Prostate cancer (PCa) is a leading cause of

cancer-related deaths in men worldwide (1). As medical technology evolves,

approaches for treating PCa are being regularly refined (2). Metastatic castration-resistant PCa

(mCRPC) poses significant therapeutic challenge (3). Current treatment modalities, including

hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, show limited

effectiveness against mCRPC and frequently cause considerable

adverse effects (4). The

progression of metastatic PCa is influenced by multiple factors

such as tumor load, molecular traits, and resistance to therapies

(5).

Proteins located on the cell surface serve as

specific markers for tumors and are increasingly recognized as key

targets for targeted therapies in PCa (6). Research indicates that proteins such

as prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) are significantly

overexpressed in PCa cells, making them promising options for

targeted treatment (7). These

proteins play a role in tumor proliferation and spread, as well as

in mechanisms that allow tumors to evade the immune system

(8). Focusing on these surface

proteins can enhance treatment efficacy and minimize adverse

effects (9).

The shortcomings of conventional treatment

strategies have led to the development of targeted therapies.

Although chemotherapy and radiation therapy continue to play

crucial roles in PCa management, their effectiveness is frequently

hindered by variations within tumors and resistance to medications

(10). Recently, therapies that

focus on cell surface proteins have gained attention as innovative

treatment options (11). This

strategy not only targets particular cancer cells but also enhances

the precision of drug delivery and increases the availability of

medications in the body (12).

Consequently, the management of mCRPC must differ from that of

hormone-sensitive diseases (13,14),

necessitating personalized strategies that target specific cell

surface markers [such as PSMA and six-transmembrane epithelial

antigen 1 (STEAP1)] and often employ combination therapies to

overcome resistance (15-17).

This review aims to comprehensively outline the

advancements in targeted treatments associated with PCa cell

surface proteins, focusing on the underlying molecular processes,

therapeutic approaches, and their clinical relevance. By examining

various strategies for targeted therapy and their implementation in

clinical settings, it seeks to offer improved treatment

alternatives for patients with PCa and inform future research

pathways.

mCRPC represents a distinct and advanced stage of

PCa characterized by disease progression despite androgen

deprivation therapy (18). The

management of mCRPC necessitates a differentiated approach compared

to hormone-sensitive PCa due to its unique biological behavior,

resistance mechanisms, and therapeutic vulnerabilities (19). Key challenges in mCRPC include

persistent androgen receptor (AR) signaling, intratumoral

heterogeneity, adaptive immune evasion, and the emergence of

treatment-resistant clones (20).

Current standard therapies for mCRPC, including

novel hormonal agents (such as enzalutamide and abiraterone),

chemotherapies (for example docetaxel), and radiopharmaceuticals

(such as 177Lu-PSMA-617), have demonstrated survival

benefits (21). However, their

efficacy is often limited by primary or acquired resistance, which

is driven by AR alterations, neuroendocrine differentiation, and an

immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) (22).

Therapeutic differentiation in mCRPC involves

several key approaches: i) Molecular stratification based on

genomic alterations (for example BRCA1/2 and PTEN), AR variant

expression, and PSMA avidity (23);

ii) sequential and combination therapies that leverage synergistic

effects between AR-directed agents, radioligands, immunotherapies,

and targeted agents (24); and iii)

liquid biopsy and biomarker monitoring utilizing circulating tumor

cells (CTCs) and cell-free DNA to track clonal evolution and

treatment response (25). Emerging

evidence supports the integration of multi-omics profiling and

artificial intelligence (AI) to guide personalized therapy in

mCRPC, emphasizing the necessity for dynamic treatment adaptation

in response to evolving tumor biology (26).

PSMA is a glycoprotein that spans the cell membrane

and is predominantly found in PCa cells, especially in aggressive

forms, such as metastatic, poorly differentiated, and

castration-resistant variants, where its elevated presence often

correlates with increased tumor severity (27). Although normal tissues, including

parts of the urinary system and certain nerve tissues, exhibit

lower PSMA levels, PSMA is markedly overexpressed on cancer cell

surfaces (6). This overexpression

plays a crucial role in tumor cell growth and survival within the

TME, and possibly in promoting new blood vessel formation in

tumors. The distinct expression pattern of PSMA, characterized by

high levels in tumors and minimal expression in non-tumor tissues,

makes it a promising therapeutic target (6). Treatment with radiopharmaceuticals,

such as Lu-PSMA-617, can effectively destroy cancer cells while

sparing healthy tissue (28).

Additionally, PSMA is not exclusive to PCa cells; it is also

present in some newly formed blood vessels associated with tumors

(29). The use of radiolabeled

compounds, such as 68Ga-PSMA-11, enhances the diagnostic precision

for detecting metastatic cancer (30). However, PSMA expression shows

intra-and intertumoral heterogeneity, which may lead to varying

treatment responses (31). In

addition, its low expression in normal tissues, such as the

salivary glands and kidneys, may cause off-target toxicity,

requiring close monitoring during treatment (32).

STEAP1 is frequently overexpressed in PCa,

especially in advanced and metastatic forms, with >85% of

prostate tumors exhibiting this expression (33). By contrast, normal tissues show

minimal expression, highlighting their potential as significant

targets for therapy (34). This is

further supported by the link with biomarkers found in

STEAP1-positive extracellular vesicles, which can assist in both

diagnosis and prognosis (35). As a

cell surface antigen, STEAP1 plays a role in various aspects of

tumor development, including cell growth, migration, survival,

intercellular communication, and metal metabolism (36). It also enhances tumor cell functions

through pathways such as PI3K/Akt and is linked to aggressive

characteristics such as invasion and metastasis (37). Previous research on PCa models have

demonstrated that STEAP1 exerts antitumor effects when used in

chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cell therapy (38). When combined with localized IL-12

therapy, it was shown to improve treatment effectiveness by

modifying the TME and countering antigen escape (29). Moreover, clinical trials are being

conducted using STEAP1-targeted T-cell inducers and antibody-drug

conjugates (ADCs) (39). In

summary, STEAP1 is a promising target in PCa; however, its

expression dynamics in advanced cancer and association with metal

metabolism need to be further elucidated.

Additional important proteins on cell surfaces

include trophoblast cell-surface antigen 2 (TROP-2), a

transmembrane protein frequently found at elevated levels in

various cancers, including PCa, making it a promising candidate for

ADCs (40). Ongoing clinical trials

are assessing the effectiveness of sacituzumab-govitecan in

treating urothelial carcinoma and PCa, with supportive evidence of

its anticancer properties emerging from animal studies (41). Likewise, prostate stem cell antigen

(PSCA) is present in ~90% of PCa cases and is associated with tumor

aggressiveness, leading to the development of targeted

immunotherapies such as CAR-T cells and ADCs (42). Nonetheless, obstacles such as the

immunosuppressive nature of the TME, potential off-target effects,

and variability in expression levels may pose challenges (43). Furthermore, delta-like ligand 3

(DLL3) is overexpressed in neuroendocrine PCa (NEPC), linking it to

tumor severity and patient prognosis (44). Monoclonal antibodies and

radioimmunotherapy, including 177Lu-labeled antibodies, have

demonstrated preclinical promise. However, concerns regarding their

expression in non-neuroendocrine tumors and patient variability

must be resolved (45). In

addition, emerging targets, such as cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass

G-type receptor 3 (CELSR3) and glypican-3 (GPC3), have also

attracted attention. CELSR3 is highly expressed in NEPC and is

involved in the regulation of cell polarity and migration through

the Wnt/PCP signaling pathway; its overexpression is associated

with tumor invasiveness. Research has explored its potential as a

target for CAR-T cells and ADC (46). GPC3 is upregulated in

castration-resistant PCa and promotes tumor growth by regulating

the Hh signaling pathway. Preclinical studies have shown that

GPC3-targeting antibodies can inhibit tumor progression, and phase

I clinical trials are underway (47) (Table

I).

The drug 177Lu-PSMA-617 is a radioligand used for

mCRPC that targets PSMA to deliver the radioactive isotope 177Lu

directly to cancer cells, leading to their destruction (48). Findings from the VISION trial

indicated that it notably enhanced both overall survival and

quality of life in patients, and its favorable tolerability has

established it as a standard treatment for mCRPC (49). Currently, there is growing interest

in exploring novel radioactive isotopes, such as 161Tb-PSMA, which

may offer promising avenues for combination therapies (50). Clinical studies have demonstrated

the safety and effectiveness of 161Tb-PSMA, suggesting that its use

along with 177Lu-PSMA-617 could potentially amplify therapeutic

outcomes (51). Overall,

radioligand therapy (RLT), such as 177Lu-PSMA-617, has been

demonstrated to significantly improve survival in patients with

mCRPC; however, drug resistance and heterogeneous expression remain

major challenges.

ADCs are designed to transport cytotoxic medications

directly to cancer cells using antibodies that specifically attach

to tumor antigens (52). This

targeted approach enhances the therapeutic effectiveness while

minimizing harm to healthy tissues (53). PSMA is recognized as a

well-established therapeutic target that facilitates efficient

delivery of ADCs. Clinical studies have indicated favorable results

and manageable side effects in patients with mCRPC, including a 50%

or more reduction in prostate-specific antigen levels during

second-line treatments, along with some instances of complete

responses (54). Additionally,

TROP-2, which is prominently expressed in metastatic PCa and linked

to poor prognosis, represents another significant target for ADCs,

showing encouraging clinical results (40). In contrast to conventional

chemotherapy, the targeted nature of ADCs mitigates widespread

toxicity and drug resistance (55).

ADCs achieve precise delivery; however, the internalization

efficiency of the target, linker stability, and off-target toxicity

limit their widespread applications.

BiTEs are designed to bind both tumor-specific

antigens and CD3 receptors on T cells, thereby effectively linking

T cells to cancer cells (56). This

connection not only activates T cells to kill tumor cells but also

facilitates the direct destruction of the tumor. For instance, AMG

160, which targets PSMA, elicits cytotoxic effects in PCa, whereas

BiTEs that target STEAP1 further improve therapeutic outcomes

(57). In addition to their direct

effects on tumors, BiTEs enhance the immune response against cancer

by promoting the release of cytokines from activated T cells,

which, in turn, activate nearby immune cells (58). Although the combination of BiTEs

with immune checkpoint inhibitors has the potential to address the

immunosuppressive environments found in ‘cold tumors’, such as PCa,

their application in clinical settings is hindered by issues such

as cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and other immune-related adverse

effects (irAEs) (59). BiTEs

activate T cells with strong cytotoxic effects; however, CRS and

neurotoxicity limit their clinical application.

CAR-T cell therapy is a groundbreaking

immunotherapeutic approach. Preclinical research has demonstrated

that CAR-T cells targeting the STEAP1 antigen in PCa cells can

effectively identify and eliminate tumor cells (60). Additionally, CAR-T therapy targeting

PSMA has been proven effective in patients with metastatic disease.

Studies conducted in vitro and in animal models revealed

enhanced anti-tumor properties, particularly when combined with

chemotherapy agents (60,61). Nonetheless, obstacles, such as the

immunosuppressive nature of the TME and the mechanisms of antigen

escape, hinder their overall effectiveness, leading to the

exploration of dual CAR-T cells paired with IL-23 antibodies to

enhance their proliferation and functionality (62). NEPC is a particularly aggressive

variant that poses distinct treatment challenges owing to the

presence of specific antigens. CAR-T cells targeting

carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 5 have

shown significant cytotoxic potential in preclinical studies,

thereby addressing some of the shortcomings of traditional

therapies (63). Although CAR-T has

made breakthroughs in hematologic tumors, its efficacy is limited

in solid tumors such as PCa, mainly due to: i) Immunosuppressive

cells [such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)] and

factors (such as TGF-β) in the TME inhibiting T-cell function

(64); ii) physical barriers such

as fibrotic stroma hindering T-cell infiltration (65); and iii) antigen heterogeneity

leading to antigen escape (66). By

contrast, hematological tumors often exhibit more uniform antigen

expression and a less immunosuppressive microenvironment, which

facilitates the efficacy of CAR-T therapy (67). CAR-T cells exhibit potential in PCa,

however the obstacles presented by the solid TME and antigen escape

limit their efficacy, requiring combined strategies to overcome

this bottleneck.

BiTEs and CAR-T cells are both T cell-directed

therapies; however, each has advantages and disadvantages. BiTEs

are easy to prepare, act quickly, and can be easily combined with

immune checkpoint inhibitors (57);

however, they have a short half-life and require continuous

infusion, and the risk of CRS is high (59). Although CAR-T is durable and can

expand in vivo, it is complex to prepare, costly, and easily

inhibited by the TME in solid tumors (62,65).

In summary, BiTEs offer a cost-effective, rapid response option for

short-term intervention, whereas CAR-T therapy provides durable,

personalized control, but faces manufacturing and TME challenges in

PCa. The choice should be guided by treatment goals and

patient-specific factors.

The use of nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems,

which include functionalized nanoparticles, such as gold and

polymeric carriers, allows for the precise targeting of cancer

cells that express PSMA (68). This

approach significantly improves drug bioavailability and can

decrease systemic toxicity by 50-70% (68). These systems enhance the solubility

and circulation duration of drugs, encourage tumor-specific

accumulation to enhance effectiveness, and minimize side effects,

while enabling treatment response monitoring through imaging

methods (69). Furthermore,

ultrasound-responsive nanocarriers are effective in delivering

small interfering RNA to suppress gene expression in PCa cells

(70). Nonetheless, the transition

to clinical applications encounters obstacles, such as

biocompatibility, immune reactions, and mechanisms of drug

resistance. Nanocarriers enhance drug targeting and

bioavailability; however, biocompatibility, immunogenicity, and

large-scale production are challenges for translation.

Different treatment strategies have distinct

advantages and disadvantages. RLT (such as 177Lu-PSMA-617) has a

high response rate in PSMA-high-expressing mCRPC but may cause

myelosuppression (71); ADCs have

strong targeting but carry the risk of off-target toxicity

(72); BiTEs activate T cells

rapidly but can easily lead to cytokine release syndrome (73); and CAR-T therapy has been successful

in hematologic neoplasms but is limited in solid tumors such as PCa

owing to TME suppression, resulting in limited efficacy (74). Longitudinal comparisons showed that

both BiTEs and CAR-T cells are T cell-directed therapies, but BiTEs

are cost-effective, quick to deploy, and suitable for short-term

interventions, while CAR-T modifications are durable but complex to

manufacture, making them more suitable for individualized long-term

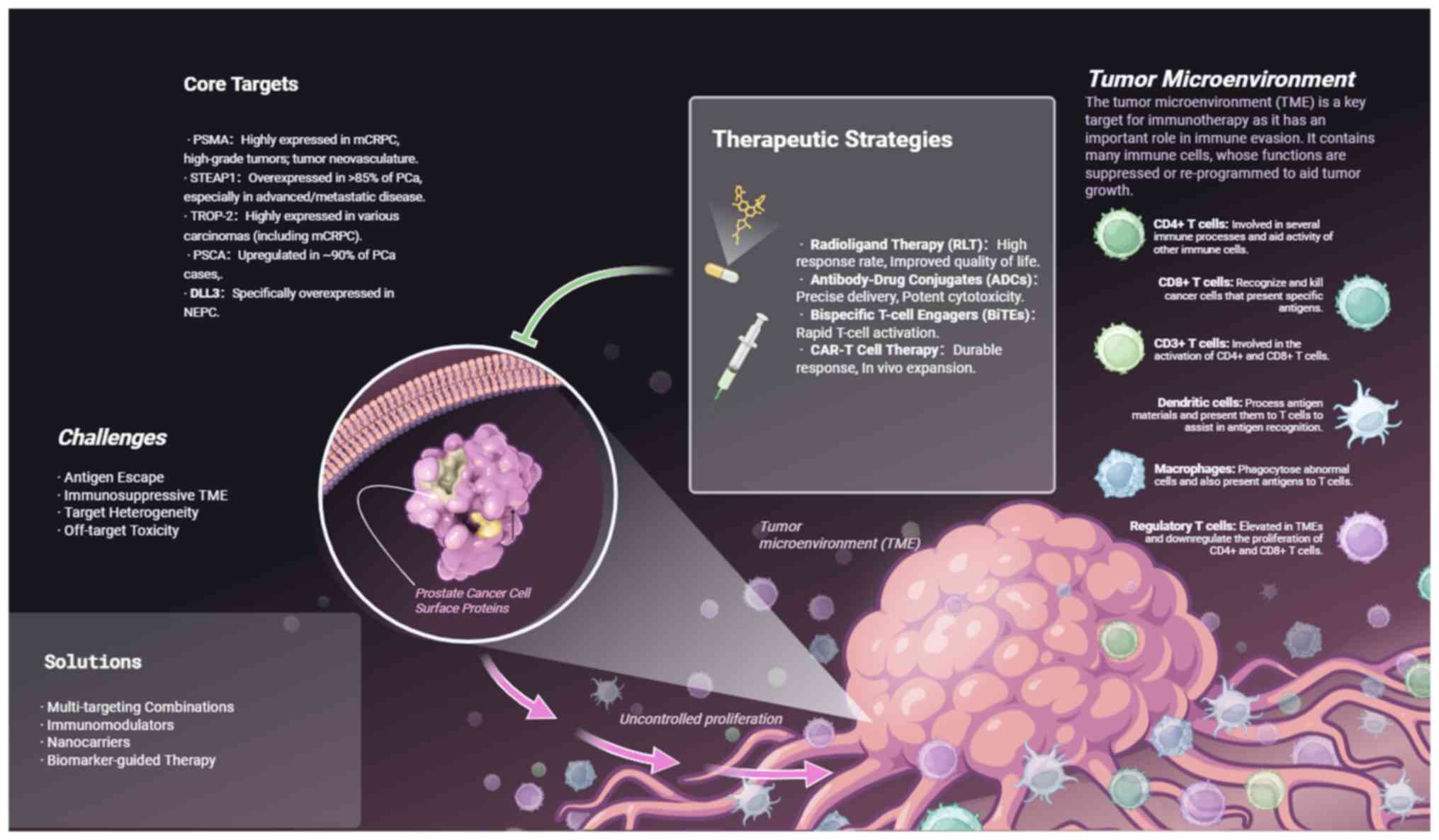

treatment (75) (Fig. 1).

The reduction in antigen expression and the

phenomenon of antigen escape are significant factors in how tumor

cells avoid detection by the immune system (76). This downregulation is often

associated with various strategies employed by tumor cells to

elicit immune responses. In PCa cells, the levels of PSMA and

similar antigens frequently decrease due to factors such as genetic

alterations, epigenetic modifications, and the effects of the TME

(77). Lower PSMA expression can

lead to a diminished response to immunotherapy, allowing tumor

cells to evade immune monitoring (78). Furthermore, decreased antigen

expression can hinder T-cell activation, thus impairing the overall

immune response (79). Research

indicates that antigen escape is intricately linked to the

heterogeneity of tumor cells, where variations in antigen

expression among different tumor cells contribute to the complexity

and variability of immune responses against tumors (80). To cope with antigen downregulation,

multitarget CAR-T cells (such as PSMA and STEAP1) or combined

epigenetic regulators (such as HDAC inhibitors) can be used to

stabilize antigen expression (81,82).

The diversity of PCa tumors significantly

contributes to their ability to evade the immune system (83). Within PCa, various tumor cell

subtypes may exhibit resistance to immunotherapy, whereas others

respond positively to such treatments (84). This variability leads to differences

in antigen expression, enabling some tumor cells to avoid immune

detection by reducing or completely losing expression of crucial

antigens (85). Additionally,

elements within the TME that inhibit immune function, including

tumor-associated macrophages and MDSCs, further facilitate the

immune evasion of these tumor cells, intensifying the heterogeneity

of the tumors (86-88).

Consequently, investigating combination therapies aimed at

enhancing immune responses and improving treatment effectiveness

against tumors is critically important (89).

Management of the immunosuppressive tumor

environment is a crucial focus in PCa research. Factors associated

with tumor-induced immunosuppression, such as S100A4, play a

significant role in the initiation and progression of PCa (90). This protein is elevated in numerous

tumors and is associated with unfavorable outcomes in patients with

PCa (91). The use of anti-S100A4

antibodies could potentially counteract this immunosuppressive

effect in PCa, leading to improved treatment responses (92). Targeting S100A4 with anti-S100A4

antibodies may effectively reverse the immunosuppressive state of

PCa, thereby improving patient response rates to treatment

(90). The combination of

immunomodulatory approaches and targeted therapies has great

potential. For example, YY001, a novel EP4 antagonist, is vital for

shaping the immune landscape of PCa (93). Research indicates that YY001 can

reduce the differentiation and activity of MDSCs, while promoting

T-cell growth and antitumor functions (93). By modulating cytokine and chemokine

levels, YY001 can effectively restore a more favorable immune

environment within tumors, functioning synergistically with

anti-PD-1 antibodies to significantly enhance antitumor immune

activity (93). The effectiveness

of this combined approach highlights the potential of integrating

immunomodulatory and targeted therapies for PCa treatment.

The combination and evaluation of multi-omics

information, including genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics,

have enabled the discovery of novel biomarkers and treatment

targets for PCa (101). Notably,

mutations in genes such as BRCA1/2 are significantly linked to

patient outcomes. Treatments targeting these mutations, such as

PARP, have demonstrated efficacy (102). Molecular subtyping allows for the

identification of high-risk patients and enhances the likelihood of

successful treatment outcomes. Advanced AI techniques, such as deep

and machine learning, aid in the accurate analysis of biomarkers

and refinement of personalized treatment strategies (103). In addition, tracking CTCs is

essential. The number of CTCs and the expression of surface

proteins (such as PSMA and STEAP1) can indicate tumor severity,

prognosis, and response to therapy (104), whereas liquid biopsy methods can

efficiently isolate CTCs for ongoing clinical assessment (105). The management of mCRPC should be

individualized based on several key factors, including i) tumor

burden and metastatic sites; ii) expression levels of cell surface

targets (such as PSMA PET/CT standardized uptake value); iii)

genome characteristics (such as DNA repair defects); and iv) prior

treatment history (106-108).

Studies have shown that PSMA-targeted therapy can achieve a

response rate of 60-70% in patients with mCRPC and high PSMA

expression, while the effect is limited in patients with low

expression, emphasizing the importance of target assessment before

treatment (109-111).

Investigation of innovative surface proteins,

including CELSR3, which is notably overexpressed in NEPC, is

crucial for controlling cell growth and movement (46). Additionally, GPC3, which is linked

to tumor aggressiveness, opens up new possibilities for the

targeted treatment of PCa. CAR-T cells targeting CELSR3 have

demonstrated significant tumor-suppressive activity in

patient-derived xenograft models (37), while GPC3-targeted ADCs showed

promising results in phase I trials for liver cancer, and its trial

for PCa has been initiated (112).

Concurrently, gene therapy-utilizing carriers, such as

poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles, can effectively

transport nucleic acid medications aimed at PSMA (47). Treatment efficacy can be enhanced by

employing a multifaceted approach that influences tumor dynamics

and encourages immune cell infiltration (113). Advances in nanotechnology have

enabled the development of immunotherapies. Functionalized

nanoparticles can transport immunomodulatory agents and checkpoint

inhibitors directly to tumor locations, enhancing biodistribution

and facilitating synergistic combination therapies through the

simultaneous delivery of various therapeutic compounds (114). Multi-omics and AI technologies

drive individualized therapy; however, target validation, biomarker

standardization, and clinical trial design remain key to achieving

precision medicine.

In the context of targeted therapy for PCa, a major

challenge in choosing PSMA is the heterogeneity of the targets

(115). Differences in PSMA

expression across various tumor types and their microenvironments

result in notable variations in treatment effectiveness among

individuals (116). To address

this heterogeneity, multimodal imaging (such as PSMA-PET/MRI) can

be used to assess target expression and develop bispecific

antibodies that simultaneously target both PSMA and STEAP1. Beyond

this heterogeneity, there is the potential for unintended toxicity

that can harm non-target tissues (117). This issue can be mitigated by the

use of functionalized nanoparticles and targeted ligands, which

improve the precision of therapeutic agents (118). By utilizing tumor-targeting

peptides in conjunction with nanoparticles, selective absorption of

cancer drugs can be achieved, whereas biocompatible carriers help

minimize systemic toxicity and ensure accurate delivery to PCa

cells (119).

Immunotherapy can result in a range of irAEs when

treating PCa and other urological malignancies, including mild

symptoms such as rashes and fatigue as well as serious conditions

such as endocrine dysfunction and potentially fatal pneumonia

(120). Consequently, it is

crucial to promptly recognize these issues through consistent

monitoring of symptoms and patient feedback (121). Management approaches involve

providing symptomatic relief for less severe cases and

administering immunosuppressive medications, including steroids, to

patients with moderate-to-severe irAEs, alongside patient education

(122,123). Similarly, CAR-T cell therapy

demonstrates promising effectiveness but requires rigorous safety

oversight to monitor adverse reactions such as CRS and

neurotoxicity (124). This

requires ongoing evaluation of vital signs and neurological health,

offering symptomatic care and tocilizumab when appropriate and a

thorough pretreatment assessment to identify risk factors (125). In future, priority should be given

to exploring the dynamic expression patterns of targets, the

mechanisms of immunotoxicity, and the establishment of predictive

models to optimize the treatment window.

Advancements in targeted therapies for PCa cell

surface proteins, including PSMA, STEAP1, and TROP-2, have

significantly improved the management of mCRPC. Innovative

approaches such as RLT (including 177Lu-PSMA-617), ADCs, bispecific

antibodies, and CAR-T cell therapy have demonstrated promising

results. Nonetheless, challenges, such as antigen escape,

immunosuppressive environments, and drug resistance, persist.

Addressing these issues requires the development of combination

therapies, including targeted drug pairings and the integration of

RLT with immunotherapy, alongside personalized treatments informed

by biological markers, such as genomic characteristics and CTC

analysis. Future research should focus on the following directions:

i) Elucidating the molecular mechanisms of antigen escape,

particularly the roles of epigenetic regulation and TME-mediated

immune suppression. ii) Prioritizing the clinical evaluation of

combination strategies, such as RLT (for example 177Lu-PSMA-617)

and immune checkpoint inhibitors (including anti-PD-1). iii)

Accelerating the translational development of therapies against

emerging targets (such as CELSR3- and GPC3-directed ADCs or CAR-T

cells). iv) Developing integrated biomarker panels (for example

combining ctDNA, CTCs, and radiomics) and standardizing toxicity

management guidelines to improve patient quality of life. By

fostering interdisciplinary collaboration to expedite the clinical

application of novel therapies, targeted PCa treatment can advance

to a more precise and effective era.

Not applicable.

Funding: The present review was funded by the Medical Research

Project of Sichuan Medical Association (grant no. S2024047).

Not applicable.

HL conceived and designed the review, drafted the

manuscript, as well as read and approved the final mansucript. Data

authentication is not applicable.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

The author declares that he has no competing

interests.

|

1

|

Pullen RL Jr and Holter V: Nursing

management of a patient with prostate cancer. Nursing. 55:25–35.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Campodonico F, Ennas M, Zanardi S, Zigoura

E, Piccardo A, Foppiani L, Schiavone C, Squillace L, Benelli A, De

Censi A, et al: Management of prostate cancer with systemic

therapy: A prostate cancer unit perspective. Curr Cancer Drug

Targets. 21:107–116. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Henriques V, Wenzel M, Demes MC and

Köllermann J: Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.

Pathologe. 42:431–441. 2021.(In German).

|

|

4

|

Heck MM, Tauber R, Schwaiger S, Retz M,

D'Alessandria C, Maurer T, Gafita A, Wester H, Gschwend JE, Weber

WA, et al: Treatment outcome, toxicity, and predictive factors for

radioligand therapy with 177Lu-PSMA-I&T in metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 75:920–926.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

von Amsberg G, Busenbender T, Coym A,

Kaune M, Strewinsky N, Ekrutt J, Tilki D and Dyshlovoy S:

Management of metastatic prostate cancer. Oncol Res Treat. 8:1–12.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Nezir AE, Khalily MP, Gulyuz S, Ozcubukcu

S, Küçükgüzel SG, Yilmaz O and Telci D: Synthesis and evaluation of

tumor-homing peptides for targeting prostate cancer. Amino Acids.

53:645–652. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kumar BV, Sachan R, Garad P, Srivastava N,

Saraf SA and Meher N: Dual targeting of prostate-specific membrane

antigen and fibroblast activation protein: Bridging prostate cancer

theranostics with precision. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 8:962–979.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Liu C, Chen S, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Wang H,

Wang Q and Lan X: Mechanisms of Rho GTPases in regulating tumor

proliferation, migration and invasion. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.

80:168–174. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Wang J, Zhu J, Meng J, Qiu T, Wang W, Wang

R and Liu J: Baicalin inhibits biofilm formation by influencing

primary adhesion and aggregation phases in Staphylococcus

saprophyticus. Vet Microbiol. 262(109242)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Du X, Zhang Y, Jia Y and Gao B: The

Development of Al18F-NOTA-FAP-2286 as an FAP-Targeted PET tracer

and the translational application in the diagnosis of acquired drug

resistance in progressive prostate cancer. Pharmaceutics.

17(552)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Grewal K, Dorff TB, Mukhida SS, Agarwal N

and Hahn AW: Advances in targeted therapy for metastatic prostate

cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 26:465–475. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhao Q, Mo Z, Zeng L, Yuan Y and Wang Y

and Wang Y: Construction and evaluation of hepatic targeted drug

delivery system with hydroxycamptothecin in stem cell-derived

exosomes. Molecules. 29(5174)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Fan L, Gong Y, He Y, Gao W, Dong X, Dong

B, Zhu HH and Xue W: TRIM59 is suppressed by androgen receptor and

acts to promote lineage plasticity and treatment-induced

neuroendocrine differentiation in prostate cancer. Oncogene.

42:559–571. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Archer M, Lin KM, Kolanukuduru KP, Zhang

J, Ben-David R, Kotula L and Kyprianou N: Impact of cell plasticity

on prostate tumor heterogeneity and therapeutic response. Am J Clin

Exp Urol. 12:331–351. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Abida W, Beltran H and Raychaudhuri R:

State of the Art: Personalizing treatment for patients with

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol

Educ Book. 245(e473636)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Xu J, Ma Y, Hu P, Yao J, Chen H and Ma Q:

Recent advances in antibody-drug conjugates for metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi

Xue Ban. 54:685–693. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

|

|

17

|

Mulati Y, Shen Q, Tian Y, Chen Y, Yao K,

Yu W, Cui Y, Shi X, He Z, Zhang Q and Fan Y: Characterizing PSMA

heterogeneity in prostate cancer and identifying clinically

actionable tumor associated antigens in PSMA negative cases. Sci

Rep. 15(23902)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Horak J, Petrausch U and Omlin A:

Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer-what are rational

sequential treatment options? Urologie. 62:1295–1301.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In German).

|

|

19

|

Davis ID: Combination therapy in

metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer: Is three a crowd?

Ther Adv Med Oncol. 14(17588359221086827)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Reichert ZR and Hussain M: Androgen

receptor and beyond, targeting androgen signaling in

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer J. 22:326–329.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Li PY, Lu YH and Chen CY: Comparative

effectiveness of abiraterone and enzalutamide in patients with

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer in Taiwan. Front

Oncol. 12(822375)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Blanc C, Moktefi A, Jolly A, de la Grange

P, Gay D, Nicolaiew N, Semprez F, Maillé P, Soyeux P, Firlej V, et

al: The Neuropilin-1/PKC axis promotes neuroendocrine

differentiation and drug resistance of prostate cancer. Br J

Cancer. 128:918–927. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Russnes HG, Lingjærde OC, Børresen-Dale AL

and Caldas C: Breast cancer molecular stratification: From

intrinsic subtypes to integrative clusters. Am J Pathol.

187:2152–2162. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Saeed F, Berchuck JE, Bilen MA, Gandhi JS,

Nazha B, Brown JT, Schuster DM, Jani AB, Yu J and Harik LR:

Optimizing treatment for metastatic castration-resistant prostate

cancer: Food and Drug Administration-approved therapies, emerging

strategies, and biomarker-driven approaches. Cancer.

131(e70037)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hollanda CN, Gualberto ACM, Motoyama AB

and Pittella-Silva F: Advancing leukemia management through liquid

biopsy: Insights into biomarkers and clinical utility. Cancers

(Basel). 17(1438)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu HH, Tsai YS, Lai CL, Tang CH, Lai CH,

Wu HC, Hsieh JT and Yang CR: Evolving personalized therapy for

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Biomedicine (Taipei).

4(2)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Adnan A and Basu S: PSMA Receptor-Based

PET-CT: The basics and current status in clinical and research

applications. Diagnostics (Basel). 13(158)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ramnaraign B and Sartor O: PSMA-targeted

radiopharmaceuticals in prostate cancer: Current data and new

trials. Oncologist. 28:392–401. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Rowe SP, Gorin MA and Pomper MG: Imaging

of prostate-specific membrane antigen with small-molecule PET

radiotracers: From the bench to advanced clinical applications.

Annu Rev Med. 70:461–477. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Ali H, Rashid Ul Amin S, Hai A and Nizar

N: Bony lesion analysis in carcinoma prostate: Methylene

diphosphonate bone scan vs. Gallium-68 psma-11 pet/ct. J Ayub Med

Coll Abbottabad. 35:415–418. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Zhang M, Li Y, Quan Z, Zhou X, Meng X, Ye

J, Wang Y, Wang J, Qin W, Wang J and Kang F: Value of [68Ga]

Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT in reflecting the intra- and intertumor

heterogeneity of neovascularization in clear cell renal cell

carcinoma. Mol Pharm. 22:1529–1538. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Alaskarov A, Barel S, Bakavayev S, Kahn J

and Israelson A: MIF homolog d-dopachrome tautomerase (D-DT/MIF-2)

does not inhibit accumulation and toxicity of misfolded SOD1. Sci

Rep. 12(9570)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Ihlaseh-Catalano SM, Drigo SA, de Jesus

CM, Domingues MA, Trindade Filho JC, de Camargo JL and Rogatto SR:

STEAP1 protein overexpression is an independent marker for

biochemical recurrence in prostate carcinoma. Histopathology.

63:678–685. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Uemura H, Nakagawa Y, Yoshida K, Saga S,

Yoshikawa K, Hirao Y and Oosterwijk Y: MN/CA I X/G250 as a

potential target for immunotherapy of renal cell carcinomas. Br J

Cancer. 81:741–746. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Khanna K, Salmond N, Lynn KS, Leong HS and

Williams KC: Clinical significance of STEAP1 extracellular vesicles

in prostate cancer. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 24:802–811.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Oosterheert W and Gros P: Cryo-electron

microscopy structure and potential enzymatic function of human

six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of the prostate 1 (STEAP1). J

Biol Chem. 295:9502–9512. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Li YJ, Wang Y and Wang YY: MicroRNA-99b

suppresses human cervical cancer cell activity by inhibiting the

PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 234:9577–9591.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Bhatia V, Kamat NV, Pariva TE, Wu LT, Tsao

A, Sasaki K, Sun H, Javier G, Nutt S, Coleman I, et al: Targeting

advanced prostate cancer with STEAP1 chimeric antigen receptor T

cell and tumor-localized IL-12 immunotherapy. Nat Commun.

14(2041)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Thorne AH, Malo KN, Wong AJ, Nguyen TT,

Cooch N, Reed C, Yan J, Broderick KE, Smith TRF, Masteller EL and

Humeau L: Adjuvant screen identifies synthetic DNA-Encoding Flt3L

and CD80 immunotherapeutics as candidates for enhancing anti-tumor

T cell responses. Front Immunol. 11(327)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Sperger JM, Helzer KT, Stahlfeld CN, Jiang

D, Singh A, Kaufmann KR, Niles DJ, Heninger E, Rydzewski NR, Wang

L, et al: Expression and therapeutic targeting of TROP-2 in

treatment-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 29:2324–2335.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Bardia A, Messersmith WA, Kio EA, Berlin

JD, Vahdat L, Masters GA, Moroose R, Santin AD, Kalinsky K, Picozzi

V, et al: Sacituzumab govitecan, a Trop-2-directed antibody-drug

conjugate, for patients with epithelial cancer: Final safety and

efficacy results from the phase I/II IMMU-132-01 basket trial. Ann

Oncol. 32:746–756. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Matera L: The choice of the antigen in the

dendritic cell-based vaccine therapy for prostate cancer. Cancer

Treat Rev. 36:131–41. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Chen L, Chen F, Niu H, Li J, Pu Y, Yang C,

Wang Y, Huang R, Li K, Lei Y and Huang Y: Chimeric antigen receptor

(CAR)-T cell immunotherapy against thoracic malignancies:

Challenges and opportunities. Front Immunol.

13(871661)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Puca L, Gavyert K, Sailer V, Conteduca V,

Dardenne E, Sigouros M, Isse K, Kearney M, Vosoughi A, Fernandez L,

et al: Delta-like protein 3 expression and therapeutic targeting in

neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Sci Transl Med.

11(eaav0891)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Mohsin H, Jia F, Sivaguru G, Hudson MJ,

Shelton TD, Hoffman TJ, Cutler CS, Ketring AR, Athey PS, Simón J,

et al: Radiolanthanide-labeled monoclonal antibody CC49 for

radioimmunotherapy of cancer: Biological comparison of DOTA

conjugates and 149Pm, 166Ho, and 177Lu. Bioconjug Chem. 17:485–492.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Van Emmenis L, Ku SY, Gayvert K, Branch

JR, Brady NJ, Basu S, Russell M, Cyrta J, Vosoughi A, Sailer V, et

al: The identification of CELSR3 and other potential cell surface

targets in neuroendocrine prostate cancer. Cancer Res Commun.

3:1447–1459. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Hong S, Jeong SH, Han JH, Yuk HD, Jeong

CW, Ku JH and Kwak C: Highly efficient nucleic acid encapsulation

method for targeted gene therapy using antibody conjugation system.

Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 35(102322)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Patell K, Kurian M, Garcia JA, Mendiratta

P, Barata PC, Jia AY, Spratt DE and Brown JR: Lutetium-177 PSMA for

the treatment of metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer: A

systematic review. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 23:731–744.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Fallah J, Agrawal S, Gittleman H, Fiero

MH, Subramaniam S, John C, Chen W, Ricks TK, Niu G, Fotenos A, et

al: FDA approval summary: Lutetium Lu 177 Vipivotide tetraxetan for

patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin

Cancer Res. 29:1651–1657. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Tschan VJ, Busslinger SD, Bernhardt P,

Grundler PV, Zeevaart JR, Köster U, van der Meulen NP, Schibli R

and Müller C: Albumin-binding and conventional PSMA ligands in

combination with 161Tb: Biodistribution, dosimetry, and preclinical

therapy. J Nucl Med. 64:1625–1631. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Buteau JP, Kostos L, Jackson PA, Xie J,

Haskali MB, Alipour R, McIntosh LE, Emmerson B, MacFarlane L,

Martin CA, et al: First-in-human results of terbium-161 [161Tb]

Tb-PSMA-I&T dual beta-Auger radioligand therapy in patients

with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (VIOLET): A

single-centre, single-arm, phase 1/2 study. Lancet Oncol.

26:1009–1017. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Mark C, Lee JS, Cui X and Yuan Y:

Antibody-drug conjugates in breast cancer: Current status and

future directions. Int J Mol Sci. 24(13726)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Wang Y, Li G, Wang H, Qi Q, Wang X and Lu

H: Targeted therapeutic strategies for Nectin-4 in breast cancer:

Recent advances and future prospects. Breast.

79(103838)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Nguyen H, Hird K, Cardaci J, Smith S and

Lenzo NP: Lutetium-177 Labelled Anti-PSMA monoclonal antibody

(Lu-TLX591) Therapy for metastatic prostate cancer: Treatment

toxicity and outcomes. Mol Diagn Ther. 28:291–299. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Yassin MT, Al-Otibi FO, Al-Sahli SA,

El-Wetidy MS and Mohamed S: Metal oxide nanoparticles as efficient

nanocarriers for targeted cancer therapy: Addressing

chemotherapy-induced disabilities. Cancers (Basel).

16(4234)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Huang C, Duan X, Wang J, Tian Q, Ren Y,

Chen K, Zhang Z, Li Y, Feng Y, Zhong K, et al: Lipid nanoparticle

delivery system for mRNA encoding B7H3-redirected bispecific

antibody displays potent antitumor effects on malignant tumors. Adv

Sci (Weinh). 10(e2205532)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Deegen P, Thomas O, Nolan-Stevaux O, Li S,

Wahl J, Bogner P, Aeffner F, Friedrich M, Liao MZ, Matthes K, Rau

D, et al: The PSMA-targeting half-life extended BiTE therapy AMG

160 has potent antitumor activity in preclinical models of

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res.

27:2928–2937. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Wei M, Zuo S, Chen Z, Qian P, Zhang Y,

Kong L, Gao H, Wei J and Dong J: Oncolytic vaccinia virus

expressing a bispecific T-cell engager enhances immune responses in

EpCAM positive solid tumors. Front Immunol.

13(1017574)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Ayzman A, Pachynski RK and Reimers MA:

PSMA-based therapies and novel therapies in advanced prostate

cancer: The now and the future. Curr Treat Options Oncol.

26:375–384. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Jin Y, Lorvik KB, Jin Y, Beck C, Sike A,

Persiconi I, Kvaløy E, Saatcioglu F, Dunn C and Kyte JA:

Development of STEAP1 targeting chimeric antigen receptor for

adoptive cell therapy against cancer. Mol Ther Oncolytics.

26:189–206. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Si M, Xia Y, Cong M, Wang D, Hou Y and Ma

H: In situ co-delivery of doxorubicin and cisplatin by Injectable

thermosensitive hydrogels for enhanced osteosarcoma treatment. Int

J Nanomedicine. 17:1309–1322. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Tu Z, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Meng W and Li L:

Barriers and solutions for CAR-T therapy in solid tumors. Cancer

Gene Ther. 32:923–934. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Kim YJ, Li W, Zhelev DV, Mellors JW,

Dimitrov DS and Baek DS: Chimeric antigen receptor-T cells are

effective against CEACAM5 expressing non-small cell lung cancer

cells resistant to antibody-drug conjugates. Front Oncol.

13(1124039)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Jiang Y, Wen W, Yang F, Han D, Zhang W and

Qin W: Prospect of prostate cancer treatment: Armed CAR-T or

combination therapy. Cancers (Basel). 14(967)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Wala JA and Hanna GJ: Chimeric antigen

receptor T-cell therapy for solid tumors. Hematol Oncol Clin North

Am. 37:1149–1168. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Bains RS, Raju TG, Semaan LC, Block A,

Yamaguchi Y, Priceman SJ, George SC and Shirure VS: Vascularized

tumor-on-a-chip to investigate immunosuppression of CAR-T cells.

Lab Chip. 25:2390–2400. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Norde WJ, Hobo W, van der Voort R and

Dolstra H: Coinhibitory molecules in hematologic malignancies:

Targets for therapeutic intervention. Blood. 120:728–736.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

68

|

Alavi SE, Ebrahimi Shahmabadi H, Sharma LA

and Sharma A: Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems for

non-surgical periodontal therapy: Innovations and clinical

applications. 3 Biotech. 15(269)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

69

|

Guo F, Luo S, Wang L, Wang M, Wu F, Wang

Y, Jiao Y, Du Y, Yang Q, Yang X and Yang G: Protein corona,

influence on drug delivery system and its improvement strategy: A

review. Int J Biol Macromol. 256 (Pt 2)(128513)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

70

|

Guo L, Shi D, Shang M, Sun X, Meng D, Liu

X, Zhou X and Li J: Utilizing RNA nanotechnology to construct

negatively charged and ultrasound-responsive nanodroplets for

targeted delivery of siRNA. Drug Deliv. 29:316–327. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

71

|

Seifert R, Kessel K, Schlack K, Weckesser

M, Kersting D, Seitzer KE, Weber M, Bögemann M and Rahbar K: Total

tumor volume reduction and low PSMA expression in patients

receiving Lu-PSMA therapy. Theranostics. 11:8143–8151.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

72

|

Shih CH, Hsieh TY and Sung WW:

Prostate-specific membrane antigen-targeted antibody-drug

conjugates: A promising approach for metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cells. 14(513)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

73

|

Liu D, Bao L, Zhu H, Yue Y, Tian J, Gao X

and Yin J: Microenvironment-responsive anti-PD-L1 x CD3 bispecific

T-cell engager for solid tumor immunotherapy. J Control Release.

354:606–614. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

74

|

Tan B, Tu C, Xiong H, Xu Y, Shi X, Zhang

X, Yang R, Zhang N, Lin B, Liu M, et al: GITRL enhances

cytotoxicity and persistence of CAR-T cells in cancer therapy. Mol

Ther. 33:2789–2800. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

75

|

Techaapornkun P, Rojpalakorn W, Mejun N,

Khaniya A, Thammahong A, Thu MS, Hirankarn N and Pitakkitnukun P:

Comparative efficacy and safety of BCMA-targeted CAR T cells and

BiTEs in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: A meta-analysis of

interventional and real-world studies. Ann Hematol. 104:4791–4809.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

76

|

Bolsée J, Violle B, Jacques-Hespel C,

Nguyen T, Lonez C and Breman E: Tandem CAR T-cells targeting CD19

and NKG2DL can overcome CD19 antigen escape in B-ALL. Front

Immunol. 16(1557405)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

77

|

Yamamichi G, Kato T, Watabe T, Hatano K,

Uemura M and Nonomura N: Current status of prostate-specific

membrane antigen-targeted alpha radioligand therapy in prostate

cancer. Anticancer Res. 44:879–888. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

78

|

Zhang Q, Helfand BT, Carneiro BA, Qin W,

Yang XJ, Lee C, Zhang W, Giles FJ, Cristofanilli M and Kuzel TM:

Efficacy against human prostate cancer by prostate-specific

membrane antigen-specific, transforming growth Factor-β insensitive

genetically targeted CD8+ T-cells derived from patients with

metastatic castrate-resistant disease. Eur Urol. 73:648–652.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

79

|

Guedan S and Delgado J: Immobilizing a

moving target: CAR T cells hit CD22. Clin Cancer Res. 25:5188–5190.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

80

|

Song EZ, Wang X, Philipson BI, Zhang Q,

Thokala R, Zhang L, Assenmacher CA, Binder ZA, Ming GL, O'Rourke

DM, et al: The IAP antagonist birinapant enhances chimeric antigen

receptor T cell therapy for glioblastoma by overcoming antigen

heterogeneity. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 27:288–304. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

81

|

Peter J, Toppeta F, Trubert A, Danhof S,

Hudecek M and Däullary T: Multi-Targeting CAR-T cell strategies to

overcome immune evasion in lymphoid and myeloid malignancies. Oncol

Res Treat. 48:265–279. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

82

|

Borcoman E, Kamal M, Marret G, Dupain C,

Castel-Ajgal Z and Le Tourneau C: HDAC inhibition to prime immune

checkpoint inhibitors. Cancers (Basel). 14(66)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

83

|

López-Collazo E and Hurtado-Navarro L:

Cell fusion as a driver of metastasis: Re-evaluating an old

hypothesis in the age of cancer heterogeneity. Front Immunol.

16(1524781)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

84

|

Derderian S, Vesval Q, Wissing MD, Hamel

L, Côté N, Vanhuyse M, Ferrario C, Bladou F, Aprikian A and

Chevalier S: Liquid biopsy-based targeted gene screening highlights

tumor cell subtypes in patients with advanced prostate cancer. Clin

Transl Sci. 15:2597–2612. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

85

|

Tserunyan V and Finley SD: Modelling

predicts differences in chimeric antigen receptor T-cell signalling

due to biological variability. R Soc Open Sci.

9(220137)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

86

|

Fan J, Zhu J, Zhu H and Xu H: Potential

therapeutic targets in myeloid cell therapy for overcoming

chemoresistance and immune suppression in gastrointestinal tumors.

Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 198(104362)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

87

|

Wang H, Liu S, Zhan J, Liang Y and Zeng X:

Shaping the immune-suppressive microenvironment on tumor-associated

myeloid cells through tumor-derived exosomes. Int J Cancer.

154:2031–2042. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

88

|

Kemp SB, Pasca di Magliano M and Crawford

HC: Myeloid cell mediated immune suppression in pancreatic cancer.

Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 12:1531–1542. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

89

|

Kerr MD, McBride DA, Chumber AK and Shah

NJ: Combining therapeutic vaccines with chemo- and immunotherapies

in the treatment of cancer. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 16:89–99.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

90

|

Ganaie AA, Mansini AP, Hussain T, Rao A,

Siddique HR, Shabaneh A, Ferrari MG, Murugan P, Klingelhöfer J,

Wang J, et al: Anti-S100A4 antibody therapy is efficient in

treating aggressive prostate cancer and reversing

immunosuppression: Serum and biopsy S100A4 as a clinical predictor.

Mol Cancer Ther. 19:2598–2611. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

91

|

Wang K, Hao Z, Fu X, Li W, Jiao A and Hua

X: Involvement of elevated ASF1B in the poor prognosis and

tumorigenesis in pancreatic cancer. Mol Cell Biochem.

477:1947–1957. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

92

|

Kim B, Jung S, Kim H, Kwon JO, Song MK,

Kim MK, Kim HJ and Kim HH: The role of S100A4 for bone metastasis

in prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 21(137)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

93

|

Peng S, Hu P, Xiao YT, Lu W, Guo D, Hu S,

Xie J, Wang M, Yu W, Yang J, et al: Single-cell analysis reveals

EP4 as a target for restoring T-cell infiltration and sensitizing

prostate cancer to immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 28:552–567.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

94

|

Yan J, Wang Y, Jia Y, Liu S, Tian C, Pan

W, Liu X and Wang H: Co-delivery of docetaxel and curcumin prodrug

via dual-targeted nanoparticles with synergistic antitumor activity

against prostate cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 88:374–383.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

95

|

Zhuang R, Xie R, Peng S, Zhou Q, Lin W, Ou

Y, Chen B, Su T, Li Z, Huang H, et al: An anti-androgen

resistance-related gene signature acts as a prognostic marker and

increases enzalutamide efficacy via PLK1 inhibition in prostate

cancer. J Transl Med. 23(480)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

96

|

Sartor O, de Bono J, Chi KN, Fizazi K,

Herrmann K, Rahbar K, Tagawa ST, Nordquist LT, Vaishampayan N,

El-Haddad G, et al: Lutetium-177-PSMA-617 for metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 385:1091–1103.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

97

|

Vakil V and Trappe W: Drug-resistant

cancer treatment strategies based on the dynamics of clonal

evolution and PKPD modeling of drug combinations. IEEE/ACM Trans

Comput Biol Bioinform. 19:1603–1614. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

98

|

Xu J, Yang X, Deshmukh D, Chen H, Fang S

and Qiu Y: The role of crosstalk between AR3 and E2F1 in drug

resistance in prostate cancer cells. Cells. 9(1094)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

99

|

Chatzilygeroudi T, Karantanos T and Pappa

V: Unraveling venetoclax resistance: Navigating the future of

HMA/Venetoclax-Refractory AML in the molecular era. Cancers

(Basel). 17(1586)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

100

|

Saad F: Should only patients with BRCA

mutation be treated with a combination of an androgen receptor

pathway inhibitor and a PARP inhibitor for metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer? The answer is no. Eur Urol

Focus. 10:506–508. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

101

|

Hachem S, Yehya A, El Masri J, Mavingire

N, Johnson JR, Dwead AM, Kattour N, Bouchi Y, Kobeissy F,

Rais-Bahrami S, et al: Contemporary update on clinical and

experimental prostate cancer biomarkers: A multi-omics-focused

approach to detection and risk stratification. Biology (Basel).

13(762)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

102

|

Chen Y, Fan X, Lu R, Zeng S and Gan P:

PARP inhibitor and immune checkpoint inhibitor have synergism

efficacy in gallbladder cancer. Genes Immun. 25:307–316.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

103

|

Kumar M, Nguyen TPN, Kaur J, Singh TG,

Soni D, Singh R and Kumar P: Opportunities and challenges in

application of artificial intelligence in pharmacology. Pharmacol

Rep. 75:3–18. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

104

|

Danila DC, Szmulewitz RZ, Vaishampayan U,

Higano CS, Baron AD, Gilbert HN, Brunstein F, Milojic-Blair M, Wang

B, Kabbarah O, et al: Phase I study of DSTP3086S, an antibody-drug

conjugate targeting six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of

prostate 1, in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. J

Clin Oncol. 37:3518–3527. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

105

|

Paoletti C and Hayes DF: Circulating tumor

cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 882:235–258. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

106

|

Vis DJ, Palit SAL, Corradi M, Cuppen E,

Mehra N, Lolkema MP, Wessels LFA, van der Heijden MS, Zwart W and

Bergman AM: Whole genome sequencing of 378 prostate cancer

metastases reveals tissue selectivity for mismatch deficiency with

potential therapeutic implications. Genome Med.

17(24)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

107

|

van der Sar ECA, Kühr AJS, Ebbers SC,

Henderson AM, de Keizer B, Lam MGEH and Braat AJAT: Baseline

imaging derived predictive factors of response following [177Lu]

Lu-PSMA-617 therapy in salvage metastatic castration-resistant

prostate cancer: A lesion- and patient-based analysis.

Biomedicines. 10(1575)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

108

|

Hwang C, Henderson NC, Chu SC, Holland B,

Cackowski FC, Pilling A, Jang A, Rothstein S, Labriola M, Park JJ,

et al: Biomarker-directed therapy in black and white men with

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. JAMA Netw Open.

6(e2334208)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

109

|

Parghane RV and Basu S: PSMA-targeted

radioligand therapy in prostate cancer: Current status and future

prospects. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 23:959–975. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

110

|

Petrylak DP, Vogelzang NJ, Chatta K,

Fleming MT, Smith DC, Appleman LJ, Hussain A, Modiano M, Singh P,

Tagawa ST, et al: PSMA ADC monotherapy in patients with progressive

metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer following

abiraterone and/or enzalutamide: Efficacy and safety in open-label

single-arm phase 2 study. Prostate. 80:99–108. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

111

|

Thang SP, Violet J, Sandhu S, Iravani A,

Akhurst T, Kong G, Ravi Kumar A, Murphy DG, Williams SG, Hicks RJ

and Hofman MS: Poor outcomes for patients with metastatic

castration-resistant prostate cancer with low prostate-specific

membrane antigen (PSMA) expression deemed ineligible for

177Lu-labelled PSMA radioligand therapy. Eur Urol Oncol. 2:670–676.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

112

|

Fu Y, Urban DJ, Nani RR, Zhang YF, Li N,

Fu H, Shah H, Gorka AP, Guha R, Chen L, et al: Glypican-3-specific

antibody drug conjugates targeting hepatocellular carcinoma.

Hepatology. 70:563–576. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

113

|

Xu J, Liu W, Fan F, Zhang B, Sun C and Hu

Y: Advances in nano-immunotherapy for hematological malignancies.

Exp Hematol Oncol. 13(57)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

114

|

Cao P and Bae Y: Polymer nanoparticulate

drug delivery and combination cancer therapy. Future Oncol.

8:1471–1480. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

115

|

Paschalis A, Sheehan B, Riisnaes R,

Rodrigues DN, Gurel B, Bertan C, Ferreira A, Lambros MBK, Seed G,

Yuan W, et al: Prostate-specific membrane antigen heterogeneity and

DNA repair defects in prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 76:469–478.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

116

|

Hong J, Bae S, Cavinato L, Seifert R,

Ryhiner M, Rominger A, Erlandsson K, Wilks M, Normandin M,

El-Fakhri G, et al: Deciphering the effects of radiopharmaceutical

therapy in the tumor microenvironment of prostate cancer: An

in-silico exploration with spatial transcriptomics. Theranostics.

14:7122–7139. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

117

|

Narayana RVL and Gupta R: Exploring the

therapeutic use and outcome of antibody-drug conjugates in ovarian

cancer treatment. Oncogene. 44:2343–2356. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

118

|

Grosso C, Silva A, Delerue-Matos C and

Barroso MF: Single and multitarget systems for drug delivery and

detection: Up-to-date strategies for brain disorders.

Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 16(1721)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

119

|

Yeh CY, Hsiao JK, Wang YP, Lan CH and Wu

HC: Peptide-conjugated nanoparticles for targeted imaging and

therapy of prostate cancer. Biomaterials. 99:1–15. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

120

|

Bimbatti D, Maruzzo M, Pierantoni F,

Diminutto A, Dionese M, Deppieri FM, Lai E, Zagonel V and Basso U:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors rechallenge in urological tumors: An

extensive review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol.

170(103579)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

121

|

McMullan C, Turner G, Retzer A, Belli A,

Davies EH, Nice L, Flavell L, Flavell J and Calvert M: Testing an

electronic patient-reported outcome platform in the context of

traumatic brain injury: PRiORiTy usability study. JMIR Form Res.

9(e58128)2025.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

122

|

Ramos-Casals M and Sisó-Almirall A:

Immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Ann

Intern Med. 177:ITC17–ITC32. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

123

|

Naing A, Hajjar J, Gulley JL, Atkins MB,

Ciliberto G, Meric-Bernstam F and Hwu P: Strategies for improving

the management of immune-related adverse events. J Immunother

Cancer. 8(e001754)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

124

|

Ong SY and Baird JH: A primer on chimeric

antigen receptor T-cell therapy-related toxicities for the

intensivist. J Intensive Care Med. 39:929–938. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

125

|

Ciano-Petersen NL, Muñiz-Castrillo S,

Vogrig A, Joubert B and Honnorat J: Immunomodulation in the acute

phase of autoimmune encephalitis. Rev Neurol (Paris). 178:34–47.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|