Introduction

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a severe inflammatory

disease that accounts for >220,000 hospital admissions in the

United States each year (1).

Although there has been recent progress in the diagnosis and

treatment of AP, the incidence of AP has not decreased and its

serious systemic complications are a worldwide health issue

(2). In certain cases, severe AP

(SAP) may lead to multiple organ failure, and thus the mortality

rate among patients with SAP may approach 30% (3). Therefore, it is crucial to identify

effective early diagnostic markers for AP, and particularly for

SAP. The level of serum amylase is a commonly-used clinical

indicator for the severity of AP; however, this level not

particularly sensitive and it is often difficult to obtain a

pancreatic specimen from patients with AP for pathological analysis

(4,5).

E-cadherin is a calcium-dependent cell-cell adhesion

molecule that has been linked to cancer development and

inflammatory disorders (6,7). During the inflammatory process,

cell-cell contacts tend to dissolve, which permits the unregulated

movement of fluids and electrolytes into the interstitial space,

resulting in tissue edema (8). Once

AP has been initiated, the appearance of inflammatory infiltration

and interstitial edema are common features (9). Therefore, it is hypothesized that the

expression levels of E-cadherin fluctuate during the progression of

AP. The aim of the present study was to establish an animal model

of pancreatitis and evaluate the levels of soluble E-cadherin, in

order to assess its efficacy as a marker of AP severity.

Materials and methods

Pancreatitic animal model and

experimental design

Animal experiments were authorized according to the

Guidance Suggestions for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals

issued by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's

Republic of China, and were approved by the Ethics Committee of the

Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Wuxi Second Hospital (Wuxi,

China). Sprague Dawley (SD) rats were supplied by the Sino-British

SIPPR/BK Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd., (Shanghai, China). Animal

experiments were conducted as described in previous studies

(10,11) at Nanjing Medical University

Affiliated Wuxi No. 2 People's Hospital between June 2013 and July

2014. In brief, 24 healthy adult male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats,

weighing 170±15.5 g, were randomly assigned into two treatment

groups (n=12 per group). In the high concentration L-arginine

(HCLa) group, each SD rat received two intraperitoneal injections

of 20% L-arginine (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai,

China; 2.5 g/kg body weight), at an interval of 1 h. In the low

concentration L-arginine (LCLa) group, each SD rat received two

intraperitoneal injections of 6% L-arginine (2.5 g/kg body weight),

at an interval of 1 h. At 24 h after the induction of pancreatitis

using L-arginine, all SD rats were sacrificed under ether

anesthesia. The pancreas of each rat was then rapidly removed, and

separated from the surrounding lymph nodes and fat. Each pancreatic

tissue sample was divided into two parts: One part was fixed in 10%

buffered formaldehyde for histological evaluation and the second

part was reserved for protein extraction. The severity of the

pancreatitis was determined based on the histological scoring,

including the degrees of edema, inflammation, vacuolization and

necrosis, and by measurement of serum amylase levels. Furthermore,

8 additional rats received intraperitoneal injections of an equal

quantity of 0.9% NaCl solution, and were designated as the control

group.

Histological evaluation

Pancreatic samples were fixed in 10% buffered

formaldehyde, cut into 5 µm sections, and stained with hematoxylin

and eosin (H&E; Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd., Fuzhou, China) and

assessed blindly by two senior pathologists (Qi Pan and Guochang

Chen). The tissue sections were graded as described previously

(12). A total of 10 high-power

fields (HPF) of each section were selected at random and were

visualized under a CX31 microscope (Olympus America Inc., Center

Valley, PA, USA). Samples were scored on a scale of 0–4, according

to the degree of edema, necrosis, vacuolization and inflammation.

The degree of edema was scored as follows: 0, No edema; 1, diffuse

expansion of interlobar septa; 2, severe diffuse expansion of

interlobar septa; 3, diffuse expansion of interacinar septa; and 4,

diffuse expansion of intercellular septa. The degree of

inflammation was scored as follows: 0, No inflammation; 1,

inflammation around ductal margin; 2, inflammation in parenchyma

(<50% of lobules); 3, inflammation in parenchyma (50–75% of

lobules); and 4, inflammation in parenchyma (>75% of lobules).

The degree of vacuolization was scored as follows: 0, No

vacuolization; 1, peroductal vacuolization (<5%); 2, focal

vacuolization (5–20%); 3, diffused vacuolization (21–50%); and 4,

severe vacuolization (>50%). The degree of necrosis was scored

as follows: 0, No necrosis; 1, 1–4 necrotic cells/HPF; 2, 5–10

necrotic cells/HPF; 3, 11–15 necrotic cells/HPF; and 4, >16

necrotic cells/HPF. The final score was calculated as the sum of

the results of all parameters (including degrees of edema,

necrosis, vascularization and inflammation). The final score was

between 0 and 16.

Serum levels of amylase

During the animal experiments, a 2-ml blood sample

was extracted from each rat following anesthetization. The blood

samples were centrifuged at 1,509 × g for 15 min, and stored at

−80°C until further use. The levels of serum amylase were measured

using a Hitachi 7600-020 automatic biochemical analyzer (Hitachi,

Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) (13).

Serum levels of E-cadherin

A 2-ml blood sample was extracted from each rat

following anesthetization. The levels of E-cadherin were measured

using a commercially available MK117 E-cadherin ELISA kit (Takara

Bio, Inc., Otsu, Japan).

Western blot analysis to determine the

expression of E-cadherin protein

Whole cell lysates were prepared from pancreatic

tissue specimens. Briefly, pancreatic tissue samples were

homogenized using a glass-on-glass tissue homogenizer.

Subsequently, the homogenates were centrifuged (10 min, 4°C, 11,750

× g) and the supernatants were collected. Total protein was

extracted using a Qproteome Mammalian Protein Prep kit (Qiagen

GmbH, Hilden, Germany). The levels of E-cadherin protein in the

pancreatic tissue were measured using Coomassie blue staining

(Maixin Biotech Co., Ltd.). A standard western blot assay was

performed using a primary goat polyclonal antibody against rat

E-cadherin (dilution, 1:1,000; catalog no. ab1416; Abcam,

Cambridge, UK) and an anti-goat IgG antibody, which was a

horseradish peroxidase-linked F (ab')2 fragment obtained

from a rabbit (dilution 1:2,000; catalog no. BA1060; Wuhan Boster

Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China). The loading of equal

quantities of protein samples was verified using an anti-β-actin

antibody (dilution, 1:1,000; catalog no. sc-47778; Santa Cruz

Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), with a secondary antibody

(dilution, 1:2,000; cat. no. BA1051; Wuhan Boster Biological

Technology, Ltd.), as a loading control. The proteins under

investigation were detected using the Pierce Enhanced

Chemiluminescence Western Blotting substrate (Thermo Fisher

Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The intensity of the bands was

visualized using an Amersham enhanced chemiluminescence system

(ImageQuant LAS 4000; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA,

USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

software, version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The

experimental values were analyzed using the paired-samples

t-test and were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was calculated to determine

the differences between groups for each parameter at each time

point. Non-parametrical Kruskal-Wallis tests were used when equal

variances were not assumed in one-way ANOVA. P<0.05 was

considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Histological analysis

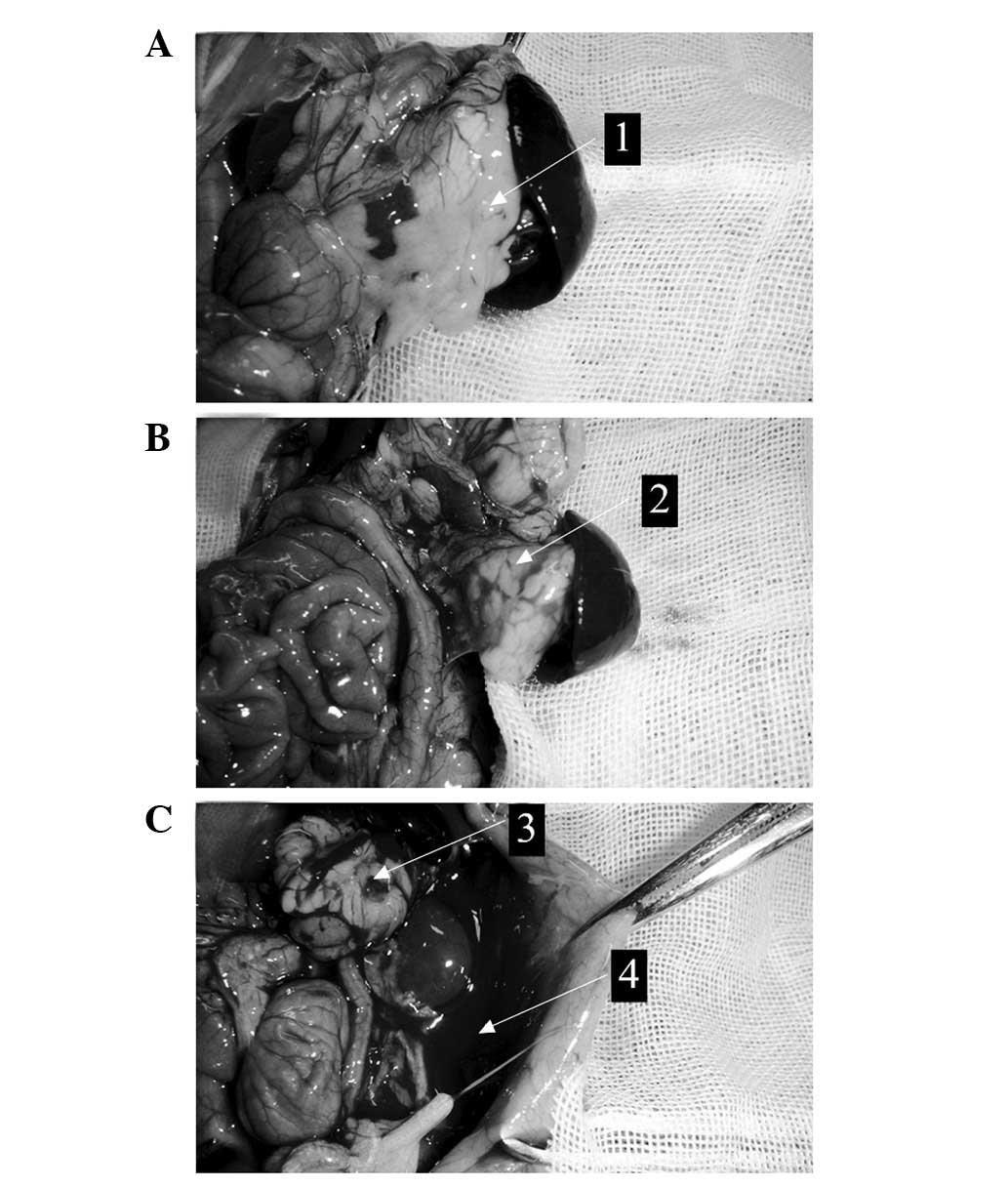

No rats died unexpectedly following the

intraperitoneal injections, and the rats were sacrificed at 24 h

after the injections. In the control group (NaCl-treated), no

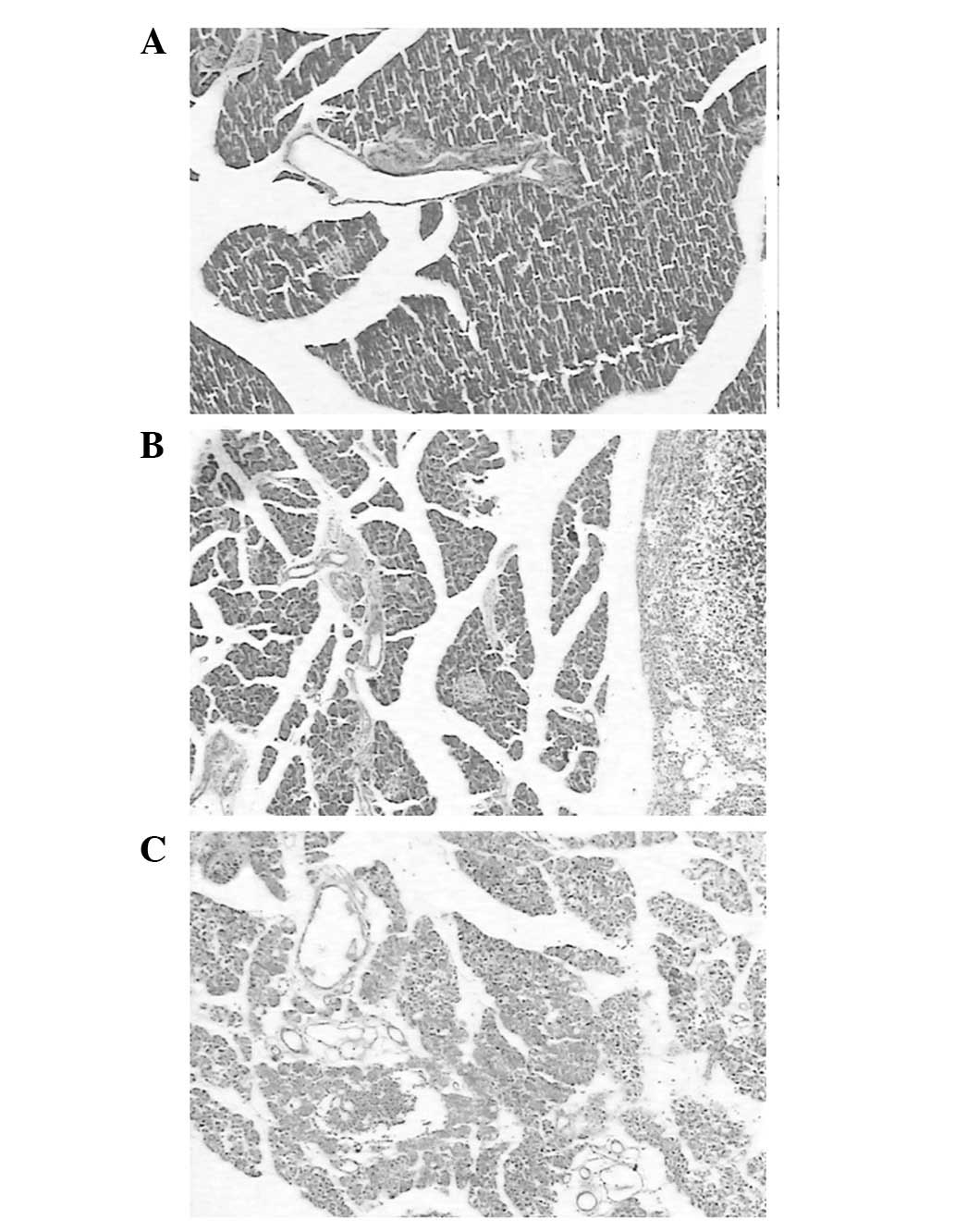

pancreatic edema or peritoneal exudate were detected (Fig. 1A). H&E staining of the control

group pancreatic tissue revealed no significant swelling,

inflammation or necrosis (Fig. 2A).

In the LCLa group, edema of the pancreas and necrosis of the fat

surrounding the pancreas were observed in all rat tissue samples

(Fig. 1B). H&E staining revealed

interlobular edema and inflammatory cell infiltration in the

pancreatic tissue (Fig. 2B). In the

HCLa group, edema, hemorrhage, necrosis of the pancreas and bloody

ascites were observed in all rat tissue samples (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, the destruction of

pancreatic lobules, interstitial edema, vascular congestion and

infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes were observed in the HCLa

group samples (Fig. 2C).

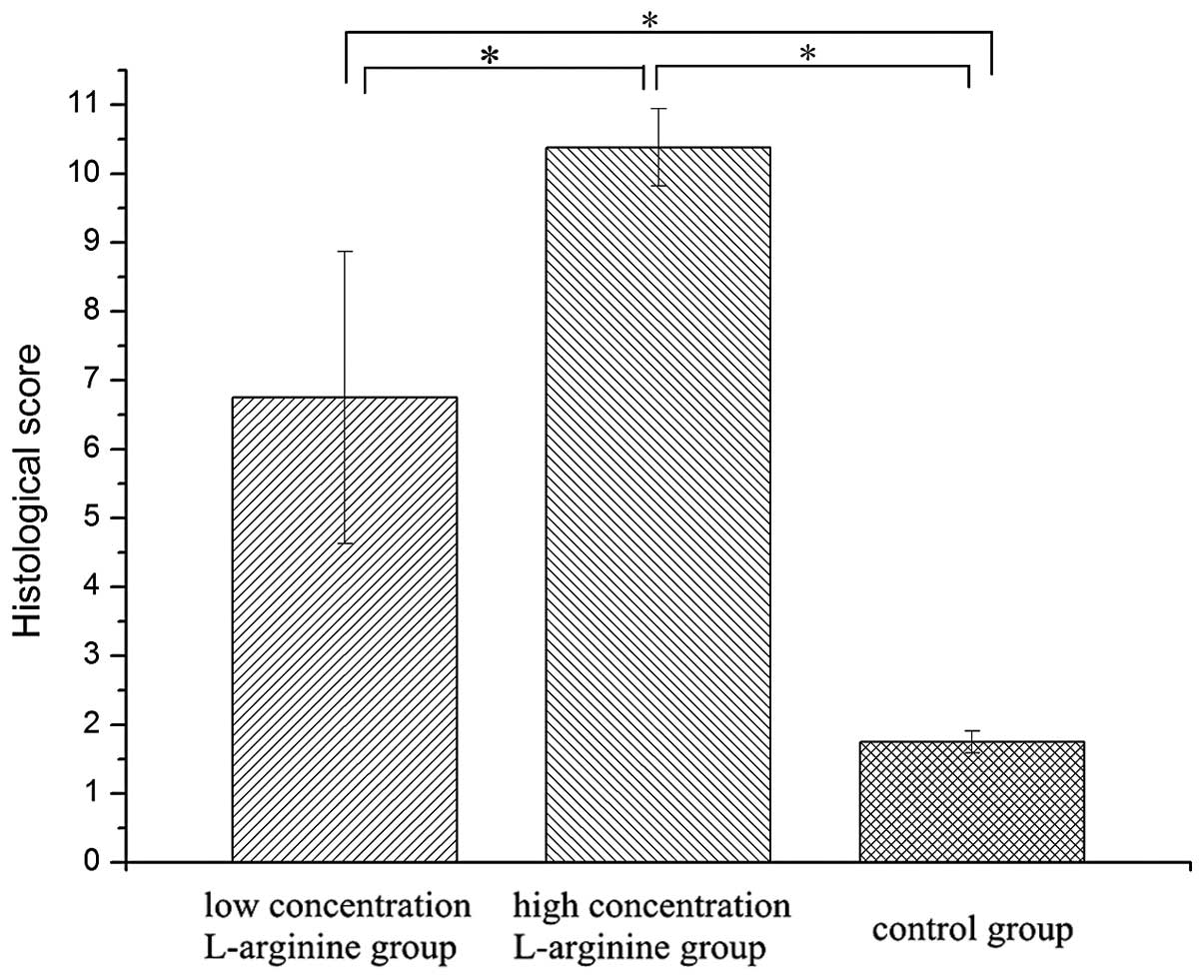

Pathology scores for the HCLa (10.38±0.56) and LCLa

(6.75±2.12) groups were higher compared with the control group

(1.75±0.16). Statistically significant differences were detected in

the HCLa and LCLa groups compared with the control group, and in

the HCLa group compared with the LCLa group (P<0.05). These

results are presented in Table I and

Fig. 3.

| Table I.Histological scoring for rats with

acute pancreatitis. |

Table I.

Histological scoring for rats with

acute pancreatitis.

| Group | Edema | Inflammation | Vacuolization | Necrosis | Score |

|---|

| Control | 0.65±0.22 | 0.44±0.19 | 0.35±0.06 | 0.31±0.09 | 1.75±0.16 |

| LCLa | 3.52±2.13 | 2.34±1.65 | 0.45±0.07 | 0.44±0.13 |

6.75±2.12a |

| HCLa | 3.08±1.77 | 3.24±1.65 | 1.85±0.92 | 2.21±0.88 |

10.38±0.56a |

Serum levels of amylase

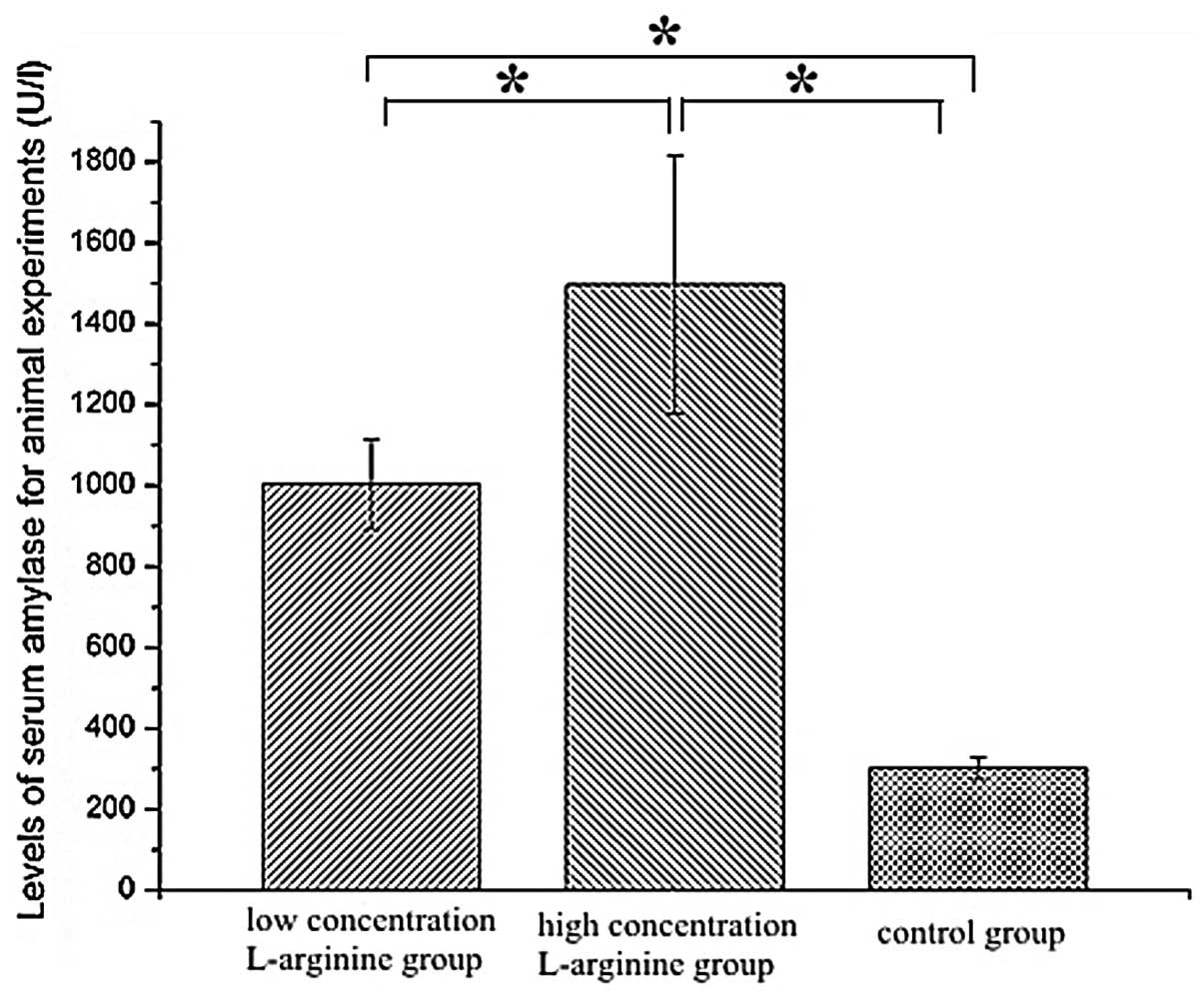

The levels of serum amylase were higher in the HCLa

(1,497.29±319.57 U/l) and LCLa (1,003.83±111.52 U/l) groups

compared with the control group (301.75±26.89 U/l). Statistically

significant increases in serum amylase were detected in the HCLa

and LCLa groups compared with the control group, and in the HCLa

group compared with the LCLa group (P<0.05). The results are

presented in Fig. 4.

SAP and mild AP (MAP) groups

All the HCLa and LCLa group rats exhibited

inflammation and edema of the pancreas. However, hemorrhage and

bloody ascites were only observed in the HCLa group rats. The most

elevated pancreatitis pathology scores and serum amylase levels

were observed in the HCLa group rats. In addition, the pathology

scores and levels of serum amylase in the HCLa and LCLa group rats

were higher compared with the control group rats. Therefore, the

HCLa rats were assigned as the SAP group, and the LCLa rats were

assigned as the MAP group.

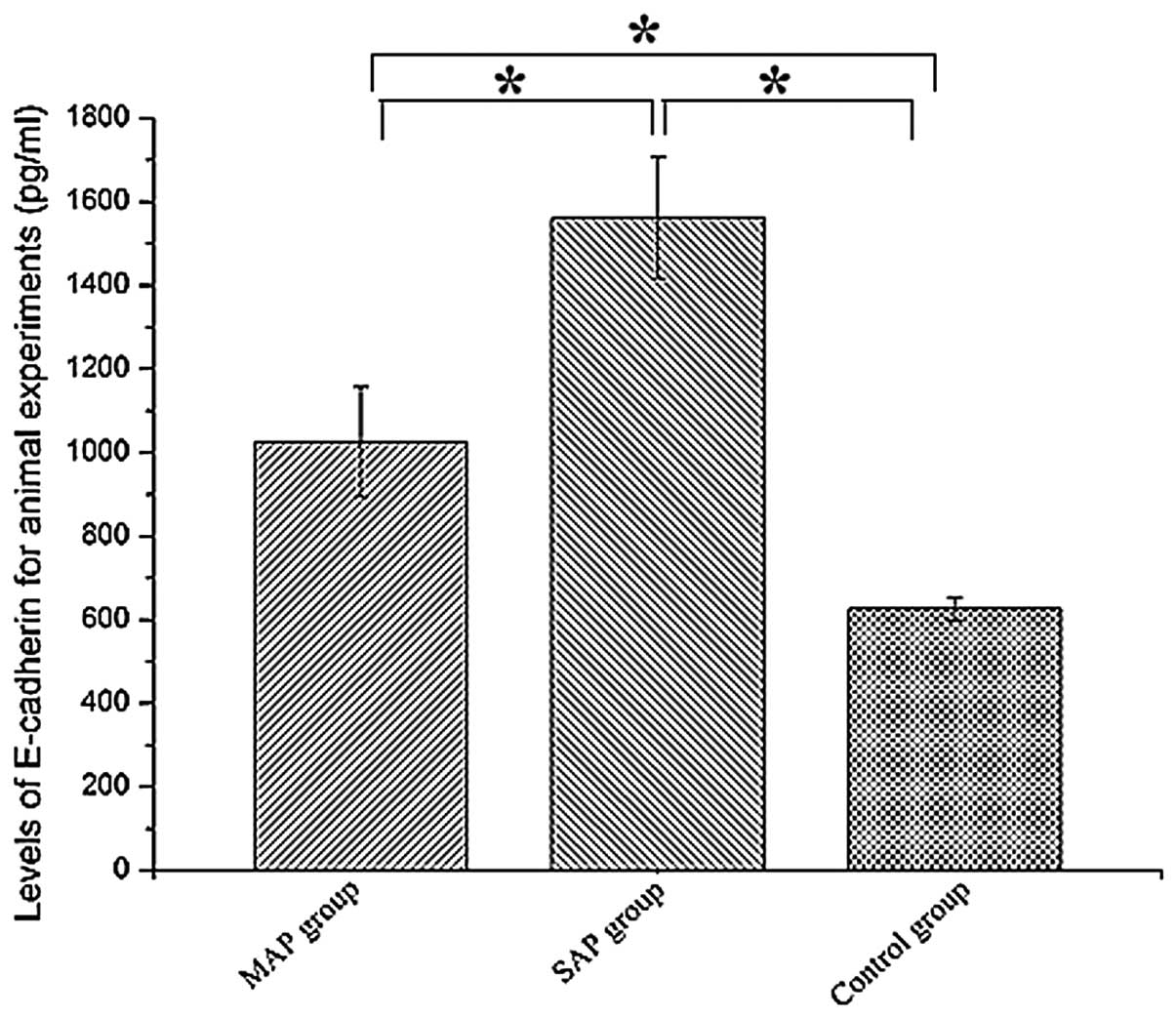

Serum levels of E-cadherin

The levels of E-cadherin were highest in the SAP

group rats. In addition, the levels of E-cadherin were higher in

the SAP (1,561.75±144.82 pg/ml) and MAP (1,025.50±131.33 pg/ml)

groups compared with the control group (626.50±72.12 pg/ml;

P<0.05). Statistically significant elevations in serum

E-cadherin were detected in the MAP and SAP groups compared with

the control group (P<0.05), and in the SAP group compared with

the MAP group (P<0.05). The results are presented in Fig. 5.

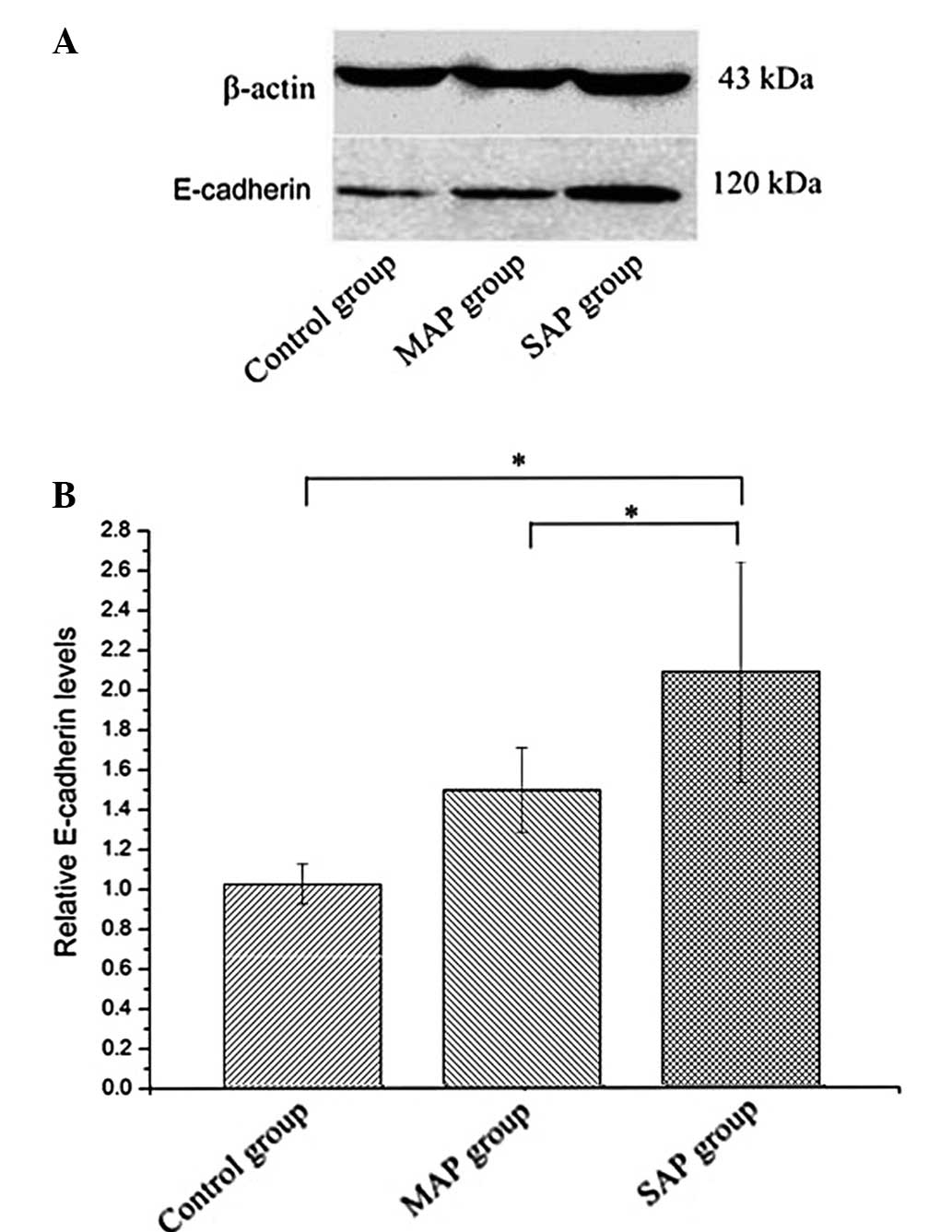

Expression of E-cadherin protein

The expression of E-cadherin protein was evaluated

using western blot analysis. The levels of E-cadherin protein were

higher in the SAP group compared with the MAP and control groups

(Fig. 6). Statistically significant

differences in E-cadherin protein expression were detected between

the SAP and MAP group rats, and between the SAP and control group

rats. No statistically significant differences in E-cadherin

protein expression were detected between the MAP and control group

rats.

Discussion

To date, a number of inflammatory molecules, have

been identified as potential predictive markers of SAP, including

interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6 and IL-10 (14,15).

However, the majority of studies on E-cadherin have focused on the

development and recurrence of cancer (16), and thus, few studies have

investigated the role played by E-cadherin in inflammation. To the

best of our knowledge, the role of E-cadherin in pancreatitis

remains controversial. In 2009, Sewpaul et al observed that

the mean concentration of soluble E-cadherin in patients with SAP

at <12 h was significantly higher compared with that in healthy

volunteers and patients with other gastrointestinal pathologies

(17). However, Pezzilli et

al reported that the serum levels of E-cadherin were not

associated with the severity of AP (18).

In the present study, a rat model of pancreatitis

was successful established using L-arginine. The SAP and MAP groups

were designated according to the results of histological

evaluations and the serum levels of amylase. The levels of serum

E-cadherin and E-cadherin protein were highest in rats in the SAP

group, which were evidently increased compared with the levels

detected in rats in the MAP and control groups. These results

suggest that the expression of E-cadherin is associated with the

severity of AP.

The mechanism underlying E-cadherin overexpression

in rats with SAP remains unclear. It is possible that

E-cadherin-associated apoptosis may serve a crucial function in the

pathogenesis of SAP. Takeyama reported that apoptosis was involved

in the mechanism of infectious complications, in addition to organ

dysfunction, in SAP (19). It is

known that apoptosis is regulated by numerous genes, and E-cadherin

is one among a variety factors that may influence the apoptotic

process (20). During apoptosis,

E-cadherin is efficiently cleaved in epithelial cells, and

fragments with apparent molecular masses of 24, 29 and 84 kDa are

generated following the induction of apoptosis by staurosporine or

camptothecin (21).

Another possible cause of the overexpression of

E-cadherin is that it may contribute to the extravasation of

erythrocytes and leukocytes in the early stages of SAP (8,21). In

the present rat experiments, hemorrhage of the pancreas and bloody

ascites were observed in the SAP group rats. The process of

extravasation into the parenchyma involves a number of molecular

interactions between blood cells and endothelial cells, including

tight adhesions, rolling and diapedesis (22). Vonlaufen et al reported that,

in cerulein-induced AP, the junctional adhesion molecule C is

upregulated (23). In addition,

Mayerle et al demonstrated that a variant that was 15 kDa

smaller than E-cadherin, which was detected in the early stage of

pancreatitis, was the product of E-cadherin cleavage at amino acid

394 in the extracellular domain; this phenomenon was consistent

with E-cadherin cleavage by leukocyte-produced elastase (8). Therefore, previous results suggested

that polymorphonuclear leukocyte-released elastase may be involved

in the dissociation of cell-cell contacts, the extracellular

cleavage of E-cadherin and, ultimately, the transmigration of

leukocytes into the epithelial tissue during the initial phase of

experimental pancreatitis (8).

In conclusion, the role of E-cadherin in

pancreatitis remains unclear. However, the present results indicate

that the expression levels of E-cadherin in SAP rats were higher

compared with those in MAP rats. Therefore, E-cadherin may be

associated with the severity of AP.

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by grants from the

National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 30901422 and

51271117).

References

|

1

|

Talukdar R and Vege SS: Recent

developments in acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol.

7(Suppl 11): 3–9. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

2

|

Zeng YB, Zhan XB, Guo XR, et al: Risk

factors for pancreatic infection in patients with severe acute

pancreatitis: An analysis of 163 cases. J Dig Dis. 15:377–385.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Granger J and Remick D: Acute

pancreatitis: models, markers and mediators. Shock. 24(Suppl 1):

45–51. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Pezzilli R, Billi P, Miglioli M and Gullo

L: Serum amylase and lipase concentrations and lipase/amylase ratio

in assessment of etiology and severity of acute pancreatitis. Dig

Dis Sci. 38:1265–1269. 1993. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Pooran N, Indaram A, Singh P and Bank S:

Cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF): early and reliable predictors of

severe acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 37:263–266. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Saito T, Yoshida K, Matsumoto K, et al:

Inflammatory cytokines induce a reduction in E-cadherin expression

and morphological changes in MDCK cells. Res Vet Sci. 96:288–291.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Ahmed RA, Shawky Ael-A and Hamed RH:

Prognostic significance of cyclin D1 and E-cadherin expression in

laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Pathol Oncol Res. 20:625–633.

2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Mayerle J, Schnekenburger J, Krüger B, et

al: Extracellular cleavage of E-cadherin by leukocyte elastase

during acute experimental pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterology.

129:1251–1267. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Glasbrenner B and Adler G: Pathophysiology

of acute pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 40:517–521.

1993.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Dawra R and Saluja AK: L-arginine-induced

experimental acute pancreatitis. The Pancreapedia: Exocrine

Pancreas Knowledge Base. 2012.

|

|

11

|

Czakó L, Takács T, Varga IS, et al: The

pathogenesis of L-arginine induced acute necrotizing pancreatitis:

inflammatory mediators and endogenous cholecystokinin. J Physiol

Paris. 94:43–50. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rongione AJ, Kusske A, Kwan K, Ashley SW,

Reber HA and McFadden DW: Interleukin 10 reduces the severity of

acute pancreatitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 112:960–967. 1997.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Yan S, Ding Y, Sun F, Lu Z, Xue L, Liu X,

Shuai M, Fang C, Wang Y, Cheng H, et al: Pretreatment of cisplatin

in recipients attenuates post-transplantation pancreatitis in

murine model. Int J Biol Sci. 8:298–309. 2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Matull W, Pereira S and O'Donohue J:

Biochemical markers of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol.

59:340–344. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Mayer J, Rau B, Gansauge F and Beger HG:

Inflammatory mediators in human acute pancreatitis: clinical and

pathophysiological implications. Gut. 47:546–552. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Wijnhoven B, Dinjens W and Pignatelli M:

E-cadherin-catenin cell-cell adhesion complex and human cancer. Br

J Surg. 87:99–1005. 2000. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

17

|

Sewpaul A, French J, Khoo T, Kernohan M,

Kirby J and Charnley R: Soluble E-cadherin: an early marker of

severity in acute pancreatitis. HPB Surgery. 2009:62009. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

18

|

Pezzilli R, Corsi MM, Barassi A, et al:

Serum E-cadherin and hepatocyte growth factor in acute

pancreatitis: Exploring time course and severity assessment.

Immunogastroenterology. 2:57–61. 2013. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

19

|

Takeyama Y: Significance of apoptotic cell

death in systemic complications with severe acute pancreatitis. J

Gastroenterol. 40:1–10. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Steinhusen U, Weiske J, Badock V, Tauber

R, Bommert K and Huber O: Cleavage and shedding of E-cadherin after

induction of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 276:4972–4980. 2001.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Vestweber D: Regulation of endothelial

cell contacts during leukocyte extravasation. Curr Opin Cell Biol.

14:587–593. 2002. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Imhof BA and Dunon D: Leukocyte migration

and adhesion. Advances in immunology. 58:3451995. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Vonlaufen A, Aurrand-Lions M, Pastor CM,

et al: The role of junctional adhesion molecule C (JAM-C) in acute

pancreatitis. J Pathol. 209:540–548. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|