Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a common disease of the

skeletal system. As the most frequent form of joint disease, OA can

occur in any joint but primarily affects knees, hips, hands and the

spine, thus constituting a leading cause of musculoskeletal

disability worldwide (1,2). Degradation of hyaline articular

cartilage and remodeling of the subchondral bone with sclerosis are

the main features of OA (3,4). At first, patients with OA present with

joint stiffness and soreness (5).

The articulation may show some swelling caused by an effusion and

synovitis. When the bare bony surfaces grate against each other,

locking may also occur, which will cause more serious pain

(6) and will result in symptoms that

decrease quality of life. A previous epidemiological survey showed

that approximately 10% of the world's population aged over 60 years

may present with symptomatic OA (7,8).

Moreover, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), OA has

been the fourth major cause of disability for many years, with an

incidence rate of 40% in the 55–64 age group (9). As the global population mages, the

incidence of OA increases year after year. In clinical practice,

diagnosis of OA is based mainly on radiological examination and

clinical assessment, and a key point for OA diagnosis is to

identify early stage onset and progression (10). Additionally, OA is considered to be a

polygenic and multifactorial illness (11–13).

Studies have shown that age, sex, obesity, genetics, ethnicity,

behavioral influences, occupation and environmental factors, and

particularly genetic factors strongly affect the occurrence and

development of OA (14,15). Exploring the genetic factor mechanism

would prove helpful in the early diagnosis of OA.

The asporin (ASPN) gene has been reported as a

predisposing gene for OA in several previous studies and encodes a

cartilage extracellular protein belonging to the small leucine-rich

proteoglycan (SLRP) family (3).

These proteins can regulate chondrogenesis by binding to cartilage

transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and inhibiting the expression

of the TGF-β1-induced gene in cartilage (16–18). In

normal cartilage, ASPN is expressed at low levels but in OA

articular cartilage, it is abundantly expressed, thus playing a key

role in cartilage metabolism (19).

The D14 allele of ASPN has been reported as a gene potentially

contributing to knee OA (KOA), and there is a significant

difference in the allele frequency of ASPN D13 between female OA

patients and controls (20). A

number of studies have examined the association between ASPN

polymorphisms and OA, but their results and conclusions have been

contradictory. Therefore, there is not yet strong evidence of the

association between OA and ASPN. Therefore, it is necessary to

conduct additional studies to confirm the relationship between OA

and ASPN. In the present study, an updated, more comprehensive and

more detailed cumulative meta-analysis was performed based on the

newly published original studies evaluating the association between

ASPN polymorphism and OA susceptibility, to investigate whether the

D-repeat polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to OA and

whether it can provide a reference for the early diagnosis of

OA.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

To perform this meta-analysis, the Cochrane Library,

PubMed and Excerpta Medica databases (EMBASE) were used to

comprehensively search the relevant literature. The following

keywords were used: ‘(Asporin or ASPN), (Osteoarthritis or OA), and

(Asporin and ASPN or Osteoarthritis and OA)’. In addition, the

Chinese electronic databases: VIP, CNKI and Wan Fang were used to

search the relevant literature. All articles that were selected for

analysis focused on ASPN gene polymorphisms and OA susceptibility

and had been published from January 1st, 1915 through February 1st,

2017. By using the aforementioned search strategy, two authors

independently completed screening the records and then assessed the

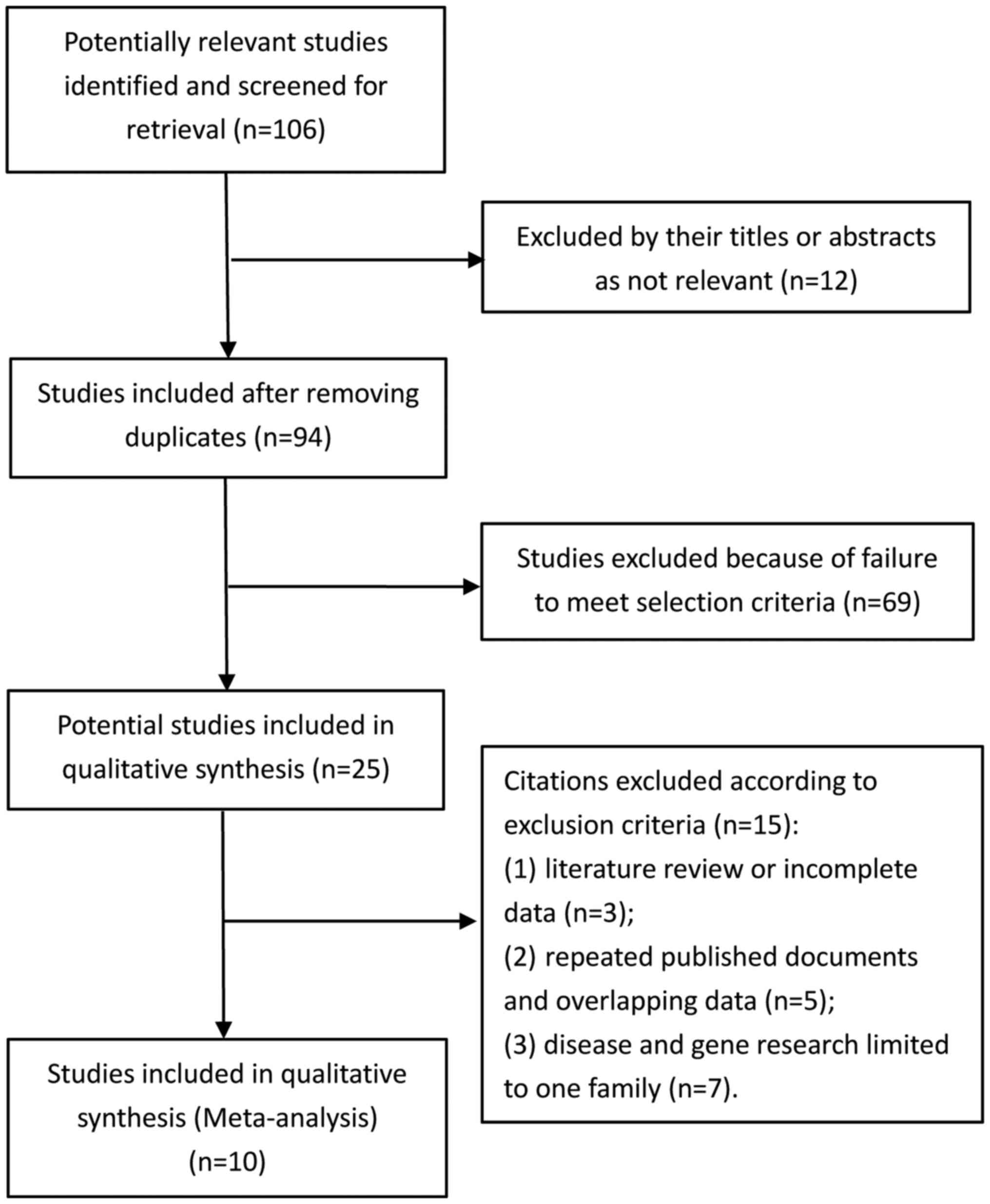

final results. The study selection flowchart is shown in Fig. 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in the meta-analysis, studies had to

meet the following criteria: i) They had to be a case-control study

(or cohort study); ii) studies had to provide data on the number of

studies and ratios, and OA diagnosis had to be performed using a

standardized method; and iii) they had to contain a study of

genotype and the ASPN allele, the relevant odds ratio (OR) and the

95% confidence interval (CI). Exclusion criteria were: i)

Literature review or incomplete data; ii) repeated published

documents and overlapping data; and iii) disease and gene research

limited to one family. There were no restrictions on the country

and language under study.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (Jing Wang and Rongqiang Zhang)

independently reviewed and extracted data from all qualified

studies. Data extraction from original studies included first

author's name, year of publication, total sample size and age of OA

patients and controls, diagnostic criteria, country where the study

was performed, ethnicity of the participants, OA sites and genotype

frequencies of the two groups. The continent of origin was

categorized as follows: Europe or America (=1) and Asia (=2). Total

sample sizes of OA patients and controls were categorized as

<1,000 (=1) and ≥1,000 (=2). Moreover, OA sites were categorized

as KOA (=1) and hand or hip OA (=2). The two investigators

carefully checked the data extraction information and reached

consensus to ensure accuracy of the extracted data. In the case of

disagreement, the two reviewers double-checked the original data

together and then discussed them in order to reach an agreement. If

they failed to reach an agreement, a third reviewer (Aimin Yang)

was invited to the discussion.

Methodological quality assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies

was independently assessed by two reviewers (Jing Wang and

Rongqiang Zhang), according to our revised Scale for Quality

Assessment (Table I) based on the

scales of Thakkinstian et al (21) and Qin et al (22). The revised scale covered criteria

such as representativeness of cases, credibility of controls,

ascertainment of OA, genotyping examination, Hardy-Weinberg

equilibrium (HWE) and association assessment. Any disagreement

related to methodological quality was resolved by consensus. Scores

ranged from 0 to 12. Articles that were assigned a score <8 were

considered ‘low-quality’ studies, whereas papers with a score ≥8

were considered ‘high-quality’ studies.

| Table I.Scale for quality assessment. |

Table I.

Scale for quality assessment.

| Criteria | Score |

|---|

| Representativeness

of cases |

|

|

Selected from population | 2 |

|

Selected from any OA/surgery

service | 1 |

|

Selected without clearly

defined sampling frame or with extensive inclusion/exclusion

criteria | 0 |

| Credibility of

controls |

|

|

Population-or

neighbor-based | 3 |

| Blood

donors or volunteers | 2 |

|

Hospital-based (Joint

diseases-free patients) | 1 |

| Healthy

volunteers, but without total description | 0.5 |

| Not

described | 0 |

| Ascertainment of

OA |

|

|

Clinical and X-ray or MRI

confirmation | 2 |

|

Diagnosis of OA by patient

medical record | 1 |

| Not

described | 0 |

| Genotyping

examination |

|

|

Genotyping done under

‘blinded’ condition | 1 |

|

Unblinded or not

mentioned | 0 |

| Hardy-Weinberg

equilibrium |

|

|

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in

controls | 2 |

|

Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium

in controls | 1 |

| No

checking for Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium | 0 |

| Association

assessment |

|

| Assess

association between genotypes and OA with appropriate statistics

and adjustment for confounders | 2 |

| Assess

association between genotypes and OA with appropriate statistics

without adjustment for confounders | 1 |

|

Inappropriate statistics

used | 0 |

Statistical analysis

RevMan software v5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration,

Oxford, UK) was used to perform the meta-analysis. When the

selected original studies met the criteria for homogeneity

(I2<50% or P>0.05), a fixed-effects model

was chosen to conduct the meta-analysis. If they met the criteria

for heterogeneity (I2>50% or P<0.05), a

random-effects model was chosen to conduct the meta-analysis.

Univariate and multivariate meta-regression analyses were then

performed to explore the source of heterogeneity between studies

using Stata 13.0 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA).

In meta-regression analyses, LogOR (where OR stands for the

relevant OR of cases vs. control) was taken as the dependent

variable. The sample size, OA sites and continent of origin were

taken as independent variables. If necessary, a subgroup analysis

was conducted according to the source of heterogeneity. Publication

bias was analyzed with a funnel plot and Begg's test.

Results

Literature search and study

selection

A total of 34,084 relevant articles were searched

from the Cochrane Library, PubMed, the Excerpta Medica database,

VIP, CNKI and Wan Fang. Finally, 10 articles including 11 studies

(Kizawa's research included both an independent case-control study

and an independent cohort study) were included in our

meta-analysis.

Study characteristics

In total, 8,503 participants (4,842 OA patients and

3,661 controls) were eligible for inclusion, involving three

different regions, each of which encompassed a distinct human race,

and four types of OA pathogenesis research. Cohort studies included

137 patients and 234 controls while case-control studies comprised

4,705 patients and 3,427 controls. A total of 4 articles focused on

Asians, 4 on Europeans and 2 on Americans. Among them, 7 studies

examined KOA and 4 studies focused on hand or hip OA. Participants

included in both case and control groups were all OA patients and

healthy controls confirmed by standard diagnostic criteria (K/L

grading system5, Criteria of American Rheumatology

College, clinical and radiologic diagnosis), respectively.

Polymorphisms of the ASPN gene were detected using multiplex

polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and single nucleotide polymorphism

(SNP) analyses, which were performed using the GenomeLab SNPstream

Genotyping System (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). The

characteristics of all included studies are presented in Table II.

| Table II.Baseline characteristics of the 10

articles (including 11 studies) included in the meta-analysis. |

Table II.

Baseline characteristics of the 10

articles (including 11 studies) included in the meta-analysis.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OA | Control |

|

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Author year | Design | Na (OA/Control) | Ageb (OA/Control) | Diagnostic

criteriac | Country | Ethnicity | OA site | D12 | D13 | D14 | D15 | D16 | D17 | D18 | Others | D12 | D13 | D14 | D15 | D16 | D17 | D18 | Others | Score | HWE | (Refs.) |

|---|

| Mustafa 2005 | Case-control | 1,247/748 | 65.0/69.0 | KL grade

system | UK | Caucasians | Hip/Knee | 130 | 1,183 | 352 | 498 | 216 | 60 | 34 | 5 | 76 | 752 | 190 | 289 | 124 | 26 | 22 | 7 | 9 | No | (18) |

| Kizawa 2005 | Case-control | 986/374 | 65.4/28.8 | KL grade

system | Japan | Honshu | Knee/Hip | – | 1,190 | 154 | – | – | – | – | 628 | – | 479 | 36 | – | – | – | – | 233 | 12 | Yes | (27) |

| Kizawa 2005 | Cohort | 137/234 | 75.3/73.6 | KL grade

system | Japan | Honshu | Knee | – | 163 | 30 | – | – | – | – | 81 | – | 314 | 22 | – | – | – | – | 132 | 12 | Yes | (27) |

| Jiang 2006 | Case-control | 218/454 | 58.1/56.3 | KL grade

system | China | Han | Knee | 61 | 300 | 41 | 11 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 186 | 604 | 44 | 29 | 39 | 3 | 3 | – | 11 | Yes | (28) |

| Kaliakatsos

2006 | Case-control | 155/190 | 70.3/69.1 | KL grade

system | Greece | Thessaly | Knee | 20 | 118 | 47 | 84 | 20 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 17 | 189 | 53 | 74 | 30 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 7 | No | (29) |

| Duval 2006 | Case-control | 723/294 | 65/> 55 | ACR criteria | Spanish | Caucasians | Hip/Knee/Hand | 52 | 627 | 172 | 362 | 144 | 40 | 28 | 23 | 31 | 248 | 74 | 150 | 55 | 12 | 10 | 8 | 6 | No | (26) |

| Atif 2008 | Case-control | 775/551 | 77.8/69.0 | KL grade

system | USA | Caucasian | Hand/Knee | – | 750 | 206 | 169 | – | – | – | – | – | 268 | 77 | 114 | – | – | – | – | 10 | No | (19) |

| Song 2008 | Case-control | 190/376 | 60/47.7 | Radiology and

pathology | Korean | – | Knee | 60 | 265 | 22 | 13 | 15 | 5 | – | – | 118 | 483 | 65 | 28 | 51 | 7 | – | – | 9 | No | (30) |

| Arellano 2013 | Case-control | 218/222 | 57.99/52.67 | KL grade

system | Mexico | Torreon

Coahuila | Knee | 12 | 205 | 91 | 69 | 38 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 32 | 204 | 107 | 66 | 22 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 10 | Yes | (31) |

| Jazayeri 2013 | Case-control | 100/100 | 62.5/63 | Clinical and

radiologic diagnosis | Iranians | Fars | Knee | 4 | 82 | 32 | 52 | 22 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 91 | 40 | 45 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 7 | No | (3) |

| Juchtmans 2015 | Case-control | 93/118 | 56.4/51.8 | Clinical and

radiologic diagnosis | Mexico | Mexican

mestizo | Knee | – | 7 | 123 | 25 | 21 | 9 | – | 1 | – | 6 | 134 | 47 | 32 | 16 | – | 1 | 12 | Yes | (4) |

Methodological quality

Studies were generally of good quality with a mean

score of 9.55 (Table II), of which

eight studies (66.67%) had a score equal to or greater than 8,

while the three other studies (33.33%) received a score lower than

8. Two-thirds of the studies included in this meta-analysis were

thus classified as of high quality.

Results of overall meta-analysis

The association between ASPN polymorphisms and

susceptibility to OA is shown in Table

III. The results of the analyses of heterogeneity showed that

there was heterogeneity on D12 in seven studies (P=0.02,

I2=62%), on D13 (P=0.01,

I2=55%) and D14 (P=0.0001,

I2=71%) in eleven studies, and on D15 (P=0.005,

I2=63%) in nine studies. Therefore,

random-effects models were used for the meta-analysis of D12-D15.

There was no significant heterogeneity on either D16 (P=0.07,

I2=47%) or D17 (P=0.37, I2=8%)

in eight studies, or on D18 (P=0.38, I2=6%) in

six studies. Consequently, fixed-effects models were used to

calculate the pooled ORs of D16, D17 and D18. The pooled OR and its

95% CI for the D17 allele vs. others combined indicated that D17

alleles were a statistically significant risk factor for OA

development (OR=1.33, 95% CI: 1.02–1.73). No statistically

significant association was found between OA and ASPN D12, D13,

D14, D15, D16 or D18 alleles.

| Table III.Summary of ORs and 95% CIs of the

ASPN polymorphisms and OA susceptibility. |

Table III.

Summary of ORs and 95% CIs of the

ASPN polymorphisms and OA susceptibility.

|

|

| Sample size | Test of

association | Test of

heterogeneity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Comparisons | No. of studies | OA | Control | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Modela | P-value |

I2 (%) |

|---|

| D12 vs. all the

others | 7 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.07 | 0.14 | R | 0.02 | 62 |

| D13 vs. all the

others | 11 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.05 | 0.25 | R | 0.01 | 55 |

| D14 vs. all the

others | 11 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.15 | 0.94–1.40 | 0.17 | R |

0.0001 | 71 |

| D15 vs. all the

others | 9 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.97 | 0.70–1.15 | 0.71 | R | 0.005 | 63 |

| D16 vs. all the

others | 8 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.03 | 0.89–1.19 | 0.72 | F | 0.07 | 47 |

| D17 vs. all the

others | 8 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.33 |

1.02–1.73 | 0.04 | F | 0.37 | 8 |

| D18 vs. all the

others | 6 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.07 | 0.72–1.59 | 0.75 | F | 0.38 | 6 |

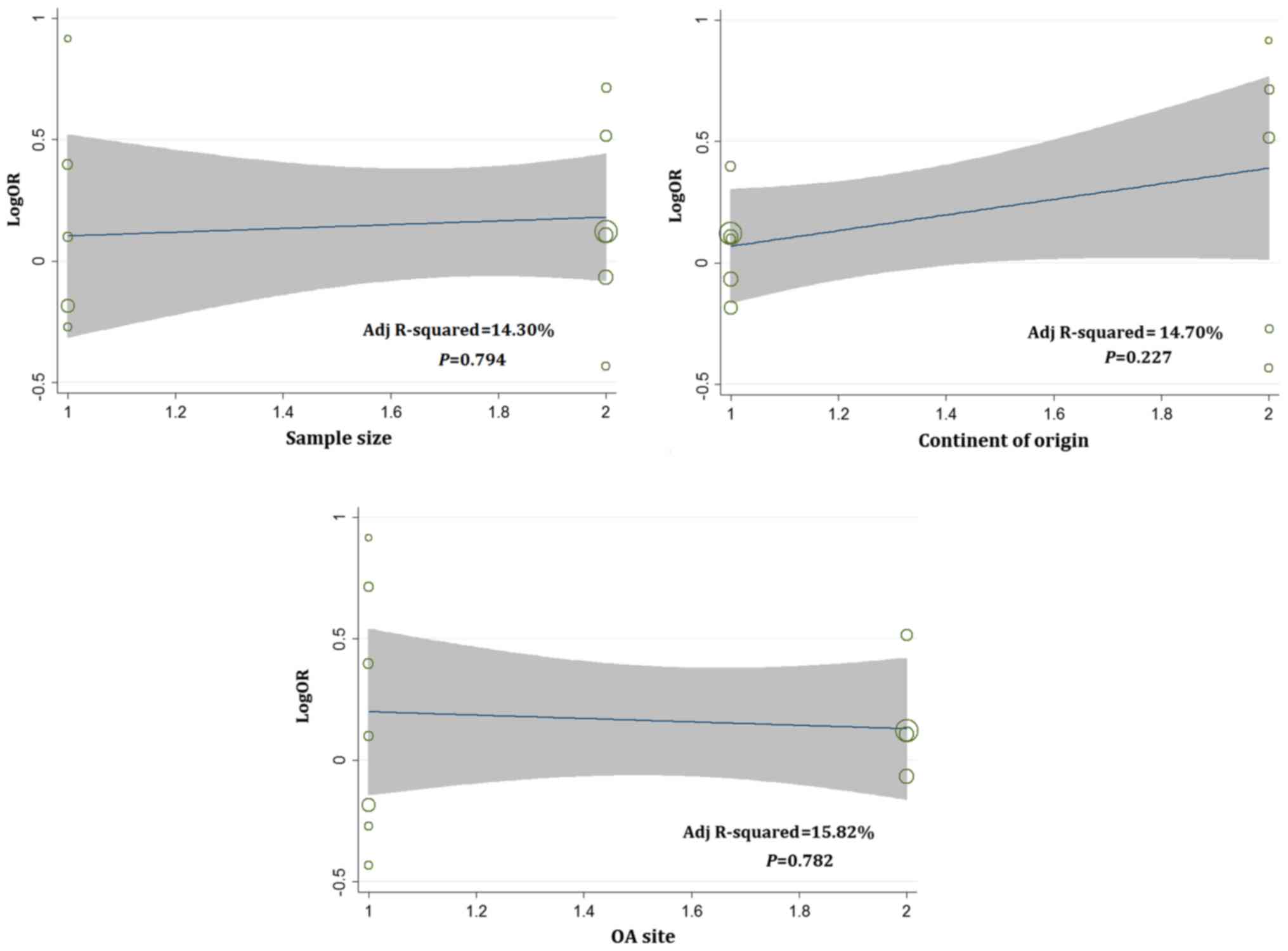

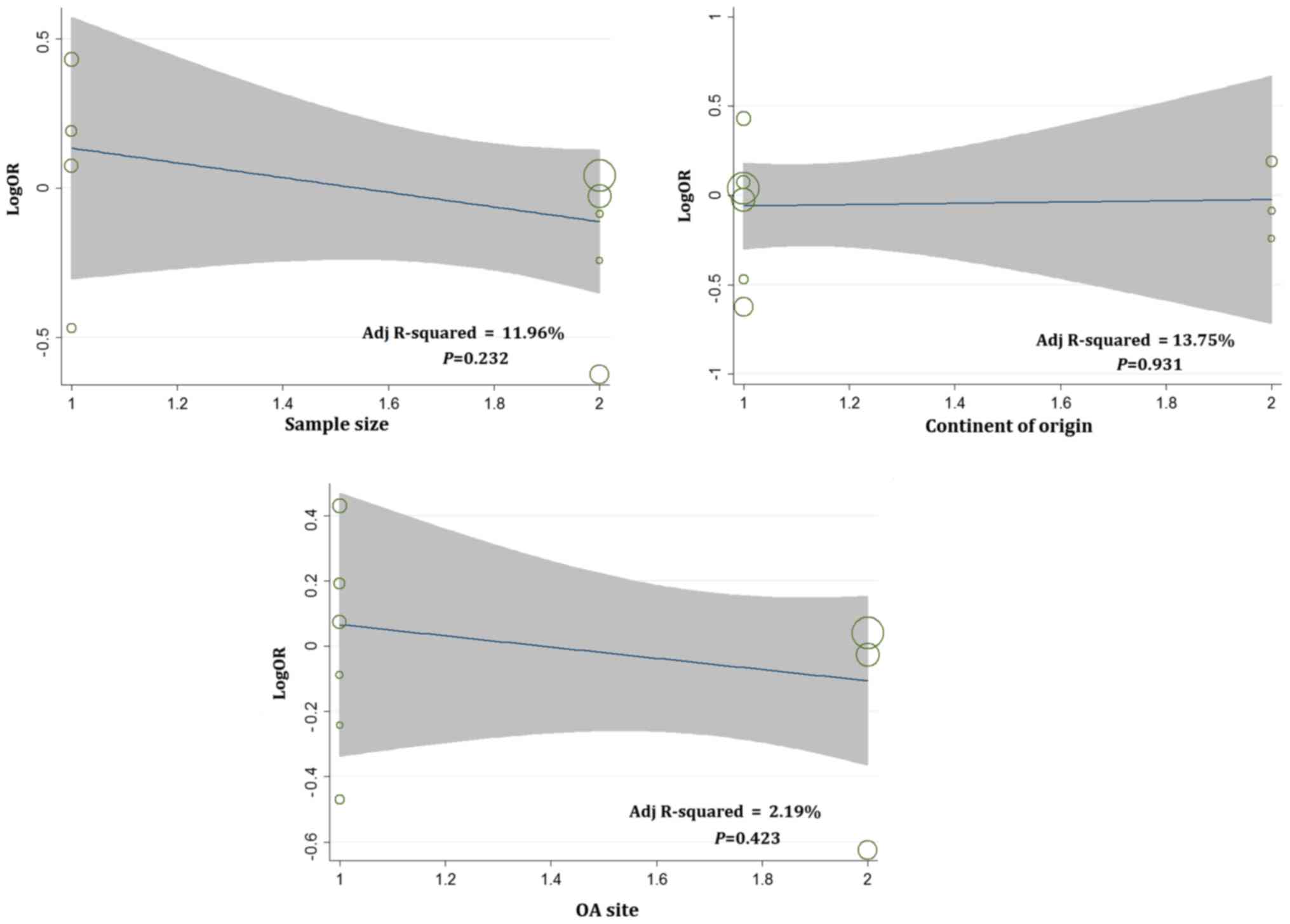

Test of heterogeneity

Because the included studies showed significant

heterogeneity for D12, D13, D14 and D15, univariate and

multivariate meta-regression analyses were performed to explore the

source of this heterogeneity. For the reason that the number of

studies focusing on D12 was only 7 and the frequency of D12 alleles

reported in the original studies was small, meta-regression

analyses were only conducted on D13, D14 and D15. Meta-regression

analyses were conducted according to a random-effects model.

Univariate analyses were performed separately for the following

variables: sample size, continent of origin and OA site. Therefore

results showed that there was no statistically significant

association between independent variables (sample size, continent

of origin and OA site) and the dependent variable (LogOR) for D13,

D14, and D15 (Figs. 2–4). However, judging from adjusted R-squared

values, the sample size, continent of origin and OA site could all

impact the development of OA to a certain degree (Figs. 2–4).

Multivariate analysis results showed that sample size played a role

in the association between D13 and OA risk (P=0.039; Table IV).

| Table IV.Multivariate meta-regression analysis

of the association between D13, D14, D15 and the risk of OA. |

Table IV.

Multivariate meta-regression analysis

of the association between D13, D14, D15 and the risk of OA.

| Genotype | Dependent

variablesa | OR | SE | t | P-value | 95% CI |

|---|

| D13 | Continent of

origin | 0.8417473 | 0.1296135 | −1.12 | 0.296 | 0.5901624,

1.200582 |

|

| OA site | 0.7689406 | 0.1452108 | −1.39 | 0.202 | 0.4974702,

1.188553 |

|

| N | 1.576952 | 0.290733 |

2.47 | 0.039 |

1.030815, 2.412438 |

| D14 | Continent of

origin | 1.366192 | 0.4471786 |

0.95 | 0.368 | 0.6422559,

2.906132 |

|

| OA site | 1.054285 | 0.4480117 |

0.12 | 0.904 | 0.3957158,

2.808876 |

|

| N | 0.9812867 | 0.3917458 | −0.05 | 0.963 | 0.3908288,

2.463799 |

| D15 | Continent of

origin | 1.147952 | 0.5037435 |

0.31 | 0.764 | 0.3922823,

3.359297 |

|

| OA site | 1.145223 | 0.6270224 |

0.25 | 0.813 | 0.2999584,

4.372395 |

|

| N | 0.6839221 | 0.3202035 | −0.81 | 0.448 | 0.2175071,

2.150502 |

Subgroup analysis

After meta-regression analysis, we conducted a

subgroup analysis according to study sample size. Indeed, when

sample size was greater than 1,000 the heterogeneity of the D13

gene decreased and became not statistically significant (both

Ps=0.08). The results indicated that when the sample size

>1,000, D17 alleles increased the risk for the development of OA

(OR=1.46, 95% CI: 1.03–2.07, P<0.05; Table V). There was no significant

association between the other ASPN polymorphisms (D12, D13, D14,

D15, D16, D18) and OA in the other subgroup analyses (Tables VI and VII). According to the score of the

included studies, we performed a subgroup analysis with score ≥8

and score <8 and the results are presented in Table VIII, which indicated that when

study design and quality score >8, D17 alleles increased the

risk for OA (OR=1.45, 95% CI: 1.04–2.02, P<0.05).

| Table V.Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to sample

size. |

Table V.

Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to sample

size.

|

|

|

| Sample size | Test of

association | Test of

heterogeneity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Comparison | Sample size | No. of studies | OA | Control | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Modela | P-value | I2

(%) |

|---|

| D12 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 3 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 0.79 | 0.29–2.17 | 0.65 | R | 0.01 | 76 |

|

| >1,000 | 4 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 0.83 | 0.64–1.08 | 0.16 | R | 0.07 | 57 |

| D13 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 5 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 0.81 | 0.64–1.03 | 0.09 | R | 0.08 | 51 |

|

| >1,000 | 6 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0.87 | F | 0.08 | 49 |

| D14 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 5 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 1.18 | 0.81–1.72 | 0.39 | R | 0.005 | 73 |

|

| >1,000 | 6 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 1.14 | 0.89–1.45 | 0.32 | R | 0.001 | 75 |

| D15 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 4 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 1.09 | 0.78–1.54 | 0.60 | R | 0.05 | 62 |

|

| >1,000 | 5 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 0.89 | 0.73–1.09 | 0.25 | R | 0.04 | 61 |

| D16 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 4 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 1.21 | 0.90–1.62 | 0.21 | R | 0.06 | 60 |

|

| >1,000 | 4 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 0.97 | 0.82–1.15 | 0.75 | F | 0.22 | 33 |

| D17 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 4 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 1.15 | 0.30–1.62 | 0.52 | F | 0.16 | 43 |

|

| >1,000 | 4 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 1.46 |

1.03–2.07 | 0.03 | F | 0.68 | 0 |

| D18 vs. the

others | <1,000 | 2 | 1,460 | 1,728 | 2.21 | 0.68–7.20 | 0.19 | R | 0.10 | 57 |

|

| >1,000 | 2 | 8,278 | 5,594 | 0.96 | 0.72–1.47 | 0.86 | F | 0.66 |

|

| Table VI.Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to OA site. |

Table VI.

Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to OA site.

|

|

|

| Sample size | Test of

association | Test of

heterogeneity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Comparison | OA site | No. of studies | OA | Control | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Modela | P-value |

I2 (%) |

|---|

| D12 vs. all the

others | Knee | 5 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 0.79 | 0.51–1.20 | 0.27 | R | 0.01 | 68 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 2 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 0.86 | 0.57–1.30 | 0.48 | R | 0.12 | 58 |

|

| Overall | 7 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.07 | 0.14 | R | 0.02 | 62 |

| D13 vs. all the

others | Knee | 7 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 0.93 | 0.75–1.16 | 0.54 | R | 0.005 | 68 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 4 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 0.93 | 0.86–1.02 | 0.12 | F | 0.33 | 12 |

|

| Overall | 11 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.05 | 0.25 | R | 0.01 | 55 |

| D14 vs. all the

others | Knee | 7 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 1.18 | 0.83–1.68 | 0.35 | R | 0.35 | 77 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 4 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 1.10 | 0.90–1.36 | 0.35 | R | 0.05 | 62 |

|

| Overall | 11 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.15 | 0.94–1.40 | 0.17 | R |

0.0001 | 71 |

| D15 vs. all the

others | Knee | 6 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 1.04 | 0.80–1.36 | 0.76 | F | 0.10 | 45 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 3 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 0.89 | 0.70–1.15 | 0.37 | R |

0.007 | 80 |

|

| Overall | 9 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.97 | 0.70–1.15 | 0.71 | R |

0.005 | 63 |

| D16 vs. all the

others | Knee | 6 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 0.98 | 0.77–1.25 | 0.88 | R | 0.02 | 62 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 2 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 1.06 | 0.88–1.28 | 0.57 | F | 0.92 | 0 |

|

| Overall | 8 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.03 | 0.89–1.19 | 0.72 | F | 0.07 | 47 |

| D17 vs. all the

others | Knee | 6 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 1.27 | 0.87–1.85 | 0.22 | F | 0.19 | 33 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 2 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 1.38 | 0.95–2.02 | 0.09 | F | 0.96 | 0 |

|

| Overall | 8 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.33 |

1.02–1.73 | 0.04 | F | 0.37 | 8 |

| D18 vs. all the

others | Knee | 4 | 2,222 | 3,388 | 1.51 | 0.55–4.11 | 0.42 | F | 0.14 | 45 |

|

| Knee/Hand/Hip | 2 | 7,462 | 3,934 | 1.00 | 0.65–1.54 | 1.00 | F | 0.65 | 0 |

|

| Overall | 6 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.07 | 0.72–1.59 | 0.75 | F | 0.38 | 6 |

| Table VII.Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to continent of

origin. |

Table VII.

Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to continent of

origin.

|

|

|

| Sample size | Test of

association | Test of

heterogeneity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Comparison | Continent of

origin | No. of studies | OA | Control | OR | 95% CI | P-value | Modela | P-value |

I2 (%) |

|---|

| D12 vs. all the

others | Asia | 3 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 0.81 | 0.55–1.18 | 0.26 | R | 0.13 | 50 |

|

| Europe | 3 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 0.96 | 0.66–1.40 | 0.85 | R | 0.12 | 52 |

|

| America | 1 |

622 |

680 | 0.36 | 0.19–0.72 | 0.003 | – | – | – |

|

| Overall | 7 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.81 | 0.61–1.07 | 0.14 | R | 0.02 | 62 |

| D13 vs. all the

others | Asia | 5 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 0.95 | 0.78–1.16 | 0.61 | R | 0.02 | 65 |

|

| Europe | 4 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 0.90 | 0.77–1.06 | 0.21 | R | 0.03 | 67 |

|

| America | 2 |

622 |

680 | 1.06 | 0.82–1.38 | 0.63 | F | 0.53 | 0 |

|

| Overall | 11 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.05 | 0.25 | R | 0.01 | 55 |

| D14 vs. all the

others | Asia | 5 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 1.34 | 0.39–1.07 | 0.25 | R | 0.0002 | 82 |

|

| Europe | 4 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 1.03 | 0.91–1.17 | 0.62 | F | 0.57 | 0 |

|

| America | 2 |

622 |

680 | 1.10 | 0.62–1.94 | 0.75 | R | 0.03 | 80 |

|

| Overall | 11 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.15 | 0.94–1.40 | 0.17 | R | 0.0001 | 71 |

| D15 vs. all the

others | Asia | 3 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 1.03 | 0.73–1.43 | 0.88 | F | 0.56 | 0 |

|

| Europe | 4 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 0.99 | 0.76–1.30 | 0.97 | R | 0.0005 | 83 |

|

| America | 2 |

622 |

680 | 0.85 | 0.50–1.44 | 0.54 | R | 0.10 | 64 |

|

| Overall | 9 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 0.97 | 0.81–1.16 | 0.71 | R | 0.005 | 63 |

| D16 vs. all the

others | Asia | 3 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 0.86 | 0.61–1.23 | 0.41 | R | 0.03 | 70 |

|

| Europe | 3 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 1.03 | 0.86–1.23 | 0.75 | F | 0.68 | 0 |

|

| America | 2 |

622 |

680 | 1.26 | 0.86–1.87 | 0.24 | R | 0.05 | 75 |

|

| Overall | 8 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.03 | 0.89–1.19 | 0.72 | F | 0.07 | 47 |

| D17 vs. all the

others | Asia | 3 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 1.63 | 0.81–3.28 | 0.17 | F | 0.48 | 0 |

|

| Europe | 3 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 1.26 | 0.89–1.77 | 0.19 | F | 0.52 | 0 |

|

| America | 2 |

622 |

680 | 1.32 | 0.38–4.57 | 0.66 | R | 0.04 | 77 |

|

| Overall | 8 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.32 | 0.99–1.77 | 0.06 | F | 0.37 | 8 |

| D18 vs. all the

others | Asia | 2 | 3,262 | 3,076 | 0.31 | 0.03–2.75 | 0.29 | F | 0.96 | 0 |

|

| Europe | 3 | 5,800 | 3,566 | 1.16 | 0.76–1.77 | 0.49 | F | 0.14 | 49 |

|

| America | 1 |

622 |

680 | 0.51 | 0.05–5.62 | 0.58 | – | – | – |

|

| Overall | 6 | 9,684 | 7,322 | 1.07 | 0.72–1.59 | 0.75 | F | 0.38 | 6 |

| Table VIII.Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to study design

and quality scores. |

Table VIII.

Subgroup analysis of pooled ORs and

95% CIs of ASPN polymorphisms and OA risk according to study design

and quality scores.

|

|

|

| Sample size | Test of

association | Test of

heterogeneity |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|---|

| Comparison | Scores | No. of studies | OA | Control | ORa | OR 95%

CIb | P-value | Modelc | P-value |

I2 (%) |

|---|

| D12 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 4 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 0.75 | 0.52–1.09 | 0.14 | R | 0.008 | 75 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 0.94 | 0.53–1.67 | 0.84 | F | 0.02 | 46 |

| D13 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 8 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 0.97 | 0.87–1.08 | 0.55 | F | 0.06 | 47 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 0.83 | 0.59–1.16 | 0.28 | R | 0.02 | 76 |

| D14 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 8 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 1.24 | 0.97–1.60 | 0.09 | R | <0.0001 | 77 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 0.94 | 0.76–1.17 | 0.59 | F | 0.55 | 0 |

| D15 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 6 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 0.86 | 0.69–1.07 | 0.18 | R | 0.03 | 60 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 1.19 | 0.88–1.59 | 0.26 | R | 0.10 | 57 |

| D16 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 5 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 1.00 | 0.84–1.19 | 0.98 | R | 0.05 | 58 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 1.10 | 0.84–1.43 | 0.50 | F | 0.18 | 47 |

| D17 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 5 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 1.45 |

1.04–2.02 | 0.03 | F | 0.20 | 33 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 1.13 | 0.72–1.77 | 0.59 | F | 0.64 | 0 |

| D18 vs. the

others | ≥8 | 3 | 7,728 | 6,154 | 0.85 | 0.51–1.42 | 0.55 | F | 0.69 | 0 |

|

| <8 | 3 | 1,956 | 1,168 | 1.48 | 0.77–1.59 | 0.24 | R | 0.14 | 50 |

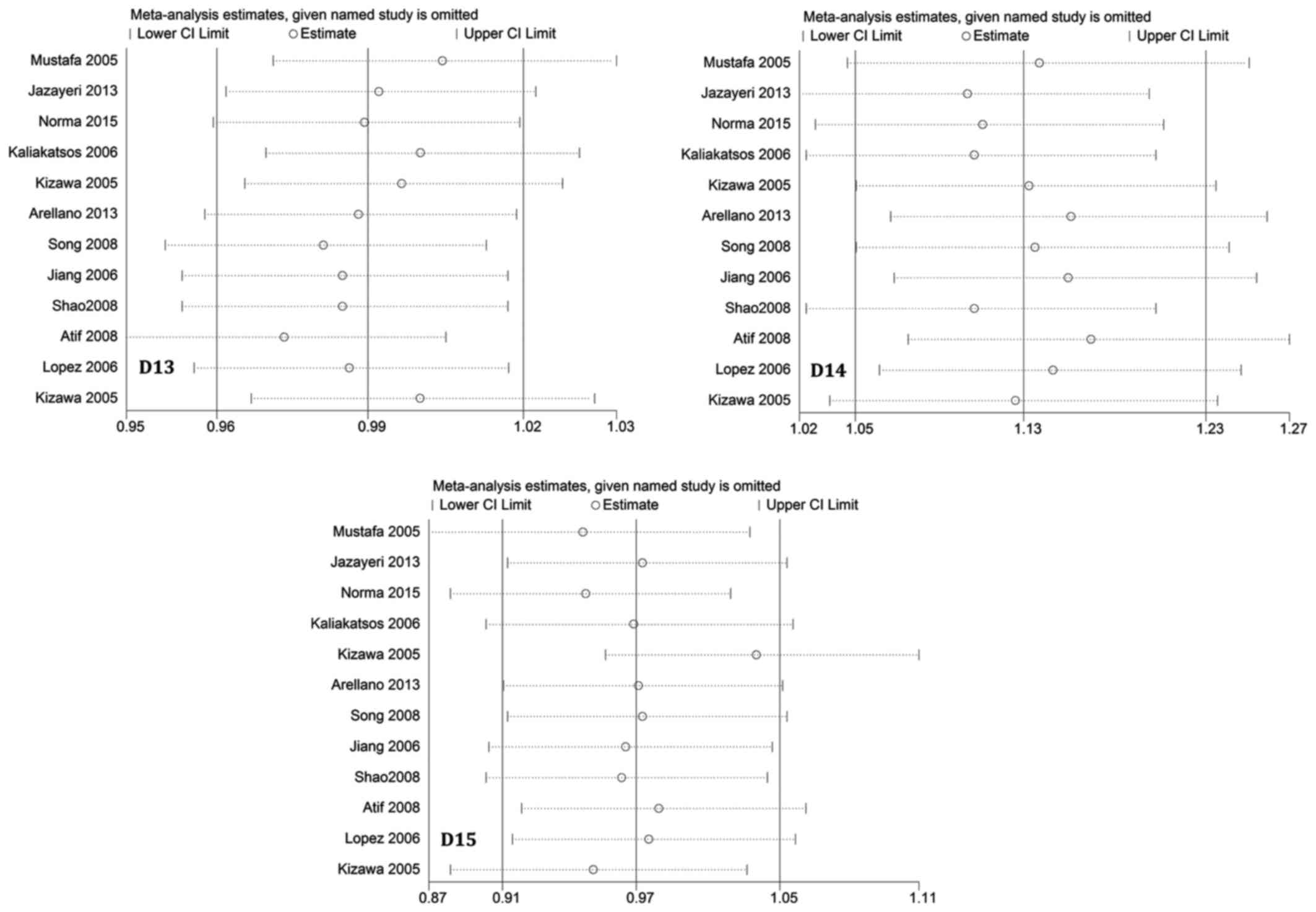

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the influence of each individual study on

the pooled ORs, a sensitivity analysis of sequential removal of

individual studies was performed. Results shown in Fig. 5 suggest that no individual study

significantly affected the pooled ORs, indicating that our

meta-analysis results were stable and reliable. Another sensitivity

analysis performed by excluding HWE-violating studies did not

perturb the overall results.

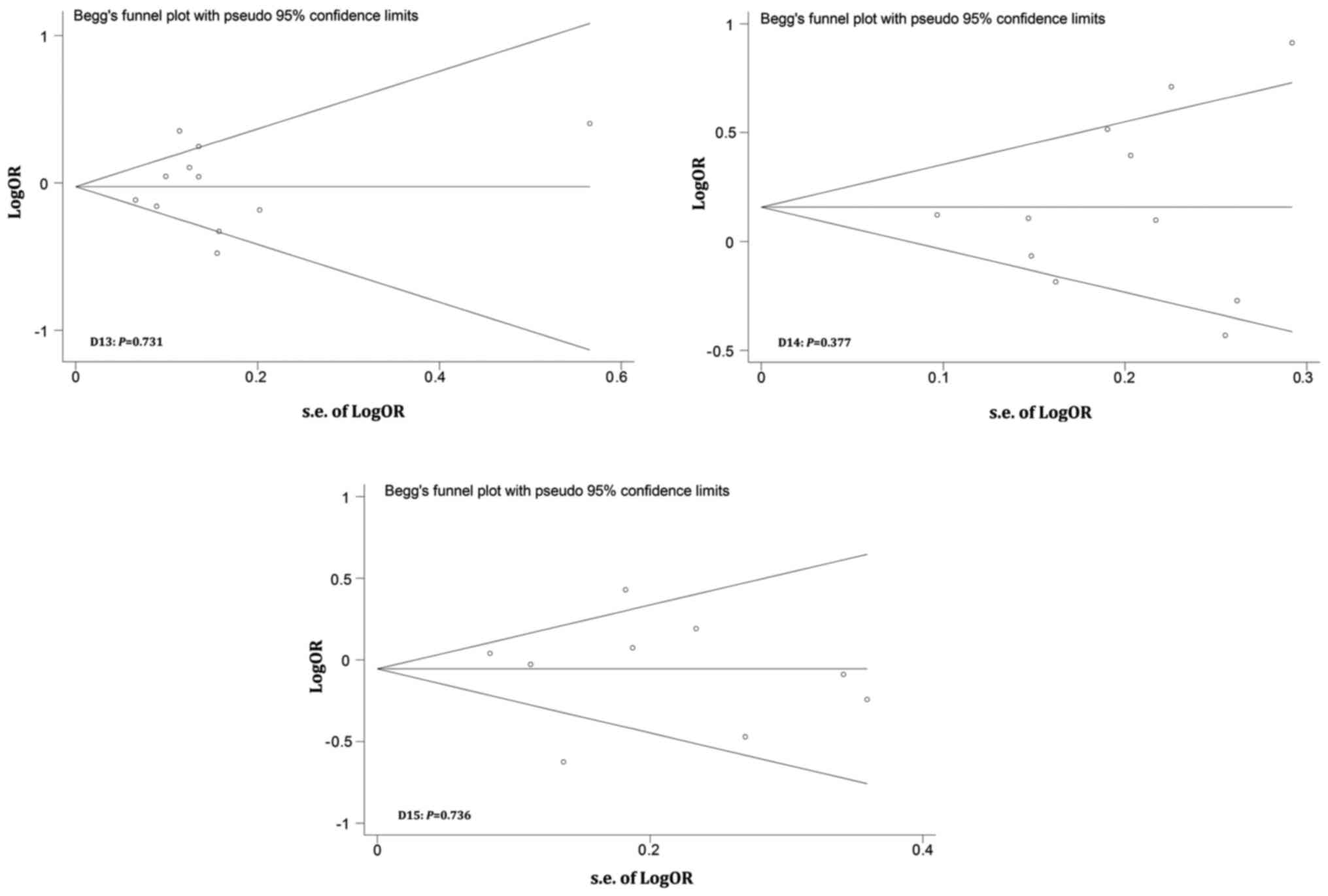

Publication bias

Publication bias was evaluated by performing Begg's

funnel plots and Egger's tests. Fig.

6 shows that the shapes of the Funnel plots were basically

symmetrical and did not reveal obvious evidence of asymmetry. All

P-values from Egger's and Begg's tests were greater than 0.05.

Therefore, our results suggest no evidence of any publication bias

in this meta-analysis.

Discussion

In the last few years, a greater number of

researchers have paid attention to the link between the ASPN gene

and OA. The ASPN gene encodes for a protein that is part of the 95%

CI family (23). This ASPN gene is

abundantly expressed in human articular cartilage with OA. In the

present meta-analysis, we included ten articles (eleven studies)

after reviewing the literature for the association between ASPN

D-repeat polymorphisms and OA susceptibility (6). In the present study, we aimed to

provide more convincing evidence regarding the role of ASPN

D-repeat polymorphisms in the incidence of OA.

According to a widely accepted viewpoint, ASPN is a

newly identified extracellular matrix protein that contains an

N-terminal unique aspartic acid repeat that ranges in length from 8

to 19 residues. The human ASPN gene has 8 exons. It spans 26

kilobases and is located in chromosome 9q31.1–32, which belongs to

the SLRP family. Previous studies have indicated that TGF-β1 plays

an important role as a regulator of cellular differentiation,

proliferation, apoptosis and migration in bone tissue. ASPN can

directly bind to the TGF-β1 receptor and thus inhibit the

expression of cartilage matrix Agc1 and Col2a1 genes, which are

mediated by TGF-β1 (24). The

interaction between ASPN and TGF-β1 can repress the expression of

cartilage matrix genes (25). Based

on the above findings, many researchers believe that ASPN may play

an important role in the occurrence of joint disease (26), including OA.

Many studies have focused on the association between

ASPN polymorphisms and OA, but a consensus has not yet been

reached. Mustafa et al (18)

found that ASPN polymorphism was not a major influence on OA

etiology in Caucasians. However, Kizawa et al (27) conducted a cohort study and a

case-control study and reported a significant association between

the Japanese population's D-repeat polymorphism and OA. Jiang et

al (28) studied 218 patients

and 454 age-matched controls from the Han Chinese population,

revealing for the first time that the OA susceptibility gene was

definitely replicated among different ethnic groups. The frequency

of the D14 allele in the Greek population showed no significant

difference compared with the other alleles, but the frequency of

the D13 allele was significantly lower in KOA patients (29). In contrast, the frequency of the D13

allele was found to be significantly different between female KOA

patients and controls compared with other alleles (30). In addition, Arellano et al

(31) suggested that polymorphisms

of the ASPN gene could influence KOA susceptibility, but they

indicated that this association also required more extensive

research. By investigating the allelic association of the D-repeat

polymorphism with OA, Jazayeri et al (3) suggested that the D15 allele could be

considered a risk allele only for the female Iranian population.

González-Huerta et al (1)

reported that the D14 allele of the ASPN polymorphism had a certain

impact on the etiology of primary OA of the knee. Therefore, a more

objective and accurate conclusion about the link between ASPN

polymorphisms and OA risk is required to provide a robust framework

for future studies in the field.

From an epidemiological point of view, a

case-control study is retrospective and is a causal study allowing

exploration of the etiology of diseases. However, a cohort study is

more effective than a case-control study for investigation of

disease etiology. We conducted an updated comprehensive analysis

based on case-control and cohort studies which focused on ASPN

polymorphisms and OA risk. The present meta-analysis included 7

studies (58.33%) on KOA, 2 studies (16.67%) on hand OA, and 3

(25.00%) on hip OA. In these 12 studies, 5 (41.67%) were conducted

in Asian populations, four (33.33%) in European populations and 2

(16.67%) in American populations. Results of this meta-analysis

showed that the D17 allele was a risk factor for OA and may

increase the incidence of OA (OR=1.33, 95% CI: 1.02–1.73,

P<0.05), particularly in studies with a large sample size

(N>1,000). Results also showed that the other types of alleles

did not play an important role in the development of OA. We

addressed the association between OA susceptibility and ASPN

D-repeat polymorphisms in populations originating from different

continents, and the results remained the same. We did not find any

significant association between ASPN polymorphisms and OA

susceptibility in the subgroup analyses performed according to the

OA site and the continent of origin.

We performed a comprehensive review of the

literature and designed strict inclusion and exclusion criteria to

obtain valid results. Compared with previous studies, our research

was more detailed and in addition we conducted different subgroup

and meta-regression analyses. There were, however, several

limitations in this meta-analysis (10–15,32): i)

Because there were inevitably mixed factors in the study, our group

analysis could not completely encompass them; ii) the results of

this meta-analysis may be misinterpreted due to the limited number

of research studies, the shortage of uniform inclusion criteria and

the existence of heterogeneity; iii) there is a lack of clinical

variables in the literature such as classification of OA severity,

and these variables are likely to be related to ASPN polymorphisms;

iv) in the subgroup analyses, the results may lack efficiency due

to the limited number of studies; and v) since the inclusion of the

literature may have been biased, even after using a regression

test, the inherent bias may have affected the overall analysis.

Moreover, as a complex multifactorial disease, development of OA

may have been affected by genetic or genetic-environmental

interactions between races. Therefore, further research is needed

to elucidate this question.

In summary, this meta-analysis study did not show

any association between ASPN polymorphisms and OA susceptibility in

Asians, Europeans or Americans. Thus, our results do not support

the common viewpoint that the ASPN polymorphisms (except for D17)

constitute risk factors for OA susceptibility in Asians, Europeans

or Americans. We observed that the D17 alleles of ASPN increased

the risk for development of OA if the considered sample size is

greater than 1,000. Because of large heterogeneity in the studies

included in this meta-analysis, we consider that the effects of

ASPN polymorphisms on OA development still require further

confirmation by larger studies performed in homogeneous

populations.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the researchers of the original

studies included in this meta-analysis.

Funding

The present study was supported by the youth

research project of Shaanxi University of Chinese Medicine

(2015QN05).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are

included in this published article.

Author contributions

RZ designed the study. JW, AY, JZ and RZ screened

the literature. NS, XiangwenL, XinghuiL, QL, JL and XR extracted

the data from the literature. JW, RZ and ZK conducted the

meta-analysis and wrote the manuscript. RZ and JW submitted the

study.

Ethics approval and consent to

participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing

interests.

References

|

1

|

González-Huerta NC, Borgonio-Cuadra VM,

Zenteno JC, Cortés-González S, Duarte-Salazar C and Miranda-Duarte

A: D14 repeat polymorphism of the asporin gene is associated with

primary osteoarthritis of the knee in a Mexican Mestizo population.

Int J Rheum Dis. 20:1935–1941. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

2

|

Song GG, Kim JH and Lee YH: A

meta-analysis of the relationship between aspartic acid (D)-repeat

polymorphisms in asporin and osteoarthritis susceptibility.

Rheumatol Int. 34:785–792. 2014. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

3

|

Jazayeri R, Qoreishi M, Hoseinzadeh H,

Babanejad M, Bakhshi E, Najmabadi H and Jazayeri SM: Investigation

of the asporin gene polymorphism as a risk factor for knee

osteoarthritis in Iran. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 42:313–316.

2013.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

4

|

Juchtmans N, Dhollander AA, Coudenys J,

Audenaert EA, Pattyn C, Lambrecht S and Elewaut D: Distinct

dysregulation of the small leucine-rich repeat protein family in

osteoarthritic acetabular labrum compared to articular. cartilage.

67:1–441. 2015.

|

|

5

|

Michael JW, Schlüter-Brust KU and Eysel P:

The epidemiology, etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of

osteoarthritis of the knee. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 107:152–162.

2010.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

6

|

Xing D, Ma XL, Ma JX, Xu WG, Wang J, Yang

Y, Chen Y, Ma BY and Zhu SW: Association between aspartic acid

repeat polymorphism of the asporin gene and susceptibility to knee

osteoarthritis: A genetic meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage.

21:1700–1706. 2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

7

|

Woolf AD and Pfleger B: Burden of major

musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ. 81:646–656.

2003.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

8

|

Zhang Y and Jordan JM: Epidemiology of

osteoarthritis. Clin Geriatr Med. 26:355–369. 2010. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

9

|

Haq SA and Davatchi F: Osteoarthritis of

the knees in the COPCORD world. Int J Rheum Dis. 14:122–129. 2011.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

10

|

Minafra L, Bravatà V, Saporito M,

Cammarata FP, Forte GI, Caldarella S, D'Arienzo M, Gilardi MC,

Messa C and Boniforti F: Genetic, clinical and radiographic signs

in knee osteoarthritis susceptibility. Arthritis Res Ther.

16:R912014. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

11

|

Fernandes MT, Fernandes KB, Marquez AS,

Cólus IM, Souza MF, Santos JP and Poli-Frederico RC: Association of

interleukin-6 gene polymorphism (rs1800796) with severity and

functional status of osteoarthritis in elderly individuals.

Cytokine. 75:316–320. 2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

12

|

Rushton MD, Reynard LN, Young DA, Shepherd

C, Aubourg G, Gee F, Darlay R, Deehan D, Cordell HJ and Loughlin J:

Methylation quantitative trait locus analysis of osteoarthritis

links epigenetics with genetic risk. Hum Mol Genet. 24:7432–7444.

2015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

13

|

Bijsterbosch J, Kloppenburg M, Reijnierse

M, Rosendaal FR, Huizinga TW, Slagboom PE and Meulenbelt I:

Association study of candidate genes for the progression of hand

osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 21:565–569. 2013.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

14

|

Nakamura T, Shi D, Tzetis M,

Rodriguez-Lopez J, Miyamoto Y, Tsezou A, Gonzalez A, Jiang Q,

Kamatani N, Loughlin J and Ikegawa S: Meta-analysis of association

between the ASPN D-repeat and osteoarthritis. Hum Mol Genet.

16:1676–1681. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

15

|

Valdes AM, Loughlin J, Oene MV, Chapman K,

Surdulescu GL, Doherty M and Spector TD: Sex and ethnic differences

in the association of ASPN, CALM1, COL2A1, COMP, and FRZB with

genetic susceptibility to osteoarthritis of the knee. Arthritis

Rheum. 56:137–146. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

16

|

Kou I, Nakajima M and Ikegawa S:

Expression and regulation of the osteoarthritis-associated protein

asporin. J Biol Chem. 282:32193–32199. 2007. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

17

|

Neptune ER, Frischmeyer PA, Arking DE,

Myers L, Bunton TE, Gayraud B, Ramirez F, Sakai LY and Dietz HC:

Dysregulation of TGF-beta activation contributes to pathogenesis in

Marfan syndrome. Nat Genet. 33:407–411. 2003. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

18

|

Mustafa Z, Dowling B, Chapman K,

Sinsheimer JS, Carr A and Loughlin J: Investigating the aspartic

acid (D) repeat of asporin as a risk factor for osteoarthritis in a

UK Caucasian population. Arthritis Rheum. 52:3502–3506. 2005.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

19

|

Atif U, Philip A, Aponte J, Woldu EM,

Brady S, Kraus VB, Jordan JM, Doherty M, Wilson AG, Moskowitz RW,

et al: Absence of association of asporin polymorphisms and

osteoarthritis susceptibility in US Caucasians. Osteoarthritis

Cartilage. 16:1174–1177. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

20

|

Min SK, Nakazato K, Ishigami H and

Hiranuma K: Cartilage intermediate layer protein and Asporin

Polymorphisms are independent risk factors of lumbar disc

degeneration in male collegiate athletes. Cartilage. 5:37–42. 2014.

View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

21

|

Thakkinstian A, McEvoy M, Minelli C,

Gibson P, Hancox B, Duffy D, Thompson J, Hall I, Kaufman J, Leung

TF, et al: Systematic review and meta-analysis of the association

between {beta}2-adrenoceptor polymorphisms and asthma: A HuGE

review. Am J Epidemiol. 162:201–11. 2005. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

22

|

Qin X, Peng Q, Tang W, Lao X, Chen Z, Lai

H, Deng Y, Mo C, Sui J, Wu J, et al: An updated meta-analysis on

the association of MDM2 SNP309 polymorphism with colorectal cancer

risk. PloS One. 8:e760312013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

23

|

Arellano-Pérez-Vertti RD, Argüello-Astorga

JR, Cortéz-López ME, Zamarripa-Mottú JI, García-Salcedo JJ and

Luna-Ceniceros DA: D-repeat polymorphism in the ASPN gene in knee

osteoarthritis in females in Torreón, Coahuila. Acta Ortop Mex.

28:363–368. 2014.PubMed/NCBI

|

|

24

|

Maris P, Blomme A, Palacios AP, Costanza

B, Bellahcène A, Bianchi E, Gofflot S, Drion P, Trombino GE, Di

Valentin E, et al: Asporin is a fibroblast-derived TGF-β1 inhibitor

and a tumor suppressor associated with good prognosis in breast

cancer. PLoS Med. 12:e10018712015. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

25

|

Shi D, Dai J, Zhu P, Qin J, Zhu L, Zhu H,

Zhao B, Qiu X, Xu Z, Chen D, et al: Association of the D repeat

polymorphism in the ASPN gene with developmental dysplasia of the

hip: A case-control study in Han Chinese. Arthritis Res Ther.

13:R272011. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

26

|

Duval E, Bigot N, Hervieu M, Kou I,

Leclercq S, Galéra P, Boumediene K and Baugé C: Asporin expression

is highly regulated in human chondrocytes. Mol Med. 17:816–823.

2011. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

27

|

Kizawa H, Kou I, Iida A, Sudo A, Miyamoto

Y, Fukuda A, Mabuchi A, Kotani A, Kawakami A, Yamamoto S, et al: An

aspartic acid repeat polymorphism in asporin inhibits

chondrogenesis and increases susceptibility to osteoarthritis. Nat

Genet. 37:138–144. 2005. View

Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

28

|

Jiang Q, Shi D, Yi L, Ikegawa S, Wang Y,

Nakamura T, Qiao D, Liu C and Dai J: Replication of the association

of the aspartic acid repeat polymorphism in the asporin gene with

knee-osteoarthritis susceptibility in Han Chinese. J Hum Genet.

51:1068–1072. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

29

|

Kaliakatsos M, Tzetis M, Kanavakis E,

Fytili P, Chouliaras G, Karachalios T, Malizos K and Tsezou A:

Asporin and knee osteoarthritis in patients of Greek origin.

Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 14:609–611. 2006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

30

|

Song JH, Lee HS, Kim CJ, Cho YG, Park YG,

Nam SW, Lee JY and Park WS: Aspartic acid repeat polymorphism of

the asporin gene with susceptibility to osteoarthritis of the knee

in a Korean population. Knee. 15:191–195. 2008. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

31

|

Arellano RD, Hernández F, García-Sepúlveda

CA, Velasco VM, Loera CR and Arguello JR: The D-repeat polymorphism

in the ASPN gene and primary knee osteoarthritis in a Mexican

mestizo population: A case-control study. J Orthop Sci. 18:826–831.

2013. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|

|

32

|

Rodriguez-Lopez J, Pombo-Suarez M, Liz M,

Gomez-Reino JJ and Gonzalez A: Lack of association of a variable

number of aspartic acid residues in the asporin gene with

osteoarthritis susceptibility: Case-control studies in Spanish

Caucasians. Arthritis Res Ther. 8:R552006. View Article : Google Scholar : PubMed/NCBI

|