Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver

disease (MASLD), formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver

disease, has become a global health concern (1), particularly in Asia, 41% of cases

occur in people with BMI <25 kg/m2, and 19% in those

with BMI <23 kg/m2, with no significant difference in

liver histology compared with higher-BMI groups (2). In Taiwan, the prevalence of metabolic

syndrome (MS), a condition associated with MASLD, increased from

11.5% during 2003-2004 (3,4) to more than one-third of adults in

2017-2020, increasing with age (5).

Numerous studies have explored established factors, including being

overweight, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, energy imbalance,

metabolic inflammation, an unhealthy diet and a sedentary

lifestyle, that contribute to these conditions (1,3).

However, reliable biomarkers for MASLD, particularly for early

detection or risk prediction in asymptomatic individuals, remain

elusive, as emphasized in the latest Asian Pacific Association for

the Study of the Liver guidelines (2). This critical gap underscores the need

to explore novel pathogenic mechanisms. The role of

gastroenteropancreatic hormones (GEPHs) in the early pathogenesis

of MASLD, especially among seemingly healthy females, a key target

for prevention, is poorly understood. The present study aimed to

investigate GEPH profiles in this population.

GEPHs serve a crucial role in the regulation of

appetite, body weight and metabolic homeostasis, acting as key

mediators between the central nervous system and peripheral tissue

(6,7). Ghrelin exists in two forms: Acyl

ghrelin stimulates appetite, while des-acyl ghrelin, previously

thought to be inactive, suppresses appetite (8,9).

Des-acyl ghrelin possesses broad metabolic protective properties

beyond appetite suppression, including anti-inflammatory,

anti-fibrotic and insulin-sensitizing effects in multiple tissues

(10,11). In addition to ghrelin, other GEPHs,

regulate satiety, energy balance and metabolic dysfunction

(12-14),

including obestatin, nesfatin-1, cholecystokinin (CCK), gastric

inhibitory peptide (GIP), glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1),

oxyntomodulin (OXM), peptide YY (PYY), pancreatic polypeptide (PP)

and amylin. Understanding the interactions between these hormones

and their metabolic effects is key for designing preventive and

targeted therapies for MASLD and metabolic disorder. However,

comprehensive studies simultaneously evaluating multiple GEPHs to

identify the most salient predictor of MASLD risk within a specific

ethnic population are currently lacking.

The present study employed correlation, regression

and path analysis to explore the connections and potential causal

association between a broad panel of 11 GEPHs and MASLD in

seemingly healthy females. The primary objective was to identify

the most influential biomarkers predicting MASLD.

Materials and methods

Study design and data collection

The present study adopted a hospital-based

prospective observational design, in accordance with the Helsinki

Declaration, approved by the Institutional Review Board, Cheng Hsin

General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan [approval nos. (665) 107A-37,

(732) 108A-48 and (736) 108A-52] and was performed according to the

Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection

Program guidelines (aahrpp.org/).

Subjects were randomly selected from individuals undergoing

voluntary health check-ups at the Cheng Hsin Healthy Management

Center, Taipei, Taiwan between June 2019 and July 2020. Initial

recruitment included 150 participants, comprising 139 females and

11 males. The objective was to identify the most influential

biomarkers predicting MASLD in the apparently healthy population.

However, the small number of male participants precluded meaningful

sex-stratified analysis or reliable adjustment for sex as a

potential confounder. Therefore, the present study investigated

only the female patients aged 18-65 years old. The inclusion

criteria were age ≥18 years and complete anthropometric measurement

and laboratory data; exclusion criterion was a history of alcohol

consumption.

‘Apparently healthy’ was operationally defined as:

i) No prior diagnosis of chronic diseases requiring medication; ii)

no hospitalization in the past 6 months and iii) voluntarily

participating in health check-ups. A standardized questionnaire

collected basic information, such as sex, age and medical history.

Height, weight, waist circumference (WC) and blood pressure were

measured. The following data were obtained from the database of the

health examination center: Fasting blood sugar (FBS), triglyceride

(TG), total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

(LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), alanine

aminotransferase (ALT) and laboratory tests for acyl ghrelin,

des-acyl ghrelin, obestatin, nesfatin-1, CCK, GIP, GLP-1, OXM, PP,

PYY and amylin. Body mass index (BMI), an indicator used to

identify obese individuals, was calculated as body weight

(kg)/[body height (m)]2 (15). The TG/HDL-C ratio is indicative of

insulin resistance (16,17). The diagnosis of MS criteria was made

when at least three of the five following risk determinants were

present: WC ≥80 cm; blood pressure >130/85 mmHg or use of

antihypertensive medications; HDL-C <50 mg/dl; FBS ≥100 mg/dl or

regular treatment for diabetes mellitus and TG ≥150 mg/dl (5). Lipid accumulation product (LAP) was

employed as a blood-based surrogate marker for MASLD, serving as a

non-invasive alternative to imaging or liver biopsy. LAP was

calculated as: [(WC (cm)-58) x TG (mmol/l)] (18,19).

WC values ≤58 cm were adjusted to 59 cm to ensure a non-positive

LAP value. Abnormal metabolic indicators were defined as FBS ≥126

mg/dl, TG ≥150 mg/dl and HDL-C <50 mg/dl.

Measurement of serum GEPHs

Enzyme immunoassays for hormones were performed

according to the manufacturers' protocols in a single, blinded

batch using commercial kits. These included acyl ghrelin, des-acyl

ghrelin (A05106, A05119; all Bertin Pharma), obestatin, CCK, GIP,

GLP-1, OXM, PYY, amylin (S-1284, S-1205, S-1273, S-1359, S-1272,

S-1187; all Bachem), nesfatin-1and OXM (EK-003-26, EK-028-22;

bothPhoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc) (19).

Statistical analysis

The analysis was conducted using Social Sciences

Statistics Package version 20.0 (IBM Corp.). Data are presented as

mean ± SD for continuous variables. Bivariate correlation analysis

was performed using Spearman's correlation to assess the

association between age, GEPHs (including acyl ghrelin, des-acyl

ghrelin, obestatin, nesfatin-1, CCK, GIP, GLP-1, OXM, PYY, PP and

amylin) and metabolic parameters (BMI, TG/HDL-C ratio, LAP and

ALT). SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.) software was applied for

regression and path analysis. For multivariable analysis, separate

forward-selected regression models were constructed for each

metabolic outcome, including BMI, WC, FBS, TG, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C.

A total of 12 candidate predictors, comprising age and 11 GEPHs,

were evaluated. Variables were retained in the final model only if

they met the criteria of P<0.05, ΔR² >3% and variance

inflation factor (VIF) <5 to ensure both statistical and

explanatory robustness while minimizing multicollinearity. Notably,

predictors showing significant bivariate correlations were excluded

from the final multivariate models if they no longer contributed

independently after adjusting for other covariates or if they

exhibited excessive shared variance (VIF ≥5). Forward regression

was employed to identify significant predictor variables for

inclusion in the subsequent path analysis. Model fit was evaluated

to determine how well the proposed structure aligned with the

observed data (20,21).

GEPHs retained in the final model (des-acyl ghrelin,

and obestatin) and age underwent exploratory path analysis,

Mahalanobis distance-based classification was applied. P<0.05

was considered to indicate a statistically significant

difference.

Results

Characteristics of the study

subjects

The study cohort consisted of 139 female

participants with a mean age of 38.4±10.1 years, BMI of 23.1±3.8

kg/m2 and WC of 73.2±9.4 cm (Table I). Notably, 9.4% of these

participants met the Taiwanese MS criteria, despite being recruited

from the healthy management center without prior diagnosis of major

chronic disease. This finding highlights the potential

underdiagnosis of metabolic risk in apparently healthy females and

underscores the value of early metabolic screening in normal-weight

individuals (mean BMI <24 kg/m2).

| Table ICharacteristics of the study

subjects. |

Table I

Characteristics of the study

subjects.

| Variable | All | Non-MS (n=126) | MS (n=13) | P-value |

|---|

| Age, years | 38.4±10.1 | 37.9±10.1 | 43.6±9.3 | 0.050 |

| BMI,

kg/m2 | 23.1±3.8 | 22.4±3.3 | 29.0±2.6 | <0.001 |

| WC, cm | 73.2±9.4 | 71.4±7.9 | 89.8±5.0 | <0.001 |

| FBS, mg/dl | 95.0±11.3 | 93.3±8.8 | 111.4±18.6 | <0.001 |

| TG, mg/dl | 77.0±50.7 | 71.4±46.7 | 130.7±57.8 | <0.001 |

| TC, mg/dl | 193.7±34.9 | 192.5±33.1 | 205.9±49.1 | 0.190 |

| LDL-C, mg/dl | 117.2±32.1 | 114.7±30.1 | 141.1±42.0 | 0.040 |

| HDL-C, mg/dl | 60.4±13.3 | 62.1±12.8 | 44.5±5.6 | <0.001 |

| ALT, U/l | 19.2±14.7 | 17.1±7.9 | 40.2±36.4 | <0.001 |

| TG/HDL-C ratio | 1.4±1.3 | 1.3±1.1 | 3.0±1.4 | <0.001 |

| LAP, cm mmol/l | 14.9±17.0 | 11.6±11.8 | 47.6±24.3 | <0.001 |

| Acyl ghrelin,

pg/ml | 50.3±30.0 | 51.0±29.6 | 43.5±34.5 | 0.392 |

| Des-acyl ghrelin,

pg/ml | 341.2±199.5 | 353.8±199.9 | 219.8±154.7 | 0.021 |

| Obestatin,

ng/ml | 2.6±1.3 | 2.6±1.3 | 2.4±0.8 | 0.645 |

| Nesfatin-1,

ng/ml | 1.0±6.1 | 1.0±6.4 | 0.2±0.2 | 0.630 |

| CCK, ng/ml | 2.4±5.5 | 2.4±5.8 | 2.1±1.9 | 0.824 |

| GIP, ng/ml | 0.3±0.2 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.3±0.2 | 0.843 |

| GLP-1, ng/ml | 0.05±0.05 | 0.05±0.04 | 0.08±0.11 | 0.022 |

| OXM, ng/ml | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.3 | 0.9±0.2 | 0.655 |

| PYY, ng/ml | 0.6±0.3 | 0.6±0.3 | 0.6±0.2 | 0.782 |

| PP, ng/ml | 0.2±0.8 | 0.2±0.8 | 0.2±0.4 | 0.931 |

| Amylin, ng/ml | 0.8±0.7 | 0.8±0.8 | 0.7±0.6 | 0.828 |

Patients with MS were older and had significantly

higher BMI, WC, FBS, TG, LDL-C, ALT, TG/HDL-C ratio, LAP and GLP-1,

as well as lower HDL-C and des-acyl ghrelin levels, than non-MS

subjects (Table I).

Association between GEPHs and

metabolic factors

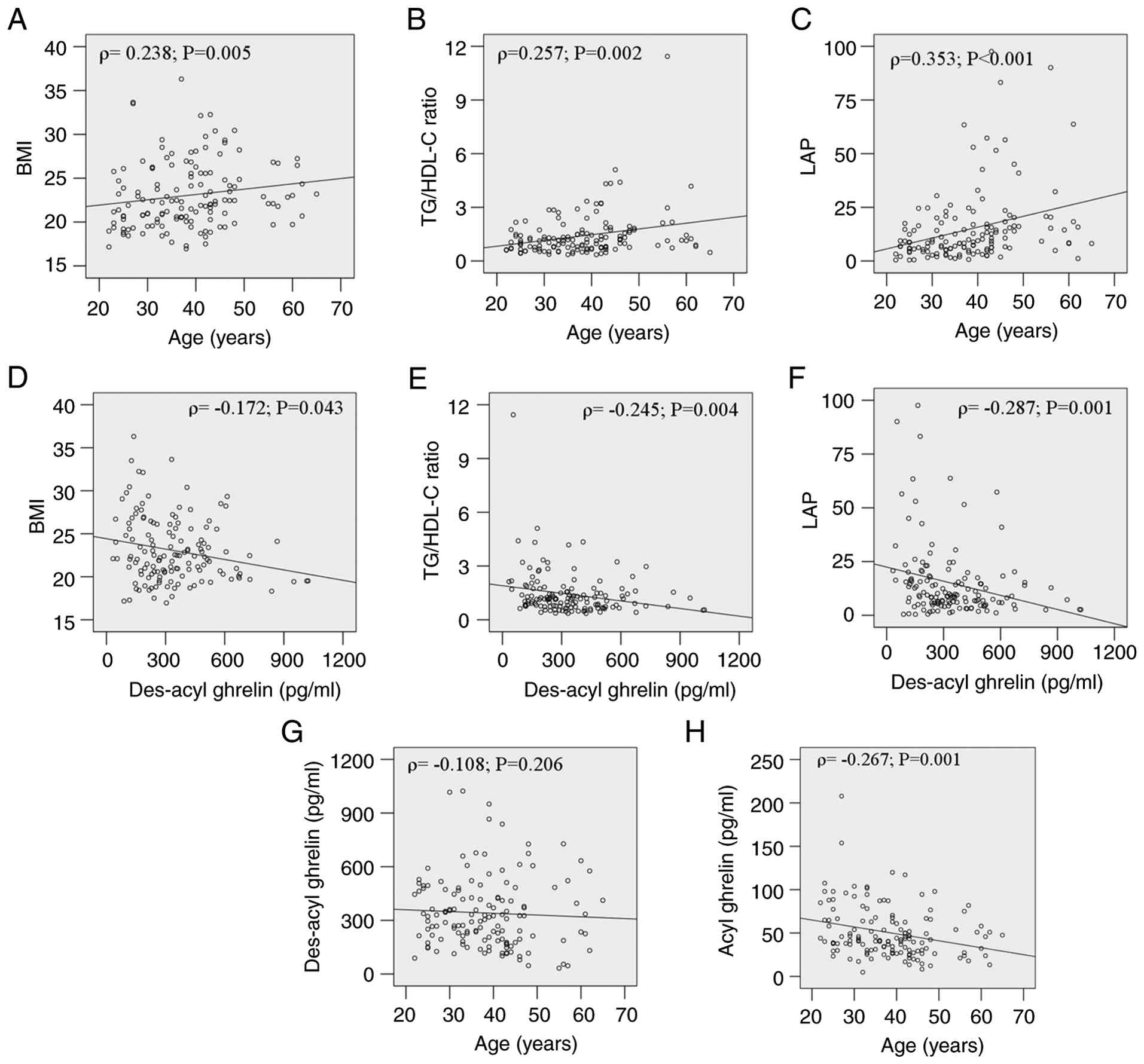

Bivariate correlation analysis revealed significant

associations between age, GEPH and metabolic outcomes (Table II; Fig.

1). Age, serum acyl ghrelin and des-acyl ghrelin correlated

positively with BMI and TG/HDL-C ratio, while age, serum acyl

ghrelin, des-acyl ghrelin and obestatin were correlated with LAP.

Age also had a significant relationship with ALT. No correlation

existed between age and des-acyl ghrelin (Fig. 1G), while acyl-ghrelin declined

significantly with age (Fig. 1H).

Despite these bivariate associations, forward-selected multivariate

regression models using age and all GEPHs as candidate variables

identified independent predictors for metabolic abnormalities

(Table III). Age positively

predicted BMI (β=0.060), WC (β=0.223), FBS, TG, TC and LDL-C.

Des-acyl ghrelin was independently associated with BMI (β=-0.004)

and WC (β=-0.014) but positively associated with HDL-C (β=0.023).

Obestatin predicted FBS (β=2.028). Notably, while significant in

the bivariate correlations (Table

II), acyl-ghrelin was not retained in the final

forward-selected model (Table

III) as it did not meet the statistical criterion for entry

after accounting for variance explained by the other variables.

Overall, age was the strongest predictor, associated with all

sevenmetabolic parameters . Among GEPHs, des-acyl ghrelin showed

the significant associations with the highest number of metabolic

parameters (3/7), while other GEPHs showed significant associations

with ≤1 parameter (Table

III).

| Table IICorrelations between variables and

metabolic factors. |

Table II

Correlations between variables and

metabolic factors.

| | BMI | TG/HDL-C ratio | LAP | ALT |

|---|

| Factor | ρ | P-value | ρ | P-value | ρ | P-value | ρ | P-value |

|---|

| Age | 0.238 | 0.005 | 0.257 | 0.002 | 0.353 | <0.001 | 0.375 | <0.001 |

| Acyl ghrelin | -0.194 | 0.022 | -0.245 | 0.004 | -0.282 | 0.001 | -0.049 | 0.567 |

| Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.172 | 0.043 | -0.245 | 0.004 | -0.287 | 0.001 | -0.046 | 0.595 |

| Obestatin | -0.128 | 0.134 | -0.162 | 0.057 | -0.235 | 0.005 | -0.035 | 0.685 |

| Nesfatin-1 | 0.066 | 0.438 | 0.064 | 0.454 | 0.112 | 0.189 | 0.022 | 0.801 |

| CCK | -0.052 | 0.547 | -0.119 | 0.162 | -0.129 | 0.131 | -0.008 | 0.927 |

| GIP | -0.058 | 0.497 | -0.029 | 0.733 | -0.082 | 0.339 | -0.041 | 0.633 |

| GLP-1 | -0.126 | 0.138 | -0.152 | 0.074 | -0.155 | 0.068 | -0.143 | 0.092 |

| OXM | -0.025 | 0.769 | 0.059 | 0.487 | -0.011 | 0.895 | 0.105 | 0.217 |

| PYY | -0.063 | 0.462 | 0.023 | 0.791 | -0.010 | 0.905 | 0.079 | 0.354 |

| PP | -0.002 | 0.977 | 0.071 | 0.404 | 0.055 | 0.519 | -0.103 | 0.229 |

| Amylin | -0.118 | 0.165 | 0.039 | 0.648 | -0.049 | 0.567 | -0.093 | 0.278 |

| Table IIIVariables significantly associated

with age and gastroenteropancreatic hormones using forward-selected

regression model. |

Table III

Variables significantly associated

with age and gastroenteropancreatic hormones using forward-selected

regression model.

| | Age | Des-acyl

ghrelin | Obestatin |

|---|

| Variable | Estimated β | P-value | Estimated β | P-value | Estimated β | P-value |

|---|

| BMI | 0.060 | 0.050 | -0.004 | 0.015 | - | - |

| WC | 0.223 | 0.003 | -0.014 | <0.001 | - | - |

| FBS | 0.519 | <0.001 | - | - | 2.028 | 0.042 |

| TG | 1.440 | <0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| TC | 0.858 | 0.024 | - | - | - | - |

| LDL-C | 0.601 | 0.013 | - | - | - | - |

| HDL-C | - | - | 0.023 | <0.001 | - | - |

Potential mechanism of metabolic

abnormalities

Path analysis was performed to determine whether

age, des-acyl ghrelin and obestatin influence metabolic

abnormalities and contribute to the onset of MASLD through

mediators such as BMI and WC. The discriminating criteria for

metabolic abnormalities in female patients are BMI ≥24

kg/m2, WC ≥80 cm, FBS ≥126 mg/dl, TG ≥150 mg/dl, TC ≥200

mg/dl, LDL-C ≥100 mg/dl and HDL-C <50 mg/dl (4,5). Serum

des-acyl ghrelin levels were not significantly affected by age

(β=-0.003, P=0.560; Table IV). The

analyses for general metabolic abnormalities (Table IV) highlight the pervasive

influence of age, which was a significant predictor in 4 out of 7

final models (for WC, FBS, TG, and TC). In comparison, des-acyl

ghrelin was a significant predictor in 3 models (for BMI, WC, and

HDL-C). These findings were derived from a systematically

comparison of parallel models using either BMI or WC as the primary

adiposity measure. This approach revealed that adiposity measures

often served as both significant predictors and potential

mediators.

| Table IVIdentification of metabolic

abnormality pathways using path analysis. |

Table IV

Identification of metabolic

abnormality pathways using path analysis.

| A, Age |

|---|

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

|---|

| 1 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.003 | 0.560 | 0.560 |

| 2 | Obestatin | -1.685 | 0.011 | 0.011 |

| 3 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.001 | 0.737 | 0.038 |

| | Obestatin | -1.663 | 0.013 | |

| B, BMI |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.004 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| 2 | Obestatin | -0.233 | 0.352 | 0.352 |

| 3 | Age | 0.061 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

| 4 | Age | 0.055 | 0.088 | 0.022 |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.004 | 0.017 | |

| | Obestatin | -0.081 | 0.748 | |

| C, WC |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.014 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Obestatin | -1.159 | 0.061 | 0.061 |

| 3 | Age | 0.241 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| 4 | Age | 0.212 | 0.006 | <0.001 |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.013 | <0.001 | |

| | Obestatin | -0.592 | 0.314 | |

| D, FBS |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Age | 0.458 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | BMI | 1.203 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3 | WC | 0.481 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Obestatin | 0.950 | 0.025 | 0.025 |

| 5 | Age | 0.444 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| | BMI | 1.064 | <0.001 | |

| | Obestatin | 1.956 | 0.003 | |

| 6 | Age | 0.414 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| | WC | 0.412 | <0.001 | |

| | Obestatin | 2.134 | 0.001 | |

| E, TG |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Age | 1.424 | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| 2 | BMI | 3.710 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| 3 | WC | 1.761 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.042 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

| 5 | Age | 1.223 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| | BMI | 2.882 | 0.010 | |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.027 | 0.201 | |

| 6 | Age | 1.084 | 0.009 | <0.001 |

| | WC | 1.33 | 0.005 | |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.021 | 0.334 | |

| F, TC |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Age | 0.840 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| 2 | BMI | 1.547 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

| 3 | WC | 0.454 | 0.155 | 0.155 |

| 4 | Age | 0.767 | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| | BMI | 1.215 | 0.118 | |

| 5 | Age | 0.784 | 0.009 | 0.012 |

| | WC | 0.233 | 0.469 | |

| G, LDL-C |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Age | 0.840 | 0.004 | 0.004 |

| 2 | BMI | 1.547 | 0.056 | 0.056 |

| 3 | WC | 0.454 | 0.155 | 0.155 |

| 4 | Age | 0.516 | 0.057 | <0.001 |

| | BMI | 2.518 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | Age | 0.480 | 0.076 | 0.0013 |

| | WC | 0.783 | 0.008 | |

| H, HDL-C |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | BMI | -1.376 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | WC | -0.624 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | 0.025 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 4 | BMI | -1.204 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | 0.015 | <0.001 | |

| 5 | WC | -0.480 | 0.018 | <0.001 |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | 0.023 | <0.001 | |

HDL-C (Table IV),

both BMI (β=-1.204) and WC (β=-0.480) were significant predictors

alongside des-acyl ghrelin. Furthermore, in the case of TG

(Table IV-E), the effect of age

was partially mediated by WC, as evidenced by the attenuation of

the direct effect co-efficient from β=1.424 to β=1.084 after

including WC.

A consistent finding across all these analyses was

that both the BMI-based and WC-based models demonstrated a poor

overall goodness-of-fit, indicating that the simple linear

structures proposed do not fully capture the complexity of the

metabolic interrelationships.

Potential mechanism of MASLD

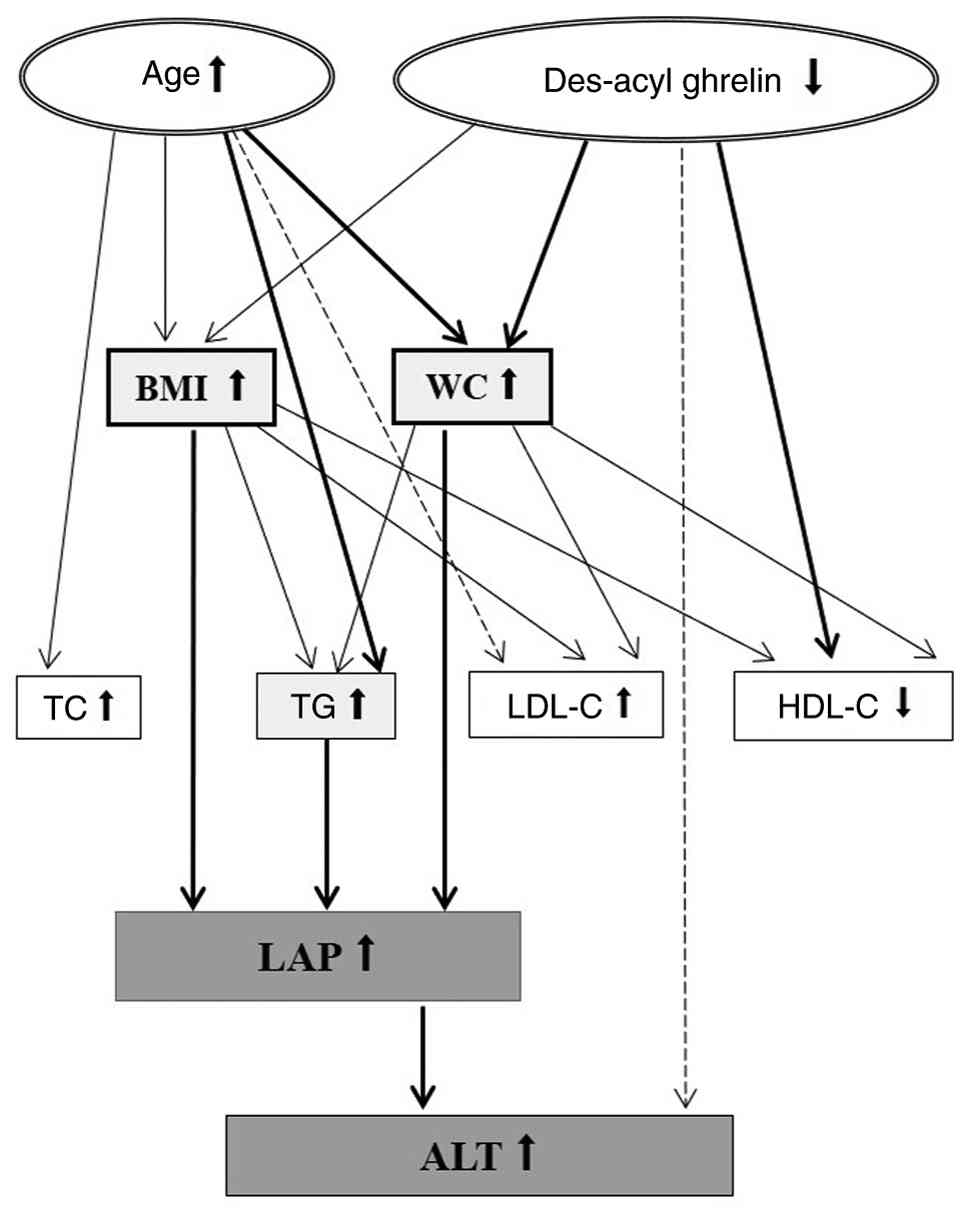

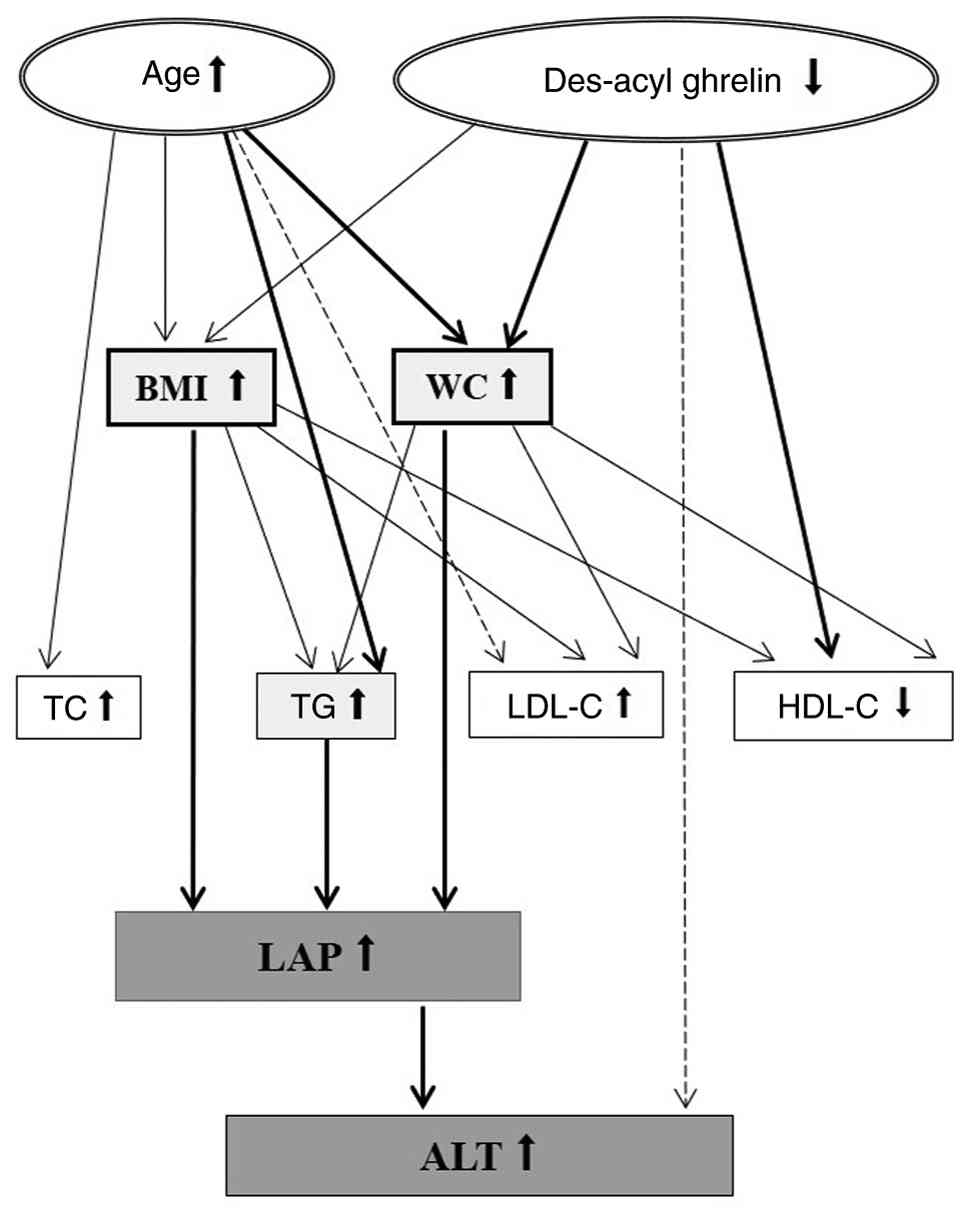

To investigate the potential mechanism of MASLD,

path analyses were conducted for its key indicators, LAP and ALT,

systematically comparing parallel models that incorporated either

BMI or WC as the primary adiposity measure (Table V). The analyses for LAP revealed

clear patterns of full mediation (Table

V). The significant total effect of age on LAP (β=0.517) became

non-significant in the final model that included WC as a mediator.

Similarly, the significant total effect of des-acyl ghrelin on LAP

(β=-0.024) became non-significant in the final model that included

BMI as its mediator. For ALT (Table

V-B), LAP itself emerged as the most significant direct

predictor (β=0.338) and also functioned as a key mediator. The

initial significant association between age and ALT (β=0.311)

became non-significant after accounting for LAP. This finding was

consistent in both the BMI-based and WC-based models, where LAP

maintained a strong, direct path to ALT (final model β=0.338, ),

suggesting the effect of age on liver enzymes is transmitted

through liver fat accumulation. In summary, these analyses

elucidate the key role of age and serum des-acyl ghrelin in the

progression of MASLD. Their influence, however, appears to be

largely indirect. Adiposity measures like BMI and WC act as crucial

mediators, connecting these initial factors to downstream LAP,

which in turn impacts ALT. This highlights a potential cause for

MASLD progression (Fig. 2).

| Figure 2Pathways of MASLD development.

Upstream factors such as age and des-acyl ghrelin on BMI and WC are

associated with metabolic markers such as TG, LDL-C and HDL-C. BMI,

WC and TG promote LAP (an indicator for MASLD), which impacts ALT

levels and is an essential indicator of liver health. Thick lines

represent the high correlation (R2>0.6). The solid

and dotted lines indicate significant (P<0.05) and borderline

significant (0.05<P<0.06) results, respectively. BMI, body

mass index; WC, waist circumference; TG, triglyceride; TC, total

cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HDL-C,

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LAP, lipid accumulation

product; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; MASLD, metabolic

dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. |

| Table VProposed physiological pathways

linking LAP and ALT identified through path analysis modeling. |

Table V

Proposed physiological pathways

linking LAP and ALT identified through path analysis modeling.

| A, LAP |

|---|

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

|---|

| 1 | Age | 0.517 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 2 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.024 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| 3 | TG | 0.269 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 4 | TC | 0.152 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 5 | LDL-C | 0.176 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6 | HDL-C | -0.572 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 7 | BMI | 2.931 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 8 | WC | 1.390 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 9 | Age | 0.076 | 0.235 | <0.001 |

| | TG | 0.218 | <0.001 | |

| | TC | -0.008 | 0.916 | |

| | LDL-C | 0.014 | 0.845 | |

| | HDL-C | -0.031 | 0.745 | |

| | BMI | 1.980 | <0.001 | |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.003 | 0.296 | |

| 10 | Age | -0.035 | 0.452 | <0.001 |

| | TG | 0.214 | <0.001 | |

| | TC | -0.029 | 0.591 | |

| | HDL-C | 0.056 | 0.423 | |

| | LDL-C | 0.043 | 0.409 | |

| | WC | 1.038 | <0.001 | |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | 0.001 | 0.604 | |

| B, ALT |

| Model | Variable | Standardized β | P-value | Model fitting

P-value |

| 1 | Age | 0.311 | 0.012 | 0.012 |

| 2 | BMI | 1.562 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3 | WC | 0.574 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 4 | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.013 | 0.013 | 0.014 |

| 5 | LAP | 0.389 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 6 | Age | 0.1328 | 0.2543 | <0.001 |

| | BMI | 0.7436 | 0.050 | |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.0065 | 0.094 | |

| | LAP | 0.2570 | 0.004 | |

| 7 | Age | 0.125 | 0.308 | <0.001 |

| | WC | 0.0641 | 0.734 | |

| | Des-acyl

ghrelin | -0.0016 | 0.059 | |

| | LAP | 0.3378 | 0.001 | |

Prediction of MASLD using age and

serum des-acyl ghrelin

Mahalanobis distance analysis was performed to

determine whether age and serum des-acyl ghrelin were key

predictors of MASLD. LAP, a powerful tool for diagnosing metabolic

disorders, was used with a threshold of 31.6 for MASLD (18). Sensitivity and specificity were

71.43 and 71.20%, respectively, for individuals with LAP

>31.6.

Discussion

MASLD and metabolic abnormalities are increasingly

recognized as notable health concerns, particularly in aging and

hormonal regulation (10,12-15,17,22-24).

To assess MASLD, the present study used the LAP, a simple and

non-invasive measure that is associated with liver steatosis and

fibrosis (18). Although liver

biopsy is more accurate, its invasive nature limits its suitability

for initial screening and monitoring. Therefore, LAP provides a

practical and patient-friendly alternative for evaluating the risk

and severity of MASLD. Based on the screening results, subsequent

analysis should prioritize hormones demonstrating the strongest

statistical associations. The present GEPH survey of apparently

healthy female patients demonstrated des-acyl ghrelin as the

strongest and most consistent predictor of the risk of MASLD, along

with age. While extensive literature implicates multiple GEPHs

(GLP-1, PYY and CCK) in the pathogenesis of metabolic disorders and

MASLD, predominantly in populations with higher body weight,

diabetes or differing ethnic backgrounds (12-14),

none showed predictive strength comparable with des-acyl ghrelin in

the present cohort. This divergence may arises from two key

factors: First, unlike earlier studies (12-14)

that typically assess one or two hormones in isolation, the present

approach integrated forward regression and path analysis to

evaluate multiple GEPHs, capturing their interactive effects.

Second, the key role of des-acyl ghrelin in the present cohort may

reflect population-specific hormonal drivers associated with early

MASLD development, consistent with its reported metabolic

protective functions (9,10). Together, age and des-acyl ghrelin

constitute key upstream factors determinants of MASLD and metabolic

disturbance, primarily mediated through increased WC and BMI, and

demonstrated utility in stratifying MASLD risk within this group.

Therefore, monitoring des-acyl ghrelin levels in combination with

age, even in individuals who are neither obese nor of normal

weight, may offer a biologically grounded approach for screening

early MASLD risk in East Asian female populations. This strategy

may help identify people at higher risk for MASLD before symptoms

appear, supporting the value of tracking body weight and WC for

early prevention.

Age was a fundamental upstream driver of metabolic

abnormalities and MASLD in the present cohort. Age showed a

significant association with key metabolic indicators (BMI,

TG/HDL-C ratio, LAP and ALT), suggesting as patients get older,

they become more susceptible to metabolic dysfunction, such as

MASLD. Consistently, Alexander et al (15) demonstrated that aging, independent

of BMI, worsens metabolic dysregulation. Path analysis confirmed

that age substantially increased MASLD risk via promoting central

adiposity (elevated WC). This extends findings by Yuan et al

(24) of aging as an independent

MASLD risk factor in Chinese adults by delineating a central

mechanism mediated by visceral adiposity. The present results are

also consistent with Bilson et al (22), which demonstrated that age-related

visceral fat dysfunction contributes to hepatic steatosis, even in

patients who seem healthy.

Equally pivotal as a modifiable upstream factor,

des-acyl ghrelin emerged with age as a core regulator within the

network of metabolic dysregulation. Des-acyl ghrelin, once

considered an inactive metabolite, serves distinct physiological

roles compared with its acylated counterpart (25), particularly in anti-aging and

anti-inflammatory processes (10,19,26-30).

Unlike studies in populations with obesity (12,13),

such as Ahmad et al (31),

who investigated dysregulated fasting GLP1/ghrelin (using patrial

correlation/logistic regression on five GEPHs, without

distinguishing acyl/des-acyl isoforms), the present study targeted

apparently healthy female patients and performed forward regression

and path analysis on 11 GEPHs (including ghrelin isoforms) to

delineate causal pathways. The present study revealed des-acyl

ghrelin, not acyl ghrelin, as the primary upstream modulator of

MASLD within a comprehensive GEPH framework, aligning with a

cross-ethnic observation (32). In

asymptomatic Korean men with MS, plasma des-acyl ghrelin and total

ghrelin levels are significantly lower than in controls, and both

are inversely correlated with insulin resistance (32). Transgenic models have confirmed the

protective role of des-acyl ghrelin (27,28),

attenuating age-associated wasting and enhancing muscle

performance, while its deficiency accelerates aging and muscle

wasting (28). Des-acyl ghrelin

modulates inflammatory and oxidative stress markers, which is

essential for slowing the aging process (26,28,33).

Circulating ghrelin levels decrease with aging, which may impair

endogenous ghrelin signaling (25,28,33).

The present study similarly found that ghrelin was negatively

correlated with age. In MASLD and MASH, insulin resistance leads to

the accumulation of fatty acids and visceral fat in the liver,

exacerbates hepatic insulin resistance and damages hepatocytes

(21,29,35,36).

Des-acyl ghrelin modulates blood glucose independent of growth

hormone secretagogue receptor (12,25,29,30,36-38),

and has been shown to enhance insulin sensitivity and prevent

diabetes in high-fat diet-fed mice and rats (29,30).

While the present study did not detect a direct association with

FBS, the strong inverse association between des-acyl ghrelin and

the TG/HDL-C suggested an indirect modulatory effect, potentially

via mechanisms involving adipose tissue regulation (12,25,29,37),

hormone balance or glycogen metabolism. Overexpression of des-acyl

ghrelin in mice leads to decreased body size due to decreased food

intake and delayed gastric emptying (39,40).

Des-acyl ghrelin also stimulates basal autophagy via AMPK for lipid

mobilization and counters TNF-α-induced cell damage, aiding in the

improvement of MASLD (34,41). Beyond these cellular effects, recent

evidence suggests des-acyl ghrelin may also act through a

neuroendocrine pathway (42). Lv

et al (42) identified a

novel gut-brain-liver axis by which des-acyl ghrelin alleviates

MASLD. Des-acyl ghrelin increases GLP-1 expression in the nucleus

tractus solitarius and GLP-1 receptor in the paraventricular

nucleus, leading to enhanced hepatic lipid metabolism (42). Disruption of this pathway via GLP-1R

antagonism or hepatic vagotomy significantly attenuates therapeutic

effects of des-acyl ghrelin, underscoring the relevance of this

neural circuit (42). These

findings reinforce the observation that des-acyl ghrelin is

inversely associated with LAP and TG/HDL-C ratio, highlighting its

systemic role in hepatic and lipid regulation. Obestatin, derived

from the ghrelin-obestatin precursor gene (GHRL), also

exhibited a significant negative correlation with LAP and a strong

positive association with fasting glucose. Obestatin shares

functional overlap with des-acyl ghrelin in stimulating

preadipocyte differentiation, promoting adipocyte fatty acid

uptake, and inhibiting lipolysis (41). However, its role appears limited.

Other GEPHs, such as OXM, PYY, PP and amylin, did not show any

detectable effects on metabolic abnormalities or MASLD, suggesting

the metabolic relevance is specific to ghrelin-derived peptides,

particularly des-acyl ghrelin.

Incidence of MASLD is similar in postmenopausal

females and males (19 and 22%, respectively), but lower in

premenopausal females (9%) (44),

suggesting sex hormones influence the prevalence of the disease.

Estrogen enhances insulin sensitivity, while androgens increase

insulin resistance (45).

Sex-specific fat distribution patterns also affect the risk of

metabolic disease, with males more prone to visceral fat

accumulation, while postmenopausal patients exhibit increased

central obesity and insulin resistance (46). The role of estrogen in regulating

lipid metabolism, protecting the liver from oxidative damage and

slowing the progression of liver fibrosis may provide partial

protection for premenopausal patients against MS and MASLD

(1). In females, ghrelin levels are

naturally higher than in males and fluctuate with the menstrual

cycle (47). Estrogen directly

stimulates ghrelin-secreting cells in the stomach, increasing the

expression and secretion of ghrelin (47). The interaction between ghrelin and

sex hormones, such as estrogen, serves a crucial role in regulating

appetite and energy balance. For example, the absence of ovaries

increases ghrelin-induced effects, while estrogen therapy can

counteract these (47,48). The interaction between sex hormones

and GPEHs may be a key mechanism in the development of MASLD/MASH.

The complex association between ghrelin and estrogen, especially in

terms of food reward and stress eating, is an area of active

research due to the importance of these hormonal interactions in

metabolic diseases (47,48).

The present findings offer novel insight into the

pathogenesis of MASLD and lay the groundwork for tailored

prevention and therapeutic strategies. However, the study has

limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precluded causal

inference. While path analysis explored associations among GEPHs,

metabolic parameters, and MASLD, it evaluates the statistical

coherence of a prespecified model at a single time point and cannot

establish a temporal sequence or rule out reverse causation.

Second, the modest sample size (n=139), limited statistical power

for subgroup analyses. Future longitudinal studies should include

larger, multicenter, multiethnic cohorts encompassing both sexes

and varying metabolic states (including obesity) along with

analysis of sex hormones, to validate and expand the present

findings. Third, using LAP as a surrogate for MASLD diagnosis,

though non-invasive and scalable, may not accurately reflect the

true severity of the disease compared with gold-standard methods

(biopsy/FibroScan®). Fourth, the present findings are

specific to apparently healthy females in Taiwan. Thus, caution is

warranted in generalizing the results to other populations. Fifth,

the data collection occurred in early 2020, before the global

impact of the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic. While this timing

may raise concerns about the applicability of the findings, it also

provides a valuable pre-pandemic baseline for understanding

metabolic health. As this study included only female participants,

future research should enroll male subjects to enable analysis of

sex differences. The core mechanistic pathway of age and des-acyl

ghrelin influencing adiposity and MASLD reflects stable biological

processes that are unlikely to be altered by temporal shifts. As

such, the present data offer a meaningful reference point for

studies comparing pre- and post-pandemic cohorts.

The present cross-sectional study identified

significant correlations between age, serum des-acyl ghrelin and

metabolic complications, including MASLD, in adult females in

Taiwan. The findings suggest that age and des-acyl ghrelin could

serve as a predictor of metabolic risks. Despite the limited number

of participants, the data underscore the importance of monitoring

serum des-acyl ghrelin levels in preventive medicine. Further

longitudinal studies are essential to validate these associations,

determine the precision and reliability of these predictions and

clarify the specific role of des-acyl ghrelin in MASLD to develop

more accurate predictive models and therapeutic approaches to

manage metabolic diseases.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Clinical

Research Core Laboratory of Taipei Veterans General Hospital,

Taipei, Taiwan for providing experimental space and facilities, as

well as Dr Hsien-Hao Huang (Taipei Veterans General Hospital,

Taipei, Taiwan) for administration assistance.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Taipei Veterans

General Hospital-National Yang-Ming Chiao Tung University Excellent

Physician Scientists Cultivation Program (grant no.

113-V-B-034).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

CYC conceived the study. CY, PYC and CYC performed

the experiments. HHC and WCC confirm the authenticity of all the

raw data. CPL, HHC and WCC analyzed and interpreted data. CPL, WCC

and CYC wrote, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have

read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by The Institutional

Review Board of Cheng Hsin General Hospital [Taipei, Taiwan;

approval nos. (665) 107A-37, (732) 108A-48 and (736) 108A-52] and

conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and

institutional ethical guidelines. The rights and interests of all

participants were fully protected by the Association for the

Accreditation of Human Research Protection Program guidelines.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

European Association for the Study of the

Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes

(EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO).

EASL-EASD-EASO clinical practice guidelines on the management of

metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

Obes Facts. 17:374–444. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Eslam M, Fan JG, Yu ML, Wong VW, Cua IH,

Liu CJ, Tanwandee T, Gani R, Seto WK, Alam S, et al: The Asian

Pacific association for the study of the liver clinical practice

guidelines for the diagnosis and management of metabolic

dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease. Hepatol Int.

19:261–301. 2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Chen CH, Huang MH, Yang JC, Nien CK, Yang

CC, Yeh YH and Yueh SK: Prevalence and risk factors of nonalcoholic

fatty liver disease in an adult population of Taiwan: Metabolic

significance of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in nonobese

adults. J Clin Gastroenterol. 40:745–752. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Wang WS, Wahlqvist ML, Hsu CC, Chang HY,

Chang WC and Chen CC: Age- and gender-specific population

attributable risks of metabolic disorders on all-cause and

cardiovascular mortality in Taiwan. BMC Public Health.

12(111)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Health Promotion Administration, Ministry

of Health and Welfare: Report on the Changes in National

Nutritional and Health Status 2017-2020: Survey on Changes in

National Nutritional and Health Status, 2022 (In Chinese).

https://www.hpa.gov.tw/EngPages/Detail.aspx?nodeid=3999&pid=15562.

|

|

6

|

Chen CY, Fujimiya M, Laviano A, Chang FY,

Lin HC and Lee SD: Modulation of ingestive behavior and

gastrointestinal motility by ghrelin in diabetic animals and

humans. J Chin Med Assoc. 73:225–229. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Chen CY and Tsai CY: From endocrine to

rheumatism: Do gut hormones play roles in rheumatoid arthritis?

Rheumatology (Oxford). 53:205–212. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Chen CY, Asakawa A, Fujimiya M, Lee SD and

Inui A: Ghrelin gene products and the regulation of food intake and

gut motility. Pharmacol Rev. 61:430–481. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Iwakura H, Ensho T and Ueda Y:

Desacyl-ghrelin, not just an inactive form of ghrelin? A review of

current knowledge on the biological actions of desacyl-ghrelin.

Peptides. 167(171050)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Gong Y, Qiu B, Zheng H, Li X, Wang Y, Wu

M, Yan M and Gong Y: Unacylated ghrelin attenuates acute liver

injury and hyperlipidemia via its anti-inflammatory and

anti-oxidative activities. Iran J Basic Med Sci.

27(49)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Kim H, Ranjit R, Claflin DR, Georgescu C,

Wren JD, Brooks SV, Miller BF and Ahn B: Unacylated ghrelin

protects against age-related loss of muscle mass and contractile

dysfunction in skeletal muscle. Aging Cell.

23(e14323)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Koliaki C, Liatis S, Dalamaga M and

Kokkinos A: The implication of gut hormones in the regulation of

energy homeostasis and their role in the pathophysiology of

obesity. Curr Obes Rep. 9:255–271. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Tarantino G and Balsano C:

Gastrointestinal peptides and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 27:11–15. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Bakar RB, Reimann F and Gribble FM: The

intestine as an endocrine organ and the role of gut hormones in

metabolic regulation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 20:784–796.

2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Alexander CM, Landsman PB and Grundy SM:

The influence of age and body mass index on the metabolic syndrome

and its components. Diabetes Obes Metab. 10:246–250.

2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Baneu P, Văcărescu C, Drăgan SR, Cirin L,

Lazăr-Höcher AI, Cozgarea A, Faur-Grigori AA, Crișan S, Gaiță D,

Luca CT and Cozm D: The Triglyceride/HDL ratio as a surrogate

biomarker for insulin resistance. Biomedicines.

12(1493)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Chen CY, Lee WJ, Asakawa A, Fujitsuka N,

Chong K, Chen SC, Lee SD and Inui A: Insulin secretion and

interleukin-1β dependent mechanisms in human diabetes remission

after metabolic surgery. Curr Med Chem. 20:2374–2388.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Ebrahimi M, Seyedi SA, Nabipoorashrafi SA,

Rabizadeh S, Sarzaeim M, Yadegar A, Mohammadi F, Bahri RA, Pakravan

P, Shafiekhani P, et al: Lipid accumulation product (LAP) index for

the diagnosis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A

systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis.

22(41)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Chiang JK and Koo M: Lipid accumulation

product: A simple and accurate index for predicting metabolic

syndrome in Taiwanese people aged 50 and over. BMC Cardiovasc

Disord. 12(78)2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

20

|

Lockie S, Lyons K, Lawrence G and Grice J:

Choosing organics: A path analysis of factors underlying the

selection of organic food among Australian consumers. Appetite.

43:135–146. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Senn TE, Espy KA and Kaufmann PM: Using

path analysis to understand executive function organization in

preschool children. Dev Neuropsychol. 26:445–464. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Bilson J, Sethi JK and Byrne CD:

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A multi-system disease

influenced by ageing and sex, and affected by adipose tissue and

intestinal function. Proc Nutr Soc. 81:146–161. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Muratsu J, Kamide K, Fujimoto T, Takeya Y,

Sugimoto K, Taniyama Y, Morishima A, Sakaguchi K, Matsuzawa Y and

Rakugi H: The combination of high levels of adiponectin and insulin

resistance are affected by aging in non-obese old peoples. Front

Endocrinol (Lausanne). 12(805244)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Yuan Q, Wang H, Gao P, Chen W, Lv M, Bai S

and Wu J: Prevalence and risk factors of metabolic-associated fatty

liver disease among 73,566 individuals in Beijing, China. Int J

Environ Res Public Health. 19(2096)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Delhanty PJ, Neggers SJ and van der Lely

AJ: Mechanisms in endocrinology: Ghrelin: The differences between

acyl- and des-acyl ghrelin. Eur J Endocrinol. 167:601–608.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Shimada T, Furuta H, Doi A, Ariyasu H,

Kawashima H, Wakasaki H, Nishi M, Sasaki H and Akamizu T: Des-acyl

ghrelin protects microvascular endothelial cells from oxidative

stress-induced apoptosis through sirtuin 1 signaling pathway.

Metabolism. 63:469–474. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Cappellari GG, Zanetti M, Semolic A, Vinci

P, Ruozi G, Falcione A, Filigheddu N, Guarnieri G, Graziani A,

Giacca M and Barazzoni R: Unacylated ghrelin reduces skeletal

muscle reactive oxygen species generation and inflammation and

prevents high-fat diet-induced hyperglycemia and whole-body insulin

resistance in rodents. Diabetes. 65:874–886. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Agosti E, De Feudis M, Angelino E, Belli

R, Teixeira MA, Zaggia I, Tamiso E, Raiteri T, Scircoli A, Ronzoni

F, et al: Both ghrelin deletion and unacylated ghrelin

overexpression preserve muscles in aging mice. Aging (Albany NY).

12:13939–13957. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Yuan F, Zhang Q, Dong H, Xiang X, Zhang W,

Zhang Y and Li Y: Effects of des-acyl ghrelin on insulin

sensitivity and macrophage polarization in adipose tissue. J Transl

Int Med. 9:84–97. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Alharbi S: Exogenous administration of

unacylated ghrelin attenuates hepatic steatosis in high-fat

diet-fed rats by modulating glucose homeostasis, lipogenesis,

oxidative stress, and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biomed

Pharmacother. 151(113095)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Ahmad MA, Karavetian M, Moubareck CA, Wazz

G, Mahdy T and Venema K: The association between peptide hormones

with obesity and insulin resistance markers in lean and obese

individuals in the United Arab Emirates. Nutrients.

14(1271)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Cho YH, Lee SY, Jeong DW, Cho AR, Jeon JS,

Kim YJ, Lee JG, Yi YH, Tak YJ, Hwang HR, et al: Metabolic syndrome

is associated with lower plasma levels of desacyl ghrelin and total

ghrelin in asymptomatic middle-aged Korean men. J Obes Metab Syndr.

26:114–121. 2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Amitani M, Amitani H, Cheng KC, Kairupan

TS, Sameshima N, Shimoshikiryo I, Mizuma K, Rokot NT, Nerome Y,

Owaki T, et al: The role of ghrelin and ghrelin signaling in aging.

Int J Mol Sci. 18(1511)2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Ezquerro S, Mocha F, Frühbeck G,

Guzmán-Ruiz R, Valentí V, Mugueta C, Becerril S, Catalán V,

Gómez-Ambrosi J, Silva C, et al: Ghrelin reduces TNF-α-induced

human hepatocyte apoptosis, autophagy, and pyroptosis: Role in

obesity-associated NAFLD. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 104:21–37.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Ezquerro S, Méndez-Giménez L, Becerril S,

Moncada R, Valentí V, Catalán V, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Frühbeck G and

Rodríguez A: Acylated and desacyl ghrelin are associated with

hepatic lipogenesis, β-oxidation and autophagy: Role in NAFLD

amelioration after sleeve gastrectomy in obese rats. Sci Rep.

6(39942)2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Zang P, Yang CH, Liu J, Lei HY, Wang W,

Guo QY, Lu B and Shao JQ: Relationship between acyl and desacyl

ghrelin levels with insulin resistance and body fat mass in type 2

diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 15:2763–2770.

2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Delhanty PJ, Sun Y, Visser JA, van

Kerkwijk A, Huisman M, van Ijcken WF, Swagemakers S, Smith RG,

Themmen AP and van der Lely AJ: Unacylated ghrelin rapidly

modulates lipogenic and insulin signaling pathway gene expression

in metabolically active tissues of GHSR deleted mice. PLoS One.

5(e11749)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Liu X, Guo Y, Li Z and Gong Y: The role of

acylated ghrelin and unacylated ghrelin in the blood and

hypothalamus and their interaction with nonalcoholic fatty liver

disease. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 23:1191–1196. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Asakawa A, Inui A, Fujimiya M, Sakamaki R,

Shinfuku N, Ueta Y, Meguid MM and Kasuga M: Stomach regulates

energy balance via acylated ghrelin and desacyl ghrelin. Gut.

54:18–24. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ariyasu H, Takaya K, Iwakura H, Hosoda H,

Akamizu T, Arai Y, Kangawa K and Nakao K: Transgenic mice

overexpressing des-acyl ghrelin show small phenotype.

Endocrinology. 146:355–364. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Rodríguez A, Gómez-Ambrosi J, Catalán V,

Rotellar F, Valentí V, Silva C, Mugueta C, Pulido MR, Vázquez R,

Salvador J, et al: The ghrelin O-acyltransferase-ghrelin system

reduces TNF-α-induced apoptosis and autophagy in human visceral

adipocytes. Diabetologia. 55:3038–3050. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Lv P, Li H, Li X, Wang X, Yu J and Gong Y:

Intestinal perfusion of unacylated ghrelin alleviated metabolically

associated fatty liver disease in rats via a central glucagon-like

peptide-1 pathway. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol.

326:G643–G658. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Pei XM, Yung BY, Yip SP, Chan LW, Wong CS,

Ying M and Siu PM: Protective effects of desacyl ghrelin on

diabetic cardiomyopathy. Acta Diabetol. 52:293–306. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Long MT, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U,

Ma J, Loomba R, Chung RT and Benjamin EJ: A simple clinical model

predicts incident hepatic steatosis in a community-based cohort:

The Framingham heart study. Liver Int. 38:1495–1503.

2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Mumusoglu S and Yildiz BO: Metabolic

syndrome during menopause. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 17:595–603.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

46

|

de Mutsert R, Gast K, Widya R, de Koning

E, Jazet I, Lamb H, le Cessie S, de Roos A, Smit J, Rosendaal F and

den Heijer M: Associations of abdominal subcutaneous and visceral

fat with insulin resistance and secretion differ between men and

women: The Netherlands epidemiology of obesity study. Metab Syndr

Relat Disord. 16:54–63. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

47

|

Smith A, Woodside B and Abizaid A: Ghrelin

and the control of energy balance in females. Front Endocrinol

(Lausanne). 13(904754)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

48

|

de Souza GO, Wasinski F and Donato J Jr:

Characterization of the metabolic differences between male and

female C57BL/6 mice. Life Sci. 301(120636)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|