Introduction

Painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis

(PBS/IC) occurs far more frequently in women than in men. It has

been reported that among 1.3 million Americans having the symptoms

of PBS/IC, >1.2 million were women in the year 2007 (1). The typical age predilection is ~40

years (2). The common symptoms of

PBS/IC include urinary urgency, frequency, nocturia and suprapubic

or pelvic pain without any known etiological factor. Diagnostic

criteria have been established by the National Institute of

Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) in order to

standardize the diagnosis of PBS/IC; these include objective

findings of glomerulations or Hunner's ulcer at cystoscopy and

subjective symptoms of bladder pain or urinary urgency, in addition

to multiple exclusion criteria such as age <18 years, duration

of symptoms <9 months and absence of nocturia (3). Even though numerous treatments have

been reported, including intravesical botulinum toxin A injections,

pentosan polysulfate sodium (PPS), dietary modification, lifestyle

interventions/behavioral therapies and bladder training, no

specific effective therapy has yet been identified.

As an immunosuppressive agent, cyclosporine A (CyA)

suppresses the activation of T cells by inhibiting the enzymatic

activity of calcineurin (4). It has

been successfully used in various conditions, such as in transplant

recipients, hepatitis C (5), and

autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis (6), Crohn's disease (7) and rheumatoid arthritis (8). Furthermore, CyA is emerging as a

potential therapeutic strategy for PBS/IC, which is an intractable

condition to treat. Several studies have reported promising results

for the treatment effects of CyA in PBS/IC. However, the strength

of the evidence of efficacy in each independent study is limited by

various factors, such as limitation of included subjects, or

absence of a control group. Therefore, the present systematic

review was performed in order to assess the global evidence

concerning the treatment effects of CyA in PBS/IC.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

The search strategy included the following key words

variably combined: ‘cyclosporine A,’ ‘bladder pain syndrome’ and

‘interstitial cystitis’. Databases including China National

Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), PubMed, Highwire, EMBASE and

Science Direct were searched for relevant references. In addition,

other retrieval strategies were performed to screen for relevant

articles, including manual retrieval and scanning of the reference

sections of eligible articles.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were regarded as qualified for inclusion if

they met all the following inclusion criteria: i) the disease type

was PBS/IC with or without meeting the NIDDK criteria; ii) the

study was a clinical trial, including randomized controlled trials

(RCTs), and prospective or retrospective cohort studies; iii) the

treatment effects of CyA in PBS/IC were measured. Studies were

excluded on the basis of any of the following criteria: i) the

article was a review, letter or case report; ii) the article did

not relate to the treatment effects of CyA in PBS/IC.

Data selection

Two researchers independently screened the initially

included articles on the basis of the inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Any disagreement was resolved by consensus. Baseline data and

result information were extracted and assessed by the same

researchers, including first author and publication year, country,

inclusion/exclusion criteria of each study, subjects, gender

(female/male), mean age, regimen protocol, outcome parameters,

follow-up and complications. In addition, all included articles

were assessed for methodological quality, according to the

Newcastle-Ottawa scale (9) for

nonrandomized studies and Jadad score for RCTs (10).

Results

Eligible articles

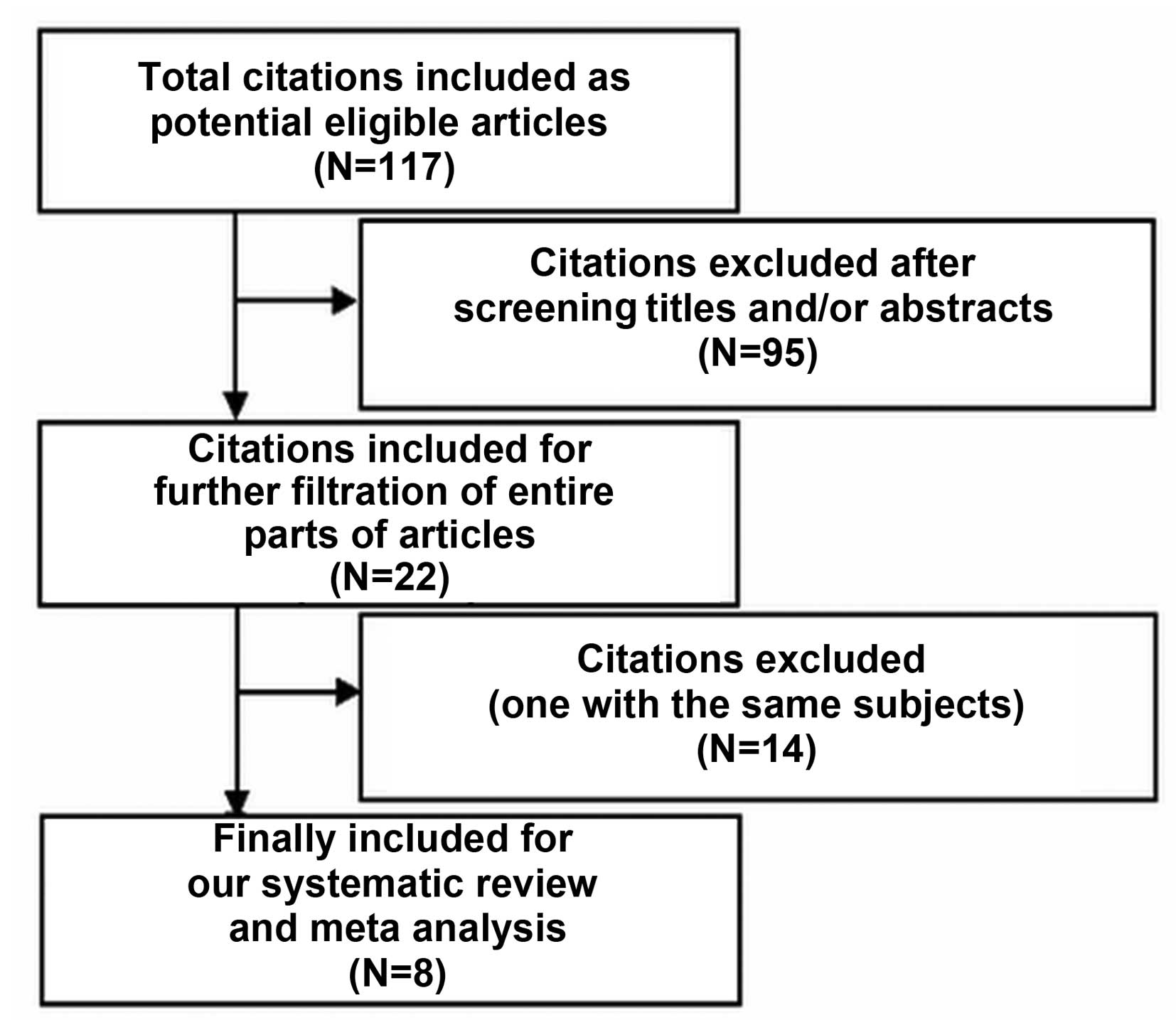

The various steps of the filtration procedure used

in this review are presented in Fig.

1. Initially, 117 articles were included (26 from PubMed, 11

from CNKI, 36 from Highwire, 17 from EMBASE and 31 from

ScienceDirect). No further relevant references were identified by

manual search and filtration of the reference sections of included

articles. Following careful screening of the titles and abstracts

of each article, 95 articles were excluded, leaving 22 articles for

further filtration. After screening the entire contents of these

articles, 14 articles were further excluded. Eight articles

(11–18) were finally included as eligible

articles, which including a total of 298 subjects with a median

number of 37.25 subjects per study. These 8 studies included 3 RCTs

(16–18), 4 prospective cohort studies (11–13,15) and

1 retrospective cohort study (14).

In the 7 studies that reported the ages of the subjects, the age

predilection was 40–70 years. In one of the articles (12), the patient age could not be

identified because only the abstract was available. The included

subjects were mostly females; the percentage of males was

relatively low. The sample sizes of the included studies were

uniformly small, ranging from 10 to 64. Other characteristics of

the included articles are listed in Table I.

| Table I.Baseline characteristics of the

included studies. |

Table I.

Baseline characteristics of the

included studies.

| First author,

publication year (Refs.) | Country | Study type | Inclusion/exclusion

criteria | No. of subjects | Gender

(female/male) | Mean age (years) | Regimen protocol | Outcome

parameters | Follow up | Complications |

|---|

| Ehrén, 2013 (11) | Sweden | Cohort,

prospective | Diagnosed with IC for

>2 years (some for up to 10 years). Exclusion: Use of

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II

antagonists, potassium-containing drugs, any medicine that inhibits

or induces CYP3A4, pregnancy, lactation, or regular intake of

hypericin or grapefruit | 10 | 6/4 | 58±13 | CyA dosage: 3

mg/kg/day for 12 weeks; followed by 4 weeks of deescalation in two

steps (1.5 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks and 0.75 mg/kg/day for 2 weeks,

respectively) and no medication for the last 2 weeks | NO formation; ICSI

and ICPI scores | 18 weeks | Mild adverse events;

no serum creatinine elevation or increase in blood pressure |

| Chade, 2014 (12) | Brazil | Cohort,

prospective | Fulfilled the NIDDKD

criteria | 45 | 43/2 | N/A | CyA dosage: 1.5 mg/kg

twice a day, for 5 years | ICSI and ICPI scores;

mean voided vol. (ml) | 5 years | None |

| Forrest, 2012

(13) | USA | Cohort,

prospective | Patients with no

contraindications to CyA and in whom the usual IC/PBS treatments

had failed | 44 | 30/14 | 55.5 | CyA dosage: 2–3 mg/kg

divided into 2 daily dosages with a maximum of 300 mg daily; if

adverse events occurred the dose was reduced or the drug was

stopped | Symptom response

(based on ICSI or GRA); response with vs. without HL; CyA

levels | mean, 20.8 months

(range, 3–81) | Serum creatinine was

increased in 9 patients, causing 4 patients to stop CyA treatment;

Hypertension in 3 patients |

| Sairanen, 2004

(14) | Finland | Cohort,

retrospective | Fulfilled the NIDDKD

criteria, and multiple first-line therapies had been tried without

clinical success | 23 | 20/3 | 65.7±7.6 | CyA dosage: 3 mg/kg

divided into 2 daily dosages. When symptoms were alleviated the

dose was gradually decreased to as low as 1 mg/kg as a single daily

dose | Mean voided vol.

(ml); maximum awake bladder capacity (ml); 24-h voiding

frequency | 60.8±35.7 months | Hypertension and

gingival hyperplasia occurred in 3 patients, respectively; induced

hair growth occurred in 2 patients |

| Forsell, 1996

(15) | Finland | Cohort,

prospective | Fulfilled the

criteria for IC according to an international accrual form | 11 | 10/1 | 27–75 | CyA dosage: 3–6

months at an initial dose of 2.5–5 mg/kg daily and a maintenance

dose of 1.5–3 mg/kg daily | No. of voids/24 h;

daily urinary output; mean voided vol.; maximum voided vol. | N/A | Noted in 6 patients,

including mild hypertension (n=2), mild hyperplasia (n=2),

transient tremor (n=1) and growth of facial hair (n=1) |

| Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Finland | RCT | Fulfilled the NIDDK

criteria for IC. Exclusion criteria: History of cancer in the last

10 years, untreated hypertension or renal insufficiency [serum

creatinine higher than normal limits (>90 mg/dl in females or

>100 mg/dl in males)] | 64 | 53/11, | Case, 56.2±14.7;

control, 59.7±13.0 | Case group: 1.5 mg/kg

CyA twice daily (27 women, 5 men); control group: 100 mg PPS 3

times daily (26 women, 6 men) | Frequency in 24 h;

max awake bladder capacity; mean voided vol.; VAS; nocturia

episodes; ICSI and ICPI symptom scores, GRA; PST | 6 months | Mild adverse

events |

| Sairanen, 2008

(17) | Finland | RCT | Fulfilled the NIDDKD

criteria | 37 | 32/5, | Case, 55.7±14.8;

control, 56.4±13.2 | Case group: 1.5 mg/kg

CyA twice daily; control group: 100 mg PPS 3 times daily | GRA; EGF, IL-6; pain

score (VAS); urinary frequency 24 h; mean voided volume; ICSI

score | 6 months | N/A |

| Sairanen, 2009

(18) | Finland | RCT | Fulfilled the NIDDKD

criteria | 64 | 51/13 | Case, 53.2±11.9;

control, 57.3±10.0 | Case group: 1.5 mg/kg

CyA twice daily; control group: 100 mg PPS 4 times daily | General health

perceptions; pain; emotional wellbeing; vitality; social

functioning; physical capacity; sexual interest; sexual

functioning | 6 months | N/A |

Six studies used the NIDDK criteria for diagnosing

IC (12,14,16–18); the

other two studies used clinical symptoms to diagnose PBS/IC

(11,13). The subjects of two studies (13,14) were

patients in whom multiple first line therapies had failed. Regimen

protocols were presented in all studies; the initial dosage of CyA

was typically 2–3 mg/kg/day, sometimes divided into 2 daily

dosages. If the symptoms were alleviated, the dosage of CyA was

gradually decreased to a tolerance dose; if adverse events occurred

the dose was reduced or the drug was stopped. In the three RCTs

(16–18), the treatment therapy administered to

the control group was 100 mg PPS 4 times daily.

Methodological quality

All studies have detailed descriptions of the

ascertainment of diagnosis, assessment of outcome and the

instruments used to assess outcomes. All of the articles, with the

exception of one (15), reported the

follow-up time; the longest duration of follow-up was 5 years

(12) and, the proportion of

patients lost to follow-up was <20% in all studies. On the basis

of the Jadad scale, the scores for the included RCTs ranged from 1

to 3 (regard as low methodological quality).

Outcome assessment

The outcome assessment of the included studies is

presented in Table II. The

O'Leary-Sant Symptom and Problem Indices of Interstitial Cystitis

(ICSI and ICPI, respectively) were used as outcome measures in 5

studies (11–13,16,17).

Other outcome parameters were reported, including mean voided

volume (ml) (12,14–17),

maximum awake bladder capacity (ml) (14–16),

urinary frequency (24 h) (14–17),

pain score (visual analog scale, VAS) (16,17),

cytokine levels (11,17), daily urinary output (ml) (15), nocturia episodes (16) and improvement of quality of life

(QoL) (18). All outcome parameters,

with the exception of the biomarker IL-6, were reported to exhibit

improvement following treatment of CyA, even though the degree of

improvement varied. However, Sairanen et al (17) reported that IL-6 was significantly

(P=0.04) decreased in patients ≥53 years old following treatment

with CyA, but not following treatment with PPS (P=0.73). All

reported parameters in the three RCTs implied that the treatment

effects of CyA were far superior to those of PPS treatment. In

addition, long-term treatment with a low dosage of CyA could

provide a persistent improvement of symptoms. The symptoms were

recurrence if the treatment of CyA was discontinued.

| Table II.Outcome assessment of included

studies. |

Table II.

Outcome assessment of included

studies.

| Outcome | First author, year

(Refs.) | Results |

|---|

| ICSI and ICPI | Ehren, 2013 (11) | ICSI: reduced

from16±1 to 8±1; ICPI: reduced from 14±1 to 6±1, after 12 weeks;

ICSI and ICPI remained at a low level when treatment was continued;

without treatment ICSI and ICPI increased again, to 12±2 and 9±2,

respectively |

|

| Chade, 2014 (12) | ICSI: reduced from 36

initially to 21.6 at 6 months, and 8.4 at 5 years (P<0.001);

ratio of patients with ICPI scores >8 reduced from 100 to

22% |

|

| Forrest, 2012

(13) | 26/44 (59%) patients

with symptom response, 10/44 (23%) patients without symptom

response; patients with HL had a higher response (23/34, 68%) than

patients without HL; low dosage of treatment for symptom

maintance |

|

| Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Sum of ICSI + ICPI:

−15.0±9.4 in CyA group vs. −3.1±4.3 in PPS group (P<0.001);

ICSI: −7.9±4.5 in CyA group vs. −2.0±2.6 in PPS group (P<0.001);

ICPI: −7.1±4.4 in CyA group vs. −1.5±1.8 in PPS group

(P<0.001) |

|

| Sairanen, 2008

(17) | Sum of ICSI + ICPI:

Reduced from 28.8 to 15.1 in CyA group vs. 30.5 to 28.5 in PPS

group; responder (GRA, 5 or 6): 13/18 (72%) in CyA group vs. 3/19

(16%) in PPS group |

| Mean voided volume

(ml) | Chade, 2014 (12) | Upregulated from 103

pretreatment to 170 after CyA treatment |

|

| Sairanen, 2004

(14) | Upregulated from

101.47 (SD, 42.7) pretreatment to 246.4 (SD, 97.9) after CyA

treatment (P<0.001) |

|

| Forsell, 1996

(15) | Upregulated from

100.4 (SD, 58.4) pretreatment to 173.7 (SD, 84.0) after CyA

treatment |

|

| Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Improvement: 59±57 in

CyA group vs. 1±31 in PPS group (P<0.001) |

|

| Sairanen, 2008

(17) | Improvement: From

28.8 (SD, 4.8) to 15.1 (SD, 8.6) in CyA group vs. 30.5 (SD, 3.8) to

28.5 (SD, 5.6) in PPS group (P=0.003) |

| Maximum awake | Sairanen, 2004

(14) | Upregulated from

168.8 (SD, 74.6) pretreatment to 360.7 (SD, 99.3) after CyA

treatment (P<0.001) |

| bladder capacity

(ml) | Forsell, 1996

(15) | Upregulated from

179.1 (SD, 96.3) pretreatment to 361.4 (SD, 137.6) after CyA

treatment |

|

| Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Improvement: 81±94 in

CyA group vs. 2.8±60 in PPS group (P=0.003) |

| Urinary frequency (24

h) | Sairanen, 2004

(14) | Reduced from 20.8

(SD, 6.3) pretreatment to 10.2 (SD, 3.8) after CyA treatment

(P<0.001) |

|

| Forsell, 1996

(15) | Reduced from 20.55

(SD, 6.2) pretreatment to 11.9 (SD, 4.0) after CyA treatment |

|

| Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Improvement:

−6.7±4.7 in CyA group vs. −2.0±5.1 in PPS group (P<0.001) |

|

| Sairanen, 2008

(17) | Reduced from 16.4

(SD, 3.5) to 11.0 (SD, 4.2) in CyA group vs. 19.5 (SD, 5.9) to 18.4

(SD, 6.3) in PPS group (P=0.005) |

| Pain score

(VAS) | Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Improvement:

−4.7±3.5 in CyA group vs. −1.6±3.3 in PPS group (P<0.001). |

|

| Sairanen, 2008

(17) | Reduced from 7.0

(SD, 2.2) to 2.2 (SD, 2.5) in CyA group vs. 7.5 (SD, 2.1) to 5.8

(SD, 3.1) in PPS group (P=0.005). |

| Cytokine

levels | Ehren, 2013

(11) | NO (ppm): Reduced

after treatment with CyA, from 489±141 initially to 16±6 (2 weeks),

10±7 (4 weeks), 7±3 (6 weeks) and 3±1 (8 weeks); increased to

144±70 when the dosage of CyA was reduced to 0.75 mg/kg/day;

without treatment in last 2 weeks, the level rose to 478±187. |

|

| Sairanen, 2008

(17) | EGF (mean, ng/mg

creatinine): reduced from 35 to 28 in CyA group (P=0.034) vs. 33 to

32 in PPS group (P=0.81); ≥ 53 years old, reduced from 34 to 23 in

CyA group (P=0.001) vs. 31 to 30 in PPS group (P=1.00); IL-6 (mean,

pg/ml): reduced from 7.1 to 3.6 in CyA group (P=0.18) vs. 11 to 11

in 0.PPS group (P=38); ≥53 years old, reduced from 10.3 to 4.1 in

CyA group (P=0.04) vs. 13.7 to 10.3 in PPS group (P=0.73) |

| Daily urinary

output (ml) | Forsell, 1996

(15) | Upregulated from

1,832.7 (SD, 754) pretreatment to 1,954 (SD, 691.6) after CyA

treatment |

| Nocturia

episodes | Sairanen, 2005

(16) | Improvement:

−2.2±1.6 in CyA group vs. −0.2±2.1 in PPS group (P<0.001) |

| Improvement of

QoL | Sairanen, 2009

(18) | Improvement greater

in the CyA group than in the PPS group, including general health

perceptions, pain, emotional wellbeing, social functioning,

physical capacity, limitation days, % of patients undertaking

sexual activity (masturbation or intercourse) |

Adverse effects

Five of the 8 included studies reported

complications, which mainly comprised tiredness, abdominal pain,

nausea, diarrhea and gingival hyperplasia (1 patient), induced hair

growth (3 patients), serum creatinine elevation (12 patients) and a

rise in blood pressure (8 patients). Following symptomatic

treatment, the majority of patients were able to undergo sustained

CyA treatment. However, 4 patients were required to stop treatment

with CyA following increases in serum creatinine levels.

Discussion

The evidence from the included studies demonstrates

that oral treatment with CyA may be an appropriate therapeutic

strategy for patients with PBS/IC, and there is a trend towards

benefit with a long-term low-dosage regimen. To the best of our

knowledge, he present review summarizes all the prospective or

retrospective non-randomized cohort trials and RCTs that exist on

this topic.

CyA may be more advantageous in severe PBS/IC,

because two studies (11,13) included patients in whom the usual

IC/BPS treatments had failed, and the symptoms and parameters in

those patients improved following treatment with CyA (2–3 mg/kg

divided into 2 daily dosages with a maximum of 300 mg daily). In

addition CyA exhibited a higher curative effect than PPS. Long-term

low-dosage CyA treatment can provide and maintain good symptom

relief (19). However, symptoms may

recur if the therapy with CyA is stopped. Hence, it is suggested

that the use of CyA may be primarily as a drug for symptom

improvement rather than a fundamental solution or cure. In

addition, a series of adverse effects (in particular, upregulation

of serum creatinine levels and hypertension) are of concern when

oral CyA therapy is carried out.

There are several advantages of this systematic

review. Firstly, a critical issue has been addressed. The search

strategy was full-scale and without language restrictions.

Secondly, two reviewers independently screened the eligible

articles and extracted data with minimum errors. Thirdly, attempts

were made to contact authors of published and unpublished studies

to obtain relevant details for this systematic review.

However, the included studies contained small

numbers of patients with short-term or long-term follow-up. For one

included study (12), only the

abstract was available for analysis in this systematic review, and

it was not possible to obtain further details. The heterogeneity of

the diagnosis criteria of PBS/IC, differences in methods, varied

number of outcome measures employed and small number of

participants, create challenges in the analysis of the treatment

effect of CyA in PBS/IC. Therefore, further higher quality clinical

trials are required to further explore the effectiveness of oral

CyA in the treatment of PBS/IC.

References

|

1.

|

Clemens JQ, Link CL, Eggers PW, Kusek JW,

Nyberg LM and McKinlay JB: BACH Survey Investigators: Prevalence of

painful bladder symptoms and effect on quality of life in black,

Hispanic and white men and women. J Urol. 177:1390–1394. 2007.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2.

|

Held PJ, Hanno PM, Wein AJ, Pauly MV and

Cahn MA: Epidemiology of interstitial cystitis. Interstitial

Cystitis. Hanno PM, Staskin DR, Krane RJ and Wein AJ: (London).

Springer. 29–48. 1990. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

3.

|

Gillenwater JY and Wein AJ: Summary of the

National Institute of Arthritis, Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney

Diseases workshop on interstitial cystitis, National Institutes of

Health, Bethesda, Maryland, August 28–29, 1987. J Urol.

140:203–206. 1988.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4.

|

Ogawa H, Kameda H, Amano K and Takeuchi T:

Efficacy and safety of cyclosporine A in patients with refractory

systemic lupus erythematosus in a daily clinical practice. Lupus.

19:162–169. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5.

|

Forns X and Navasa M: Cyclosporine A or

tacrolimus for hepatitis C recurrence? An old debate. Am J

Transplant. 11:1559–1560. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6.

|

Maza A, Montaudiè H, Sbidian E, Gallini A,

Aractingi S, Aubin F, Bachelez H, Cribier B, Joly P, Jullien D, et

al: Oral cyclosporin in psoriasis: A systematic review on treatment

modalities, risk of kidney toxicity and evidence for use in

non-plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 25(Suppl 2):

S19–S27. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

7.

|

Sternthal MB, Murphy SJ, George J,

Kornbluth A, Lichtiger S and Present DH: Adverse events associated

with the use of cyclosporine in patients with inflammatory bowel

disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 103:937–943. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8.

|

Dijkmans B and Gerards A: Cyclosporin in

rheumatoid arthritis: Monitoring for adverse effects and clinically

significant drug interactions. BioDrugs. 10:437–445. 1998.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9.

|

Stang A: Critical evaluation of the

Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of

nonrandomized studies in meta-analysis. Eur J Epidemiol.

25:603–605. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10.

|

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson

C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ and McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of

reports of randomized clinical trials: Is blinding necessary?

Control Clin Trials. 17:1–12. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11.

|

Ehrén I, Grufman Hallén K, Vrba M,

Sundelin R and Lafolie P: Nitric oxide as a marker for evaluation

of treatment effect of cyclosporine A in patients with bladder pain

syndrome/interstitial cystitis type 3C. Scand J Urol. 47:503–508.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12.

|

Chade J, Chade D, Lucon AM, Bruschini H

and Srougi M: 462 5-year follow-up of patients with refractory

interstitial cystitis treated with cyclosporine A: A prospective

single-institution study. Eur Urol. (Supp 13): e4622014. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

13.

|

Forrest JB, Payne CK and Erickson DR:

Cyclosporine A for refractory interstitial cystitis/bladder pain

syndrome: Experience of 3 tertiary centers. J Urol. 188:1186–1191.

2012. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14.

|

Sairanen J, Forsell T and Ruutu M:

Long-term outcome of patients with interstitial cystitis treated

with low dose cyclosporine A. J Urol. 171:2138–2141. 2004.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15.

|

Forsell T, Ruutu M, Isoniemi H, Ahonen J

and Alfthan O: Cyclosporine in severe interstitial cystitis. J

Urol. 155:1591–1593. 1996. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16.

|

Sairanen J, Tammela TL, Leppilahti M,

Multanen M, Paananen I, Lehtoranta K and Ruutu M: Cyclosporine A

and pentosan polysulfate sodium for the treatment of interstitial

cystitis: A randomized comparative study. J Urol. 174:2235–2238.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17.

|

Sairanen J, Hotakainen K, Tammela TL,

Stenman UH and Ruutu M: Urinary epidermal growth factor and

interleukin-6 levels in patients with painful bladder

syndrome/interstitial cystitis treated with cyclosporine or

pentosan polysulfate sodium. Urology. 71:630–633. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18.

|

Sairanen J, Tammela TL, Leppilahti M,

Onali M, Forsell T and Ruutu M: Potassium sensitivity test (PST) as

a measurement of treatment efficacy of painful bladder

syndrome/interstitial cystitis: A prospective study with

cyclosporine A and pentosan polysulfate sodium. Neurourol Urodyn.

26:267–270. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19.

|

Gao X, Ma Y, Sun L, Chen D, Mei C and Xu

C: Cyclosporine A for the treatment of refractory nephritic

syndrome with renal dysfunction. Exp Ther Med. 7:447–450.

2014.PubMed/NCBI

|