Introduction

Acute coronary syndrome (ACS) is a fatal

manifestation of coronary heart disease (CAD) comprising three main

types: Unstable angina (UA), ST-elevated myocardial infarction

(STEMI), or non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

(1,2). ACS is primarily caused by plaque

rupture, erosion, and thrombosis (3,4),

leading to a significant reduction in coronary blood flow (5). A retrospective cohort study conducted

by Kaul et al (6) found that

patients with UA, STEMI and NSTEMI had a high likelihood of

developing heart failure (16, 23.4 and 25.4% respectively),

suggesting that ACS may be a significant risk factor for the

development of heart failure. Currently, although some treatments

have been proven effective for patients with ACS in clinical

practice, recurrent events and adverse effects, such as hypotension

and hyperkalemia, remain often unavoidable (7). Therefore, identifying effective

therapies with minimal side-effects to alleviate clinical symptoms

and improve the quality of life for patients with ACS is crucial

from both medical and socioeconomic perspectives.

Notably, 12/15-lipoxygenase (ALOX15), containing 13

introns and 14 exons, is mapped at LOX gene cluster on chromosome

17 and can encode arachidonic acid 12/15-lipoxygenase (12/15-LOX)

(8). It is acknowledged that

12/15-LOX is a type of dioxygenase enzyme, which is crucial in

incorporating oxygen into polyunsaturated fatty acids to generate

biologically-active peroxide products such as

13-hydroperoxy-octadecadienoic acid and

hydroperoxy-eicosatetraenoic acid (HPETE) (8). Reports on ALOX15 in ACS are currently

extremely limited. Research on ALOX15 in cardiac disorders has

mainly focused on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Previous

studies have demonstrated that 12/15-LOX plays an essential role in

inducing the transformation of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) into

atherosclerotic lesions, indicating that ALOX15 may possess

proatherogenic properties (9-11).

Ma et al (12) found that

ALOX15-induced peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty

acid-phospholipids increases the susceptibility to ferroptosis in

ischemia-induced myocardial damage (12). Similarly, Cai et al (13) proposed that ALOX15/HPETE-mediated

cardiomyocyte ferroptosis plays a crucial role in prolonged

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury (13). Additionally, ALOX15

activation-induced inflammation has been confirmed to be associated

with the development of heart failure (14). As early as 2013, Silbiger et

al (15) conducted a

transcriptional profiling analysis and indicated that ALOX15 is one

of the most significant gene expression biomarkers for the very

early stages of ACS (15). Notably,

our previous study indicated that ALOX15 can be regulated by the

long non-coding RNA ENST00000538705.1 to promote progression of ACS

(16), however the downstream

regulatory mechanisms of ALOX15 remain unclear.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3Ks) and their

downstream target serine/threonine kinase AKT (also known as

protein kinase B) are a conserved family of signal transduction

enzymes (17). Previous research

has increasingly revealed the crucial role of the PI3K/AKT

signaling pathway in cardiac disorders. For example, the

resveratrol-mediated activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway exerts

cardioprotection by reducing mitochondrial oxidative damage during

myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (18). By modulating the PI3K/AKT pathway,

Qingda granule can attenuate angiotensin II-induced cardiac

hypertrophy and apoptosis (19). In

a mouse model of myocardial infarction or heart failure, activation

of the PI3K/AKT pathway has been shown to promote angiogenesis and

provide cardioprotection (20,21).

However, whether the PI3K/AKT pathway plays a regulatory role in

ACS is still in the preliminary stage of exploration. Fibroblast

growth factor receptors (FGFRs), belonging to the transmembrane

tyrosine kinase receptor family, are strongly associated with

multiple cellular and biological processes such as cell growth,

migration, angiogenesis and wound repairment (22,23).

Currently, four main types of FGFRs have been identified, including

FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3 and FGFR4 (24,25).

Among these subtypes, FGFR2 plays a particularly essential role in

cell differentiation, growth and migration (26). It is widely reported that

endothelial dysfunction is strongly associated with the progression

of ACS (27). A recent study

conducted by Jiao et al (28) demonstrated that FGFR2 mediates

endothelial dysfunction by regulating the AKT/Nrf2/ARE signaling

pathway. Furthermore, inhibition of FGFR2 has been proposed as

therapeutic target for cardiac fibrosis (a hallmark pathological

feature following myocardial injury) (29). Notably, FGFR2 functioning as an

activator of the PI3K/AKT pathway has been widely reported in

numerous human diseases (30,31).

Currently, there are no relevant research studies on the

interaction between ALOX15 and the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

in the progression of ACS. Therefore, determining whether the

FGFR2/PI3K/AKT pathway, mediated by ALOX15, exerts regulatory

functions in the progression of ACS has sparked our great

interest.

In the present study, the effects of ALOX15 on human

primary coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs) were

investigated. In addition, a rat model of ACS was established. The

aim of the study was to preliminarily explore the downstream

regulatory mechanism of ALOX15 in ACS pathology.

Materials and methods

Patients

A total of 30 patients with ACS (15 women and 15

men; age range, 52-70 years; mean age, 60.5±6.4 years) were

admitted to The Third Affiliated Hospital of Shanghai University

(Wenzhou People's Hospital; Wenzhou, China). The inclusion criteria

were as follows: i) Diagnosis of UA, STEMI or NSTEMI; ii)

postoperative blood flow of the target vessel reaching thrombolysis

in myocardial infarction (TIMI) grade; iii) complete clinical

history available; iv) no surgical contraindications. The exclusion

criteria were as follows: i) Presence of congenital heart disease,

heart failure, or peripheral vascular diseases; ii) history of

prior cardiac surgery, such as coronary stent implantation or

coronary artery bypass; iii) recent history of infectious diseases;

iv) missing or incomplete case data, or lack of cooperation with

follow-up. Concurrently, 30 healthy controls (15 women and 15 men;

age range, 48-66 years; mean age, 56.7±6.4 years) were selected as

the physical examination population, with similar age and sex to

the experimental group, no symptoms of chest tightness and chest

pain, and no obvious abnormalities in biochemical tests,

electrocardiogram, chest CT, cardiac color Doppler ultrasound and

other imaging tests. Venous blood samples from patients with ACS

and healthy controls were collected, centrifuged at 3,000 x g at

4˚C for 5 min, and then stored at -80˚C for subsequent experiments.

The patients/participants provided their written informed consent

to participate in this study. The present study was conducted

according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and

approved (approval no. 2020-351) by the Ethics Committee of The

Third Affiliated Hospital of Shanghai University (Wenzhou People's

Hospital; Wenzhou, China).

Animals, cells and reagent

A total of 18 male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing

250-280 g (8 weeks old) was obtained from Vital River Laboratory

Animal Technology Co., Ltd. HCAECs (passage 2; cat. no. CP-H087)

and rat coronary artery endothelial cells (cat. no. CP-R081) were

purchased from Procell Life Science & Technology Co., Ltd.

Approval for the use of primary cells was obtained from the Ethics

Committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Shanghai University

(Wenzhou People's Hospital; Wenzhou, China). 293 cells were

obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Endothelial basal

medium 2 (EBM-2) and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from

Lonza Group, Ltd. The Cell Counting Kit-8 was provided by Abbkine

Scientific Co., Ltd. Small hairpin targeting ALOX15 (shRNA ALOX15),

negative control (shRNA NC), small interfering RNA (siRNA)1/2/3

ALOX15 along with their corresponding negative control (siRNA NC),

as well as pcDNA3.1-ALOX15 (OE-ALOX15), OE-FGFR2 and the pcDNA3.1

empty vector (OE-NC) were synthesized by Genomeditech (Shanghai)

Co., Ltd. The immunoprecipitation kit with protein A+G magnetic

beads (cat. no. P2179S), hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining

kit (cat. no. C0105S), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1; cat.

no. P5502), RIPA lysis buffer (cat. no. P0013B), ECL kit (cat. no.

P0018M) and BCA kit (cat. no. P0012) were obtained from Beyotime

Insitute of Biotechnology. Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd. supplied the

riboFECT™ mRNA transfection agent (cat. no. C11055-1).

Lipofectamine 3000 (cat. no. L3000150) was obtained from Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc. The total cholesterol (TC) content assay

kit (cat. no. BC1980) was acquired from Beijing Solarbio Science

& Technology Co., Ltd., while the high-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C) assay kit (cat. no. A112-1-1) and

low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) assay kit (cat. no.

A113-1-1) were sourced from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute. TRIzol reagent (cat. no. 10606ES60), Hifair®

Ⅱ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (cat. no. 11123ES60) and

Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (cat. no. 11202ES08)

were procured from Shanghai Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Primary

antibodies AKT (cat. no. 60203-2-Ig), phoshorylated (p)-AKT (cat.

no. 66444-1-Ig), GAPDH (cat. no. 60004-1-Ig) and HRP-conjugated

secondary antibodies (cat. no. SA00001-2) were obtained from

Proteintech Group, Inc. Primary antibodies p-PI3K (cat. no. 4228T)

and FGFR2 (cat. no. 23328) were purchased from Cell Signaling

Technology, Inc., and PI3K antibody (cat. no. ab191606) was sourced

from Abcam. ALOX15 antibody (cat. no. sc-133085) was obtained from

Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.

Cell culture

HCAECs were cultured in EBM-2 containing 15% FBS.

The culture cells were maintained in an environment with 5%

CO2 and a temperature of 37˚C. Cells in the logarithmic

growth phase were harvested for functional experiments.

Cell transfection and treatment

Cell transfection experiments were conducted in

strict compliance with the protocols of the riboFECT™ mRNA

transfection agent. Briefly, OE-ALOX15, OE-FGFR2, siRNA1/2/3 ALOX15

and their corresponding NCs (all, 50 nM) were individually

introduced into HCAECs using the riboFECT™ mRNA transfection agent

for 48 h at 37˚C. Following a 48-h period, the cells were collected

for the subsequent experiments. The sequences of siRNA1/2/3 ALOX15

and siRNA NC were as follows: siRNA1 ALOX15 forward,

5'-GUCGAUACAUCCUAUCUUCAATT-3' and reverse,

5'-UUGAAGAUAGGAUGUAUCGACTT-3'; siRNA2 ALOX15 forward,

5'-AUGACUUCAACCGGAUUUUCUTT-3' and reverse,

5'-AGAAAAUCCGGUUGAAGUCAUTT-3'; siRNA3 ALOX15 forward:

5'-CGCUAUCAAAGACUCUCUAAATT-3' and reverse,

5'-UUUAGAGAGUCUUUGAUAGCGTT-3'; siRNA NC forward,

5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3' and reverse:

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3'. Additionally, to ascertain the mutual

effect between ALOX15 and the PI3K/AKT pathway through reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR), scratch tests, CCK-8

assay and western blot analysis, 4 µl of PI3K/AKT pathway specific

agonist IGF-1 was added to HCAECs for 24 h at 37˚C.

RT-qPCR

The extraction of RNA was conducted with the aid of

TRIzol reagent. The concentration of total RNA was measured using a

NanoDrop™ 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

Total RNA (500 ng) was reversible transcribed into cDNA via

Hifair® II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix at 45˚C

for 45 min. Subsequently, PCR analysis was carried out in

accordance with the protocols of Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green

Master Mix. The reaction conditions were as follows: One cycle at

95˚C lasting 2 min, 40 cycles at 95˚C for 10 sec, 60˚C for 30 sec,

and 72˚C for 30 sec. The primers used in the present study are

listed in Table I. Relative mRNA

expression of ALOX15 and FGFR2 was normalized against GAPDH and

calculated with the 2-ΔΔCq method (32).

| Table IReverse transcription

quantitative-PCR primer synthesis list. |

Table I

Reverse transcription

quantitative-PCR primer synthesis list.

| Gene | Sequences | |

|---|

| ALOX15 | Forward |

5'-CCGCTGCTGTTTGTGAAACT-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-AGCGGTAACAAGGGAACCTG-3' |

| FGFR2 | Forward |

5'-TGACCAAACGTATCCCCCTG-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-GGTGTCTGCCGTTGAAGAGA-3' |

| GAPDH | Forward |

5'-TCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGG-3' |

| | Reverse |

5'-TCAAAGGTGGAGGAGTGGGT-3' |

Scratch tests

The transfected HCAECs were seeded in 6-well plates

at a density of 3x105 cells/well. Upon reaching 100%

confluence, a scratch was created in the monolayer using a pipette

tip (10 µl), and HCAECs were then incubated in a serum-free medium

for 48 h. The width of the scratches at both 0 h and 48 h was

recorded under a light microscope (Olympus Corporation). The

migratory abilities of HCAECs were analyzed with ImageTool software

version 1.46 (University of Texas Health Science Center at San

Antonio), employing the following formula: (The width at 0 h - the

width at 48 h)/the width at 0 h x 100%.

CCK-8 assay

HCAECs were inoculated into culture plates with

96-wells (4x103 cells/well) and subsequently cultured

for 24, 36, 48, and 72 h, respectively. A total of 10 µl of CCK-8

solution was added into each well and the cells were then incubated

for 2 h at 37˚C. Cell viability was then assessed using a

microplate reader (DR-3518G, Wuxi Hiwell Diatek Instruments, Co.,

Ltd.) at an absorbance of 450 nm.

Co-immunoprecipitation (CO-IP)

assay

For per IP reaction, 1 ml of lysis buffer was added

to HCAECs (2x107 cells) and incubated on ice for 30 min.

Following centrifugation at 14,000 x g for 20 min at 4˚C, the cell

lysates from HCAECs were collected, and the resulting supernatants

were incubated with 40 µl of a 1:1 slurry of Protein G-Sepharose

beads conjugated to rabbit anti-ALOX15 (5 µg) and anti-FGFR2 (5 µg)

antibodies at 4˚C overnight. Concurrently, an anti-IgG antibody (5

µg) was used as a control. The beads were then washed 5 times with

1 ml wash buffer and centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 1 min at 4˚C

between washes. After the final wash, the supernatant was removed,

and 30 µl of elution buffer was added in the samples and boiled at

95˚C for 5 min. Subsequently, the samples were subjected to

gradient SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to membranes. The

immunoprecipitates obtained were then analyzed by western

blotting.

Animal grouping and treatment

The ACS rat model was established based on

previously described protocols (33,34).

Approval for the use of animals was obtained from the Ethics

Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (Wenzhou, China). In these

previous studies, the modeling method for ACS closely resembled

that of acute myocardial infarction, as the latter is one of the

clinical manifestations of ACS. Sprague-Dawley rats were randomly

assigned to three groups: The sham group, the ACS model + shRNA NC

group, and the ACS model + shRNA ALOX15 group, with six rats in

each group. The rats were intraperitoneally injected with 50 mg/kg

of pentobarbital sodium for anesthesia. Their limbs were then

secured to a surgical table while maintaining them in a supine

position. Following thoracotomy, the heart was exposed and the

anterior descending coronary artery was ligated using 5/0 surgical

sutures. To prevent infection, penicillin (100,000 IU) was

subcutaneously injected into each rat. Meanwhile, only threading

was performed in rats in the sham group, without ligation. The

electrocardiogram results were recorded and the successfully

established ACS rat model was indicated as follows: ST segment

and/or high T wave was markedly elevated. A 3rd-generation system

was used and 9 µg lentiviral vectors were co-transfected into the

293 cells through Lipofectamine 3000 at room temperature. The rate

of lentiviral plasmid: packaging vector: envelope was 1:1:1.

Lentivirus-containing medium was collected 48 h after transfection

and used to infect rat coronary artery endothelial cells (passage

2; 5x106 cells/well) at a multiplicity of infection of

20. Subsequently, 48 h after lentiviral infection, 1 µg/ml

puromycin was used to select the infected cells. After 72 h, rats

in the ACS model + shRNA NC group received an intramyocardial

injection of shRNA NC (5'-GCTGTTCGATCGGGAAACA-3') integrated into

lentiviral vectors (50 µg), and those in the ACS model + shRNA

ALOX15 group were treated with lentivirus containing shRNA ALOX15

sequence (5'-GCTGATGCCTGATGGACAA-3') via intramyocardial injection.

After 2 weeks, the rats in the different groups were euthanized

with an overdose of pentobarbital sodium (200 mg/kg) via

intraperitoneal injection. Whole blood samples (from the eyeballs)

and heart were collected for subsequent tests. Animal experiments

were conducted in compliance with the Guidelines for the Use of

Laboratory Animals and approved (approval no. xmsq2023-1367) by the

Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (Wenzhou,

China).

Biochemical tests

The whole blood samples obtained from the eyeballs

of the rats were placed at room temperature for 2 h before being

centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 20 min at room temperature. Commercial

Kits were employed to determine the levels of TC, HDL-C and LDL-C

in serum using a fully automatic bio analysis machine.

H&E staining

Rat myocardial tissues were fixed in 4%

paraformaldehyde, deparaffinized and hydrated prior to paraffin

embedding. Subsequently, the tissues were sectioned into 4-µm thick

slices. The sections were stained with H&E for 3 min. Following

mounting with neutral gum, images were captured using an optical

microscope (OLYMPUS BX53; Olympus Corporation).

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were extracted from HCAECs or

myocardial tissues using RIPA lysis buffer and then measured the

concentration with a BCA Kit. All steps were conducted on ice.

Proteins (50 µg protein/lane) were then separated by 10% sodium

dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred

onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked

using 5% nonfat milk-Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 for 2

h at 25˚C, on which primary antibodies (ALOX15, 1:1,000; FGFR2,

1:1,000; PI3K, 1:1,000; p-PI3K, 1:1,000; AKT, 1:5,000; p-AKT,

1:2,000; GAPDH, 1:5,0000) were incubated overnight at 4˚C.

Subsequently, the corresponding secondary antibodies (1:1,000) were

added followed by incubation for 1 h at 37˚C. GAPDH was the

normalization for proteins. Protein signals were detected using an

ECL kit under Gel-Pro analyzer (version 4.0; Media Cybernetics,

Inc.).

Statistical analysis

In vitro experiments were performed in

triplicate, and each experiment was repeated 3 times. In

vivo experiments were performed using 6 rats per group.

Unpaired Student's t-test was adopted to gauge the differences

between two groups. The variations among multiple groups were

gauged by applying one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey's post hoc

multiple comparisons test. Data analysis was performed using SPSS

software v22.0 (IBM Corp.). The data were indicated as the mean ±

standard deviation. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

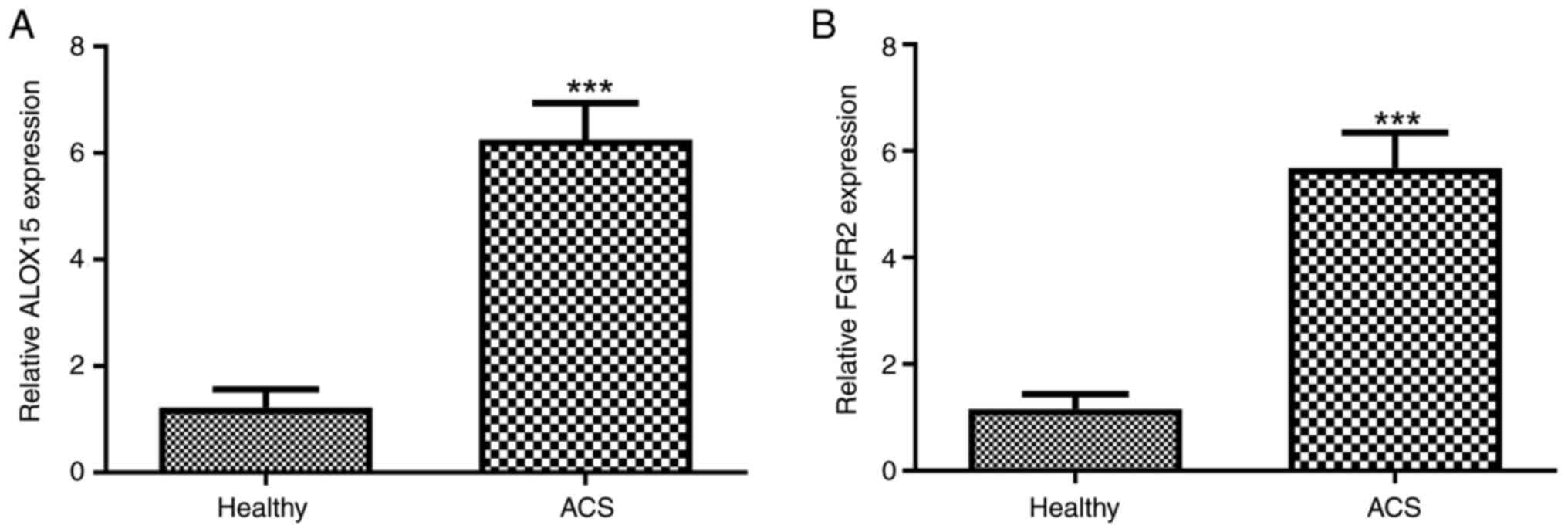

High expression of ALOX15 and FGFR2 is

observed in the serum of patients with ACS

After obtaining informed consent from the patients,

blood samples were collected from individuals diagnosed with ACS.

Following centrifugation, the expression levels of ALOX15 and FGFR2

in the serum of patients with ACS were assessed. As illustrated in

Fig. 1A, a significant upregulation

of ALOX15 expression in patients with ACS compared with healthy

individuals (P<0.001) was observed. Similarly, elevated levels

of FGFR2 were also detected in patients with ACS when compared with

healthy controls (Fig. 1B;

P<0.001).

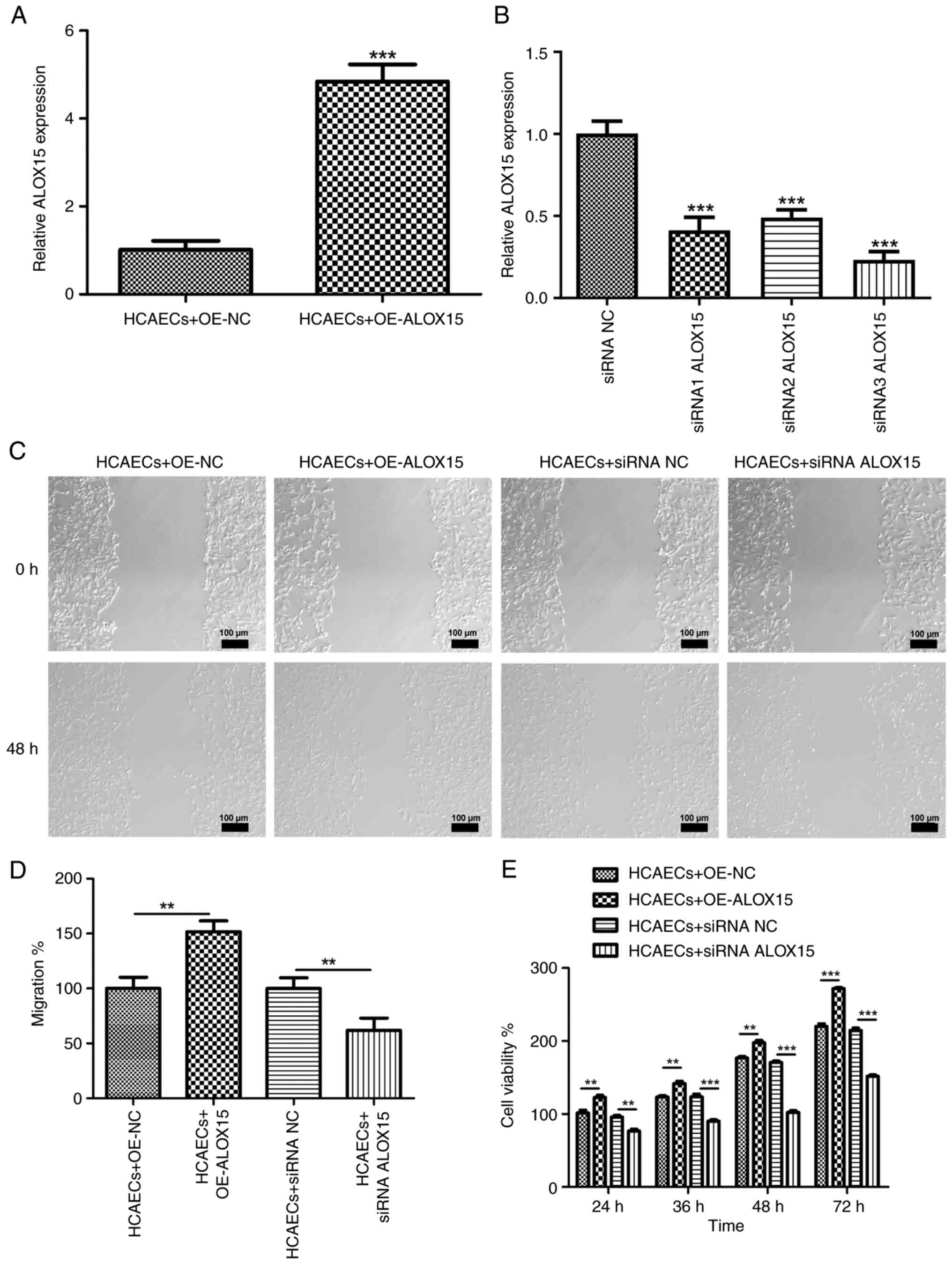

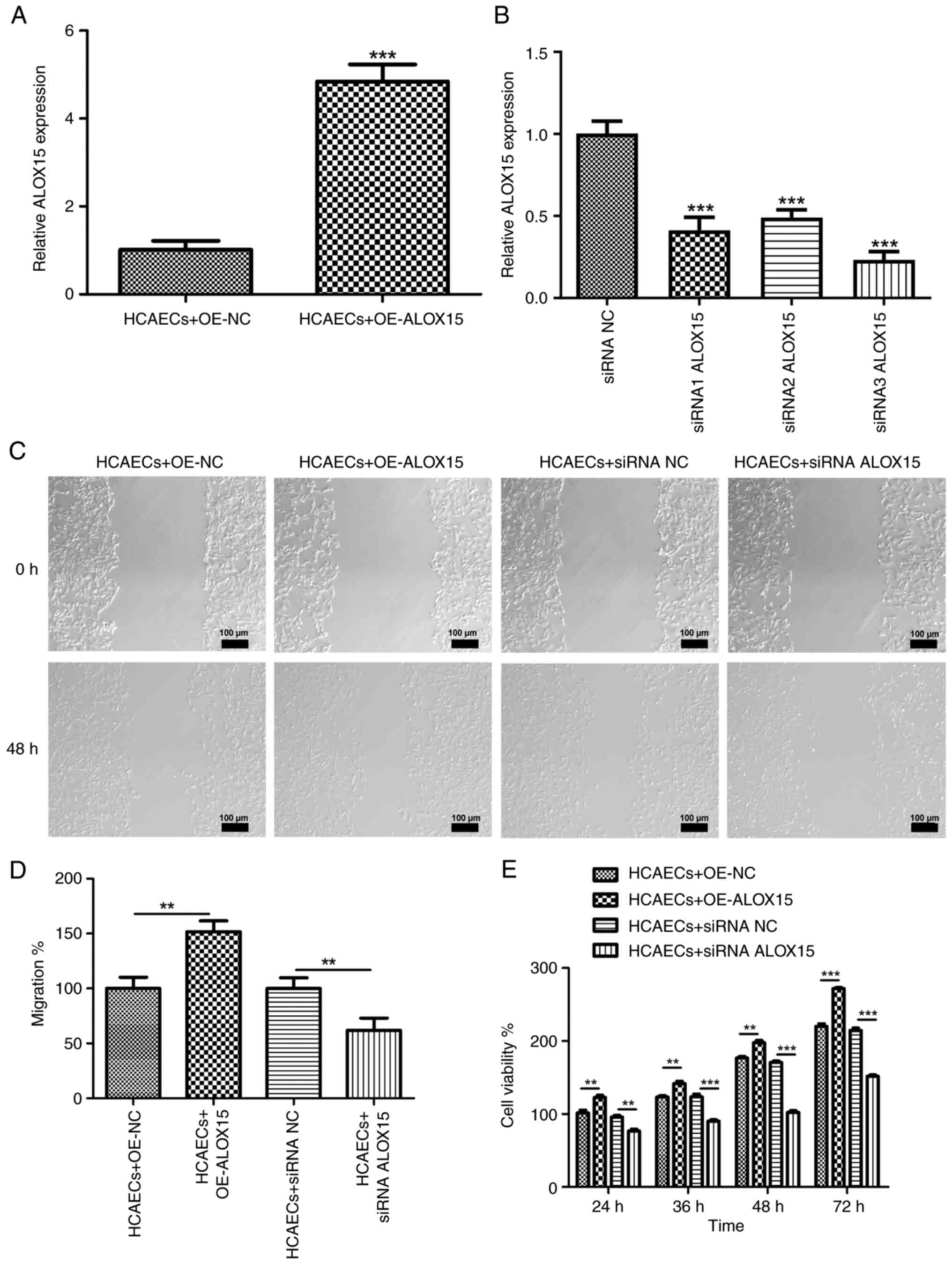

Effects of ALOX15 on ACS progression

in vitro

ALOX15 was then overexpressed or silenced to

evaluate its effects on the progression of ACS in vitro.

Following OE-ALOX15 transfection, the expression of ALOX15 in

HCAECs was significantly increased (Fig. 2A; P<0.001). Meanwhile, siRNA1

ALOX15, siRNA2 ALOX15 and siRNA3 ALOX15 were individually

transfected into HCAECs. As revealed in Fig. 2B, the expression levels of ALOX15

were significantly reduced after siRNA ALOX15 transfection

(P<0.001). Notably, siRNA3 ALOX15 was selected for the

subsequent experiments due to its relatively high transfection

efficiency. Wound healing assays were then performed and it was

revealed that the overexpressed ALOX15 significantly increased the

migratory abilities of HCAECs; conversely, silenced ALOX15

exhibited an inhibitory effect on migration in these cells

(Fig. 2C and D; P<0.01). Moreover, CCK-8 asays showed

that the proliferative ability of HCAECs were increased following

OE-ALOX15 transfection, but attenuated after siRNA ALOX15

treatment, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2E; P<0.01).

| Figure 2Effects of ALOX15 on acute coronary

syndrome progression in vitro. (A) The expression of ALOX15

in HCAECs after transfection with OE-ALOX15 or OE-NC was detected

by RT-qPCR. ***P<0.001 vs. HCAECs + OE-NC. (B) The

expression of ALOX15 in HCAECs after transfection with siRNA1

ALOX15, siRNA2 ALOX15, siRNA3 ALOX15 or siRNA NC was detected by

RT-qPCR. ***P<0.001 vs. siRNA NC. (C and D) The

migration of HCAECs transfected with OE-ALOX15/OE-NC or siRNA

ALOX15/siRNA NC was measured by scratch wound healing assays.

**P<0.01. Scale bar, 100 µm. (E) The viability of

HCAECs transfected with OE-ALOX15/OE-NC or siRNA ALOX15/siRNA NC

was measured by Cell Counting Kit-8 assays. **P<0.01

and ***P<0.001. ALOX15, 12/15-lipoxygenase; FGFR2,

fibroblast growth factor receptor 2; HCAECs, human primary coronary

artery endothelial cells; OE, overexpression; NC, negative control;

RT-qPCR, reverse transcription-quantitative PCR; siRNA, small

interfering RNA. |

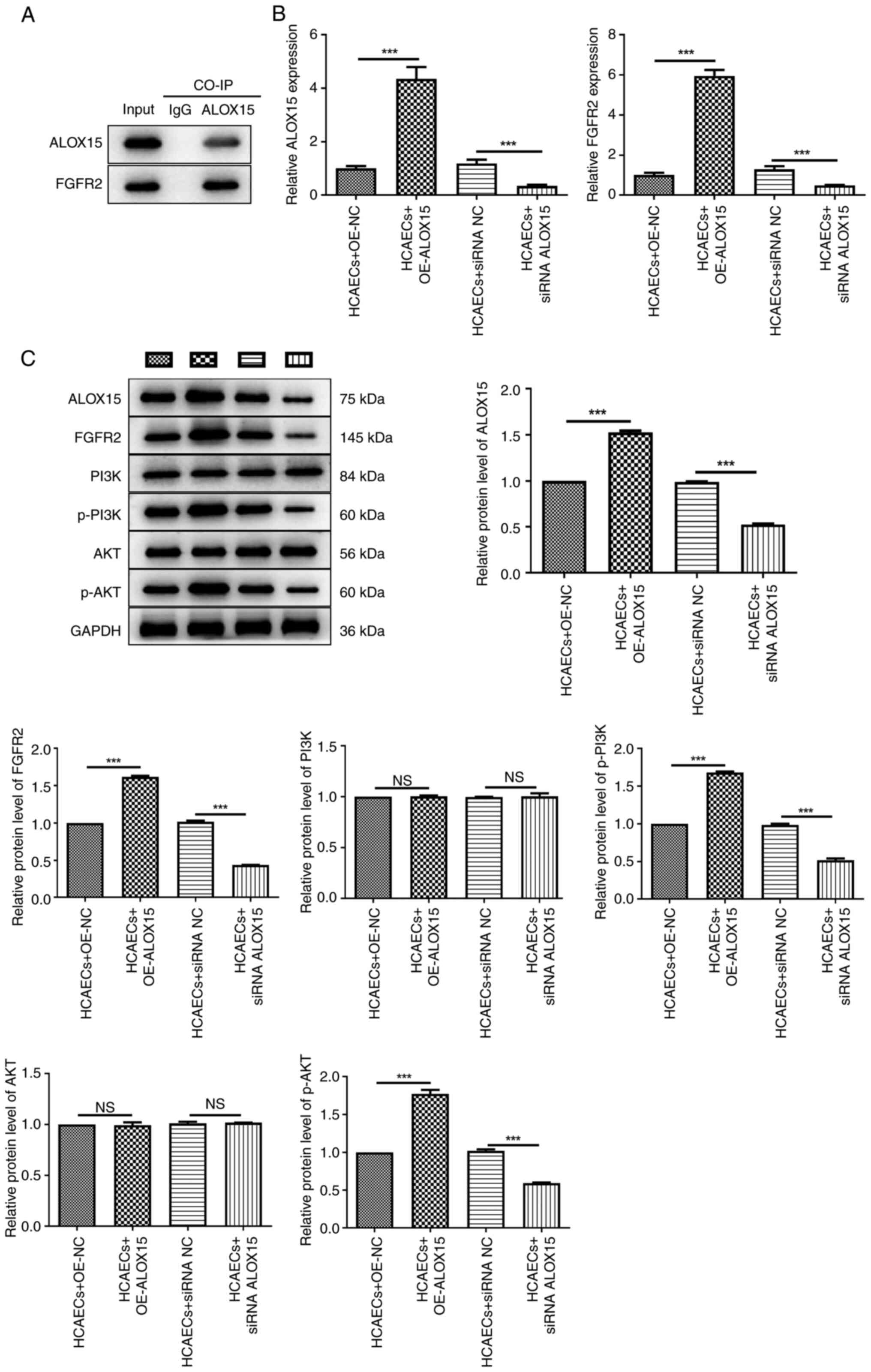

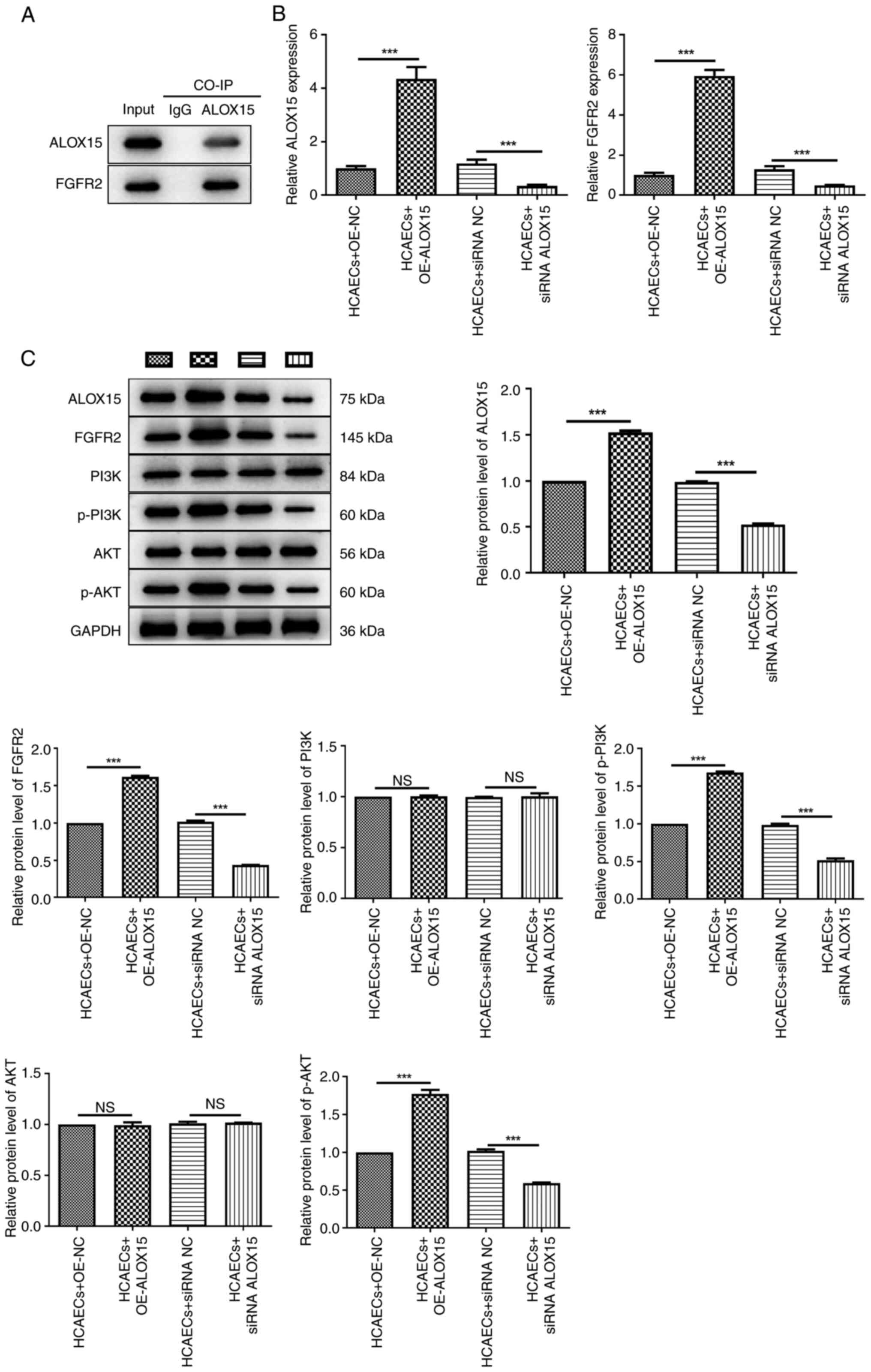

Effects of ALOX15 on the

FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in HCAECs

CO-IP analysis demonstrated that ALOX15 protein

could interact with FGFR2 in HCAECs (Fig. 3A). Furthermore, following

transfection, it was demonstrated that the mRNA expression of

ALOX15 and FGFR2 was significantly upregulated by the ectopic

expression of ALOX15, while silencing of ALOX15 resulted in a

significant decrease in their expression (Fig. 3B; P<0.001). Additionally, the

effects of ALOX15 overexpression or silencing on the levels of

FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway-related proteins were also

examined via western blotting. As illustrated in Fig. 3C, the results indicated that in

HCAECs, the protein levels of ALOX15, FGFR2, p-PI3K and p-AKT were

all markedly enhanced after OE-ALOX15 transfection, while they were

reduced after transfection with siRNA ALOX15 (P<0.001). Notably,

the protein levels of PI3K and AKT appeared unchanged following

treatment with OE-ALOX15 or siRNA ALOX15.

| Figure 3Effects of ALOX15 on the

FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway in HCAECs. (A)

Co-immunoprecipitation assays of ALOX15 and FGFR2 in HCAECs. (B)

The mRNA expression of ALOX15 and FGFR2 in HCAECs after

transfection with OE-ALOX15/OE-NC or siRNA ALOX15/siRNA NC was

detected by reverse transcription-quantitative PCR.

***P<0.001. (C) The protein levels of ALOX15, FGFR2,

PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT and p-AKT in HCAECs after transfection with

OE-ALOX15/OE-NC or siRNA ALOX15/siRNA NC were determined by western

blotting. ***P<0.001. ALOX15, 12/15-lipoxygenase;

FGFR2, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2; HCAECs, human primary

coronary artery endothelial cells; OE, overexpression; NC, negative

control; siRNA, small interfering RNA; p-, phosphorylated; NS, not

significant. |

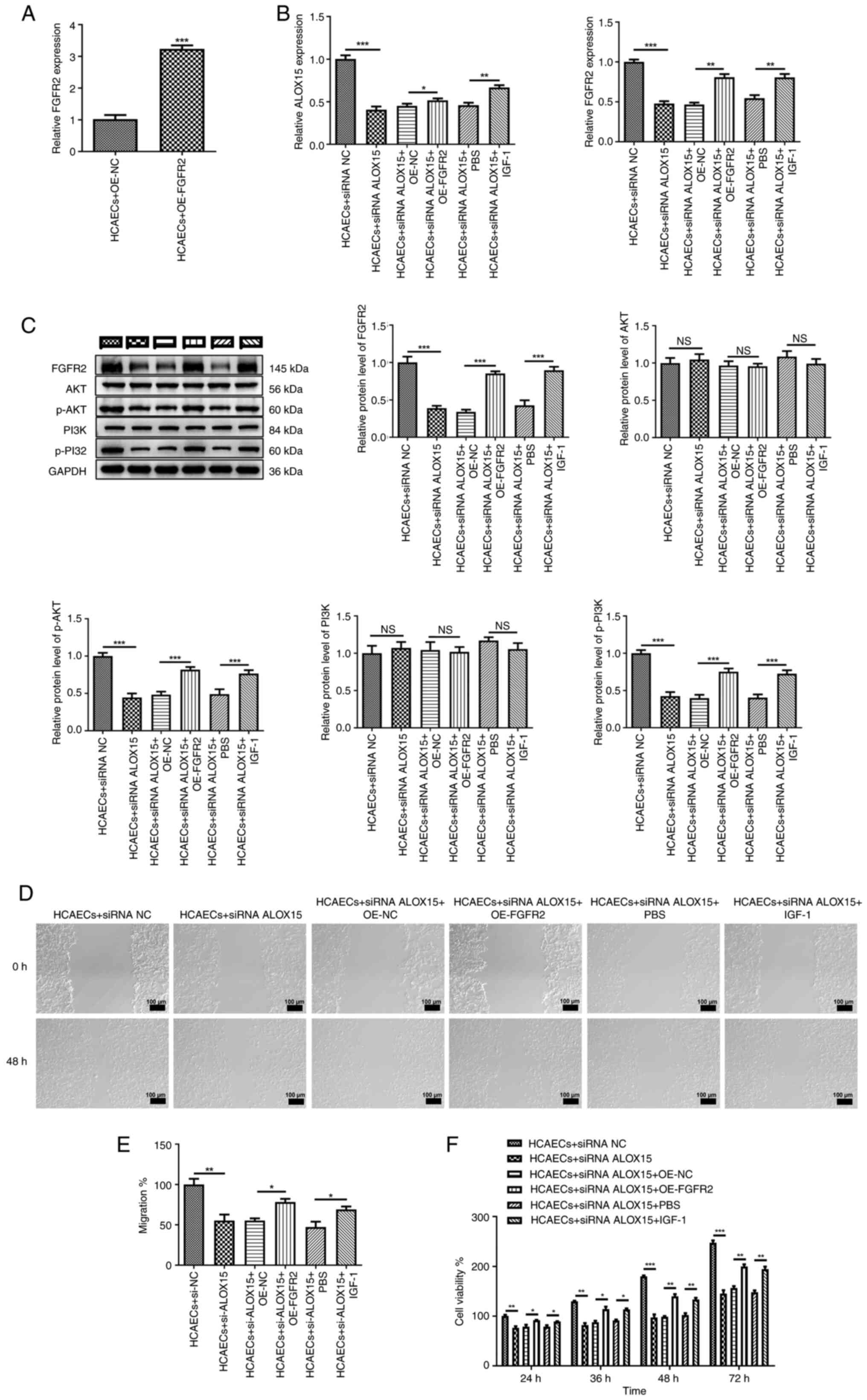

Silencing of ALOX15 mitigates ACS

progression in vitro through the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway

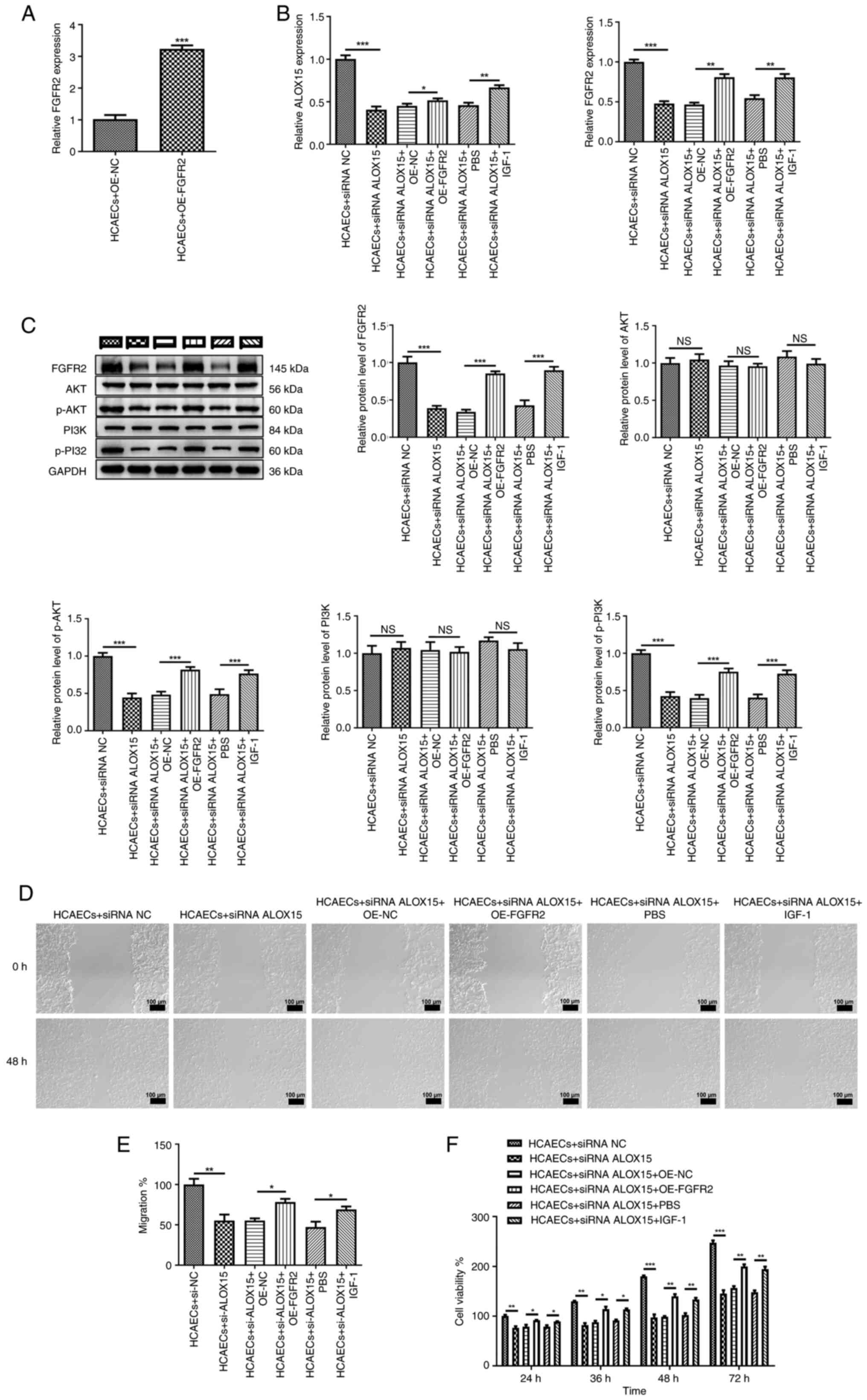

Firstly, FGFR2 was overexpressed in HCAECs to

examine the interaction of ALOX15 with FGFR2 (P<0.001), as

depicted in Fig. 4A. Meanwhile, 4

µl of PI3K/AKT pathway specific agonist IGF-1 was added to HCAECs

to further ascertain the mutual effect between ALOX15 and the

PI3K/AKT pathway. As illustrated in Fig. 4B, it was determined that both the

overexpression of FGFR2 and the addition of IGF-1 reversed the

suppressive effects of ALOX15 knockdown on the mRNA expression of

ALOX15 and FGFR2 (P<0.05). Similarly, the inhibition of the

PI3K/AKT pathway induced by ALOX15 knockdown was also partially

counteracted following the addition of OE-FGFR2 or IGF-1 (Fig. 4C; P<0.001). Additionally, it was

further demonstrated that both the overexpression of FGFR2 and the

addition of IGF-1 significantly mitigated the inhibitory effects of

ALOX15 knockdown on the migratory and proliferative abilities of

HCAECs (Fig. 4D-F; P<0.05).

| Figure 4Silencing of ALOX15 mitigates acute

coronary syndrome progression in vitro through the

FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. (A) The expression of FGFR2 in

HCAECs after transfection with OE-FGFR2 or OE-NC was detected by

RT-qPCR. (B) The mRNA expression of ALOX15 and FGFR2 in HCAECs

following different treatments was detected by RT-qPCR. (C) The

protein levels of FGFR2, PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT and p-AKT in HCAECs

following various treatments were determined by western blotting.

(D, E) The migration of HCAECs following different treatments was

assessed by scratch wound healing assays. Scale bar, 100 µm. (F)

The viability of HCAECs following various treatments was measured

by Cell Counting Kit-8 assays. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ALOX15,

12/15-lipoxygenase; FGFR2, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2;

HCAECs, human primary coronary artery endothelial cells; OE,

overexpression; NC, negative control; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; siRNA, small interfering RNA; p-,

phosphorylated; NS, not significant. |

Knockdown of ALOX15 reduces serum

lipid levels and improves myocardial injury in an ACS rat

model

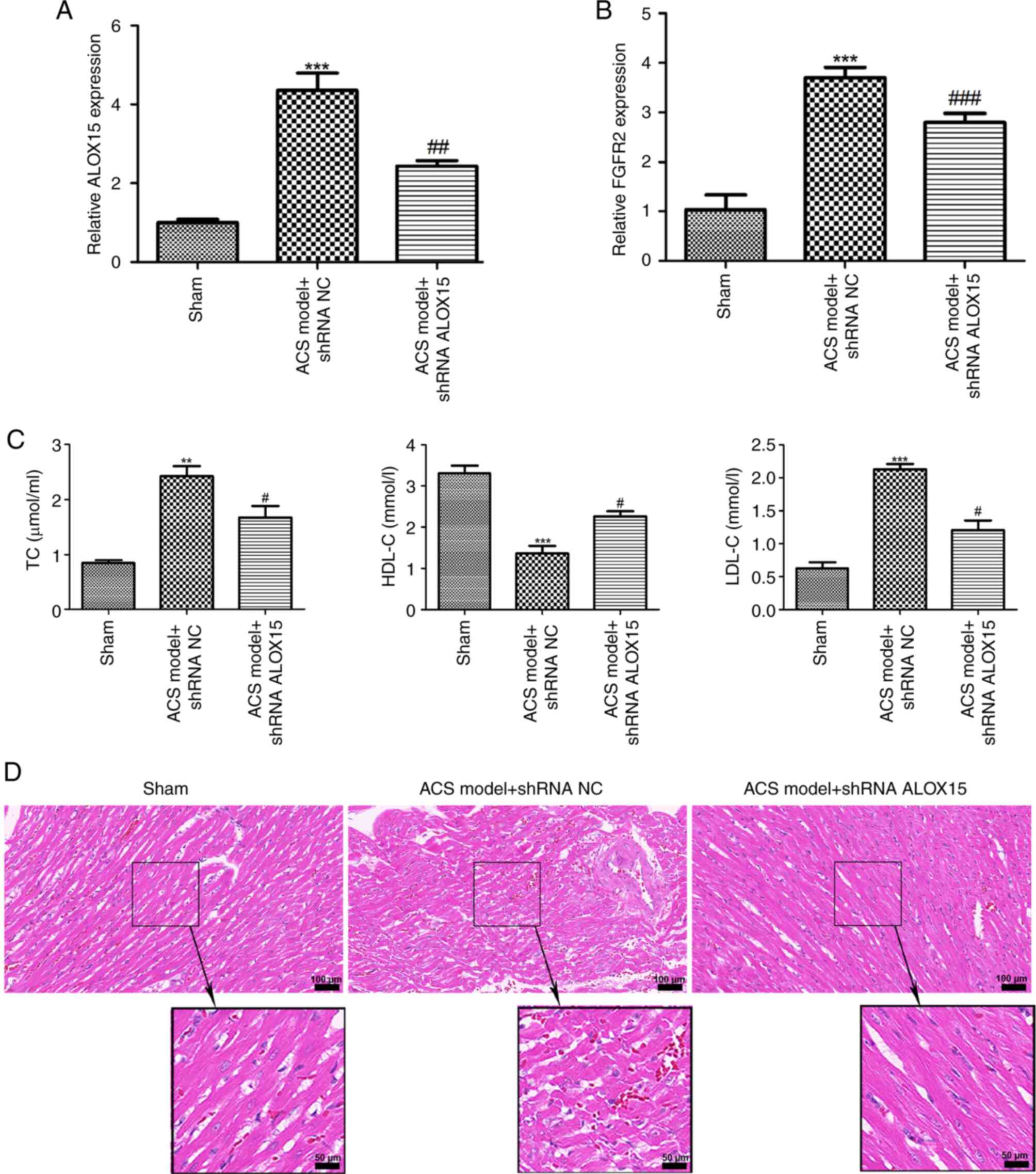

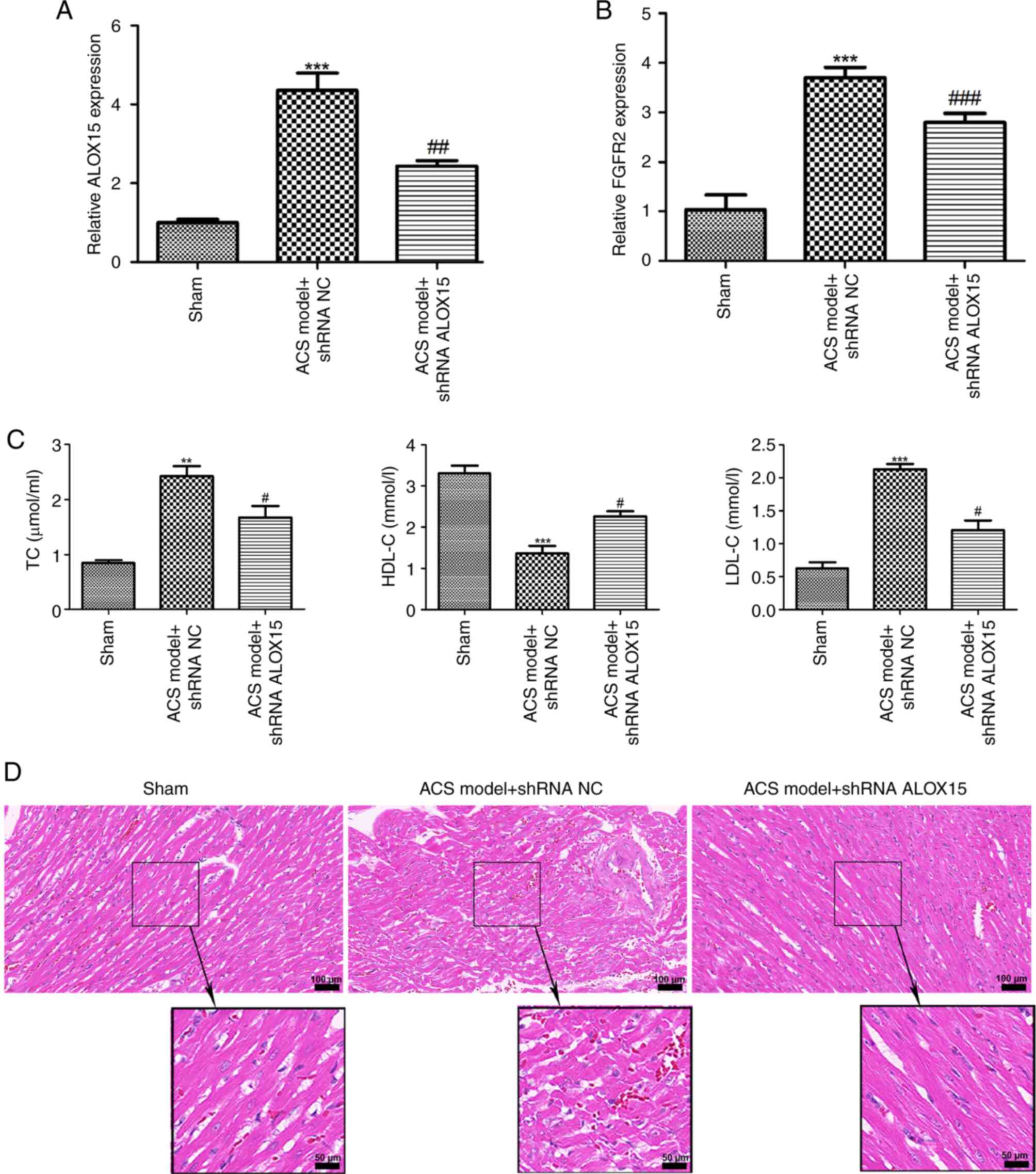

An ACS rat model was subsequently established. As

shown in Fig. 5A and B, a significant elevation in the mRNA

expression levels of ALOX15 and FGFR2 in rats subjected to ACS

(P<0.001) was observed, while injection of shRNA ALOX15 reversed

the increase of ALOX15 and FGFR2 levels induced by the ACS

challenge (P<0.01). Compared with the rats in the sham group,

the serum levels of TC and LDL-C were significantly increased in

the rats with ACS, while HDL-C levels were significantly decreased

(Fig. 5C; P<0.01). Notably,

intramyocardial injection of shRNA ALOX15 not only reduced the

levels of TC and LDL-C, but also increased the levels of HDL-C in

the rats with ACS (Fig. 5C;

P<0.05). Subsequently, the heart tissues from different groups

of rats were collected for pathological examination. As illustrated

in Fig. 5D, cardiomyocytes from the

sham group exhibited a normal morphology, with a neat arrangement

and no breaks. Conversely, cardiomyocytes from the rats with ACS

became swollen and thickened, with irregular morphology and

disordered arrangement. Following intramyocardial injection of

shRNA ALOX15, a marked improvement in both the morphology and

arrangement of cardiomyocytes was noted.

| Figure 5Knockdown of ALOX15 reduces serum

lipid levels and improves myocardial injury in an ACS rat model.

The expression of (A) ALOX15 and (B) FGFR2 in rats with ACS after

injection of shRNA ALOX15 or shRNA NC was detected by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. ***P<0.001 vs. sham;

##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 vs. ACS model +

shRNA NC. (C) The levels of TC, HDL-C and LDL-C in rats with ACS

after injection of shRNA ALOX15 or shRNA NC were determined using

biochemical tests. **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. sham; #P<0.05 vs. ACS

model + shRNA NC. (D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining for observing

the pathological condition of myocardial tissues in different

groups. Scale bars, 100 and 50 µm. ALOX15, 12/15-lipoxygenase; ACS,

acute coronary syndrome; FGFR2, fibroblast growth factor receptor

2; shRNA, short hairpin RNA; NC, negative control; TC, total

cholesterol; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol; LDL-C,

low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol. |

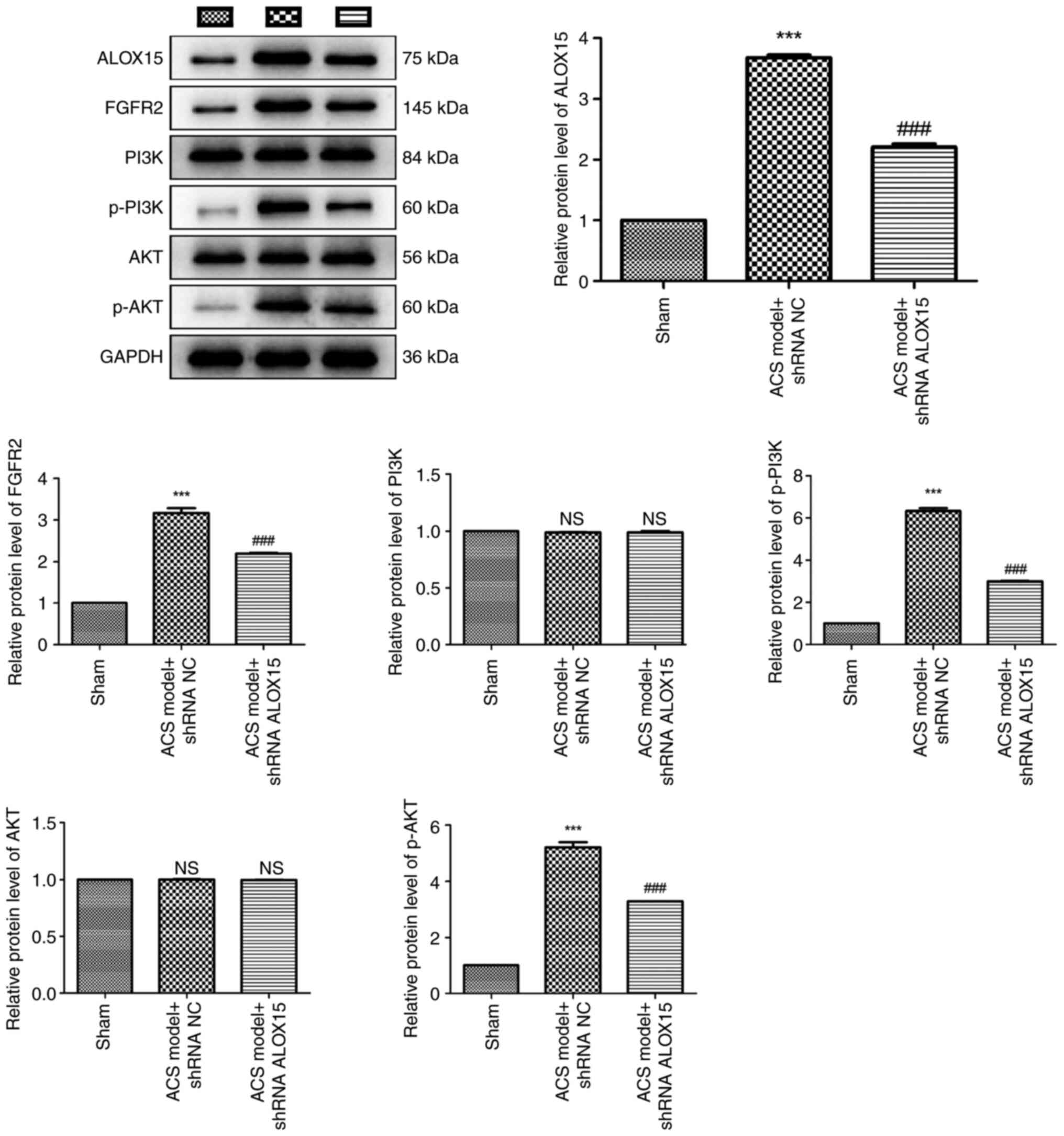

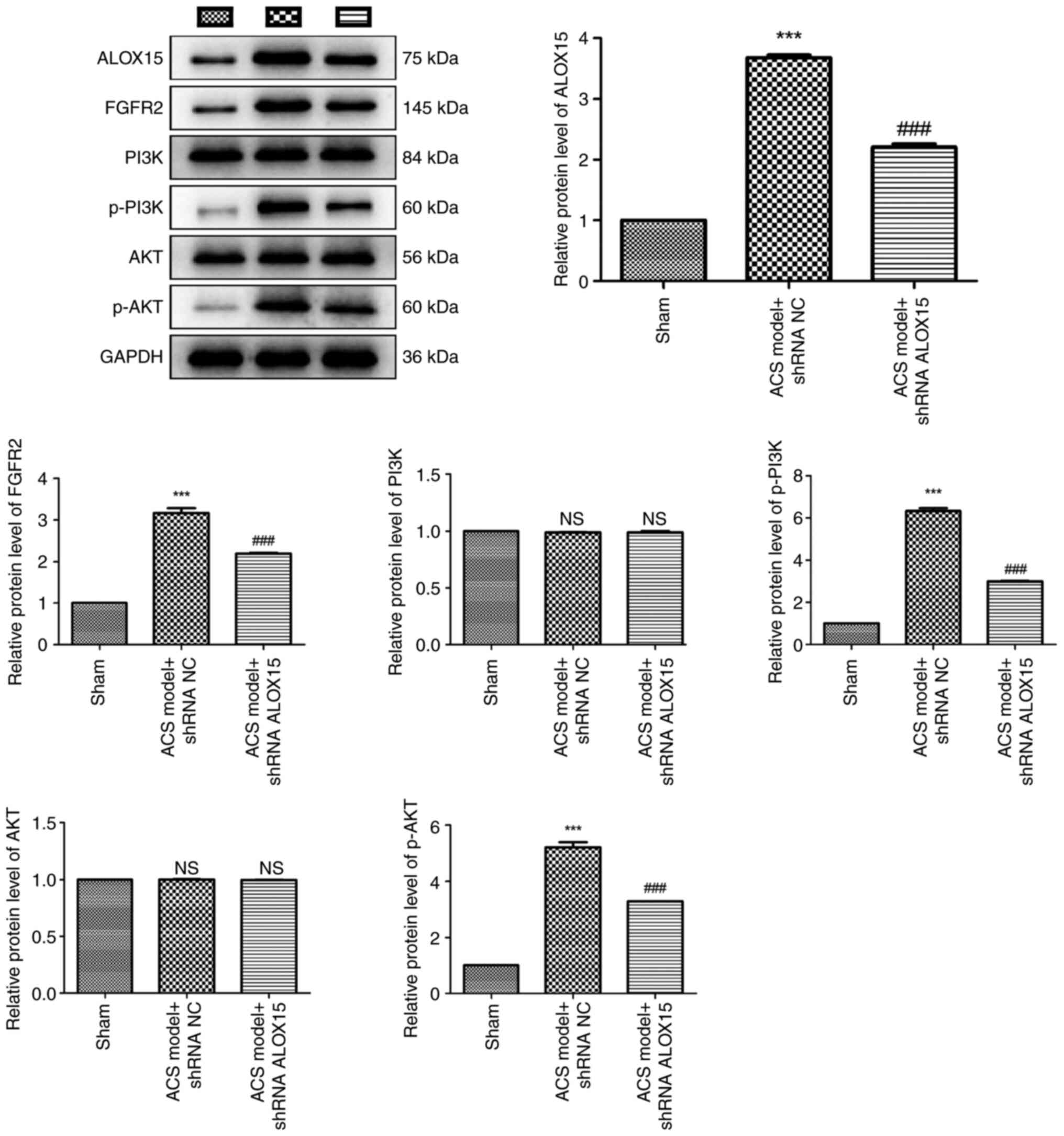

ALOX15 silencing suppresses the

activation of the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway

The levels of FGFR2/PI3K/AKT pathway-related

proteins were assessed in rats with ACS, as presented in Fig. 6. Western blot analysis revealed a

pronounced upregulation of ALOX15, FGFR2, p-PI3K and p-AKT proteins

in rats with ACS compared with these levels in the sham rats

(P<0.001). Notably, intramyocardial injection of shRNA ALOX15

effectively inhibited the increase of these proteins induced by the

ACS challenge (P<0.001). Furthermore, it was determined that

both ACS challenge and shRNA ALOX15 treatment did not significantly

affect the protein levels of PI3K and AKT.

| Figure 6ALOX15 silencing suppresses the

activation of the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. The protein

levels of ALOX15, FGFR2, PI3K, p-PI3K, AKT and p-AKT in rats with

ACS after injection of shRNA ALOX15 or shRNA NC were determined by

western blotting. ***P<0.001 vs. sham;

###P<0.001 vs. ACS model + shRNA NC. ALOX15,

12/15-lipoxygenase; FGFR2, fibroblast growth factor receptor 2; p-,

phosphorylated; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; shRNA, short hairpin

RNA; NC, negative control; NS, no significance. |

Discussion

Although the mortality of CAD among older patients

has recently decreased, the decrease in younger patients,

particularly in young women, has been less pronounced (35,36).

In spite of this, this condition continues to account for

approximately one-third of all deaths in individuals over the age

of 35 (37-39).

Additionally, the annual cost for each patient with ACS is

substantial and staggering, with hospitalization expenses alone

nearing $35,000 USD (40). In the

USA, the direct costs that the government spends on patients with

ACS every year amount to at least $310 billion (41). Consequently, ACS has become a heavy

burden not only for patients alone but also for the whole society.

In the present study, a novel molecular target for the potential

therapy of ACS was expounded, indicating that knockdown of ALOX15

may improve ACS by inhibiting the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT signaling

pathway.

The pathology of ACS encompasses multiple aspects,

with plaque rupture identified as one of the primary etiological

factors (3,4). The proliferation and migration of

endothelial cells following myocardial infarction are critical for

angiogenesis; however, abnormal endothelial cell behavior may

contribute to plaque instability and erosion, ultimately

precipitating the onset and progression of ACS (42-44).

In the present study, it was demonstrated that the proliferative

and migratory abilities of HCAECs were overtly weakened following

siRNA ALOX15 transfection, but enhanced by ALOX15 overexpression.

These findings indicated that the expression levels of ALOX15 may

be associated with ACS progression. Furthermore, endothelial

dysfunction is also characterized by elevated levels of TC and

LDL-C (45,46). Since it was confirmed that silencing

of ALOX15 inhibited the aberrant proliferation and migration of

HCAECs, it was further hypothesized that ALOX15 silencing may also

play a significant role in regulating blood lipid levels. As

anticipated, the findings in the present study confirmed that

injection of shRNA ALOX15 markedly reduced the levels of TC and

LDL-C, and elevated the levels of HDL-C in rats with ACS. By

determining blood lipid levels in patients with ACS, it can be

assessed whether ALOX15 is involved in ACS progression, thereby

enabling more ACS targeted clinical treatments. Evidence has

indicated that high levels of ALOX15 are correlated with

endothelial cell barrier dysfunction in rats with a high-fat diet

(47). The results of the present

study indicated that knockdown of ALOX15 can relieve endothelial

dysfunction, to some extent. In addition, silencing of ALOX15 also

alleviated the cardiac injury of rats with ACS. Therefore, it is

proposed that ALOX15 may serve as a potential therapeutic target

for ACS in clinical settings. Furthermore, the silencing of ALOX15

appears to be beneficial in mitigating the progression of ACS.

It is well-known that FGFR2 is strongly associated

with endothelial dysfunction, including aberrant cell proliferation

and migration (26,28). Given the significant effects of

ALOX15 on the viability and migration of HCAECs, it was

hypothesized that ALOX15 may interact with FGFR2 in ACS progression

in vitro. In the present study, CO-IP confirmed that ALOX15

protein interacts with FGFR2 in HCAECs. Furthermore, it was

demonstrated that ALOX15 overexpression increases both the mRNA

expression and protein levels of FGFR2, while ALOX15 silencing

leads to their reduction. These results indicated that ALOX15 may

synergistically interact with FGFR2 to affect the development of

ACS. Notably, FGFR2 has been widely reported as an activator of the

PI3K/AKT pathway in various human diseases (30,31).

Additionally, the PI3K/AKT pathway has been demonstrated to be

involved in regulating the growth and function of cardiomyocytes,

thrombogenesis and vascular homeostasis (48). Previous studies have reported that

PI3K/AKT is a classical signaling pathway involved in numerous

cardiovascular disorders such as myocardial ischemia/reperfusion

injury, cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial infarction and heart

failure (18-21).

It was therefore further hypothesized that PI3K/AKT can be

modulated by ALOX15 in ACS pathobiology. As anticipated,

overexpression of ALOX15 markedly activated the PI3K/AKT pathway.

Conversely, silencing of ALOX15 inhibited the PI3K/AKT pathway both

in HCAECs and rats with ACS. Notably, both the overexpression of

FGFR2 and the addition with IGF-1 significantly mitigated the

inhibitory effects of ALOX15 knockdown on the migratory and

proliferative abilities of HCAECs. It was therefore concluded that

silencing of ALOX15 may suppress the progression of ACS by

inhibiting the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT pathway.

Some limitations of the present study should be

mentioned. First, in addition to the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT pathway, other

potential pathways or mechanisms regulated by ALOX15 in the

progression of ACS may exist and should be further investigated in

depth. Second, with the exception of the rat model that was

established in the present study, similar models have also been

extensively used in other animal species, including rabbits

(49), mice (50), and pigs (51). In future studies, the findings of

the present study will be validated in other animal models. Third,

this study was conducted in a specific population in Wenzhou, which

may limit the generalizability of the results. In future studies,

the research will be expanded to include diverse populations across

China. Fourth, elevated levels of ALOX15 may also be influenced by

unrelated inflammatory processes. Future studies will better

control for such potential confounders.

Additionally, several potential challenges or

limitations may arise when translating the current findings from

preclinical models to clinical settings. For example, a)

physiological differences: i) Targeted drugs can be effectively

metabolized in animals, but may be metabolized slowly or produce

different metabolites in humans, resulting in differences in

efficacy and toxicity; ii) animal models are difficult to fully

simulate the complexity of human diseases. b) Drug response

differences: i) Targeted drugs that have shown promising efficacy

in preclinical models may have reduced efficacy in clinical

settings due to various factors; ii) animals often differ in their

tolerance and response to drug toxicity compared with humans. Some

drugs that may not show significant toxicity in animal experiments,

may cause serious adverse reactions in humans. c) External

environmental differences: i) Preclinical animals are typically

housed in controlled environments with consistent temperature,

humidity, light cycles, and diets, however, human lifestyles and

environments are highly variable, which can affect treatment

outcomes; ii) preclinical models cannot simulate the psychological

and social factors of human patients. The psychological state of

human patients, such as stress, anxiety, depression, and other

emotions, can have an impact on the development and treatment

response of the disease.

In summary, the present study provides preliminary

insights into the underlying mechanism of ALOX15 in the

pathogenesis of ACS. The findings, for the first time, to the best

of the authors' knowledge indicate that silencing of ALOX15 may

mitigate ACS progression by inhibiting the FGFR2/PI3K/AKT pathway.

This research offers a foundational basis and perspectives on

potential clinical therapeutic strategies for ACS. However, further

investigations to validate these findings in clinical settings are

urgently warranted.

Acknowledgements

Not available.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Zhejiang Provincial

Hygiene and Health Plan in 2021 (grant no. 2021RC126).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

LY made substantial contributions to the conception

and design of the study. HC, NZ, SH, FG, SH and FY made substantial

contributions to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of

the data. HC drafted the manuscript. NZ, SH, FG, SH and FY revised

the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All

authors confirm the authenticity of all the raw data, as well as

read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree to

be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that

questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the

work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The patients/participants provided their written

informed consent to participate in the present study. The study was

conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of

Helsinki and approved (approval no. 2020-351) by the Ethics

Committee of The Third Affiliated Hospital of Shanghai University

(Wenzhou People's Hospital; Wenzhou, China). Animal experiments

were conducted in compliance with the Guidelines for the Use of

Laboratory Animals and approved (approval no. xmsq2023-1367) by the

Ethics Committee of Wenzhou Medical University (Wenzhou,

China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Dong CH, Wang ZM and Chen SY: Neutrophil

to lymphocyte ratio predict mortality and major adverse cardiac

events in acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 52:131–136. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Bob-Manuel T, Ifedili I, Reed G, Ibebuogu

UN and Khouzam RN: Non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: A

comprehensive review. Curr Probl Cardiol. 42:266–305.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy

O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, Dendale P, Dorobantu M, Edvardsen T,

Folliguet T, et al: 2020 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute

coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent

ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 42:1289–1367. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Libby P and Pasterkamp G: Requiem for the

‘vulnerable plaque’. Eur Heart J. 36:2984–2987. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Makki N, Brennan TM and Girotra S: Acute

coronary syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 30:186–200.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Kaul P, Ezekowitz JA, Armstrong PW, Leung

BK, Savu A, Welsh RC, Quan H, Knudtson ML and McAlister FA:

Incidence of heart failure and mortality after acute coronary

syndromes. Am Heart J. 165:379–385 e2. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey

DE Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM,

Franklin BA, et al: 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of

ST-elevation myocardial infarction: Executive summary: A report of

the American college of cardiology foundation/American heart

association task force on practice guidelines: Developed in

collaboration with the American college of emergency physicians and

society for cardiovascular angiography and interventions. Catheter

Cardiovasc Interv. 82:E1–E27. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Oliw EH: Diversity of the manganese

lipoxygenase gene family-A mini-review. Fungal Genet Biol.

163(103746)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hiltunen T, Luoma J, Nikkari T and

Yla-Herttuala S: Induction of 15-lipoxygenase mRNA and protein in

early atherosclerotic lesions. Circulation. 92:3297–3303.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Kuhn H, Heydeck D, Hugou I and Gniwotta C:

In vivo action of 15-lipoxygenase in early stages of human

atherogenesis. J Clin Invest. 99:888–893. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhang K, Wang YY, Liu QJ, Wang H, Liu FF,

Ma ZY, Gong YQ and Li L: Two single nucleotide polymorphisms in

ALOX15 are associated with risk of coronary artery disease in a

Chinese Han population. Heart Vessels. 25:368–373. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ma XH, Liu JH, Liu CY, Sun WY, Duan WJ,

Wang G, Kurihara H, He RR, Li YF, Chen Y and Shang H:

ALOX15-launched PUFA-phospholipids peroxidation increases the

susceptibility of ferroptosis in ischemia-induced myocardial

damage. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7(288)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Cai W, Liu L, Shi X, Liu Y, Wang J, Fang

X, Chen Z, Ai D, Zhu Y and Zhang X: Alox15/15-HpETE aggravates

myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting cardiomyocyte

ferroptosis. Circulation. 147:1444–1460. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Kayama Y, Minamino T, Toko H, Sakamoto M,

Shimizu I, Takahashi H, Okada S, Tateno K, Moriya J, Yokoyama M, et

al: Cardiac 12/15 lipoxygenase-induced inflammation is involved in

heart failure. J Exp Med. 206:1565–1574. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Silbiger VN, Luchessi AD, Hirata RD,

Lima-Neto LG, Cavichioli D, Carracedo A, Brión M, Dopazo J,

García-García F, dos Santos ES, et al: Novel genes detected by

transcriptional profiling from whole-blood cells in patients with

early onset of acute coronary syndrome. Clin Chim Acta.

421:184–190. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Chen H, Huang S, Guan F, Han S, Ye F, Li X

and You L: Targeting circulating lncRNA ENST00000538705.1 relieves

acute coronary syndrome via modulating ALOX15. Dis Markers.

2022(8208471)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Feng J, Yang F, Wu H, Xing C, Xue H, Zhang

L, Zhang C, Hu G and Cao H: Selenium protects against

cadmium-induced cardiac injury by attenuating programmed cell death

via PI3K/AKT/PTEN signaling. Environ Toxicol. 37:1185–1197.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Yu D, Xiong J, Gao Y, Li J, Zhu D, Shen X,

Sun L and Wang X: Resveratrol activates PI3K/AKT to reduce

myocardial cell apoptosis and mitochondrial oxidative damage caused

by myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Acta Histochem.

123(151739)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Cheng Y, Shen A, Wu X, Shen Z, Chen X, Li

J, Liu L, Lin X, Wu M, Chen Y, et al: Qingda granule attenuates

angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy and apoptosis and

modulates the PI3K/AKT pathway. Biomed Pharmacother.

133(111022)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Han X, Zhang G, Chen G, Wu Y, Xu T, Xu H,

Liu B and Zhou Y: Buyang Huanwu Decoction promotes angiogenesis in

myocardial infarction through suppression of PTEN and activation of

the PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol.

287(114929)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Chang H, Li C, Wang Q, Lu L, Zhang Q,

Zhang Y, Zhang N, Wang Y and Wang W: QSKL protects against

myocardial apoptosis on heart failure via PI3K/Akt-p53 signaling

pathway. Sci Rep. 7(16986)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Ruan R, Li L, Li X, Huang C, Zhang Z,

Zhong H, Zeng S, Shi Q, Xia Y, Zeng Q, et al: Unleashing the

potential of combining FGFR inhibitor and immune checkpoint

blockade for FGF/FGFR signaling in tumor microenvironment. Mol

Cancer. 22(60)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Takahashi M, Umehara Y, Yue H,

Trujillo-Paez JV, Peng G, Nguyen HLT, Ikutama R, Okumura K, Ogawa

H, Ikeda S and Niyonsaba F: The antimicrobial peptide human

β-defensin-3 accelerates wound healing by promoting angiogenesis,

cell migration, and proliferation through the FGFR/JAK2/STAT3

signaling pathway. Front Immunol. 12(712781)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Weaver A and Bossaer JB: Fibroblast growth

factor receptor (FGFR) inhibitors: A review of a novel therapeutic

class. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 27:702–710. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Farooq M, Khan AW, Kim MS and Choi S: The

role of fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling in tissue repair

and regeneration. Cells. 10(3242)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Mieczkowski K, Popeda M, Lesniak D, Sadej

R and Kitowska K: FGFR2 Controls growth, adhesion and migration of

nontumorigenic human mammary epithelial cells by regulation of

integrin β 1 degradation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia.

28(9)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yoshii T, Matsuzawa Y, Kato S, Sato R,

Hanajima Y, Kikuchi S, Nakahashi H, Konishi M, Akiyama E,

Minamimoto Y, et al: Endothelial dysfunction predicts bleeding and

cardiovascular death in acute coronary syndrome. Int J Cardiol.

376:11–17. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Jiao K, Su P and Li Y: FGFR2 modulates the

Akt/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway to improve angiotensin II-induced

hypertension-related endothelial dysfunction. Clin Exp Hypertens.

45(2208777)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Huang C, Wang R, Lu J, He Y, Wu Y, Ma W,

Xu J, Wu Z, Feng Z and Wu M: MicroRNA-338-3p as a therapeutic

target in cardiac fibrosis through FGFR2 suppression. J Clin Lab

Anal. 36(e24584)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Riccetti MR, Green J, Taylor TJ and Perl

AT: Prenatal FGFR2 signaling via PI3K/AKT specifies the

PDGFRA+ myofibroblast. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol.

70:63–77. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Yang J, Xin C, Yin G and Li J:

Taraxasterol suppresses the proliferation and tumor growth of

androgen-independent prostate cancer cells through the

FGFR2-PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Sci Rep. 13(13072)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Wu S, Sun H and Sun B: MicroRNA-145 is

involved in endothelial cell dysfunction and acts as a promising

biomarker of acute coronary syndrome. Eur J Med Res.

25(2)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Li J, Gong L, Zhang R, Li S, Yu H, Liu Y,

Xue Y, Huang D, Xu N, Wang Y, et al: Fibroblast growth factor 21

inhibited inflammation and fibrosis after myocardial infarction via

EGR1. Eur J Pharmacol. 910(174470)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Roth GA, Huffman MD, Moran AE, Feigin V,

Mensah GA, Naghavi M and Murray CJ: Global and regional patterns in

cardiovascular mortality from 1990 to 2013. Circulation.

132:1667–1678. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gupta A, Wang Y, Spertus JA, Geda M,

Lorenze N, Nkonde-Price C, D'Onofrio G, Lichtman JH and Krumholz

HM: Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and

differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol.

64:337–345. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Rosamond W, Flegal K, Furie K, Go A,

Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern SM, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, et

al: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2008 update: A report from

the American heart association statistics committee and stroke

statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 117:e25–e146. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Nichols M, Townsend N, Scarborough P and

Rayner M: Cardiovascular disease in Europe 2014: Epidemiological

update. Eur Heart J. 35(2929)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Ferreira-Gonzalez I: The epidemiology of

coronary heart disease. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 67:139–144.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Menzin J, Wygant G, Hauch O, Jackel J and

Friedman M: One-year costs of ischemic heart disease among patients

with acute coronary syndromes: Findings from a multi-employer

claims database. Curr Med Res Opin. 24:461–468. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin

EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, et al:

Executive summary: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2013 update:

A report from the American heart association. Circulation.

127:143–152. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Bonetti PO, Lerman LO and Lerman A:

Endothelial dysfunction: A marker of atherosclerotic risk.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 23:168–175. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Kinlay S and Ganz P: Role of endothelial

dysfunction in coronary artery disease and implications for

therapy. Am J Cardiol. 80:11I–16I. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Zhu F, Wang Q, Guo C, Wang X, Cao X, Shi

Y, Gao F, Ma C and Zhang L: IL-17 induces apoptosis of vascular

endothelial cells: A potential mechanism for human acute coronary

syndrome. Clin Immunol. 141:152–160. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Stein RA: Endothelial dysfunction,

erectile dysfunction, and coronary heart disease: The

pathophysiologic and clinical linkage. Rev Urol. 5 (Suppl

7):S21–S27. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

46

|

Ling L, Zhao SP, Gao M, Zhou QC, Li YL and

Xia B: Vitamin C preserves endothelial function in patients with

coronary heart disease after a high-fat meal. Clin Cardiol.

25:219–224. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Singh NK and Rao GN: Emerging role of

12/15-Lipoxygenase (ALOX15) in human pathologies. Prog Lipid Res.

73:28–45. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Eisenreich A and Rauch U: PI3K inhibitors

in cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Ther. 29:29–36.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Ozkaynak B, Sahin I, Ozenc E, Subaşı C,

Oran DS, Totoz T, Tetikkurt ÜS, Mert B, Polat A, Okuyan E and

Karaöz E: Mesenchymal stem cells derived from epicardial adipose

tissue reverse cardiac remodeling in a rabbit model of myocardial

infarction. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 25:4372–4384.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Chen L, Li S, Zhu J, You A, Huang X, Yi X

and Xue M: Mangiferin prevents myocardial infarction-induced

apoptosis and heart failure in mice by activating the Sirt1/FoxO3a

pathway. J Cell Mol Med. 25:2944–2955. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Nagy RN, Makkos A, Baranyai T, Giricz Z,

Szabó M, Kravcsenko-Kiss B, Bereczki Z, Ágg B, Puskás LG, Faragó N,

et al: Cardioprotective microRNAs (protectomiRs) in a pig model of

acute myocardial infarction and cardioprotection by ischaemic

conditioning: MiR-450a. Br J Pharmacol. 182:396–416.

2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|