Introduction

The global geriatric population is expanding

rapidly, with individuals aged ≥65 years projected to more than

double in the coming decades, reaching ~2.2 billion by the late

2070s (1). Thailand transitioned to

an aged society as the proportion of its population aged ≥60 years

reached approximately 20%, reflecting significant demographic aging

in recent years (2). Aging is

associated with multisystem decline, particularly in the

musculoskeletal system, which increases vulnerability to low-energy

fragility injuries. Among these, hip fractures are common and

represent a major public health concern due to their association

with disability, reduced quality of life, elevated mortality and

substantial healthcare costs (3,4). In

the United States, hospitalization costs for hip fractures exceed

$30 billion annually, while in Japan they reach ~$2.99 billion

(5,6). Across Asia, fragility fractures are

projected to nearly double by 2050, with direct costs increasing

from $9.5 billion in 2018 to $15 billion (7). In Thailand, hip fractures with

hospitalization costs increased 2.5-fold between 2013 and

2022(8). Globally, hip fracture

incidence is estimated at 182 cases per 100,000 individuals (95%

uncertainty interval, 142-231) (9).

In Thailand, the incidence of hip fractures increased annually from

2013 to 2019 before stabilizing between 2019 and 2022, with the

age-standardized incidence rate rising from 116.3 cases per 100,000

individuals in 2013 to 145.1 cases in 2019, with a slight decline

to 140.7 cases in 2022(8).

Within the Thai context, fragility or osteoporotic

fractures are defined as hip fractures resulting from low-energy

traumatic mechanisms in individuals aged ≥50 years (10). Surgical intervention remains the

standard treatment, aiming to reduce mortality and prevent

long-term disability. However, postoperative functional and

ambulatory recovery is often suboptimal and varies considerably

across studies (11-13).

Previous reports have indicated that 40-60% of patients regain

pre-fracture mobility and instrumental activities of daily living

(ADLs) within 3 to 6 months post-surgery (13,14),

while more recent evidence has suggested that at 3 months, only 20%

achieve satisfactory ambulation and 21.5% regain pre-injury walking

ability (15). Nearly 30% fail to

recover ADLs within 1 year (16),

and registry data from Japan show that ~10% of previously

ambulatory patients remain unable to walk at 4 months (17). Furthermore, a systematic review

concluded that despite advances in anesthesia, perioperative care

and rehabilitation, the 1-year mortality rate remains substantial,

with a mean of 22% (range, 2.4-34.8%) and marked variation across

populations (18). Ambulatory

ability is an essential functional capacity in older adults,

enabling them to carry out basic ADLs and maintain social

participation through community ambulation (19). Therefore, early rehabilitation

training after hip fracture surgery, encompassing mobility,

transfer and ambulation training, is crucial for preventing

complications from prolonged bed rest and enabling patients to

regain mobility and independent ambulation (20-22).

Recovery of ambulatory capacity after hip fracture

surgery depends on multiple factors, including preoperative,

intraoperative and postoperative conditions (23). While several studies have examined

preoperative and perioperative predictors (24-26),

relatively few have focused on postoperative prognostic factors

(27,28). Postoperative complications play a

crucial role in determining functional outcomes after hip fracture

surgery. Prolonged Intensive Care Unit (ICU) stays, and the need

for ventilator support have been associated with increased

long-term morbidity and increased mortality rates (23,29).

Tangchitphisut et al (23)

reported that postoperative ICU admission or ventilator use was

significantly more common among patients who were unable to bear

self-weight at discharge (10/55 patients, 18.2%; P<0.001).

Similarly, Eschbach et al (29) found that geriatric hip-fracture

patients requiring prolonged ICU care (>3 days) had markedly

higher in-hospital, 6-month and 12-month mortality rates compared

with those with shorter ICU stays (P=0.001). Furthermore,

postoperative complications such as infections (particularly

pressure ulcers), delirium, arrhythmias and respiratory issues have

been linked to poorer functional and mobility outcomes (13,23,30).

Recent evidence has also identified postoperative medical

complications as the most significant risk factor for persistent

walking disability (23,24,27).

Although hip fractures profoundly affect both short and long-term

outcomes, evidence regarding prognostic factors for ambulation

during the early subacute period remains limited. Early

identification of patients at high risk for impaired ambulation is

essential to guide postoperative management, optimize

rehabilitation and support caregiver planning. The 6-week timeframe

represents a clinically relevant milestone, coinciding with routine

follow-up, facilitating timely rehabilitation and enabling

recognition of patients at risk of delayed recovery before

longer-term outcomes are established. To address this gap, the

present study aimed to identify postoperative prognostic factors

associated with the inability to ambulate 6 weeks after fragility

hip fracture surgery.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

This retrospective cohort study was conducted at a

tertiary care referral center, Hatyai Hospital (Songkhla,

Thailand). Data were obtained from electronic medical records

(EMRs) of patients treated between October 1, 2018, and September

30, 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Age ≥50 years;

ii) diagnosis of a single, closed hip fracture resulting from

low-energy trauma; iii) a fracture classified as a femoral neck,

intertrochanteric or subtrochanteric fracture, identified by

specific International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 codes

(31) (S72.000-S72.019,

S72.100-S72.101, S72.110-S72.111 and S72.200-S72.210); and iv)

surgical treatment for a hip fracture, identified using

ICD-9(32) procedure codes (79.15,

79.25, 79.35, 81.51, and 81.52). The exclusion criteria were as

follows: i) Hip fractures secondary to pathological conditions (for

example. malignancy); ii) multiple traumatic injuries sustained

during the same admission; iii) fractures caused by high-energy

trauma; iv) periprosthetic fractures or fractures involving

previous nail fixation; v) conservative (non-surgical) management;

vi) pre-fracture bedridden status or wheelchair dependence; vii)

in-hospital mortality before discharge; and viii) incomplete or

missing EMR data during the study period. The study was approved by

the Human Research Ethics Committee of Hatyai Hospital (approval

no. HYH EC 007-67-01).

Surgical intervention was performed using procedures

appropriate for the specific type of hip fracture. Following

surgery, all patients underwent a standardized postoperative

rehabilitation program based on the recommendations of the American

Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (21) and the National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (22). The

program was designed to promote functional recovery and ambulation,

with individual modifications made according to patient centered

care principles that considered physical status, comorbidities,

surgical procedure and overall tolerance. The rehabilitation

protocol for ambulatory training emphasized early mobilization and

included bed mobility exercises, transitions from supine to

sitting, sitting balance activities, sit to stand transfers, safe

pivot transfers from bed to chair or wheelchair and standing

balance training. Once the patient demonstrated adequate stability,

ambulation training with walking practice was introduced. Patients

were encouraged to ambulate with a walker and to practice partial

weight bearing on the surgical limb as tolerated. Each training

session was conducted once daily for ~20 to 30 min. Routine

follow-up evaluations were performed at 6 weeks postsurgery to

monitor recovery, assess ambulatory status, and address ongoing

complications and care needs.

Data collection

A retrospective review was conducted using the EMRs

of 432 patients who underwent hip fracture surgery. Data collected

included admission dates, clinical characteristics and

postoperative variables considered potential prognostic factors for

the inability to walk 6 weeks after surgery. Candidate

postoperative predictors included: i) Postoperative ICU admission

or ventilator use (23,29), which was defined to include either

ICU admission regardless of ventilator support or endotracheal

intubation with mechanical ventilation, in the ICU or elsewhere;

ii) need for postoperative oxygen support (33,34),

referred to any supplemental oxygen via nasal cannula, face mask or

high-flow oxygen, administered to prevent hypoxemia and maintain a

peripheral oxygen saturation level generally ≥95% (unless

contraindicated); iii) urinary catheter use on the second

postoperative day (23,35); iv) the presence of postoperative

surgical complications (33,36),

such as postoperative weight-bearing restrictions due to poor bone

quality or revision surgery following fixation failure; v) anemia

from postoperative blood loss (37); vi) the presence of postoperative

medical complications (33,38) (such as pressure ulcers, urinary

tract infection and pneumonia); vii) time to initiation of

functional training (39-41)

(<48, 48-72 and >72 h post-operation); viii) the ability to

walk at hospital discharge; ix) the length of stay (LOS) (42); and x) the presence of overall

complications within 6 weeks after discharge (23,27,33),

classified as surgical, medical or mental-health related. The

primary endpoint was ambulatory status 6 weeks after surgery.

Patients were classified into two groups based on discharge

ambulation: i) a non-ambulatory group, consisting of patients who

were bedridden or wheelchair-dependent; and ii) an ambulatory

group, consisting of patients who could walk independently or with

the aid of a walking device.

Sample size calculation

The determination of an appropriate sample size for

logistic regression typically necessitates a minimum of 5 to 10

events per candidate predictor parameter to ensure model

reliability. Given that the present study included 14 exploratory

variables (10 postoperative factors and 4 demographic factors to

adjust the model), the corresponding requirement ranged from 90 to

140 events (43,44). Considering that the prevalence of

inability to walk in this study was 24.8%, a total sample size

between 364 and 565 participants was deemed optimal.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Stata

Statistical Package (version 18.0; Stata Corp LLC). Categorical

variables are presented as frequencies and percentages, while

continuous variables are reported as means and standard deviations

for normally distributed data or medians and interquartile ranges

for skewed data. To compare proportions between the two groups

(i.e., inability or ability to walk 6 weeks after fragility hip

fracture surgery), the χ2 test was used. When the

expected cell count was less than five, Fisher's exact test was

applied. Continuous variables were compared using Student's t-test

for parametric data or a Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric

data, depending on the distribution. Variables with clinical

relevance and those with P<0.25 (45-47)

in an initial screening were included in the univariable analysis,

with results presented as univariable risk ratios. To identify

factors associated with the inability to walk 6 weeks after

fragility hip fracture surgery, a multivariable Poisson regression

model was fitted with a log link and robust standard errors

(48). The model was adjusted for

age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (49) and fracture type. The binary outcome

was the ability/inability to walk at 6 weeks, and multivariable

risk ratios (mRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were

estimated. Two-sided P<0.05 was considered statistically

significant. Multicollinearity among covariates was assessed using

variance inflation factors (VIF), with a VIF value of <5

considered acceptable (50). During

variable selection, it was found that ambulatory training and the

inability to walk at discharge were collinear, and a significant

association was observed between the two variables. As they are

also theoretically expected to be correlated, a pragmatic approach

was used to determine which variable contributed more effectively

to the multivariable model (51).

Inability to walk at discharge yielded a higher adjusted R-squared

value and was therefore retained in the final model. All other

postoperative predictors included in the analysis had VIF values

<5.

Results

Study population and exclusions

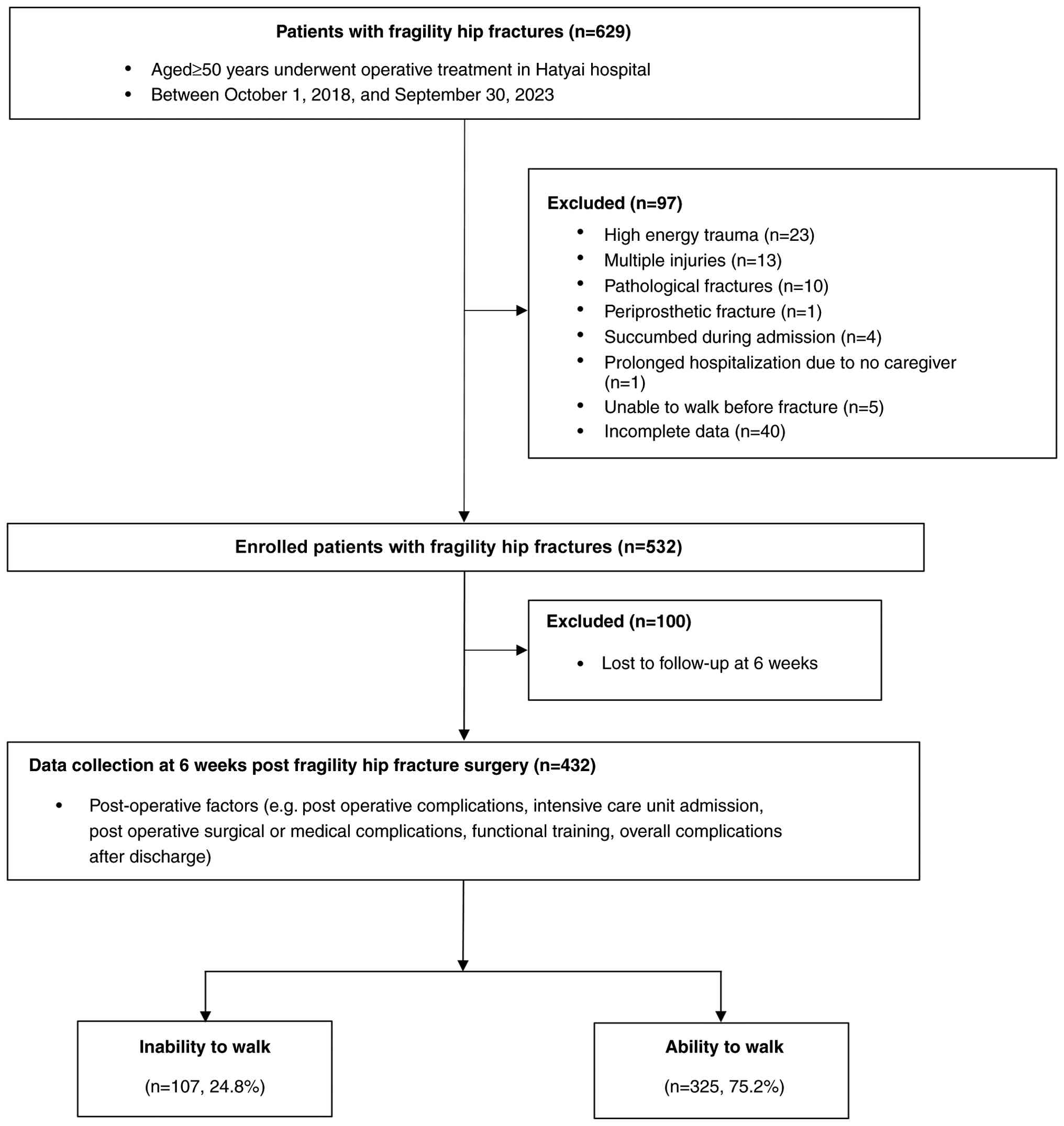

A total of 629 patients with fragility hip fractures

underwent surgery. Of these, 97 patients were excluded for the

following reasons: 23 experienced high-energy trauma, 13 sustained

multiple injuries, 10 had pathological fractures, 1 had a

periprosthetic fracture, 4 died during admission, 1 required

prolonged hospitalization due to the absence of a caregiver, 5 were

unable to walk prior to the fracture and 40 had incomplete data

collection. Consequently, 532 patients were left for the present

analysis. However, 100 patients were lost to follow-up at 6 weeks

postoperatively, resulting in a final study population of 432

patients. There were no statistically significant differences in

baseline characteristics [age, sex, CCI, preoperative hematocrit

(Hct) and fracture type] between patients who completed follow-up

and those who were lost to follow-up (Table SI). The majority of included

participants were female (313 patients, 72.5%) and overall age was

76.8±9.6 years (range, 52-100 years).

Comparative analysis of ambulatory and

non-ambulatory patient groups at 6 weeks postoperatively

At 6 weeks postsurgery, 325 patients (75.2%)

regained the ability to walk, while 107 patients (24.8%) remained

non-ambulatory (Fig. 1). No

statistically significant differences were observed between groups

regarding BMI, smoking status, and glomerular filtration rate.

However, Hct levels were significantly lower in the non-ambulatory

group (31.3 vs. 33.4%; P<0.001). When comparing the two groups,

the inability-to-walk group showed a significantly higher

proportion of female patients (81.3 vs. 69.5%; P=0.018), higher

mean age (79.3±9.6 vs. 76.0±9.4 years; P=0.001) and a lower

proportion of pre-fracture independent community ambulation (35.5

vs. 71.7%; P<0.001). Additionally, this group exhibited a

significantly higher prevalence of underlying diseases (92.5 vs.

82.8%; P=0.014), including diabetes mellitus, cerebrovascular

disease, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease or dementia,

heart disease and musculoskeletal disorders. Furthermore,

significant differences were found between the non-ambulatory and

ambulatory group in the proportion of patients who sustained indoor

falls (88.8 vs. 79.4%; P=0.049) and the distribution of fracture

types (P=0.002) (Table I).

| Table IComparison of patients' demographic

and clinical characteristics between groups with the inability and

ability to walk at 6 weeks after fragility hip fracture surgery

(n=432). |

Table I

Comparison of patients' demographic

and clinical characteristics between groups with the inability and

ability to walk at 6 weeks after fragility hip fracture surgery

(n=432).

| Variables | Inability to walk

(n=107) | Ability to walk

(n=325) | P-value |

|---|

| Female, n (%) | 87 (81.3) | 226 (69.5) | 0.018 |

| Age,

yearsa | 79.3±9.6 | 76.0±9.4 | 0.002 |

| Body mass index,

kg/m2a | 22.3±4.5 | 22.5±4.1 | 0.577 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 7 (6.5) | 37 (11.4) | 0.711 |

| Pre fracture

community walking independent, n (%) | 38 (35.5) | 233 (71.7) | <0.001 |

| Underlying

diseases, n (%) | 99 (92.5) | 269 (82.8) | 0.014 |

|

Hypertension | 82 (76.6) | 217 (66.8) | 0.055 |

|

Diabetes

mellitus | 40 (37.4) | 88 (27.1) | 0.043 |

|

Dyslipidemia | 51 (47.7) | 125 (38.5) | 0.093 |

|

Cerebrovascular

disease | 33 (30.8) | 43 (13.2) | <0.001 |

|

Parkinson's

disease | 6 (5.6) | 5 (1.5) | 0.020 |

|

Alzheimer's/dementia | 12 (11.2) | 15 (4.6) | 0.014 |

|

Heart

disease (AF/VHD/IHD) | 16 (15.0) | 23 (7.1) | 0.014 |

|

Pulmonary

disease | 6 (5.6) | 40 (12.3) | 0.051 |

|

Anemia | 15 (14.0) | 36 (11.1) | 0.413 |

|

Musculoskeletal

problems | 19 (17.8) | 34 (10.5) | 0.046 |

| Charlson

Comorbidity Indexa | 5.0±1.7 | 4.1±1.5 | <0.001 |

| Falling indoors, n

(%) | 95 (88.8) | 258 (79.4) | 0.049 |

| Fracture types, n

(%) | | | 0.002 |

|

Subtrochanteric

fracture of the femur | 3 (2.8) | 5 (1.5) | |

|

Intertrochanteric

fracture of the femur | 69 (64.5) | 152 (46.8) | |

|

Femoral neck

fracture | 35 (32.7) | 168 (51.7) | |

| Preoperative

hematocrit, %a | 31.3±5.0 | 33.4±5.2 | <0.001 |

| Glomerular

filtration rate, ml/mina | 74.0±26.5 | 81.0±48.8 | 0.166 |

Postoperative factors associated with

ambulatory status

Regarding postoperative factors, patients in the

non-ambulatory group at 6 weeks after fragility hip fracture

surgery exhibited a significantly higher need for postoperative

oxygen support (59.8 vs. 40.6%; P=0.001), urinary catheter use on

the second postoperative day (62.6 vs. 50.5%; P=0.029), presence of

postoperative surgical complications (11.2 vs. 1.8%; P<0.001)

and presence of postoperative medical complications (39.2 vs.

22.5%; P=0.001). Additionally, LOS (≥14 days) was more prevalent

among patients who remained unable to walk (35.5 vs. 15.4%;

P<0.001), as was the occurrence of postoperative complications

within 6 weeks after discharge (16.8 vs. 3.1%; P<0.001).

Conversely, the attainment of ambulation training was significantly

higher in the group that regained walking ability compared with

that in the non-ambulatory group (86.1 vs. 28.4%; P<0.001)

(Table II).

| Table IIComparison of patients'

post-operative factors between groups with the inability and

ability to walk at 6 weeks after fragility hip fracture

surgery. |

Table II

Comparison of patients'

post-operative factors between groups with the inability and

ability to walk at 6 weeks after fragility hip fracture

surgery.

| Variables | Inability to walk

(n=107) | Ability to walk

(n=325) | P-value |

|---|

| Postoperative ICU

admission or ventilator use, n (%) | 7 (6.5) | 9 (2.8) | 0.082 |

| Postoperative need

for oxygen support, n (%) | 64 (59.8) | 132 (40.6) | 0.001 |

| Urinary catheter

used in the second day post operative, n (%) | 67 (62.6) | 164 (50.5) | 0.029 |

| Presence of post

operative surgical complications, n (%) | 12 (11.2) | 6 (1.8) | <0.001 |

| Anemia due to post

operative blood loss, n (%) | 45 (42.1) | 107 (32.9) | 0.086 |

| Presence of the

post operative medical complications, n (%) | 42 (39.3) | 73 (22.5) | 0.001 |

| Time to start

functional training, n (%) | | | 0.056 |

|

<24 h

post-operation | 43 (40.2) | 168 (51.7) | |

|

24-48 h

post-operation | 32 (29.9) | 92 (28.3) | |

|

>72 h

post-operation | 30 (29.9) | 65 (20.0) | |

| Type of functional

training, n (%) | | | |

|

Mobility

training | 106 (99.1) | 327 (100.0) | 0.081 |

|

Transfer

training | 107 (100.0) | 323 (99.4) | 0.416 |

|

Ambulation

training | 30 (28.0) | 280 (86.2) | <0.001 |

| Inability to walk

at discharge, n (%) | 102 (95.3) | 72 (22.2) | <0.001 |

| Length of stay ≥14

days, n (%) | 38 (35.5) | 50 (15.4) | <0.001 |

| Presence of the

overall complications within 6 weeks after discharge, n (%) | 18 (16.8) | 10 (3.1) | <0.001 |

Regression analysis results

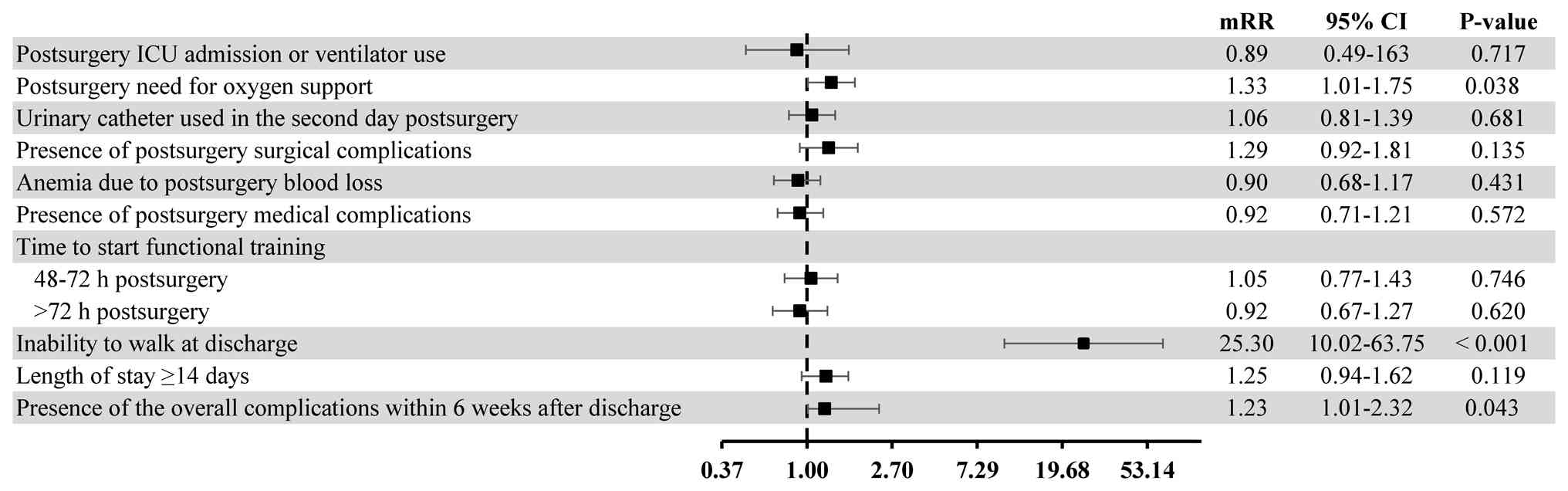

The results of univariable and multivariable

regression analyses are presented in Table III. In the univariate analysis,

several factors emerged as significant predictors, including

postoperative ICU admission or ventilator use, the need for

postoperative oxygen support, urinary catheter use on the second

postoperative day, the presence of postoperative surgical

complications, the presence of postoperative medical complications,

time to start functional training (>72 h post-operation),

inability to walk at hospital discharge, LOS (≥14 days), and the

occurrence of overall complications within 6 weeks post-discharge.

However, the multivariable regression analysis identified only the

following key prognostic factors: Inability to walk at discharge

(mRR, 25.3; 95% CI, 10.0-63.8; P<0.001), postsurgery need for

oxygen support (mRR, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.01-1.75; P=0.038) and the

presence of overall postsurgery complications within 6 weeks after

discharge (mRR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.01-2.32; P=0.043) (Fig. 2).

| Table IIIuRR and mRR of post-operative

prognostic factors of patients with the inability to walk at 6

weeks after fragility hip fracture surgery. |

Table III

uRR and mRR of post-operative

prognostic factors of patients with the inability to walk at 6

weeks after fragility hip fracture surgery.

| | Univariable

analysis | Multivariable

analysis |

|---|

| Variables | uRR | 95% CI | P-value | mRR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|

| Postoperative ICU

admission or ventilator use | 1.82 | 1.02-3.25 | 0.043 | 0.89 | 0.49-1.63 | 0.717 |

| Postoperative need

for oxygen support | 1.79 | 1.28-2.51 | 0.001 | 1.33 | 1.01-1.75 | 0.038 |

| Urinary catheter

used in the second day post operative | 1.46 | 1.03-2.05 | 0.031 | 1.06 | 0.81-1.39 | 0.681 |

| Presence of post

operative surgical complications | 2.9 | 2.00-4.21 | <0.001 | 1.29 | 0.92-1.81 | 0.135 |

| Anemia due to post

operative blood loss | 1.34 | 0.96-1.85 | 0.084 | 0.90 | 0.68-1.17 | 0.431 |

| Presence of the

post operative medical complications | 1.78 | 1.29-2.46 | <0.001 | 0.92 | 0.71-1.21 | 0.572 |

| Time to start

functional training | | | | | | |

|

<48 h

post-operation | | Reference | | | Reference | |

|

48-72 h

post-operation | 1.27 | 0.84-1.89 | 0.248 | 1.05 | 0.77-1.43 | 0.746 |

|

>72 h

post-operation | 1.62 | 1.10-2.39 | 0.015 | 0.92 | 0.67-1.27 | 0.620 |

| Inability to walk

at discharge | 30.2 | 12.58-72.7 | <0.001 | 25.3 | 10.02-63.75 | <0.001 |

| Length of stay ≥14

days | 2.15 | 1.56-2.96 | <0.001 | 1.25 | 0.94-1.65 | 0.119 |

| Presence of the

overall complications within 6 weeks after discharge | 2.82 | 2.02-3.92 | <0.001 | 1.23 | 1.01-2.32 | 0.043 |

Discussion

Hip fractures rank among the most serious fractures

in elderly individuals, often leading to impaired function, and

increased morbidity and mortality rates (13,52).

Elderly patients undergoing hip fracture surgery frequently exhibit

physical instability in the acute postoperative phase, which may

delay the initiation of rehabilitation (53,54).

Previous research has demonstrated that by 6 weeks postsurgery,

patients typically exhibit improved physical stability, enabling

participation in rehabilitation programs; however, vigilant

monitoring for potential complications remains imperative (27,55).

The present study aimed to identify prognostic factors associated

with the inability to walk at 6 weeks following fragility hip

fracture surgery. The findings emphasize the inability to walk at

discharge, the postoperative need for oxygen support and the

presence of postoperative complications within 6 weeks as

significant predictors of ambulatory outcomes.

The presence of overall complications after

discharge within 6 weeks increased the risk of the inability to

walk at 6 weeks post-fragility hip fracture surgery by 1.23 times

(95% CI, 1.01-2.32; P=0.043). Similarly, Chanthanapodi et al

(27) reported that postoperative

medical complications within the first 6 weeks were the strongest

prognostic factor for the inability to walk 6 weeks after surgery,

with a risk ratio (RR) of 2.04 (95% CI, 1.37-3.02; P<0.001).

However, the findings of the present study contrast with those in

the study by Monkuntod et al (56), which was a prospective observational

cohort study on older adults diagnosed with hip fractures,

scheduled for surgery and followed up for 2 weeks postoperatively

at three tertiary care hospitals. The study found that adverse

health outcomes during and after hospitalization did not predict

poor functional ability at discharge. This discrepancy may be

attributed to the shorter duration of complication recording (2

weeks) compared with both the present study and the research

conducted by Chanthanapodi et al (27). Empirical evidence suggests that

early identification of postoperative complications during the

acute to subacute rehabilitation phase is crucial in facilitating

functional recovery (33,55,57).

Ambulatory ability is a key concern for both

patients and caregivers (58).

Since walking ability is a crucial indicator of functional

recovery, it remains a primary focus for patients undergoing

surgery for fragility hip fractures during the postoperative period

(59). Previous research has

demonstrated that patients with hip fractures who regain early

walking ability have significantly higher survival rates at both 1-

and 10-years post-surgery (60).

Adulkasem et al (61)

reported that both pre-injury ambulatory status [odds ratio (OR),

52.72; 95% CI, 5.19-535.77] and ambulatory status at discharge (OR,

8.5; 95% CI, 3.33-21.70) were strong prognostic factors for

postoperative functional recovery, underscoring the importance of

baseline mobility. Similarly, the present study demonstrated a high

effect estimate for the inability to walk at discharge (mRR, 25.3;

95% CI, 10.02-63.75), although the wide confidence interval

observed may reflect the modest sample size and a potential risk of

model overfitting. The higher effect estimates in the present study

compared with those reported by Adulkasem et al (15,61)

are likely attributable to differences in study populations and

model specifications. While Adulkasem et al (15,61)

included patients across all baseline walking abilities, including

those who were non-ambulatory prior to hip fracture, the present

cohort was restricted to individuals who were ambulatory before the

fracture. Furthermore, the previous study analyses incorporated

both pre-fracture and discharge ambulatory status as predictors,

whereas the present model included only ambulatory ability at

discharge. Limiting the sample to pre-fracture ambulatory patients

and including a single post-fracture mobility variable may have

contributed to the more pronounced effect size observed.

The postoperative need for oxygen therapy was a

significant predictor of inability to walk at 6 weeks in the

present study. While chest physiotherapy and bed-mobility exercises

can be initiated with supplemental oxygen, achieving adequate

oxygenation on room air is an essential milestone before commencing

ambulation training in Hatyai Hospital. Dependence on oxygen

supplementation may therefore be associated with delayed

ambulation, a condition linked to an increased risk of medical

complications, higher mortality rate and prolonged hospital stay

(62,63). In line with this, the Clinical

Insights on Thailand Postoperative Hip Fracture Care (20) recommend early mobilization programs

for patients undergoing surgery for fragility hip fractures.

Although postoperative ICU admission or ventilatory

support were significant in the univariate analysis, they were not

significant in the multivariate model. This finding aligns with a

previous study that reported no significant increase in the risk of

an inability to self-bear weight at discharge among patients

admitted to the ICU postoperatively or requiring ventilatory

support. ICU admission and ventilatory support primarily address

acute postoperative complications that are often transient and

treatable with current medical interventions; therefore, they may

not serve as indicators of long-term functional recovery.

Additionally, these factors were associated with other stronger

predictors included in the model, such as overall postoperative

complications and ability to ambulate at discharge. After

adjustment for these variables, ICU/ventilator use and early

complications were no longer significant, suggesting that their

effects were largely accounted for by these stronger

predictors.

The presence of postoperative surgical

complications, the presence of postoperative medical complications,

urinary catheter usage on the second postoperative day and a LOS of

≥14 days were significant predictors in the univariate analysis but

not in the multivariate model in the present study. Previous

studies have reported conflicting findings regarding postoperative

complications. While several studies have reported an association

between postoperative surgical and medical complications and poorer

mobility outcomes (27,64,65),

the study by Tangchitphisut et al (23) found no such association. One study

identified urinary catheter use as a significant predictor

(35), whereas another reported no

association (23). Similarly,

although earlier studies reported LOS as a significant predictor

(25,66), subsequent research did not confirm

this association (67).

Importantly, while acute postoperative complications were not

independent predictors in the present multivariate analysis, late

complications occurring after discharge were significantly

associated with poorer walking ability. This observation supports

the hypothesis that early postoperative complications may reflect

transient conditions amenable to contemporary medical management,

whereas late complications may exert a more profound and lasting

impact on functional recovery.

Despite providing valuable insights, the present

study has several limitations that warrant consideration. The

single-center design may limit generalizability. Also, the final

analysis included 432 patients, of whom 107 were unable to walk.

With 14 variables, the events-per-variable (EPV) ratio was 7.6

(107/14), falling within the commonly accepted 5-10 range for

exploratory analyses (43,44). Nevertheless, a modestly low EPV may

increase the risk of model overfitting, potentially leading to

wider confidence intervals and inflated effect estimates for some

variables. Resource constraints such as bed shortages also

necessitated early discharges and patient transfers based on

healthcare coverage policies, potentially introducing referral bias

that influenced outcomes. In addition, the retrospective design

required excluding patients with incomplete data, which may have

reduced statistical power and could potentially lead to under- or

overestimation of prognostic factors. The outcome ‘inability to

walk’ provides a simple measure of functional recovery but may not

fully capture other aspects of postoperative function, such as

independence in ADLs or mobility scores. The present study was

designed to explore postoperative predictive factors rather than to

develop or validate a formal predictive model. Development of a

robust, clinically applicable model would require a larger sample

and further research. The factors identified here should therefore

be interpreted as potential predictors that may help clinicians

remain vigilant when caring for patients who present with these

characteristics. Finally, although multidisciplinary rehabilitation

teams play a critical role in postoperative care, early

identification of prognostic indicators for functional recovery

remains insufficiently understood. This highlights the need for

prospective, multicenter studies incorporating comprehensive

geriatric assessments and rehabilitation-specific variables and

outcomes to better identify patients who may benefit from

additional rehabilitation support.

In conclusion, the present study identified three

key prognostic factors for early functional recovery at 6 weeks

after fragility hip fracture surgery: The ability to ambulate at

hospital discharge, the postoperative need for oxygen support and

the presence of overall postoperative complications within 6 weeks.

Early rehabilitation and proactive management of medical

complications are critical strategies to enhance postoperative

mobility and improve long-term outcomes in this vulnerable patient

population.

Supplementary Material

Comparison of demographic and clinical

characteristics between patients who completed follow-up and those

who were lost to follow-up.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

TJ performed data collection and analysis, wrote the

original draft of the manuscript, and prepared all materials. PL

contributed to the data collection. JS performed data analysis and

coordination, as well as supervised and revised the manuscript. TJ,

PL and JS contributed to the conceptual and methodological design

of the study. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript. TJ and JS confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The protocol of this study was approved by the Human

Research Ethics Committee of Hatyai Hospital (Songkhla, Thailand;

approval no. HYH EC 007-67-01). All procedures involved in this

study followed the ethical standards of and complied with the

Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

United Nations Department of Economic and

Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects

2024: Summary of Results (UN DESA/POP/2024/TR/NO. 9), 2024.

https://population.un.org/wpp/assets/Files/WPP2024_Summary-of-Results.pdf.

|

|

2

|

Aung TNN, Moolphate S, Koyanagi Y,

Angkurawaranon C, Supakankunti S, Yuasa M and Aung MN: Determinants

of health-related quality of life among community-dwelling Thai

older adults in Chiang Mai, Northern Thailand. Risk Manag Healthc

Policy. 15:1761–1774. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Mattisson L, Bojan A and Enocson A:

Epidemiology, treatment and mortality of trochanteric and

subtrochanteric hip fractures: Data from the Swedish fracture

register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 19(369)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Amarilla-Donoso FJ, Lopez-Espuela F,

Roncero-Martin R, Leal-Hernandez O, Puerto-Parejo LM, Aliaga-Vera

I, Toribio-Felipe R and Lavado-García JM: Quality of life in

elderly people after a hip fracture: A prospective study. Health

Qual Life Outcomes. 18(71)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sarode AL, Su E, Drost J, Evan M, Haselton

L and Blecker N: The economic burden of hip fractures in the

geriatric population by mental health illness and substance use

status: National estimates 2016 to 2020. Injury.

56(112615)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Mori T, Komiyama J, Fujii T, Sanuki M,

Kume K, Kato G, Mori Y, Ueshima H, Matsui H, Tamiya N and Sugiyama

T: Medical expenditures for fragility hip fracture in Japan: A

study using the nationwide health insurance claims database. Arch

Osteoporos. 17(61)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Cheung CL, Ang SB, Chadha M, Chow ES,

Chung YS, Hew FL, Jaisamrarn U, Ng H, Takeuchi Y, Wu CH, et al: An

updated hip fracture projection in Asia: The Asian federation of

osteoporosis societies study. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 4:16–21.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Charatcharoenwitthaya N, Nimitphong H,

Wattanachanya L, Songpatanasilp T, Ongphiphadhanakul B,

Deerochanawong C and Karaketklang K: Epidemiology of hip fractures

in Thailand. Osteoporos Int. 35:1661–1668. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Dong Y, Zhang Y, Song K, Kang H, Ye D and

Li F: What was the epidemiology and global Burden of disease of hip

fractures from 1990 to 2019? results from and additional analysis

of the global Burden of disease study 2019. Clin Orthop Relat Res.

481:1209–1220. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Amphansap T and Sujarekul P: Quality of

life and factors that affect osteoporotic hip fracture patients in

Thailand. Osteoporos Sarcopenia. 4:140–144. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Sing CW, Lin TC, Bartholomew S, Bell JS,

Bennett C, Beyene K, Bosco-Lévy P, Chan AHY, Chandran M, Cheung CL,

et al: Global epidemiology of hip fractures: A study protocol using

a common analytical platform among multiple countries. BMJ Open.

11(e047258)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Wongtriratanachai P, Luevitoonvechkij S,

Songpatanasilp T, Sribunditkul S, Leerapun T, Phadungkiat S and

Rojanasthien S: Increasing incidence of hip fracture in Chiang Mai,

Thailand. J Clin Densitom. 16:347–352. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Dyer SM, Crotty M, Fairhall N, Magaziner

J, Beaupre LA, Cameron ID and Sherrington C: Fragility Fracture

Network (FFN) Rehabilitation Research Special Interest Group. A

critical review of the long-term disability outcomes following hip

fracture. BMC Geriatr. 16(158)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Vochteloo AJ, Moerman S, Tuinebreijer WE,

Maier AB, de Vries MR, Bloem RM, Nelissen RG and Pilot P: More than

half of hip fracture patients do not regain mobility in the first

postoperative year. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 13:334–341.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Adulkasem N, Chotiyarnwong P,

Vanitcharoenkul E and Unnanuntana A: Ambulation recovery prediction

after hip fracture surgery using the Hip fracture short-term

ambulation prediction tool. J Rehabil Med.

56(jrm40780)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Kitcharanant N, Atthakomol P, Khorana J,

Phinyo P and Unnanuntana A: Prognostic factors for functional

recovery at 1-year following fragility hip fractures. Clin Orthop

Surg. 16:7–15. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Hosoi T, Yakabe M, Matsumoto S, Fujimori

K, Tamaki J, Nakatoh S, Ishii S, Okimoto N, Kamiya K, Akishita M,

et al: Relationship between antidementia medication and fracture

prevention in patients with Alzheimer's dementia using a nationwide

health insurance claims database. Sci Rep. 13(6893)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Downey C, Kelly M and Quinlan JF: Changing

trends in the mortality rate at 1-year post hip fracture-a

systematic review. World J Orthop. 10:166–175. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Salpakoski A, Tormakangas T, Edgren J,

Sihvonen S, Pekkonen M, Heinonen A, Pesola M, Kallinen M, Rantanen

T and Sipilä S: Walking recovery after a hip fracture: A

prospective follow-up study among community-dwelling over 60-year

old men and women. Biomed Res Int. 2014(289549)2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Unnanuntana A, Kuptniratsaikul V,

Srinonprasert V, Charatcharoenwitthaya N, Kulachote N,

Papinwitchakul L, Wattanachanya L and Chotanaphuti T: A

multidisciplinary approach to post-operative fragility hip fracture

care in Thailand-a narrative review. Injury.

54(111039)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Postoperative rehabilitation of low energy hip fractures in older

adults: Appropriate use criteria. Re-issued by the American Academy

of Orthopaedic Surgeons Board of Directors 2023 September 9, 2025.

Available from: https://www.aaos.org/globalassets/quality-and-practice-resources/hip-fractures-in-the-elderly/hip-fx-rehab-auc_reapproval.pdf.

|

|

22

|

National Institute for Health and Care

Excellence (NICE). Hip fracture: management (update): Economic

model report for total hip replacement versus hemiarthroplasty.

NICE guideline CG124.2023 September 9, 2025]. Available from:

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg124/evidence/economic-model-report-pdf-11317540285.

|

|

23

|

Tangchitphisut P, Khorana J, Phinyo P,

Patumanond J, Rojanasthien S and Apivatthakakul T: Prognostic

factors of the inability to bear self-weight at discharge in

patients with fragility femoral neck fracture: A 5-year

retrospective cohort study in Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public

Health. 19(3992)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Kitcharanant N, Atthakomol P, Khorana J,

Phinyo P and Unnanuntana A: Predictive model of recovery to

prefracture activities-of-daily-living status one year after

fragility hip fracture. Medicina (Kaunas). 60(615)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Ko Y: Pre- and perioperative risk factors

of post hip fracture surgery walking failure in the elderly.

Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil. 10(2151459319853463)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Pajulammi HM, Pihlajamaki HK, Luukkaala TH

and Nuotio MS: Pre- and perioperative predictors of changes in

mobility and living arrangements after hip fracture-a

population-based study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 61:182–189.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Chanthanapodi P, Tammata N, Laoruengthana

A and Jarusriwanna A: Independent walking disability after

fragility hip fractures: A prognostic factors analysis. Geriatr

Orthop Surg Rehabil. 15(21514593241278963)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sheehan KJ, Guerrero EM, Tainter D, Dial

B, Milton-Cole R, Blair JA, Alexander J, Swamy P, Kuramoto L, Guy

P, et al: Prognostic factors of in-hospital complications after hip

fracture surgery: A scoping review. Osteoporos Int. 30:1339–1351.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Eschbach D, Bliemel C, Oberkircher L,

Aigner R, Hack J, Bockmann B, Ruchholtz S and Buecking B: One-year

outcome of geriatric hip-fracture patients following prolonged ICU

treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2016(8431213)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Cohn MR, Cong GT, Nwachukwu BU, Patt ML,

Desai P, Zambrana L and Lane JM: Factors associated with early

functional outcome after hip fracture surgery. Geriatr Orthop Surg

Rehabil. 7:3–8. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

World Health Organization. International

Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems.

10 edition. World Health Organization, Geneva, 2016.

|

|

32

|

World Health Organization. International

Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification

(ICD-9-CM). National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, MD,

2011.

|

|

33

|

Carpintero P, Caeiro JR, Carpintero R,

Morales A, Silva S and Mesa M: Complications of hip fractures: A

review. World J Orthop. 5:402–411. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Jo YY, Park CG, Lee JY, Kwon SK and Kwak

HJ: Prediction of early postoperative desaturation in extreme older

patients after spinal anesthesia for femur fracture surgery: A

retrospective analysis. Korean J Anesthesiol. 72:599–605.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Cecchi F, Pancani S, Antonioli D, Avila L,

Barilli M, Gambini M, Landucci Pellegrini L, Romano E, Sarti C,

Zingoni M, et al: Predictors of recovering ambulation after hip

fracture inpatient rehabilitation. BMC Geriatr.

18(201)2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Gonzalez de Villaumbrosia C, Barba R,

Ojeda-Thies C, Grifol-Clar E, Alvarez-Diaz N, Alvarez-Espejo T,

Cancio-Trujillo JM, Mora-Fernández J, Pareja-Sierra T,

Barrera-Crispín R, et al: Predictive factors of gait recovery after

hip fracture: A scoping review. Age Ageing.

54(afaf057)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Foss NB, Kristensen MT and Kehlet H:

Anaemia impedes functional mobility after hip fracture surgery. Age

Ageing. 37:173–178. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Kim JL, Jung JS and Kim SJ: Prediction of

ambulatory status after hip fracture surgery in patients over 60

years old. Ann Rehabil Med. 40:666–674. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Malik AT, Quatman-Yates C, Phieffer LS, Ly

TV, Khan SN and Quatman CE: Factors associated with inability to

bear weight following hip fracture surgery: An analysis of the

ACS-NSQIP Hip fracture procedure targeted database. Geriatr Orthop

Surg Rehabil. 10(2151459319837481)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Xiang Z, Chen Z, Wang P, Zhang K, Liu F,

Zhang C, Wong TM, Li W and Leung F: The effect of early

mobilization on functional outcomes after hip surgery in the

Chinese population-A multicenter prospective cohort study. J Orthop

Surg (Hong Kong). 29(23094990211058902)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Goubar A, Martin FC, Potter C, Jones GD,

Sackley C, Ayis S and Sheehan KJ: The 30-day survival and recovery

after hip fracture by timing of mobilization and dementia: A UK

database study. Bone Joint J. 103-B:1317–1324. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Manosroi W, Koetsuk L, Phinyo P,

Danpanichkul P and Atthakomol P: Predictive model for prolonged

length of hospital stay in patients with osteoporotic femoral neck

fracture: A 5-year retrospective study. Front Med (Lausanne).

9(1106312)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Vittinghoff E and McCulloch CE: Relaxing

the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression.

Am J Epidemiol. 165:710–718. 2007.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR

and Feinstein AR: A simulation study of the number of events per

variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol.

49:1373–1379. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Sperandei S: Understanding logistic

regression analysis. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 24:12–18.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK and Hosmer

DW: Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression.

Source Code Biol Med. 3(17)2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Chowdhury MZI and Turin TC: Variable

selection strategies and its importance in clinical prediction

modelling. Fam Med Community Health. 8(e000262)2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

Munoz-Pichardo JM, Pino-Mejias R,

Garcia-Heras J, Ruiz-Munoz F and Luz Gonzalez-Regalado M: A

multivariate Poisson regression model for count data. J Appl Stat.

48:2525–2541. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

49

|

Charlson ME, Carrozzino D, Guidi J and

Patierno C: Charlson comorbidity index: A critical review of

clinimetric properties. Psychother Psychosom. 91:8–35.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

50

|

Kim JH: Multicollinearity and misleading

statistical results. Korean J Anesthesiol. 72:558–569.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

51

|

Tomaschek F, Hendrix P and Baayen RH:

Strategies for addressing collinearity in multivariate linguistic

data. J Phon. 71:249–267. 2018.

|

|

52

|

Andaloro S, Cacciatore S, Risoli A, Comodo

RM, Brancaccio V, Calvani R, Giusti S, Schlögl M, D'Angelo E,

Tosato M, et al: Hip fracture as a systemic disease in older

adults: A narrative review on multisystem implications and

management. Med Sci (Basel). 13(89)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

53

|

Hulsbæk S, Larsen RF and Troelsen A:

Predictors of not regaining basic mobility after hip fracture

surgery. Disabil Rehabil. 37:1739–1744. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

54

|

Gray R, Lacey K, Whitehouse C, Dance R and

Smith T: What factors affect early mobilisation following hip

fracture surgery: A scoping review. BMJ Open Qual. 12 (Suppl

2)(e002281)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

55

|

Magaziner J, Chiles N and Orwig D:

Recovery after Hip fracture: Interventions and their timing to

address deficits and desired outcomes-evidence from the baltimore

hip studies. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. 83:71–81.

2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

56

|

Monkuntod K, Aree-Ue S and Roopsawang I:

Associated factors of functional ability in older persons

undergoing hip surgery immediately post-hospital discharge: A

prospective study. J Clin Med. 12(6258)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

57

|

Istianah U, Nurjannah I and Magetsari R:

Post-discharge complications in postoperative patients with hip

fracture. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 14:8–13. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

58

|

Elli S, Contro D, Castaldi S, Fornili M,

Ardoino I, Caserta AV and Panella L: Caregivers' misperception of

the severity of hip fractures. Patient Prefer Adherence.

12:1889–1895. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

59

|

Yoo JI, Lee YK, Koo KH, Park YJ and Ha YC:

Concerns for older adult patients with acute hip fracture. Yonsei

Med J. 59:1240–1244. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

60

|

Iosifidis M, Iliopoulos E, Panagiotou A,

Apostolidis K, Traios S and Giantsis G: Walking ability before and

after a hip fracture in elderly predict greater long-term

survivorship. J Orthop Sci. 21:48–52. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

61

|

Adulkasem N, Phinyo P, Khorana J,

Pruksakorn D and Apivatthakakul T: Prognostic factors of 1-year

postoperative functional outcomes of older patients with

intertrochanteric fractures in Thailand: A retrospective cohort

study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 18(6896)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

62

|

Kristensen MT: Factors affecting

functional prognosis of patients with hip fracture. Eur J Phys

Rehabil Med. 47:257–264. 2011.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

63

|

Handoll HH, Cameron ID, Mak JC, Panagoda

CE and Finnegan TP: Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for older

people with hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

11(CD007125)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

64

|

Ravi B, Pincus D, Choi S, Jenkinson R,

Wasserstein DN and Redelmeier DA: Association of duration of

surgery with postoperative delirium among patients receiving hip

fracture repair. JAMA Netw Open. 2(e190111)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

65

|

Tarrant SM, Attia J and Balogh ZJ: The

influence of weight-bearing status on post-operative mobility and

outcomes in geriatric hip fracture. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg.

48:4093–4103. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

66

|

Xu BY, Yan S, Low LL, Vasanwala FF and Low

SG: Predictors of poor functional outcomes and mortality in

patients with hip fracture: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet

Disord. 20(568)2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

67

|

Wong RMY, Qin J, Chau WW, Tang N, Tso CY,

Wong HW, Chow SK, Leung KS and Cheung WH: Prognostic factors

related to ambulation deterioration after 1-year of geriatric hip

fracture in a Chinese population. Sci Rep. 11(14650)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|