Introduction

Diabetes is one of the most common and serious

global health problems, as well as one of fastest growing chronic

diseases (1). For the 10th edition

of the IDF Diabetes Atlas, by 2045, the global prevalence of

diabetes among adults aged 20-79 years is projected to increase

from 9% (463 million adults) in 2019 to 12.2% (783.2 million)

(2). Among all cases of diabetes,

type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounts for ~90% of all cases

(3). Obesity is an important risk

factor for T2D (4). The increase in

free fatty acids (FFAs) caused by obesity plays a crucial role in

the occurrence and development of T2D (4).

T2D is characterized by insufficient insulin

secretion and chronic hyperglycemia caused by pancreatic β-cell

dysfunction (5). Regulating glucose

transporter 2 (GLUT2) is a key protein for β-cell function and a

transmembrane protein expressed in pancreatic β-cells, liver,

kidneys and intestines, playing a key role in glucose sensing and

insulin secretion (6). GLUT2 has a

low affinity but high transport capacity for glucose, allowing

β-cells to rapidly take up glucose when blood levels rise. This

triggers metabolic pathways that increase intracellular ATP,

leading to insulin secretion (7).

The dysregulation of GLUT2 expression or function impairs glucose

sensing and insulin release, which has been reported to contribute

to β-cell dysfunction and the pathogenesis of T2D (8,9).

Among the various factors implicated in β-cell

dysfunction, chronic exposure to high levels of FFAs is a major

factor (10), with evidence

suggesting that elevated FFAs have deleterious effects on β-cell

function and survival, a phenomenon often referred to as

lipotoxicity (5,11). Research has shown that metabolic

stressors, such as elevated FFAs, can alter GLUT2 expression,

further exacerbating β-cell dysfunction (12). A saturated fatty acid, palmitic acid

(PA), has been shown to impair glucose-stimulated insulin release

(13-17),

and can induce lipotoxicity, leading to β-cell dysfunction and

apoptosis (often referred to as lipotoxic β-cell apoptosis)

(10,15,18,19).

PA can exert these detrimental effects on β-cells

through various mechanisms, including the induction of endoplasmic

reticulum (ER) stress, oxidative stress and inflammatory response

(20). Given their critical role in

insulin synthesis, β-cells have a highly developed ER network to

synthesize insulin. Consequently, ER stress is particularly

important in β-cell dysfunction (21). Under stress conditions, it leads to

the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER and the activation

of the unfolded protein response (UPR) (22). Long-term or excessive ER stress

eventually triggers β-cell apoptosis, leading to the gradual loss

of functional β-cells in patients with T2D (23).

A recent study highlighted the role of specific ER

proteins in regulating ER stress and β-cell survival (24). Endoplasmic reticulum-resident

protein 46 (ERp46), a thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase that is highly

expressed in endothelial cells, pancreatic β-cells, hepatocytes and

hypoxic tissues (25-27),

plays a crucial role in protein folding and redox regulation

(24,28). ERp46 has been identified as a key

regulator of cellular homeostasis, and its activity is particularly

important under conditions of ER stress, including maintenance of

β-cell function and involvement in insulin secretion (29). In addition, GLUT2 plays a role in

the intracellular signaling pathways involved in glucose uptake and

metabolism in ER stress and apoptosis (30), suggesting that ERp46 may also be

linked to these processes, although this has not been directly

demonstrated. Despite the potential importance of ERp46 in β-cell

function and the fact that its expression is reduced in β-cells in

diabetic mouse models and under high glucose stimulation (31), the mechanisms through which ERp46

regulates β-cells in diabetic mouse models and, particularly how it

may link ER stress to GLUT2 expression, remain unclear. The aim of

the present study was to explore the role of ERp46 in pancreatic

β-cells, particularly in the regulation of insulin secretion under

PA-induced lipotoxic stress. By elucidating the molecular mechanism

through which ERp46 affects β-cell function, this study may help

develop novel therapeutic strategies targeting ER stress to

preserve β-cell function in patients with T2D.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and PA treatment

The β-TC6 mouse insulinoma cell line was purchased

from the National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures. Cells

were maintained in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) supplemented

with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) at 37˚C and 5% CO2. A stock solution of PA

(Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA) was prepared in 100% ethanol at 55˚C

until it was completely dissolved at a concentration of 100 mM. The

final ethanol concentration in culture did not exceed 0.1% (v/v),

and vehicle controls were included accordingly. Prior to PA

treatment, the stock solution was added to DMEM with 10% FBS at the

indicated concentrations.

AKT activator compound SC79 (SC79)

treatment

SC79 (Selleck Chemicals) was dissolved in DMSO to

prepare a 50-mM stock solution stored at -20˚C. For experiments,

the stock was diluted in DMEM to a final concentration of 5 or 10

µM, ensuring the DMSO concentration did not exceed 0.1%. β-TC6

cells at 70-80% confluency were treated with SC79 for 4 h at 37˚C,

5% CO2. DMSO-treated cells were used as controls.

Following treatment, cells were harvested for protein extraction or

insulin secretion assays.

Differential expression analysis and

functional enrichment

RNA-seq data (GSE53949) was downloaded from the GEO

database (32) and analyzed in

RStudio (version 1.4.1717; Posit PBC) using the DESeq2 package

(version 1.30.1; https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html).

GSE53949 included five control and five PA-treated human pancreatic

islets samples; all ten samples were used for differential and

correlation analyses. Following initial quality control,

normalization was performed to adjust for library size variations.

Differential expression analysis identified genes with

|log2FC|>1 and P<0.05 as significant, and P-values were

adjusted using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control for false

discovery rate. Volcano plots were generated with ggplot2 (version

3.3.5; http://ggplot2.tidyverse.org), where

upregulated genes were highlighted in red and downregulated genes

in green. Functional enrichment, including Gene Ontology

(http://geneontology.org) and Kyoto Encyclopedia

of genes and genomes (KEGG; https://www.genome.jp/kegg/) pathway analysis, was

conducted using the clusterProfiler package (version 4.0.5;

http://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html),

and results were visualized through bar plots. To assess the

relationship between thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5

[TXNDC5 (ERp46)] and solute carrier family 2 member 2

[SLC2A2 (GLUT2)], Pearson's correlation analysis was

conducted using normalized RNA-seq expression data. A linear

regression model was applied, and the coefficient of determination

(R²) was calculated to quantify the strength of the correlation.

Scatter plots with fitted regression lines were generated to

visualize the results.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR

(RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from β-TC6 cells using

TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.).

First-strand complementary DNA was synthesized using the

Hifair® II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Shanghai

Yeasen Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's

instructions. Subsequently, RT-qPCR was performed using the

Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (Shanghai Yeasen

Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) according to the standard method. The

thermocycling conditions were as follows: Initial denaturation at

95˚C for 2 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95˚C for

10 sec and annealing/extension at 60˚C for 30 sec. A melting curve

analysis was performed to verify amplification specificity. The

relative expression (fold) was calculated using the comparative

method 2-ΔΔCq method (33). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used for normalization. The primer

sequences are shown in Table I.

| Table IPrimer sequences used for

quantitative PCR analysis of target genes in β-cells. |

Table I

Primer sequences used for

quantitative PCR analysis of target genes in β-cells.

| Primer | Sequence

(5'-3') |

|---|

| ERp46-F |

GGATGCCAAGGTCTACGTG |

| ERp46-R |

CGGAGCGAAGAACTTGATA |

| PDX1-F |

GGCGGCCGCAGGAACCAC |

| PDX1-R |

GAGGGCCCCAATACTACAAAAACC |

| GLUT2-F |

CCTGCTTGGCCTGTCTGGTGT |

| GLUT2-R |

TGTCGGTAGCTGGAATTGGTGAAG |

| GAPDH-F |

CGGGGCTCTCCAGAACATCATCC |

| GAPDH-R |

CCAGCCCCAGCGTCAAAGGTG |

Cell protein extraction

The culture dish in which β-TC6 cells were seeded

was washed twice with cold PBS to completely remove the culture

medium, and the cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (Beijing

Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.) supplemented with

protease inhibitors. After gently scraping the cells with a cell

scraper, they were transferred to a 1.5 ml Eppendorf tube and

incubated on ice for 30 min for lysis. The cells were vortexed

every 5 min to enhance protein extraction. The lysate was

centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 15 min at 4˚C to precipitate cell

debris. The supernatant containing the extracted protein was

carefully transferred to a new tube for subsequent analysis.

Protein quantification

Protein concentration was determined using the

bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). A

standard curve was prepared using bovine serum albumin (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.) as a standard. Protein samples were added

to different wells of a 96-well plate. Subsequently, 200 µl of BCA

reagent mixture (comprised of reagent A and reagent B mixed at a

ratio of 50:1) was added to each well. The plate was incubated at

37˚C for 30 min, and absorbance was measured at 562 nm using a

microplate reader. Protein concentration was calculated by

comparing the absorbance of the sample with the standard curve.

Depending on the concentration, protein samples were diluted to 1

µg/µl using RIPA and then added to protein loading buffer, boiled

at 100˚C for 5 min, aliquoted and stored in a freezer at -80˚C.

Western blotting

Protein samples (50 µg) were separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Wuhan Servicebio

Technology Co., Ltd.). Following blocking with 5% skim milk in TBST

for 1 h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with

primary antibodies overnight at 4˚C: Anti-ERp46 (1:1,000; cat. no.

sc-271667; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-GLUT2 (1:1,000;

cat. no. K006592P; Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co.,

Ltd.), anti-p-Akt (1:1,000; cat. no. GB150002), anti-Akt (1:1,000;

cat. no. GB111114), anti-pancreatic and duodenal homeobox 1 (PDX1;

1:1,000; cat. no. GB11917), and anti-tubulin (1:2,000; cat. no.

GB11017; all from Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.),

anti-binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP; 1:1,000; cat. no. 3177T),

C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP; 1:1,000; cat. no. 2895T), and

anti-Na+/K+-ATPase [1:1,000; cat. no. 3010S;

all from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.]. Following washing three

times with TBST (TBS containing 0.1% Tween-20) for 10 min each

time, the membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies:

Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked antibody (cat. no. 7074) and anti-mouse

IgG, HRP-linked antibody (cat. no. 7076) (both 1:5,000; Cell

Signaling Technology, Inc.), for 1 h at room temperature. Protein

bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo

Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and band intensities were quantified

using ImageJ software (version 1.53t; National Institutes of

Health).

Insulin secretion assay

Supernatants of β-TC6 cells exposed to various

concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 mM) of PA for 24 h at 37˚C

were collected, and insulin levels were measured using a mouse

insulin ELISA kit [cat. no. 634-01481 (formerly AKRIN-011T)

FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation], according to the

manufacturer's instructions. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm, and

insulin concentrations were calculated using a standard curve.

Transfection

For the knockdown of ERp46, 1x106 cells

were seeded into a 6-well plate. A total of 50 pmol ERp46 small

interfering (siRNA) (sense, 5'-GUACUCGGUACGAGGUUAUTT-3' and

antisense, 5'-AUAACCUCGUACCGAGUACTT-3') or negative control siRNA

(sense, 5'-UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT-3' and antisense,

5'-ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT-3') were transfected using Lipofectamine

2000 (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), according to the

manufacturer's instructions (at 3˚C for 6 h; typically 5 µl reagent

per well in Opti-MEM). The transfection medium was then replaced

with DMEM containing 12% FBS, and cells were cultured for 24 h at

37˚C. The expression of ERp46 was detected using western blotting

and RT-qPCR.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad

Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Data are presented as the mean

± standard error of the mean from three to five independent

experiments, with each experiment including n=6 biological

replicates per group. Statistical comparisons between two groups

were performed using an unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test, and

multiple-group comparisons were analyzed using ANOVA followed by

Sidak's multiple-comparisons test. P<0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

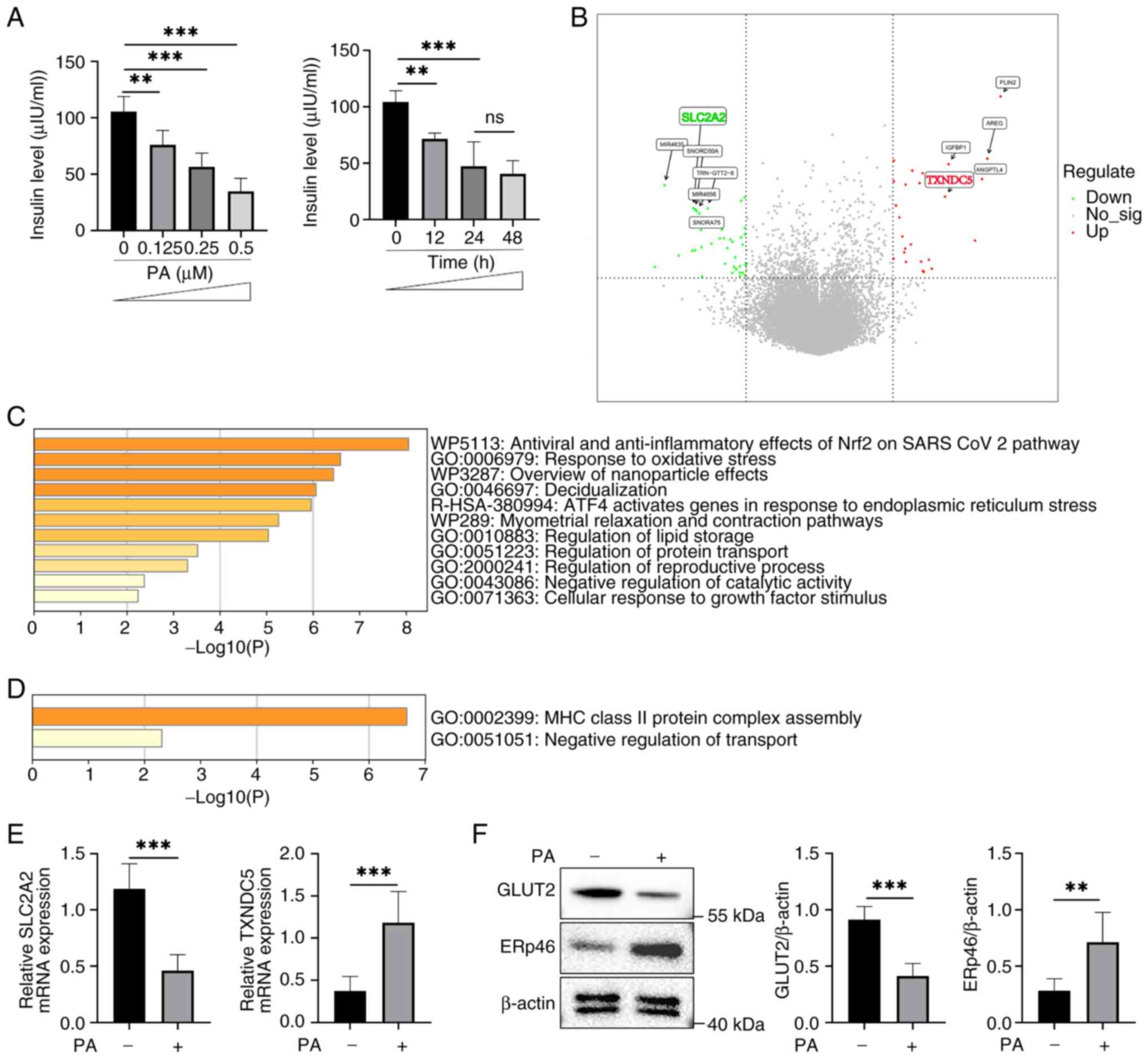

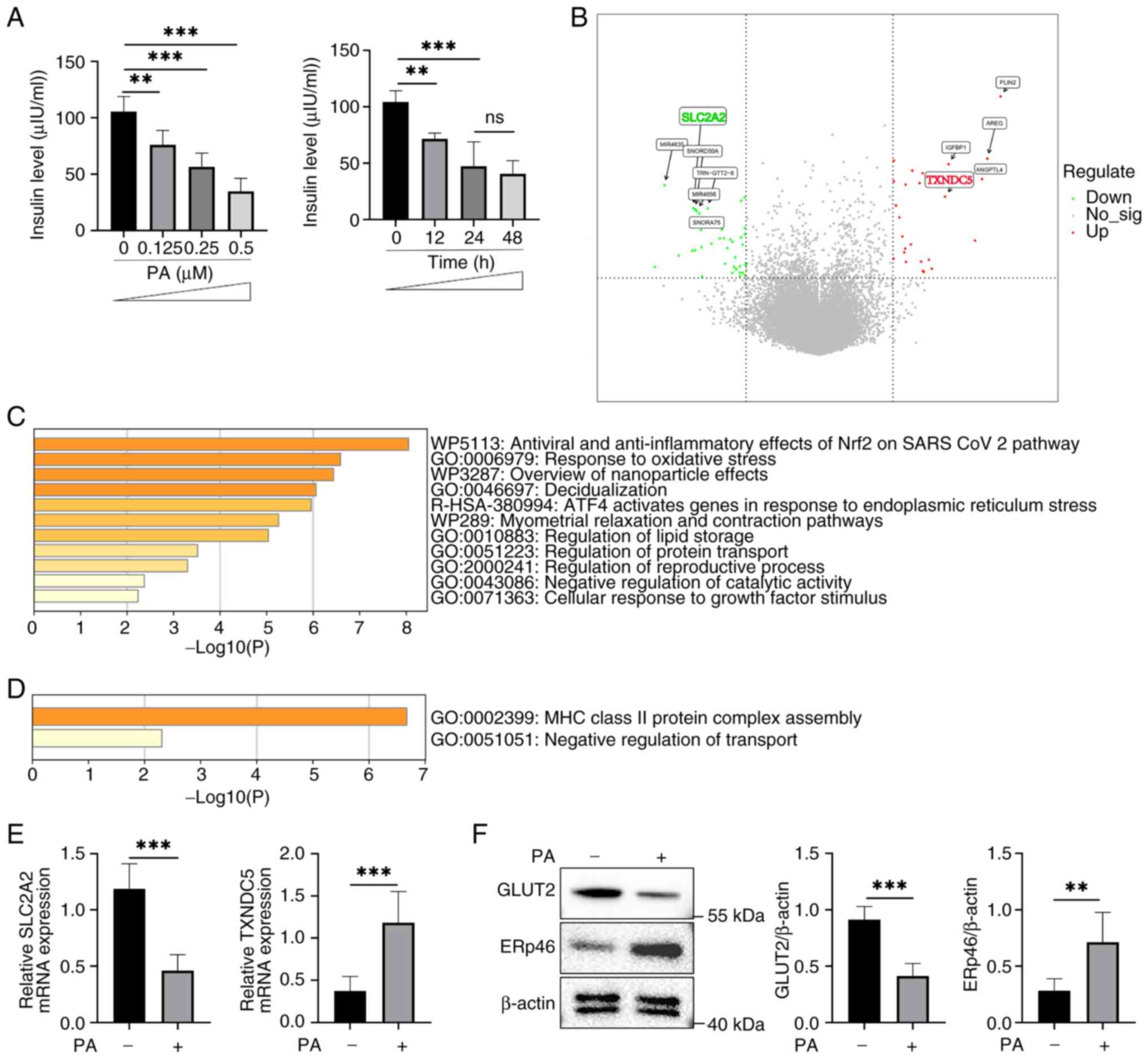

PA activates ER stress-related

pathways and impairs β-cell function

As aforementioned, FFAs can cause lipotoxicity in

pancreatic β-cells (10,15,19),

and it was found that following PA stimulation, pancreatic β-cells

secreted less insulin, which was proportionate to the dose of PA

(Fig. 1A), consistent with previous

studies (16,17). When stimulated with 0.5 µM PA,

insulin secretion decreased over time; however, there was no

significant difference between 24 and 48 h, suggesting that the

effect reached saturation (Fig.

1A). To further investigate the cause of the reduced insulin

secretion, RNA-seq analysis of a public dataset (GSE53949) was

performed. By analyzing the RNA-seq results of PA-stimulated

β-cells compared with the control group, TXNDC5 (gene name

of ERp46) was significantly upregulated (Fig. 1B). This upregulation was supported

by enrichment analysis, which highlighted the activation of ER

stress-related pathways in β-cells following PA stimulation

(Fig. 1C). These findings were

consistent with previous reports, in which the upregulation of

TXNDC5 was associated with its role in promoting correct protein

folding and maintaining redox homeostasis under ER stress

conditions (25-27).

| Figure 1PA-induced ER stress reduces GLUT2

expression and impairs insulin secretion in β-cells. (A) Insulin

secretion levels under varying concentrations of PA (0, 0.125, 0.25

and 0.5 µM) and at different time points (0, 12, 24 and 48 h).

Insulin secretion decreased in a dose- and time-dependent manner.

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM (n=6). Statistical

significance was determined using one-way ANOVA. (B) Volcano plot

showing the DEGs in PA-stimulated β-cells compared with controls.

TXNDC5 (ERp46) was significantly upregulated, whereas

SLC2A2 (GLUT2) was downregulated. (C) GO and KEGG pathway

enrichment of upregulated DEGs. Key pathways included oxidative

stress response, UPR and ER stress-related pathways. (D) Enrichment

analysis of downregulated DEGs, highlighting impaired transport

regulation and immune-related processes. (E) RT-qPCR validation of

TXNDC5 and SLC2A2 expression in PA-stimulated

β-cells. (F) Western blotting showing increased ERp46 and decreased

GLUT2 protein levels following PA treatment. **P<0.01

and ***P<0.001. PA, palmitic acid; ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; GLUT2, glucose transporter 2; SEM, standard error of the

mean; DEGs, differentially expressed genes; TXNDC5,

thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5; ERp46, endoplasmic

reticulum-resident protein 46; SLC2A2, solute carrier family

2 member 2; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes

and Genomes; UPR, unfolded protein response; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; ns, not significant. |

By contrast, the key glucose transporter

SLC2A2 (gene name of GLUT2) in β-cells was significantly

downregulated following PA stimulation. Enrichment analysis

identified the ‘negative regulation of transport’ pathway (Fig. 1D), highlighting the importance of

GLUT2 in β-cell function. The downregulation of GLUT2 suggested a

reduced glucose-transport capacity and was compatible with the

decreased insulin secretion observed in Fig. 1A. Previous studies have demonstrated

that GLUT2 plays a critical role in glucose sensing and insulin

secretion in β-cells (8,9), although the present data did not

directly establish causality. Consistently, RT-qPCR confirmed that

SLC2A2 mRNA was decreased while TXNDC5 mRNA was

increased in PA-treated cells (Fig.

1E). Western blotting further demonstrated decreased GLUT2

protein and increased ERp46 protein levels following PA treatment

(Fig. 1F). In conclusion, PA

stimulation was associated with the activation of ER stress-related

pathways and reduced GLUT2 expression and insulin secretion in

β-cells.

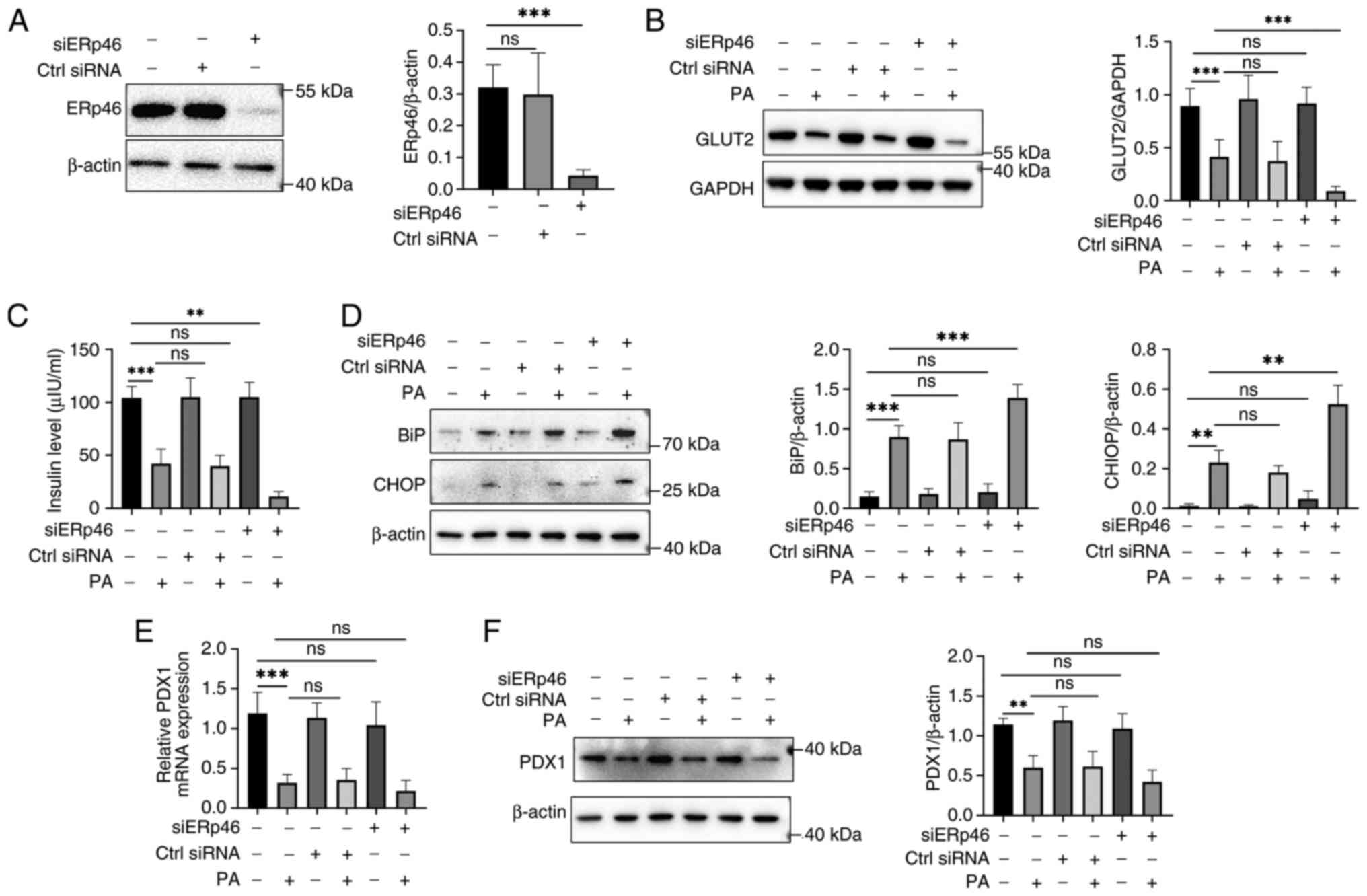

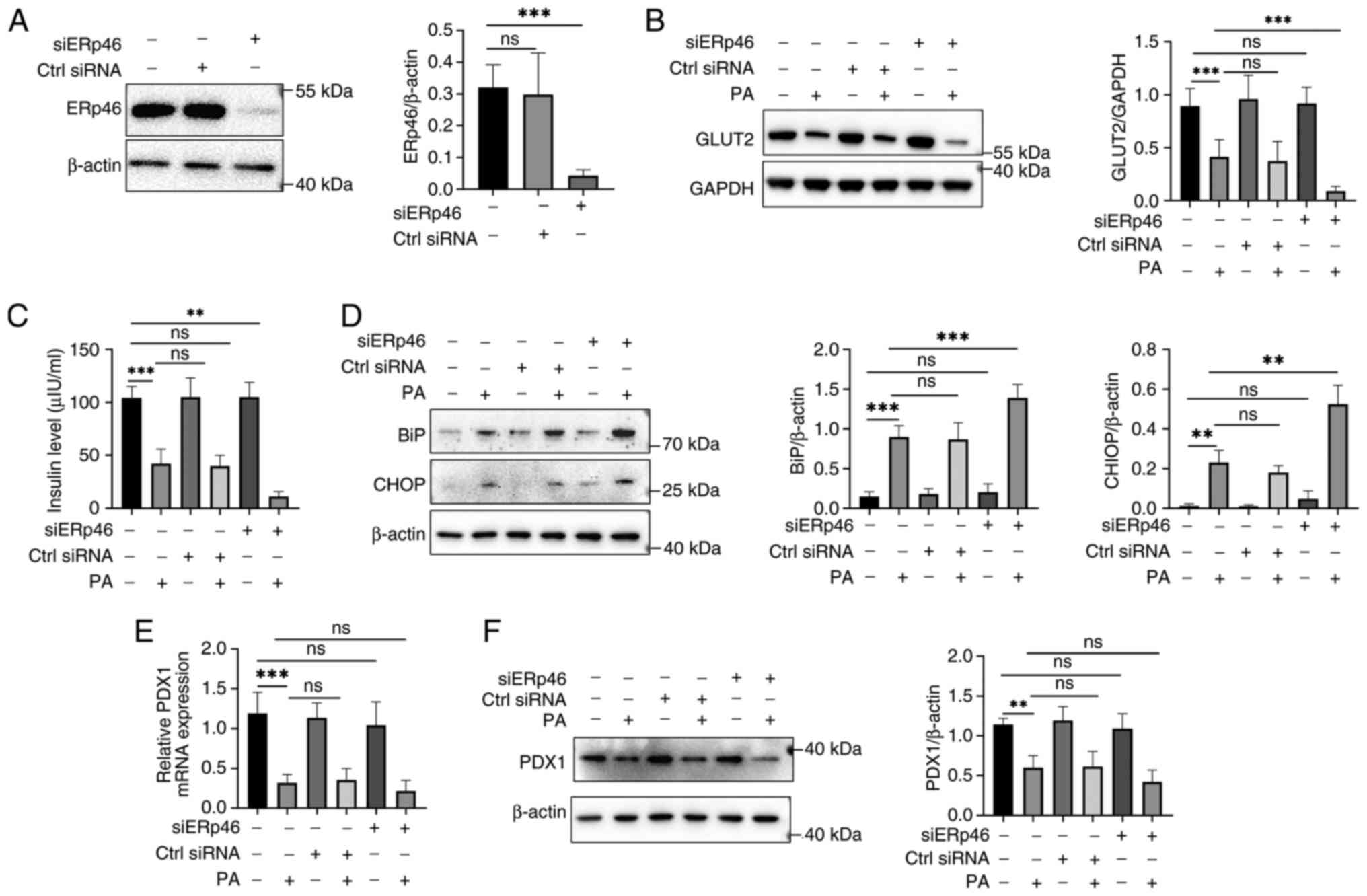

ERp46 depletion exacerbates PA-induced

ER stress, reducing GLUT2 expression and insulin secretion in

β-cells

ERp46 knockdown efficiency was first verified.

Western blotting confirmed a robust reduction of ERp46 protein

following siERp46 transfection (Fig.

2A). This result validated the effectiveness of the knockdown

system for subsequent experiments. Next, GLUT2 protein was examined

across the four conditions (Control, PA, siERp46 and PA + siERp46).

As shown in Fig. 2B, PA alone

decreased GLUT2, whereas siERp46 alone had no detectable effect. Of

note, the combination of siERp46 with PA further reduced GLUT2

compared with PA alone. These findings indicated that ERp46 is not

essential for basal GLUT2 expression, but contributes to the

maintenance of GLUT2 under lipotoxic stress.

| Figure 2ERp46 regulates GLUT2 expression and

insulin secretion in β-cells under PA-induced stress. (A) Western

blotting confirming ERp46 knockdown efficiency by siRNA

transfection. (B) Western blotting showing that GLUT2 expression

was further decreased in PA-treated cells following ERp46

knockdown. (C) Insulin secretion was significantly reduced in

ERp46-depleted β-cells exposed to PA, as determined by ELISA. (D)

Western blotting of ER stress markers BiP and CHOP revealed that

ERp46 knockdown aggravated PA-induced ER stress. (E) RT-qPCR

analysis of PDX1 mRNA expression showed no significant

changes with ERp46 knockdown under PA stimulation. (F) Western

blotting confirmed that PDX1 protein levels were not significantly

altered by ERp46 knockdown. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM

(n=6). Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA.

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ERp46,

endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein 46; GLUT2, glucose

transporter 2; PA, palmitic acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA; ER,

endoplasmic reticulum; BiP, binding immunoglobulin protein; CHOP,

C/EBP homologous protein; RT-qPCR, reverse

transcription-quantitative PCR; PDX1, pancreatic and

duodenal homeobox 1; SEM, standard error of the mean; ns, not

significant. |

Functionally, insulin secretion followed the same

pattern (Fig. 2C): PA reduced

insulin release; siERp46 alone did not alter secretion; and siERp46

plus PA led to a further decrease relative to PA alone. This

indicates that the protective role of ERp46 becomes evident only in

the presence of PA-induced stress. Since ERp46 is an ER

oxidoreductase, ER stress markers were assessed. PA increased BiP

and CHOP, and siERp46 further increased their levels under PA,

whereas siERp46 alone showed no significant change (Fig. 2D). These results are consistent with

the interpretation that ERp46 depletion aggravates ER stress in

β-cells exposed to PA. PDX1, a β-cell identity/functional factor

(12,30), was also evaluated. PA decreased PDX1

mRNA and protein levels, while siERp46 did not produce an

additional significant reduction beyond PA in our conditions

(Fig. 2E and F). This suggested that ERp46 depletion

primarily impacted GLUT2 and insulin secretion rather than β-cell

identity markers under PA stress.

Collectively, these data indicated that ERp46

depletion exacerbates PA-induced ER stress and is associated with a

greater loss of GLUT2 and insulin secretion, whereas ERp46

knockdown alone has minimal effects at baseline. Thus, ERp46

appears to play a stress-dependent protective role in sustaining

GLUT2 expression and β-cell functionality.

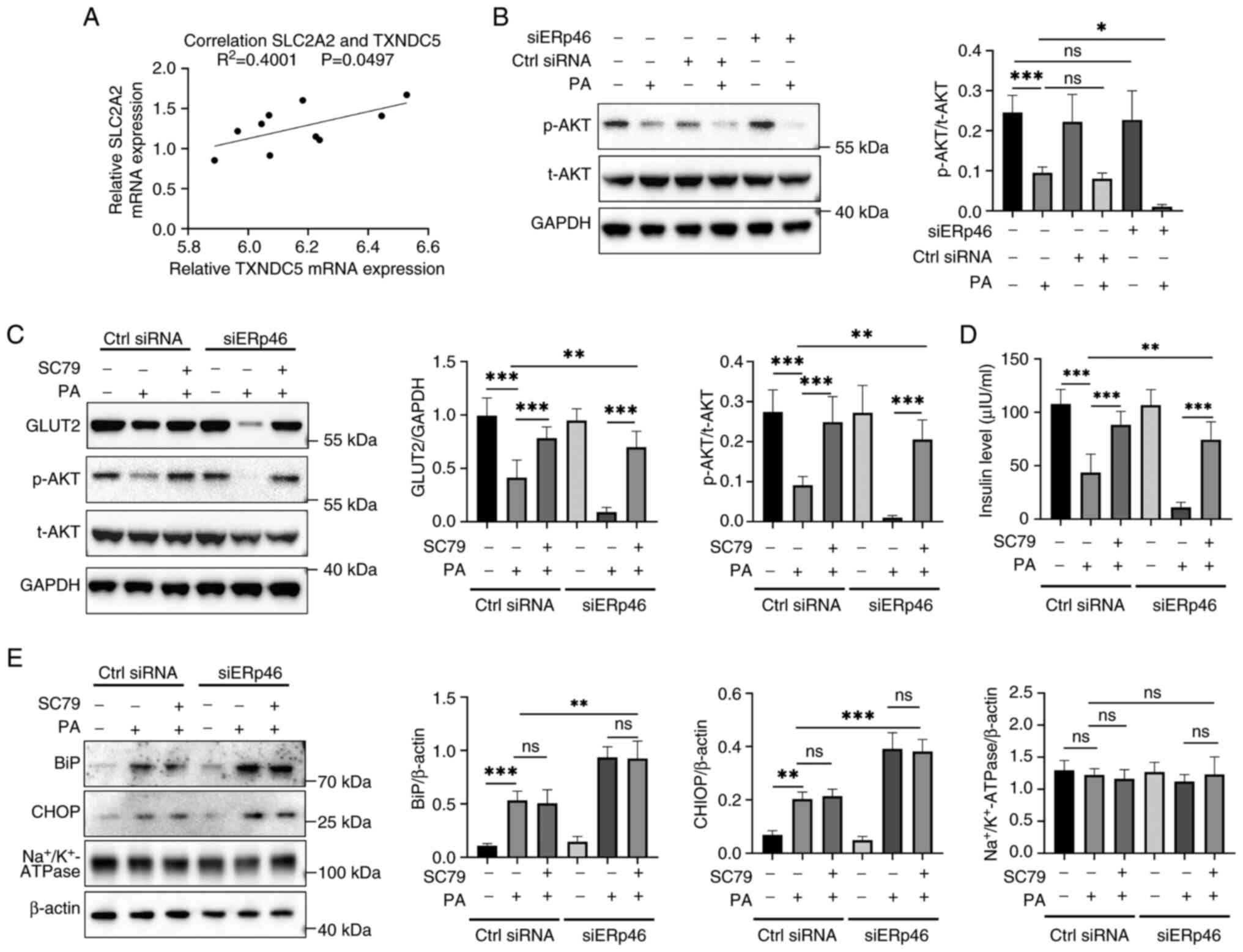

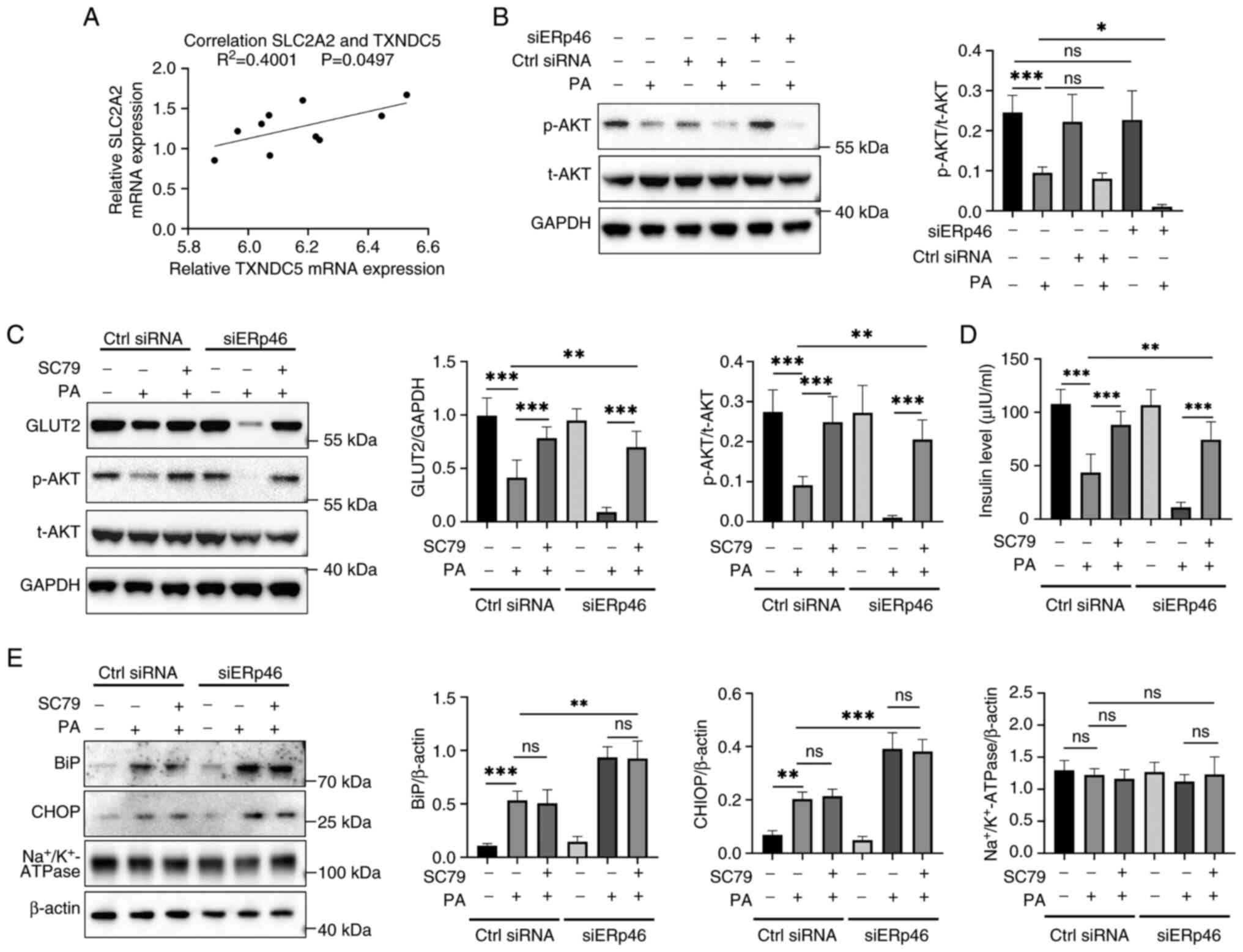

AKT signaling contributes to GLUT2

maintenance under PA-induced stress; ERp46 depletion reduces AKT

phosphorylation

The relationship between TXNDC5 (ERp46) and

SLC2A2 (GLUT2) was first examined using the public RNA-seq

dataset (GSE53949). In the correlation plot, each dot represents

one RNA-seq sample from GSE53949 (PA-stimulated or control β-cell

samples). A modest positive correlation was observed (R²=0.4001,

P=0.0497; Fig. 3A), supporting an

association between ERp46 and GLUT2 under lipotoxic conditions.

Next, AKT activation was assessed. Total AKT (t-AKT) remained

unchanged across groups, whereas PA decreased phosphorylated AKT

(p-AKT). Of note, siERp46 alone had little effect, but siERp46 in

the presence of PA further reduced p-AKT (Fig. 3B). These findings indicated that

ERp46 depletion exacerbated the PA-induced suppression of AKT

phosphorylation, while having a minimal impact under basal

conditions.

| Figure 3ERp46 regulates GLUT2 expression

through AKT activation under PA-induced stress. (A) Correlation

analysis of RNA-seq dataset (GSE53949) showing a positive

correlation between TXNDC5 (ERp46) and SLC2A2 (GLUT2)

expression in PA-stimulated and control β-cell samples. (B) Western

blotting showing that p-AKT levels were decreased by PA and further

reduced by ERp46 knockdown, while t-AKT remained unchanged. (C)

Western blotting demonstrating that treatment with the AKT

activator SC79 restored GLUT2 expression and p-AKT levels in

ERp46-depleted cells under PA stimulation. (D) ELISA assay showing

that SC79 treatment rescued insulin secretion impaired by ERp46

knockdown in PA-treated β-cells. (E) Western blotting of ER stress

markers BiP and CHOP revealed that SC79 treatment did not

significantly reverse PA-induced ER stress, indicating that AKT

activation specifically rescued GLUT2 and insulin secretion without

directly modulating ER stress. Na+/K+-ATPase

served as a membrane-protein specificity control. Data are

presented as the mean ± SEM (n=6). Statistical significance was

determined using one-way ANOVA. *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001. ERp46,

endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein 46; GLUT2, glucose

transporter 2; AKT, protein kinase B; PA, palmitic acid;

TXNDC5, thioredoxin domain-containing protein 5;

SLC2A2, solute carrier family 2 member 2; p-AKT,

phosphorylated AKT; t-AKT, total AKT; SC79, AKT activator compound

SC79; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; BiP, binding immunoglobulin

protein; CHOP, C/EBP homologous protein; SEM, standard error of the

mean; ns, not significant. |

To determine whether AKT activation is sufficient to

counteract the PA/siERp46 effects, cells were treated with the AKT

activator SC79. SC79 increased p-AKT and partially restored GLUT2

protein in PA-exposed cells under both control siRNA and siERp46

conditions (Fig. 3C). Functionally,

SC79 also improved insulin secretion that was reduced by PA and

further diminished by siERp46 (Fig.

3D). To evaluate specificity, an additional membrane protein

and ER-stress markers were probed.

Na+/K+-ATPase was selected as a

representative plasma membrane housekeeping protein whose

expression remains stable under metabolic or ER stress conditions,

serving as a control for nonspecific changes in membrane protein

abundance. Na+/K+-ATPase levels were

unchanged across treatments, and SC79 did not reduce PA-induced

increases of BiP or CHOP (Fig. 3E),

indicating that AKT activation does not broadly elevate membrane

proteins or alleviate ER stress but can still restore GLUT2 and

insulin secretion.

In conclusion, ERp46 depletion was demonstrated to

enhance the PA-induced loss of p-AKT, GLUT2 and insulin secretion,

while pharmacological AKT activation rescued GLUT2 and insulin

without reducing ER-stress markers. These findings supported a

model in which AKT acts downstream or in parallel to ER-stress

pathways, with ERp46 helping to preserve AKT activity and β-cell

function specifically under lipotoxic stress.

Discussion

The present study revealed the critical role of

ERp46 in regulating GLUT2 expression and insulin secretion in

pancreatic β-cells under PA-induced lipotoxic stress. These

findings demonstrated that ERp46 exerted a protective effect on

β-cell function, primarily by alleviating PA-induced ER stress,

which in turn helps sustain AKT phosphorylation and maintain GLUT2

expression. These observations suggested that AKT may act

downstream or in parallel to ER stress, rather than being directly

regulated by ERp46 under basal conditions. However, the possibility

that ERp46 may influence AKT signaling more directly through

effects on the folding or stability of upstream signaling

components cannot be excluded and should be further investigated.

The findings of the present study provide novel insights into the

molecular mechanisms underlying β-cell dysfunction in T2DM.

PA-induced ER stress is a well-known contributor to

β-cell dysfunction, leading to impaired insulin secretion and

increased cell death through mechanisms such as protein misfolding

and oxidative stress (23,30). Consistent with these observations,

the present study showed that PA stimulation significantly

decreased GLUT2 expression and insulin secretion in β-cells.

Previous studies have shown that ER stress disrupts glucose sensing

by reducing GLUT2 expression and impairing insulin granule

exocytosis (22,23). Furthermore, prolonged ER stress was

shown to contribute to β-cell apoptosis, further limiting insulin

secretion capacity (10,18). The chronic activation of the UPR has

been demonstrated to further promote β-cell apoptosis and

functional decline under lipotoxicity (10,34).

Of note, ERp46 expression was upregulated in response to PA,

suggesting a compensatory mechanism to counteract ER stress.

However, the knockdown of ERp46 further reduced GLUT2 expression

and exacerbated the decline in insulin secretion, highlighting its

protective role in maintaining β-cell functionality. As a member of

the protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) family, ERp46 is essential

for protein folding and redox homeostasis in the ER (6,12).

This is consistent with its reported ability to mitigate cellular

stress by ensuring proteostasis under adverse conditions.

Concordantly, multiple PDI paralogs (such as PDI family A member 1

(PDIA1)/pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component subunit beta and

ERp57/PDIA3 modulate β-cell stress adaptation and insulin

biosynthesis, underscoring a conserved ER proteostasis axis in the

endocrine pancreas (24,35). Previous studies have further

emphasized the role of ERp46 in alleviating ER stress and apoptosis

in β-cells under diabetic conditions (22,31),

suggesting its broader function in metabolic regulation. A recent

comprehensive review of TXNDC5/ERp46 across diseases also

highlighted its metabolic relevance and therapeutic tractability

(29).

In addition to its role in maintaining ER

homeostasis, ERp46 may influence GLUT2 expression, at least partly

through the modulation of the AKT signaling pathway. AKT activation

has been widely reported as a crucial regulator of glucose uptake

and insulin secretion in β-cells (30,36).

In the present study, PA stimulation significantly reduced p-AKT,

and this effect was further exacerbated by ERp46 knockdown,

suggesting that ERp46 supports AKT activation under lipotoxic

conditions, which in turn may help preserve GLUT2 expression.

Although total AKT levels remained unchanged across experimental

groups, PA stimulation significantly reduced p-AKT levels, and this

reduction was further exacerbated by ERp46 knockdown. This

suggested that ERp46 primarily sustains AKT phosphorylation

indirectly by alleviating ER stress, as siERp46 had no effect under

baseline conditions but markedly suppressed AKT activity in the

presence of PA. Thus, AKT is more likely to act downstream or in

parallel to ER stress rather than being directly controlled by

ERp46. Of note, treatment with SC79, a direct AKT activator,

successfully rescued GLUT2 expression and restored insulin

secretion in ERp46-depleted cells. This is consistent with broader

evidence that phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling is a

central survival and metabolic pathway in β-cells and a candidate

lever to counter lipotoxic dysfunction (37,38).

These findings provided direct evidence that ERp46 supports GLUT2

expression and β-cell functionality by modulating AKT

activation.

UPR signaling has been reported to intersect with

AKT activity in other cellular contexts. For example, PERK-eIF2α

signaling can suppress insulin biosynthesis, whereas adaptive

inositol-requiring enzyme 1-X-box binding protein 1 and activating

transcription factor 6 branches promote β-cell survival and

proteostasis (39,40). Additional studies have suggested

that maladaptive ER stress can impair AKT phosphorylation, while

protective UPR responses may sustain it (41,42).

Although these findings indicated potential crosstalk between UPR

and AKT, whether this mechanism operates in β-cells under lipotoxic

stress remains uncertain. The present data that ERp46 depletion

reduces p-AKT under PA stress raise the possibility that ERp46 may

act by stabilizing ER proteostasis, thereby preventing maladaptive

UPR activation and indirectly supporting AKT activity.

Nevertheless, the alternative hypothesis that ERp46 may also

regulate AKT through more direct mechanisms, cannot be

excluded.

The positive correlation between ERp46 and GLUT2

highlights the importance of maintaining ER homeostasis in

preserving β-cell function under lipotoxic stress. Furthermore, the

ability of AKT activation to mitigate the negative effects of ERp46

depletion suggests that targeting the ERp46-AKT-GLUT2 axis could

offer a therapeutic strategy for improving β-cell survival and

insulin secretion in T2DM. In parallel, interventions that lower ER

stress, such as chemical chaperones or UPR modulators, have

demonstrated the protection of β-cell mass and function in

preclinical models and early translational studies (43-46),

supporting an ‘ER-proteostasis-first’ approach that aligned with

the present model. These findings supported the rationale that

enhancing ERp46 activity may represent a novel strategy to

stabilize β-cell proteostasis and insulin secretory function.

Beyond diabetes, ER stress is a convergent mechanism

in multiple chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease,

neurodegeneration and cancer (40,47-50).

Placing these results in this broader context underscores the

translational significance of modulating ER proteostasis; targeting

ERp46 or allied PDI nodes could complement metabolic therapies and

potentially benefit co-morbid conditions characterized by secretory

stress. Of note, the spleen has recently been recognized as an

active immunometabolic hub that communicates with the gut and liver

to shape lipid and glucose metabolism, as well as systemic

inflammation, forming distinct spleen-organ axes (51). In addition, in a

high-fat/streptozotocin rat model with splenectomy, adipose

tissue-derived stem cells protected against T2D through the

induction of spleen-derived IL-10; this benefit was blunted by

splenectomy, highlighting a spleen-IL-10 anti-inflammatory circuit

with a metabolic impact (52). An

independent study further showed that spleen-derived or exogenous

IL-10 can dampen obesity-associated inflammation and insulin

resistance in liver and adipose tissues (53). Of note, IL-10 has also been

demonstrated to alleviate ER stress and apoptosis in non-islet

tissues, such as cardiomyocytes under doxorubicin challenge

(54) and skeletal muscle of aged

mice (55). These findings

suggested that splenic IL-10-driven anti-inflammatory circuits

could, in principle, buffer β-cell ER stress and indirectly

preserve AKT phosphorylation and GLUT2 expression, consistent with

our ERp46-proteostasis model.

Despite these insights, the precise mechanisms

through which ERp46 regulates AKT activation remain to be fully

elucidated. It is possible that ERp46 interacts directly with

components of the PI3K/AKT pathway, but it is also plausible that

the effects are mediated indirectly through ER stress and UPR

signaling. Further studies are warranted to dissect these molecular

interactions and to explore the in vivo role of ERp46,

particularly in diabetic animal models. In addition, complementary

approaches such as conditional β-cell-specific ERp46-knockout

models or the pharmacological modulation of ER stress may provide

more definitive evidence. In addition, the involvement of other ER

stress-related pathways in regulating GLUT2 expression and insulin

secretion deserves further investigation. Collectively, these

findings not only enhanced our understanding of β-cell dysfunction

under lipotoxic stress but also underscored the potential of ERp46

as a promising therapeutic target for diabetes and possibly other

ER stress-related diseases.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that

ERp46 is a key regulator of GLUT2 expression and insulin secretion

in β-cells under lipotoxic stress. Rather than directly activating

AKT, ERp46 primarily alleviated PA-induced ER stress, which in turn

supported AKT phosphorylation and helped preserve GLUT2 expression.

These findings provided a mechanistic basis for the development of

therapeutic strategies targeting ER stress modulators in

combination with ERp46- and AKT-related pathways to combat β-cell

dysfunction in T2DM.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Zhongshan Hospital

of Xiamen University (Xiamen, China) for providing laboratory

facilities and technical support.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Guidance Project

of Xiamen Science and Technology Bureau (grant no.

3502Z20189038).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

DC acquired the funding and contributed to the

conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation,

methodology, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. CH

contributed to the conceptualization, investigation, methodology,

project administration, supervision and manuscript revision. XC

contributed to the investigation, data curation and formal

analysis. YT and KW contributed to data curation and formal

analysis. DC and CH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Heald AH, Stedman M, Davies M, Livingston

M, Alshames R, Lunt M, Rayman G and Gadsby R: Estimating life years

lost to diabetes: Outcomes from analysis of National diabetes audit

and office of National statistics data. Cardiovasc Endocrinol

Metab. 9:183–185. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M,

Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, Stein C, Basit A, Chan JCN, Mbanya JC, et

al: IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes

prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes

Res Clin Pract. 183(109119)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Saeedi P, Petersohn I, Salpea P, Malanda

B, Karuranga S, Unwin N, Colagiuri S, Guariguata L, Motala AA,

Ogurtsova K, et al: Global and regional diabetes prevalence

estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from

the International diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9th edition.

Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 157(107843)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Piché ME, Tchernof A and Després JP:

Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ

Res. 126:1477–1500. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Eizirik DL, Pasquali L and Cnop M:

Pancreatic β-cells in type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus: Different

pathways to failure. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 16:349–362.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Thorens B: GLUT2, glucose sensing and

glucose homeostasis. Diabetologia. 58:221–232. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Mueckler M and Thorens B: The SLC2 (GLUT)

family of membrane transporters. Mol Aspects Med. 34:121–138.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Thorens B, Guillam MT, Beermann F,

Burcelin R and Jaquet M: Transgenic reexpression of GLUT1 or GLUT2

in pancreatic beta cells rescues GLUT2-null mice from early death

and restores normal glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol

Chem. 275:23751–23758. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Guillam MT, Dupraz P and Thorens B:

Glucose uptake, utilization, and signaling in GLUT2-null islets.

Diabetes. 49:1485–1491. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Lytrivi M, Castell AL, Poitout V and Cnop

M: Recent insights into mechanisms of β-cell lipo- and

glucolipotoxicity in type 2 diabetes. J Mol Biol. 432:1514–1534.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Prentki M, Peyot ML, Masiello P and

Madiraju SRM: Nutrient-induced metabolic stress, adaptation,

detoxification, and toxicity in the pancreatic β-cell. Diabetes.

69:279–290. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Ashcroft FM and Rorsman P: Diabetes

mellitus and the β cell: The last ten years. Cell. 148:1160–1171.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Xie T, So WY, Li XY and Leung PS:

Fibroblast growth factor 21 protects against lipotoxicity-induced

pancreatic β-cell dysfunction via regulation of AMPK signaling and

lipid metabolism. Clin Sci (Lond. 133:2029–2044. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Biden TJ, Robinson D, Cordery D, Hughes WE

and Busch AK: Chronic effects of fatty acids on pancreatic

beta-cell function: New insights from functional genomics.

Diabetes. 53 (Suppl 1):S159–S165. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Cnop M: Fatty acids and glucolipotoxicity

in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Biochem Soc Trans.

36:348–352. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Barlow J, Jensen VH, Jastroch M and

Affourtit C: Palmitate-induced impairment of glucose-stimulated

insulin secretion precedes mitochondrial dysfunction in mouse

pancreatic islets. Biochem J. 473:487–496. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Manukyan L, Ubhayasekera SJ, Bergquist J,

Sargsyan E and Bergsten P: Palmitate-induced impairments of β-cell

function are linked with generation of specific ceramide species

via acylation of sphingosine. Endocrinology. 156:802–812.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Cnop M, Foufelle F and Velloso LA:

Endoplasmic reticulum stress, obesity and diabetes. Trends Mol Med.

18:59–68. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

El-Assaad W, Buteau J, Peyot ML, Nolan C,

Roduit R, Hardy S, Joly E, Dbaibo G, Rosenberg L and Prentki M:

Saturated fatty acids synergize with elevated glucose to cause

pancreatic beta-cell death. Endocrinology. 144:4154–4163.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Wang XY, Zhu BR, Jia Q, Li YM, Wang T and

Wang HY: Cinnamtannin D1 protects pancreatic β-cells from

glucolipotoxicity-induced apoptosis by enhancement of autophagy in

vitro and in vivo. J Agric Food Chem. 68:12617–12630.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Omar-Hmeadi M and Idevall-Hagren O:

Insulin granule biogenesis and exocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci.

78:1957–1970. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Back SH, Kang SW, Han J and Chung HT:

Endoplasmic reticulum stress in the β-cell pathogenesis of type 2

diabetes. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012(618396)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Eizirik DL, Cardozo AK and Cnop M: The

role for endoplasmic reticulum stress in diabetes mellitus. Endocr

Rev. 29:42–61. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Lee JH and Lee J: Endoplasmic reticulum

(ER) stress and its role in pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and

senescence in type 2 diabetes. Int J Mol Sci.

23(4843)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hung CT, Tsai YW, Wu YS, Yeh CF and Yang

KC: The novel role of ER protein TXNDC5 in the pathogenesis of

organ fibrosis: mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications.

J Biomed Sci. 29(63)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang X, Li H and Chang X: The role and

mechanism of TXNDC5 in diseases. Eur J Med Res.

27(145)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Okumura M, Kadokura H and Inaba K:

Structures and functions of protein disulfide isomerase family

members involved in proteostasis in the endoplasmic reticulum. Free

Radic Biol Med. 83:314–322. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Duivenvoorden WCM, Hopmans SN, Austin RC

and Pinthus JH: Endoplasmic reticulum protein ERp46 in prostate

adenocarcinoma. Oncol Lett. 13:3624–3630. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bidooki SH, Navarro MA, Fernandes SCM and

Osada J: Thioredoxin domain containing 5 (TXNDC5): Friend or Foe?

Curr Issues Mol Biol. 46:3134–3163. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Rutter GA, Pullen TJ, Hodson DJ and

Martinez-Sanchez A: Pancreatic β-cell identity, glucose sensing and

the control of insulin secretion. Biochem J. 466:203–218.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Lampropoulou E, Lymperopoulou A and

Charonis A: Reduced expression of ERp46 under diabetic conditions

in β-cells and the effect of liraglutide. Metabolism. 65:7–15.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Cnop M, Abdulkarim B, Bottu G, Cunha DA,

Cunha DA, Igoillo-Esteve M, Masini M, Turatsinze JV, Griebel T,

Villate O, Santin I, et al: RNA sequencing identifies dysregulation

of the human pancreatic islet transcriptome by the saturated fatty

acid palmitate. Diabetes. 63:1978–1993. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Livak KJ and Schmittgen TD: Analysis of

relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and

the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25:402–408.

2001.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Chen CW, Guan BJ, Alzahrani MR, Gao Z, Gao

L, Bracey S, Wu J, Mbow CA, Jobava R, Haataja L, et al: Adaptation

to chronic ER stress enforces pancreatic β-cell plasticity. Nat

Commun. 13(4621)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Jiang H, Thapa P, Hao Y, Ding N,

Alshahrani A and Wei Q: Protein disulfide isomerases function as

the missing link between diabetes and cancer. Antioxid Redox

Signal. 37 (16-18):1191–1205. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Taniguchi CM, Emanuelli B and Kahn CR:

Critical nodes in signalling pathways: Insights into insulin

action. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 7:85–96. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Camaya I, Donnelly S and O'Brien B:

Targeting the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in pancreatic β-cells to

enhance their survival and function: An emerging therapeutic

strategy for type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes. 14:247–260.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Dalle S and Abderrahmani A: Receptors and

signaling pathways controlling beta-cell function and survival as

targets for anti-diabetic therapeutic strategies. Cells.

13(1244)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Back SH and Kaufman RJ: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress and type 2 diabetes. Annu Rev Biochem. 81:767–793.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hetz C and Papa FR: The unfolded protein

response and cell fate control. Mol Cell. 69:169–181.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Sano R and Reed JC: ER stress-induced cell

death mechanisms. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1833:3460–3470.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Hetz C, Zhang K and Kaufman RJ:

Mechanisms, regulation and functions of the unfolded protein

response. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:421–438. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, Furuhashi M,

Vaillancourt E, Smith RO, Görgün CZ and Hotamisligil GS: Chemical

chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a

mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 313:1137–1140.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Gao Y, Ryu H, Lee H, Kim YJ, Lee JH and

Lee J: ER stress and unfolded protein response (UPR) signaling

modulate GLP-1 receptor signaling in the pancreatic islets. Mol

Cells. 47(100004)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Xing D, Zhou Q, Wang Y and Xu J: Effects

of tauroursodeoxycholic acid and 4-phenylbutyric acid on selenium

distribution in mice model with type 1 diabetes. Biol Trace Elem

Res. 201:1205–1213. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Yong J, Johnson JD, Arvan P, Han J and

Kaufman RJ: Therapeutic opportunities for pancreatic β-cell ER

stress in diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 17:455–467.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Ron D and Walter P: Signal integration in

the endoplasmic reticulum unfolded protein response. Nat Rev Mol

Cell Biol. 8:519–529. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Celik C, Lee SYT, Yap WS and Thibault G:

Endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipids in health and diseases.

Prog Lipid Res. 89(101198)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Chen X and Cubillos-Ruiz JR: Endoplasmic

reticulum stress signals in the tumour and its microenvironment.

Nat Rev Cancer. 21:71–88. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Ren J, Bi Y, Sowers JR, Hetz C and Zhang

Y: Endoplasmic reticulum stress and unfolded protein response in

cardiovascular diseases. Nat Rev Cardiol. 18:499–521.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Tarantino G and Citro V: Crosstalk between

the spleen and other organs/systems: Downstream signaling events.

Immuno. 4:479–501. 2024.

|

|

52

|

Zhang J, Deng Z, Jin L, Yang C, Liu J,

Song H, Han W and Si Y: Spleen-derived anti-inflammatory cytokine

IL-10 stimulated by adipose tissue-derived stem cells protects

against type 2 diabetes. Stem Cells Dev. 26:1749–1758.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Gotoh K, Inoue M, Masaki T, Chiba S,

Shimasaki T, Ando H, Fujiwara K, Katsuragi I, Kakuma T, Seike M, et

al: A novel anti-inflammatory role for spleen-derived

interleukin-10 in obesity-induced inflammation in white adipose

tissue and liver. Diabetes. 61:1994–2003. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Malik A, Bagchi AK, Jassal DS and Singal

PK: Interleukin-10 mitigates doxorubicin-induced endoplasmic

reticulum stress as well as cardiomyopathy. Biomedicines.

10(890)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Marafon BB, Pinto AP, de Sousa Neto IV, da

Luz CM, Pauli JR, Cintra DE, Ropelle ER, Simabuco FM, Pereira de

Moura L, de Freitas EC, et al: The role of interleukin-10 in

mitigating endoplasmic reticulum stress in aged mice through

exercise. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 327:E384–E395.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|