1. Introduction

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS), one of the

spondyloarthropathy (SpA) groups, is a type of autoimmune disease

involved in sacroiliac joints and cartilage, eventually causing

spine ankylosis (1,2). It commonly arises in the second decade

of life and varies in symptom by geographic location and sex

(3,4). The progression of inflammation in AS

is associated with bone erosion, abnormal bone formation, and

ankylosis, leading to pain and reduced mobility (5). Additionally, AS is reported to be

accompanied by extra-articular manifestations, including anterior

uveitis, psoriasis, and chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

(6).

Although the pathological mechanisms of AS have not

been fully elucidated, genetic background and environmental factors

have been shown to influence its pathogenesis through complex

interactions (7,8). Among them, human leukocyte antigen B27

(HLA-B27) was the first factor investigated and has the strongest

association with AS (9,10), reflecting prevalence differences due

to race-specific genetic variations (11). In addition, it has been reported

that AS is a complex disease in which autoinflammatory and

autoimmune systems are correlated (1). Aberrant HLA-B27, gut microbiota and

biomechanical stress such as orthograde posture trigger

inflammation in collaboration with natural killer (NK) cells and

helper T (Th) 17 cells, resulting in inflammation of the spine

joints and sacroiliac joints with their adjacent soft tissues,

tendons and ligaments (6). Through

those responses, fibrosis and calcification ensue, subsequently

leading to bone erosion and new bone formation (12). Consequently, patients with AS suffer

from chronic back and spine pain (13).

Over the past few years, with the development of

technology, there have been a variety of changes in pathology,

diagnosis, and treatment. Especially, in terms of treatment, the

therapy has been revolutionized due to the introduction of

biotechnology medicine (14).

Currently, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), and tumor necrosis

factor (TNF)-α inhibitors are used to relieve pain, restore

physical function, and slow the progression of structural damage

(15,16). Unfortunately, because the mechanism

of AS pathogenesis has not been fully elucidated, the present

treatment mainly focuses on the alleviation of symptoms (17). Moreover, these drugs can cause

several adverse effects from long-term utilization (18). Thus, novel medicine with more

advanced effectiveness and fewer side effects should be explored

for treating AS. Considering the complexity of AS mechanisms, the

multi-targeting traditional Chinese medicines may be promising

alternative treatments for AS. In the present review, the

pathology, symptoms, diagnosis, and current remedies of AS are

described. In addition, recent herbal medicines with their effects

and underlying mechanisms in the treatment of AS, are

presented.

2. Symptoms

The main signs of AS involve back pain,

sacroiliitis, morning stiffness, extra-articular manifestations

such as acute anterior uveitis and IBD (19). Pain in the sacroiliac joint is a

common symptom in the early phase of AS (16). As the disease progresses, patients

with AS may experience mild discomfort or pain (15). At this stage, magnetic resonance

imaging (MRI) can show modest alteration and mild inflammation

(20). As it progresses further,

patients develop severe inflammation and pain along with

abnormalities at the sacroiliac joint, which could emerge in the

imaging (21). The excessive

inflammation causes back pain and morning stiffness, resulting in

restriction of spinal mobility (22). Morning stiffness lasting longer than

30 min is also an important clinical feature of AS (23). Eventually, bone erosion and

formation can lead to the development of syndesmophytes, which

connect adjacent vertebrae (24).

This process can result in fusion of the sacroiliac joints and

spine, leading to loss of spinal mobility, alterations in lumbar

lordosis, and kyphosis, which can be observed on radiographs as the

characteristic ‘bamboo spine’ (24).

3. Pathogenesis

HLA-B27

Several factors are associated with the development

and progression of AS, including genetic predisposition, immune

responses and environmental influences (1). HLA-B27 is known as one of the most

critical genes in AS. HLA is the human version of the major

histocompatibility complex (MHC), which encodes cell surface

proteins essential for adaptive immunity (10). HLA-B27 presents antigenic peptides

to CD8+ T cells, and has been strongly associated with

inflammatory diseases affecting the cartilage and joints (25). The MHC class I encodes HLA-B27,

providing epitopes to T cells and activating cytotoxic T

lymphocytes (CTL) (26). Among the

HLA-B27 subtypes, B*2702, B*2703, B*2704, B*2705 and B*2710 are

associated with a significantly increased susceptibility to AS

(27,28). There are four theories explaining

the mechanism through which HLA influences the development of AS:

The arthritogenic peptide theory, the misfolding theory, the

homodimer theory, and the mimicry theory.

i) The arthritogenic peptide theory postulates that

some microbial peptides similar to self-antigens induce AS

(29). When HLA-B27 presents a

microbial antigen resembling a self-peptide, T cells recognize the

MHC-peptide complexes, leading to autoreactivity and

auto-inflammatory disease (30).

ii) The misfolding theory posits that the unfolded protein response

(UPR) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a major factor in AS

(31). The quaternary structure of

HLA-B27, composed of three components needs proper folding in the

ER for its correct function (32).

If HLA-B27 misfolds due to abnormalities in its cysteine residues,

it can accumulate in the ER, triggering ER stress (33,34).

Additionally, it can activate the UPR and nuclear factor kappa B

(NF-κB) which leads to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines

such as interleukin (IL)-23(35).

iii) The homodimer effect theory is also associated with the

structure of HLA-B27. Disulfide bonds in the cysteine residues

facilitate the formation of α heavy-chain homodimers following

their dissociation from the β light chain (36). The homodimer exhibits a stronger

affinity for killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors (KIRs),

which are expressed on NK cells and Th17 cells that release IL-17,

compared with the heterodimer (37). iv) Finally, the mimicry theory

suggests that the homologous amino acid structures between HLA and

some bacterial antigens can stimulate CTL. CTL would recognize HLA

itself or the peptide directly produced by HLA-B27(38). Notably, certain components of

Klebsiella pneumoniae exhibit genetic sequences similar to

those found in humans, displaying mimicry in AS (39). Although HLA-B27 is regarded as a

critical gene in AS, the pathogenesis of AS remains unclear.

Research indicates that AS may develop in 1-2% of HLA-B27-positive

individuals; however, 5-10% of patients with AS lack HLA-B27

positivity (1). This finding

indicates that HLA-B27 is not directly linked to the manifestation

of AS, suggesting that factors beyond HLA contribute to disease

progression (40).

Endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1

(ERAP1)

ERAP1 is considered to be the second relevant risk

factor for AS (41). In order to

bind to HLA class I molecules, peptides must be cleaved to an

optimal length. In this process, ERAP1 is involved in trimming

precursors to 8-9 amino acids (42). As regards its function, ERAP1 may be

associated with the presentation of aberrant peptides, contributing

to AS, as reported by the Australo-Anglo-American Spondyloarthritis

Consortium (43). Additionally,

loss of ERAP1 function affects HLA-B27 dimerization or misfolding,

leading to the accumulation of abnormally formed HLA-B27 in the ER

(44).

KIR

Immune cells, such as NK cells and Th17 cells,

express killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor, three Ig domains

and long cytoplasmic tail 2 (KIR3DL2) receptor that has a stronger

affinity with the HLA-B27 homodimer (45). Interaction between KIR3DL2 and

HLA-B27 homodimers leads to the production of IL-17, which is known

to have a crucial role in the cytokine network and contributes to

the pathogenesis of AS (22,46).

However, it can be challenging to demonstrate differences between

specific groups, as KIR-mediated responses vary among individuals

(47).

Immune response

AS is a chronic inflammatory SpA, mainly

characterized by the inflammation of the spine and sacroiliac joint

(48). In addition, the tendons and

ligaments attached to the bones contribute to the pathogenesis of

AS, as they are particularly susceptible to inflammatory responses

(49). There are various complex

immune cells and cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of AS

(50). Th17 cells differentiated by

IL-23 are major triggers of inflammation in numerous immune

diseases (51). IL-17 can promote

osteoclastogenesis directly or indirectly through receptor

activator of nuclear factor kappa B (RANK) pathway in conjunction

with TNF-α, thereby inhibiting bone regeneration in SpA (52-54).

It can also stimulate immune cells to release IL-6, TNF-α, and

other cytokines and produce IL-17(55). Autoimmune diseases, including SpA,

IBD, and rheumatoid arthritis, generally arise from dysregulation

of the IL-23/IL-17 pathway (56).

Research has shown that the serum levels of IL-17 and IL-23 are

higher in patients with AS (57).

Nevertheless, the role of IL-23 in AS remains controversial, as its

inhibition has shown limited success (58).

Apart from the IL-23/IL-17 axis, IL-22, IL-32γ, and

IL-37 are known to contribute to the initiation of AS development.

IL-22 was reported to participate in osteogenesis, stimulating

osteoproliferation when exposed to IL-23 in an inflammatory state

(54,59). IL-32γ was shown to be increased in

specific regions such as the joints and tissues in patients with

AS, to generate osteoblast differentiation and abnormal new bone

formation (60). Moreover, IL-37

was also demonstrated to be elevated in patients with AS, with its

increase associated with disease severity and bone mineral density

(61).

Gut microbiome

Recently, growing evidence suggests that the

microbiome, a collection of microorganisms in specific organs of

the body, contributes to the development of AS (62). The gut microbiome exists in

intestinal mucosal surfaces acting as a safeguard against pathogens

(63). Occurrence of gut dysbiosis

may alter the permeability of the intestinal mucosa, inducing

penetration of microbial components (64). This disruption leads to damage in

the mucosal barrier, subsequently activating both innate immunity

and adaptive immunity (65). As a

result, bacterial antigens may enter sacroiliac joints and the

spine through lymph nodes, inducing inflammatory responses

(66). Research has shown that gut

dysbiosis may increase the risk of AS, as nearly 70% of patients

with AS exhibit gut inflammation (67).

4. Diagnosis

The Rome criteria was first established in 1961 by

the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences

(68). It included radiographic

findings and clinical presentation. Later, the same council added

the sacroiliitis grading system in the original criteria which is

called the New York criteria. Although the New York criteria has

been modified over the past two decades to be more inclusive, it

still has limitations due to the low sensitivity of X-rays

(69,70). The development of MRI has made it

possible to detect inflammatory changes in the sacroiliac joints at

early stages, as well as structural alterations associated with

advanced AS, with high precision (70). Due to the advent of MRI technology,

the new criteria can classify patients who exhibit active

sacroiliitis on the MRI with one clinical feature as patients with

SpA. This differs from the previous modified New York criteria

which diagnosed patients based on bilateral moderate or unilateral

severe sacroiliitis, which often led to a delay in diagnosis of

approximately 7 to 10 years (70).

The criteria are called Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity

Score (ASDAS) which was determined by the Assessment of

Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS) in 2009. ASDAS is a

measure of disease activity using patient global assessment,

clinical pain, and morning stiffness duration (15). The ASDAS score can be categorized

into various levels indicating the disease activity. Additionally,

the Bath Ankylosing Disease Activity Index (BASDAI), a

patient-reported questionnaire, was developed to assess fatigue,

pain, and morning stiffness. It relies on patient self-reporting

and is therefore considered less objective than the ASDAS (15). The ASDAS with the BASDAI now serve

as the principal criteria in AS. However, ASDAS and BASDAI alone

are insufficient for an accurate diagnosis of AS; therefore,

radiographic evaluation and biomarker analysis should also be

included (15).

5. Treatment

The treatment of AS focuses on alleviating back

pain, morning stiffness, and loss of flexibility, as well as

reducing inflammation and preventing complications (1). To date, anti-inflammatory drugs are

the first-line treatment, according to the 2010 recommendations of

the ASAS (71).

Physical therapy (exercise)

Regarding daily activity and overall well-being,

exercise is recommended in clinical guidelines for managing AS to

alleviate pain, improve joint mobility, and maintain muscle

strength (72). Research has shown

that the combination of appropriate medication and physical

activities could be effective (73). In this context, patient education

and maintaining proper posture are important for achieving optimal

treatment effectiveness (74).

Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are the first-line treatment for patients

with active AS (75). They block

the formation of prostaglandin by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX)

enzymes (76). Particularly,

prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2) promotes the activation of Th17 cells,

leading to the production of IL-23 and IL-17, which are strongly

implicated in inflammation in AS (77). However, prescribing the appropriate

NSAID can be challenging, as treatment response rates vary among

individuals. Therefore, NSAIDs should be selected based on the

prior response of the patient to these drugs, and their risk

factors for adverse effects (78).

In clinical practice, daily administration is more effective in

slowing the progression of AS than on-demand use (79). Prolonged use of these medications

can lead to gastrointestinal (GI) or cardiovascular events

(18).

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs

(DMARDs)

DMARDs are prescribed for patients with AS who are

unresponsive to NSAIDs (80).

Sulfasalazine is a typical DMARD for acute anterior uveitis in AS

by inhibiting the formation of prostaglandins. Additionally,

methotrexate, which blocks dihydrofolate reductase and,

subsequently inhibits deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) synthesis, can be

another solution (81). However,

the efficacy of DMARDs on AS is unclear. Most studies have shown

that DMARDs mainly target peripheral joints and certain

extra-articular manifestations, but have limited efficacy for axial

involvement, such as back pain (13,17).

TNF-α inhibitors

TNF-α is a cytokine that is produced by macrophages

and lymphocytes (82). Patients

with AS tend to have elevated levels of TNF-α, indicating its

crucial role in the pathogenicity of AS (83). TNF-α inhibitors are an effective

treatment option for patients with AS, particularly those with an

inadequate response to NSAIDs (84). If the combination of more than 2

types of NSAIDs is ineffective even after 3 months of treatment,

the ASAS guidelines recommend the use of TNF-α inhibitors (71). TNF-α inhibitors are beneficial for

alleviating back pain, peripheral arthritis, morning stiffness, and

inflammatory activity and improving overall daily functioning

(85). Infliximab, the first

developed TNF-α inhibitor, is a monoclonal immunoglobulin G1

antibody consisting of 75% human and 25% mouse sequence, which

binds to the dissolved and receptor-bound forms of TNF-α (86,87).

Adalimumab is a 100% human monoclonal antibody against TNF-α,

blocking inflammatory processes (88). It is recommended to use it

subcutaneously at 40 mg once every 2 weeks (89). Golimumab is also a fully human

monoclonal antibody binding to TNF-α (90). The Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) approved its use for patients with AS by subcutaneous

injection of 50 mg once a month (91). Certolizumab pegol is a fragment

crystallizable (Fc)-free monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-α

and neutralizes it. However, its long-term efficacy and potential

adverse effects require further investigation (86). Etanercept is a recombinant protein

fused with the Fc portion of immunoglobulin G1 and the TNF

receptor. It has an affinity with the soluble form of TNF-α, thus

blocking interaction with cell receptors. It is administered at 50

mg once or 25 mg twice per week subcutaneously (92). However, there are several challenges

associated with the use of TNF-α inhibitors in the treatment of AS.

Notably, ~40% of patients with AS have intolerance or inactivity to

medications (93). In addition,

recurrence of infections, such as tuberculosis (TB) and

candidiasis, can appear by inhibiting immune responses (94). Furthermore, long-term use does not

guarantee sustained remission (95).

IL-17 inhibitors

In recent years, research has found that the level

of IL-17 is regularly higher in patients with AS, which means it

has a key role in the onset of AS. Therefore, IL-17 has emerged as

one of the important targets in developing drugs for treating AS

(96). IL-17 inhibitors can serve

as a second-line treatment in patients who fail to respond to TNF-α

inhibitors (97). Secukinumab is

the first accepted monoclonal antibody and it is effective in

rapidly and sustainably relieving pain, as well as reducing bone

marrow edema in the sacroiliac joints (98-100).

It is considered to be advantageous in patients with TB, as there

is no evidence of TB occurrence or reactivation associated with its

use (101). Moreover, the efficacy

of secukinumab is maintained long-term, reportedly up to ~5 years

(100). Ixekizumab, an

immunoglobulin G4 monoclonal antibody, was recently approved as an

IL-17A inhibitor (102). It

improves joint and skin symptoms but remains less effective for

gastrointestinal manifestations, which may contribute to the

development of IBD (103).

Bimekizumab, another monoclonal antibody, can neutralize both

cytokines, IL-17A and IL-17F, concurrently (104). It can reduce disease activity,

C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, and bone marrow edema as observed

on MRI, thereby improving scores on the ASDAS (105). Brodalumab is a monoclonal antibody

targeting IL-17 receptor A, unlike bimekizumab. Its efficacy was

validated for psoriatic arthritis, but adverse events were also

reported, including infections, and GI disorders (106). However, a 3-year follow-up of

patients with psoriasis treated with brodalumab revealed

conflicting reports regarding suicidal ideation (107). Therefore, it needs to be further

investigated with continuous monitoring.

Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors

The JAK pathway involves the expression of

cytokines, which are related to cell proliferation and

inflammation, eventually leading to autoimmune disorders (108). The IL-23/IL-17 axis, a major

regulator in the SpA immune system, could be partially controlled

by the JAK signaling pathway (109). Tofacitinib is a first-in-class JAK

inhibitor that targets JAK1, JAK3, and to a lesser degree

JAK2(110). It interferes with

cytokine-induced signal transduction, leading to abnormal immune

responses (111). Tofacitinib is

generally effective in AS due to its targeting of other JAK

proteins (112). Nevertheless,

clinical trials for JAK2-specific inhibitors are also required

(113). Upadacitinib is also a JAK

inhibitor that targets JAK1 selectively (114). It has recently been studied in

patients with AS who are unresponsive or intolerant to NSAIDs, as

part of the SELECT-AXIS 1 clinical trial (115). However, there was a report that

JAK inhibitors increase the possibility of thrombosis; therefore,

further data to assess the risk is needed (116).

6. Alternative and complementary

treatment

To date, drug therapy has been considered as a main

treatment for AS; however, there have been several adverse effects

and inconveniences to using these medications due to their

long-term use and cost (18,117).

In particular, long-term use of these drugs can lead to GI,

cardiovascular, and renal complications (118,119). In addition, their high cost is a

critical obstacle, as these treatments are generally unaffordable

for most patients (117). For that

reason, alternative and complementary therapies may represent a

viable option due to their safety and cost-effectiveness in

treating AS. However, they are not included in the official

standard treatment guidelines (120). International articles regarding

alternative and complementary treatments for AS were collected from

the PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and Google Scholar

(https://scholar.google.com). The

keywords included ‘ankylosing spondylitis’, ‘spondyloarthropathy’,

‘oriental medicine’, ‘herbs’ and ‘therapy’. In this section,

efficacious remedies for treating AS are introduced.

Moxibustion

Moxibustion is a heat therapy that puts burned

‘moxa’, dried Artemisia genus leaves (common name: mugwort),

on acupoints of the skin stimulating thermal sensory receptors.

When receptors are activated by stimulation, therapeutic effects

occur when the nerve fibers transmit signals to the central nervous

system (121). In clinical

practice, patients treated with moxibustion, either in combination

with Western medicine or alone, demonstrated greater clinical

efficacy and lower CRP and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

levels compared with Western medicine treatment alone. CRP and ESR

are two general indicators in monitoring the activity of

inflammation. However, no significant differences were observed

between the treatment with moxibustion alone and Western medicine

alone, suggesting that the combination therapy with moxibustion and

Western medicine may be an important approach in managing AS

(121). In another study with a

collagen-induced arthritis mouse model, the IL-6 level was lower in

the moxibustion-treated group than the untreated group (122). Moxibustion may also be associated

with regulating Treg cell numbers and altering NF-κB expression

(123). Additionally, moxibustion

can be used with warm acupuncture. After a sterilized needle is

inserted at a specific point, a moxa stick is placed on the needle

and ignited, delivering heat directly to the needle site. This

treatment could control the blood circulation, and improve the

immune system by reducing inflammatory cytokines (124). However, large-scale randomized

controlled trials are needed to confirm the efficacy of

moxibustion.

Herbal medicines

Herbal medicines are effective in alleviating

clinical symptoms and improving the quality of life of patients

(125). Because the constituents

of herbal medicines are complex and variable, elucidating their

exact mechanisms remains challenging (126). Currently, network pharmacology

serves as an effective tool bridging the gap between modern science

and traditional medicine, providing a foundation for further

studies aimed at identifying active compounds and elucidating the

mechanisms of herbal medicines (127). The present review summarizes the

efficacy and underlying mechanisms of these therapies for the

management of AS, as reported in experimental studies (Table I, Table

II and Table III).

| Table IList of formulations for AS. |

Table I

List of formulations for AS.

| First author,

year | Formulation | Experimental

design | Efficacy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Huang et al,

2014 |

Bushen-Qiangdu-Zhilv decoction | M1-polarized Raw

264.7 macrophage-like cells with 100 ng/ml interferon-γ | Suppresses TNF-α

and IL-1 mRNA expression levels | (128) |

| Li et al,

2016 | Kunxian

capsule | RCT | Decreases the

disease activity of patients with AS assessed by international

indicators ASAS 20, BASDAI 50, ASDAS-CRP, and serum CRP as well as

by patient global assessment of the disease activity, total back

pain, level of morning stiffness, tender joints, and BASFI

score. | (129) |

| Xie et al,

2022 | Fengshi Gutong

capsule | RCT | Decreases disease

activity of active patients with AS/ASDAS-CRP, BASDAI, BASFI,

BASMI, morning stiffness scores, PGA, nocturnal pain, total back

pain, CRP | (130) |

| Xie et al,

2017 |

Yun-Pi-Yi-Shen-Tong-Du-Tang | Network

analysis | Reduces the

symptoms of morning stiffness, fatigue, pain and decreases the

level of BASDAI, ASDAS-CRP and ASDAS-ESR Associated with the TLR

signaling pathway, the AMPK signaling pathway, the T-cell receptor

signaling pathway, and the TNF signaling pathway | (131) |

| Li et al,

2022 | Xinfeng

capsule | Network

analysis | Improves PLT, ESR,

and hs-CRP Associated with the NF-κB signaling pathway, the TNF

signaling pathway, and the IL-17 signaling pathway | (133) |

| Zhang et al,

2024 | Qiangji Jianpi

decoction | Network

analysis | Associated with

lipids and atherosclerosis, the IL-17 signaling pathway, the TNF

signaling pathway, chemical carcinogenesis-receptor activation, and

the AGE RAGE signaling pathway | (134) |

| Table IIList of herbs for AS. |

Table II

List of herbs for AS.

| First author,

year | Herb | Experimental

design | Efficacy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Wang et al,

2024 |

Epimedium | Network

analysis | Modulates signaling

pathways such as the AGE-RAGE, TNF, NF-κB/MAPK, and Toll-like

receptor signaling pathways | (139) |

| Li et al,

2022 | Scutellaria

baicalensis Georgi | Network

analysis | Involved in the

IL-17 pathway, TNF pathway, and NF-κB pathway | (141) |

| Fang et al,

2022 | Salvia

miltiorrhiza Bunge | Network analysis

and PBMCs from patients with AS | Inhibits the

expression levels of PTGS2, IL-6, and TNF-α Reduces ESR and CRP

Associated with the TNF, HIF-1, NF-κB, JAK-STAT, TLR, TGF-β, FoxO,

cytokine receptor interaction, PI3K-Akt, and the MAPK signaling

pathway | (143) |

| Dong et al,

2017 |

Chrysanthemum indicum

Linne | 2 mg Human

proteoglycan extract dissolved in 2 mg DDA induced AS mice | Delays the

progression of peripheral disease (paw swelling and stiffness of

rear leg joints in mice) Alleviates the spondylitis score Decreases

the serum levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 Upregulates the serum

levels of SOD, CAT, and GSH-Px and downregulates the serum levels

of MDA Decreases NF-κB p65 protein Increases the expression level

of SOST and DKK-1 in AS tissues | (147) |

| Table IIIList of compounds derived from herbs

for AS. |

Table III

List of compounds derived from herbs

for AS.

| First author,

year | Compound | Experimental

design | Efficacy | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Zou et al,

2016 | Celastrol | Hip synovial

fibroblasts from 6 patients with AS | Reduces the cell

viability and EdU-positive AS fibroblasts Decreases ALP activity

Inhibits PEG-2-induced osteogenesis Inhibits the mRNA expression of

BMP2, type I collagen, RUNX2 | (151) |

| Liu et al,

2016 | Naringin | Zygotes from human

chorionic gonadotropin hormone-injected mice and HLAB2704 gene

fragment-injected pseudocyesis mice | Increases

osteocalcin and ALP Decreases the concentration of triglycerides

Attenuates the NF-κB p65, TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6 activity values

Downregulates the level of MDA and upregulates the expression of

SOD, CAT and GSH-Px Decreases STAT3 and JAK2 | (154) |

| Feng et al,

2020 | Punicalagin | 2 mg of Human

proteoglycan extract dissolved in 2 mg DDA-induced AS mice | Reduces peripheral

disease progression scored for signs and symptoms of arthritis

Reduces IVD damage progression Downregulates the levels of ROS and

MDA and upregulates the levels of SOD, CAT and GPx in the

connective tissues excised from the vertebra Decreases the serum

levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-17A, IL-23 and NO Downregulates

the activation of NF-κB and the phosphorylation levels of JAK2 and

STAT3 | (155) |

| Dong, 2018 | Sinomenine | 2 mg Human

proteoglycan extract dissolved in 2 mg DDA-induced AS mice | Decreases the

levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 Increases the levels of SOD, CAT,

and GSH-Px Decreases NF-κBp65 and p-p38 Increases the level of IκB

Decreases the level of COX-2 | (157) |

Formulations. Bushen-Qiangdu-Zhilv

(BQZ) decoction

BQZ decoction is a traditional Chinese medicine that

is used in AS. It is composed of Drynariae Rhizoma,

Psoraleae Fructus, Rehmanniae Praeparata Radix,

Epimedii Herba, Notopterygii Rhizoma et Radix,

Cibotii Rhizoma, Angelicae Pubescentis Radix,

Dipsaci Radix, Eucommiae Cortex, Cyathulae Radix,

Lycopi Herba, Cinnamomi Ramulus, Anemarrhenae

Rhizoma, Aconiti carmichaeli Radix, Ephedrae

Herba, Zingiberis Rhizoma, Atractylodis Rhizoma

Alba, Clematidis Radix, Saposhnikoviae Radix,

Coicis Semen, Paeoniae Radix, and Paeoniae Radix

Alba. In a previous study, BQZ decoction was extracted with

petroleum ether, ethyl acetate, n-butanol (BU) and water. BQZ was

incubated in M1-polarized RAW264 cells that were first induced by

interferon (IFN)-γ. The BQZ water extract significantly decreased

the mRNA level of TNF-α, while the BQZ BU extracts suppressed that

of IL-1. Moreover, neither the water nor the BU extracts induced

cell death. These findings indicate that the BQZ decoction is

beneficial in reducing inflammation and has low cytotoxicity

(128).

Kunxian (KX) capsule

The KX capsule is used as an anti-inflammatory

regulator in autoimmune diseases in China. KX has been reported to

reduce back pain and morning stiffness in AS. It is composed of

four main herbs, namely Tripterygium wildfordii Hook. f.,

Epimedii Herba, Cuscutae Semen, and Lycii

Fructus. A previous randomized, double-blind, controlled trial

involving 80 patients with AS was conducted to evaluate the

efficacy of KX. The study used various indices to assess the

effects of KX in patients with AS. The KX-treated group showed

improvement in indicators, including the ASAS 20, BASDAI 50,

ASDAS-CRP, serum CRP, and Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional

Index when compared to the placebo group. Moreover, 37% of the

patients in the KX group achieved an ASAS 20 at week 12, and marked

improvements in the BASDAI 50 were observed in 40% of the patients

at week 6(129).

Fengshi Gutong capsule (FSGTC)

FSGTC is a traditional Chinese medicine used for

patients suffering from joint pain in China. It contains seven

herbs including Aconiti Radix Cocta, Aconiti Kusnezoffii

Radix Cocta, Carthami Flos, Glycyrrhizae Radix Et

Rhizoma, Chaenomelis Fructus, Mume Fructus, and

Ephedrae Herba. A previous study recruited 180 patients with

AS and randomized them into three groups by treatment type: The

combination group, the FSGTC group, and the imrecoxib group. The

ASAS20 response rate was measured as the primary endpoint. The

results showed that the ASAS20 rate in the FSGTC group was higher

than that in the imrecoxib group. Moreover, the other indicators,

including the ASDAS-CRP, patient's global assessment of disease

activity, morning stiffness, and BASDAI, were improved in the

combination and FSGTC groups compared with the imrecoxib group. In

the safety test, the FSGTC group exhibited the lowest adverse

effects, especially in GI tolerability. The findings indicate that

FSGTC alone or combined with NSAIDs may be another viable option

for patients with GI intolerance (130).

Yun-Pi-Yi-Shen-Tong-Du-Tang (ΥΥΤ)

YYT is a traditional formula that consists of 11

medicinal herbs: Dioscoreae Rhizoma, Atractylodis

Rhizoma, Smilacis Glabrae Rhizoma, Lonicerae

Japonicae Flos, Achyranthis Bidentatae Radix,

Myrrha, Aconiti Praeparata Radix, Astragali

Radix, Glycyrrhizae Radix et Rhizoma, Hirudo, and

Coptidis Rhizoma. A previous study used network pharmacology

to compare YYT targets with those of FDA-approved drugs and

AS-related proteins. A total of 34 proteins overlapped between YYT

targets and drug targets, including TNF and COX-2. Additionally,

YYT targets and AS-related proteins formed 3,732 protein-protein

interaction (PPI) pairs, highlighting two key targets: JAK2 and

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3). These

results indicate the YYT might enhance the effects of western

medicine and exert therapeutic effects on AS-related inflammation

(131).

Xinfeng capsule (XFC)

XFC has been used to treat AS for >10 years and

is associated with fewer adverse effects (132). It primarily consists of four

herbs: Astragali Radix, Coicis Semen, Tripterygium

wilfordii Hook. f., and Scolopendra. In a previous

network analysis, the 103 active compounds and 212 potential

targets of XFC were compared with 1,961 AS-related targets,

resulting in 59 overlapping targets. PPI analysis and core target

screening identified 13 key targets, including IL-4, IL-6, TNF,

IL-1β, vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA), IL-10, C-C

motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2), COX-2, C-X-C motif chemokine

ligand 8 (CXCL8), epidermal growth factor, STAT3, NF-κB inhibitor

alpha, and IFN-γ. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG)

enrichment identified 20 important pathways including the NF-κB,

TNF, and IL-17 signaling pathways, which involve inflammatory

responses. In addition, among the 103 active compounds analyzed,

the top four active ingredients that have a strong connection to AS

targets were as follows: Formononetin, triptolide, quercetin, and

kaempferol. Molecular docking of the components with the core

targets IL-6, CCL2, TNF, and IL-4 suggested that formononetin,

triptolide, quercetin, and kaempferol may have important roles in

the treatment of AS (133).

Qiangji Jianpi (QJJP) decoction

QJJP decoction is a modified traditional Chinese

medicine which includes Astragali Radix, Codonopsis

Pilosulae Radix, Atractylodes Rhizome, Angelicae

Sinensis Radix, Cimicifugae Rhizoma, Bupleuri

Radix, Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium and Glycyrrhizae

Radix et Rhizoma. A previous study used network pharmacology,

molecular docking, and Mendelian randomization to analyze the

interactions among the decoction, IBD, and AS. The results showed

that, among 105 targets of the QJJP decoction, 85 targets

overlapped with targets associated with both AS and IBD. In the

Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG pathways, the targets were associated

with oxidative stress, which is thought to be one of the main

features of IBD. Molecular docking indicated IL-1α, IFN-γ, TGF-β1,

and endothelin-1 as important targets for the treatment of AS with

IBD. IFN-γ is a cytokine that is released in the innate and

adaptive immune systems (134).

IFN-γ is known to be strongly produced in patients with AS

following stimulation with Mycoplasma arthritis (135). Additionally, IFN-γ was revealed to

be closely related to the HLA-B27-associated unfolded protein

responses in SpA, indicating that IFN-γ could be one of the

critical biomarkers for diagnosing and treating AS (136).

Herbs. Epimedium (EP)

EP, the largest herbaceous genus of the

Berberidaceae family, has various components including flavonoids,

alkaloids, and other compounds (137). It has been used as an

antirheumatic agent with its anti-inflammatory effects (138). Using network pharmacology, 16

active compounds were identified in EP, and the corresponding EP

targets were subsequently matched with disease targets, yielding 80

overlapping targets. The core active compounds were

8-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)-2-phenylchromone, anhydroicaritin, and

luteolin, and the top-ranked overlapped targets were TNF, IL-6,

IL-1β, matrix metalloproteinase-9, and COX-2. Through molecular

docking and molecular dynamic simulation analysis, it was found

that the core compounds of EP have a strong binding activity and

stable interactions with five core targets. These findings

indicated that EP has the potential to be used in the treatment of

AS with the intersecting target genes (139).

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi

(SBG)

SBG is a species of the Lamiaceae family, and its

root is mainly used in various treatments. It is usually used in

immune disorders and inflammatory diseases (140). The acquired active components and

targets of SBG were analyzed by network analysis. The main

components of SBG were baicalein, wogonin, and oroxylin A. Among

them, 29 targets overlapped with AS targets. In the PPI analysis,

TNF, IL-6, CXCL8, COX-2, and VEGFA were found to be associated with

SBG in AS. Moreover, the core targets and main compounds exhibited

strong connections in the molecular docking. As mentioned for

NSAIDs, COX-2 mediates inflammatory pathways by inducing PG

production. PG promotes the proliferation of synoviocytes and

inflammation. Therefore, these findings indicated that SBG may have

a therapeutic role in AS similar to that of NSAIDs (141).

Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge

Salvia miltiorrhiza Radix (SMR) is from the

root of Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge, a plant of the Lamiaceae

family. It has been used to treat various diseases, including

cardiovascular and immune diseases (142). A previous study conducted data

mining, network pharmacology, and in vitro assays. In

clinical trials, immunology indices, including ESR, CRP, and

complement component 3, were significantly reduced in 2,079

patients compared with baseline measurements. To identify the

therapeutic targets against AS, the study used network

pharmacology. The study identified COX-2, IL-6, TNF, STAT3, and

VEGFA as key targets of SMR in the treatment of AS. Furthermore,

the TNF signaling pathway appeared to be the most enriched pathway

in the KEGG enrichment analysis. Moreover, cryptotanshinone and

tanshinone IIA exhibited higher affinities with key targets,

including TNF-α, IL-6, and COX-2 through molecular docking. In

in vitro assays using peripheral blood mononuclear cells

from patients with AS, it was demonstrated that cryptotanshinone

and tanshinone IIA, the main compounds of SMR, significantly

reduced the protein expression levels of COX-2, IL-6, and TNF-α.

Consequently, the results indicated that SMR may inhibit the TNF

signaling pathway by modulating the expression of COX-2, IL-6, and

TNF-α (143).

Chrysanthemum indicum (C. indicum)

Linne

C. indicum Linne has been commonly used in

Korean, Chinese, and Japanese medicine for the treatment of

autoimmune diseases. Various studies have concluded that C.

indicum possesses antimicrobial, antioxidant, and

immuneregulatory properties (144-146).

A previous study assessed disease severity in the intervertebral

joints by comparing the quantitative changes in the C.

indicum-treated group with the control AS group. The treatment

group that received the C. indicum extract exhibited

decreased levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, and NF-κB p65 protein.

Antioxidant enzymes including catalase, superoxide dismutase, and

glutathione peroxidase were regulated in the AS mice compared with

the control group. Moreover, the levels of sclerostin and

dickkopf-1, which inhibit the wingless and Int-1 (Wnt) pathway were

increased in the AS mice. These findings indicated that C.

indicum can inhibit the Wnt pathway, which plays a key role in

the production, growth, and maturation of osteoblastic cells.

Overall, C. indicum may have a beneficial role in oxidative

stress, inflammation, and osteogenesis in the treatment of AS

(147).

Compounds. Celastrol

Celastrol,

(2R,4aS,6aS,12bR,14aS,14bR)-10-hydroxy-2,4a,6a,9,12b,14a-hexamethyl-11-oxo-1,2,3,4,4a,5,6,6a,11,12b,13,14,14a,14b-tetradecahydropicene-2-carboxylic

acid), is one of the compounds in T. wilfordii Hook. f.,

revealed to have effects on decreasing inflammation and reducing

arthritis (148). Fibroblasts

obtained from hip synovial tissues of patients with AS were

incubated with PGE-2, which promotes proliferation and

osteogenesis, and celastrol. Notably, 1.0 µM celastrol had an

inhibitory effect against alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and

mineralization. In addition, it significantly reduced the gene

expression levels of bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP2) and the

regulation of runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) in the

fibroblasts. BMP2, a key inducer of osteogenic activity in AS,

upregulates RUNX2 expression, a transcription factor for ALP that

promotes osteoblast differentiation (149,150). In further investigation with 1.0

µM celastrol, the levels of PGE-2, protein kinase B (AKT) and

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) were decreased, and the Wnt

pathway was inhibited. Consequently, celastrol may inhibit the

formation of abnormal new bone by blocking PGE-2 and the Wnt

signaling pathway (151).

Naringin

Naringin is a natural flavonoid that can be found

in citrus fruits. It has been suggested to affect oxidation and

inflammation (152). Additionally,

naringin has been reported to possess osteogenic effects (153). A study established an AS-induced

mouse model and treated the mice with naringin at doses of 20, 40

and 80 mg/kg. Following treatment, the expression values of

osteocalcin, ALP, and triglyceride activity became similar to those

of the healthy group. The naringin-treated groups exhibited

significant anti-inflammatory effects by modulating TNF-α, IL-1β,

and IL-6, as well as improving oxidative stress markers.

Furthermore, the JAK2/STAT3 signaling pathways were suppressed by

naringin treatment (154).

Punicalagin

Punicalagin

(2,3-hexahydroxydiphenoyl-gallagyl-D-glucose), a water-soluble

compound usually present in Punica granatum Linné, is

considered to have anti-inflammatory effects in AS. In a previous

study, AS-induced mice injected with human proteoglycan extract

were treated with punicalagin. As a result, the punicalagin

treatment significantly improved antioxidant enzyme activities. It

decreased the levels of reactive oxygen species and

malondialdehyde, indicating that punicalagin may have a direct

effect on oxidative stress. Regarding the anti-inflammatory effects

of punicalagin, serum levels of cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6,

TNF-α, IL-17A, and IL-23, were reduced. The reduction of IL-1β,

IL-6, and TNF-α suggests that punicalagin may inhibit the NF-κB

pathway, which is generally associated with oxidative stress.

Moreover, the JAK2 and STAT3 phosphorylation levels were decreased

in the punicalagin-treated groups (155).

Sinomenine

Sinomenine

(7,8-didehydro-4-hydroxy3,7-dimethoxy-17-methyl-9a, 13a,

14a-morphinan-6-one) is derived from Sinomenium acutum

Rehder et Wilson, and widely used for rheumatoid arthritis in China

(156). Previous research has

focused on the NF-κB pathway, the mitogen-activated protein kinase

(MAPK) p38 pathway, and COX-2, as these have been reported to

modulate inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress. In this

study, AS mice were treated with different doses of sinomenine (10,

30, and 50 mg/kg), and in the sinomenine-treated AS mouse groups,

the levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 were dose-dependently reduced.

Moreover, antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, glutathione

peroxidase and superoxide dismutase were increased compared with

the control AS group. Furthermore, the mRNA expression levels of

NF-κBp65 and COX-2 were decreased, while the sinomenine treatment

increased the expression level of the inhibitor of NF-κB. Overall,

sinomenine ameliorated AS via inhibition of the MAPKp38 and NF-κB

pathways, and COX-2 expression (157).

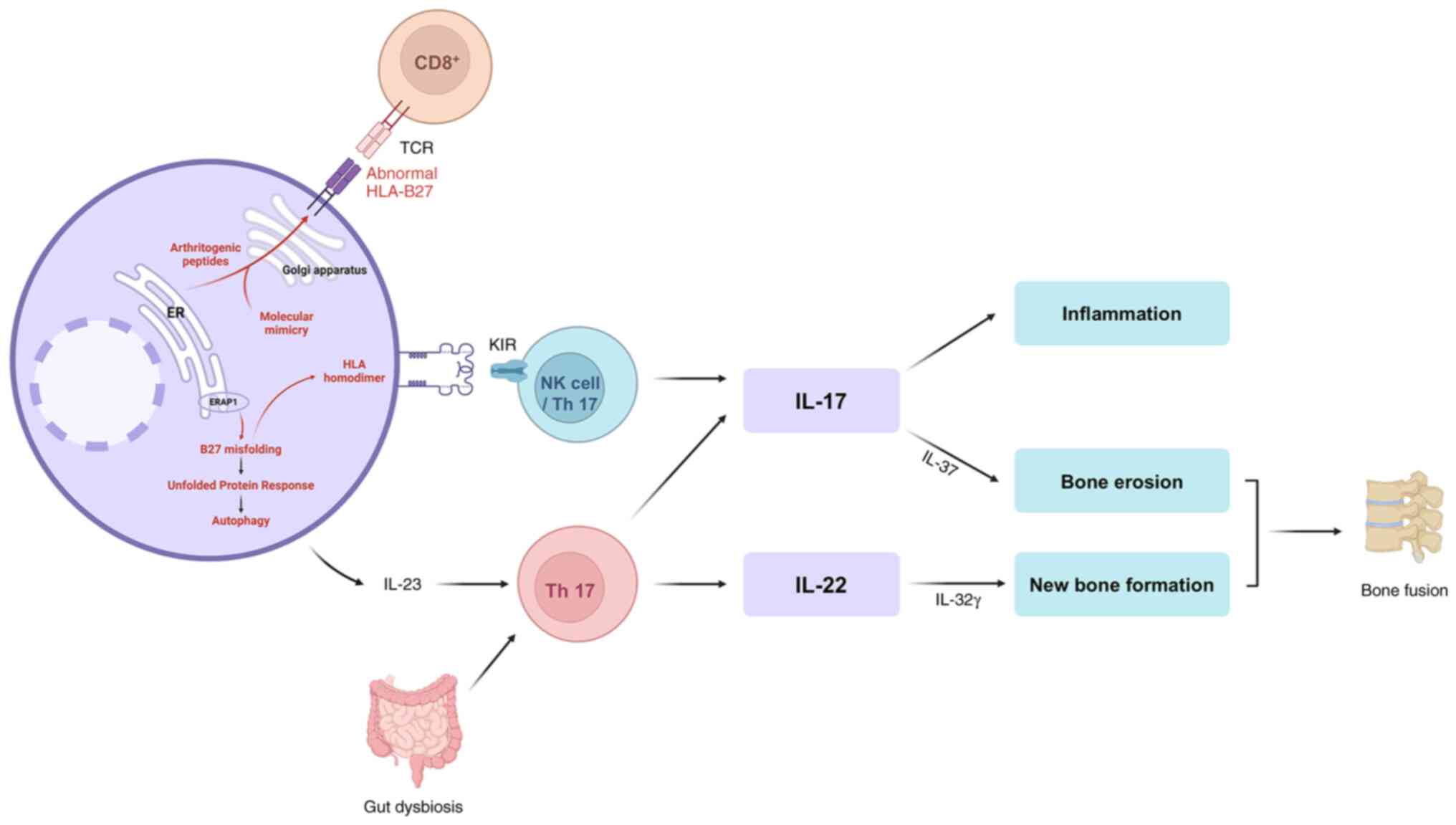

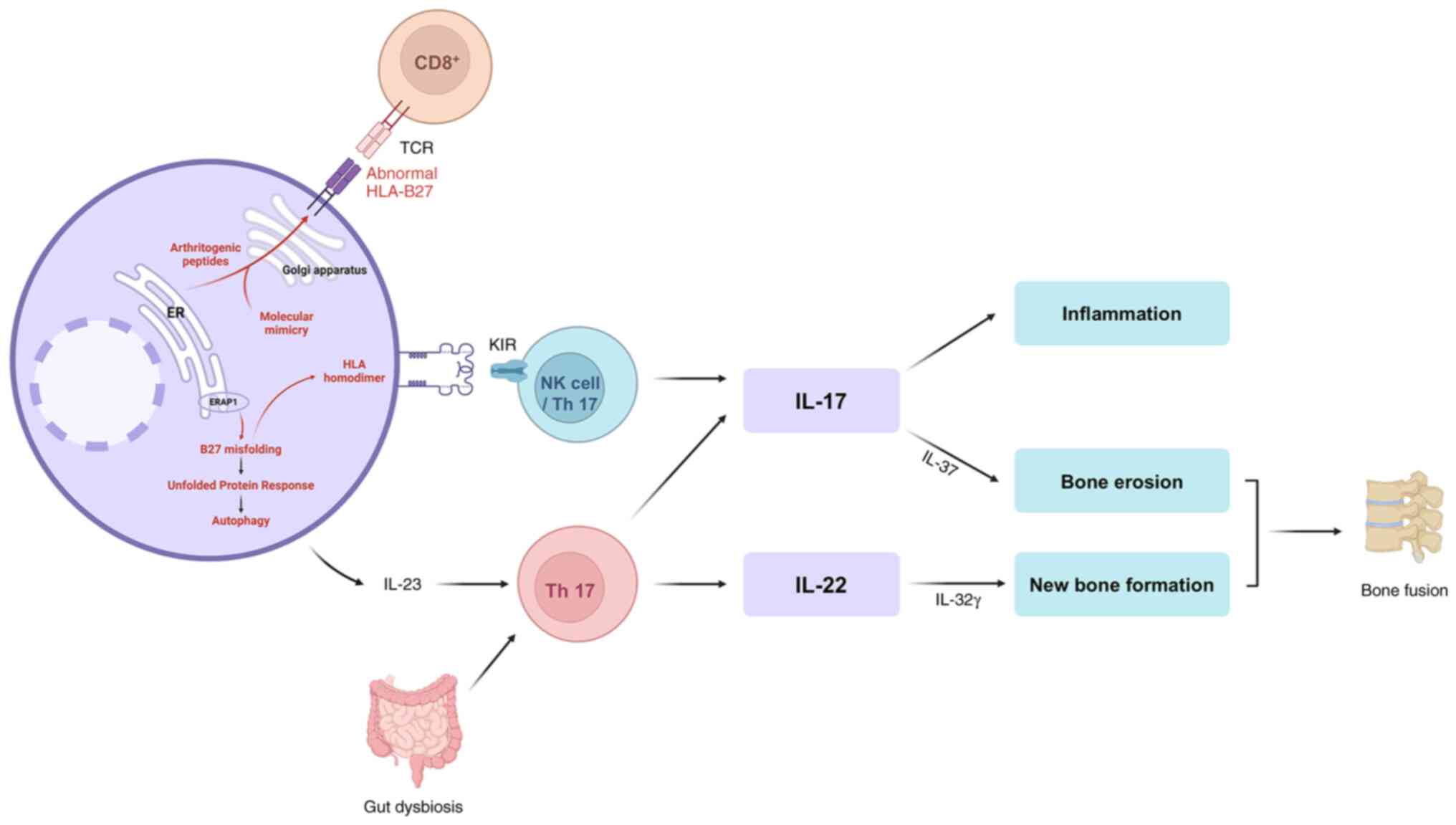

7. Conclusion

AS is a progressive chronic disease that typically

occurs around the second decade of life. Patients with AS

experience pain in the sacroiliac joint, morning stiffness, bone

erosion, and bone formation, which can lead to bone fusion known as

syndesmophytes. In diagnosing AS, criteria from the ASAS,

patient-reported questionnaires such as the BASDAI, and radiographs

are used to assess disease progression. Although the pathogenesis

of AS has yet to be fully elucidated, HLA-B27 is considered to be

an important factor. There are four hypotheses regarding

HLA-related pathogenesis in AS: The arthritogenic peptide theory,

the misfolding theory, the homodimer theory, and the mimicry

theory. The arthritogenic peptide and mimicry theories suggest that

the presentation of an abnormal peptide to HLA activates

CD8+ T cells. The misfolding theory and ERAP1, a

secondary risk factor, are associated. When ERAP1 dysfunction leads

to abnormal peptide trimming, HLA molecules fail to fold properly

and accumulate in the ER, causing ER stress and UPR. This in turn

activates autophagy, promoting IL-23 production. The homodimer

theory suggests that dissociation of the β light chain in HLA

enhances its affinity for KIRs, which are expressed on the surface

of NK cells and Th17 cells. Th17 cells activated by IL-23 and the

homodimer promote the release of IL-17 and IL-22. IL-17 induces

inflammation and bone erosion. IL-22 stimulates new bone formation.

Thus, the bone erosion and new bone formation develop into bone

fusion (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1Diagram of possible pathogenesis of

ankylosing spondylitis. The four hypotheses of HLA-related

pathogenesis: The arthritogenic peptide theory, the misfolding

theory, the homodimer theory, and the mimicry theory. The

arthritogenic peptide theory suggests that presentation of abnormal

or self-like peptides by HLA-B27 activates autoreactive

CD8+ T cells. The misfolding theory emphasizes that

ERAP1 variants generate aberrant peptides that fail to stabilize

HLA molecules, resulting in misfolded HLA accumulation in the ER.

This induces ER stress and the UPR, subsequently activating

autophagy and promoting IL-23 production. The homodimer theory

suggests that dissociation of the β2-microglobulin light

chain allows HLA-B27 heavy chains to form homodimers, which

strongly interact with KIRs on NK and Th17 cells. Th17 activation

by IL-23 and homodimer signaling promotes release of IL-17 and

IL-22, leading to inflammation, bone erosion, and new bone

formation. The mimicry theory proposes that microbial peptides

structurally resemble self-peptides, leading to cross-reactive

immune responses when presented by HLA-B27. The interplay of bone

erosion and aberrant new bone formation ultimately contributes to

pathological bone fusion. HLA, human leukocyte antigen, ERAP1,

endoplasmic reticulum aminopeptidase 1; ER, endoplasmic reticulum;

UPR, unfolded protein response; IL, interleukin; KIRs, killer

immunoglobulin-like receptors; NK, natural killer. |

Treatment for AS includes physical exercise and

pharmacological approaches. The main drugs currently in use are

NSAIDs, DMARDs, and TNF-α inhibitors, and IL-17 inhibitors and JAK

inhibitors are currently in development. These drugs primarily

target the control of inflammation. However, Western medicine can

cause side effects depending on treatment duration and is

associated with a significant cost burden. Therefore, alternative

and complementary therapies may be another option for treating AS.

Commonly used alternative remedies include moxibustion and herbal

medicines. Moxibustion is a heat therapy that transmits signals by

stimulating acupoints. Herbal medicines encompass various forms,

including decoctions, formulations, herbal extracts, and isolated

compounds, demonstrating a multi-targeted approach.

In the present review, potential natural medicines

for the treatment of AS, along with their efficacy and underlying

mechanisms were discussed. The underlying mechanisms of herbal

medicines, including formulations, herbs, and compounds derived

from herbs, have been identified as the reduction of inflammation,

oxidative stress, and abnormal osteogenesis in AS. Given that most

known drugs for AS exert anti-inflammatory effects, particularly

through the Th17 cell-mediated IL-23/IL-17 axis and TNF-α, various

responses to herbal medicines may contribute to inhibiting AS

progression. Furthermore, as identified in the present review, the

fact that most herbal medicines have a multi-targeting mechanism

suggests that this could be a key factor in treating AS, a disease

characterized by complex pathogenic mechanisms. In addition,

investigating the functional mechanisms of herbal medicines in

preclinical and clinical research is crucial for the development of

novel treatments for AS. Although numerous studies have explored

effective herbal medicines for AS, most are based on network

analyses, which only provide predictive results. One of the

difficulties in investigating AS is that it is not easy to collect

spinal specimens from patients. For this reason, AS animal models

are considered critical in research aimed at developing novel

treatments. Future studies are expected to focus on the discovery

of new herbal medicines for AS through large-scale preclinical

research, followed by clinical trials to validate their

efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present review article was supported by Woosuk

University.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

DYK and MHK conceived the study and supervised the

review. SYP, MSK, SS and LYC performed the literature search and

data collection. SYP and MSK wrote the first draft of the

manuscript, and all authors commented on previous versions of the

manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data authentication is not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Zhu W, He X, Cheng K, Zhang L, Chen D,

Wang X, Qiu G, Cao X and Weng X: Ankylosing spondylitis: Etiology,

pathogenesis, and treatments. Bone Res. 7(22)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Van Royen BJ and Dijkmans BAC (eds):

Ankylosing Spondylitis Diagnosis and Management. CRC Press,

2006.

|

|

3

|

Gouveia EB, Elmann D and de Ávila Morales

MS: Ankylosing spondylitis and uveitis: Overview. Rev Bras

Reumatol. 52:742–756. 2012.PubMed/NCBI(In English, Portuguese).

|

|

4

|

Zink A, Braun J, Listing J and Wollenhaupt

J: Disability and handicap in rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing

spondylitis-results from the German rheumatological database.

German collaborative arthritis centers. J Rheumatol. 27:613–622.

2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Landewe R, Dougados M, Mielants H, van der

Tempel H and van der Heijde D: Physical function in ankylosing

spondylitis is independently determined by both disease activity

and radiographic damage of the spine. Ann Rheum Dis. 68:863–867.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kim SH and Lee SH: Updates on ankylosing

spondylitis: Pathogenesis and therapeutic agents. J Rheum Dis.

30:220–233. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Pedersen SJ and Maksymowych WP: Beyond the

TNF-α inhibitors: New and emerging targeted therapies for patients

with axial spondyloarthritis and their relation to pathophysiology.

Drugs. 78:1397–1418. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Fiorillo MT, Haroon N, Ciccia F and Breban

M: Editorial: Ankylosing spondylitis and related immune-mediated

disorders. Front Immunol. 10(1232)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Arévalo M, Gratacós Masmitjà J, Moreno M,

Calvet J, Orellana C, Ruiz D, Castro C, Carreto P, Larrosa M,

Collantes E, et al: Influence of HLA-B27 on the ankylosing

spondylitis phenotype: Results from the REGISPONSER database.

Arthritis Res Ther. 20(221)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chen B, Li J, He C, Li D, Tong W, Zou Y

and Xu W: Role of HLA-B27 in the pathogenesis of ankylosing

spondylitis (Review). Mol Med Rep. 15:1943–1951. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Reveille JD: An update on the contribution

of the MHC to AS susceptibility. Clin Rheumatol. 33:749–757.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Baraliakos X, Heldmann F, Callhoff J,

Listing J, Appelboom T, Brandt J, Van den Bosch F, Breban M,

Burmester G, Dougados M, et al: Which spinal lesions are associated

with new bone formation in patients with ankylosing spondylitis

treated with anti-TNF agents? A long-term observational study using

MRI and conventional radiography. Ann Rheum Dis. 73:1819–1825.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Akkoc N, van der Linden S and Khan MA:

Ankylosing spondylitis and symptom-modifying vs disease-modifying

therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 20:539–557. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Perrotta FM, Scriffignano S, Ciccia F and

Lubrano E: Therapeutic targets for ankylosing spondylitis-recent

insights and future prospects. Open Access Rheumatol. 14:57–66.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Agrawal P, Tote S and Sapkale B: Diagnosis

and treatment of ankylosing spondylitis. Cureus.

16(e52559)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Moon KH and Kim YT: Medical treatment of

ankylosing spondylitis. Hip Pelvis. 26:129–135. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Dougados M and Baeten D:

Spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 377:2127–2137. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Vonkeman HE and van de Laar MAFJ:

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: Adverse effects and their

prevention. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 39:294–312. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Lindström U, Olofsson T, Wedrén S, Qirjazo

I and Askling J: Impact of extra-articular spondyloarthritis

manifestations and comorbidities on drug retention of a first

TNF-inhibitor in ankylosing spondylitis: A population-based

nationwide study. RMD Open. 4(e000762)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

van der Heijde D, Song IH, Pangan AL,

Deodhar A, van den Bosch F, Maksymowych WP, Kim TH, Kishimoto M,

Everding A, Sui Y, et al: Efficacy and safety of upadacitinib in

patients with active ankylosing spondylitis (SELECT-AXIS 1): A

multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase

2/3 trial. Lancet. 394:2108–2117. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Maksymowych WP: The role of imaging in the

diagnosis and management of axial spondyloarthritis. Nat Rev

Rheumatol. 15:657–672. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Sieper J and Poddubnyy D: Axial

spondyloarthritis. Lancet. 390:73–84. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Taurog JD, Chhabra A and Colbert RA:

Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med.

374:2563–2574. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Wordsworth BP, Cohen CJ, Davidson C and

Vecellio M: Perspectives on the genetic associations of ankylosing

spondylitis. Front Immunol. 12(603726)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Simone D, Al Mossawi MH and Bowness P:

Progress in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ankylosing

spondylitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 57 (Suppl 6):vi4–vi9.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Madden DR: The three-dimensional structure

of peptide-MHC complexes. Annu Rev Immunol. 13:587–622.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Bowness P: Hla-B27. Annu Rev Immunol.

33:29–48. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Lin H and Gong YZ: Association of HLA-B27

with ankylosing spondylitis and clinical features of the

HLA-B27-associated ankylosing spondylitis: A meta-analysis.

Rheumatol Int. 37:1267–1280. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Chatzikyriakidou A, Voulgari PV and Drosos

AA: What is the role of HLA-B27 in spondyloarthropathies? Autoimmun

Rev. 10:464–468. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

López de Castro JA: The HLA-B27 peptidome:

Building on the cornerstone. Arthritis Rheum. 62:316–319.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Colbert RA, Tran TM and Layh-Schmitt G:

HLA-B27 misfolding and ankylosing spondylitis. Mol Immunol.

57:44–51. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Colbert RA, DeLay ML, Layh-Schmitt G and

Sowders DP: HLA-B27 misfolding and spondyloarthropathies. Prion.

3:15–26. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lenart I, Guiliano DB, Burn G, Campbell

EC, Morley KD, Fussell H, Powis SJ and Antoniou AN: The MHC class I

heavy chain structurally conserved cysteines 101 and 164

participate in HLA-B27 dimer formation. Antioxid Redox Signal.

16:33–43. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Turner MJ, Sowders DP, DeLay ML, Mohapatra

R, Bai S, Smith JA, Brandewie JR, Taurog JD and Colbert RA: HLA-B27

misfolding in transgenic rats is associated with activation of the

unfolded protein response. J Immunol. 175:2438–2448.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Smith JA: Regulation of cytokine

production by the unfolded protein response; implications for

infection and autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 9(422)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kavadichanda CG, Geng J, Bulusu SN, Negi

VS and Raghavan M: Spondyloarthritis and the human leukocyte

antigen (HLA)-B*27 connection. Front Immunol.

12(601518)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Payeli SK, Kollnberger S, Marroquin

Belaunzaran O, Thiel M, McHugh K, Giles J, Shaw J, Kleber S, Ridley

A, Wong-Baeza I, et al: Inhibiting HLA-B27 homodimer-driven immune

cell inflammation in spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum.

64:3139–3149. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Antoniou AN, Lenart I and Guiliano DB:

Pathogenicity of misfolded and dimeric HLA-B27 molecules. Int J

Rheumatol. 2011(486856)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Zhang L, Zhang YJ, Chen J, Huang XL, Fang

GS, Yang LJ, Duan Y and Wang J: The association of HLA-B27 and

Klebsiella pneumoniae in ankylosing spondylitis: A

systematic review. Microb Pathog. 117:49–54. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Reveille JD: The genetic basis of

ankylosing spondylitis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 18:332–341.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Tsui FW, Haroon N, Reveille JD, Rahman P,

Chiu B, Tsui HW and Inman RD: Association of an ERAP1 ERAP2

haplotype with familial ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis.

69:733–736. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Chen B, Li D and Xu W: Association of

ankylosing spondylitis with HLA-B27 and ERAP1: Pathogenic role of

antigenic peptide. Med Hypotheses. 80:36–38. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Evans DM, Spencer CC, Pointon JJ, Su Z,

Harvey D, Kochan G, Oppermann U, Dilthey A, Pirinen M, Stone MA, et

al: Interaction between ERAP1 and HLA-B27 in ankylosing spondylitis

implicates peptide handling in the mechanism for HLA-B27 in disease

susceptibility. Nat Genet. 43:761–767. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Campbell EC, Fettke F, Bhat S, Morley KD

and Powis SJ: Expression of MHC class I dimers and ERAP1 in an

ankylosing spondylitis patient cohort. Immunology. 133:379–385.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Bowness P, Ridley A, Shaw J, Chan AT,

Wong-Baeza I, Fleming M, Cummings F, McMichael A and Kollnberger S:

Th17 cells expressing KIR3DL2+ and responsive to HLA-B27 homodimers

are increased in ankylosing spondylitis. J Immunol. 186:2672–2680.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Li Z and Brown MA: Progress of genome-wide

association studies of ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Transl

Immunology. 6(e163)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Rajalingam R: Human diversity of killer

cell immunoglobulin-like receptors and disease. Korean J Hematol.

46:216–228. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Yin Y, Wang M, Liu M, Zhou E, Ren T, Chang

X, He M, Zeng K, Guo Y and Wu J: Efficacy and safety of IL-17

inhibitors for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther.

22(111)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Schett G, Lories RJ, D'Agostino MA,

Elewaut D, Kirkham B, Soriano ER and McGonagle D: Enthesitis: From

pathophysiology to treatment. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 13:731–741.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Rezaiemanesh A, Abdolmaleki M,

Abdolmohammadi K, Aghaei H, Pakdel FD, Fatahi Y, Soleimanifar N,

Zavvar M and Nicknam MH: Immune cells involved in the pathogenesis

of ankylosing spondylitis. Biomed Pharmacother. 100:198–204.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Jain R, Chen Y, Kanno Y, Joyce-Shaikh B,

Vahedi G, Hirahara K, Blumenschein WM, Sukumar S, Haines CJ,

Sadekova S, et al: Interleukin-23-induced transcription factor

blimp-1 promotes pathogenicity of T helper 17 cells. Immunity.

44:131–142. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Garcia-Montoya L, Gul H and Emery P:

Recent advances in ankylosing spondylitis: Understanding the

disease and management. F1000Res. 7(F1000 Faculty

Rev-1512)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Sato K, Suematsu A, Okamoto K, Yamaguchi

A, Morishita Y, Kadono Y, Tanaka S, Kodama T, Akira S, Iwakura Y,

et al: Th17 functions as an osteoclastogenic helper T cell subset

that links T cell activation and bone destruction. J Exp Med.

203:2673–2682. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Babaie F, Hasankhani M, Mohammadi H,

Safarzadeh E, Rezaiemanesh A, Salimi R, Baradaran B and Babaloo Z:

The role of gut microbiota and IL-23/IL-17 pathway in ankylosing

spondylitis immunopathogenesis: New insights and updates. Immunol

Lett. 196:52–62. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Dong C: TH17 cells in development: An

updated view of their molecular identity and genetic programming.

Nat Rev Immunol. 8:337–348. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Mahmoudi M, Aslani S, Nicknam MH, Karami J

and Jamshidi AR: New insights toward the pathogenesis of ankylosing

spondylitis; genetic variations and epigenetic modifications. Mod

Rheumatol. 27:198–209. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Mei Y, Pan F, Gao J, Ge R, Duan Z, Zeng Z,

Liao F, Xia G, Wang S, Xu S, et al: Increased serum IL-17 and IL-23

in the patient with ankylosing spondylitis. Clin Rheumatol.

30:269–273. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Baeten D and Adamopoulos IE: IL-23

inhibition in ankylosing spondylitis: Where did it go wrong? Front

Immunol. 11(623874)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

El-Zayadi AA, Jones EA, Churchman SM,

Baboolal TG, Cuthbert RJ, El-Jawhari JJ, Badawy AM, Alase AA,

El-Sherbiny YM and McGonagle D: Interleukin-22 drives the

proliferation, migration and osteogenic differentiation of

mesenchymal stem cells: A novel cytokine that could contribute to

new bone formation in spondyloarthropathies. Rheumatology (Oxford).

56:488–493. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Lee EJ, Lee EJ, Chung YH, Song DH, Hong S,

Lee CK, Yoo B, Kim TH, Park YS, Kim SH, et al: High level of

interleukin-32 gamma in the joint of ankylosing spondylitis is

associated with osteoblast differentiation. Arthritis Res Ther.

17(350)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Chen B, Huang K, Ye L, Li Y, Zhang J,

Zhang J, Fan X, Liu X, Li L, Sun J, et al: Interleukin-37 is

increased in ankylosing spondylitis patients and associated with

disease activity. J Transl Med. 13(36)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Lin P, Bach M, Asquith M, Lee AY,

Akileswaran L, Stauffer P, Davin S, Pan Y, Cambronne ED, Dorris M,

et al: HLA-B27 and human β2-microglobulin affect the gut microbiota

of transgenic rats. PLoS One. 9(e105684)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Xu YY, Tan X, He YT, Zhou YY, He XH and

Huang RY: Role of gut microbiome in ankylosing spondylitis: an

analysis of studies in literature. Discov Med. 22:361–370.

2016.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

64

|

Di Vincenzo F, Del Gaudio A, Petito V,

Lopetuso LR and Scaldaferri F: Gut microbiota, intestinal

permeability, and systemic inflammation: A narrative review. Intern

Emerg Med. 19:275–293. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Thaiss CA, Zmora N, Levy M and Elinav E:

The microbiome and innate immunity. Nature. 535:65–74.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Berthelot JM and Claudepierre P:

Trafficking of antigens from gut to sacroiliac joints and spine in

reactive arthritis and spondyloarthropathies: Mainly through

lymphatics? Joint Bone Spine. 83:485–490. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Li C, Zhang Y, Yan Q, Guo R, Chen C, Li S,

Zhang Y, Meng J, Ma J, You W, et al: Alterations in the gut virome

in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Front Immunol.

14(1154380)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Symposium on Population Studies in

Relation to Chronic Rheumatic Diseases. Rome Ball J, Jeffrey MR and

Kellgren JH: Council for International Organizations of Medical

sciences, University of Manchester Department of Rheumatology: The

epidemiology of chronic rheumatism; Volume 2: Atlas of standard

radiographs of arthritis. Blackwell Scientific Publications,

Oxford, 1963.

|

|

69

|

Goie The HS, Steven MM, van der Linden SM

and Cats A: Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing

spondylitis: A comparison of the Rome, New York and modified New

York criteria in patients with a positive clinical history

screening test for ankylosing spondylitis. Br J Rheumatol.

24:242–249. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Ostergaard M and Lambert RG: Imaging in

ankylosing spondylitis. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis. 4:301–311.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Braun J, van den Berg R, Baraliakos X,

Boehm H, Burgos-Vargas R, Collantes-Estevez E, Dagfinrud H,

Dijkmans B, Dougados M, Emery P, et al: 2010 update of the

ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing

spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 70:896–904. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Uhrin Z, Kuzis S and Ward MM: Exercise and

changes in health status in patients with ankylosing spondylitis.

Arch Intern Med. 160:2969–2975. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Regnaux JP, Davergne T, Palazzo C, Roren

A, Rannou F, Boutron I and Lefevre-Colau MM: Exercise programmes

for ankylosing spondylitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

10(CD011321)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Kasapoglu Aksoy M, Birtane M, Taştekin N

and Ekuklu G: The effectiveness of structured group education on

ankylosing spondylitis patients. J Clin Rheumatol. 23:138–143.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Song IH, Poddubnyy DA, Rudwaleit M and

Sieper J: Benefits and risks of ankylosing spondylitis treatment

with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Arthritis Rheum.

58:929–938. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Bacchi S, Palumbo P, Sponta A and

Coppolino MF: Clinical pharmacology of non-steroidal

anti-inflammatory drugs: A review. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents

Med Chem. 11:52–64. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Gagliardi MC, Teloni R, Mariotti S,

Bromuro C, Chiani P, Romagnoli G, Giannoni F, Torosantucci A and

Nisini R: Endogenous PGE2 promotes the induction of human Th17

responses by fungal ß-glucan. J Leukoc Biol. 88:947–954.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Ward MM, Deodhar A, Akl EA, Lui A, Ermann

J, Gensler LS, Smith JA, Borenstein D, Hiratzka J, Weiss PF, et al:

American college of rheumatology/spondylitis association of

america/spondyloarthritis research and treatment network 2015

recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and

nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Care Res

(Hoboken). 68:151–166. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Wanders A, van der Heijde D, Landewé R,

Béhier JM, Calin A, Olivieri I, Zeidler H and Dougados M:

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs reduce radiographic progression

in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A randomized clinical

trial. Arthritis Rheum. 52:1756–1765. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

van der Heijde D, Ramiro S, Landewé R,

Baraliakos X, Van den Bosch F, Sepriano A, Regel A, Ciurea A,

Dagfinrud H, Dougados M, et al: 2016 update of the ASAS-EULAR

management recommendations for axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum

Dis. 76:978–991. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Ebrahimiadib N, Berijani S, Ghahari M and

Pahlaviani FG: Ankylosing spondylitis. J Ophthalmic Vis Res.

16:462–469. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Henderson C and Davis JC: Drug insight:

Anti-tumor-necrosis-factor therapy for ankylosing spondylitis. Nat

Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2:211–218. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

Schulz M, Dotzlaw H and Neeck G:

Ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis: Serum levels of

TNF-α and Its soluble receptors during the course of therapy with

etanercept and infliximab. Biomed Res Int.

2014(675108)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Gorman JD, Sack KE and Davis JC Jr:

Treatment of ankylosing spondylitis by inhibition of tumor necrosis

factor alpha. N Engl J Med. 346:1349–1356. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Toussirot É: Current therapeutics for

spondyloarthritis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 12:2469–2477.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Ranatunga S and Miller AV: Active axial

spondyloarthritis: Potential role of certolizumab pegol. Ther Clin

Risk Manag. 10:87–94. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Baraliakos X, Listing J, Fritz C, Haibel

H, Alten R, Burmester GR, Krause A, Schewe S, Schneider M, Sörensen

H, et al: Persistent clinical efficacy and safety of infliximab in

ankylosing spondylitis after 8 years-early clinical response

predicts long-term outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford). 50:1690–1699.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

van der Heijde D, Kivitz A, Schiff MH,

Sieper J, Dijkmans BA, Braun J, Dougados M, Reveille JD, Wong RL,