Introduction

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pleiotropic cytokine

integral to immune regulation, inflammatory signaling, cellular

proliferation, and survival (1,2). Upon

binding to its receptor complex, which includes gp130, IL-6

activates the Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling pathway, resulting in the

transcription of a wide array of target genes implicated in

inflammatory and oncogenic processes (3-7).

The activation of STAT3 is tightly regulated by phosphorylation at

two key residues, Tyrosine705 and Serine727. Specifically,

phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705 is a critical event that

promotes STAT3 dimerization, nuclear translocation, and subsequent

transcriptional activation of downstream genes such as suppressor

of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3) and C-reactive protein (CRP), which

serve as important markers of IL-6-mediated responses. Aberrant or

sustained activation of the IL-6/STAT3 signaling axis has been

strongly associated with the pathogenesis of various chronic

inflammatory diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and

inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as well as malignancies such as

hepatocellular carcinoma, thus underscoring its significance as a

therapeutic target (8-10).

Given the pivotal role of IL-6/STAT3 signaling in

chronic inflammation and tumorigenesis, considerable research has

focused on identifying pharmacological inhibitors that target this

pathway. Natural products, particularly those derived from

medicinal plants, have emerged as valuable sources of bioactive

compounds capable of modulating cytokine signaling. Curcuma

longa L. (Zingiberaceae), commonly known as turmeric, has long

been used in traditional Asian medicine and is well known for its

immunoregulatory, antioxidant, antihepatotoxic,

hypocholesterolemic, and anticancer properties. These effects are

primarily attributed to curcuminoids such as curcumin,

demethoxycurcumin, and bisdemethoxycurcumin, which are abundant in

the rhizome (11-16).

While the pharmacological activities of turmeric rhizome have been

extensively investigated, the aerial parts of the plant, including

the leaves, remain largely underexplored, despite reports of their

antioxidant, antibacterial, and immuno-regulatory effects (17,18).

Recent studies have reported that C. longa

leaf extracts (CL-E) modulate inflammatory signaling and host

immunity. Phytochemical analyses of the aerial parts have

identified flavonoids, tannins, and polyphenols that underlie the

documented antioxidant and immunoregulatory activities (19-21).

Nevertheless, the molecular basis by which these constituents

affect cytokine-driven pathways remains unclear. In particular, it

is unknown whether, and how, CL-E influences the IL-6/STAT3

pathway-a central regulator of acute-phase responses, inflammation,

and tumorigenic signaling. Since STAT3 activation depends on

site-specific phosphorylation at Tyr705 and Ser727 that governs

dimerization, nuclear import, and transcriptional output, defining

the impact of CL-E on these regulatory nodes addresses this key

mechanistic gap.

In light of the ongoing need for novel natural

inhibitors of the IL-6/STAT3 axis, we utilized a STAT3 luciferase

reporter system to evaluate the effects of the ethyl acetate

fraction of C. longa leaves on STAT3 activation, including

downstream events such as STAT3 phosphorylation, nuclear

translocation, and the expression of IL-6-responsive genes such as

SOCS3 and CRP. To further elucidate the upstream regulatory

mechanisms, we investigated the involvement of the MEK-ERK pathway

employing specific pharmacological inhibitors, thereby

characterizing the signaling cascade implicated in the CL-E

mediated inhibitory effects on STAT3. Accumulating evidence

suggests that protein kinase C (PKC) can activate the Raf-MEK-ERK

cascade and that ERK-driven Ser727 phosphorylation can modulate- or

in some contexts antagonize-Tyr705-dependent STAT3 activation

(9). We therefore hypothesized that

the ethyl acetate fraction of C. longa leaves (CL-E)

attenuates IL-6/STAT3 signaling by engaging a PKC-MEK/ERK axis and

shifting the Tyr705/Ser727 phosphorylation balance.

Collectively, our findings provide novel insights

into the molecular mechanisms by which CL-E modulates IL-6/STAT3

signaling and suggest its potential as a natural therapeutic agent

for inflammation-related disorders.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals

Recombinant human IL-6 was procured from R&D

Systems. Mouse anti-phospho STAT3 (Tyr705) IgG was obtained from

Calbiochem. Rabbit anti-phospho Stat3 (Ser727) IgG, anti-total

STAT3 IgG, anti-phospho ERK1/2 IgG, anti-total ERK1/2 IgG, β-actin

and secondary antibody were purchased from Cell Signaling

Technology. All other reagents, including genistein, U0126, and

bisindolylmaleimide II, were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich.

Preparation of crude extracts

Aerial parts of C. longa L. were provided by

the Rural Development Administration (RDA) of Korea. The plant

materials were extracted using methanol solvents (5 lx2 times).

Methanol extracts (1 g) were suspended in 50 ml of distilled water

and successively partitioned with ethyl acetate (100 ml x 3),

yielding the ethyl acetate-soluble fraction (227 mg, CL-E).

Cell line and cell culture

Human hepatoma Hep3B cells were obtained from the

American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; no. HB-8064) and were

maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50

U/ml penicillin, and 50 mg/ml streptomycin at 37˚C in a humidified

5% CO2 incubator. All cell culture reagents were

obtained from GibcoBRL (Life Technologies).

Establishment of stable cell line

expressing pStat3-Luc

As previously described, a stable Hep3B cell line

expressing a STAT3-responsive luciferase reporter (pStat3-Luc) was

established (22). Briefly, Hep3B

cells were co-transfected with pStat3-Luc (containing a

STAT3-binding site) and pcDNA3.1(+) carrying a hygromycin

resistance gene (Clontech Laboratories) using Lipofectamine Plus

(Invitrogen). After 48 h, cells were selected with 100 µg/ml

hygromycin, and stable clones were expanded. Luciferase expression

was confirmed by luciferase assay.

Luciferase assay

Stable pStat3-Luc-expressing Hep3B cells were seeded

in 96-well plates at a density of 2x104 cells/well.

After 24 h, the cells were serum-starved for 12 h and subsequently

treated with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 12 h in the presence or absence of

test compounds. Luciferase activity was quantified using a

commercial kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer's

instructions.

Cell viability

Hep3B cells were seeded at a density of

1x104 cells/well and incubated for 24 h. The medium was

then replaced with serum-free DMEM containing varying

concentrations of test samples. Following 48 h of treatment, MTT

solution (0.5 mg/ml) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h.

Subsequently, 100 µl of DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan

crystals. Absorbance was measured at 540 nm using a microplate

reader, and cell viability was calculated relative to the untreated

control.

Western blot analysis

Total protein lysates were prepared and analyzed

using Western blot as previously described (22). Briefly, Cells were lysed in Cell

Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling Technology) supplemented with a

protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo Scientific).

Protein concentrations were determined using the DC protein assay

(Bio-Rad). Equal amount of whole cell lysates (20-40 µg per lane)

were separated by SDS-PAGE on 4-12% gradient gels and transferred

to PVDF membranes (Amersham Bioscience). Membranes were blocked

with 5% (w/v) non-fat dry milk in TBS-T (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150

mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20) for 1 h at room temperature, then incubated

overnight at 4˚C with primary antibodies against p-STAT3 (Tyr705;

1:1,000; CST #9145), p-STAT3 (Ser727; 1:1,000; CST #9134), t-STAT3

(1:1,000; CST #4904), p-ERK (1:1,000; CST #4370), t-ERK (1:1,000;

CST #4695) and β-actin (1:2,000; CST #4967). After washing in

TBS-T, membranes were incubated with the appropriate horseradish

peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000; CST #7074) for

30 min. Signals were developed using an enhanced chemiluminescence

(ECL) substrate (West-ZOL Plus kit; iNtRON Biotechnology) and

recorded on X-ray film (Eastman Kodak Co.). All blots were

reproduced in triplicate experiments.

Immunocytochemistry for STAT3

localization

Hep3B cells were cultured on 8-well Nunc Lab-Tek

chamber slides and treated with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 4 h, in the

presence or absence of CL-E. Cells were fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde for 30 min, permeabilized with 100% cold methanol

for 5 min, and blocked with 5% BSA for 30 min. Cells were incubated

overnight at 4˚C with rabbit anti-STAT3 antibody (1:200), followed

by FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000) for 1 h. Slides

were mounted using SlowFade Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen), and

fluorescence images were acquired using a Leica DM5000B microscope

(Leica).

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and

real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from Hep3B cells using the

RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (Qiagen), including on-column DNase

treatment. RNA concentration and quality were assessed using an

Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). cDNA was

synthesized using the TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents Kit

(Applied Biosystems), and real-time PCR was performed using a

StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan

primers for human CRP (Hs04183452_g1) and SOCS3 (Hs02330328_s1)

were obtained from Applied Biosystems. 18S rRNA (Hs99999901_s1) was

used as an endogenous control. Data were analyzed using the

2-ΔΔCT method, and gene expression levels were presented

relative to those of untreated controls.

Data analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data

are presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical

analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad software

Inc.). One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test was used,

and differences were considered statistically significant at

P<0.05, P<0.01, and P<0.001.

Results

CL-E inhibits IL-6-induced STAT3

transcriptional activity without cytotoxicity

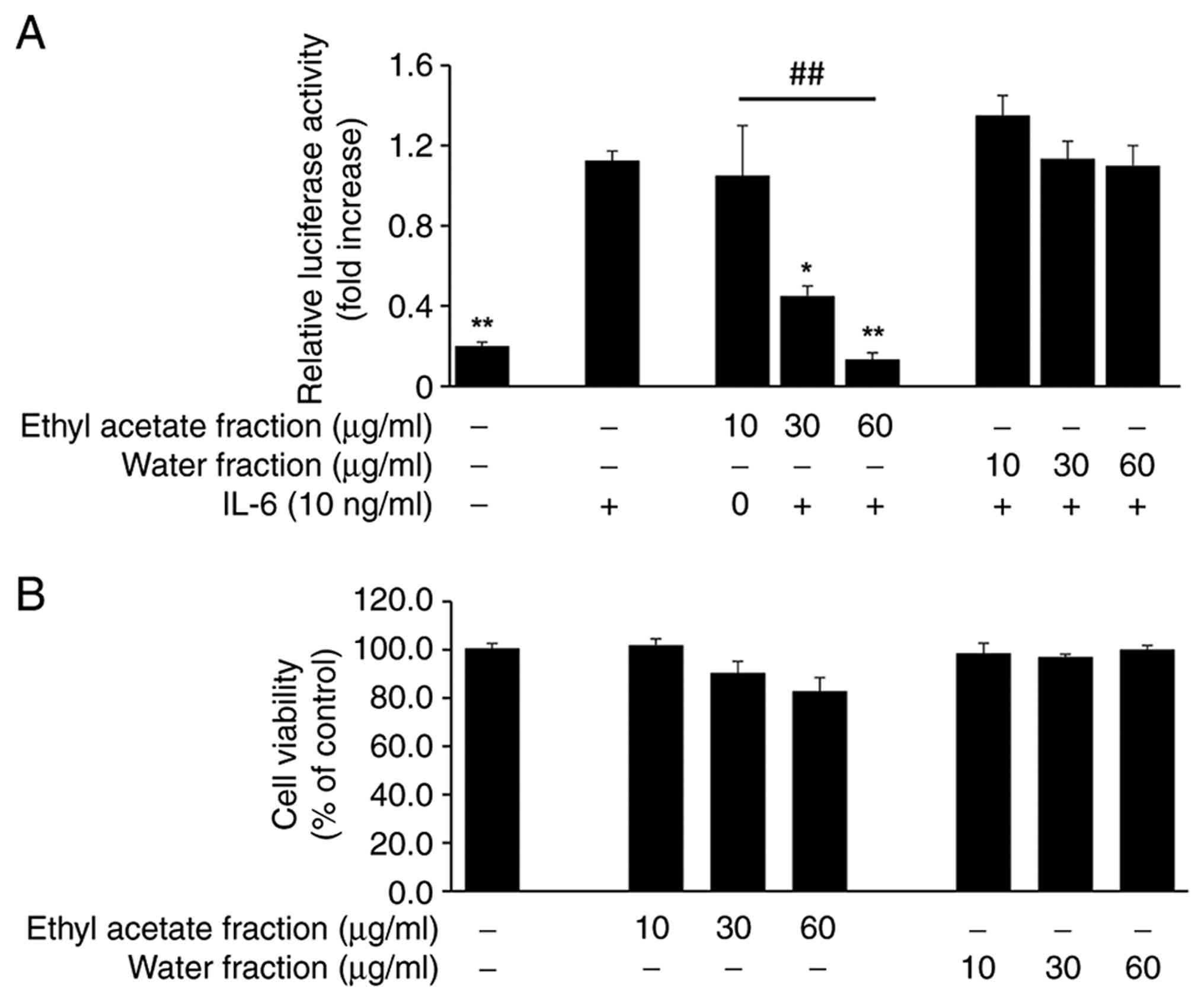

To explore natural products that inhibit

IL-6-induced activation, a luciferase reporter assay was initially

conducted using Hep3B cells stably transfected with a

STAT3-responsive luciferase construct (pSTAT3-Luc) for screening

purposes. During preliminary screening, methanol extracts of C.

longa L leaves were found to suppress IL-6-stimulated

STAT3-dependent activity (data not shown). Based on this

observation, the methanol extract was subsequently partitioned into

an ethyl acetate fraction (CL-E) and an aqueous fraction to isolate

the active component. Both fractions were evaluated for their

ability to inhibit IL-6-induced STAT3-dependent transcriptional

activity. Cells were stimulated with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for 12 h in

the presence or absence of each fraction. As illustrated in

Fig. 1A, CL-E significantly

inhibited IL-6-induced luciferase activity in a dose-dependent

manner (IC50: 33.9±3.7 µg/ml), with a significant

difference between the 10 and 60 µg/ml concentrations, whereas the

aqueous fraction exhibited no significant inhibitory effect.

Importantly, MTT assay results demonstrated that CL-E treatment up

to 60 µg/ml did not induce cytotoxicity under the experimental

conditions (Fig. 1B), indicating

that the observed inhibition of STAT3 activity was not attributable

to reduced cell viability.

CL-E suppresses STAT3 Tyr705

phosphorylation and nuclear translocation in IL-6-stimulated

cells

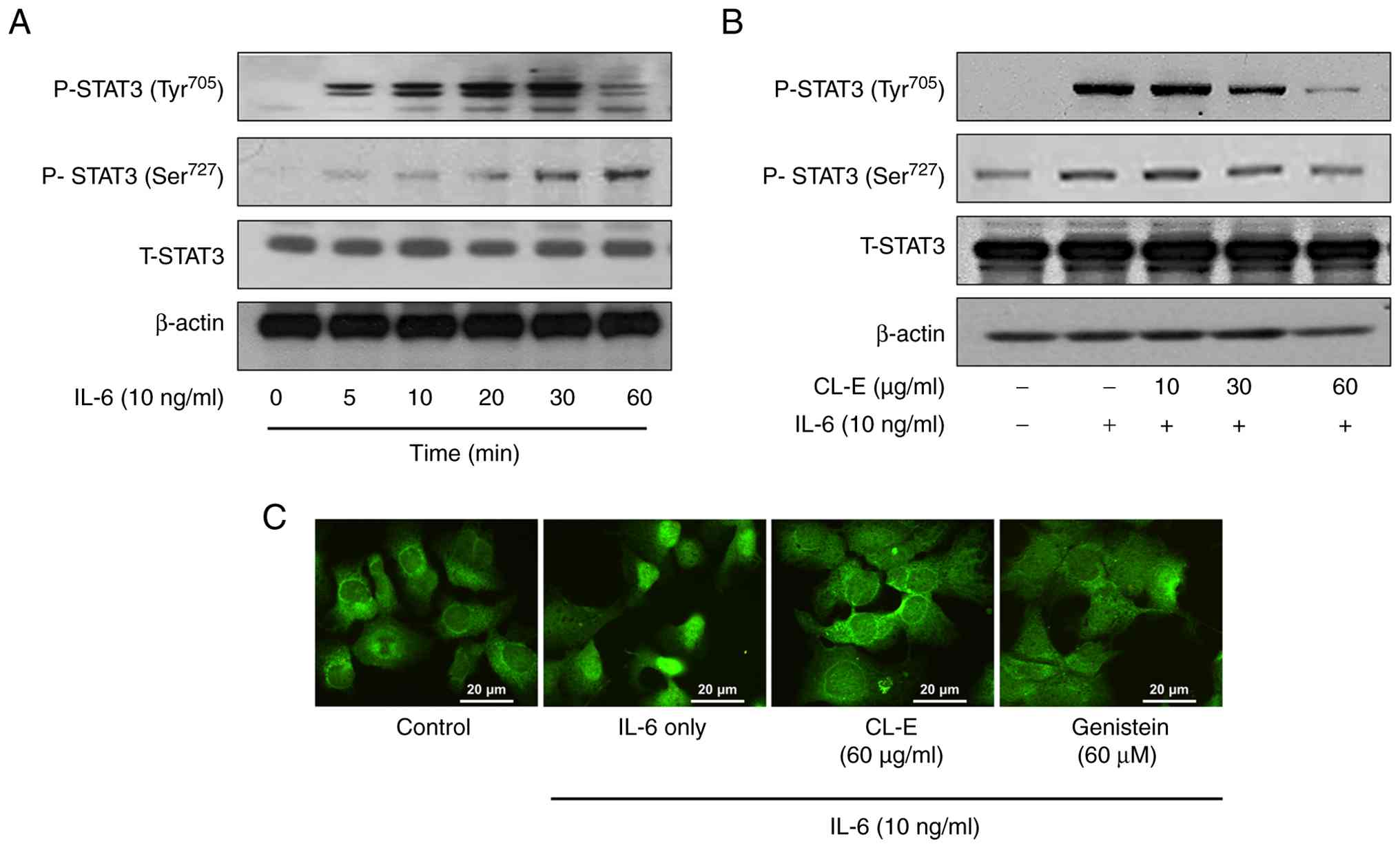

To elucidate the mechanism underlying the inhibitory

effect of CL-E on STAT3 transcriptional activity, we investigated

its impact on STAT3 phosphorylation at two key regulatory residues,

Tyr705 and Ser727, which are essential for STAT3 activation and

function. Initially, a time-course analysis of STAT3

phosphorylation following IL-6 stimulation was conducted. Hep3B

cells were treated with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for varying durations (0,

5, 10, 20, 30, and 60 min), and cell lysates underwent Western blot

analysis using phospho-specific antibodies against STAT3

phosphorylated at Tyr705 and Ser727, as well as total STAT3. As

depicted in Fig. 2A, IL-6 treatment

resulted in rapid, robust phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705,

peaking at approximately 20-30 min and declining thereafter. STAT3

phosphorylation at Ser727 also increased in response to IL-6 but

appeared later and with less intensity compared to that at Tyr705.

These results confirm activation of the canonical IL-6/STAT3

signaling pathway in Hep3B cells. To determine whether CL-E

treatment affects IL-6-stimulated STAT3 phosphorylation, Hep3B

cells were pretreated with CL-E (10, 30, and 60 µg/ml) for 1 h,

followed by IL-6 stimulation (10 ng/ml for 30 min).

As illustrated in Fig.

2B, CL-E strongly inhibited IL-6-induced STAT3 Tyr705

phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner, with maximal

suppression at 60 µg/ml. Conversely, CL-E exerted no inhibitory

effect on IL-6-stimulated STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation. Total STAT3

levels remained constant, indicating that the observed effects were

not due to changes in STAT3 protein expression. Give that

phosphorylation at STAT3 Tyr705 promotes STAT3 dimerization and

nuclear translocation, further examination of whether CL-E affects

STAT3 nuclear localization was conducted using immunofluorescence

microscopy. Hep3B cells cultured on chamber slides were pretreated

with CL-E (60 µg/ml) or genistein [60 µM, a known STAT3 inhibitor

(23)] for 1 h, followed by IL-6

stimulation for 4 h. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained

with an anti-STAT3 antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated secondary

antibody. In cells exposed to IL-6, STAT3 was predominantly

localized within the nucleus, indicative of its activated state.

Conversely, in cells pretreated with CL-E or genistein, STAT3 was

primarily cytoplasmic (Fig. 2C),

suggesting that CL-E effectively inhibits STAT3 nuclear

translocation, likely by suppressing Tyr705 phosphorylation.

These findings collectively demonstrate that CL-E

inhibits IL-6/STAT3 signaling by suppressing STAT3 Tyr705

phosphorylation and preventing its nuclear translocation, thereby

reducing its transcriptional activity.

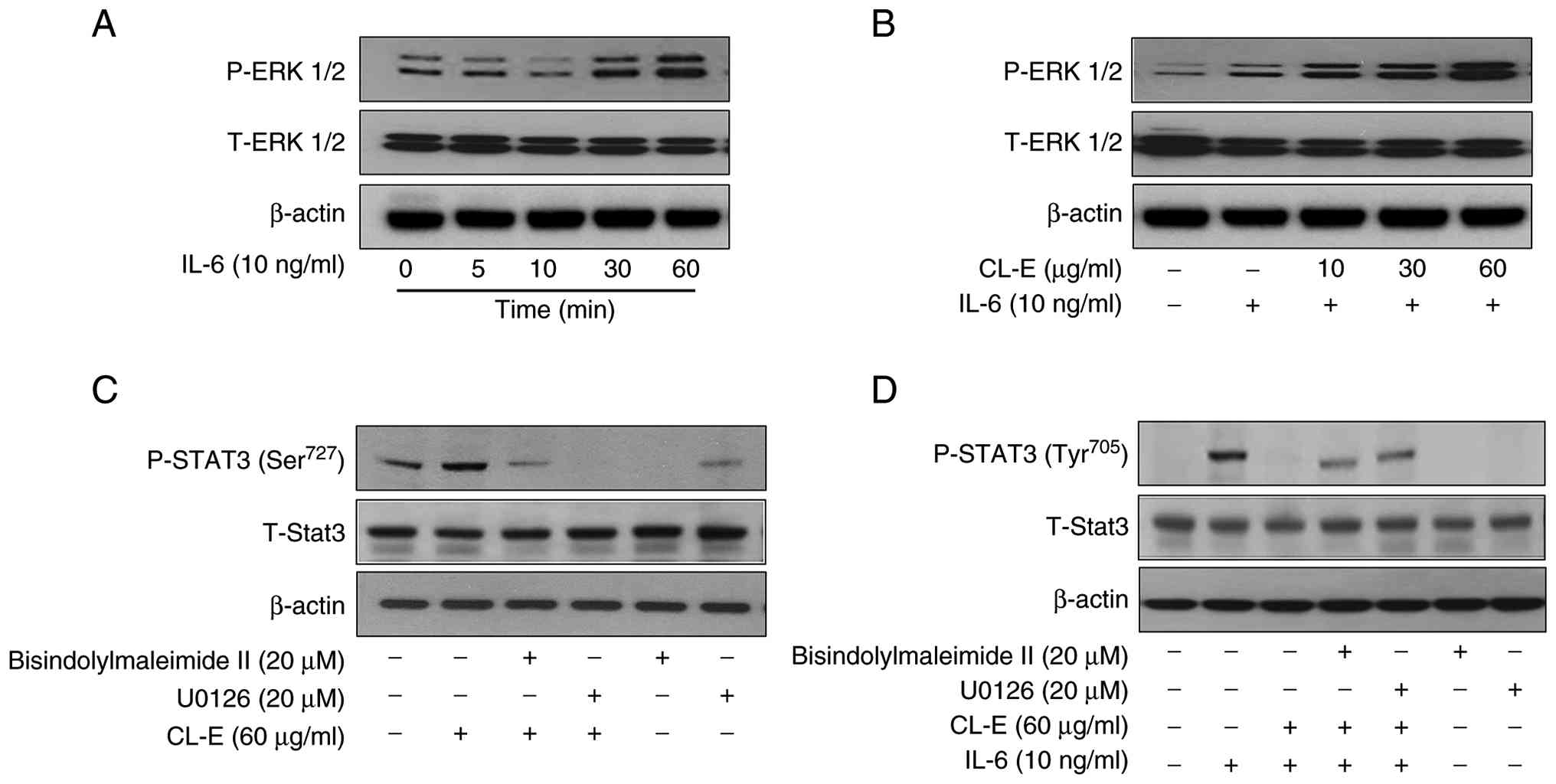

CL-E enhances ERK1/2 phosphorylation

and modulates STAT3 activation via the ERK signaling pathway

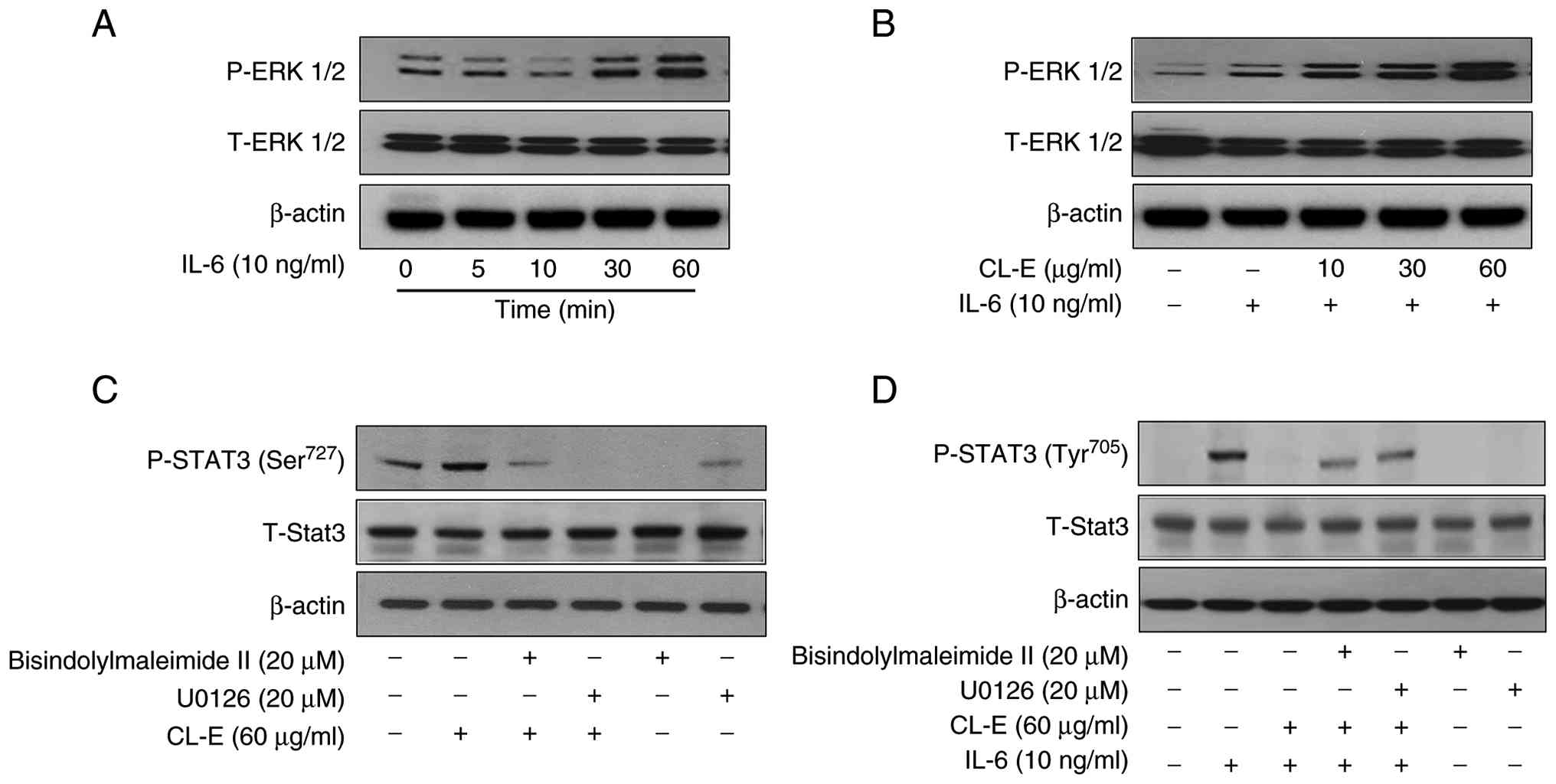

Previous studies have indicated that the activation

of ERK1/2 can modulate IL-6-induced STAT3 activation (24-26).

To investigate this possibility, we examined the involvement of the

ERK1/2 pathway, known to regulate STAT3 phosphorylation at Ser727.

Initially, we assessed ERK1/2 phosphorylation following IL-6

stimulation over time. Hep3B cells were treated with IL-6 (10

ng/ml) for 0, 5, 10, 30, and 60 min, and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was

analyzed via Western blotting. As depicted in Fig. 3A, ERK1/2 phosphorylation remained

low for the initial 10 min, began to increase at 30 min, and peaked

at 60 min. Subsequently, we investigated whether ERK1/2

phosphorylation was affected by CL-E treatment in the presence of

IL-6. Hep3B cells were pretreated with CL-E at concentrations of

10, 30, and 60 µg/ml for 1 h prior to IL-6 stimulation (10 ng/ml

for 30 min).

| Figure 3ERK signaling pathway contributes to

CL-E-mediated regulation of IL-6-induced STAT3 activation. (A)

Hep3B cells were stimulated with IL-6 (10 ng/ml) for the indicated

times (0, 5, 10, 30 and 60 min). Protein lysates underwent western

blotting analysis using antibodies against P-ERK1/2 and total

ERK1/2 to evaluate time-dependent ERK1/2 activation. (B) Cells were

pretreated with CL-E at 10, 30 and 60 µg/ml for 1 h, followed by

IL-6 stimulation (10 ng/ml) for 30 min. ERK1/2 phosphorylation was

analyzed by western blotting analysis. (C) To investigate the role

of ERK in STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation, cells were treated with

CL-E (60 µg/ml), PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide II (20 µM),

and/or the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (20 µM) for 1 h in the absence of

IL-6. Phosphorylation of STAT3 (Ser727) and total STAT3 were

examined by western blotting analysis. (D) To determine whether ERK

activation contributes to regulation of STAT3 Tyr705

phosphorylation, cells were pretreated with CL-E, U0126 and/or

bisindolylmaleimide II (20 µM) for 1 h before IL-6 stimulation (10

ng/ml, 30 min). STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation was analyzed by

western blotting. CL-E, Curcuma longa L. extract; IL-6,

interleukin 6; STAT3, signal transducer and activator of

transcription 3; P-, phosphorylated. |

As shown in Fig. 3B,

CL-E significantly enhanced IL-6-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation in

a concentration-dependent manner, with the strongest effect

observed at 60 µg/ml, suggesting that CL-E potentiates ERK

activation under IL-6 stimulation. To determine whether ERK

activation contributes to the regulation of STAT3 phosphorylation,

we assessed STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation in the absence of IL-6.

Hep3B cells were treated with CL-E (60 µg/ml), either alone or in

combination with the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126 or the PKC inhibitor

bisindolylmaleimide II. As shown in Fig. 3C, CL-E alone markedly increased

STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation. However, this effect was suppressed

by co-treatment with U0126, suggesting that CL-E-induced Ser727

phosphorylation is mediated through the MEK/ERK pathway.

Interestingly, bisindolylmaleimide II also attenuated Ser727

phosphorylation, indicating a possible role for PKC upstream of ERK

in mediating the effect of CL-E.

Finally, to further ascertain whether ERK- and

PKC-dependent signaling pathways are involved in the regulation of

STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation, we examined the effects of these

inhibitors under IL-6 stimulation. As depicted in Fig. 3D, CL-E pretreatment suppressed

IL-6-induced STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation, an effect that was

reversed by U0126. Similarly, co-treatment with bisindolylmaleimide

II partially restored Tyr705 phosphorylation, further corroborating

the involvement of PKC-ERK signaling in the modulation of

IL-6/STAT3 activation by CL-E.

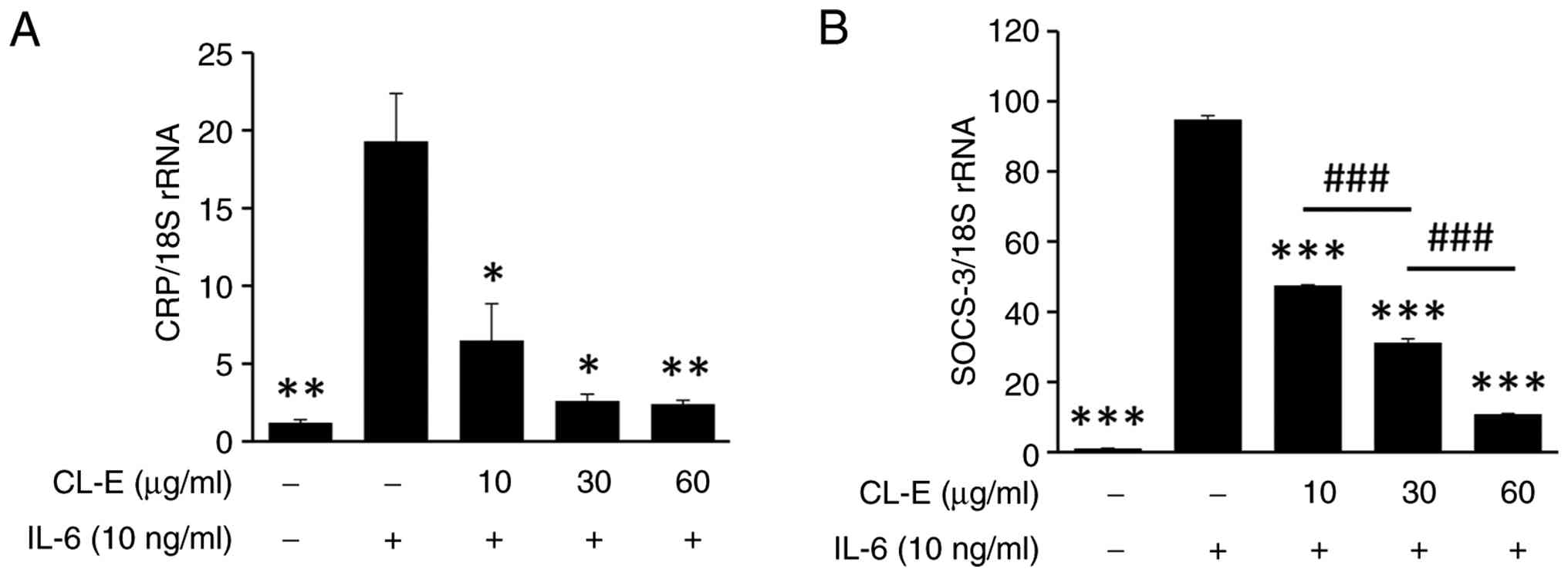

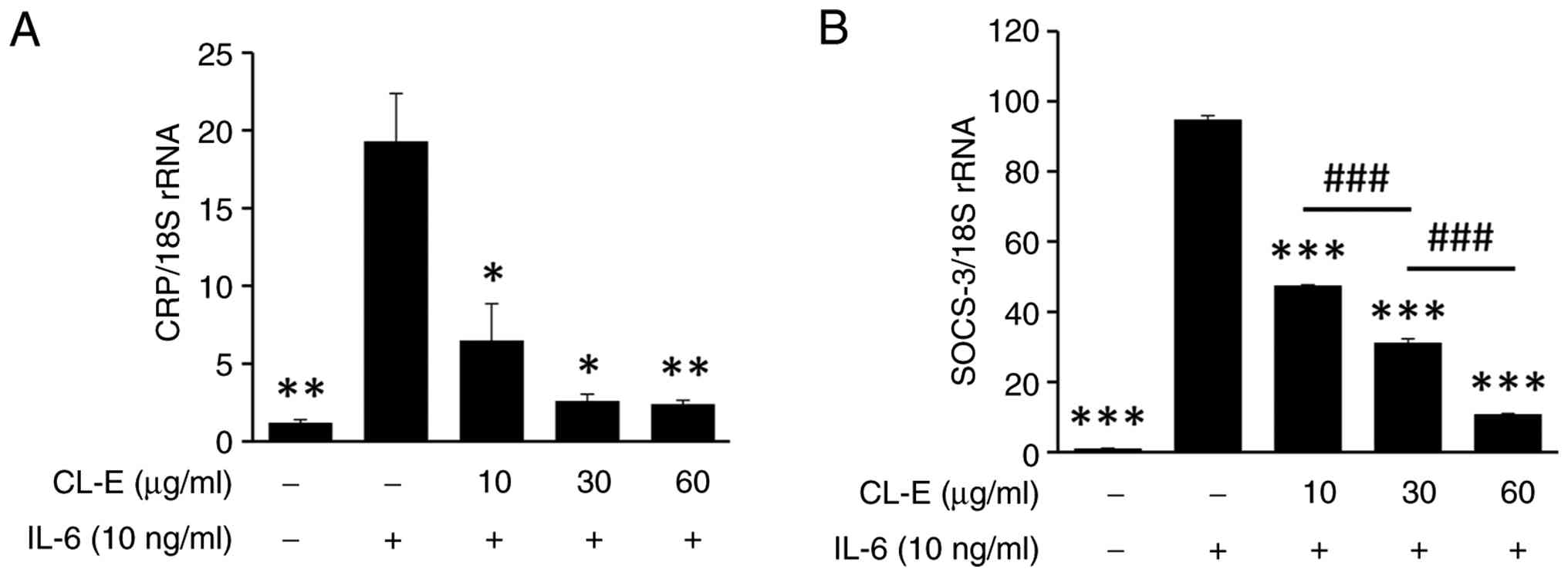

CL-E suppresses IL-6-induced

expression of CRP and SOCS, downstream targets of STAT3

signaling

CL-E suppresses IL-6-induced expression of CRP and

Suppressor of cytokine signaling 3 (SOCS3), downstream targets of

STAT3 signaling. CRP is primarily produced by hepatocytes in

response to IL-6 stimulation and can be transcriptionally induced

via the JAK/STAT3 pathway or a redox-sensitive NF-κB pathway

mediated by Rac1 activation (27-29).

SOCS3 acts as a classical negative feedback regulator of

IL-6-induced JAK/STAT3 signaling by binding to phosphorylated

tyrosine residues on JAK kinases (9).

Given that SOCS3 is a direct transcriptional target

of STAT3, the inhibition of STAT3 signaling results in decreased

SOCS3 expression. To assess the downstream effects of CL-E-mediated

STAT3 inhibition, we examined the expression of

inflammation-related target genes regulated by IL-6/STAT3

signaling. We focused on CRP and SOCS3, both recognized as STAT3

target genes, serving as indicators of the inflammatory response

and negative feedback regulation, respectively (30). Hep3B cells were pretreated with CL-E

(10, 30, and 60 µg/ml) for 1 h, followed by IL-6 stimulation (10

ng/ml) for 6 h. Total RNA was extracted, and mRNA levels of CRP and

SOCS3 were quantified via real-time PCR using 18S rRNA as the

internal control. As illustrated in Fig. 4, IL-6 treatment significantly

upregulated the expression of both CRP and SOCS3 mRNA levels

compared to those of untreated cells. Pretreatment with CL-E

significantly attenuated IL-6-induced expression of both genes, and

a concentration-dependent reduction was observed for SOCS-3.

| Figure 4CL-E inhibits IL-6-induced expression

of CRP and SOCS3 mRNA in Hep3B cells. Hep3B cells were pretreated

with CL-E at concentrations of 10, 30, and 60 µg/ml for 1 h,

followed by IL-6 stimulation (10 ng/ml) for 6 h. Total RNA was

extracted, and the mRNA levels of (A) CRP and (B) SOCS3 were

measured using quantitative real-time PCR. Gene expression levels

were normalized to 18S rRNA and are presented as fold change

relative to the untreated control. Data represent the mean ± SE

(n≥3). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and

***P<0.001 vs. the IL-6-treated group;

###P<0.001. CL-E, Curcuma longa L. extract;

IL-6, interleukin 6; CRP, C reactive protein; P-, phosphorylated;

SOCS3, suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. |

These findings indicate that CL-E effectively

suppresses IL-6/STAT3-dependent transcriptional activation of both

pro-inflammatory (CRP) and feedback inhibitor genes

(SOCS3). This transcriptional repression aligns with the

observed inhibition of STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation and nuclear

translocation by CL-E (Fig. 2),

further supporting its potential as an anti-inflammatory agent

targeting the IL-6/STAT3 signaling axis.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that CL-E effectively

inhibits IL-6-induced STAT3 activation in Hep3B cells. CL-E

suppressed STAT3-dependent transcriptional activity in a

dose-dependent manner without inducing cytotoxicity.

Mechanistically, CL-E inhibited phosphorylation of STAT3 at Tyr705,

blocked its nuclear translocation, and reduced the expression of

STAT3 downstream target genes such as CRP and SOCS3.

Notably, CL-E enhanced ERK1/2 phosphorylation, which led to

increased STAT3 Ser727 phosphorylation. Pharmacological inhibition

of the ERK and PKC pathways reversed CL-E-mediated inhibition of

STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation, suggesting a regulatory crosstalk

between MAPK signaling and STAT3 activation. These findings are

consistent with previous reports on natural product-derived STAT3

inhibitors. For example, manassantin A and B from Saururus

chinensis, and Kansuinine A and B from Euphorbia kansui

L. have been shown to suppress IL-6-induced STAT3

phosphorylation and nuclear translocation by targeting both STAT3

Tyr705 and ERK1/2-mediated Ser727 phosphorylation (31,32).

In agreement with previous reports, CL-E also appears to exert dual

modulatory activity, suppressing canonical STAT3 activation via

STAT3 Tyr705 phosphorylation while activating ERK signaling,

possibly as part of a feedback or compensatory mechanism. These

results suggest that CL-E may serve as a promising natural

therapeutic candidate for targeting STAT3-mediated inflammation and

cancer progression. The differential regulation of STAT3

phosphorylation at Tyr705 and Ser727 by CL-E is particularly

noteworthy, given that these two phosphorylation sites serve

distinct roles in STAT3 signaling. Tyr705 phosphorylation is

critical for STAT3 dimerization, nuclear translocation, and DNA

binding, and is typically considered a hallmark of canonical STAT3

activation in response to cytokines such as IL-6 (27,33).

In contrast, Ser727 phosphorylation, which is often mediated by

MAPK or PKC signaling, contributes to the modulation of STAT3's

transcriptional activity, interaction with co-activators, and in

certain contexts, non-canonical functions (34). To further investigate the modulation

of STAT3 signaling by CL-E, we examined previous evidence

implicating the ERK and PKC pathways in IL-6 signal transduction.

It has been documented that PKC activation by phorbol esters, such

as PMA, can influence IL-6 signaling through ERK activation

(24). While ERK signaling has been

shown to synergize with the JAK/STAT pathway in enhancing

cytokine-induced gene expression in certain contexts (35), other studies suggest that ERK

activation can also antagonize STAT3 signaling, contingent upon the

cellular environment (34,36,37).

Notably, SOCS3, a well-known negative feedback regulator of the

JAK/STAT pathway, has been reported to be upregulated by PMA via

ERK activation, and this induction was inhibited by MAPK inhibitors

(38). Based on these findings, we

hypothesized that the inhibitory effect of CL-E on STAT3 activation

may involve the activation of PKC and ERK1/2. Indeed, our results

demonstrated that CL-E significantly induced ERK1/2

phosphorylation, which was abolished by the MEK1/2 inhibitor U0126,

indicating that the effect is dependent on the MAPK/ERK

pathway.

Furthermore, CL-E enhanced STAT3 Ser727

phosphorylation even in the absence of IL-6, and this effect was

diminished by co-treatment with the PKC inhibitor

bisindolylmaleimide II, suggesting that PKC activity contributes to

this mechanism. Given previous reports that ERK-mediated STAT3

Ser727 phosphorylation can interfere with STAT3 Tyr705

phosphorylation (34,36,37),

our findings support a model in which CL-E-mediated ERK activation

leads to a shift in STAT3 phosphorylation balance, thereby

attenuating its activation. Collectively, these results highlight

ERK and PKC signaling as key modulators involved in the suppression

of IL-6/STAT3 signaling by CL-E. The ability of CL-E to suppress

IL-6-induced expression of CRP and SOCS3 further supports its

anti-inflammatory potential. CRP is a classical acute-phase protein

synthesized in hepatocytes under IL-6/STAT3 regulation, and

elevated CRP levels are widely used as biomarkers for systemic

inflammation, cardiovascular risk, and cancer prognosis (39,40).

In our study, CL-E treatment markedly reduced CRP mRNA expression

in IL-6-stimulated Hep3B cells, suggesting that CL-E may attenuate

systemic inflammatory responses at the transcriptional level.

SOCS3, another STAT3 target gene, acts as a negative

feedback regulator by binding to JAKs and preventing further

cytokine signaling. Although SOCS3 is classically viewed as an

inhibitor of STAT3 signaling, paradoxically, its overexpression in

chronic inflammatory states can desensitize anti-inflammatory

signals and contribute to persistent disease persistence (41,42).

Our finding that CL-E downregulates SOCS3 expression suggests that

it may restore homeostatic feedback mechanisms by reprogramming the

inflammatory environment. These findings are consistent with

previous studies on flavonoids and diarylheptanoids derived from

natural products, which have demonstrated suppression of

IL-6-stimulated inflammatory markers and STAT3 target genes

(30,43). Collectively, our results highlight

the therapeutic potential of CL-E as a botanical modulator of

inflammatory signaling, particularly in diseases characterized by

hyperactivation of the IL-6/STAT3 axis, such as rheumatoid

arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, metabolic syndrome, and

hepatocellular carcinoma. The rhizome of C. longa has been

extensively studied and commercialized for its curcuminoid content

and associated pharmacological activities, including

anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and anticancer effects (8,44,45).

In contrast, the aerial parts, particularly the

leaves, have been relatively understudied in scientific research.

Nonetheless, recent investigations have begun to reveal that C.

longa leaves contain bioactive compounds such as polyphenols,

flavonoids, and tannins, which exhibit antioxidant and

antimicrobial properties (19-21).

The present study further corroborates the potential of CL-E as an

effective modulator of IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Notably, CL-E was able

to modulate the STAT3 signaling pathway without inducing

cytotoxicity, underscoring its potential as a safe, mechanism-based

botanical regulator of inflammatory responses. Furthermore, our

data suggest that CL-E operates through ERK- and PKC-dependent

pathways, offering new insights into how its phytochemicals may

regulate the IL-6 signaling cascade. Future research should focus

on isolating and structurally characterizing the active

constituents of CL-E, and on evaluating their in vivo

efficacy in various IL-6–driven animal models of rheumatoid

arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, such as collagen-induced

arthritis (RA) and DSS-induced colitis (IBD). Additionally,

comparative studies with turmeric rhizome extracts, regarding

bioactivity and chemical composition, may elucidate whether CL-E

offers distinct advantages in terms of potency, selectivity, or

safety. From a resource utilization perspective, the use of C.

longa aerial parts, which are often discarded during

cultivation, could contribute to more sustainable and comprehensive

utilization of this medicinal plant.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the late Dr

Jong Sun Chang, formerly with the Eco-friendly Biomaterial Research

Center, Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology,

Jeongeup, Republic of Korea, for her valuable contributions and

unwavering support to this work. This study is respectfully

dedicated to her memory.

Funding

Funding: This research was supported by the Regional Innovation

System & Education (RISE) program through the Daejeon RISE

Center, funded by the Ministry of Education and the Daejeon

Metropolitan City, Republic of Korea (grant no. 2025-RISE-06-013);

the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology

Research Initiative Program (grant no. KGM1052612) and

Global-Learning & Academic Research Institution for Master's

and PhD students, the Postdocs Program of the National Research

Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Ministry of Education

(grant no. RS-2023-00301914); and an NRF grant funded by the Korean

Government (grant no. RS-2024-00338822).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study may be

requested from the corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

SWL and SL conceived and designed the study. HJJ,

EJP and YK performed the experiments and analyzed the data. EP and

WK contributed to the design of the experiments, and to the

analysis and interpretation of the data, and, together with SWL and

SL, supervised the overall research. HJJ and YK wrote the original

manuscript. EP and WK, together with SWL and SL, revised the

manuscript critically for important intellectual content and

confirmed the authenticity of all the raw data. All authors read

and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Strassmann G, Masui Y, Chizzonite R and

Fong M: Mechanisms of experimental cancer cachexia. Local

involvement of IL-1 in colon-26 tumor. J Immunol. 150:2341–2345.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Kishimoto T: Interleukin-6: From basic

science to medicine-40 years in immunology. Annu Rev Immunol.

23:1–21. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3

|

Lütticken C, Wegenka UM, Yuan J, Buschmann

J, Schindler C, Ziemiecki A, Harpur AG, Wilks AF, Yasukawa K, Taga

T, et al: Association of transcription factor APRF and protein

kinase Jak1 with the interleukin-6 signal transducer gp130.

Science. 263:89–92. 1994.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Ihle JN: STATs: Signal transducers and

activators of transcription. Cell. 84:331–334. 1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Sebti SM and Der CJ: Opinion: Searching

for the elusive targets of farnesyltransferase inhibitors. Nat Rev

Cancer. 3:945–951. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Darnell JE Jr: STATs and gene regulation.

Science. 277:1630–1635. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Aaronson DS and Horvath CM: A road map for

those who don't know JAK-STAT. Science. 296:1653–1655.

2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

8

|

Aggarwal BB, Kunnumakkara AB, Harikumar

KB, Gupta SR, Tharakan ST, Koca C, Dey S and Sung B: Signal

transducer and activator of transcription-3, inflammation, and

cancer: How intimate is the relationship? Ann N Y Acad Sci.

1171:59–76. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

9

|

Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns

HM, Müller-Newen G and Schaper F: Principles of interleukin

(IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J.

374:1–20. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Zhang D, Sun M, Samols D and Kushner I:

STAT3 participates in transcriptional activation of the C-reactive

protein gene by interleukin-6. J Biol Chem. 271:9503–9509.

1996.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Nishiyama T, Mae T, Kishida H, Tsukagawa

M, Mimaki Y, Kuroda M, Sashida Y, Takahashi K, Kawada T, Nakagawa K

and Kitahara M: Curcuminoids and sesquiterpenoids in turmeric

(Curcuma longa L.) suppress an increase in blood glucose

level in type 2 diabetic KK-Ay mice. J Agric Food Chem. 53:959–963.

2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Asai A, Nakagawa K and Miyazawa T:

Antioxidative effects of turmeric, rosemary and capsicum extracts

on membrane phospholipid peroxidation and liver lipid metabolism in

mice. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 63:2118–2122. 1999.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Samaha HS, Kelloff GJ, Steele V, Rao CV

and Reddy BS: Modulation of apoptosis by sulindac, curcumin,

phenylethyl-3-methylcaffeate, and 6-phenylhexyl isothiocyanate:

Apoptotic index as a biomarker in colon cancer chemoprevention and

promotion. Cancer Res. 57:1301–1305. 1997.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Jayaprakasha GK, Jena BS, Negi PS and

Sakariah KK: Evaluation of antioxidant activities and

antimutagenicity of turmeric oil: A byproduct from curcumin

production. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 57:828–835. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

15

|

Hong CH, Noh MS, Lee WY and Lee SK:

Inhibitory effects of natural sesquiterpenoids isolated from the

rhizomes of Curcuma zedoaria on prostaglandin E2 and nitric oxide

production. Planta Med. 68:545–547. 2002.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

16

|

Pothitirat W and Gritsanapan W: Variation

of bioactive components in Curcuma longa in Thailand. Curr

Sci. 91:1397–1400. 2006.

|

|

17

|

Bhardwaj KS, Bhardwaj RS, Ranjeet D and

Ganesh N: Curcuma longa leaves exhibits a potential

antioxidant, antibacterial and immunomodulating properties. Int J

Phytomed. 3:270–278. 2011.

|

|

18

|

Abida Y, Tabassum F, Zaman S, Chhabi SB

and Islam N: Biological screening of Curcuma longa L. for

insecticidal and repellent potentials against Tribolium castaneum

(Herbst) adults. Univ J Zool Rajshahi Univ. 28:69–71. 2009.

|

|

19

|

Kim DW, Lee SM, Woo HS, Park JY, Ko BS,

Heo JD, Ryu YB and Lee WS: Chemical constituents and

anti-inflammatory activity of the aerial parts of Curcuma

longa. J Funct Foods. 26:485–493. 2016.

|

|

20

|

Ahn D, Lee EB, Ahn MS, Lim HW, Xing MM,

Tao C, Yang JH and Kim DK: Antioxidant constituents of the aerial

parts of Curcuma longa Kor. J Pharmacogn. 43:274–278.

2012.

|

|

21

|

Jiang CL, Tsai SF and Lee SS: Flavonoids

from Curcuma longa leaves and their NMR assignments. Nat

Prod Commun. 10:63–66. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lee SJ, Jang HJ, Kim Y, Oh HM, Lee S, Jung

K, Kim YH, Lee WS, Lee SW and Rho MC: Inhibitory effects of

IL-6-induced STAT3 activation of bio-active compounds derived from

Salvia plebeia R.Br. Process Biochem. 51:2222–2229.

2016.

|

|

23

|

Li HC and Zhang GY: Inhibitory effect of

genistein on activation of STAT3 induced by brain

ischemia/reperfusion in rat hippocampus. Acta Pharmacol Sin.

24:1131–1136. 2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Sengupta TK, Talbot ES, Scherle PA and

Ivashkiv LB: Rapid inhibition of interleukin-6 signaling and Stat3

activation mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Proc Natl

Acad Sci USA. 95:11107–11112. 1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

25

|

Alessi DR, Cuenda A, Cohen P, Dudley DT

and Saltiel AR: PD 098059 is a specific inhibitor of the activation

of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase in vitro and in vivo. J

Biol Chem. 270:27489–27494. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

26

|

Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ

and Saltiel AR: A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated

protein kinase cascade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 92:7686–7689.

1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

27

|

Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Müller-Newen G,

Schaper F and Graeve L: Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling

through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J. 334:297–314.

1998.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

28

|

Ochrietor JD, Harrison KA, Zahedi K and

Mortensen RF: Role of STAT3 and C/EBP in cytokine-dependent

expression of the mouse serum amyloid P-component (SAP) and

C-reactive protein (CRP) genes. Cytokine. 12:888–899.

2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

29

|

Zhang D, Jiang SL, Rzewnicki D, Samols D

and Kushner I: The effect of interleukin-1 on C-reactive protein

expression in Hep3B cells is exerted at the transcriptional level.

Biochem J. 310:143–148. 1995.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

30

|

Lim HJ, Jang HJ, Bak SG, Lee S, Lee SW,

Lee KM, Lee SJ and Rho MC: In vitro inhibitory effects of cirsiliol

on IL-6-induced STAT3 activation through anti-inflammatory

activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 29:1586–1592. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

31

|

Chang JS, Lee SW, Kim MS, Yun BR, Park MH,

Lee SG, Park SJ, Lee WS and Rho MC: Manassantin A and B from

Saururus chinensis inhibit interleukin-6-induced signal

transducer and activator of transcription 3 activation in Hep3B

cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 115:84–88. 2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Chang JS, Lee SW, Park MH, Kim MS, Hudson

BI, Park SJ, Lee WS and Rho MC: Kansuinine A and Kansuinine B from

Euphorbia kansui L. inhibit IL-6-induced Stat3 activation.

Planta Med. 76:1544–1549. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Hodge DR, Hurt EM and Farrar WL: The role

of IL-6 and STAT3 in inflammation and cancer. Eur J Cancer.

41:2502–2512. 2005.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Chung J, Uchida E, Grammer TC and Blenis

J: STAT3 serine phosphorylation by ERK-dependent and -independent

pathways negatively modulates its tyrosine phosphorylation. Mol

Cell Biol. 17:6508–6516. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Stancato LF, Sakatsume M, David M, Dent P,

Dong F, Petricoin EF, Krolewski JJ, Silvennoinen O, Saharinen P,

Pierce J, et al: Beta interferon and oncostatin M activate Raf-1

and mitogen-activated protein kinase through a JAK1-dependent

pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 17:3833–3840. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Beadling C, Ng J, Babbage JW and Cantrell

DA: Interleukin-2 activation of STAT5 requires the convergent

action of tyrosine kinases and a serine/threonine kinase pathway

distinct from the Raf1/ERK2 MAP kinase pathway. EMBO J.

15:1902–1913. 1996.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Lee HK, Jung J, Lee SH, Seo SY, Suh DJ and

Park HT: Extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation is

required for serine 727 phosphorylation of STAT3 in Schwann cells

in vitro and in vivo. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 13:161–168.

2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Terstegen L, Gatsios P, Bode JG, Schaper

F, Heinrich PC and Graeve L: The inhibition of

interleukin-6-dependent STAT activation by mitogen-activated

protein kinases depends on tyrosine 759 in the cytoplasmic tail of

glycoprotein 130. J Biol Chem. 275:18810–18817. 2000.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

39

|

Pepys MB and Hirschfield GM: C-reactive

protein: A critical update. J Clin Invest. 111:1805–1812.

2003.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Ridker PM: From C-reactive protein to

interleukin-6 to interleukin-1: Moving upstream to identify novel

targets for atheroprotection. Circ Res. 118:145–156.

2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, Murakami M,

Chinen T, Aki D, Hanada T, Takeda K, Akira S, Hoshijima M, et al:

IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3

in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 4:551–556. 2003.PubMed/NCBI View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

El Kasmi KC, Holst J, Coffre M, Mielke L,

de Pauw A, Lhocine N, Smith AM, Rutschman R, Kaushal D, Shen Y, et

al: General nature of the STAT3-activated anti-inflammatory

response. J Immunol. 177:7880–7888. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Jang HJ, Park EJ, Lee SJ, Lim HJ, Jo JH,

Lee SW and Rho MC: Diarylheptanoids from Curcuma phaeocaulis

suppress IL-6-induced STAT3 activation. Planta Med. 85:94–102.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Rajasingh J, Raikwar HP, Muthian G,

Johnson C and Bright JJ: Curcumin induces growth-arrest and

apoptosis in association with the inhibition of constitutively

active JAK-STAT pathway in T cell leukemia. Biochem Biophys Res

Commun. 340:359–368. 2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

45

|

Saydmohammed M, Joseph D and Syed V:

Curcumin suppresses constitutive activation of STAT-3 by

up-regulating protein inhibitor of activated STAT-3 (PIAS-3) in

ovarian and endometrial cancer cells. J Cell Biochem. 110:447–456.

2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|