Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are responsible for

the majority of illnesses and deaths worldwide, accounting for 49%

of female and 40% of male deaths (1). Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), a type

of CVD, encompasses acute ST-segment elevation myocardial

infarction (STEMI), acute non-STEMI ST-segment elevation myocardial

infarction (NSTEMI), and unstable angina pectoris (UA). These

conditions arise from the rupture or invasion of plaques in

coronary arteries affected by atherosclerosis (2,3). ACS

often serves as a significant risk factor for acute heart failure

(4). Despite advancements in

treatment options, such as coronary revascularization,

antithrombotic agents, and anticoagulants, approximately one-fifth

of patients with ACS experience recurrent adverse cardiovascular

events within 3 years following the initial diagnosis (5,6).

Therefore, a deeper understanding of the molecular mechanisms

underlying ACS is crucial for improving patient outcomes.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are a type of ncRNA

consisting of over 200 nucleotides that cannot encode proteins.

They have been scientifically proven to influence various

biological processes, including epigenetics, transcription, and

post-transcriptional regulation in living organisms (7). Several studies have highlighted the

involvement of numerous lncRNAs in ACS diagnosis and development of

ACS. Chen et al (8)

conducted a microarray analysis of serum samples obtained from

individuals with ACS and identified 353 dysregulated lncRNAs.

Subsequent investigations revealed that the modulation of

arachidonate 15-lipoxygenase expression by a specific lncRNA

ENST00000538705.1 could expedite the progression of ACS (8). Additionally, Barbalata et al

(9) found an association between

two distinct lncRNAs (LIPCAR and MALAT1) and hyperglycemia in

patients with UA, identifying them as reliable prognostic

indicators of adverse outcomes in patients with STEMI (9). Another study revealed a negative

association between increased levels of lncRNA PELATON and ACS

prognosis (10). Notably,

transcription factor AP-2α (TFAP2A)-AS1 is a relatively

understudied lncRNA located on chromosome 6q24.3. Current research

on lncRNA TFAP2A-AS1 has primarily focused on its impact on the

pathogenesis and progression of various human cancers. For

instance, elevated expression of TFAP2A-AS1 has been associated

with improved prognosis in gastric cancer (GC) and breast cancer

(BC), whereas overexpression of TFAP2A-AS1 in GC and BC cells

suppressed cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (11,12).

Conversely, TFAP2A-AS1 was shown to be highly expressed in

non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and oral squamous cell carcinoma

(OSCC); however, its absence inhibited tumor development (13,14).

Nevertheless, the precise biological role and mechanism of action

of TFAP2A-AS1 in ACS remain poorly understood.

The aim of the present study was to explore the

mechanism of action of TFAP2A-AS1 in the pathogenesis of ACS and to

identify potential molecular targets for therapeutic intervention

in patients with ACS.

Materials and methods

Patients and diagnostic criteria

The present research adhered to the principles

outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval

(approval ID: KY-2021053) from the Ethics Committee of Wenzhou

People's Hospital (Wenzhou, China). From September 2021 to October

2022, a total of 5 patients diagnosed with ACS were admitted to

Wenzhou People's Hospital. Concurrently, 5 healthy individuals of

comparable age were recruited to serve as controls. The diagnostic

criteria for ACS included confirmed stenosis (at least one major

coronary artery ≥50%) through coronary angiography, and/or meeting

the acute myocardial infarction criteria (typical clinical

symptoms, elevated cardiac enzyme levels, and representative

electrocardiography findings). The inclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Meeting the diagnostic criteria; ii) age between 35-75

years; and iii) providing informed consent. The exclusion criteria

were as follows: i) The presence of comorbid conditions such as

cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, severe arrhythmia, heart

failure or other concurrent ailments; ii) challenges in data

collection due to religious or language barriers; and iii) being

pregnant or breastfeeding. Venous blood samples (5 ml) were

collected from both patients with ACS and healthy controls. The

samples were then centrifuged at 3,000 x g at a temperature of 4˚C

for a duration of 5 min. Following centrifugation, the samples were

stored at -80˚C for subsequent experiments. The clinicopathological

factors of healthy controls and patients with ACS are summarized in

Table I.

| Table IClinicopathological factors of

healthy controls and patients with ACS. |

Table I

Clinicopathological factors of

healthy controls and patients with ACS.

|

Characteristics | Healthy controls

(n=5) | Patients with ACS

(n=5) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 64.00±3.03 | 62.40±10.07 | 0.7425 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 24.66±4.21 | 25.12±3.28 | 0.8520 |

| Sex

(male/female) | 2/3 | 2/3 | N/A |

| Smoking,

(N/total) | 2/5 | 2/5 | N/A |

| Drinking,

(N/total) | 2/5 | 2/5 | N/A |

| Hypertension,

(N/total) | 3/5 | 3/5 | N/A |

| Cardiac troponin I,

µg/l | 0.014±0.0001 | 4.57±0.21 | <0.0001 |

Reagents

Human primary coronary artery endothelial cells

(HCAECs), mouse coronary artery endothelial cells (MCAECs) and 293

cells were sourced from Pricella Biotechnology Co., Ltd. The

utilization of primary cells was approved (approval ID:

KZ-20240521) by the Ethics Committee of Wenzhou People's Hospital.

Endothelial basal medium 2 (EBM-2) and fetal bovine serum (FBS)

were obtained from Lonza Group, Ltd. CCK-8 solution was provided by

Abbkine Scientific Co., Ltd. BD Biosciences provided the Matrigel.

Genomeditech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Synthesized TFAP2A-AS1 small

interfering (si)RNA1/2/3, TFAP2A siRNA1/2/3, lentiviral vectors

integrated with TFAP2A-AS1 shorth hairpin (sh)RNA/TFAP2A shRNA, and

the corresponding negative controls (NC siRNA or NC shRNA). Vazyme

Biotech Co., Ltd. supplied an Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection

kit. Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology provided the hematoxylin

and eosin (H&E) staining kit, the RIPA lysis buffer, the

enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit and the bicinchonic acid (BCA)

kit. Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. provided the Lipofectamine

RNAiMAX transfection agent and Pierce Magnetic RNA-Protein

Pull-Down kit (cat. no. 20164). Beijing Solarbio Science &

Technology Co., Ltd. supplied the Total cholesterol (TC) Content

Assay Kit (cat. no. BC1980). Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering

Institute provided the high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C)

assay kit (cat. no. A112-1-1) and low-density

lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C) assay kit (cat. no. A113-1-1).

Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd. supplied the MiniBEST Universal RNA

Extraction kit (cat. no. 9767). Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc. supplied the PrimeScript RT reagent and SYBR Green

Premix for the experiment. Primary antibodies TFAP2A (cat. no.

13019-3-AP), IgG control (cat. no. 30000-0-AP) and GAPDH (cat. no.

60004-1-Ig) were purchased from Proteintech Group, Inc., along with

horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (cat.

no. SA00001-2). The Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein

Immunoprecipitation kit (cat. no. 17-700) was obtained from

MilliporeSigma.

Cell culture

The HCAECs were cultured in EBM-2 supplemented with

15% FBS, under conditions of 5% CO2 and a temperature of

37˚C. For functional experiments, cells in the phase of logarithmic

growth were collected.

Cell transfection

Cell transfection was performed in strict accordance

with the protocols of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent.

In brief, HCAECs were individually transfected with 50 nM of

TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA1/2/3 (TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA1 forward,

5'-UGCUAAUGAGGCGAUUAGGCU-3' and reverse,

5'-CCUAAUCGCCUCAUUAGCAUA-3'; TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA2 forward,

5'-AUUUCUAAUAAAAUUGCACGG-3' and reverse,

5'-GUGCAAUUUUAUUAGAAAUCA-3'; TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA3 forward,

5'-UGUUUUUAGGCUCAACUUCAG-3' and reverse,

5'-GAAGUUGAGCCUAAAAACAGA-3'); TFAP2A siRNA1/2/3 (TFAP2A siRNA1

forward, 5'-AUUUAAUCCUAUUUUGUCCAG-3' and reverse,

5'-GGACAAAAUAGGAUUAAAUCU-3'; TFAP2A siRNA2 forward,

5'-UUGCAUAUCUGUUUUGUAGCC-3' and reverse,

5'-CUACAAAACAGAUAUGCAAAG-3'; TFAP2A siRNA3 forward,

5'-UGCUUUUGGCGUUGUUGUCCG-3' and reverse,

5'-GACAACAACGCCAAAAGCAGU-3'); and NC siRNA forward,

5'-GAAAUGUUUAGGGCCAGUGCU-3' and reverse,

5'-AGCACUGGCCCUAAACAUUUC-3' for 48 h at 37˚C using Lipofectamine

RNAiMAX transfection reagent. Following transfection, cells were

collected for subsequent experiments.

Flow cytometric analysis

The apoptosis of HCAECs was assessed by employing a

commercially available Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection kit.

Briefly, HCAECs (2x105) were suspended in 500 µl of

binding buffer, and subsequently stained with PI and Annexin V-FITC

(both 5 µl) at 4˚C for 15 min in the absence of light. Following

this step, cell apoptosis was evaluated using a FACScan flow

cytometer (version 3.0; Becton, Dickinson and Company) and analyzed

using BD CellQuest Pro software (version 5.2.1; Becton, Dickinson

and Company). Cells were classified as viable cells (lower left

quadrant), necrotic cells (upper left quadrant), early apoptotic

cells (lower right quadrant) and late apoptotic cells (upper right

quadrant). The apoptosis rate was estimated by calculating the

total percentages of both early and late apoptotic cells.

CCK-8 assay

HCAECs were cultured in 96-well plates at a density

of 3,500 cells per well and incubated for various time intervals

(24, 36, 48, and 72 h). Subsequently, each well was supplemented

with 10 µl of CCK-8 solution and further incubated for 2 h at 37˚C.

Following the addition of 10 µl of stop solution to every well,

cell viability was assessed using a microplate reader (DR-3518G;

Wuxi Hiwell Diatek Instruments Co., Ltd.), which measured the

absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm.

Transwell assay

The upper chamber of Transwell insert was pre-coated

with 50 µl of Matrigel at 37˚C for 30 min, which had been diluted

5-fold in serum-free EBM-2. HCAECs were incubated for 24 h

following digestion, after which the culture medium was removed by

centrifugation (1,500 x g; at 4˚C for 5 min). Subsequent to washing

with PBS, 1x105 resuspended cells were seeded into the

Transwell chamber and incubated for an additional 24 h. The cells

were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at 37˚C for 15 min,

washed, and stained with crystal violet at 37˚C for 15 min. The

invasive cells were observed under a light microscope (Leica

Microsystems GmbH), and images were captured from three randomly

selected fields of view.

Wound healing assay

HCAECs were cultured in 6-well plates at a density

of 3x105 cells per well. Once the cells attained 100%

confluence, a scratch was created on the monolayer using a 10 µl

pipette tip. Subsequently, HCAECs were incubated in serum-free

EBM-2 at 37˚C for 48 h. The widths of the scratches at both 0 h

(initial width) and 48 h (final width) were observed using a light

microscope (Leica Microsystems GmbH). To assess the migratory

abilities of HCAECs, ImageTool software version 3.0 (UTHSCSA, San

Antonio, USA) was employed with the following formula: (Initial

width-final width)/initial width x100%.

RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP)

assay

The Magna RIP RNA-Binding Protein

Immunoprecipitation kit was used for RIP assays following the

manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, HCAECs were collected and lysed

using RIP lysis buffer. For each IP reaction, HCAECs

(2x107 cells) were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer

and incubated on ice for 30 min. The samples were then centrifuged

at 14,000 x g for 20 min at 4˚C. Whole-cell extracts were incubated

with RIP buffer (at 4˚C for 30 min) containing magnetic beads

conjugated to human anti-TFAP2A antibody or the control IgG. The

beads were then washed five times with 1 ml wash buffer and

centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 1 min at 4˚C between washes.

Subsequently, 100 µl of elution buffer was added in the samples to

incubate for 10 min at 65˚C. Proteinase K was added to the samples

to digest the protein, and the immunoprecipitated RNA was isolated.

Purified RNA was used for reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR) analysis. The expressional level of GAPDH was used as the

control.

RNA pull-down assay

The interaction between TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A

protein was examined using Pierce Magnetic RNA-Protein Pull-Down

kit according to the manufacturer's protocols. Proteins from HCAECs

were extracted using lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1%

NP-40, 10% glycerin, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM PMSF, 1X Protease inhibitor

cocktail, and 40 U/ml RNase). For each reaction, HCAECs

(5x106 cells) were resuspended in 1 ml of lysis buffer

and incubated on ice for 60 min. Biotin-labeled TFAP2A-AS1 or

antisense RNA was co-incubated with protein extract of HCAECs and

Protein G-magnetic beads (40 µl). The generated bead-RNA-Protein

compound was collected by low-speed centrifugation (800 x g for 2

min at 4˚C). After being washed with 2X SDS loading buffer, the

bead compound was boiled for 10 min in SDS buffer, and the

retrieved protein was detected by western blotting with the

expressional level of GAPDH as the control.

Animal grouping and treatment

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with

the Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by

the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou

Medical University (approval no. xmsq2022-1230). A total of 24

C57BL/6J mice, weighting 18-22 g and aged 8 to 10 weeks, were

procured from Pengsheng Biological Technology Co., Ltd. The ACS

mouse model was established in accordance with a previously

described protocol (15). C57BL/6J

mice were randomly assigned to four groups: Sham group, ACS model +

NC shRNA group, ACS model + TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA group, and ACS model +

TFAP2A shRNA group. Each group consisted of six mice. Anesthesia

was induced through an intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital

sodium at a dose of 50 mg/kg. The limbs of the mice were then

secured on a surgical table while maintaining them in a supine

position. A thoracotomy was performed to expose the heart, followed

by ligation of the anterior descending coronary artery using 6/0

surgical sutures. To prevent infection, each mouse was administered

a subcutaneous injection of penicillin at a dose of 50 mg/kg. By

contrast, the mice in the sham group underwent only threading

without ligation. Successful establishment of the ACS mouse model

was confirmed based on significantly elevated ST segment and/or

high T wave readings (data not shown). A three-plasmid system,

along with 9 µg of lentiviral vectors, was co-transfected into 293

cells using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection agent at room

temperature. The ratio of lentiviral plasmid to packaging vector to

envelope was maintained at 1:1:1. The lentivirus-containing culture

medium was harvested 48 h post-transfection and subsequently used

to infect MCAECs (second passage; 5x106 cells per well)

with a multiplicity of infection set at 20. Subsequently, 48 h

after infection, the cells were subjected to selection using 1

µg/ml puromycin. Prior to surgery, mice in the ACS model + NC shRNA

group received an intramyocardial injection containing lentiviral

vectors integrated with the NC shRNA sequence (50 µg;

5'-GGCAGGGTGATGGGCAACATA-3'). By contrast, those in both the ACS

model + TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA and ACS model + TFAP2A shRNA groups were

administered with lentiviruses carrying either the TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA

sequence (5'-GGCTGGTGAAGAACCTGAAGG-3') or the TFAP2A shRNA sequence

(5'-GAGTTGCTTGACCCACTTCAA-3'), respectively, via intramyocardial

injection (both at a dose of 50 µg). Anesthesia was maintained for

30 min. The humane endpoints were rapid or labored breathing. After

a two-week period, euthanasia was conducted on all groups using an

overdose of pentobarbital sodium administered via intraperitoneal

injection at a dose of 200 mg/kg. Death was confirmed by cardiac

and respiratory arrest and a lack of response to tail clamping.

Following the confirmation of death, whole blood samples (300 µl;

collected from the eyeballs) and heart tissues were collected for

further analysis.

RT-qPCR

The extraction of RNA from heart tissues of mice,

HCAECs, and serum samples of patients with ACS, was conducted using

the MiniBEST Universal RNA Extraction Kit. Subsequently, reverse

transcription into cDNA was performed at 45˚C for 45 min using the

PrimeScript RT reagent kit. PCR analysis was then conducted in

accordance with the SYBR Green Premix protocols on a QuantStudio7

system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The reaction conditions

consisted of an initial denaturation step at 95˚C for 2 min,

followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for 10 sec, annealing

at 60˚C for 30 sec, and extension at 72˚C for 30 sec. The primers

used in the present study are listed in Table II. The relative expression levels

of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A were normalized against GAPDH and

calculated using the 2-ΔΔCq method (16).

| Table IIReal-time PCR primer synthesis

list. |

Table II

Real-time PCR primer synthesis

list.

| Gene | Sequences |

|---|

| LncRNA

TFAP2A-AS1 | Forward

5'-GCATCCACGTCCTCTCTCTG-3' |

| | Reverse

5'-GCAGATTGTGGTACTGGCGA-3' |

| TFAP2A | Forward

5'-TCCGCTTCACGCTCGATTT-3' |

| | Reverse

5'-AATCCGTGTCTCCCCCTCTT-3' |

| GAPDH | Forward

5'-TCAAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGG-3' |

| | Reverse

5'-TCAAAGGTGGAGGAGTGGGT-3' |

Western blot analysis

The concentration of total proteins was determined

in HCAECs or heart tissues by extracting them with RIPA lysis

buffer, followed by measurement using a BCA kit. Subsequently, the

proteins were separated using 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel

electrophoresis and then transferred onto a PVDF membrane. The

membrane was blocked using 5% nonfat milk for 2 h at 25˚C.

Subsequently, primary antibodies (TFAP2A at a dilution of 1:5,000;

GAPDH at a dilution of 1:50,000) overnight at 4˚C, along with their

corresponding secondary antibodies (at a dilution of 1:1,000) at

37˚C for 1 h were incubated separately. For the purpose of protein

normalization, GAPDH was employed as a reference. The protein

signals were detected using an ECL kit and quantified with Alpha

Innotech software version 6.0 (Alpha Innotech Corporation).

Biochemical tests

The whole blood samples from mouse eyeballs were

maintained at ambient temperature for 2 h, followed by

centrifugation at a force of 1,000 x g for a 20 min at 4˚C. To

determine the serum levels of TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C, commercially

available kits were employed in conjunction with an automated

bioanalysis system (Gallery Plus Discrete Analyzer; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.).

H&E staining

The myocardial tissues of mice were subjected to

fixation (4% paraformaldehyde at 25˚C for 12 h), deparaffinization,

and hydration prior to embedding in paraffin. Subsequently, they

were sectioned into slices with a thickness of 4 µm. The sections

underwent a 3-min H&E staining process at 25˚C. Following the

application of neutral gum for mounting, the images were captured

using a Leica light microscope.

Statistical analysis

In vitro experiments were performed in

triplicate, and each experiment was repeated 3 times. In

vivo experiments were performed using six mice per group. The

differences between two groups were evaluated using unpaired

Student's t-test. To assess variations among multiple groups, a

one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc multiple comparisons

test was utilized. Data analysis was performed using SPSS software

version 22.0 (Dotmatics). The data were presented as the mean ±

standard deviation, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a

statistically significant difference.

Results

Serum from patients with ACS exhibits

elevated expression of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A

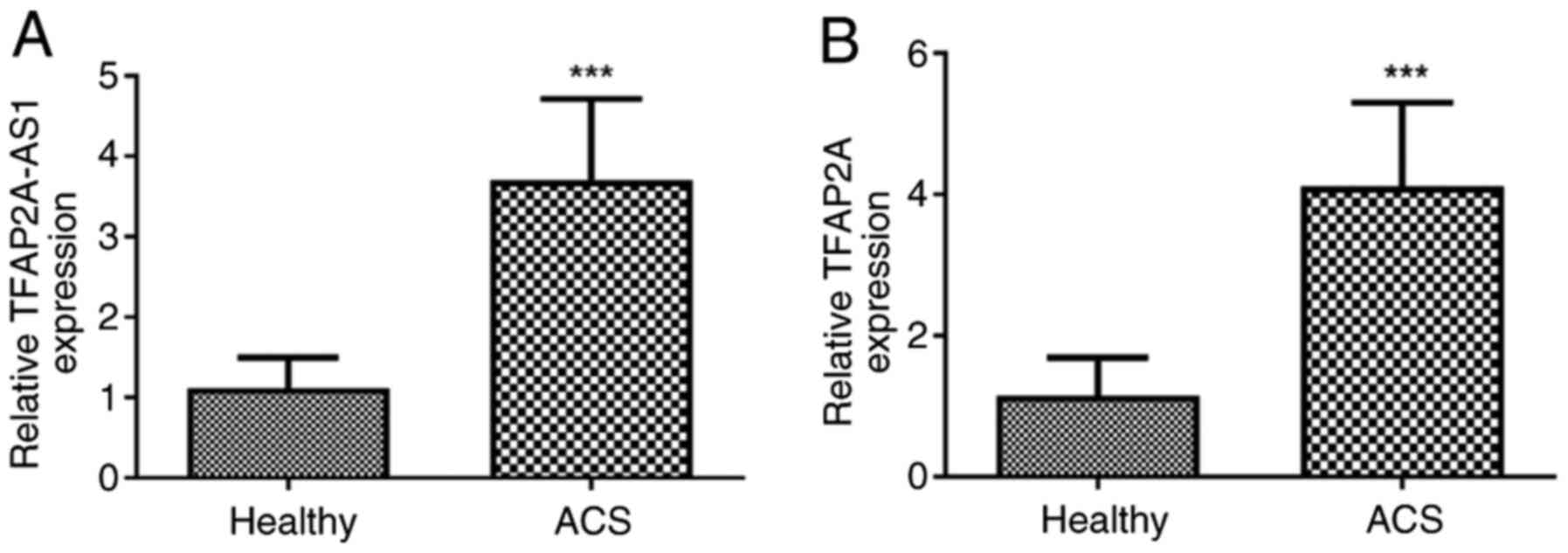

After obtaining the necessary consent from the

participants, venous blood samples were collected from individuals

diagnosed with ACS. Subsequently, centrifugation was conducted to

obtain serum samples, and then the expression levels of TFAP2A-AS1

and TFAP2A were determined using RT-qPCR. The findings, as depicted

in Fig. 1A, revealed a significant

upregulation of TFAP2A-AS1 expression in patients with ACS compared

with that observed in healthy individuals (P<0.001; Fig. 1B). Similarly, elevated levels of

TFAP2A were also detected in patients with ACS when compared with

controls without any health issues (P<0.001; Fig. 1B).

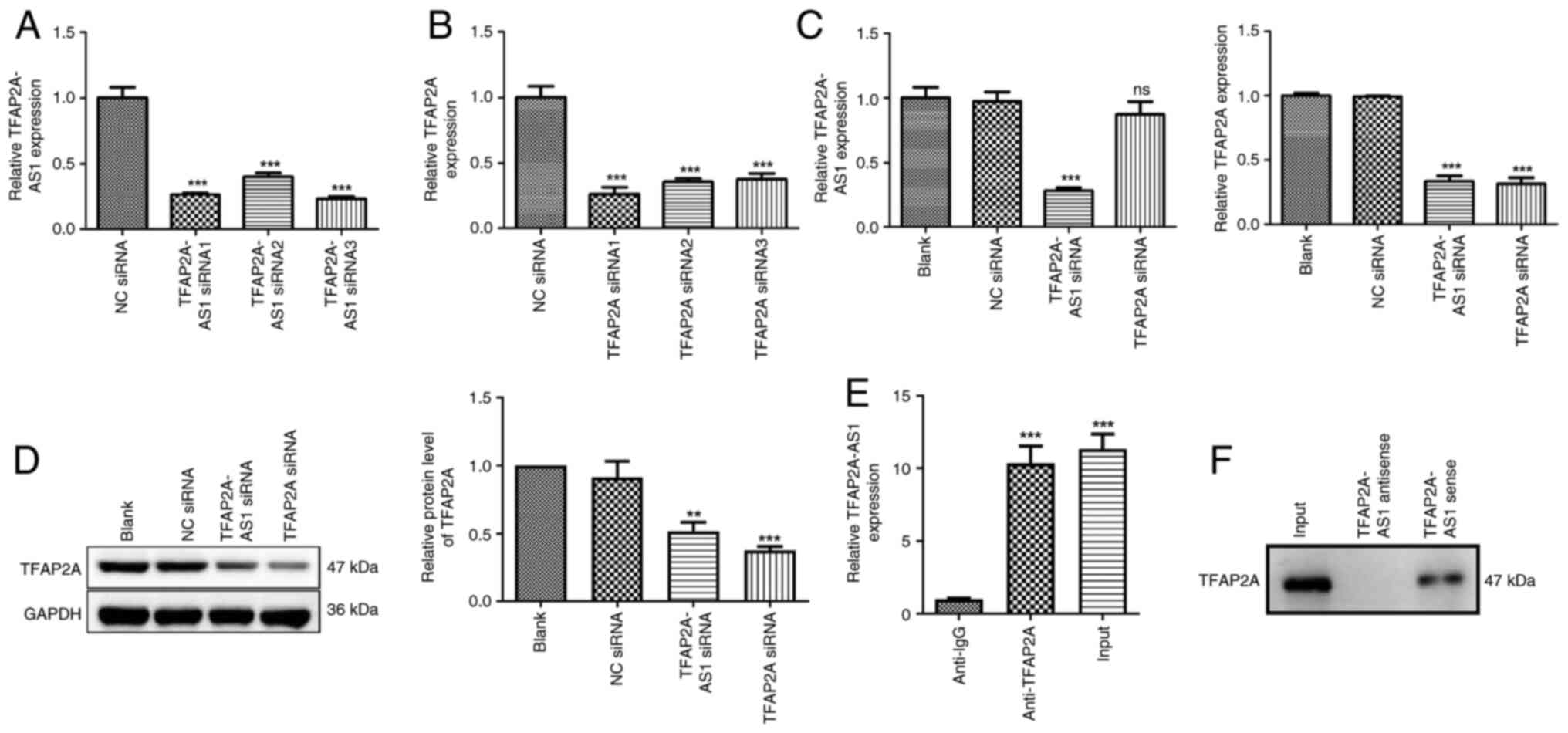

Silencing of TFAP2A-AS1 suppresses

TFAP2A expression

To investigate the roles of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A in

the progression of ACS in vitro, gene silencing techniques

were initially employed to downregulate the expression levels of

either TFAP2A-AS1 or TFAP2A in HCAECs. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the HCAECs were transfected with

TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA1, TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA2, and TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA3

individually. It was revealed that the expression level of

TFAP2A-AS1 was significantly decreased following transfection

(P<0.001). The selection of TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA3 for subsequent

experiments was based on its relatively high silencing efficiency.

Similarly, TFAP2A siRNA transfection also significantly inhibited

TFAP2A expression, and TFAP2A siRNA1 was selected for the

subsequent experiments (P<0.001; Fig. 2B). The regulatory associations

between TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A were then determined. The results of

RT-qPCR and western blotting demonstrated that transfection of

TFAP2A siRNA did not affect TFAP2A-AS1 expression, while

transfection of TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA markedly decreased the mRNA

expression and protein level of TFAP2A (P<0.01; Fig. 2C and D). The findings indicated that TFAP2A-AS1

possesses the capability to regulate the expression of TFAP2A;

however, the converse does not hold true. A RIP assay was performed

to confirm the functional interaction between TFAP2A-AS1 and

TFAP2A. RNA from RIP assays using an antibody against TFAP2A was

subjected to qPCR analysis, which demonstrated an enrichment of

TFAP2A-AS1 (P<0.001; Fig. 2E).

Next, whether TFAP2A-AS1 interacted with TFAP2A protein was

examined using an RNA pull-down assay, and it was revealed that the

expression level of TFAP2A interacting with biotin-labeled

TFAP2A-AS1 was higher than that with the antisense TFAP2A-AS1 group

(Fig. 2F). These data suggested the

interaction between TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A protein.

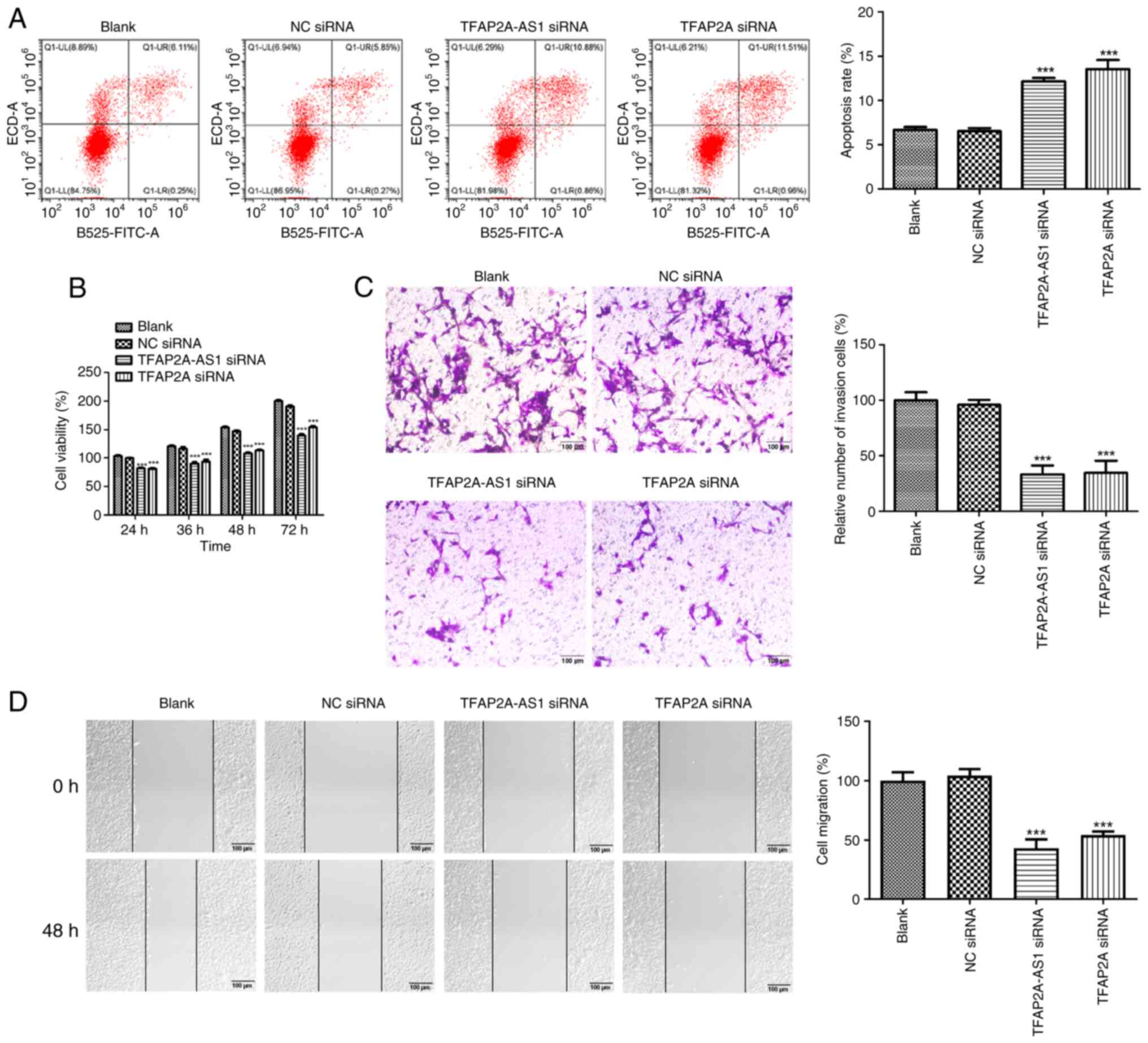

Silencing of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A

inhibits the proliferative, migratory, and invasive capacities

while enhancing the apoptotic rate of HCAECs

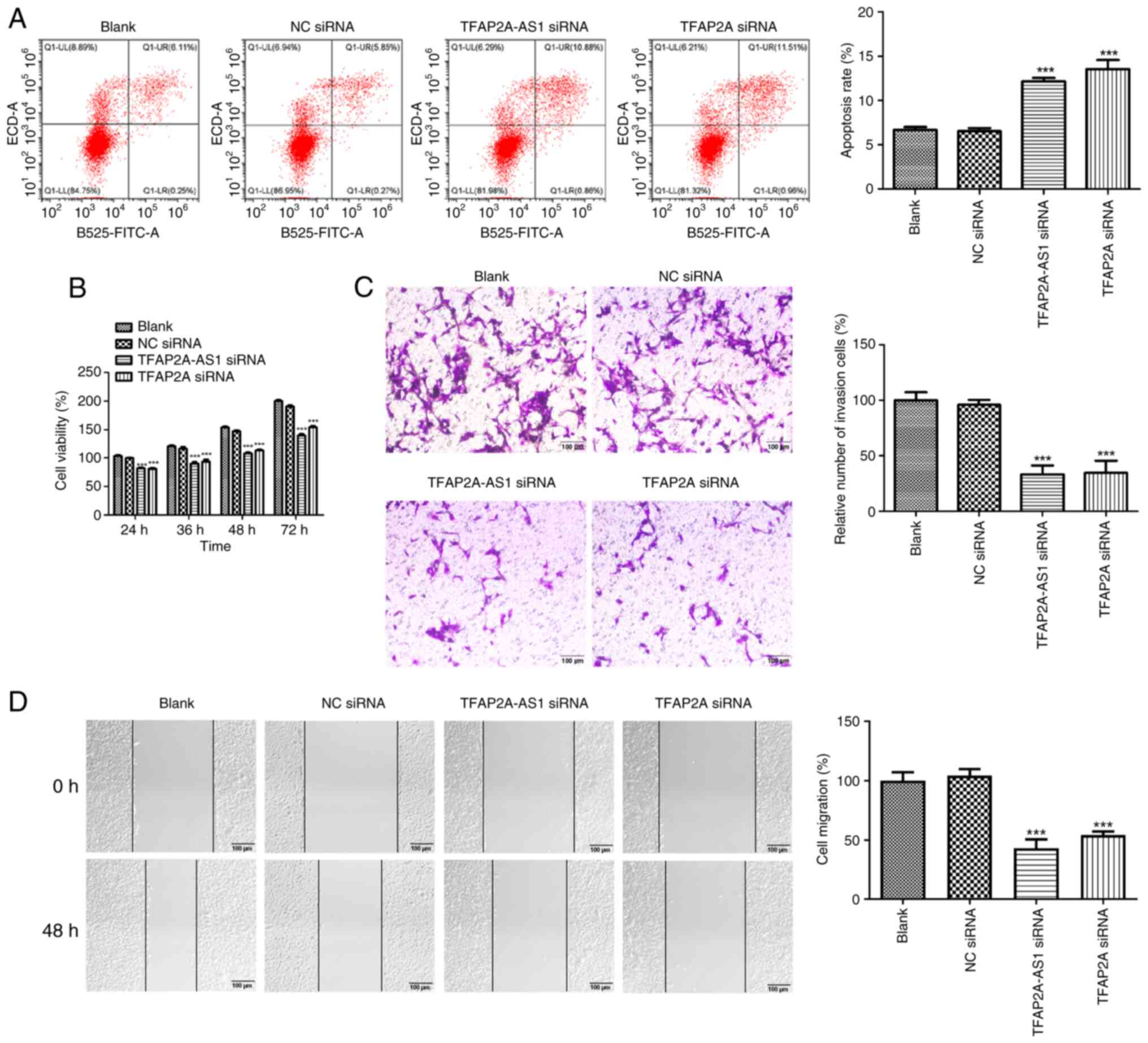

The flow cytometric analysis showed that

transfection of both TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA and TFAP2A siRNA

significantly increased the apoptosis rate of HCAECs (P<0.001;

Fig. 3A). Starting from 24 h, the

viability of HCAECs was significantly reduced following the

silencing TFAP2A-AS1 or TFAP2A (P<0.001; Fig. 3B). Additionally, the effects of

TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A on the invasive and migratory capacities of

HCAECs were also assessed. The relative number of invasive cells

was significantly decreased in the TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA and TFAP2A

siRNA groups compared with those in the NC siRNA group, as

demonstrated in Fig. 3C

(P<0.001). Similar patterns were observed in the effects of

TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA and TFAP2A siRNA on cell migration (P<0.001;

Fig. 3D).

| Figure 3Silencing of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A

suppresses the proliferative, migratory, and invasive capacities

while enhancing the apoptotic rate of HCAECs. (A) The apoptosis

rate, (B) viability, (C) invasion and (D) migration of HCAECs

transfected TFAP2A-AS1 siRNA, TFAP2A siRNA or NC siRNA was assessed

by flow cytometric analysis, Counting Kit-8 assay, Transwell

invasion assay and wound healing assay, respectively. Scale bar,

100 µm. ***P<0.001 vs. NC siRNA. TFAP2A,

transcription factor AP-2α; HCAECs, human coronary artery

endothelial cells; siRNA, small interfering RNA; NC, negative

control. |

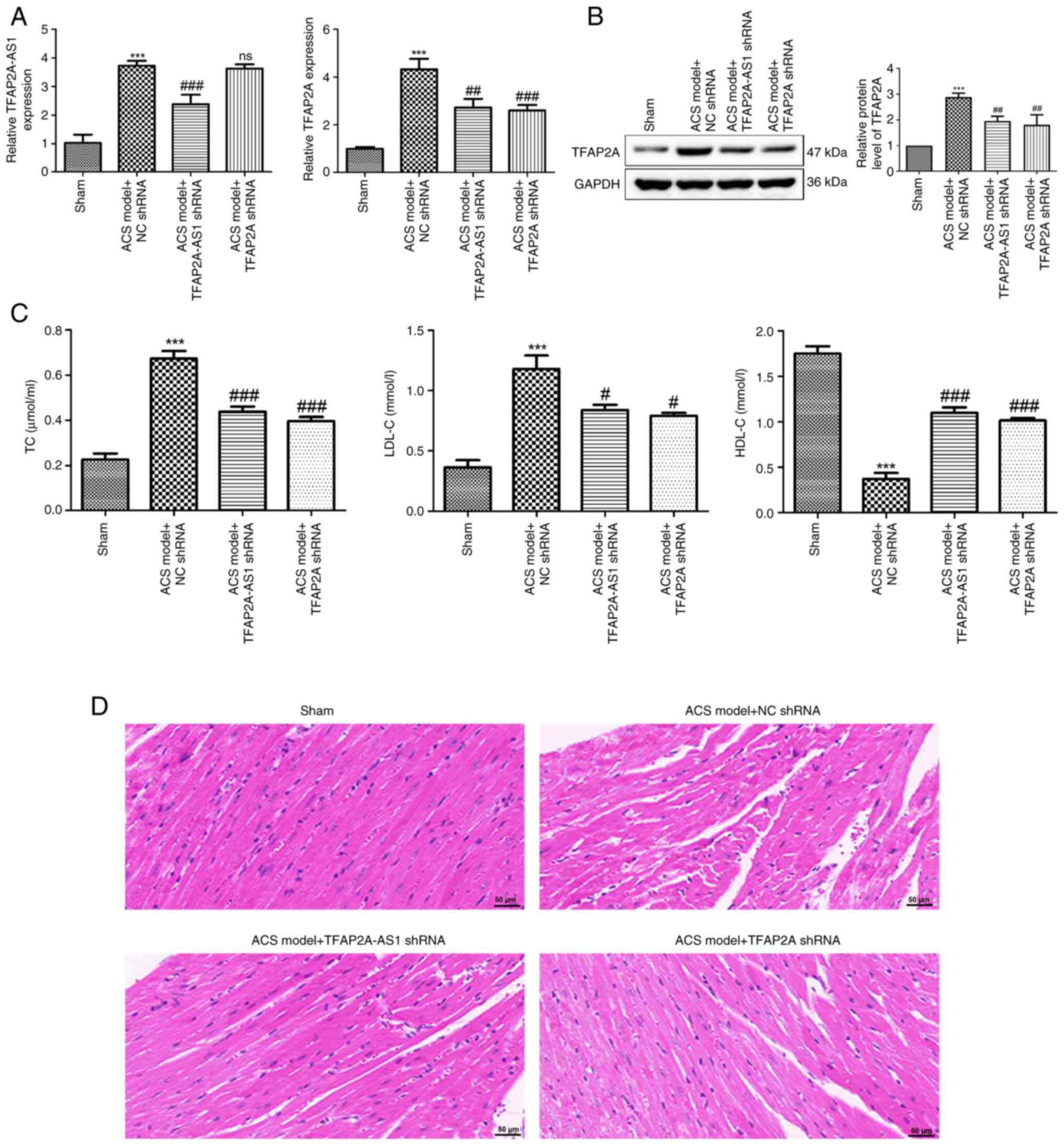

Knockdown of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A

leads to a decrease in the serum lipid levels and an improvement in

myocardial injury in a mouse model of ACS

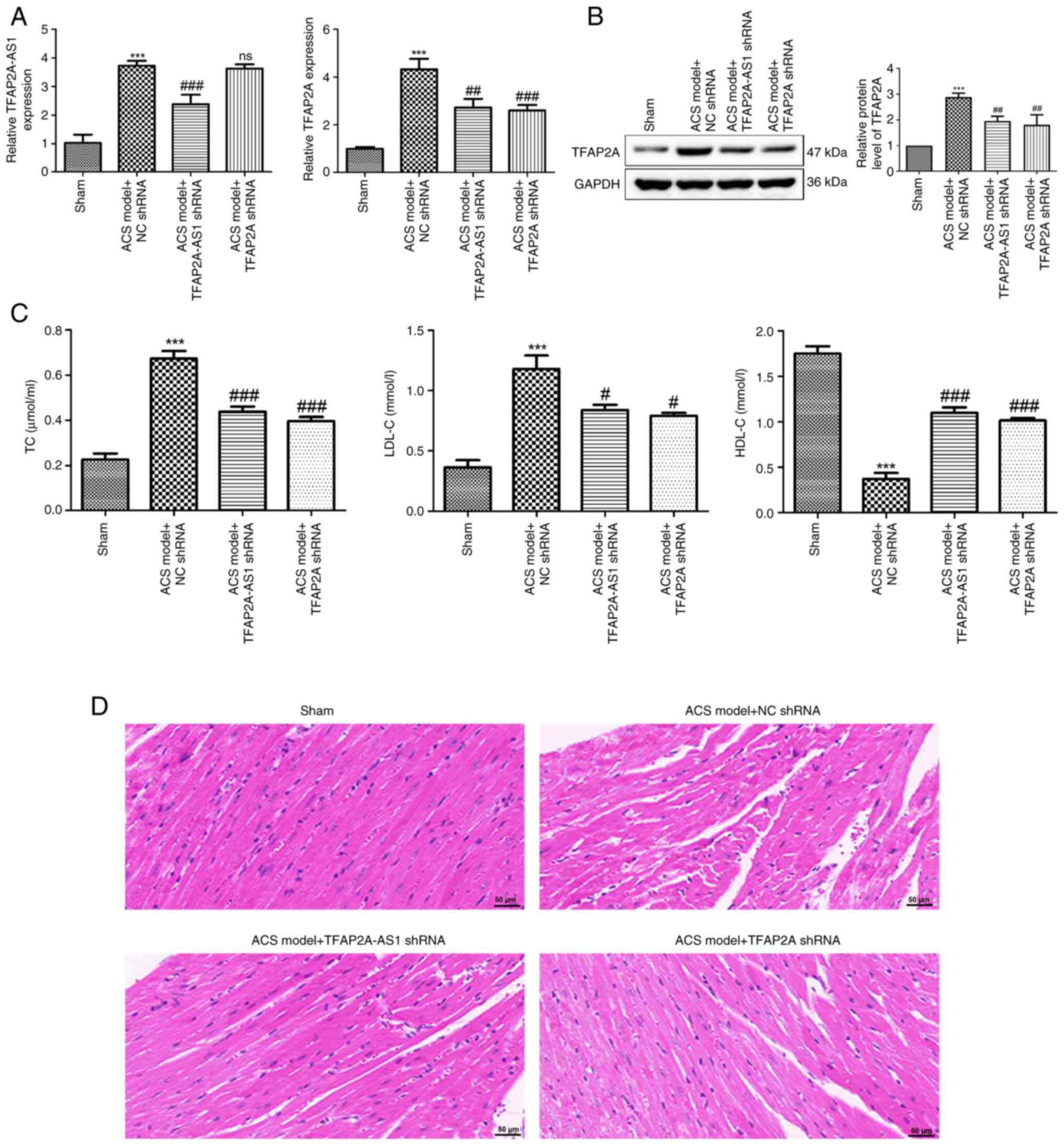

A mouse model of ACS was established in the present

study. As demonstrated in Fig. 4A,

the expression of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A was significantly increased

in mice with ACS (P<0.001). However, their expression levels

were reduced after injection of TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA and TFAP2A shRNA,

respectively (P<0.001). Notably, injection of TFAP2A shRNA did

not affect the expression of TFAP2A-AS1, while injection of

TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA significantly decreased the mRNA expression of

TFAP2A in mice with ACS (P<0.01). Moreover, similar patterns

were observed for the protein level of TFAP2A (P<0.01; Fig. 4B). Furthermore, it was revealed that

compared with the sham group, the serum levels of TC and LDL-C were

significantly elevated in a mouse model of ACS (P<0.001;

Fig. 4C), while the levels of HDL-C

were significantly decreased (P<0.001). Notably, the

intramyocardial injection of both TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA and TFAP2A shRNA

not only led to a reduction in the levels of TC and LDL-C

(P<0.05), but also resulted in increased levels of HDL-C

(P<0.001) in mice with ACS. Subsequently, heart tissues from

mice across various groups were collected for the purpose of

pathological examination. As depicted in Fig. 4D, cardiomyocytes from the sham group

exhibited a normal morphology characterized by a well-organized

arrangement and an absence of breaks. By contrast, cardiomyocytes

derived from the ACS mice displayed signs of swelling and

thickening, accompanied by irregular morphology and disordered

arrangement. Following intramyocardial injection of both TFPAF-A21

shRNA and TFAF-A21 shRNA, a significant improvement in the

morphology and arrangement of cardiomyocytes was observed.

| Figure 4Knockdown of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A

leads to a reduction in serum lipid levels and an improvement in

myocardial injury in an ACS mouse model. (A) The expression of

TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A in ACS mice after injection of TFAP2A-AS1

shRNA, TFAP2A shRNA or NC shRNA was detected by reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR. (B) The protein levels of TFAP2A in

ACS mice after injection of TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA, TFAP2A shRNA or NC

shRNA were determined using western blotting. (C) The levels of TC,

LDL-C and HDL-C in ACS mice after injection of TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA,

TFAP2A shRNA or NC shRNA were determined using biochemical tests.

(D) Hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed to observe the

pathological condition of myocardial tissues in different groups.

Scale bar, 50 µm. ***P<0.001 vs. sham;

#P<0.05, ##P<0.01, and

###P<0.001 vs. the ACS model + NC shRNA. TFAP2A,

transcription factor AP-2α; ACS, acute coronary syndrome; shRNA,

short hairpin RNA; ns, no significance. |

Discussion

Despite significant advancements in the diagnosis

and treatment of ACS, CVDs remain the leading cause of death

globally. Low- and middle-income countries bear a considerable

burden, with ~7 million deaths and 129 million cases of disability

reported annually (17-19).

Furthermore, despite a significant decline in mortality rates

associated with ACS, it is still estimated that ~40% of patients

will succumb to death within five years following a coronary event.

The risk of fatality increases 5 to 6-fold in individuals who

experience recurrent events (20,21).

The economic impact associated with ACS is also substantial; with

each patient in the U.S. incurring an estimated annual cost ranging

from $22,528 to $32,345 primarily due to hospitalizations (22). Consequently, ACS not only imposes a

significant burden on patients but also affects society at large.

Therefore, there is an urgent need to explore more effective

treatment options for this condition.

Most research on lncRNA TFAP2A-AS1 primarily focuses

on its role in cancer. Aberrant expression of TFAP2A-AS1 has been

shown to influence the occurrence and development of multiple human

cancers, including GC, BC, NSCLC and OSCC (11-14).

In the present study, the dysregulation of TFAP2A-AS1 was also

observed in both patients with ACS and corresponding mouse models,

suggesting that TFAP2A-AS1 may be significantly associated with the

progression of ACS. The significance of endothelial cells in the

pathogenesis of ACS should not be underestimated. The pathology of

ACS represents a complex and multifaceted process, with plaque

rupture identified as one of its primary triggers (3,23).

Following a myocardial infarction, significant alterations occur in

the behavior of endothelial cells, which are crucial for

angiogenesis. Consequently, the abnormal proliferation, migration

and invasion of these endothelial cells post-myocardial infarction

may potentially contribute to plaque instability and erosion,

ultimately leading to the onset and development of ACS (24,25).

In the present study, it was demonstated that knockdown of

TFAP2A-AS1 not only significantly suppressed the proliferative,

invasive and migrated potentials of HCAECs, but also markedly

increased the apoptosis rate. Furthermore, previous studies have

reported that elevated levels of TC and LDL-C are associated with

endothelial dysfunction (26,27).

Based on the findings of the present study which demonstrated that

silencing of TFAP2A-AS1 effectively inhibited the aberrant

proliferation, invasion, and migration of HCAECs, it is reasonable

to propose that the downregulation of TFAP2A-AS1 may play a pivotal

role in regulating blood lipid levels. In the animal experiments,

as anticipated, a significant reduction in the levels of TC and

LDL-C, accompanied by an elevation in the levels of HDL-C were

observed upon the injection of TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA in mice with ACS.

The aforementioned results indicated that the downregulation of

TFAP2A-AS1 may play a crucial role in the regulation of endothelial

dysfunction. Moreover, the myocardial injury symptoms observed in

ACS mice were significantly ameliorated following the injection of

TFAP2A-AS1 shRNA. Therefore, the findings indicated that the

absence of TFAP2A-AS1 may confer a beneficial effect on mitigating

the progression of ACS.

TFAP2A, a member of the AP-2 family, has been

identified as a transcription factor involved in various aspects of

development (28). In

branchio-oculo-facial syndrome, a rare autosomal-dominant disorder

characterized by cleft palate and craniofacial abnormalities, a

deletion in the TFAP2A gene has been observed (29). Additionally, studies have shown that

the expression of TFAP2A is upregulated and functions as an

oncogene in the progression of various cancers, including cervical

cancer, gallbladder carcinoma, and ovarian cancer (30-32).

Moreover, TFAP2A is essential for cardiac morphogenesis

specifically during outflow tract formation and cardiac septation

by regulating cell proliferation and terminal differentiation

(33,34). It was therefore hypothesized that

TFAP2A may also play a crucial role in ACS. In the present study,

an increased expression of TFAP2A in both patients with ACS and a

mouse model was observed Moreover, it was also demonstrated that

the knockdown of TFAP2A could modulate endothelial dysfunction by

inhibiting blood lipid levels in ACS mice, as well as suppressing

the aberrant proliferation, migration and invasion of HCAECs. All

these results supported our hypothesis that TFAP2A is associated

with the progression of ACS. Additionally, a recent study by Yang

et al (35) demonstrated

that the expression levels of both TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A were

upregulated in OSCC, exhibiting a positive correlation between

their expression levels. This suggested that TFAP2A-AS1 can

interact with TFAP2A to affect OSCC progression. Based on the

observed effects of TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A on HCAECs and mouse

models, a potential association between TFAP2A-AS1 and TFAP2A in

the progression of ACS was postulated. The findings demonstrated

that knockdown of TFAP2A-AS1 led to decreased expression of TFAP2A,

while no reciprocal effect was observed for TFAP2A on the

expression of TFAP2A-AS1. In addition, the RIP and RNA pull-down

assays further verified the interaction of TFAP2A-AS1 with TFAP2A.

These results suggest a positive regulatory role for TFAP2A-AS1 in

modulating the expression of TFAP2A. Consequently, the present

study concludes that the silencing of TFAP2A-AS1 may impede the

progression of ACS by inhibiting the expression of TFAP2.

Some limitations that must be acknowledged in this

study are as follows: Firstly, confirming whether TFAP2A-AS1

regulates TFAP2A expression in a post-transcriptional manner may

require a more rigorous approach. Secondly, the sample size of

patients was relatively limited, and increasing the sample size

would provide more robust data and enhance the statistical power of

the findings. Thirdly, the study was conducted on a specific

population in Wenzhou, China. Expanding the research to include

diverse populations in China, will be considered in future

studies.

In summary, the present research demonstrated that

TFAP2A-AS1 acts as a pathogenic lncRNA in ACS. The suppression of

TFAP2A-AS1 led to a significant decrease in TFAP2A expression,

thereby hindering the progression of ACS through the regulation of

endothelial dysfunction. This newly identified regulatory axis may

represent a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of

ACS.

Acknowledgements

Not available.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Wenzhou Municipal

Science and Technology Plan Project (grant no. Y20210160).

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the corresponding author

on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

HC and SHu made substantial contributions to the

conception and design of the study. SHu, FG, FY, BY, and SHa made

substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis and

interpretation of data for the study. SHu drafted the manuscript.

SHu, FG, FY, BY, SHa, and HC revised the manuscript critically for

important intellectual content. SHu, FG, FY, BY, SHa, and HC

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be to be

accountable for all aspects of the research in ensuring that the

accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately

investigated and resolved.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The patients/participants provided their written

informed consent to participate in this study. The human study was

conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of

Helsinki and approved (approval no. KY-2021053) by the Ethics

Committee of Wenzhou People's Hospital (Wenzhou, China). Animal

experiments were conducted in compliance with the Guidelines for

the Use of Laboratory Animals and approved (approval no.

xmsq2022-1230) by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated

Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Wenzhou, China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

WHO CVD Risk Chart Working Group. World

Health Organization cardiovascular disease risk charts: Revised

models to estimate risk in 21 global regions. Lancet Glob Health.

7:e1332–e1345. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, Capodanno D,

Barbato E, Funck-Brentano C, Prescott E, Storey RF, Deaton C,

Cuisset T, et al: 2019 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and

management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 41:407–477.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Collet JP, Thiele H, Barbato E, Barthélémy

O, Bauersachs J, Bhatt DL, Dendale P, Dorobantu M, Edvardsen T,

Folliguet T, et al: 2020 ESC guidelines for the management of acute

coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent

ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 42:1289–1367. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kaul P, Ezekowitz JA, Armstrong PW, Leung

BK, Savu A, Welsh RC, Quan H, Knudtson ML and McAlister FA:

Incidence of heart failure and mortality after acute coronary

syndromes. Am Heart J. 165:379–385.e2. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

McKnight AH, Katzenberger DR and Britnell

SR: Colchicine in acute coronary syndrome: A systematic review. Ann

Pharmacother. 55:187–197. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Smith JN, Negrelli JM, Manek MB, Hawes EM

and Viera AJ: Diagnosis and management of acute coronary syndrome:

An evidence-based update. J Am Board Fam Med. 28:283–293.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Wang L and Jin Y: Noncoding RNAs as

biomarkers for acute coronary syndrome. Biomed Res Int.

2020(3298696)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chen H, Huang S, Guan F, Han S, Ye F, Li X

and You L: Targeting circulating lncRNA ENST00000538705.1 relieves

acute coronary syndrome via modulating ALOX15. Dis Markers.

2022(8208471)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Barbalata T, Niculescu LS, Stancu CS,

Pinet F and Sima AV: Elevated levels of circulating lncRNAs LIPCAR

and MALAT1 predict an unfavorable outcome in acute coronary

syndrome patients. Int J Mol Sci. 24(12076)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Chen L and Huang Y: High expression of

lncRNA PELATON serves as a risk factor for the incidence and

prognosis of acute coronary syndrome. Sci Rep.

12(8030)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Zhao X, Chen L, Wu J, You J, Hong Q and Ye

F: Transcription factor KLF15 inhibits the proliferation and

migration of gastric cancer cells via regulating the

TFAP2A-AS1/NISCH axis. Biol Direct. 16(21)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Zhou B, Guo H and Tang J: Long non-coding

RNA TFAP2A-AS1 inhibits cell proliferation and invasion in breast

cancer via miR-933/SMAD2. Med Sci Monit. 25:1242–1253.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Zhang Y, Ma L, Zhang T, Li P, Xu J and

Wang Z: Long noncoding RNA TFAP2A-AS1 exerts promotive effects in

non-small cell lung cancer progression via controlling the

microRNA-548a-3p/CDK4 axis as a competitive endogenous RNA. Oncol

Res. 29:129–139. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Jie G, Peng S, Cui Z, He C, Feng X and

Yang K: Long non-coding RNA TFAP2A-AS1 plays an important role in

oral squamous cell carcinoma: Research includes bioinformatics

analysis and experiments. BMC Oral Health. 22(160)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Luo XY, Zhu XQ, Li Y, Wang XB, Yin W, Ge

YS and Ji WM: MicroRNA-150 restores endothelial cell function and

attenuates vascular remodeling by targeting PTX3 through the NF-κB

signaling pathway in mice with acute coronary syndrome. Cell Biol

Int. 42:1170–1181. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Vedanthan R, Seligman B and Fuster V:

Global perspective on acute coronary syndrome: A burden on the

young and poor. Circ Res. 114:1959–1975. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Moran AE, Oliver JT, Mirzaie M,

Forouzanfar MH, Chilov M, Anderson L, Morrison JL, Khan A, Zhang N,

Haynes N, et al: Assessing the global burden of ischemic heart

disease: Part 1: Methods for a systematic review of the global

epidemiology of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010. Glob

Heart. 7:315–329. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Forouzanfar MH, Moran AE, Flaxman AD, Roth

G, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Naghavi M and Murray CJ: Assessing the

global burden of ischemic heart disease, part 2: Analytic methods

and estimates of the global epidemiology of ischemic heart disease

in 2010. Glob Heart. 7:331–342. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Rogers WJ, Canto JG, Lambrew CT,

Tiefenbrunn AJ, Kinkaid B, Shoultz DA, Frederick PD and Every N:

Temporal trends in the treatment of over 1.5 million patients with

myocardial infarction in the US from 1990 through 1999: The

national registry of myocardial infarction 1, 2 and 3. J Am Coll

Cardiol. 36:2056–2063. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Thom T, Haase N, Rosamond W, Howard VJ,

Rumsfeld J, Manolio T, Zheng ZJ, Flegal K, O'Donnell C, Kittner S,

et al: Heart disease and stroke statistics-2006 update: A report

from the American heart association statistics committee and stroke

statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 113:e85–e151. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Menzin J, Wygant G, Hauch O, Jackel J and

Friedman M: One-year costs of ischemic heart disease among patients

with acute coronary syndromes: Findings from a multi-employer

claims database. Curr Med Res Opin. 24:461–468. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Libby P and Pasterkamp G: Requiem for the

‘vulnerable plaque’. Eur Heart J. 36:2984–2987. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Bonetti PO, Lerman LO and Lerman A:

Endothelial dysfunction: A marker of atherosclerotic risk.

Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 23:168–175. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Zhu F, Wang Q, Guo C, Wang X, Cao X, Shi

Y, Gao F, Ma C and Zhang L: IL-17 induces apoptosis of vascular

endothelial cells: A potential mechanism for human acute coronary

syndrome. Clin Immunol. 141:152–160. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Stein RA: Endothelial dysfunction,

erectile dysfunction, and coronary heart disease: The

pathophysiologic and clinical linkage. Rev Urol. 5 (Suppl

7):S21–S27. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Ling L, Zhao SP, Gao M, Zhou QC, Li YL and

Xia B: Vitamin C preserves endothelial function in patients with

coronary heart disease after a high-fat meal. Clin Cardiol.

25:219–224. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yang YL and Zhao LY: AP-2 family of

transcription factors: Critical regulators of human development and

cancer. J Cancer Treat Diagn. 5:1–4. 2021.

|

|

29

|

Gestri G, Osborne RJ, Wyatt AW, Gerrelli

D, Gribble S, Stewart H, Fryer A, Bunyan DJ, Prescott K, Collin JR,

et al: Reduced TFAP2A function causes variable optic fissure

closure and retinal defects and sensitizes eye development to

mutations in other morphogenetic regulators. Hum Genet.

126:791–803. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zhang P, Hou Q and Yue Q:

MiR-204-5p/TFAP2A feedback loop positively regulates the

proliferation, migration, invasion and EMT process in cervical

cancer. Cancer Biomark. 28:381–390. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Huang HX, Yang G, Yang Y, Yan J, Tang XY

and Pan Q: TFAP2A is a novel regulator that modulates ferroptosis

in gallbladder carcinoma cells via the Nrf2 signalling axis. Eur

Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 24:4745–4755. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Xu H, Wang L and Jiang X: Silencing of

lncRNA DLEU1 inhibits tumorigenesis of ovarian cancer via

regulating miR-429/TFAP2A axis. Mol Cell Biochem. 476:1051–1061.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Hutson MR and Kirby ML: Model systems for

the study of heart development and disease. Cardiac neural crest

and conotruncal malformations. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 18:101–110.

2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hammer S, Toenjes M, Lange M, Fischer JJ,

Dunkel I, Mebus S, Grimm CH, Hetzer R, Berger F and Sperling S:

Characterization of TBX20 in human hearts and its regulation by

TFAP2. J Cell Biochem. 104:1022–1033. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Yang K, Niu Y, Cui Z, Jin L, Peng S and

Dong Z: Long noncoding RNA TFAP2A-AS1 promotes oral squamous cell

carcinoma cell growth and movement via competitively binding

miR-1297 and regulating TFAP2A expression. Mol Carcinog.

61:865–875. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|