Introduction

The human gustatory system allows the sense of the

following five basic tastes: Sour, bitter, sweet, salty and umami.

The biological mechanism of taste involves a series of electrical

signals triggered by molecular stimulations of the taste buds.

These impulses are conducted to the brain, which interprets these

signals as the appropriate taste (1,2).

Historically, tastes were evaluated with human

taster panels, which suffer from numerous limitations such as

tester fatigue, particularly in regards to bitterness. In the early

stages of drug development, this method is unsuitable because it

has a high cost and is potentially dangerous (3,4).

Therefore, analytical taste sensing tools such as the electronic

tongue (E-tongue) have been developed to increase safety and reduce

costs. E-tongue technology originated from multi-analyte sensing

technology between the 1980s and 1990s. The electronic nose was a

particularly powerful example of multi-analyte sensing and has been

employed in defense and environmental applications (5). Later, researchers extended this to

solution-phase analysis for a variety of chemical ‘tastes’.

Analytes include small molecules, proteins and whole blood cells

(6,7). At the core of the technology are

multiple sets of taste sensor arrays, whose surface is coated with

a ‘sensing membrane’ material similar to that in biological

systems. When a taste substance is adsorbed onto this membrane,

data is obtained from the resulting changes in membrane potential.

This technology offers an intelligent electronic recognition

system, which reflects the overall taste information of a sample

(1,8–10).

This taste-sensing technology has been applied to

the food industry (11,12) for >20 years in numerous roles,

including food traceability (13),

freshness (14), quality (15–17) and

safety inspection (18,19). Increasingly, this technique is being

applied in pharmaceutical fields (20–22),

where it is frequently used to evaluate the bitterness of medicines

and make improvements to their formulations (23–28).

Although the collection of taste information of

foods and drugs using the E-tongue, and the following post-hoc

processing and analysis, is now fairly common, there remains

multiple unresolved issues in regards to precision and

reproducibility of the results, and the identification of taste

between different systems. The present study utilized the E-tongue

to collect taste information on medicines that have not been

characterized. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first

study to optimize the methodology of taste analysis using the

E-tongue (22–24). The method established was empirically

optimized, validated and applied to collect taste information of a

number of TCM decoctions.

Materials and methods

Apparatus

The present study was performed using an ASTREE II

electronic tongue (Alpha M.O.S, Toulouse, France). The E-tongue

consisted of a hexadecimal autosampler, a silver/silver chloride

reference electrode, a data acquisition system, a workstation

running AlphaSoft software (version 12; Alpha M.O.S, Toulouse,

France) and seven sensors. The seven sensors were called

ZZ2808-2-512 (ZZ), CA2804-2-440 (CA), DA2808-12-330 (DA),

BA2808-2-230 (BA), GA2808-2-361 (GA), BB2011-09-141 (BB) and

AB2011-10-010 (AB), and were specifically developed for measuring

bitterness. The sensors contain two semiconductor regions composed

of a thermal insulation material, each covered with a different

molecular membrane, with different adsorption properties and the

detection thresholds.

Preparation of berberine

hydrochloride, rhynchophylline, leonurine, matrine and quinine

samples

Samples were weighed using an electronic balance

(±0.1 mg accuracy) at room temperature and dissolved completely in

deionized water. Solutions of berberine hydrochloride (lot no.

101002; Sichuan Province Yuxin Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Deyang,

China), rhynchophylline (lot no. 20100216; Hubei Tungshun Medicine

Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China), leonurine (lot

no. SX-091205; Xi'an Hao-Xuan Bio-Tech Co., Ltd., Xi'an, China),

matrine (lot no. KS20110725; Xi'an Jiatian Biotechnology Co., Ltd.)

and quinine (lot no. 20100510; Shanxi Tianyuan Pharmaceutical Co.

Ltd, Yùnchéng, China) were prepared at concentrations of 0, 0.025,

0.1, 0.25, 0.5 and 1 mmol and stored at 4°C until required.

Preparation of TCM samples

Ten-fold concentrations of 35 Chinese herbs were

prepared, relative to the mean of the prescribed dosage in the

Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of China. The herbs were

placed in 2,000 ml water, soaked for 30 min and heated in a

microwave (2100 W) until boiling. The power was then reduced to 600

W and the solution heated for a further 20 min. The remaining herb

pieces were filtered out, an additional 2,000 ml of water was

added, the solution heated until boiling and then boiled for 10

min. This process was repeated for each herb. Then, the filtrates

of the first and second decoctions were combined, mixed and cooled

to room temperature, followed by centrifugation at room temperature

for 15 min at 1,434 × g. The supernatant was collected and

the volume adjusted to 4,000 ml. Samples were aliquoted, capped,

sterilized and stored at 4°C until required.

Optimization of measurement time

Purified water was used as the washing solution and

0.5 mmol caffeine solution was used as the sample. The E-tongue was

cleaned with washing solution (6 times, 10 sec/wash). Then, 80 ml

of sample solution was placed in a 120 ml beaker for analysis. Each

E-tongue measurement used all 7 sensors, which was taken at room

temperature and lasted 120 sec. The same sample was measured 10

times consecutively, with the values of last 4 measurements being

used to calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD). In

addition, RSD was measured in in 10 sec ranges (e.g. 0–9, 1–10 and

2–11 sec).

Optimization of the number of sample

measurements

At the beginning of a measurement the signal is

unstable, stabilizing as the number of measurements increase. To

investigate how many replicates were required for the response

signal to become stable, matrine and berberine hydrochloride

samples (described previously) were measured using the E-tongue 10

times, with each measurement lasting for 120 sec. RSD values were

calculated for all measurements and then compared.

Optimization of the order of E-tongue

washing and sample measurement

Berberine hydrochloride (80 ml) was added to a 120

ml beaker for E-tongue measurements. The following two measurement

schemes were then performed: i) The E-tongue was washed once

in-between each measurement of the same sample; and ii) the same

sample was measured without washing in-between. In this experiment,

the same sample was measured seven times (120 sec each) and the

results of last 4 measurements used to calculate the RSD.

Validation of reproducibility

Aqueous solutions of 0.5 mmol rhynchophylline,

matrine, quinine and leonurine were prepared in triplicate (12

samples total). E-tongue measurements were conducted under the

optimized conditions described above. In this experiment, the same

solution was measured seven times (120 sec each) and the results of

last 4 measurements used to calculate the RSD. The RSD of each

sample prepared in triplicate was then compared to evaluate

reproducibility.

Validation of precision within a

measurement cycle (6 h)

The measurement time is <15 min for a single

sample, however, a complete experiment requires the measurement of

multiple samples. In order to ensure accuracy of the results, the

measurement of all samples need to be finished within a measurement

cycle (6 h). Aqueous solutions of quinine at 0.1, 0.5 and 1.0 mmol

were prepared and measured using the E-tongue. Measurements were

repeated four times. All measurements were completed within 6 h,

and the results of last 4 measurements used to calculate the

RSD.

Validation of inter-day precision

Aqueous solutions of quinine at 0.025, 0.1, 0.25,

0.5 and 1.0 mmol were measured in triplicate on days 1, 2 and 3 to

measure E-tongue data reproducibility on different days. In

addition, the RSD of E-tongue measurements over the three days was

calculated.

Analysis of the taste of TCMs with

different degrees of bitterness

In the present study 35 Chinese herbs (lot no.

20110224; Henan Zhongyi Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Zhengzhou, China)

were selected from the ‘Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of

China’ (29). This text describes

the TCMs used in the present study by the following

characteristics: Light smell, tasteless; light smell, slightly

bitter taste; light smell, bitter taste; and light smell, very

strong bitter taste. The tastes described were evaluated using a

human taster panel according to the degree of bitterness (30–32). TCM

samples, prepared as described above, were measured using the

E-tongue under the optimized conditions described above.

The results of E-tongue measurements and the human

taste panel were evaluated using the robust regression analysis

method (33,34). E-tongue measurements of 6 samples

were excluded, using standardized residuals and score distance as

indicators. These findings were in preparation for a publication

elsewhere (35). The remaining 29

samples were grouped into two classes or three classes (Table I), based upon their bitterness levels

(I–V) described by Liu et al (30). A two-dimensional bitterness

classification model was established by considering level I as a

class and grouping levels II, III, IV and V as the second class.

The three-dimensional classification models consider level I as a

class, levels II and II as a second class, and levels IV and V as a

third class.

| Table I.TCM samples measured, including the

name of the drug and bitterness. |

Table I.

TCM samples measured, including the

name of the drug and bitterness.

| Sample no. | Chinese pinyin | Drug/sample | Bitterness | Two-dimensional

classification | Three-dimensional

classification |

|---|

| 1 | Fuling | Poria | 0.63 | I |

I |

| 2 | Tongcao | Tetrapanacis

medulla | 0.64 | I |

I |

| 3 | Sangzhi | Mori ramulus | 0.67 | I |

I |

| 4 | Gouteng | Uncariae ramulus

cum uncis | 0.70 | I |

I |

| 5 | Chuanmutong | Clematidis armandii

caulis | 0.70 | I |

I |

| 6 | Cheqianzi | Plantaginis

semen | 0.71 | I |

I |

| 7 | Mingdangshen | Changii radix | 0.73 | I |

I |

| 8 | Tianhuafeng | Trichosanthis

radix | 0.91 | I |

I |

| 9 | Zexie | Alismatis

rhizoma | 0.95 | I |

I |

| 10 | Zelan | Lycopi herba | 1.19 | I |

I |

| 11 | Cang'erzi | Xanthii

fructus | 1.21 | I |

I |

| 12 | Zhuru | Bambusae caulis in

taenias | 1.24 | I |

I |

| 13 | Duzhong | Eucommiae

cortex | 1.26 | I |

I |

| 14 | Cheqiancao | Plantaginis

herba | 1.26 | I |

I |

| 15 | Baiwei | Cynanchi atrati

radix et rhizoma | 1.67 | II | II |

| 16 | Qiancao | Rubiae radix et

rhizoma | 1.81 | II | II |

| 17 | Zhebeimu | Fritillariae

thunbergii bulbus | 1.82 | II | II |

| 18 | Beidougen | Menispermi

rhizoma | 2.03 | II | II |

| 19 | Yanhusuo | Corydalis

rhizoma | 2.80 | II | II |

| 20 | Fangji | Stephaniae

tetrandrae radix | 3.01 | II | II |

| 21 | Huangqin | Scutellariae

radix | 3.28 | II | II |

| 22 | Dangyao | Swertiae herba | 3.92 | II | III |

| 23 | Chuanxinlian | Andrographis

herba | 4.04 | II | III |

| 24 | Kumu | Picrasmae ramulus

et folium | 4.08 | II | III |

| 25 | Huanglian | Coptidis

rhizoma | 4.45 | II | III |

| 26 | Longdan | Gentianae radix et

rhizoma | 4.55 | II | III |

| 27 | Huangbo | Phellodendri

chinensis cortex | 4.66 | II | III |

| 28 | Huhuanglian | Picrorhizae

rhizoma | 4.67 | II | III |

| 29 | Kushen | Sophorae

flavescentis radix | 4.78 | II | III |

Statistical analysis

Least squares support vector machine (LS-SVM),

simple support vector machine (SVM) or discriminant analysis (DA)

classification algorithms were used for the classification models.

MATLAB (release R2011b; Mathworks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA) and

LS-SVMlab Toolbox software [version 1.8; www.esat.kuleuven.be/sisita/lssvmlab (accessed

23/01/16)] was used.

Using the LS-SVM method, the accuracy of the

classification models compared with the results of the human taste

panel measured, this was then used to select the most appropriate

function for study, including linear kernels, polynomial kernels

and radial basis functions. For each type of kernel, a

self-compiled program screened and optimized the model parameters

repeatedly, finally selecting the most appropriate kernel function

and parameters. Modeling optimization was performed with SVM

(36) and DA (37), with classification accuracy rates of

cross-validation calculated separately.

PLS regression analysis was conducted on latent

variables. Then, the projection scoring factors in principal

component space were used to produce the two- and three-dimensional

classification results.

Results and Discussion

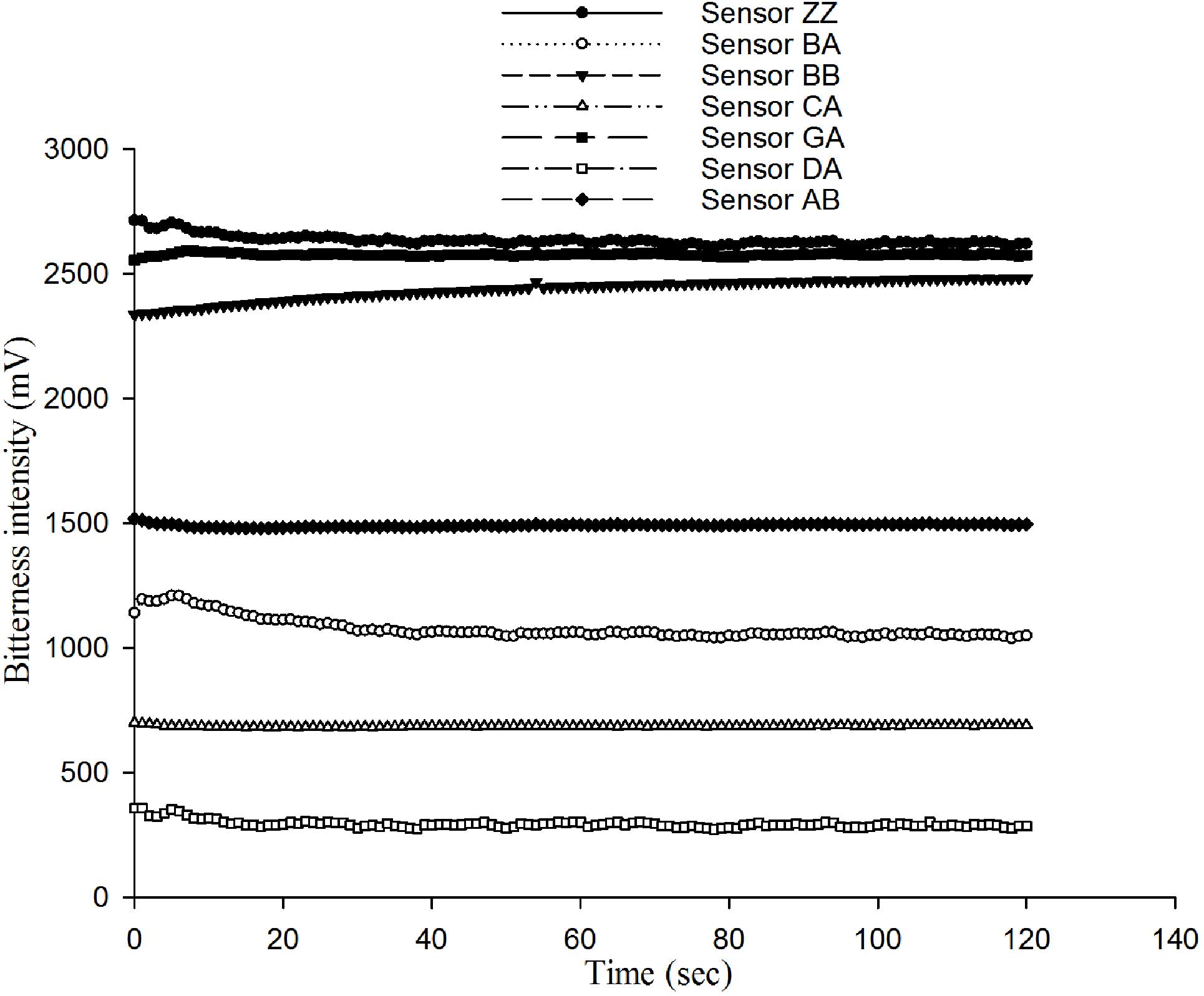

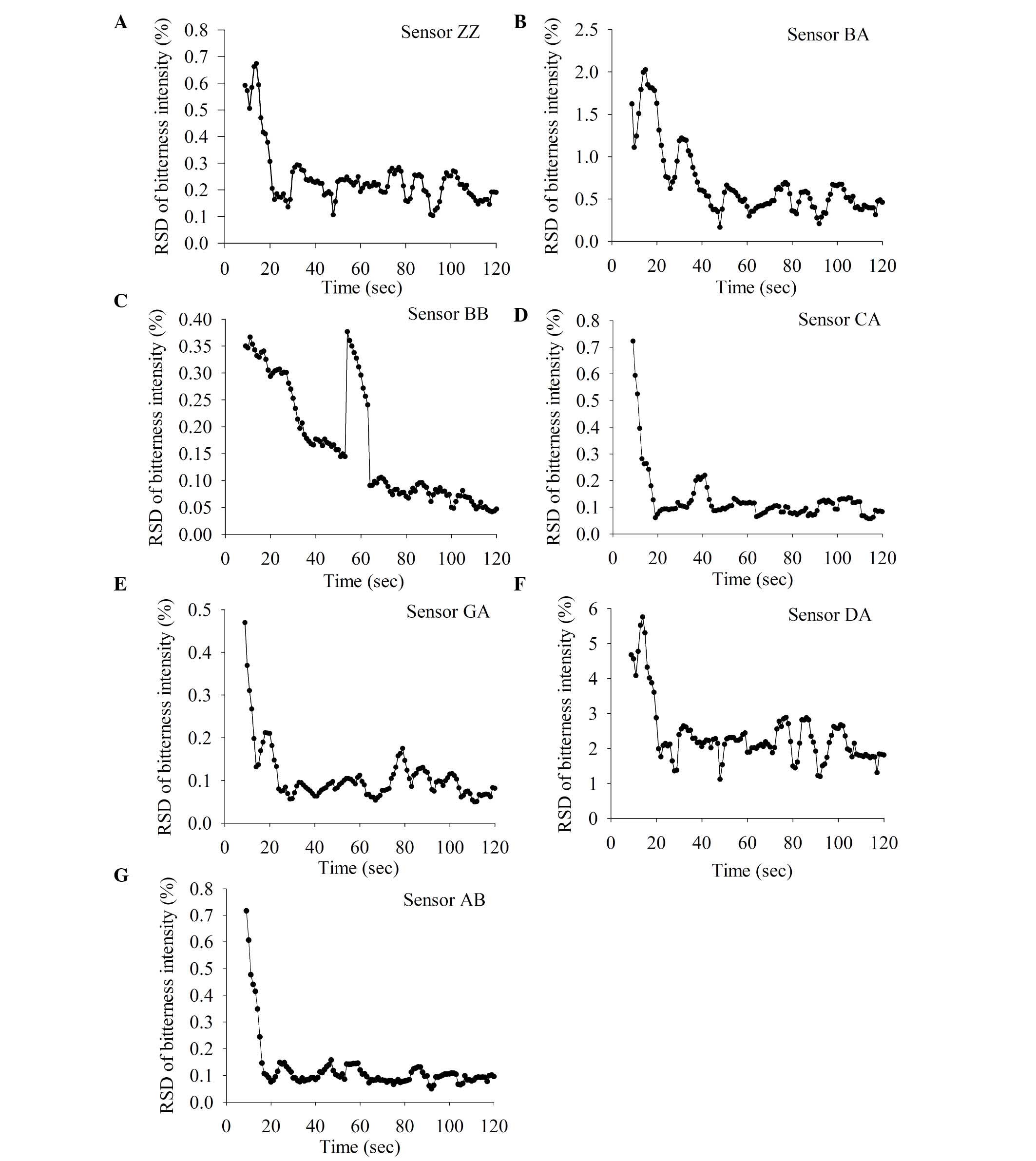

Optimization of measurement time

The aim of the present study was to identify when

E-tongue measurements become stable. This is important to assess

the validity of any future measurements, as the signal should not

be affected by noise. Firstly, sensor measurements of 0.5 mmol

caffeine solution showed the characteristic response curve of

sensors to the same solution (Fig.

1) and the signal became more stable over time. Fig. 2 shows the RSD values of the seven

different sensors to 0.5 mmol caffeine solution. The RSD decreased

over time and reached a minimum by 120 sec. So, 120 sec measurement

times were used for all subsequent measurements.

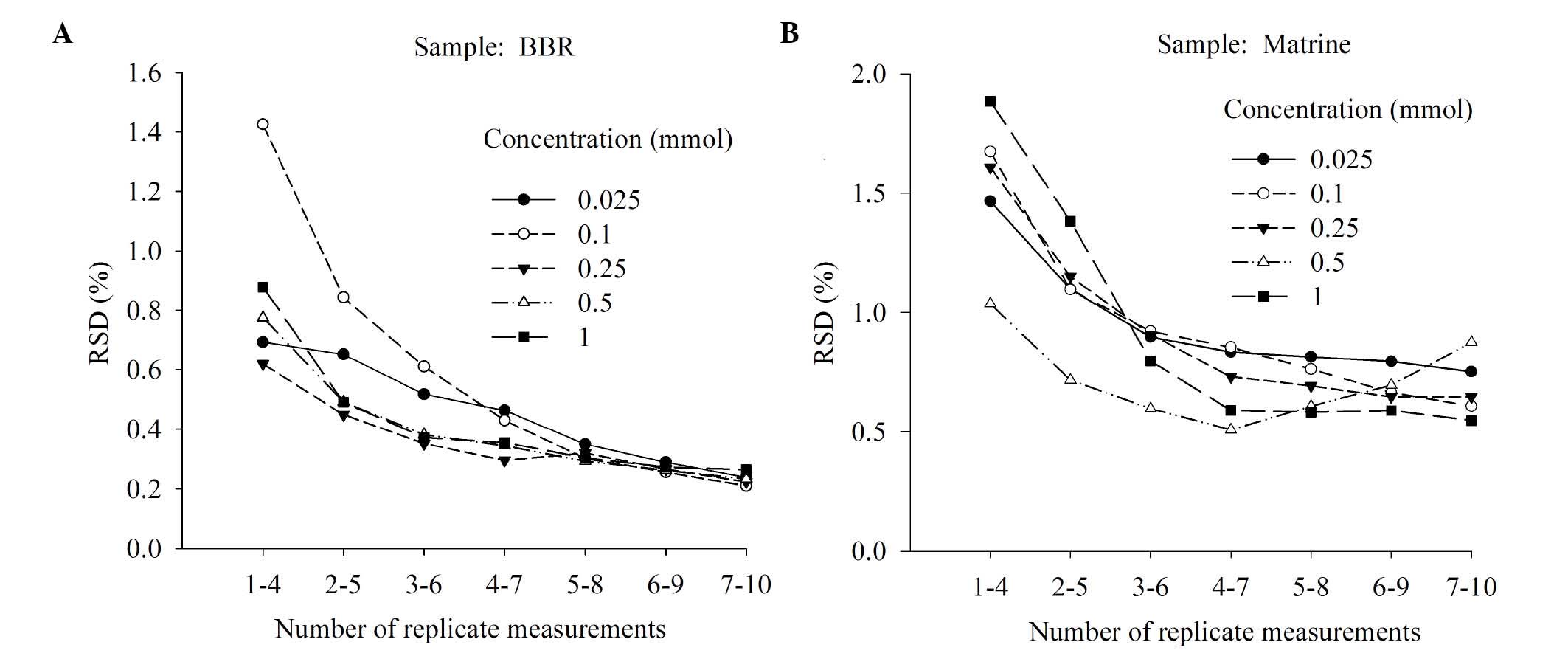

Optimization of the number of sample

measurements taken

Next, the present study investigated how many sample

measurements were required to produce a stable response signal. For

each test sample, 10 replicate measurements were taken (Fig. 3). RSD was identified to decrease as

the number of measurements taken increased. The RSD from taking 4–7

measurements was not reduced further when >7 measurements were

taken. For example, for the berberine hydrochloride sample, the RSD

values of 7 repeats and 10 repeats were 1.89 and 3.05 fold that of

3 repeats (Fig. 3A). For matrine,

the RSD values of 4–7 repeats and 7–10 repeats were 1.99 and 2.04

times higher, respectively, than that of 3–6 repeats (Fig. 3B). Therefore, the number of

measurements taken of each sample was selected to be 7. In

addition, this will minimize analysis time and extend the E-tongue

lifetime.

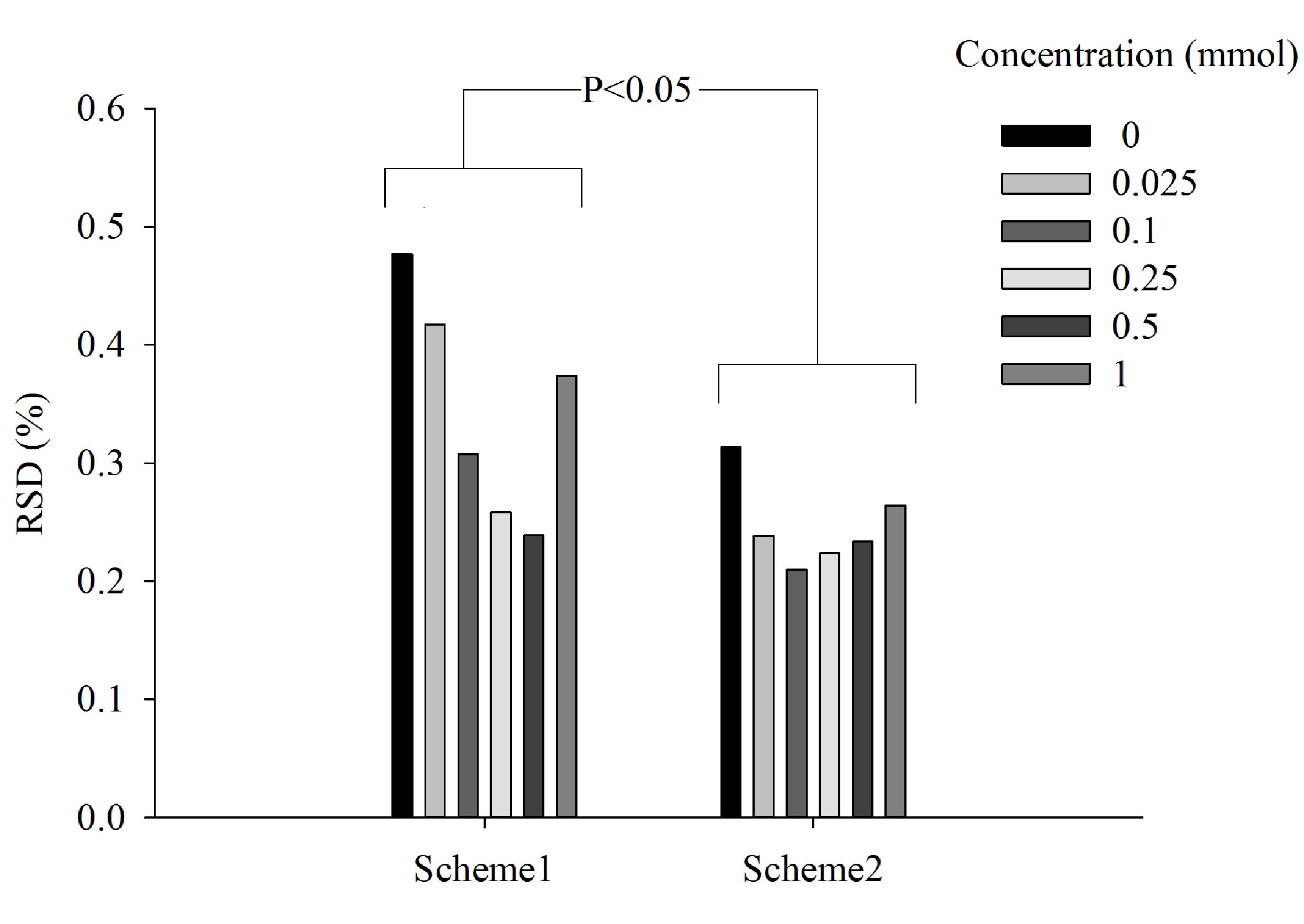

Determination of the order of E-tongue

washing and sample measurements

To determine the best approach to measurements, two

different schemes were tested on berberine hydrochloride solutions

(Fig. 4). In scheme 1 each

measurement of the same sample was followed by a single clean,

whereas in scheme 2 measurements of the same sample were taken in a

row. Scheme 2 was identified to be more stable because its RSD

values were between 1.5 and 2 fold lower compared with those from

scheme 1. The difference between the two schemes, at all respective

concentrations, was significant (P<0.05; Fig. 4). In a practical sense, the single

cleaning between each measurement used in scheme 1 required the

E-tongue to switch back and forth between the sample and its

corresponding washing cup. This was more time-consuming than the

method used in scheme 2. Thus, scheme 2 was chosen for the

remaining analysis.

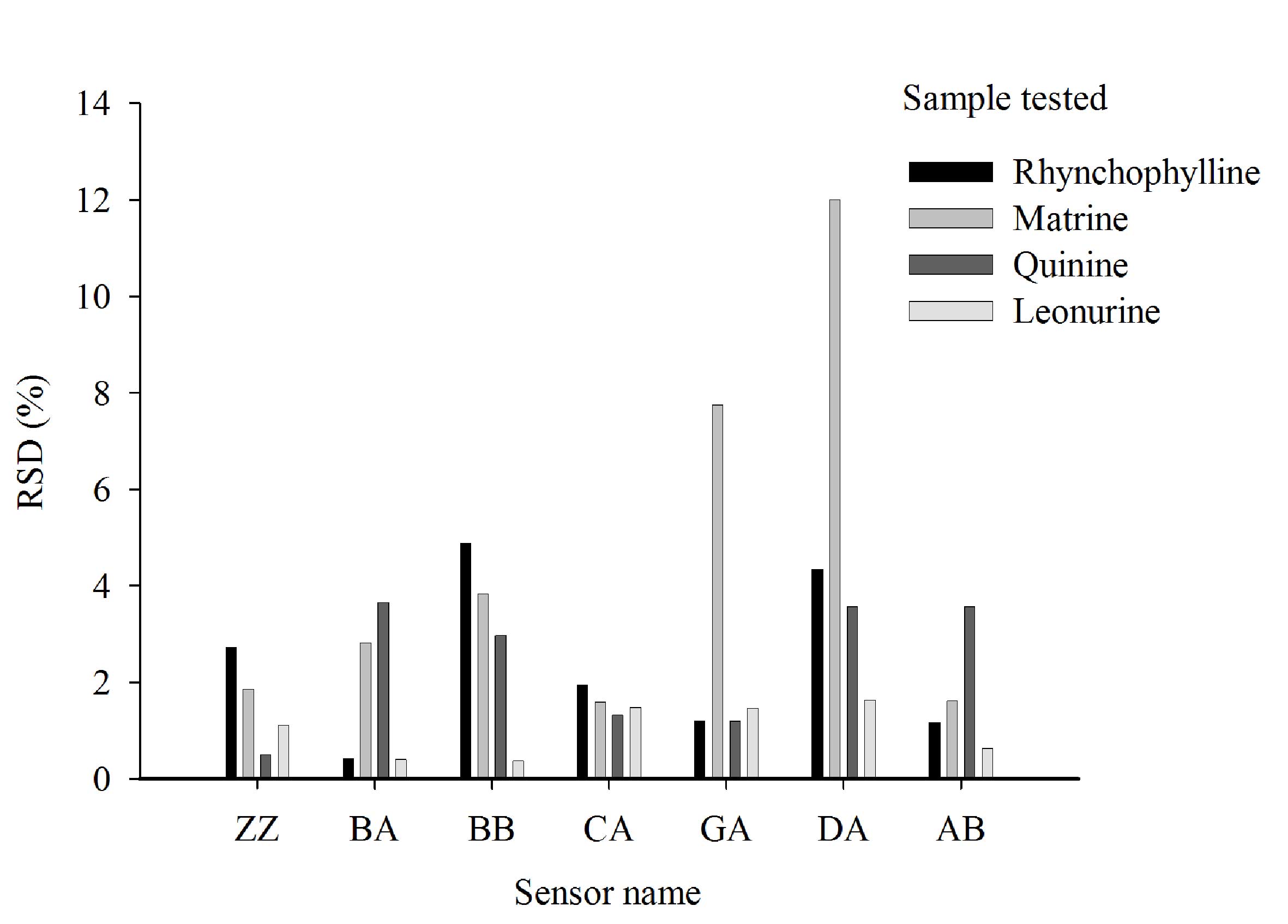

Reproducibility of results

The RSD values of the same sample in triplicate were

typically <5% for the majority of sensors (Fig. 5). However, when the sample was

matrine or quinine, the RSD values from sensors DA and GA were ≥11%

(Fig. 5). The baseline responses of

all seven sensors were normal and the E-tongue passed its

self-checking protocol. Thus, this variation is likely due to the

samples and not the E-tongue.

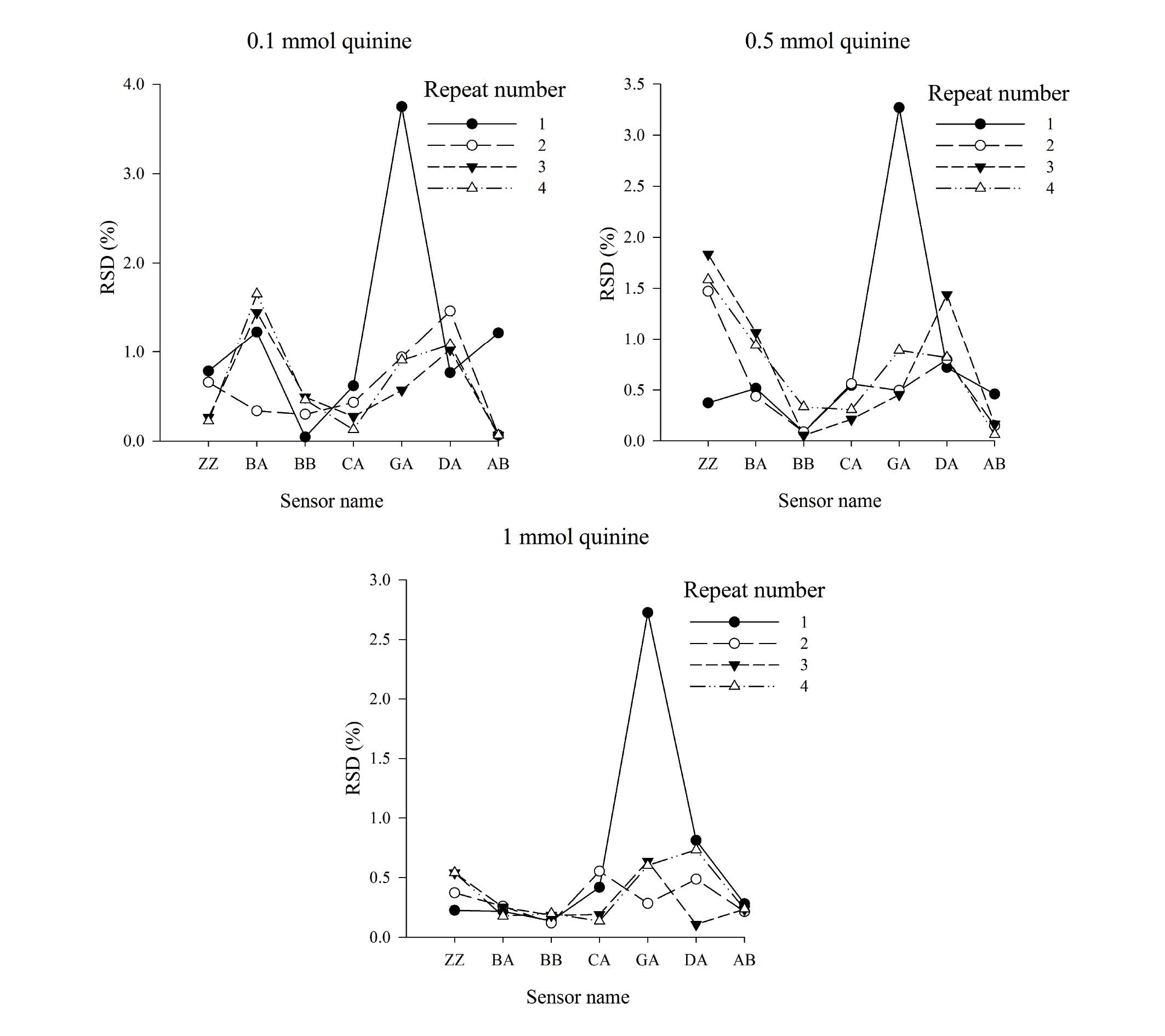

Measurement precision within a 6 h

measurement cycle

Quinine solutions at different concentrations were

measured using the E-tongue within a 6 h measurement cycle

(Fig. 6). The RSD within 6 h was

<4%, indicating that the approach was suitable for sample

analysis.

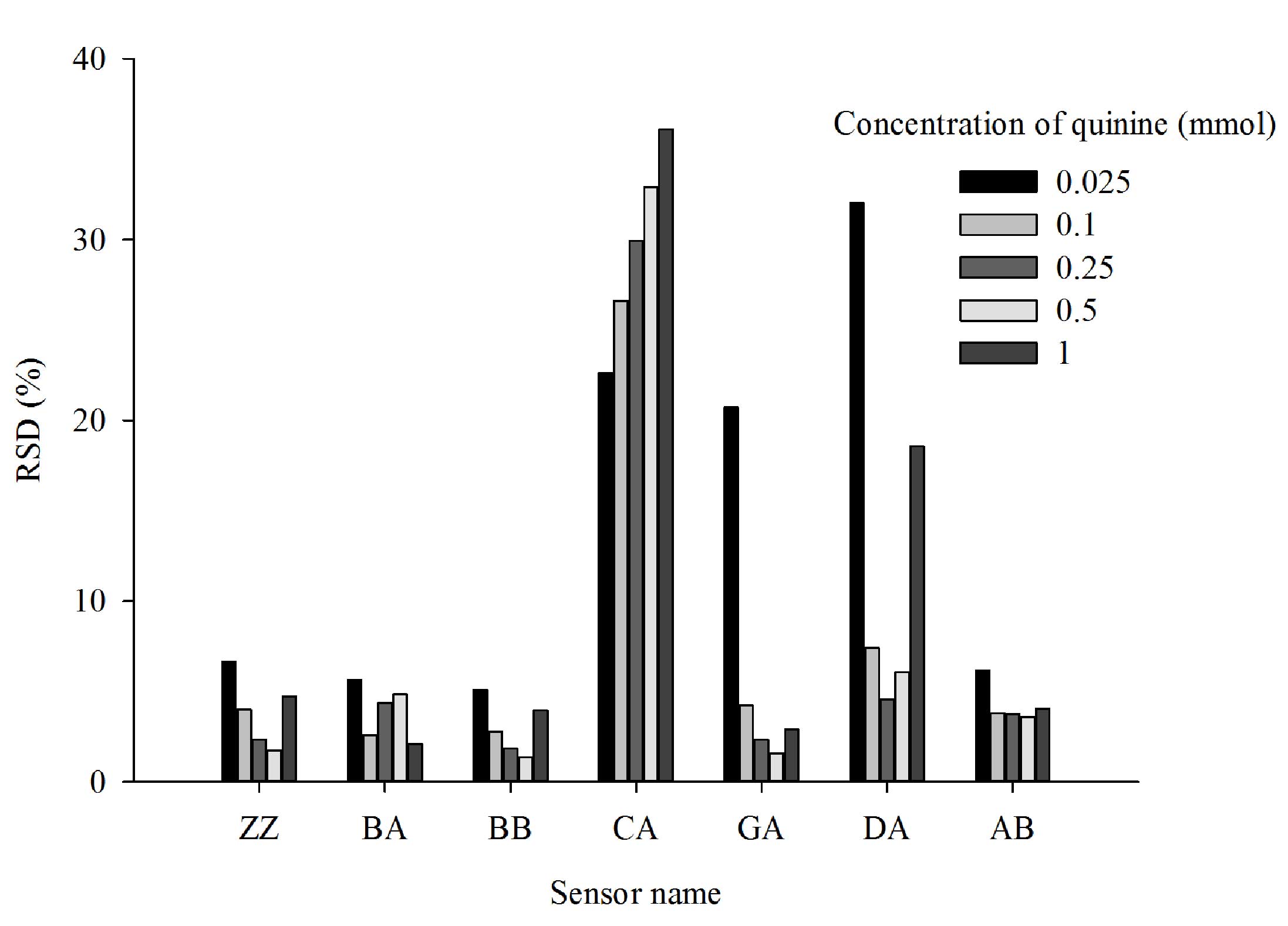

Inter-day precision of

measurements

Quinine solutions of five different concentrations

were measured using the E-tongue to evaluate the inter-day

precision of measurements (Fig. 7).

The results identified that measurements from sensors ZZ, BA, BB

and AB were relatively stable, with an RSD variation over three

days of <10%. Large variations in measurements were found for

sensors CA, GA and DA, with RSD values varying by <37%.

Therefore, subsequent measurements were taken on the same day and

in the same 6 h measurement cycle.

Analysis of the bitterness of

TCMs

In binary and tertiary classification performed with

LS-SVM, the polynomial kernel was selected following optimization.

For binary bitterness classification, all 29 samples were correctly

classified (human taste panel results), with a cross-validation

accuracy rate of 100%. For tertiary bitterness classification, 26

of the 29 samples were correctly classified, with a

cross-validation accuracy rate of 89.66%. The misclassified samples

were samples 8, 14 and 22.

In binary and tertiary classification using SVM, the

polynomial kernel was selected following optimization. For binary

classification, this approach correctly classified 28 out of 29

samples, with a cross-validation accuracy rate of 96.55%. Sample 14

was misclassified. For tertiary classification, 25 of the 29

samples were correctly classified with a cross-validation accuracy

rate of 86.21%. The misclassified samples were sample 14, 17, 22

and 23.

In binary classification of the 29 samples using DA,

26 out of 29 samples were correctly classified, with a

cross-validation accuracy rate of 89.66%. The misclassified samples

were 14, 17, and 23. For tertiary classification using DA, 26 out

of 29 samples were correctly classified, with a cross-validation

accuracy rate of 89.66%. The misclassified samples were sample 14,

17, and 22.

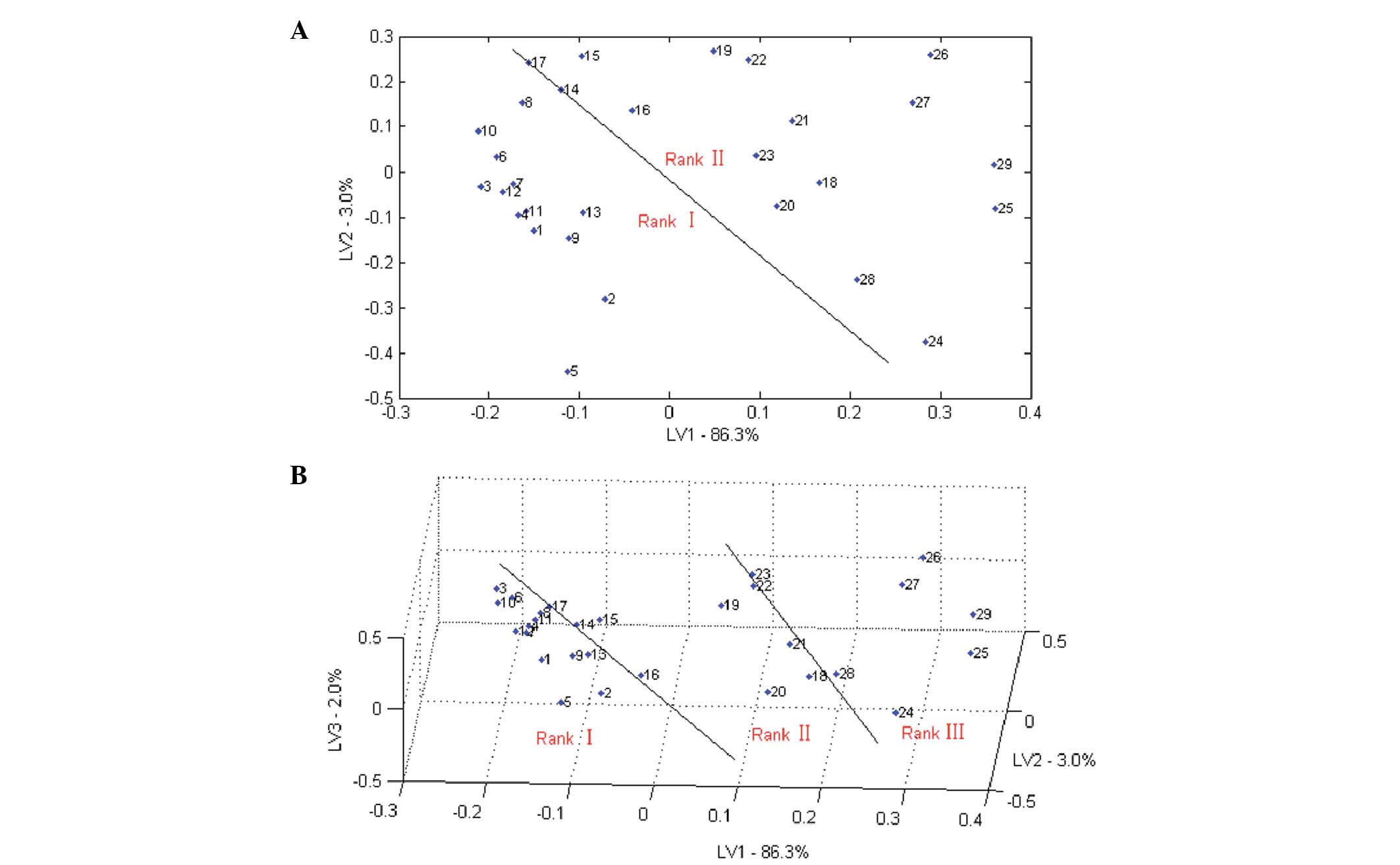

The results of two-dimensional and three-dimensional

bitterness classifications results of 29 samples based on PLS

analysis are shown in Fig. 8A and B,

respectively. The 29 samples could be grouped into two classes or

three classes. However, samples 14 and 17 were on the border of the

binary classification and samples 8, 14, 17, 22 and 23 were on the

border of the tertiary classification, so could easily be

misclassified.

In conclusion, the present study optimized the

E-tongue measurement protocol to use a 120 sec measurement

acquisition time, with 7 replicates and optimized the washing

process. The optimized washing process comprised of 6 cleans of 10

sec each. The sample solution was then measured continuously,

without cleaning in-between measurements of the same sample.

Following completion of measurements, the response values of

sensors were used for further analysis. This optimized method used

had good reproducibility and high precision within 6 h, but poor

inter-day precision. Therefore, measurements should be taken within

the same 6 h measurement cycle, rather than on different days or in

different measurement cycles.

The optimized protocol was then used to screen and

identify the bitterness intensities of 29 TCM decoctions, which

were compared to the bitterness intensities previously established

by a human taste panel. The results showed that with appropriate

data processing, the E-tongue could accurately identify the

bitterness intensity of TCM decoctions.

Acknowledgements

The present study was funded by the following

organizations: National Natural Science Foundation for Young

Scientists (grant no. 81001646); Special Program for Chinese

Medicine Research of Traditional Chinese Medicine Administration of

Henan Province (grant no. 2014ZY02066); Fundamental Research Funds

for Gifted Young Scientists at Provincial Universities by Henan

University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Zhengzhou, China; grant

no. 2014KYYWF-YQ01); and a Collaborative Project with Jiangying

Tianjiang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Jiangyin, China; grant no.

XZ2011030042). The authors thank Professor Yuan-Ying Ni and Dr Yang

Yang (College of Food Science and Nutritional Engineering, China

Agricultural University, Beijing, China) for their guidance and

help with the E-tongue.

References

|

1

|

Gupta H, Sharma A, Kumar S and Roy SK:

E-tongue: A tool for taste evaluation. Recent Pat Drug Deliv

Formul. 4:82–89. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Ayenew Z, Puri V, Kumar L and Bansal AK:

Trends in pharmaceutical taste masking technologies: A patent

review. Recent Pat Drug Deliv Formul. 3:26–39. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Ito M, Ikehama K, Yoshida K, Haraguchi T,

Yoshida M, Wada K and Uchida T: Bitterness prediction of

H1-antihistamines and prediction of masking effects of artificial

sweeteners using an electronic tongue. Int J Pharm. 441:121–127.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Anand V, Kataria M, Kukkar V, Saharan V

and Choudhury PK: The latest trends in the taste assessment of

pharmaceuticals. Drug Discov Today. 12:257–265. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

5

|

Dickinson TA, Michael KL, Kauer JS and

Walt DR: Convergent, self-encoded bead sensor arrays in the design

of an artificial nose. Anal Chem. 71:2192–2198. 1999. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Goodey A, Lavigne JJ, Savoy SM, Rodriguez

MD, Curey T, Tsao A, Simmons G, Wright J, Yoo SJ, Sohn Y, et al:

Development of multianalyte sensor arrays composed of chemically

derivatized polymeric microspheres localized in micromachined

cavities. J Am Chem Soc. 123:2559–2570. 2001. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Jokerst JV, Jacobson JW, Bhagwandin BD,

Floriano PN, Christodoulides N and McDevitt JT: Programmable

nano-bio-chip sensors: Analytical meets clinical. Anal Chem.

82:1571–1579. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Riul A Jr, Dantas CA, Miyazaki CM and

Oliveira ON Jr: Recent advances in electronic tongues. Analyst.

135:2481–2495. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Baldwin EA, Bai J, Plotto A and Dea S:

Electronic noses and tongues: Applications for the food and

pharmaceutical industries. Sensors (Basel). 11:4744–4766. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Toko K, Hara D, Tahara Y, Yasuura M and

Ikezaki H: Relationship between the amount of bitter substances

adsorbed onto lipid/polymer membrane and the electric response of

taste sensors. Sensors (Basel). 14:16274–16286. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Polshin E, Rudnitskaya A, Kirsanov D,

Legin A, Saison D, Delvaux F, Delvaux FR, Nicolaï BM and Lammertyn

J: Talanta. 81:88–94. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Peris M and Escuder-Gilabert L: On-line

monitoring of food fermentation processes using electronic noses

and electronic tongues: A review. Anal Chim Acta. 804:29–36. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Gutiérrez-Capitán M, Santiago JL,

Vila-Planas J, Llobera A, Boso S, Gago P, Martínez MC and

Jiménez-Jorquera C: Classification and characterization of

different white grape juices by using a hybrid electronic tongue. J

Agric Food Chem. 61:9325–9332. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Escuder-Gilabert L and Peris M: Review:

Highlights in recent applications of electronic tongues in food

analysis. Anal Chim Acta. 665:15–25. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Apetrei C, Apetrei IM, Villanueva S, de

Saja JA, Gutierrez-Rosales F and Rodriguez-Mendez ML: Combination

of an e-nose, an e-tongue and an e-eye for the characterisation of

olive oils with different degree of bitterness. Anal Chim Acta.

663:91–97. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Major N, Marković K, Krpan M, Sarić G,

Hruškar M and Vahčić N: Rapid honey characterization and botanical

classification by an electronic tongue. Talanta. 85:569–574. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Cetó X, Gutiérrez-Capitán M, Calvo D and

del Valle M: Beer classification by means of a potentiometric

electronic tongue. Food Chem. 141:2533–2540. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Söderström C, Borén H, Winquist F and

Krantz-Rülcker C: Use of an electronic tongue to analyze mold

growth in liquid media. Int J Food Microbiol. 83:253–261. 2003.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Zhao G, Lin X, Dou W, Tian S, Deng S and

Shi J: Use of the smart tongue to monitor mold growth and

discriminate between four mold species grown in liquid media. Anal

Chim Acta. 690:240–247. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Woertz K, Tissen C, Kleinebudde P and

Breitkreutz J: A comparative study on two electronic tongues for

pharmaceutical formulation development. J Pharm Biomed Anal.

55:272–281. 2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Harada T, Uchida T, Yoshida M, Kobayashi

Y, Narazaki R and Ohwaki T: A new method for evaluating the

bitterness of medicines in development using a taste sensor and a

disintegration testing apparatus. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo).

58:1009–1014. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Lorenz JK, Reo JP, Hendl O, Worthington JH

and Petrossian VD: Evaluation of a taste sensor instrument

(electronic tongue) for use in formulation development. Int J

Pharm. 367:65–72. 2009. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Zheng JY and Keeney MP: Taste masking

analysis in pharmaceutical formulation development using an

electronic tongue. Int J Pharm. 310:118–124. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Rachid O, Simons FE, Rawas-Qalaji M and

Simons KJ: An electronic tongue: Evaluation of the masking efficacy

of sweetening and/or flavoring agents on the bitter taste of

epinephrine. AAPS PharmSciTech. 11:550–557. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Tanigake A, Miyanaga Y, Nakamura T, Tsuji

E, Matsuyama K, Kunitomo M and Uchida T: The bitterness intensity

of clarithromycin evaluated by a taste sensor. Chem Pharm Bull

(Tokyo). 51:1241–1245. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Li L, Naini V and Ahmed SU: Utilization of

a modified special-cubic design and an electronic tongue for

bitterness masking formulation optimization. J Pharm Sci.

96:2723–2734. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Haraguchi T, Uchida T, Hazekawa M, Yoshida

M, Nakashima M, Sanda H, Hase T and Tomoda Y: Ability of food/drink

to reduce the bitterness intensity of topiramate as determined by

taste sensor analysis. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo). 64:14–20. 2016.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Yaroshenko I, Kirsanov D, Kartsova L,

Sidorova A, Sun Q, Wan H, He Y, Wang P and Legin A: Exploring

bitterness of traditional Chinese medicine samples by

potentiometric electronic tongue and by capillary electrophoresis

and liquid chromatography coupled to UV detection. Talanta.

152:105–111. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Pharmacopoeia of the People's Republic of

China 2010. 8th. I. China Medical Science and Technology Press;

Beijing: 2010

|

|

30

|

Liu R, Zhang X, Zhang L, Gao X, Li H, Shi

J and Li X: Bitterness intensity prediction of berberine

hydrochloride using an electronic tongue and a GA-BP neural

network. Exp Ther Med. 7:1696–1702. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Shi J, Zhang X, Qiu J, Li X and Liu R:

Investigation of bitter masking mechanism of β-cyclodextrin to

several traditional Chinese medicines. Zhong Guo Shi Yan Fang Ji

Xue Za Zhi. 19:1–4. 2013.(In Chinese).

|

|

32

|

Li X, Wu Z, Liu R, Xu Z, Shi J and Li H:

Study on bitterness evaluation of Chinese herbal decoction by

THTPM. Zhong Guo Shi Yan Fang Ji Xue Za Zhi. 17:11–13. 2011.(In

Chinese).

|

|

33

|

Verboven S and Hubert M: Matlab library

LIBRA. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics.

2:509–515. 2010. View

Article : Google Scholar

|

|

34

|

Verboven S and Hubert M: LIBRA: A MATLAB

library for robust analysis. Chemometr Intell Lab Syst. 75:127–136.

2005. View Article : Google Scholar

|

|

35

|

Lin Z, Zhang Q, Liu R, Gao X, Zhang L,

Kang B, Shi J, Wu Z, Gui X and Li X: Evaluation of the bitterness

of traditional Chinese medicines using an E-tongue coupled with a

robust partial least squares regression method. Sensors (Basel).

16:1512016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

36

|

Newman J, Egan T, Harbourne N, O'Riordan

D, Jacquier JC and O'Sullivan M: Correlation of sensory bitterness

in dairy protein hydrolysates: Comparison of prediction models

built using sensory, chromatographic and electronic tongue data.

Talanta. 126:46–53. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

37

|

Kuligowski J, Pérez-Guaita D and Quintás

G: Application of discriminant analysis and cross-validation on

proteomics data. Methods Mol Biol. 1362:175–184. 2016. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|