Introduction

South Africa is facing a fourfold burden of health

issues including maternal, newborn and child health conditions,

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency

syndrome (AIDS) and tuberculosis (TB), non-communicable diseases

(NCDs), alongside violence and injuries (1). Despite measures taken to curb these

infectious diseases, HIV/AIDS remain prominent globally, with South

Africa accounting for 20% of all new infections worldwide in 2021.

Moreover, the prevalence of HIV was increased from an estimated 13%

(~7.8 million) in 2020 to 13.9% in 2022 (8.45 million) in South

Africa (2). Having the largest

number of people enrolled on antiretroviral (ARV) therapy (ART)

worldwide, South Africa has been able to reduce premature deaths

from AIDS, increasing the life expectancy of people living with HIV

(PLWH). However, the ageing population of HIV-infected individuals

are more prone to cardiometabolic diseases (CMDs) and other

age-associated diseases including Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's

disease and cancer (3). CMDs are

the leading causes of mortality in the NCD category and include

diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension, cerebrovascular diseases, and

other forms of heart diseases such as cardiomyopathies, coronary

artery disease and heart failure (4).

The pathway linking HIV/AIDS and CMDs has previously

been investigated (5). The virus

activates inflammatory responses, cellular apoptosis and

mitochondrial dysfunction, which enhances the production of

proinflammatory cytokines [tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α,

interleukins (ILs) and C-reactive protein (CRP)], while suppressing

the release of the anti-inflammatory cytokine adiponectin, leading

to the development of insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, obesity and

DM (6). Conversely, ARVs, more

specifically non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors

(NNRTIs) and protease inhibitors (PIs) after long term use alter

glucose homeostasis, causing dyslipidemia, lipodystrophy and

mitochondrial dysfunction (6).

These dysregulations lead to the development of CMDs (7). The underlying pathways are regulated

by various genes, including the phospholipase A2 (PLA2)

gene.

The PLA2 gene belongs to the family of

phospholipases which encode for enzymes involved in the hydrolysis

of phospholipid substrates at specific sn-2 bonds to produce free

fatty acids and lysophospholipids. Among the free fatty acids,

arachidonic acid, which is a precursor of eicosanoids, including

the inflammatory markers prostaglandins and leukotrienes, is the

most widely produced. Several isoforms of the PLA2 enzyme have been

discovered with the secreted PLA2 (sPLA2) and cytosolic PLA2

(cPLA2) being the most studied (8).

These two differ in that, cPLA2 is specific to arachidonic acid

while sPLA2 produces various fatty acids (9). A total of about 14 isoforms of sPLA2

have been identified, with 10 characterized in the human genome

including group IB, IIA, IID-F, III, V, X, XIIA and XIIB (10).

Studies on the expression of sPLA2 have

mostly been carried out in knockout mice and other animal models

with the expression of sPLA2 group IIA observed to be

upregulated by IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, lipopolysaccharides (LPS)

(11,12) and a high fat diet (HFD) in male

Wistar rats (13). When the

phospholipase A2 group IIA (PLA2G2A) inhibitor KH064 was

administered orally to these rats, there was a reduction in weight

gain, fat mass and improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin

sensitivity, indicating that the increase in expression was

associated with metabolic abnormalities (13). However, overexpression of human

PLA2G2A in male C57BL/6 mice protected them from weight gain

on an HFD, enhanced energy expenditure and oxygen consumption, and

improved glucose clearance and insulin sensitivity, as determined

using glucose tolerance tests and insulin tolerance tests, thereby

alleviating obesogenic symptoms in response to an HFD (14,15).

While sPLA2 contributes to dyslipidemia, insulin resistance

and obesity through the breakdown of oxidized lipid contained in

low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

(16), cPLA2 contributes to

metabolic diseases through the expansion of lipid droplets and

adipogenesis (17,18). Therefore, alteration in the

expression of PLA2 genes will affect their corresponding

proteins and downstream targets, leading to the development of CMDs

(19).

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) is the most

common type of genetic variation among humans. It occurs when a

base in a given portion of a gene is substituted by another. These

changes have been shown to affect mRNA expression, modify the

activity of a protein, leading to the development of a disease.

Regarding PLA2, a previous study showed that SNPs of this gene are

associated with a lower risk of hypertension and CVD, weight loss

in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, stroke,

dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis (19). Specifically, the rs4744 SNP has been

associated with increased serum PLA2G2A levels and with increased

CVD events (20). However, there is

sparse literature from Africa despite the high prevalence of HIV

and cardiometabolic diseases. The present study therefore aimed to

examine the association of nine SNPs in the PLA2 gene

(PLA2G2A, PLA2G2C and PLA2G4E) with CMDs in

South African adults living with HIV infection.

Patients and methods

Study type and population

The present study was a cross-sectional study

consisting of 716 HIV-infected individuals aged ≥18 years and

receiving ART. The participants were recruited from primary health

care facilities in the Western Cape province of South Africa

between March 2014 and February 2015. A total of 42 facilities in

Cape Town and 20 in the surrounding rural municipalities met the

criteria of provision of ART to a minimum of 325 patients per month

and were included in the present study. Among these 62 facilities,

13 urban and 4 rural were randomly selected, with 15-60

participants recruited from each facility. Approval was obtained

from the South African Medical Research Council Ethics Committee

(approval no. EC021-11/2013) in Cape Town, South Africa and the

study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the

Declaration of Helsinki. The Health Research Office of the Western

Cape Department of Health and the selected healthcare facilities in

Cape Town, South Africa granted permission for the recruitment of

participants. Written informed consent was obtained from all

participants before inclusion in the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

HIV-positive adults (18 years and older) attending

facilities with directed HIV clinics, and who were willing to

participate and provided informed consent were included in the

present study. Participants were excluded from the study if they

were: Bedridden, patients with active malignancy or currently

undergoing treatment for malignancy, patients on chronic

corticosteroid treatment, pregnant or breastfeeding women, and

patients unwilling or unable to provide informed consent.

Data collection and sampling

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire

adapted from the WHO STEP-wise approach surveillance tool (21) was used for data collection. On

recruitment day, sociodemographic information, anthropometric and

blood pressure measurements, medical history of HIV infection

including duration of diagnosis of HIV infection, CD4 counts and

ARV regimen were recorded in the questionnaire by trained

fieldworkers. Socio-demographic information, medical history of HIV

infection, anthropometric and blood pressure measurements were

obtained as previously described (22). All participants who consented for

the study were invited for blood sample collection the following

day. Blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and tubes without

anti-coagulant after participants had fasted for at least 8 h, and

a portion was processed for biochemical analysis. Plasma glucose

(hexokinase method), serum creatinine (Cayman Chemical) and gamma

glutamyl transferase (Abcam) were measured using colorimetric

methods according to the manufacturers' protocols. Estimated

glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using the

IDMS-traceable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study

equation (23). Total cholesterol

(TC), HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) and triglycerides were measured in

serum samples by colorimetric methods using enzymatic techniques

(24-26),

LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) was calculated using the formula described

by Friedewald et al (27),

and non HDL-C was calculated using the formula: TC-HDL-C. Liver

function enzymes (alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase)

were quantified using standardized methods according to the

manufacturer's protocols (Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Inc.). All

colorimetric assays were performed using a Beckman Coulter AU 500

spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Plasma insulin was

quantified by chemiluminescence immunoassay (Human Insulin CLIA

kit; Abnova Corporation) and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was

determined using high-performance liquid chromatography in

accordance with the National Glycohaemoglobin Standardization

Programme. Highly sensitive CRP (hs-CRP), TNF-α, IL-2 and IL-10

were measured by ELISA (Biomatik kit). All biochemical analyses

were performed at an ISO 15189 accredited pathology laboratory

(PathCare, Reference Laboratory, Cape Town, South Africa) which had

no access to the clinical information of the participants.

The remaining portion of blood samples were frozen

at -80˚C for DNA extraction and SNP genotyping. DNA was extracted

from whole blood samples by the salt extraction method (28).

Genotyping of SNPs was carried out using the

TaqMan® Genotyping Master Mix Protocol from ThermoFisher

Scientific, Inc. A total of nine SNPs of the PLA2 gene were

genotyped (rs11573156, rs4744, rs10732279, rs6426616, rs2301475,

rs12139100, rs116431025, rs193222555 and rs149056482). The

PLA2 gene was selected as it encodes for enzymes which are

involved in the regulation of inflammation and have the potential

to be used as markers of respiratory, neurodegenerative and

cardiometabolic diseases (20). The

SNPs were selected from the dbSNP-polymorphism repository

(https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp). In

total, six secreted PLA2 SNPs (three PLA2G2A and

three PLA2G2C SNPs) and three cPLA2 SNPs (three

PLA2G4E SNPs), which are widely studied, and the minor

allele have been reported to be associated with increased or

reduced serum/activity levels (20,29,30).

A sufficient amount of PCR Master Mix (Applied

Biosystems®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) for the

requisite number of reactions was produced in a 1.5-ml tube

containing 5 µl of 2X Genotyping Mix (cat. no. 4381656; Applied

Biosystems®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 0.125 µl

of 40X SNP assay mix (cat. no. 4331349; Applied

Biosystems®; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.; containing

the forward and reverse primers specific for each SNP; Table I), and 2.875 µl ddH20 for

each reaction. The mixture was pulse vortexed and then briefly

centrifuged (1,000 x g for 30 sec at room temperature).

Subsequently, 8 µl of the Master Mix were pipetted into each of the

wells of the 96-well plate. Then, 2 µl of the template DNA sample

(5 ng/µl concentration) were pipetted into the appropriate well.

For quality control purposes, a non-template control was also

included in each PCR run, with 2 µl of ddH20 used in

place of template DNA. When all components of the PCR had been

pipetted into the appropriate wells, the 96-well plate was covered

with MicroAmp optical caps (Applied Biosystems®; Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and PCR was performed using Applied

Biosystems® Quant Studio™ 7 Flex Real-time PCR system

(ThermoFisher Scientific, Inc.) as follows: Initial denaturation at

95˚C for 10 min followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for

15 sec, annealing at 60˚C for 90 sec and extension at 60˚C for 90

sec.

| Table IPrimer sequences for SNP

genotyping. |

Table I

Primer sequences for SNP

genotyping.

| SNP | Forward primer

(5'-3') | Reverse primer

(5'-3') |

|---|

| rs11573156 |

TTGCATATCCCCACACTGGA |

TTGGTAGTCCCTTTGGGTGTG |

| rs4744 |

CTGAGACCTCTGCGCCCATC |

CCCATCACCAGACAACTCCCA |

| rs10732279 |

ATAACTGAGTGCGGCTTCCTT |

GGTAAGAGCTGACCCTGACCT |

| rs6426616 |

GGCCTGTTGGGGATGATCTG |

TCCTTAACCCTTGGCCCCTT |

| rs2301475 |

TGATAGACCCAGGACACAAAC |

CCTCCCCTGTCAAAGTCCAAA |

| rs12139100 |

CCCATCCTCCAAATCCCGTT |

CTAGCTGTGTTACAGGGGCA |

| rs193222555 |

CTTCTTCTCCACTGCGAGCC |

TACTGTGCTTGGTGCTAGGG |

| rs149056482 |

GCTCACCTGGTGCCTTGTATTT |

GCTGAGTTGTTAGCTGGGGAA |

| rs116431025 |

TGGGAAGAAAGTCACGATGGG |

GCTGAGTTGTTAGCTGGGGA |

Genotypes were confirmed by randomly selecting 20

samples which were sequenced by Inqaba Biotec using the Sanger

sequencing method. The chromatograms showing the GG, GA and AA

genotypes of the rs4744 SNP are provided as Fig. S1, Fig.

S2 and Fig. S3,

respectively.

Calculations and definitions

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight

(kg)/height (m2). Participants were categorized

according to BMI as normal weight (BMI <25 kg/m2),

overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and BMI <30

kg/m2) and obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) (31). Central obesity was determined using

the following criteria: Waist circumference (WC) >94 cm in men

and >80 cm in women (32).

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) ≥140 mmHg

or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥90 mmHg or known hypertension on

treatment (33). Dyslipidemia was

defined as TC >5 mmol/l, triglycerides >1.5 mmol/l, HDL-C

<1.2 mmol/l, LDL-C >3.0 mmol/l and non-HDL-C >3.37 mmol/l

or taking anti-lipid agents (34).

Diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l and/or

2-h post glucose load ≥11.1 mmol/l, previously diagnosed or taking

antidiabetic medications (35).

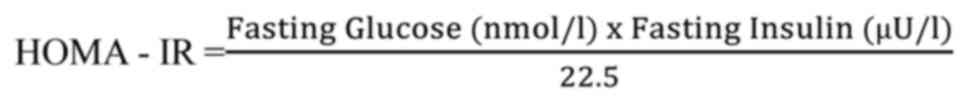

Insulin resistance (IR) was based on the homeostasis

model assessment (HOMA) using the formula:

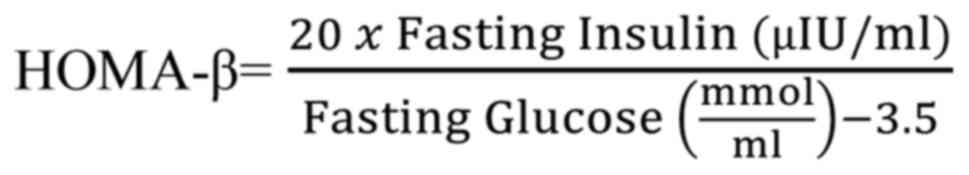

Beta cell function was determined by HOMA-β using

the formula (36):

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) was defined using the

Joint Interim Statement (JIS) criteria (37) when three of the following conditions

were met: i) A waist circumference ≥80 cm for women or ≥94 cm for

men; ii) triglyceride level ≥1.7 mmol/l; HDL-C level <1.04

mmol/l in men or <1.3 mmol/l in women; iii) high blood pressure

defined by SBP ≥130 mmHg and/or DBP ≥85 mmHg or receiving

hypertensive medication; and iv) fasting plasma glucose ≥5.6 mmol/l

or receiving diabetic medications.

The three genotypes were determined from the PCR

amplification output as follows: A sample was homozygous for the

dominant allele when amplification curves were observed only in the

VIC channel, amplification signal in the ROX channel was an

indication for homozygous recessive and amplification in both

channels was an indication of heterozygous genotype.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered onto an Excel spread sheet and

exported into the IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences

(SPSS) version 25 software (IBM Corp.) for analysis. Continuous

variables which were skewed, are reported as median (25-75th

percentile) and compared using the median test, while categorical

variables are reported as ratio and percentages and compared using

the chi squared test. Hardy Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed

for all nine SNPs, and the rs4744 which was in HWE was used for

further analysis. The interactions between genotypes of the rs4744

SNP and cardiometabolic risk profile were determined using linear

and logistic regression analysis, by incorporating the dominant,

recessive and additive models on the predictive variable, as well

as their interaction with age and sex. All analysis were carried

out at 95% confidence interval and a 2-tailed P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

General characteristics of study

participants

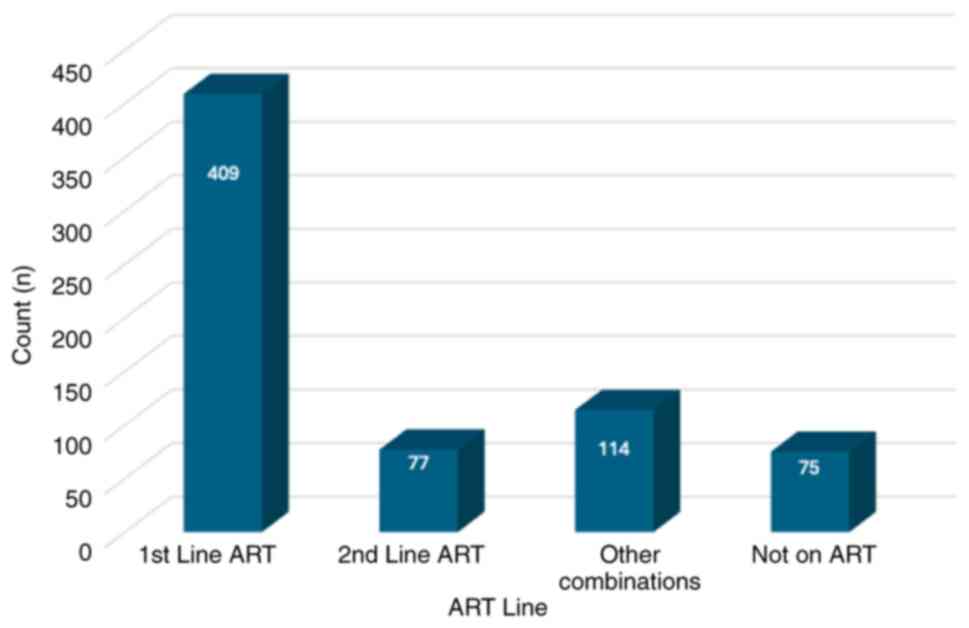

A total of 716 participants were involved in the

present study, with 72.9% being women and the median duration of

HIV was 60 months (25-75th percentile: 24-108) (Table II). The majority of participants

(60.6%, n=409) were on first-line ART, 11.4% (77 participants) were

on second-line ART, 16.9% (114 participants) were on other ART

combinations and 11.1% of participants (n=75) were not on HIV

medications (Fig. 1). The

prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2),

hypertension and metabolic syndrome were 8.5, 34.4, 24.2 and 27.5%,

respectively (Table II). Age,

weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, hip circumference,

waist-to-hip ratio, waist-to-height ratio, SBP, DBP, insulin,

homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR),

glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), and gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT)

were significantly higher in participants with MetS when compared

with those without MetS (Table

II). Moreover, the prevalence of MetS was significantly higher

amongst the female participants (31.0%) compared with the male

participants (16.9%); P<0.001 (Table II).

| Table IIClinical characteristics of study

participants across MetS status. |

Table II

Clinical characteristics of study

participants across MetS status.

|

Variablea | N | Total: 716

(100%) | With MetS: 197

(27.5%) | Without MetS: 519

(72.5%) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 716 | 38.0

(32.0-45.0) | 39.0

(34.0-45.5) | 37.0

(30.5-42.0) | <0.001 |

| Weight (kg) | 715 | 68.4

(58.1-81.8) | 80.0

(70.3-93.5) | 65.9

(56.0-80.3) | <0.001 |

| Height (cm) | 715 | 160.6

(156.0-166.3) | 161.3

(156.4-165.6) | 160.1

(155.5-165.1) | 0.012 |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 715 | 26.3

(22.1-32.1) | 30.5

(27.5-36.3) | 24.9

(21.5-31.7) | <0.001 |

| Waist circumference

(cm) | 715 | 88.0

(77.5-98.0) | 98.5

(92.6-106.8) | 84.7

(76.5-96.3) | <0.001 |

| Hip circumference

(cm) | 715 | 102.1

(92.6-112.1) | 109.2

(103.0-120.2) | 100.5

(92.0-111.3) | <0.001 |

| Waist to hip

ratio | 715 | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | 0.9 (0.8-1.0) | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) | <0.001 |

| Waist to height

ratio | 715 | 0.6 (0.5-0.6) | 0.6 (0.6-0.7) | 0.5 (0.5-0.6) | <0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 715 | 117.0

(107.0-129.5) | 124.3

(116.0-135.8) | 114.0

(105.0-124.3) | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 725 | 82.0

(75.0-90.5) | 89.8

(82.3-97.3) | 80.3

(73.5-86.5) | <0.001 |

| Heart rate

(beats/min) | 725 | 74.5

(66.5-82.5) | 76.0

(70.0-82.8) | 75.0

(67.0-82.5) | 0.016 |

| CD4 count

(cells/mm3) | 371 | 395.0

(241.0-604.0) | 429.5

(275.0-670.5) | 358.0

(225.0-558.0) | 0.187 |

| HIV diagnosis

(duration in months) | NA | 60.0

(24.0-108.0) | 74.5

(48.0-120.0) | 53.0

(24.0-96.0) | <0.001 |

| Alanine

transaminase (IU/l) | 712 | 23.0

(17.0-34.0) | 24.0

(17.5-36.5) | 22.0

(16.0-32.0) | 0.132 |

| Aspartate

transaminase (IU/l) | 712 | 29.0

(24.0-38.0) | 29.5

(24.0-37.5) | 29.0

(24.5-38.0) | 0.916 |

| Total cholesterol

(mmol/l) | 711 | 4.3 (3.7-5.1) | 4.3 (3.7-5.0) | 4.4 (3.8-5.2) | 0.024 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 711 | 1.3 (1.0-1.5) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.4 (1.1-1.7) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides

(mmol/l) | 710 | 1.0 (0.8-1.4) | 1.2 (0.9-1.8) | 0.9 (0.7-1.2) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 711 | 2.5 (2.0-3.1) | 2.5 (2.1-3.2) | 2.5 (2.0-3.0) | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C

(mmol/l) | 665 | 3.0 (2.5-3.7) | 3.1 (2.6-3.8) | 3.0 (2.4-3.5) | <0.001 |

| Glucose

(mmol/l) | 711 | 5.0 (4.6-5.4) | 5.3 (4.7-6.0) | 4.9 (4.6-5.2) | <0.001 |

| Insulin (µU/l) | 679 | 6.1 (4.0-9.6) | 8.3 (6.0-12.3) | 5.4 (3.6-8.8) | <0.001 |

| HOMA-β

(µU/mmol) | 677 | 81.3

(48.6-130.1) | 99.2

(55.6-155.7) | 81.0

(49.7-120.8) | 0.220 |

| HOMA-IR (µU x

mmol/l2) | 678 | 1.4 (0.9-2.3) | 2.0 (1.4-3.4) | 1.2 (0.8-1.9) | <0.001 |

| HbA1c (%) | 712 | 5.4 (5.2-5.7) | 5.6 (5.3-6.0) | 5.4 (5.2-5.7) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine

(µmol/l) | 710 | 58.0

(51.0-67.0) | 59.5

(51.0-65.5) | 58.0

(51.0-66.0) | 0.456 |

| GGT (U/l) | 711 | 39.0

(26.0-66.0) | 47 (26.5-73.5) | 37 (24.0-61.0) | 0.019 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l) | 711 | 5.4 (2.4-14.0) | 6.4 (2.8-15.4) | 5.0 (1.7-12.3) | 0.075 |

| INF-γ (pg/ml) | 660 | 14 (12-16) | 13.5

(12.0-16.0) | 14 (12.0-16.0) | 0.104 |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 660 | 18 (14.5-24) | 17 (14.0-22.0) | 18.5 (14.8-25) | 0.062 |

| 1L-2 (pg/ml) | 660 | 9.5 (9-10) | 9 (9-10) | 9.5 (9-10) | 0.402 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 660 | 19 (15-23.5) | 19 (15.5-22.5) | 19 (15-24) | 0.954 |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 701 | 91.0

(91.0-91.0) | 91.0

(91.0-91.0) | 91.0

(91.0-91.0) | NA |

| Sex | | | | | <0.001 |

|

Female | 710 | 562 (79.2) | 174 (31.0) | 388 (69.0) | |

|

Male | | 148 (20.8) | 25 (16.9) | 123 (83.1) | |

| Obese (BMI ≥30

kg/m2) | 715 | 246.0 (34.4) | 107.0 (54.3) | 139.0 (26.8) | <0.001 |

| WC (cm): men

>94; women >80 | 715 | 440.0 (61.5) | 186.0 (94.4) | 254.0 (49.0) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 715 | 173.0 (24.2) | 75.0 (38.1) | 98.0 (18.9) | <0.001 |

| Type 2

diabetes | 709 | 60 (8.5) | 46 (23.1) | 14 (2.7) | <0.001 |

| Hyperglycemia | 711 | 148.0 (20.8) | 100.0 (50.8) | 48.0 (9.3) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol

>5.0 mmol/l | 711 | 181.0 (25.5) | 55.0 (28.1) | 126.0 (24.5) | 0.325 |

| HDL-C <1.2

mmol/l | 711 | 265.0 (37.3) | 115.0 (58.7) | 150.0 (29.1) | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides

>1.5 mmol/l | 710 | 129.0 (18.2) | 85.0 (43.4) | 44.0 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| LDL-C >3.0

mmol/l | 711 | 199.0 (28.0) | 81.0 (41.3) | 118.0 (22.9) | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL-C >3.37

mmol/l | 665 | 243.0 (36.5) | 94.0 (50.5) | 149.0 (31.1) | <0.001 |

Genotypic distribution and minor

allele frequency of single nucleotide polymorphisms

The genotypic distribution and minor allele

frequency of the nine SNPs are presented in Table III. The percentage of successful

genotyping of the nine SNPs ranged between 82.3 and 98.6%. All

three genotypes were present for rs11573156 (C/G), rs4744 (G/A),

rs10732279 (A/G), rs6426616 (G/A), rs2301475 (A/G), rs12139100

(C/T), rs193222555 (T/C) and rs149056482 (T/C), while rs116431025

(C/T) contained the CC and CT genotype. Amongst the nine SNPs

investigated, only rs4744 was in HWE (Table III). All the other eight SNPs

significantly deviated from HWE (all P<0.001). Although positive

controls were used during genotyping and the genotypes were

confirmed by sequencing 20 samples, the absence of genotyping error

or copy number variation for SNPs deviating from HWE cannot be

excluded. As such, SNPs not in HWE were excluded from further

analysis, and only rs4744 was investigated on its association with

cardiometabolic diseases.

| Table IIIFrequency of the PLA2 gene SNP

genotypes and minor allele frequency. |

Table III

Frequency of the PLA2 gene SNP

genotypes and minor allele frequency.

| SNP | Homozygous for

major allele, n (%) | Heterozygous, n

(%) | Homozygous for

minor allele, n (%) | Minor allele

frequency (%) | Deviation from HWE

(P-value) |

|---|

| rs11573156

(n=589) | 304.0 (51.6) | 283.0 (48.1) | 2.0 (0.3) | 24.4 | <0.0001 |

| rs4744 (n=661) | 549.0 (83.1) | 106.0 (16.0) | 6.0 (0.9) | 8.9 | 0.940 |

| rs10732279

(n=702) | 312.0 (44.4) | 379.0 (54.0) | 11.0 (1.6) | 28.0 | <0.0001 |

| rs6426616

(n=684) | 50.0 (7.3) | 580.0 (84.8) | 54.0 (7.9) | 49.7 | <0.0001 |

| rs2301475

(n=688) | 313.0 (45.5) | 333.0 (48.4) | 42.0 (6.1) | 30.3 | 0.00067 |

| rs12139100

(n=703) | 346.0 (49.2) | 344.0 (48.9) | 13.0 (1.9) | 26.1 | <0.0001 |

| rs116431025

(n=680) | 273.0 (40.1) | 407.0 (59.9) | 0.0 (0.0) | 29.9 | <0.0001 |

| rs193222555

(n=694) | 4.0 (0.6) | 349.0 (50.3) | 341.0 (49.1) | 25.7 | <0.0001 |

| rs149056482

(n=706) | 5.0 (0.7) | 445.0 (63.0) | 256.0 (36.3) | 32.3 | <0.0001 |

Participants characteristics across

rs4744 genotypes

In the present study, 647 participants with

anthropometric and biochemical measurements were successfully

genotyped for rs4744. The GG genotype was the most prevalent

representing 83.1% followed by the heterozygous GA representing

16.0%, while the AA genotype was found in 0.9% of the participants

(Table III). When clinical

measurements were compared across genotypes of the rs4744 SNP of

the PLA2G2A gene, the recessive AA genotype was associated

with low median HDL-C (P=0.044), high median TNF-α (P=0.041), HDL-C

<1.2 mmol/l (P=0.023) and the dominant GG genotype was

associated with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (P=0.037), while no

significant differences were observed with all other measurements

(Table IV). No significant

differences were observed with type 2 diabetes and traits of

dysglycemia, high blood pressure and other markers of dyslipidemia

between the genotypes (Table

IV).

| Table IVClinical characteristics compared

across PLA2G2A rs4744 genotypes. |

Table IV

Clinical characteristics compared

across PLA2G2A rs4744 genotypes.

|

Variablea | N | GG (n=536) | AA (n=6) | GA (n=105) | P-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 716 | 37.5

(31.0-43.0) | 46.0

(37.0-55.0) | 36.0

(31.0-43.0) | 0.350 |

| Weight (kg) | 715 | 71.3

(59.2-88.4) | 73.3

(73.2-73.5) | 67.5

(56.2-84.6) | 0.165 |

| Height (cm) | 715 | 160.8

(155.7-165.5) | 165.9

(160.6-171.3) | 159.9

(156.8-163.5) | 0.898 |

| BMI

(kg/m2) | 715 | 27.7

(22.9-33.7) | 26.7

(25.0-28.4) | 27.6

(21.8-31.8) | 0.202 |

| Waist circumference

(cm) | 715 | 89.5

(79.5-101.6) | 95.5

(91.5-99.5) | 88.0

(78.2-97.8) | 0.325 |

| Hip circumference

(cm) | 715 | 104.5

(94.4-115.7) | 107.23

(100.3-114.3) | 103.0

(90.5-111.3) | 0.081 |

| Waist to hip

ratio | 715 | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | 0.9 (0.8-0.9) | 0.8 (0.8-0.9) | 8.813 |

| Waist to height

ratio | 715 | 0.6 (0.5-0.6) | 0.6 (0.6-0.6) | 0.6 (0.5-0.6) | 0.438 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 715 | 117.0

(107.5-128.5) | 120.8

(114.5-127.0) | 112.8

(104.0-124.0) | 0.263 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 725 | 82.5

(75.5-89.5) | 83.8

(80.0-87.5) | 82.0

(71.5-88.5) | 0.185 |

| Heart rate

(beats/min) | 725 | 75.3

(67.5-81.5) | 71.5

(67.0-76.0) | 78.0

(66.5-85.5) | 0.176 |

| CD4 count

(cells/mm3) | 371 | 375.0

(229.0-594.0) | 660.0

(476.0-884.0) | 408.5

(254.0-545.0) | 0.358 |

| Duration of HIV in

months | 659 | 60 (24-108) | 66.0 (12-84) | 60 (36-96) | 0.846 |

| Alanine

transaminase (IU/l) | 712 | 23.0

(17.0-34.0) | 19.0

(16.0-22.0) | 23.0

(16.0-34.0) | 0.790 |

| Aspartate

transaminase (IU/l) | 712 | 30.0

(25.0-38.0) | 26.5

(20.0-33.0) | 30.0

(24.0-37.0) | 0.619 |

| Total cholesterol

(mmol/l) | 711 | 4.4 (3.8-5.1) | 3.9 (3.4-4.4) | 4.3 (3.5-5.0) | 0.792 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 711 | 1.3 (1.1-1.6) | 1.2 (1.1-1.3) | 1.3 (1.0-1.5) | 0.044b |

| Triglycerides

(mmol/l) | 710 | 1.0 (0.8-1.3) | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) | 0.259 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 711 | 2.5 (2.0-3.1) | 2.2 (1.7-2.7) | 2.3 (1.9-2.8) | 0.531 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol

(mmol/l) | 665 | 3.0

(2.52-3.67) | 2.7 (2.2-3.1) | 2.9 (2.5-3.2) | 0.388 |

| Glucose

(mmol/l) | 711 | 5.0 (4.6-5.4) | 5.1 (4.5-5.6) | 4.9 (4.6-5.2) | 0.776 |

| Insulin (µU/l) | 679 | 6.2 (4.0-9.80) | 4.9 (3.6-6.1) | 5.4 (4.0-8.7) | 0.073 |

| HOMA-β

(µU/mmol) | 677 | 86.7

(50.0-130.8) | 78.1

(34.3-122.0) | 86.0

(60.0-145.0) | 0.247 |

| HOMA-IR (µIU x

mmol/l2) | 678 | 1.4 (0.9-2.3) | 1.1 (0.9-1.2) | 1.2 (0.9-1.8) | 0.207 |

| HbA1c (%) | 712 | 5.4 (5.2-5.7) | 5.4 (5.3-5.5) | 5.5 (5.2-5.6) | 0.693 |

| Creatinine

(µmol/l) | 710 | 58.0

(51.0-65.0) | 48.0

(44.0-52.0) | 56.0

(49.0-67.0) | 0.240 |

| GGT (U/l) | 711 | 39.0

(25.0-66.0) | 73.0

(19.0-127.0) | 27.0

(19.0-40.0) | 0.281 |

| hs-CRP (mg/l) | 711 | 5.1 (1.9-12.9) | 3.1 (2.0-4.2) | 4.8 (1.8-10.1) | 0.992 |

| INF-γ (pg/ml) | 613 | 14 (12-16.3) | 16 (11-17) | 13.5 (12-15) | 0.323 |

| IL-10 (pg/ml) | 613 | 18.5 (14.5-24) | 16 (16-43) | 18 (14-23) | 0.414 |

| 1L-2 (pg/ml) | 613 | 9.5 (9.5-10) | 9 (8.5-10) | 9 (9-10) | 0.882 |

| TNF-α (pg/ml) | 613 | 19 (15-23) | 22.5 (21.5-28) | 19 (16-23) | 0.041b |

| eGFR (ml/min) | 701 | 91.0

(91.0-91.0) | 91.0

(91.0-91.0) | 91.0

(87.0-91.0) | NA |

| Sex (Female) | 647 | 429 (80.0) | 6(100) | 79 (75.2) | 0.246 |

| BMI ≥30

kg/m2 | 646 | 195 (36.4) | 0 (0.0) | 27 (26.0) | 0.037b |

| WC (cm): men

>94; women >80 | 646 | 335 (62.5) | 3 (50.0) | 59 (56.7) | 0.459 |

| Hypertension | 646 | 144 (26.9) | 0 (0.0) | 30 (28.8) | 0.30 |

| Type 2

diabetes | 643 | 46 (8.6) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (6.7) | 0.367 |

| Total cholesterol

>5.0 mmol/l | 643 | 138 (25.9) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (23.8) | 0.322 |

| HDL-C <1.2

mmol/l | 643 | 234 (44.0) | 6(100) | 47 (44.8) | 0.023b |

| Triglyceride

>1.5 mmol/l | 642 | 73 (13.7) | 2 (33.3) | 12 (11.4) | 0.297 |

| LDL-C >3.0

mmol/l | 643 | 150 (28.2) | 1 (16.7) | 28 (15.6) | 0.787 |

| Non HDL-C >3.37

mmol/l | 598 | 184 (37.2) | 2 (33.3) | 30 (30.9) | 0.49 |

Linear and logistic regression

analysis for the association of rs4744 SNP genotypes with

cardiometabolic traits

Linear regression adjusting for age, sex and BMI was

used to explore the relationship between the rs4744 recessive

genotype of the PLA2G2A gene and cardiometabolic traits. The

results showed that the recessive genotype was associated with

HDL-C (β=0.366; P=0.024) when compared with the homozygous dominant

genotype and (β=0.371; P=0.025) when compared with the heterozygous

genotype. There was no association between the genotypes and all

other cardiometabolic traits (Table

V).

| Table VSimple linear regression analysis of

rs4744 SNP genotypes and cardiometabolic traits. |

Table V

Simple linear regression analysis of

rs4744 SNP genotypes and cardiometabolic traits.

| Variable | Age | Sex

(Female=Reference) | BMI | rs4744 major | rs4744 hetero | R2 Model 1 | R2 Model 2 |

|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | 0.735

(0.079)a | 7.841

(1.941)a | 0.173 (0.113) | 0.586 (1.933) | 9.431 (7.439) | 0.002 | 0.155 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 0.275

(0.053)a | 2.466 (1.292) | 0.227

(0.075)b | 7.142 (4.951) | 0.972 (1.287) | 0.004 | 0.059 |

| TC (mmol/l) | 0.026

(0.004)a | -0.211

(0.109)c | 0.011 (0.006) | 0.615 (0.418) | -0.072 (0.109) | 0.002 | 0.06 |

| HDL-C (mmol/l) | 0.004

(0.02)c | -0.176

(0.042)a | -0.013

(0.002)a | 0.366

(0.162)c | 0.371

(0.165)c | 0.001 | 0.053 |

| TG (mmol/l) | 0.012

(0.003)a | 0.275

(0.063)a | 0.016

(0.004)a | -0.253 (0.241) | -0.068 (0.063) | -0.001 | 0.077 |

| LDL-C (mmol/l) | 0.020

(0.004)a | -0.110 (0.094) | 0.021

(0.005)a | 0.390 (0.395) | -0.077 (0.093) | 0.002 | 0.075 |

| Non HDL-C

(mmol/l) | 0.022

(0.004)a | -0.028 (0.101) | 0.025

(0.006)a | 0.233 (0.377) | -0.077 (0.102) | 0.000 | 0.072 |

| Glucose

(mmol/l) | 0.029

(0.007)a | 0.233 (0.181) | 0.038

(0.010)a | 0.310 (0.691) | -0.016 (0.180) | -0.002 | 0.040 |

| Insulin | -0.062 (0.032) | -0.961 (0.790) | 0.350

(0.045)a | 2.144 (3.198) | -1.480 (0.786) | 0.008 | 0.128 |

| HOMA-β | -0.627 (0.927) | -20.258

(22.993) | 4.495

(1.324)a | 19.828

(103.649) | -4.870

(22.878) | -0.003 | 0.011 |

| HOMA-IR | -0.004 (0.010) | -0.139 (0.239) | 0.104

(0.014)a | 0.540 (0.968) | -0.379 (0.238) | 0.005 | 0.166 |

| HbA1c | 0.015

(0.003)a | 0.086 (0.083) | 0.020

(0.005)a | -0.072 (0.318) | 0.046 (0.083) | -0.003 | 0.052 |

Binary logistic regression was used to examine

whether the recessive genotype of the rs4744 SNP of the

PLA2G2A gene could be used to predict CMDs and traits

including obesity, diabetes, hypertension, MetS or abnormal lipid

levels in the study population. The odds of prevalent MetS for

individuals with the recessive genotype were 7 times higher

(P=0.017) and 10 times higher (P=0.036) when compared with

individuals of the heterozygous genotype and dominant genotype,

respectively (Table VI). The odds

of dyslipidemia characterized by low HDL-C were 5 times higher for

individuals with the recessive genotype compared with those with

the heterozygous and dominant genotypes (P=0.049).

| Table VILogistic regression analysis of

rs4744 SNP genotypes and cardiometabolic diseases. |

Table VI

Logistic regression analysis of

rs4744 SNP genotypes and cardiometabolic diseases.

| Variable | Age | Sex

(Female=Reference) | BMI | rs4744 major | rs4744 hetero |

|---|

| Diabetes | 1.07

(1.03-1.10)a | 1.49

(0.68-3.26) | 1.07

(1.02-1.11)b | Undetermined | Undetermined |

| Obesity (WC) | 0.96

(0.92-0.99)b | 13.0

(5.37-31.5)a | 0.51

(0.45-0.58)a | 2.70

(0.09-85.6) | 3.53

(0.10-119.5) |

| Hypertension | 1.02

(1.04-1.08)a | 1.17

(0.85-2.21) | 1.02

(1.00-1.05) | Undetermined | Undetermined |

| MetS | 1.07

(1.04-1.09)a | 0.70

(0.39-1.27) | 1.13

(1.09-1.16)a | 0.14

(0.02-0.88)c | 0.10

(0.02-0.67)c |

| High TC

(mmol/l) | 1.05

(1.03-1.07)a | 0.89

(0.54-1.46) | 1.02

(0.99-1.05) | Undetermined | Undetermined |

| Low HDL-C

(mmol/l) | 0.98

(0.96-1.00)c | 2.54

(1.62-3.97)a | 1.05

(1.02-1.08)a | 0.19

(0.03-1.07)c | 0.19

(0.03-0.99)c |

| High TG

(mmol/l) | 1.05

(1.03-1.08)a | 3.08

(1.79-5.31)a | 1.06

(1.02-1.09)c | 0.19

(0.03-1.18) | 0.18

(0.03-1.20) |

| High LDL-C

(mmol/l) | 1.05

(1.03-1.07)a | 0.84

(0.51-1.38) | 1.04

(1.01-1.07)b | 1.52

(0.17-13.96) | 1.48

(0.16-14.05) |

| High non-HDL-C

(mmol/l) | 1.05

(1.03-1.07)a | 1.00

(0.63-1.61) | 1.04

(1.01-1.07)b | 0.85

(0.14-5.06) | 0.67

(0.11-4.19) |

Discussion

The present study sought to examine the association

between nine SNPs of the PLA2 gene and cardiometabolic

diseases including diabetes, obesity, hypertension and MetS in a

black South African population with HIV. This population consisted

of more female participants (79.3%) than male participants (20.7%),

a disparity which cannot be explained by the sex distribution in

Cape Town, where females comprised 51% and males 49% in

2015(38). The high representation

of females could result from the high prevalence of HIV as well as

the willingness of women to participate in research, and the

reluctance of providing blood samples by potential male

participants. The prevalence of these cardiometabolic diseases were

8.4, 34.4, 24.2 and 27.5% for diabetes, obesity, hypertension and

MetS, respectively. Amongst the nine SNPs examined, only the rs4744

SNP was in HWE equilibrium. Given that non-random mating and

genotyping errors may result to deviation from HWE and lead to

spurious associations, all SNPs not in HWE were not analyzed for

their association with cardiometabolic traits. As such, only rs4744

SNP of the PLA2G2A gene was investigated for its association

with cardiometabolic diseases. The recessive (AA) genotype of the

rs4744 SNP was significantly associated with low HDL-C and high

TNF-α levels. Moreover, linear and logistic regression adjusting

for age, sex and BMI revealed that carrying the AA genotype of the

SNP was associated with low HDL-C levels and an increased risk of

MetS.

Non-synonymous SNPs can influence the expression of

a gene and mRNA levels leading to an increase or a decrease in the

level of the translated protein/enzyme (30,39).

The association between SNPs in the PLA2 gene and its

corresponding enzyme activity has been extensively studied

(40-42).

In Caucasians with and without coronary artery disease (CAD) and

diabetes, two SNPs of the PLA2G2A gene (rs11573156, and

rs1774131 rare alleles) were associated with high enzyme activity

and three SNPs (rs3767221, rs3753827 and rs2236771 rare alleles)

were associated with low enzyme activities (40). Similarly, sPLA2-IIa levels were

almost 200% higher in carriers of the rs4744 recessive genotype

when compared with carriers of the wild type homozygous genotype in

patients with stable CAD (20).

Similarly, the rare allele of the rs11573156 SNP was associated

with high enzyme activity in French patients with myocardial

infarction (41). Moreover, altered

activities and levels of PLA2G2A proteins have been observed to be

associated with cardiometabolic traits and diseases including

dyslipidemia, insulin resistance (42), obesity, CVD, stroke and type 2

diabetes (43). Lower levels of

sPLA2 enzyme activity and sPLA2-IIA mass were associated with a

reduced risk of cardiovascular events in the general European

population (29). Similarly the A/A

genotype of rs4744 SNP was associated with a higher risk of acute

cardiovascular events (acute coronary syndrome, myocardial

infarction, coronary revascularization) (20). As such, changes in the expression of

genes resulting from SNPs could possibly alter downstream pathways

which are associated with the development of cardiometabolic

diseases. The present findings could therefore be indicative that

the recessive genotype of the rs4744 SNP of the PLA2G2A gene

alters downstream targets leading to the development of

dyslipidemia characterized by low HDL-C and MetS.

The various forms of the PLA2 gene have been

reported to be associated differently with insulin sensitivity and

adiposity. The expression of PLA2G1B and PLA2G2E was

shown to be positively associated with the risk of obesity and

insulin resistance (17,44). Similarly, an inhibitor of the

PLA2G2A gene reduced the overexpression of the gene and

attenuated visceral adiposity, and reversed most characteristics of

MetS, including insulin sensitivity, glucose intolerance and

cardiovascular abnormalities in male Wistar rats (13). Conversely, overexpression of

PLA2G2A improved insulin sensitivity, glucose tolerance, and

adiposity in IIA+ mice (mice expressing the human

PLA2G2A gene), indicating that the metabolic effect is

dependent on the SNP studied (44).

Given that rs4744 SNP has been associated with increased serum

PLA2G2A levels leading to the development of CVD (20), a similar mechanism might be

postulated in this present study whereby the recessive genotype

contributed to the dysregulation of the enzyme or activity level

leading to the development of MetS.

Another pathway through which the recessive genotype

of the rs4744 SNP of the PLA2G2A gene could increase the

risk of MetS is the inflammatory pathway and dyslipidemia. Notably,

100% of participants with the minor AA genotype had low HDL-C

levels, characteristic of dyslipidemia compared with 44% of the

major (GG) genotype carriers. The dyslipidemia could also result

from the ARVs, given that >80% of the study participants were on

either protease inhibitors, NRTIs, NNRTIs or a combination of these

ARVs, which contribute to abnormal lipid metabolism. Moreover, the

virus could contribute to increased inflammation in carriers of the

minor genotype. This is because the inflammatory marker, TNF-α was

higher in carriers of the recessive genotype when compared with

carriers of the dominant genotype. The absence of association with

IL-10 might indicate that the SNP investigated induced inflammation

by targeting the pro-inflammatory pathway without affecting the

anti-inflammatory pathway.

The limitations of the present study include the

small sample size and low representation of male participants. Due

to the limited sample size, only 6 participants with the recessive

genotype were genotyped, and none were found in the diabetes,

obesity, and hypertension group. As such, logistic regression to

predict diabetes, obesity, and hypertension could not be computed.

Furthermore, the present study did not assess the expression and

activity levels of serum PLA2G2A, making it impossible to establish

a correlation between the genotypes and the expression levels of

the enzyme. Moreover, the levels of prostaglandins and

leukotrienes, which are the main inflammatory markers produced from

hydrolysis of phospholipids by PLA2G2A enzymes, were not

determined. Additionally, the study only involved HIV participants,

limiting the possibility to explore and compare the effects between

HIV and non-HIV populations. Therefore, further studies to mitigate

these limitations are warranted.

In conclusion, in a black South African population

with HIV, the minor AA genotype of the rs4744 SNP of the

PLA2G2A gene could potentially contribute to cardiometabolic

risk evaluation. This minor genotype was revealed to be associated

with a high PLA2 enzyme activity level. In addition, this enzyme

mediates lipid signaling (20), and

in the South African population may contribute to CMDs by inducing

inflammation and dyslipidemia. Given that, to the best of our

knowledge, this is the first study to report such findings and no

independent validation was carried out, further studies in

independent cohorts are warranted to confirm these results, while

investigating other SNPs and protein expression levels.

Furthermore, functional studies in animal models will contribute to

identify the molecular pathways which may be essential in the

establishment of therapeutic targets.

Supplementary Material

Homozygous dominant GG genotype of the

rs4744 single nucleotide polymorphism.

Heterozygous GA genotype of the rs4744

single nucleotide polymorphism.

Homozygous recessive AA genotype of

the rs4744 single nucleotide polymorphism.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Grand Challenges

Canada, through the Global Alliance on Chronic Diseases Initiative

(Hypertension grant no. 0169-04); and the South African Medical

Research Council (SAMRC) through baseline allocation to the

Non-communicable Diseases Research Unit (NCDRU).

Availability of data and materials

The data SNP dataset is available at: https://esango.cput.ac.za/articles/dataset/_b_Investigating_PLA2G2A_SNPs_and_cardiometabolic_diseases_in_South_Africa_b_/29480720?file=55989242).

Authors' contributions

TEM and APK conceived the study and acquired the

funding. NEN performed the single nucleotide polymorphism

genotyping. NEN and UN confirm the authenticity of all the raw

data, performed the data analysis and interpretation, and wrote the

original draft of the manuscript. All authors participated in the

revision of the manuscript, and read and approved the final

version.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Approval was obtained from the South African Medical

Research Council Ethics Committee (approval no. EC021-11/2013) in

Cape Town, South Africa and the study was conducted in accordance

with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The Health

Research Office of the Western Cape Department of Health and the

selected healthcare facilities in Cape Town, South Africa granted

permission for the recruitment of participants. Written informed

consent was obtained from all participants before inclusion in the

study.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Pillay-van Wyk V, Msemburi W, Laubscher R,

Dorrington RE, Groenewald P, Glass T, Nojilana B, Joubert JD,

Matzopoulos R, Prinsloo M, et al: Mortality trends and

differentials in South Africa from 1997 to 2012: Second national

burden of disease study. Lancet Glob Health. 4:e642–e653.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Statistics South Africa: Mid-year

population estimates. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, pp1-50,

2022.

|

|

3

|

Coetzee L, Bogler L, De-Neve JW,

Bärnighausen T, Geldsetzer P and Vollme S: HIV, antiretroviral

therapy and non-communicable diseases in sub-Saharan Africa:

Empirical evidence from 44 countries over the period 2000 to 2016.

J Int AIDS Soc. 22(e25364)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Statistics South Africa: Mortality and

causes of death in South Africa: Findings from death notification.

Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, pp1-145, 2017.

|

|

5

|

Mohan J, Ghazi T and Chuturgoon AA: A

critical review of the biochemical mechanisms and epigenetic

modifications in HIV- and antiretroviral-induced metabolic

syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 22(12020)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Masuku SKS, Tsoka-Gwegweni J and Sartorius

B: HIV and antiretroviral therapy-induced metabolic syndrome in

people living with HIV and its implications for care: A critical

review. J Diabetol. 10:41–47. 2019.

|

|

7

|

Levitt NS, Peer N, Steyn K, Lombard C,

Maartens G, Lambert EV and Dave JA: Increased risk of dysglycaemia

in South Africans with HIV; especially those on protease

inhibitors. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 119:41–47. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Murakami M and Kudo I: Phospholipase A2. J

Biochem. 131:285–292. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Dennis EA, Cao J, Hsu YH, Magrioti V and

Kokotos G: Phospholipase A2 enzymes: Physical structure, biological

function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic

intervention. Chem Rev. 111:6130–6185. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Khan SA and Ilies MA: The phospholipase A2

superfamily: Structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and

pathologic roles. Int J Mol Sci. 24(1353)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Massaad C, Paradon M, Jacques C, Salvat C,

Bereziat G, Berenbaum F and Olivier JL: Induction of secreted type

IIA phospholipase A2 gene transcription by interleukin-1beta. Role

of C/EBP factors. J Biol Chem. 275:22686–22694. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee C, Park DW, Lee J, Lee TI, Kim YJ, Lee

YS and Baek SH: Secretory phospholipase A2 induces apoptosis

through TNF-alpha and cytochrome c-mediated caspase cascade in

murine macrophage RAW 264.7 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 536:47–53.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Iyer A, Lim J, Poudyal H, Reid RC, Suen

JY, Webster J, Prins JB, Whitehead JP, Fairlie DP and Brown L: An

inhibitor of phospholipase A2 group IIA modulates adipocyte

signaling and protects against diet-induced metabolic syndrome in

rats. Diabetes. 61:2320–2329. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kuefner MS, Pham K, Redd JR, Stephenson

EJ, Harvey I, Deng X, Bridges D, Boilard E, Elam MB and Park EA:

Secretory phospholipase A2 group IIA modulates insulin

sensitivity and metabo. J Lipid Res. 58:1822–1833. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Kuefner MS, Deng X, Stephenson EJ, Pham K

and Park EA: Secretory phospholipase A2 group IIA

enhances the metabolic rate and increases glucose utilization in

response to thyroid hormone. FASEB J. 33:738–749. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Sato H, Taketomi Y, Ushida A, Isogai Y,

Kojima T, Hirabayashi T, Miki Y, Yamamoto K, Nishito Y, Kobayashi

T, et al: The adipocyte-inducible secreted phospholipases PLA2G5

and PLA2G2E play distinct roles in obesity. Cell Metab. 20:119–132.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Guijas C, Rodríguez JP, Rubio JM, Balboa

MA and Balsinde J: Phospholipase A2 regulation of lipid droplet

formation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1841:1661–1671. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Peña L, Meana C, Astudillo AM, Lordén G,

Valdearcos M, Sato H, Murakami M, Balsinde J and Balboa MA:

Critical role for cytosolic group IVA phospholipase A2 in early

adipocyte differentiation and obesity. Biochim Biophys Acta.

1861:1083–1095. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Khan MI and Hariprasad G: Human secretary

phospholipase A2 mutations and their clinical implications. J

Inflamm Res. 13:551–561. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Breitling LP, Koenig W, Fischer M, Mallat

Z, Hengstenberg C, Rothenbacher D and Brenner H: Type II secretory

phospholipase A2 and prognosis in patients with stable coronary

heart disease: Mendelian randomization study. PLoS One.

6(e22318)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

World health Organization: Noncommunicable

Disease Surveillance, Monitoring and Reporting: STEPwise approach

to NCD risk factor surveillance (STEPS). https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/steps.

Accessed January 13, 2014.

|

|

22

|

Ngwa NE, Peer N, Matsha TE, de-Villiers A,

Sobngwi E and Kengne AP: Associations of leucocyte telomere length

with cardio-metabolic risk profile in a South African HIV-infected

population. Medicine (Baltimore). 101(5e28642)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

National Kidney Foundation. K/DOQI

clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease:

Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 39

(2 Suppl 1):S1–S266. 2002.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Allain CC, Poon LS, Chan CS, Richmond W

and Fu PC: Enzymatic determination of total serum cholesterol. Clin

Chem. 20:470–475. 1974.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Jabbar J, Siddique I and Qaiser R:

Comparison of two methods (precipitation manual and fully automated

enzymatic) for the analysis of HDL and LDL cholesterol. J Pak Med

Assoc. 56:59–61. 2006.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Mcgowan MW, Artiss JD, Strandbergh DR and

Zak BA: Peroxidase-coupled method for the colorimetric

determination of serum triglycerides. Clin Chem. 29:538–542.

1983.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Friedewald WT, Levy RI and Fredrickson DS:

Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein

cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative

ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 18:499–502. 1972.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Miller SA, Dykes DD and Polesky HF: A

simple salting out procedure for extracting DNA from human

nucleated cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 16(1215)1988.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Holmes MV, Simon T, Exeter HJ, Folkersen

L, Asselbergs FW, Guardiola M, Cooper JA, Palmen J, Hubacek JA,

Carruthers KF, et al: Secretory phospholipase A2-IIA and

cardiovascular disease: A Mendelian randomization study. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 62:1966–1976. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Akinkuolie AO, Lawler PR, Chu AY,

Caulfield M, Mu J, Ding B, Nyberg F, Glynn RJ, Ridker PM,

Hurt-Camejo E, et al: Group IIA secretory phospholipase

A2, vascular inflammation, and incident cardiovascular

disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 39:1182–1190.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

No authors listed. Obesity: preventing and

managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. World

Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 894:i–xii, 1-253. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

World Health Organization (WHO). Waist

Circumference and Waist-Hip Ratio: Report of a WHO Expert

Consultation, Geneva, 8-11 December 2008. WHO, Geneva, 2011.

|

|

33

|

Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Rosei

EA, Azizi M, Burnier M, Clement DL, Coca A, de Simone G, Dominiczak

A, et al: 2018 ESC/ESH guidelines for the management of arterial

hypertension. Eur Heart J. 39:3021–3104. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Diagnosis management and prevention of the

common dyslipidaemias in South Africa-clinical guideline, 2000.

South African medical association and lipid and atherosclerosis

society of Southern Africa working group. S Afr Med J. 90:164–174,

176-178. 2000.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

35

|

World Health Organization (WHO):

Definition, diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus and

its complications. Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO, Geneva,

1999.

|

|

36

|

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS,

Naylor BA, Treacher DF and Turner RC: Homeostasis model assessment:

Insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma

glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia.

28:412–419. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet

PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, James WP, Loria CM, Smith

SC Jr, et al: Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim

statement of the international diabetes federation task force on

epidemiology and prevention; national heart, lung, and blood

institute; American heart association; world heart federation;

international atherosclerosis society; and international

association for the study of obesity. Circulation. 120:1640–1645.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Statistics South Africa: Mid-year

population estimates. Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, pp1-20,

2015.

|

|

39

|

Xu L, Zhou J, Huang S, Huang Y, Le Y,

Jiang D, Wang F, Yang X, Xu W, Huang X, et al: An association study

between genetic polymorphisms related to lipoprotein-associated

phospholipase A(2) and coronary heart disease. Exp Ther Med.

5:742–750. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Wootton PT, Drenos F, Cooper JA, Thompson

SR, Stephens JW, Hurt-Camejo E, Wiklund O, Humphries SE and Talmud

PJ: Tagging-SNP haplotype analysis of the secretory PLA2IIa gene

PLA2G2A shows strong association with serum levels of sPLA2IIa:

Results from the UDACS study. Hum Mol Genet. 15:355–361.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Simon T, Mallat Z, Kotti-Tounsi S,

Benessiano J, Lambeau G, Steg G, Allard-Latour G, Normand JP,

Bourlard P, Tedgui A, et al: Abstract 5908: Impact of Secretory

PLA2-IIa Gene Polymorphims on sPLA2 Activity and Cardiovascular

Events Following an AMI: Results From the French Registry of Acute

ST Elevation or Non-ST-elevation Myocardial Infarction (FAST-MI)

Registry. Circulation. 120 (Suppl 18)(S1174)2009.

|

|

42

|

Leinonen E, Hurt-Camejo E, Wiklund O,

Hultén LM, Hiukka A and Taskinen MR: Insulin resistance and

adiposity correlate with acute-phase reaction and soluble cell

adhesion molecules in type 2 diabetes. Atherosclerosis.

166:387–394. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Leinonen ES, Hiukka A, Hurt-Camejo E,

Wiklund O, Sarna SS, Mattson Hultén L, Westerbacka J, Salonen RM,

Salonen JT and Taskinen MR: Low-grade inflammation, endothelial

activation and carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes. J

Intern Med. 256:119–127. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Huggins KW, Boileau AC and Hui DY:

Protection against diet-induced obesity and obesity-related insulin

resistance in group 1B PLA2-deficient mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol

Metab. 283:E994–E1001. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|