Introduction

Insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 plays a crucial

role in human growth and is related to the action of growth hormone

(GH). Moreover, IGF-1 regulates growth, glucose uptake and protein

metabolism (1). IGF-1 is released

by the liver by the action of GH (2). IGF-1 promotes cell proliferation by

mediating the effects of GH and, through a negative feedback

mechanism, inhibits GH release by suppressing GH-releasing hormone

(3). IGF-1 is particularly abundant

during adolescence. The growth-promoting effects of GH are mediated

by IGF-1 through activation of downstream signaling pathways via

the IGF-1 receptor (IGF-1R) (4).

Although rare, a lack of the IGF-1 gene or GH results in muscle

development disorder and impaired growth (5). Thus, IGF-1 and GH have important

functions as growth factors.

STAT proteins function as upstream transcriptional

regulators of IGF-1 in-response to GH stimulation, while also

serving as downstream effectors in IGF-1R-mediated signaling, and

STAT is activated via phosphorylation by various factors and

cytokines (6). This protein

translocates to the nucleus and binds to its promoter site

(7). Phosphorylated (p)STAT

proteins bind in a dimeric form to the IGF-1 promoter, thereby

regulating the expression of IGF-1 mRNA (8). In addition to STAT1, STAT2 and STAT5B

bind and influence GH (9). STAT5B

serves a pivotal role in the growth-promoting effects of GH,

particularly in GH signaling, osteoblast differentiation and the

maintenance of bone homeostasis (10,11).

Hemp seed (HS) was first cultivated in China and are

nutritious, containing ~25% protein and 35% oil-based antioxidants

(12,13). Previously, HS was crushed or

consumed whole, as well as being used as an important grain in

traditional food and medicines (12). In addition, the nutritional benefits

of HS have long been recognized in Asia and Eastern Europe, where

they have been used as food for both humans and livestock (12). Hemp is more commonly consumed as

marijuana rather than as HS, and this has an association with

addiction, which leads to negative perceptions (14,15).

However, HS is increasingly recognized for benefits (16-18).

HS is rich in fatty acids, minerals, vitamins and essential amino

acids (12). Several studies have

reported their positive effects on cardiovascular disease, cancer,

inflammatory conditions, atopic dermatitis and antimicrobial

activity (19-22).

To the best of our knowledge, however, there are no studies on the

effects of HS on GH or growth outcomes.

C2C12 cells were selected as they are a

well-established in vitro model for skeletal muscle biology,

capable of differentiating into myotubes and widely used for

investigating the GH-IGF-1 axis, muscle hypertrophy and

regeneration (23,24). C3H10T1/2 cells were selected for

their multipotent differentiation potential into myogenic,

osteogenic and chondrogenic lineages (25). These cells are used to assess

early-stage proliferation and growth factor responsiveness prior to

lineage commitment (26). HS

extracts and their bioactive compounds promote myoblast

differentiation (27). Recent

studies have demonstrated that hemp extracts improve muscle health

by regulating muscle protein degradation pathways (27,28).

Hemp-derived compounds have been shown to promote the proliferation

of hair follicle dermal papilla stem cells through genetic

regulation, cell differentiation and modulation of the immune

system (29). Based on this, it was

hypothesized the active components in HS extract promote cell

proliferation via cellular signaling pathways.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and reagents

Edible HS (origin: Canada) were purchased from a

NongHyup market in the Republic of Korea and extracted with 50%

ethanol for 48 h at room temperature to obtain the HS extract.

DMEM, penicillin-streptomycin, trypsin-EDTA (0.05%) and fetal

bovine serum (FBS; cat. no. A5670801) were purchased from Gibco

(Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Primary antibodies against pSTAT5

(cat. no. #9351), JAK2 (cat. no. #3230), pJAK2 (cat. no. #3776),

pIGF-1Rβ (cat. no. #3012s) and cleaved caspase3 (cat. no. #9661s)

were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. IGF-1 antibody

(cat. no. ab9572) was purchased from Abcam. Antibodies against

β-actin (cat. no. sc-47778), GHR (cat. no. sc-137185), IGF-1Rβ

(cat. no. sc-713) and STAT5b (cat. no. sc-1656), as well as

HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (goat anti-mouse and rabbit

IgG; cat. nos. sc-516102, sc-2357), were obtained from Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc. JAK2 inhibitor AG490 (cat. no. 658411;

Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA) was used at 25 µM for 24 h at 37˚C in a

humidified 5% CO2 incubator during the western blot

analysis to confirm the involvement of the JAK2/STAT5b pathway.

Cell viability assay

The mouse muscle and embryo cell lines C2C12 and

C3H10T1/2 (cat. nos. CRL-1772 and KCLB 10226, respectively; both

American Type Culture Collection) were seeded in 96-well plates

(5x10³ cells/well) and incubated for 24 h at 37˚C. HS extract

(10-600 µg/ml) was added for another 24, 48 and 72 h at 37˚C in 5%

CO2. MTT reagent was applied and incubated for 4 h. The

purple formazan was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide. Absorbance at

560 nm was measured to assess cell viability. All experiments were

performed in triplicate.

Cell culture

The cells were cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1%

penicillin at 37˚C in 5% CO2.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

assay

ChIP assay was conducted using the

Imprint® ChIP kit (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA cat. no.

CHP1) following the manufacturer's protocol at 4˚C. C2C12 and

C3H10T1/2 cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and quenched

with 1.25 M glycine for 5 min. Following lysis, chromatin was

sonicated (25% amplitude, 30 sec on/off for 20 min on ice) and

centrifuged at 21,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C. The supernatant was

diluted with the dilution buffer (1:1) and 5 µl aliquots diluted

samples were used as internal controls. The supernatant was

immunoprecipitated with 5 µl anti-STAT5b antibody (cat. no.

sc-1656, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), while controls used 1 µl

normal goat IgG and 1 µl anti-RNA polymerase II. The amount of

lysate used per immunoprecipitation reaction was ~100 µl, Bound

DNA–protein complexes were treated with 1 µl Proteinase K for

cross-link reversal and DNA release. Washing was performed with the

wash buffers provided in the kit. Bound DNA was purified and

analyzed by quantitative PCR using 10 µl TB Green Advantage Premix

(Takara Bio, cat. no. 639676) using IGF-1 primers (forward:

5'-TGCTCACAAACCCACATCAA-3' and reverse:

3'-GCTAGGTTCTTCACAGCTCC-5'). Thermocycling was performed with 40

cycles at 95˚C (30 sec), 60˚C (30 sec) and 72˚C (40 sec), followed

by final extension at 72˚C for 5 min. The calculations were

performed using the 2-ΔΔCq values obtained (30).

Comet assay

C2C12 and C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded in 6-well

plates at a density of 1x105 cells/well and cultured for

24 h at 37˚C in 5% CO2. Control cells were cultured

under the same conditions without HS treatment. DNA damage was

assessed using the Comet Assay kit (Abcam; cat. no. ab238544)

according to the manufacturer's protocol. Cell morphology was

analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation

IX71/DP72).

DAPI staining

C2C12 and C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded in 6-well

plates (1x105 cells/well) and cultured for 24 h at 37˚C.

The cells were then washed with PBS and fixed with 100% methanol

for 10 min at room temperature. After fixation, the cells were

washed twice with PBS and incubated with 1 ml of 5 µM DAPI staining

solution for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were then washed

twice with PBS and images were captured using a fluorescence

microscope (Olympus Corporation IX71/DP72)

ELISA

C3H10T1/2 cells were cultured (1x106

cells/ml) for 24 h at 37˚C in DMEM containing 100 or 200 µg/ml HS

extract. IGF-1 levels in the culture supernatant were measured

using a mouse IGF-1 ELISA kit (Abcam, cat. no. ab100695) according

to the manufacturer's instructions.

Total cell lysis and western

blotting

Whole cell lysates were prepared from untreated

cells or cells treated for 24 h at 37˚C with 100 or 200 µg/ml HS

using RIPA buffer (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.)

supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Cell lysates

were incubated for 30 min on ice and total protein concentration

was measured using the Bradford assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.). Equal amounts of protein (30 µg/lane) were separated by

6-15% SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The

membranes were blocked with TBS-T buffer (0.1% Tween-20) and

blocked with 5% skimmed milk (BD Biosciences; cat. no. 90002-594)

prepared in TBS-T buffer for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane

was incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary antibody diluted in 5%

skimmed milk, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary

antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Immunoreactive bands were

visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Femto

Clean ECL, GenDEPOT, LLC; cat. no. 77449) and captured with a

LAS-4000 imaging system (FUJIFILM Corporation). Densitometric

analysis was performed using ImageJ software (version 1.53;

National Institutes of Health).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as the mean ± SEM. All

experiments were performed in triplicate and analyzed using one-way

ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey's test was used to evaluate

differences among groups. Prior to analysis, data were tested for

normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and for homogeneity of

variances using Levene's test. All statistical analyses were

performed using SAS software (version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc.).

P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

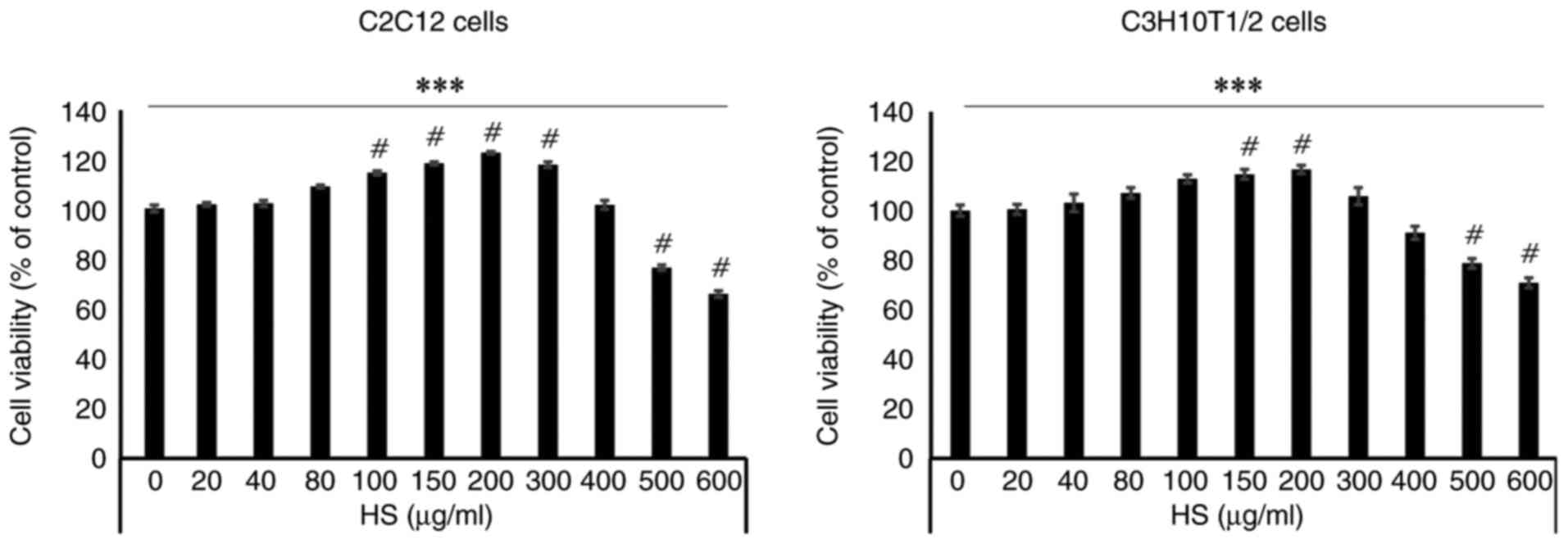

HS enhances C2C12 and C3H10T1/2 cell

viability in a concentration-dependent manner

HS was extracted in 50% ethanol and allowed to react

for 48 h. Following filtration, only the pure liquid was used. To

evaluate the effect of HS on cells, MTT assay was performed using

C2C12 cells. There were significant differences between cells

treated with HS concentrations ranging from 100 to 600 µg/ml. HS

exhibited no cytotoxicity up to a concentration of 500 µg/ml.

However, at concentrations >500 µg/ml, cell viability decreased,

indicating cytotoxicity. Therefore, the optimal concentration for

subsequent cell experiments was set at 200 µg/ml (Figs. 1 and S1).

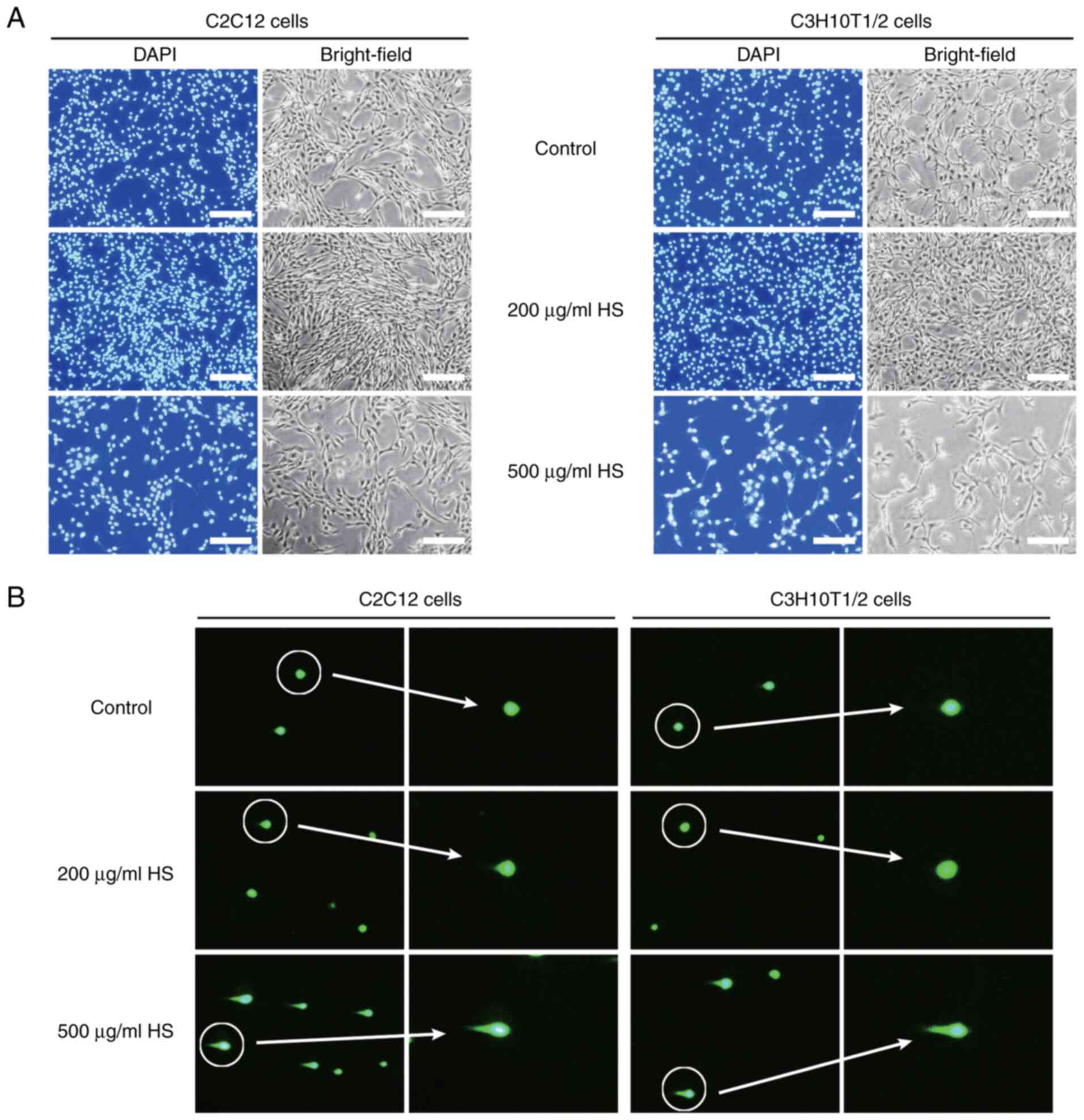

HS (200 µg/ml) exhibits no

cytotoxicity

When cells were treated with HS at a concentration

of 200 µg/ml, there was a marked increase in the number of stained

nuclei, indicating enhanced cell proliferation. By contrast, when

cells were treated with HS at 500 µg/ml, the number of nuclei

notably decreased, confirming cytotoxicity (Fig. 2A). Treatment with high

concentrations of HS may lead to DNA damage (DNA unwinding)

(31); therefore, comet assay was

performed to determine whether HS induces DNA damage. Fluorescence

microscopy revealed that treatment with 500 µg/ml HS increased the

length of comet tails and the number of comet-positive cells,

whereas no comet tails were formed in the untreated control and 200

µg/ml HS groups (Fig. 2B),

consistent with the absence of detectable DNA damage at the optimal

concentration. High concentrations of HS extract (500 µg/ml)

increased cleaved caspase-3 levels, indicative of apoptosis

induction (Fig. S2). These results

indicated that HS at 100-300 µg/ml was not cytotoxic and promoted

cell viability.

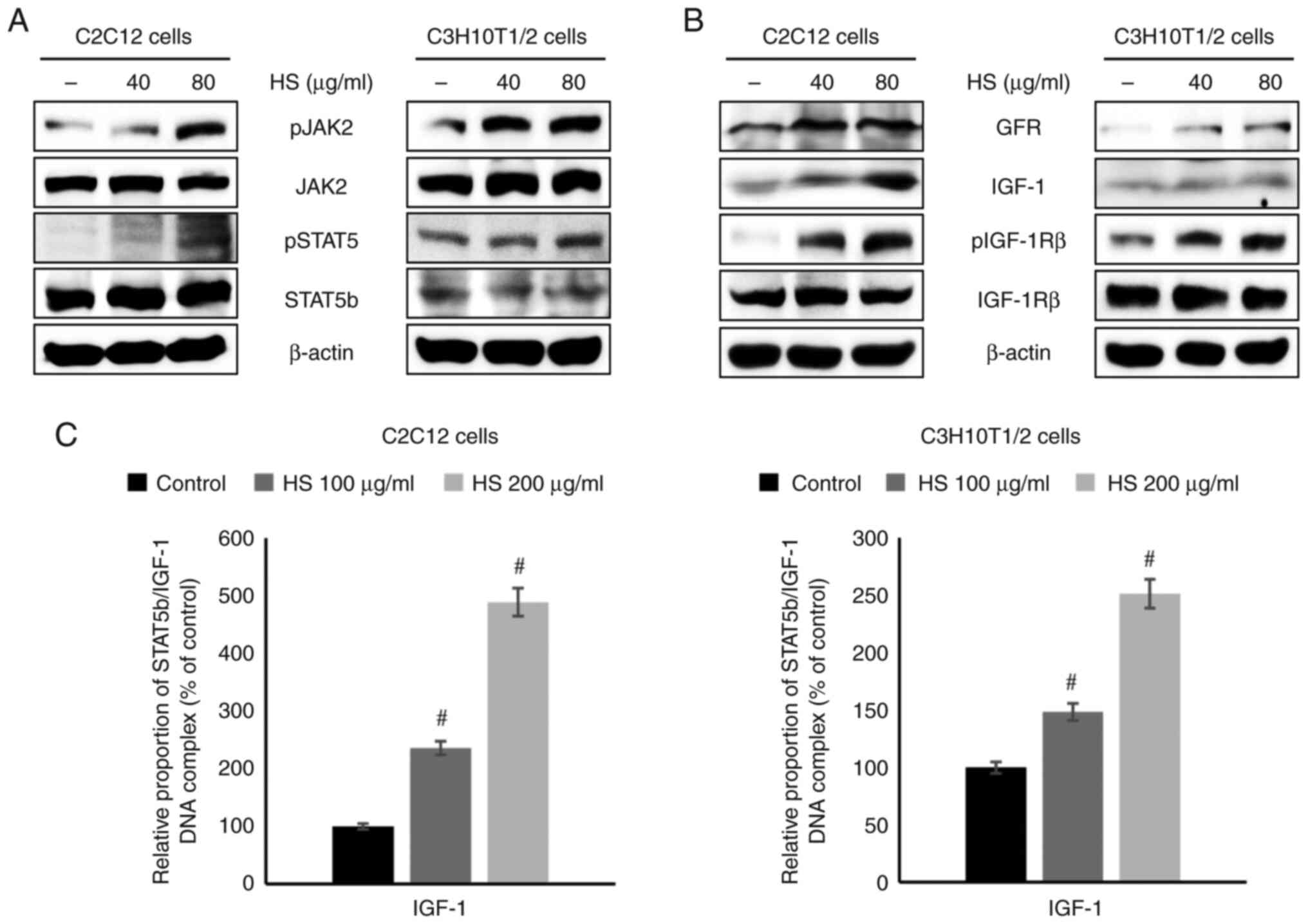

HS increases the expression of GHR and

IGF-1 via the JAK2/STAT5b pathway

Western blotting was performed to investigate the

cell signaling mechanisms. The protein levels of pJAK2 and pSTAT5

in C2C12 and C3H10T1/2 cells were upregulated by HS treatment in a

concentration-dependent manner. Furthermore, the phosphorylation of

JAK2 and STAT5b was induced, thereby activating the cellular

proliferation signaling pathway (Figs.

3A and S3A and B). Furthermore, the protein levels of

GHR, IGF-1, and pIGF-1Rβ were also increased by HS treatment in a

concentration-dependent manner (Fig.

3B). The present study investigated the effect of HS on the

binding of STAT5b to the IGF-1 promoter region. ChIP analysis using

a STAT5b antibody revealed that HS at 100-200 µg/ml increased the

binding of STAT5b to the IGF-1 promoter. STAT5b/IGF-1 complex

formation was induced, resulting in the activation of downstream

transcription (Fig. 3C). These

findings suggest that pSTAT5 and IGF-1 are key targets of HS, with

their expression enhanced to upregulate IGF-1 transcription. To

validate that STAT5b activation is mediated via JAK2, cells were

treated with JAK2 inhibitor. The inhibition of JAK2 markedly

reduced STAT5 phosphorylation and downstream IGF-1 expression in

C3H10T1/2 cells (Fig. S4),

confirming that HS-induced STAT5b activation was dependent on JAK2

signaling. Overall, the results indicated that HS may function as a

stimulator of key GH-associated cell signaling. ELISA further

confirmed that HS treatment at 200 µg/ml significantly increased

IGF-1 secretion in C3H10T1/2 cells (Fig. S5), supporting the upregulation of

IGF-1 expression observed in the western blot analysis.

Discussion

Cell proliferation studies have primarily focused on

GH (32,33). One of the key upstream regulators of

GH is IGF-1, which binds IGF-1R to enhance GH activity, thereby

influencing growth and development (34). This phenomenon occurs in numerous

types of tissue and involves the continuous secretion of these

factors to maintain homeostasis, although differences arise

depending on the specific receptors involved (35,36).

The benefits of IGF-1 include building muscle and bone mass,

preventing muscle wasting, helping with growth, regulating blood

sugar levels and protecting against neurological disorders. IGF-1

increases skeletal muscle protein synthesis via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR

and PI3K/Akt/glycogen synthase kinase 3 β pathways (37). The dangers of IGF-1 include

potentially increasing the risk of developing certain types of

cancer (including breast, prostate, colorectal and thyroid cancer)

and reducing life span (38).

The present study used C2C12 cells as a committed

myogenic model responsive to GH/IGF-1 via the JAK2/STAT5b/IGF-1

pathway (35). C3H10T1/2 cells, as

multipotent mesenchymal progenitors capable of differentiating into

osteogenic, chondrogenic or, under certain conditions, myogenic

lineages, were used to examine early proliferative and signaling

effects prior to full myogenic differentiation. This dual-cell line

approach enabled investigation of distinct stages of

muscle-associated cellular responses and provided a robust platform

for evaluating the effects of HS extract.

GH levels peak during the pubertal growth period,

serving a crucial role in adolescent growth spurts, and decline

progressively with aging. Because GH serves a crucial role in

muscle and bone metabolism, maintaining its secretion is important

in old age (39). In older adults

aged ≥70 years, muscle loss, or sarcopenia, occurs because of

decreased levels of GH and IGF-1, which notably affects muscle mass

and strength (40). Increasing and

activating GH and IGF-1 levels, as well as muscle-strengthening

exercises, are key to mitigate the development of sarcopenia. In

addition, as digestive efficiency declines with age, nutrient-dense

foods such as HS may help support muscle health by enhancing the

action of IGF-1 or mimicking its effects (41,42).

HS shows promise as a potential dietary strategy to delay the onset

and progression of sarcopenia.

Recent studies have demonstrated that plant-derived

compounds regulate the GH-IGF-1 signaling axis and modulate

downstream STAT pathways (43,44).

Clinical investigations have identified GH and IGF-1 as key

regulators of metabolic activity, immune response and hepatic

stellate cell function in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

(45,46). In pediatric populations, researchers

have described the key role of GH and its hepatic effector IGF-1 in

normal growth processes and have emphasized the regulatory

involvement of SIRT1 in GH secretion and IGF-1 expression (47). Daucosterol, a phytosteroid derived

from walnut meat, is a plant-based compound that promotes IGF-1

protein expression and enhances cell proliferation (48). Similarly, researchers have evaluated

the effects of Epimedium extract, particularly icariin, and

have shown that it increases IGF-1 expression in skeletal muscle

cells (23). In C2C12 myotubes,

icariin has been reported to activate the IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway,

induce muscle hypertrophy and suppress catabolic atrophy markers

(49). Furthermore, studies have

demonstrated that the targeted deletion of STAT5a/b in skeletal

muscle decreases local IGF-1 expression by ~60%, thereby impairing

muscle growth and function (50,51).

Consistent with previous studies (45-47,49,50),

the present results demonstrated that STAT5b served as a key

transcriptional mediator of IGF-1 in peripheral and muscle-related

cells. Previous studies have examined the effects of individual

plant-derived compounds (daucosterol, icariin) or employed genetic

knockout models to demonstrate the role of STAT5a/b in muscle

growth (45-47,49).

The aforementioned studies established that STAT5 activation is key

for transcriptional regulation of IGF-1 target genes. The present

study demonstrated that HS extract, a commonly consumed nutritional

source, pharmacologically enhances IGF-1/STAT5b signaling in

muscle-associated cells, demonstrating a dietary approach to

modulate this pathway. Targeted deletion of STAT5a/b decreases

IGF-1 expression and impairs muscle growth (50). In agreement, the present data showed

that increased STAT5b activation was associated with upregulated

IGF-1 signaling, supporting the functional relevance of STAT5b in

muscle regeneration. Thus, the present findings not only

corroborate the established role of STAT5b in muscle biology but

also demonstrated that a nutritional extract can modulate this

pathway pharmacologically.

HS is a highly nutritious food source rich in

protein, essential amino acids, polyunsaturated fatty acids

(including linoleic acid and α- and γ-linolenic acid), tocopherols

such as vitamin E and essential minerals (phosphorus, potassium,

magnesium, iron and zinc), which collectively contribute to

cardiovascular health, blood pressure regulation, antioxidant

defense and immune function (12).

However, despite these benefits, little is known about their

effects on cell proliferation, and the underlying mechanisms remain

unclear.

The present study evaluated the cytotoxicity of HS

extract on mouse muscle (C2C12) and embryonic (C3H10T1/2) cells and

determined the optimal treatment concentration (200 µg/ml). The

primary objective was to assess whether HS extract exerts any

biological effects before conducting detailed phytochemical

analyses. At 200 µg/ml, the protein levels of growth factors were

elevated, and there was increased phosphorylation of the downstream

Jak2/STAT5b signaling pathway members. Furthermore, HS extract did

not notably affect the levels of damaged DNA, and enhanced the

binding of the transcription factor pSTAT5b protein, which acts on

IGF-1 DNA. Therefore, HS may support cell proliferation and aid in

muscle recovery by stimulating IGF-1 and GH via the JAK2/STAT5b

signaling pathway.

Effective muscle regeneration requires not only

activation of signaling pathways but also viability and

proliferative capacity of muscle cells. The present data

demonstrated that HS promoted viability of C2C12 and C3H10T1/2

cells, providing a cellular basis for regenerative effects. While

PI3K/AKT and MAPK/ERK pathways are recognized regulators of

IGF-1-mediated muscle hypertrophy, their primary roles are

typically associated with downstream events such as protein

synthesis and cell proliferation. By contrast, STAT5b serves as a

direct transcriptional mediator of IGF-1 target genes (51). In the present study, HS extract

consistently activated the JAK2/STAT5b pathway, providing a

mechanistic link to IGF-1 transcriptional regulation. However, the

present study did not exclude the possibility of crosstalk with

PI3K/AKT or MAPK/ERK.

In addition to STAT5b, the IGF-1 signaling axis also

engages the PI3K/Akt and MAPK pathways, which are major downstream

effectors regulating muscle cell function. The PI3K/Akt pathway is

key for normal muscle growth, survival and hypertrophy (35,52).

Following IGF-1 stimulation, PI3K activation leads to Akt

phosphorylation, which promotes muscle hypertrophy, supports cell

proliferation and differentiation and conveys anti-apoptotic

signals that preserve muscle integrity (53,54).

The MAPK pathway is critical, particularly in controlling myoblast

proliferation and differentiation. Activation through Ras triggers

the ERK cascade, which drives myoblast proliferation but can

transiently suppress differentiation by inhibiting key regulators

such as MyoD. Conversely, other MAPK branches, including p38 MAPK

and myocyte enhancer factor 2C, are key for initiating and

maintaining myogenic differentiation (55,56).

Together, these pathways complement STAT5b by regulating the

balance between proliferation and differentiation.

Beyond the GH/JAK2/STAT5b/IGF-1 signaling pathway,

HS contains bioactive compounds that may influence muscle cells

more generally. The ω-3 fatty acid α-linolenic acid and the ω-6

fatty acid γ-linolenic acid decrease muscle inflammation and

protect against cell injury, while L-arginine contributes to

anti-inflammatory effects and supports cell repair processes

(57-59).

Together, these components maintain muscle cell membrane integrity,

attenuate inflammatory responses and provide essential substrates

for recovery. These actions suggest that HS extract supports

overall muscle function through diverse mechanisms, rather than

acting solely on a single growth-associated pathway.

Future work should identify and characterize the

active components responsible for these effects. Based on previous

reports, essential amino acids such as arginine and lysine,

together with storage proteins such as edestin, may contribute to

the increased cell proliferation (60-62).

In addition, polyunsaturated fatty acids (γ- and α-linolenic acid

and linoleic acid) and minerals such as methylsulfonylmethane

modulate GH signaling and underlie the enhanced JAK2/STAT5b

activation and IGF-1 production (16,63-65).

Although further experimental validation is needed, these bioactive

components provide a mechanistic basis for the present findings.

Due to potential cytotoxic effects at lower concentrations, the

clinical application of HS extract may be limited, underscoring the

need for further research to evaluate tissue-specific safety in

vivo.

In summary, HS induces expression of IGF-1 via the

Jak2/STAT5b signaling pathway to promote proliferation in C2C12 and

C3H/10T1/2 mouse cells. Moreover, pSTAT5b bound to IGF-1 DNA as a

direct transcription factor, serving a key role in enhancing cell

signaling. Therefore, HS may deliver specific growth signals for

cell proliferation and muscle recovery.

Supplementary Material

Effect of HS extract on the viability

of C3H10T1/2 cells at 24, 48, and 72 h. viability was determined

using the MTT assay. ***P<0.001;

#P<0.001 vs. Con. HS, hemp seed; con, control.

Western blotting of the protein

expression of c-caspase3 and caspase3 following treatment of

C3H10T1/2 cells with 100, 200 and 500 μg/ml HS extracts for

24 h. c, cleaved; HS, hemp seed; con, control.

Quantitative analysis of protein

expression levels in C2C12 and C3H10T1/2 cells treated with hemp

seed extract. (A) GHR, IGF-1, pIGF-1Rβ, and IGF-1Rβ protein levels

in cells treated with varying concentrations of HS extract. (B)

pJAK2, JAK2, pSTAT5, and STAT5b protein levels in cells treated

with varying concentrations of HS extract. Protein expression

levels were normalized to β-actin. ***P<0.001;

#P<0.001 vs. Control; GHR, growth hormone receptor;

IGF-1R, insulin-like growth factor-1receptor; p, phospho; NS,

non-significant; HS, hemp seed.

Western blot analysis of pJAK2, total

JAK2, pSTAT5, total STAT5b and IGF-1 protein expression in

C3H10T1/2 cells treated with HS extract. Cells were incubated with

200 μg/ml HS extract and 25 μM AG490 (JAK2 inhibitor)

for 24 h, followed by protein extraction and immunoblotting. p,

phosphorylated; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; HS, hemp

seed.

ELISA showing increased IGF-1

production in C3H10T1/2 cells treated with hemp seed extract.

#P<0.001 vs. control. IGF, insulin-like growth

factor.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the National

Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korea government

(Ministry of Science and ICT grant no. RS-2024-00450676) and Korea

Basic Science Institute (National Research Facilities and Equipment

Center) grant funded by the Ministry of Education (grant no.

2023R1A6C101A045) and The Technology development Program (grant no.

S3452042) funded by the Ministry of Small and Medium-sized

Enterprises and Startups.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

JC and KJJ designed the experiments. DYK, HTK and YK

performed experiments. DYK and KJJ analyzed the data. DYK wrote the

manuscript. JC and KJJ edited and reviewed the manuscript. DYK and

KJJ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Brownlee M: The pathobiology of diabetic

complications: A unifying mechanism. Diabetes. 54:1615–1625.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Cheung LYM, George AS, McGee SR, Daly AZ,

Brinkmeier ML, Ellsworth BS and Camper SA: Single-cell RNA

sequencing reveals novel markers of male pituitary stem cells and

hormone-producing cell types. Endocrinology. 159:3910–3924.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Ashpole NM, Sanders JE, Hodges EL, Yan H

and Sonntag WE: Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 and

the aging brain. Exp Gerontol. 68:76–81. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Darvin P, Joung YH and Yang YM:

JAK2-STAT5B pathway and osteoblast differentiation. JAK-STAT.

2(e24931)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Laron Z: Insulin-like growth factor 1

(IGF-1): A growth hormone. Mol Pathol. 54:311–316. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Uematsu S and Akira S: The role of

Toll-like receptors in immune disorders. Expert Opin Biol Th.

6:203–214. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Kumar H, Kawai T and Akira S: Toll-like

receptors and innate immunity. Biochem Bioph Res Co. 388:621–625.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Oberbauer A: The Regulation of IGF-1 gene

transcription and splicing during development and aging. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 4(39)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Varco-Merth B and Rotwein P: Differential

effects of STAT proteins on growth hormone-mediated IGF-I gene

expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 307:E847–E855.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hu X, Li J, Fu M, Zhao X and Wang W: The

JAK/STAT signaling pathway: From bench to clinic. Sig Transduct

Target Ther. 6(402)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhu T, Goh ELK, Graichen R, Ling L and

Lobie PE: Signal transduction via the growth hormone receptor. Cell

Signal. 13:599–616. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Callaway JC: Hempseed as a nutritional

resource: An overview. Euphytica. 140:65–72. 2004.

|

|

13

|

Barbara F, Romina M, Nicolò LC and

Merendino N: The seed of industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa

L.): Nutritional Quality and Potential Functionality for Human

Health and Nutrition. Nutrients. 12(1935)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Salehi A, Puchalski K, Shokoohinia Y,

Zolfaghari B and Asgary S: Differentiating Cannabis products:

Drugs, food, and supplements. Front Pharmacol.

13(906038)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Pellegrino C, CB 00A0 and Jacopo GC: A

review of hemp as food and nutritional supplement. Cannabis

Cannabinoid Res. 6:19–27. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sirangelo TM, Diretto G, Fiore A, Felletti

S, Chenet T, Catani M and Spadafora ND: Nutrients and bioactive

compounds from cannabis sativa seeds: A review focused on

Omics-based investigations. Int J Mol Sci. 26(5219)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Tănase Apetroaei V, Pricop EM, Istrati DI

and Vizireanu C: Hemp seeds (Cannabis sativa L.) as a

valuable source of natural ingredients for functional foods.

Molecules. 29(2097)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hossain L, Whitney K and Simsek S: Hemp

seed as an emerging source of nutritious functional ingredients.

Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr: 1-17, 2025 doi:

10.1080/10408398.2025.2534839 (Epub ahead of print).

|

|

19

|

Chen T, He J, Zhang J, Zhang H, Qian P,

Hao J and Li L: Analytical characterization of Hempseed (seed of

Cannabis sativa L.) oil from eight regions in China. J Diet

Suppl. 7:117–129. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Roche HM: Unsaturated fatty acids. Proc

Nutr Soc. 58:397–401. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Saini RK and Keum YS: Omega-3 and omega-6

polyunsaturated fatty acids: Dietary sources, metabolism, and

significance-A review. Life Sci. 203:255–267. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Jin S and Lee MY: The ameliorative effect

of hemp seed hexane extracts on the Propionibacterium acnes-induced

inflammation and lipogenesis in sebocytes. PLoS One.

13(202933)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Lin YA, Li YR, Chang YC, Hsu MC and Chen

ST: Activation of IGF-1 pathway and suppression of atrophy related

genes are involved in Epimedium extract (icariin) promoted C2C12

myotube hypertrophy. Sci Rep. 11(10790)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Sadowski CL, Wheeler TT, Wang LH and

Sadowski HB: GH Regulation of IGF-I and suppressor of cytokine

signaling gene expression in C2C12 skeletal muscle cells.

Endocrinology. 142:3890–3900. 2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ker DF, Sharma R, Wang ET and Yang YP:

Development of mRuby2-transfected C3H10T1/2 fibroblasts for

musculoskeletal tissue engineering. PLoS One.

10(e0139054)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Milasincic DJ, Calera MR, Farmer SR and

Pilch PF: Stimulation of C2C12 myoblast growth by basic fibroblast

growth factor and insulin-like growth factor 1 can occur via

mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent and -independent

pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 16:5964–5973. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Hwangbo Y and Kim JH, Kim T and Kim JH:

Effects of hemp seed protein hydrolysates on the differentiation of

C2C12 cells and muscle atrophy. J Korean Soc Food Sci Nutr.

52:1225–1232. 2023.

|

|

28

|

Hwangbo Y, Pan JH, Lee JJ, Kim T and Kim

JH: Production of protein hydrolysates from hemp (Cannabis

sativa L.) seed and its protective effects against

dexamethasone-induced muscle atrophy. Food Biosci.

59(104046)2024.

|

|

29

|

Kim D, Kim NP and Kim B: Effects of

biomaterials derived from germinated hemp seeds on stressed hair

stem cells and immune cells. Int J Mol Sci. 25(7823)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Azqueta A, Stopper H, Zegura B, Dusinska M

and Møller P: Do cytotoxicity and cell death cause false positive

results in the in vitro comet assay? Mutat Res Genet Toxicol

Environ Mutagen. 881(503520)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Kassem M, Blum W, Ristelli J, Mosekilde L

and Eriksen EF: Growth hormone stimulates proliferation and

differentiation of normal human Osteoblast-like cells in vitro.

Calcif Tissue Int. 52:222–226. 1993.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Waters MJ and Brooks AJ: Growth hormone

and cell growth. Endocr Dev. 23:86–95. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Caron JM, Bannon M, Rosshirt L, Luis J,

Monteagudo L, Caron JM and Sternstein GM: Methyl sulfone induces

loss of metastatic properties and reemergence of normal phenotypes

in a metastatic cloudman S-91 (M3) murine melanoma cell line. PLoS

One. 5(e11788)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Kang DY, Sp N, Jo ES, Kim HD, Kim IH, Bae

SW, Jang KJ and Yang YM: Non-toxic sulfur enhances growth hormone

signaling through the JAK2/STAT5b/IGF-1 pathway in C2C12 cells. Int

J Mol Med. 45:931–938. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

van den Beld AW, Kaufman JM, Zillikens MC,

Lamberts SWJ, Egan JM and van der Lely AJ: The physiology of

endocrine systems with ageing. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol.

6:647–658. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Tadashi Y and Delafontaine P: Mechanisms

of IGF-1-Mediated regulation of skeletal muscle hypertrophy and

atrophy. Cells. 9(1970)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Mukama T, Srour B, Johnson T, Katzke V and

Kaaks R: IGF-1 and risk of morbidity and mortality from cancer,

cardiovascular diseases, and all causes in EPIC-Heidelberg. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 108:e1092–e1105. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ricci Bitti S, Franco M, Albertelli M,

Gatto F, Vera L, Ferone D and Boschetti M: GH Replacement in the

elderly: Is it worth it? Front Endocrinol (Lausanne).

12(680579)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Silvia G, Emanuele M, Stephen E and

Christiaan L: Modulation of GH/IGF-1 axis: Potential strategies to

counteract sarcopenia in older adults. Mech Ageing Dev.

129:593–601. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Maggio M, De Vita F, Lauretani F, Buttò V,

Bondi G, Cattabiani C, Nouvenne A, Meschi T, Dall'Aglio E and Ceda

GP: IGF-1, the crossroad of the nutritional, inflammatory and

hormonal pathways to frailty. Nutrients. 5:4184–4205.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Barclay RD, Burd NA, Tyler C, Tillin NA

and Mackenzie RW: The role of the IGF-1 signaling cascade in muscle

protein synthesis and anabolic resistance in aging skeletal muscle.

Front Nutr. 6(146)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Yue X, Hao W, Wang M and Fu Y: Astragalus

polysaccharide ameliorates insulin resistance in HepG2 cells

through activating the STAT5/IGF-1 pathway. Immun Inflamm Dis.

11(e1071)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Li Z, Dai X, Yang F, Zhao W, Xiong Z, Wan

W, Wu G, Xu T and Cao H: Compound probiotics promote the growth of

piglets through activating the JAK2/STAT5 signaling pathway. Front

Microbiol. 16(1480077)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Ma IL and Stanley TL: Growth hormone and

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Immunometabolism.

5(e00030)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Dichtel LE, Cordoba-Chacon J and Kineman

RD: Growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 regulation of

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab.

107:1812–1824. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Fedorczak A, Lewiński A and Stawerska R:

Involvement of sirtuin 1 in the growth hormone/insulin-like growth

factor 1 signal transduction and its impact on growth processes in

children. Int J Mol Sci. 24(15406)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Jiang LH, Yang NY, Yuan XL, Zou YJ, Zhao

FM, Chen JP, Wang MY and Lu DX: Daucosterol promotes the

proliferation of neural stem cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol.

140:90–99. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Kim HK, Kim MG and Leem KH: Icariin

stimulates myogenic differentiation and enhances muscle

regeneration in injured skeletal muscle. Biol Pharm Bull.

39:455–462. 2016.

|

|

50

|

Klover P and Hennighausen L: Postnatal

body growth is dependent on the transcription factors signal

transducers and activators of transcription 5a/b in muscle: a role

for autocrine/paracrine insulin-like growth factor I.

Endocrinology. 148:1489–1497. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Klover P, Chen W, Zhu BM and Hennighausen

L: Skeletal muscle growth and fiber composition in mice are

regulated through the transcription factors STAT5a/b: Linking

growth hormone to the androgen receptor. FASEB J. 23:3140–3148.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Joshi AS, da Silva MT, Kumar S and Kumar

A: Signaling networks governing skeletal muscle growth, atrophy,

and cachexia: By. Skeletal Muscle. 15(29)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Schiaffino S and Mammucari C: Regulation

of skeletal muscle growth by the IGF1-Akt/PKB pathway: Insights

from genetic models. Skelet Muscle. 1(4)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Rommel C, Bodine SC, Clarke BA, Rossman R,

Nunez L, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD and Glass DJ: Mediation of

IGF-1-induced skeletal myotube hypertrophy by PI(3)K/Akt/mTOR and

PI(3)K/Akt/GSK3 pathways. Nat Cell Biol. 3:1009–1013.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C,

Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH and Goldberg

AL: Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin

ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell.

117:399–412. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Wu Z, Woodring PJ, Bhakta KS, Tamura K,

Wen F, Feramisco JR, Karin M, Wang JY and Puri PL: p38 and

extracellular signal-regulated kinases regulate the myogenic

program at multiple steps. Mol Cell Biol. 20:3951–3964.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Zetser A, Gredinger E and Bengal E: p38

mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway promotes skeletal muscle

differentiation. Participation of the Mef2c transcription factor. J

Biol Chem. 274:5193–5200. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Chauhan A: Nutrition and health benefits

of hemp-seed protein (Cannabis sativa L.). Pharma

Innovation. 10:16–19. 2021.

|

|

59

|

Jeromson S, Gallagher IJ, Galloway SDR and

Hamilton DL: Omega-3 fatty acids and skeletal muscle health. Mar

Drugs. 13:6977–7004. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Hnia K, Gayraud J, Hugon G, Ramonatxo M,

De La Porte S, Matecki S and Mornet D: L-arginine decreases

inflammation and modulates the nuclear factor-kappaB/matrix

metalloproteinase cascade in mdx muscle fibers Am J. Pathol.

172:1509–1519. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Greene JM, Feugang JM, Pfeiffer KE, Stokes

JV, Bowers SD and Ryan PL: L-arginine enhances cell proliferation

and reduces apoptosis in human endometrial RL95-2 cells. Reprod

Biol Endocrinol. 11(15)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Jin CL, Ye JL, Yang J, Gao CQ, Yan HC, Li

HC and Wang XQ: mTORC1 mediates lysine-induced satellite cell

activation to promote skeletal muscle growth. Cells.

8(1549)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

63

|

Sun X, Sun Y, Li Y, Wu Q and Wang L:

Identification and characterization of the seed storage proteins

and related genes of Cannabis sativa L. Front Nutr.

8(678421)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Barakat H and Aljutaily T: Hemp-based meat

analogs: An updated review on nutritional and functional

properties. Foods. 14(2835)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Joung YH, Lim EJ, Darvin P, Chung SC, Jang

JW, Park KD, Lee HK, Kim HS, Park T and Yang YM: MSM enhances GH

signaling via the Jak2/STAT5b pathway in osteoblast-like cells and

osteoblast differentiation through the activation of STAT5b in

MSCs. PLoS One. 7(e47477)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|