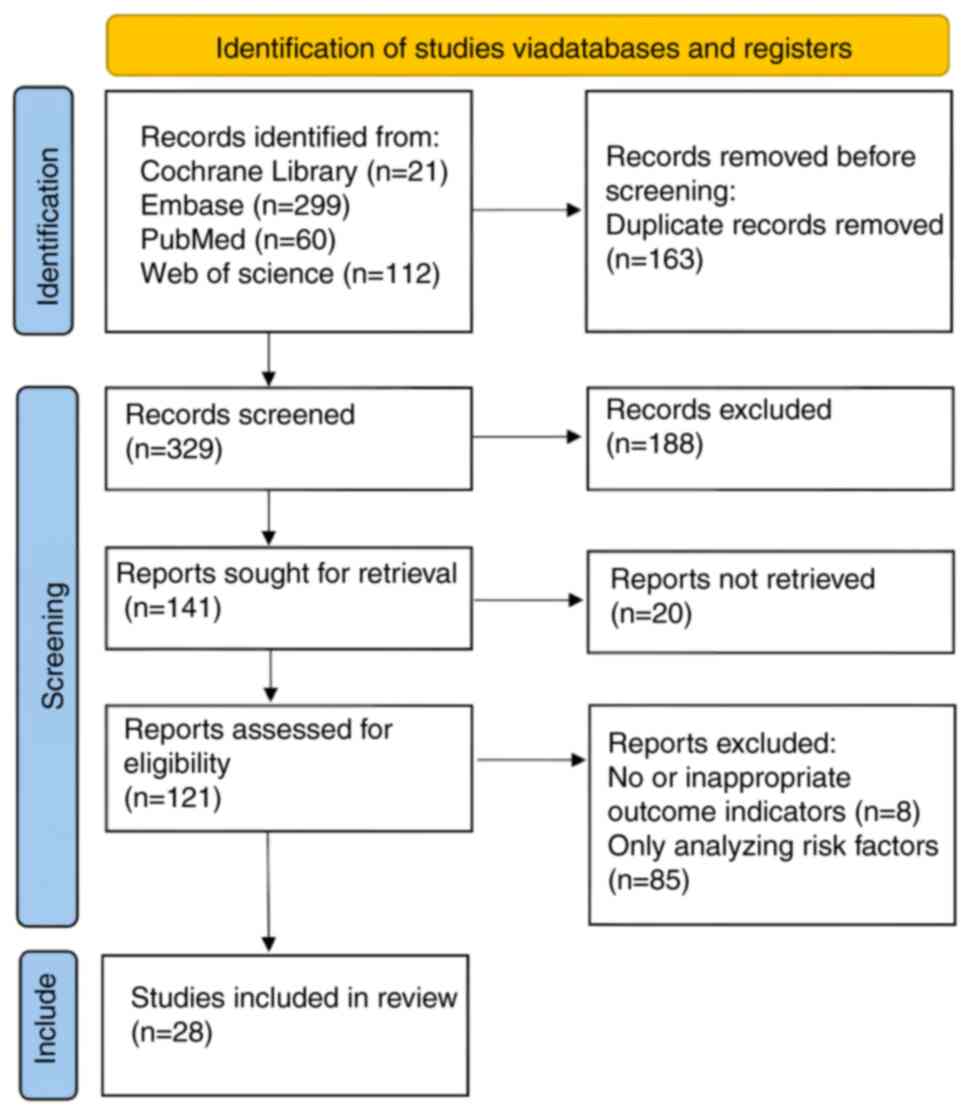

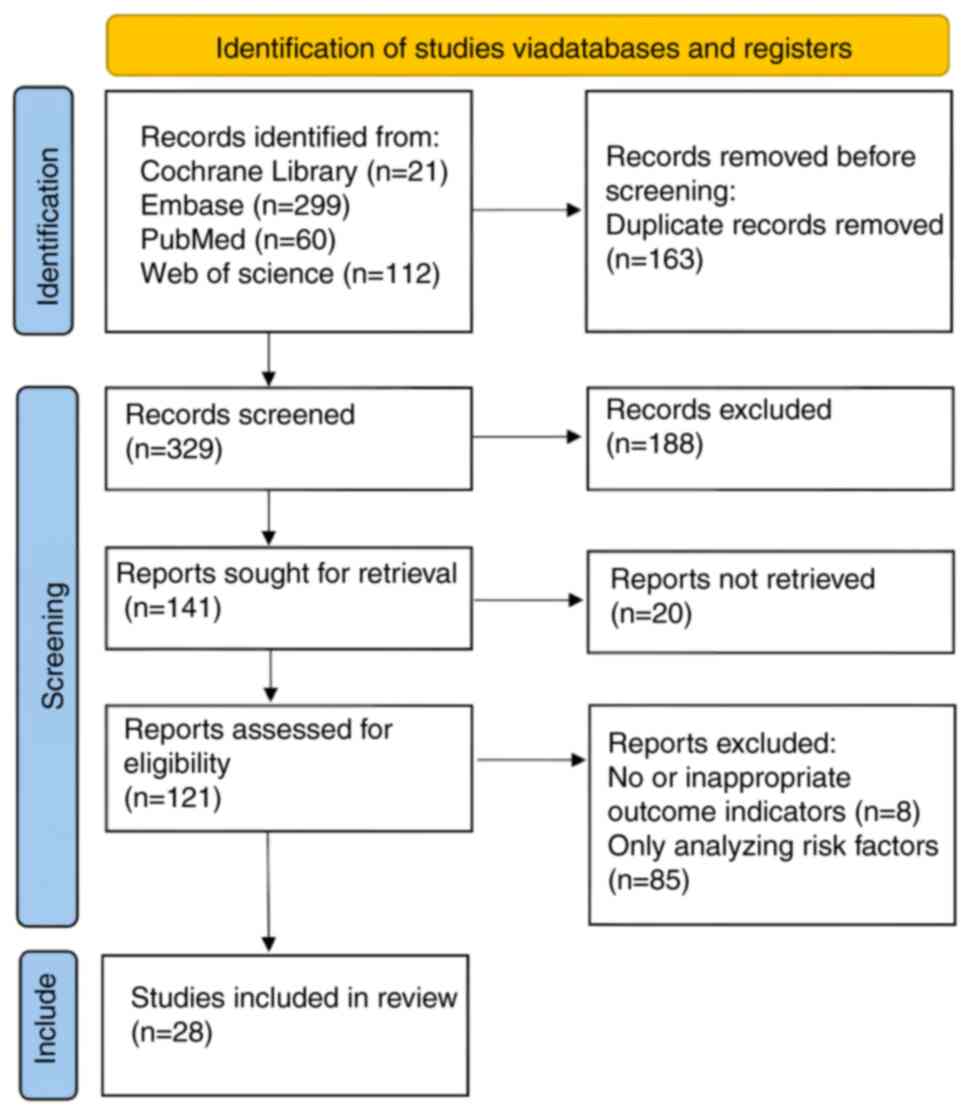

The present study conducted literature screening in

accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines (24). A total of 492 studies were retrieved

through systematic searching; 163 duplicates were removed.

Subsequently, seven meta-analyses, eight reviews, four studies

including animal experiments and 64 conference records, guidelines

and letters were excluded. Additionally, 105 studies that did not

meet the inclusion criteria after title and abstract screening were

excluded. Moreover, 20 studies for which full texts could not be

obtained were excluded, along with eight studies without outcome

indicators and 85 that only focused on risk factor research.

Finally, a total of 28 studies were included (25-52)

(Fig. 1).

| Figure 1Flowchart of literature screening.

Initial retrieval from PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science and

Embase yielded 492 records. After removing 163 duplicates, 329

records remained. Following the exclusion of 83 ineligible records

(meta-analyses, reviews, animal studies, conference abstracts), 246

full texts were assessed. Further exclusions (n=218) included

studies without prediction models. Ultimately, 28 studies were

included, encompassing 28 retinopathy of prematurity risk

prediction models with a total sample size of 72,991 infants. |

Characteristics of the included

studies

The studies were published between 2009 and 2025. A

total of 14 studies (32,34,36,40,41,45,47-49,51,52)

were conducted in East Asia, eight (28,29,31,33,37,38,46,50) in

North America, two each in Europe (30,39)

and South America (25,26), and one each in West (31) and Southeast Asia (27). A total of 11 studies (28,30,33,36,38,40,41,46-48,52)

were multicenter studies. The sample size ranged from 90 to 22,569

cases, with an overall sample size of 72,991 cases (Table SV). A total of 28 items were

included in the ROP risk prediction model (Table SVI).

Model validation

A total of 16 studies (25-27,29,31-35,39,43,45,49-51)

did not mention the specific validation methods, five (28,30,41,42,48)

conducted external validation, two (40,47)

performed both internal and external validation and five (36,38,44,46,52)

performed internal validation. This lack of rigorous validation

limits the generalizability and clinical applicability of existing

ROP risk prediction models.

Literature quality assessment

According to the PROBAST assessment tool, all the

models have an unclear risk of bias (Figs. 2 and 3). This was primarily due to the

susceptibility of retrospective studies to information bias,

limited sample selection affecting representativeness, inconsistent

variable definitions and measurement methods, insufficient control

of confounding factors and small sample sizes that may lead to

model instability. In the future model development process, more

rigorous research designs and standardized variable measurement

methods need to be adopted.

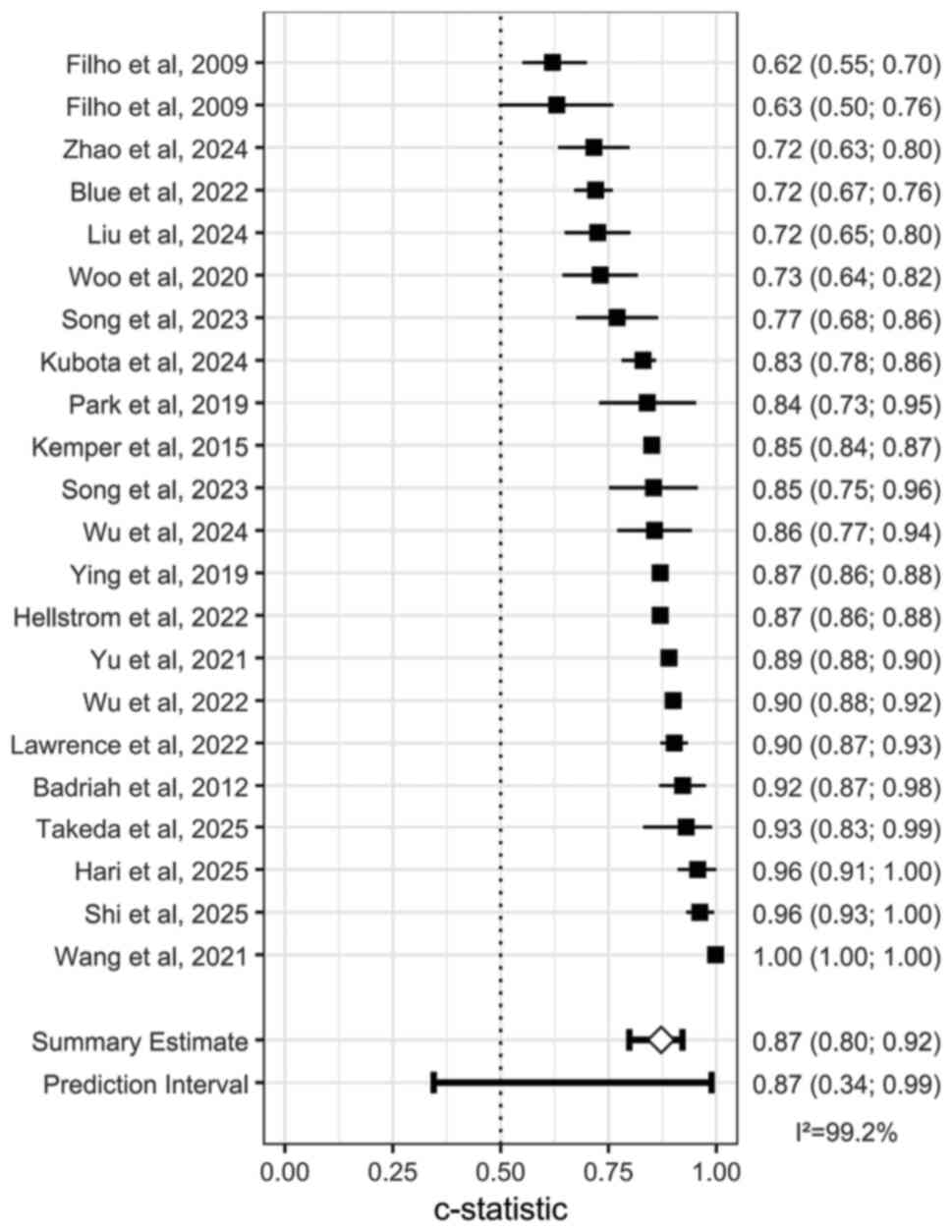

Meta-analysis of risk prediction

models

Due to missing model evaluation data, only 22

studies (25-29,32-34,36-44,47-52)

were included in the analysis. The pooled effect size was AUC=0.87

(95% CI: 0.34; 0.99), indicating good discriminative ability of the

models. However, significant heterogeneity was observed among the

studies (I²=99.2%, P<0.05; Fig.

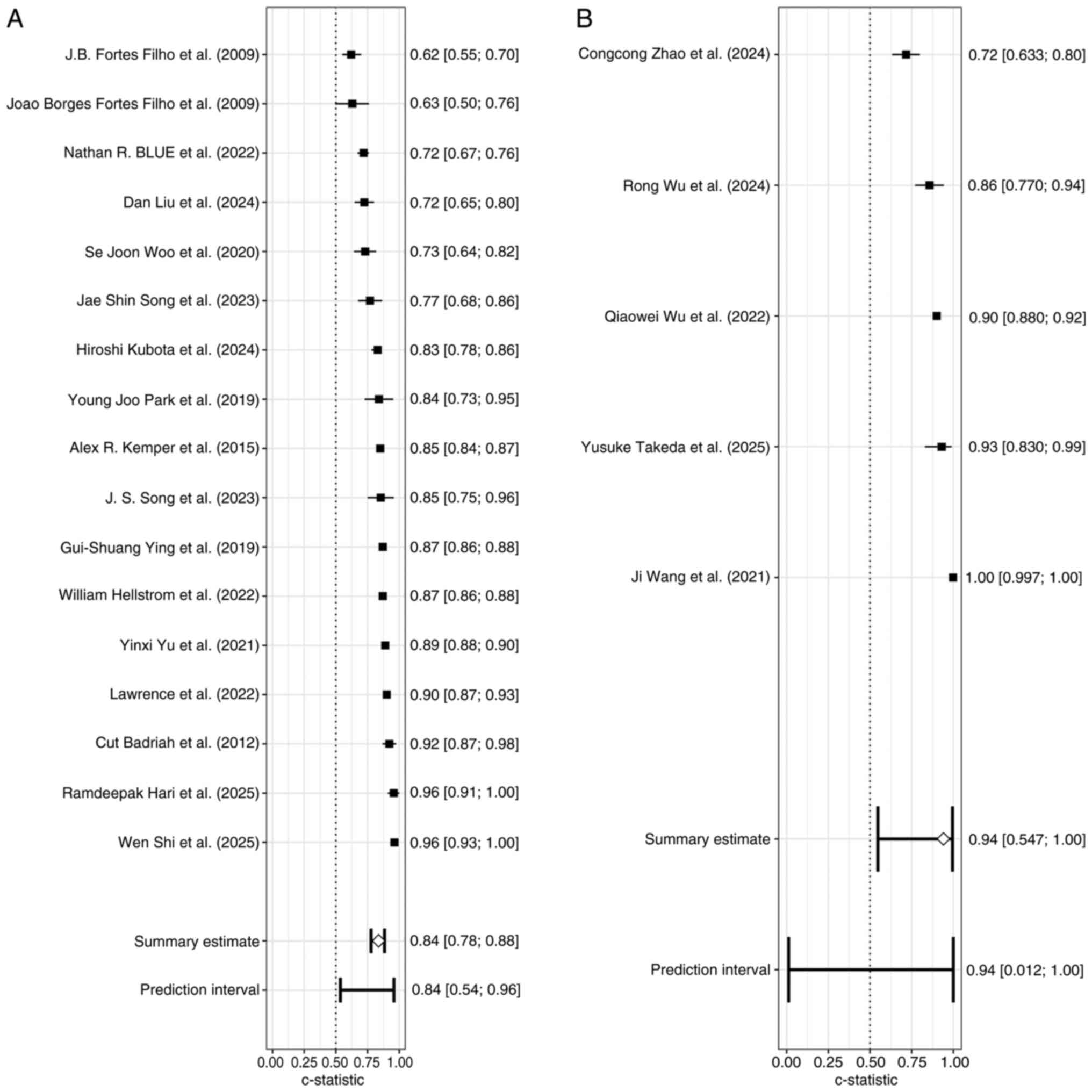

4).

Studies were stratified by modeling approach into

subgroup A [traditional statistical models (logistic regression]

(25-29,32-34,37-39,41-43,45,47,50,51)

and B [machine learning models (neural networks, support vector

machines, long short-term memory, deep learning models] (36,40,48,49,52).

There was significant heterogeneity within both subgroups

(P<0.05), with I²=92.2% in subgroup A and I²=97.3% in subgroup

B. These findings indicated that the differences between studies,

whether using traditional statistical models or machine learning

models were greater than what can be explained by random error,

reflecting substantial methodological or study characteristic

variations (Fig. 5).

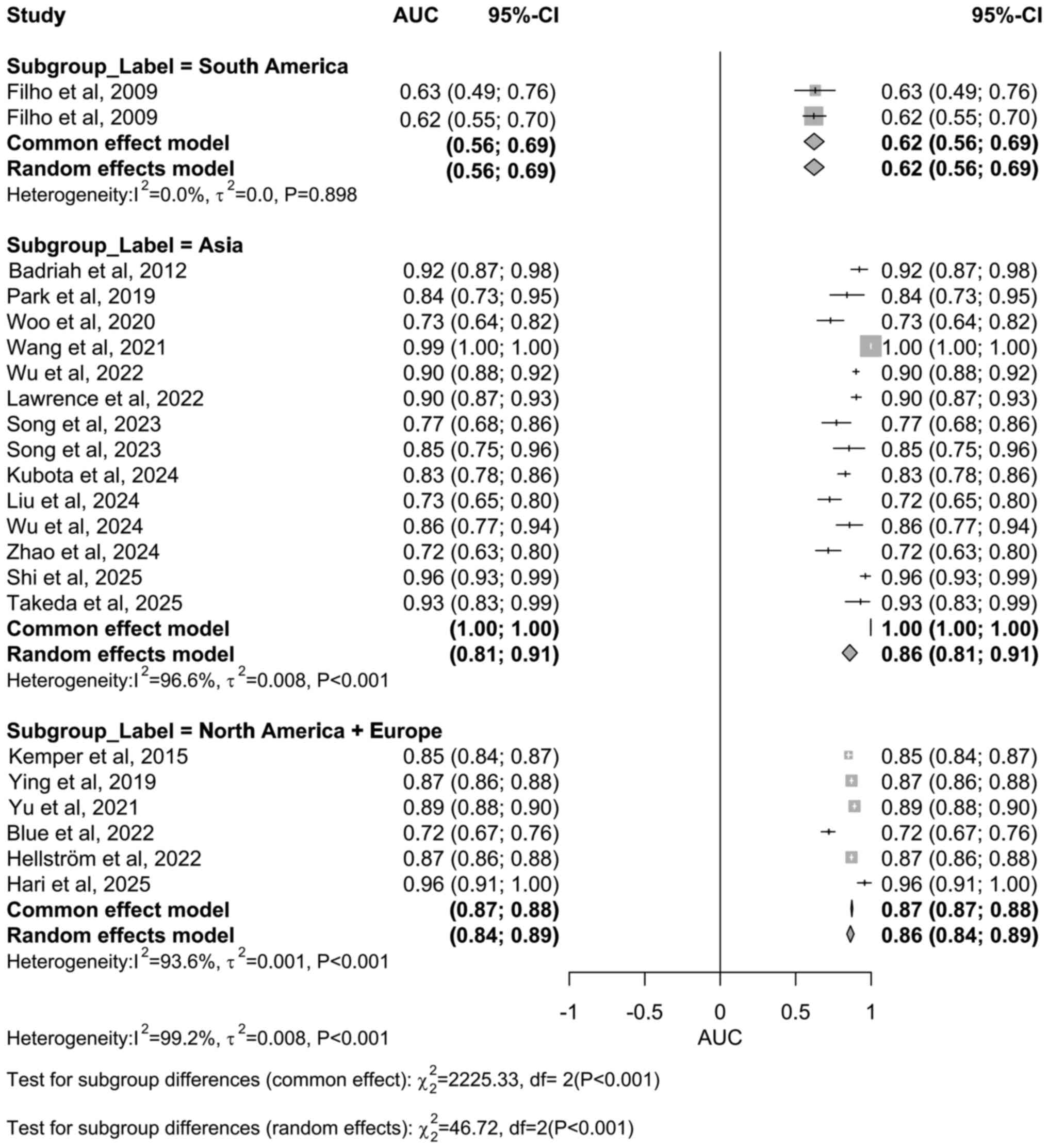

Subgroup analyses were also performed by study

region. The South America subgroup (25,26)

showed I²=0% with P=0.898, indicating highly consistent results and

no statistically significant heterogeneity. By contrast, the Asia

(I²=96.6%) (27,32,36,40-43,45,47-49,51,52)

and North America + Europe subgroup (I²=93.6%) (28,33,37-39,50)

both exhibited very high heterogeneity with P<0.05, suggesting

statistically significant differences in study results within these

regional subgroups (Fig. 6).

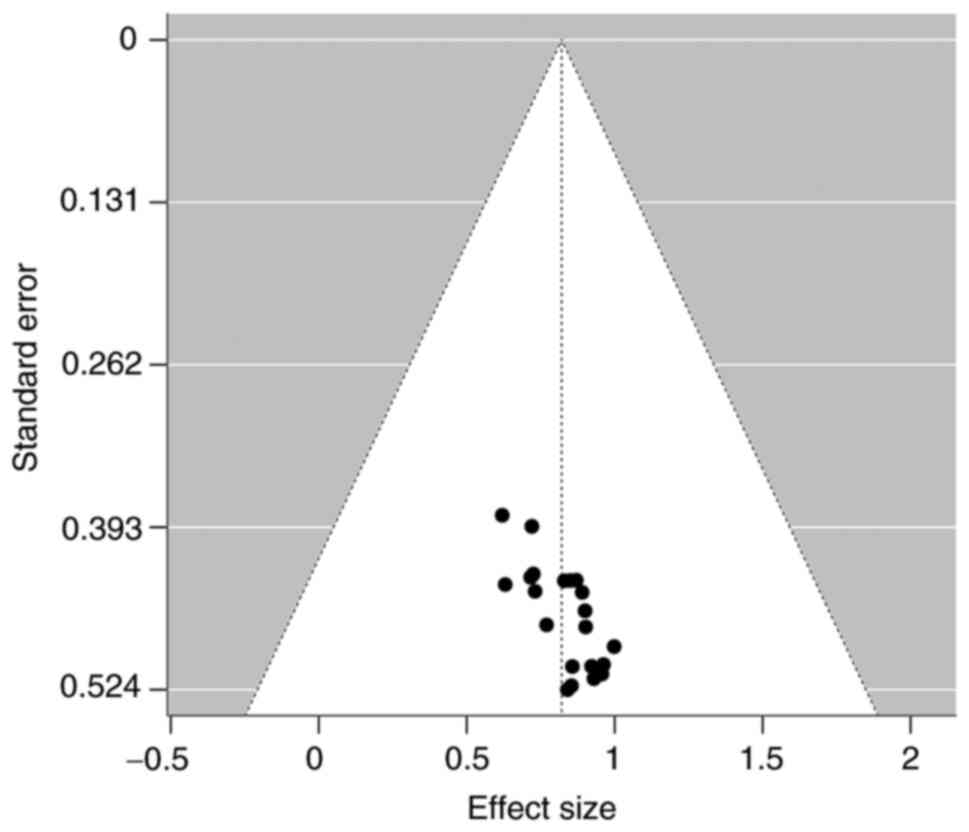

Based on the symmetry of the funnel plot around the

pooled effect size (AUC=0.87), there was no obvious study bias

(Fig. 7). Peters' bias test in

showed t=-0.55, P=0.590, indicating no evidence of significant

bias. This indicated that the findings of the included studies were

not distorted by selective publication, and the overall evidence

chain is highly reliable. From the results of bias assessments, the

overall conclusions of the study are highly credible. The symmetry

of the funnel plot and potential bias issues demonstrated minimal

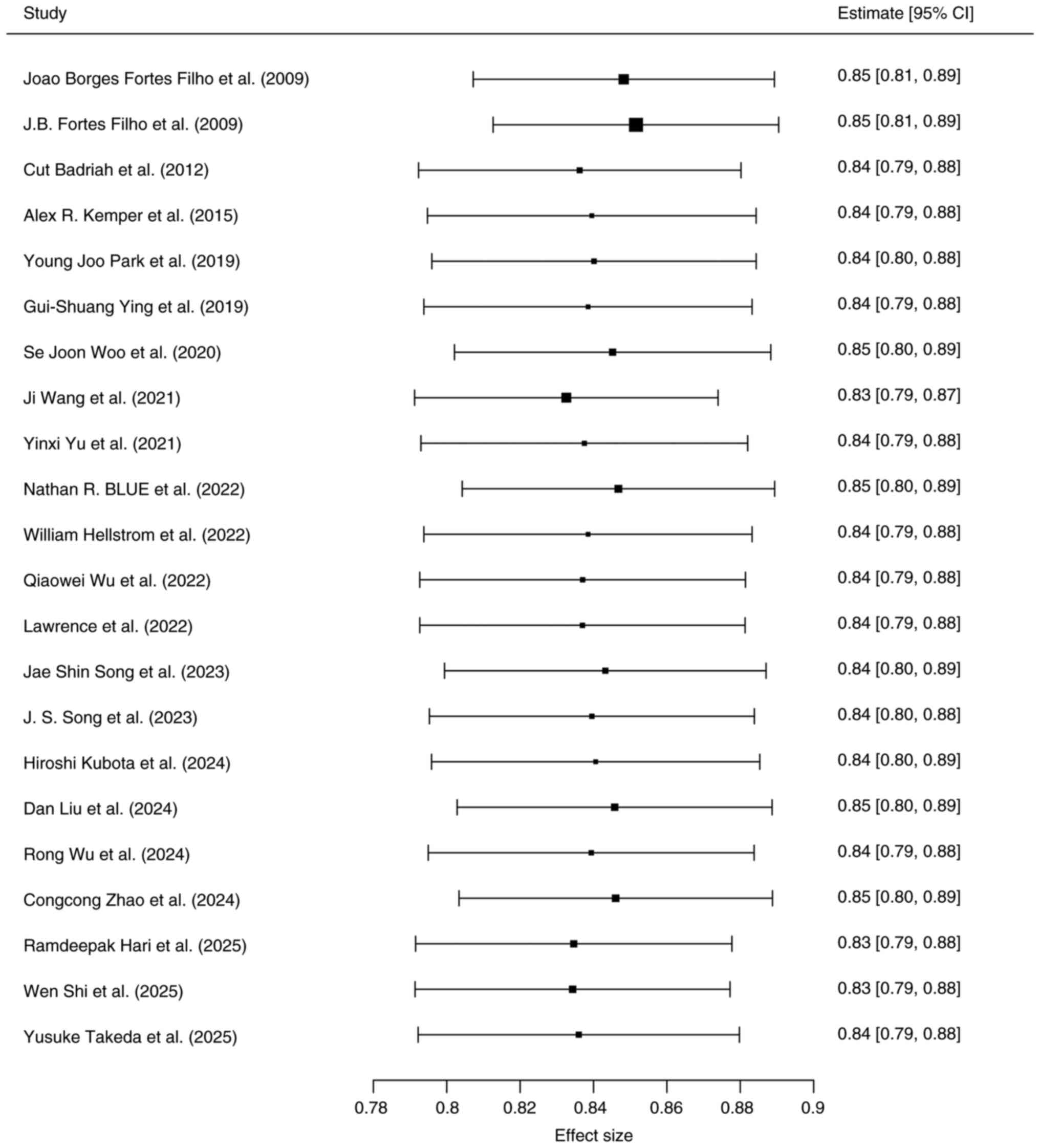

influence on the results. Sensitivity analysis showed that

excluding any single study did not substantially alter the results,

confirming stability (Fig. 8).

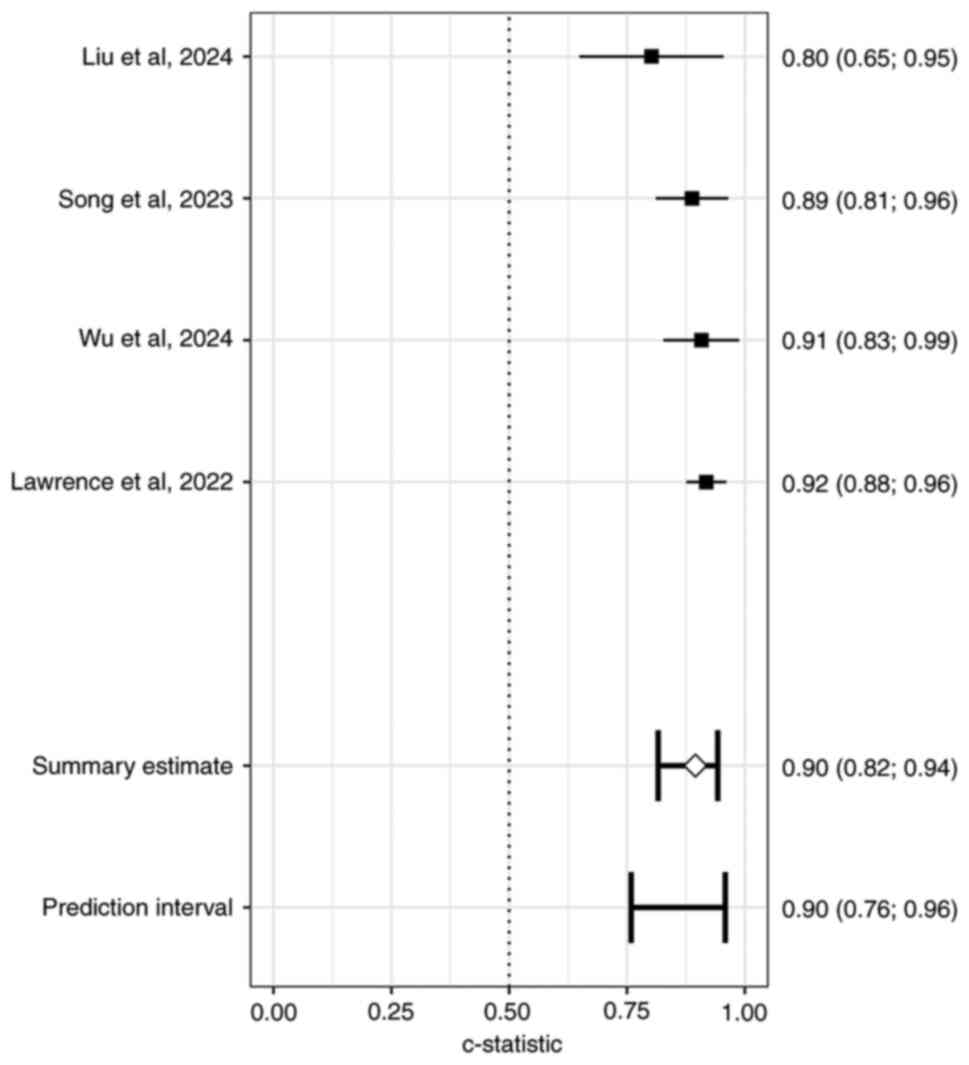

Of the 28 studies, seven reported external

validation; among these, three did not provide 95% CI values for

the external validation AUC. Pooling results from the remaining

four studies (40,41,47,50)

yielded an external validation AUC of 0.90 (0.76; 0.96; Fig. 9). The symmetry of the funnel plot,

non-significant Peters' bias test and stable sensitivity analysis

confirm that the overall findings are not distorted by publication

bias and are robust to individual study exclusion, supporting the

reliability of the meta-analysis conclusions.

Discussion

Effective screening combined with timely

intervention can notably decrease the blindness rate of ROP

(12). Novel imaging technologies

and internet connectivity have transformed the ROP screening model,

with artificial intelligence-supported ROP screening becoming a

research hotspot (53,54). However, existing predictive models

have limitations and are not well-suited for areas with quality

poor neonatal care (55,56). The present study conducted a

meta-analysis to evaluate the performance of current ROP prediction

models and improve ROP risk prediction models.

The present study included 28 ROP risk prediction

models, among which six studies did not provide the 95% CI values

for the AUC. Pooling results from the remaining 22 studies, the AUC

of ROP prediction models was 0.87 (0.34; 0.99), indicating that the

overall performance of ROP risk prediction models is favorable,

with good discriminative ability. However, there was high

heterogeneity between the models. When the models were sub-grouped

into traditional statistical and machine learning models, high

heterogeneity remained within each subgroup. The causes of

heterogeneity were considered to be differences in covariate

selection, sample characteristics and outcome definitions and a

lack of unified standards for data preprocessing and validation

protocols. Regional subgroup analysis showed that studies from

South America had no significant heterogeneity, while those from

Asia, North America and Europe exhibited high heterogeneity. It was

hypothesized that studies in South America showed consistent

results due to the uniformity of population characteristics and

medical standards within the region; by contrast, the high

heterogeneity in Asia, North America and Europe may be attributed

to notable differences in cross-regional population characteristics

and medical systems. Nevertheless, funnel plot symmetry and Peters'

bias test indicated no significant publication bias, and

sensitivity analysis showed stable results, supporting the

reliability of the conclusions. Future studies should reduce

heterogeneity by unifying methodological standards and conducting

multicenter research.

The risk of bias for all the models was unclear.

Badriah et al (27) and Park

et al (32) adopted

retrospective designs, relying on medical record reviews for data

collection. This may introduce information bias due to incomplete

record-keeping or subjective data assignment. The study by Park

et al (32) was a

single-center study, with sample selection limited to a specific

medical setting, which may decrease the generalizability of the

results.

In terms of variable measurement, there were

differences in the definitions and measurement methods of key

predictors across studies. Filho et al (25) used ‘weight gain proportion at 6

weeks after birth’ as an indicator, while Cerda et al

(31) employed changes in z-scores

based on the Fenton growth curve. Such inconsistent standards

limited data comparability. While most studies (25-52)

referenced international classification criteria, Blue et al

(38) and Chen et al

(44) did not explicitly mention

international ROP severity assessment criteria in their relevant

evaluations. In addition, Filho et al (26) and Gerull et al (30) did not explicitly describe the

implementation of assessor blinding, which may introduce subjective

bias, however, the core staging criteria remained consistent.

The multicenter study by Ying et al (33) covered 29 hospitals in North America.

Differences in medical care practices between institutions may have

interfered with the identification of ROP risk factors, but the

study adjusted for key variables such as gestational age and birth

weight through multivariate regression, decreasing confounding

effects to a certain extent. Park et al (32), Hari et al (50), and Shi et al (51) had relatively small sample sizes,

which may pose a risk of model instability. However, owing to the

explicit and rigorous definition of outcome events, the risk of

overfitting (where a model or analytical approach exhibits

excessive adaptation to the original dataset while lacking

generalizability to new data-was kept at a controllable level.

While specific biases were present across multiple dimensions of

the study, they did not substantially compromise the overall

validity of the findings. Consequently, the overall risk of bias

was evaluated as unclear, indicating that although biases exist,

they are not severe enough to invalidate the core conclusions of

the study.

In predictor selection, the included studies did not

report the effectiveness of predictors in practical applications or

clearly specify whether the predictive ability of predictors was

independently evaluated under blinded conditions. In addition,

there were notable differences in terms of predictor selection and

their determination methods. Some studies (45,46)

failed to fully consider potential interactions between predictors.

Multiple included studies consistently identified oxygen therapy as

a key risk factor for ROP; however, the studies did not conduct

in-depth exploration of interaction effects between factors such as

different oxygen therapy modalities and fluctuations in oxygen

concentration. Kubota et al (45) focused on analyzing the association

between oxygen saturation (SpO2) fluctuations and ROP

risk by calculating the total difference in SpO2 values

over the total effective time. On the other hand, Lin et al

(46) mainly focused on relevant

indicators of fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2),

including the average FiO2 and the coefficient of

variation of FiO2, aggregating daily data to smooth

short-term fluctuations and decrease noise. Unlike other studies

(26,27,30,37,40,50)

that may focus only on oxygen concentration or oxygen duration at a

fixed point in time, this previous study emphasized the impact of

the trend in FiO2 changes over time on ROP. In practical

applications, there may be differences in the frequency and method

of FiO2 monitoring and recording between different

medical institutions.

Future studies should adopt prospective designs and

increase sample sizes. This would allow for more precise control of

influencing factors during data collection, enable tracking and

observation of changes in the target population, provide more

representative study samples, and avoid information and selection

biases inherent in retrospective studies. Regularization methods

should be used to limit model degrees of freedom and prevent

overfitting. When constructing prediction models, potential

confounding factors should be controlled.

Of 28 studies, 16 did not mention model validation,

while five conducted internal validation. The internal validation

sample sizes in the studies by Lin et al (46) and Takeda et al (52) were relatively small, which may not

fully capture the various characteristics and associations in the

data. While the models performed well on the training sets, they

may not perform as well in real-world applications. In the study by

Chen et al (44), five-fold

cross-validation was performed on data from 22,569 patients,

improving the training effect of the model and enhancing its

stability and reliability. However, the occurrence and development

of ROP may be influenced by factors such as medical conditions and

environmental factors in different regions. Therefore, it is

essential to include data from different regions and medical

centers for external validation to ensure the general applicability

of the model. The present study combined the external validation

results from four studies (40,41,47,48)

with an external validation model AUC of 0.90 (0.76; 0.96), showing

good external validation performance. However, in clinical

applications, the practical value of the model should be verified

by incorporating other evaluation indicators.

Additionally, in the statistical analysis, certain

studies (25,26) had issues with improper handling of

missing data and insufficient assessment of collinearity. In the

study by Takeda et al (52),

five machine learning methods (decision trees, random forests,

gradient boosting trees, neural networks and naive Bayes) were used

to construct the models. Random forests and naive Bayes models

performed well. Non-imaging machine learning models demonstrated

high performance in predicting ROP occurrence, providing a feasible

predictive approach for hospitals that lack access to retinal

images or pediatric retinal cameras. However, this previous study

acknowledged the small sample size and issues with variable

collinearity. In the future, combining LASSO regression with

embedded feature selection techniques may help control for

collinearity between variables, select a stable and effective set

of features and improve the robustness of the models.

Of 28 studies, 24 reported (25-27,29-35,37,39,40-48,50-52)

that low birth weight in preterm infants is a risk factor for the

occurrence of ROP. Yildirim et al (57) found that, compared with preterm

infants without ROP, the average weight gain in the third week

after birth was significantly lower in infants with ROP; Preterm

infants with low birth weight have underdeveloped retinal vascular

systems, and their blood vessels are structurally and functionally

fragile, making it difficult to cope with abnormal vascular

proliferation, fibrosis and other pathological changes, thereby

increasing the risk of ROP (58).

Additionally, eight studies (33,34,37,42,47,48,49,52)

used the Apgar score to establish prediction models. The Apgar

score primarily evaluates neonatal health status based on heart

rate, respiration, muscle tone, reflexes and skin color. A low

Apgar score often indicates that the newborn experienced asphyxia

or hypoxia at birth, which affects the normal development of the

retinal blood vessels and increases the risk of ROP (59).

Multiple pregnancies are also a risk factor for ROP.

In multiple pregnancies, the blood supply from the placenta is

distributed unevenly, leading to insufficient fetal nutrition, and

restricted growth and development, which often results in low birth

weight (60)

Furthermore, studies (23,27)

have shown that Caucasian infants have a higher risk of developing

ROP compared with other ethnicities. This is because Caucasian

individuals have less pigmentation, making the retinas more

sensitive to oxygen and light damage. Under oxygen therapy or

high-oxygen exposure conditions, the retina is more prone to

vascular development disorders (61). However, a 2006-2017 study (62) of 41 North American hospitals found

African-American infants had lower birth weight and gestational

ages than white and Asian infants; African-American and Asian

infants had significantly lower daily weight gain than Caucasian

infants 31-40 days after birth and after adjusting for birth weight

and gestational age, African-American infants had a lower incidence

of severe ROP than Caucasian and Asian infants. There were no

differences in the incidence or timing of severe ROP between

different ethnicities; this mechanism requires further

exploration.

Although the aforementioned factors have been

confirmed to be associated with ROP in most studies, certain

research (27,32,34,42,43,46,49,50-52)

still has the limitation of having a relatively small sample size.

Additionally, there are notable differences in medical standards,

preterm infant care and environmental factors across regions, and

the level of care provided to infants, including nutritional

support and oxygen therapy management, varies (27,33,35).

It is recommended that pregnant patients at risk of

preterm birth receive prenatal corticosteroids: these medications

accelerate fetal lung maturation, reducing the incidence and

severity of respiratory distress syndrome in preterm infants

(63). Additionally, unnecessary

postnatal ventilation and oxygen therapy for neonates should be

avoided, as excessive oxygen exposure directly disrupts retinal

vascular development. Neonates should also receive high-quality

care and providing targeted management of comorbidities like

bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

The present study had certain limitations: the

systematic review was not pre-registered on the PROSPERO platform,

which decreases the traceability of the research design and

implementation process, and may affect methodological transparency

and the validation of the standardization of the research

protocol.

Future studies should consider combining fundus

images with clinical data and use deep learning methods such as

convolutional and recurrent neural networks, or ensemble learning

algorithms such as random forest, gradient boosting machine and

XGBoost to construct ROP prediction models (58,64).

Such an approach could potentially handle large volumes of complex

non-linear relationships and enable automated feature extraction,

which might provide a more accurate basis for early

screening-though this remains to be validated in future

research.

In summary, existing ROP prediction models have

potential in discriminative ability and may provide references for

preliminary clinical screening. However, their application is

limited by insufficient external validation and inadequate sample

representativeness, and their generalization ability needs to be

improved. Future model development should prioritize multicenter,

large-sample prospective designs, control confounding factors, and

systematically incorporate data from populations with different

medical resource backgrounds and ethnic groups to enhance the

generalizability of results. Meanwhile, it is necessary to

strengthen external validation processes, explore multimodal fusion

of fundus images and clinical indicators, introduce deep learning

or ensemble learning methods to handle complex data associations

and explore potential biomarkers associated with ROP, thereby

providing more reliable tools for early accurate screening and

intervention for neonatal ROP.

Supplementary Material

PubMed database search strategy.

Web of Science database search

strategy.

Embase database search strategy.

Cochrane Library database search

strategy.

Study characteristics.

Prediction model characteristics.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National Natural

Science Foundation of China (grant no. 82160205) and the Tianjin

Key Medical Discipline (Specialty) Construction Project (grant no.

TJYXZDXK-3-004A-3).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LL and YG confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data. LL and YG designed and performed the experiments and wrote

the manuscript. WC interpreted data. MH conceived the study. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Fu Y, Lei C, Qibo R, Huang X, Chen Y, Wang

M and Zhang M: Insulin-like growth factor-1 and retinopathy of

prematurity: A systemic review and meta-analysis. Surv Ophthalmol.

68:1153–1165. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

García H, Villasis-Keever MA,

Zavala-Vargas G, Bravo-Ortiz JC, Pérez-Méndez A and Escamilla-Núñez

A: Global prevalence and severity of retinopathy of prematurity

over the last four decades (1985-2021): A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Arch Med Res. 55(102967)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Bhatnagar A, Skrehot HC, Bhatt A, Herce H

and Weng CY: Epidemiology of retinopathy of prematurity in the US

from 2003 to 2019. JAMA Ophthalmol. 141:479–485. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Chiang MF, Quinn GE, Fielder AR, Ostmo SR,

Chan RV, Berrocal A, Binenbaum G, Blair M, Campbell JP, Capone A

Jr, et al: International classification of retinopathy of

prematurity, third edition. Ophthalmology. 128:e51–e68.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Schmitz AM, Bumbaru SM, Fakhouri LS and

Zhang DQ: Long-term impairment of retinal ganglion cell function

after oxygen-induced retinopathy. Cells. 14(512)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Beccasio A, Mignini C, Caricato A,

Iaccheri B, Di Cara G, Verrotti A and Cagini C: New trends in

intravitreal anti-VEGF therapy for ROP. Eur J Ophthalmol.

32:1340–1351. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Sankar BK, Amin H, Pappa P and Riaz KM:

Risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity: A prospective study.

Indian J Public Health. 69:111–114. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Karmouta R, Strawbridge JC, Langston S,

Altendahl M, Khitri M, Chu A and Tsui I: Neurodevelopmental

outcomes in infants screened for retinopathy of prematurity. JAMA

Ophthalmol. 141:1125–1132. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Tan H, Blasco P, Lewis T, Ostmo S, Chiang

MF and Campbell JP: Neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants

with retinopathy of prematurity. Surv Ophthalmol. 66:877–891.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Almutairi MF, Gulden S, Hundscheid TM,

Bartoš F, Cavallaro G and Villamor E: Platelet counts and risk of

severe retinopathy of prematurity: A bayesian model-averaged

meta-analysis. Children (Basel). 10(1903)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Nakayama LF, Mitchell WG, Ribeiro LZ,

Dychiao RG, Phanphruk W, Celi LA, Kalua K, Santiago APD, Regatieri

CVS and Moraes NSB: Fairness and generalisability in deep learning

of retinopathy of prematurity screening algorithms: A literature

review. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 8(e001216)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Kim SJ, Port AD, Swan R, Campbell JP, Chan

RVP and Chiang MF: Retinopathy of prematurity: A review of risk

factors and their clinical significance. Surv Ophthalmol.

63:618–637. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Shah S, Slaney E, VerHage E, Chen J, Dias

R, Abdelmalik B, Weaver A and Neu J: Application of artificial

intelligence in the early detection of retinopathy of prematurity:

Review of the literature. Neonatology. 120:558–565. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hellström A and Hård AL: Screening and

novel therapies for retinopathy of prematurity-A review. Early Hum

Dev. 138(104846)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Diggikar S, Gurumoorthy P, Trif P, Mudura

D, Nagesh NK, Galis R, Vinekar A and Kramer BW: Retinopathy of

prematurity and neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pediatr.

11(1055813)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Collins GS, Moons KGM, Dhiman P, Riley RD,

Beam AL, Van Calster B, Ghassemi M, Liu X, Reitsma JB, van Smeden

M, et al: TRIPOD+AI statement: Updated guidance for reporting

clinical prediction models that use regression or machine learning

methods. BMJ. 385(e078378)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Fernandez-Felix BM, López-Alcalde J, Roqué

M, Muriel A and Zamora J: CHARMS and PROBAST at your fingertips: A

template for data extraction and risk of bias assessment in

systematic reviews of predictive models. BMC Med Res Methodol.

23(44)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Moons KGM, Damen JAA, Kaul T, Hooft L,

Navarro CA, Dhiman P, Beam AL, Van Calster B, Celi LA, Denaxas S,

et al: PROBAST+AI: An updated quality, risk of bias, and

applicability assessment tool for prediction models using

regression or artificial intelligence methods. BMJ.

388(e082505)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Fu H, Hou D, Xu R, You Q, Li H, Yang Q,

Wang H, Gao J and Bai D: Risk prediction models for deep venous

thrombosis in patients with acute stroke: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 149(104623)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Kuo RYL, Harrison C, Curran TA, Jones B,

Freethy A, Cussons D, Stewart M, Collins GS and Furniss D:

Artificial intelligence in fracture detection: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. Radiology. 304:50–62. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

de Jong Y, Ramspek CL, Zoccali C, Jager

KJ, Dekker FW and van Diepen M: Appraising prediction research: A

guide and meta-review on bias and applicability assessment using

the prediction model risk of bias ASsessment tool (PROBAST).

Nephrology (Carlton). 26:939–947. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J,

Welch VA, Higgins JP and Thomas J: Updated guidance for trusted

systematic reviews: A new edition of the cochrane handbook for

systematic reviews of interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

10(ED000142)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Furuya-Kanamori L, Barendregt JJ and Doi

SAR: A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting

bias in meta-analysis. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 16:195–203.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Filho JB, Bonomo PP, Maia M and Procianoy

RS: Weight gain measured at 6 weeks after birth as a predictor for

severe retinopathy of prematurity: Study with 317 very low birth

weight preterm babies. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol.

247:831–836. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Filho JB, Dill JC, Ishizaki A, Aguiar WW,

Silveira RC and Procianoy RS: Score for neonatal acute physiology

and perinatal extension II as a predictor of retinopathy of

prematurity: Study in 304 very-low-birth-weight preterm infants.

Ophthalmologica. 223:177–182. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Badriah C, Amir I, Elvioza E and Ifran E:

Prevalence and risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity.

Paediatrica Indonesiana. 52:138–144. 2012.

|

|

28

|

Kemper AR, Wade KC, Hornik CP, Ying GS,

Baumritter A and Quinn GE: Telemedicine Approaches to Evaluating

Acute-phase Retinopathy of Prematurity (e-ROP) Study Cooperative

Group. Retinopathy of prematurity risk prediction for infants with

birth weight less than 1251 grams. J Pediatr. 166:257–261.e2.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Owen LA, Morrison MA, Hoffman RO, Yoder BA

and DeAngelis MM: Retinopathy of prematurity: A comprehensive risk

analysis for prevention and prediction of disease. PLoS One.

12(e0171467)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Gerull R, Brauer V, Bassler D, Laubscher

B, Pfister RE, Nelle M, Müller B, Roth-Kleiner M, Gerth-Kahlert C

and Adams M: Swiss Neonatal Network & Follow-up Group.

Prediction of ROP treatment and evaluation of screening criteria in

VLBW infants-a population based analysis. Pediatr Res. 84:632–638.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Cerda AM, McCourt EA, Thevarajah T, Wymore

E, Lynch AM and Wagner BD: Comparison between weight gain and

Fenton preterm growth z scores in assessing the risk of retinopathy

of prematurity. J AAPOS. 23:281–283. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Park YJ, Woo SJ, Kim YM, Hong S, Lee YE

and Park KH: Immune and inflammatory proteins in cord blood as

predictive biomarkers of retinopathy of prematurity in preterm

infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 60:3813–3820. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ying GS, Bell EF, Donohue P, Tomlinson LA

and Binenbaum G: G-ROP Research Group. Perinatal risk factors for

the retinopathy of prematurity in postnatal growth and rop study.

Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 26:270–278. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Woo SJ, Park JY, Hong S, Kim YM, Park YH,

Lee YE and Park KH: Inflammatory and angiogenic mediators in

amniotic fluid are associated with the development of retinopathy

of prematurity in preterm infants. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci.

61(42)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Fekri Y, Ojaghi H, Momeni N and Amani F:

Retinopathy of prematurity in Ardabil, North West of Iran:

Prevalence and risk factors. Eur J Transl Myol.

31(10063)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Wang J, Ji J, Zhang M, Lin JW, Zhang G,

Gong W, Cen LP, Lu Y, Huang X, Huang D, et al: Automated

explainable multidimensional deep learning platform of retinal

images for retinopathy of prematurity screening. JAMA Netw Open.

4(e218758)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Yu Y, Tomlinson LA, Binenbaum G and Ying

GS: G-Rop Study Group. Incidence, timing and risk factors of type 1

retinopathy of prematurity in a North American cohort. Br J

Ophthalmol. 105:1724–1730. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Blue NR, Allshouse AA, Grobman WA, Day RC,

Haas DM, Simhan HN, Parry S, Saade GR and Silver RM: Developing a

predictive model for perinatal morbidity among small for

gestational age infants. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 35:8462–8471.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Hellström W, Martinsson T, Morsing E,

Gränse L, Ley D and Hellström A: Low fraction of fetal haemoglobin

is associated with retinopathy of prematurity in the very preterm

infant. Br J Ophthalmol. 106:970–974. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wu Q, Hu Y, Mo Z, Wu R, Zhang X, Yang Y,

Liu B, Xiao Y, Zeng X, Lin Z, et al: Development and validation of

a deep learning model to predict the occurrence and severity of

retinopathy of prematurity. JAMA Netw Open.

5(e2217447)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Iu LPL, Yip WWK, Lok JYC, Fan MCY, Lai

CHY, Ho M and Young AL: Prediction model to predict type 1

retinopathy of prematurity using gestational age and birth weight

(PW-ROP). Br J Ophthalmol. 107:1007–1011. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Song JS, Woo SJ, Park KH, Joo E, Kim H, Oh

E and Lee KN: Cord blood transforming growth factor-β-induced as

predictive biomarker of retinopathy of prematurity in preterm

infants. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 261:2477–2488.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Song JS, Woo SJ, Park KH, Kim H, Lee KN

and Kim YM: Association of inflammatory and angiogenic biomarkers

in maternal plasma with retinopathy of prematurity in preterm

infants. Eye (Lond). 37:1802–1809. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Chen S, Zhao X, Wu Z, Cao K, Zhang Y, Tan

T, Lam CT, Xu Y, Zhang G and Sun Y: Multi-risk factors joint

prediction model for risk prediction of retinopathy of prematurity.

EPMA J. 15:261–274. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Kubota H, Fukushima Y, Kawasaki R, Endo T,

Hatsukawa Y, Ineyama H, Hirata K, Hirano S, Wada K and Nishida K:

Continuous oxygen saturation and risk of retinopathy of prematurity

in a Japanese cohort. Br J Ophthalmol. 108:1275–1280.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Lin WC, Jordan BK, Scottoline B, Ostmo SR,

Coyner AS, Singh P, Kalpathy-Cramer J, Erdogmus D, Chan RVP, Chiang

MF and Campbell JP: Oxygenation fluctuations associated with severe

retinopathy of prematurity: Insights from a multimodal deep

learning approach. Ophthalmol Sci. 4(100417)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Liu D, Li XY, He HW, Jin KL, Zhang LX,

Zhou Y, Zhu ZM, Jiang CC, Wu HJ and Zheng SL: Nomogram to predict

severe retinopathy of prematurity in Southeast China. Int J

Ophthalmol. 17:282–288. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Wu R, Chen H, Bai Y, Zhang Y, Feng S and

Lu X: Prediction models for retinopathy of prematurity occurrence

based on artificial neural network. BMC Ophthalmol.

24(323)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Zhao C, Sun Z, Chen H, Li K and Sun H: The

impact of blood lactic acid levels on retinopathy of prematurity

morbidity. BMC Pediatr. 24(152)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Hari R, Mellacheruvu P, Nonye OC, Rastogi

A and Mydam J: Severe patent ductus arteriosus is a risk factor for

clinically significant retinopathy of prematurity in very low birth

weight infants. SN Compr Clin Med. 7(60)2025.

|

|

51

|

Shi W, Zhu L, He X, Wang S and Wang C:

Combined indicator assists in early recognition of retinopathy of

prematurity. Sci Rep. 15(8048)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Takeda Y, Kaneko Y, Sugimoto M, Yamashita

H, Sasaki A and Mitsui T: Prediction models for retinopathy of

prematurity using nonimaging machine learning approaches: A

regional multicenter study. Ophthalmol Sci.

5(100715)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wagner SK, Liefers B, Radia M, Zhang G,

Struyven R, Faes L, Than J, Balal S, Hennings C, Kilduff C, et al:

Development and international validation of custom-engineered and

code-free deep-learning models for detection of plus disease in

retinopathy of prematurity: A retrospective study. Lancet Digit

Health. 5:e340–e349. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Rashidian P, Karami S and Salehi SA: A

review on retinopathy of prematurity. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov

Ophthalmol. 13:201–212. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Maitra P, Shah PK, Campbell PJ and Rishi

P: The scope of artificial intelligence in retinopathy of

prematurity (ROP) management. Indian J Ophthalmol. 72:931–934.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Xu S, Liang Z, Du Q, Li Z, Tan G, Nie C,

Yang Y, Lv X, Zhang C and Luo X: A systematic study on the

prevention and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity in China.

BMC Ophthalmol. 18(44)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Yildirim M, Coban A, Bulut O, Mercül NK

and Ince Z: Postnatal weight gain and retinopathy of prematurity in

preterm infants: A population-based retrospective cohort study. J

Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 37(2337720)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Han G, Lim DH, Kang D, Cho J, Guallar E,

Chang YS, Chung TY, Kim SJ and Park WS: Association between

retinopathy of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight infants and

neurodevelopmental impairment. Am J Ophthalmol. 244:205–215.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Dammann O, Hartnett ME and Stahl A:

Retinopathy of prematurity. Dev Med Child Neurol. 65:625–631.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Engin CD, Ozturk T, Ozkan O, Oztas A,

Selver MA and Tuzun F: Prediction of retinopathy of prematurity

development and treatment need with machine learning models. BMC

Ophthalmol. 25(194)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Gilbert CE: Global perspectives of

retinopathy of prematurity. Indian J Ophthalmol. 71:3431–3433.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Wang J, Ying GS, Yu Y, Tomlinson L and

Binenbaum G: Racial differences in retinopathy of prematurity.

Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 30:523–531. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kim ES, Calkins KL and Chu A: Retinopathy

of prematurity: The role of nutrition. Pediatr Ann. 52:e303–e308.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

He D, Luo X, Ying B, Quinn GE, Baumritter

A, Chen Y, Ying GS and He L: Machine learning models for predicting

treatment-requiring retinopathy of prematurity in the e-ROP study.

Transl Vis Sci Technol. 14(14)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|