Introduction

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) have attracted

attention as promising therapeutic tools because they can silence

disease-related genes (1,2). However, siRNAs undergo rapid

degradation by endogenous nucleases after systemic administration.

Additionally, its hydrophilic nature and high molecular weight

restrict penetration into target cell membranes. Therefore,

developing a siRNA delivery system for target sites is crucial for

inducing therapeutic effects (3).

Several siRNA carriers comprising polymers or lipids have been

investigated (4).

Cationic liposomes are widely used for siRNA

delivery (5). The formation of

siRNA lipoplexes, that is, complexes of siRNA and cationic

liposomes, prevents siRNA degradation by nucleases and improves its

transport into the cytoplasm. The cationic characteristics of

lipoplexes induce binding to negatively charged cell surfaces,

improving intracellular delivery. However, after intravenous

injection, cationic lipoplexes non-specifically interact with

negatively charged serum proteins or erythrocytes, forming

aggregates that accumulate mainly in the lungs (6,7).

To reduce non-specific interactions and

agglutination of cationic lipoplexes with blood components,

polyethylene glycol (PEG) modification of lipoplexes has been

explored (8,9). PEG-modified carriers reportedly

improve siRNA stability and retention in the circulation by

inducing steric hindrance and accumulate in the target tissue as a

result of evading lung accumulation. However, PEG modification

frequently inhibits cellular uptake and endosomal escape, resulting

in reduced gene silencing (8,10). As

an alternative to PEG modification, surface modification of

cationic lipoplexes using anionic materials has been investigated.

For example, coating cationic lipoplexes with anionic polymers has

been reported to attenuate electrostatic interactions with blood

components (11-13).

Several biocompatible anionic polymers, such as hyaluronan (HA),

chondroitin sulfate (CS), and polyglutamic acid (PGA), can minimize

the non-specific interaction of cationic lipoplexes with biological

components. Similarly, incorporation of anionic lipids into

cationic lipoplexes can reduce the surface charge through charge

neutralization, thereby decreasing non-specific interactions with

erythrocytes as reported in our previous study (14). Compared with simple charge

neutralization using anionic lipids, anionic polymer coating

provides additional advantages by enabling functional modification

of lipoplexes through polymer structure and functional properties,

such as prolonged circulation and receptor-mediated

interactions.

Previously, our group reported a simple preparation

method for siRNA lipoplexes [modified ethanol injection (MEI)

method], in which the siRNA solution was rapidly mixed with a small

volume of a lipid-ethanol solution, which could be applicable for

in vitro and in vivo siRNA transfections (15,16).

To extend the usefulness and applicability of this preparation

method, we explored the potential of anionic polymer coating on

siRNA lipoplexes prepared by MEI in the current study.

Biocompatible polymers, including HA, CS, and PGA, were used to

coat cationic siRNA lipoplexes prepared using the MEI method. In

addition, the effects of anionic polymer coating of siRNA

lipoplexes on gene knockdown efficiency and biodistribution were

evaluated.

Materials and methods

Materials

1,2-Dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl

sulfate salt (DOTAP) was obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (now

part of Croda International Plc, Yorkshire, UK).

Dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide (DDAB; product name: DC-1-18)

was obtained from Sogo Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan).

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE;

COATSOME® ME-8181) was purchased from NOF Corporation

(Tokyo, Japan). Ultra-low-molecular-weight hyaluronan (HA-UL;

molecular mass: 7.5 kDa), low-molecular-weight HA (HA-L; 16.7 kDa),

medium-molecular-weight HA (HA-M; 215 kDa), and

high-molecular-weight HA (HA-H; 975 kDa) were purchased from

R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Chondroitin sulfate C

sodium salt (CS; average molecular mass: 35 kDa) was purchased from

FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (Osaka, Japan). Poly-α-L-glutamic

acid sodium salt (PGA; molecular weight: 20500) was purchased from

Sigma-Aldrich (now part of Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

siRNAs

Firefly luciferase siRNA (Luc siRNA, target

sequence: hLuc+, GenBank accession no. AY535007.1),

non-silencing control siRNA (Cont siRNA), and cyanine 5-conjugated

Cont siRNA (Cy5-siRNA) were designed as reported previously

(17) and synthesized by

Sigma-Aldrich (Merck). The siRNA sequences were as follows: Luc

siRNA passenger strand, 5 -CCGUGGUGUUCGUGUCUAAGA-3 , and

guide strand, 5 -UUAGACACGAACACCACGGUA-3 ; Cont siRNA

passenger strand, 5 -GUACCGCACGUCAUUCGUAUC-3 , and guide

strand, 5 -UACGAAUGACGUGCGGUACGU-3 . For Cy5-siRNA, Cy5

dye was conjugated at the 5 -end of the passenger strand of

Cont siRNA.

Preparation of anionic polymer-coated

lipoplexes using the MEI method

siRNA lipoplexes were prepared using the MEI method,

as reported previously (15,16).

Briefly, siRNA dispersed in 5% glucose aqueous solution (500 nM

siRNA) was rapidly added to a lipid-ethanol solution containing

DOTAP:DOPE=1:1 (molar ratio) or DDAB:DOPE=1:1 (molar ratio) at a

charge ratio (+:-) of 4:1, followed by incubation for 5 min. The

charge ratio (+:-) of cationic lipids to siRNA was calculated as

the molar ratio of amines in cationic lipids to siRNA phosphate. To

prepare anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes, siRNA lipoplexes were

mixed with an aqueous solution of anionic polymers at charge ratios

(+:-) of cationic lipids to anionic polymers from 1:0.5 to 1:3, and

followed by incubation for 5 min. The charge ratio (+:-) of

cationic lipids to anionic polymers was calculated as the molar

ratio of the carboxylic acid of HA (one negative charge per

disaccharide unit), sulfate and carboxylic acid of CS (two negative

charges per disaccharide unit), and carboxylic acid of PGA (one

negative charge per glutamic acid).

The average particle size and ζ-potential of

lipoplexes were measured using a light-scattering photometer

(ELSZ-2000; Otsuka Electronics Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) at 25˚C

after diluting the dispersion to an appropriate volume with

water.

Cell culture

Human breast cancer MCF-7 cells stably expressing

firefly luciferase (MCF-7-Luc), which were constructed by

transfection of pcDNA3 plasmid containing firefly luciferase

(hLuc+) gene (GenBank no. AY535007.1) derived from

psiCHECK-2 vector (Promega Corporation), were provided by Dr. Kenji

Yamato (University of Tsukuba). Cells were cultured in RPMI-1640

medium (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corp.) supplemented with 10%

heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific,

Waltham, MA, USA) and 1.2 mg/ml G418 (geneticin) sulfate (Santa

Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) at 37˚C in a humidified

incubator with 5% CO2.

Gene silencing of anionic

polymer-coated lipoplexes

In brief, MCF-7-Luc cells were seeded in 6-well

culture plates the day before transfection. Lipoplexes with Luc or

Cont siRNA were prepared as described above, diluted in RPMI-1640

medium supplemented with 10% FBS at a 50 nM siRNA concentration,

and added to the cells for 48 h. Following transfection, luciferase

activity was measured as counts per second (cps)/µg protein using

the luciferase assay system (PicaGene MelioraStar-LT Luminescence

Reagent, Toyo B-Net Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and Pierce™ BCA

Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Luciferase activity

(%) was calculated relative to the luciferase activity (cps/µg

protein) of untreated cells, as reported previously (9).

Cellular association of siRNA

lipoplexes

Flow cytometry was performed to confirm the cellular

association of lipoplexes. In brief, MCF-7-Luc cells were seeded in

12-well culture plates the day before the experiment. Lipoplexes

with Cy5-siRNA were prepared as described above, diluted in

RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS at a 50 nM siRNA

concentration, and added to the cells. After incubation for 3 h,

the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4),

detached using TrypLE™ Express Enzyme (Gibco™, Thermo Fisher

Scientific), and suspended in PBS containing 0.1% bovine serum

albumin and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. The association

of Cy5-siRNA with cells was determined by examining the

fluorescence intensity using a BD FACSVerse™ flow cytometer (BD

Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), as reported previously (18).

Cytotoxicity of siRNA lipoplexes

Briefly, MCF-7-Luc cells were seeded in 96-well

culture plates the day before transfection. Lipoplexes with Cont

siRNA were prepared as described above, diluted in RPMI-1640 medium

supplemented with 10% FBS at a 50 nM siRNA concentration, and added

to the cells. After incubation for 24 h, cell viability was

measured using the WST-8 assay (Cell Counting Kit-8; Dojindo

Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan). Cell viability (%) was calculated

relative to the cell viability of untreated cells.

Animals

A total of 42 female BALB/c mice (8 weeks old) were

purchased from Sankyo Labo Service Corporation (Tokyo, Japan) and

maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions.

All animal experiments were conducted according to a

protocol reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and

Use Committee of Hoshi University (Permit No. P24-094).

Effect of anionic polymer-coating on

erythrocyte agglutination with siRNA lipoplexes

Agglutination of erythrocytes with siRNA lipoplexes

was determined as described previously (9). In brief, approximately 0.3 ml of blood

was collected in a single sampling from the jugular vein of one

female BALB/c mouse under inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane (5%

for induction and 2% for maintenance), and the mouse was euthanized

by cervical dislocation. Erythrocytes were separated by

centrifugation at 300 x g for 3 min and resuspended in PBS as a 2%

(v/v) suspension of erythrocyte. siRNA lipoplexes with 2 µg Cont

siRNA were mixed with the prepared erythrocyte suspension.

Subsequently, the mixture was placed on a glass plate and observed

by microscopy.

Biodistribution of anionic

polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes

siRNA lipoplexes with 10 µg Cy5-siRNA were

administered intravenously via the lateral tail vein of BALB/c mice

(n=1 per siRNA lipoplex). One hour post-injection, mice were

euthanized by cervical dislocation under inhalation anesthesia with

isoflurane (5% for induction and 2% for maintenance), and Cy5

fluorescence imaging of tissues was performed using a NightOWL

LB981 NC100 system (Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany),

as reported previously (19).

Images were analyzed using IndiGo2 software (version 2.0.1.0)

provided with the in vivo imaging system (Berthold

Technologies).

Measurement of TNF-α concentration in

mice

siRNA lipoplexes with 10 µg Cont siRNA were

administered intravenously via the lateral tail vein of BALB/c mice

(n=3 per siRNA lipoplex). Based on previous studies (20,21),

approximately 0.3 ml of blood was collected in a single sampling

from the jugular vein of a mouse under inhalation anesthesia with

isoflurane (5% for induction and 2% for maintenance) 2 h after

administration, after which the mouse was euthanized by cervical

dislocation. The blood was centrifuged at 1,000 x g for 10 min to

obtain serum. The concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-α

(TNF-α) in serum were determined by enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (LBIS mouse TNF-α ELISA kit, Fujifilm

Wako Shibayagi Corp. Cat # 634-44721), according to the

manufacturer s instructions.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance of differences between

the means of the two groups was determined using an unpaired t-test

with Welch s correction. For multiple-group comparisons,

statistical significance was determined using one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA), followed by Dunnett s multiple comparison

test. GraphPad Prism 6 (GraphPad Software Inc., Boston, MA, USA)

was used for the statistical analyses. Statistical significance was

set at P<0.05.

Results

Size and ζ-potential of anionic

polymer-coated lipoplexes prepared using the MEI method

Previously, cationic siRNA lipoplexes were

successfully prepared using the MEI method (15,16).

In this study, anionic polymers were electrostatically coated with

siRNA lipoplexes to prevent the agglutination of blood components,

such as erythrocytes. The size and ζ-potential of anionic

polymer-coated lipoplexes prepared using the MEI method are shown

in Table I. The charge ratio (+:-)

of cationic lipids to anionic polymers was examined over a range

from 1:0.5 to 1:3. A ratio of 1:2 was selected because not all

anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes exhibited negative surface charge

at ratios below 1:1, suggesting that the coating of lipoplexes may

be insufficient. The average size of siRNA lipoplex composed of

DOTAP/DOPE or DDAB/DOPE without polymer coating (LP-DOTAP and

LP-DDAB, respectively) was 106.1 and 75.1 nm, respectively. Anionic

polymer-coated lipoplexes showed comparable hydrodynamic size

(84.6-141.1 nm). LP-DOTAP and LP-DDAB had positive ζ-potentials

(52.8 and 36.6 mV, respectively). Each anionic polymer-coated

lipoplex exhibited a negative surface charge (from -14.4 to -45.1

mV of ζ-potential), indicating that cationic lipoplexes were

successfully coated with anionic polymers.

| Table IEffect of anionic polymer coating on

size and ζ-potential of small interfering RNA lipoplexes. |

Table I

Effect of anionic polymer coating on

size and ζ-potential of small interfering RNA lipoplexes.

| Lipoplexes | Lipid

formulation | Polymer

coatinga | Average

sizeb, nm | Polydispersity

index |

ζ-potentialb, mV |

|---|

| LP-DOTAP | DOTAP/DOPE=1:1

(mol:mol) | - | 106.1±2.9 | 0.29±0.01 | 52.8±4.6 |

| LP-DOTAP/HA-UL | | HA-UL | 115.7±0.3 | 0.11±0.02 | -18.0±1.4 |

| LP-DOTAP/HA-L | | HA-L | 140.0±15.3 | 0.26±0.05 | -24.1±1.4 |

| LP-DOTAP/HA-M | | HA-M | 84.6±1.7 | 0.26±0.00 | -26.2±1.7 |

| LP-DOTAP/HA-H | | HA-H | 99.7±5.7 | 0.21±0.00 | -26.3±7.0 |

| LP-DOTAP/CS | | CS | 114.9±2.0 | 0.23±0.01 | -41.4±1.9 |

| LP-DOTAP/PGA | | PGA | 126.9±23.7 | 0.24±0.07 | -45.1±1.7 |

| LP-DDAB | DDAB/DOPE=1:1

(mol:mol) | - | 75.1±5.9 | 0.20±0.06 | 36.6±8.8 |

| LP-DDAB/HA-UL | | HA-UL | 96.4±0.8 | 0.12±0.03 | -14.4±4.1 |

| LP-DDAB/HA-L | | HA-L | 133.3±16.9 | 0.15±0.04 | -26.1±0.3 |

| LP-DDAB/HA-M | | HA-M | 103.1±0.6 | 0.24±0.01 | -24.0±5.4 |

| LP-DDAB/HA-H | | HA-H | 120.8±0.6 | 0.21±0.02 | -27.8±0.6 |

| LP-DDAB/CS | | CS | 141.1±8.7 | 0.22±0.06 | -43.9±1.3 |

| LP-DDAB/PGA | | PGA | 115.0±7.5 | 0.23±0.04 | -43.2±4.2 |

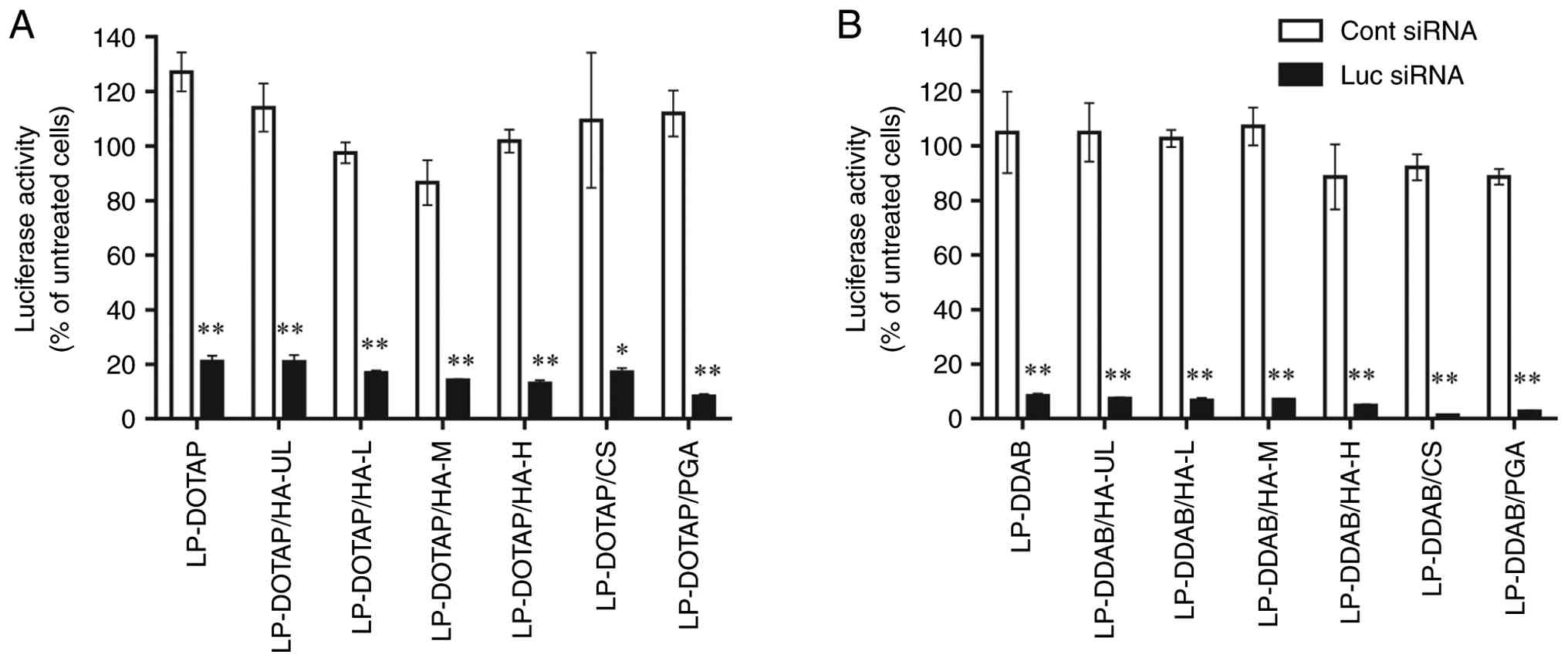

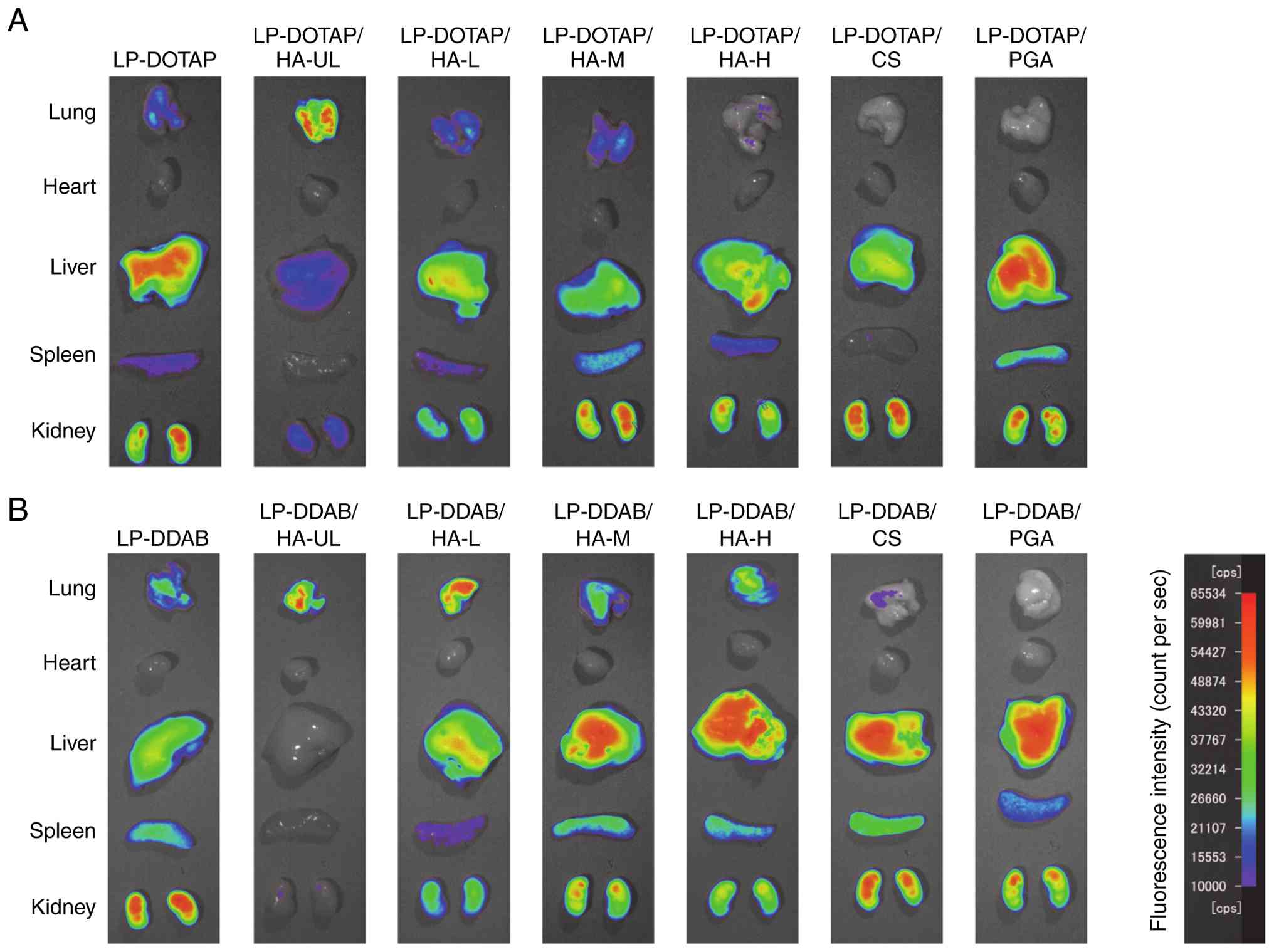

Gene knockdown effect and cellular

association of anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes

To determine the effect of the anionic polymer

coating on gene knockdown, MCF-7-Luc cells were incubated with

lipoplexes of Luc or Cont siRNA, and their luciferase activities

were evaluated (Fig. 1). Both

LP-DOTAP and LP-DDAB with Luc siRNA efficiently suppressed

luciferase activity in MCF-7-Luc cells. Anionic polymer-coated

lipoplexes also suppressed luciferase activity to the same level as

cationic lipoplexes.

| Figure 1Effect of anionic polymer coating of

siRNA lipoplexes on suppression of luciferase expression in

MCF-7-Luc cells. MCF-7-Luc cells were treated for 48 h with anionic

polymer-coated (A) LP-DOTAP or (B) LP-DDAB at a final Cont or Luc

siRNA concentration of 50 nM. Each value represents the mean ±

standard deviation (n=3). *P<0.05,

**P<0.01 compared with Cont siRNA. Cont, control; CS,

chondroitin sulfate; DDAB, dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide;

DOTAP, 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate

salt; HA, hyaluronan; HA-H, high-molecular-weight HA; HA-L,

low-molecular-weight HA; HA-M, medium-molecular-weight HA; HA-UL,

ultra-low-molecular-weight HA; Luc, luciferase; LP, lipoplex; PGA,

polyglutamic acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA. |

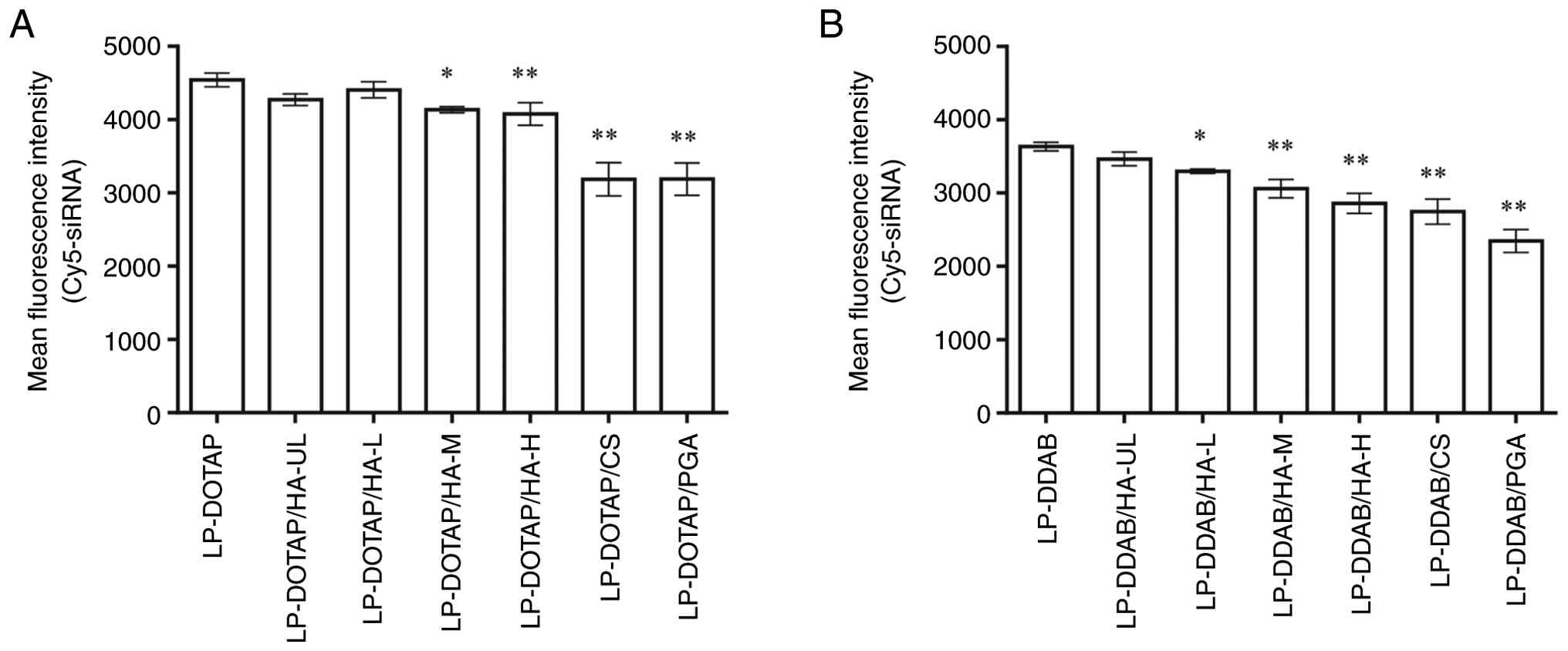

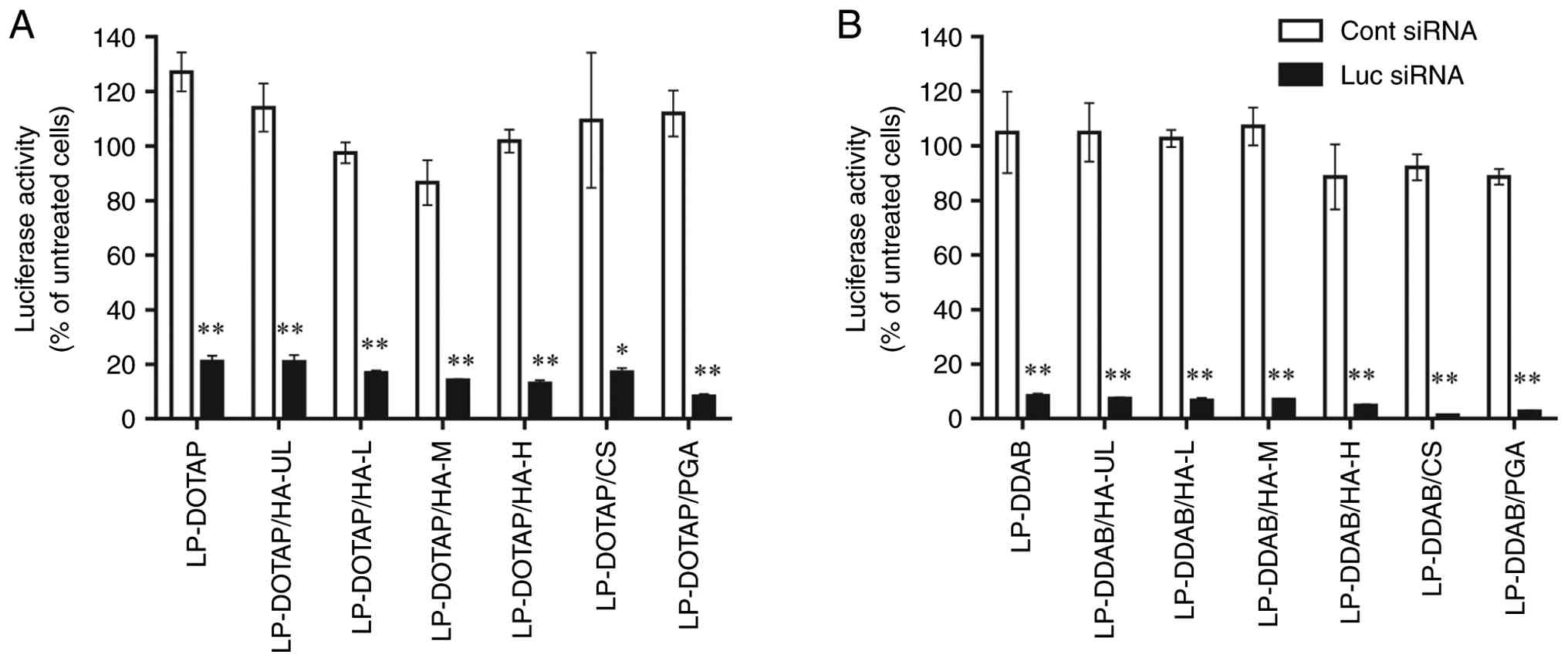

Next, we evaluated the cellular association of the

anionic polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes using flow cytometry

(Fig. 2). Representative flow

cytometry histograms are shown in Fig.

S1. The cationic lipoplexes, LP-DOTAP and LP-DDAB, exhibited a

higher cellular association than the anionic polymer-coated

lipoplexes. The mean fluorescence intensity of the HA-coated

lipoplexes decreased slightly as the molecular weight of HA

increased. CS and PGA-coated lipoplexes exhibited lower cellular

association than HA-coated lipoplexes. As shown in Table I, the large negative ζ-potential of

CS- and PGA-coated lipoplexes, compared with that of HA-coated

lipoplexes, may influence the reduced cellular association of

lipoplexes.

| Figure 2Cellular association of anionic

polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes. MCF-7-Luc cells were treated for 3

h with anionic polymer-coated (A) LP-DOTAP or (B) LP-DDAB at a

final Cy5-siRNA concentration of 50 nM. The association between the

siRNA lipoplexes and cells was determined based on Cy5 fluorescence

using flow cytometry. Each value represents the mean ± standard

deviation (n=3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01

compared with LP-DOTAP or LP-DDAB. CS, chondroitin sulfate; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; HA,

hyaluronan; HA-H, high-molecular-weight HA; HA-L,

low-molecular-weight HA; HA-M, medium-molecular-weight HA; HA-UL,

ultra-low-molecular-weight HA; LP, lipoplex; PGA, polyglutamic

acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA. |

Collectively, these results suggested that anionic

polymer-coating of siRNA lipoplexes decreased the cellular

association but did not affect gene knockdown. Anionic

polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes could effectively deliver siRNAs

into cells.

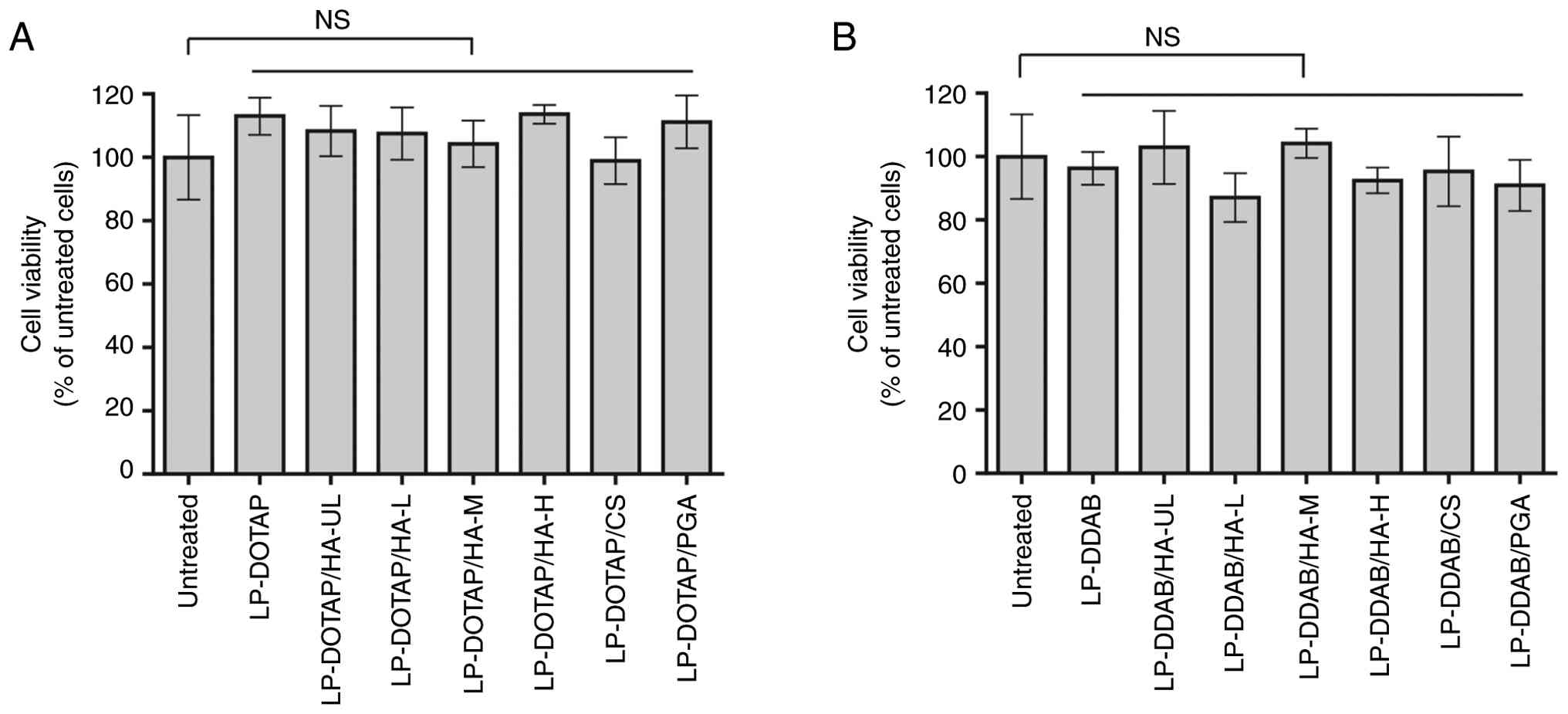

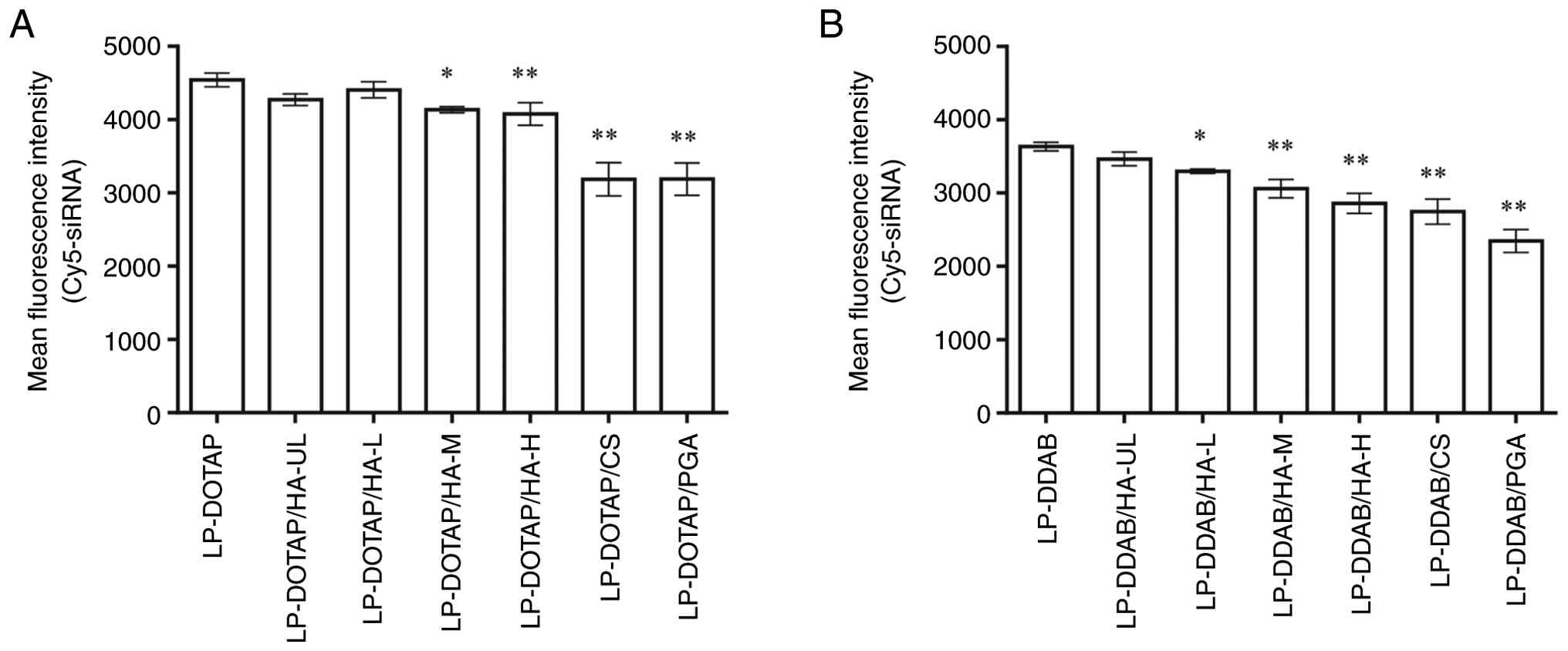

Cytotoxicity of anionic polymer-coated

lipoplexes

The effect of the anionic polymer coating on the

cytotoxicity of siRNA lipoplexes was examined (Fig. 3). The viability of MCF-7-Luc cells

incubated with all anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes exceeded 85%

of that of the untreated cells. No significant differences in cell

viability were observed compared with untreated cells. These

results suggested that the anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes

exhibited low cytotoxicity toward MCF-7-Luc cells.

| Figure 3Effect of anionic polymer-coated

siRNA lipoplexes on cell viability. MCF-7-Luc cells were treated

for 24 h with anionic polymer-coated (A) LP-DOTAP or (B) LP-DDAB at

a final control siRNA concentration of 50 nM. Each value represents

the mean ± standard deviation (n=5-6). CS, chondroitin sulfate;

DDAB, dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; HA,

hyaluronan; HA-H, high-molecular-weight HA; HA-L,

low-molecular-weight HA; HA-M, medium-molecular-weight HA; HA-UL,

ultra-low-molecular-weight HA; LP, lipoplex; NS, not significant;

PGA, polyglutamic acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA. |

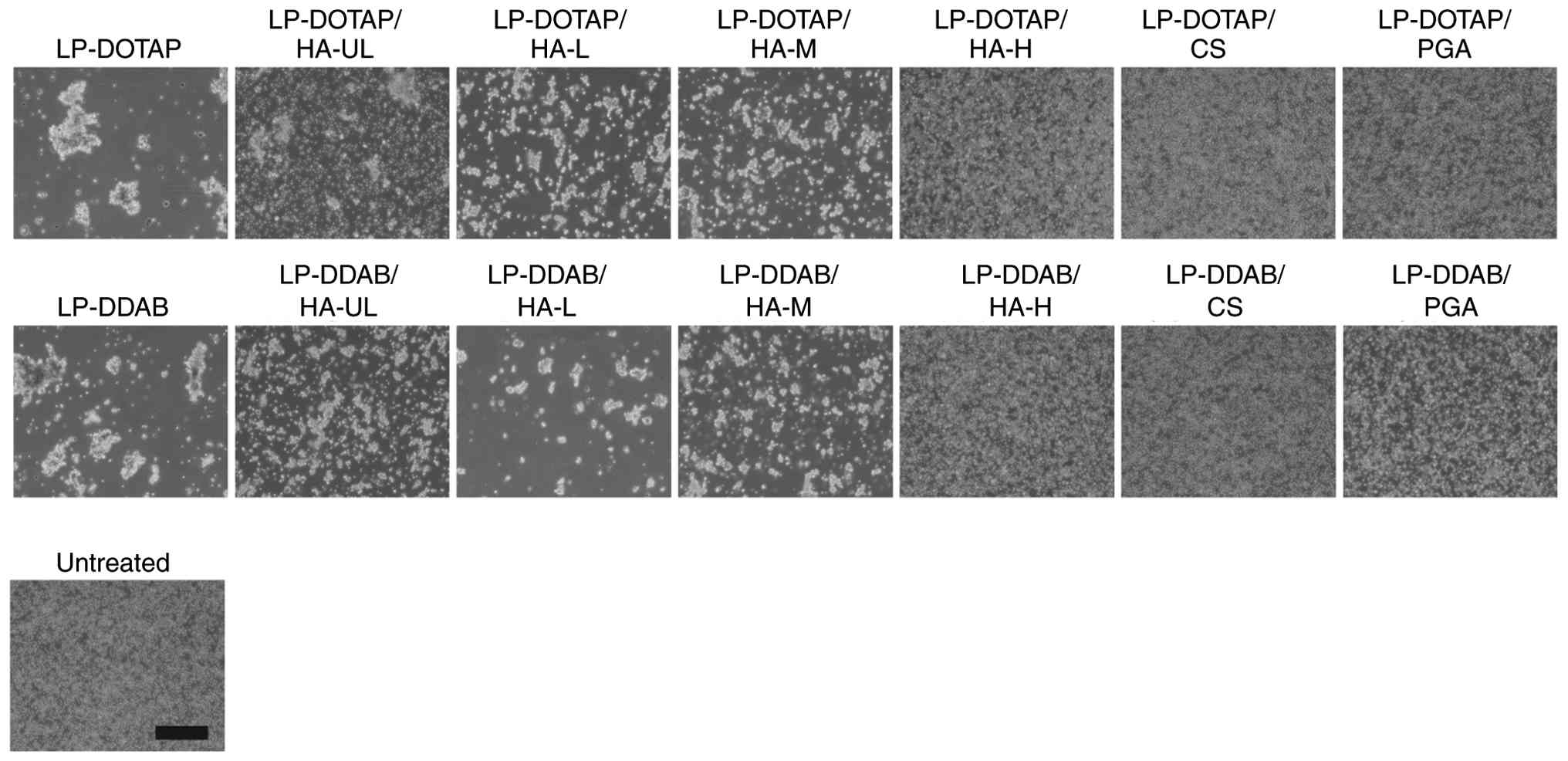

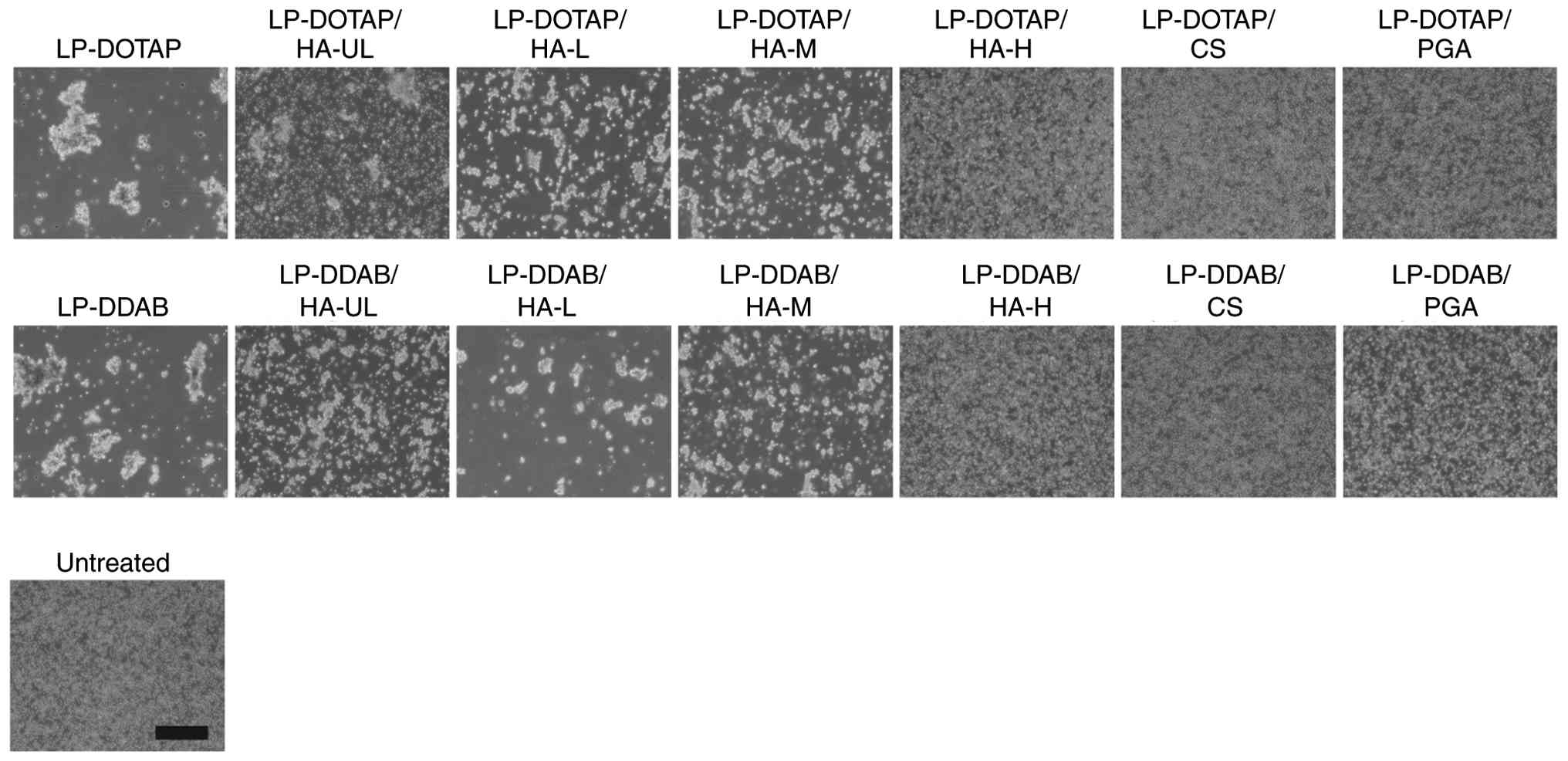

Erythrocyte agglutination with anionic

polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes

Because cationic lipoplexes have a positively

charged surface, they electrostatically interact with negatively

charged biological components, such as erythrocytes. We evaluated

whether the anionic polymer coating of lipoplexes could prevent

agglutination with erythrocytes (Fig.

4). Mixing cationic lipoplexes (LP-DOTAP or LP-DDAB) with

erythrocyte suspensions resulted in large aggregates. Small

aggregates were observed with HA-UL, HA-L, and HA-M-coated

lipoplexes. Conversely, LP-DOTAP/HA-H, LP-DOTAP/CS, LP-DOTAP/PGA,

LP-DDAB/HA-H, LP-DDAB/CS, and LP-DDAB/PGA did not induce

erythrocyte agglutination. These results suggested that HA-H-, CS-,

and PGA-coated lipoplexes of LP-DOTAP and LP-DDAB could prevent

erythrocyte agglutination.

| Figure 4Erythrocyte agglutination with

anionic polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes. Anionic polymer-coated

LP-DOTAP or LP-DDAB with 2 µg control siRNA were added to

erythrocyte suspensions, and agglutination was observed by

microscopy. Scale bar, 200 µm. CS, chondroitin sulfate; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; HA,

hyaluronan; HA-H, high-molecular-weight HA; HA-L,

low-molecular-weight HA; HA-M, medium-molecular-weight HA; HA-UL,

ultra-low-molecular-weight HA; LP, lipoplex; PGA, polyglutamic

acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA. |

Since anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes prevented

erythrocyte agglutination, they may have the potential to reduce

toxicity in vivo. To evaluate the inflammatory response of

lipoplexes, TNF-α concentrations in serum were determined (Fig. S2). Intravenous injection of LP-DDAB

caused a slight increase in serum TNF-α, whereas no elevation was

observed for LP-DDAB/HA-H or LP-DDAB/CS. Therefore, lipoplexes

coated with HA-H or CS are thought to have a higher safety

profile.

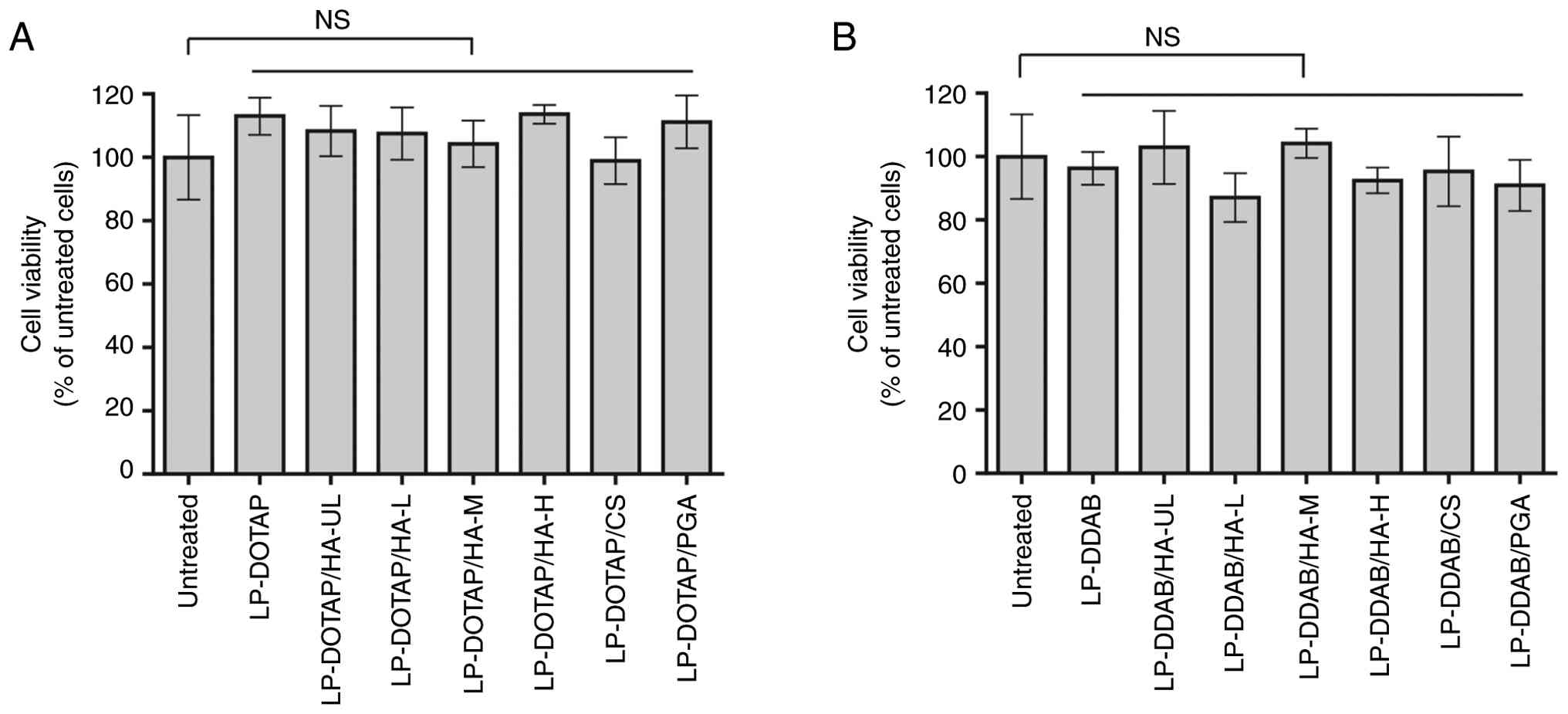

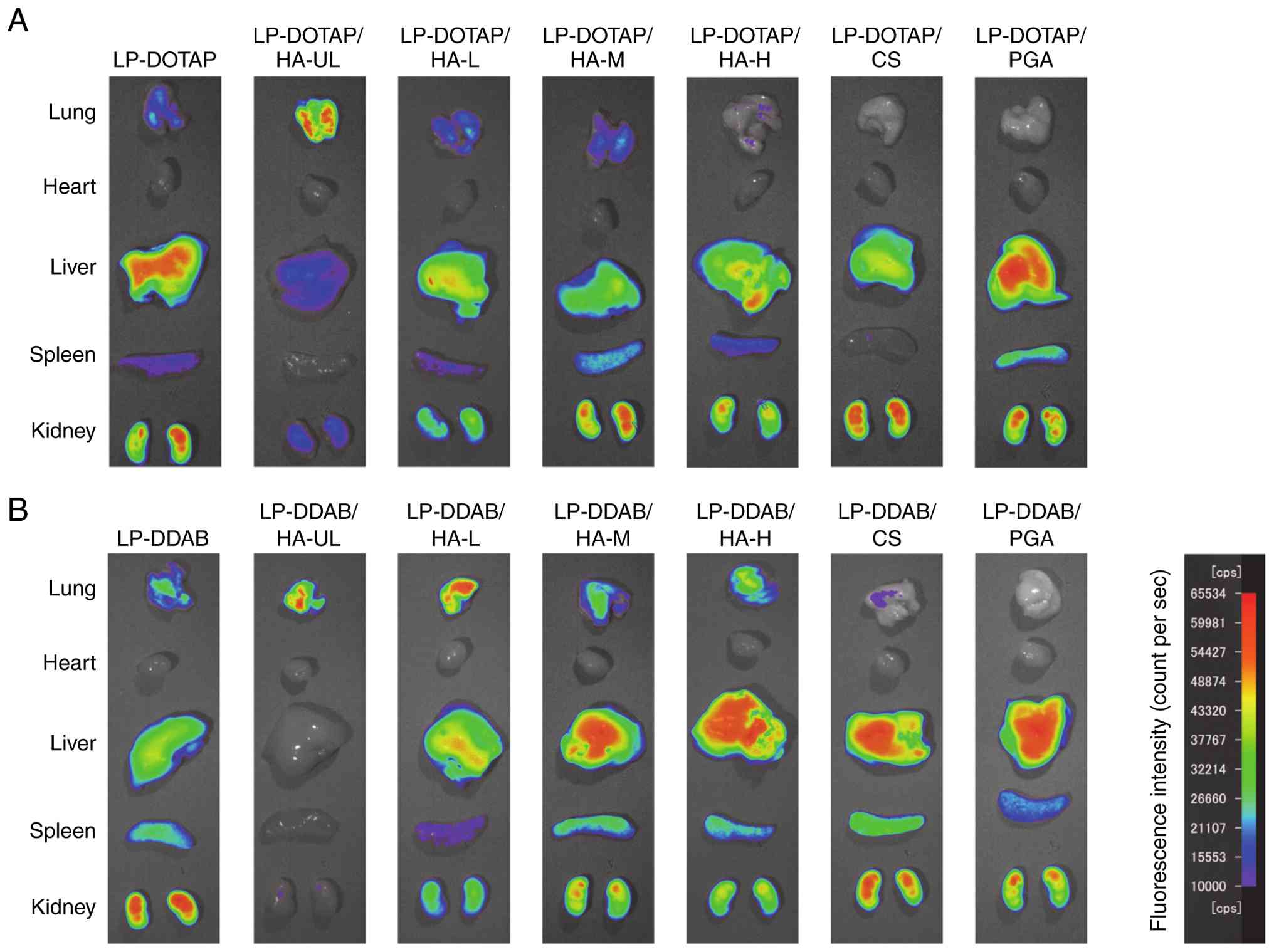

Biodistribution of anionic

polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes

Ex vivo imaging was performed to examine the

biodistribution of anionic polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes

(Fig. 5). LP-DOTAP and LP-DDAB were

distributed in the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys. As shown in

Fig. 5A, LP-DOTAP/HA-UL largely

accumulated in the lungs. The biodistribution of LP-DOTAP/HA-L and

LP-DOTAP/HA-M was similar to that of LP-DOTAP. The lung

distributions of LP-DOTAP/HA-H, LP-DOTAP/CS, and LP-DOTAP/PGA were

reduced. As shown in Fig. 5B,

LP-DDAB/HA-UL largely accumulated in the lungs, and other HA-coated

LP-DDAB were distributed in the lungs, liver, spleen, and kidneys.

The lung distribution of LP-DDAB/CS and LP-DDAB/PGA was lower than

that of LP-DDAB, whereas the liver distribution of LP-DDAB/CS and

LP-DDAB/PGA was higher than that of LP-DDAB.

| Figure 5Biodistribution of siRNA in mice 1 h

after intravenous injection of anionic polymer-coated siRNA

lipoplexes. Fluorescence imaging of the tissues was performed 1 h

after injection of mice with anionic polymer-coated (A) LP-DOTAP or

(B) LP-DDAB with 10 µg Cy5-siRNA. Images were obtained from one

mouse for each siRNA lipoplex. The fluorescence intensity was

illustrated using a color-coded scale (red is the maximum, purple

is the minimum). cps, count per sec; CS, chondroitin sulfate; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; HA,

hyaluronan; HA-H, high-molecular-weight HA; HA-L,

low-molecular-weight HA; HA-M, medium-molecular-weight HA; HA-UL,

ultra-low-molecular-weight HA; LP, lipoplex; PGA, polyglutamic

acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA. |

Discussion

In a recent report, our group demonstrated that the

MEI method was convenient for preparing lipoplexes of siRNA and

messenger RNA (mRNA) and that these lipoplexes could exert gene

transfection effects comparable to lipoplexes prepared using the

conventional thin lipid film hydration method (15,22).

In the MEI method, lipoplexes are prepared by mixing an RNA

solution with a lipid-ethanol solution. As shown in Table I, the average size of the lipoplexes

remained small (~100 nm), even after anionic polymer coating,

without mechanical shearing or sonication. Previously, siRNA

lipoplex prepared from cationic liposomes comprising DOTAP and

cholesterol was successfully coated with CS and PGA at a charge

ratio (+:-, cationic lipid:anionic polymer) of 1:1 and 1:1.5,

respectively (23). In the current

study, we established a charge ratio (+:-, cationic lipid:anionic

polymer) of 1:2 and generated lipoplexes with negative

ζ-potentials.

The gene knockdown effect of anionic polymer-coated

siRNA lipoplexes was comparable to that of cationic siRNA

lipoplexes, although the cellular association of anionic

polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes was lower than that of cationic

siRNA lipoplexes (Figs. 1 and

2). In our previous report, we

observed that anionic polymer coating of cationic siRNA lipoplexes

composed of DOTAP/cholesterol resulted in the disappearance of the

in vitro gene knockdown effect (23). The discrepancy in the gene knockdown

effect caused by anionic polymer coating is likely attributable to

the lipid composition of the lipoplexes, since cationic complexes

containing DOPE exhibited a greater gene knockdown effect despite

their low cellular association (24). Namely, the in vitro gene

knockdown effects of siRNA lipoplexes composed of DOTAP/DOPE and

DDAB/DOPE were higher than those of DOTAP/cholesterol and

DDAB/cholesterol, although cellular associations of siRNA

lipoplexes comprising DOTAP/DOPE and DDAB/DOPE were lower than

those of DOTAP/cholesterol and DDAB/cholesterol (24). Recently, Nabar et al

(25) reported that anionic polymer

coating on lipid nanoparticles can alter cellular interactions and

the intracellular trafficking of their cargo (mRNA and plasmid

DNA). Therefore, anionic polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes may

effectively deliver siRNA into cells; however, the intracellular

distribution of siRNA delivered by anionic polymer-coated

lipoplexes needs to be evaluated.

After intravenous injection of cationic lipoplexes,

agglutinates of cationic lipoplexes and erythrocytes are reportedly

entrapped in the highly extended lung capillary (6), which complicates delivery to organs

other than the lungs. PEG modification of the cationic lipoplex

surface decreases accumulation in the lung by avoiding association

with blood components, but PEG-modified lipoplexes lead to low

transfection efficiency (8-10).

To overcome this problem, the use of PEG-lipid derivatives with

cleavable linkers or releasable PEG derivatives has been explored

(9,26). In the current study, we found that

HA-H-, CS-, and PGA-coated lipoplexes prevented erythrocyte

agglutination and exhibited transfection efficiency comparable to

cationic lipoplexes (Figs. 1 and

4). These anionic polymers are

biodegradable, biocompatible, and exhibit low toxicity. Their

structures and charge density of polymers greatly influence the

biodistribution of lipoplexes coated with them. HA has one carboxyl

group per disaccharide unit, CS has a carboxyl group and a sulfate

group per disaccharide unit, and PGA has one carboxyl group per

glutamic acid unit. Because HA has a lower charge density than CS

or PGA, it is not expected to interact strongly with lipoplexes

(11); however, HA-H is likely to

interact more strongly and suppress erythrocyte agglutination.

These differences in charge density and structural features result

in distinct performance among HA-, CS-, and PGA-coated lipoplexes,

particularly in terms of coating strength, erythrocyte

agglutination, and biodistribution behavior. HA and CS are known

ligands for the cell surface receptor CD44, which is overexpressed

in numerous cancers (27,28). The usefulness of CD44 targeting by

these polymers has been reported previously (29,30).

Regarding HA, negatively charged lipoplexes were formed with all

molecular weights used for coating; however, the tendency to

aggregate with erythrocytes varied depending on the molecular

weight of HA (Fig. 4). Previous

reports suggested that molecular weight and grafting density of HA

on nanoparticles influenced the blood circulation time or receptor

recognition of nanoparticles (31-34).

Therefore, HA-H-coated lipoplexes are considered to have the

potential to reduce non-specific interactions, thereby improving

their stability in vivo while maintaining affinity for

target receptors. In the case of PGA, the tumor- or liver-targeting

properties have been reported previously (23,35-37).

It is important to evaluate the tumor- or liver-targeting efficacy

of anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes prepared using the MEI method

in the future.

Lipoplexes which form aggregates with erythrocytes

tend to accumulate in the lungs, the first capillary bed they pass

through (6,7). Aggregation with erythrocytes was

observed for both cationic lipoplexes (LP-DOTAP and LP-DDAB) and

those coated with HA-UL, HA-L or HA-M (Fig. 4), but not all lipoplexes accumulated

in the lungs (Fig. 5). This

discrepancy might be explained by differences in the stability of

the aggregates, which may induce dissociation of lipoplexes from

erythrocyte. It has been reported that the surface chemistry of

nanoparticles influenced the composition of the protein corona,

thereby affecting their organ tropism (38). Nanoparticles containing DOTAP have

been reported to form a protein corona enriched in vitronectin,

which binds to αvβ3 integrin highly expressed

in lung epithelium (38,39); however, in this study, LP-DOTAP

exhibited higher accumulation in the liver. It might be because the

lipoplex prepared in 5% glucose solution using the MEI method has

different morphology or surface properties. Further studies are

needed to clarify these mechanisms.

Anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes (especially CS- or

PGA-coated lipoplexes) altered the biodistribution of the siRNAs

(Fig. 5). However, the accumulation

of siRNA lipoplexes does not consistently correlate with the gene

knockdown effect in vivo (24,40).

Previous studies have shown that siRNA lipoplexes coated with CS or

PGA accumulate in the liver, but that only PGA-coated lipoplexes

can suppress the mRNA level of the hepatic target gene (23). Furthermore, it has been reported

that sequential intravenous administration of CS followed by

cationic lipoplexes results in siRNA accumulation in the liver and

subsequent suppression of the hepatic target gene (41). A limitation of the present study is

the absence of quantitative biodistribution data. Because

fluorescence imaging offers qualitative visualization rather than

reliable quantitative measurements (42), the biodistribution profiles of the

lipoplexes could not be discussed quantitatively. Further studies

are required to clarify the relationship between the

biodistribution of anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes and the in

vivo gene knockdown effects.

In conclusion, cationic siRNA lipoplexes were

prepared using the MEI method and successfully coated with anionic

polymers without a loss of transfection efficiency. HA-H-, CS-, and

PGA-coated lipoplexes prevented erythrocyte agglutination, while

decreased lung accumulation and increased liver accumulation were

observed after CS or PGA coating of siRNA lipoplexes. Although

further evaluation is necessary, anionic polymer-coated lipoplexes

prepared using the MEI method could enable siRNA delivery to the

liver or tumor tissues.

Supplementary Material

Representative flow cytometry

histograms. MCF-7-Luc cells were treated for 3 h with anionic

polymer-coated (A) LP-DOTAP or (B) LP-DDAB at a final Cy5-siRNA

concentration of 50 nM. The fluorescence intensity of gate P2 was

quantified and used for the analysis shown in Fig. 2. CS, chondroitin sulfate; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; HA,

hyaluronan; HA-H, high-molecular-weight HA; HA-L,

low-molecular-weight HA; HA-M, medium-molecular-weight HA; HA-UL,

ultra-low-molecular-weight HA; LP, lipoplex; PGA, polyglutamic

acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

TNF-α levels in serum after

intravenous injection of anionic polymer-coated siRNA lipoplexes.

The concentrations of TNF-α in serum were determined 2 h after

injection of HA-H, CS, or PGA-coated LP-DOTAP or LP-DDAB with 10

μg control siRNA to mice. Each value represents the mean ±

standard deviation of three individual mice (n=3 biological

replicates). CS, chondroitin sulfate; DDAB,

dimethyldioctadecylammonium bromide; DOTAP,

1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane methyl sulfate salt; HA-H,

high-molecular-weight hyaluronan; LP, lipoplex; PGA, polyglutamic

acid; siRNA, small interfering RNA.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Min Tang, Ms. Yui

Kikuchi, Mr. Rento Suzuki, Ms. Sumire Fukushige and Mr. Kohei Miura

(Department of Molecular Pharmaceutics, Hoshi University,

Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan) for their assistance with experiments.

Funding

Funding: No funding was received.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors contributions

KK and YH conceived and designed the experiments. KK

conducted the investigation, curated data, performed formal

analysis, prepared the original draft, and wrote, reviewed and

edited the manuscript. KK and YH confirm the authenticity of all

the raw data. All authors have read and approved the final version

of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

The present study was approved by the Institutional

Animal Care and Use Committee of Hoshi University (approval no.

P24-094; Shinagawa, Tokyo, Japan).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA,

Driver SE and Mello CC: Potent and specific genetic interference by

double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 391:806–811.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Davis ME, Zuckerman JE, Choi CHJ, Seligson

D, Tolcher A, Alabi CA, Yen Y, Heidel JD and Ribas A: Evidence of

RNAi in humans from systemically administered siRNA via targeted

nanoparticles. Nature. 464:1067–1070. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Zatsepin TS, Kotelevtsev YV and

Koteliansky V: Lipid nanoparticles for targeted siRNA

delivery-going from bench to bedside. Int J Nanomedicine.

11:3077–3086. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Yan Y, Liu XY, Lu A, Wang XY, Jiang LX and

Wang JC: Non-viral vectors for RNA delivery. J Control Release.

342:241–279. 2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Zhang S, Zhi D and Huang L: Lipid-based

vectors for siRNA delivery. J Drug Target. 20:724–735.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Simberg D, Weisman S, Talmon Y, Faerman A,

Shoshani T and Barenholz Y: The role of organ vascularization and

lipoplex-serum initial contact in intravenous murine lipofection. J

Biol Chem. 278:39858–39865. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Eliyahu H, Servel N, Domb AJ and Barenholz

Y: Lipoplex-induced hemagglutination: Potential involvement in

intravenous gene delivery. Gene Ther. 9:850–858. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Buyens K, De Smedt SC, Braeckmans K,

Demeester J, Peeters L, van Grunsven LA, de Mollerat du Jeu X,

Sawant R, Torchilin V, Farkasova K, et al: Liposome based systems

for systemic siRNA delivery: Stability in blood sets the

requirements for optimal carrier design. J Control Release.

158:362–370. 2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Hattori Y, Tamaki K, Sakasai S, Ozaki KI

and Onishi H: Effects of PEG anchors in PEGylated siRNA lipoplexes

on in vitro gene-silencing effects and siRNA biodistribution

in mice. Mol Med Rep. 22:4183–4196. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Hatakeyama H, Akita H and Harashima H: A

multifunctional envelope type nano device (MEND) for gene delivery

to tumours based on the EPR effect: A strategy for overcoming the

PEG dilemma. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 63:152–160. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Hattori Y, Yamasaku H and Maitani Y:

Anionic polymer-coated lipoplex for safe gene delivery into tumor

by systemic injection. J Drug Target. 21:639–647. 2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Fukushige K, Tagami T and Ozeki T: The

offset effect of a hyaluronic acid coating to cationic carriers

containing siRNA: Alleviated cytotoxicity and retained gene

silencing in vitro. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 39:435–441. 2017.

|

|

13

|

Qian Y, Liang X, Yang J, Zhao C, Nie W,

Liu L, Yi T, Jiang Y, Geng J, Zhao X and Wei X: Hyaluronan reduces

cationic liposome-induced toxicity and enhances the antitumor

effect of targeted gene delivery in mice. ACS Appl Mater

Interfaces. 10:32006–32016. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Hattori Y, Kurihara A and Shinkawa M:

Assessment of anionic siRNA lipoplexes prepared via modified

ethanol injection for tumor cell delivery. Biomed Rep.

24(12)2026.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hattori Y, Saito H, Nakamura K, Yamanaka

A, Tang M and Ozaki KI: In vitro and in vivo transfections using

siRNA lipoplexes prepared by mixing siRNAs with a lipid-ethanol

solution. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 75(103635)2022.

|

|

16

|

Hattori Y, Tang M, Suzuki H, Hattori A,

Endo S, Ishii A, Aoki A, Ezaki M and Sakai H: Optimization of

transfection into cultured cells with siRNA lipoplexes prepared

using a modified ethanol injection method. J Drug Deliv Sci

Technol. 99(106000)2024.

|

|

17

|

Hattori Y, Tang M, Aoki A, Ezaki M, Sakai

H and Ozaki KI: Effect of the combination of cationic lipid and

phospholipid on gene-knockdown using siRNA lipoplexes in breast

tumor cells and mouse lungs. Mol Med Rep. 28(180)2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Hattori Y and Shimizu R: Effective mRNA

transfection of tumor cells using cationic triacyl lipid-based mRNA

lipoplexes. Biomed Rep. 22(25)2025.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Hattori Y, Tamaki K, Ozaki KI, Kawano K

and Onishi H: Optimized combination of cationic lipids and neutral

helper lipids in cationic liposomes for siRNA delivery into the

lung by intravenous injection of siRNA lipoplexes. J Drug Deliv Sci

Technol. 52:1042–1050. 2019.

|

|

20

|

Whitmore M, Li S and Huang L: LPD

lipopolyplex initiates a potent cytokine response and inhibits

tumor growth. Gene Ther. 6:1867–1875. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Hattori Y, Arai S, Kikuchi T, Ozaki KI,

Kawano K and Yonemochi E: Therapeutic effect for liver-metastasized

tumor by sequential intravenous injection of anionic polymer and

cationic lipoplex of siRNA. J Drug Target. 24:309–317.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

22

|

Hattori Y, Tang M, Sato J, Tsuiji M and

Kawano K: Evaluation of mRNA lipoplexes prepared using modified

ethanol injection method as a tumour vaccine. J Drug Target.

32:1267–1277. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Hattori Y, Nakamura A, Arai S, Nishigaki

M, Ohkura H, Kawano K, Maitani Y and Yonemochi E: In vivo siRNA

delivery system for targeting to the liver by poly-l-glutamic

acid-coated lipoplex. Results Pharm Sci. 4:1–7. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

24

|

Hattori Y, Nakamura A, Arai S, Kawano K,

Maitani Y and Yonemochi E: siRNA delivery to lung-metastasized

tumor by systemic injection with cationic liposomes. J Liposome

Res. 25:279–286. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Nabar N, Dacoba TG, Covarrubias G,

Romero-Cruz D and Hammond PT: Electrostatic adsorption of

polyanions onto lipid nanoparticles controls uptake, trafficking,

and transfection of RNA and DNA therapies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

121(e2307809121)2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Wang T, Upponi JR and Torchilin VP: Design

of multifunctional non-viral gene vectors to overcome physiological

barriers: Dilemmas and strategies. Int J Nanomedicine. 427:3–20.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Lesley J, Hascall VC, Tammi M and Hyman R:

Hyaluronan binding by cell surface CD44. J Biol Chem.

275:26967–26975. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Sironen RK, Tammi M, Tammi R, Auvinen PK,

Anttila M and Kosma VM: Hyaluronan in human malignancies. Exp Cell

Res. 317:383–391. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Lin WJ and Lee WC: Polysaccharide-modified

nanoparticles with intelligent CD44 receptor targeting ability for

gene delivery. Int J Nanomedicine. 13:3989–4002. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Dosio F, Arpicco S, Stella B and Fattal E:

Hyaluronic acid for anticancer drug and nucleic acid delivery. Adv

Drug Deliv Rev. 97:204–236. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Peer D and Margalit R: Tumor-targeted

hyaluronan nanoliposomes increase the antitumor activity of

liposomal Doxorubicin in syngeneic and human xenograft mouse tumor

models. Neoplasia. 6:343–353. 2004.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Zhang Q, Deng C, Fu Y, Sun X, Gong T and

Zhang Z: Repeated administration of hyaluronic acid coated

liposomes with improved pharmacokinetics and reduced immune

response. Mol Pharm. 13:1800–1808. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Mizrahy S, Raz SR, Hasgaard M, Liu H,

Soffer-Tsur N, Cohen K, Dvash R, Landsman-Milo D, Bremer MG,

Moghimi SM and Peer D: Hyaluronan-coated nanoparticles: The

influence of the molecular weight on CD44-hyaluronan interactions

and on the immune response. J Control Release. 156:231–238.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Qhattal HS and Liu X: Characterization of

CD44-mediated cancer cell uptake and intracellular distribution of

hyaluronan-grafted liposomes. Mol Pharm. 8:1233–1246.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Peng SF, Tseng MT, Ho YC, Wei MC, Liao ZX

and Sung HW: Mechanisms of cellular uptake and intracellular

trafficking with chitosan/DNA/poly(γ-glutamic acid) complexes as a

gene delivery vector. Biomaterials. 32:239–248. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Kurosaki T, Ueda Y, Kato Y, Nakashima M,

Kitahara T, Sasaki H and Kodama Y: Effect of a novel siRNA delivery

system, siRNA ternary complex, on melanoma lung metastasis. J Drug

Target. 32:848–854. 2024.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Hattori Y, Arai S, Okamoto R, Hamada M,

Kawano K and Yonemochi E: Sequential intravenous injection of

anionic polymer and cationic lipoplex of siRNA could effectively

deliver siRNA to the liver. Int J Pharm. 476:289–298.

2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Dilliard SA, Cheng Q and Siegwart DJ: On

the mechanism of tissue-specific mRNA delivery by selective organ

targeting nanoparticles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA.

118(e2109256118)2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Dilliard SA, Sun Y, Brown MO, Sung YC,

Chatterjee S, Farbiak L, Vaidya A, Lian X, Wang X, Lemoff A and

Siegwart DJ: The interplay of quaternary ammonium lipid structure

and protein corona on lung-specific mRNA delivery by selective

organ targeting (SORT) nanoparticles. J Control Release.

361:361–372. 2023.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Hattori Y, Nakamura M, Takeuchi N, Tamaki

K, Ozaki KI and Onishi H: Effect of cationic lipid type in

PEGylated liposomes on siRNA delivery following the intravenous

injection of siRNA lipoplexes. World Acad Sci J. 1:74–85. 2019.

|

|

41

|

Hattori Y, Yoshiike Y, Kikuchi T, Yamamoto

N, Ozaki KI and Onishi H: Evaluation of the injection route of an

anionic polymer for small interfering RNA delivery into the liver

by sequential injection of anionic polymer and cationic lipoplex of

small interfering RNA. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 35:40–49.

2016.

|

|

42

|

Simonsen JB and Kromann EB: Pitfalls and

opportunities in quantitative fluorescence-based nanomedicine

studies-A commentary. J Control Release. 335:660–667.

2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|