Introduction

Refractory ascites represents a particularly severe

manifestation of decompensated liver cirrhosis, often indicating a

terminal disease phase marked by a diminished quality of life,

frequent hospital admissions and a median transplant-free survival

of only 6-12 months (1,2). Despite therapeutic advancements such

as diuretic regimens, large-volume paracentesis, albumin

supplementation and the use of transjugular intrahepatic

portosystemic shunt (TIPS), achieving sustained symptomatic relief

remains clinically challenging (3,4).

Notably, accumulating evidence suggests that metabolic

dysregulation persists even after TIPS, continuing to exert adverse

effects on patient outcomes (5,6). In

light of the limited therapeutic efficacy and marked disease burden

associated with refractory ascites, there is a growing need to

elucidate its underlying pathophysiological mechanisms.

Mounting research underscores the critical interplay

between the gut and liver in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis

(7). The intestinal microbiome,

comprising a complex, adaptable microbial ecosystem, has emerged as

a key regulator of hepatic homeostasis via its metabolic

byproducts, immunomodulatory actions and contribution to intestinal

barrier integrity (8,9). In cirrhosis, microbial dysbiosis,

characterized by reduced species richness, overrepresentation of

opportunistic taxa and compromised mucosal defense, is increasingly

recognized as a driving factor in hepatic inflammation, bacterial

translocation and secondary complications such as hepatic

encephalopathy and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (10,11).

More recently, shifts in ascitic bacterial composition have been

shown to correlate with disease severity and clinical prognosis,

suggesting that refractory ascites may be associated with a

distinct microbial signature (1,12,13).

However, integrative studies specifically addressing microbiota and

metabolic alterations in this subgroup remain sparse.

Advances in high-throughput methodologies now allow

for comprehensive profiling of the gut ecosystem and its metabolic

outputs (14). The application of

16S rRNA sequencing in tandem with gas chromatography-mass

spectrometry (GC-MS)-based untargeted metabolomics provides a

multidimensional view of host-microbe interactions. A previous

investigation into ascitic fluid metabolomics have highlighted

notable disruptions in biochemical pathways, particularly those

involved in amino acid and lipid metabolism, underscoring the

metabolic complexity associated with advanced cirrhosis (15). The integration of microbial and

metabolic profiling offers a promising approach to elucidate the

pathophysiological mechanisms underlying refractory ascites.

In the present study, an integrated analysis of the

intestinal microbiota and fecal metabolome of patients with

cirrhosis-related refractory ascites was performed. Through

simultaneous 16S rRNA sequencing and GC-MS-based metabolomics, the

present study aimed to characterize disease-specific microbial

communities and metabolic alterations. This approach may provide

novel insights into the gut-liver axis disturbances contributing to

disease progression and inform the development of biomarker-driven

diagnostic or therapeutic strategies.

Materials and methods

Study design and participants

Between July 2023 and July 2024, a total of 140

participants were enrolled from the Department of Hepatology at

Qiannan People's Hospital (Duyun, China), comprising 70 individuals

clinically diagnosed with decompensated cirrhosis accompanied by

refractory ascites (OB group) and 70 healthy control subjects (NC

group) with comparable age and sex distribution. The age and sex

distributions were as follows: in the OB group, there were 47 men

and 23 women with a mean age of 59.36±10.81 years, while in the NC

group, there were 24 men and 46 women with a mean age of 57.42±9.65

years. The eligible age range for inclusion was 40 to 75 years.

Diagnosis of refractory ascites was established in accordance with

the diagnostic criteria specified in the 2017 guidelines published

by the Chinese Society of Hepatology (16). Cirrhosis in participants was

diagnosed through a combination of clinical evaluations and imaging

techniques, including ultrasound, CT scans and MRI. Liver biopsy

was performed when necessary for confirmation, based on clinical

judgment.

The NC group had no prior history of liver disease,

gastrointestinal disorders or other conditions that could

potentially influence the gut microbiota. Additionally, this group

was not affected by chronic conditions such as hypertension,

diabetes, cardiovascular issues or any ongoing inflammatory

diseases. The cause of cirrhosis in participants from the OB group

was established through a combination of clinical evaluation and

laboratory assessments, with common underlying causes being viral

hepatitis (such as hepatitis B or C virus) alcohol-related liver

disease, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Participants in

each group were excluded if they had a history of cancer, recent

abdominal surgery (particularly procedures related to the liver),

uncontrolled infections or severe organ failure. Additional

exclusion criteria included cachexia, recent gastrointestinal

infections (within the previous month), pregnancy, lactation or the

use of antibiotics, corticosteroids or probiotics within 2 weeks

before enrollment.

The sample size was determined based on previous

studies (17,18) with similar patient cohorts and a

power analysis was conducted to ensure sufficient statistical power

(80%) with a significance level of P<0.05 (19,20).

Participants were allocated to either the OB or NC group based on

predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The OB group included

patients with confirmed cirrhosis and refractory ascites, diagnosed

through clinical evaluation, imaging studies and ascitic fluid

analysis. The NC group consisted of individuals without liver

disease or other chronic gastrointestinal or systemic conditions

and with routine laboratory test results within the normal limits.

No randomization was performed for the group assignment, as this

was a cohort study, but matching for age and sex between the two

groups was performed. Renal function was evaluated in all OB group

participants by measuring serum creatinine and calculating the

glomerular filtration rate (GFR) to rule out the possibility of

hepatorenal syndrome (HRS). In addition, all participants in the OB

group were evaluated for the presence of hepatic encephalopathy

using clinical assessment based on the West Haven criteria

(21).

Upon recruitment, comprehensive dietary and

lifestyle information from the previous 1 to 3 months was obtained

from each subject. Dietary information was collected using a food

frequency questionnaire, which asked participants about their daily

food intake frequency over the past month. Lifestyle factors such

as physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption and sleep habits

were assessed using self-reported surveys. These surveys covered

the lifestyle of the participants in the 1 to 3 months prior to the

study to account for any potential confounding factors. In the OB

group, all participants underwent endoscopic evaluation to detect

esophageal varices and signs of gastric bleeding, common

complications in cirrhosis. Ethical approval was granted by the

institutional review board of The People's Hospital of Qiannan

(grant no. 2022-qnzy-18), and written informed consent was obtained

from all participants prior to sample collection and data

acquisition.

During the study period, no patients in the OB group

experienced death directly attributable to the condition.

Additionally, none of the OB group patients underwent TIPS or liver

transplantation during the course of the study. All OB group

patients underwent diagnostic paracentesis to determine the cause

of ascites, with ascitic fluid analysis performed to assess cell

count, protein concentration and albumin gradient, which was

performed in accordance with the diagnostic criteria for refractory

ascites as outlined in the practice guidelines by the American

Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (22).

Assessment of clinical parameters

Liver function tests, including alanine

aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), total

bilirubin and albumin, were measured following standard clinical

protocols. Prothrombin time (PT) and the international normalized

ratio (INR) were assessed using coagulometric methods. To evaluate

renal function, serum creatinine levels were determined, while urea

nitrogen was measured with routine biochemical techniques. Sodium

and potassium concentrations were quantified using an automated

electrolyte analyzer. The GFR was estimated using the

Cockcroft-Gault formula based on serum creatinine levels (23).

Fecal sample collection and

storage

Fresh fecal samples were collected from each

participant, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then

stored at -80˚C until further processing. Each sample was divided

into aliquots for microbiome and metabolomic analysis, ensuring

consistency and reducing freeze-thaw cycles.

Microbial DNA extraction and 16S rRNA

sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from 200 mg of fecal

material using the QIAamp Fast DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen GmbH;

cat. no. 51604), following the manufacturer's protocol. DNA

integrity and concentration were evaluated using 1% agarose gel

electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer. The V3-V4

hypervariable regions of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene were amplified

using the primers 341F (5'-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3') and 806R

(5'-GGACTACHVGGGTATCTAAT-3'), with an expected product length of

~466 bp. Amplified PCR products were purified with QIAquick PCR

Purification Kit (Qiagen GmbH; cat. no. 28104) and quantified using

a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer. Sequencing libraries were constructed

using the TruSeq DNA PCR-Free Kit (Illumina, Inc; cat. no.

20015962). The final library concentration was quantified by qPCR

and loaded at a final concentration of 12.5 nM for sequencing on

the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. Raw reads were processed by

quality filtering and paired-end merging using FLASH (v1.2.11;

https://ccb.jhu.edu/software/FLASH/),

followed by clustering into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at

97% similarity using USEARCH (v1.0.667; https://www.drive5.com/usearch/). Taxonomic annotation

was conducted using the Greengenes database (v13_8; https://greengenes.secondgenome.com) with a

minimum confidence threshold of 0.6. α and β diversity indices

(such as Chao1, Shannon and Simpson) were calculated using

Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME; v1.9.1;

http://qiime.org/) and MOTHUR (v1.45.3; https://mothur.org/). Principal coordinate analysis

(PCoA), Bray-Curtis dissimilarity and Analysis of Similarities

(ANOSIM) were performed in R (v4.3.1; https://www.r-project.org/). Functional predictions of

microbial communities were generated using PICRUSt2 (v2.5.0;

https://github.com/picrust/picrust2),

Tax4Fun2 (v1.1.5; https://github.com/bwemheu/Tax4Fun2) and BugBase

(v1.0.0; https://github.com/knights-lab/BugBase) to assess

pathway involvement and phenotypic traits.

Metabolite extraction and GC-MS

profiling

Fecal samples were allowed to thaw at ambient

temperature before ~20 mg of each sample was transferred into a

sterile 2 ml microcentrifuge tube containing 400 µl of 70% methanol

with pre-added internal standards (succinic acid-D4,

cat. no. 571687; L-valine-D8, cat. no. 486927;

Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). The mixture was vortexed for 3 min to

ensure adequate dispersion and then subjected to ultrasonic

extraction at a frequency of 40 kHz in an ice-water bath for 10

min. After sonication, the suspension was incubated at -20˚C for 30

min to precipitate proteins and other particulates. The sample was

centrifuged at 13,000 x g for 10 min at 4˚C, and 300 µl of the

resulting supernatant was transferred to a new tube. A second

centrifugation at 13,000 x g for 3 min was performed, after which

200 µl of the clarified supernatant was collected for downstream

analysis. Untargeted metabolomic analysis was carried out using a

GC-MS system (TripleTOF 6600+; SCIEX) equipped with a Waters T3

reverse-phase column (2.1x100 mm, 1.8 µm particle size).

Chromatographic separation was achieved using a binary solvent

system composed of 0.1% formic acid in water (mobile phase A) and

0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (mobile phase B). The gradient

program was as follows: 0 min, 95% A; 2 min, 80% A; 5 min, 40% A; 6

min, 1% A; 7.5 min, 1% A; 7.6 min, 95% A; and 10 min, 95% A. The

flow rate was set at 0.4 ml/min and the injection volume was 4 µl.

The column was maintained at a constant temperature of 40˚C. Mass

spectrometric data were acquired in both positive and negative

electrospray ionization (ESI) modes under an information-dependent

acquisition method using Analyst TF 1.7.1 software (SCIEX).

Ionization parameters were as follows: Ion source voltage of +5,000

V (ESI+) and -4,000 V (ESI-), source temperatures of 550˚C and

450˚C for positive and negative modes, respectively, nebulizer gas

at 50 psi, auxiliary heating gas at 60 psi, curtain gas at 35 psi

and a declustering potential of ±60 V. Collision energies were set

at ±10 V for MS1 and ±30 V for MS2, with a collision energy spread

of 15 V. Each mode was acquired over a total runtime of 10 min. The

present study employed an untargeted metabolomics approach and data

were acquired in full-scan mode. Metabolite identification was

based on matching retention times and mass spectra with those in

the NIST and Fiehn libraries (see below).

Metabolomic data processing

Raw data obtained from GC-MS analysis were initially

processed using ChromaTOF software (v.4.72; LECO Corporation) for

peak detection, deconvolution and retention time alignment.

Baseline correction and noise filtering were applied to enhance

signal clarity and ensure consistent feature extraction. Metabolic

features with >50% missing values across all samples were

excluded from further analysis. The remaining missing values were

estimated using a k-nearest neighbor algorithm to maintain data

completeness without compromising structure. To account for

instrument drift and technical variability, total ion current

normalization was applied across all chromatograms. Compound

identification was performed by matching deconvoluted spectra

against commercial reference libraries, such as NIST (https://www.nist.gov/srd/nist-standard-reference-database-1a)

and FiehnLib (https://fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/projects/fiehnlib), using

a similarity threshold of ≥80%. Metabolite identities were further

verified through manual inspection of fragmentation patterns and

retention indices. Only compounds consistently detected in the

quality control samples with a coefficient of variation <30%

were retained for downstream statistical analysis. All

post-processing, normalization and compound filtering, as well as

the subsequent multivariate and univariate analyses, were performed

in MetaboAnalyst 5.0 (https://www.metaboanalyst.ca). Data transformation and

scaling were applied within the platform prior to these statistical

analyses. The diagnostic efficiency of differential metabolites was

evaluated by constructing receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curves in R (v.4.3.0) with the pROC package, and the area under the

curve (AUC) was calculated to quantify their discriminative

ability.

Functional enrichment analysis

Metabolites retained after annotation and filtering

were mapped to reference pathways based on the Kyoto Encyclopedia

of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) compound database. Functional

enrichment analysis was conducted using the KEGG Pathway platform

(https://www.genome.jp/kegg/), aiming to

identify significantly perturbed metabolic routes across

experimental conditions. Enrichment significance was evaluated

based on the hypergeometric test, with a false discovery rate

cut-off of <0.05 used to define significantly enriched pathways.

Pathway coverage and biological relevance were also considered in

the final interpretation. In addition, associations between key

metabolites and human diseases were explored using the Human

Metabolome Database (HMDB; https://hmdb.ca/).

Statistical analysis

Statistical procedures were used to compare

microbial and metabolomic characteristics between groups and to

assess their relationships with clinical variables. For microbiome

data, differences in α-diversity were evaluated using either

parametric or non-parametric tests, selected according to the

distribution of the data with unpaired Student's t-test applied to

normally distributed data and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test used for

non-normally distributed data. For examining individual metabolite

differences in the metabolomic data, appropriate univariate tests

were used depending on data distribution, including unpaired

Student's t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Only metabolites

that met the predefined criteria for statistical significance were

included in subsequent interpretation. Associations between

refractory ascites and clinical indicators were examined using

Pearson correlation analysis. GraphPad Prism (version 9.5.1;

Dotmatics) was used for these statistical analyses. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Patients in the OB group have reduced

microbial richness and diversity

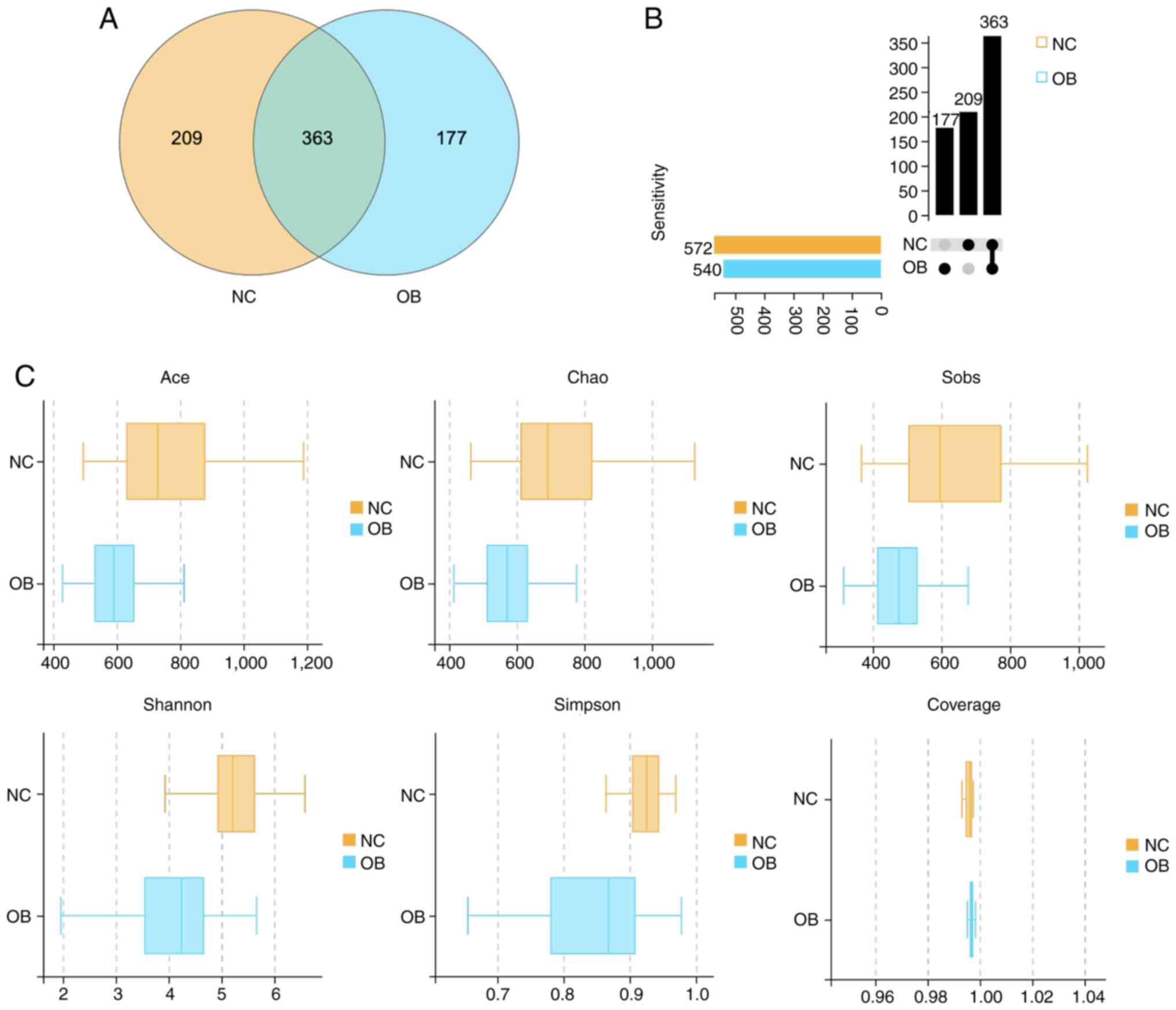

A total of 749 OTUs were obtained following rigorous

quality filtration and sequence clustering of 16S rRNA gene reads.

Among them, 572 OTUs were identified in the NC group and 540 in the

OB group, with 363 OTUs shared across both cohorts. The Venn

diagram illustrates the distribution of overlapping and

group-specific OTUs (Fig. 1A). To

further characterize the pattern of taxa presence and

co-occurrence, an UpSet plot was constructed. The plot provided a

more granular view of intersection sets and subgroup relationships

(Fig. 1B). This visualization

offered an intuitive overview of OTU overlap and structural

complexity between the groups. To assess within-sample microbial

diversity, α diversity indices were calculated and compared between

the groups. As shown in Fig. 1C,

richness estimators, including Ace, Chao1 and Sobs, were

significantly lower in the OB group than in the NC group

(P<0.05), indicating a marked reduction in microbial richness.

Similarly, Shannon and Simpson indices were decreased in the OB

group, reflecting diminished community evenness and overall

diversity compared with the NC group. Notably, the Coverage index

approached 1 in both groups, confirming sufficient sequencing depth

and reliable representation of microbial communities.

Additionally, clinical parameters of the NC and OB

groups were analyzed. The results indicated that in the OB group,

liver function markers (ALT, AST and total bilirubin) were higher,

albumin was lower, coagulation markers (prothrombin time and INR)

were prolonged, creatinine levels were elevated and electrolyte

concentrations (sodium and potassium) were lower. No significant

change was observed in urea nitrogen levels (Table I). These findings reflected a

decline in microbial richness and diversity in individuals with

refractory ascites, highlighting notable ecological disturbance

associated with cirrhosis.

| Table IClinical parameters comparisons

between the OB and NC groups. |

Table I

Clinical parameters comparisons

between the OB and NC groups.

| Clinical

parameter | NC group

(n=70) | OB group

(n=70) | P-value |

|---|

| Sex,

male/female | 24/46 | 31/39 | 0.84 |

| Liver function

tests | | | |

|

ALT,

U/l | 24.71±1.15 | 52.27±6.54 | 0.0002 |

|

AST,

U/l | 23.04±1.04 | 134.57±23.16 | <0.001 |

|

Total

bilirubin, µmol/l | 17.07±2.36 | 61.41±9.51 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 48.18±0.46 | 29.64±1.09 | <0.001 |

| Coagulation

function | | | |

|

Prothrombin

time, sec | 12.64±0.11 | 17.39±0.31 | <0.001 |

|

International

normalized ratio | 1.18±0.01 | 1.45±0.03 | <0.001 |

| Renal function | | | |

|

Creatinine,

µmol/l | 66.47±1.33 | 133.62±21.67 | <0.001 |

|

Urea

nitrogen, mmol/l | 5.88±0.18 | 7.87±0.66 | 0.1378 |

| Electrolytes | | | |

|

Sodium,

mmol/l | 140.76±0.37 | 137.51±0.58 | <0.001 |

|

Potassium,

mmol/l | 4.36±0.06 | 4.00±0.08 | <0.001 |

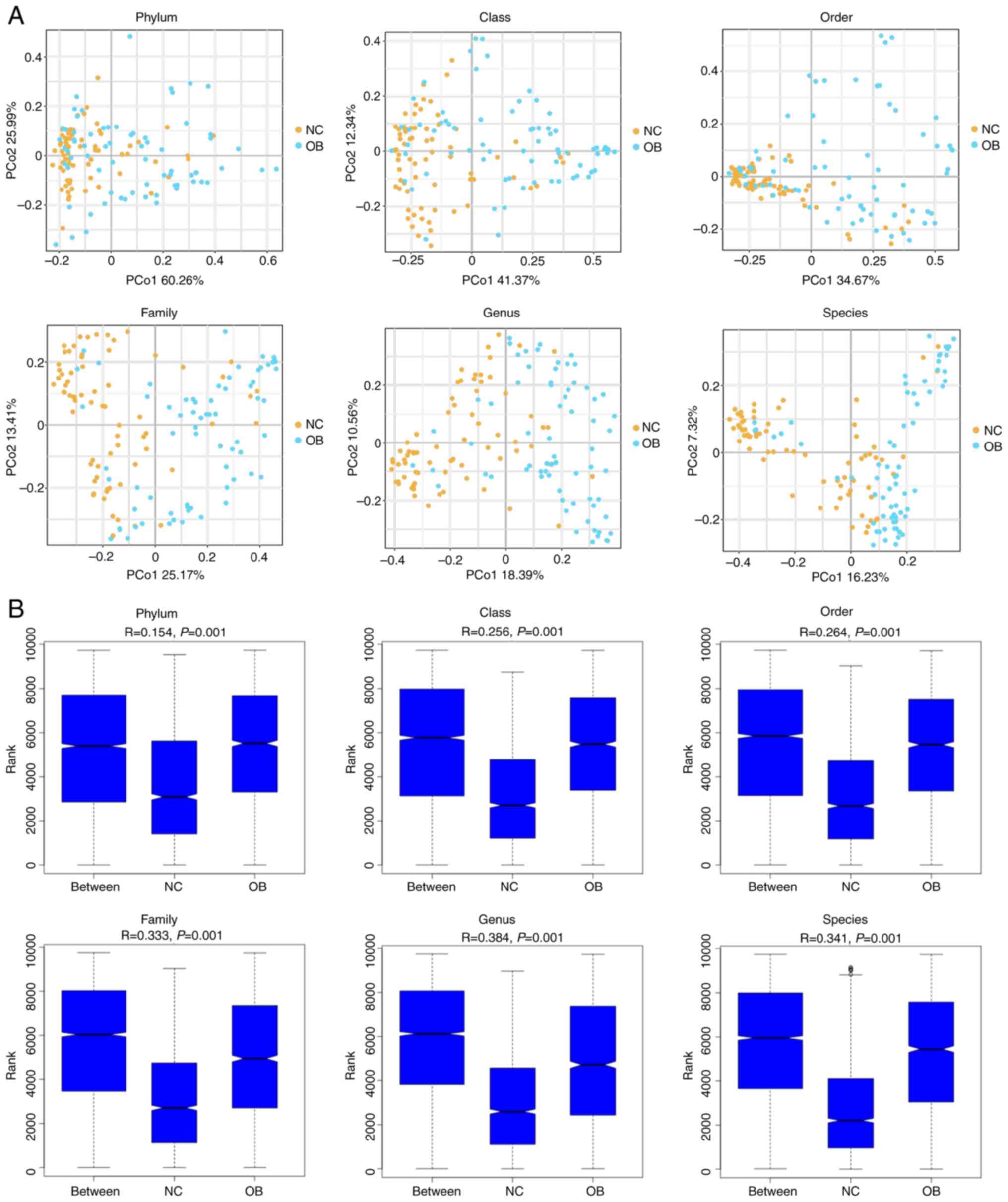

β diversity analysis reveals distinct

microbial community structures between the OB and NC groups

To evaluate the structural variation of the gut

microbiota between cirrhotic patients and healthy individuals, β

diversity analysis was performed across multiple taxonomic levels.

PCoA plots based on Bray-Curtis distances revealed a clear spatial

separation between the NC and OB groups at all six taxonomic ranks,

from phylum to species (Fig. 2A),

indicating distinct community compositions between the groups. The

degree of separation appeared more pronounced at lower taxonomic

levels, particularly at the genus and species ranks. The ANOSIM

results further supported these observations, demonstrating

significant dissimilarities between groups at each taxonomic rank

(Fig. 2B; r>0.25, P<0.001).

Together, these findings illustrate that the gut microbial

communities of cirrhotic patients differed markedly from those of

healthy controls, suggesting ecological shifts linked to disease

progression.

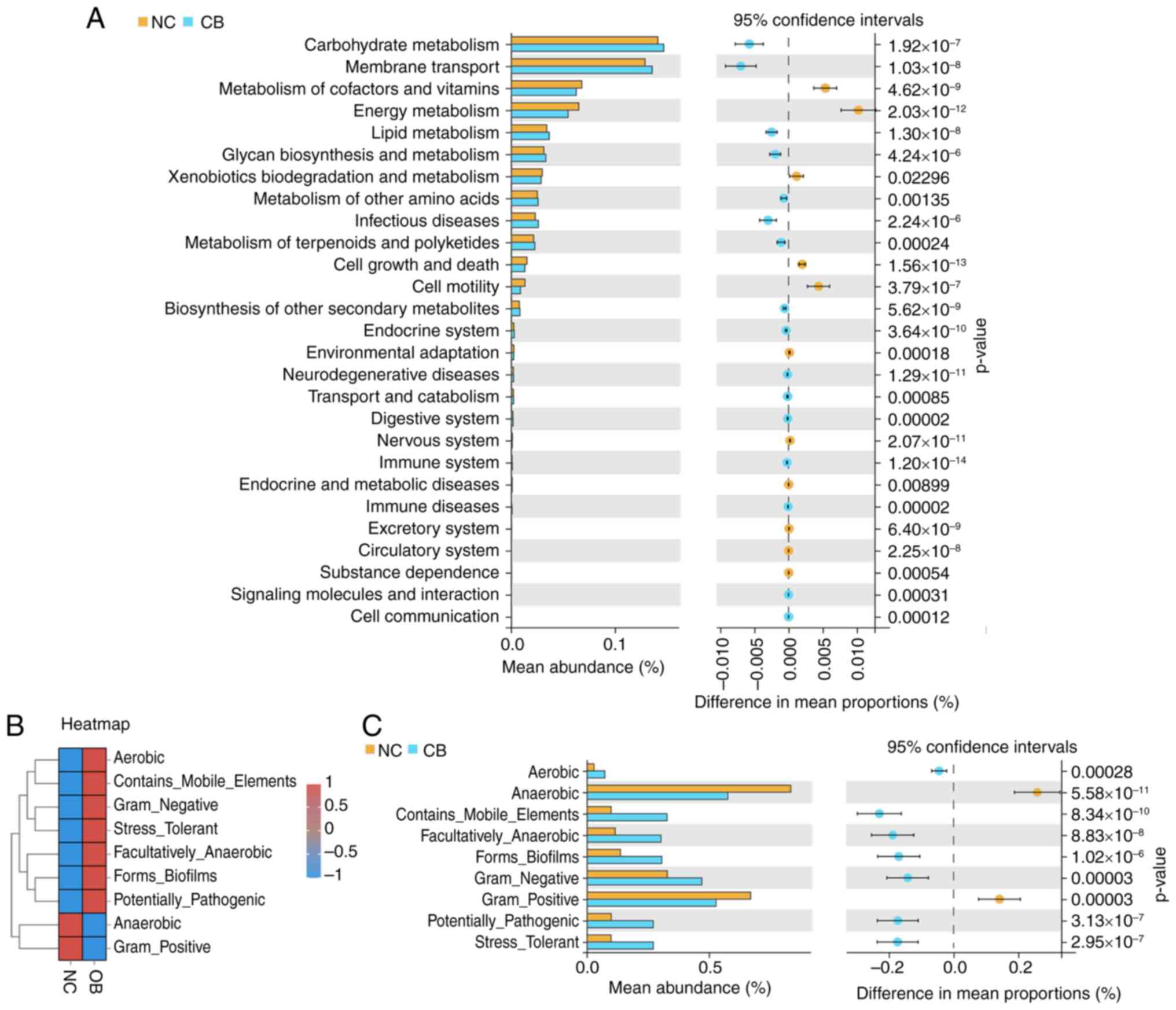

Functional and phenotypic alterations

of gut microbiota in the OB group

Next, the potential functional differences in the

gut microbiota between groups was explored. Microbial gene

functions were inferred using PICRUSt2. As displayed in Fig. 3A, the pathways related to

‘Carbohydrate Metabolism,’ ‘Membrane Transport’ and the ‘Metabolism

of Cofactors and Vitamins’ were among the most notable predicted

functions, with observable differences noted between the NC and OB

samples. Several immune- and disease-related pathways, such as

those associated with infectious diseases, neurodegenerative

disorders and endocrine system regulation, also displayed

significant variation. Additionally, microbial phenotypic

characteristics were analyzed using BugBase (Fig. 3B and C). The heatmap revealed contrasting trends

in phenotypes such as aerobicity, pathogenic potential and biofilm

formation between the two cohorts. Quantitative comparisons showed

that compared with the NC group, the OB group exhibited higher

proportions of ‘Aerobic’, ‘Contains_Mobile_Elements’,

‘Facultatively_Anaerobic’, ‘Forms_Biofilms’, ‘Gram_Negative’,

‘Potentially_Pathogenic’ and ‘Stress_Tolerant’ phenotypes. By

contrast, the ‘Anaerobic’ and ‘Gram_Positive’ phenotypes were

significantly lower in the OB group (Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that

microbial functional capacities and phenotype expression profiles

were altered in the OB group, as reflected by distinctions in the

predicted pathways and microbial traits.

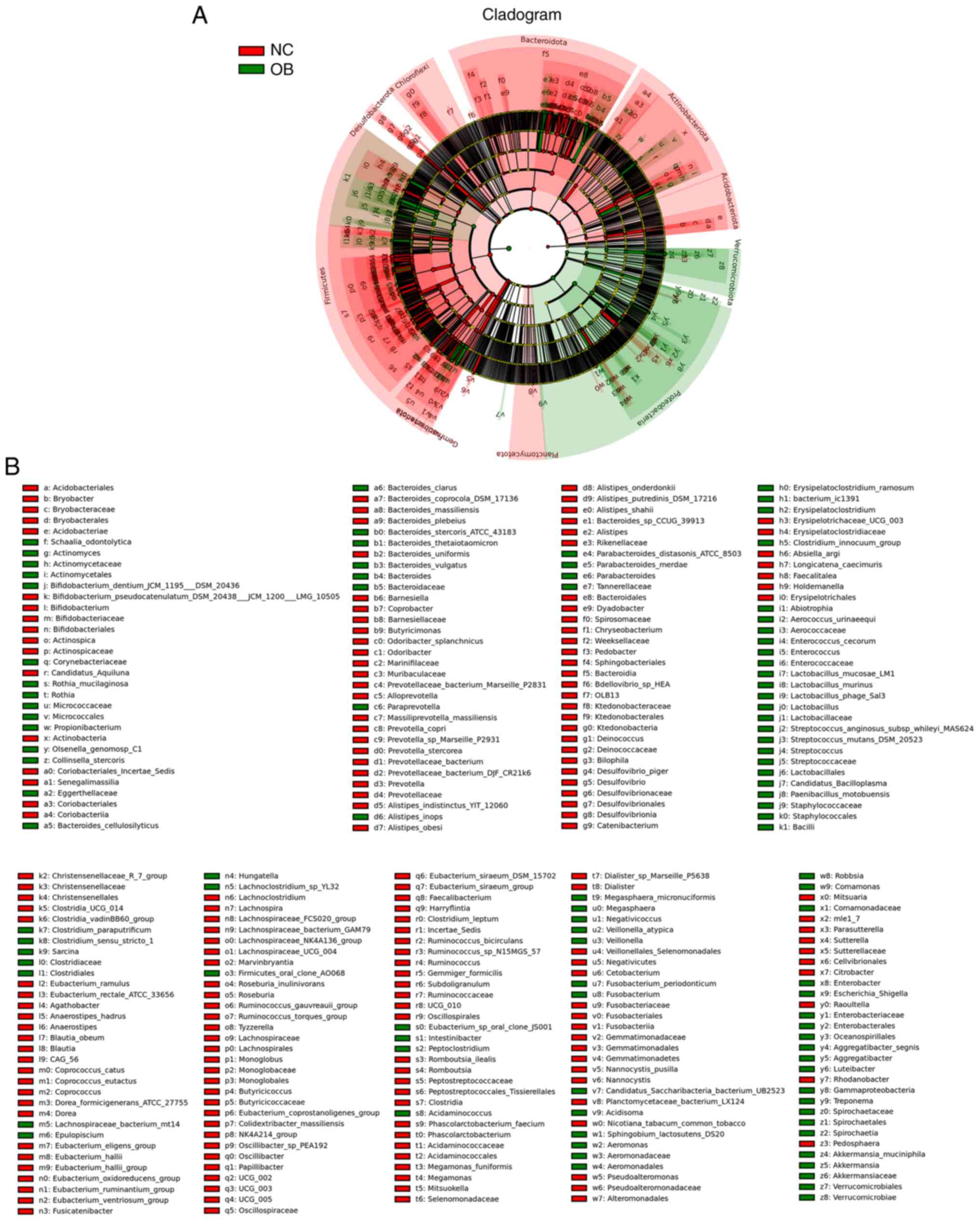

Microbial taxa with differential

distribution identified by LEfSe

To investigate the taxonomic differences in gut

microbiota composition between the OB and NC groups, LEfSe analysis

was performed to identify taxa exhibiting differential abundance

across taxonomic ranks. The cladogram in Fig. 4A illustrates the phylogenetic

structure of these taxa, with color-coded branches representing

features associated with either the NC or OB group. Several taxa

were found to vary in relative abundance between groups (Fig. 4B). For instance, members of the

phyla Bacteroidota and Actinobacteriota appeared more associated

with the NC group, while taxa belonging to Firmicutes, including

genera such as Clostridium and Lactobacillus, were

relatively more abundant in the OB group. These variations were

evident across multiple levels of taxonomy, suggesting distinct

microbial profiles characterizing the two cohorts.

Metabolomic distinctions between the

OB and NC groups based on GC-MS analysis

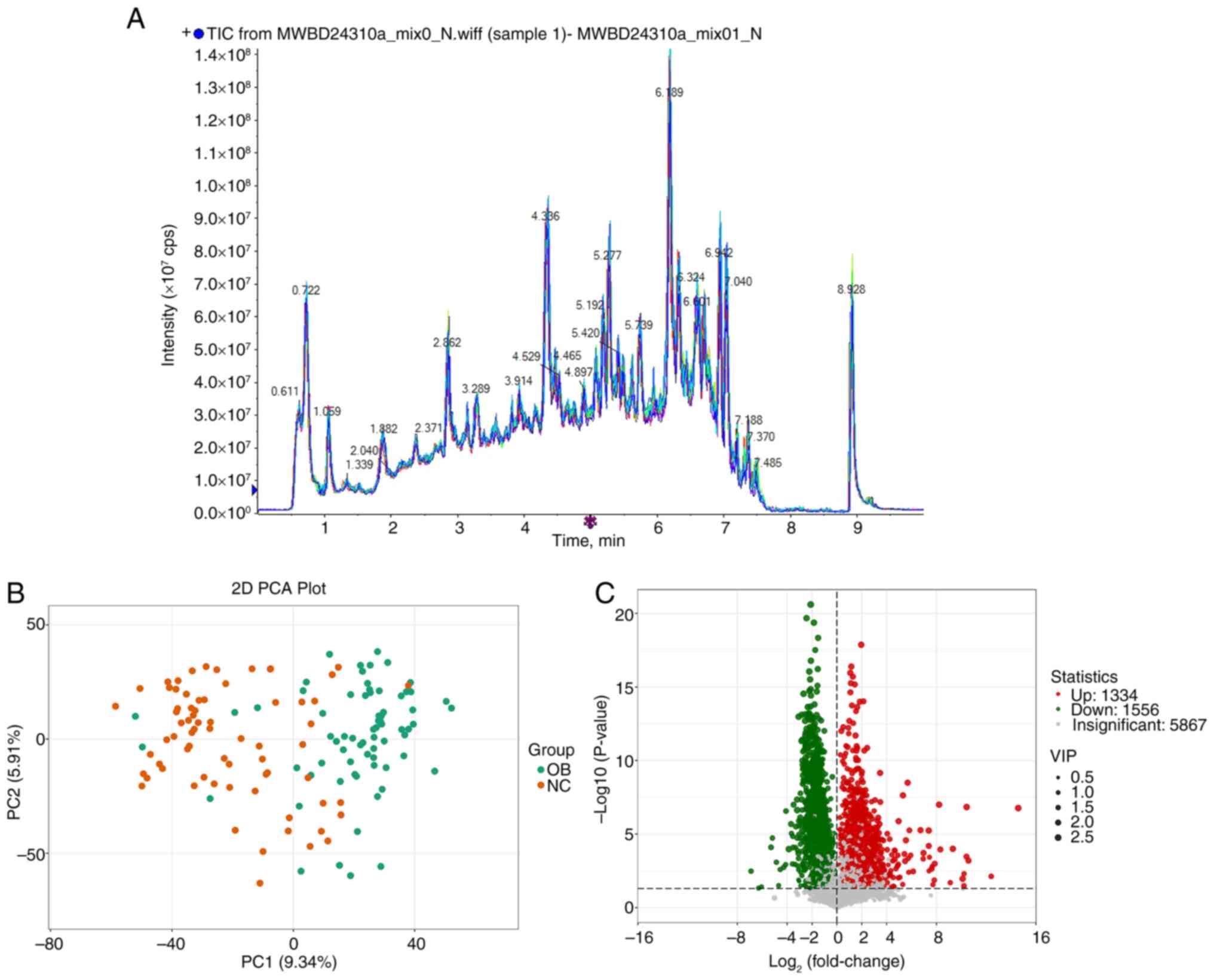

Building on the observed taxonomic differences in

gut microbiota, untargeted metabolomic profiling was performed to

investigate compositional variations at the metabolite level. Fecal

samples from both the OB and NC groups were analyzed using GC-MS

and the representative total ion chromatograms showed comparable

spectral patterns across samples (Fig.

5A). PCA based on the full metabolite dataset revealed a

distributional shift between the OB and NC groups (Fig. 5B), with samples from each cohort

forming distinguishable clusters. This suggests divergence in

global metabolic features between the two groups. Differential

metabolite screening further identified a wide array of altered

features. A total of 8,777 metabolites were detected, among which

1,334 exhibited increased abundance and 1,556 were decreased in the

OB group compared with the NC group (Fig. 5C). To highlight the most relevant

metabolic shifts, the top 20 upregulated and downregulated

metabolites based on fold change and P-value are summarized in

Tables II and III, respectively. These tables provide

detailed chemical information, statistical significance and fold

changes of the most altered compounds, thereby offering a clearer

view of the molecular disturbances associated with the OB group.

These results offer an initial view of metabolic alterations

between the OB and NC groups.

| Table IITop 20 upregulated differential

metabolites between the OB and NC groups. |

Table II

Top 20 upregulated differential

metabolites between the OB and NC groups.

| No. | Compound | Formula | P-value | Log2FC |

|---|

| 1 |

4-Chloro-5-sulfamoylanthranilic acid |

C7H7ClN2O4S | <0.0001 | 14.58 |

| 2 | Lithospermic acid

B |

C36H30O16 | 0.0075 | 12.41 |

| 3 |

Dihydrorobinetin |

C15H12O7 | 0.0006 | 10.58 |

| 4 |

2,8-Dichloro-3-dibenzofuranol |

C12H6Cl2O2 | <0.0001 | 10.43 |

| 5 | Diflunisal |

C13H8F2O3 | 0.0003 | 10.42 |

| 6 | S1P Lyase

Fluorogenic Substrate |

C15H10O8S | 0.0330 | 10.21 |

| 7 |

[3-(6,7-dihydroxy-4-oxo-4H-chromen-2-yl)

phenyl] oxidanesulfonic acid |

C14H10ClN3O4S | 0.0109 | 10.11 |

| 8 |

N-[(3-chloro-2-hydroxy-5-nitrophenyl)

carbamothioyl] benzamide |

C6H11O6PS | 0.0001 | 9.32 |

| 9 |

5-(Methylthio)-2,3-dioxopentyl

phosphate |

C19H12O8 | 0.0001 | 8.32 |

| 10 |

(1R*,3R*,3'S*)-1,2,3,4-Tetrahydro-1-(2-thio-3-pyrrolidinyl)-beta-carboline-3-carboxylic

acid |

C8H7ClN4S | <0.0001 | 8.21 |

| 11 | Diacerein |

C15H11ClN2O2 | 0.0010 | 7.86 |

| 12 |

6-(2-Chloroallylthio)purine |

C40H40O11 | 0.0135 | 7.83 |

| 13 | Oxazepam |

C14H12O6S | 0.0271 | 7.72 |

| 14 |

1-[3-(6-{2,4-dihydroxy-3-[(1E)-3-methylbut-1-en-1-yl]

benzoyl}-5-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-4-hydroxy-3-methylcyclohex-2-en-1-yl)-2,4-dihydroxyphenyl]-3-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)

propan-1-one |

C13H19N3O10 | 0.0016 | 7.66 |

| 15 |

Resveratrol-3-O-sulfate |

C23H34O5 | 0.0023 | 7.62 |

| 16 | Glu-Asp-Asp |

C18H14O8 | 0.0004 | 7.44 |

| 17 | Latanoprost

acid |

C36H28O16 | 0.0032 | 7.4 |

| 18 | (2S-3S)-versiconal

hemiacetal |

C12H11ClN2O5S | 0.0001 | 7.39 |

| 19 | Theaflavin

monogallates |

C16H30N4O5 | <0.0001 | 7.39 |

| 20 | Furosemide |

C23H31FO6 | 0.0002 | 6.96 |

| Table IIITop 20 downregulated differential

metabolites between the OB and NC groups. |

Table III

Top 20 downregulated differential

metabolites between the OB and NC groups.

| No. | Compound | Formula | P-value | Log2FC |

|---|

| 1 | Cortisone

acetate |

C23H30O6 | 0.0033 | -6.90 |

| 2 | Colubrinic

acid |

C30H46O4 | 0.0470 | -6.30 |

| 3 |

2-[1-Hydroxy-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)propyl]-3,5-dimethoxyphenol |

C18H22O5 | 0.0379 | -6.06 |

| 4 | Goshonoside F2 |

C26H44O8 | 0.0001 | -5.30 |

| 5 | Fasciculic acid

C |

C38H63NO11 | <0.0001 | -5.18 |

| 6 | Imperialine |

C27H43NO3 | 0.0008 | -4.86 |

| 7 | Lys-Lys-Ser |

C15H31N5O5 | 0.0315 | -4.68 |

| 8 | Glu-Gln-Gln |

C15H25N5O8 | 0.0026 | -4.56 |

| 9 | Sarpagine |

C19H22N2O2 | 0.0018 | -4.28 |

| 10 |

(Z)-7-[(2R)-3-hydroxy-2-[(E,4R)-4-hydroxy-4-(1-propylcyclobutyl)

but-1-enyl]-5-oxocyclopentyl]hept-5-enoic acid |

C23H36O5 | 0.0012 | -4.12 |

| 11 | Isoeugenitol |

C11H10O4 | <0.0001 | -4.09 |

| 12 | Prostaglandin E2

methyl ester |

C21H34O5 | 0.0001 | -3.86 |

| 13 |

(1R,8S,9S)-3,4-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-11,11-dimethyl-5-propan-2-yl-16-oxatetracyclo[7.5.2.01,10.02,7]hexadeca-2,4,6-trien-15-one |

C21H28O5 | <0.0001 | -3.69 |

| 14 | E-Norendoxifen |

C24H25NO2 | <0.0001 | -3.65 |

| 15 | Oleyl acetate |

C20H38O2 | 0.0011 | -3.56 |

| 16 | Val-Asp-Asp |

C13H21N3O8 | <0.0001 | -3.54 |

| 17 | 14,15-Epoxyemindole

SB |

C28H39NO2 | 0.0001 | -3.52 |

| 18 |

Phe-Ile-His-Arg |

C27H41N9O5 | <0.0001 | -3.48 |

| 19 | Tiocarlide |

C23H32N2O2S | 0.0012 | -3.34 |

| 20 | Fingolimod |

C19H33NO2 | 0.0001 | -3.32 |

Exploration of enriched pathways

linked to altered metabolites

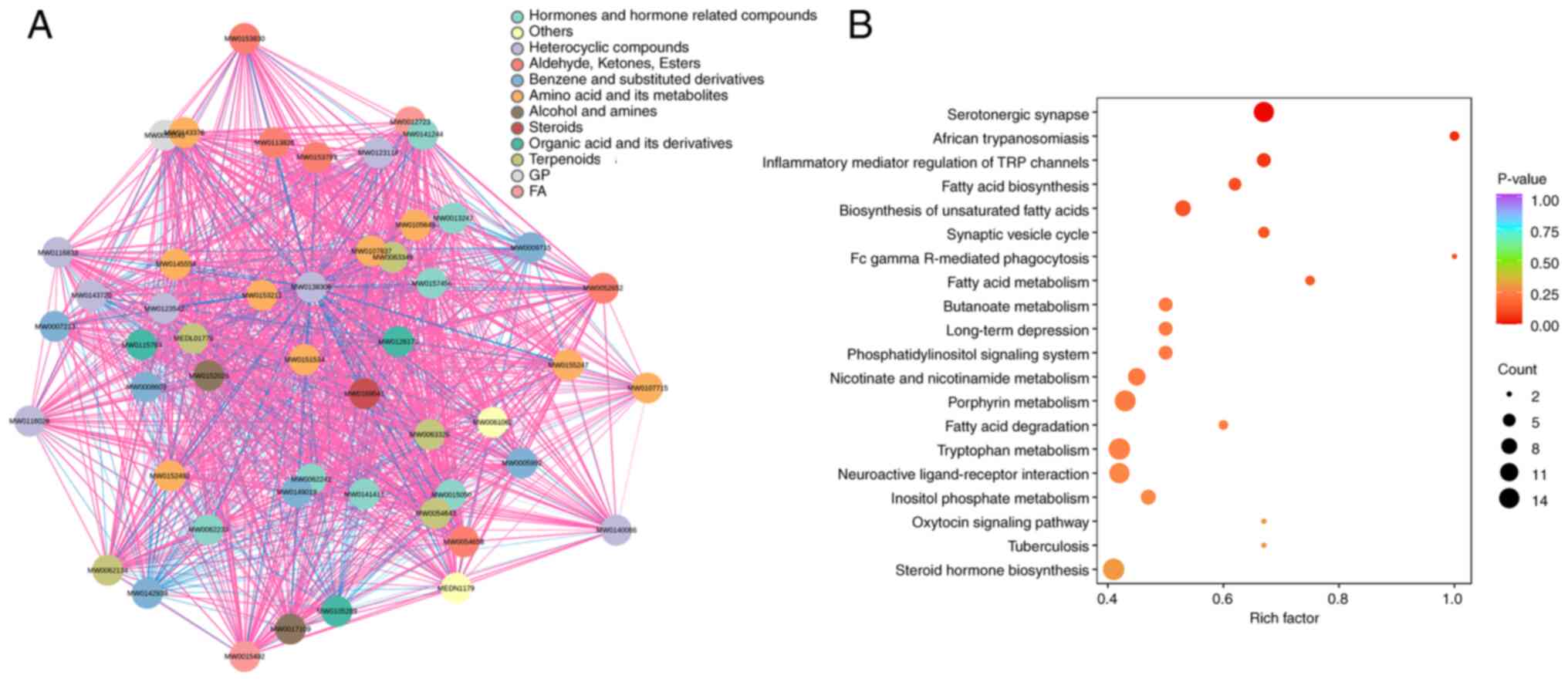

Based on the screened differential metabolites, a

compound network was constructed to illustrate chemical

associations and structural classifications. Metabolites were

categorized into groups such as amino acid derivatives, steroids,

fatty acids and heterocyclic compounds, with dense interconnections

observed both within and between chemical classes (Fig. 6A). Then, KEGG pathway enrichment was

conducted using the annotated metabolites. A range of pathways were

implicated, including those involved in neurotransmitter signaling

(such as ‘Serotonergic synapse’), lipid metabolism (such as ‘Fatty

acid biosynthesis’ and ‘Fatty acid degradation’) and hormonal

regulation (such as ‘Steroid hormone biosynthesis’ and ‘Oxytocin

signaling pathway’) (Fig. 6B).

Evaluation of diagnostic performance

of differential metabolites

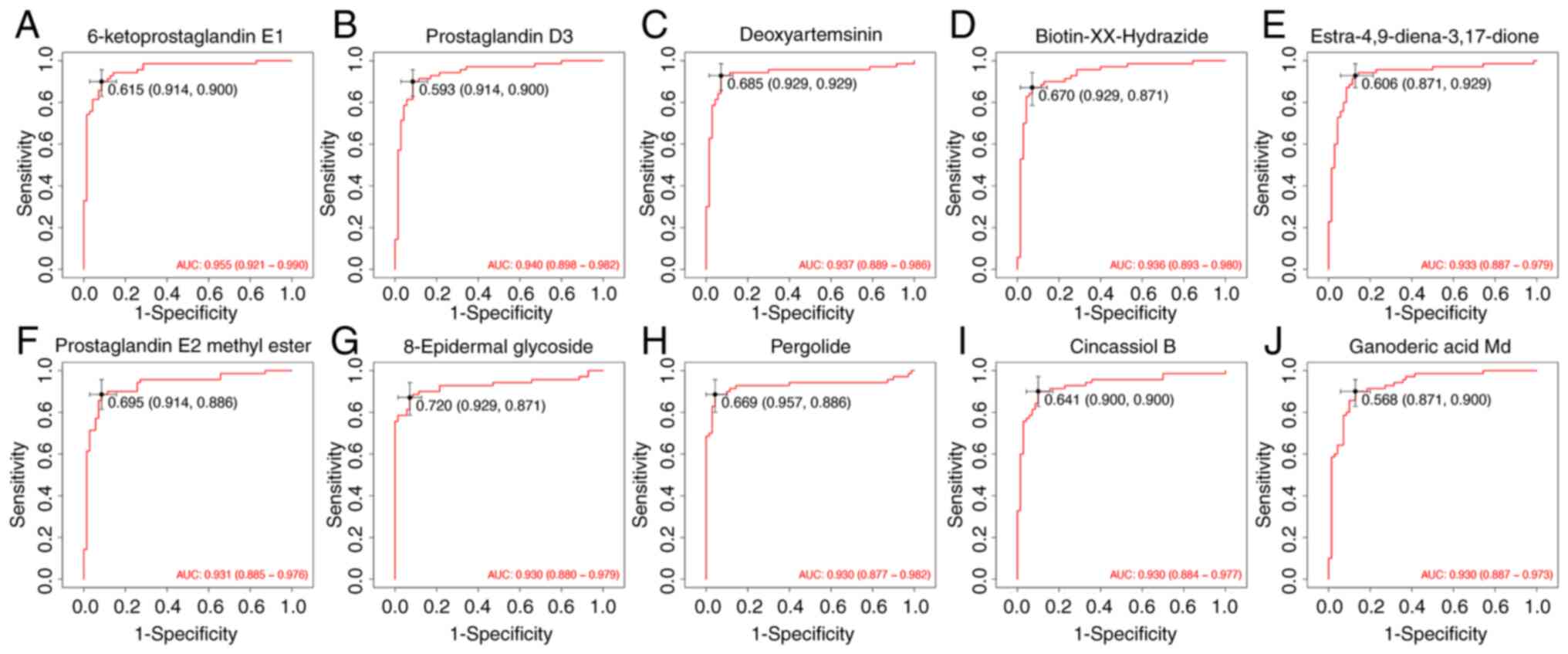

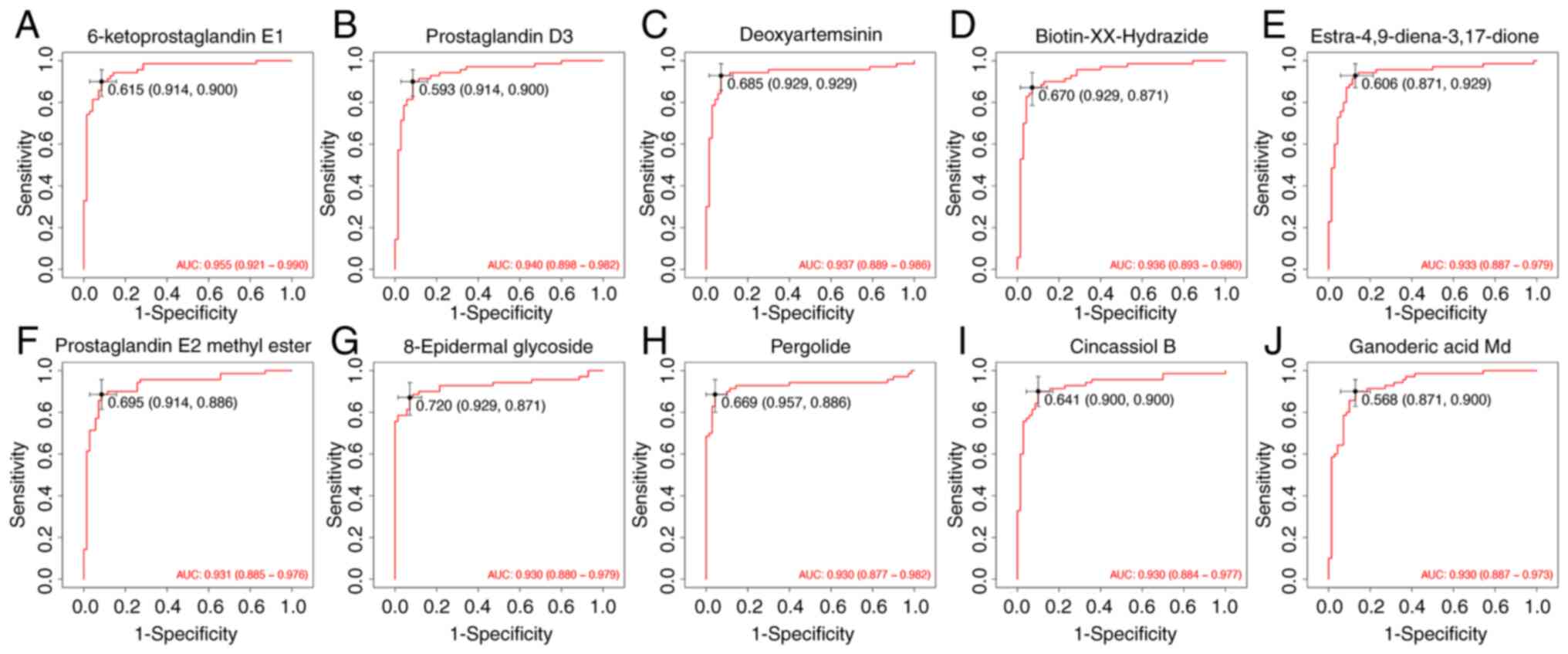

The present study further assessed the

classification potential of key metabolites with receiver operator

characteristic curve analysis. A total of 10 representative

metabolites were selected based on their relevance in prior

screening and annotation. All selected metabolites yielded area

under the curve (AUC) values ≥0.93, with the highest observed for

6-ketoprostaglandin E1 (AUC=0.955). Other compounds such as

prostaglandin D3 (AUC=0.940), deoxyartemisinin (AUC=0.937) and

ganoderic acid Md (AUC=0.930) also exhibited strong classification

performance. The full list included: biotin-XX-hydrazide

(AUC=0.936), estra-4,9-diene-3,17-dione (AUC=0.933), prostaglandin

E2 methyl ester (AUC=0.931), 8-epidermal glycoside (AUC=0.930),

pergolide (AUC=0.930) and cincassiol B (AUC=0.930) (Fig. 7). These results suggest that the

identified features may have contributed to group differentiation

in the metabolomics cohort and provide reference for subsequent

validation efforts.

| Figure 7ROC curve analysis of 10 candidate

metabolites distinguishing the NC and OB groups. ROC curves between

the NC and OB groups were generated for the following metabolites:

(A) 6-ketoprostaglandin E1, (B) prostaglandin D3, (C)

deoxyartemisinin, (D) biotin-XX-hydrazide, (E)

estra-4,9-diene-3,17-dione, (F) prostaglandin E2 methyl ester, (G)

8-epidermal glycoside, (H) pergolide, (I) cincassiol B, and (J)

ganoderic acid Md. Values in black on the ROC curves indicate the

optimal cut-off value, followed by the corresponding sensitivity

and specificity in parentheses. ROC, receiver operating

characteristic; NC, normal control; OB, refractory ascites group;

AUC, area under the curve. |

Disease association of key

differential metabolites

Beyond evaluating the diagnostic value of the

differential metabolites, their potential links to human diseases

were further investigated by referencing the KEGG and HMDB

databases. Among them, L-tryptophan, hypoxanthine, and indole

exhibited broad associations with various pathological conditions,

notably encompassing neurological disorders (such as epilepsy,

schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease), chronic inflammatory

diseases (including Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis and

rheumatoid arthritis), as well as multiple malignancies (such as

colorectal, ovarian and pancreatic cancer). For example,

L-tryptophan alone was associated with >20 disease states,

reflecting its multifaceted role in systemic metabolic regulation.

Likewise, hypoxanthine was associated with several metabolic

syndromes and tumor-related processes. Besides, other metabolites,

including serotonin, phenylethylamine and deoxycholic acid, were

implicated in both gastrointestinal and neuropsychiatric conditions

(Table IV). Collectively, these

associations underscored the potential involvement of these

metabolites in disease-related metabolic pathways and support their

biological relevance within the study context.

| Table IVDisease associations of differential

metabolites: Refractory ascites groups vs. healthy group. |

Table IV

Disease associations of differential

metabolites: Refractory ascites groups vs. healthy group.

| Compound Name | The Human

Metabolome Database diseases |

|---|

| L-Tryptophan | Epilepsy |

Schizophrenia | Alzheimer's disease | Colorectal cancer | Ovarian

cancer | Obesity | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide deficiency |

Hartnup disease | Leukemia | Olivopontocerebral atrophy |

Hereditary spastic paraplegia | Hypothyroidism | Friedreich's

ataxia | Celiac disease | Irritable bowel syndrome | Ulcerative

colitis | Autism | Crohn's disease | Rheumatoid arthritis |

Perillyl alcohol administration for cancer treatment | Pancreatic

cancer | Periodontal disease | Frontotemporal dementia | Lewy body

disease | Attachment loss | Periodontal probing depth | Cachexia |

Eosinophilic esophagitis | Tryptophanuria with dwarfism |

| Hypoxanthine | Lesch-Nyhan

syndrome | Canavan disease | Thymidine treatment | Uremia |

Xanthinuria type 1 | Degenerative disc disease | Hydrocephalus |

3-methyl-crotonyl-glycinuria | Irritable bowel syndrome |

Colorectal cancer | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis |

Rheumatoid arthritis | Perillyl alcohol administration for cancer

treatment | Pancreatic cancer | Periodontal disease | Alzheimer's

disease | Frontotemporal dementia | Lewy body disease | Attachment

loss | Periodontal probing depth | Lung cancer | Autosomal dominant

polycystic kidney disease | Eosinophilic esophagitis |

Hepatocellular carcinoma | Molybdenum cofactor deficiency | Sulfite

oxidase deficiency, ISOLATED | Phosphoribosylpyrophosphate

synthetase superactivity |

| Tryptamine | Irritable bowel

syndrome | Colorectal cancer |

| Phenethylamine | Bulimia nervosa |

Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | Minimal brain dysfunction |

Autism |

| Nicotinic acid | Alcoholism |

Colorectal cancer | Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis |

Attachment loss | Missing teeth | Periodontal probing depth |

|

7-Methylguanine | Colorectal

cancer |

| Deoxycholic

acid | Cystic fibrosis |

Irritable bowel syndrome | Ulcerative colitis | Colorectal cancer |

Primary biliary cirrhosis |

| Oxindole | Colorectal

cancer |

Correlation between refractory ascites

and clinical parameters

To further explore the clinical relevance of

refractory ascites, Pearson correlation analysis was performed

between refractory ascites status and routine clinical parameters.

The results demonstrated that refractory ascites was positively

correlated with PT (r=0.536, P<0.001), INR (r=0.533,

P<0.001), TBIL (r=0.384, P=0.001) and urea nitrogen (r=0.285,

P=0.019), while showing negative correlations with serum albumin

(r=-0.299, P=0.012) and sodium (r=-0.270, P=0.024). No significant

associations were observed with age, sex, ALT, AST, potassium or

creatinine (all P>0.05). These findings suggest that impaired

coagulation, hyperbilirubinemia, hypoalbuminemia and electrolyte or

renal disturbances are closely linked with the presence of

refractory ascites (Table V).

| Table VPearson correlation analysis between

refractory ascites and clinical parameters. |

Table V

Pearson correlation analysis between

refractory ascites and clinical parameters.

| Parameter | Correlation

coefficient (r) | P-value |

|---|

| PT | 0.536 | <0.001 |

| INR | 0.533 | <0.001 |

| TBIL | 0.384 | 0.001 |

| Albumin (g/l) | -0.299 | 0.012 |

| Urea nitrogen | 0.285 | 0.019 |

| Sodium

(mmol/l) | -0.27 | 0.024 |

| Diagnosis | 0.229 | 0.056 |

| Potassium

(mmol/l) | 0.218 | 0.070 |

| Creatinine | 0.105 | 0.393 |

| ALT | 0.028 | 0.817 |

| Age | -0.024 | 0.841 |

| Sex | -0.012 | 0.919 |

| AST | -0.012 | 0.920 |

Discussion

The present study offers an in-depth and integrative

assessment of microbial dysbiosis and metabolic abnormalities in

individuals with refractory ascites secondary to cirrhosis,

uncovering notable disturbances across the gut-liver axis. The data

revealed a marked decline in intestinal microbial richness and

significant compositional divergence between the refractory ascites

cohort and healthy counterparts. These alterations included a

notable proliferation of Proteobacteria, particularly

Enterobacteriaceae, alongside a depletion of beneficial anaerobes

such as Bacteroidota and Actinobacteriota. Such microbial

transitions favoring pathogenic species with enhanced oxidative

resilience and biofilm-forming capacities may aggravate bacterial

translocation and systemic inflammatory responses, both central to

the disease pathophysiology.

In the present study, 16S rRNA sequencing was

employed to characterize the microbial community structure, a

high-throughput and widely validated approach that targets the

variable regions of bacterial ribosomal RNA genes to resolve

taxonomic profiles (24). This

technique has been extensively utilized across diverse clinical

contexts, including gastrointestinal, hepatic and respiratory

diseases (25-28).

For instance, it has been applied to identify nasopharyngeal

microbiota alterations in SARS-CoV-2 infection (29). Although widely used in cirrhosis

research, its specific application in the context of refractory

ascites remains underrepresented. This technique enables the

detection of nuanced but clinically meaningful shifts that would

likely be missed through conventional culture methods (30,31).

In addition to overall compositional shifts, distinct dominance

patterns in the OB group were identified in the present study, with

taxa such as Escherichia-Shigella, Enterobacteriaceae and

Gammaproteobacteria markedly enriched compared with controls. These

microbial signatures may reflect selective pressures favoring

opportunistic pathogens under cirrhotic gut conditions. The use of

16S rRNA gene sequencing, a more specific approach than traditional

cultures, enabled the resolution of taxonomic profiles with greater

precision in the present study. However, we acknowledge that while

this method offers significant advantages in microbial

identification, challenges remain in terms of both the cost and the

systematic application of metabolite studies in clinical settings.

Future research may need to explore ways to reduce the cost of

metabolite studies and promote their standardization, ensuring

broader applicability in clinical practice.

Findings from BugBase phenotype predictions

substantiated the observations of the present study, indicating

elevated levels of Gram-negative bacteria, facultative anaerobes

and organisms capable of biofilm production in the ascitic group.

These insights are consistent with recent work by Shi et al

(32), who utilized metagenomic

next-generation sequencing (mNGS) to reveal a high prevalence of

polymicrobial infections in cirrhotic ascitic fluid, including a

dominance of Enterobacteriaceae and other fastidious facultative

pathogens not detected via traditional culture techniques. Their

conclusions emphasized the pathogenic potential of microbial

imbalances and invasive phenotypes in precipitating spontaneous

bacterial peritonitis and systemic immune activation (32), thereby reinforcing the clinical

significance of the microbiota-based findings of the present study.

Notably, these pathogenic phenotypes also suggest that

hypoxia-induced niche disruption and accumulation of oxidative

stress-tolerant species may be key contributors to intestinal

permeability, further linking microbial dysfunction with systemic

disease progression.

In the present study, further functional inference

revealed disruptions in microbial pathways governing carbohydrate

metabolism, vitamin biosynthesis and membrane-associated transport

systems. These imbalances may hinder the production of beneficial

microbial metabolites, such as short-chain fatty acids, and

compromise host mucosal defense. Similar host-microbiota

interactions have been reported in colitis models, where

Marinifilaceae enrichment was linked to suppressed cell cycle

signaling in Toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice (33). Comparable disruptions have been

described by Gitto et al (34), who observed persistent functional

impairments in gut microbiota among patients post-TIPS procedure,

including reduced synthesis of anti-inflammatory lipids such as

octanoic acid and enrichment of inflammation-promoting taxa. While

their study focused on post-intervention systemic effects, the

results of the present study highlight the possibility that such

microbial dysregulation originates earlier at the intestinal level.

The integration of functional annotation tools with community

structure analysis in the present study provides enhanced

mechanistic insight.

In parallel, comprehensive untargeted metabolite

profiling using GC-MS, a technique renowned for its sensitivity in

detecting low-molecular-weight volatile and semi-volatile

compounds, was performed in the present study. GC-MS has garnered

increasing attention in hepatology due to its ability to delineate

metabolic signatures indicative of liver pathology and ascitic

fluid composition (15,35). In the present study, fecal

metabolomics allowed the identification of gut-derived biochemical

alterations, a number of which were associated with the observed

microbiome shifts. Notably, compared with ascitic fluid-based

metabolomics, fecal analysis may offer earlier and more direct

insights into intestinal metabolic dysfunctions that precede

systemic involvement, such as peritonitis or encephalopathy

(36).

In the present study, an integrative metabolomic

analysis combining GC-MS and LC-MS platforms uncovered ~2,900

differentially expressed fecal metabolites. KEGG pathway enrichment

analysis revealed significant disturbances in serotonergic synapse

activity, steroid biosynthesis and neuroactive ligand-receptor

signaling networks. These findings mirror those of Beyoğlu et

al (15), who reported

increased amino acid levels and reduced fatty acid content in

ascitic fluid from cirrhotic patients, pointing to malabsorption

and lipid processing failure. Metabolites such as L-tryptophan and

hypoxanthine, consistently elevated in both the present study and

the study by Beyoğlu et al are recognized modulators of

immune and neurological function (37,38).

Additionally, the present study identified gut-origin compounds,

such as indole and deoxycholic acid, which may serve as

intermediaries in gut-liver communication pathways and merit

further mechanistic exploration.

Sustained oxidative stress is widely acknowledged as

a defining feature of advanced-stage liver cirrhosis, where it

contributes to the disruption of epithelial integrity, propagation

of systemic inflammation and dysregulation of immune responses

(39,40). Within this pathological framework,

multiple metabolites uncovered in the present study, including

hypoxanthine, deoxycholic acid and several indole-related

molecules, appear to engage in redox-sensitive processes and

ROS-driven signaling cascades (41-43).

These metabolites not only mirror the prevailing oxidative

imbalance but may also functionally reinforce inflammatory pathways

and enhance intestinal permeability. Their consistent elevation in

fecal profiles of patients with refractory ascites reinforces their

biological relevance and suggests utility as molecular tracers of

gut-liver axis dysfunction. Among the metabolite features showing

significant differential expression in the present study, 10

exhibited outstanding discriminatory accuracy (AUC≥0.93),

indicating promising diagnostic applicability. These molecular

indicators could complement existing clinical practices for the

early identification and stratification of refractory ascites

cases. Building upon prior findings by Beyoğlu et al

(15), the present study

contributes additional gut-associated candidates with putative

roles in modulating redox homeostasis, host metabolism and immune

signaling dynamics.

Unlike prior investigations that often analyzed

microbial or metabolomic dimensions in isolation, the present study

employed a dual-omics strategy to uncover co-occurring disruptions

across both domains. This allowed for direct alignment of taxonomic

and functional microbial traits with associated metabolic readouts,

thereby delivering a more integrative view of gut-liver axis

dysfunction. Such methodological synergy enhances the ability to

identify both mechanistic drivers and therapeutic targets, paving

the way for precision interventions, such as probiotic

formulations, dietary modulation or microbiota transplantation, to

restore microbial equilibrium and improve outcomes.

Despite the contributions of the present study,

certain limitations should be acknowledged. The cross-sectional

design inherently limits causal inference. Although the cohort size

exceeds that of several related studies, broader multi-center

validation is necessary. Additionally, experimental validation via

targeted functional assays or host-microbiome interaction models is

essential to confirm mechanistic interpretations. Future efforts

should also explore targeted modulation of specific microbial

communities, including the role of pathogenic Enterobacteriaceae,

in attenuating disease progression. Intervention-based trials with

dietary fiber, microbiota-derived postbiotics or strain-level

probiotics may offer feasible therapeutic routes. Future directions

should also include longitudinal follow-up, interventional trials

targeting microbiota or metabolism and integration with host

transcriptomic and immunological profiling. Furthermore, adoption

of mNGS and whole-genome metagenomics may refine taxonomic

resolution and uncover rare but clinically relevant taxa. Another

limitation of the present study is the absence of a direct

comparison between cirrhotic patients with ascites and those with

refractory ascites. Such a comparison could provide specific

microbial and metabolic alterations that distinguish refractory

ascites from standard ascites, particularly in terms of fecal

metabolome and microbial function. Future research should include

this comparative approach, which would enhance the understanding of

the mechanisms behind refractory ascites and their resistance to

conventional therapies. Furthermore, the biomarkers and therapeutic

targets identified in the present study require further validation,

and multicenter studies and randomized controlled trials are

essential to confirm their clinical efficacy and applicability.

Moreover, the role of dysbiosis and the increase in opportunistic

pathogens in the progression of refractory ascites, spontaneous

peritonitis and HRS remains insufficiently explored. Future studies

should focus on elucidating the complex interactions within the

gut-liver axis, which may uncover novel diagnostic and therapeutic

targets.

In conclusion, through a combined analysis of gut

microbiota and fecal metabolomics, the present study demonstrated

that individuals with cirrhosis-related refractory ascites harbor

marked disturbances in both microbial ecology and metabolic

regulation. The microbial landscape was notably skewed toward

Gram-negative, potentially pathogenic species, accompanied by a

marked loss of protective anaerobic taxa. These compositional

changes were accompanied by functional alterations in metabolic

pathways implicated in oxidative stress balance, immune system

dynamics and neurotransmitter signaling. Among the identified fecal

metabolites, several showed strong discriminatory capacity,

highlighting their value as potential biomarkers for early

detection and clinical stratification. Together, these insights

emphasize the pivotal role of gut-liver axis disruption in disease

progression and support the development of targeted microbiota or

metabolite-based interventions. Furthermore, the present study

provides a foundation for future research aimed at developing

diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions, which could

significantly impact clinical practice. The findings provide a

solid scientific basis for advancing translational strategies aimed

at restoring gut homeostasis and improving patient outcomes in

end-stage liver disease.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: This work was supported by the 8th Talent Base of

Guizhou Province-Qiannan Prefecture Talent Base for Infectious

Disease Prevention and Control (grant no. RCJD2020-67), the

Guangzhou Science and Technology Program (grant no. 202103000060)

and the Science and Technology Fund of Guizhou Provincial Health

Commission (grant no. g2wkj2023-292).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be found

in the Genome Sequence Archive and the OMIX database of the

National Genomics Data Center under accession nos. CRA029925 and

OMIX011954 or at the following URLs: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa/browse/CRA029925 and

https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/release/OMIX011954,

respectively.

Authors' contributions

DC was responsible for conceptualization,

methodology and data interpretation, and was a major contributor in

writing the original draft. SL performed the formal analysis, data

curation and visualization and contributed to funding acquisition

and manuscript reviewing and editing. KZ conducted the

investigation and was responsible for resource provision and

experimental validation. KP contributed to data analysis,

experimental validation and manuscript review and editing. LZ

supervised the project, contributed to study design and data

interpretation, and administered the overall study. DS carried out

methodology development, investigation and data curation. JZ

contributed to data visualization and formal analysis. DR was

involved in study conceptualization, critical interpretation of

data and supervised the study. DC and SL confirm the authenticity

of all the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final

version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Ethical approval was granted by the institutional

review board of Qiannan People's Hospital (approval no.

2022-qnzy-18). Written informed consent was obtained from all human

participants.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Wong F: Management of refractory ascites.

Clin Mol Hepatol. 29:16–32. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zhao R, Lu J, Shi Y, Zhao H, Xu K and

Sheng J: Current management of refractory ascites in patients with

cirrhosis. J Int Med Res. 46:1138–1145. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zaccherini G, Tufoni M, Iannone G and

Caraceni P: Management of ascites in patients with cirrhosis: An

update. J Clin Med. 10(5226)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Rajesh S, George T, Philips CA, Ahamed R,

Kumbar S, Mohan N, Mohanan M and Augustine P: Transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhosis: An exhaustive

critical update. World J Gastroenterol. 26:5561–5596.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Debernardi Venon W, Lo Pumo S, Imperatrice

B, Giorgi M, Righi D, Fonio P, Saracco GM and Marzano A:

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in refractory

ascites: Clinical impact of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction.

Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 33 (1S Suppl 1):e464–e470.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Gu L, Yin X, Cheng Y, Wang X, Zhang M, Zou

X, Wang L, Zhuge Y and Zhang F: Overweight/Obesity increases the

risk of overt hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular

intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in cirrhotic patients. J Pers Med.

13(682)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Tranah TH, Edwards LA, Schnabl B and

Shawcross DL: Targeting the gut-liver-immune axis to treat

cirrhosis. Gut. 70:982–994. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Usuda H, Okamoto T and Wada K: Leaky gut:

Effect of dietary fiber and fats on microbiome and intestinal

barrier. Int J Mol Sci. 22(7613)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Ma L, Ni Y, Wang Z, Tu W, Ni L, Zhuge F,

Zheng A, Hu L, Zhao Y, Zheng L and Fu Z: Spermidine improves gut

barrier integrity and gut microbiota function in diet-induced obese

mice. Gut Microbes. 12:1–19. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Guan H, Zhang X, Kuang M and Yu J: The

gut-liver axis in immune remodeling of hepatic cirrhosis. Front

Immunol. 13(946628)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Nishimura N, Kaji K, Kitagawa K, Sawada Y,

Furukawa M, Ozutsumi T, Fujinaga Y, Tsuji Y, Takaya H, Kawaratani

H, et al: Intestinal permeability is a mechanical rheostat in the

pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis. Int J Mol Sci.

22(6921)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Larrue H, Vinel JP and Bureau C:

Management of severe and refractory ascites. Clin Liver Dis.

25:431–440. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Helil AS, Haile SA, Birhanu Y, Desalegn H,

Desalegn DM, Geremew RA, Gebreyohannes Z, Mohammed A,

Wondimagegnehu DD, Ayana G, et al: Bacterial profile, drug

resistance pattern, clinical and laboratory predictors of ascites

infection in cirrhosis patients. BMC Infect Dis.

24(528)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Han S, Guiberson ER, Li Y and Sonnenburg

JL: High-throughput identification of gut microbiome-dependent

metabolites. Nat Protoc. 19:2180–2205. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Beyoğlu D, Simillion C, Storni F, De

Gottardi A and Idle JR: A metabolomic analysis of cirrhotic

ascites. Molecules. 27(3935)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Guidelines on the management of ascites

and complications in cirrhosis. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi.

25:664–677. 2017.(In Chinese).

|

|

17

|

Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, Wang B, Chen Y, Lei

D, Wang Y, Zhu B and Li L: Characterization of fecal microbial

communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology.

54:562–572. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Althubaiti A: Sample size determination: A

practical guide for health researchers. J Gen Fam Med. 24:72–78.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Malik M, Hnatkova K, Batchvarov V, Gang Y,

Smetana P and Camm AJ: Sample size, power calculations, and their

implications for the cost of thorough studies of drug induced QT

interval prolongation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 27:1659–1669.

2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Biau DJ, kernéis S and Porcher R:

Statistics in brief: The importance of sample size in the planning

and interpretation of medical research. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

466:2282–2288. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Weissenborn K: Hepatic encephalopathy:

Definition, clinical grading and diagnostic principles. Drugs. 79

(Suppl 1):S5–S9. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Biggins SW, Angeli P, Garcia-Tsao G, Ginès

P, Ling SC, Nadim MK, Wong F and Kim WR: Diagnosis, evaluation, and

management of ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and

hepatorenal syndrome: 2021 practice guidance by the American

Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology.

74:1014–1048. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Delanaye P, Björk J, Courbebaisse M, Couzi

L, Ebert N, Eriksen BO, Dalton RN, Dubourg L, Gaillard F, Garrouste

C, et al: Performance of Creatinine-based equations to estimate

glomerular filtration rate with a methodology adapted to the

context of drug dosage adjustment. Br J Clin Pharmacol.

88:2118–2117. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Heidrich V, Inoue LT, Asprino PF, Bettoni

F, Mariotti ACH, Bastos DA, Jardim DLF, Arap MA and Camargo AA:

Choice of 16S ribosomal RNA primers impacts male urinary microbiota

profiling. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 12(862338)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Bharti R and Grimm DG: Current challenges

and best-practice protocols for microbiome analysis. Brief

Bioinform. 22:178–193. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Kryukov K, Imanishi T and Nakagawa S:

Nanopore sequencing data analysis of 16S rRNA genes using the

GenomeSync-GSTK system. Methods Mol Biol. 2632:215–226.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Zhang T, Li H, Ma S, Cao J, Liao H, Huang

Q and Chen W: The newest Oxford Nanopore R10.4.1 full-length 16S

rRNA sequencing enables the accurate resolution of species-level

microbial community profiling. Appl Environ Microbiol.

89(e0060523)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Zhang W, Fan X, Shi H, Li J, Zhang M, Zhao

J and Su X: Comprehensive assessment of 16S rRNA gene amplicon

sequencing for microbiome profiling across multiple habitats.

Microbiol Spectr. 11(e0056323)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Bozza S, Nunzi E, Frias-Mazuecos A,

Pieraccini G, Pariano M, Renga G, Mencacci A, Talesa VN, Antognelli

C, Puccetti P, et al: SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with Age-

and Gender-specific changes in the nasopharyngeal microbiome. Front

Biosci (Landmark Ed). 29(59)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong BY,

Petersen LM, Demkowicz P, Chen L, Leopold SR, Hanson BM, Agresta

HO, Gerstein M, et al: Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for

species and Strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun.

10(5029)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Sanschagrin S and Yergeau E:

Next-generation sequencing of 16S ribosomal RNA gene amplicons. J

Vis Exp: 51709, 2014 doi: 10.3791/51709.

|

|

32

|

Shi P, Liu J, Liang A, Zhu W, Fu J and Wu

X, Peng Y, Yuan S and Wu X: Application of metagenomic

next-generation sequencing in optimizing the diagnosis of ascitic

infection in patients with liver cirrhosis. BMC Infect Dis.

24(503)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Shi YJ, Sheng KW, Zhao HN, Liu C and Wang

H: Toll-like receptor 2 deficiency exacerbates dextran sodium

sulfate-induced intestinal injury through Marinifilaceae-dependent

attenuation of cell cycle signaling. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed).

29(338)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Gitto S, Vizzutti F, Baldi S, Campani C,

Navari N, Falcini M, Venturi G, Montanari S, Roccarina D, Arena U,

et al: Transjugular intrahepatic Porto-systemic shunt positively

influences the composition and metabolic functions of the gut

microbiota in cirrhotic patients. Dig Liver Dis. 55:622–628.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Beyoğlu D, Popov YV and Idle JR: The

metabolomic footprint of liver fibrosis. Cells.

13(1333)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Singh R, Zogg H, Wei L, Bartlett A,

Ghoshal UC, Rajender S and Ro S: Gut microbial dysbiosis in the

pathogenesis of gastrointestinal dysmotility and metabolic

disorders. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 27:19–34. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Seo SK and Kwon B: Immune regulation

through tryptophan metabolism. Exp Mol Med. 55:1371–1379.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Ye J, Bi X, Deng S, Wang X, Liu Z, Suo Q,

Wu J, Chen H, Wang Y, Qian K, et al: Hypoxanthine is a metabolic

biomarker for inducing GSDME-dependent pyroptosis of endothelial

cells during ischemic stroke. Theranostics. 14:6071–687.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Roehlen N, Crouchet E and Baumert TF:

Liver fibrosis: Mechanistic concepts and therapeutic perspectives.

Cells. 9(875)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Sak JJ, Prystupa A, Bis-Wencel H, Kiciński

P, Luchowska-Kocot D, Krukowski H, Nowicki GJ and Panasiuk L:

Oxidative stress-induced growth inhibitor 1 in alcohol-induced

liver cirrhosis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 28:676–680. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Blachier F: Metabolism of dietary

substrates by intestinal bacteria and consequences for the host

intestine. In: Metabolism of alimentary compounds by the intestinal

microbiota and health. Springer, pp45-144, 2023.

|

|

42

|

Alonso-Peña M, Espinosa-Escudero R,

Herraez E, Briz O, Cagigal ML, Gonzalez-Santiago JM, Ortega-Alonso

A, Fernandez-Rodriguez C, Bujanda L, Calvo Sanchez M, et al:

Beneficial effect of ursodeoxycholic acid in patients with acyl-CoA

oxidase 2 (ACOX2) deficiency-associated hypertransaminasemia.

Hepatology. 76:1259–1274. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Guan Z, Li Y, Hu S, Mo C, He D, Huang Z

and Liao M: Screening and identification of differential

metabolites in serum and urine of bamaxiang pigs bitten by

trimeresurus stejnegeri based on UPLC-Q-TOF/MS metabolomics

technology. J Toxicol Sci. 47:389–407. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|