Introduction

The total number of patients with type 1 diabetes

mellitus (T1DM) is steadily rising. In 2025, an estimated 9.5

million people worldwide are living with T1DM, representing a 13%

increase compared with the 8.4 million reported in 2021. Since the

genetic transmission of this disease has remained relatively

constant, this growing prevalence suggests the involvement of

alternative risk factors, including environmental triggers,

lifestyle influences, and changes in early-life exposures. These

include pollutants, endocrine disruptors, vitamin D deficiency and

pathological colonization of the gastrointestinal tract (1,2).

The gastrointestinal microbiota (the colonization of

the gastrointestinal tract) comprises all bacteria, viruses and

fungi that inhabit this environment. An imbalance of this

microbiota (dysbiosis) with more proinflammatory bacteria that

affect the immune system is hypothesized to explain the global rise

in T1DM, especially the early onset of this disease (1-3).

The balance of the gut microbiota is disrupted by

various factors, leading to dysbiosis, which serves a vital role in

the development and progression of numerous types of disease,

including type 2 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune diseases such as

Hashimoto's thyroiditis and Chon's disease (4). The onset of T1DM, especially with

onset at younger ages, represents a global health challenge, as it

does not affect all individuals with genetic susceptibility

(5). The alterations in microbiota

and chronic inflammation, due to environmental influences, are

hypothesized as explanations for the shifts in the prevalence of

this disease (5,6).

Several mouse studies have provided evidence of a

potential link between microbiota and T1DM (7-9).

For example, exposure to antibiotics in the prenatal period or in

the first weeks after birth influences the gut microbiota and the

T1DM incidence by reducing the pancreatic inflammation and levels

of pro-inflammatory cytokines (10-14).

In the context of T1DM, changes in the gut

microbiota have been observed prior to the emergence of systemic

signs of islet autoimmunity (15,16).

This shift in microbiota could be attributed to the fact that

previous studies primarily identified these modifications through

gene analysis of 16S rRNA, which may not capture specific

structural and functional characteristics potentially involved in

disease progression (17,18). Later studies used specialized

designs to control all known factors influencing T1DM

susceptibility and analyzed microbiome characteristics using

longitudinal metagenomic sequencing of stool samples (19,20).

Patients with T1DM harbor a proinflammatory environment,

irrespective of geographical location, with a higher abundance of

Bacteroidetes and a lower abundance of Firmicutes

(21,22).

Decreased levels of Firmicutes (comprising strains

of Clostridium and Eubacterium) may pose a risk to

the host as this phylum encompasses numerous producers of the

short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) butyrate (23). Butyrate is key for intestinal

homeostasis, serving as an energy source for colonocytes and

promoting the secretion of mucins. This aids in reducing gut

permeability by facilitating the formation of tight junctions

(13,17,18,22,23)

and protecting against pathogens and harmful substances (21,24,25).

The Bacteroidetes phylum contains strains of Bacteroides and

Prevotella. Studies have shown that T1DM is characterized by

a dominance of Bacteroides, taxa associated with intestinal

inflammation, while levels of protective Prevotella are

decreased (26-28).

Species within the Bacteroides genus ferment

glucose and lactate to produce propionate, acetate and succinate,

but they lack the ability to generate butyrate (29). Additionally, lactate-producing

bacteria, including certain probiotic strains such as

Lactobacillus rhamnosus, L. reuteri, L. johnsonii N6.2,

L. plantarum and Bifidobacterium lactis, synthesize

butyrate, thereby reinforcing the intestinal barrier function

(26). These findings underscore

the role of the gut microbiota in T1DM and suggest that targeting

specific microbial components may have potential for interventions

aimed at supporting intestinal health in individuals with T1DM

(1,21,27-30).

Similar to autoimmune conditions, T1DM prevalence

exhibits a geographical pattern: The EURODIAB Autoimmune

Complications of Type 1 Diabetes study (1989-1990) reported

incidence rates of ~42.9 per 100,000/year in Finland, compared with

4.6/100,000/year in northern Greece (31). Climate, particularly sunlight

exposure, influences microbiota and impacts the immune system.

Vitamin D deficiencies and disturbances in the circadian rhythm

alter the gut microbiota, contributing to the development of

autoimmune disease (2,28,30).

Evidence suggests that vitamin D levels are lower in

newly diagnosed patients with T1DM compared with population

controls (32,33). Moreover, the supplementation of this

vitamin and the risk of T1DM show a dose-response effect (30).

The composition of early-life microbiota undergoes

frequent changes influenced by maternal and environmental microbes,

as well as exposure to food and animal-borne antigens. The method

of birth, whether cesarean or vaginal, has an impact on the

neonatal microbiota; findings from the TEDDY study indicate that

children delivered vaginally exhibit higher levels of

Bacteroides, which are associated with increased diversity

and accelerated maturation of gut intestinal flora (14,34).

An increasing number of studies underscore the role

of environmental factors in the rising incidence of T1DM,

particularly among younger children (35,36);

to the best of our knowledge, however, there are few studies from

Romania or Eastern Europe (37-39).

Given the geographical variation in T1DM, the data available may

not entirely align with the actual pathogenesis of T1DM.

Investigating the association between T1DM onset and

gut microbiota dysbiosis may foster collaborations between

researchers, clinicians and policymakers, leading to the

development of novel diagnostic tools, therapeutic interventions

and tailored public health policies.

Considering the cultural, dietary and environmental

changes that have occurred in Eastern Europe over the past three

decades, it has been hypothesized that alterations in the gut

microbiome may contribute to a decreased age at onset of T1DM, as

well as a more severe clinical presentation. Longitudinal

microbiome studies have shown that changes in microbial composition

and function, including a reduction in short-chain fatty acid

producers and enrichment of pro-inflammatory taxa, occur prior to

or around the development of islet autoimmunity and overt T1DM

(11,14). In parallel, epidemiological studies

from Eastern Europe, including Romania and Poland, have reported an

increase in T1DM incidence since the 1990s, with diagnosis

occurring at progressively younger ages (37,40).

At the time of diagnosis, a notable proportion of patients present

with diabetic ketoacidosis, reflecting both delayed recognition and

a more severe onset of disease, which may be associated with

environmental and microbial risk factors (41). Moreover, it has been well documented

that T1DM frequently coexists with other autoimmune diseases, such

as thyroid autoimmunity and celiac disease, further supporting a

role for shared environmental drivers, including gut microbiome

dysregulation, in shaping disease course and comorbidity (42,43).

The aim of the present study was to analyze the gut

microbiota composition in Romanian children with newly diagnosed

T1DM, and to investigate its potential associations with age of

onset, severity at presentation, glycemic control, and co-existing

autoimmune conditions.

Materials and methods

Study population

The present retrospective case-control pilot study

involved 31 pediatric patients (age, 1-18 years, 16 female and 15

male) diagnosed with T1DM within the past 6 months, based on the

criteria set by the American Diabetes Association (44).

The inclusion criteria for the patients were as

follows: i) Positive clinical T1DM diagnosis and ii) onset <6

months prior to admission. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

i) Antibiotic/probiotic administration in the 2 weeks prior to the

admission; ii) T1DM diagnosed >6 months previously and iii)

other types of diabetes mellitus.

These inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients

in the study were established to identify relevant changes in the

gut microbiota in patients with type 1 diabetes, in light of

observational evidence showing that individuals with type 1

diabetes exhibit altered fecal and oral microbiota composition,

reduced butyrate-producing species, and lower plasma levels of

acetate and propionate (45).

Patients were referred either by their primary care

physician or transferred from other pediatric hospitals in the

southern region of Romania to the Pediatric Endocrinology and

Diabetes Department at Elias Emergency and University Hospital,

Bucharest (Romania). Being one of three referral centers for

evaluating and initiating continuous glucose monitor devices and

insulin pumps reimbursed by the National Health System in the

southern region, most patients with recently diagnosed T1DM sought

treatment here. All participants were of Caucasian ethnicity, as

defined by Thomson et al (46). All eligible pediatric patients,

admitted between January 2019 and December 2021, were enrolled in

chronological order of admission. The study adhered to the Helsinki

Declaration of 2013, with parental approval obtained through

written informed consent for the use of medical records in

scientific research.

Patients with newly diagnosed T1DM were matched with

healthy children of similar age (4-18 years), sex, BMI and urban

environment. First-degree relatives with known T1DM were also

evaluated to assess the influence of genetic and environmental

factors. A comprehensive medical history, including demographics,

family history of autoimmune diseases and/or diabetes, personal

medical history, birth details, breastfeeding practices, infection

history and treatment details, was obtained from all participants.

Anthropometric measurements were conducted, including age, weight,

height, BMI, blood pressure, Tanner stage (47) and waist-to-hip ratio. Data were

collected from medical records and laboratory reports, and compiled

in an Excel Spreadsheet (version 16.0 (Microsoft Corporation)

Laboratory procedures

A 10 ml peripheral blood sample was obtained 8 h

after the last meal to assess hematological and biochemical

parameters. The complete blood count and blood chemistry analyses

included measurements of glucose, creatinine, total cholesterol,

high- and low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol, triglycerides,

glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), hepatic function and reactive

C-protein (CRP). Additionally, levels of anti-thyroglobulin and

anti-thyroperoxidase (for autoimmune thyroid disorders) and

anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (for celiac disease) were

measured to assess autoimmune conditions. Thyroid function was

evaluated based on thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and free

thyroxine (fT4) levels. Furthermore, assessments were made for

insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1), 25-hydroxy vitamin D [25(OH)

vitamin D], and phosphorus-calcium metabolism, including

measurements of total serum calcium, phosphorus and parathyroid

hormone (PTH).

ELISA

The levels of 25(OH) vitamin D, anti-thyroglobulin,

anti-thyroperoxidase and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies

were determined using ELISA on a Chemwell 2010 ELISA system

(Awareness Technology, Inc.) using commercially available kits as

follows: 25(OH) Vitamin D ELISA kit (Immunodiagnostic Systems, cat.

no. AC-57SF1), anti-thyroglobulin (catalog no. ABIN649023,

Antibodies-online), anti-thyroperoxidase ELISA kit (cat. no.

MBS3800854), and anti-tissue transglutaminase ELISA kit (both

MyBioSource, cat. no. MBS7208318). All assays were performed in

strict accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

Chemiluminometric method

The determination of serum PTH levels were

determined using the COBAS E 411 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics), a

fully automated, random-access, multichannel instrument designed

for immunological analysis.

Spectrophotometric methods

Serum biochemical parameters were assessed using

standard enzymatic colorimetric methods. Lipids [total cholesterol

(cat. no. 72291UD00), HDL-C- kit number: 67136UQ10, triglycerides-

kit number:71068UD00), glucose (cat. no. 67921UQ02, creatinine- kit

number: 71560UD00, aspartate transaminase (AST; cat. no. 70068UD00,

alanine transaminase (ALT) - kit number: 72494UD00, C-reactive

protein (CRP)- kit no. 50519Y600, and calcium - kit number:

74372UD00; all Abbott Diagnostics) were measured on the Architect

c8000 Clinical Chemistry Analyzer (Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park,

IL, USA). Assays were performed according to the manufacturer's

instructions and quality control procedures.

Serum phosphorus was determined using the Vitros 5,1

FS Chemistry Analyzer and reagent kit (cat. no. 1203-0398-1506,

Ortho Clinical Diagnostics).

Flow cytometry

Complete blood count was determined using a Sysmex

XN 1000 hematology analyzer (Sysmex Corporation). Flow cytometry

was performed on whole blood samples. Cells were washed twice with

PBS and incubated with blocking buffer (2% FBS in PBS) for 15 min

at 4˚C. Surface markers were detected with directly conjugated

monoclonal antibodies, including CD3-FITC (clone UCHT1; cat. no.

555332; BD Biosciences), CD4-PE (clone RPA-T4; cat. no. 555347; BD

Biosciences), and CD8-APC (cat. no. 555369; BD Biosciences). For

apoptosis analysis, cells were stained with the Annexin V-FITC

Apoptosis Detection kit (cat. no. 556547; BD Biosciences) in

combination with propidium iodide (PI; cat. no. P4864;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). Where secondary detection was required,

biotinylated primary antibodies were visualized using

streptavidin-PE (cat. no. 554061; BD Biosciences). Data acquisition

was performed on a BD FACSCanto II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences),

and results were analyzed using FlowJo software, version 10.8 (Tree

Star Inc.).

ECLIA IGF-1, TSH and fT4 concentrations were

evaluated by ECLIA on a Roche COBAS® e 411 analyzer (Roche

Diagnostics). Commercial reagent kits were provided by

Immunodiagnostic Systems, including the IDS-iSYS IGF-1 assay (cat.

no. IS-3900), IDS-iSYS TSH assay (cat. no. IS-3100), and IDS-iSYS

free T4 assay (cat. no. IS-3300). All assays were performed

according to the manufacturer's instructions.

High-performance liquid chromatography

(HPLC)

HbA1c was measured using the Bio-Rad D-10 Hemoglobin

Testing System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). The separation was

performed on the D-10 cation-exchange cartridge (Bio-Rad

Laboratories, Inc.; cat. no. 220-0101) at a controlled temperature

of 25˚C. Whole blood samples (5 µl) were injected. The mobile phase

consisted of two buffers (Buffer A: phosphate buffer, pH 6.5;

Buffer B: phosphate buffer with increased ionic strength). The

system was operated at a flow rate of 1.5 ml/min with a programmed

gradient increase of Buffer B according to the manufacturer's

protocol. An internal calibrator and quality control material

(Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; cat. no. 220-0102 and 220-0103) were

included, and all procedures were carried out strictly according to

the manufacturer's instructions. β-cell function and insulin

resistance were evaluated using the homeostasis model assessment

indices (HOMA-B and HOMA-IR). HOMA-B was calculated as [20 x

fasting insulin [µU/ml])/(fasting glucose [mmol/L] - 3.5), and

HOMA-IR as (fasting insulin [µU/ml] x fasting glucose

[mmol/L])/22.5, according to Matthews et al (48)

Microbiota analysis

Stool samples were gathered during hospitalization

or at home using a standardized procedure that involved antiseptic

handling, collection in sterile tubes (without culture media) and

immediate freezing at -20˚C. Subsequently, fecal DNA was extracted

utilizing the PureLink Microbiome Purification kit (cat. Number

A29790, Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) following the

manufacturer's instructions. The concentration of DNA was assessed

using a Qubit 4 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). DNA

samples were diluted in DNase-free water to a concentration of 3

ng/µl. Quantitative PCR was performed to determine the relative

abundance of intestinal microorganisms in stool DNA isolated from

both patients with T1DM and healthy controls, using a ViiA7© Fast

Real-Time instrument (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Bacterial or fungal group-specific primers (16S and 18S

rRNA, respectively; Table I) were

used at their designated annealing temperatures. For all other

primers, each set was designed to target the 16S rRNA gene, which

is used as a molecular marker for bacterial identification and

quantification (49). The 16S rRNA

gene contains both highly conserved regions, enabling the design of

universal primers, and variable regions, allowing species-level

discrimination. The control was18S rRN) gene, which serves as a

conserved and widely used molecular marker for fungi. These primers

were designed to recognize a broad range of clinically and

environmentally relevant yeasts, with specificity toward

Candida and Saccharomyces spp. The primers were

previously described in Trandafir et al 2024, validated for

specificity toward the bacterial taxa of interest, ensuring

accurate amplification and minimizing off-target effects (49). Each PCR reaction comprised 2.5 nM

forward and reverse primers, 9 ng DNA and 2X SYBR Green Master Mix

(Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Negative

controls were samples without DNA templates. Thermocycling

conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at 95˚C for 5 min,

followed by 40 cycles of 95˚C for 10 sec, 60˚C for 30 sec and 72˚C

for 1 sec. Universal 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA primers were used for

normalization and relative abundance of bacterial abundance was

calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (50,51).

| Table ISequences of the primers. |

Table I

Sequences of the primers.

| Target | Forward primer

(5'→3') | Reverse primer

(5'→3') | Target gene |

|---|

|

Eubacteria |

ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAGT |

ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGGC | 16S rDNA |

| Bacteroides

spp. | CCTACGATGGATAGGGGT

T |

CACGCTACTTGGCTGGTTCAG | 16S rDNA |

|

Butyricicoccus spp. |

ACCTGAAGAATAAGCTCC |

GATAACGCTTGCTCCCTACGT | 16S rDNA |

| Gamma

proteobacteria |

GCTAACGCATTAAGTACCCCG |

GCCATGCAGCACCTGTCT | 16S rDNA |

| Akkermansia

muciniphila |

GCGTAGGCTGTTTCGTAAGTC GTGTGTGAAAG |

GAGTGTTCCCGATATCTACGC ATTTCA | 16S rDNA |

|

Lactobacillus spp. |

ACGAGTAGGGAAATCTTCCA |

CACCGCTACACATGGAG | 16S rDNA |

| Clostridium

leptum |

GCACAAGCAGTGGAGT |

CTTCCTCCGTTTTGTCAA | 16S rDNA |

| Clostridium

coccoides | GACGCCGCGTGAAGG

A |

AGCCCCAGCCTTTCACATC | 16S rDNA |

| Faecalibacterium

prausnitzii |

CCCTTCAGTGCCGCAGT |

GTCGCAGGATGTCAAGAC | 16S rDNA |

| rRNA 18S universal

primers |

ATTGGAGGGCAAGTCTGGTG |

CCGATCCCTAGTCGGCATAG | rRNA 18S |

|

Saccharomyces spp. |

AGGAGTGCGGTTCTTTG |

TACTTACCGAGGCAAGCTACA | rRNA 18S |

| Candida

spp. |

TTTATCAACTTGTCACACCAGA |

ATCCCGCCTTACCACTACCG | rRNA 18S |

Metabolite analysis

Fecal content pellets (0.2 g) were suspended in 1 ml

sterile saline solution and incubated at room temperature for 2

min. Subsequently, the sample was vigorously shaken for 4 min to

create a slurry. After centrifugation at 1,790 x g for 1 h at 4˚C,

the supernatant was collected and subjected to further

centrifugation at 28,600 x g for 30 min at 4˚C.

Fecal content pellets (0.2 g) were suspended in 1 ml

sterile saline solution and incubated at room temperature for 2

min. Subsequently, the sample was vigorously shaken for 4 min to

create a slurry. The resulting supernatant was transferred to a new

tube and filtered using a minisart-GF filter membrane (Sartorius

AG) with a 1 ml sterile plastic syringe. Finally, another

filtration step was performed using a Whatman-25 mmGD/X0 filter

(Merck Millipore) and a 1 ml sterile plastic syringe. Metabolite

levels (including butyrate, acetate, propionate, taurine, succinate

and lactate) were determined using commercial kits following the

manufacturer's instructions (Abbexa, cat. no. abx258338 for

butyrate quantification and Sigma-Aldrich for the other

metabolites- Cat. Number MAK355, MAK184, MAK065, and MAK086).

Optical densities were measured using a spectrophotometer at 455 nm

(Mulsiskan FC, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and converted to

µg/g feces.

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM or SD and

were analyzed using the GraphPad Prism 9.0 software (Dotmatics). A

total of three independent repeats were performed. Power analysis

was initially performed with a set power (1) of 0.90 and 0.05 for two groups (Control

and T1DM) tested using difference in means and SD as parameters.

Standardized statistical test methods were used to analyze the

results of demography and laboratory tests. The analysis was

performed by a normality test (P<0.05 was considered to be

normal and homogeneous) followed by parametric testing (unpaired

t-test) and Welch's post hoc correction. Spearman correlation

analysis of the association between proinflammatory taxa and early

onset T1DM, high-level onset glycaemia and ketoacidosis, insulin

dose, inflammation, thyroid autoimmunity, IGF-1 and other clinical

parameters regarding growth was performed using SPSS Windows v.

17.0 (SPSS, Inc.). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Among the 31 patients, the ratio male: female was

1.11 and the mean BMI was 17.48 kg/m2. The mean age of

the onset of the disease was 9.0±0.5 years and the mean glycaemia

was 350±98 mg/dl (Table II). The

vaginal: caesarian birth ratio was 0.36, (13/31) and 10/31 patients

with T1DM had a family history of autoimmune disease.

| Table IIBiochemical and immunological

parameters. |

Table II

Biochemical and immunological

parameters.

| Parameter | Mean | SEM | Std. Deviation | Median | Normal values |

|---|

| Leukocytes,

x103/µl | 6.68 | 0.40 | 2.22 | 6.15 | 4.60-15.50 |

| Neutrophils,

x103/µl | 3.37 | 0.30 | 1.69 | 2.95 | 1.50-7.00 |

| Lymphocytes,

x103/µl | 2.62 | 0.19 | 1.09 | 2.31 | 1.50-10.50 |

| Hemoglobin,

g/dl | 13.42 | 0.21 | 1.15 | 13.00 | 11.00-15.30 |

| CRP, mg/dl | 3.58 | 2.11 | 8.71 | 0.55 | <0.50 |

| ALT, U/l | 19.29 | 1.77 | 9.84 | 16.00 | 13.00-26.00 |

| AST, U/l | 23.45 | 1.28 | 7.12 | 22.00 | 8.00-25.00 |

| Creatinine,

mg/dl | 0.66 | 0.03 | 0.15 | 0.63 | 0.57-0.86 |

| Total cholesterol

(mg/dl) | 172.23 | 8.16 | 44.70 | 164.50 | 140.00-200.00 |

| Triglycerides

(mg/dl) | 53.23 | 3.31 | 18.15 | 51.50 | >40.00 |

| HDL-cholesterol,

mg/dl | 63.48 | 2.45 | 13.64 | 61.00 | <130.00 |

| LDL-cholesterol,

mg/dl | 102.90 | 5.75 | 32.00 | 96.40 | 35.00-150.00 |

| Anti-thyroglobulin

antibodies, IU/ml | 60.87 | 29.48 | 161.44 | 10.00 | 1.00-16.00 |

| Anti-thyroid

peroxidase antibodies (IU/ml) | 51.66 | 31.90 | 177.60 | 9.00 | <20.00 |

|

Anti-transglutaminase antibodies,

IU/ml | 0.91 | 0.40 | 1.90 | 0.40 | <10.00 |

| TSH, µIU/ml | 2.507 | 0.22 | 1.18 | 2.36 | 0.30-3.60 |

| Free T4, ng/dl | 1.185 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 1.20 | 0.8-1.48 |

| 250H vitamin D,

ng/ml | 28.16 | 2.10 | 11.49 | 24.28 | >30.00 |

| Total calcium,

mg/dl | 9.57 | 0.07 | 0.37 | 9.60 | 8.40-10.20 |

| Phosphorus,

mg/dl | 4.83 | 0.19 | 0.65 | 4.85 | 2.50-4.50 |

| PTH, pg/ml | 31.36 | 2.52 | 13.31 | 27.89 | 15.00-65.00 |

| Insulin, IU/24

h/kg | 19.23 | 4.08 | 21.58 | 11.00 | 0.30-1.00 |

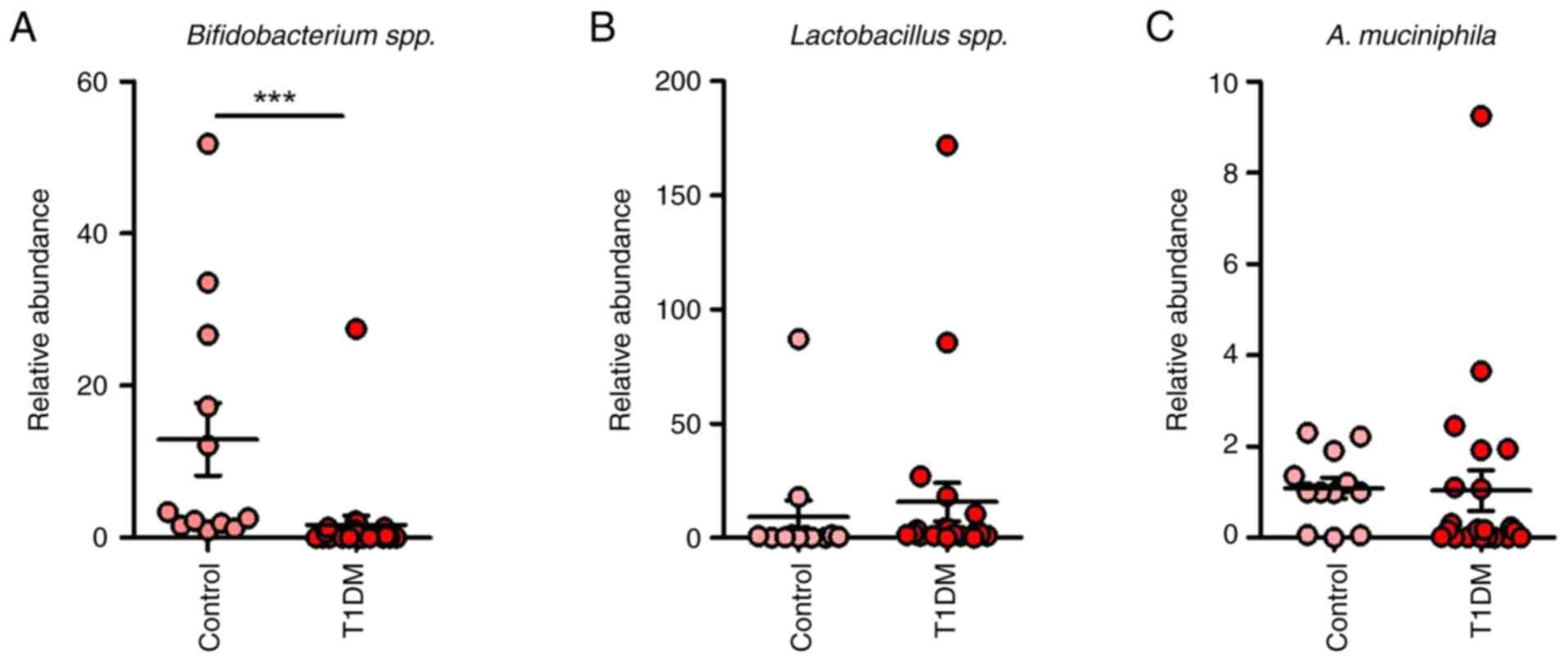

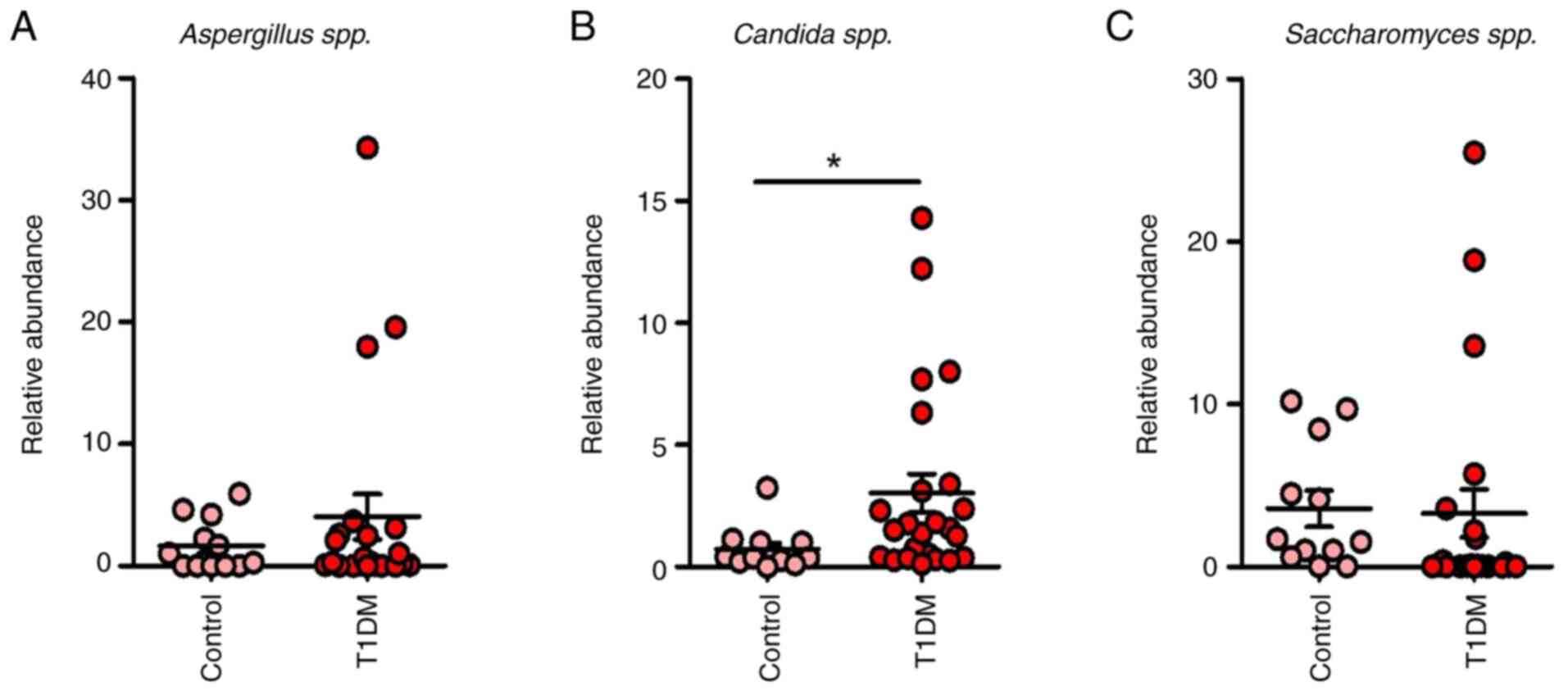

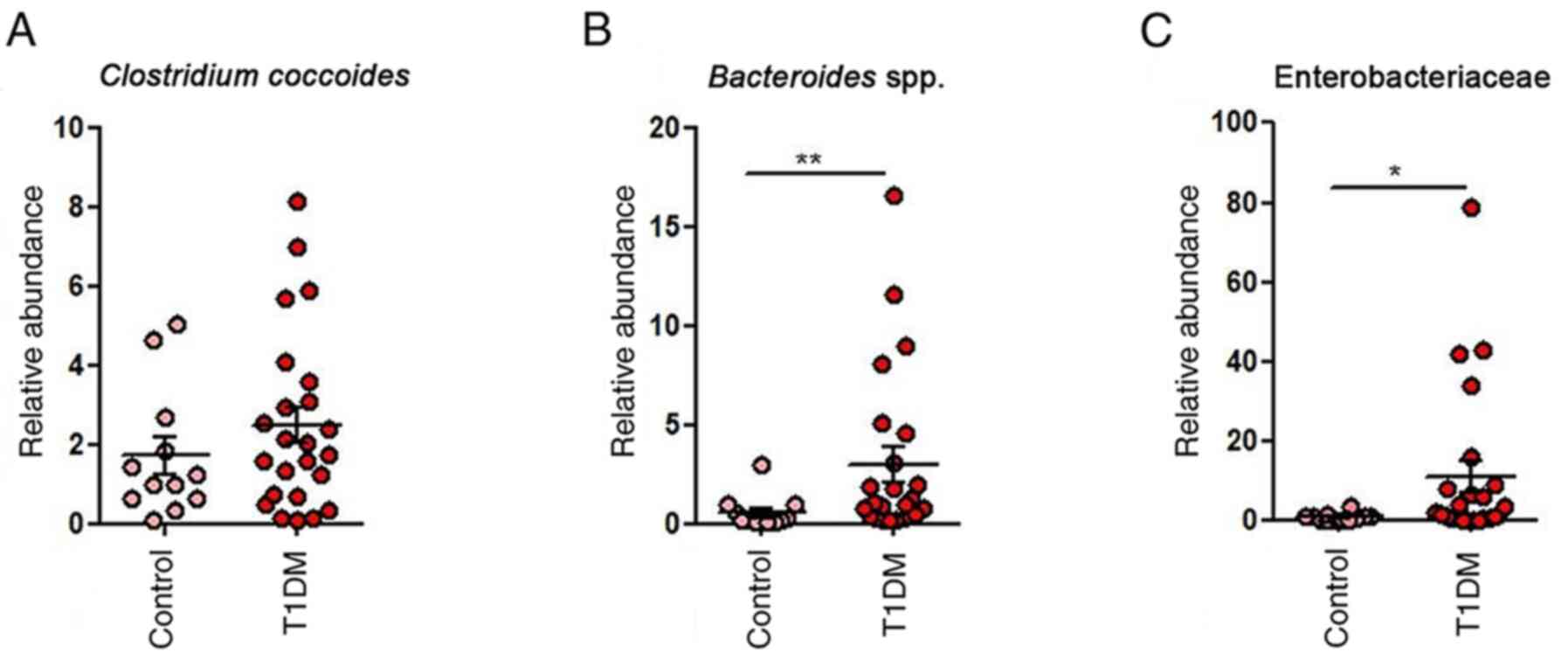

In the T1DM group, dysbiosis was evident,

characterized by an overabundance of detrimental bacteria such as

Clostridium coccoides, Faecalibacterium,

Bacteroides and Enterobacteriaceae, as well as fungi

including Candida, Saccharomyces and Aspergillus

spp., in contrast to the healthy control group (Fig. 1, Fig.

2 and Fig. 3). Furthermore, a

notable decrease in Bifidobacterium spp. and elevated

presence of A. muciniphila within the beneficial taxa were

observed among patients with T1DM compared with the healthy control

group (Figs. 1 and 4).

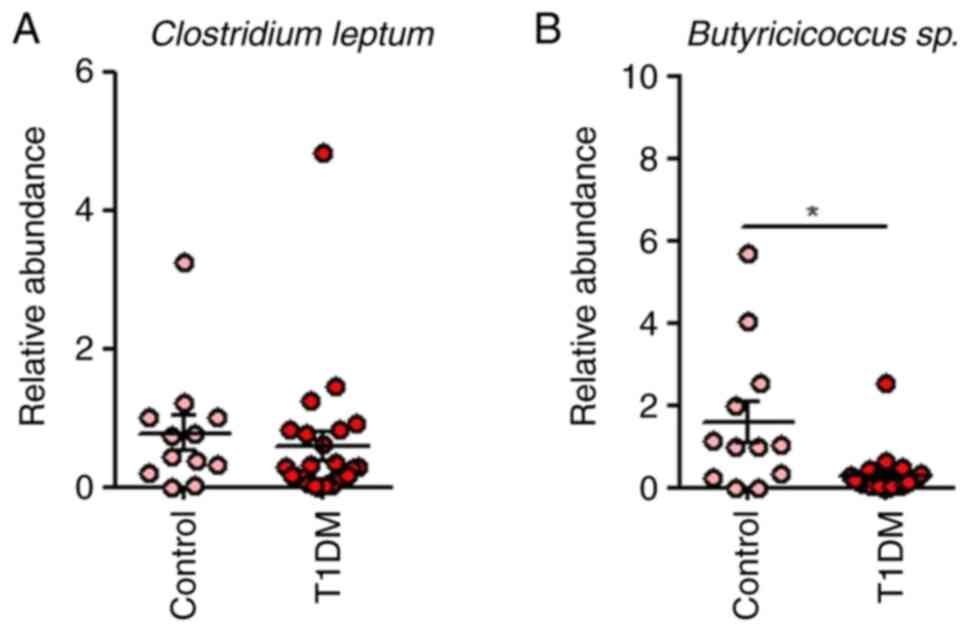

A decrease in butyrate-producing bacteria was

observed in the T1DM group with dysbiosis with increased abundance

of Enterobacteriaceae in T1DM (P=0.0193; Fig. 3). This pattern underscores the

alteration in the microbial composition associated with T1DM,

suggesting a potential role of gut microbiota dysregulation in the

pathogenesis of the disease.

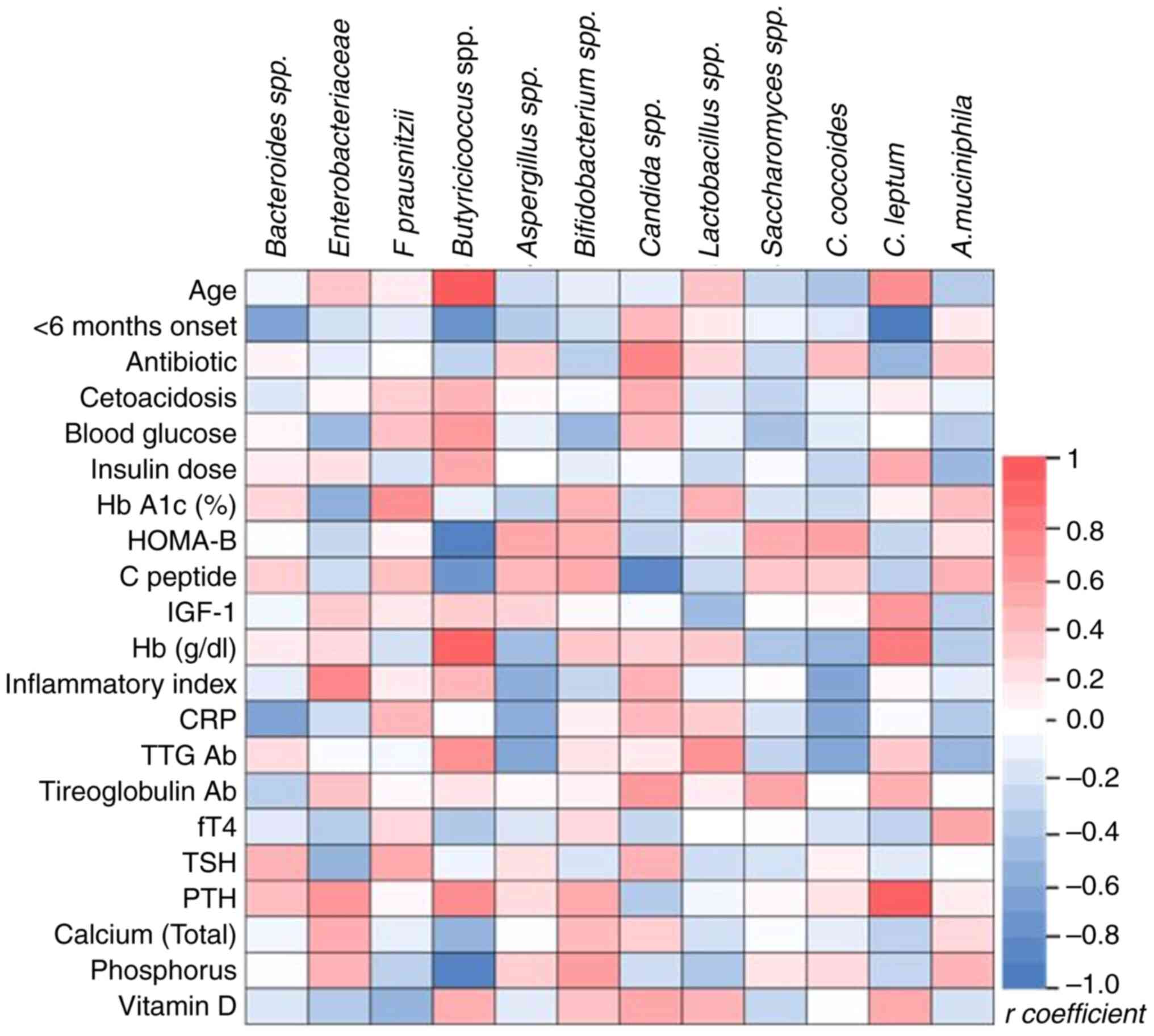

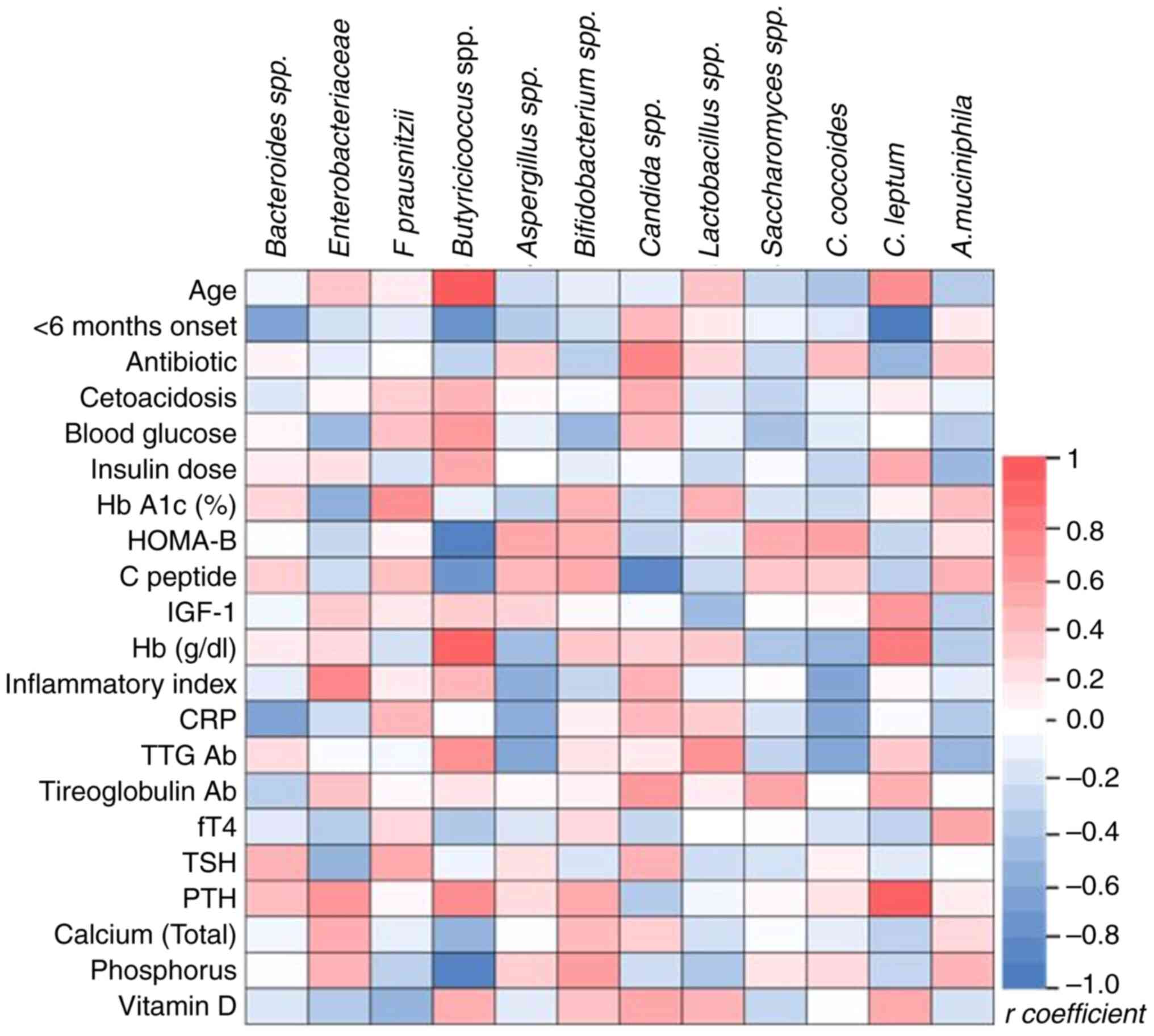

Correlation analysis identified significant

correlations between specific gut microbiota taxa and clinical

parameters in pediatric T1DM (Fig.

5). The relative abundance of Butyricicoccus was

positively associated with younger age at onset (r=0.6276,

P=0.0018) but negatively linked to onset within 6 months (r=-0.517,

P=0.0164), pancreatic β cell reserve (HOMA-B, r=-0.5962, P=0.0034),

C-peptide (r=-0.5005, P=0.0344) and phosphorus levels (r=-0.5937,

P=0.0036). Bacteroides relative abundance showed negative

correlations with early-stage diabetes (r=-0.4431, P=0.0442) and

inflammation (indicated by CRP levels; r=-0.4331; P=0.0498). The

relative abundance of Clostridium leptum was inversely

associated with recent diagnosis (r=-0.6278, P=0.0023) but

positively correlated with hemoglobin (r=0.4765, P=0.025) and PTH

levels (r=0.6047, P=0.0029). Antibiotic intake was correlated

positively with the relative abundance of Candida albicans

(r=0.4431, P=0.0442), while the inflammatory index was linked

positively to Enterobacteriaceae (r=0.4331, P=0.0441) and

negatively with C. coccoides (r=-0.4241, P=0.0492).

Hemoglobin was also positively associated with

Butyricicoccus (r=0.5857, P =0.0042), highlighting potential

microbiota roles in T1DM progression and inflammation.

| Figure 5Spearman correlation coefficients

between clinical parameters (and relative abundance of bacterial

taxa in the microbiome. Red, positive correlation; blue, negative

correlations; intensity of color corresponds to the magnitude of

the correlation. HbA1C, Hemoglobin A1c (glycated hemoglobin);

HOMA-B, Homeostatic Model Assessment of β-cell function; IGF,

Insulin-like Growth Factor; CRP, C-reactive Protein; TTG Ab, Tissue

Transglutaminase Antibodies; fT4, Free Thyroxine; TSH,

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone; PTH, Parathyroid Hormone. |

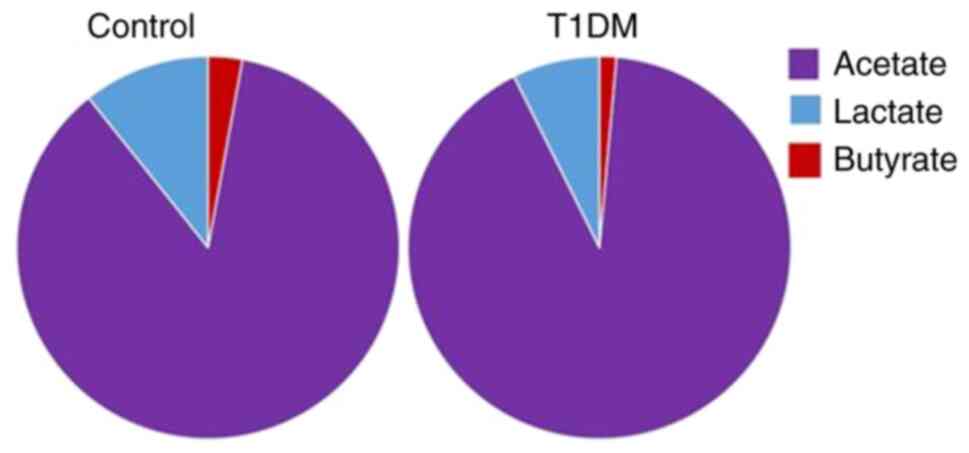

The microbiota findings were compared with the

metabolite levels in stool samples from both patients with T1DM and

healthy controls (Fig. 6). Patients

with T1DM exhibited notably decreased levels of butyrate and

lactate compared with the healthy controls. Conversely, acetate

levels were higher in the T1DM cohort.

Discussion

The present retrospective case-control study was

conducted in Romania between January 2019 and December 2021,

involving 31 children. The timeline of analysis and manuscript

preparation was substantially affected by the coronavirus Disease

2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Institutional priorities during this

period were redirected toward pandemic-related clinical and

research activities, and access to laboratories and clinical

facilities was intermittently restricted. These factors contributed

to an extended delay in data processing, analysis, and publication.

Nevertheless, all study data were securely stored, curated, and

analyzed in accordance with the approved protocol, ensuring the

integrity and validity of the findings.

The role of microbiota in T1DM has garnered

increasing attention and investigation: Previous studies have

linked specific bacterial taxa such as Bacteroides,

Bifidobacterium and Ruminococcus with heightened

cytokine levels, pancreatic inflammation, autoimmune reaction and

the onset of T1DM (1,2,4). The

present study demonstrated dysbiosis characterized by an

overabundance of proinflammatory bacteria (including C.

coccoides, Faecalibacterium, Bacteroides and

Enterobacteriaceae) and fungi in pediatric patients with

T1DM from Romania, in comparison with healthy controls.

Contrary to the healthy control group, patients with

T1DM exhibited a microbiota predominantly composed of

Bacteroides taxa, despite the presence of relatively

abundant protective bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus spp., and A. muciniphila. Notably,

earlier onset and more severe presentation of T1DM were positively

associated with specific proinflammatory bacterial species,

including Bacteroides and Butyricicoccus spp., in

alignment with the literature (16,52).

C. leptum is another taxon correlated with a younger age at

onset and although its role may vary depending on the context, host

health, and microbiota composition its altered abundance may

contribute to disease susceptibility and progression (53). In gut dysbiosis, its abundance may

shift, and interactions with other microbial taxa could influence

systemic inflammation indirectly. However, it is primarily reported

as a contributor to a balanced, healthy gut environment rather than

as a proinflammatory agent (21-23).

Studies conducted in a Romanian center on patients

with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) or metabolic syndrome have

revealed similar microbial compositions, particularly the presence

of Enterobacteriaceae, which is correlated with inflammation

and other chronic diseases (53,54).

The Spearman correlation analysis demonstrated

associations between specific microbial taxa and clinical markers,

including those of inflammation, metabolic status and endocrine

function, suggesting a potential role of the gut microbiome in

modulating health outcomes in the context of metabolic

disorder.

The presence of proinflammatory bacteria such as

Enterobacteriaceae showed a positive association with the

systemic inflammatory index; relative abundance of

anti-inflammatory bacteria as Bacteroides and C.

coccoides showed a negative association with CRP levels and

with the systemic inflammatory index (23-25).

Antibiotic use during acute infections in the 2

months preceding diagnosis in children with T1DM may have perturbed

the microbiota, resulting in an overabundance of Candida spp

(45,53,54).

Additionally, T1DM is associated with an increased susceptibility

to recurrent infections and alterations in the immune system within

the first year of the disease, as well as lower complement

component 4) levels and a higher helper/suppressor T lymphocyte

ratio (55,56). These findings are consistent with

those reported by other authors (55-57).

Assessing growth and bone density is key in children

with T1DM and T2DM, given the link between impaired bone health and

dysbiosis characterized by an elevated presence of

Lactobacilli (58). In the

present study, dysbiosis impacted calcium-phosphorous metabolism;

phosphorus levels negatively correlated with Butyricicoccus

and PTH levels were positively correlated with C. leptum

(56,59,60).

The role of Bacteroides in intestinal

homeostasis, particularly in T1DM, is complex and

context-dependent. Bacteroides spp. exhibit both

pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory properties, depending on

species, strain and host factors. On one hand, certain

Bacteroides strains (such as B. fragilis, producing

polysaccharide A) have been shown to exert anti-inflammatory

effects by promoting regulatory T cell response and maintaining

mucosal barrier integrity (61,62) On

the other hand, other species or imbalances in Bacteroides

abundance are associated with pro-inflammatory states, including

increased intestinal permeability and heightened immune activation,

which are relevant to the pathogenesis of T1DM (11).

Here, the enrichment of Bacteroides in

patients with T1DM may reflect a shift toward a dysbiotic profile

that contributes to inflammation and autoimmune activation.

However, not all Bacteroides are pathogenic, and their

impact may vary with microbial context, age and diet. Future

strain-level or functional metagenomic analyses may clarify the

specific contributions of Bacteroides in the T1DM gut

microbiome.

Patients with T1DM exhibited notably decreased

levels of butyrate and lactate compared with healthy controls, with

higher acetate levels in the T1DM cohort, diverging from other

studies that found decreased plasma levels of acetate and

propionate and similar levels of plasma butyrate in controls

compared with patients with T1DM (11,24).

Measurements of SCFA levels (butyrate, lactate and acetate) were

obtained from fecal samples, which primarily reflect microbial

fermentation activity in the colon and the unabsorbed SCFA

fraction. This contrasts with other studies reporting SCFA

concentrations in plasma, which are influenced not only by gut

microbial production but also by host absorption efficiency,

hepatic metabolism and systemic circulation dynamics (62,63).

Therefore, direct comparisons between fecal and plasma SCFA levels

must be interpreted with caution. The increase in fecal acetate

alongside decreased butyrate and lactate in the present T1DM cohort

may indicate altered microbial metabolism or impaired SCFA

absorption in these patients, rather than a contradiction of plasma

findings reported in previous studies (63,64).

The present study demonstrated the role of gut

microbiota in pediatric patients with T1DM. It highlighted

dysbiosis characterized by an overabundance of proinflammatory

bacteria such as Bacteroides, Enterobacteriaceae and

C. coccoides, alongside fungi such as Candida spp, in

patients with T1DM compared with healthy controls. This aligns with

existing research, underscoring the association of these taxa with

inflammation, autoimmune reaction and metabolic imbalances

(11,14). The study also demonstrated

correlations between microbial taxa and clinical markers, such as

the systemic inflammatory index, CRP levels and calcium-phosphorous

metabolism, emphasizing the microbiota influence on systemic

inflammation, bone health and disease progression.

Moreover, the perturbation of microbiota following

antibiotic use and the increased prevalence of recurrent infections

in patients with T1DM highlight the dynamic interactions between

external factors, immune function and the gut microbiome. By

revealing specific microbiota compositions associated with earlier

disease onset, severity and metabolic markers, the present study

demonstrated how gut dysbiosis impacts T1DM pathophysiology. These

findings may facilitate research into microbiota-targeted

interventions, such as dietary modification or probiotic therapy,

to improve disease management and patient outcomes in T1DM.

However, the present study had limitations,

including the heterogeneous composition of the study group, its

retrospective nature with a small patient cohort and the

commencement of enrollment a few months before the onset of the

COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown, primarily involving an urban

population. Additionally, the microbiota study excluded patients

who received antibiotics following infections, particularly those

with diabetic ketoacidosis.

Future research directions include proteomics and

metabolomics profiling to evaluate functional changes in the

microbiome of patients with T1DM. Longitudinal studies observing

disease onset and progression in patients with dysbiosis are also

warranted. Furthermore, the associations between dysbiosis and

other autoimmune diseases (such as Hashimoto's thyroiditis and

celiac disease) need to be investigated with regard to the

correlation between antibody positivity and clinical disease

onset.

The present data may be used to estimate the risk of

developing T1DM and other autoimmune diseases in the siblings of

these patients. Risk calculators that consider specific genetic

traits (human leukocyte antigen haplotypes), antibody presence and

family history of the disease may predict the likelihood of

developing diabetes before symptoms manifest. Early intervention,

when a reasonable number of insulin-producing β cells are present

in the pancreas, may positively influence immune responses by

modifying gut microbiota, potentially slowing disease progression

and improving outcomes.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Executive Agency for

Higher Education, Research, Development and Innovation Funding

(project ID no. PN-III-P1-1.1-PD-2019-0499, grant no.

224/2021).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are not

publicly available due to participant privacy but may be requested

from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

AAI, SF and GGP conceived the study. AAI and GGP

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. SI designed the

methodology. TP analyzed data. AAI and GGP performed experiments.

AAI wrote and edited the manuscript, constructed figures and

supervised the study. GGP edited the manuscript. SF and GGP

acquired funding. All authors have read and approved the final

manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was conducted according to the

guidelines of The Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the

Ethics Committee of University of Bucharest (protocol code CEC reg.

no. 235/9.10.2019) and the Institutional Review Board of the Elias

Hospital (approval no. 1695, 12.03.2019; both Bucharest, Romania).

Informed consent was obtained from the parents of patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Ogle GD, Wang F, Haynes A, Gregory GA,

King TW, Deng K, Dabelea D, James S, Jenkins AJ, Li X, et al:

Global type 1 diabetes prevalence, incidence, and mortality

estimates 2025: Results from the International Diabetes Federation

Atlas, 11th Edition, and the T1D Index Version 3.0. Diabetes Res

Clin Pract. 225(112277)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Dedrick S, Sundaresh B, Huang Q, Brady C,

Yoo T, Cronin C, Rudnicki C, Flood M, Momeni B, Ludvigsson J and

Altindis E: The role of gut microbiota and environmental factors in

type 1 diabetes pathogenesis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

11(78)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Penders J, Thijs C, Vink C, Stelma FF,

Snijders B, Kummeling I, Van den Brandt PA and Stobberingh EE:

Factors influencing the composition of the intestinal microbiota in

early infancy. Pediatrics. 118:511–521. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Gradisteanu Pircalabioru G, Corcionivoschi

N, Gundogdu O, Chifiriuc MC, Marutescu LG, Ispas B and Savu O:

Dysbiosis in the development of type I diabetes and associated

complications: From mechanisms to targeted gut microbes

manipulation therapies. Int J Mol Sci. 22(2763)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Rampanelli E and Nieuwdorp M: Gut

microbiome in type 1 diabetes: The immunological perspective.

Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 19:93–109. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Abuqwider J, Corrado A, Scidà G, Lupoli R,

Costabile G, Mauriello G and Bozzetto L: Gut microbiome and blood

glucose control in type 1 diabetes: A systematic review. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 14(1265696)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wen L, Ley RE, Volchkov PY, Stranges PB,

Avanesyan L, Stonebraker AC, Hu C, Wong FS, Szot GL, Bluestone JA,

et al: Innate immunity and intestinal microbiota in the development

of type 1 diabetes. Nature. 455:1109–1113. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Markle JG, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S,

Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, von Bergen M, McCoy KD,

Macpherson AJ and Danska JS: Sex differences in the gut microbiome

drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science.

339:1084–1088. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hansen CH, Krych L, Nielsen DS, Vogensen

FK, Hansen LH, Sørensen SJ, Buschard K and Hansen AK: Early life

treatment with vancomycin propagates Akkermansia muciniphila and

reduces diabetes incidence in the NOD mouse. Diabetologia.

55:2285–2294. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Maffeis C, Martina A, Corradi M, Quarella

S, Nori N, Torriani S, Plebani M, Contreas G and Felis GE:

Association between intestinal permeability and faecal microbiota

composition in Italian children with beta cell autoimmunity at risk

for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res Rev. 32:700–709.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kostic AD, Gevers D, Siljander H, Vatanen

T, Hyötyläinen T, Hämäläinen AM, Peet A, Tillmann V, Pöhö P,

Mattila I, et al: The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome

in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host

Microbe. 17:260–273. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ziegler AG, Hoffmann GF, Hasford J,

Larsson HE, Danne T, Berner R, Penno M, Koralova A, Dunne J and

Bonifacio E: Screening for asymptomatic β-cell autoimmunity in

young children. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 3:288–290.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Vaarala O: Gut microbiota and type 1

diabetes. Rev Diabet Stud. 9:251–259. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Vatanen T, Franzosa EA, Schwager R,

Tripathi S, Arthur TD, Vehik K, Lernmark Å, Hagopian WA, Rewers MJ,

She JX, et al: The human gut microbiome in early-onset type 1

diabetes from the TEDDY study. Nature. 562:589–594. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Bäckhed F, Ley RE, Sonnenburg JL, Peterson

DA and Gordon JI: Host-bacterial mutualism in the human intestine.

Science. 307:1915–1920. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Murri M, Leiva I, Gomez-Zumaquero JM,

Tinahones FJ, Cardona F, Soriguer F and Queipo-Ortuño MI: Gut

microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in

healthy children: A case-control study. BMC Med.

11(46)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Arts RJW, Joosten LAB and Netea MG: The

potential role of trained immunity in autoimmune and

autoinflammatory disorders. Front Immunol. 9(298)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Marchesi JR and Ravel J: The vocabulary of

microbiome research: A proposal. Microbiome. 3(31)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Jung TH, Han KS, Park JH and Hwang HJ:

Butyrate modulates mucin secretion and bacterial adherence in LoVo

cells via MAPK signaling. PLoS One. 17(e0269872)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Vatanen T, de Beaufort C, Marcovecchio ML,

Overbergh L, Brunak S, Peakman M, Mathieu C and Knip M: INNODIA

consortium. Gut microbiome shifts in people with type 1 diabetes

are associated with glycaemic control: An INNODIA study.

Diabetologia. 67:1930–1942. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Flint HJ, Scott KP, Duncan SH, Louis P and

Forano E: Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the

gut. Gut Microbes. 3:289–306. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hague A, Butt AJ and Paraskeva C: The role

of butyrate in human colonic epithelial cells: An energy source or

inducer of differentiation and apoptosis? Proc Nutr Soc.

55:937–943. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, Petito V and

Gasbarrini A: Commensal Clostridia: Leading players in the

maintenance of gut homeostasis. Gut Pathog. 5(23)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Leiva-Gea I, Sánchez-Alcoholado L,

Martín-Tejedor B, Castellano-Castillo D, Moreno-Indias I,

Urda-Cardona A, Tinahones FJ, Fernández-García JC and Queipo-Ortuño

MI: Gut microbiota differs in composition and functionality between

children with type 1 Diabetes and MODY2 and healthy control

subjects: A case-control study. Diabetes Care. 41:2385–2395.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Brown CT, Davis-Richardson A, Giongo A,

Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N, Casella G, Drew JC, Ilonen J, Knip

M, et al: Gut microbiome metagenomics analysis suggests a

functional model for the development of autoimmunity for type 1

diabetes. PLoS One. 6(e25792)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Valladares R, Sankar D, Li N, Williams E,

Lai KK, Abdelgeliel AS, Gonzalez CF, Wasserfall CH, Larkin J,

Schatz D, et al: Lactobacillus johnsonii N6.2 mitigates the

development of type 1 diabetes in BB-DP rats. PLoS One.

5(e10507)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Human Microbiome Project Consortium.

Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human microbiome.

Nature. 486:207–214. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Hypponen E: Vitamin D and increasing

incidence of type 1 diabetes-evidence for an association? Diabetes

Obes Metab. 12:737–743. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chia LW, Mank M, Blijenberg B, Aalvink S,

Bongers RS, Stahl B, Knol J and Belzer C: Bacteroides

thetaiotaomicron fosters the growth of butyrate-producing

Anaerostipes caccae in the presence of lactose and total human milk

carbohydrates. Microorganisms. 8(1513)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zipitis CS and Akobeng AK: Vitamin D

supplementation in early childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 93:512–517.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Karvonen M, Viik-Kajander M, Moltchanova

E, Libman I, LaPorte R and Tuomilehto J: Incidence of childhood

type 1 diabetes worldwide. Diabetes Mondiale (DiaMond) Project

Group. Diabetes Care. 23:1516–1526. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Pozzilli P, Manfrini S, Crinò A, Picardi

A, Leomanni C, Cherubini V, Valente L, Khazrai M and Visalli N:

IMDIAB group. Low levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and

1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in patients with newly diagnosed type 1

diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 37:680–683. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Borkar VV, Devidayal Verma S and Bhalla

AK: Low levels of vitamin D in North Indian children with newly

diagnosed type 1 diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes. 11:345–50.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hagopian WA, Erlich H, Lernmark Å, Rewers

M, Ziegler AG, Simell O, Akolkar B, Vogt R Jr, Blair A, Ilonen J,

et al: The environmental determinants of diabetes in the young

(TEDDY): Genetic criteria and international diabetes risk screening

of 421,000 infants. Pediatr Diabetes. 12:733–743. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Lönnrot M, Lynch KF, Elding Larsson H,

Lernmark Å, Rewers MJ, Törn C, Burkhardt BR, Briese T, Hagopian WA,

She JX, et al: TEDDY study group: Respiratory infections are

temporally associated with initiation of type 1 diabetes

autoimmunity: The TEDDY study. Diabetologia. 60:1931–1940.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Rewers M and Ludvigsson J: Environmental

risk factors for type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 387:2340–2348.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Vlad A, Serban V, Green A, Möller S, Vlad

M, Timar B and Sima A: ONROCAD Study Group. Time trends, regional

variability and seasonality regarding the incidence of type 1

diabetes mellitus in Romanian children aged 0-14 years, between

1996 and 2015. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 10:92–99.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ionescu-Tîrgoviște C, Guja C, Călin A and

Moţa M: An increasing trend in the incidence of type 1 diabetes

mellitus in children aged 0-14 years in Romania-ten years

(1988-1997) EURODIAB study experience. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab.

17:983–991. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Gyürüs EK, Patterson C and Soltész G:

Hungarian Childhood Diabetes Epidemiology Group. Twenty-one years

of prospective incidence of childhood type 1 diabetes in

Hungary-the rising trend continues (or peaks and highlands?).

Pediatr Diabetes. 13:21–25. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Jarosz-Chobot P, Polańska J, Szadkowska A,

Kretowski A, Bandurska-Stankiewicz E, Ciechanowska M, Deja G,

Mysliwiec M, Peczynska J, Rutkowska J, et al: Rapid increase in the

incidence of type 1 diabetes in Polish children from 1989 to. 2004,

and predictions for 2010 to 2025. Diabetologia. 54:508–515.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Usher-Smith JA, Thompson M, Ercole A and

Walter FM: Variation between countries in the frequency of diabetic

ketoacidosis at first presentation of type 1 diabetes in children:

A systematic review. Diabetologia. 55:2878–2894. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Triolo TM, Armstrong TK, McFann K, Yu L,

Rewers MJ, Klingensmith GJ, Eisenbarth GS and Barker JM: Additional

autoimmune disease found in 33% of patients at type 1 diabetes

onset. Diabetes Care. 34:1211–1213. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Akhtadze E, Cilio CM, Hansen I, Gerdes AM,

Mortensen HB, Pociot F and Nerup J: Distribution of autoimmune

diseases in Danish children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes

mellitus. Horm Res. 65:193–198. 2006.

|

|

44

|

ElSayed NA, Aleppo G, Aroda VR, Bannuru

RR, Brown FM, Bruemmer D, Collins BS, Hilliard ME, Isaacs D,

Johnson EL, et al: 2. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes:

Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2023. Diabetes Care. 46

(Suppl 1):S19–S40. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

de Groot PF, Belzer C, Levels JH, Aalvink

S, Boot F, Holleman F, Van Raalte DH, Scheithauer TP, Simsek S,

Schaap FG, et al: Distinct fecal and oral microbiota composition in

human type 1 diabetes, an observational study. PLoS One.

12(e0188475)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Thomson G, Valdes AM, Noble JA, Kockum I,

Grote MN, Najman J, Erlich HA, Cucca F, Pugliese A, Steenkiste A,

et al: Relative predispositional effects of HLA class II DRB1-DQB1

haplotypes genotypes on type 1 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Tissue

Antigens. 70:110–127. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Emmanuel M and Bokor BR: Tanner Stages.

2022 Dec 11. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island,

FL, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470280/.

|

|

48

|

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS,

Naylor BA, Treacher DF and Turner RC: Homeostasis model assessment:

Insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose

and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 28:412–419.

1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Trandafir M, Pircalabioru GG and Savu O:

Microbiota analysis in individuals with type two diabetes mellitus

and end-stage renal disease: A pilot study. Exp Ther Med.

27(211)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Srinivasan R, Karaoz U, Volegova M,

MacKichan J, Kato-Maeda M, Miller S, Nadarajan R, Brodie EL and

Lynch SV: Use of 16S rRNA gene for identification of a broad range

of clinically relevant bacterial pathogens. PLoS One.

10(e0117617)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Giongo A, Gano KA, Crabb DB, Mukherjee N,

Novelo LL, Casella G, Drew JC, Ilonen J, Knip M, Hyöty H, et al:

Toward defining the autoimmune microbiome for type 1 diabetes. ISME

J. 5:82–91. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Gradisteanu Pircalabioru G, Chifiriuc MC,

Picu A, Petcu LM, Trandafir M and Savu O: Snapshot into the

type-2-diabetes-associated microbiome of a romanian cohort. Int J

Mol Sci. 23(15023)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Gradisteanu Pircalabioru G, Ilie I, Oprea

L, Picu A, Petcu LM, Burlibasa L, Chifiriuc MC and Musat M:

Microbiome, mycobiome and related metabolites alterations in

patients with metabolic syndrome-a pilot study. Metabolites.

12(218)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Hull CM, Peakman M and Tree TIM:

Regulatory T cell dysfunction in type 1 diabetes: what's broken and

how can we fix it? Diabetologia. 60:1839–1850. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Alnek K, Tagoma A, Metsküla K, Talja I,

Janson H, Mandel M, Vorobjova T, Oras A, Sepp H, Pruul K, et al:

Comparison of immunological and immunogenetic markers in

recent-onset type 1 diabetes among children and adults. Sci Rep.

15(15491)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Mazzoni MB, Roversi M, Maltoni G, Biasucci

G, Berardi A, Tonielli E, Cicognani A and Salardi S: Gualandi.

Recurrent infections in children and adolescents with type 1

diabetes mellitus: A case-control study. BMC Infect Dis.

18(599)2018.

|

|

58

|

Hygum K, Starup-Linde J, Harsløf T,

Vestergaard P and Langdahl BL: Mechanisms in endocrinology:

Diabetes mellitus, a state of low bone turnover-a systematic review

and meta-analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 176:R137–R157. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Knudsen JK, Leutscher P and Sørensen S:

Gut microbiota in bone health and diabetes. Curr Osteoporos Rep.

19:462–479. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Janner M and Saner C: Impact of type 1

diabetes mellitus on bone health in children. Horm Res Paediatr.

95:205–214. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Round JL and Mazmanian SK: Inducible

Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of

the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 107:12204–12209.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Mazmanian SK, Round JL and Kasper DL: A

microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestnal inflammatory disease.

Nature. 453:620–625. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK,

Venema K, Reijngoud DJ and Bakker BM: The role of short-chain fatty

acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota and host energy

metabolism. J Lipid Res. 54:2325–2340. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

de Groot PF, Belzer C, Aydin Ö, Levin E,

Levels JH, Aalvink S, Boot F, Holman R, Reitsma PH, Gerdes VE and

Nieuwdorp M: Distinct fecal and oral microbiota composition in

human type 1 diabetes, an observational study. PLoS ONE.

12(e0188475)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|