Introduction

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a

critical pathological feature in fibrosis-related diseases,

including intestinal fibrosis and pulmonary fibrosis (1), and represents a highly dynamic,

multi-stage process regulated by multiple signaling pathways that

promote acquisition of the mesenchymal phenotype. In detail,

external stimulation of signaling pathways, including TGFβ/Wnt,

triggers a transcriptional program during EMT that induces the

expression of the E-cadherin transcriptional repressor SNAIL, which

promotes cell migration, invasiveness and fibrosis. The core

process of EMT is characterized by epithelial cells losing polarity

and intercellular connections to acquire a mesenchymal phenotype

with enhanced mesenchymal traits such as collagen, fibronectin

(FN), vimentin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) expression, as

well as reduced epithelial adhesion protein E-cadherin expression

(2-4).

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been shown to have anticancer

activity against several types of cancer. For instance, omeprazole

destroyed cyclic AMP response element-binding protein

(CREB)-binding protein (CBP)/p300-mediated SNAIL protein

acetylation to induce its degradation, leading to the inhibition of

EMT in cancer cells (5), while

pantoprazole was shown to inactivate the Wnt/β-catenin signaling

pathway to block the EMT process (6-8).

Moreover, rabeprazole was shown to reduce resistance to

temozolomide in glioma via EMT inhibition (9). Despite the fact that previous studies

showed that PPIs can inhibit EMT, to date, there is no direct

evidence fully describing the role of rabeprazole in fibrosis.

It is well known that SMAD family member 3 (SMAD3)

is an important mediator of TGFβ-induced fibrosis or EMT, which can

crosstalk with other pathways to modulate pathological progression.

For example, Y-box binding protein 1, a member of the

DNA/RNA-binding protein family, was reported to upregulate SMAD7

transcription or interact with SMAD3 to overcome the effect of TGFβ

stimulation (10,11). In addition, transcriptional

intermediary factor 1γ (TIF1γ; also known as TRIM33), a direct

target of CREB, interacted with SMAD3 to antagonize SMAD3-induced

fibrosis (12), which was in line

with studies reporting on the anti-EMT function of TIF1γ (13,14).

Notably, the phosphorylation of SMAD3 linker (at the ser204,

ser208, ser213 and Thr179 residues) was reported to accelerate

nuclear shuttle of cytoplasmic SMAD3, which decreased the

accessibility of non-phosphorylated SMAD3 to membrane-anchored TGFβ

receptor type I (TGFβRI), leading to inhibition of SMAD3C

phosphorylation (15,16). Moreover, TIF1γ has been shown to act

as a SMAD4 ubiquitin ligase, either dissociating SMAD2/SMAD3-SMAD4

complexes or mediating polyubiquitylation and degradation of SMAD4,

thereby promoting competitive binding of SMAD2/3 through the MH2

domain (17). In addition, TIF1γ

was reported to occupy SMAD-binding elements to prevent

SMAD2/3-mediated DNA binding (12).

Based on these findings, it is hypothesized that this TIF1γ/SMAD3

complex may have an inhibitory effect on SMAD3 phosphorylation and

nuclear translocation to ablate SMAD3-mediated gene transcription.

However, the critical phosphorylation site of SMAD3 in response to

the TIF1γ/SMAD3 complex remain unclear.

Rabeprazole, a classical PPI, was previously

recognized to be involved in the modulation of inflammation

(18,19), barrier function (20,21)

and metabolism (22). The aim of

the present study was to identify the novel biological function of

rabepraozole in fibrosis and reveal the possible relationship

between TIF1γ and SMAD3 through immunofluorescence (IF),

immunoprecipitation (IP) and luciferase assays. providing

significant implications for understanding the function of

rabeprazole.

Materials and methods

Chemical reagents

Gibco™ BASIC DMEM (cat. no. C11995500BT) and fetal

bovine serum (FBS) (Premium Plus; cat. no. A5669701) were purchased

from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. Rabeprazole (cat. no. HY-B0656)

was purchased from MedChemExpress. Lipo8000™ transfection reagent

(cat. no. C0533), nuclear and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit

(cat. no. P0028) and cell lysis buffer for western blotting and

immunoprecipitation (IP; cat. no. P0013) were purchased from

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology. shRNA-TIF1γ plasmids and TIF1γ

promoter plasmid, were constructed and obtained from Youbio Biotech

Co., Ltd. Protein A/G magnetic beads (cat. no. B23202) were

purchased from Selleck Chemicals. EZ-press RNA Purification Kit

(cat. no. B0004D), 4X EZscript Reverse Transcription Mix II (with

gDNA Remover; cat. no. EZB-RT2G) and 2X Color SYBR Green qPCR

Master Mix (cat. no. A0012) were purchased from EZBioscience. A

dual-luciferase reporter assay system (cat. no. E1910) was obtained

from Promega Corporation. Antibodies including α-SMA specific

monoclonal antibody (mAb) (cat. no. 67735-1-Ig), FN mAb (cat. no.

66042-1-Ig), vimentin polyclonal antibody (pAb) (cat. no.

10366-1-AP), collagen type I (Col1a1) mAb (cat. no. 67288-1-Ig),

SMAD3 mAb (cat. no. 66516-1-Ig), lamin A/C pAb (cat. no.

10298-1-AP) and α-tubulin mAb (cat. no. 66031-1-Ig) were purchased

from Proteintech Group, Inc. TIF1γ mouse mAb (cat. no. YM1108),

SMAD3 (phospho Ser204) rabbit pAb (cat. no. YP0363), SMAD3 (phospho

Ser213) rabbit pAb (cat. no. YP0364), SMAD3 (phospho Thr179) rabbit

pAb (cat. no. YP0745) and SMAD3 (phospho Ser208) rabbit pAb (cat.

no. YP0746) were purchased from Immunoway Biotechnology Co., Ltd.;

peroxidase affiniPure™ goat anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) (cat. no.

111-035-003) and peroxidase-conjugated affiniPure goat anti-mouse

IgG (H+L) (cat. no. 115-035-003) were obtained from Jackson

ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc.

Cell culture, treatment and

transfection

Gastric epithelial cells, including AGS (cat. no.

JNO-H0238) and GES-1 (cat. no. JNO-H0240), were purchased from

Guangzhou Jennio Biotech Co. Ltd. and maintained in DMEM medium

containing 10% FBS, 100 mg/ml streptomycin and 100 U/ml penicillin.

Rabeprazole was dissolved in DMSO and stored at -80˚C. The

concentration of rabeprazole used was 100 µM. For cell transfection

of each well in a 6-well plate, when cells reached 50% confluence,

2 µg plasmids were gently mixed with 4 µl Lipo8000 transfection

reagent in 125 µl Opti-MEM® medium at room temperature

according to the manufacturer's instructions. Subseqently, the mix

was added into each well for 48 h. pLVX-shRNA-PURO plasmids (cat.

no. L28550-L28552) targeting TIF1γ (also known as TRIM33) were

constructed and purchased from Youbio Biotech Co., Ltd.

Reverse transcription-quantitative

(RT-q)PCR analysis

Following treatment, total RNA was extracted from

106 cells per group with the EZ-press RNA purification

kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was

synthesized using 4X EZscript reverse transcription mix II (with

gDNA Remover) to analyze the indicated gene expression using the 2X

color SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix. The following primer pairs were

used for qPCR: FN forward, 5'-TCAGCTTCCTGGCACTTCTG-3' and reverse,

5'-TCTTGTCCTACATTCGGCGG-3'; vimentin forward,

5'-GGACCAGCTAACCAACGACA-3' and reverse, 5'-AAGGTCAAGACGTGCCAGAG-3';

COl1a1 forward, 5'-TCGGAGGAGAGTCAGGAAGG-3' and reverse,

5'-CCCGGTGACACATCAAGACA-3'; α-SMA forward,

5'-CTATGAGGGCTATGCCTTGCC-3' and reverse,

5'-GCTCAGCAGTAGTAACGAAGGA-3'; TIF1γ forward,

5'-AGCACTACTATACAGCAAGCGA-3' and reverse,

5'-CAGAAGGTGGGATCACAATGG-3'; β-actin forward,

5'-CTTCGCGGGCGACGAT-3' and reverse,

5'-CCACATAGGAATCCTTCTGACC-3'.

Immunoblotting analysis

As described in Niu et al (23), after treatment, cells were harvested

to extract the total protein using cell lysis buffer for western

blotting and IP. Briefly, 15 µg total protein was separated by 10%

SDS-PAGE and transferred into polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)

membranes. The protein bands were blocked with PBST (0.5% Tween-20)

(cat. no. BL345A) containing 2% skim milk (cat. no. BS102) plus 3%

BSA (cat. no. BS114; all from Biosharp) for 1 h at room

temperature. After washing with PBST (0.5% Tween-20), the membranes

were incubated with the primary antibodies with a dilution of

1:2,000 overnight at 4˚C. Following incubation with primary

antibodies, the membranes were incubated with the secondary

antibodies at 1:2,000 for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, after

washing with PBST, the bands were visualized and captured using

Chemiluminescence imaging instrument (MiniChemi 610, Sinsage) after

incubation with an ECL chemiluminescent substrate (cat. no.

NEL105001EA; Revvity, Inc.). the density was quantified by Image J

software (version: 1.8.0_351; National Institutes of Health) and

normalized to internal control.

Subcellular isolation

According to the manufacturer's instructions, after

serum starvation and when the cells reached 80% confluence, cells

were treated with or without rabeprazole for 1 h at 37˚C and the

cytosolic and nuclear fractions were extracted using the nuclear

and cytoplasmic protein extraction kit aforementioned. Western

blotting was performed to analyze the protein expression.

IP

As described in Li et al (24), when cells reached 80% confluence in

a 6-cm dish, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM for 18 h.

The cells were incubated with or without rabeprazole for 1 h, after

which the medium was removed and the cells were washed with

ice-cold PBS. The cells were then incubated with cell lysis buffer

for western blotting and immunoprecipitation for 10 min on ice,

scraped, and transferred into 1.5-ml tubes for an additional 30 min

of lysis on a rotator at 4˚C. The lysates were centrifuged at

12,000 x g for 2 min at 4˚C to collect the supernatant. A total of

10 µl of anti-SMAD3 antibody was added to the supernatant and

incubated overnight at 4˚C. Subsequently, 20 µl of protein A/G

magnetic beads (cat. no. B23202; Selleck Chemicals) were added and

incubated for 1 h at 4˚C to pull down the immune complexes. After

three washes with cell lysis buffer for western blotting and IP

(cat. no. P0013), the complexes were eluted with SDS loading buffer

and boiled at 100˚C for 10 min for immunoblotting analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining

Cells were digested and reseeded into an 8-well

slide overnight and incubated at 37˚C with or without rabeprazole

for 1 h. After fixation with 3% PFA (cat. no. BL3786A) for 10 min

at room temperature and permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100

(cat. no. BL935B; both from Biosharp; Beijing Labgic Technology

Co., Ltd.) for 5 min at 4˚C, cells were blocked with 3% milk at

room temperature for 1 h. The incubation with anti-SMAD3 at a

dilution of 1:400 was conducted overnight at 4˚C. Subsequently,

further incubation was performed for another 1 h at room

temperature with goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (AbFluor 594) (cat. no.

RS3608; Immunoway Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) at a dilution of 1:300.

After washing and staining the nuclei with DAPI buffer (cat. no.

C1006; Beyotime Insitute of Biotechnology) for 5 min at room

temperature, the coverslips were covered with glass slides. Stained

cells were visualized using a laser scanning fluorescent microscope

(Leica Microsystems GmbH).

Dual luciferase reporter analysis

Briefly, the reporter plasmid containing 0.5 µg

TIF1γ promoter in PGL3-Basic (cat. no. 56089) and 10 ng pRL-TK

Renilla luciferase plasmid (cat. no. V1079; both from Youbio

Biotech Co., Ltd.) at a ratio of 50:1 were co-transfected into

cells in a 24-well plate at room temperature. Cells were maintained

for 24 h with complete medium in a cell incubator using Lipo8000

transfection reagent (C0533; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology),

followed by incubation with 100 µM rabeprazole for another 24 h in

serum-free medium at 37˚C. An equal precentage of DMSO was used as

the vehicle control. Each group consisted of three replicates. The

cells were lysed with 100 µl Passive Lysis Buffer, and samples were

collected and measured using a plate-reading luminometer to

calculate relative light units determined by the ratio of

firely/Renilla to reflect TIF1γ transactivation, using the

dual-luciferase reporter assay system (cat. no. E1910; Promega

Corporation) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism 10.0

(Dotmatics). Statistical comparisons between two groups were

performed using the unpaired Student's t-test. One-sample t-test

was conducted to analyze the RT-q PCR results. Statistical

comparisons among three groups were performed using one-way ANOVA

followed by the Dunnett's post hoc test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

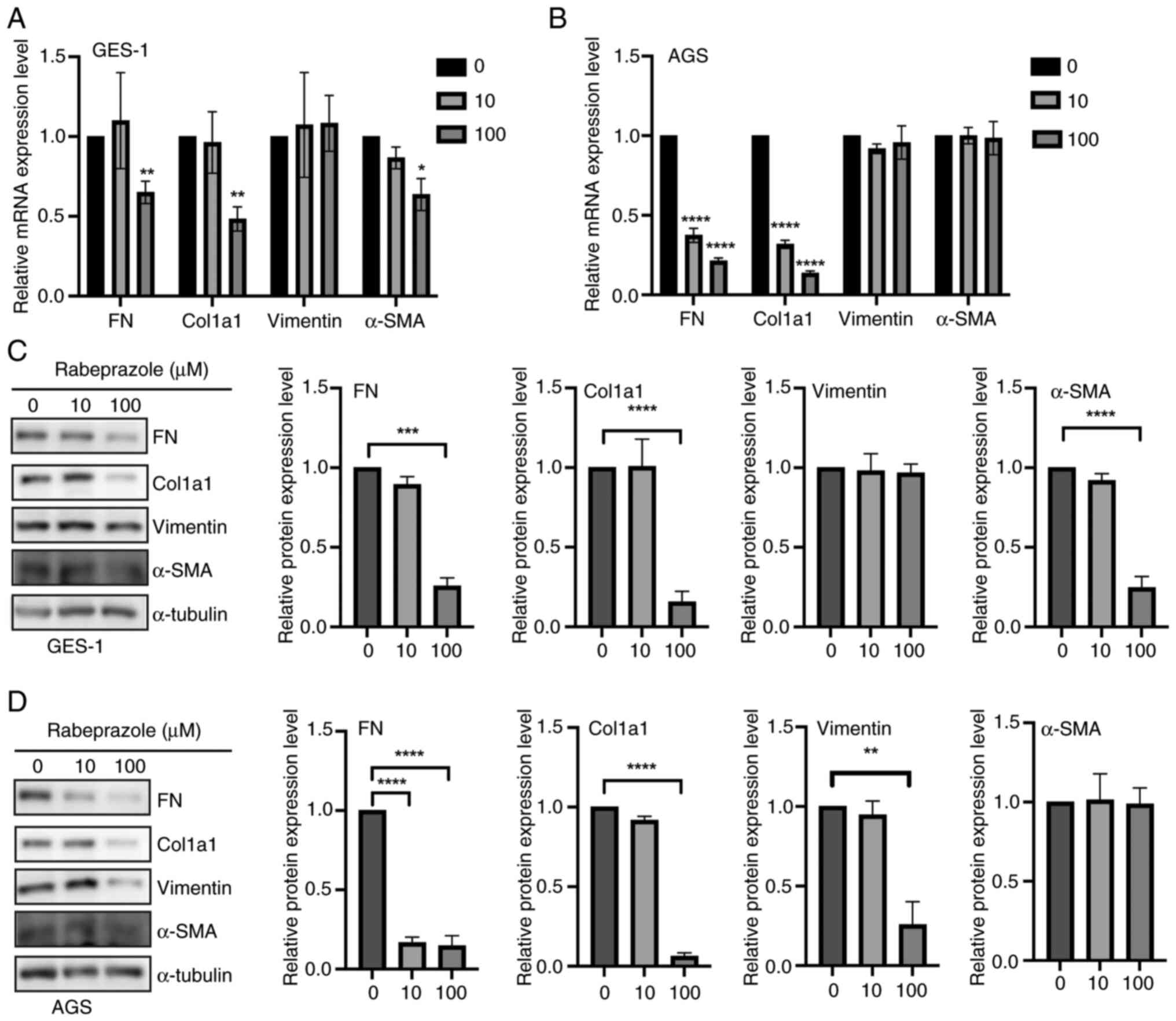

Rabeprazole suppresses fibrosis in

gastric epithelial cells

AGS and GES-1 gastric epithelial cells were employed

as in vitro models to assess the impact of rabeprazole on

fibrotic processes. The expression levels of genes involved in

fibrosis were analyzed in gastric epithelial cells after incubation

for 24 h with rabeprazole at 10 and 100 µM. Compared with the

control group (Fig. 1A and B), a significant fibrosis inhibition was

observed in GES-1 and AGS cells in response to 100 µM rabeprazole

stimulation as indicated by the largely decreased FN and Col1a1

mRNA levels, whereas no significant change was observed in vimentin

mRNA expression regardless of treatment with 10 and 100 µM.

Moreover, western blotting was performed to detect the indicated

protein expression levels, and quantification of the indicated

proteins revealed that rabeprazole treatment at 100 µM induced a

downregulation of FN and Col1a1 expression in GES-1 and AGS cells,

respectively, while no influence on vimentin expression was

observed with treatment at 10 µM. In addition, the expression of

α-SMA was downregulated in GES-1 cells (Fig. 1C and D). Taken together, these findings

indicated that rabeprazole has a potent suppressive effect in

inhibiting fibrosis.

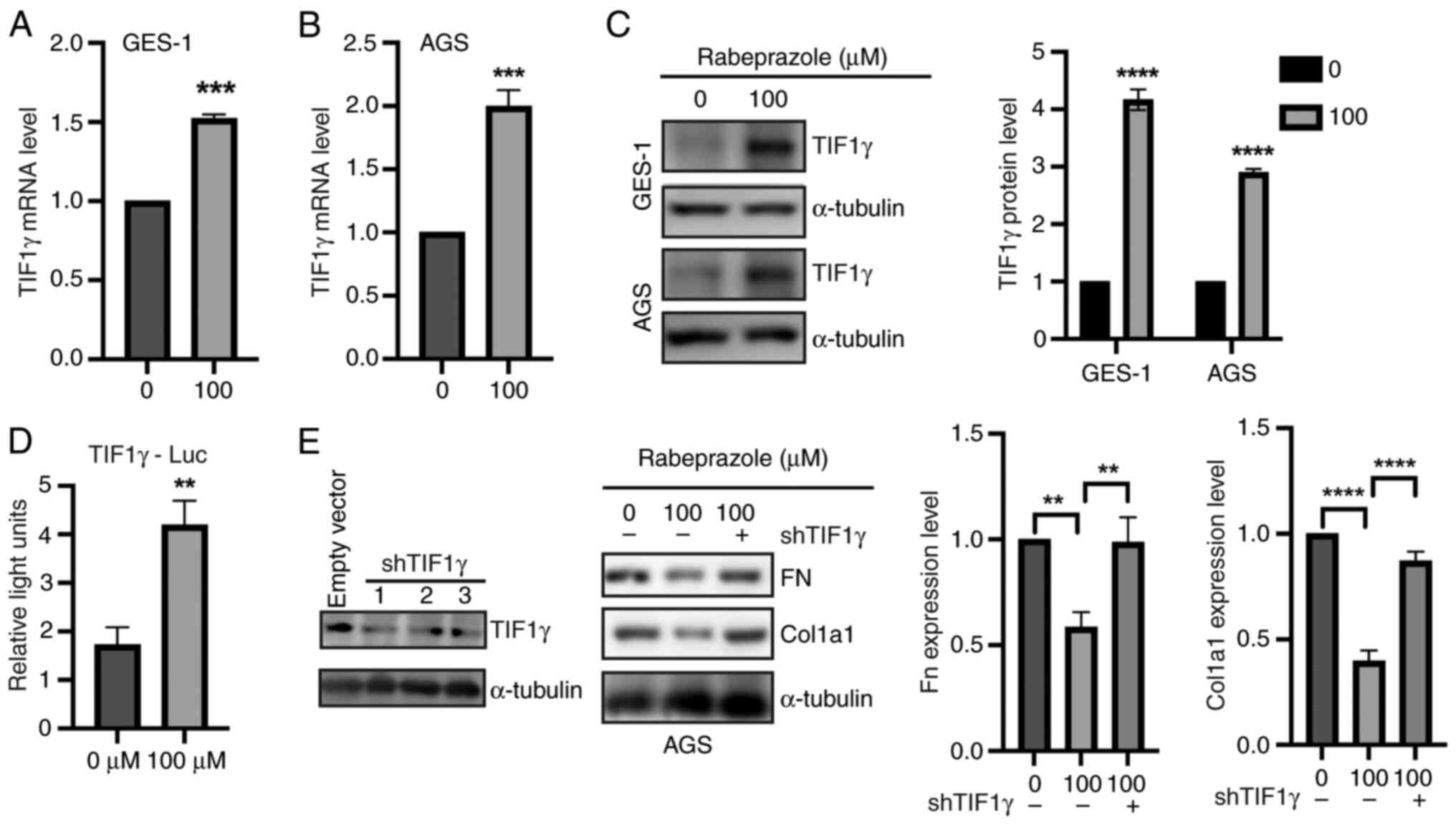

TIF1γ is essential for the EMT

inhibition mediated by rabeprazole

Since TIF1γ was reported to suppress extracellular

matrix (ECM) production by inhibiting TGF-β1 transcriptional

response (25-27),

the present study focused on investigating the possible effect of

rabeprazole on TIF1γ expression in gastric epithelial cells. Based

on the previous results, treatment with 100 µM rabeprazole was

selected for further experiments. Compared with the control group

(Fig. 2A and B), the mRNA levels of TIF1γ were

significantly increased in AGS and GES-1 cells in response to

rabeprazole treatment. In addition, the protein expression level of

TIF1γ was significantly enhanced by rabeprazole treatment (Fig. 2C). Moreover, dual luciferase

reporter experiments further revealed that TIF1γ transactivation

was significantly increased in response to rabeprazole treatment

(Fig. 2D). Most importantly,

depletion of TIF1γ expression by shRNA plasmid-targeted TIF1γ could

rescue the effect of rabeprazole on FN and Col1a1 protein

expression (Fig. 2E). These results

indicated that rabeprazole inhibited the ECM through upregulation

of TIF1γ expression.

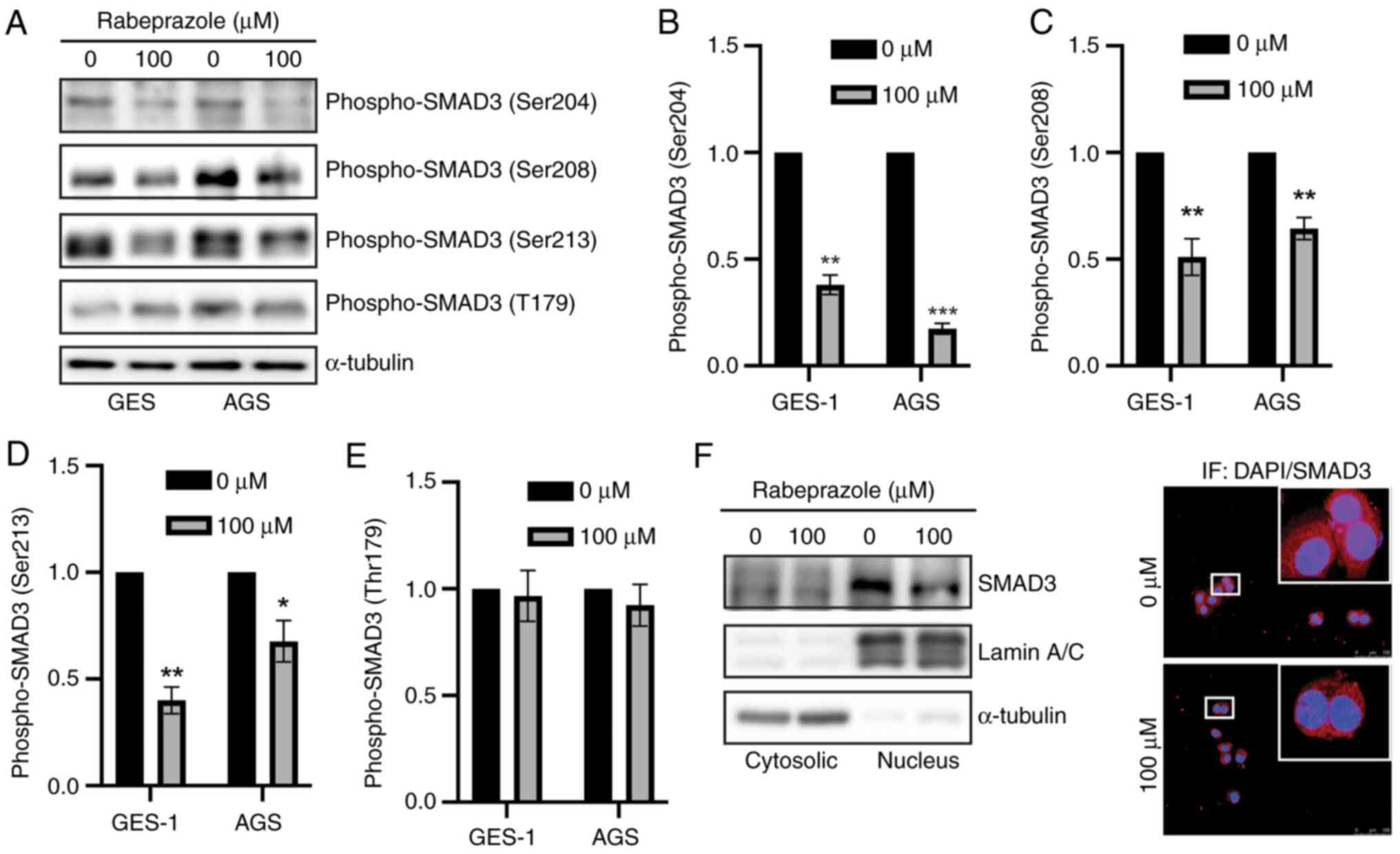

Rabeprazole inhibits SMAD3

phosphorylation and nuclear translocation

It is well known that SMAD3 phosphorylation, whether

in the linker domain or at the C-terminus, promotes SMAD3 nuclear

translocation to initiate gene transcription (16). Notably, a reciprocal inhibition

existed between phosphorylation of the SMAD3 linker domain and

C-terminus, which was attributed to the fact that SMAD3

phosphorylation at the linker domain could induce SMAD3 nuclear

shuttling, thereby inhibiting the accessibility of

non-phosphorylated SMAD3 to membrane-anchored TGFβRI (28).

The present results demonstrated that rabeprazole

attenuated fibrosis, prompting an exploration of the influence of

rabeprazole on SMAD3 activation. Through immunoblotting

quantification, it was found that, in gastric epithelial cells,

rabeprazole treatment led to a downregulation of SMAD3

phosphorylation at Ser204, Ser208 and Ser213, while no significant

changes were observed at Thr179 of the SMAD3 linker domain

(Fig. 3A-E). Moreover, subcellular

fraction combined with immunofluorescence analysis further showed

that the nuclear SMAD3 level was reduced in response to rabeprazole

(Fig. 3F). Overall, rabeprazole

inhibited SMAD3 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation.

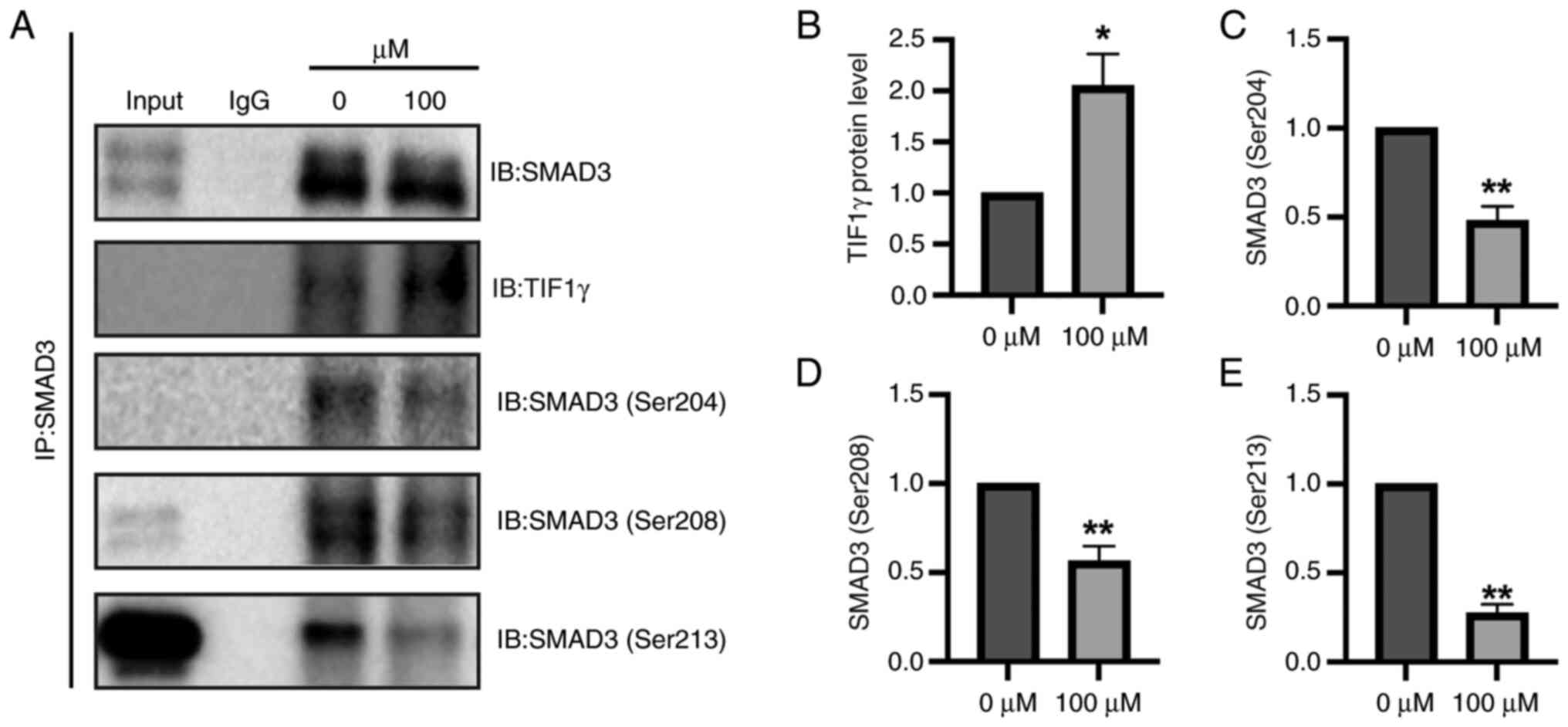

Rabeprazole disrupts the interaction

between SMAD3 and TIF1γ

The present study aimed to elucidate the mechanism

by which rabeprazole influences fibrotic processes. SMAD3 was

identified as a key transcriptional regulator of Col1a1,

contributing to fibrosis via TGFβ-dependent signaling pathways

(29). Notably, TIF1γ was shown to

mitigate ECM accumulation by interacting with SMAD3, thereby

attenuating fibrotic responses (12). These findings suggest that SMAD3 may

play a pivotal role in the antifibrotic effects mediated by

rabeprazole-induced TIF1γ activity. On this basis, the present

study aimed to explore the possible relationship between SMAD3 and

TIF1γ. As shown in Fig. 4A,

endogenous SMAD3 interacted with TIF1γ, and this interaction was

enhanced in response to rabeprazole. In line with this,

immunoprecipitation assays further revealed that rabeprazole

treatment led to a significantly enhanced SMAD3/TIF1γ complex,

which in turn further inhibited SMAD3 linker phosphorylation,

including Ser204, Ser208 and Ser213 (Fig. 4A-E), consistent with our other

research work showing that overexpression of TIF1γ led to

inhibition of SMAD3 phosphorylation (Li et al unpublished

data). These results indicated that rabeprazole treatment led to an

antifibrotic TIF1γ/SMAD3 complex.

Discussion

Fibrosis is a common pathological change in various

diseases, including chronic hepatitis B-related liver diseases

(30) and gastrointestinal-related

diseases (31). Previous studies

demonstrated that rabeprazole has various biological functions

(9,29,32,33),

however, the present study further revealed a novel mechanism of

rabeprazole in fibrosis. The present study found that rabeprazole

exerted an inhibitory effect on fibrosis, which was attributed to

enhanced TIF1γ expression, while enhanced TIF1γ expression could

inhibit SMAD3 linker phosphorylation. Further analysis showed that

TIF1γ interacted with SMAD3, leading to suppression of SMAD3

signaling characterized by decreased phosphorylation of SMAD3

linker at Ser213, Ser204 and Ser208, and rabeprazole treatment

enhanced this interaction between TIF1γ and SMAD3 to aggravate

SMAD3 linker phosphorylation inhibition to alleviate fibrosis. This

finding not only enriched the knowledge on the biological function

of rabeprazole, but also the provided a possible therapeutic

strategy for fibrosis.

Rabeprazole, a well-known PPI, was reported to

induce M2-type adipose tissue macrophages, alleviating chronic

inflammation (18), and to improve

the survival rate and ameliorate pathological damage in

Clostridium perfringens or perfringolysin O (PFO)-treated

Galleria mellonella (34).

Moreover, rabeprazole was shown to have anti-Trypanosoma

cruzi activity by targeting cellular triosephosphate isomerase

(35). Rabeprazole has been

demonstrated to destroy gastric epithelial barrier function in

vivo and in vitro (20,36),

while exhibiting nephroprotective effects through inhibition of

organic cation transporter 2(37)

as well as promoting vascular impairment through hypoxia-inducible

factor 1-α (38). The present study

further investigated the antifibrotic function of rabeprazole. In

previous studies, rabeprazole was demonstrated to induce enhanced

TIF1γ expression, leading to suppression of TGFβ signaling.

Notably, phosphorylation of TIF1γ at Tyr-524, Tyr-610, and Tyr-1048

was found to destroy the complex between TIF1γ and SMAD3, which

could enhance TGFβ signaling (17,39).

Therefore, further investigation was required to reveal the

mechanism through which rabeprazole regulated TIF1γ expression.

However, the influence of rabeprazole on TIF1γ phosphorylation

remains unclear and will require further investigations. In

addition, the present study lacked in vivo experiments

confirming the possible role of rabeprazole in fibrosis.

Furthermore, phosphorylation of SMAD3, at both the linker domain

and C-terminus, is a critical event for the initiation of fibrosis

or EMT (40). Phosphorylation of

SMAD3 at Ser204, Ser208, and Ser213 was observed to be

significantly reduced in response to rabeprazole stimulation, and

this phenomenon was attributed to the formation of an enhanced

complex between TIF1γ and SMAD3 caused by rabeprazole. However, the

specific domain and phosphorylation status of TIF1γ that facilitate

its interaction with SMAD3, particularly under rabeprazole

treatment, remain unclear. In addition, considering that the

disease and tumor microenvironment are enriched with diverse

inflammatory and immune cells, including macrophages and

fibroblasts, our future work will employ progressively complex

in vitro systems, ranging from spheroid and organoid-based

co-cultures to air-liquid interface organoids and microfluidic

organoid-on-a-chip platforms. These models will be used to

investigate whether rabeprazole plays a role in remodeling the

cellular microenvironment (41,42).

In summary, the present study revealed a novel

antifibrotic role of rabeprazole in vitro, mediated through

the formation of a TIF1γ-SMAD3 complex. These findings offer novel

insights into the biological functions of rabeprazole and suggest

its potential as an alternative therapeutic strategy for

fibrosis-related diseases.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by the Science and

Technology Project in the Field of Social Development of Zhuhai

(grant. no. 2220004000296).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study are included

in the figures and/or tables of this article.

Authors' contributions

LL, XT and JC designed the experiments. LL, ZL and

LF performed the experiments and data collection. LL, YC and XT

analyzed the data and generated the figures. LL, XT and JC drafted

the manuscript and revised the manuscript. LL and XT confirm the

authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and approved the

final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Luo L, Zhang W, You S, Cui X, Tu H, Yi Q,

Wu J and Liu O: The role of epithelial cells in fibrosis:

Mechanisms and treatment. Pharmacol Res. 202(107144)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Hanahan D and Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of

cancer: The next generation. Cell. 144:646–674. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY and Nieto

MA: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease.

Cell. 139:871–890. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Kalluri R and Weinberg RA: The basics of

epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 119:1420–1428.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Li Y, Ren BX, Li HM, Lu T, Fu R and Wu ZQ:

Omeprazole suppresses aggressive cancer growth and metastasis in

mice through promoting Snail degradation. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

43:1816–1828. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Zhang B, Ling T, Zhaxi P, Cao Y, Qian L,

Zhao D, Kang W, Zhang W, Wang L, Xu G and Zou X: Proton pump

inhibitor pantoprazole inhibits gastric cancer metastasis via

suppression of telomerase reverse transcriptase gene expression.

Cancer Lett. 452:23–30. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Feng S, Zheng Z, Feng L, Yang L, Chen Z,

Lin Y, Gao Y and Chen Y: Proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole

inhibits the proliferation, self-renewal and chemoresistance of

gastric cancer stem cells via the EMT/β-catenin pathways. Oncol

Rep. 36:3207–3214. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Zhang B, Yang Y, Shi X, Liao W, Chen M,

Cheng AS, Yan H, Fang C, Zhang S, Xu G, et al: Proton pump

inhibitor pantoprazole abrogates adriamycin-resistant gastric

cancer cell invasiveness via suppression of Akt/GSK-β/β-catenin

signaling and Epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Lett.

356:704–712. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Babu D, Mudiraj A, Yadav N, Y B V K C,

Panigrahi M and Prakash Babu P: Rabeprazole has efficacy per se and

reduces resistance to temozolomide in glioma via EMT inhibition.

Cell Oncol (Dordr). 44:889–905. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Dooley S, Said HM, Gressner AM, Floege J,

En-Nia A and Mertens PR: Y-box protein-1 is the crucial mediator of

antifibrotic interferon-gamma effects. J Biol Chem. 281:1784–1795.

2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Higashi K, Inagaki Y, Fujimori K, Nakao A,

Kaneko H and Nakatsuka I: Interferon-gamma interferes with

transforming growth factor-beta signaling through direct

interaction of YB-1 with Smad3. J Biol Chem. 278:43470–43479.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Lee EJ, Hwang I, Lee JY, Park JN, Kim KC,

Kim I, Moon D, Park H, Lee SY, Kim HS, et al: Hepatic stellate

cell-specific knockout of transcriptional intermediary factor 1γ

aggravates liver fibrosis. J Exp Med. 217(e20190402)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Ikeuchi Y, Dadakhujaev S, Chandhoke AS,

Huynh MA, Oldenborg A, Ikeuchi M, Deng L, Bennett EJ, Harper JW,

Bonni A and Bonni S: TIF1γ protein regulates epithelial-mesenchymal

transition by operating as a small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO)

E3 ligase for the transcriptional regulator SnoN1. J Biol Chem.

289:25067–25078. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Su Z, Sun Z, Wang Z, Wang S, Wang Y, Jin

E, Li C, Zhao J, Liu Z, Zhou Z, et al: TIF1γ inhibits lung

adenocarcinoma EMT and metastasis by interacting with the TAF15/TBP

complex. Cell Rep. 41(111513)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Matsuzaki K: Smad3 phosphoisoform-mediated

signaling during sporadic human colorectal carcinogenesis. Histol

Histopathol. 21:645–662. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Ooshima A, Park J and Kim SJ:

Phosphorylation status at Smad3 linker region modulates

transforming growth factor-β-induced Epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and cancer progression. Cancer Sci. 110:481–488.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

He W, Dorn DC, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst

P, Moore MA and Massague J: Hematopoiesis controlled by distinct

TIF1gamma and Smad4 branches of the TGFbeta pathway. Cell.

125:929–941. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Li Y, Hao J, Kong X, Yuan W, Shen Y, Hui Z

and Lu X: Rabeprazole mitigates obesity-induced chronic

inflammation and insulin resistance associated with increased

M2-type macrophage polarization. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis

Dis. 1870(167142)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chen SQ, Hu BF, Yang YR, He Y, Yue L, Guo

D, Wu TN, Feng XW, Li Q, Zhang W and Wen JG: The protective effect

of rabeprazole on cisplatin-induced apoptosis and necroptosis of

renal proximal tubular cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

612:91–98. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Yang F, Li L, Zhou Y, Pan W, Liang X,

Huang L, Huang J, Cheng Y, Geng L, Xu W and Gong S: Rabeprazole

destroyed gastric epithelial barrier function through

FOXF1/STAT3-mediated ZO-1 expression. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol.

50:516–526. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Son M, Park IS, Kim S, Ma HW, Kim JH, Kim

TI, Kim WH, Han J, Kim SW and Cheon JH: Novel Potassium-competitive

acid blocker, tegoprazan, protects against colitis by improving gut

barrier function. Front Immunol. 13(870817)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Zhou Y, Chen S, Yang F, Zhang Y, Xiong L,

Zhao J, Huang L, Chen P, Ren L, Li H, et al: Rabeprazole suppresses

cell proliferation in gastric epithelial cells by targeting

STAT3-mediated glycolysis. Biochem Pharmacol.

188(114525)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Niu R, Lan J, Liang D, Xiang L, Wu J,

Zhang X, Li Z, Chen H, Geng L, Xu W, et al: GZMA suppressed

GPX4-mediated ferroptosis to improve intestinal mucosal barrier

function in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Commun Signal.

22(474)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Li P, Wu Y, Deng Z, Samad A, Xi Y, Song J,

Zhang Y, Li J, Zhou YA, Xiong Q and Wu C: Two novel SH3TC2

mutations predispose to Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 4C by

mistargeting away from TFRC. Cell Signal.

130(111669)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Hesling C, Fattet L, Teyre G, Jury D,

Gonzalo P, Lopez J, Vanbelle C, Morel AP, Gillet G, Mikaelian I and

Rimokh R: Antagonistic regulation of EMT by TIF1γ and Smad4 in

mammary epithelial cells. EMBO Rep. 12:665–672. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Qi G, Lu G, Yu J, Zhao Y, Wang C, Zhang H

and Xia Q: Up-regulation of TIF1γ by valproic acid inhibits the

epithelial mesenchymal transition in prostate carcinoma through

TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol.

860(172551)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Yin X, Xu C, Zheng X, Yuan H, Liu M, Qiu Y

and Chen J: SnoN suppresses TGF-β-induced epithelial-mesenchymal

transition and invasion of bladder cancer in a TIF1γ-dependent

manner. Oncol Rep. 36:1535–1541. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sun YM, Wu Y, Li GX, Liang HF, Yong TY, Li

Z, Zhang B, Chen XP, Jin GN and Ding ZY: TGF-β downstream of Smad3

and MAPK signaling antagonistically regulate the viability and

partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition of liver progenitor

cells. Aging (Albany NY). 16:6588–6612. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zheng M, Li H, Sun L, Cui S, Zhang W, Gao

Y and Gao R: Calcipotriol abrogates TGF-β1/pSmad3-mediated collagen

1 synthesis in pancreatic stellate cells by downregulating RUNX1.

Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 491(117078)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Xiao J, Liu H, Yao J, Yang S, Shen F, Bu

K, Wang Z, Liu F, Xia N and Yuan Q: The characterization of serum

proteomics and metabolomics across the cancer trajectory in chronic

hepatitis B-related liver diseases. View: 5, 2024.

|

|

31

|

Ito T and Kayama H: Roles of fibroblasts

in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases and

IBD-associated fibrosis. Int Immunol. 37:377–392. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Xie J, Liang X, Xie F, Huang C, Lin Z, Xie

S, Yang F, Zheng F, Geng L, Xu W, et al: Rabeprazole suppressed

gastric intestinal metaplasia through activation of GPX4-mediated

ferroptosis. Front Pharmacol. 15(1409001)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Gu M, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Ma H, Yao H and Ji

F: Rabeprazole exhibits antiproliferative effects on human gastric

cancer cell lines. Oncol Lett. 8:1739–1744. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Wang G, Liu Y, Deng L, Liu H, Deng X, Li

Q, Feng H, Guo Z and Qiu J: Repurposing rabeprazole sodium as an

anti-Clostridium perfringens drug by inhibiting

perfringolysin O. J Appl Microbiol. 134:2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Garcia-Torres I, De la Mora-De la Mora I,

Lopez-Velazquez G, Cabrera N, Flores-López LA, Becker I,

Herrera-López J, Hernández R, Pérez-Montfort R and Enríquez-Flores

S: Repurposing of rabeprazole as an anti-Trypanosoma cruzi

drug that targets cellular triosephosphate isomerase. J Enzyme

Inhib Med Chem. 38(2231169)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Takashima S, Tanaka F, Kawaguchi Y, Usui

Y, Fujimoto K, Nadatani Y, Otani K, Hosomi S, Nagami Y, Kamata N,

et al: Proton pump inhibitors enhance intestinal permeability via

dysbiosis of gut microbiota under stressed conditions in mice.

Neurogastroenterol Motil. 32(e13841)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Sharaf G, E ME and El-Sayed EK: Augmented

nephroprotective effect of liraglutide and rabeprazole via

inhibition of OCT2 transporter in cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity

in rats. Life Sci. 321(121609)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Evans CE, Peng Y, Zhu MM, Dai Z, Zhang X

and Zhao YY: Rabeprazole promotes vascular repair and resolution of

Sepsis-induced inflammatory lung injury through HIF-1α. Cells.

11(1425)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Yuki R, Tatewaki T and Yamaguchi N, Aoyama

K, Honda T, Kubota S, Morii M, Manabe I, Kuga T, Tomonaga T and

Yamaguchi N: Desuppression of TGF-β signaling via nuclear

c-Abl-mediated phosphorylation of TIF1γ/TRIM33 at Tyr-524, -610,

and -1048. Oncogene. 38:637–655. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Matsuzaki K: Smad phospho-isoforms direct

context-dependent TGF-β signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.

24:385–399. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Zhou PZ, Gao L, Wang LW, Zhang YF, Song WL

and Hao YX: Clinical observation of magnesium aluminum carbonate

combined with rabeprazole-based triple therapy in the treatment of

helicobacter pylori-positive gastric ulcer associated with

hemorrhage. Pak J Med Sci. 38:1271–1277. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Yuan K, Du X, Dong L, Pan J and Xue W:

Modelling the tumor microenvironment in vitro in prostate cancer:

Current and future perspectives. VIEW:. 5(20240074)2024.

|