Introduction

Cerebral infarction is one of the main causes of

death among adults in China. Between 2004 and 2005, the crude

mortality rate of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases was

136.6/100,000 people, and the standardized mortality rate was

120.1/100,000 people. Among these, intracerebral hemorrhage

accounted for 50.4% of the deaths from cardiovascular and

cerebrovascular disease, followed by cerebral infarction, which

accounted for 24.8% (1). Cerebral

infarction not only reduces quality of life but also imposes a

heavy economic burden on the patient and their family (2). The current treatment methods for

cerebral infarction primarily include interventional therapy,

surgery and drug treatment. A survey of 408 elderly patients with

hemiplegia due to acute ischemic stroke revealed that their

standardized scores on the Stroke-Specific Quality of Life Scale 1

month after discharge were (56.30±5.21)%, only reaching a moderate

level; the actual scores were even lower at (136.35±5.38),

indicating suboptimal functional recovery following cerebral

infarction injury (2).

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are adult SCs with

self-renewal and multi-directional differentiation potential, and

come from a range of sources, including bone marrow, fat, umbilical

cord and other tissue. MSCs exhibit low immunogenicity and easy

in vitro culture expansion, and have demonstrated potential

therapeutic value in the treatment of various diseases including

cerebral infarction, Parkinson's disease, arthritis, spinal cord

and sciatic nerve injury (3). SC

therapy plays multiple roles in ischemic cerebral infarction,

including neuroprotection through reducing apoptosis and

inflammation, promoting angiogenesis and endogenous neurogenesis,

modulating immune responses, and potentially differentiating into

neural cells to replace damaged tissue. Clinical studies on

mesenchymal SC (MSC) transplantation for ischemic cerebral

infarction have been conducted, confirming its safety and

feasibility in both the acute and chronic phases; preliminary

evidence indicates that motor function recovery can be improved

through various administration routes, such as intravenous,

intra-arterial, and intracerebral methods (4,5). MSC

therapy may be an effective method to improve the prognosis of

patients with cerebral infarction. It is helpful for clinicians to

understand the effectiveness and safety of MSCs in the treatment of

cerebral infarction to provide a basis for the feasibility of

future clinical application. The present study focused on the

efficacy and safety of MSCs in the treatment of cerebral

infarction, aiming to provide a novel approach for the treatment of

cerebral infarction in addition to traditional thrombolysis, drug

and rehabilitation treatment. The present study also aimed to

provide a reference for exploring optimized therapeutic protocols

of MSCs for cerebral infarction.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

VIP Information (qikan.cqvip.com), China National Knowledge

Infrastructure (cnki.net), Wanfang Data (wanfangdata.com.cn/index.html), PubMed

(pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), Cochrane

Library (cochranelibrary.com) and Web of

Science (https://webofscience.clarivate.cn/) were searched from

the establishment of the database to October 2024 for studies on

the treatment of cerebral infarction with MSCs. The Chinese

literature search terms were as follows: ‘Mesenchymal stem cells’,

‘stem cells’, ‘mesenchymal cells’, ‘cerebral infarction’, ‘ischemic

stroke’, ‘stroke’, ‘stroke’, ‘randomized controlled trial’, ‘RCT’,

‘randomized’. English literature search terms included ‘mesenchymal

stem cell’, ‘stem cell’, ‘cerebral infarction’, ‘stroke’ and

‘randomized controlled trial’.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were as follows: i) Randomized

controlled trials, with or without blinding; ii) patients meeting

the diagnostic criteria for cerebral infarction; iii) use of MSC

treatment, or MSCs combined with other treatments (such as drug or

rehabilitation therapy); iv) use of other treatment as a control

group (such as conventional drug therapy, rehabilitation, placebo);

v) studies reporting National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

score (NIHSS) (6), Fugl-Meyer

Assessment (FMA) (7), Functional

Independence Measure (FIM) (8),

Barthel Index(BI) (9), modified

Rankin scale score (mRS) (10),

adverse events or adverse reactions following treatment (such as

infection, immune response, tumor formation); vi) studies with

complete original data that can be directly or indirectly extracted

for analysis (mean, standard deviation, sample size) and vii)

studies written in Chinese and English. There were no restrictions

on age, sex or ethnicity of patients.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were as follows: i) Retrospective

studies, case reports, reviews, meta-analyses, conference abstracts

and other non-randomized controlled trials; ii) animal studies,

in vitro experiments or non-clinical studies; iii) lack of

control group or non-randomized grouping; iv) high risk of bias

(unclear randomization methods, inadequate allocation concealment);

v) incomplete data regarding outcome indicators and inability to

extract data for primary or secondary outcomes and vi) unavailable

full text.

Literature screening

Studies were checked for plagiarism, then the titles

and abstracts of the literature were read for preliminary screening

according to the aforementioned criteria. Duplicate articles were

removed. For articles with duplicate data, the study containing the

most complete data was retained.

Data extraction

Excel (Version 12.1.0.24034, wps.cn) was used

to extract data as follows: Cell type, transplantation method,

intervention, sample size, age, sex, follow-up time, outcome

indicators and adverse reactions. For missing data, it was

attempted to contact the authors of the original study for complete

information. Studies for which missing data could not be obtained

were excluded.

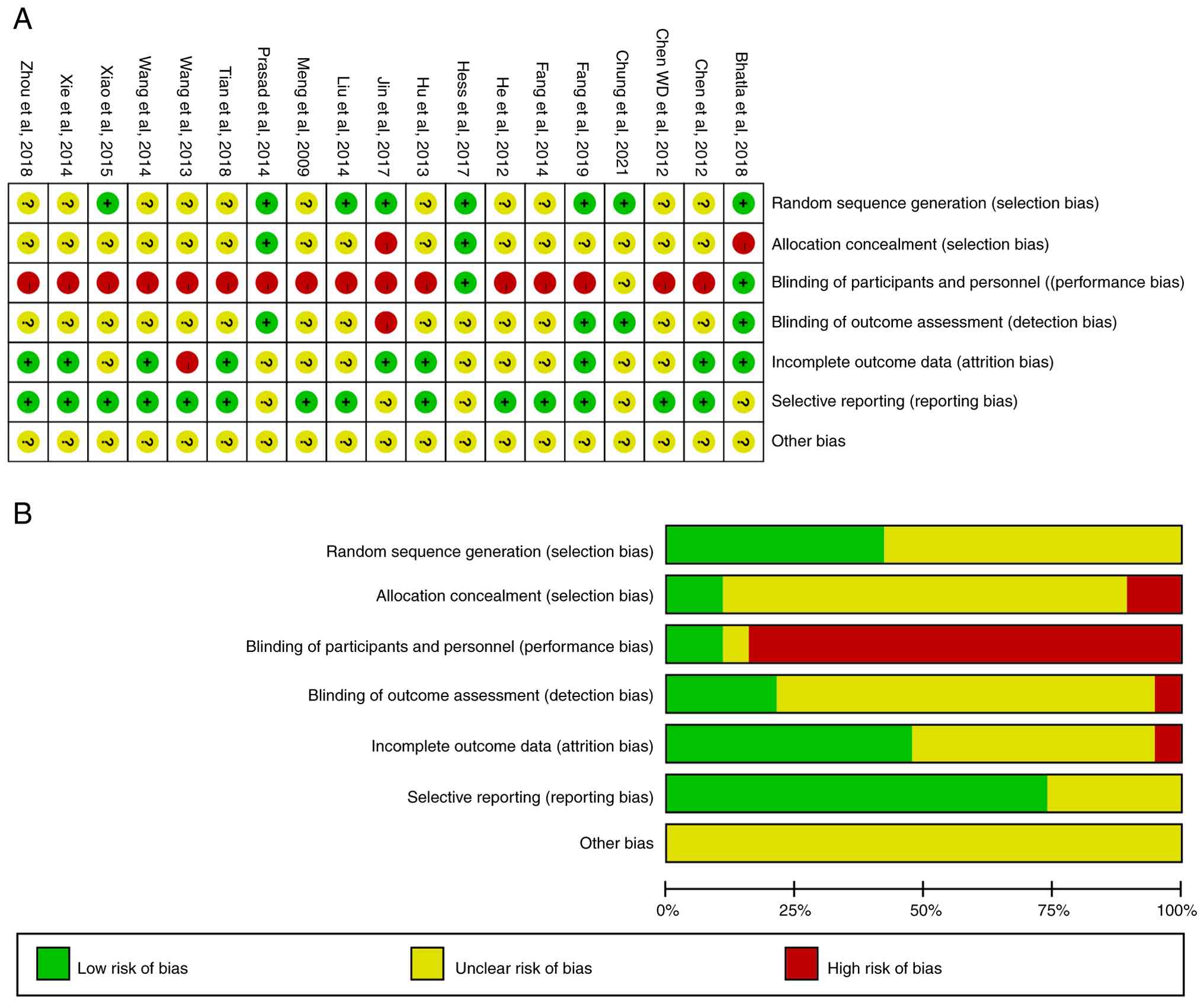

Quality assessment

The risk assessment was performed using the bias

assessment tools recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration

(11). The assessment contents

included randomization methods, allocation concealment, blinding,

blinded assessment of study outcomes, integrity of outcome data,

selective reporting of study results and other sources. Risk of

bias was reported as high, low or unclear.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.4.1

(https://www.cochrane.org) and Stata16.0

(https://www.stata.com) software. Among the

continuous variables, the mean difference (MD) was used as the

effect size for those with the same measurement method and unit,

and the odds ratio (OR) was used as the effect size for dichotomous

variables, both of which were expressed as 95%CI. Heterogeneity was

analysed using the Pearson χ2 and I2 tests,

with P>0.1 indicating no heterogeneity and P<0.1 indicating

heterogeneity. I2=0 means studies are completely

homogeneous, and I2 >50% means that there is

significant heterogeneity; If there was no significant

heterogeneity between studies, a fixed-effect model was used for

analysis, and a random-effects model was used after excluding

significant sources of heterogeneity. P≤0.05 was considered to

indicate a statistically significant difference. Sources of

heterogeneity were investigated using sensitivity and subgroup

analyses. Subgroup analyses were performed for cell type,

transplantation method and length of follow-up for the primary

outcome measures.

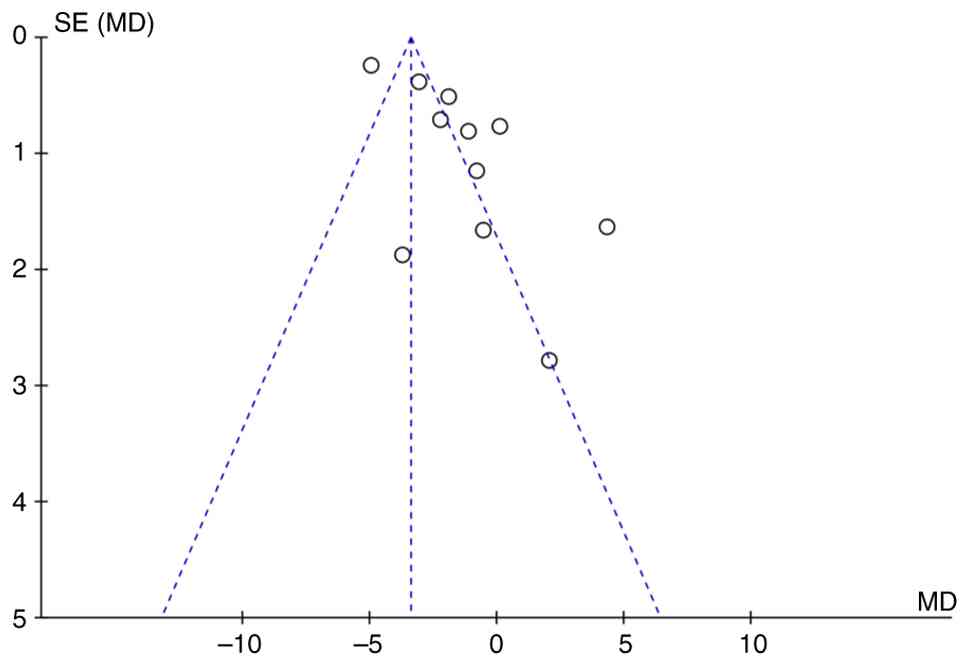

Publication bias analysis

RevMan 5.4.1 software was used to draw the funnel

plot and assess the presence of publication bias by observing the

symmetry of the funnel plot. If the funnel plot presents a

symmetrical inverted funnel shape, it suggests a low risk of

publication bias; if the funnel plot shows an obvious asymmetry, it

indicates the existence of potential publication bias. Stata 16.0

software was used to conduct Egger's test. P<0.05 was considered

to indicate statistically significant publication bias.

Results

Included studies

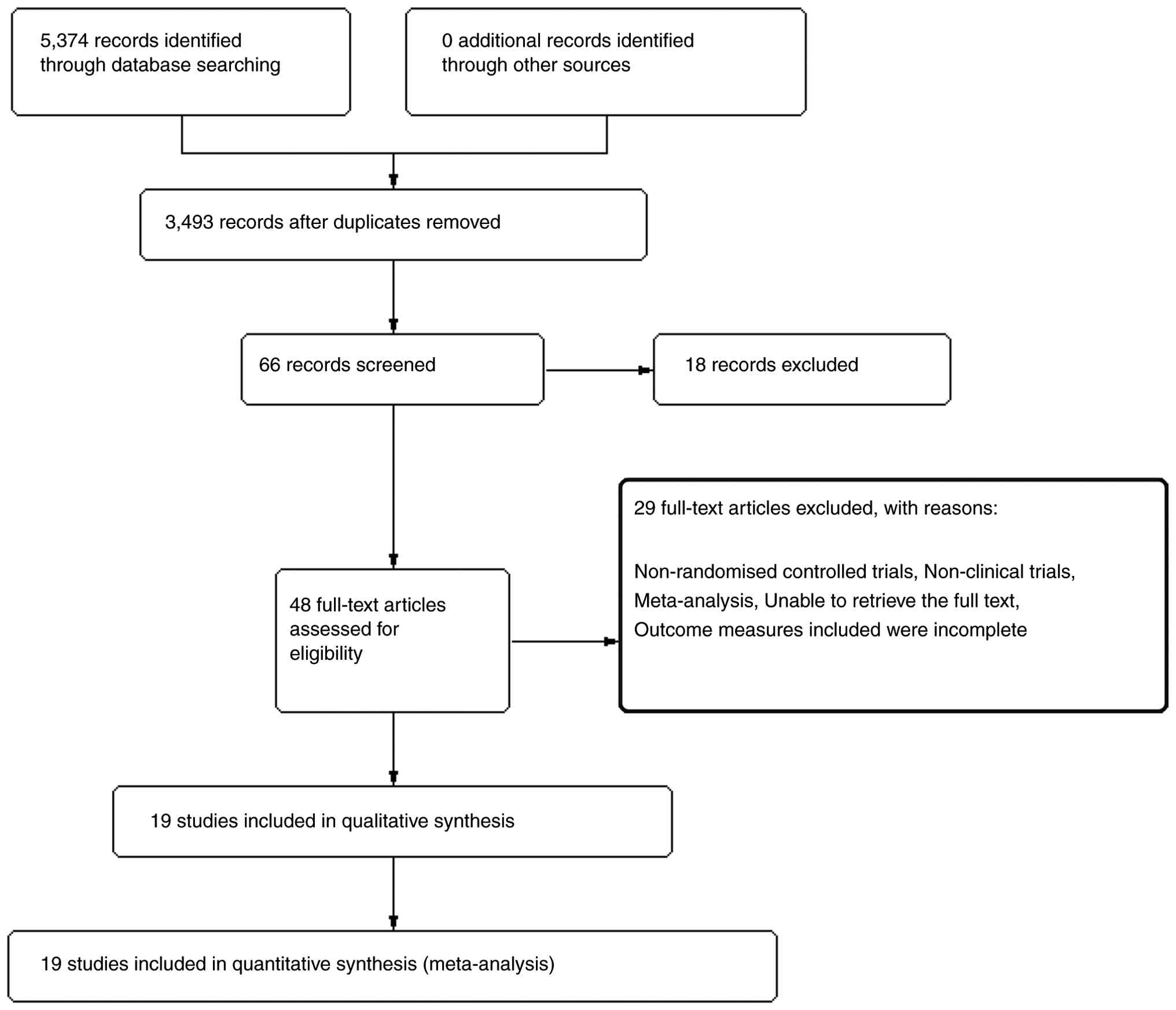

A total of 5,374 articles were retrieved initially.

After duplicate checking, 3,493 articles were included. After

reading the titles and abstracts of the articles, 66 articles were

included for full-text assessment. A total of 18 articles that did

not meet the requirements were excluded, and 48 articles were

included for full-text reading. After excluding 29 articles during

full-text reading, 19 articles (12-30)

were included (Fig. 1). Of these,

13 were in Chinese (14,15,19-21,23-30)

and six were in English (12,13,16-18,22).

All studies described the baseline comparability between the

experimental group and the control group. The intervention measures

were primarily MSCs + conventional treatment vs. conventional

treatment. The total sample size was 1,366 cases, with 697 cases in

the experimental group and 669 cases in the control group (Table I).

| Table IStudy characteristics. |

Table I

Study characteristics.

| | | Intervention | Age, years | |

|---|

| First author,

year | Cell type | Transplantation

method | Interval | Tx time, days | E | C | E | C | Follow-up time,

months | Outcome

measures | Adverse

effects | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Wang et al,

2014 | BMSC | Not reported | 30-60 days | Not reported | BMSC + con | Con | 56.3 | 56.3 (median) | 1 and 6 | FIM | No adverse

effects | (21) |

| Tian et al,

2018 | UBMSC | 22 LP; 23 IV | 14-30 days | 30 | UBMSC + con | Con | 62.2± 2.1 | 60.6±1.7

(mean) | 1, 2 and 3 | NIHSS; FMA | Not reported | (14) |

| Zhou et al,

2018 | UBMSC | LP | 1 year | 21 | UBMSC + con | Con | 56.3± 5.3

(mean) | 56.3±5.2

(mean) | 12 | BI; FIM | Fever, rash | (15) |

| Xiao et al,

2015 | UBMSC | LP | 1-13 years | Not reported | UBMSC + con | Con | 51.9± 5.2

(mean) | 52.3±5.0

(mean) | 6 | FIM | Not reported | (19) |

| Xie et al,

2014 | BMSC | LP | 7 days | 14 | BMSC + con | Con | 51.4±7.2

(mean) | 53.7±6.1

(mean) | 3 and 6 | NIHSS; BI | Fever;

headache | (20) |

| Hu et al,

2013 | UCMSC | LP + IV | 1-72 months | NA | UBMSC + con | Con | 60.8±15.2

(mean) | 59.2±13.8

(mean) | 0.25, 1, 3 | FMA; FIM | Fever; dizziness

and headache; backache | (26) |

| Liu et al,

2014 | BMSC | LP | 1-21 days | 20~40 | BMSC + con | Con | 55.3±3.6

(mean) | 56.8±4.3

(mean) | 1 and 3 FMA | NIHSS; | No adverse

effects | (23) |

| Feng et al,

2014 | UBMSC | 20 LP; 30 IV | 14-30 days | 30 | UBMSC + con | Con | 61.4±11.3

(mean) | 60.2±11.8

(mean) | 1, 2, 3 s | NIHSS; FMA | Fever | (24) |

| Wang et al,

2013 | UBMSC | IV | Not reported | 7~10 | UBMSC + con | Con | 62.6±7.1

(mean) | 62.2±6.3

(mean) | 0.5 | FMA | No adverse

effects | (25) |

| Chen et al,

2012 | BMSC | LP | 1-12 months | 14 | BMSC + con | Con | 49.3±20.8

(mean) | 57.3±9.5

(mean) | 6 | NIHSS | Fever;

headache | (28) |

| Chen WD et

al, 2012 | BMSC | LP + IV | Not reported | Not reported | BMSC + con | Con | 45.9±10.9

(mean) | 45.9±10.9

(mean) | 1, 3, 5 | FMA; FIM | No adverse

effects | (29) |

| Meng et al,

2009 | BMSC | IV | 42 days | Not reported | BMSC + con | Con | 52.7±7.9

(mean) | 52.9±8.3

(mean) | 1 month, 3 and

6 | FMA; FIM | Fever;

headache | (30) |

| He et al,

2012 | BMSC | IV | Not reported | Not reported | BMSC + con | Con | 56.4±7.9 | 54.3±8.7

(mean) | 3 | NIHSS; BI | Not reported | (27) |

| Fang et al,

2019 | BMSC | IV | 7 days | Not reported | BMSC | Pbo | 49.4±10.8

(mean) | 52.8±14.9

(mean) | 3, 6, 12 48 | NIHSS; BI; mRS | No adverse

effects | (13) |

| Chung et al,

2021 | BMSC | IV | 5-89 days | NA | BMSC + con | Con | 63.0±14.3

(mean) | 64.2±13.2 | 3 months | mRS | No adverse

effects | (12) |

| Hess et al,

2017 | BMSC | IV | 1-2 days | 1h | BMSC | Pbo | 61.8 (median) | 62.6 (medin) | 12 | NIHSS; BI; mRS | Halitosis; fever,

and nausea vomiting | (18) |

| Prasad et

al, 2014 | BMSC | IV | 7-30 days | NA | BMSC + con | Con | 50.7±11.6

(mean) | 52.5±12.1

(mean) | 12 | NIHSS; BI; mRS | Epilepsy | (22) |

| Jin et al,

2017 | BMSC | LP | Not reported | NA | BMSC + con | Con | 50.8±17.4

(mean) | 53.1±13.0

(mean) | 84 | NIHSS; BI; FMA;

FIM; mRS | Fever | (17) |

| Bhatla et

al, 2018 | BMSC | IA | 0-14 days | 10 min | BMSC + con | Con | 57.0±12.2

(mean) | 66.0±7.3

(mean) | 6 | NIHSS; mRS | No adverse

effects | (16) |

Outcome measures of the included

studies

Among outcome indicators, the data successfully

extracted for the BI (18) and mRS

(13) indicators were insufficient,

each corresponding to only one study, therefore these were not

analyzed. The outcome indicators included in the analysis of this

study are NIHSS, FMA, and FIM. All included studies used NIHSS to

assess the degree of neurological deficit. The NIHSS score ranges

from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating more severe

neurological deficit. All included studies used FMA to assess motor

function recovery. The total FMA score ranges from 0 to 100, with

higher scores indicating better motor function. FIM was used in all

studies to assess functional independence. The FIM score ranges

from 18 to 126 points, with higher scores indicating better

functional independence. Assessment time points include baseline

and post-treatment. NIHSS, FMA and FIM score data were extracted by

two independent investigators.

Risk of bias of included studies

The included studies were randomized controlled

trials, and the risk of bias of the included studies was primarily

due to blinding after randomization (Fig. 2).

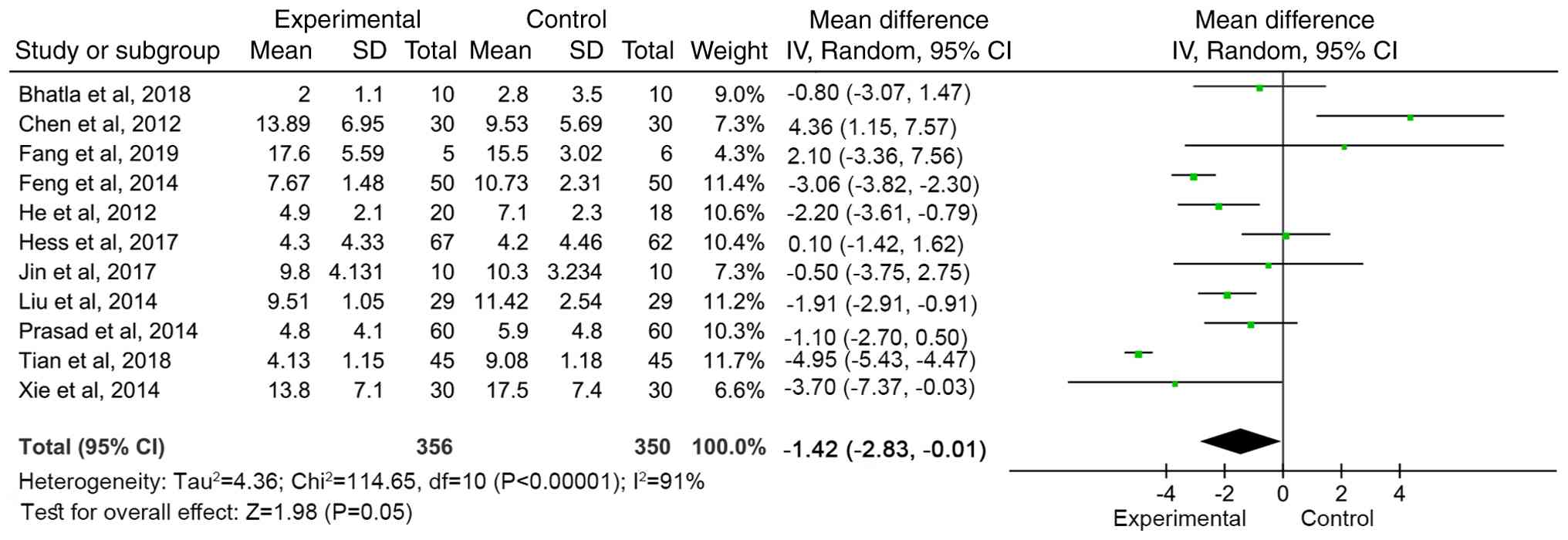

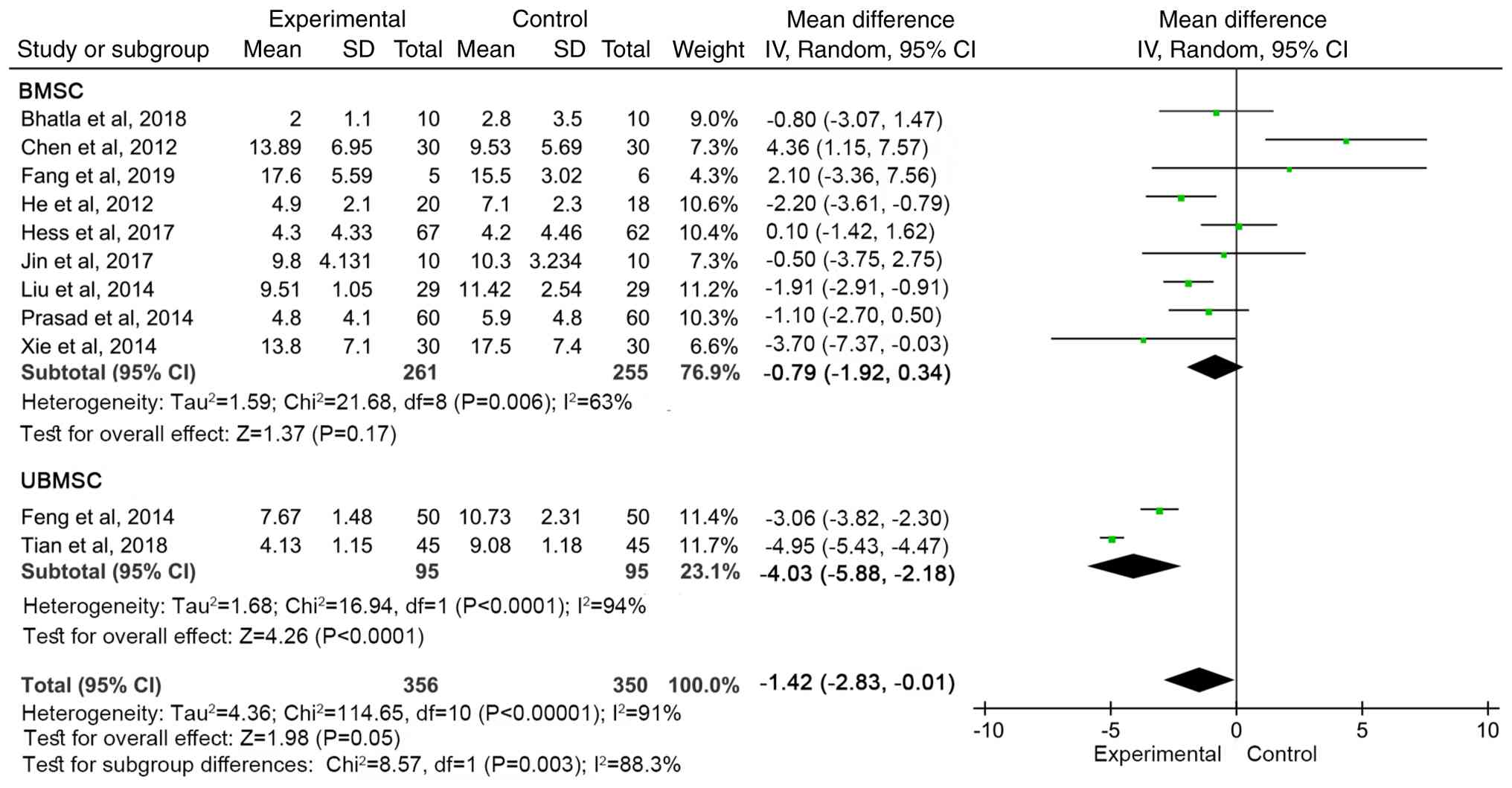

Meta-analysis of NIHSS score

A total of 11 articles (13,14,16-18,20,22,24,27,28)

reported the NIHSS scores of neurological deficit in patients

before and after treatment. The qualitative test

(I2=91%, P<00001) showed heterogeneity, so a random

effects model was used for meta-analysis. The combined effect size

[Weighted Mean Difference WMD=-1.42 (95%CI: -2.83 to -0.01, Z=1.98,

P=0.05)] demonstrated the NIHSS score of the MSC treatment group

was significantly lower than that of the control group, indicating

that MSC therapy decreased the degree of neurological deficit of

patients and had a positive effect on improving the neurological

function of patients (Fig. 3).

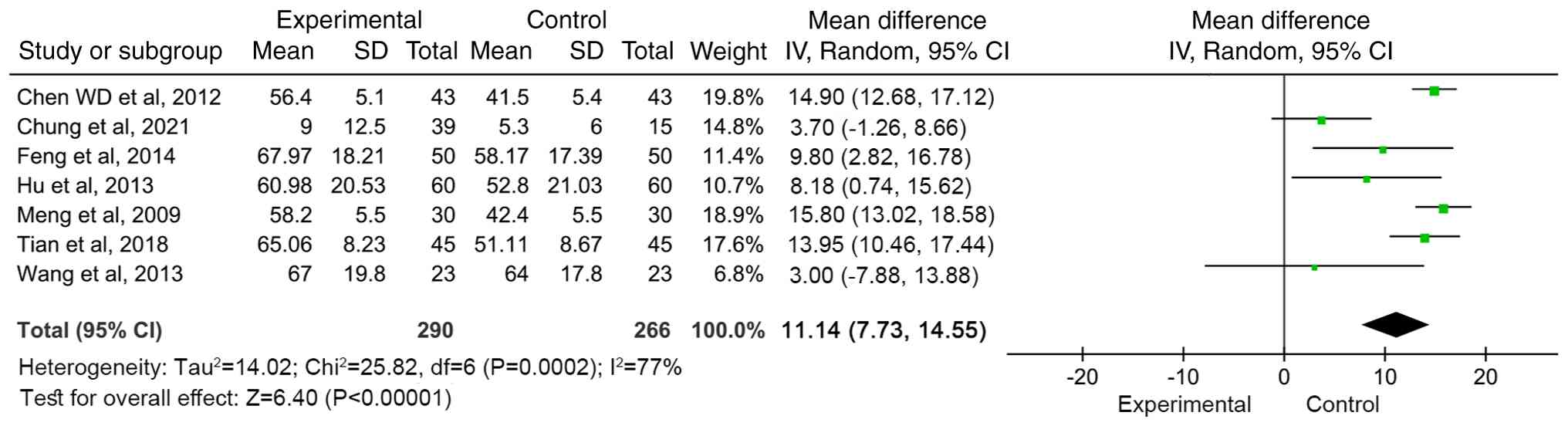

Meta-analysis of motor function score

(FMA)

A total of seven articles (12,14,24,26,29,30)

reported the motor function scores before and after treatment. The

results were heterogeneous (I2=77%, P=0.0002), so a

random effects model was used for meta-analysis. The combined

effect size [WMD=11.14 (95%CI: 7.73-14.55, Z=6.40; P<0.00001)]

indicated that compared with conventional treatment, MSC treatment

significantly improved motor function scores (Fig. 4).

Meta-analysis of functional

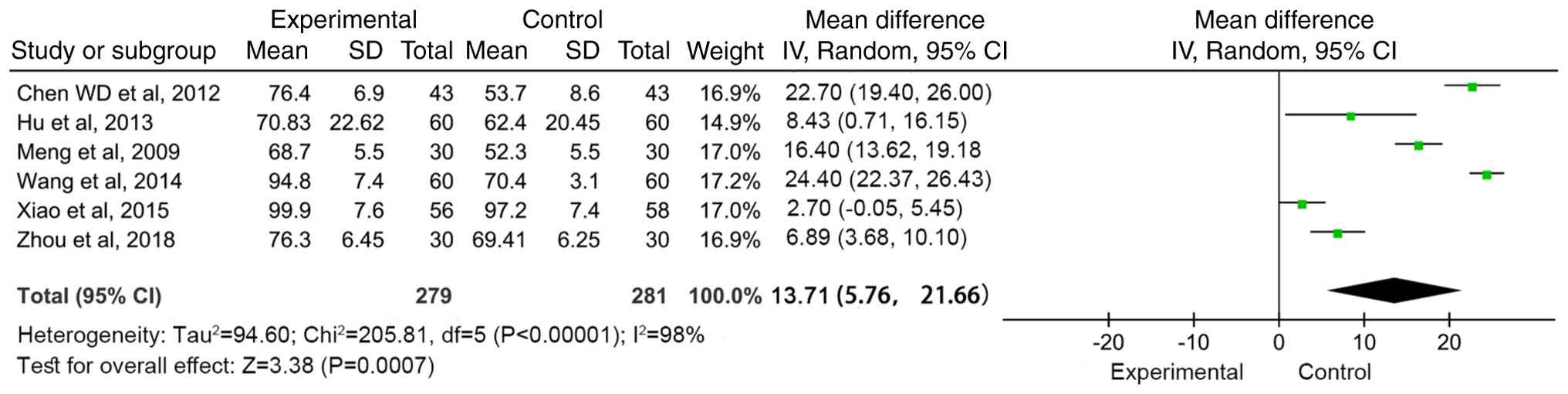

independence score (FIM)

A total of six articles (15,19,21,26,29,30)

reported the functional independence score before and after

treatment. The results were heterogeneous (I2=98%,

P<0.00001), so a random effects model was used for

meta-analysis. The combined effect size [WMD=13.71 (95%CI:

5.76-21.66, Z=3.38; P=0.0007)] indicated that compared with

conventional treatment, MSC treatment significantly improved the

functional independence score (Fig.

5).

Subgroup analysis

For the primary outcome, NIHSS, subgroup analyses

were performed based on cell type, transplantation modality and

follow-up time. In addition, among the 11 studies (13,14,16-18,20,22,24,27,28)

with outcomes including NIHSS, bone marrow MSCs were all autologous

[Hess et al (18) did not

mention the source]. The number of cells was

3.0-5.0x106/kg (28),

5x106/kg (Fang et al, 2019) (13), 1x107/kg (Liu et

al) (23), and not mentioned in

the remaining studies. In research on umbilical cord MSCs, one

study indicated that the source of the cells was Shenzhen Baker

Biotechnology Co., Ltd., with a cell count of 3x107/kg

(24), while another study

(14) did not mention the source or

quantity of the cells.

The improvement in NIHSS was more significant in the

UBMSC group (WMD=-4.03, 95% CI: -5.88 to -2.18, P<0.0001), while

the effect was weaker in the BMSC group (WMD=-0.79, 95% CI: -1.92

to 0.34, P=0.17; Fig. 6). There was

a significant difference between the groups (P=0.05).

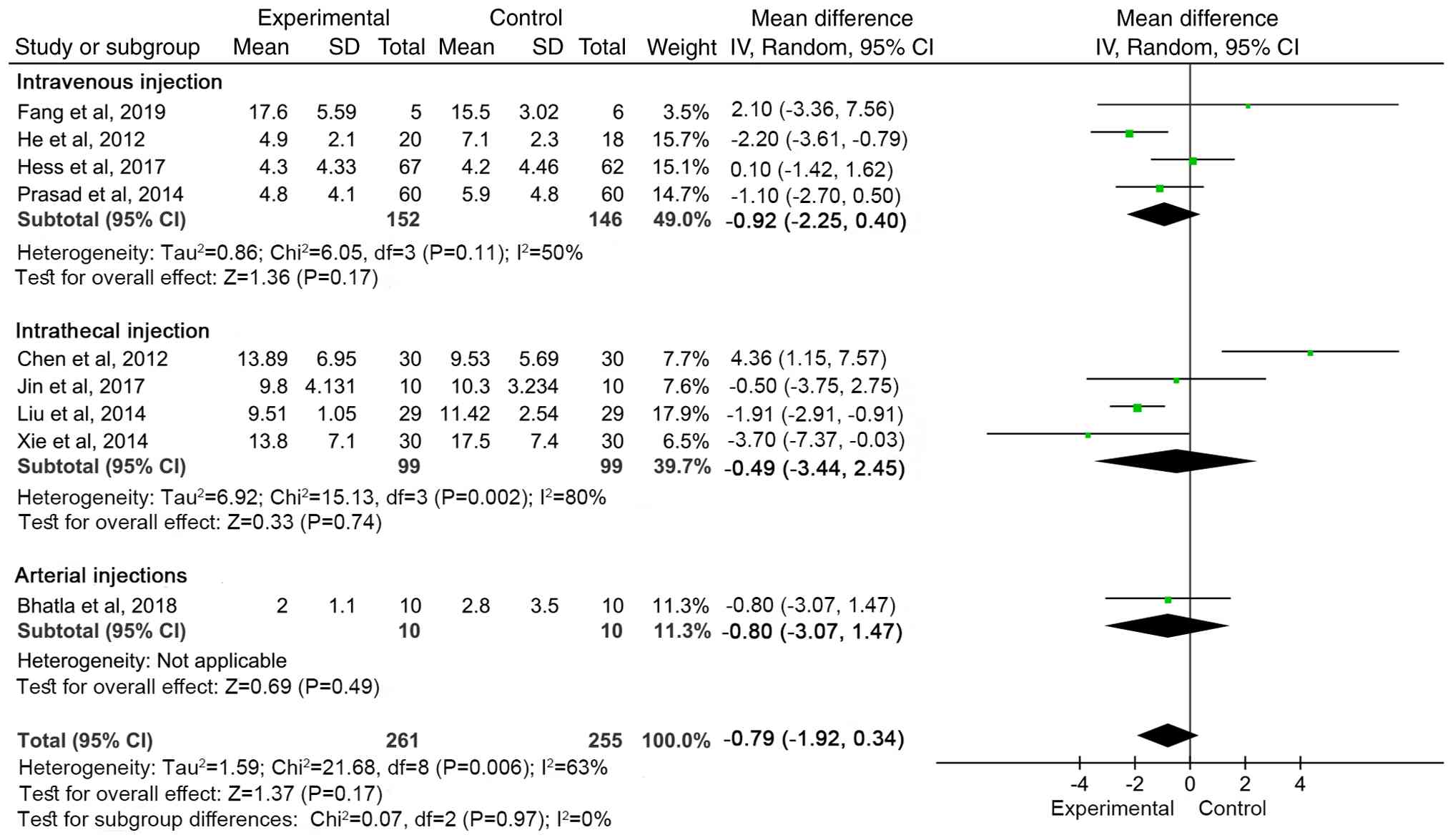

There was no significant difference in NIHSS between

the groups based on transplantation method (total effect size

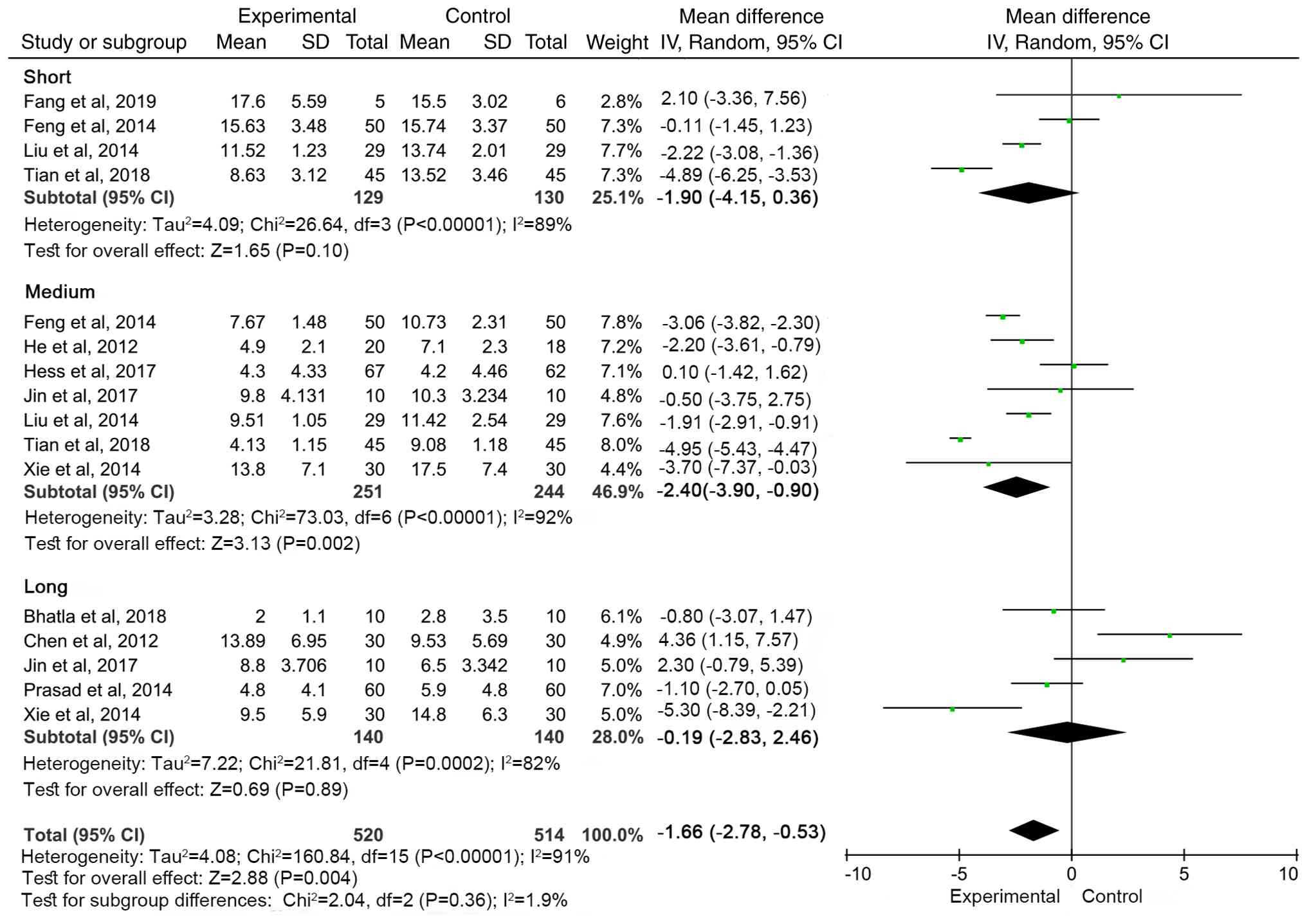

P=0.17; Fig. 7). Follow-up period

was divided as follows: Short-term, <3 months; medium-term, 3-6

months and long-term, >6 months. The MSC group showed the most

significant improvement in NIHSS scores at 3-6 months follow-up

(WMD=-2.40, 95% CI: -3.90 to -0.90, P=0.002). There was no

significant difference between the treatment and control groups

during short- and long-term follow-up (Fig. 8).

Safety analysis

A total of nine studies (15,17,18,20,22,24,26,28,30)

reported adverse effects such as low-grade fever, dizziness,

headache, backache, depression, urinary and respiratory tract

infection and rash; seven studies (12,13,16,21,23,25,29)

reported no adverse reactions, and three studies (14,19,27)

did not mention adverse reactions.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the impact of studies at high risk of bias

on the results of meta-analysis, sensitivity analyses were

performed and excluded the only study with a high risk of bias

(Tian et al) (14).

Heterogeneity was significantly reduced after exclusion of the

aforementioned study (I², 91 vs. 75%), and the overall effect size

changed from -1.42 (95% CI: -2.83 to -0.01, Z=1.98, P=0.05) to

-1.11 (95%CI: -2.22 to 0.01, Z=1.94, P=0.05). Although there was a

slight change in the effect size, there was no notable change in

its direction and significance, indicating that the results of the

meta-analysis were robust.

Publication bias analysis

Funnel plots were used to test the publication bias

of the primary outcome, NIHSS (Fig.

9). Funnel plots showed notable asymmetry, suggesting some

publication bias. For more robust analysis of publication bias,

Egger's test was performed for NIHSS, which showed no significant

publication bias (P=0.461).

Discussion

MSCs originate from tissue such as bone marrow,

adipose tissue and umbilical cord. Bone marrow MSCs have relative

ease of procurement. Nevertheless, as the donor age advances, the

proliferative, self-renewal and differentiation capabilities of

bone marrow MSCs decrease, thereby giving rise to disparities in

the efficacy of SC treatment (31,32).

By contrast, adipose and umbilical cord MSCs are not subject to

such constraints. Umbilical cord MSCs exhibit the advantages of

rapid proliferation and high differentiation potential (33,34).

Cortical MSCs are derived from cortical bone. They have a stronger

ability to differentiate into osteoblasts. They are mainly used in

bone regeneration and orthopedics. Compared with bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cells, research on cortical MSCs is relatively

limited (35,36). MSCs have demonstrated potential in

the treatment of a number of diseases, including ischemic cerebral

infarction, myocardial ischemia, multiple sclerosis, idiopathic

pulmonary fibrosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,

osteoarthritis, acute kidney injury and inflammatory bowel disease

(37). SC therapy serves multiple

roles in ischemic cerebral infarction, such as neural repair,

vascular regeneration, anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic

effects. MSCs traverse the blood-brain barrier to reach the

ischemic regions of the brain (38). They serve a number of functions such

as mitigating inflammatory responses, substituting for nerve cells

that have undergone ischemic apoptosis, secreting neurotrophic

factors, facilitating the repair of blood vessels within the brain

and diminishing cell apoptosis (28-32,39-43).

Compared with traditional treatment, MSCs improve the symptoms of

neurological deficit and ability to perform daily living

activities. The present study have shown that patients treated with

MSCs have better recovery of limb motor and language function than

those treated with conventional treatment. However, its

effectiveness is affected by a variety of factors, such as the

source of the cell, the mode of administration and the timing of

treatment.

Although one study demonstrated high risk of bias

(14), sensitivity analyses

suggested a limited effect on the overall results. Future studies

should focus on the implementation of randomization procedures,

allocation concealment and blinding to improve the quality of

studies.

In clinical trials, NIHSS, FMA, and FIM are commonly

used to assess cerebral infarction (6-8).

The present study showed that MSC therapy could improve FMA score

and FIM score. The NIHSS score results show that the effect sizes

of Chen et al (28) and Fang

et al's study (13) are both

located to the right of the null line in the forest plot, which has

a certain impact on the combined effect results. For Chen et

al's study (28), the abnormal

effect size may be due to differences in the NIHSS scoring method

and the culture conditions of mesenchymal stem cells; for Fang

et al's study (13), it is

considered to be caused by the small sample size. After excluding

the study with the greatest impact on the results (Chen et

al) (28), the pooled effect

size WMD=-1.91 (95%CI: -3.25 to -0.57, Z=2.79, P=0.005). This meant

that the MSC treatment group demonstrated lower NIHSS score than

the control group, indicating that MSC therapy can reduce the

degree of neurological deficit and have a positive effect on

improving the neurological function of patients. Sensitivity

analysis suggested that the Tian et al (14) may be one of the main sources of

heterogeneity. Heterogeneity was significantly decreased after the

study was excluded, but the overall effect size remained

significant, supporting the positive effect of MSC treatment in

patients with cerebral infarction. However, the presence of high

heterogeneity suggests that future studies should focus on

standardised patient selection, intervention and follow-up time to

reduce heterogeneity and improve the reliability of results. In

conclusion, MSC transplantation can improve neurological and motor

function in patients with ischemic cerebral infarction. This

heterogeneity may be due to differences in patient characteristics,

SC source and treatments, details of interventions, and length of

follow-up between studies.

Among the studies included, nine reported adverse

reactions (15,17,18,20,22,24,26,28,30).

The adverse reactions included low-grade fever, dizziness,

headache, back pain, depression, urinary and respiratory tract

infections, and rash, all of which resolved spontaneously or after

treatment. The most common adverse reactions were fever and

headache, and there were no serious adverse reactions such as to

tumorigenicity or toxicity. MSCs have a high safety profile in the

treatment of cerebral infarction. However, in the future, it is

necessary to continue to pay attention to the potential risks, such

as abnormal cell proliferation and immune-related problems. Safety

of MSCs from different sources, preparation processes and

administration methods may vary, which needs to monitored and

evaluated in clinical applications.

Among the 11 studies included that involved NIHSS

scores (13,14,16-18,20,22,24,27,28),

six fell outside the 95% confidence interval of the funnel plot

(14,16,22-24,29),

which may be attributed to heterogeneity among the studies and

differences in sample sizes. Small-sample studies are prone to

large sampling errors, leading to significant fluctuations in

effect size estimates, exacerbating differences between results

from small- and large-sample studies and increasing overall

heterogeneity, thereby causing funnel plot asymmetry. Additionally,

small-sample studies are more likely to yield negative results,

while journals tend to publish positive findings, which further

contributes to publication bias. and MSCs from bone marrow are the

most widely used. Lumbar puncture, the method of obtaining cells,

is an invasive operation, which not only causes pain and infection

risk to patients, but also raises the threshold for clinical

development. MSCs derived from the umbilical cord are easy to

obtain and have high proliferative and differentiation

capabilities. Unlike bone marrow-derived MSCs, those from the

umbilical cord do not require a bone marrow puncture, avoiding

invasive procedures. Due to the lack of clinical studies using

umbilical cord MSCs, more research is needed in the future to

determine the optimal source of MSCs. Due to the complexity and

heterogeneity of the studies, it was not possible to draw

definitive conclusions. Due to limited data and different

transplantation routes, it was difficult for each subgroup sample

to fully represent the overall characteristics, which may interfere

with the effect estimation and weaken the reliability of the

results.

MSCs are transplanted in a variety of ways,

including stereotactic implantation or craniotomy for direct

injection into the brain parenchyma, intravenous infusion and

arterial and transarachnoid injection (4,5,40,43).

The most common method of transplantation is intravenous infusion.

Compared with intracerebral injection, intravenous infusion is

simpler to perform, carries lower risk, involves less invasiveness

and avoids damage to normal brain tissue caused by direct

injection. However, some studies have shown that intravenous

administration can reduce efficacy to some extent (5). Cells need to pass through the systemic

circulation and blood-brain barrier to reach the brain. Directed

transplantation in the brain is most effective, but normal brain

tissue may be damaged during implantation (4). Craniotomy is generally not accepted by

patients. Intrathecal injection has been used to inject stem cell

suspension into the subarachnoid space through lumbar puncture, so

SCs can circulate with cerebrospinal fluid to the surface of the

brain. This method has the advantage of being minimally invasive

and can partially overcome the physiological limitations of the

blood-brain barrier, allowing the cells to be closer to central

nervous system targets; lumbar puncture has a low probability of

infection and the risk of cerebrospinal fluid leakage; therefore,

clinical use needs to balance the benefits and safety (44). The present study found no

significant differences between intravenous infusion, arterial

injection and intrathecal injection. In clinical studies, the

design of transplantation modalities is highly heterogeneous, such

as the number of cells transplanted and whether cerebrospinal fluid

is replaced by intrathecal injection, and the number of included

studies is small, which may affect the results. More research is

needed in the future to compare the efficacy of transplantation

methods. This may be due to the small number of included studies

and the inconsistency in the design of transplantation modalities.

More research is needed to determine the optimal transplantation

modality.

The efficacy of MSCs varies depending on the length

of follow-up. MSCs may exert neuroprotective effects in the early

stages because of their ability to combat toxic and inflammatory

responses. The present study demonstrated MSC therapy improved

NIHSS score more than conventional therapy during the medium-term

follow-up period, and there was no significant difference between

the treatment and control groups during the short- and long-term

follow-up. However, the high degree of heterogeneity between

studies limits the generalizability of the results. However, the

high degree of heterogeneity between studies limits the

generalizability of the results. Future studies should standardize

MSC treatment regimens, patient selection criteria and outcome

measures to decrease heterogeneity and provide more reliable

evidence. Due to incomplete data, subgroup analyses were not

performed for age, cerebral infarction severity and duration of

cell transplantation.

The present study did not conduct subgroup analysis

by age because most of the patients were aged 50-60 years. It was

not possible to assess the severity of cerebral infarction due to

incomplete data. It was difficult to analyze the differences in

treatment outcomes between different transplantation times, as only

two studies (16,18) accurately recorded the timing of cell

transplantation. The time of cerebral infarction onset in patients

ranged from 1-2 days to 1-12 months. Patients with cerebral

infarction onset of 1-12 months include those with onset of 1-2

days. However, we cannot obtain more detailed timing data from each

study, so we are unable to perform subgroup analysis based on the

duration since cerebral infarction onset. Due to the scarcity of

data, the present study did not further analyze the source of cells

and the number of cells transplanted.

The present study had limitations. Only six

databases were searched, and the included articles were in Chinese

and English, which presents risk of bias. Second, most studies did

not have placebo-controlled trials, did not blind participants and

treatment regimens and did not report allocation concealment.

Although studies were consistent in terms of participants,

intervention and outcome measures, providing a relatively

homogeneous basis for subsequent meta-analysis, there may still be

differences in terms of patient characteristics, SC-related

treatments, SC transplant dose and follow-up time, resulting in

heterogeneity in subsequent analyses. Additionally, the literature

search for this study has certain limitations. Some of the included

studies, particularly those published in Chinese, are not indexed

in common international databases but can be accessed through

specialized Chinese academic databases. This may affect the

accessibility of this portion of the evidence for non-Chinese

researchers, however these studies are available upon request. To

assess the efficacy and safety of MSCs in the treatment of cerebral

infarction, more high-quality studies are needed, including

large-sample, multicenter randomized controlled trials that follow

scientific norms to minimize the impact of publication bias.

In conclusion, MSC transplantation can improve the

neurological function and motor function of patients with ischemic

cerebral infarction and the safety is high. Due to the small sample

size of the included studies, the quality of the articles was not

high and there was a risk of bias. Therefore, in the future,

large-sample, multi-center and rigorously designed clinical trials

are needed to validate the present data.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding: The present study was supported by Scientific Research

Fund of Jiangxi Provincial Education Department (grant no.

GJJ190802), Ganzhou Science and Technology Innovation Talent Plan

(grant no. 202101094460), The Open Project of Key Laboratory of

Prevention and Treatment of Cardiovascular and Cerebrovascular

Diseases of Educational Ministry in Gannan Medical University

(grant no. XN202011), Graduate Innovation Project of Hunan

University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant nos. 2024CX132,

2025CX189 and 2025CX196) and Natural Science Foundation of Hu Nan

Province (grant nos. 2023JJ30362 and 2025JJ40099).

Availability of data and materials

The data generated in the present study, and studies

cited which are published in Chinese may be requested from the

corresponding author.

Authors' contributions

YJ, QC, YY, YX, XH and YL wrote the manuscript. YJ,

QC and YY performed the literature review. YL and XH collected the

data. YJ and YL confirm the authenticity of all the raw data, YJ,

YX and XH analyzed the data. YL and QC designed the study and

reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the

final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

Jiang Y, Li XY, Hu N, Huang ZJ and Wu F:

Epidemiologic characteristics of cerebrovascular disease mortality

in China, 2004-2005. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi. 44:293–297.

2010.PubMed/NCBI(In Chinese).

|

|

2

|

Chen Y, Gu SL and Wang QQ: Status quo and

influencing factors of quality of life in elderly patients with

acute ischemic stroke hemiplegia after discharge. Chin J Mult Organ

Dis Elderly. 23:194–197. 2024.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7111730250&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

3

|

Li Y, Hu G and Cheng Q: Implantation of

human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for ischemic stroke:

Perspectives and challenges. Front Med. 9:20–29. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

4

|

Banerjee S, Williamson DA, Habib N and

Chataway J: The potential benefit of stem cell therapy after

stroke: An update. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 8:569–580.

2012.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

5

|

Kuroda S: Current opinion of bone marrow

stromal cell transplantation for ischemic stroke. Neurol Med Chir

(Tokyo). 56:293–301. 2016.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

6

|

Goldstein LB and Samsa GP: Reliability of

the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. Extension to

non-neurologists in the context of a clinical trial. Stroke.

28:307–310. 1997.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7

|

Fugl-Meyer AR, Jääskö L, Leyman I, Olsson

S and Steglind S: The post-stroke hemiplegic patient. 1. a method

for evaluation of physical performance. Scand J Rehabil Med.

7:13–31. 1975.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Granger CV, Cotter AC, Hamilton BB and

Fiedler RC: Functional assessment scales: A study of persons after

stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 74:133–138. 1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Hopman-Rock M, van Hirtum H, de Vreede P

and Freiberger E: Activities of daily living in older

community-dwelling persons: A systematic review of psychometric

properties of instruments. Aging Clin Exp Res. 31:917–925.

2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

10

|

Saver JL, Chaisinanunkul N, Campbell BCV,

Grotta JC, Hill MD, Khatri P, Landen J, Lansberg MG,

Venkatasubramanian C and Albers GW: XIth Stroke Treatment Academic

Industry Roundtable. Standardized nomenclature for modified rankin

scale global disability outcomes: Consensus recommendations from

stroke therapy academic industry roundtable XI. Stroke.

52:3054–3062. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

11

|

Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni

P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA, et

al: The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in

randomised trials. BMJ. 343(d5928)2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

12

|

Chung JW, Chang WH, Bang OY, Moon GJ, Kim

SJ, Kim SK, Lee JS, Sohn SI and Kim YH: STARTING-2 Collaborators.

Efficacy and safety of intravenous mesenchymal stem cells for

ischemic stroke. Neurology. 96:e1012–e1023. 2021.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13

|

Fang J, Guo Y, Tan S, Li Z, Xie H, Chen P,

Wang K, He Z, He P, Ke Y, et al: Autologous endothelial progenitor

cells transplantation for acute ischemic stroke: A 4-year follow-up

study. Stem Cells Transl Med. 8:14–21. 2019.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

14

|

Tian LP, Wang JJ and Zhao KL: Observation

of the clinical effect of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal

stem cells in the treatment of cerebral infarction. Chin J Clin

Ration Drug Use. 11:109–110. 2018.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=676508155.

|

|

15

|

Zhou J: Clinical efficacy of cord blood

stem cell transplantation in improving functional independence in

stroke patients. Neural Inj Funct Reconstr. 13:42–43. 2018.(In

Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=7000552239&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

16

|

Bhatia V, Gupta V, Khurana D, Sharma RR

and Khandelwal N: Randomized Assessment of the safety and efficacy

of intra-arterial infusion of autologous stem cells in subacute

ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 39:899–904. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Jin Y, Ying L, Yu G and Nan G: Analysis of

the long-term effect of bone marrow mononuclear cell

transplantation for the treatment of cerebral infarction. Int J

Clin Exp Med. 10:3059–3068. 2017.

|

|

18

|

Hess DC, Wechsler LR, Clark WM, Savitz SI,

Ford GA, Chiu D, Yavagal DR, Uchino K, Liebeskind DS, Auchus AP, et

al: Safety and efficacy of multipotent adult progenitor cells in

acute ischaemic stroke (MASTERS): A randomised, double-blind,

placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol. 16:360–368.

2017.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Xiao HX: Clinical efficacy of stem cell

transplantation in stroke. Medical Recapitulate. 21:1875–1876.

2015.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=665002239.

|

|

20

|

Xie XF, Liu SY, Jin GH, Qu XH, Zhang KN

and Wu XM: Clinical analysis of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cell transplantation for treatment of cerebral infarction. Lab

Med Clin. 11:2955–2957. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

21

|

Wang X, Zhang Z, Jia FR and Yang H: A

clinical study on treatment of cerebral infarction using autologous

marrow mesenchymal stem cells intervening transplantation. Jilin

Med. 35:237–239. 2014.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=48441187&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

22

|

Prasad K, Sharma A, Garg A, Mohanty S,

Bhatnagar S, Johri S, Singh KK, Nair V, Sarkar RS, Gorthi SP, et

al: Intravenous autologous bone marrow mononuclear stem cell

therapy for ischemic stroke: A multicentric, randomized trial.

Stroke. 45:3618–3624. 2014.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

23

|

Liu DH, Han BJ, Hong SS, Wang QG, Du CY,

Gao H, Han LX, Wan MR and Ye Y: Transplanting autologous

mesenchymal nerve stem cells in the treatment of cerebral

infarction. Chin J Phys Med Rehabil. 36:425–428. 2014.(In Chinese).

https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=50201705&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

24

|

Feng TG, Li L and Zhou J: Clinical

efficacy study of human umbilical cord blood mesenchymal stem cells

in the treatment of cerebral infarction. PJCCPVD. 22:28–30.

2014.

|

|

25

|

Wang XH, Wang SP, Xu GX, Ma SB, Wang T and

Zou SF: Short-term efficacy of umbilical cord blood nucleated cells

in treatment of cerebral infarction sequelae. Transl Med J.

2:332–335. 2013.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=48118583&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

26

|

Hu Q, Cao MY, Li RF, Jiang HW and Ge LT:

Safety and efficacy on the treatment of cerebral infarction with

umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Med J Wuhan Univ. 34:57–70.

2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar : (In Chinese).

https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=44536233&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

27

|

He ZD: Study on the mechanism of bone

marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation to improve

neurological function in patients with cerebral infarctionf.

Asia-Pacific Tradit Med. 8:126–127. 2012.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=44178016&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

28

|

Chen WM, Zou QY, Lu JJ, Hu YX, Hu QL, Li

ZG and Zeng ZL: Reinfusion of autologous bone marrow mesenchymal

stem cells for treatment of stroke in 30 cases. Chin J Tissue Eng

Res. 16:6071–6075. 2012.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=43200003&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

29

|

Chen WD, Li JT, Zhang XB, Zhao H, Li W,

Yang SQ, Lu GZ, Li D and He L: Clinical analysis of bone marrow

mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for cerebral infarction.

Jilin Med. 33(4522)2012.(In Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=42844101&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

30

|

Meng XG, Zhu SW, Gao H, Li YZ, Shi Q, Hou

HS and Li D: Treatment of cerebral infarction using autologous

marrow mesenchymal stem cells transplantation:A six-month

follow-up. J Clin Rehabil Tissue Eng Res. 13:6374–6378. 2009.(In

Chinese). https://qikan.cqvip.com/Qikan/Article/Detail?id=31368833&from=Qikan_Search_Index.

|

|

31

|

Wen YL, Yun JC, Phil HL, Huh K, Kang YM,

Kim HS, Ahn YH, Lee G and Bang OY: Mesenchymal stem cells for

ischemic stroke: Changes in effects after ex vivo culturing. Cell

Transplant. 17:1045–1059. 2008.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

32

|

Bonab MM, Alimoghaddam K, Talebian F,

Ghaffari SH, Ghavamzadeh A and Nikbin B: Aging of mesenchymal stem

cell in vitro. BMC Cell Biol. 7(14)2006.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

33

|

Lin YC, Ko TL, Shih YH, Lin MY, Fu TW,

Hsiao HS, Hsu JY and Fu YS: Human umbilical mesenchymal stem cells

promote recovery after ischemic stroke. Stroke. 42:2045–2053.

2011.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Hsieh JY, Wang HW, Chang SJ, Liao KH, Lee

IH, Lin WS, Wu CH, Lin WY and Cheng SM: Mesenchymal stem cells from

human umbilical cord express preferentially secreted factors

related to neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis. PLoS

One. 8(e72604)2013.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Wang Q, Huang C, Zeng F, Xue M and Zhang

X: Activation of the Hh pathway in periosteum-derived mesenchymal

stem cells induces bone formation in vivo: Implication for

postnatal bone repair. Am J Pathol. 177:3100–3111. 2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

36

|

Fernandez-Moure JS, Corradetti B, Chan P,

Van Eps JL, Janecek T, Rameshwar P, Weiner BK and Tasciotti E:

Enhanced osteogenic potential of mesenchymal stem cells from

cortical bone: A comparative analysis. Stem Cell Res Ther.

6(203)2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

37

|

Bateman ME, Strong AL, Gimble JM and

Bunnell BA: Concise review: Using fat to fight disease: A

systematic review of nonhomologous adipose-derived stromal/stem

cell therapies. Stem Cells. 36:1311–1328. 2018.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

38

|

Wang CY, Fei YP, Xu CS, Zhao Y and Pan Y:

Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells ameliorate neurological deficits

and blood-brain barrier dysfunction after intracerebral hemorrhage

in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Int J Clin Exp Pathol.

8:4715–4724. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

39

|

Kim YJ, Park HJ, Lee G, Bang OY, Ahn YH,

Joe E, Kim HO and Lee PH: Neuroprotective effects of human

mesenchymal stem cells on dopaminergic neurons through

anti-inflammatory action. Glia. 57:13–23. 2009.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

40

|

Oh SH, Choi C, Chang DJ, Shin DA, Lee N,

Jeon I, Sung JH, Lee H, Hong KS, Ko JJ and Song J: Early

neuroprotective effect with lack of long-term cell replacement

effect on experimental stroke after intra-arterial transplantation

of adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Cytotherapy.

17:1090–1103. 2015.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

41

|

Leu S, Lin YC, Yuen CM, Yen CH, Kao YH,

Sun CK and Yip HK: Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells markedly

attenuate brain infarct size and improve neurological function in

rats. J Transl Med. 8(63)2010.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

42

|

Ryu B, Sekine H, Homma J, Kobayashi T,

Kobayashi E, Kawamata T and Shimizu T: Allogeneic adipose-derived

mesenchymal stem cell sheet that produces neurological improvement

with angiogenesis and neurogenesis in a rat stroke model. J

Neurosurg. 132:442–455. 2020.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

43

|

Zhou L, Wang J, Huang J, Song X, Wu Y,

Chen X, Tan Y and Yang Q: The role of mesenchymal stem cell

transplantation for ischemic stroke and recent research

developments. Front Neurol. 13(1000777)2022.PubMed/NCBI View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

44

|

Miao X, Wu X and Shi W: Umbilical cord

mesenchymal stem cells in neurological disorders: A clinical study.

Indian J Biochem Biophys. 52:140–146. 2015.PubMed/NCBI

|