Introduction

Heart failure (HF), a progressive clinical syndrome,

is characterized by impaired cardiac output and/or elevated

intracardiac pressure, resulting in systemic hypoperfusion and

congestion (1). It encompasses a

broad spectrum of hemodynamic and structural abnormalities,

frequently associated with the dysregulation of neurohormonal

pathways, particularly the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

(RAAS) and the sympathetic nervous system (2). The incidence of HF is increasing,

causing an escalating burden on healthcare systems (3). In a population-based study from Spain

in 2012, 30.8% of patients with heart failure were hospitalized

within one year of follow-up, and the all-cause mortality rate

during that period was 14.3% (4).

In the United States, it is one of the most costly medical

disorders, with a total annual cost of $30.7 billion (5).

The classification of HF based on ejection fraction

(EF) has advanced to support more precise therapeutic decisions. HF

is classified on the basis of the left ventricular EF (LVEF) into

reduced (HFrEF, ≤40%), mildly reduced (HFmrEF, 41-49%), preserved

(HFpEF, ≥50%), and improved ejection fraction (HFimpEF), defined as

a baseline LVEF of <40% with an increase of ≥10 percentage

points to >40% on follow-up (6).

This classification based on LVEF, is currently endorsed by the

2021 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines on Heart

Failure. This is a positive change compared with the 2016 ESC

Guidelines, which reassigned patients with an exact LVEF of 40% to

HFrEF rather than HFmrEF, and improves alignment between management

strategies and clinical trial evidence (7).

The revised classification has informed contemporary

treatment guidelines, particularly regarding the use of angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs). The 2022 the American Heart

Association/American College of Cardiology/Heart Failure Society of

America (HFSA) Guideline for the Management of HF recommend

replacing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) or

angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) with ARNIs, including

sacubitril/valsartan, in patients with symptomatic HFrEF (New York

Heart Association classes II-III) and initiating ARNI therapy

before discharge in patients hospitalized with acute HF.

Furthermore, to decrease the risk of hospitalization, ARNIs may be

considered in select patients with HFmrEF or HFpEF (1). Previous landmark trials, including

PARADIGM-HF and PARAGON-HF, have demonstrated the superiority of

ARNIs by achieving a substantial decrease in

cardiovascular-associated mortality, HF-related hospitalization and

complication rates compared with the use of either ACE-Is or ARBs

alone (8,9).

In parallel with advancements in neurohormonal

modulation therapies such as ARNI, diuretic strategies remain a key

component in the symptomatic management of congestive HF,

particularly in patients presenting with volume overload. Recently,

interest has grown in combinatorial diuretic regimens to overcome

diuretic resistance and improve decongestive outcomes (10-12).

A meta-analysis by Duta et al (10) demonstrated that the combination of

acetazolamide with loop diuretics significantly enhances

natriuresis and fluid removal compared with loop diuretics alone.

This approach targets both proximal and distal renal tubular sites,

optimizing diuretic response and offering promising adjunctive

benefits in acute and chronic HF settings (10). Incorporating evolving strategies

into the broader HF treatment paradigm reflects the growing

recognition of the need for individualized, phenotype-based

interventions beyond guideline-directed medical therapy.

Although prior meta-analyses have demonstrated the

clinical benefits of ARNIs, particularly in decreasing mortality,

hospitalization and improving functional outcomes, these have

primarily focused on patients with rEF, with limited exploration of

its effects across the full spectrum of HF phenotypes (13,14).

The generalizability is further limited by the heterogeneity in

study populations, outcome definitions and reporting standards.

Therefore, the present systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to

evaluate the efficacy, safety and BP-associated outcomes of ARNIs

across populations with HFrEF, HFmrEF and HFpEF while accounting

for key clinical modifiers, including age, sex, anthropometric

profile, laboratory parameters, hemodynamic factors and cardiac and

renal function. By integrating a large body of evidence and

applying meta-regression to key hemodynamic and renal parameters,

the present study aimed to offer clinically relevant insights to

inform more individualized and hypertension-conscious HF

management.

Materials and methods

Study design and protocol

registration

The present systematic review and meta-analysis

followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and

Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines (15). The study protocol was registered in

the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with

registration no. CRD42024569374 (crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024569374).

Search strategies

A systematic search of the relevant studies was

conducted across five databases, including PubMed (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/), Cochrane (https://www.cochranelibrary.com/), ProQuest

(https://www.proquest.com/) and Google

Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/).

Databases were searched from inception to July 7, 2025; data

extraction and all derived estimations were completed on July 29,

2025, after which no additional updates were incorporated. The

following main keywords, combined with Boolean operators ‘AND’ and

‘OR’, were initially established: (‘Angiotensin Receptor Neprilysin

Inhibitor’ OR ‘ARNI’ OR ‘Sacubitril/Valsartan’ OR ‘LCZ696’ OR

‘Entresto’) AND (‘Heart Failure’ OR ‘Congestive Heart Failure’ OR

‘CHF’ OR ‘Cardiac Insufficiency’ OR ‘Left Ventricular Dysfunction’)

AND (‘Reduced Ejection Fraction’ OR ‘Reduced EF’ OR ‘HfrEF’ OR

‘Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction’ OR ‘Systolic Heart

Failure’) AND (‘Preserved Ejection Fraction’ OR ‘Preserved EF’ OR

‘HfpEF’ OR ‘Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction’ OR

‘Diastolic Heart Failure’). No publication date and language

restrictions were set.

Selection of studies

The search results from each database were collected

and managed using Google Sheets (Google LLC). After removing

duplicates, the remaining articles were screened based on title and

abstract. Full-text studies that were available and published were

assessed according to the pre-specified eligibility criteria by

four investigators. Any disagreements were resolved through a group

discussion.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Wrong study

design (single-arm or non-comparative reports); ii) wrong

population (not chronic HF); iii) wrong comparator (not ACE-I/ARB

or guideline-directed therapy); iv) wrong outcomes (no extractable

data for prespecified endpoints); and v) overlapping populations

(for multiple publications from the same trial, the most complete

primary report was retained). When outcome data were unavailable,

author contact was attempted; studies with unresolved missing data

were excluded from quantitative synthesis.

Eligibility criteria

Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome (PICO)

framework (Table SI) designed for

systematic reviews was used to establish the eligibility criteria

as follows: i) Study population consisted of patient with various

stages of EF HF (HFmEF, HFpEF, HFrEF); ii) used ARNI as

intervention; iii) used ACE-I/ARB as control therapy; iv) evaluated

efficacy [all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality, major

adverse cardiac events (MACE) and HF hospitalization] and safety

(hypotension, hyperkalemia, angioedema and renal impairment); and

v) randomized control trial design. Exclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Title or abstract was irrelevant; ii) full-text was

irretrievable and iii) the study was a review article, case report,

case series or conference abstract. Titles or abstracts were

considered irrelevant if they did not pertain to the predefined

PICO framework.

Data extraction

A total of two investigators extracted data from

each included study. The data extracted included the first author

and year of publication, study location (country), HF type, age,

sample size, sex (% of males), type of intervention and control

(drug administration and dosing regimens), follow-up duration

(months), efficacy (all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality,

MACEs and HF-related hospitalization), and safety (hypotension,

hyperkalemia, angioedema and renal impairment). Adverse events

(AEs) were classified using the Common Terminology Criteria for AEs

(CTCAE) developed by developed by the US National Cancer Institute

of the National Institute of Health, with severity graded from 1

(mild) to 5 (death) (16).

Quality assessment of individual

studies

To evaluate the risk of bias of each eligible study,

two investigators independently conducted a methodological quality

assessment using the Cochrane Collaboration's Risk of Bias 2 (RoB

2) tool (17). The RoB 2 is a

revised tool comprising five bias domains designed to consider the

risk of bias of randomized trials arising from the randomization

process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome

data, outcome measurement and selecting the reported results. The

risk of bias on each domain was rated as low or high risk, or some

concerns (unclear). A study was considered to have a low risk of

bias when all domains exhibited low risk. A study was judged to

have some concerns when at least one domain was rated unclear. A

study was considered to be at a high risk of bias when at least one

domain presented a high risk or some concerns in multiple domains

that may lower the confidence in the results.

Statistical analysis

The present study performed a meta-analysis with

fixed- or DerSimonian-Laird random effect to compute the risk ratio

(RR) for all dichotomous outcomes using Review Manager version 5.4

(The Cochrane Collaboration), STATA version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC)

and meta package in RStudio version 4.4.1 (Posit PBC). The data are

presented as RR and 95% confidence interval. A random effect was

used when heterogeneity was detected (I2>50%).

Heterogeneity was assessed using Higgins' I² statistic. To

interpret the degree of heterogeneity, I² values of 0, 1-24, 25-49,

50-74 and ≥75% were considered to indicate no, very low, low,

moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively (18). P<0.05 was considered to indicate

a statistically significant difference.

Subgroup analyses and meta-regression were performed

to explore heterogeneity. Subgroups were prespecified by LVEF ≤40%

vs. >40%, with pooled effects estimated within strata and

between-group differences assessed using an interaction P-value.

Meta-regression employed the DerSimonian-Laird random-effects

approach to evaluate continuous study-level covariates, including

mean age, proportion of female patients, N-terminal pro-B-type

natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), LVEF, heart rate, systolic (S)BP,

body mass index (BMI) and renal impairment as estimated by

glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Where the same construct

appeared in both frameworks, it was modeled categorically in

subgroup analyses and continuously in meta-regression.

Funnel plots were constructed for each outcome. For

outcomes with ≥10 studies, Egger's regression test (primary) and

Begg's rank-correlation test (sensitivity) were performed, using

α=0.10 (two-sided) to flag potential asymmetry; outcomes with

<10 studies were not tested.

Results

Study selection and

identification

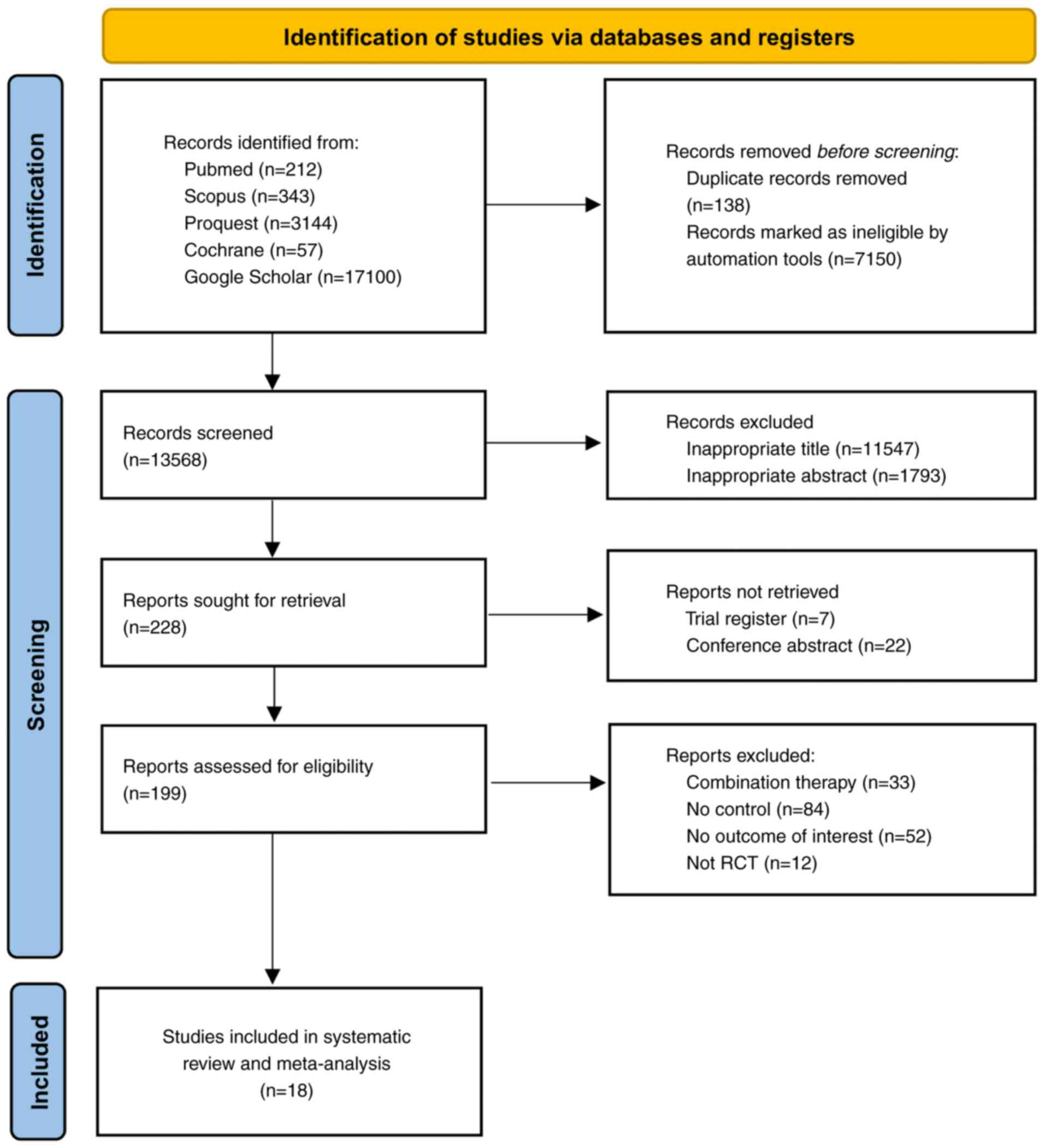

The initial database search yielded 20,856 studies.

Before screening, 7,288 articles were removed, including 138

duplicates and 7,150 identified as ineligible. Following the title

and abstract screening, 13,340 articles were excluded. A total of

228 articles were assessed for retrieval, with 29 removed. The

remaining 199 articles underwent eligibility assessment, leading to

the inclusion of 18 studies for quantitative and qualitative

analyses (8,9,19-34).

The PRISMA flowchart detailing the study selection process is

depicted in Fig. 1.

Characteristics of the included

studies

A total of 18 RCTs were eligible for inclusion in

the analysis, involving 28,001 HF patients from nine studies

conducted in the United States (9,19-21,27,28,31,33,34),

one each from the United Kingdom (8), Canada (28), Italy (29), South Korea (25), Japan (32) and Bangladesh (23) and two each from Germany (24,30)

and China (22,26) (Table

I). The mean patient age was 59.4-72.8 years, with most

participants being male (64.18%). The patient population comprised

individuals with three types of HF, categorized by LVEF: Preserved

(six studies) (9,20,28,30,31,34),

mildly reduced (one study) (30)

and reduced (12 studies) (8,19,21-27,27,32,33),.

A total of 13,876 patients received ARNI intervention, with doses

of 50, 100 and 200 mg, taken twice daily. Conversely, 14,125

patients received control treatments, consisting of ARB in 10

studies (6,704 patients) (9,20,22,23,26-28,30,31,33)

and ACE-I in eight studies (7,204 patients) (8,19,21,24,26,29,32,33).

The follow-up time ranged from 2 to 36 months. The most frequently

reported CTCAE-graded AEs were hypotension, worsening renal

function, hyperkalemia, angioedema and acute kidney injury.

| Table ICharacteristics of studies. |

Table I

Characteristics of studies.

| | Control | Intervention | |

|---|

| First author,

year | Country | Number of

patients | Male patients

(%) | Mean age,

years | Type of HF | Type | n | Type | n | Follow-up duration,

months | CTCAE (grade) | (Refs.) |

|---|

| McMurray et

al, 2014 | United Kingdom | 8,399 | 6,567 (78.2) | 63.80±11.40 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 200 mg twice

daily | 4,187 | Enalapril, 10 mg

twice daily | 4,212 | 4 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), symptomatic hypotension

(G2-3), angioedema (G2-3), hospitalization (G3-4),

cardiovascular-associated mortality (G5) | (8) |

| Solomon et

al, 2019 | United States of

America | 4,796 | 2,317 (48.3) | 72.75±8.40 | HFpEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 2,407 | Valsartan, 160 mg

twice daily | 2,389 | 35 | Hypotension (G2-3),

worsening renal function (G2-3), hyperkalemia (G1-2), angioedema

(G3), cough (G1-2), dizziness (G1-2), acute kidney injury (G2-3),

elevated creatinine (G2-3), syncope (G2-3) | (9) |

| Vardeny et

al, 2016 | United States of

America | 3,549 | 2,785 (78.5) | 63.85±11.48 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 200 mg twice

daily | 1,755 | Enalapril, 10 mg

twice daily | 1,794 | 27 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), hypotension (G2-3), worsening renal function (G2-3), acute

kidney injury (G2-3), angioedema (G3), cough (G1-2), dizziness

(G1-2) | (19) |

| Chandra et

al, 2022 | United States of

America | 4,476 | 2,192 (48.9) | 72.60±8.50 | HFpEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 2,226 | Valsartan, 160 mg

twice daily | 2,250 | 36 | NA | (20) |

| Desai et al,

2019 | United States of

America | 464 | 355 (76.5) | 71.70±10.30 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 231 | Enalapril, 10 mg

twice daily | 233 | 3 | Hypotension (G2-3);

no significant CTCAE-graded differences in renal dysfunction

(G2-3), hyperkalemia (G1-2), or angioedema (G3) | (21) |

| Gao et al,

2020 | China | 120 | 88 (73.3) | 70.30±7.30 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 50 mg twice

daily | 60 | Valsartan, 80 mg

once daily | 60 | 18 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), acute kidney injury

(G2-3), hypotension (G2-3), all-cause morality (G5),

cardiovascular-associated mortality (G5), discontinuation due to

AEs (G3) | (22) |

| Ghafur et

al, 2020 | Bangladesh | 100 | 67(67) | 61.40±11.90 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 100 mg twice

daily | 50 | Valsartan, 80 mg

twice daily | 50 | 4 |

Cardiovascular-associated mortality (G5),

hospitalization due to HF (G3), elevated serum creatinine (G2-3),

hyperkalemia (G1-2), hyperglycemia (G1-2) | (23) |

| Halle et al,

2021 | Germany | 201 | 163 (81.1) | 66.90±10.40 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 103 | Enalapril, 10 mg

twice daily | 98 | 3 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), hypotension (G2-3),

angioedema (G3), acute kidney injury (G2-3) | (24) |

| Kang et al,

2019 | South Korea | 118 | 72(61) | 62.60±11.20 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 60 | Valsartan, 80 mg

once daily | 58 | 6 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), hypotension (G2-3), worsening renal function (G2-3),

dizziness (G1-2), cough (G1-2) | (25) |

| Li et al,

2020 | China | 80 | 47 (58.8) | 63.00±5.70 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 200 mg twice

daily | 40 | Perindopril

tert-butylamine, 4 mg once daily | 40 | 3 | NA | (26) |

| Mann et al,

2022 | United States of

America | 335 | 245 (73.1) | 59.40±13.50 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 167 | Valsartan, 160 mg

twice daily | 168 | 6 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), hypotension (G2-3),

hospitalization (G3-4), cardiovascular-associated mortality

(G5) | (27) |

| Mentz et al,

2023 | United States of

America and Canada | 466 | 224 (48.1) | 71.40±3.10 | HFpEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 233 | Valsartan, 160 mg

twice daily | 233 | 2 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), hypotension (G2-3), worsening renal function (G2-3), acute

kidney injury (G2-3), dizziness (G1-2), cough (G1-2), fatigue

(G1-2) | (28) |

| Piepoli et

al, 2020 | Italy | 619 | 487 (78.7) | 66.90±10.70 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 309 | Enalapril, 10 mg

twice daily | 310 | 3 | Hyperkalemia

(G1-2), hypotension (G2-3), worsening renal function (G2-3), cough

(G1-2), dizziness (G1-2) | (29) |

| Pieske et

al, 2021 | Germany | 2,572 | 1,271 (49.4) | 72.60±8.50 | HFpEF, HFmrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 1,288 | Valsartan, 160 mg

twice daily | 1,284 | 6 | Hypotension (G2-3),

albuminuria (G1-2), hyperkalemia (G1-2) | (30) |

| Solomon et

al, 2012 | United States of

America | 301 | 131 (43.5) | 71.00±9.10 | HFpEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 200 mg twice

daily | 149 | Valsartan, 160 mg

twice daily | 152 | 26 | Hypotension (G2-3),

albuminuria (G1-2), hyperkalemia (G1-2), hypotension (G2-3),

elevated serum creatinine (G2-3), hyperkalemia (G1-2), angioedema

(G3), liver-related AEs (G1-2). | (31) |

| Tsutsui et

al, 2021 | Japan | 223 | 192 (86.1) | 67.85±10.36 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 100 mg twice

daily | 111 | Enalapril, 10 mg

twice daily | 112 | 12 | Hypotension (G2-3),

hyperkalemia (G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), cough (G1-2),

dizziness (G1-2), angioedema (G3), acute kidney injury (G2-3) | (32) |

| Velazquez et

al, 2018 | United States of

America | 881 | 635 (72.1) | 62.00±3.42 | HFrEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 97/103 mg twice

daily | 440 | Enalapril, 5 mg

twice daily | 441 | 2 | Hypotension (G2-3),

hyperkalemia (G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), acute kidney

injury (G2-3), angioedema (G3), cough (G1-2), dizziness (G1-2),

elevated creatinine (G2-3) | (33) |

| Voors et al,

2015 | United States of

America | 301 | 131 (43.5) | 70.73±9.01 | HFpEF |

Sacubitril/valsartan, 50 mg twice

daily | 60 | Valsartan, 80 mg

once daily | 60 | 8.3 | Hypotension (G2-3),

hyperkalemia (G1-2), worsening renal function (G2-3), acute kidney

injury (G2-3), cough (G1-2), dizziness (G1-2), angioedema (G3) | (34) |

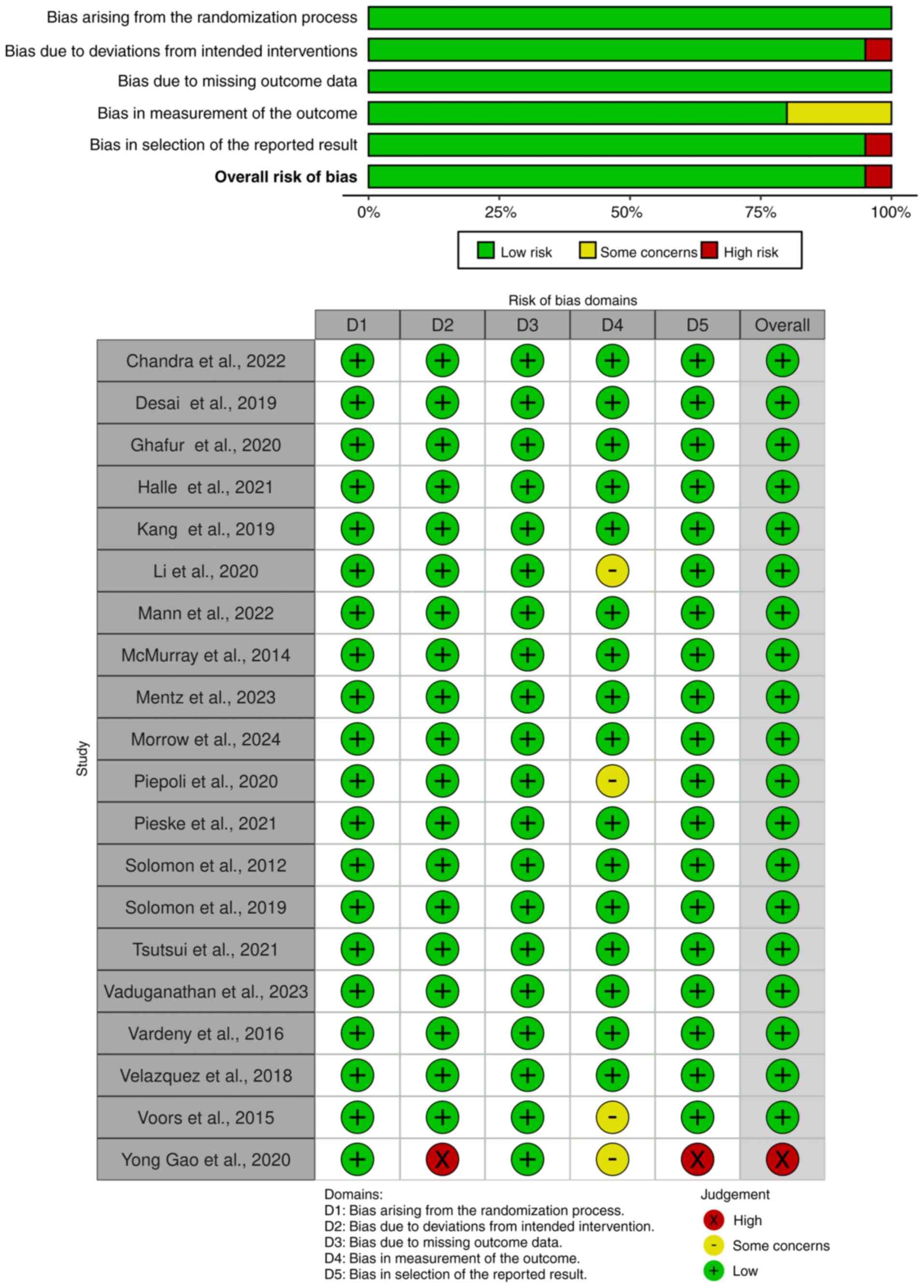

Quality assessment of studies

Studies were assessed for bias using the Cochrane

RoB 2.0 tool (Fig. 2). A total of

two studies (26,34) were rated as having some concerns,

while one study (22) was judged to

have a high risk of bias. Gao et al (22) was rated high risk in the domains of

deviation from intended interventions and selection of the reported

result, primarily due to the absence of blinding procedures and

lack of trial registration. This omission raises concern about

selective outcome reporting, particularly in the context of

exploratory or post hoc analyses. Additionally, outcome measurement

in the aforementioned study was graded as some concerns due to

unblinded assessment of endpoints. Li et al (26) demonstrated some concerns in the

domains of randomization and outcome measurement, as the allocation

concealment process was not clearly reported and there was

insufficient detail regarding blinding of outcome assessors. Voors

et al (34) was also rated

as having some concerns in the domain of missing outcome data, due

to incomplete reporting of renal endpoints from a post hoc

analysis. Despite these exceptions, the overall risk of bias across

trials was low, indicating generally high methodological

quality.

Efficacy of ARNI

The clinical outcomes regarding the efficacy and

safety of ARNI compared with the control group are summarized in

Table II. The analysis of the

included studies highlighted favorable results associated with ARNI

use (Figs. S1 and S2).

| Table IIEffectiveness and safety of ARNI vs.

control. |

Table II

Effectiveness and safety of ARNI vs.

control.

| A,

Effectiveness |

|---|

| Outcome | ARNI (n/total) | Control

(n/total) | RR (95%CI) | I2

value,% | Favours ARNI | Favours

control | Significant |

|---|

| All-cause

mortality | 1,100/8,630 | 1,226/8,646 | 0.67

(0.83-0.97) | 25.1 | Yes | No | Yes |

|

Cardiovascular-associated mortality | 800/7,165 | 952/7,164 | 0.84

(0.77-0.92) | 41 | Yes | No | Yes |

| HF

hospitalization | 1,079/7,488 | 1,234/7,497 | 0.87

(0.81-0.93) | 60 | Yes | No | Yes |

| MACE | 1,981/8,413 | 2,241/8,471 | 0.89

(0.85-0.94) | 57 | Yes | No | Yes |

| B, Safety |

| Outcome | ARNI (n/total) | Control

(n/total) | RR (95%CI) | I2

value,% | Favours ARNI | Favours

control | Significant |

| Renal

impairment | 719/11,588 | 798/11,648 | 0.91

(0.83-1.00) | 46.4 | Yes | No | No |

| Hyperkalaemia | 796/7,395 | 804/7,422 | 0.99

(0.90-1.09) | 47 | Yes | No | No |

| Angioedema | 41/11,389 | 28/11,446 | 1.44

(0.90-2.29) | 4.9 | No | Yes | No |

| Symptomatic

hypotension | 1,759/11,492 | 1,150/11,544 | 1.54

(1.43-1.65) | 54.2 | No | Yes | Yes |

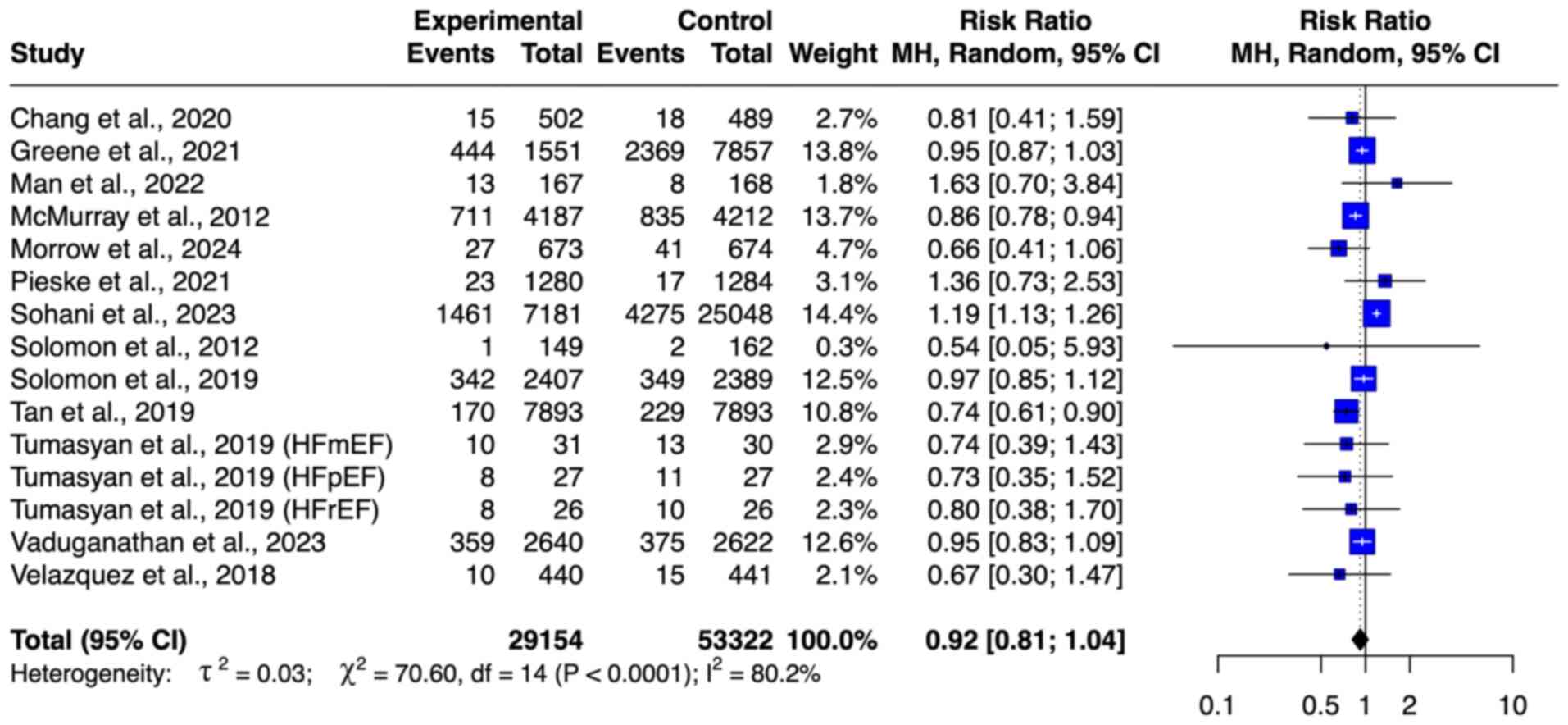

All-cause mortality

A total of six studies (8,9,27,30,31,33)

with 17,276 patients with HF, including 8,630 patients who received

ARNI and 8,646 patients who received control, were included in the

meta-analysis of all-cause mortality (Fig. 3). ARNI in patients with HF

significantly decreased all-cause mortality (RR=0.67; 95%

CI=0.83-0.97). No outlier was detected based on the funnel plot

(Fig. S1). The level of

heterogeneity was low (I2=25.1%).

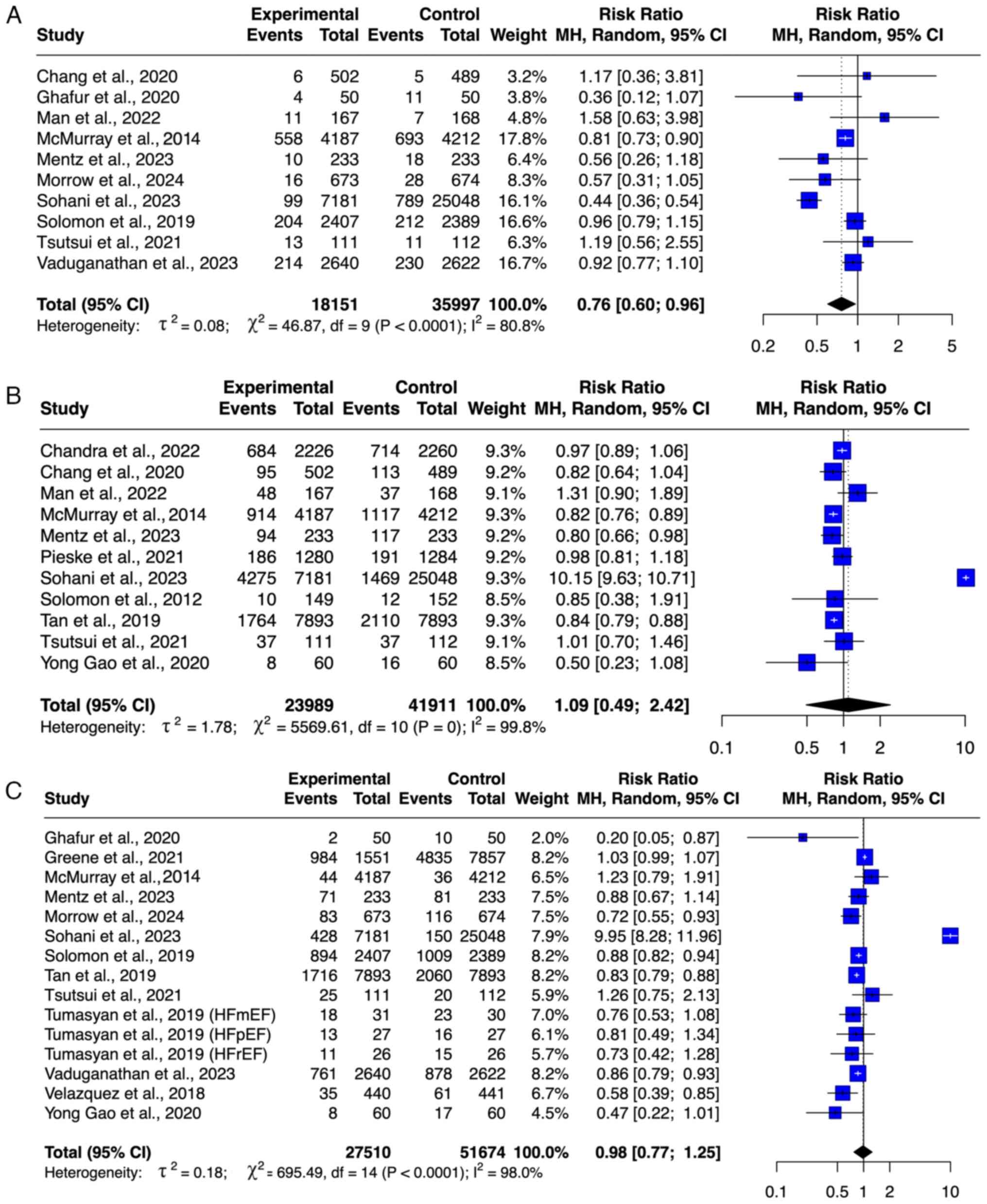

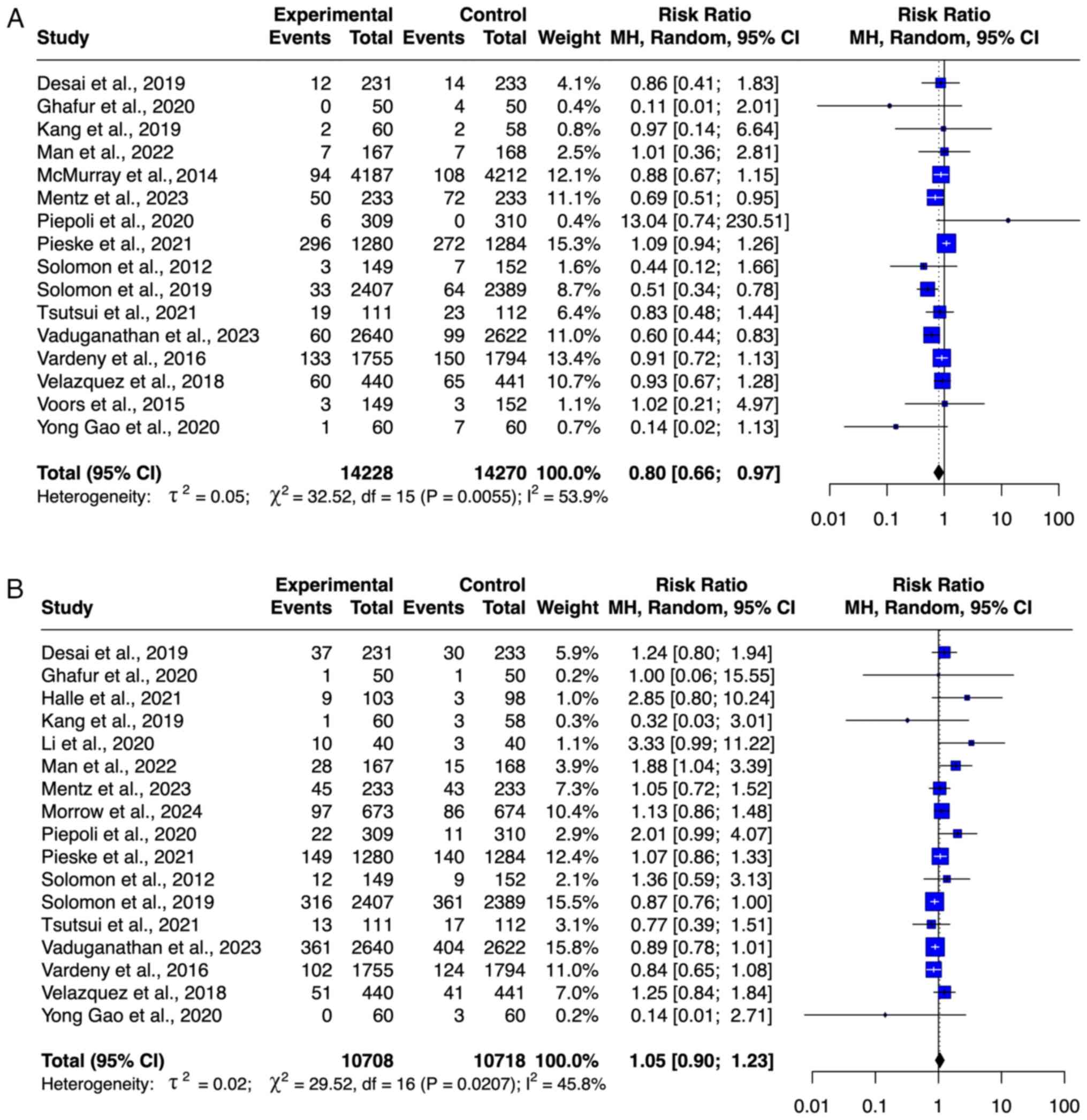

Cardiovascular-associated mortality. A

cumulative total of 14,319 participants, including 7,155

participants treated with ARNI and 7,164 participants in the

control group from six studies (8,9,23,27,28,32),

were included in the meta-analysis of cardiovascular-related

mortality (Fig. 4A). The use of

ARNI for various types of HF was associated with a significantly

lower risk of cardiovascular-associated mortality (RR=0.84; 95%

CI=0.77-0.92). No outlier was detected based on the funnel plot

(Fig. S1). The degree of

heterogeneity was low (I2=41%).

HF-associated hospitalization. A total of

seven studies (8,9,22,23,28,32,33),

with 14,985 patients, including 7,488 patients who received ARNI

and 7,497 patients in the control, were included in the

meta-analysis of HF-related hospitalization (Fig. 4B). ARNI resulted in a significant

decrease in the risk of HF-related hospitalization (RR=0.87; 95%

CI=0.81-0.93). No outlier was detected on the basis of the funnel

plot (Fig. S1). The level of

heterogeneity was moderate (I2=60%).

MACEs. A total of eight studies (8,20,22,27,28,30-32)

with 16,884 patients, including 8,413 patients who received ARNI

and 8,471 patients in the control group, were included in the

meta-analysis of MACE (Fig. 4C).

Treatment with ARNI significantly decreased the risk of MACEs in

the pooled analysis (RR=0.89; 95% CI=0.85-0.94). No outlier was

detected on the basis of the funnel plot (Fig. S1). The level of heterogeneity was

moderate (I2=57%).

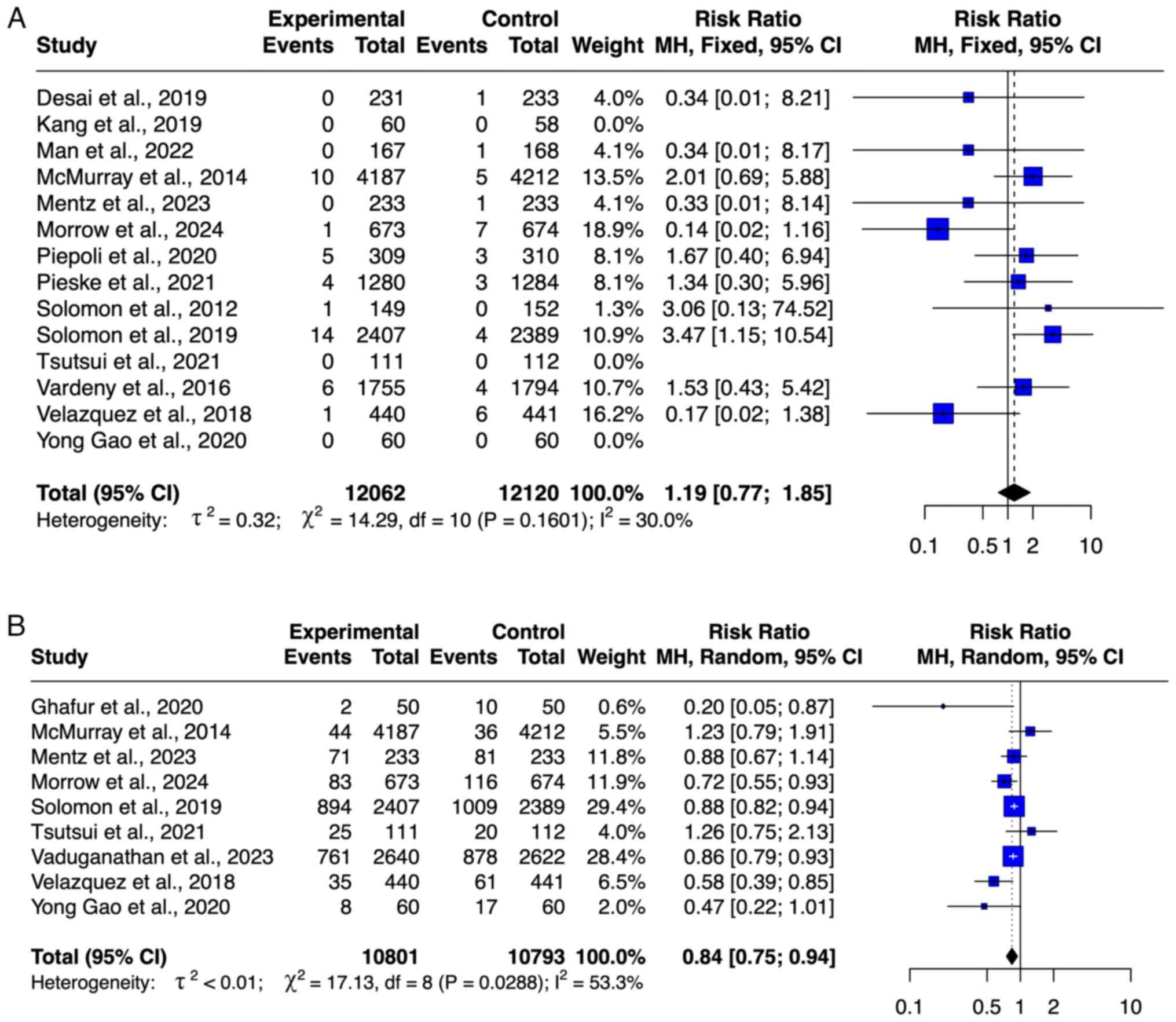

Safety outcome of ARNI. Renal

impairment

A total of 23,236 participants from 15 studies

(8,9,19,21-23,25,27-34)

were included in the meta-analysis of renal impairment outcomes,

comprising 11,588 participants in the ARNI group and 11,648

participants in the control group (Fig.

5A). ARNI use was associated with decreased risk of renal

impairment (RR=0.91; 95% CI: 0.83-1.00), although this was not

significant. No publication bias was observed based on the funnel

plot, and heterogeneity was low (I²=46.4%).

Hyperkalemia

A total of 14,817 participants, consisting of 7,395

participants treated with ARNI and 7,422 participants in the

control group from 15 studies (9,19,21-33),

were included in the meta-analysis of hyperkalaemia (Fig. 5B). The use of ARNI in HF

interventions showed a lower risk of hyperkalaemia but this was not

significant (RR=0.99; 95% CI=0.90-1.09). No outlier was detected

based on the funnel plot (Fig.

S2). The degree of heterogeneity was low

(I2=47%).

Angioedema

A total of 13 studies (8,9,19,21,22,25,27,28-33)

with a total sample of 22,835 patients, consisting of 11,389

patients who received ARNI and 11,446 patients who received

control, were included in the meta-analysis of angioedema (Fig. 6A). The meta-analysis showed no

significant difference between the ARNI and the control groups in

decreasing the risk of angioedema (RR=1.44; 95% CI=0.90-2.29). No

outlier was detected based on the funnel plot (Fig. S2). The level of heterogeneity was

very low (I2=4.9%).

Symptomatic hypotension

A total of 23,036 participants, comprising 11,492

participants treated with ARNI and 11,544 participants in the

control group from 14 studies (8,9,19,21,22,24,25,27-33)

was included in the meta-analysis of symptomatic hypotension

(Fig. 6B). ARNI was associated with

a significantly increased risk of symptomatic hypotension (RR=1.54;

95% CI=1.43-1.65). No outlier was detected based on the funnel plot

(Fig. S2). The degree of

heterogeneity was moderate (I2=54.2%).

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analyses stratified by LVEF (≤40 vs.

>40%) demonstrated no significant interaction between LVEF

category and the effect of ARNI across all assessed outcomes

(Table III). The decrease in

all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality, MACEs and HF

hospitalization was consistent between subgroups. Hypotension risk

was increased in both LVEF subgroups, whereas hyperkalemia risk

showed a non-significant trend towards elevation in LVEF ≤40% but

not in LVEF >40%. Notably, angioedema risk was higher in the

LVEF >40% subgroup, though the difference was not statistically

significant. The incidence of renal impairment was lower in the

LVEF >40% subgroup; however, no significant subgroup effect was

detected. Heterogeneity across most comparisons was minimal, except

for hyperkalemia and angioedema, which showed moderate

variability.

| Table IIISubgroup analysis. |

Table III

Subgroup analysis.

| Outcome | LVEF, % | Number of

studies | RR | 95% CI | P-value | I2

value, % | (Refs.) |

|---|

| All-cause

mortality | ≤40 | 3 | 0.89 | 0.67-1.19 | 0.52 | 0.0 | (8,27,33) |

| | >40 | 3 | 0.99 | 0.86-1.13 | | | (9,30,31) |

|

Cardiovascular-associated mortality | ≤40 | 4 | 0.88 | 0.58-1.32 | 0.86 | 0.0 | (8,23,27,32) |

| | >40 | 2 | 0.83 | 0.52-1.32 | | | (9,28) |

| MACE | ≤40 | 4 | 0.92 | 0.70-1.21 | 0.85 | 0.0 | (8,22,27,32) |

| | >40 | 4 | 0.95 | 0.88-1.02 | | | (20,28,30,31) |

| Hypotension | ≤40 | 11 | 1.48 | 1.25-1.75 | 0.73 | 0.0 | (8,19,21-25,27,29,32,33) |

| | >40 | 4 | 1.62 | 1.16-2.28 | | | (9,28,30,31) |

|

Hospitalization | ≤40 | 5 | 0.73 | 0.44-1.21 | 0.48 | 0.0 | (8,22,23,32,33) |

| | >40 | 2 | 0.88 | 0.82-1.94 | | | (9,28) |

| Hyperkalemia | ≤40 | 11 | 1.10 | 0.94-1.30 | 0.11 | 60.0 | (17,21-27,29,32,33) |

| | >40 | 4 | 0.94 | 0.84-1.05 | | | (9,28,30,31) |

| Angioedema | ≤40 | 9 | 1.10 | 0.61-1.99 | 0.16 | 48.2 | (8,19,21,22,25,27,29,32,33) |

| | >40 | 4 | 2.22 | 1.01-4.87 | | | (9,28,29,31) |

| Renal

impairment | ≤40 | 10 | 0.89 | 0.77-1.03 | 0.23 | 31.4 | (8,19,21-23,25,27,29,32,33) |

| | >40 | 5 | 0.67 | 0.44-1.04 | | | (9,28,30,31,34) |

Meta-regression analysis

Meta-regression analysis revealed significant

study-level predictors across outcomes (Table IV). Higher eGFR was associated with

a lower risk of all-cause mortality [standard error (SE)=0.06].

Higher NT-proBNP increased risk (SE=0.06), whereas higher BMI

decreased risk of cardiovascular-associated mortality (SE=0.05).

Hypotension was less common in females (SE=0.15) but more likely

with higher eGFR (SE=1.07). Female sex was the only factor

associated with a decreased risk of HF hospitalization (SE=0.15).

Hyperkalemia risk was greater with older age (SE=0.84), female sex

(SE=0.11) and lower LVEF (SE=0.29). Angioedema risk increased with

higher heart rate (SE=1.46), diastolic BP (SE=2.40) and NT-proBNP

(SE=0.77). Higher SBP was the only significant predictor of renal

impairment (SE=1.60). All other covariates were not significantly

associated with these outcomes.

| Table IVRandom-effects univariate regression

analysis of ARNI therapeutic outcomes by sociodemographic and

clinical characteristics. |

Table IV

Random-effects univariate regression

analysis of ARNI therapeutic outcomes by sociodemographic and

clinical characteristics.

| A, All-cause

mortality |

|---|

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

|---|

| Age | -0.05 | 0.15 | 0.719 |

| Female | -0.18 | 0.27 | 0.511 |

| NT-proBNP | -0.01 | 0.08 | 0.857 |

| LVEF | -0.03 | 0.08 | 0.693 |

| HR | -0.12 | 0.08 | 0.116 |

| SBP | 0.52 | 0.47 | 0.266 |

| BMI | -0.04 | 0.25 | 0.868 |

| eGFR | -0.21 | 0.06 | 0.001 |

| sCr | -0.10 | 0.06 | 0.102 |

| B,

Cardiovascular-associated mortality |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | 0.46 | 0.56 | 0.416 |

| Female | -0.30 | 0.24 | 0.211 |

| NT-proBNP | -0.14 | 0.06 | 0.015 |

| LVEF | -0.07 | 0.18 | 0.687 |

| HR | -1.18 | 0.62 | 0.059 |

| SBP | 0.46 | 0.48 | 0.335 |

| BMI | -0.20 | 0.05 | <0.001 |

| eGFR | -1.01 | 0.55 | 0.065 |

| sCr | -0.17 | 0.10 | 0.081 |

| C, Major adverse

cardiovascular event |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | 0.36 | 1.40 | 0.799 |

| Female | -0.06 | 0.64 | 0.925 |

| NT-proBNP | -0.04 | 0.06 | 0.427 |

| LVEF | -0.15 | 0.20 | 0.460 |

| HR | -0.05 | 0.30 | 0.877 |

| SBP | 0.36 | 0.29 | 0.212 |

| BMI | -0.03 | 0.24 | 0.918 |

| eGFR | -0.40 | 0.29 | 0.163 |

| sCr | -1.98 | 2.47 | 0.423 |

| D, Hypotension |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | 0.84 | 0.55 | 0.127 |

| Female | -0.38 | 0.15 | 0.009 |

| NT-proBNP | -0.02 | 0.10 | 0.839 |

| LVEF | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.897 |

| HR | 0.59 | 1.77 | 0.738 |

| SBP | -0.12 | 0.17 | 0.469 |

| DBP | -0.04 | 0.06 | 0.486 |

| BMI | 0.75 | 1.36 | 0.581 |

| eGFR | -2.29 | 1.07 | 0.033 |

| sCr | -2.76 | 0.99 | 0.242 |

| E,

Hospitalization |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | -0.68 | 0.26 | 0.948 |

| Female | -0.49 | 0.15 | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP | 0.22 | 0.47 | 0.635 |

| LVEF | -0.21 | 0.52 | 0.683 |

| HR | -0.43 | 1.61 | 0.948 |

| SBP | 0.17 | 0.57 | 0.971 |

| BMI | -1.08 | 2.03 | 0.596 |

| eGFR | -0.97 | 0.88 | 0.273 |

| sCr | 2.74 | 0.19 | 0.375 |

| F,

Hyperkalemia |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | 2.61 | 0.84 | 0.002 |

| Female | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.001 |

| NT-proBNP | -0.14 | 0.18 | 0.453 |

| LVEF | 0.81 | 0.29 | 0.005 |

| HR | -2.15 | 3.05 | 0.481 |

| SBP | 4.55 | 1.63 | 0.084 |

| BMI | 0.58 | 2.52 | 0.818 |

| Egfr | -0.52 | 1.40 | 0.710 |

| sCr | -2.71 | 1.24 | 0.028 |

| G, Angioedema |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | -8.16 | 2.33 | 0.126 |

| Female | -0.57 | 0.43 | 0.188 |

| NT-proBNP | 1.67 | 0.77 | 0.031 |

| LVEF | -0.36 | 0.92 | 0.695 |

| HR | 5.59 | 1.46 | 0.016 |

| SBP | -10.02 | 1.71 | 0.349 |

| DBP | 11.94 | 2.40 | 0.007 |

| BMI | 4.18 | 2.03 | 0.077 |

| eGFR | -5.44 | 1.84 | 0.488 |

| sCr | 11.94 | 1.40 | 0.007 |

| H, Renal

impairment |

| Covariate | Estimate | Standard error | P-value |

| Age | 1.81 | 1.51 | 0.230 |

| Female | -0.16 | 0.14 | 0.271 |

| NT-proBNP | -0.23 | 0.18 | 0.193 |

| LVEF | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.122 |

| HR | -0.64 | 1.80 | 0.723 |

| SBP | 5.22 | 1.60 | 0.001 |

| DBP | 8.05 | 2.83 | 0.239 |

| BMI | 1.39 | 0.89 | 0.121 |

| eGFR | -0.84 | 1.29 | 0.516 |

| sCr | -0.61 | 1.43 | 0.670 |

Discussion

The present meta-analysis confirmed the superior

efficacy of ARNI therapy in reducing all-cause and cardiovascular

mortality, HF-associated hospitalization and MACE across HF

phenotypes. The magnitude of risk reduction observed in

cardiovascular outcomes supports the pharmacological rationale of

neprilysin-angiotensin receptor pathway dual inhibition (33). These findings align with those of

earlier trials, including PARADIGM-HF, and meta-analyses, but

include a broader range of HF subtypes and integrated

meta-regression analyses to elucidate outcome modifiers (13,14,36).

The present findings support previous studies that

showed the efficacy of ARNI in HF (8,13,34,35).

Nielsen et al (36)

demonstrated that sacubitril/valsartan significantly decreased

all-cause mortality and serious AEs in HFrEF compared with

ACE-Is/ARBs. Similarly, Park et al (13) reported a reduction in all-cause and

cardiac-associated mortality and MACEs with ARNI therapy. However,

both the aforementioned studies reported an increased risk of

hypotension. The present analysis emphasizes the robust mortality

benefit of ARNIs and confirms its association with hypotension,

potentially due to enhanced NP activity, RAAS suppression and

sympathetic inhibition, which promote vasodilation and natriuresis

(8). Despite this hypotension risk,

ARNI also substantially mitigated renal impairment, reinforcing its

net clinical benefit. Its superior antihypertensive effect arises

from early sodium diuresis and sustained vasodilation, making it

more effective than traditional RAS inhibitors, even as natriuretic

effects wane with prolonged use (37).

The present meta-analysis provides a broader

evaluation of ARNI therapy across the full spectrum of HF

phenotypes, including HFrEF, HFmrEF and HfpEF, which have been

underrepresented or inconsistently analyzed in earlier reviews

(13,38). While landmark trials such as

PARADIGM-HF and PARAGON-HF have established the basis for ARNIs in

HF management, previous meta-analyses have largely centered on

patients with rEF, limiting their relevance to more diverse

clinical presentations (17,18).

By contrast, the present study integrated findings from a wider

range of HF subtypes and incorporated meta-regression techniques to

explore how key clinical and hemodynamic variables such as blood

pressure, renal function and NT-proBNP levels modify ARNI effects.

This approach not only enhances the generalizability of findings

but also allows for more personalized, phenotype-specific

interpretations of efficacy and safety. The present study

complements recent comprehensive reviews, such as Tromp et

al (39) and van Essen et

al (40), and focused analysis

on BP-associated outcomes and renal parameters, which are relevant

to daily clinical decision-making. The present analysis support

more precise and hypertension-conscious use of ARNIs in routine

practice, aligning with the growing emphasis on individualized

treatment in HF care.

Meta-regression analysis revealed that a lower eGFR

was associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality,

supporting the findings of Khan et al (41), which linked a rapid decrease in eGFR

(>15 ml/min/year) with a higher mortality rate. Consistent with

the results of a previous study, the present analysis demonstrated

that higher SBP was associated with worsening renal impairment

(42). RAAS upregulation, increased

sympathetic nervous system activity, elevated pro-inflammatory

factors and left ventricular hypertrophy progression are potential

mechanisms underlying these findings, all contributing to

difficulties in volume handling, pump failure and mortality

(41). Additionally, female sex was

associated with a lower risk of HF-associated hospitalization,

potentially due to the effect of estrogen on vascular function,

inflammatory response, metabolism, cardiac myocytes and the

development of hypertrophy yielding better outcomes. Lastly,

elevated NT-proBNP levels were associated with

cardiovascular-associated mortality; previous findings showed that

NT-proBNP indicates increased cardiac stress (43,44).

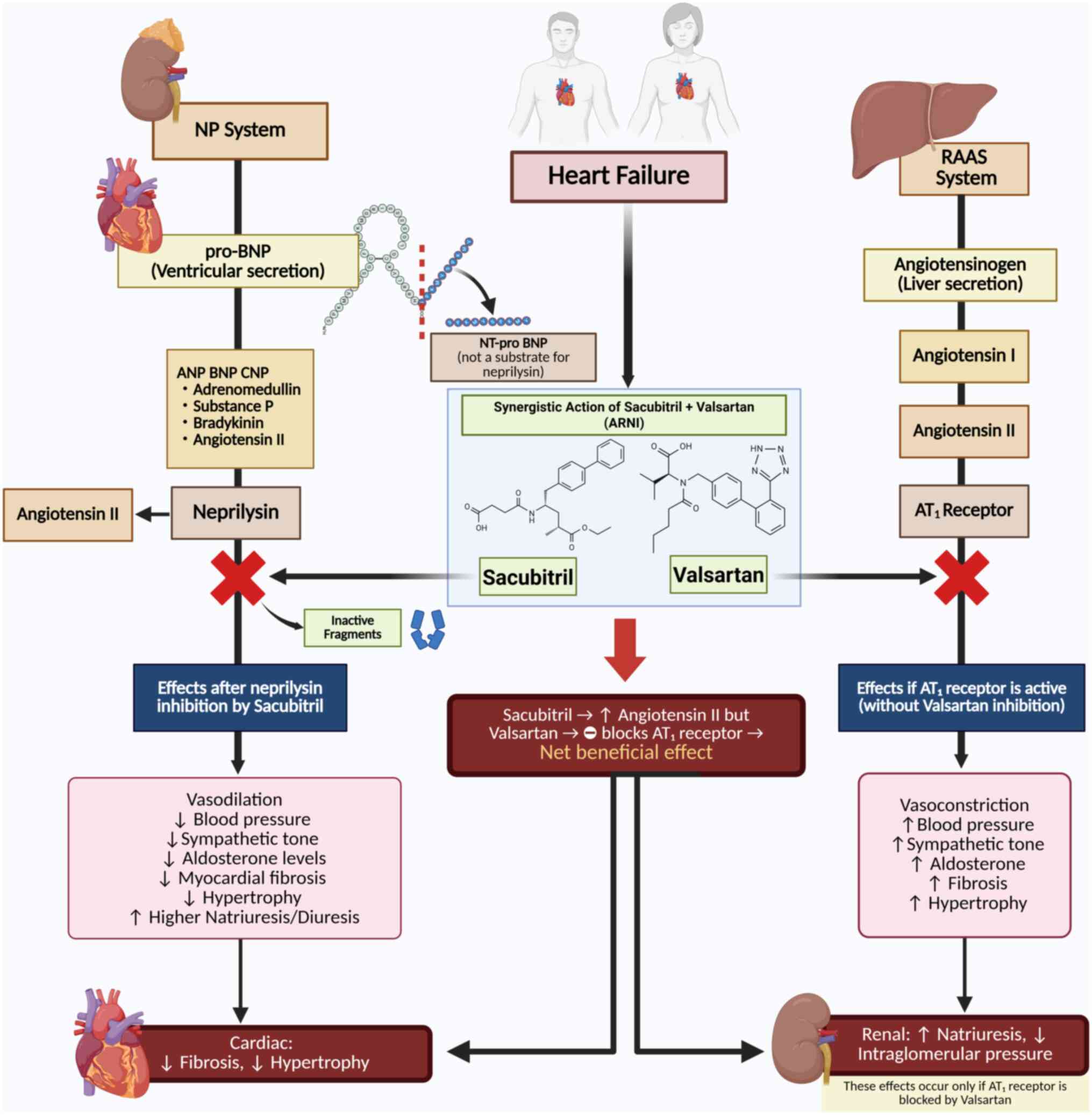

ARNI exerts its therapeutic effect in HF through a

dual mechanism that enhances beneficial pathways and suppresses

maladaptive neurohormonal activation (Fig. 7). Sacubitril inhibits neprilysin,

preventing the degradation of NPs (atrial, brain and C-type),

causing vasodilation, natriuresis, diuresis and attenuation of

myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy. Simultaneously, valsartan

blocks the angiotensin 1 receptor, counteracting the effects of

angiotensin II and decreasing vasoconstriction, BP, aldosterone

secretion and cardiac remodeling (17).

The mechanisms of ARNI vary across different HF

stages with distinct EF profiles. In HfrEF (LVEF <40%), ARNI

improves cardiac output by decreasing preload and afterload and

improving ventricular contractility. In HfmrEF (LVEF, 40-49%), ARNI

targets both systolic and diastolic dysfunction, stabilizing LVEF

and decreasing vascular resistance. In HFpEF (LVEF ≥50%), ARNI

mitigates diastolic dysfunction by lowering left ventricular

filling pressure and relieving systemic congestion, with potential

antifibrotic effects that improve myocardial compliance (45). These phenotype-specific actions

highlight the versatility of ARNI across the HF spectrum.

ARNI therapy has become a transformative option in

HF management, particularly for patients with HFrEF who remain

symptomatic despite optimal treatment. By combining angiotensin II

receptor blockade and neprilysin inhibition, ARNI provides a dual

mechanism that attenuates the harmful effects of the RAAS and

improves the protective NP system (19,46).

This causes significant decreases in all-cause mortality,

HF-related hospitalization and improvements in the quality of life,

including enhanced exercise capacity and symptom control (8,19,44).

Additionally, the decrease in hospitalizations lessens the

healthcare system burden and mitigates costs (34). Although the benefits of ARNI in

HFpEF remain poorly understood, its potential role in this subgroup

emphasizes the need for further research to identify its influence

across all HF phenotypes.

Beyond ARNI therapy, the management of congestive HF

continues to evolve with optimizing volume control strategies. Duta

et al (10) demonstrated the

use of acetazolamide in combination with loop diuretics to enhance

decongestive therapy. This combinatorial approach not only augments

natriuresis but also addresses diuretic resistance, which is a

challenge in HF management. Although ARNI has demonstrated

beneficial effects on hemodynamics and renal function, residual

congestion remains a clinical concern in a subset of patients.

Therefore, integrating ARNI therapy with advanced decongestive

regimens may offer synergistic benefits, particularly in patients

with persistent volume overload. Future research should explore how

ARNI and adjunctive diuretic strategies can be co-optimized to

maximize clinical outcomes while minimizing renal and hemodynamic

complications.

The effective use of ARNI necessitates precise

dosing and careful patient monitoring to optimize outcomes and

minimize risks. Initial therapy typically starts with 49/51 mg

sacubitril/valsartan twice daily, with a lower dose of 24/26 mg

twice daily recommended for patients with significant renal

impairment or hypotension history (8,33). The

dose is subsequently titrated to a target of 97/103 mg twice daily

for 2-4 weeks, as tolerated, to optimize therapeutic benefits and

minimize AEs, including hypotension, hyperkalemia or renal

dysfunction (8,9). Regular BP, serum electrolyte and renal

function monitoring is crucial during titration and throughout

therapy, with dose adjustments tailored to patient needs,

particularly in the presence of comorbidities (47,48).

Park et al (49) reported

that compared with enalapril and ARBs, sacubitril/valsartan is a

cost-effective treatment for HFrEF. This supports its use as a

clinically valuable and economically sustainablealternative for

cardiologists and decision-makers in selecting therapeutic

approaches (49).

Multiple clinical factors predict hypotension risk

during ARNI therapy, informing targeted treatment decisions. To

minimize this risk, sacubitril/valsartan should be initiated at a

low dose (25-50 mg once daily), with close BP monitoring and

titrated every 2-4 weeks to a target of 100-150 mg twice daily as

tolerated (50). Caution is

required in older adult patients, those with arteriosclerosis or

those with advanced renal impairment, where reduced renal perfusion

increases susceptibility to hypotension and GFR decline (51). To avoid excessively low BP and

protect renal function, the use of other antihypertensive drugs,

including calcium channel blockers, diuretics and α- and

β-blockers, should be decreased. These approaches optimize the

renal benefits of ARNI through NP action. Furthermore, multivariate

analysis has identified baseline atrial fibrillation, a higher

blood urea nitrogen/creatinine (BUN/Cr) ratio and lower SBP as

significant independent predictors of hypotension following ARNI

administration (52). Recognizing

these risk factors allows clinicians to more safely and effectively

tailor therapy.

The present study benefits from a large sample size

(>20,000 patients), adherence to the PRISMA guidelines and

rigorous risk-of-bias assessment, enhancing the reliability and

generalizability of the findings. It confirms the efficacy and

safety of ARNI in decreasing cardiovascular-associated and

all-cause mortality, hospitalization and renal impairment across HF

spectrums. Subgroup analyses were conducted to explore potential

heterogeneity. Additionally, meta-regression analysis was performed

to decrease bias by analyzing the influence of variables, including

age, sex, NT-proBNP levels, LVEF, HR, SBP, BMI, eGFR and sCr

levels, on outcomes, facilitating more accurate identification of

potential confounding factors. However, the present study had

limitations. Heterogeneity in the follow-up durations across trials

may affect the comparability of the outcomes. The

underrepresentation of populations with HFmrEF limits the

robustness of the conclusions for this subgroup. The absence of

meta-regression accounting for patient comorbidities, including

diabetes, chronic kidney disease or atrial fibrillation, prevents a

more nuanced interpretation of treatment effects. Fourth, although

the overall bias was low, three studies demonstrated some concerns

and one exhibited high risk of bias, which may influence the pooled

estimates. The predominance of studies conducted in high-income

Western countries may limit the generalizability to diverse global

populations with differing clinical practices and healthcare

infrastructures. A further limitation is the predominant reliance

on eGFR to assess renal outcomes. While several studies reported

additional parameters, including serum Cr (28,33,34)

and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (31), BUN was not consistently included as

a diagnostic endpoint across trials. Future research should

implement standardized renal outcome measures that incorporate a

broader range of biomarkers to facilitate more comprehensive and

clinically relevant assessment of renal function.

ARNIs significantly improve clinical outcomes in

patients with HF across the spectrum of EF phenotypes, particularly

in reducing all-cause and cardiovascular-associated mortality,

HF-associated hospitalization and renal impairment. However, the

increased risk of hypotension necessitates close monitoring and

targeted dose adjustment. The present findings support the broader

adoption of ARNI in HF management, focusing on patient-specific

characteristics, including renal function, sex and baseline BP.

Future large-scale trials in diverse populations, including

underrepresented HF phenotypes and resource-limited settings, are

warranted to validate and extend these findings.

Supplementary Material

Funnel plot of the efficacy of

angiotensin receptor-neprilysin inhibitor compared with control

treatment for heart failure management. (A) Cardiovascular-related

and (B) all-cause mortality. (C) Major adverse cardiovascular

events. (D) Heart failure hospitalization.

Safety of angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibitor compared with control treatment for

heart failure management. (A) Hyperkalemia. (B) Symptomatic

hypotension. (C) Angioedema. (D) Renal impairment.

PICO framework.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ms Rahmati Putri

Yaniafari (Nanyang Technological University, Singapore) for helping

with literature retrieval.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are

included in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contribution

DDCHR, SCS, KCT, INK, BI, AI and MAE designed the

study. DDCHR, SCS, KCT, JAJMNL, INK and MAE conceived the study and

performed the literature review. DDCHR assessed the risk of bias.

JAJMNL and SHR confirm the authenticity of all the raw data..

DDCHR, SCS, JAJMNL, SHR, INK, BI and AI analyzed and interpreted

data. DDCHR, SCS, INK, BI, AI, and MAE wrote the manuscript. All

authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

Use of artificial intelligence tools

During the preparation of this work, artificial

intelligence tools were used to improve the readability and

language of the manuscript, and subsequently, the authors revised

and edited the content produced by the artificial intelligence

tools as necessary, taking full responsibility for the ultimate

content of the present manuscript.

References

|

1

|

Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D,

Allen LA, Byun JJ, Colvin MM, Deswal A, Drazner MH, Dunlay SM,

Evers LR, et al: 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline for the management of

heart failure: A report of the American College of

Cardiology/American heart association joint committee on clinical

practice guidelines. Circulation. 145:e895–e1032. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Kemp CD and Conte JV: The pathophysiology

of heart failure. Cardiovasc Pathol. 21:365–371. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Savarese G, Becher PM, Lund LH, Seferovic

P, Rosano GMC and Coats AJS: Global burden of heart failure: A

comprehensive and updated review of epidemiology. Cardiovasc Res.

118:3272–3287. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Farré N, Vela E, Clèries M, Bustins M,

Cainzos-Achirica M, Enjuanes C, Moliner P, Ruiz S, Verdú-Rotellar

JM and Comín-Colet J: Real world heart failure epidemiology and

outcome: A population-based analysis of 88,195 patients. PLoS One.

12(e0172745)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Heidenreich PA: Healthy lifestyles and

personal responsibility. J Am Coll Cardiol. 64:1786–1788.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS,

Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, et

al: 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute

and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 42:3599–3726.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H,

Cleland JG, Coats AJ, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP,

Jankowska EA, et al: 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and

treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Kardiol Pol.

74:1037–1147. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Polish).

|

|

8

|

McMurray JJ, Packer M, Desai AS, Gong J,

Lefkowitz MP, Rizkala AR, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Solomon SD, Swedberg

K, et al: Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in

heart failure. N Engl J Med. 371:993–1004. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, Ge J,

Lam CSP, Maggioni AP, Martinez F, Packer M, Pfeffer MA, Pieske B,

et al: Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with

preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 381:1609–1620.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Duta TF, Zulfa PO, Alina M, Henira N,

Tsurayya G, Fakri F and Acharya Y: Efficacy of acetazolamide and

loop diuretics combinatorial therapy in congestive heart failure: A

meta-analysis. Narra X. 2(e124)2024.

|

|

11

|

Villaschi A, Pellegrino M, Condorelli G

and Chiarito M: Diuretic combination therapy in acute heart

failure: An updated review. Curr Pharm Des. 30:2597–2605.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Gogikar A, Nanda A, Janga LSN, Sambe HG,

Yasir M, Man RK and Mohammed L: Combination diuretic therapy with

thiazides: A systematic review on the beneficial approach to

overcome refractory fluid overload in heart failure. Cureus.

15(e44624)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Park DY, An S, Attanasio S, Jolly N,

Malhotra S, Doukky R, Samsky MD, Sen S, Ahmad T, Nanna MG and Vij

A: Network meta-analysis comparing angiotensin receptor-neprilysin

inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in heart failure with

reduced ejection fraction. Am J Cardiol. 187:84–92. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Zhang H, Huang T, Shen W, Xu X, Yang P,

Zhu D, Fang H, Wan H, Wu T, Wu Y and Wu Q: Efficacy and safety of

sacubitril-valsartan in heart failure: A meta-analysis of

randomized controlled trials. ESC Hear Fail. 7:3841–3850.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron

I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan

SE, et al: The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for

reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 372(n71)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the

National Institute of Health: Common terminology criteria for

adverse events (CTCAE) version 5.0. US Dep Heal Hum Serv, 2017.

|

|

17

|

Jørgensen L, Paludan-Müller AS, Laursen

DR, Savović J, Boutron I, Sterne JA, Higgins JP and Hróbjartsson A:

Evaluation of the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias in

randomized clinical trials: overview of published comments and

analysis of user practice in Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews.

Syst Rev. 5(80)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ and

Altman DG: Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ.

327:557–560. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Vardeny O, Miller R and Solomon SD:

Combined neprilysin and renin-angiotensin system inhibition for the

treatment of heart failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2:663–670.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Chandra A, Polanczyk CA, Claggett BL,

Vaduganathan M, Packer M, Lefkowitz MP, Rouleau JL, Liu J, Shi VC,

Schwende H, et al: Health-related quality of life outcomes in

PARAGON-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. 24:2264–2274. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Desai AS, Solomon SD, Shah AM, Claggett

BL, Fang JC, Izzo J, McCague K, Abbas CA, Rocha R and Mitchell GF:

EVALUATE-HF Investigators. Effect of sacubitril-valsartan vs

enalapril on aortic stiffness in patients with heart failure and

reduced ejection fraction: A Randomized clinical trial. JAMA.

322:1077–1084. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Gao Y, Xing C, Hao W, Zhao H, Wang L, Luan

B and Hou A: The impact of sacrubitril/valsartan on clinical

treatment and hs-cTnT and NT-ProBNP serum levels and the left

ventricular function in patients with chronic heart failure. Int

Heart J. 61:1–6. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Ghafur S, Zahid M, Sarkar H, Barman R,

Al-Mahmud A, Rahman M and Islam H: Effect of angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibitor versus valsartan on cardiac status in

patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction:

A Randomized clinical trial in Rangpur Medical College Hospital,

Bangladesh. Open J Intern Med. 10:21–34. 2020.

|

|

24

|

Halle M, Schöbel C, Winzer EB, Bernhardt

P, Mueller S, Sieder C and Lecker LSM: A randomized clinical trial

on the short-term effects of 12-week sacubitril/valsartan vs.

enalapril on peak oxygen consumption in patients with heart failure

with reduced ejection fraction: Results from the ACTIVITY-HF study.

Eur J Heart Fail. 23:2073–2082. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Kang DH, Park SJ, Shin SH, Hong GR, Lee S,

Kim MS, Yun SC, Song JM, Park SW and Kim JJ: Angiotensin receptor

neprilysin inhibitor for functional mitral regurgitation.

Circulation. 139:1354–1365. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Li BH, Fang KF, Lin PH, Zhang YH, Huang YX

and Jie H: Effect of sacubitril valsartan on cardiac function and

endothelial function in patients with chronic heart failure with

reduced ejection fraction. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 77:425–433.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Mann DL, Givertz MM, Vader JM, Starling

RC, Shah P, McNulty SE, Anstrom KJ, Margulies KB, Kiernan MS, Mahr

C, et al: Effect of treatment with sacubitril/valsartan in patients

with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction: A

Randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 7:17–25. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Mentz RJ, Ward JH, Hernandez AF, Lepage S,

Morrow DA, Sarwat S, Sharma K, Starling RC, Velazquez EJ,

Williamson KM, et al: Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in patients

with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction and worsening

heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 82:1–12. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Piepoli MF, Hussain RI, Comin-Colet J,

Dosantos R, Ferber P, Jaarsma T and Edelmann F: OUTSTEP-HF:

Randomised controlled trial comparing short-term effects of

sacubitril/valsartan versus enalapril on daily physical activity in

patients with chronic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction.

Eur J Heart Fail. 23:127–135. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Pieske B, Wachter R, Shah SJ, Baldridge A,

Szeczoedy P, Ibram G, Shi V, Zhao Z and Cowie MR: PARALLAX

Investigators and Committee members. Effect of sacubitril/valsartan

vs standard medical therapies on plasma NT-proBNP concentration and

submaximal exercise capacity in patients with heart failure and

preserved ejection fraction: The PARALLAX Randomized clinical

trial. JAMA. 326:1919–1929. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Solomon SD, Zile M, Pieske B, Voors A,

Shah A, Kraigher-Krainer E, Shi V, Bransford T, Takeuchi M, Gong J,

et al: The angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor LCZ696 in

heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: A phase 2

double-blind randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 380:1387–1395.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Tsutsui H, Momomura SI, Saito Y, Ito H,

Yamamoto K, Sakata Y, Desai AS, Ohishi T, Iimori T, Kitamura T, et

al: Efficacy and safety of sacubitril/valsartan in japanese

patients with chronic heart failure and reduced ejection

fraction-results from the PARALLEL-HF study. Circ J. 85:584–594.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Velazquez EJ, Morrow DA, DeVore AD, Duffy

CI, Ambrosy AP, McCague K, Rocha R and Braunwald E: PIONEER-HF

Investigators. Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in acute

decompensated heart failure. N Engl J Med. 380:539–548.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Voors AA, Gori M, Liu LC, Claggett B, Zile

MR, Pieske B, McMurray JJ, Packer M, Shi V, Lefkowitz MP, et al:

Renal effects of the angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor

LCZ696 in patients with heart failure and preserved ejection

fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 17:510–517. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Nasrallah D, Abdelhamid A, Tluli O,

Al-Haneedi Y, Dakik H and Eid AH: Angiotensin receptor

blocker-neprilysin inhibitor for heart failure with reduced

ejection fraction. Pharmacol Res. 204(107210)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Nielsen EE, Feinberg JB, Bu FL, Hecht

Olsen M, Raymond I, Steensgaard-Hansen F and Jakobsen JC:

Beneficial and harmful effects of sacubitril/valsartan in patients

with heart failure: A systematic review of randomised clinical

trials with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Open Hear.

7(e001294)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Hishida E and Nagata D: Angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibitor for chronic kidney disease:

Strategies for renal protection. Kidney Blood Press Res.

49:916–932. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang Y, Zhou R, Lu C, Chen Q, Xu T and Li

D: Effects of the angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitor on

cardiac reverse remodeling: Meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc.

8(e012272)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Tromp J, Ouwerkerk W, van Veldhuisen DJ,

Hillege HL, Richards AM, van der Meer P, Anand IS, Lam CSP and

Voors AA: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of

pharmacological treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection

fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 10:73–84. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

van Essen BJ, Ceelen DCH, Ouwerkerk W,

Teng TK, Tharshana GN, Hew FM, Butler J, Zannad F, Lam CS,

Ezekowitz J, et al: Pharmacologic treatment of heart failure with

reduced ejection fraction: An updated systematic review and network

meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol: Aug 30, 2025 (Epub ahead of

print).

|

|

41

|

Khan NA, Ma I, Thompson CR, Humphries K,

Salem DN, Sarnak MJ and Levin A: Kidney function and mortality

among patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. J Am Soc

Nephrol. 17:244–253. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Banerjee D, Winocour P, Chowdhury TA, De

P, Wahba M, Montero R, Fogarty D, Frankel AH, Karalliedde J, Mark

PB, et al: Management of hypertension and

renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockade in adults with

diabetic kidney disease: Association of British clinical

diabetologists and the renal association UK guideline update 2021.

BMC Nephrol. 23(9)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Murphy E: Estrogen signaling and

cardiovascular disease. Circ Res. 109:687–696. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Rudolf H, Mügge A, Trampisch HJ, Scharnagl

H, März W and Kara K: NT-proBNP for risk prediction of

cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality: The getABI-study.

Int J Cardiol Hear Vasc. 29(100553)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Greenberg B: Angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibition (ARNI) in heart failure. Int J Hear

Fail. 2:73–90. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Bayes-Genis A, Barallat J and Richards AM:

A test in context: Neprilysin: Function, inhibition, and biomarker.

J Am Coll Cardiol. 68:639–653. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Sauer AJ, Cole R, Jensen BC, Pal J, Sharma

N, Yehya A and Vader J: Practical guidance on the use of

sacubitril/valsartan for heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 24:167–176.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Chandra A, Lewis EF, Claggett BL, Desai

AS, Packer M, Zile MR, Swedberg K, Rouleau JL, Shi VC, Lefkowitz

MP, et al: Effects of sacubitril/valsartan on physical and social

activity limitations in patients with heart failure: A secondary

analysis of the PARADIGM-HF trial. JAMA Cardiol. 3:498–505.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Park SK, Hong SH, Kim H, Kim S and Lee EK:

Cost-Utility analysis of sacubitril/valsartan use compared with

standard care in chronic heart failure patients with reduced

ejection fraction in South Korea. Clin Ther. 41:1066–1079.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Gan L, Lyu X, Yang X, Zhao Z, Tang Y, Chen

Y, Yao Y, Hong F, Xu Z, Chen J, et al: Application of angiotensin

receptor-neprilysin inhibitor in chronic kidney disease patients:

Chinese expert consensus. Front Med (Lausanne).

9(877237)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Nagata D, Hishida E and Masuda T:

Practical strategy for treating chronic kidney disease

(CKD)-Associated with hypertension. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis.

13:171–178. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

52

|

Nakano Y, Suzuki Y, Onishi T, Ando H,

Matsuo Y, Suzuki W, Kuno S, Ohashi H, Waseda K, Takahashi H, et al:

Predictors of hypotension after angiotensin receptor-neprilysin

inhibitor administration in patients with heart failure. Int Heart

J. 65:658–666. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|