Introduction

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) has emerged as

a serious clinical complication associated with portal hypertension

(PHT). This condition manifests pathologically as congestive

gastropathy, primarily resulting from compromised venous drainage

in the gastric mucosal circulation (1,2). PHG

predisposes patients to acute or chronic upper gastrointestinal

bleeding, significantly compromising health outcomes and quality of

life. The pivotal pathogenic determinant of PHG is elevated

vascular resistance within the portal system, which drives PHT

(3). PHT induces venous stasis

within gastric circulation, mucosal congestion, and compromised

tissue perfusion, culminating in hypoxia-mediated injury to gastric

epithelial cells (4,5). Various pathway adaptations to hypoxic

conditions, which trigger metabolic adaptations, modulate cell

proliferation and oxidative capacity, and govern inflammatory

responses, are instrumental in detecting low oxygen levels within

cells. These hypoxia-responsive mechanisms have been pathologically

associated with diverse disease processes, including neoplastic

progression, cardiovascular pathophysiology, metabolic

dysregulation syndromes, and gastrointestinal diseases (6,7). In

addition, emerging evidence implicates that the pathogenesis of PHG

is influenced by multifactorial mechanisms, such as dysregulation

of cytokines (including endothelin-1, nitric oxide, prostaglandin

E2, and tumour necrosis factor-α), epithelial apoptosis, disruption

of the mucosal barrier, nonspecific inflammatory responses, and

mitochondrial dysfunction (4,5).

Nevertheless, the precise molecular pathogenesis remains

incompletely elucidated, necessitating further systematic

investigation.

Hypoxia induces structural and functional

adaptations in mitochondria, which exacerbates oxidative stress and

promotes anaerobic glycolysis (8).

Mitochondria, the dominant source of reactive oxygen species (ROS)

production, exhibit a close interplay between mitochondrial

oxidative stress and glycolytic dysfunction (9). ROS are frequently generated as

byproducts during the process of oxidative phosphorylation.

Effective regulation of ROS levels is crucial, as they can

potentially induce oxidative damage to DNA, proteins, and lipids

(10). Glycolysis, a highly

conserved metabolic pathway, serves as the universal initial step

in glucose metabolism. Under hypoxic conditions, glycolysis

facilitates ATP generation through glucose catabolism, yielding

lactic acid as the terminal metabolite (11). Increased ROS and excessive

glycolysis can lead to alterations in cellular function and promote

the occurrence of adverse events such as cell death. Our previous

study has demonstrated that hypoxia-mediated mitochondrial

dysfunction is a critical contributor to PHG pathogenesis (12). However, the potential causative role

of hypoxia-induced ROS overproduction and accelerated glycolytic

flux in the pathogenesis of PHG-associated mucosal injury remains

to be systematically investigated.

Therefore, to elucidate the specific molecular

mechanisms linking hypoxia-induced ROS accumulation and aberrant

glycolytic metabolism in gastric epithelial injury in PHG, gastric

mucosal biopsies from patients with PHG and healthy controls were

analysed to identify transcriptomic and ultrastructural

differences. A murine model of PHT via carbon tetrachloride

administration and an in vitro model using hypoxia-exposed

GES-1 were further established. Utilizing transmission electron

microscopy (TEM), targeted metabolomics, and molecular assays,

mitochondrial morphology, oxidative stress markers, and glycolytic

flux were assessed. Additionally, the ROS scavenger Mito-TEMPO and

the lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) inhibitor oxamic acid sodium

were used to validate the therapeutic potential of targeting these

pathways in preventing mucosal injury. The present study not only

has the potential to reveal the key molecular links of the

hypoxia-metabolism imbalance in PHG, but also to provide novel

experimental evidence for the development of targeted therapeutic

strategies against oxidative stress and abnormal glycolysis in

PHG.

Materials and methods

Clinical tissue specimens

Gastric mucosal biopsy specimens were collected

endoscopically from two groups: i) 10 patients diagnosed with PHG

secondary to hepatitis B virus-related liver cirrhosis, with a mean

age of 55.4±8.05 years, ranging from 43-70 years. Among these 10

patients, 5 (50.0%) were male and 5 (50.0%) were female; and ii) 10

healthy control subjects undergoing routine health examinations at

the Endoscopic Center of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun

Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, P.R. China) with a mean age of

53.6±7.74 years, ranging from 44-66 years. Among these 10 subjects,

5 (50.0%) were male and 5 (50.0%) were female. The study protocol

was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Third

Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University [approval no.

(2021)02-176]. Gastric biopsy specimens, collected from both

healthy controls and patients with PHG, underwent preservation

either by freezing (-80˚C) for molecular biology applications or

through formalin fixation/paraffin embedding for histopathological

evaluation. Written informed consent from the patients was

waived.

Mouse models

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance

with protocols reviewed and approved (approval no. 2022F122) by the

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of South China

Agricultural University (Guangzhou, P.R. China) and conducted in

accordance with relevant guidelines. Experimental groups were

randomly assigned with 92 C57BL/6 mice (male, 6-8 weeks old, 18-20

g), which were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility

under standardized conditions (22±2˚C; 50-60% humidity; 12-h

light/dark cycle). Mice were maintained in individually ventilated

cages with sterilized wood-chip bedding and provided with

autoclaved food and water ad libitum. All experimental

procedures and assessments were performed in a blinded fashion.

Following completion of experimental protocols, all mice were

humanely euthanized via gradual-fill carbon dioxide asphyxiation,

with a volume displacement rate of 70% utilized in our experimental

procedures. Liver cirrhosis with subsequent PHT was induced in mice

via twice-weekly intraperitoneal injections of carbon tetrachloride

(20% v/v in olive oil; Sinopharm Chemical Reagent) at 5 ml/kg body

weight for 16 weeks. Control mice received equivalent volumes of

olive oil alone (5 ml/kg, intraperitoneally) on the same schedule.

To mitigate oxidative stress, mice received intraperitoneal

Mito-TEMPO (10 mg/kg solubilized in PBS; cat. no. HY-112879;

MedChemExpress) every other day. Control groups were administered

PBS alone at equivalent volumes and frequency. For LDHA

suppression, oxamic acid sodium (750 mg/kg in PBS; HY-W013032A;

MedChemExpress) was administered intraperitoneally every other day,

with PBS serving as the vehicle control.

Sample collection

Mice from both the PHT and control groups were

anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg;

intraperitoneal injection) and were humanely euthanized following

anesthetic induction. Their abdomens were opened, and the entire

stomach was carefully dissected. The stomach was repeatedly rinsed

in ice-cold PBS solution to remove any residual contents, and then

longitudinally cut along the greater curvature to expose the

gastric mucosa. After thoroughly rinsing the gastric contents with

ice-cold PBS, gross images were obtained, and the gastric mucosal

injury was scored as follows (12):

0, normal gastric mucosa; 1, gastric mucosal erosion; 2, gastric

mucosal ulcer (<1 mm); 3, gastric mucosal ulcer (1-2 mm); 4,

gastric mucosal ulcer (3-4 mm); 5, gastric mucosal ulcer (>5

mm). Subsequently, the mucosal tissues were collected. A portion

was stored in a -80˚C freezer for subsequent protein extraction.

For paraffin section preparation, a separate portion was fixed in

10% neutral-buffered formalin.

Histopathological staining

Tissue sections (3-µm thick) were prepared for

either hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining or

immunohistochemical/immunofluorescence (IHC/IF) analyses. For

immunostaining, antigen-retrieved tissue sections were incubated

overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies targeting either LDHA

(cat. no. 19987-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) or 4-HNE (cat. nos.

ab46545/ab48506; Abcam), followed by incubation with

species-matched horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary

antibodies (cat. nos. A0208/A0216; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology) at 37˚C for 1.5 h, as previously described (13). IF sections were DAPI-counterstained

to visualize nuclei. Tissue hypoxia distribution was evaluated in

gastric mucosal sections using the Hypoxyprobe-1 Kit (cat. no.

HP3-100Kit; Hypoxyprobe, Inc.) following the manufacturer's

protocol. Briefly, 1 h before anesthetization and sampling, mice

were intraperitoneally injected with a Hypoxyprobe-1 solution at a

dose of 60 mg/kg. Subsequently, the samples underwent fixation,

embedding, and sectioning into 3 µm-thick slices. After incubation

with the IgG1 monoclonal antibody (MAb1; clone 11.23.22.R; supplied

in the Hypoxyprobe-1 Kit, cat. no. HP3-100Kit; Hypoxyprobe, Inc.)

at 4˚C overnight, the sections were incubated with HRP-labeled

anti-rat secondary antibodies (cat. no. A0192; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) at room temperature for 1.5 h, followed by DAB

staining. For primary cells, they were first incubated with a

100-µM Hypoxyprobe-1 solution for 1 h, and then subjected to

permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room

temperature (cat. no. P0096; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology).

After incubating with the IgG1 MAb1 at 4˚C overnight, the cells

were stained with anti-rat secondary antibodies (cat. no. A-11006;

Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C for 1 h. Nuclei were

counterstained with DAPI for 15 min at room temperature prior to

imaging. The quantitative analysis of Hypoxyprobe-1-positive

regions was performed in multiple fields of view (>6 per

sample). The ratio of positive regions to the total area in each

image was quantified using ImageJ software (v1.54 g; National

Institutes of Health), and the area ratio was calculated and

expressed as a percentage. For TEM detection, fresh gastric tissue

samples were immediately fixed in electron microscope fixative

(cat. no. LADE035; LANDM Biotechnology Co., Ltd.; Guangzhou Ruijing

Information Technology Co., Ltd.) at 4˚C overnight (or for at least

4 h). The samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series

(50-100%) followed by 100% acetone, infiltrated, and embedded in

resin (polymerized at 60˚C for 48 h). Ultrathin sections (~100 nm)

were cut using a Leica UC7 ultramicrotome. Sections were stained

with uranyl acetate (cat. no. U25690; Shanghai Acmec Biochemical

Technology Co., Ltd.) for 20 min and lead citrate (cat. no.

L885990; Macklin, Inc.) for 12 min at room temperature and imaged

using a transmission electron microscope (Tecnai G2 Spirit; FEI).

Mitochondrial morphometric analysis was performed by randomly

selecting eight mitochondria per image from each experimental

group. Mitochondrial length and width were quantified using length

parameters, while cross-sectional area was calculated via area

measurement tools.

Cell experiments

For the isolation of primary cells (14), the intact stomach was meticulously

excised and subsequently rinsed with a physiological buffer. The

pyloric region was securely ligated. Following this, the stomach

was perfused via the cardia using calcium-free Hank's Balanced Salt

Solution for a duration of 15 min to facilitate tissue preparation.

Following the initial perfusion, the stomach was subjected to

further enzymatic digestion by perfusion with 100 ml of a digestion

solution containing 0.2% pronase and 0.2% collagenase type IV (both

from Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KGaA). After enzymatic treatment, the

mucosal layer was carefully dissected and collected to generate a

single-cell suspension. The resulting suspension was then passed

through a 100-µm nylon mesh filter to remove undigested tissue

fragments and ensure a homogeneous cell population. The cell

suspension was centrifuged at 300 x g for 15 min to separate

cellular components. Following centrifugation, the resulting pellet

was carefully harvested for subsequent isolation of gastric

epithelial cells. A 30% Percoll solution (Sigma-Aldrich; Merck

KGaA) was prepared according to the manufacturer's protocol. The

cellular pellet was then carefully layered onto the Percoll density

gradient and centrifuged at 450 x g for 20 min at 4˚C to isolate

viable gastric epithelial cells. Primary cells were maintained in

RPMI-1640 medium (cat. no. 11875093; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Inc.) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum

(cat. no. A5256701; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and

antibiotic-antimycotic solution (cat. no. 15240062; Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc.). Incubation was carried out at 37˚C in a

humidified chamber with 5% CO2 tension. For comparative

purposes, the GES-1 human gastric epithelial cell line was grown

under identical conditions, as previously established (15). For the hypoxia group, the cells were

switched to low-glucose culture medium and incubated in a tri-gas

incubator (1% oxygen, 5% CO2, 94% nitrogen) for 24 h.

The normoxia group was cultured in normal medium in a

CO2 incubator for 24 h. The working concentrations of

Mito-TEMPO and oxamic acid sodium were both set at 10 µmol/l. Using

the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; cat. no. C0038; Beyotime Institute

of Biotechnology) assay, cellular viability across experimental

groups was systematically measured and compared after incubating

the cells with the reagent for 1.5 h at 37˚C as per the

manufacturer's instructions.

Western blotting

Total protein extracts from mucosal tissues or

isolated cells were subjected to western blot analysis following

established protocols (14,15). These protein extracts were obtained

using a total protein extraction kit (cat. no. PC201; Shanghai

EpiZyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.). Protein concentration was

determined using the BCA protein assay kit (cat. no. ZJ102;

Shanghai EpiZyme Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.). A total of 20 µg

of protein was loaded per lane and separated on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel.

Proteins were subsequently transferred to a polyvinylidene

difluoride membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% milk in TBST

at room temperature for 1.5 h. Washing was performed three times

for 5 min each, using TBST containing 0.1% Tween-20. Membranes were

incubated overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies against LDHA

(cat. no. 19987-1-AP; Proteintech Group, Inc.) and β-actin (cat.

no. sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), with β-actin serving

as the loading control. Protein bands were detected using enhanced

chemiluminescence (ECL; cat. no. E423-02; Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd.)

after HRP-secondary antibody incubation (cat. no. RM3001/3002,

Beijing Ray Antibody Biotech) for 1 h at room temperature. Signal

acquisition was performed digitally, with band intensity

quantification conducted using ImageJ (v1.54 g; National Institutes

of Health).

ATP measurement

Gastric tissues (20 mg) were homogenized in 200 µl

of the ATP detection lysis buffer supplied with the Enhanced ATP

Assay Kit (cat. no. S0027; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology)

using the Bead Ruptor 12 Homogenizer (Omni International, Inc.).

The homogenates were centrifuged (12,000 x g, 5 min, 4˚C), and the

supernatant was collected. Protein concentration was determined

using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (cat. no. ZJ102; Shanghai EpiZyme

Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, a 20-µl aliquot of

the supernatant was mixed with 100 µl of the ATP detection working

solution, and luminescence (RLU) was measured using a microplate

luminometer (Agilent BioTek Synergy H1 Microplate Reader; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) with a 2 sec delay and 10 sec integration time.

ATP concentrations were calculated based on a standard curve (0,

2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 50 µM) and normalized to protein

concentration (nmol/mg protein). Samples and standards were run in

triplicate.

Microarray analysis

The microarray experiment followed the same protocol

as previously described (14). The

microarray experiment was performed using the Agilent SurePrint G3

Human Gene Expression Microarray 8x60K platform (G4851B; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Total RNA quality and quantity were assessed

via Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer; samples with an RNA Integrity Number

(RIN) ≥7.0, concentration ≥50 ng/µl, and 28S/18S ratio ≥1.8 were

used. Labeling was conducted using the Agilent Low Input Quick Amp

Labeling Kit (part no. 5190-2305; Agilent Technologies, Inc.)

following the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, double-stranded

cDNA was synthesized using AffinityScript Reverse Transcriptase

(supplied in the Agilent Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit; part no.

5190-2305; Agilent Technologies, Inc.) and a T7 promoter primer

(supplied in the Agilent Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit; part no.

5190-2305; Agilent Technologies, Inc.). This was followed by in

vitro transcription (IVT) with T7 RNA Polymerase at 37˚C for 14

h to generate cRNA labeled with Cy3-CTP. Hybridization was carried

out in an Agilent hybridization oven (Model G2545A; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.) at 65˚C for 17 h using the Agilent Gene

Expression Hybridization Kit (part no. 5188-5242; Agilent

Technologies, Inc.). Subsequent data processing was conducted with

GeneSpring GX version 12.0 (Agilent Technologies, Inc.), which

executed data aggregation and normalization procedures.

Differential gene expression analysis employed the following

selection criteria: i) Absolute value of expression ratio

≥1.5-fold; ii) statistical significance threshold set at P<0.05

after Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate adjustment. The

expression data were log2-transformed and hierarchically clustered

via CLUSTER 3.0 (http://bonsai.hgc.jp/~mdehoon/software/cluster/)

Adjust Data function. Subsequently, the resulting dendrogram was

visualized with Java TreeView (v1.2.1; http://jtreeview.sourceforge.net/) for further

analysis. Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis was performed

using the clusterProfiler R package (v4.14.6; https://bioconductor.org/packages//release/bioc/html/clusterProfiler.html).

GO terms with an adjusted P-value <0.05 were considered

statistically significant. The results were visualized using bubble

plots.

Energy metabolic analysis

Energy metabolism was profiled using a targeted

metabolomics platform [UPLC-MS/MS; Metabo-Profile Biotechnology

(Shanghai) Co., Ltd.] on gastric tissue. Specifically, 10 mg of

frozen sample was homogenized with ultrapure water and ceramic

grinding beads (cat. no. F6632; Beyotime Institute of

Biotechnology), and then extracted using methanol containing

internal standards. The samples were centrifuged at 18,000 x g for

15 min at 4˚C (Microfuge 20R; Beckman Coulter, Inc.). Following

centrifugation, metabolites were derivatized with

3-nitrophenylhydrazine and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)

carbodiimide at 30˚C for 60 min. Chromatographic separation was

performed on a BEH C18 column (2.1x100 mm, 1.7 µm; 40˚C) with a

gradient of mobile phase A (5 mM DIPEA aqueous solution) and mobile

phase B (acetonitrile/isopropanol, 7:3, v/v) at 0.3 ml/min. MS

detection was carried out in negative ESI mode (capillary voltage,

3 kV; source temperature: 150˚C; desolvation temperature, 500˚C).

Data were acquired on a Waters ACQUITY I UPLC/Xevo TQ-S system and

processed with MassLynx (v4.1; Waters Corporation). Metabolite

levels were normalized to sample weight, and missing values were

imputed as one tenth of the minimum for each metabolite. Subsequent

analyses, including principal component analysis (PCA) and

orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA),

were performed using iMAP [v1.0; Metabo-Profile

Biotechnology(Shanghai) Co., Ltd.]. Differentially expressed

metabolites were identified based on variable importance in

projection ≥1 (from OPLS-DA) and P<0.05 from univariate

tests.

Determination of oxidative stress

Cellular ROS production was assessed using DCFH-DA

(cat. no. S0033S; Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology). The primary

gastric epithelial cells were cultured to approximately 60-70%

confluence and subjected to the treatments. Subsequently, the cells

were incubated with DCFH-DA (diluted 1:1,000 in RPMI-1640 medium)

for 20 min at 37˚C. After probe incubation, oxidative conversion to

fluorescent DCF was measured at 488/525 nm excitation/emission.

Mitochondrial superoxide was assessed by seeding cells in confocal

dishes overnight. Cells were then stained with 5 µM MitoSOX™ Red

(cat. no. M36008; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37˚C for 20

min (in the dark). Subsequently, the cells were gently washed three

times with warm PBS, followed by Hoechst 33258 (cat. no. C1017;

Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology) nuclear counterstaining at

room temperature for 20 min for localization. Fluorescence imaging

was performed using a Zeiss LSM880/800 confocal microscope (Imager

Z2; Zeiss AG). Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) was extracted with the

AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (cat. no. 80204; Qiagen) from the

mitochondrial fraction of cells, and oxidative damage was assessed

via 8-hydroxy-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) quantification using the

OxiSelect™ Oxidative DNA Damage ELISA Kit (cat. no. STA-320; Cell

Biolabs, Inc.). Prior to the assay, extracted mtDNA samples were

dissolved and normalized to a uniform concentration of 1 mg/ml.

Following enzymatic digestion, a total of 50 µg of processed mtDNA

was loaded per reaction (50-µl volume). The 8-OHdG content was

determined by comparison with a predetermined standard curve (0-20

ng/ml) and is reported as ng/ml.

Statistical analysis

All results were consistently reproduced in at least

three independent experiments. Representative data from distinct

biological replicates were selected for visualization in figures

(for example microscopy images, immunoblots). Quantitative data are

reported as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). All

statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software

(version 9.5; Dotmatics). Comparisons between two groups were

analyzed using Student's two-tailed paired t-test.

Comparisons of single-factor data among more than two groups were

analyzed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), while

comparisons of two-factor data among more than two groups were

analyzed using two-way ANOVA. When the F-value was <0.05,

Bonferroni's post hoc multiple comparison test was performed. A

value of P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically

significant difference.

Results

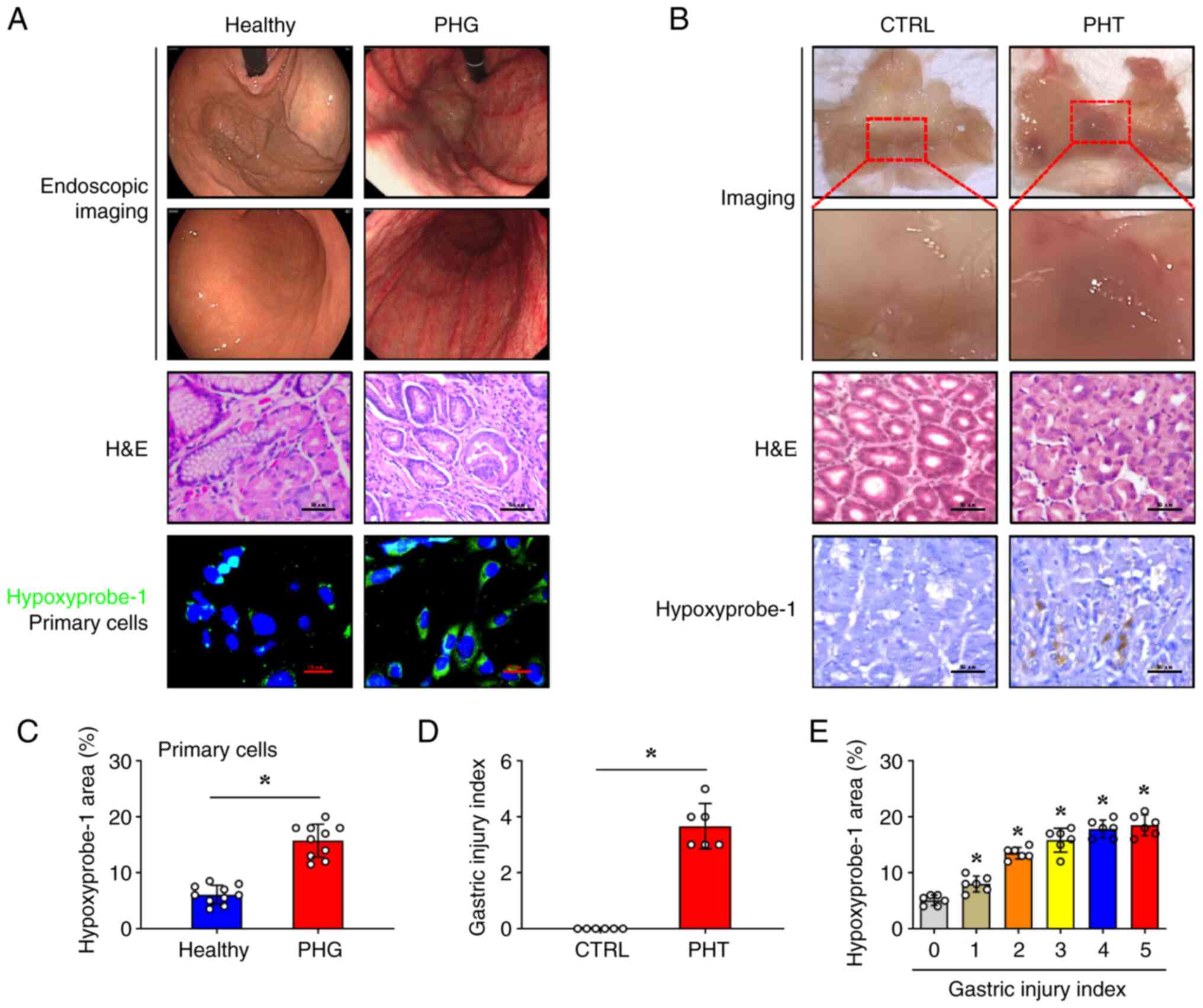

Hypoxia participates in the gastric

mucosal injury of PHG in both humans and mice

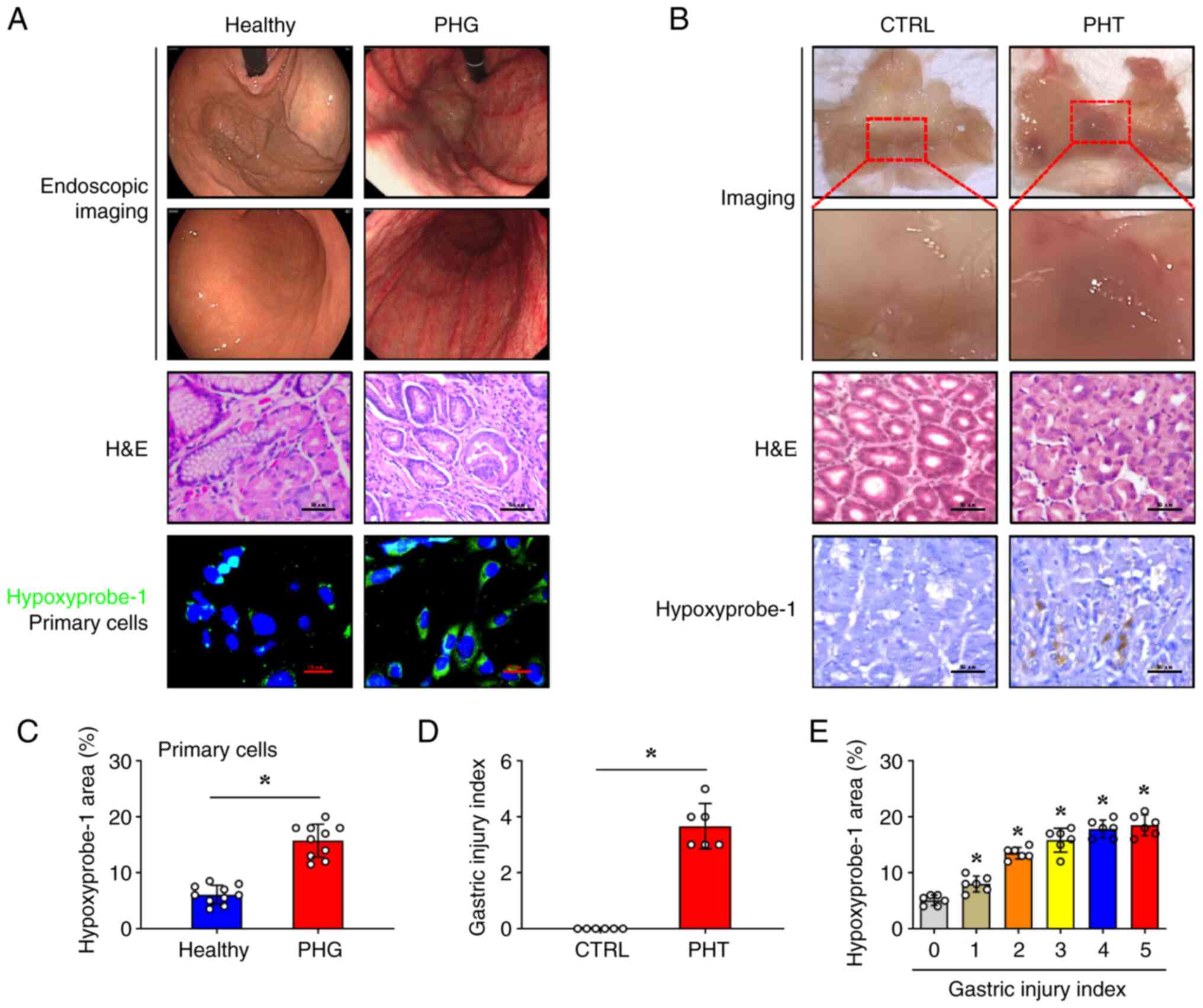

To evaluate hypoxia in PHG pathogenesis, gastric

mucosal biopsies were obtained from patients who had PHG confirmed

by endoscopy, and a murine PHG model induced by PHT was developed.

Endoscopic assessment demonstrated significant mucosal

abnormalities in patients with PHG, including diffuse erythema,

vascular congestion, and oedema, which were absent in healthy

controls (Fig. 1A).

Histopathological analysis of gastric mucosal biopsies using

H&E staining demonstrated epithelial cell damage, focal

haemorrhages, and submucosal venular ectasia in the PHG group

(Fig. 1A). Hypoxyprobe-1

fluorescence signals were significantly enhanced in primary gastric

mucosal epithelial cells isolated from these tissues in the PHG

group (Fig. 1A and C). In the PHT mouse model, gross

examination showed marked mucosal congestion and even erosive

haemorrhage (Fig. 1B). Similar to

the clinical samples from the PHG group, the mice with PHT

exhibited significant epithelial cell damage, which was associated

with an elevated mucosal injury index (Fig. 1B and D). Moreover, the Hypoxyprobe-1 signal in

the PHT group was enhanced, which was positively associated with

the gastric injury index of mice with PHT (Fig. 1B and E). Collectively, these findings

demonstrated that hypoxia serves as a pathogenic factor

contributing to gastric mucosal injury in PHG.

| Figure 1Hypoxia participates in gastric

mucosal injury of PHG in both humans and mice. (A) Representative

gastric endoscopic images and H&E-stained sections of gastric

mucosa from patients with PHG were compared with those from healthy

individuals (as Healthy). Scale bar, 50 µm for H&E images.

Hypoxyprobe-1 staining (green) was performed on primary gastric

mucosal epithelial cells isolated from both PHG patients and

healthy controls. Nuclei (blue) were counterstained with DAPI.

Scale bar, 10 µm. (B) Gross image, H&E staining, and

Hypoxyprobe-1 immunohistochemical staining (brown) of the gastric

mucosa in the mice with PHT compared with that in the control mice.

Scale bar, 50 µm for H&E and IHC images. (C) Quantitative

analysis of Hypoxyprobe-1 fluorescence intensity from (A), n=10 per

group; *P<0.05. (D) Mucosal injury index analysis in

the murine models is presented, n=6 per group;

*P<0.05. (E) The percentage of the

Hypoxyprobe-1-positive area corresponding to the gastric injury

index of PHT mouse models was analyzed. n=6 per group;

*P<0.05 vs. the group with a gastric injury index of

0. PHG, portal hypertensive gastropathy; H&E, hematoxylin and

eosin; DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; PHT,

portal hypertension; CTRL, control. |

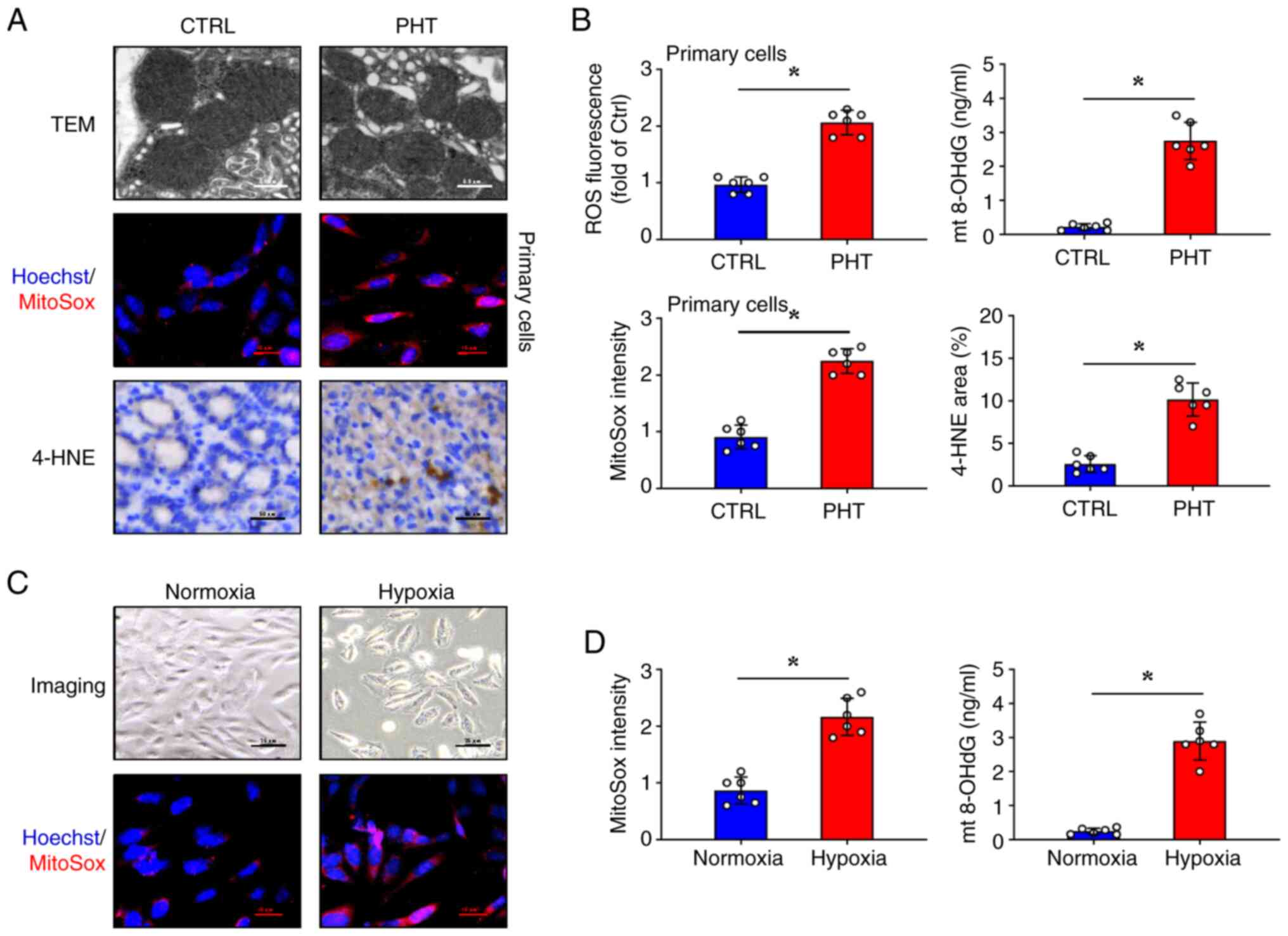

Enhanced mitochondrial oxidative

stress is identified in the gastric mucosa epithelia of PHG

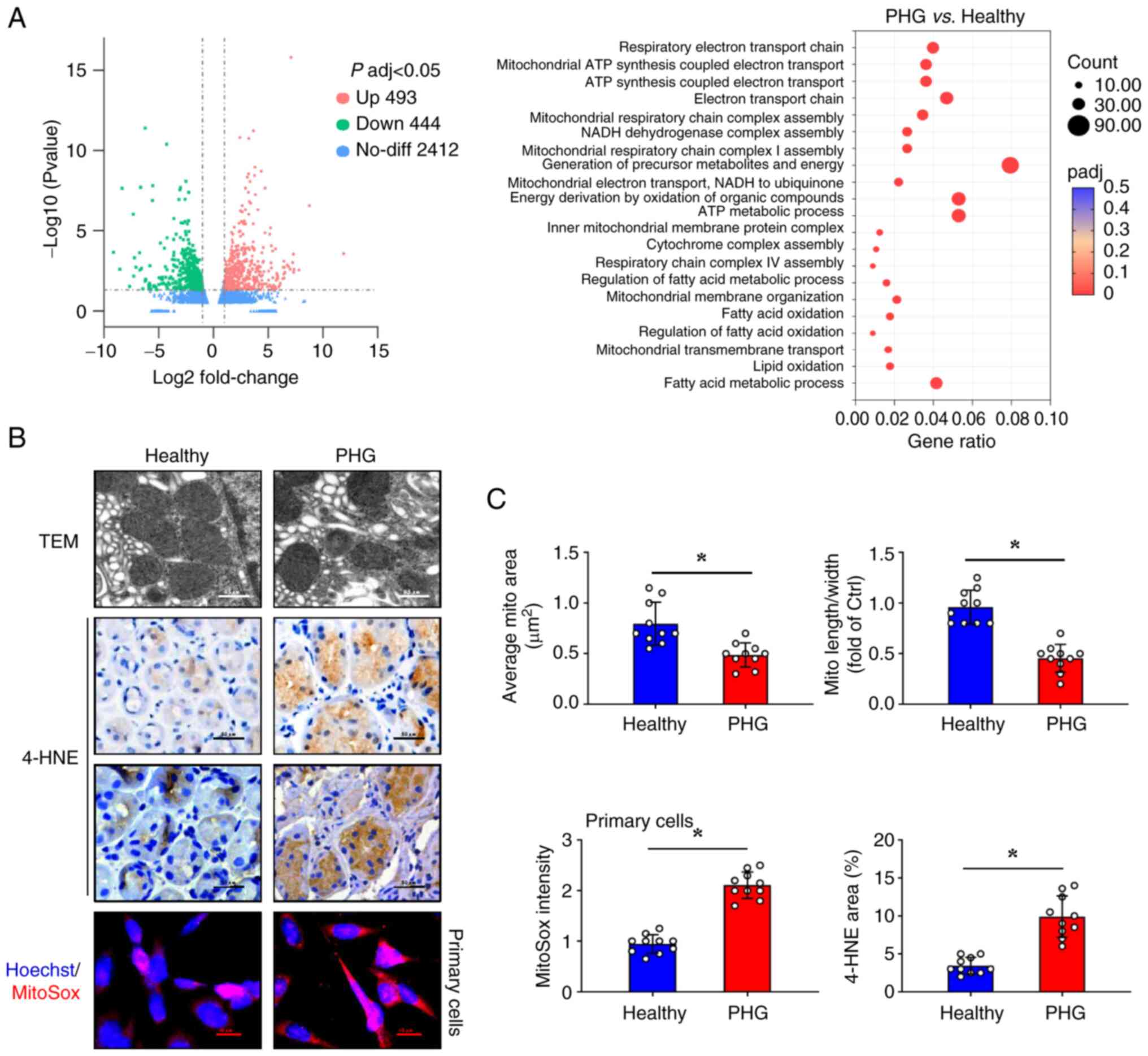

To characterize the molecular alterations in PHG

pathogenesis, microarray analysis was conducted on gastric mucosal

biopsies obtained from both patients with PHG and healthy control

subjects. Comparative transcriptomic analysis revealed significant

differential gene expression profiles between PHG and normal

gastric mucosa (Fig. 2A).

Furthermore, Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis demonstrated

upregulation of mitochondrial structural components (including

‘mitochondrial respiratory chain complex assembly’, ‘NADH

dehydrogenase complex assembly’, ‘inner mitochondrial membrane

protein complex’, and ‘mitochondrial membrane organization’) and

oxidative respiration (including ‘generation of precursor

metabolites and energy’, ‘energy derivation by oxidation of organic

compounds’, ‘respiratory electron transport chain’, and

‘mitochondrial ATP synthesis coupled electron transport’) in PHG

specimens (Fig. 2A). TEM analysis

identified ultrastructural mitochondrial abnormalities in the PHG

mucosa, including reduced mitochondrial size and decreased

mitochondrial cristae. The quantitative assessment indicated

decreases in the mean mitochondrial area as well as the

length-to-width ratio (Fig. 2B and

C). Immunohistochemical staining

showed that PHG tissues had elevated expression of 4-HNE, a lipid

peroxidation marker (Fig. 2B and

C). Consistently, primary gastric

epithelial cells from patients with PHG exhibited stronger MitoSox

fluorescence signals than those from healthy controls (Fig. 2B and C), indicating increased mitochondrial

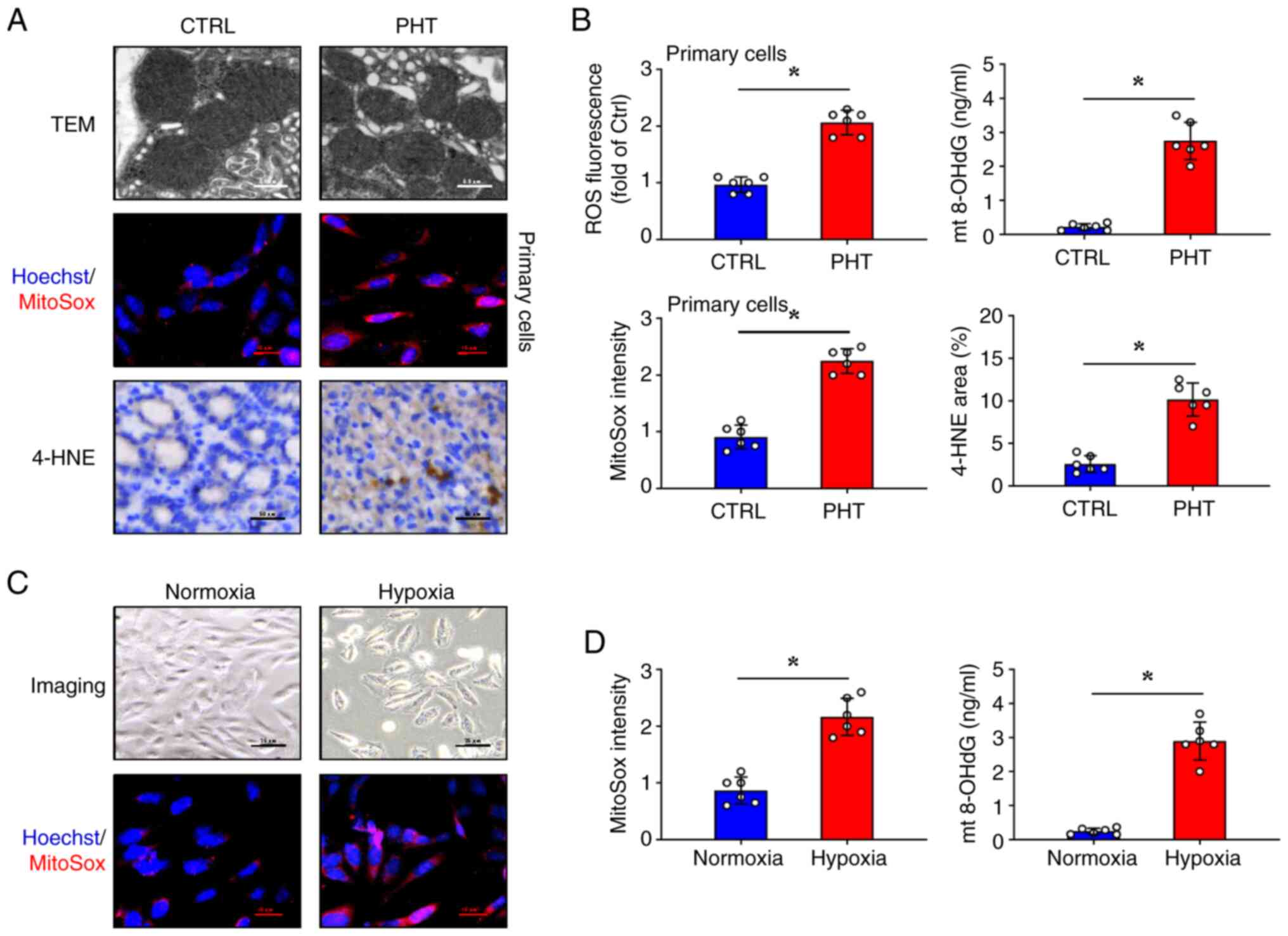

superoxide production. PHT mouse models were established, and it

was verified that TEM analysis of gastric mucosa from mice with PHT

recapitulated clinical findings, demonstrating mitochondrial

shrinkage, damage, and cristae loss compared with the control mice

(Fig. 3A). In addition to the

increased MitoSox signalling and increased intracellular ROS levels

in the primary gastric epithelial cells, in mice with PHT, the

gastric mucosa also exhibited significantly increased 4-HNE

expression and elevated mitochondrial 8-OHdG (mt 8-OHdG)

concentrations (Fig. 3A and

B). Furthermore, the effects of

hypoxia were explored on the human gastric epithelial cell line

(GES-1) at the cellular level. Significant morphological changes

were observed in GES-1 cells under hypoxic conditions compared with

the controls, including reduced cell volume, enlarged central pale

areas, and increased cell death (Fig.

3C). Enhanced MitoSox signals and increased mt 8-OHdG

concentrations demonstrated that hypoxia induced mitochondrial

oxidative stress in GES-1 cells (Fig.

3C and D). In summary, these

findings indicated that mitochondrial structural alterations and

oxidative stress escalation observed in the gastric mucosa

contribute to the pathogenesis of PHG.

| Figure 3Mitochondrial oxidative stress is

enhanced in the in vivo and in vitro models. (A) TEM

analysis of mitochondrial morphological changes (Scale bar, 0.5

µm), MitoSox staining of primary gastric mucosal epithelial cells

(Scale bar, 10 µm), and immunohistochemical staining for 4-HNE were

performed in the gastric mucosal tissues from both control and PHT

group mice (Scale bar, 50 µm). Nuclei (blue) were counterstained

with Hoechst 33258 in MitoSox staining.(B) The quantitative

analysis of ROS fluorescence in primary gastric mucosal epithelial

cells and mt 8-OHdG concentration were determined. The MitoSox

fluorescence intensity and the quantitative analysis of 4-HNE

staining from (A) were also analyzed. n=6 per group;

*P<0.05. (C) Morphology and MitoSox fluorescence

staining of GES-1 cells under normoxic and hypoxic conditions.

Nuclei (blue) were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 in MitoSox

staining. Scale bars, 25 µm (upper panels) and 10 µm (lower

panels). (D) The mt 8-OHdG concentration and the quantitative

analysis of MitoSox fluorescence intensity in GES-1 cells under

normoxic and hypoxic conditions are shown. n=6 per group;

*P<0.05. TEM, transmission electron microscopy; PHT,

portal hypertension; mt 8-OhdG, mitochondrial 8-OhdG; CTRL,

control. |

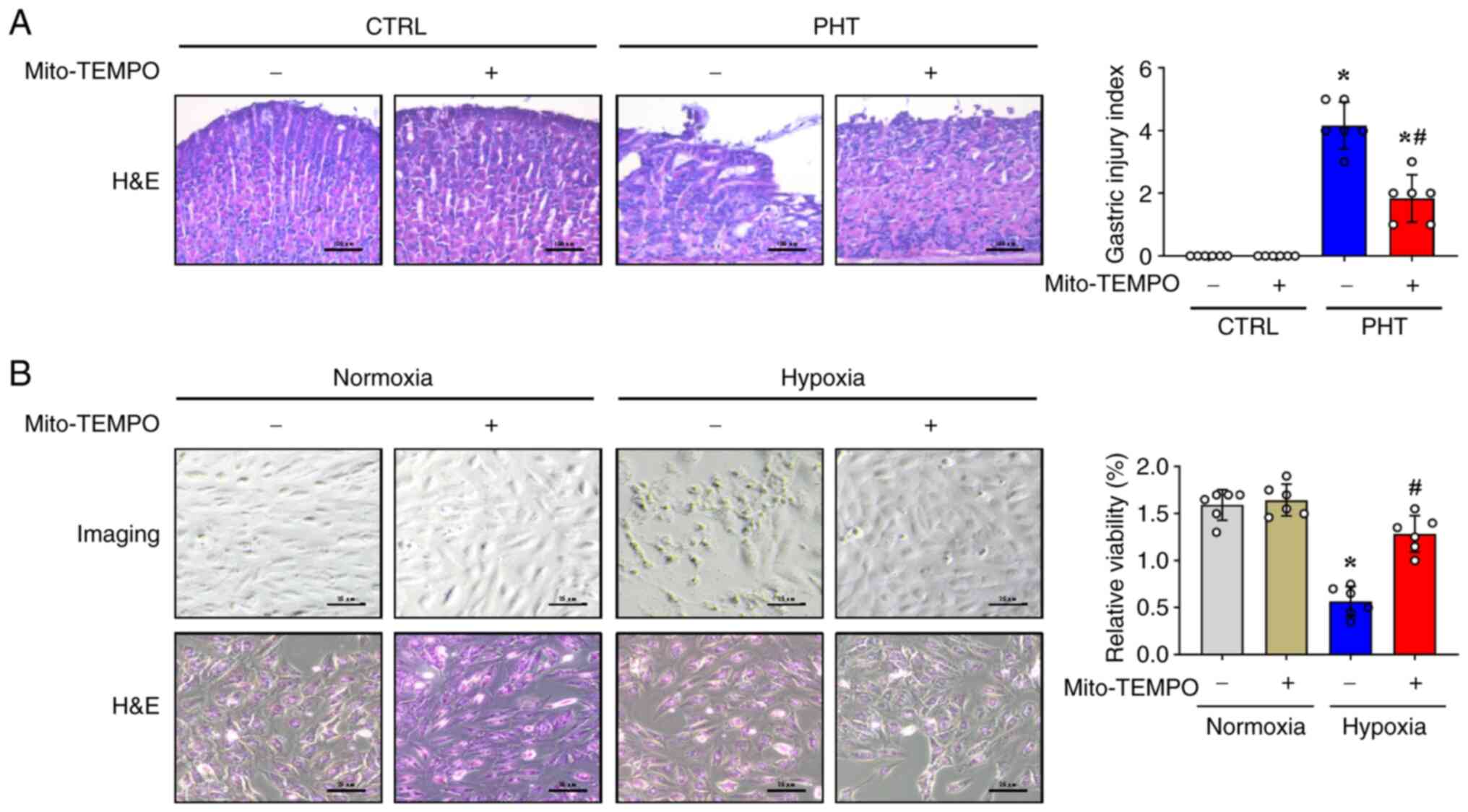

Mito-TEMPO attenuates gastric mucosal

epithelial damage in in vivo and in vitro models

The ROS scavenger Mito-TEMPO, which is an

antioxidant targeted to mitochondria, was used to investigate the

therapeutic potential of mitochondrial oxidative stress inhibition

(12). H&E staining revealed

that Mito-TEMPO relieved gastric mucosal injury, with decreased

inflammatory cell infiltration and attenuated capillary dilation in

mice with PHT (Fig. 4A). However,

no significant differences were observed in the gastric mucosa of

control mice treated with or without Mito-TEMPO (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, when used in the

in vitro cell model under normoxic and hypoxic conditions,

histological and cell viability analyses revealed that Mito-TEMPO

was able to restore the morphological alterations and increase the

relative cell viability in GES-1 cells under hypoxic conditions

(Fig. 4B), and Mito-TEMPO did not

affect the status of GES-1 cells under normoxic conditions

(Fig. 4B). These findings

demonstrated that mitochondrial-derived oxidative stress

contributes to both PHT-induced gastric mucosal damage and hypoxic

cellular injury. Notably, the mitochondrial-targeted antioxidant

Mito-TEMPO alleviated these pathological changes in murine models

and in vitro systems.

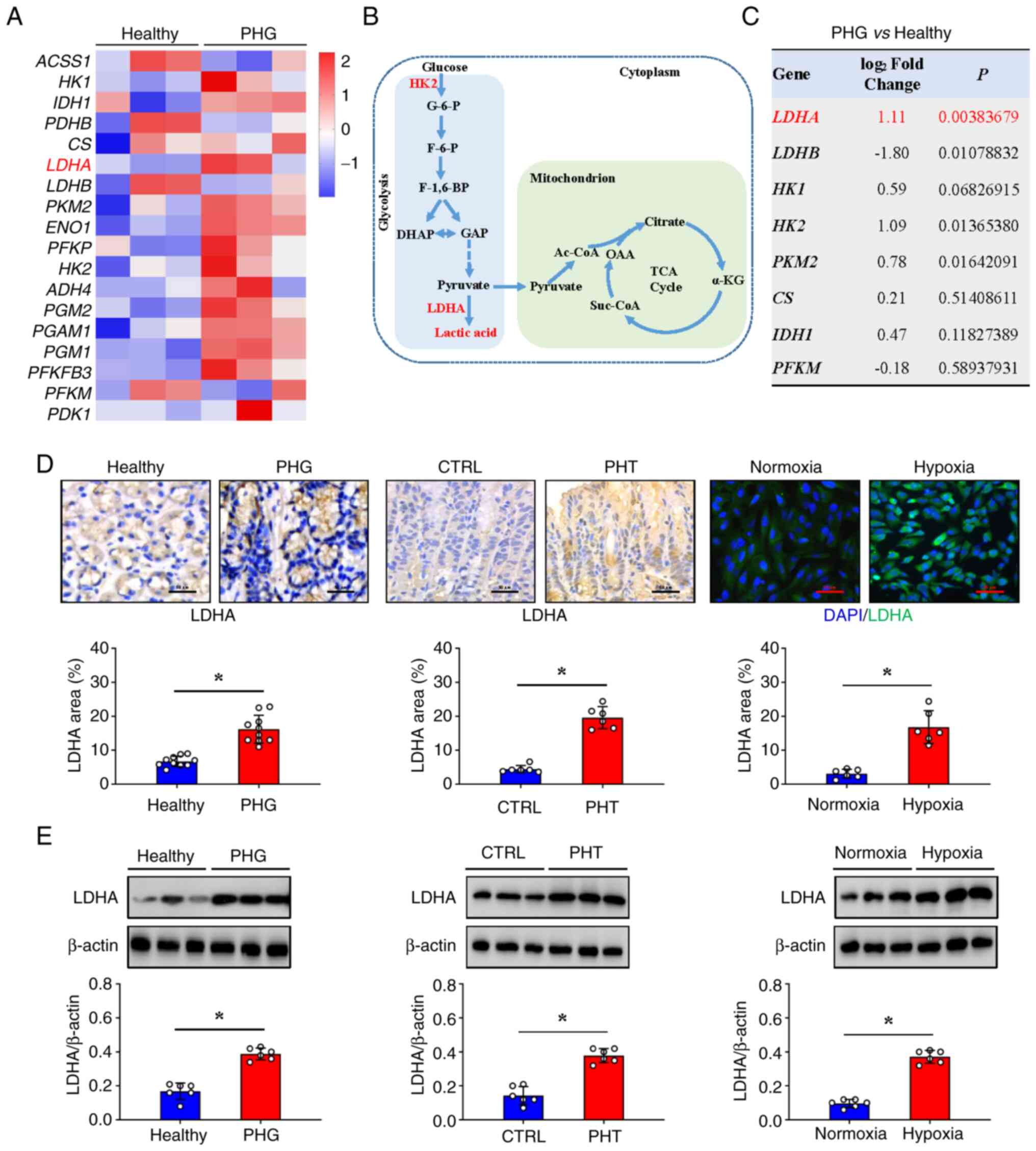

Mitochondrial oxidative stress is

associated with LDHA upregulation, which impairs ATP production and

promotes lactic acid production

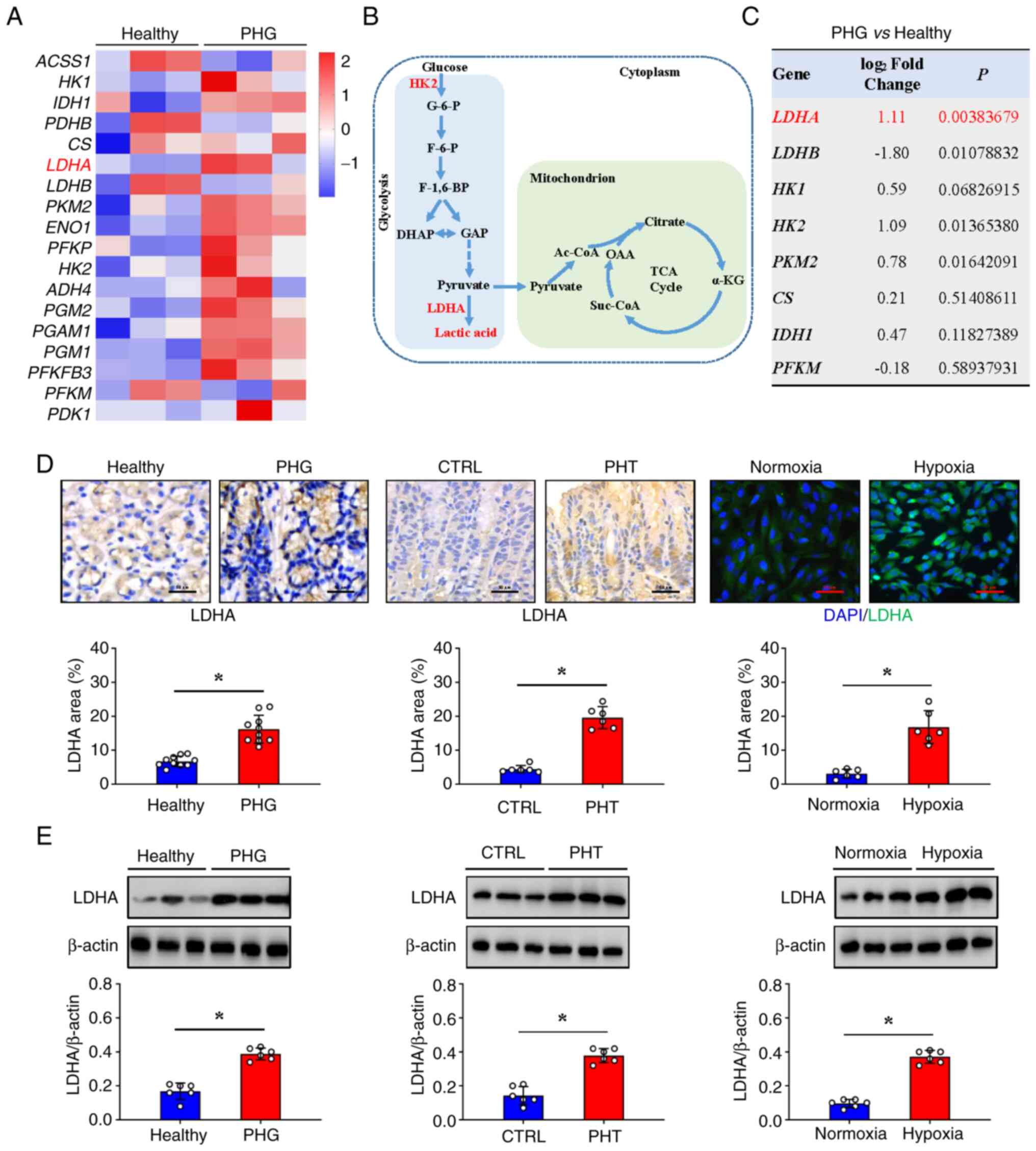

Microarray analysis of clinical gastric mucosal

biopsies revealed significant differential expression of glycolytic

pathway-related genes between patients with PHG and healthy

controls. Moreover, the expression of glycolysis-related genes in

the glycolytic metabolic pathway, such as hexokinase-2

(HK2), LDHA, and pyruvate kinase isozyme type

M2 (PKM2), was increased in the gastric mucosa of

patients with PHG (Fig. 5A).

Genomic metabolic pathway analysis confirmed the enrichment of

genes that were differentially expressed in the glycolytic process,

with LDHA exhibiting the most pronounced increase in transcription

(Fig. 5B and C). Histological staining revealed that the

protein expression of LDHA was consistent with the results of

microarray analysis and was significantly upregulated in the

patients with PHG and the mice with PHT (Fig. 5D). Moreover, the protein expression

of LDHA increased in the GES-1 cell model following hypoxia

(Fig. 5D). Furthermore, western

blot analysis revealed a similar trend in LDHA expression in the

three different sections (Fig. 5E).

These findings established that mitochondrial dysfunction may drive

LDHA upregulation to facilitate glycolytic adaptation to

bioenergetic stress under hypoxia.

| Figure 5Mitochondrial dysfunction is

associated with the glycolytic LDHA upregulation in PHG. (A) The

heatmap analysis of differentially expressed genes between normal

gastric mucosa (healthy individuals-indicated as Healthy) and

gastric mucosa from patients with PHG (indicated as PHG) revealed

increased expression of LDHA and other genes involved in the

glycolytic metabolic pathway. (B) The glycolytic metabolic pathway

is presented. (C) The fold changes and P-values of the indicated

mRNAs in PHG tissues relative to those in normal (healthy

individuals-indicated as Healthy) tissues from the microarray

experiment are presented. (D) Immunohistochemical (brown) or

immunofluorescence (green) staining and quantitative analysis of

LDHA in the clinical tissue samples (n=10 per group), mouse models

(n=6 per group), and cellular hypoxia models (n=6 per group).

Nuclei (blue) were counterstained with DAPI in immunofluorescence

staining. Scale bars, 50 µm (IHC images) and 25 µm (IF images).

*P<0.05. (E) Western blotting detection of LDHA

protein expression levels in clinical tissue samples, mouse models,

and cellular hypoxia models. Ratios of densitometric units of

normalized LDHA/β-actin were determined from western blotting. n=6

per group. *P<0.05. PHG, portal hypertensive

gastropathy; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; DAPI,

4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride; CTRL, control; PHT,

portal hypertension. |

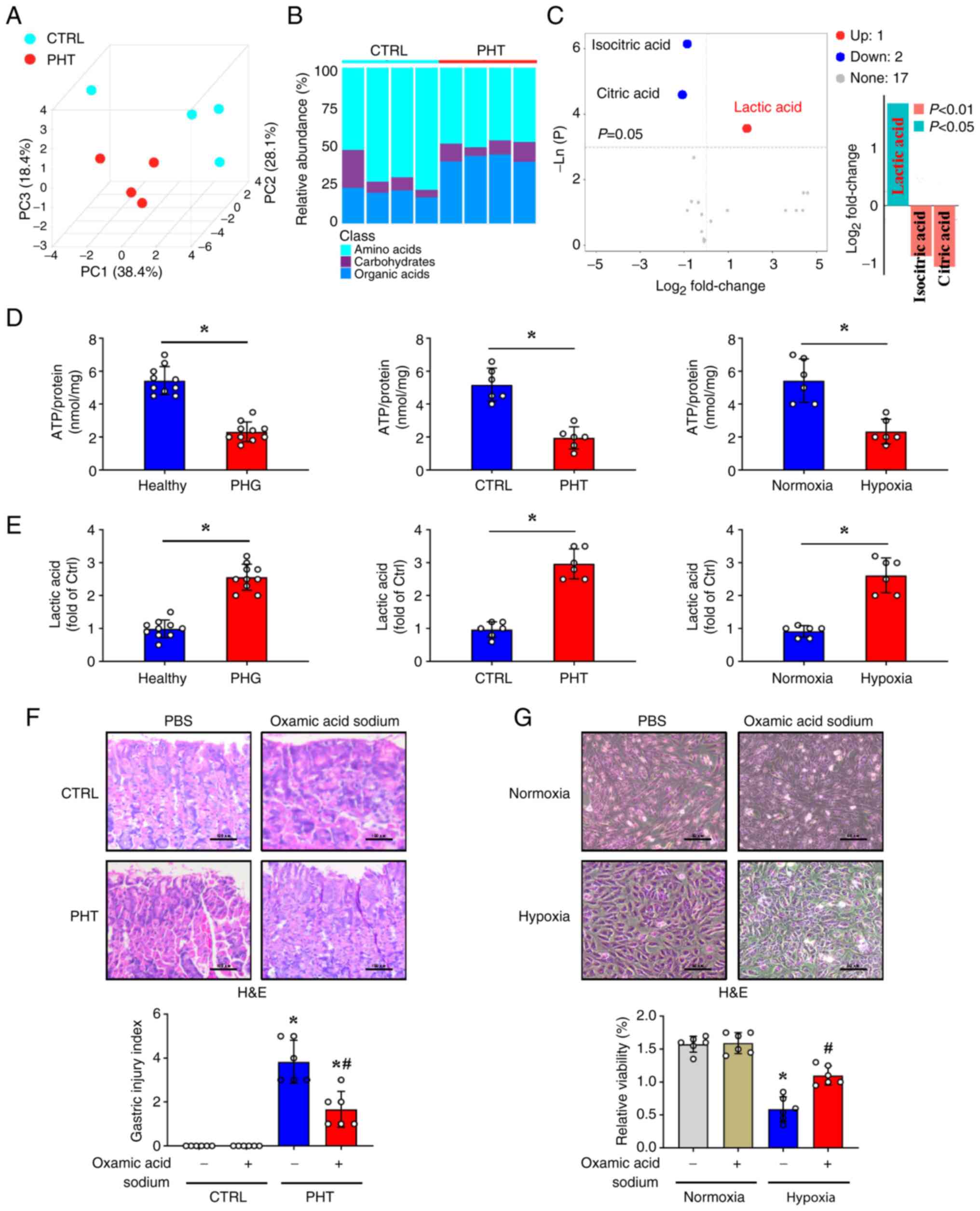

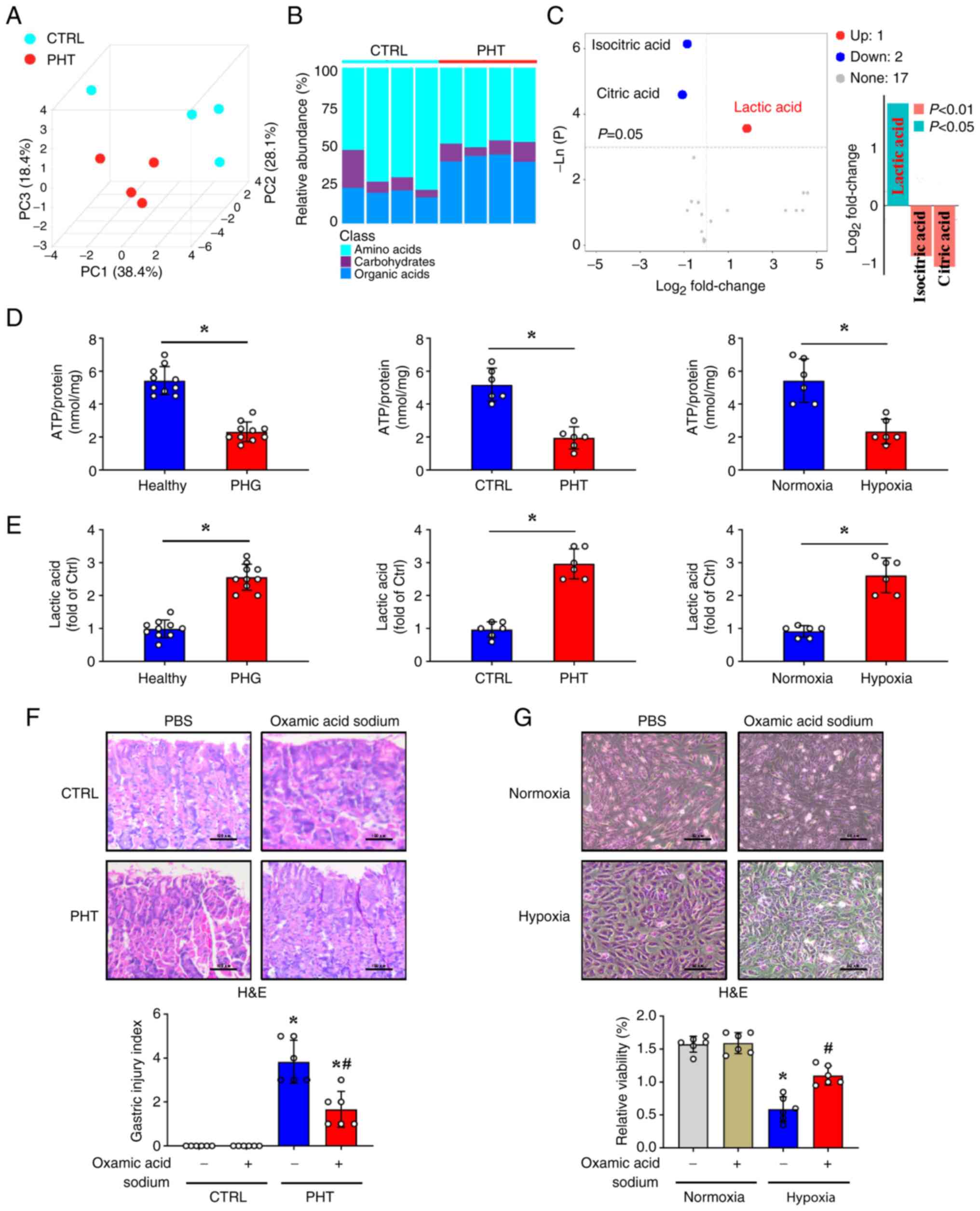

Given the established roles of mitochondrial

oxidative stress in PHG pathogenesis and hypoxia-induced LDHA

upregulation in glycolytic reprogramming, energy metabolic analysis

of gastric mucosal tissues was performed to systematically

characterize the associated metabolic alterations. Distinct

clustering patterns were observed between the PHT and control

groups using PCA (Fig. 6A).

Metabolomic profiling revealed significant alterations in gastric

mucosal metabolism, with mice with PHT exhibiting elevated organic

acid metabolism and reduced carbohydrate metabolism compared with

the control mice (Fig. 6B). Among

these findings, the increase in the lactic acid concentration was

the most significant (Fig. 6C).

Because increased glycolysis can inhibit normal cellular aerobic

oxidation and lead to reduced ATP production, the ATP levels were

assessed and it was revealed that ATP levels were decreased in

samples from patients with PHG, mice with PHT, and hypoxic GES-1

cells (Fig. 6D), whereas lactic

acid concentrations were elevated in these groups (Fig. 6E). The LDHA inhibitor oxamic acid

sodium alleviated the gastric mucosal damage in mice with PHT

(Fig. 6F). Similarly, oxamic acid

sodium reversed the morphological changes and increased the

relative cell viability of GES-1 cells under hypoxic conditions

(Fig. 6G). It is therefore

concluded that the mitochondrial oxidative stress that follows

PHT-mediated hypoxia impairs ATP production while contributing to

increases in ROS production and LDHA-mediated lactic acid, thus

promoting mucosal epithelial injury in the PHG (Fig. 7).

| Figure 6Mitochondrial oxidative stress in PHG

is accompanied by ATP production and promotes lactic acid

production. (A) Principal component analysis of metabolic

components in gastric mucosal tissues from the control group and

mice with PHT. n=4 per group. (B) Stacked bar plots comparing the

relative abundance of amino acid metabolism, carbohydrate

metabolism, and organic acid metabolism in the gastric mucosal

tissues between the control group and PHT mice. (C) Volcano plot

and bar chart analyses of carbohydrate metabolism biomarkers in the

indicated gastric mucosal tissues. (D) The ATP concentrations in

the clinical tissue samples (n=10 per group), murine models (n=6

per group), and cellular hypoxia models (n=6 per group) were

analyzed. *P<0.05. (E) The lactic acid concentrations

in clinical tissue samples (n=10 per group), mouse models (n=6 per

group), and cellular hypoxia models (n=6 per group) were assessed.

*P<0.05. (F) H&E staining and gastric mucosal

injury index scores in the indicated mouse models (treated with

lactate dehydrogenase A inhibitor oxamic acid sodium or not) were

determined. Scale bar, 100 µm. n=6 per group. *P<0.05

vs. the control group; #P<0.05 vs. the PHT group

without oxamic acid sodium. (G) H&E staining of the GES-1 cell

models under normoxia and hypoxia following oxamic acid sodium

administration. Cell viability from the indicated groups was also

analyzed by Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. Scale bar, 50 µm. n=6 per

group. *P<0.05 vs. the normoxia group;

#P<0.05 vs. the hypoxia group without oxamic acid

sodium. PHG, portal hypertensive gastropathy; PHT, portal

hypertension; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; CTRL, control; PBS,

phosphate-buffered saline. |

Discussion

PHG represents a significant complication of both

cirrhotic and noncirrhotic PHT (1).

The condition is clinically defined by a portal pressure gradient

exceeding 5 mmHg, measured as the pressure differential between the

portal vein and hepatic veins (16). In cirrhotic cases, this haemodynamic

alteration primarily stems from architectural distortion of the

hepatic parenchyma and subsequent intrahepatic vascular resistance.

PHT disrupts blood flow and leads to tissue hypoxia, which

compromises mitochondrial integrity and triggers downstream

metabolic dysregulation to exacerbate the gastric mucosal

epithelial injury; the PHT-related PHG gastric mucosal lesions are

commonly defined as complications in patients with PHT (5). PHG imposes a significant burden on

health care systems and substantially reduces the quality of life

of patients. Prior studies have demonstrated that hypoxia

stabilizes hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), increasing its

transcriptional activity and promoting disease progression in

gastric cancer and other related disorders (12,17,18).

Hypoxia is closely linked to gastric mucosal damage and serves as a

hallmark of gastric mucosal pathologies, spanning from inflammatory

reactions to malignancies (17,19).

Among these, PHG is the most representative benign lesion driven by

hypoxia (20).

To assess the hypoxic state of the gastric mucosa in

PHG induced by PHT, gastric tissue samples were collected from

patients with an endoscopic diagnosis of PHG. Additionally, an

experimental mouse model of PHT-associated PHG was established to

investigate the underlying mechanisms involved. Using a

Hypoxyprobe-1 detection kit, it was found that the hypoxic state in

the gastric mucosa appeared in the gastric mucosal epithelia

following PHT, and a positive association between hypoxia levels

and the severity of gastric mucosal injury in mice with PHT was

also observed. The oxygen concentration directly influences

mitochondrial function, and mitochondria perform critical metabolic

and signalling functions in nearly all eukaryotic cells (21). As oxygen-sensing organelles,

mitochondria exhibit functional impairment and structural damage in

response to hypoxia, accompanied by elevated oxidative stress

(12,22). Our previous data demonstrated that

mitochondrial dysfunction is involved in mucosal epithelial injury

and the progression of benign and malignant gastric mucosal lesions

under hypoxic conditions (14). In

the present study, microarray analysis was performed on biopsied

gastric mucosal tissues. Microarray analysis revealed that compared

with healthy controls, patients with PHG exhibited increased

activation of multiple mitochondrial pathways related to structural

integrity and respiratory function. During mitochondrial ATP

synthesis, the electron transport chain generates ROS as metabolic

byproducts. Consequently, mitochondria represent the primary

endogenous source of cellular ROS, which can serve as key mediators

of oxidative stress, inflammation, and tissue damage (5,14). TEM

imaging confirmed that ultrastructural mitochondrial abnormalities,

including reduced mitochondrial size and decreased mitochondrial

cristae, were observed in the PHG mucosa. Moreover, 4-HNE

expression was significantly elevated in PHG tissues, accompanied

by increased MitoSox signalling in primary gastric epithelial cells

isolated from PHG sections. A PHT mouse model and a hypoxia-induced

GES-1 cell model were also established, and it was verified that a

significant alteration in mitochondrial structure associated with

increased mitochondrial oxidative stress and ROS levels (as assayed

by MitoSox staining, ROS detection, 4-HNE expression and mt 8-OHdG

concentration) was observed in both the gastric mucosal epithelial

cells of mice with PHT and the hypoxia-treated GES-1 cells. The

progressive accumulation of mitochondrial ROS induces oxidative

damage to cellular macromolecules, including DNA, proteins, and

lipids. These ROS-mediated modifications can trigger diverse

pathological cascades, with the magnitude and nature of their

effects being modulated by microenvironmental conditions (23). Therefore, antioxidants may have

specific therapeutic effects under various conditions to alleviate

disease progression. Mito-TEMPO, a mitochondrion-targeted ROS

scavenger, exhibits potent antioxidant activity because it

selectively accumulates within mitochondria at concentrations

several-fold higher than those in the cytosol. This compound

attenuates mitochondrial oxidative stress by suppressing superoxide

generation, thereby restoring mitophagy and counteracting excessive

mitochondrial fission (22,24,25).

In a PHT mouse model and an in vitro cell model, it was

demonstrated that Mito-TEMPO administration attenuated gastric

mucosal injury in mice with PHT and hypoxia-induced GES-1 cell

damage, suggesting that mitochondrial oxidative stress-derived ROS

resulted in gastric mucosal injury and cell damage following

hypoxia. Our aforementioned findings indicate that mitochondrial

structural derangements and oxidative stress escalation in the

gastric mucosa drive PHG pathogenesis.

Mitochondria serve as critical hubs for numerous

essential cellular processes, such as amino acid and fatty acid

metabolism, the citric acid cycle, nitrogen metabolism, and

oxidative phosphorylation, which generate the majority of cellular

ATP. Glycolysis represents a fundamental metabolic pathway mediated

by multiple glycolytic enzymes in mammalian cells. Emerging

evidence indicates that gastric mucosal disorders upregulate

glycolytic flux under hypoxic conditions to sustain cellular energy

homeostasis (26,27). Our microarray and metabolic pathway

analyses demonstrated significant activation of glycolysis in the

gastric mucosa of patients with PHG, with LDHA serving as the

critical rate-limiting regulator of this process. LDHA, a key

enzyme in glycolysis that is upregulated in various

gastrointestinal diseases, converts pyruvate to lactic acid and

produces nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (28). Consistent with these findings, the

protein expression of LDHA was also increased in gastric mucosal

tissue samples from clinical PHG specimens, mouse PHT models and

hypoxia-induced GES-1 cells, suggesting that mitochondrial

oxidative stress drives LDHA-mediated glycolytic adaptation to

bioenergetic stress under hypoxia in PHG. Various studies have

suggested that in hypoxic tumour microenvironments, cancer cells

undergo metabolic reprogramming to preferentially utilize

glycolysis for ATP generation, enabling sustained proliferation

under oxygen-deprived conditions. This glycolytic shift not only

promotes tumour cell survival but also facilitates rapid biomass

accumulation, thereby driving aggressive tumour progression

(29). On the basis of our current

data, it is suggested that increased LDHA-mediated glycolysis in

the PHG, a representative disease of benign gastric lesions,

aggravates mucosal injury and cell damage rather than inducing cell

survival. Our previous study confirmed that HIF-1α can upregulate

the expression level of LDHA, increase glycolytic metabolism, and

increase mitochondrial oxidative stress, thereby participating in

the occurrence and development of PHG (14). Multiple studies have shown that

influenza A virus (WSN strain) impairs mitochondria, which then

generates ROS, thereby stabilizing HIF-1α and activating glycolysis

to provide energy for viral replication. Rabies virus

glycoprotein-engineered extracellular vesicles (deliver miR-137 and

downregulate HIF-1α by targeting Toll-like receptor 4 to inhibit

the NF-κB pathway, thereby improving glycolytic abnormalities and

neuroinflammation in autism model mice. Under glutamine

deprivation, extracellular cyclophilin B in glioblastoma binds to

CD147 to activate p-AKT, which upregulates HIF-1α to increase

glycolysis and inhibit mitochondrial function. In acute

pancreatitis, increased activity of xanthine oxidase (XO) generates

ROS to activate HIF-1α, which promotes lactate accumulation via

LDHA and triggers NOD-like receptor protein 3 inflammatory

responses, while the inhibition of XO can alleviate pancreatic

necrosis (30-33).

These findings confirm that mitochondrial redox stress, which is

involved in various diseases, can regulate the protein level of

HIF-1α, thereby modulating the expression of related proteins such

as LDHA, mediating changes in glycolytic metabolism, and

participating in the occurrence and development of diseases. An

in-depth exploration of the specific molecular mechanisms was not

performed in the present study, and the definite association

between the upregulation of LDHA induced by energy metabolism

alterations and mitochondrial dysfunction-mediated ROS production

under hypoxia in the PHG warrants further investigation.

Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation and

glycolysis constitute the two primary energy-producing pathways in

mammalian cells under physiological conditions. While glycolysis

serves to meet cellular energy demands, its upregulation also plays

a pivotal role in generating metabolic intermediates required for

macromolecular biosynthesis, particularly in highly proliferative

cells such as malignant cells (34). Although aerobic glycolysis (the

Warburg effect) can increase ATP production to sustain energy

homeostasis and supplement the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle,

excessive glycolytic flux in the gastric mucosal epithelium of

patients with PHG can disrupt normal aerobic respiration. This

metabolic reprogramming ultimately results in diminished net ATP

yield despite increased glycolytic activity (14). As a glycolytic enzyme, LDHA promotes

the release of glycolysis and lactic acid, and excessive lactic

acid influences the immune microenvironment, intracellular

signalling, cellular function and homeostasis to promote cell

damage and even death (35,36). Furthermore, our metabolic profiling

of gastric mucosal epithelial cells from mice with PHT revealed

significant alterations in metabolic pathways, characterized by

increased organic acid metabolism and decreased carbohydrate

metabolism. Consistent with these findings, elevated LDHA

expression and concomitant increases in lactic acid concentrations

across multiple experimental systems, including clinical PHG

specimens, PHT mouse models, and hypoxia-exposed GES-1 cells, were

observed. These observations are particularly noteworthy given that

LDHA has emerged as a promising therapeutic target in oncology.

Several small-molecule LDHA inhibitors have been developed to

specifically block the lactate dehydrogenase activity of LDHA,

thereby suppressing glycolytic flux and inhibiting tumour

progression in various cancers (37). Notably, in the present study, it was

found that the LDHA inhibitor oxamic acid sodium not only

alleviated gastric mucosal damage in mice with PHT but also

restored morphological changes and increased relative cell

viability in GES-1 cells under hypoxic conditions. The present

study focused primarily on the role of LDHA in mitochondrial

oxidative stress in the PHG, but metabolic reprogramming affecting

mitochondrial function is complex, with other key glycolytic

enzymes, such as HK2 and PKM2, also regulating cellular redox

balance and mitochondrial stress. HK2 normally binds to the

voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) on the outer mitochondrial

membrane to maintain mitochondrial function, and under metabolic

disturbances, glucose-induced HK2 stabilization and subsequent

detachment from VDAC impair mitochondrial ATP disposal, cause

membrane hyperpolarization, and increase ROS levels (38). The tetrameric form of PKM2 supports

glycolytic flux and mitochondrial metabolism, whereas pathological

conditions induce its sulfenylation, disrupting tetramer formation,

reducing activity, and impairing mitochondrial biogenesis/fusion

effects, which are reversed by PKM2 activation (39). In our previous study, quantitative

protein detection of HK2 and PKM2 was conducted, and it was

revealed that the expression levels of HK2 and PKM2 were increased

in mouse models, which were involved in the occurrence and

development of PHG (14). Given

their roles in metabolic disorder-induced mitochondrial damage, HK2

and PKM2 may contribute to PHG pathogenesis, warranting further

investigation. In summary, the mechanisms underlying gastric

epithelial cell injury in the PHG warrant further investigation.

Specifically, the roles of hypoxia-induced alterations in energy

metabolism and mitochondrial dysfunction, particularly their

contribution to ROS production, remain to be fully elucidated.

The present study has several limitations. First,

the relationships between oxidative stress and various types of

programmed cell death (such as apoptosis, pyroptosis, and

ferroptosis) remain unclear. Second, the mechanism through which

LDHA affects epithelial cell death is not well defined, and future

studies need to focus on exploring more downstream mechanisms.

Third, the intervention experiments with Mito-TEMPO (for inhibiting

mitochondrial oxidative stress) and oxamic acid sodium (for

inhibiting LDHA) focus mainly on short-term effects. Although the

current experimental design included a 16-week drug administration

period, a more longer intervention study to assess their effects on

the progression of PHG has yet to be conducted. This is due to time

limitations and technical constraints in establishing a long-term

mouse PHG model in the current research, and the selectivity and

potential side effects of these agents under long-term use also

remain to be further clarified. Notably, for clinical application

of these two inhibitors, large-scale experimental verification is

still needed to investigate potential side effects and confirm

their clinical applicability.

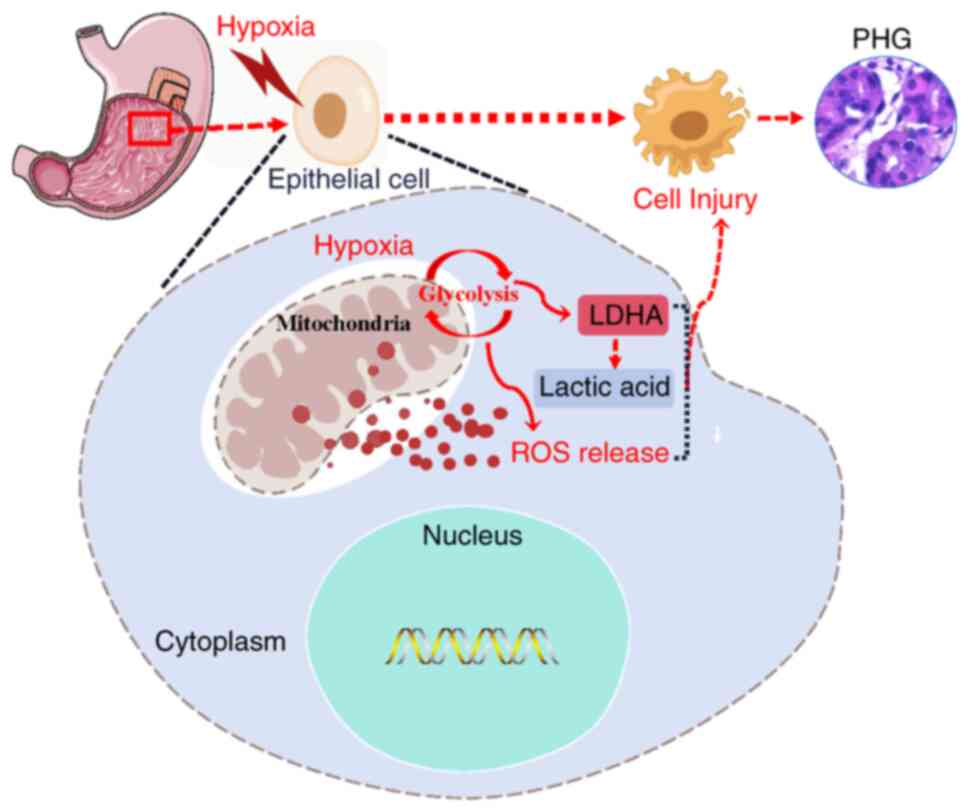

In summary, PHT leads to congestion and hypoxia in

the gastric mucosal epithelium, and this hypoxia induces

mitochondrial oxidative stress and ROS production, which are

associated with abnormal glycolytic metabolism and increased

LDHA-mediated lactic acid production. Ultimately, these changes

result in gastric mucosal epithelial injury to promote the

progression of PHG (Fig. 7).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee of South China Agricultural University (Guangzhou, P.R.

China) for providing mice breeding and experimental studies in this

experiment. We also thank the Institutional Animal Care and Use

Committee of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen

University (Guangzhou, P.R. China) for providing mouse experimental

studies and technical support in this experiment.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 82170569

and 82470589), and the Science and Technology Planning Projects of

Guangzhou City (grant no. 2025A03J3193).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author. Datasets from this study

are available in the public database Science Data Bank (ScienceDB)

at https://www.scidb.cn/detail?dataSetId=59ef752d1c60447a978aa3a62ad83c44.

Authors' contributions

JL performed the mouse experiments and analyzed the

data of the patients. KX contributed essential reagents and

conducted the cell experiments. XO planned and conducted primary

cell isolation and signalling pathway study. ST designed the whole

project, supervised the research and wrote the paper. JL and KX

confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read and

approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The study protocol was approved [approval no.

(2021)02-176] by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the

Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Guangzhou,

P.R. China). Written informed consent from the patients was waived.

All animal experimental studies were approved (approval no.

2022F122) by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of

South China Agricultural University (Guangzhou, P.R. China).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Cubillas R and Rockey DC: Portal

hypertensive gastropathy: A review. Liver Int. 30:1094–1102.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

McCormack TT, Sims J, Eyre-Brook I,

Kennedy H, Goepel J, Johnson AG and Triger DR: Gastric lesions in

portal hypertension: Inflammatory gastritis or congestive

gastropathy? Gut. 26:1226–1232. 1985.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Guixé-Muntet S, Quesada-Vázquez S and

Gracia-Sancho J: Pathophysiology and therapeutic options for

cirrhotic portal hypertension. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol.

9:646–663. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Urrunaga NH and Rockey DC: Portal

hypertensive gastropathy and colopathy. Clin Liver Dis. 18:389–406.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Tan SW: Molecular mechanism of portal

hypertensive gastropathy: An update. Clin Res Hepatol

Gastroenterol. 48(102423)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Luo Z, Tian M, Yang G, Tan QR, Chen YB, Li

G, Zhang QW, Li YK, Wan P and Wu JG: Hypoxia signaling in human

health and diseases: Implications and prospects for therapeutics.

Signal Transduct Target Ther. 7(218)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Yuan XY, Ruan W, Bobrow B, Carmeliet P and

Eltzschig HK: Targeting hypoxia-inducible factors: Therapeutic

opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 23:175–200.

2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Lee P, Chandel NS and Simon MC: Cellular

adaptation to hypoxia through hypoxia inducible factors and beyond.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 21:268–283. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Brooks GA: Lactate as a fulcrum of

metabolism. Redox Biol. 35(101454)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Sies H: Oxidative stress: A concept in

redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 4:180–183. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kierans SJ and Taylor CT: Glycolysis: A

multifaceted metabolic pathway and signaling hub. J Biol Chem.

300(107906)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Xiao YL, Zhang YW, Xie KD, Huang XL, Liu

XZ, Luo JJ and Tan SW: Mitochondrial dysfunction by FADDosome

promotes gastric mucosal injury in portal hypertensive gastropathy.

Int J Biol Sci. 20:2658–2685. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tan S, Chen X, Xu M, Huang X, Liu H, Jiang

J, Lu Y, Peng X and Wu B: PGE2/EP4 receptor attenuated mucosal

injury via β-arrestin1/Src/EGFR-mediated proliferation in portal

hypertensive gastropathy. Br J Pharmacol. 174:848–866.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Xiao YL, Liu XZ, Xie KD, Luo JJ, Zhang YW,

Huang XL, Luo JN and Tan SW: Mitochondrial dysfunction induced by

HIF-1α under hypoxia contributes to the development of gastric

mucosal lesions. Clin Transl Med. 14(e1653)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Tan S, Li L, Chen T, Chen X, Tao L, Lin X,

Tao J, Huang X, Jiang J, Liu H and Wu B: β-Arrestin-1 protects

against endoplasmic reticulum stress/p53-upregulated modulator of

apoptosis-mediated apoptosis via repressing p-p65/inducible nitric

oxide synthase in portal hypertensive gastropathy. Free Radic Biol

Med. 87:69–83. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Gana JC, Cifuentes LI, Gattini D,

Villarroel Del Pino LA, Peña A and Torres-Robles R: Band ligation

versus beta-blockers for primary prophylaxis of oesophageal

variceal bleeding in children with chronic liver disease or portal

vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

9(CD010546)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Noto JM, Piazuelo MB, Romero-Gallo J,

Delgado AG, Suarez G, Akritidou K, Girod Hoffman M, Roa JC, Taylor

CT and Peek RM Jr: Targeting hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha

suppresses Helicobacter pylori-induced gastric injury via

attenuation of both cag-mediated microbial virulence and

proinflammatory host responses. Gut Microbes.

15(2263936)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Lin ZH, Song JL, Gao YK, Huang SH, Dou RZ,

Zhong PY, Huang GQ, Han L, Zheng JS, Zhang XY, et al:

Hypoxia-induced HIF-1α/lncRNA-PMAN inhibits ferroptosis by

promoting the cytoplasmic translocation of ELAVL1 in peritoneal

dissemination from gastric cancer. Redox Biol.

52(102312)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

He C, Wang LB, Zhang JT and Xu H:

Hypoxia-inducible microRNA-224 promotes the cell growth, migration

and invasion by directly targeting RASSF8 in gastric cancer. Mol

Cancer. 16(35)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Zhang YF, Lu HW, Ji H and Li YM: p53

upregulated by HIF-1α promotes gastric mucosal epithelial cells

apoptosis in portal hypertensive gastropathy. Dig Liver Dis.

55:81–92. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Winter JM, Yadav T and Rutter J: Stressed

to death: Mitochondrial stress responses connect respiration and

apoptosis in cancer. Mol Cell. 82:3321–3332. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Fuhrmann DC and Brüne B: Mitochondrial

composition and function under the control of hypoxia. Redox Biol.

12:208–215. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Zhang BY, Pan CY, Feng C, Yan CQ, Yu YJ,

Chen ZL, Guo CJ and Wang XX: Role of mitochondrial reactive oxygen

species in homeostasis regulation. Redox Rep. 27:45–52.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yang SG, Bae JW, Park HJ and Koo DB:

Mito-TEMPO protects preimplantation porcine embryos against

mitochondrial fission-driven apoptosis through DRP1/PINK1-mediated

mitophagy. Life Sci. 315(121333)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Shetty S, Kumar R and Bharati S:

Mito-TEMPO, a mitochondria-targeted antioxidant, prevents

N-nitrosodiethylamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in mice. Free

Radic Biol Med. 136:76–86. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Liu X, Wang X, Zhang J, Lam EK, Shin VY,

Cheng AS, Yu J, Chan FK, Sung JJ and Jin HC: Warburg effect

revisited: An epigenetic link between glycolysis and gastric

carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 29:442–450. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cheng CT, Kuo CY, Ouyang C, Li CF, Chung

Y, Chan DC, Kung HJ and Ann DK: Metabolic Stress-induced

phosphorylation of KAP1 Ser473 blocks mitochondrial fusion in

breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 76:5006–5018. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Yi Y, Wu MY, Chen KT, Chen AH, Li LQ,

Xiong Q, Wang XR, Lei WB, Xiong GX and Fang SB: LDHA-mediated

glycolysis in stria vascularis endothelial cells regulates

macrophages function through CX3CL1-CX3CR1 pathway in noise-induced

oxidative stress. Cell Death Dis. 16(65)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Kooshan Z, Cárdenas-Piedra L, Clements J

and Batra J: Glycolysis, the sweet appetite of the tumor

microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 600(217156)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Zhang YJ, Chang LF, Xin X, Qiao YX, Qiao

WN, Ping JH, Xia J and Su J: Influenza A virus-induced glycolysis

facilitates virus replication by activating ROS/HIF-1α pathway.

Free Radic Biol Med. 250:910–924. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Qin Q, Li MY, Fan LL, Zeng X, Zheng DY,

Wang H, Jiang YT, Ma XR, Xing L, Wu LJ, et al: RVG engineered

extracellular vesicles-transmitted miR-137 improves autism by

modulating glucose metabolism and neuroinflammation. Mol

Psychiatry. 30:4072–4084. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Yin H, Liu Y, Dong Q, Wang HY, Yan YJ,

Wang XQ, Wan XQ, Yuan GQ and Pan YW: The mechanism of extracellular

Cyp B promotes glioblastoma adaptation to glutamine deprivation

microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 597(216862)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Rong J, Han CX, Huang Y, Wang YQ, Qiu Q,

Wang M, Wang SS, Wang R, Yang JQ, Li X, et al: Inhibition of

xanthine oxidase alleviated pancreatic necrosis via HIF-1

α-regulated LDHA and NLRP3 signaling pathway in acute pancreatitis.

Acta Pharm Sin B. 14:3591–3604. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Chelakkot C, Chelakkot VS, Shin Y and Song

K: Modulating glycolysis to improve cancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci.

24(2606)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

An S, Yao Y, Hu HB, Wu JJ, Li JX, Li LL,

Wu J, Sun MM, Deng ZY, Zhang YY, et al: PDHA1

hyperacetylation-mediated lactate overproduction promotes

sepsis-induced acute kidney injury via Fis1 lactylation. Cell Death

Dis. 14(457)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Rabinowitz JD and Enerbäck S: Lactate: The

ugly duckling of energy metabolism. Nat Metab. 2:566–571.

2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Liu J, Zhang C, Zhang TL, Chang CY, Wang

JM, Bazile L, Zhang LJ, Haffty BG, Hu WW and Feng ZH: Metabolic

enzyme LDHA activates Rac1 GTPase as a noncanonical mechanism to

promote cancer. Nat Metab. 4:1830–1846. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Rabbani N, Xue M and Thornalley PJ:

Hexokinase-2-linked glycolytic overload and unscheduled

Glycolysis-driver of insulin resistance and development of vascular

complications of diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 23(2165)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Qi W, Keenan HA, Li Q, Ishikado A, Kannt

A, Sadowski T, Yorek MA, Wu I, Lockhart S, Coppey LJ, et al:

Pyruvate kinase M2 activation may protect against the progression

of diabetic glomerular pathology and mitochondrial dysfunction. Nat

Med. 23:753–762. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|